Scott Timberg's Blog, page 4

June 1, 2018

The Bookers: Performing Arts in Los Angeles

It was on returning back to town in 2016, after a year away, that I was startled to see how much the performing arts scene had changed since I originally landed here in the late ‘90s. Some things about L.A. were worse, but this was more, better, more wide-ranging.

Instead of a simple cultural geography that mostly involved downtown L.A., the city had de-centered: Now I could see a jazz group in the Valley, Shakespeare in Santa Monica, a one-man-show on Dick Gregory in Beverly Hills. (I’d lived in that stories burg in my first few years on the West Coast, and feared the long-rumored arts hall would be devoted to some combination of conspicuous consumption and show-biz nostalgia. But the offerings at the Wallis Annenberg are among the most adventurous in town.)

I’ve learned as much about human nature, individual psychology, and the big questions of life and death from performances as I have from novels, films or visual art, so the expansion of performance here was a big deal. And while show folk, like all Angelenos, like to complain about the traffic and the gaps in public transportation, I realized that the frozen freeways—which had gotten worse while I’d been away—were partly responsible for the new offerings.

My attempt to decipher the new geography, and larger reality, of the performing arts in Los Angeles led to my latest feature, The Bookers, a piece in Los Angeles magazine concentrating on the men and women who bring classical music, opera, theater, dance, and multi-genre work to town. No single piece could get at all of the performing arts in greater LA, so I’ve emphasized recent changes and venues that break out of downtown’s historic near-monopoly.

The story is not yet online, but I’ll post it when it is. But the June issue is on stands now.

Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts, Beverly Hills

May 26, 2018

The Return of the Posies (Guest Columnist)

LAST night I caught the Seattle-area band the Posies at the Bootleg Theater, which has gradually become one of my favorite places to see a show in Los Angeles. Out with me was a music writer whose work I’ve admired for 20 years (okay, she’s now my wife), who was an ardent fan of the band back when they and a handful of other indie rockers were reviving power pop in the wake of grunge. (One of the group’s singers, Ken Stringfellow, has played with Big Star’s Alex Chilton as well as R.E.M. — whose bassist, Mike Mills, was at the show last night.) But the days when you’d hear the group at bars and clubs and in the background of socializing — as they seemed to be in the early ’90s — are gone; a lot of music fans surely don’t know they’re still, at least some of the time, very much together.

In any case, I’ve been musing on a piece about how riveting power pop can be live: In the last few weeks I’ve seen Sloan and Nada Surf, with Teenage Fanclub and the New Pornographers a bit further back. (The pre-show music playing in the club offered a kind of homage, with songs by Big Star, Cheap Trick and the Knack.) But that will have to wait, because this review is by the great Sara Scribner. Here she is.

The Return of the Posies

By Sara Scribner

Photo by Cary Baker

A few songs into the Posies show at the Bootleg Theater, Jon Auer paused and surveyed the crowd, noting that he was slightly chagrined about looking a bit timeworn and threadbare. “I just realized,” he said with a smile, “you’re all older too.” That may have been true, but no one at show marking the band’s 30th anniversary had been feeling it.

The band had the room fully lit — spun out on singer and guitarist Ken Stringfellow’s taut power-chords, Auer’s still-dreamy vocals, and the pair’s electric chemistry. I’ve been to a few 80s and 90s reunion shows. Sometimes they’re just depressing, reminding you all of all the time that has passed. This one, like Dinosaur Jr.’s high voltage show in 2006, was a different beast: it served to brush away the dirt on the lens, redefining and focusing what had made the band great, and what keeps it that way today.

There are few bands who perfected power pop as the Posies did. Not all of their songs hit, but when they did, the effect is about as close to nirvana as it gets. They didn’t waste any time in reminding the crowd of this, just getting it out of the way by opening with “Dream All Day.” A few songs later came “Golden Blunders,” one of their best-known songs, a shimmering, dreamy wonder full of juicy hope and apocalyptic regret, as good as any song ever inspired by Big Star.

Auer’s low-key energy belied his still-serious gifts as a singer — he’s all grown-up now, and there’s not much of the grunge-era mane that he flung around in his Geffen heyday. Stringfellow, however, shook off the years, locking in with Auer at key moments, rocketing across the stage, spitting (as is his wont) when the urge grabbed him. Together, they almost resembled a father-and-son team, but fully in sync and with each others’ firm respect and approval all the way.

