Scott Timberg's Blog, page 6

November 8, 2017

Camerata Pacifica and Chamber Music in SoCal

RECENTLY I’ve enjoyed a performance by the chamber group Camerata Pacifica and several conversations with its founder, Adrian Spence. I disagree with the cheeky Ulsterman on some points — I am in some ways an American Anglophile with a European bent, he is a Brit who prefers American ways — but I find him insightful and, with his group, unorthodox in an intriguing way.

Camerata is a group, based in Santa Barbara (sort of), now into its 28th season. After some struggling through the recession, they have bounced back financially, and are playing to larger audiences than before. The group often plays modern or new music — sometimes new commissions — alongside Schubert, Beethoven, or Ravel.

With no further introduction, I’ve included here my recent correspondence with Spence. The group’s next set of concerts runs from Nov. 12 to 17th; schedule here. The November program involves Prokofiev’s First Violin Sonata and Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time. I’ll be there.

There are a lot of classical groups, especially chamber groups, in greater Los Angeles these days. How do you think Camerata Pacifica stands out? Is there something you do better than everyone else?

The LA chamber music scene is flourishing and we’re very excited to be a part of this

dynamic and expanding community, indeed we’re part of a nascent collective with 7 other groups that you’ll hear about soon. I’m not sure I want to get into a better, (or worse), analysis. What’s exciting is the breadth of distinctive offerings in town, and I can tell you that in that environment we are distinctive. Camerata Pacifica is an international group, with musicians are drawn from across the world: Spain, UK, Ireland, Korea, Taiwan and of course the U.S., who are selected not just because of their artistic excellence, but because they subscribe and actively contribute to the Camerata sense of community. That international roster is distinctive, as is our rehearsal schedule: the musicians arrive for a residency in Santa Barbara when they rehearse for between 30 & 40 hours, sometimes more, before performing each program in 4 different cities. All of that is distinctive, as is our programming, which we address in another question.

Some large classical organizations — philharmonics and operas, especially — have had a hard time of it since the Great Recession, with some groups shrinking or laying off players, some shuttering entirely. And there has been talk about the “graying” of the audience for at least a quarter century now. You reject the idea that it’s a t

ough time for classical music, though.

I do. Well, it may be tough for some as we’re going through a significant, but appropriate, ‘market adjustment’ and many won’t survive, especially the large paradigm institutions. The Recession’s not the reason though. While it had a big impact, the issues facing the larger groups long predate that event. Led by chamber ensembles, however, we’re well into a 2nd classical music renaissance. There’s been talk of audience greying for centuries — can’t you writer folks come up with another question? Let me tell you, the last thing I’m worried about is running out of old people — there are new old people every day! The rest of your question demands a more complex answer, which would be book-length. Consider this a start though, classical music burgeons on an emergent middle class: that’s what happened in post-Enlightenment Europe, in the late 19th century U.S. and now in, for instance, China. These new residents of the middle class weren’t all devotees of classical music — for them music was an upwardly mobile thing. In Europe the new class with money and education wanted to emulate the aristocracy; in the U.S. the philharmonics and symphonies weren’t created to satisfy a great love of music, but because civic pride dictated those cities ‘needed’ those components to rival their European counterparts, and, in today’s China the huge emergent middle class has similar aspirations towards, at least perceived, sophistication.

If we allow for that ‘bubble’, it follows there will be a contraction and that’s one of the many reasons we’ve experienced a decline in audience these past decades. Here’s the thing though, and this is a radical notion … at Camerata Pacifica people come only to listen to the music. No airs and graces, no self aggrandizement, certainly there’s no social cachet here — the Camerata audience is there to listen to the music — WOW! This is happening all over, led by chamber music. An audience of 2,000 is becoming much more difficult to find, but 10 audiences of 200? All the time. Look at the programming too … adventurous, interesting, surprising. At the beginning of the 21st century we have the best audiences EVER!

