Scott Timberg's Blog, page 34

June 20, 2014

The False Promise of Digital Publishing

WHAT does it mean to be a digital bestseller? We continue to hear that removing the middleman and getting rid of the expenses of print will be good for readers and writers. The experience of Tony Horwitz, a first-rate writer of narrative nonfiction like Confederates in the Attic, shows it doesn’t always work out that way. He calls his story , “a cautionary farce about the new media and technology we’re so often told is the bright shining future for writers and readers.” Horwitz continues:

, “a cautionary farce about the new media and technology we’re so often told is the bright shining future for writers and readers.” Horwitz continues:

As recently as the 1980s and ’90s, writers like me could reasonably aspire to a career and a living wage. I was dispatched to costly and difficult places like Iraq, to work for months on a single story. Later, as a full-time book author, I received advances large enough to fund years of research.How many young writers can realistically dream of that now? Online journalism pays little or nothing and demands round-the-clock feeds. Very few writers or outlets can chase long investigative stories. I also question whether there’s an audience large enough to sustain long-form digital nonfiction, in a world where we’re drowning in bite-size content that’s mostly free and easy to consume.

To the digital utopians, remember, we live in the best of all cultural worlds.

June 19, 2014

A Dissent on “The Classical Style”

AS I posted the other day, this year’s Ojai Music Festival was full of good stuff. But there was one piece that frustrated me: The new opera, The Classical Style, which was for many the highlight of the weekend. Why did it drive me crazy?

The Classical Style: An Opera (of Sorts) is the first opera commissioned in the seven-decade history of the festival; it’s based on a well-regarded book by late music scholar and pianist Charles Rosen.

Jeremy Denk, who inaugurated the work and wrote the libretto, is not only one of the great musicians of my generation, he’s known as one classical music’s premiere writers and intellectuals as well. (I’ve written this myself and still believe it, and it was a real thrill to see him play Ives and others this year.) Steven Stucky, who wrote the music, is among the finest contemporary composers: His music – some of which was a pastiche of classical-era pieces or music that sounded like it could have come from the 18th century – was consistently strong. Some of the singers were very good, too.

Otherwise, this opera seemed a missed opportunity. At the risk of sounding grumpy, I expected more from talents of this caliber.

Is it possible to make an opera out of a critical study? Maybe; I can imagine, say, an intriguing work of some kind springing from, say, Leslie Fiedler’s Love and Death in the American Novel, or Leo Marx’s The Machine in the Garden; maybe something by Susan Sontag.

But what we got here – besides a few winning moments, such as the love triangle/harmony lesson in which a singer playing the Tonic is pursued by a Dominant and in turn yearns for a lovely Subdominant – is an oddly anti-intellectual batch of bad puns and inside jokes.

It’s hard to describe The Classical Style any more fully, because it’s such inside baseball. Denk clearly admired Rosen (an eloquent writer, in the New York Review of Books and elsewhere, also known as a difficult, dismissive guy) and tries to bring him alive as a kind of last-of-his-breed New York intellectual.

Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven wander through the play, lamenting that they are not only dead, but speakers of a dead language. A nerdy, Berkeley-school musicologist shows up and pontificates, to the delight of many, but giving the whole opera a sense of score-settling. (I have my own problems with theory-obsessed academics, but this did not engage the issue in a smart or original way.) Some of the rest was too clever by half; most of it was pretty insular. I even got the jokes, but wonder: Does this speak to anyone but classical-music and opera insiders?

Colburn School musicologist Kristi Brown gets at just how mixed up the damn thing is here.

Without the libretto in front of me it’s hard to point to specific faults, but it’s easy to recall what wasn’t there in The Classical Style.

A few weeks ago, I saw an opera in Los Angeles – Massenet’s Thais – that is on nobody’s list of the world’s very finest works. But it was about themes that still connect with our lives today – lust and luxury versus spiritual hunger – as well as a historical period in which many gods were giving way to one. Even as a lifetime agnostic, I found it deeply moving.

Cosi Fan Tutte – the opera responsible for turning me on to the form – is comic, but it’s about something human as well: Love, deception, sex, the contradictions of monogamy. Another opera I’ve seen in the last year – Einstein on the Beach – is more abstract, but it’s profound in its own oblique, minimalist way.

Part of my response to The Classical Style may come from the fact that I grew up in a jock-ish suburban world with little interest in high culture. (My parents and a few teachers were the exception.) And while I write about the fine arts professionally, I live in the shadow of a couple Hollywood studios, and most of my peers are into rock music and mainstream movies and Game of Thrones.

