Scott Timberg's Blog, page 25

October 16, 2014

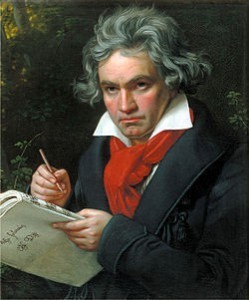

Was Beethoven a Bad Influence?

A FASCINATING Alex Ross story in the New Yorker looks at the incredible impact of Beethoven — has any artist reshaped his art form more? — and then acts if he has kept music from evolving. Here’s Ross on Ludwig van:

He not only left his mark on all subsequent composers but also molded entire institutions. The professional orchestra arose, in large measure, as a vehicle for the incessant performance of Beethoven’s symphonies. The art of conducting emerged in his wake. The modern piano bears the imprint of his demand for a more resonant and flexible instrument. Recording technology evolved with Beethoven in mind: the first commercial 33⅓ r.p.m. LP, in 1931, contained the Fifth Symphony, and the duration of first-generation compact disks was fixed at seventy-five minutes so that the Ninth Symphony could unfurl without interruption. After Beethoven, the concert hall came to be seen not as a venue for diverse, meandering entertainments but as an austere memorial to artistic majesty.

Ross, of course, has written how dangerous classical music’s shift to becoming an austere memorial has been; it’s one of the main themes of his excellent book The Rest is Noise. By making culture into a religion, Beethoven’s music (and classical music itself) set up expectations it could not fulfill, and guaranteed a stuffiness and sense of exclusion.

In the New Yorker piece he writes about the beginning of classical music as a backwards looking art form — it wasn’t always that way, folks! “In the course of the nineteenth century, dead composers began to crowd out the living on concert pr ograms, and a canon of masterpieces materialized, with Beethoven front and center.” It amounted, he writes, to “the shift on the concert stage from a living culture to a necrophiliac one.”

ograms, and a canon of masterpieces materialized, with Beethoven front and center.” It amounted, he writes, to “the shift on the concert stage from a living culture to a necrophiliac one.”

Of course, various art forms have had dominant figures who inhibited those who followed. Southern writers in the period after Faulkner have complained about the anxiety of influence, for instance. But the case of Beethoven has some specific difficulties for those who follow.

Part of it comes from a new notion of the genius — self-made, rather than by God — and the whole machinery of heroic/individualistic Romanticism.

Politics also assisted in Beethoven’s elevation. The disorder of the Napoleonic Wars, which redrew the map of Europe and ended the Holy Roman Empire, caused many to look toward music as a refuge. Amid universal chaos, Beethoven exuded supreme authority.

Much of Ross’s story is about the recent Beethoven bio by Jan Swafford (one of the most lucid writers on classical music) and some other books on the composer, including a novel. In any case, I commend the Ross essay to all of my readers.

October 15, 2014

Amazon and the New York Times

I REMAIN a dedicated fan of the Gray Lady, but its recent pieces looking for some “good news” in the Amazon fight struck me as bit strange.

Today I respond in a post for Salon. It begins this way:

In the careful-what-you-wish-for department: A bit more than a week ago, the New York Times’ public editor, Margaret Sullivan, urged her paper to bring some balance to its coverage of Amazon and bookselling. This is not, she wrote, the story of “good and evil” or “a literature-killing bully.” Her closing paragraph asked for a new kind of piece: “I would like to see more unemotional exploration of the economic issues; more critical questioning of the statements of big-name publishing players; and greater representation of those who think Amazon may be a boon to a book-loving culture, not its killer.”

She’s right, largely: The newspaper of record needs to work very hard to look at various sides of any issue it covers, even if the anti-Amazon side has made more noise lately. But so far the stories sympathetic to Amazon have been unconvincing at best. In fact, they’re starting to resemble the ass-covering pieces newspapers sometimes do to placate people in the fringes of an issue, like when nervous editors send out calls to find a scientist who doe

sn’t believe in global warming.

I also urge everyone to read Franklin Foer’s New Republic piece, which I refer to in mine.

Author Sven Birkerts on Culture Crash The Book

ONE of the first and most eloquent books on the transition away from the world of print to a new one dominated by digital communications came 20 years ago from the veteran literary critic Sven Birkerts. The Gutenberg Elegies: The Fate of Reading in an Electronic Age was funny, sad and prescient, and served as important foundation for my upcoming Culture Crash: The Killing of the Creative Class.

