Scott Timberg's Blog, page 10

April 10, 2017

Jeff Parker and Jazz Guitar

FOR months now, one of the most intriguing instrumentalists in Los Angeles has been unspooling his style for the price of a drink in a small bar in Highland Park. Jeff Parker, longtime guitarist for the Chicago “post-rock” band Tortoise, has lived in Los Angeles for a few years now, and alongside playing with members of Spain and in drummer Matt Mayhall’s trio, Parker has also dropped one of the best recent jazz LPs, The New Breed, which The New York Times picked as one of 2016’s finest, alongside Radiohead’s latest.

I wrote about Parker, who I’ve seen plan in several different settings, for the LA Weekly. The piece is HERE.

Parker will perform with Tortoise in LA on April 17, and will continue his run at ETA the Monday after that. Check him out.

March 30, 2017

Art, Censorship, and the Death of Emmett Till

WELL, it’s really come to this, hasn’t it? Having to defend the very existence of a piece of visual art not against Puritans or Nazis or Southern Fundamentalists or the Taliban but against…. other artists.

The story of how the New York art world has been divided between people who think artist Dana Schutz should be able to paint (and exhibit) a picture of Emmett Till in his coffin, on one hand, and those who don’t just dislike the piece or consider it in poor taste but think it should be removed from the Whitney Biennial and destroyed, locked away, etc, on the other, has already been told. (The argument is that Schutz, a Brooklyn-based painter of about 40 — and a Caucasian — is exploiting a black tragedy.)

This story in Hyperallergic gets into the madness of the whole thing — including the charges led by Hannah Black, a British-born, Berlin-dwelling black artist — better than I can. Of course I get the general argument — that white people have been tourists in and out of black pain for centuries now, often earning money and fame from their exploitation of the blues and various sorts of merchandizing of African-American tragedy.

But to argue that Till, whose mother wanted the world to see his state after he was killed by Mississippi racists, should only be rendered by black artists, and that the offense is so grave that Open Casket should be destroyed, is just nuts. And it’s not the sole incidence of a censorious and intolerant side of the cultural left — a place where I dwell most of the time — which is manna from the heavens for the Fox New crowd.

One angle on this I’d not considered was that this was also a kind of war on abstraction. As Coco Fusco’s Hyperallergic piece argues:

There’s a fundamental misunderstanding at work in damning abstraction by associating it with erasure and irresponsibility. Abstraction, like mimeticism, is an aesthetic language that can be interpreted and used politically in a range of ways. It doesn’t necessarily mean erasure, but it does complicate the connection between perception and intellection—something that deeply thoughtful painters like Gerhard Richter have taken advantage of in order to make us reflect on how photographic images represent history and structure memory. Jacob Lawrence ‘abstracted’ his black figures, not to obscure their humanity but to explore new ways of evoking ethnic identity and communal purpose through color and dynamism.”

Tip of the pen to the Paris Review online for noticing this wrinkle.

And sheesh — how the hell did we get here?

March 21, 2017

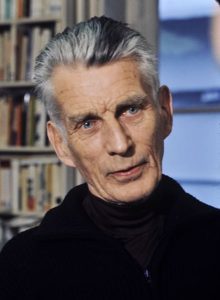

Schubert, Meet Beckett

TONIGHT I am looking forward to going to Disney Hall to see an odd pairing: the songs of Franz Schubert interspersed with the short plays of Samuel Beckett. The recital, put on by the Los Angeles Philharmonic, features several singers and actors including Irish actor Barry McGovern and soprano Julia Bullock. The whole thing springs from the twisted genius Yuval Sharon, best known for the site-specific avant operas “Invisible Cities” and “Hopscotch.”

In any case, here’s how I lead my LA Times piece:

The first was a composer, the second a playwright. One was Austrian, the other an itinerant Paris-dwelling Irishman. And their lives never quite overlapped: The first died a year after Beethoven passed, the second around the time Ice Cube left N.W.A and Madonna divorced Sean Penn. One became famous for sweet, hummable melodies and darkly resonant chamber music, the other for plays defined by their haunting silences.

So Franz Schubert and Samuel Beckett don’t immediately appear to have all that much in common. But “Night and Dreams,” a recital Tuesday night at Walt Disney Concert Hall, seeks to frame them as brothers under the skin — two artists whose work has all kinds of stylistic and emotional affinities.