The rule of thumb in most classical groups, as long as I’ve been paying attention, is that audiences are — by and large — not interested in contemporary music or new composers, and that this work should be set off from the mainstream programs with separate all-contemporary concerts or entirely separate series. What has your experience with modern and new pieces been?

Let’s take my previous answer as a starting point: Camerata Pacifica has a loyal and, (key phrase), intellectually curious following. From the beginning, in the early 90s, I’ve programmed music that people don’t know — for a while I had a thing for early 20th century British composers — largely romantically based writing that, while new, wouldn’t be entirely unfamiliar. What happened was our audience became conditioned to show up to concerts with music by composers they didn’t recognize, and to hear music for the first time. This is great! A few times a season I would push the boundaries of comfort, and they would come with me. This was and is so exciting. Another Camerata distinction is our audience is a ‘mainstream’ audience that has journeyed through the repertoire with us. We are not a new music group, nor are we a heritage organization. We are a performing ensemble that explores the range of human musical expression, not bounded by a particular period. Bach had the same hopes and fears as you and I have; that his music is different than Messiaen’s is a result of artistic/technical evolution, not mankind’s emotional development. There’s the basis of exploration.

The idea that audiences aren’t interested in contemporary music is old school thinking, and a principal reason many of the larger groups are going belly up — they’re mired almost exclusively in 18th/19th century repertoire. One of Camerata Pacifica’s most successful programs is our commissioning program, with 17 significant new works premiered to date — all funded by our audience. I don’t see how segregating the audience does anyone any favours, whether it’s new music, old music … isn’t it the range of expression that’s mind-bogglingly wonderful?

Today’s audiences are interested in a dynamic performance experience, unconstrained by style or period. A live performance should be an adventure in listening. For sure you’re not going to love everything you hear, but that too is part of the adventure — developing your own taste, as opposed to being confined by what convention tells you you like.

Your structure is unorthodox: Your concerts take places in Santa Barbara, Ventura, outside Pasadena, and in downtown Los Angeles. The conventional wisdom is that a group that performs in several different cities will engage the loyalty of none of them, and will fail to engage an audience or a donor base. Do you think you’ve beaten this curse?

Dude, you’ve got to get out more ☺ Starbucks does it. MacDonald’s does it: this isn’t a new concept! Camerata Pacifica enjoys great audiences in each city, and they’re all very individual. As with any arts group, our expenses are front loaded … it’s expensive to rehearse and, as I shared earlier, we rehearse a lot. Therefore first concert is very costly, but at that point I have a fully rehearsed band, so the marginal cost of adding performances is relatively small. On the other hand, ticket sales and generous support are increased, in our case, times four. The costs are amortized over four venues, and the income increased over four venues. Camerata Pacifica has a very durable subscription base in each city, with a very high renewal rate. It’s significant too, that while we perform in chamber music appropriate halls, (small), that emphasize the powerful intimacy of this music, cumulatively each program reaches over 1,000 people.

You hail from Belfast, and as an Ulster Scot you are sort of on the edge of Britain, and on the edge of Ireland as well. Does that complex split shape your sense of music, culture, nationality, or anything else?

Yes, a little town outside Belfast called Newtownards. Over there I couldn’t get away with saying I came from Belfast. I haven’t spent my time thinking about the influence of my cultural heritage. It was a working class background and that, for sure, and the inability to take no for an answer helped get this thing started. No is just the first two letters of not yet! That I’m an emigrant might be relevant: those of us who up stakes and cross the world to self-start something? Perhaps there’s a selection process inherent there. Certainly I came to the U.S. and completely bought into the American Dream, that you can achieve anything provided you work hard enough. I don’t believe I could have started something like Camerata Pacifica in the UK or Europe, and I do believe the American system of arts funding, of personal investment, provides a more durable and meaningful model than state funded systems.

Would you like to say something about the next program, which includes a major Messiaen piece, or your concerts coming up this season?