It makes me especially proud to have this endorsement from the great scribe:

“We’ve all had the feeling of these enormous changes — long in the making, not ‘at the last minute’ — but Scott

Timberg has the synthesis that makes them make sense. CULTURE CRASH throws a clear, defining light on the squeeze that digitally-based economies have put on our artists, the analog makers who have always defined us to ourselves. A hugely important book.” — Sven Birkerts

My book comes out from Yale University Press in January.

October 14, 2014

Is Amazon a Monopoly?

THE battle over Amazon — including the siege of Hachette — has heated up lately, with The New Republic’s Franklin Foer and several prominent authors, including Ursula Le Guin, calling the online bookseller “a monopoly.” Foer has argued that it’s time for the Department of Justice to break Amazon up.

This is from his TNR piece, “Amazon Must Be Stopped,” where he calls the firm a monopoly in his first few paragraphs:

That term doesn’t get tossed around much these days, but it should. Amazon is the shining representative of a new golden age of monopoly that also includes Google and Walmart. Unlike U.S. Steel, the new behemoths don’t use their barely challenged power to hike up prices. They are, in fact, self-styled servants of the consumer and have ushered in an era of low prices for everything from flat-screen TVs to paper napkins to smart phones.

In other words, we’re all enjoying the benefits of these corporations far too much to think hard about distant dangers. Besides, the ideology of Silicon Valley suggests that we have nothing much to fear: If these firms no longer engineer breathtaking technologies, they will be creatively destroyed… The Internet-age monopolies are a different species; they flummox our conventional ways of thinking about corporate concentration and have proved especially elusive to those who ponder questions of antitrust, the discipline of law that aims to curb threats to the competitive marketplace. Part of the issue is the laws themselves, which were concei

ved to manage an industrial economy—and have, over time, evolved to focus on a specific set of narrow questions that have little to do with the core problem at hand.

Whether Amazon, which does $75 billion in annual revenue, has technically violated antitrust laws is an important matter, of course. But descending into the weeds of predatory pricing statutes also obscures the very real threat. In its pursuit of bigness, Amazon has left a trail of destruction—competitors undercut, suppliers squeezed—some of it necessary, and some of it highly worrisome. And in its confrontation with the publisher Hachette, it has entered a phase of heightened aggression unseen even when it tried to crush Zappos by offering a $5 rebate on all its shoes or when it gave employees phony business cards to avoid paying sales taxes in various states.

The New York Times columnist Joe Nocera, whose work I like most of the time, has a column today that takes issue with Foer and the others. He begins by asking if Amazon is a monopoly, decides that it is not, and then moves to this:

The truth is that American antitrust law is simply not very concerned with the fate of competitors. What it cares about is whether harm is being done to consumers. Walmart has squashed many more small competitors than Amazon ever will, with nary a peep from the antitrust police. Even in the one business Amazon does dominate — books — it earned its market share fair and square, by, among other things, inventing the first truly commercially successful e-reader. Even now, most people turn to Amazon for e-books not because there are no alternatives but because its service is superior.

I’ll disagree with Nocera on a few points, including his line that Amazon earned its market share firmly: Amazon dodged sales taxes for years, setting up unfair competition that allowed it to crush brick-and-mortar bookstores that were not exempt.

But on the larger question of whether Amazon is literally and technically a monopoly: Probably not, but the distinction is not all that important. It’s a bully, it’s destroying important institutions, and it’s getting more and more powerful, and its founder now owns the dominant newspaper in the nation’s capital. Amazon controls roughly half the trade in books in the U.S. We may need a new word to describe what it is, but to sit around and debate terminology as we watch the creative destruction seems to me the worst kind of chattering-class hair-splitting.

October 13, 2014

Drummer Brian Blade

THE other night I was invited to the Silver Lake home of producer Daniel Lanois, who (best known for his work with Dylan, U2 and Emmylou Harris) has a new record of his own coming. I went partly because of the involvement of Brian Blade, mostly known as a jazz drummer.

Photo by Steve Hochman

Blade played with Wayne Shorter’s group at Disney Hall not long ago and stole the show. Lanois’s playing — piano, electric guitar, various kinds of electronic sounds — was often interesting, especially accompanied by abstract short films projected behind him, but Blade did it again: His understated playing and use of polyrhythms made me forget anyone else was in the room. Musicians: Beware of this guy. He is a dangerous figure who will subtly eclipse you.