Here’s the whole story. Hope to see you there.

March 14, 2017

Arts Journalism and the Culture Crash

SOME things have gotten a bit better since I published my book two years ago; some have unraveled more or less on schedule. One thing that does not seem to be improving is the state of cultural journalism: Arts critics (and reporters, like yours truly) continue to be laid off as publications scale back and decide — just as school boards do in lean times — that culture, especially the fine arts, is expendable.

This is not a new story: When I arrived at the Los Angeles Times as an arts reporter (a role a bit different than that of a critic, but governed by the same economics) in 2002, I was one of four generalist arts scribes, alongside a dedicated visual-art reporter, pop music reporter, theater reporter, several movie reporters, numerous culture editors, a standalone book section with its own staff, and whole raft of critics including a fulltime dance writer. (This was, of course, the largest and most ambitious paper west of the Hudson, with Sunday circulation above a million, in a city driven economically by culture of various kinds, so these numbers and this commitment to the arts and entertainment was hardly typical for American dailies.) In any case, my, uh, departure in the wake of the 2008 recession was part of a process that would lead to the paper employing a single arts reporter and slicing and dicing most of the rest of the staff. (Oddly, and thankfully, most of the critics remain.)

In any case, Alex Ross — one of my favorite writers on music — has just dropped a story in the New Yorker on the decimation of music critics. I don’t have that much to add to “The Fate of the Critic in the Clickbait Age” — and I applaud its shoutout to my old friend and colleague, former Angeleno Timothy Mangan — so I’ll just quote from it a bit. Ross begins with the seemingly irrefutable logic — laid down by our corporate overlords and the editors who do their bidding — that the arts in general and criticism in specific draws fewer readers — at least those counted online — as just about everything else, so why keep it going in lean times? (In the world of culture, this means every inch of classical coverage competes against coverage of superhero movies and celebrity divorces.) But, Ross says

Those who subscribe to the print edition are discounted—and they tend to be older people, who are also more likely to follow the performing arts. A colleague wrote to me, “The four thousand people reading your theatre critics might be extremely loyal subscribers who press the paper on others. People in power often speak of ‘engagement’ and ‘valued readers,’ yet they still remain in thrall of the big click numbers—because of advertising, mostly.”

And

Also, even if the data could measure every twitch of every eyeball, should that information control editorial choices? Foreign reporting often draws fewer readers, yet the bigger papers persist in publishing it, because it is felt to be important. One guesses that play-by-play accounts of baseball and football games receive relatively few clicks, yet the sports section is considered sacrosanct.

Thus

The trouble is, once you accept the proposition that popularity corresponds to value, the game is over for the performing arts. There is no longer any justification for giving space to classical music, jazz, dance, or any other artistic activity that fails to ignite mass enthusiasm.

Ross hits it on the head pretty well here. And if you value what arts journalists — reporters, critics, and the editors who advocate for their work — please subscribe to one of the few publications that still employs them.

March 10, 2017

A Musicologist Muses on John Adams

One of the most insightful and eclectic thinkers on music I know is UCLA musicologist Robert Fink, who has written a book on minimalism — Repeating Ourselves — and both teaches music history and run the school’s music-business program.

On the occasion of John Adams’ 70th birthday, and a series of related events in Los Angeles, I corresponded with Fink about the composer’s life and work. Bob put together an event on campus last weekend which included a panel about the composer’s work and performances of some of the chamber music.

I’ll mostly let Bob roll here and stay out of his way.

On the contradiction of the composer laureate of California — a mostly warn and sunny state heavily populated by people of Latino Catholic origins — being a WASP from cloudy New England:

“He is indeed a typical northern New Englander, whose background has some of the hard-scrabble rural poverty and frustrated dreams that provides background for, say, Stephen King’s best gothic stories.

“The move to California puts him in the backwash of the Sixties, right at the moment that Hunter S. Thompson describes in “Fear and Loathing,” when the energy started rolling back.

“So (and I resonate with this personally) he struggled for a while with the end of Cage-style experimentalism in the Bay Area (the musical version of “the Sixties”).”

What part of the California experience inspired the young Adams and his work?

