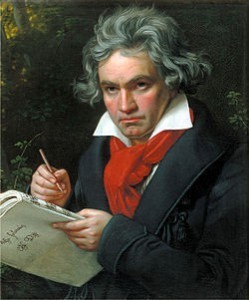

Was Beethoven a Bad Influence?

A FASCINATING Alex Ross story in the New Yorker looks at the incredible impact of Beethoven — has any artist reshaped his art form more? — and then acts if he has kept music from evolving. Here’s Ross on Ludwig van:

He not only left his mark on all subsequent composers but also molded entire institutions. The professional orchestra arose, in large measure, as a vehicle for the incessant performance of Beethoven’s symphonies. The art of conducting emerged in his wake. The modern piano bears the imprint of his demand for a more resonant and flexible instrument. Recording technology evolved with Beethoven in mind: the first commercial 33⅓ r.p.m. LP, in 1931, contained the Fifth Symphony, and the duration of first-generation compact disks was fixed at seventy-five minutes so that the Ninth Symphony could unfurl without interruption. After Beethoven, the concert hall came to be seen not as a venue for diverse, meandering entertainments but as an austere memorial to artistic majesty.

Ross, of course, has written how dangerous classical music’s shift to becoming an austere memorial has been; it’s one of the main themes of his excellent book The Rest is Noise. By making culture into a religion, Beethoven’s music (and classical music itself) set up expectations it could not fulfill, and guaranteed a stuffiness and sense of exclusion.

In the New Yorker piece he writes about the beginning of classical music as a backwards looking art form — it wasn’t always that way, folks! “In the course of the nineteenth century, dead composers began to crowd out the living on concert pr ograms, and a canon of masterpieces materialized, with Beethoven front and center.” It amounted, he writes, to “the shift on the concert stage from a living culture to a necrophiliac one.”

ograms, and a canon of masterpieces materialized, with Beethoven front and center.” It amounted, he writes, to “the shift on the concert stage from a living culture to a necrophiliac one.”

Of course, various art forms have had dominant figures who inhibited those who followed. Southern writers in the period after Faulkner have complained about the anxiety of influence, for instance. But the case of Beethoven has some specific difficulties for those who follow.

Part of it comes from a new notion of the genius — self-made, rather than by God — and the whole machinery of heroic/individualistic Romanticism.

Politics also assisted in Beethoven’s elevation. The disorder of the Napoleonic Wars, which redrew the map of Europe and ended the Holy Roman Empire, caused many to look toward music as a refuge. Amid universal chaos, Beethoven exuded supreme authority.

Much of Ross’s story is about the recent Beethoven bio by Jan Swafford (one of the most lucid writers on classical music) and some other books on the composer, including a novel. In any case, I commend the Ross essay to all of my readers.

Scott Timberg's Blog

- Scott Timberg's profile

- 7 followers