The team spirit was surely amped up by enlisting all of the original members from their early-‘90s, Frosting on the Beater lineup, including drummer Mike Musburger and bass player Dave Fox. There seemed to be some trepidation about playing Los Angeles — angst also delivered by the group’s killer opener, Terra Lightfoot — and it wasn’t hard to imagine that Los Angeles had a fair mix of good and bad memories for Stringfellow and Auer. That didn’t last for long, as the group churned out a super-tight set full of sugar and adrenaline, lit every now and then with a little rocket fuel.

Fans can keep them as their secret, but there has always been a big question mark attached to the band — what happened? Why didn’t they blow up as they should have? How could Geffen have screwed up this gift, a group who wrote songs this good? At this show, all of those questions, all of the hard years, including deaths of band members, fell away. The Posies played their hearts out, and they won ours all over again.

May 8, 2018

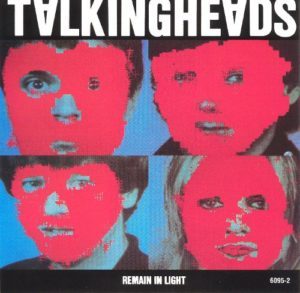

Angelique Kidjo Plays Remain in Light

THE other night I caught a stunningly good show by the West African musician Angelique Kidjo — a reimagining of Talking Heads’ classic 1980 album Remain in Light, itself inspired by West African rhythms and themes.

I was having so much fun I failed to take notes, but sometimes guest columnist Steven Mirkin, a longtime music journalist, was paying more attention. Here is his review of Saturday night’s show.

By Steven Mirkin

Remain in Light has never been my go-to Talking Heads album. I prefer More Songs About Buildings and Food or their debut,‘77, albums that drew from their CBGB repertoire, and sound more like the band I fell in love with in the mid-‘70s: angsty, skeletal funk and R&B in the service of songs that approached quotidian subjects from odd angles. They were smart, approachable, and funny.

But Talking Heads were never a band to sit still; when they reached the limitations of their original minimalist art-rock, they moved on, adding former Modern Lover Jerry Harrison less than two years after the 1975 debut, expanding the band again in 1980 to perform the African-influenced music heard on Remain in Light and Speaking in Tongues.

African music had been circulating through the downtown underground: the Minimalist work of Steve Reich, the albums compiled by John Storm Roberts for his Original Music label, and early tours of Fela Kuti and King Sunny Ade, who stunned audiences with their energy, invention, passion, and the sheer length of their shows, which could extend past three hours. Talking Heads were among the first rock bands to fully embrace it.

Listening to Remain in Light today, you can still hear the excitement of the band figuring out a new way to make music. Instead of writing traditional songs, the band built the songs up from the grooves. Most of them are repeated single chord vamps with Byrne’s twitchy, strangled vocals floating on top, addingmelodies. It’s a nervous, worried album for nervous, worried times, and arguably the best melding of African and rock sounds.

It’s such a complete meld, that when Angelique Kidjo, the Benin-born singer-songwriter that NPR called “Africa’s greatest living diva,” first heard the album in 1983, she was convinced they were an African band, and didn’t know their American roots until she saw them in concert. She was so impressed, that 35 years later, she covered the album in its entirety for her new album, also called Remain in Light, due out June 8th on Kravenworks Records. It’s also the centerpiece of her current tour, which played the Theater at the Ace Hotel Saturday night, the closing concert of CAP UCLA’s season.

Hearing Kidjo and her bi-racial, intercontinental band play those songs was a pleasantly jarring experience, like reading a book originally written in English, translated to a foreign language, then re-translated back into English; it might not be exact, but new shadings and understandings arise.

Hearing Kidjo and her bi-racial, intercontinental band play those songs was a pleasantly jarring experience, like reading a book originally written in English, translated to a foreign language, then re-translated back into English; it might not be exact, but new shadings and understandings arise.

Kidjo’s versions honor the originals, but find new ways into them. A lyric such as “the world moves on a woman’s hips” (from “The Great Curve”) becomes, in Kidjo’s hands, a call for love and environmental action. Dominic James’ guitar, whose circular, repeated lines had the darting, mercurial quality of Highlife music, and the stunning drum and percussion tandem of names Edgardo Serka and Magatte Sow, who, even when the music slackened (especially during “The Overload,” the plodding song that ends the album on a note closer to Eno than Entebbe), locked onto the beats that power the music with an elegant ferocity. “Houses in Motion,” featuring guest Jerry Harrison and the Antibalas horns, turned even closer toward James Brown and the simmering stew of P-Funk.