“1. Eco-consciousness. (Lots of imagery of water, light, trees, ocean, etc. Strong connection to the Sierras and the coast.) 2. Alternative spirituality and self-actualization (Jung, Buddhism, etc.). There is a scholar working on Adams and things like Esalen. Many of his pieces in the 1970s and 1980s are overt stories of inner struggle and then transcendence. 3. Berkeley-style political liberalism. (The operas, working with Sellars, etc.)”

Adams’ relationship with the Los Angeles Philharmonic comes after decades in which a lot of us thought of him as a Bay Area artist. Does he seem like a California figure, or a Northern Cal one?

“You’d have to ask whether his connection with the LA Phil in recent years, and his increasing interest in Latin and South Asian culture (El Niño, A Flowering Tree) mean he is moving beyond the very admirable but pretty white confines of Berkeley-style liberalism. I think so, and it’s one of the more interesting things about his recent work. That becomes 4. Multiculturalism.”

Tell us a little about the UCLA/ Schoenberg event, Bob.

“First we heard about Adams’s working methods from Alice Miller Cotter. She showed some of his sketches for major works like Nixon and Klinghoffer. He comes across as a deeply intuitive composer whose work ethic is fierce. He seems to go at even the biggest pieces, like an opera, one bar at a time, feeling his way forward. It’s a very high-risk kind of composing.

“The lesson of the overview is that minimalism was a stepping stone for Adams. It was a way to escape from the double bind of either being a tight-ass serialist or a loopy experimentalist, but in either case not feeling ‘allowed’ to write the kind of music (Beethoven, Sibelius, Hendrix, Coltrane) he liked to listen to.

“But it’s clear that Adams, a real musical prodigy, effortlessly mastered minimalism in one or two tries, and then got bored. (Unlike Reich and Glass, who remain endlessly fascinated by the implications of their own 60s breakthroughs.) We heard Phrygian Gates from 1977-78, and I thought that if I had written that, I would have spent the next 20 years doing over and over again. But Adams only got about five years from the minimalist breakthrough, and then had a complete midlife crisis.

“He then wrote Harmonielehre, with its overt pastiching of late Romanticism; at that point he began to find a more complex harmonic language that worked for him (Cotter again) and that lasted him for about ten years.

“By the 1990s he’s bored again…and so it goes.”

What was the panel — which included you, Nonesuch jefe Robert Hurwitz, and music critic Kyle Gann — like?

“We stayed on the topic of the composer and his ‘work’ (all aspects). I asked him about working process, and we got into some interesting discussion of *how* he works — he begins with pencil in hand at the piano, even though he does not play. He sketches linearly. He uses MIDI and computers to work out arrangements and orchestration (using film scoring software), and then copies out the final ms again by hand. (Very old fashioned.)

“His background as a performer/conductor came up, since we were doing a program largely based in chamber music, which he is not known primarily for. He was a clarinet virtuoso as a child up to college, and conducted a lot at Harvard, so he feels he really understands how instrumentalists feel when they look at a part, whether it respects them and their time/abilities or not. (The tension between this and his need, in the minimal days, to work with masses of sound, was palpable in the concert: you could see performers like Gloria Cheng and the string sextet that played Shaker Loops *working* to produce the masses of sound that Adams wanted. (I talked about this in my preconcert talk.)”

“We talked about commissions and how a composer ‘gets lucky.’ Adams is a hard worker, but he also is aware that he was, sometimes, just in the right place at the right time, and that there have been some key advocates for his music (Edo de Waart, Bob Hurwitz, etc.) without whom all his work might not have mattered. Connection there to his work with LA Phil Green Umbrella – he tries to do this for next gen.”

March 7, 2017

Nixon in China in Los Angeles

IF you live in LA long enough, you might come to think you’ve seen John Adams’ iconic opera not once but several times. There are few more talked-about or written about works from the last four or five decades; maybe “Einstein on the Beach” or “Angels in America.” Adams’ music — his violin concerto, “El Nino,” “Naive and Sentimental Music” — gets performed all the time here, especially by the Los Angeles Philharmonic, for whom Adams became, not long ago, the 21st century version of court composer. And short bits of the opera — “The Chairman Dances,” for example — are performed from time to time or show up on public radio alongside pieces of his like “A Short Ride on a Fast Machine.”

Somehow, though, I had spent 20 years of pretty incessant opera- and concert-going without even seeing “Nixon in China” in its entirety. Sunday’s semi-staged new production at the Disney Hall, put on by the Phil and the Los Angeles Master Chorale, was a revelation for me and, I think, many others.