Well, the program that begins on November 12th is profound and intense, with Prokofiev’s F Minor Violin Sonata and Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time — a universally acknowledged masterwork, that was famously composed and premiered in 1941 in a Nazi prisoner of war camp. But all the programs are great —you should come to them all!

That’s only half a joke. We are in the midst of a great time for classical music. This is the golden age. If you must have a diet of only the 18th & 19th century masterworks Camerata Pacifica’s not for you. I can recommend other groups for you to attend, but they’re following a model exemplified by the band playing on the deck of the Titanic. (Ahem, built in Belfast by the way. It was working when it left there!)

This is a great time to be part of an audience of one of the many superb, dynamic groups performing today, be it Camerata Pacifica or another ensemble. You can choose to cling to the past, or you can be part of the dynamic now. If you lean to the latter, my best advice is find a group you trust and subscribe. There’s no point in trying to cherry pick what programs you think you’ll like; there’s no way an audience member can know the range of music an Artistic Director does. Purchase the whole series, listen to everything and enjoy the ride. You’ll love it.

November 6, 2017

Comedian Dick Gregory and The Wallis in Beverly Hills

WHEN I moved back to Los Angeles about a year ago, I was not surprised that the cultural life was rich and wide-ranging. But one spot surprised me: The Wallis Annenberg in Beverly Hills. I had covered some of the early planning for the LA Times, and had liked both architect Zoltan Pali, working to transform a WPA-era post office, and director Lou Moore, who like me is a blue-crab-loving Marylander. But getting things going took longer than expected; Pali and Moore left the project, and I basically forgot about it, to be honest.

So when I started going to The Wallis last season, I was amazed not just at the building and the space — a lovely courtyard, complete with sculptures and landscaping, much of the original 1933 building, inside and out, retained — but the programming.

Somehow, an arts center in Beverly Hills was bringing in not the Broadway road show and dinner-theater offerings I’d expected but finding programming that sat pleasingly between the mainstream and what we used to call the cutting edge. Paul Crewes, who had headed Britain’s Kneehigh Theatre, arrived last year, and brought in both a radical kid’s play by his old group, an energetically eccentric take on Shakespeare, a Brooklyn Rider concert that includes a Philip Glass quartet, and a four-handed reading of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring by two of my favorite pianists, Marc-Andre Hamelin and Leif-Ove Andsnes, that made me feel like I was hearing the piece for the first time.

Over the weekend I went to see “Turn Me Loose,” a (mostly) one-man show on the life and times of Dick Gregory, with actor Joe Morton as the great civil-rights-era comedian. I am not going to be able to do justice to the show, which began with his reflections on his youth in St. Louis, and moves through a Gregory monologue from the early ’60s, his appearances on television and at the Berkeley’s hungry i, through a farewell speech around the time of his death, in August of this year.

Gregory is best described as a comedian, but his engagement with politics, especially racial politics, was not always funny. Like a lot of African-American artists, he struggled with larger questions of how “entertaining” a black audience should be with a largely white audience.

There were some comments about the strange state of contemporary American politics and race relations, but it never seemed forced. In fact, Gregory’s rage seems well-suited to the age we’re in.

Unlike the other shows I’ve seen at the Wallis, this was in the smaller theater, a black boy tricked up with tables to feel like a jazz club. This was an intimate and electric way to relive those years, and Morton and his offstage team took full advantage of the space.

“Turn Me Loose,” which was held over for an extra few weeks from its original two-week run, is a knockout. It runs through November 19; I’m keeping my eye on the rest of The Wallis’s schedule as well.

November 3, 2017

Unions, Journalism, and the Creative Class

IF we needed another reason to disdain the billionaires who increasingly dominate our political and cultural life: The Chicago Cubs owner Joe Ricketts shut down several news sites, including Gothamist and LAist because the New York staff tried to unionize.