Kidjo didn’t the treat the album as a sacred text; instead of playing the album start to finish, followed by a set of her own material, her set interweaved all eight of the album songs with her own. It was a smart move, emphasizing where spaces where the music overlaps. The Heads’ “The Great Curve” rubbed shoulders with Kidjo’s cover of Miriam Makeba’s “Pati Pati,” and the ebullient “Afrika”—where Kidjo led the band into the aisles and danced with the audience—sounded right at home between to “Once In A Lifetime” and “Tumba,” a showcase for the percussionist as the crowd , invited on-stage to dance shook and stomped to his improvisations.

For ninety minutes, the world outside, with a president who revels in stoking nationalist fears, fell to the wayside, replaced by music that ignored racial, political, or national differences to focus on what connects us; the result was a joyous, enthralling night of music.

April 30, 2018

The Literary Courtney Barnett

I CAN remember only a few times I’ve heard a song and immediately known I was hearing a major talent, someone I’d be paying attention to for years to come. The Smiths, Liz Phair, Pavement, Thelonious Monk, and Glenn Gould have all struck me that way. Time will tell if she really belongs in their company, but the Aussie singer-songwriter knocked me out with her song “Avant Gardener.” I could tell that behind a slack delivery and seemingly disengaged guitar style there was something serious.

Further exposure, and last year’s album with Kurt Vile, Lotta See Lice, has only reinforced my first impression. It doesn’t hurt that despite her tender years she’s mining the ’90s indie tradition of distorted guitars like someone born two decades earlier.

Barnett, who has a very fine new LP and a May 10 show at LA’s Pico Union Project, spoke to me about her childhood and adult reading for my All the Poets column. Turns out she started as a bit of a library rat.

Barnett is a famously guarded interview, but I found her both open and enthusiastic. Our full conversation is here.

April 16, 2018

“West Side Story,” and Leonard Bernstein at 100

IT’S hard to think of a figure in American cultural history more complex and protean than Leonard Bernstein. For my generation, he was already in eclipse when we came of age in the ’70s and ’80s. But he was such a titan that many of us — and those older and younger — are looking forward to the performances of his work and the upcoming exhibit at the Skirball Cultural Center here in Los Angeles. (I have a modest piece about the show and Bernstein’s legacy in Los Angeles magazine, here.)

In any case, CultureCrash’s guest columnist remembers the Broadway roots of the film West Side Story, and has this to say about the forces that made it all possible.

By Lawrence Christon

This centennial year of all things Lenny rightfully celebrates the career of composer-symphonic conductor-pianist-TV educator-author-activist and international celebrity (gasp) Leonard Bernstein in numerous orchestral settings and FM classical music airplay. But Bernstein was a born showman too, and it’s a shame that we’re not hearing more of the works, however sparse his output, that put him in the top rank of Broadway composers.

Broadway was the itch he loved to scratch. On the Town (1944) is full of the madcap zest of three young swabbies out to devour every ounce of life they can on 24-hour liberty in New York City before they have to return to their ship and a world war whose outcome is far from assured. The Bernstein score, with Comden & Green lyrics and libretto, contains songs that went on to lives of their own, such as “New York, New York,” “Lucky To Be Me,” and “Lonely Town”—loneliness an emotion you’d never think the lavishly extroverted Bernstein experienced.

He traveled internationally, conducting Mozart, Beethoven, Mahler, Schubert and other giants of the Western canon. But New York was his town. He found all the violent, corrupt, stark, romantic, spiky, yearning and anxious impulses of the post-war world in its streets and alleys (his powerful score for the 1955 film, On the Waterfront, is fearsome and riveting). He was one of the figures who made New York the cultural capital of the West through the ‘50s.

West Side Story represents one of the decade’s culminating works. A lot of people consider it the only American musical besides Porgy and Bess to qualify as an opera (I would add Stephen Sondeim’s Sweeney Todd to that category). There’s a good case for it, especially if you consider how far beyond the standard boy-meets-girl (or more recently, boy-meets-boy) Broadway terrain the show travels. As a rule, musicals tend to be about ironing out misunderstandings. They don’t usually erupt in violence and bloodshed. They don’t show people stuck in intractable hatred and dead-end lives. They don’t end in a funeral march. And they are rarely as heart-wrenchingly beautiful.

West Side Story opened at the Winter Garden Theatre on September 26, 1957, and was a smashing success that seemed to tap flashpoint tensions between Puerto Ricans and Anglos that had been simmering for years. It was also the first musical, maybe the first Broadway stage piece of any sort, to deal with what today would be called disaffected youth but was then termed juvenile delinquency.

