Scott Timberg's Blog, page 27

September 26, 2014

The Pleasures of Waiting

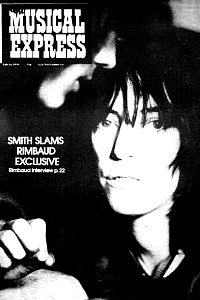

NO, this hasn’t become an abstinence-themed blog while you were napping. But I’m struck today by a piece about the joys of waiting for culture, whether it’s a weekly music newspaper or the new singles or LPst that those publications served to announce or assess. No matter what kind of culture you care about, you’ll find something you recognize in this essay by esteemed rock scribe Simon Reynolds in The Pitchfork Review.

Imagine, if you can, or remember, if you’re old enough, a long-ago time when music fans had to wait. Wait for news about music. Wait for reviews that were really previews of music you’d wait even longer to hear. (No teasing tasters, sanctioned streams, or illicit leaks in those days.) Anticipation and delay structured the daily experience of music fandom in the pre-internet era. All music and most information were things you literally got your hands on: they came only in analog form, as tangible objects like records or magazines.

In Britain, where I grew up, the primary source of news, commentary, and critique was the weekly music press: New Musical Express, Melody Maker, Sounds, and Record Mirror. The weeklies were stubbornly solid, slightly grubby things. Nicknamed “inkies” because their pages stained your fingers, they were printed on paper and shipped physically across the country, and also, in smaller quantities and at a more expensive price, to far-flung territories of the globe. How’s this for anticipation and delay? In those days NME and the other papers reached Australia and New Zealand by surface mail and thus arrived several months after they came out in the UK, by which time the British scene would have moved forward a considerable distance.

The essay looks, of course, primarily at the heyday of the British rock press — the NME and Melody Maker primarily — which helped shape the music of the punk and post-punk days, especially, as well as young minds.

But it’s more broadly a piece about the pleasures of anticipation and an analog sensibility. Further down, he writes:

To talk about the systemic virtues of a bygone mode of cultural transmission is to risk scorn. In a culture that idolizes technology and makes secular gods of figures like Steve Jobs and Mark Zuckerberg, it has become inadmissible to talk about change as anything but an a priori positive. And when these changes have taken place within the context of pop music, one also confronts youth’s reflexive patriotism for its own era, the way that hormonal triumphalism meshes with generational self-image to insist that only right now can be the best time. I understand that; I’ve felt that myself. I also know that change is inevitable, irreversible. But I don’t see why one shouldn’t attempt a calm and clear assessment of what’s been lost with the collapse and disappearance of the old ways.

The piece is long and leisurely, and deserves some of the relaxed contemplation it celebrates. Even when Reynolds is writing about the Sex Pistols and the Buzzcocks.

September 25, 2014

Switching Sides in the Digital War

DIDN’T we hear about how great it was going to be? Those early days, when we were told how funky and non-commercial and liberating the Web was going to be, now seem like ancient history. One writer who believed in the promise of the Internet in the early days has come to see what a much more complex issue the digital revolution would be.

In a farewell piece for Salon, Andrew Leonard writes about his early crush on digital technology and  “How I switched sides in the technology wars.” As Leonard — who I will miss from the pages of the online magazine — writes:

“How I switched sides in the technology wars.” As Leonard — who I will miss from the pages of the online magazine — writes:

Where once I evangelized, now I feel disposed to caution. Where once I gleefully trumpeted the way everything was going to change and everybody better get on board the train before they were run over on the tracks, now I find myself wondering when all this change is going to translate into a truly better world, one with greater social justice, a better deal, instead of a raw deal, for labor, and less income inequality, rather than more. And where once I was fascinated and seduced by geek culture, now I am repelled by Silicon Valley arrogance and hubris.

My only serious complaint about this piece is that I wish it were significantly longer — I’d like to see the personal transformation, as well as the morphing of Silicon Valley, fleshed out more fully. Maybe he’ll do that elsewhere.

My interest in the Internet is mostly regarding what it’s done to the creative class. In any case, this short essay is well worth reading and pondering.