I’m also increasingly aware, as I watch theater companies tank, classical groups go under and publishing houses lay people off, that the audience for the traditional arts is not exactly thriving. (This is the place, by the way, where my opponents attack me for being a middlebrow nostalgist.)

I wasn’t born into a classical-music world, but I found something profound in the music that wasn’t happening elsewhere. And I don’t want inside jokes to be required for others enjoying contemporary music. I want to be able to tell people that it’s worth moving away from pop culture — at least some of the time — to find something deeper and richer, smarter and more sophisticated. (Like Rosen, and Denk, I think, I want to see Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven speak to us again, though I will hold onto my Shostakovich and Clifford Brown and Clash records, too.)

Does opera or poetry or whatever, then, all have to be earnest and portentous? Of course not, and this year’s festival included a few smutty Mozart numbers that reminded us that the sacred and the profane have often existed in tandem in the classical tradition. That’s fine; I get it.

But to have an entire opera, written by two near-geniuses, that’s the centerpiece of one of classical music’s premiere festivals, feel so emotionally empty, so dismissive, so insular — and perhaps worst of all, funny only in an Adam-Sandler-goes-to-conservatory kind of way — saddens me.

It forces me to say to the millions of Americans who think the fine arts are worthless, and that culture vultures are a bunch of self-absorbed toffs: Well, maybe we should just all stay in and watch TV after all.

June 18, 2014

RIP Horace Silver

WELL, this time it seems to be for real: Jazz pianist, songwriter and founding Jazz Messenger Horace Silver has died at 85. Silver’s recordings, under his own name and in his 1950s group with Art Blakey, were some of the first jazz I got into, and I’ve been marveling at his genius all over again since I’ve learned to play his “Song for My Father” on guitar.

Here is the NPR report.

I don’t love the sound on this, but I’ve linked to a live performance from Copenhagen. My band will tackle this one in the garage later this week.

What struck me originally about Silver’s music is his soulfulness — his style comes out of the church and the blues, as well as Cape Verde — and his effortless melodicism. He’s one of the key figures of hard bop — perhaps its founder.

The great Horace Silver will be missed!

How Silicon Valley’s Disruptors Defend Themselves

I EXPECT the big car companies were as defensive, back when reformers suggested seat belts and the like, as digital-disruptor types are when they receive any bit of criticism. In this case, the Silicon Valley types lash back that anyone who doesn’t buy their cyber-utopian vision is “anti-technology.”

Salon’s Andrew Leonard gets into this quite well in a short piece about the digital boys’ reception to Jill Lepore’s recent story . She argues that “disruption theory” is full of holes and bad assumptions, and was immediately tarred as a Luddite. Here’s Leonard:

. She argues that “disruption theory” is full of holes and bad assumptions, and was immediately tarred as a Luddite. Here’s Leonard:

It’s possible to be critical of the way Silicon Valley is agitating for regulatory reform that is designed to nurture Silicon Valley business models without being “anti-technology.” It’s possible to explore the question of how the current pace of technological innovation is affecting jobs and inequality without being anti-technology. It is possible to be critical of how, in the current moment, technology appears to be serving the interest of the owners of capital at the expense of workers without being anti-technology. It’s even possible to love one’s smartphone and the Internet while at the same time critiquing run-amok “change the world” hype.

The whole fight reminds me of something Paul Krugman has said: The enthusiasts of creative destruction always think it will be someone else getting destroyed. Someday, it will be their turn.

June 17, 2014

Taking Stock of the Ojai Music Festival

Libbey Park’s Gazebo

Music director Jeremy Denk is both a consummate interpreter of Charles Ives and an advocate for the New England maverick, so we got a good dose of his ornery modernism this year.

Given Ives’ originality and weight — perhaps our nation’s first important composer — he remains underperformed in most places in America. He was often neglected or misunderstood in his lifetime; his use of pastiche and musical collage and various avant-garde techniques makes him betted suited to ours. In any case, it was a pleasure to see so much Ives — including the violin sonatas (performed with the hymns that provided some of their melodies) and Three Places in New England.

Besides Denk himself (who played on the violin sonatas), the young composer Timo Andres spent a lot of time on the piano bench. His recomposition of Mozart’s Coronation Concerto — there are many blank spots for the left hand on Mozart’s original — was one of the weekend’s highlights for me.