This is from a new New York Times op-ed by Hamilton Nolan, “A Billionaire Destroyed His Newsroom Out of Spite:”

It is worth being clear about exactly what happened here, so that no one gets too smug. DNAinfo was never profitable, but Mr. Ricketts was happy to invest in it for eight years, praising its work all along. Gothamist, on the other hand, was profitable, and a fairly recent addition to the company. One week after the New York team unionized, Mr. Ricketts shut it all down. He did not try to sell the company to someone else. Instead of bargaining with 27 unionized employees in New York City, he chose to lay off 115 people across America. And, as a final thumb in the eye, he initially pulled the entire site’s archives down (they are now back up), so his newly unemployed workers lost access to their published work. Then, presumably, he went to bed in his $29 million apartment.

They’ve been in retreat in the US for most of my life, but trade unions remain crucial and are important for the creative class, including journalists, just as they have traditionally been for the industrial working class. HERE is my piece for Salon about the pros and cons of unionization.

Oddly, Salon was caught in an ugly union fight while I was there. When I left, more than a year since it began, the instability of the place — constant turnover at both the staff and management level — made it impossible to settle on an agreement.

In any case, this billionaire — who put several people I know out of work — earns the selfish scum award this week.

October 29, 2017

2017 PEN USA Literary Awards

TYPICALLY, the PEN awards, held at a fancy hotel in Beverly Hills, ends up as one of the best parties of the year for literary and journalistic folk. The group and its events, of course, also have a bloody point to them: PEN is, mostly, a free-speech group, and its annual banquet is an attempt to honor artistry and freedom of expression and to raise money so they can do it again next year. (PEN USA was once known as PEN West, to distinguish it from the New York-based PEN America; the current LA-based group has ties to Hollywood but is hardly just an association for screenwriters.)

In the spring of 2015, the East Coast PEN was torn with internal tensions over an award to Parisian magazine Charlie Hedbo: Even here in Los Angeles, last fall, it was hard not to hear echoing cries and denunciations that split what we could describe as free-speech liberals (Salman Rushdie was the fiercest of the group) vs. a small, outspoken group incensed by the magazine’s supposed bigotry. (This was either an updating of old quarrels on the Left or a dry-run for he larger tensions were are seeing today.)

In any case, this year’s gathering, Friday night at the Beverly Wilshire, was not only free from obvious partisan rifts, but took on a fierce sense of purpose I don’t recall before.

With a clean-shaven Nick Offerman, the burly Parks & Recreation star, emceeing, and major awards going to Margaret Atwood (author of Theocrat dystopia The Handmaid’s Tale) and the team of New York Times reporters who broke the long-rumored Harvey Weinstein sexual-harassment story, this was a rare chance to feel good about the bad stuff swirling through American culture right now.

There may be awful things afoot, we thought at as we sipped Chardonnay and ate our roast chicken, but at least somebody is paying attention. (Whether that is enough is a question I cannot answer.)

So while PEN USA often gives its major awards to people overseas, typically in autocratic states — African writers who risk exile or death, journalists who have survived imprisonment in the Middle East — this year much of the emphasis was on brave folks here in Donald Trump’s US of A. (These included, as well, Janet Mock

, the mixed-race trans-woman who is the author of bestselling memoir Redefining Realness.)

This event, like the others I’ve attended, was smooth and well-executed, with winners’ speeches never reaching Oscars-level solipsism. Offerman’s delivery is famously ironic. But he was a solidly authoritative host here, offering both comic relief and good-natured expression of purpose, as when he described “the freedom or people to express themselves — it’s not something we should ever take for granted.”

(When I interviewed Offerman about his then-new podcast a few days after last year’s presidential election, he expressed nothing but frustration over our new president and his intolerant policies.)

Chelsea Handler was a bit more pungent. “Good evening, fake news, mainstream media, you suckas! I’m Kellyanne Conway!” (She went on to speak about sexual bullying by Bill O’Reilly and Weinstein.)