September 24, 2014

The Roots of Author Jeff Hobbs

ONE of the breakout books of the fall is Jeff Hobbs’s new chronicle of his Yale roomate, a young black man who escaped the streets of Newark and found himself, in the end, pulled back down by some of the same old forces. I’m reading The Short and Tragic Life of Robert Peace now and amazed at how rich the detail is: It’s powerful — New York Times rave here — and about an intimate portrait of another life as any writer could render.

Which doesn’t entirely surprise me — I met Hobbs for an LA Times profile in 2007, around the time of his debut novel The Tourists. Between that book and a few meetings with him since, I’ve been struck by his powers of empathy and his apparent lack of ego. Here’s part of how the very young Hobbs struck me back then:

He was considered, he said, a “space cadet” as a teenager back home amid the mushroom farms of rural Delaware — the kind of kid who would often disappear under a tree to read Lloyd Alexander’s fantasy novels.

A serious runner in college, Hobbs seems most comfortable viewing the world from a distance. He’s so polite that while discussing his work on a patio behind a dive bar in Los Feliz, he apologized for the day’s intense breeze. Some combination of shyness and Ivy League reserve seemed to keep him from making more than a few indirect comments about his novel. A lot of the book, he said, is just “the stuff you overhear on the street, between strangers.”

The Tourists was a sketch of privilege, while The Short and Tragic Life is primarily about a very rough world. A lot of writers would not be able to pull off both.

In any case, I look forward to finishing his book about his Robert Peace. There’s no way Hobbs or anyone else can bring his old friend back, but reading this book, you really feel like you know the guy, as well as his fiercely protective mother. All of this a reader feel the tragedy ever harder, but I expect anyone who knows Peace, or someone like him, will be grateful for such a respectful work.

Musician Dean Wareham Raves on About Culture Crash the Book

ONE of my favorite indie rock musicians — a member of Galaxie 500, Luna, and Dean & Britta — has endorsed my upcoming book. Here’s what he says:

I read Scott Timberg’s pieces every week without fail. It’s great to see his book Culture Crash debunk the mumbo jumbo about the long tail, file-sharing, free information, and positive thinking — and take a hard look at what it all means for artists, musicians, critics and teachers.

Dean is also a substantial writer himself, and I don’t just mean songs like “Tiger Lily” and “Lost in Space.” His Black Postcards: A Memoir is the best musician’s-eye-view of the alternative and indie-rock movement. Proud to have such a longtime hero of mine on board.

(From our Department of Self-Promotion)

September 23, 2014

Do Artists Embrace or Resist Technology?

WELL, both, and neither, I can hear someone out there growling. But what I mostly hear in the culture at large is that we — citizens, worker bee, student, scribe — need to “adjust” to the brave new world of digital technology. Some of us do. But as someone who’s been to numerous exhibits and conferences on “art and tech,” I’ve long been uneasy with the suggestion that visual artists (or musical or literary artists, for that matter) need to embrace the latest “innovation.”

The art critic Dave Hickey put his finger on this in a recent post.

What troubles me about the contemporary relationship between art and technology: Since Manet, art has thrown itself up as a counter discourse to the reigning mainstream technology. Impressionism threw itself self up to counter the new hegemony of photography. Futurism threw itself up against to the rhetoric of ancient Italy. Surrealism threw itself up to counter the reign of the verisimilar image. Abstract Expressionism exploded in the face of residual wartime regimentation. Pop arose to counter the graphic, black and white, Fifties. Minimalism is eccentric in its pretentions: It threw itself in the face of history and of all other art. Then Conceptualism arose to counter the shiny, Technicolor sixties and prefigure the digital future. Once the digital future arrived, I was rather assuming the return of haptic, tactile, fractal in the art world. But no! Academics always want to do things the easy way. Facebook succeeded Press-Type, Digital printouts succeeded Xeroxed photographs, and we have limped along through half a century of geriatric post-minimalism. Is it just my friend Dave who’s being bored to tears?

I don’t just think it’s Dave here. In his book of jazz criticism, The Imperfect Art, Ted Gioia wrote about the way jazz has historically framed itself in opposition to technology and mass production. The subject is big and complex, but has me thinking.

September 22, 2014

Who Broke Hollywood?

WITH an awful and low-yielding summer movie season recently concluded, I’ve been meaning to try to make sense of the continued decline of grownup film, independent and otherwise. Two LA Times stories get at the problem, which is both economic and aesthetic.