I knew some of the music, and know Adams’ style well, but the use of old home-movie style footage of Dick and Pat’s Chinese vacation startled me. Shot by old Nixon hands, it provided an oddly intimate and beautifully mundane look at one of the nation’s most complex and enigmatic leaders.

HERE is the LA Times review of the performance. Richard Ginnell, the critic here, got at the visual side of Pulitzer’s production quite nicely, I think. “Ultimately, the most astonishing thing was how well the films were integrated with Alice Goodman’s libretto, Adams’ music and, to my amazement, the live cast members themselves, he wrote. “For Pat Nixon’s tour in Act II, when the libretto mentioned a pig farm, an elephant or Chinese schoolchildren, found film for each appeared on screen, and that made soprano Joélle Harvey’s soliloquies as Pat more heartfelt.”

Here’s hoping we won’t have to wait another 20 years to see this again. And that the Los Angeles Opera steps up and gives us a fully staged production.

Until then, happy 70th to John Adams, California’s unofficial composer laureate.

February 28, 2017

Guest Columnist: A Real-Life Maria

This week I offer our latest column from guest Lawrence Christon, a former Los Angeles Times staff writer on theater and comedy, and a longtime culture freelancer in Southern California. This one needs no further ado.

A GIRL NAMED MARIA

By Lawrence Christon

I’m standing in the deserted home furnishings section of a department

store late at night, shopping for a mattress. It is the dark season,

in more ways than one. The Cheetos-colored Borscht Belt clown with the

funny hair and floppy suit has bullied his way through the long

primary and election run right into The White House, and now, as the

march of the Trumpkins gains volume, the joke is on us.

A young woman in a black business suit approaches.

I know what you may be thinking — a man and a woman alone in a room full

of mattresses — particularly given the conditions for despair that form

the classic background for abandon. But an indiscretion would be

wholly fantastical; the real condition, however, is not: political

free fall. A Democratic party that has abandoned its Rooseveltian

principles. A skewed economy in which the rich get richer and the rest

of us scrap for what’s left on the landfill of diminishing returns. A

culture so rife with capitalist values and attendant

corporate-academic jargon that, as mentioned in a recent issue of the

Atlantic, the ‘60s utopian sentiment of free love has now become, for

eligible women, the search for “an empowered version of uninhibited

sexuality” in a dating scene where “sexual interactions…are explicitly

commercial.” And the question arises, “should marriage be downgraded

to a joint custodial arrangement for raising kids?”

Hannah Arendt wondered aloud if the totalitarian horrors of Stalinism

and Nazism, in an echo of Pound’s line, “helpless against the

systems,” would fundamentally alter human nature in the 20th century.

That alteration was rooted in fear. Now we have one rooted in the

actual invasion of consciousness, by digitized media, by the popular

fusion of politics and entertainment, by every manipulative sound and

image that erupts in ubiquitous screens, big and small, to crowd our

private and communal spaces. The sports screen commandeers our

restaurant conversation. The laugh track attends our pumping gas

outdoors. Continual celebrity updates. News you can use, dumped in

every social media silo we scroll through hourly. Even the chubby

fingers of little kids are swift at working screens. It’s inescapable.

I’m standing in the deserted home furnishings section of a department

store late at night, shopping for a mattress. It is the dark season,

in more ways than one. A young woman in a black business suit

approaches. She’s the salesgirl, or woman, or person, however it’s

phrased in our linguistically fraught time. Her skin is pale, but her

accent suggests Latin America. She’s helpful, patient, knowledgeable about

deals that look good but go bad too soon. She’s professionally

pleasant.

We settle on a high end but not exorbitant purchase. At the

register we discuss delivery options, bonus points, warranty, return

policy, etc. I press a wrong button, and the lengthy process of

printing out a comically yard-long receipt has to be repeated. She

remains patient, laughing gently over how long this wrap-up is taking.

I observe her at greater length: tall and slender, attractive but not

pretty, with an intelligent, somewhat narrow face. Finally the

transaction is done. I look at the printout and see her name: Maria.

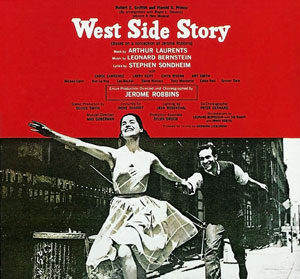

“That’s a nice name,” I say. “Made forever famous in ‘West Side Story.’”