The Freedom To Write Award went to the New York Times’ Emily Steel, Michael S. Schmidt, Katie Benner, Jodi Kantor, and Megan Twohey, three of whom attended. (Interesting to note: The Times’ top editor Dean Baquet once helmed the Los Angeles Times. The New Times team emphasized how hard Baquet pushed for difficult investigative reporting on the story, despite the fact that numerous news orgs have struggled to nail it down for years. In other words, if the mediocre minds of the Tribune Corp., has not so badly mis-handled the LA paper during Baquet’s time there, provoking his resignation, this scoop likely could have come from Hollywood’s hometown paper. Baquet, for what it’s worth, hired me here in LA when he was managing editor.)

Much of the buzz at the event was around the appearance of Atwood for her lifetime achievement award. (The television adaptation of The Handmaid’s Tale has become a rallying point for those disturbed by the sexual politics emanating out of the White House these days.)

Atwood’s address was brief but effective: She talked about her involvement with the Canadian PEN going back to the ’80s, when the group was fragmenting into English and Francophone arms. She never though, she said, that the group would have to work so hard to defend freedom of speech in nations like the US and Canada: These days, though, it can be hard to tell whether what we see online comes from a professional troll, the agent of a foreign government, or simply a ‘bot.

She’s also disturbed by the current censorious impulse of the Left. “Both sides attempt to shut down organizations like PEN, so old-fashioned in their rationality.”

Because the bash is held in Beverly Hills, it often attracts strange characters, like the older man at my table who asked everyone who sat down if they knew any movie producers who could get his movie made. These folks are easy to avoid though.

I try not to use words like “inspiring” when I can help it, but this year’s PEN banquet seemed to be very much on the right track.

October 27, 2017

A Turning of The Tide?

SINCE I turned my book Culture Crash in four years ago, a few things I described have proven me a bit pessimistic. (Visual art may be healthier than I predicted, and music steaming has become a bit more artist-friendly.) In some cases, though, even this grim tome of mine was a bit rose-colored. Even though I wrote — against the advice of my editor — a cautionary chapter on the Internet’s transformation of journalism, things have turned out far worse than I expected.

So even while I lamented what technological and other shifts had done to journalists themselves, and discussed the centrality of print journalism in the ecology of the arts, and even cautioned that journalism was a cornerstone of democracy, I had no idea we’d have a presidential election jacked by a foreign power and, as seems likely, former members of the KGB.

A growing body of criticism of the Internet and Silicon Valley has taken shape since Culture Crash came out, with Franklin Foer’s World Without Mind and Jon Taplin’s Move Fast and Break Things two recent and exemplary examples.

My sense is that the mainstream press and a wide range of North Americans are now aware of the dangers that an unregulated Web opens our democracy up to. As a globe-trotting music-journalist friend, who speaks to a wide range of people, told me the other day, there seems to be a turning of the tide.

A recent New York Times piece, “Silicon Valley is Not Your Friend,” got at this a bit. As Noam Cohen wrote:

Facebook has endured a drip, drip of revelations concerning Russian operatives who used its platform to influence the 2016 presidential election by stirring up racist anger. Google had a similar role in carrying targeted, inflammatory messages during the election, and this summer, it appeared to play the heavy when an important liberal think tank, New America, cut ties with a prominent scholar who is critical of the power of digital monopolies. Some within the organization questioned whether he was dismissed to appease Google and its executive chairman, Eric Schmidt, both longstanding donors, though New America’s executive president and a Google representative denied a connection.

Meanwhile, Amazon, with its purchase of the Whole Foods supermarket chain and the construction of brick-and-mortar stores, pursues the breathtakingly lucrative strategy of parlaying a monopoly position online into an offline one, too.

The twisting of news articles on Facebook is the subject of this New York Times piece on faulty fact-checking.

And in today’s Times, there’s a story, “Russia Fanned Flames With Twitter, Which Faces a Blowback“:

SAN FRANCISCO — Fires need fuel. In this era of political rage, a Twitter account that called itself the unofficial voice of Tennessee Republicans provided buckets of gasoline.