Its arrival had been a long time coming, as Bernstein and playwright Arthur Laurents periodically met with choreographer Jerome Robbins in the late ‘40s to flesh out Robbins’ idea to develop a New York story out of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. Robbins and Bernstein had worked brilliantly together before in On the Town and Fancy Free, and enjoyed a creative marriage famously made in both heaven and hell. An early version depicted Jews having it out with Polish-Italian Catholics in lower Manhattan. Scheduling conflicts and availability kept the three from meeting in earnest, and by the time they did, the look and sound of New York, indeed the nation, had begun to show a Latin flair.

West Side Story is mostly Robbins’ baby (he directed as well as choreographed), but with the addition of Stephen Sondheim as lyricist, this became one of those collaborations in which each partner’s contribution is utterly essential.

Bernstein was the one who got it right away. His no-nonsense prologue, consisting of a brassy pair of terse three-note phrases, sounds like a blunt call-out to rumble followed by a nervous, agitated prelude to something awful and unavoidable. (Don’t listen to the movie overture, which like all overtures is designed to introduce the comfort of familiarity. West Side Story is not about comfort.) His orchestration (aided by Sid Ramin and Irwin Kostal) added conga and bongo drums, castanets, clavels, woodblocks and timbalis to Latinize the standard pit band of brass, strings and percussion. His contrapuntal use of tritones and diminished sevenths, among other devices, keep us unsettled, uncertain, in the dark about how things will play out. Robbins’ choreography followed suit, filled with the explosive energies of youth, sex and the proximity of violence.

One of the elements that make it work so well is that every song is indispensable to the development of the story and its characters; even “Gee, Officer Krupke,” as funny as it is (“I’m depraved on account of I’m deprived”) points to the awkwardness of social institutions dealing with kids who feel like outcasts, including Anglo kids. Virtually every other song follows the pulsing arc of youth’s innocence and ardor, and what happens when it runs into devastating tragedy. “Something’s Coming” is every young person’s breathless anticipation of a terrific life ahead. In “Maria,” the name of one’s first love is as sweeping as the horizon. “One Hand, One Heart” reveals us under the skin. After such a dazzling fearless beginning for Tony and Maria, Bernardo and Anita and the rest of the Jets and Sharks, everyone realizes at the end, in the funereal “Somewhere,” that there’s got to be a better place than the ghastly one they’re in now. The aria duet, “A Boy Like That,” rises to a shattering pitch that reminds us how song erupts when emotional intensity is too great for any other kind of expression.

That production won three Tonys and numerous other awards in subsequent revivals. The 1961 film won ten Oscars, including Best Picture, even though its overblown production values snuffed out the play’s sizzle. Bernstein resented the bloat added to his score, which he and reshaped into a symphonic suite that’s now a staple with conductors everywhere, and a favorite of our latest young titan of the podium, Gustavo Dudamel.

Robbins’ contribution is less vividly remembered because dance is so evanescent—it ends with its own movement, and you can’t retrieve it through an earbud. Bernstein’s lyrical passion informed “West Side Story’s” troubled soul, as his passion informed virtually everything he did. He was uncorrupted by irony. The exuberant variety of his life and talents has made us all the richer.

A centennial exhibit on the life and work of Leonard Bernstein opens at the Skirball Cultural Center, Los Angeles, on April 26

February 21, 2018

Julian Lage at the Bootleg Theater

LAST night’s show by the young Santa Rosa native was one of the greatest jazz gigs I’ve ever seen. Even knowing a few of his records and having seen him play a delicate, restrained, kind of perfect show with pianist Fred Hersch a few years back, I was knocked out by how fleet his playing was, and how well-matched to a more assertive style than I’m accustomed to.

Lage, a onetime child prodigy who turned 30 a few weeks ago, is currently wielding a Telecaster, and playing standing up, with a powerful trio; his new LP, Modern Lore, echoes rockabilly and surf guitar as much as it does Eddie Lang or Wes Montgomery. In some ways he seems like the jazz-guitar version of Brad Mehldau, another player who mixes great facility with strong emotion and has been able to engage a relatively young audience. But this is not cheesy fusion or a forced art/ pop marriage — it feels real.

This clip, from a 2016 show at the Blue Whale, gives a sense of his current style. (He plays with a different bassist and drummer these days.)

Let me add that while the Bootleg — at which I’ve seen a range of things, from indie rock to a one-man-show — is always a place I end up enjoying. Intimate and cool in a way I can’t put my finger on.

For what’s it’s worth, there is a new list of best jazz guitarists — here — which has some wonderful clips. I don’t concur with all of it, but I’m glad to see Grand  Green up so high. And worth nothing that Lage is the youngest here.

Green up so high. And worth nothing that Lage is the youngest here.