I must admit that Lanois floored me and the rest of the crowd with his eerie and eloquent steel-guitar playing.

The Lanois record Flesh and Machine — and the man himself came across as a good-natured and sincere guy — comes out later this month on Anti- Records.

What Do Brunch and Jeff Koons Have in Common?

THE current backlash against mimosa-drenched Sunday meals is not a central concern of this blog. But I cannot resist posting part of a New York Times story (already denounced by some in my circle) which connects the rise of brunch with skyrocketing rents and the rise of the 1 percent. (Both, incidentally, major concerns here.)

This comes from “Brunch is For Jerks“:

There’s something more malevolent at work than simply the proliferation of Hollandaise sauce that I suspect comes from a packet. Brunch has become the most visible symptom of a demographic shift that has taken place in our neighborhood and others like it. As rents have gone up, our area has become unaffordable to much of the middle class, and to young families who want more than two bedrooms — or can’t even afford one.

This leaves an increasing number of well-off young professionals who are unencumbered by children — exactly the kind of people who can fritter away Saturday, Sunday or both over a boozy brunch. Our once diverse neigh

borhood now brims with the homogeneity of an elite university…

For me, having a child — and perhaps the introspection that comes with turning 40 — made me realize what most vexes me about brunch: Once the domain of Easter Sunday, it has become a twice-weekly symbol of our culture’s increasing desire to reject adulthood. It’s about throwing out not only the established schedule but also the social conventions of our parents’ generation. It’s about reveling in the naughtiness of waking up late, having cocktails at breakfast and eggs all day. It’s the mealtime equivalent of a Jeff Koons sculpture.

Though I don’t agree with every line of this piece, I applaud its concluding image.

October 12, 2014

Greil Marcus and the History of Rock N Roll

MANY of us interested in music, American history and culture in general discovered this scholar and scribe with one of his great early books like Mystery Train or Lipstick Traces. Marcus popularized the idea of using music as a “secret history” for other cultural forms, his book connecting Dylan’s Basement Tapes to Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music spread the notion of “the old, weird America,” and he’s overall too complicated and protean a guy to sum up succinctly.

Marcus has a new book — The History of Rock N Roll in Ten Songs — that’s drawn more attention than anything he’s done in a long while. The songs chosen range widely, from numbers associated with Etta James, Joy Division (right) and Amy Winehouse. I speak to him for a Salon Q+A today. You have to read past the headline and photos to see that this is mostly a story about rock music and the way songs change and mutate and take on new contexts; to Marcus, songs have a life — maybe lives — of their own.

and Amy Winehouse. I speak to him for a Salon Q+A today. You have to read past the headline and photos to see that this is mostly a story about rock music and the way songs change and mutate and take on new contexts; to Marcus, songs have a life — maybe lives — of their own.

Here’s my first question:

Let’s talk about “The History of Rock ‘n’ Roll.” It’s an understatement to say that, for you, a song is not just a number that was recorded once and that it belongs only to the first musician to perform it. What’s a song to you, and how does that work in this history of yours?

Well, I guess the way it works, in this book anyway, is that a song becomes a thing in itself. Yes, it’s written by someone, it’s performed by a person or a group and it goes into the world with various names attached to it. But it makes itself felt as a thing in itself, as its own object, as its own subject. People don’t necessarily know or care, and there’s no reason why they should, who the people making this record are, what their hopes and fears are, what their motives were, what situation in life they were in when the song came out of them, whether they were in a point in their career where they desperately needed a hit, or simply a matter of building on previous success, or if somebody was in rehab, or going through a divorce, or you know, had just signed up for a program to become an astronaut. People don’t know and don’t need to know any of that. That’s irrelevant.

The song becomes a kind of repeating event out there in the world, and people make of it what they will. And often the people who are listening are other musicians. Or maybe they’re not musicians yet or singers yet, but they want to be. And maybe it’s this song or any other song that’s made them want to do that. And maybe at some point in their lives that will happen. But in any case, musicians will take up these songs that are out there in the world and they’ll try to play them. They’ll feel that this song is not finished, this song, this story told isn’t complete, that they have something to add to this story, they want to feel, they want to understand and experience what it would be like to sing this song as if it were their own, as if they had thought of it, as if it comes out of them completely new.

Marcus goes all kinds of unexpected places in this interview — please check it out.