Its pre-election tweets were a bottomless well of inflammatory misinformation: “Obama wants our children to be converted to Islam! Hillary will continue his mission.” A mysterious explosion in Washington, it said, had killed one of Mrs. Clinton’s aides, raising her “body count” to six. Another proclaimed, “Obama is the founder of ISIS.”

The account, @TEN_GOP, eventually reached more than 130,000 followers — 10 times that of the official state Republican Party’s Twitter handle. It was one of the most popular political voices in Tennessee. But its lies, distortions and endorsements came from the other side of the world.

Overall, the press and both major political parties have been a bit soft on our technological overlords; I’ll be curious to see if this wave crests and leads to real regulation.

October 25, 2017

The Legacy of ’90s Indie Rock

IF you live long enough and write for a living, there’s a pretty good chance you will end up “curating” — to use the current term – your own youth. That’s what happened to me when I tried recently to make sense of where “alternative” or indie rock was 20 years ago today.

I see it as a cultural high point, and its making — as well as unmaking — remain fascinating to me. Still, the process of historicizing the music of my 20s (esp for younger readers) was strange indeed.

Our sense of popular culture, especially the bits that unspool while we are young and impressionable, is always bound up in part with our personal stories. In my case, I graduated college a few months before Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit” exploded all over the radio, inaugurating the indie heyday. By 1997, I was nearing the end of my 20s, and ended up moving from New England to California.

The albums that came out that year — Built to Spill’s Perfect From Now On, Sleater-Kinney’s Dig Me Out, Elliott Smith’s Either/ Or, and those are just a few from the Pacific Northwest — showed the indie tradition maturing in a pitched, exciting way. Belle and Sebastian has just released its US debut, and Pavement was still at its height. For the first time, music of my generation, and not late-Boomer bands, dominated my listening. And then it all started to fall apart.

Here is my new piece in Vox.

And here is a song from one of my favorite albums of 1997.

October 24, 2017

Classical Music and The Echo Society

Photos Michelle Shiers

SOMETIMES — certainly not always — it makes sense to take a chance and see something you have very little sense of. Because I had the night free and knew/ liked some of the people involved, I went Sunday night to the final concert of a weekend-long chamber-music festival (or something) in Los Angeles’s Silverlake Hills. I figured there’d be a cocktail party for a few dozen of us and perhaps a quartet playing something modern and fresh.

The event turned out to be far larger, wilder and more unorthodox. A hilltop mansion, like something out of a ’20s film, spilled out with more than 200 people, taking in the dry-autumn views by the pool, wandering around the huge foyer, and checking out the sculptures and paintings.

Once the show started, musicians started playing in six or seven rooms and this became what a musician friend termed a “wanderfest,” with all of us drifting from wing to wing to see, oh, a chamber group, a musician making music with a series of empty glasses on a bar, or a minimalist set of beats. Here is the program for whole thing.

It was all too dreamlike and atmospheric to do justice to in description. (I will acknowledge that due to the large crowd and sometimes small rooms, I got to see a lo

t of it from beyond a doorway, without perfect sight lines or ideal acoustics; this would not have been everybody’s idea of a good time.)

But some quick observations:

++ For decades, one of the biggest rifts in Los Angeles has been between the “arts” folks and people who work in “The Industry,” which means entertainment. There’s a longstanding and tribal opposition. Part of what was interesting here is that many (most?) of the composers involved worked scoring films, but are interested in doing more intimate/ classical/ whatever work as well. These may have been conservatory kids who ended up writing for film; in any case the crossover felt rich and unforced.

++ Years ago, then-head of UCLA Live, the Englishman David Sefton, and I used to routinely lament the fact that new classical music did not have the same kind of young/ hip audience that contemporary art did. (The audience for new compositions was significantly older and often socially awkward.) This showed a crowd, here in LA, coming out for something that wsa at least 3/4 classical. And while it was party a social thing, this makes it no different than the original chamber music that evolved in the 18th and 19th centuries.

