Scott Timberg's Blog, page 24

October 24, 2014

Techo-Utopianism and the TED talk

MOSTLY, I try to dig into the arts and culture in this blog. But there are times when digital technology demands attention; technology has become the water in which we all — musician and scribe and architect alike — swim.

That’s why I’m especially pleased to nudge readers toward a piece that’s been floating around for a while which even some informed people may have missed: “We need to talk about TED,” in which art and design scholar Benjamin Bratton compares TED talks to American Idol. Even if you’ve read it before, you’re probably rolling your eyes — “that, again?” — it’s worth revisiting. Here’s how he leads off:

In our culture, talking about the future is sometimes a polite way of saying things about the present that would otherwise be rude or risky.

But have you ever wondered why so little of the future promised in TED talks actually happens? So much potential and enthusiasm, and so little actual change. Are the ideas wrong? Or is the idea about what ideas can do all by themselves wrong?

I write about entanglements of technology and culture… So the conceptualization of possibilities is something that I take very seriously. That’s why I, and many people, think it’s way past time to take a step back and ask some serious questions about the intellectual viability of things like TED.

As he says partway down:

I’m sorry but this fails to meet the challenges that we are supposedly here to confront. These are complicated and difficult and are not given to tidy just-so solutions. They don’t care about anyone’s experience of optimism. Given the stakes, making our best and brightest waste their time – and the audience’s time – dancing like infomercial hosts is too high a price. It is cynical.

One of the many good things about this essay — I’ve linked to the Guardian version — is that Bratton delivered it as an actual TED talk (here) at TEDx San Diego. It’s quite electrifying, I think. He gets into all kinds of contradictions in techno-utopianism, Silicon Valley solutionism, and the shallowness of contemporary culture — including what he calls “placebo politics and placebo innovation.”

These issues have only gotten more dire — and the mythology around the benevolent wisdom of our corporate overlords even thicker — since the original speech.

I don’t know the dude, though Bratton was in LA, at the architecture school SCI-Arc, until a few years ago. I feel like someone has tapped into my thinking over the last few years and made it sharper and more focussed. Some of the subjects he gets into in his address show up in my upcoming tome Culture Crash, and I hope I’m able to deliver them with the kind of force he has.

October 23, 2014

Lonnie Johnson’s Guitar

THERE’S been a lot of bad news for culture and society lately, so I want to offer one of my occasional bits of inspiration. Jazz and blues player Lonnie Johnson is one of the greatest-ever American musicians, and one of the most underrated guitarists in history. His playing predates Robert Johnson and many of the Delta blues masters, and he developed a more polished urban style that to T-Bone Walker and through him to Chuck Berry and B.B. King. He’s also got a wonderfully keening and understated voice.

Johnson’s duos with 20s jazz guitarist Eddie Lang may be the best two-guitar sessions in history.

Here is a video of “Another Night to Cry”; I think this footage comes from the American Folk Blues Festival that toured Europe in the ’60s. He’s introduced by the great blues harpist Sonny Boy Williams on.

on.

October 22, 2014

Stop Working For Free

BY now, the movement urging artists, writers, musicians and other creatives to stop donating their labor has made some noise in the culture: It’s one of the key issue for today’s exploited creative class. But I’ve not seen the subject framed as well as this new Daily Beast story, with its subhead: “Remember when people volunteered to help the poor? Nowadays the poor volunteer to help the wealthy.”

As Ted Gioia (a longtime friend of CultureCrash) writes:

In recent weeks, the Ritz-Carlton hotel company, the NFL, and the Smithsonian Institution have all made news by asking people to do work for free. Such practices are hardly surprising in themselves—working for nothing seems to be a key building block of the new economy. But the fact that these requests come from such huge organizations with deep pockets raises troubling questions.

… These are not start-ups or struggling new media companies, but established businesses in old school industries. The trend is ominous. Web startups made it cool to build a business model on unpaid labor, but now cash rich companies with highly paid senior management want to play by the same rules.