October 10, 2014

More Musicians Against Spotify

MOST of the coverage of musicians opposing streaming services — especially on this site — has concentrated on indie and alternative figures like David Lowery or Thom Yorke. But the suburban center has staked its claim now that Jimmy Buffett has come out against Spotify. From a Business Insider story:

At the Vanity Fair Summit conference Wednesday, Buffett asked Spotify CEO Daniel Ek what the streaming service is doing to make sure artists get their fair share of streaming music revenues.

“We’re at the end of the pipeline,” Buffett told Ek. “When money goes to the label in a stream, it trickles to the artist. Do you see anything in the future where we might get a raise from you instead of going through the bull — you have to with the labels these days?”

You can probably guess Ek’s evasive response.

You can probably guess Ek’s evasive response.

Not surprisingly, Spotify’s leadership is trying to show how artist-friendly they are; lately this means a series of we-love-you-people concerts in New York, LA and Nashville. A number of frustrated artists confronted Spotify brass at what the Music Tech Policy site is calling its “charm offensive” at New York’s Soho House.

Among the subjects the musicians raised: Tiny royalty rates, Ek’s role in founding the piracy-enabling Bit Torrent service before he started Spotify, and the fecklessness of music streamers in confronting brand-sponsored piracy. So far, Spotify and the rest have not had good answers to any of this.

October 9, 2014

The Winner-Take-All Culture: Beyonce’ Edition

NO, you’re not reading an article from the Onion, but rather a news report of an an extreme and literal instance of the winner-take all culture.

This brief story from Poynter, “News station lays off journalists, will play Beyoncé songs instead,” quotes Houston Chronicle  reporter David Barron:

reporter David Barron:

Radio One owns the station, known as News 92 FM. Its employees “were notified shortly after 9 a.m. Wednesday that the news format was being dropped and the station rebranded – for the moment – as B921, playing around-the-clock, commercial-free music by Beyoncé,” Barron reports.

Of course, I’m not worried about a larger wave of radio journalists being executed and replaced by overhyped R&B singers. But as a demonstration of where we are today, this is weirdly apt.

My soon-to-be-released book, Culture Crash, gets into the way the larger winner-take-all-society, which has been best described by Cornell economist Robert H. Frank, works out for the creative class. Until then, this example will have to do.

October 8, 2014

The Commodification of Cool

READERS of this blog know that one of my primary concerns is the way economic shifts — especially as they affect rents and the costs of living — have direct and profound meaning for the creative class. So I want to go back to The New Republic story on Berlin and other “cool” cities

But the greatest risks posed to the “next Berlin” are likely to stem from an international real estate market that has grown dramatically since the 1990s. As James Surowiecki detailed in a recent New Yorker, liberalized purchasing rules have allowed “a torrent of capital from wealthy people in emerging markets” to flow into various cities around the world over the past few years, with a special focus on “hotspots” like Berlin. This means much of formerly affordable, trendy neighborhoods like Neukoelln has been snapped up by faraway buyers in Ireland, Norway, or the United States. And this process only gained steam after the 2008 beginning of the euro crisis, as real estate became one of the safest forms of investment in Europe.

Margit Mayer, a professor of political science in Berlin who focuses on gentrification, says, “so many people from all over the world decided that Berlin’s real estate market had enormous development potential, and so they came here and tried to turn it over as quickly as possible.” And Peck points out that it’s no accident that international buyers are targeting Berlin—today’s buyers are well aware of a city’s burgeoning, or fading, reputation. “Cool is much more saleable now than it was in 1975,” he says. Ina recent documentary about gentrification in Berlin, a notorious Norwegian landlord who has bought up over 2,000 buildings in Berlin uses the city’s rampant graffiti as a way of convincing wealthy Italian buyers to purchase an apartment.

Similarly, a Baffler story looked at the city’s commodification of cool.

looked at the city’s commodification of cool.

The idea is to cash in on Berlin’s cachet by branding it as a “Creative City”—but it is also, to judge by what has happened, to gut public services, to sell off public housing, and to strategize about new ways of turning taste into profit. This new Berlin is a city where imaginative expression supports, directly or indirectly, a grand scheme for making a small number of people rich. One of these days, some lucky Berliners and expats will finally attract venture capital from London, Palo Alto, and Boston. But the others—the scenic poor and the clever unemployeds who make the city so attractive—will find it ever more difficult to make ends meet.

These shifts have an impact not just in Berlin but in every city where writers, musicians, artists and the creative class try to settle.

Scott Timberg's Blog

- Scott Timberg's profile

- 7 followers