++ One highlight for me was Dan Romer — a film composer known for Beasts of the Southern Wild and the Idris Elba-starring Beats of No Nation. He sang in front what I think was a violin, cello, and double bass, also playing a ukelele and accordion as he belted out a surreal tale of an unborn son. The whole piece, presented with an eerie kind of commitment, reminded me of Sufjan Stevens and the last few Decemberists records.

++ My other favorite was the group led by Amritha Vaz; this was a traditional Indian music — complete with tabla drum and what I take to be Hindi singing — taken, at times, in a Bollywood direction. Is the Theremin typically part of Indian films? In any case, this combination worked and had a spellbinding effect.

++ The consensus from friends was that Sunday’s highlight was Reggie Watts, a German-born musician/ comedian/ bandleader/ “disinformationist” who is hard to sum up. In any case, his ability to lead the band on James Corden’s TV show and to offer looped beats the other night gives me meaning to the overworked term “eclectic.”

In any case, very much looking forward to what this group, which has been around for several years but never put on an event as large and ambitious as this one, comes up with next.

October 18, 2017

Lauren Greenfield and “Generation Wealth”

GENERALLY, I think the art world has missed the opportunity to address the Great Recession and the amping up of income inequality and the one percent that followed. But some visual artists have made strong and eloquent statements, and one of them is longtime Los Angeles photographer Lauren Greenfield. I caught her Generation Wealth late in its hometown run at the Annenberg Space for Photography, so did not write more than an encouraging tweet or two.

But the show, apparently, has landed in New York, on The Bowery, and I’m glad a new round of viewers will have a chance to check it out.

Here’s a bit from the New York Times on the show and “the Meaning on Money”:

Few photographers have reckoned with money as consistently as Lauren Greenfield, a photojournalist and director of documentaries like the housing-bubble fable “The Queen of Versailles.” Her subjects are socialites and cosmetic surgery patients, fashion-obsessed preteens and bankrupted property flippers, child beauty queens and aging strippers. And she, too, has a gift for winning her subjects’ trust, whether at a Beverly Hills high school or on a Beijing polo field.

Yet where older photographers like Ms. Barney depict wealth with a certain chill, Ms. Greenfield prefers heat — bold color and strong moral objection. Her exhibition “Generation Wealth,” on view at the International Center of Photography on the Bowery, is a bitter, reproving tour of her 25 years exploring American and global materialism, and it’s accompanied by a glistening cinder block of a publication, filled with over 500 pages of diamonds, collagen and Birkin bags.

The Times review is mixed, and questions whether Greenfield is projecting too much distance from her subjects and her own generation (which is also mine.) A worthwhile question for any photo-documentary. But this is a titan of a show.

October 16, 2017

Richard Wilbur, American Poet, 1921-2017

JUST a quick post to note the death of the great poet and translator Richard Wilbur. Until two days ago, when he passed away at 96, I would have called him America’s finest living poet.

Like most kids, I studied some poetry in high school and college — Eliot, Auden, Yeats, Langston Hughes, Bishop, etc. I even, in my very early 20s, fell hard for a few poets in translation (Rilke and Neruda, I think.) But it was not until a few years later that I came to see that there had been poetry, in English, in my lifetime, that was stirring, witty, accessible, and part of the tradition or traditions I was interested in.

And one of the key figures in the survival of American poetry into the end of the century was Richard Wilbur. Because he had taught at my alma mater for many years, albeit before I arrived, I’d known his name for a long time; he’d also been US Poet Laureate and won two Pulitzers. (A professor of mine from Wesleyan mentions that when he met the unfailingly gracious poet, in the 1970s, Wilbur already knew his verse, which was controlled and balanced and a bit formal, was already unfashionable among the late Confessionals, Boomer hippies and neo-Beats then dominating the poetry world, but didn’t gripe about it.)