The first story, by Josh Rottenberg, takes the point of view of frustrated screenwriters.

Over the last few decades, as the studios have shifted their business models toward making fewer, bigger would-be blockbusters, a certain kind of movie that used to be the bedrock of American cinema — namely the kind aimed at adults who didn’t necessarily grow up surrounded by stacks of comic books — has gotten only more difficult to make. Unfortunately, that just happens to be the kind of movie that Frank, like many of his peers, aims to write.

He quotes bigtime screenwriter Scott Frank, who sees a lot of writers moving to TV:

“I’m sure ‘Out of Sight’ wouldn’t get made today,” Frank said recently. “‘Little Man Tate’ definitely wouldn’t be made. Even ‘Get Shorty’ is a struggle to get made today. They’re all tricky movies that probably wouldn’t happen.”

Also worth noting is this statistic: “Meanwhile, over the past five years, total earnings for work in film reported by WGA members has dropped more than 24% as a number of studios have cut back on production.”

The second is a critical reflection by Kenneth Turan, whose essay asks what’s changed since 1939.

Among the films released in 1939 alone were “Gunga Din,” “Stage Coach,” “Love Affair,” “Wuthering Heights,” “Dark Victory,” “Young Mr. Lincoln,” “Beau Geste,” “Goodbye Mr. Chips,” “The Wizard of Oz,” “The Women,” “Golden Boy,” “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington,” “Ninotchka,” “Destry Rides Again” and, of course, “Gone With the Wind.” Comedies, dramas, westerns, fantasies, period pieces, inspirational tales, romances. And that’s just scratching the surface.

Today’s Hollywood, by contrast, has transformed itself into the hedgehog. The one big thing it knows how to do is make sequels and superhero movies and sequels to superhero movies, all aimed at a young adult crowd with no end in sight. The race to secure prime spots has become so intense that studios have claimed release dates for as-yet-untitled superhero movies through 2020, which at this point feels a bit like rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.

Hollywood, he says, has doubled down on a single audience sector and a single kind of film — like a farmer who relies on just one crop. Like Lynda Obst, he blames corporate control and the overseas market.

September 19, 2014

Was Adorno Right?

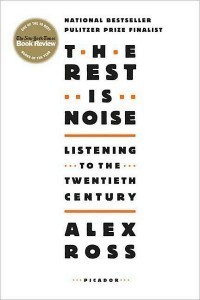

I WANT to go back for a minute to Alex Ross’s wonderful piece, “The Naysayers ,” on the Frankfurt School. Ross drifts between interpretations here, but he comes up with a very resonant description of what’s gone wrong with our culture over the last few decades:

,” on the Frankfurt School. Ross drifts between interpretations here, but he comes up with a very resonant description of what’s gone wrong with our culture over the last few decades:

If Adorno were to look upon the cultural landscape of the twenty-first century, he might take grim satisfaction in seeing his fondest fears realized. The pop hegemony is all but complete, its superstars dominating the media and wielding the economic might of tycoons. They live full time in the unreal realm of the mega-rich, yet they hide behind a folksy façade, wolfing down pizza at the Oscars and cheering sports teams from V.I.P. boxes. Meanwhile, traditional bourgeois genres are kicked to the margins, their demographics undesirable, their life styles uncool, their formal intricacies ill suited to the transmission networks of the digital age. Opera, dance, poetry, and the literary novel are still called “élitist,” despite the fact that the world’s real power has little use for them. The old hierarchy of high and low has become a sham: pop is the ruling party.

The Internet threatens final confirmation of Adorno and Horkheimer’s dictum that the culture industry allows the “freedom to choose what is always the same.” Culture appears more monolithic than ever, with a few gigantic corporations—Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon—presiding over unprecedented monopolies. Internet discourse has become tighter, more coercive. Search engines guide you away from peculiar words. (“Did you mean . . . ?”) Headlines have an authoritarian bark (“This Map of Planes in the Air Right Now Will Blow Your Mind”). “Most Read” lists at the top of Web sites imply that you should read the same stories everyone else is reading. Technology conspires with populism to create an ideologically vacant dictatorship of likes.

Neither Ross (nor I) see this as the whole story of 21st century culture. There are plenty of good things, too.

But as wrong as Adorno could be about some things (jazz, the jitterbug), he saw some of this coming. And Ross summarizes one side of the equation quite eloquently.