Jeremy Denk

Kurt Weill was another composer who showed up more than once at the festival. The Seven Deadly Sins (libretto by Brecht) was a lot of fun, and well sung by bombshell Storm Large, portraying a woman who experienced all seven and then some, and quartet Hudson Shad.

Storm Large in Seven Deadly Sins

I missed the Sunday-morning-at-8 Hymnfest on Mediation Mount, but heard it was powerful. Last year’s equivalent was a real highlight for me.

The mix of canonical works (Mozart’s Jupiter, Haydn’s quartet) and new or cutting-edge work worked for me. That said, there was no single piece this year that knocked me out, but I missed some stuff. Mark Swed went to just about all of it; here it his wrap-up.

Ojai remains an absolutely lovely spot, especially Libbey Park, where much of the festival takes place, and the festival is smoothly run: You see what can happen when a community gets behind an arts event. We’re already looking forward to next year.

Caveat: While I’ve reviewed books, jazz records and rock bands, I am not a professional critic but an culture reporter and enthusiast of the arts. I have linked to a credentialed critic; the distinction does, to me, matter.

June 13, 2014

World Premiere: Donald Margulies’ “The Country House”

IS there a wittier writer working today than Donald Margulies? Could be, but the New Haven-based, Pulitzer-winning playwright is so consistently on in his best work, and his brand-new play, The Country House, which I caught on opening night at the Geffen Playhouse, is often irresistibly funny.

The play is set in a big, open house occupied, for this weekend, by two generations of actors, including a television star asserting his serious-theater credentials by appearing at the Williamstown Theater Festival. (Blythe Danner plays the family matriarch.)

My friend and colleague Charles McNulty, whose take on the play resembles mine pretty closely, picked up numerous echoes of Chekhov, including individual characters who have precursors in works like The Seagull and Uncle Vanya.

If it can’t compete with these dramatic masterpieces, well, nothing written in the last 100 years can. Chekhov’s supple artistry — at once invisible and palpably present — is so inextricably tied to his fearless yet humane worldview that copying his example would be as impossible as counterfeiting fingerprints.

There’s a good deal of fun in the attempt, however, especially in the first half when the play is in flamboyant comic mode. (The move to more serious psychological drama late in the second half comes off as ponderous.) Chekhov’s characters are adept at laughing through tears. Margulies’ are most memorable when cracking wise about the theater.

Here are a few of my own observations:

It is hard to imagine the cast being improved: Everyone seemed dead-on to me.

As strong and delightful as this play is, it could probably benefit from losing 10 or 20 minutes, and I agree with McNulty that the final act doesn’t work as well.

The Geffen Playhouse, where I’d not been in a few years, is one of the few things worth the long rush-house slog to the Westside. Opening night there really feels like an event. Excitement about the new Margulies play was palpable.

Despite the parallels to Chekhov, you don’t have to have memorized The Cherry Orchard to enjoy The Country House. The new play lacks the sense of sweep and understated poignancy you get in Chekhov.

Many of Margulies plays are about artists of various kinds, and the writers are always egomaniacs, the actors are shallow and manipulative, and so on. He is in some ways a satirist. But I spent a few hours with the playwright — who recently finished adapting a film about David Foster Wallace — and he’s not cynic. We went to the Orange County Museum of Art for a Diebenkorn show, and Margulies was rapt. His plays work, I think, because he has a complex — both reverential and demystified — sense of the creative process and the people who engage in it.

The Country House will head to Broadway. See it now in LA while you can.

June 12, 2014

Memories of the Sasquatch! Music Festival

TODAY I am going to take a break from spreading bad news about the world of culture to offer some photographs of rock and hip-hop musicians.

First Aid Kit

These shots are by Steven Dewall, an old colleague and friend, and former resident of Seattle, who travels back every year for the Sasquatch! festival and photographs a huge range of bands alongside the Columbia River Gorge. (For what it’s worth,while Steve’s first commitment is to photography, he’s also a serious music fan of long standing, and plays drums in the indie-rock group I run out of my garage.)

Jonathan WIlson

Brody Dalle

Alisa Xayalith of The Naked & Famous

Foy Vance

De La Soul

If you’d like to see more work by Steven Dewall, music oriented or otherwise, check out his site here.

CultureCrash is hoping to be able to offer the usual run of bad news tomorrow.