Part of what I like about this piece is the way Ted identifies the source as not just the recession or corporate greed (though those are factors) but as coming from the cultural of Silicon Valley. The musician David Lowery once described the ethos there as a cross between hippie and Ayn Rand: “What’s yours is mine, and what’s mine is mine.” Ted calls Google, which owns YouTube, “a company that has done more to impoverish musicians and other creative professionals than any entity on the face of the planet.”

Part of what I like about this piece is the way Ted identifies the source as not just the recession or corporate greed (though those are factors) but as coming from the cultural of Silicon Valley. The musician David Lowery once described the ethos there as a cross between hippie and Ayn Rand: “What’s yours is mine, and what’s mine is mine.” Ted calls Google, which owns YouTube, “a company that has done more to impoverish musicians and other creative professionals than any entity on the face of the planet.”

In any case, Ted is a pragmatist, and the piece concludes with five suggestions for when creatives should work for free, starting with: “Only charities and non-profits should ask for unpaid workers to staff their operations or undertake time-consuming projects.” A great piece that I hope is read far and wide.

October 21, 2014

How Artists Do (and Don’t) Make a Living

A NEW study is starting to draw attention, and it confirms some of what we’ve suspected: That despite the rise of university programs to educate artists, the employment market for the fine arts continues to tighten. So we’re left with more and more people stranded, often with significant amounts of student-loan debt. And the number of people can actually make a living as an artist with a fine-arts degree remains quite low, close to just 10 percent.

Here is the way a Hyperallergic story — which both presents and critiques the findings of this new study, which is built from Census data — begins:

There’s one very clear take-away from the latest report released by the collectiveBFAMFAPhD: people who graduate with arts degrees regularly end up with a lot of debt and incredibly low prospects for earning a living as artists. Or, as they put it in the report, titled Artists Report Back: A National Study on the Lives of Arts Graduates and Working Artists, “the fantasy of future earnings in the arts cannot justify the high cost of degrees.”

The story is written by Alexis Clements, one of the more credible and nuanced of scribes trying to get at the economics of culture-making. Her whole post is long and complex, so I encourage interested parties to read it all. But part of what I like about her argument is how she pivots to the larger economic situation.

While this report focuses specifically on the arts, I couldn’t help but notice that it’s a part of a much larger conversation that’s been roiling across fields recently, particularly when it comes to graduate degrees. Our higher education system is producing a vast qu

antity of workers with educations and expectations for high-level and high-paying jobs that simply do not exist in the quantity needed to employ all these people.

Earlier this month the Boston Globe published a lengthy article highlighting the reality that postdoctoral researchers in biomedical fields, after nearly a decade of schooling, are becoming in some ways the equivalent of interns, with low paying menial jobs that offer little potential for promotion or even hiring. And biomedical sciences are hardly the only ones. There’s trouble for a scientists with PhDs across fields, and while the glut of lawyers seems to be slowing slightly, it hasn’t gone away, and salaries have dramatically decreased for those shouldering huge debt burdens from law school.

Unfortunately in the arts, we seem to be still ramping up when it comes to higher degrees, rather than pulling back.

There are a number of posts on this survey so far, but this one has by far the most depth I’ve seen.

Rosanne Cash on Our Culture’s Big Lie

LATELY the country-steeped singer-songwriter has become vocal and eloquent on issues of artists’s rights, including an appearance before lawmakers in Washington, DC; she’s also on the executive board of the Content Creators Coalition. The freshest thing about the arguments made by this daughter of St. Johnny is that she looks not only at technological and economic but the cultural causes of our current culture crash. In other words, what is it about our thinking, our assumptions about the arts, that have kept us from fixing this mess?

Here is what Cash posted on her Facebook account; I have blocked it into paragraphs for clarity.

For those of you who keep telling me that artists should work for free for the sheer joy of creation: You’ve been watching too many operas about starving artists who die before their time and are glorified for it. Do you pay your plumber? Your kid’s teacher? Your mechanic? Your grocer?