Neutral Milk Hotel at the Hollywood Bowl

WHAT would the world look like if a bomb wiped out everyone who wasn’t a Gen Xer? A lot like the crowd that filed into the Hollywood Bowl last night. I kept telling myself that we were a very small generation as I saw the rows of empty seats for a show by the Breeders and Neutral Milk Hotel — both cult bands who only released two LPs each during their original run in the ’90s — and Danielle Johnston, an older and more prolific musician, but one who has been effectively adopted by Gen X audiences and musicians.

In any case, everyone besides the loud Boomer couples in the box next to us — who would not stop talking about their mango salsa and the rest — seemed to be between 40 and 50, and wearing retro glasses. I didn’t fear for the quality of the show, but feared that the low turnout would convince the Bowl leadership would cease booking indie-rock shows by anyone but superstars.

I should not have worried. As Johnston — a manic depressive who was visibly shaking while he sang — belted out songs like “Speeding Motorcycle” and “Walking th e Cow” (a song so poignant it really needs a new title) with a tough garage band, the place started to fill up. (We Xers are often late arrivers.) By the end, the show was the first I’ve seen this year that I can call triumphant.

e Cow” (a song so poignant it really needs a new title) with a tough garage band, the place started to fill up. (We Xers are often late arrivers.) By the end, the show was the first I’ve seen this year that I can call triumphant.

The Breeders rolled out (literally) with a drone-y song called “Off You” I did not recognize at all. Despite loving these guys during their first go-round, which lasted about 20 minutes, I’ve not given them much thought since. But my first thought was, Sheesh! is Kim Deal’s voice good, clear, sexy, expressive — better than I remember. And then, these guys have turned into a sonically more interesting band than I remember.

Their renditions of their “hits” — “Cannonball,” for instance — were fine, but it was the stuff I didn’t know that impressed me. The Breeders song or two that was overplayed in the early ’90s may’ve blinded me to how strong and musically adventurous they are. The more open, jazz-like songs — the opener, for instance, from 2002’s Steve Albini-produced Title TK — were stunning. A short, great set.

Could Neutral Milk Hotel — once part of Athens, GA’s wonderful but insular Elephant 6 Collective, with its reputation for eccentricity and reticence — live up to that? When I saw these guys on their tour for their signature album, In the Aeroplane Over the Sea, at Spaceland in Los Angeles in 1998, they played well, but the tiny club was not (to my memory) even full. How could they make enough noise to fill the 15,000-seat Hollywood Bowl? Especially when they had asked not to be projected in the enormous video screens that flanked the stage: They were effectively asking to be smaller than the opening bands.

I’m glad to say that Neutral Milk Hotel somehow pulled it off. Band leader Jeff Mangum came to the edge of the stage, along, and started strumming his guitar and singing the song “I Will Bury You.” Again, what a voice! The group — which includes some horn players and an accordionist — came out, and after about a dozen songs that blended indie guitar-rock with Celt-y touches, VU-distortion and hints of country folk, they were gone, just as mysteriously as they’d arrived.

I’d always liked these guys, but it was amazing to see how the songs — while remaining as inscrutable as they’d always been, Anne Frank allusions aside — sounded completely of our time, and riveting. Since their reunion last year, I’d been wondering how NMH had become one of the few bands from the ’90s indie scene to become bigger than they’d been originally. Some of it has to do clearly, with the air of mystery they’ve cultivated, and Mangum’s reclusiveness.

But the show proved something else — these guys are outta sight.

September 18, 2014

The Big Lie of Jeff Koons

IS it possible that the most characteristic artist of our time could also be almost entirely full of b.s.? From what I can tell, that’s exactly what we’ve got. Over the last week or so I’ve been underlining lines from Jed Perl’s New York Review of Books piece on the art world’s Gilded boy, thinking and talking about Perl’s argument, without yet posting the piece. “The Cult Jeff Koons” is really worth reading in full — there are subtleties I will not be able to convey here. So I will offer a few bits of the essay with hopes that readers will seek out the whole thing.

One of my main concerns: Does Koons critique or question our society the way substantial artists have? Or does he just amp up its worst qualities and sell it back to us?