June 11, 2014

LA Artists of the ’60s at LACMA

FOR the next few weeks, we have an unusual and probably accidental correspondence: Two important but often unseen artists of Los Angeles’ great 60s flowering are up at the LACMA. For admirers of John Altoon — one of the original Ferus Gallery bad boys — and Helen Pashgian, a pioneer of the Light and Space movement — it’s a rare chance to see their work.

The Altoon show just opened over the weekend. Altoon was a jazz-loving Beat as well as a manic-depressive who spent time in Camarillo; as Hunter Drohojowska-Philp describes in Rebels in Paradise, the document of ’60s LA art, he also pulled a knife on his dealer Irving Blum.

For those of us who know Altoon’s reputation — his death at 43, in 1969, sent shock waves through the scene — his work is hard to make sense of at first. He was either trying on different styles, or so restless he was not interested in a single, fixed artistic identity. To my eye, he hit hist stride about halfway through the work in the LACMA show, as he drew from pop art (parodying advertising) and using sexual imagery that I cannot reproduce here. LA Times critic Christopher Knight frames him as one of the artists of the ’60s sexual revolution. From his review:

Sex is also an obvious tool of mass-media commercial art, flooding late-20th century America, with which Altoon was well-versed. Several satirical works play with advertising motifs.

One shows a dapper young couple in a White Owl cigar ad: He smokes, she pouts. Rather than focus on a close-up as a conventional ad would, Altoon pulls back (like a reverse camera-zoom) to show the fashionable pair full-length: Both are stark naked below the waist. The cigar scene turns into an ad for post-coital relaxation.

I found the De Kooning-inspired abstract work less interesting. But anyone who follows the origins of Southern California’s art scene should see this show.

Pashgian, similar, is someone who’s talked about as part of the Light and Space crowd, but I’m not sure I’d ever seen an y of her work. One gallery in the LACMA’s Art of the American’s building is given over to a serene installation called Light Invisible (right), in which she tries to conjure the distinctive quality if LA’s light, here using 12 columns of molded acrylic. She’s still alive, but keeps a low profile these days and refuses to reveal her age. See the installation before it’s gone.

y of her work. One gallery in the LACMA’s Art of the American’s building is given over to a serene installation called Light Invisible (right), in which she tries to conjure the distinctive quality if LA’s light, here using 12 columns of molded acrylic. She’s still alive, but keeps a low profile these days and refuses to reveal her age. See the installation before it’s gone.

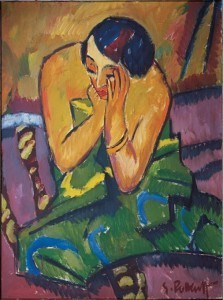

New at LACMA is a large show of French and German Expressionism, Van Gogh to Kandinsky. I spent a lot of time in this show — I especially liked the work by Kirchner and the Blue Rider artists — and could have easily taken twice as much time. Some of the French work is pretty familiar, but many of the German paintings were fresh and arresting.

“Reflective Woman,” Karl Schmidt-Rottluff

What if Music Streaming Collapses?

MOST critical coverage of Spotify, Pandora and the like has concentrated on the frustration of musicians. But a tough, provocative new piece asks, What if these streaming companies simply fail to make profits, and disappear? Here is Michael St. James — extending the recent David Carr story — on RebelMouse:

Not one of the music streaming companies has made a profit yet, not one. Most are involved in corporate growth quarterly suicide, driven by large sums of VC money, or public pressure to return shareholder value. That’s fine, but that’s no way to nurture a creative company. I wish them all well, but honestly, that doesn’t seem like a good situ

ation for the industry or consumer, maybe the VCs and shareholders, and money managers, but not us.

Streaming is sort of the second (or third) wave of digital disruption. First came Napster and related piracy, then came paid downloads on iTunes and the like; both helped chip away at sales, though iTunes brings in some revenue. Streaming has continued the process: it earns some revenues, some of which reach musicians, but record sales and even downloads have fallen as that’s happened.

St James speculates what could happen next. “There is no guarantee that any of these companies will be around by the end of the year,” he writes. “I know that’s hard to believe, but they could, literally, just close up shop, count the money and go home.”

If that happened, it would be a bit like the the Border’s that came to town, wiped out your local indie bookstore, and then folded up itself a few years later. Or the Wal-Mart that arrived on the edge of your city and destroyed the mom and pops on Main Street. (In some cases, as Douglas Rushkoff has documented, the government, and your tax dollars, paid to knock down Wal-Marts that didn’t make it.) Digital disruption won’t discriminate — it will destroy just about anything in its path. It could be your favorite shop, or your job, next.