Her face looks blank.

“You’ve never seen ‘West Side Story’?”

“No.”

“Surely you’ve heard the song ‘Maria.’”

“No.”

I try to sing the first few lines, but the tattered result is hopeless.

“Got a cell phone? Dial up YouTube.”

She produces a worn pink-framed mobile device, taps in the trail to

the original 1957 Broadway cast recording. The ardent tenor of Larry

Kert issues thinly from the little phone, but it’s enough:

“…”The most beautiful sounds in the world in a single word…Say it loud

and there’s music playing/ Say it soft and it’s almost like

praying…I’ll never stop loving Maria… “

Department store Maria is hooked. She stares at the little screen,

transfixed, unmoving, her lips parted in wonder.

“…Suddenly that name/ will never be the same/ to me…”

As I observe her, the rush of remembering that production comes back

to me. A New York City councilman named Vito Marcantonio had opened

the floodgates of Puerto Rican immigration to the Big Apple in the

late 1940s. Almost overnight a black-and-white city — a European

city — began brightening with Latino colors, music, cuisine and

exuberant street life. Within a decade, “West Side Story” exploded on

the scene. No one had seen anything like it. It changed New York. It

changed the American theater. The film version won Best Picture. The

only show I could afford that year, I couldn’t get it out of my bones.

I danced crazily down the street like young unschooled Billy Elliott

leaping and spinning his way to the sea in North Durham.

Maria explains to me that her parents moved her back to rural Mexico

when she was four. She’s only been in the U.S. for a few years, hence

her ignorance of American culture and lore.

“I bet you’ll be playing that song after I leave,” I say.

“I will,” she says, in a confessional tone. “Thank you.”

I thought of her on the way home, and many times since. A young woman

who’s discovered magic in an ordinary name, her name, which will never

be ordinary again but instead will echo with the fervor of young love

and the most beautiful sounds in the world.

Innocence is still possible. Joy is still possible. You just never

know when you’ll come across the seemingly unremarkable moment you’ll

wind up cherishing for as long as you live.

February 26, 2017

James Baldwin, Film and the Zeitgeist

SINCE the summer or fall, it’s struck me that a writer long considered the little brother — perhaps even the gay little brother — of black literature’s Big Three had become the essential artist of our time.

Here is my story on him, timed in part to the Oscar-nominated films Moonlight and I Am Not Your Negro, both of which are excellent.

Update: Moonlight, of course, just won the Oscar for best picture. Director Barry Jenkins told me the film was inspired by Giovanni’s Room and The Fire Next Time. Great movie, and as much as I liked Manchester and La La Land, glad to see Moonlight recognized.

February 23, 2017

Music and Design: “Seeing Noise”

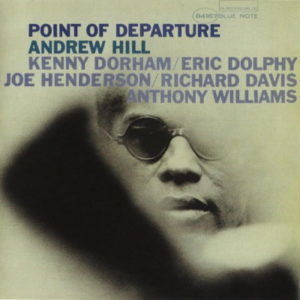

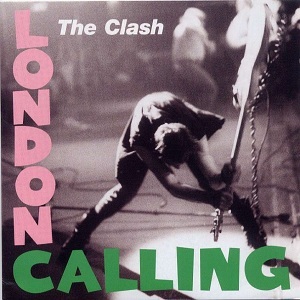

WHY do we talk about “seeing” bands or orchestral groups? How did album jackets and photography of musicians — whether Francis Wolff’s shadowy shots of jazz musicians smoking in the shadows or Astrid Kirchherr’s images of the Beatles in post-industrial cityscapes — become important parts of music’s aura? Is a rock video a betrayal of what music is really about?

I explore some of these question in a recent story for Dot, the magazine of A rt Center College of Design. This story looks at the history of the art/design /music relationship going back to the 1930s with stops along the way to discuss Blue Note, The Beatles, Prince, Factory Records, R.E.M., and more.

rt Center College of Design. This story looks at the history of the art/design /music relationship going back to the 1930s with stops along the way to discuss Blue Note, The Beatles, Prince, Factory Records, R.E.M., and more.