Perl sees Koons — a retrospective is currently up at the Whitney in New York – as a kind of smug, cheerful bully, someone whose cheerleaders suggest you have to like or risk being irrelevant, Puritanical, left behind by history, joyless, and so on. Here’s what Koons really is:

as a kind of smug, cheerful bully, someone whose cheerleaders suggest you have to like or risk being irrelevant, Puritanical, left behind by history, joyless, and so on. Here’s what Koons really is:

Koons is a recycler and regurgitator of the obvious, which he proceeds to aggrandize in the most obvious way imaginable, by producing oversized versions of cheap stuff in extremely expensive materials. It is only when he rejects the real in favor of the surreal that the audience’s interest begins to cool. In his recent paintings he has created what amount to photorealist collages, with inflatable toys, cartoon characters, classical statuary, and details of a woman’s hot-red lips or sexy head of hair layered and juxtaposed to create trippy Pop fantasy visions. These 3-D surrealist dreamscapes, with their echoes of Dalí—Koons cites Dalí as a major early influence on his work—are almost invariably said to be his weakest stuff. The public wants its Koons real rather than surreal. People want their Koons straight up, unadulterated. Koons is here to prove that in our been-there-done-that society metaphor and mystery and magic are dead and gone. It all comes down to familiarity.

And despite the fact that the Koons cult calls him the next step in Dada and an heir to Duchamp, Perl builds a rigorous art-historical argument and comes down this way:

The Koons retrospective is a multimillion-dollar vacuum, but it is also a multimillion-dollar mausoleum in which everything that was ever lively and challenging about avant-gardism and Dada and Duchamp has gone to die… Koons’s overblown souvenirs are exactly what Duchamp warned against, a habit-forming drug for the superrich.

Now, much of the reason art-world types champion Koons (and some of these people are my friends, and one of them, Peter Schjeldahl, is one of my favorite critics) is that his work stirs people up so much — offends sensibilities, induces shock — that he must be good. It’s sort of the Lady Gaga argument: Elvis offended people, and he was great, Gaga does too — so she’s as good as Elvis. Perl puts his finger on this scam, after describing the way Matisse and Nijinsky scandalized audiences:

For the Gilded Age avant-garde, such legendary events have become the model for new marketing opportunities, and there is an assumption that if the public has a very strong negative reaction to something—if a work of art disturbs or annoys or flummoxes some of the public—it most likely is important. Incredibly enough, there are highly intelligent observers who believe that Koons challenges them in more or less the same way that Matisse, Picasso, Nijinsky, and Pollock might once have done.

Readers can probably guess how I come down on this. Perl makes the argument better than I could. But if you’re curious how I see Jeff Koons, and the adulation around him, fitting into our larger cultural situation and our current winner-take-all economy accompanying a protracted economic downturn, keep your eye out for my book Culture Crash, due in just a few months from Yale University Press.

September 17, 2014

Who Still Buys CDs?

BESIDES Luddites and hipsters? (I’m borrowing here from the stage patter of the young folk duo the Milk Carton Kids.) Turns out, Japanese people still buy CDs. A country famous for loving technology and novelty are moving into the future by acting like it’s the past. From a New York Times story:

Japan may be one of the world’s perennial early adopters of new technologies, but its continuing attachment to the CD puts it sharply at odds with the rest of the global music industry. While CD sales are falling worldwide, including in Japan, they still account for about 85 percent of sales here, compared with as little as 20 percent in some countries, like Sweden, where online streaming is dominant.

And amazingly, as a tribute to the collector/High Fidelity culture that still exists in Japan:

Tower Records closed its 89 American outlets in 2006, but the Japanese branch of the chain — controlled by NTT DoCoMo, Japan’s largest phone carrier — still has 85 outlets, doing $500 million in business a year.

For musicians — who make substantially more money from CD and vinyl sales of their work than downloads or streams — this is good news. But the larger trends continue to be worrisome.

In the United States, digital sales have long since overtaken physical ones. But CDs still account for 41 percent of the $15 billion recorded music market worldwide, and, in addition to Japan, some big markets like Germany remain reliant on CD sales. That attachment worries some analysts, who contend that if those countries do not embrace online music, an inevitable decline in CD sales will further damage the industry.

Keigo Oyamada and Ryuichi Sakamoto

Scott Timberg's Blog

- Scott Timberg's profile

- 7 followers