If art and music are not important to you, by all means, don’t buy them. If they are, then PAY for them, as you do everything else in your life that you require for physical or spiritual sustenance.

Yes, people will always create. I have spent 35 years of hard work, with a bone-crunching schedule, to achieve some level of mastery over what I do. It took me almost two years to make my last record, and I had to pay bills during that time. It is my profession, not my hobby.

I do not participate in the notion that music should be free, until tech companies who use our work as a loss leader also work for free, and until the CEOs of those companies stop taking home millions of dollars in ad revenues which they make by using the work of songwriters and musicians as bait.

Cash’s arguments have impressed me for a while now, and I hope to speak to her soon and get her to expand on some of this.

October 20, 2014

Will Cable TV’s Golden Age Last Forever?

THE answer to this question, I must admit, eludes me. But the era of deep and complex narrative television born with The Sopranos (and carried through Deadwood, Mad Men, etc) seems to have moved into another chapter as HBO and CBS announce streaming services. Here’s the beginning of my new piece on Salon:

The most prestigious of the cable channels and the most-watched of the traditional networks both now announced moves to streaming services. CBS’s service began last week; HBO’s will launch sometime next year, and its details are currently unclear. Both HBO Go and CBS All Access will allow people to watch their shows without subscribing to a cable service, and will add to the millions of existing “cord cutters” — a group, heavy on young viewers, that was already growing.

…Los Angeles Times business columnist David Lazaruz calls it “an understatement to say that this will shake up the pay-TV business as we know it.”

This could all be good for creators and consumers alike; my view is not as bleak as Salon’s headline. But remember Robert Frost’s line: “Nothing gold can stay.”

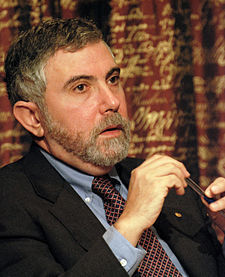

Paul Krugman on Amazon

Is the online bookseller a monopoly? A monopsony? I’ll leave the details to the economists, but will concur with the New York Times columnist — and the recent New Republic story — on the company’s danger. The most succinct way to phrase it may be the way Paul Krugman opens today’s column: “Amazon.com, the giant online retailer, has too much power, and it uses that power in ways that hurt America.”

I keep reading how great Amazon is for consumers, and don’t entirely disagree. Wal-Mart sells things cheaply, too, and it’s great for a while, until they start destroying small businesses in your town, putting people out of work, and hiring a few of them back without benefits or medical insurance (many of which are eventually paid by taxpayers). It’s not just about getting a cheap tire, or in Amazon’s case, an e-book for less than it cost the publisher, author and everyone else to produce it.

Here’s Krugman again:

Meanwhile, Amazon’s defenders often digress into paeans to online bookselling, which has indeed been a good thing for many Americans, or testimonials to Amazon customer service — and in case you’re wondering, yes, I have Amazon Prime and use it a lot. But again, so what? The desirability of new technology, or even Amazon’s effective use of that technology, is not the issue. After all, John D. Rockefeller and his associates were pretty good at the oil business, too — but Standard Oil nonetheless had too much power, and public action to curb that power was essential.

After explaining the fight with the Hachette publishers:

After explaining the fight with the Hachette publishers:

So can we trust Amazon not to abuse that power? The Hachette dispute has settled that question: no, we can’t…. Which brings us back to the key question. Don’t tell me that Amazon is giving consumers what they want, or that it has earned its position. What matters is whether it has too much power, and is abusing that power. Well, it does, and it is.

As it gets more power and wealth, why should we think Amazon won’t start gouging consumers as well? At some point, we’ll all be the gazelles.

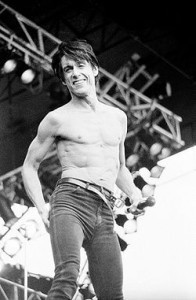

Iggy Pop Rips the State of Music

TODAY I have a new Salon post that quotes an Iggy Pop speech in the UK, and tries to make sense of it.