I was surprised to see that ArtCenter faculty and alums had roles in all kinds of major album jackets including “Exile on Main Street,” “Magical Mystery Tour,” early Chris Isaak and Madonna and KD Lang records, Prince’s “Parade,” R.E.M.’s “Out of Time” video, and more.

It’s remains a topic of endless fascination. Here is my brief meditation on it.

January 29, 2017

Snapshots from the Culture Crash: 1

LONGTIME music journalist Steve Mirkin has been, like a lot of us in the creative class, though a series ups and downs since the Internet remade journalism and the recession undercut the middle class. He appears briefly in my book Culture Crash. Here is an update, which begins around January 1.

It was not going to be a happy new year for me. After more than two decades as a music journalist writing for Rolling Stone, Spin, Entertainment Weekly, Variety, Billboard, and others, the freelance assignments were drying up; TV work—writing and researching game and reality shows, which I used to subsidize my writing—was experiencing a drought as well. And I was getting tired of hearing the same comment at the end of job interviews: “You’re highly qualified for the job, but we’re looking for someone who’s more of a digital native.” (Translation: we’re looking for someone younger, but legal won’t let us say that.) It had reached the point that I had decided to do transcriptions, or the literary equivalent of taking in laundry.

That wasn’t going too well, either. It wasn’t the work. As much as I hate doing my own transcriptions, not having to hear my own voice, or cringe at wan attempts at humor and missed opportunities for follow-up questions made the work relatively painless white-collar drudgery. But my first client, a guy I connected with on Craigslist, who offered to pay a premium for a rush job, had gone missing after I sent him the files and my invoice, leaving me without money for rent.

With my savings depleted, I had no choice but to leave the room I was renting in Sherman Oaks. The owners, a performer and employee at an insurance company, needed the income from the room to cover their own mortgage. That night, after dragging my stuff to my brother’s, I felt a twinge in my lower lip, as if I had been given a stealth shot of novacaine. It quickly passed, so I thought nothing of it. Until about two hours later, sitting in a Starbucks trying to figure out where I was going to sleep that night, when my entire left side went dead. My arm felt like a noodle, my hand lacked the dexterity to dial 911, and I couldn’t move my leg. Before I could figure out how to get an ambulance, this passed as well. But unlike my lip, this was scary enough to send me to the emergency room.

The diagnosis at Cedars Sinai was TIA—Transient Ischemic Attack, or a mini-stroke. Serious, to be sure (especially given the lingering weakness in my left arm which, thankfully, has dissipated), but not so serious that, given my bargain-basement insurance, I would be admitted. Instead, I was to be transferred to Los Angeles Community Hospital, in East Los Angeles.

After a 20-minute ambulance ride, I was wheeled into two-story cinderblock structure off Olympic Boulevard, and going by the designs on the tile floor, one that had not been renovated since the 1970s. The halls of LA Community were perfumed by disinfectant, human waste, and mold, with water stains on the ceilings and gaping holes in the bathroom walls. It felt less like a hospital than a warehouse, or a shelter with medical staff.

Not that there was much medical staff to be seen. The unit where I was placed felt severely under-staffed. Over my four days in their care, I saw a doctor once. And after that visit, without any warning, the dosages of my medications—including an antidepressant and a drug that helped control my blood pressure—were reduced. When I asked a nurse why, I was simply told, “doctor’s orders.” Questions about why my personal doctor’s orders were ignored were met with a shrug.

I don’t mean to belittle the nurses; they were, for the most part, caring under impossible demands, responding to a babel of complaints. In my room alone, there was one man who had a stroke, diabetes, and a gangrenous leg. And bedsores. The man in the bed next to mine was so frail he practically melted into his mattress, holding up one friable arm, his fingers as gnarled as a joshua tree, his elbow a fleshy, ringed stump. He was beyond language; every problem—from discomfort, to hunger, to the TV reception—was announced by a wordless complaint: “Gnu-WAAH!”. Attempts to figure out what he needed were met with louder and more emphatic moans. On New Year’s Eve, as I watched Mariah Carey stumble her way through her appearance in Times Square, I thought, at least I’m having a better holiday than her…

Then again, she still has her reality show to fall back on. In that world, the drama of falling on your face in public is good for ratings. As someone who is more comfortable working where reality equals facts and expertise, I’m not sure what the future holds for me.

Scott Timberg's Blog

- Scott Timberg's profile

- 7 followers