Scott Timberg's Blog, page 32

July 15, 2014

What Are Humans Good For?

WELL, folks, it’s gotten to the point where we’ve gotta ask this question. With various kinds of automation and AI replacing human labels even at the most cerebral and professional level — it’s not just bank tellers any more — we’ve got to ask, What can humans do that a computer or algorithm can’t?

A new Slate story notes that both the Associated Press and the LA Times are automated some of its stories (on corporate earnings reports and earthquakes, respectively) but takes an optimistic, it-won’t-happen-to-you point of view. Slate technology writer Will Oremus points out that these are the kind of rote stories that reporters don’t like doing, and argues that journalists should be okay.

First let’s look at what humans do well. We’re good at telling stories. We’re good at picking out interesting anecdotes and drawing analogies and connections. We’re good at framing information: We can squint at the amorphous cloud of information that surrounds a news event and discern a familiar form. And we have an intuitive sense of what our fellow humans will find relevant and interesting. None of these qualities come naturally to machines.

He breaks down, throughout the piece, what humans do better vs. what bots do better. This story is well-argued and intelligent. Let me point out, though, that when a profession is redrawn by technology, it often unfolds in ways that are hard to predict. The technology experts I’ve spoken to on the subject have argued that the power of AI and various software is increasing exponentially. A lot of people — even well-educated, highly skilled people — will now know just how serious the problem is until they find themselves replaced or their employer ruptured beyond repair.

By the way, a new report shows newspaper reporters among the most endangered jobs, alongside meter readers and travel agents.

July 14, 2014

More Bad New For Authors

BOOKS and publishing seems to be coming to terms with creative destruction these days much as musicians began to a few years back. The latest batch of bad news comes from the UK, in which a survey shows that authors have lost significant financial ground over the last eight years and make, on median, about 11 pounds, below Britain’s equivalent of the poverty rate. Here‘s The Guardian:

According to a survey of almost 2,500 working writers – the first comprehensive study of author earnings in the UK since 2005 – the median income of the professional author in 2013 was just £11,000, a drop of 29% since 2005 when the figure was £12,330 (£15,450 if adjusted for inflation), and well below the £16,850 figure the Joseph Rowntree Foundation says is needed to achieve a minimum standard of living. The typical median income of all writers was even less: £4,000 in 2013, compared to £5,012 in real terms in 2005, and £8,810 in 2000.

Novelist Will Self recently complained about the situation, and this data bears him out. Of course, it has never been easy to make a living a a writer — or any other kind of artist — but these numbers show a steep drop. And it’s not limited to the UK: A few years ago, my then-agent told me to expect — thanks to online bookselling and the economic slump – an advance about half of what I would have drawn before the recession. (For a serious book by a non-celebrity writer, the numbers were not typically all that high, so slicing them up makes it hard to commit to a project unless the author is independently wealthy.)

As with any members of the creative class, the writers who earn the most get the vast majority of media coverage, ske wing public perception about what it’s like to write for a living. “Most people know that a few writers make a lot of money,” poet Wendy Cope told the paper. “This survey tells us about the vast majority of writers, who don’t. It’s important that the public should understand this – and why it is so important for authors to be paid fairly for their work.”

wing public perception about what it’s like to write for a living. “Most people know that a few writers make a lot of money,” poet Wendy Cope told the paper. “This survey tells us about the vast majority of writers, who don’t. It’s important that the public should understand this – and why it is so important for authors to be paid fairly for their work.”

Tom Perrotta’s “The Leftovers”

RECENTLY I spoke to the author of the novel HBO has adapted into a Sunday-night series. Both the novel and the show concern a small town from which a small but significant number of people have mysteriously vanished; most of the storytelling concern the way people deal in various — and variously conflicting ways — with the loss. And as you may’ve picked up, if you’ve seen the show, the series has a different — much grimmer — tone than the novel.

Here is my Q+A with Perrotta, a smart and lucid guy whose novels I like a lot. I was traveling last week, so this is posted a bit late.

July 12, 2014

R.I.P., Charlie Haden

THE great jazz bassist, long ailing, died Friday at 76. Even for those of us who knew how sick he was — he had post-polio syndrome — the loss is brutal. So many musicians played with him, live or on record, or studied with him at the program at CalArts. Ornette Coleman, Keith Jarrett and Brad Mehldau are only a few of the best known.

Here are some thoughts on Haden provoked by a December concert that many of us suspected would be Haden’s final public appearance. He was feisty on the stand, and played bass like an angel.

Angelenos know this, but it may surprise outsiders to know that Haden and his wife raised four really distinctive and wonderful musicians: Josh, who heads the band Spain, and the triplets Petra, Tanya and Rachel. Here is a piece by Don Heckman from 2011.

All of us — fellow musicians, family members, and listeners — will miss Charlie Haden.

July 8, 2014

Art for the Uber-rich

DESPITE the struggles of many visual artists, not to mention the stagnant middle class in the Anglo-American world, art’s auction market continues to boom. The latest story from the New York Times, on the London auction season, has some interesting details.