June 9, 2014

The Ojai Music Festival and Uri Caine

LATER this week, one of our spring rituals arrives: The Ojai Music Festival kicks off on Thursday. It’s always a good time up there, and this year we’re doubly excited because of the artistic directorship by pianist Jeremy Denk, one of my generation’s most imaginative players, a gifted writer of prose on his blog and elsewhere, and a great advocate for Ives.

There’s always a lot to see at Ojai, but for now we want to talk about two performances by longtime jazz pianist and downtown experimentalist Uri Caine.

California’s lovely and gentle Ojai Valley does not put us in the mind of the brooding Austrian Gustav Mahler, but that’s part of what Caine has cooked up for the festival. He’s developed a cottage industry interpreting classical composers in an improvised setting – Schumann, Beethoven, Bach, even Vivaldi – and he’ll present Mahler Re-Imagined as part of the festival’s Thursday night opening concert. (Caine will also interpret Gershwin Friday night with his sextet.)

Caine is aware that Mahler is not known for being light-hearted, and his music – even compared to other classical figures – doesn’t exactly swing. With all that rubato and agony, he’d not be the first to come to mind first for a jazz-oriented treatment. But he’s more complicated than his reputation, according to Caine.

“There are a lot of different traditions happening in Mahler,” Caine told me from a tour through Spain. “Mahler is using all these elements, and as improvisers we use them as jumping-off points. Bohemian folk music, military music he heard growing up, funeral marches, and the music he studied and conducted – Wagner, Mozart. He could be simple and folk-like or very violent, very merry and very bleak.”

Mahler’s synthesis of different styles confused people at the time, Caine says, but his fragments and allusions make him in some ways a man for our postmodern times. Of course, the composer’s work is still not universally loved. “One thing people don’t always like in Mahler is that he goes off on some many tangents; he’s trying to develop so many different themes. As improvisers we do the same thing.

Caine’s taste is catholic and wide-ranging, but that doesn’t mean he treats every composer’s work the same way. In fact, he insists that he pays enormous attention to the differences between each figure. “It has a lot to do with listening to the music, and then, like a student, trying to understand it. Letting the impressions dictate where you go with it,” observing the underlying structure, and then seeing what his bandmates respond to in their improvisations.

And while he knows some classical folk – musicians, audiences and critics alike – don’t see improvisation and classical music have anything to do with each other, he disagrees vehemently. “There is a tradition of improvisation in classical music that’s atrophied now,” he says. But Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, and Chopin were great improvisers. “In the old days before records, people were basically writing out piano improvisations.” Cadenzas, especially, were typically improvised in concert. “Sometimes when modern composers try their own cadenzas, people are scandalized. But that’s the point!”

Still, the tradition Caine and his players work in – improvising over chord changes – comes more directly from jazz; he’s especially impressed with the styles developed by John Coltrane (with its “swirling” quality and sheer speed), Miles Davis (for its understatement and apparent simplicity) and tenor saxophonist Joe Henderson (for its swing and sense of humor.)

Far closer to jazz than Mahler is the work of George Gershwin. Caine will also be reimagining the music of Gershwin, including Rhapsody In Blue, at Ojai. Gershwin was a bit like Mahler, he says, a synthesizer who brought a number of styles together – “Rachmaninoff, klezmer with the clarinet, a bit of Latin at the end.

Like a lot of jazz musicians, Caine spent his early years jamming on the changes to “I Got Rhythm” and other Gershwin songs, so it was natural for him to come back to one of his earliest sources.

“He was an amazing pianist, able to absorb ragtime and a lot of the New York players. You hear stories of him as a teenager, working for Irving Berlin – he was already a prodigy.” He differed from some of his contemporary songwriters in the Tin Pan Alley and Broadway orbits in being more steeped in jazz harmony, and by “self-consciously imitating a lot of classical composers – the Russians, the French – with added 6ths, added 9ths, moving by major 3rds.” And of course, much of his music drips with the blues.

Caine laments that Gershwin, who left so many great songs – “They Can’t Take That Away From Me” and “Our Love is Here to Stay” are two favorites — died so young, at the age of 38 from a brain tumor.

“He lived long enough to play tennis with Arnold Schoenberg,” Caine says. The Austrian composer, he imagines, “probably looked at George Gershwin and said, ‘America is an amazing country.’ “

CultureCrash looks forward to seeing you at Ojai.

Scott Timberg's Blog

- Scott Timberg's profile

- 7 followers