But it was really only later, when I was out of school and looking for work that interested and excited me, than I got into his verse and that of a few of his contemporaries. When poet James Merrill — a longtime friend — died in the winter of 1995, I was the arts reporter at the local paper in shoreline Connecticut, and called Wilbur to discuss the work of his fellow Amherst graduate. Wilbur was helpful and eloquent, as well as shaken up by the sudden departure of a peer; I wish I still had the notes from that conversation.

When I wrote the book upon which this blog is based, Culture Crash, I wrote an extensive section on 19th century bohemianism — the clash of artists and art-making with the marketplace, on the final retreat of the aristocracy. Much of this was edited out of the finished book, but the poem that kept going through my mind was Baudelaire’s Albatross, and Wilbur’s wonderful translation of it. As a lover of French poetry who does not have any French, I have read A LOT of Baudelaire, and Wilbur’s Albatross, Correspondences (“Nature is a temple, whose living colonnades…”), and a few others are the best I know by an American. I found Wilbur’s mailing address and composed in my mind a letter to ask if I could reprint the poem in my book; but this was a letter never sent.

I’d suggest that if there is an established American poet who was a better translator of European poetry, I don’t know who it’d be.

One of the best books ever written on American poetry, Peter Davison’s The Fading Smile, about the post-Frost literary scene in ’50s Boston, has a very fine chapter on Wilbur. As a veteran of World War II’s European theater, who wrote to reinforce and celebrate a civilization he saw nearly destroyed by the Nazis, he was a bit unfashionable even then.

The Los Angeles poet Leslie Monsour posted the last stanza of the beautiful early Wilbur poem Juggler, and I will let this stand as nearly the last word for now. I won’t try to explain the thing but will just say it makes more sense in context:

If the juggler is tired now, if the broom stands

In the dust again, if the table starts to drop

Through the daily dark again, and though the plate

Lies flat on the table top,

For him we batter our hands

Who has won for once over the world’s weight.

Hoping to get some time later to write more on this titan of the world of letters.

October 9, 2017

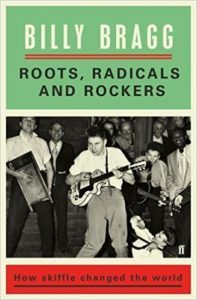

Billy Bragg and the Rebel Power of Skiffle

Back in the mid-’80s, I was in a Calculus class when a friend I knew mostly from our shared love of punk rock handed me a hand-labelled cassette of a musician I’d never heard. When I got home, I played this selection of songs by Billy Bragg — A New England, Greetings to the New Brunette, It Says Here — which reminded me of the Clash in their political force and Dylan a but in their format — just a mouthy singer, alone with his guitar — but defined its own ground.

Seeing Bragg play at the “old” 930 Club in Washington, DC became one of my first regular musical pilgrimages, and was, along with annual trips to see a New Jersey band called The Feelies, of the most imprinting events of my teenage years.

Flash back several decades, to the years after World War II in Britain. A nation still reeling from the war, where many consumer goods were still rationed, discovers America through the music of Leadbelly and New Orleans jazz. The result is called skiffle, and it will hit a brief and stylistically limited peak but serve as a foundation for the Stones, the Beatles, BritFolk and psych musician like Bert Jansch, Zeppelin, and David Bowie.

Tonight, 10 Oct, Bragg speaks on his excellent new book Roots, Radicals and Rockers: How Skiffle Changed the World, at the Grammy Museum. (Tomorrow,11 Oct, he’ll perform at the legendary Troubadour with, presumably, some skiffle-inspired between-song banter.)

This is more than just a fan book written by a musician, and more than just a book about music: It’s a full social history.

My conversation with Bragg is here, in the Los Angeles Review of Books.

Scott Timberg's Blog

- Scott Timberg's profile

- 7 followers