Well into the age of streaming, we’re still hearing from a few musicians – most of them promoted and even employed by the tech sector – that we live in the best of all possible worlds. Some resent the new arrangement, where they earn pennies from Spotify or Pandora plays, but don’t want to antagonize what’s left of the music industry. Journalists often hear from new streaming services that claim to be “artist friendly” despite their low royalty rates.

So it’s refreshing when established musicians speak honestly about the current crisis.

The whole piece is here .

.

And a story in the Globe and Mail adds to Pop’s argument:

A few days before Iggy’s lecture, Australian novelist Richard Flanagan won the Booker Prize, the most prestigious in the literary world, for his Second World War story The Narrow Road to the Deep North. Just in time, it sounds like: Mr. Flanagan told reporters that he was making so little from his writing that he was thinking about packing it in and becoming a miner. (He comes from a small mining town in Tasmania.) The prize money of about $90,000 and the following sales bump will allow him to continue, but most of his colleagues aren’t so lucky: “Writing is a very hard life for so many writers,” he said.

This is borne out not only in the quiet sobbing you hear in corners at poetry readings, but in the numbers. This summer, the Guardian newspaper reported that professional writers’ salaries in Britain are collapsing, falling almost 30 per cent over eight years to $20,000.

Here, the Writers’ Union of Canada estimates that authors make an average of $12,000 a year from their words. That will buy approximately two wheels of a car or a door knob on a house in Toronto or Calgary (a broken knob, if the house is in Vancouver).

Here’s that full story by Elizabeth Renzetti.

October 19, 2014

More Death Among the Alternative Press

AT a certain point, we won’t even notice it anymore when a publication we’ve loved and learned to rely on fades to black. For a little while longer, though, we’ll still register it. That’s one of the reasons I’m grimly happy to have had the chance to weigh in on the loss of two more alternative weeklies — the Providence Phoenix on the East Coast and the San Francisco Bay Guardian on the West.

Here’s the way I started my Salon piece:

In the San Francisco Bay Area, the unrelenting rise of the tech sector is pushing musicians and middle-class workers – bohemian and bourgeoisie alike – out onto the streets. Across the country in Providence, Rhode Island, Vincent “Buddy” Cianci, a felonious and charismatic former mayor once jailed for corruption, plots his return to City Hall. They’re both the kind of stories that alternative weeklies thrive in covering, especially in a city like San Francisco that has almost never had a decent daily paper. But in both cases, important voices are about to go silent: The San Francisco Bay Guardian, founded in 1966, put out its last issue this week. And The Providence Phoenix, which started in 1979 as The NewPaper will publish its last issue on Friday.

These papers are important. Alas, this dying off is not likely to abate any time soon.

These papers are important. Alas, this dying off is not likely to abate any time soon.

October 17, 2014

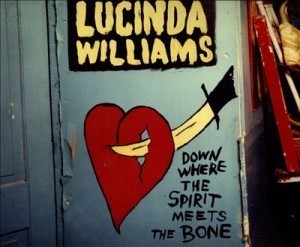

New Lucinda Williams Record

HERE at CultureCrash, we’re all dedicated Lucinda Williams fans of long standing. Her new double-disc album, Down Where the Spirit Meets the Bone, is one of country/folk/blues artist’s finest, and includes not just longtime associates like lap steel and mand0lin master Greg Leisz but jazz guitarist Bill Frisell.

In honor of the new record, we present a link to this little filmed intro to one of the album’s songs, “Temporary Nature.”

And here is the whole song itself, the kind of number Otis Redding would have been proud to sing. There are few surprises on this record, but it’s smart, deeply felt, and the rare two-CD set that is strong all the w ay through.

ay through.

Scott Timberg's Blog

- Scott Timberg's profile

- 7 followers