“The sleepy days of collecting are over,” said Amy Cappellazzo, the co-founder of the New York-based Art Agency, Partners, who was in London bidding on works by Lucio Fontana and Roy Lichtenstein on behalf of clients she advises. “The wealthiest of the wealthy now view art as an alternative currency. It’s become a very big business.”

There are apparently something like 36,000 artists in the international auction market for contemporary art. W e see a winner-take-all economy – not unlike the larger US or British economies — taking shape:

e see a winner-take-all economy – not unlike the larger US or British economies — taking shape:

Anders Petterson, the founder and managing director for the London-based analysts ArtTactic, said in an email that the 10 most expensive artists accounted for 73 percent of the £192.6 million aggregate total achieved at Sotheby’s and Christie’s evening sales.

It’s true not just of high yielding artists like the late Francis Bacon (whose work is pictured), but of the people buying, too. “In other words,” writes Times scribe Scott Reyburn, “despite all the media reports devoted to the relentless growth of the art market, that night at Christie’s it remained the preserve of the 0.1 percent of the 0.1 percent.”

July 7, 2014

Steve Martin and the Steep Canyon Rangers

BY now it’s pretty well know that the comedian best know for “King Tut” and the arrow through the head is not just another show-business dilettante: This dude is a real and committed musician. But even with high expectations, I was pleasantly surprised by the strength and seriousness of Martin’s banjo playing and the bluegrass group he sometimes leads, North Carolina’s Steep Canyon Rangers. I saw them as part of a 4th of July celebration at the Hollywood Bowl, with Edie Brickell as singer for some of it. (Her estranged husband Paul Simon came out for a fairly puzzling cameo.)

Martin offered a few jokes — winningly — in his famous dry-ice style. But he was mostly at the Bowl to play; he’s been playing the banjo onstage since the ’70s and is clearly drawn to its lonely and mournful resonances especially. Martin is a complex guy, and it’s not hard to see how this music, with its emotional highs and lows, and the sense of communion playing in a group offer s, would appeal to him.

s, would appeal to him.

Some of the highlights included one of his earliest numbers, “Daddy Played the Banjo,” a tribute to Pete Seeger — “Gentleman Pete” — and the Brickell-sung number, “When You Get to Asheville,” that opens their 2013 album, Love Has Come For You. (As much as I liked the performance of the song, I wish they could have found a better second line for a pining song of rural nostalgia than “Send me an email.”)

The Rangers were strong all around. But it’s hard not to single out the fiddle player, Nicky Sanders, who drew my attention even before a long bravura solo near the show’s end, where he seemed to play a bit from almost every genre of music imaginable. I was happy to bump into the dude on the way out and to shake his hand.

For what it’s worth, the Air Force band that opened the show was not terribly inspiring, and the film music they played was not exactly at the level of Bernard Herrmann or Ennio Morricone. But between Martin’s group, the fireworks, and the Bowl’s serene setting, it was a wonderful night altogether.

July 3, 2014

Taking on Amazon

THERE’S been so much bad news as the online Goliath has crushed bookstores and tangled with publishers, that it’s nice to see a bit of silver lining. Two new developments make us smile a bit here at CultureCrash, where we are too often locked into a grim expression.

First, a talented first-time novelist has received an unlikely bounce from Stephen Colbert, who used Edan Lepucki’s new book as an example of the battle’s stakes. Reports the New York Times:

“We will not lick their monopoly boot,” he said of Amazon on “The Colbert Report” before exhorting viewers to preorder Ms. Lepucki’s post-apocalyptic “California” from independent bookstores. The Amazon-Hachette brawl, Mr. Colbert explained, “is toughest on young authors who are being published for the first time.”

This is a great stroke of luck for Lepucki, of course. But I read the book a few months ago, before it came out — I interviewed her for a panel on California literature — and have known her casually for a little while. (She and her husband were clerks at Book Soup in West Hollywood when I lived nearby; truly good people.) So I’ll say: While she was as unsure as most first-time novelists, it didn’t take a genius to see that this post-apocalyptic domestic novel could easily catch on. I’m glad it has.

More broadly: European nations have done a more assertive job at fighting back against Amazon; they’ve got a longer experience defending what they see as their heritage, and have faced up to the damage created by a raw, unregulated cultural marketplace. The French government has now passed a bill to protect small bookstores against online booksellers, Amazon reports:

This new law has roots in the “Lang Law,” which was passed back in 1981. As part of that law the French minister of culture established a fixed price on books in order to aid independent bookstores competing with giant retailers, reports TechCruch. Similar laws then cropped up all over Europe — including in Italy, Portugal, Spain and Germany… According to Raw Story, France is particularly proud of its network of bookstores, calling them “unique in the world.”

No we Americans are heading into a holiday to celebrate what makes out nation great. Sadly, though the USA has produced many great writers, publishing houses, even bookstores, we’ve not done a terribly good job protecting them. Let’s hope we learn as we see how the world is changing.

And wishing all CultureCrash readers a good 4th and a restful holiday weekend. I will be partaking of some of my favorite American traditions — drinking what I expect will be a California wine as we watch Steve Martin lead his bluegrass band at the Hollywood Bowl.

Great Animated Short

TRAGEDIES like the Japanese-American internment during World War II can be hard to render artistically. So I’m especially surprised that a college student turned out a short animated film as powerful and understated as Yamashita. I met the student, Hayley Foster, recently to discuss her work as an animator and her ambitions to do more projects that look at issues of social justice. (She also spoke about her love of the films of Hayao Miyazaki such as Spirited Away.)

Foster, who now works at Warner Bros., is one to watch. Here is my story for the online magazine of her alma mater, Loyola Marymount University. It includes a link to the film’s trailer.

July 2, 2014

Culture and Monopoly

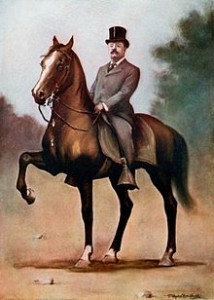

WHAT would Teddy Roosevelt do? I know I’m not the only arts observer who wonders where the anti-trust boys — the Department of Justice, for instance — are when a tech company takes over an enormous share of a culture industry. Amazon owns about two thirds of the market for digital books, for example, and the DoJ ruled in favor of them in a recent case involving old-school publishers (and Apple.)

And we’re seeing something almost as twisted as this as Google intimidates independent labels with its YouTube music-streaming service. In most of these negotiations, the tech companies hold all the cards, and can do nearly whatever they want.

How did cultural monopoly get so pervasive, a century after TR’s trust-busting? Two recent stories help clarify things a bit.

The first is a really excellent piece by Steve Coll in the New York Review of Books. It’s ostensibly a review of Brad Stone’s book on Amazon, The Everything Store. On the antitrust front, Cool says, things have changed significantly since the 1940:

Since then, politics and antitrust jurisprudence have shifted to favor consumers and large corporations at the expense of small producers. On the political left, a consumer rights movement emerged in the late 1960s as a response to dangerous automobiles and corporate pollution. That movement gave consumers priority over small businesses in challenging powerful corporations. On the right, free-market ideologists built think tanks and long-term legal strategies to defeat business regulation of all kinds and to reduce the scope of antitrust enforcement from its expansive Progressive-era origins.

From the Reagan presidency onward, the right succeeded remarkably. Large corporations perfected their lobbying power in Washington while small businesses like bookstores and corner grocers watched their political influence and their hold on the American imagination fade. The United States today presents a more bifurcated economic landscape of empowered, atomized, fickle, screen-tapping consumers and the globalized, often highly profitable corporations that aspire to serve them.

In Europe, he writes, things are different, with small businesses exerting real political pressure. “Crucially, these patterns of resistance to the digital age’s speed-of-light patterns of creative destruction,” he writes, “have a political foundation—they are popular at election time. This is not the case in the United States, which lacks a politics favoring small- and medium-sized cultural producers, whether these are authors, journalists, small publishers, booksellers, or independent filmmakers.”

Please — read this story.

The second is a very different piece, a conversation between Salon columnist Thomas Frank and Barry Lynn, the author of Cornered, a book about the return of monopoly to American life. They discuss a wide range of topics; this is Lynn on our favorite bookseller:

Amazon now essentially governs business within the book industry. Amazon has so much power that it virtually gets to tell really big companies like Hachette, the French publisher, what to do. You’re gonna sell this book at this price. You’re gonna sell that book at that price. That means Amazon pretty much has the power to determine how many copies of a book a publisher might sell. That’s not citizens trading with one another in an open market setting those prices, that’s a giant corporation setting those prices. Which means what we are witnessing in the U.S. book industry, I think, is a form of top-down government.

Overall, this is one of he biggest issues in 21st century culture, and neither major political party is doing anything to address it.

Can We Fix Music Streaming?

MOST of the complaints about music streaming so far have been about the way the new system leaves musicians out in the cold. But a new story looks at the way they frustrate listeners. as well. Ted Gioia — jazz pianist, music historian, and avid listener of a wide range of music — recently signed up for the Beats streaming service, recently purchased by Apple, and finds it as bad as the rest. “My Beats experience has been just as frustrating as my previous forays into streaming and downloading,” he says. “If Apple has that kind of money to spend, certainly they can do a better job than this. But 15 years after Napster, we are still in the Dark Ages of online music.”

I’ll leave my readers to check out the list themselves, but here is the first item:

Allow me the option of making a cash payment directly to the recording artist. Many fans feel that streaming services give a raw deal to musicians, and want to make amends for using them. Make it easy for us to do so.

For what it’s worth, I’ve got two streaming stories coming in the next few weeks.

Scott Timberg's Blog

- Scott Timberg's profile

- 7 followers