February 9, 2018

Southern Literature and the Drive-By Truckers

CELEBRATED Yale historian C. Vann Woodward used to talk about the irony of Southern history, and the burden of Southern history, both phrases drawn in part from the novels of Faulkner. Patterson Hood, a son of Alabama who spent several decades in Athens, GA, before leaving the South like many a literary character before him, has made a fascinating songwriting career exploring what he calls “the duality of the Southern thing.”

The latest installment of my All the Poets series in the Los Angeles Review of Books is a discussion with Hood about his childhood and current reading. For a few months I’ve been engaged in a running conversation with Hood, who is as deep and complex a guy and you’d guess from his music. His father is a longtime bass player at Muscle Shoals studio (and one of the founding members of its legendary rhythm section), so young Hood would hear about his dad playing R&B with Etta James or the Staples Singers while Gov. George Wallace thundered against black people.

Hood and I spoke about To Kill a Mockingbird, Robert Caro’s Lyndon Johnson books, and R.E.M.  HERE it is.

HERE it is.

I’m glad to say that the Truckers — a devastating live band whose most recent LP, American Band, is clearly one of the decade’s finest — play tonight in Los Angeles and may be coming to a city new you.

February 1, 2018

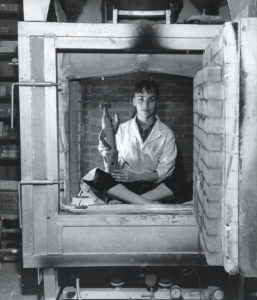

Artist Dora De Larios, RIP

UNDERSUNG but widely respected, the sculptor Dora De Larios has been working in around Los Angeles for six decades now. I was pleased to be asked to write about her for Los Angeles magazine, and was able to tour her daugher’s house, where a wide range of her sculptures and ceramic work sits.

What interested me about De Larios’ work right away was how firmly it sat in a tradition — pre-Columbian and Mexican-American — while also demonstrating and individuality that was simultaneously personal, distinctly Modern, and contemporary. HERE is my piece on her.

My contact with De Larios — who was ailing at the time of my reporting — was minimal, though she answered some questions quite lucidly for me. I was quite floored, even knowing the state of her health, to hear she passed away a few days ago. (This story was not easy to write, but am very glad we did.)

Here is part of a note from the museum director, Allison Agsten, who provoked and curated the show:

I met Dora De Larios last year after getting in touch to see if she might be a fit for the commission of a new public artwork that would welcome visitors to the museum. Almost immediately, I knew she was perfect for the project, and more importantly, that she needed a major exhibition. As a Mexican-American, a woman, and a ceramist, she did not receive the recognition she deserved in her long career that began in the late 1950s.

A show coalesced quickly. In the last few weeks, Dora enjoyed reading the beautiful stories that came out about her work and the upcoming exhibition, Dora De Larios: Other Worlds, in Los Angeles magazine, LALA magazine, the LA Times, and many others. It seemed like we could hardly keep up with the press and it brought us all so much joy to see her enveloped in the recognition she had always deserved. Even better would be seeing Dora bask in the glow of her exhibition. But we did not make it in time. Dora passed away after a protracted battle with cancer on January 28. I was, and am, devastated.

A career retrospective goes up on February 25 at the Main Museum in Downtown LA. I’ll be there. RIP, Dora!

January 30, 2018

Joe Henry, Poetry, and The Blues

LIKE a lot of listeners, I’ve long considered Joe Henry to be a smart and vaguely literary songwriter — smart, more-or-less sensitive, good with words. But I was pleasantly surprised when Joe came out of the closet about his love of poetry, and since it coincided with the release of the powerful, understated record Thrum, I made sure to corner him for an interview in my series on musicians’ literary interests.

Joe is, of course, a musician, songwriter and bandleader who falls somewhere between the blues, Americana or alt-country, and acoustic Dylan. While he made a record (and triumphant tour) about train songs with the very English musician Billy Bragg, Joe always signifies heavily American. (Born in North Carolina, Joe has always had a touch of old US folklore to him, and a few years ago I wrote about his record, Blues From Stars, which came heavily out of the Delta blues of Robert Johnson, Skip James, and Son House.)

So I was startled to hear how deeply he was into several foreign language poets, including the German Rainer Maria Rilke (an obsession of me during collegiate trips through Europe.)

But many of his passions were in fact American. After talking about his youthful passion for William Carlos Williams, for example, we pivoted to one of my very favorites (pictured):

Right there in tandem with Williams — and both came courtesy of my older brother David, who has been my lifelong mentor — was Wallace Stevens. And with Stevens the lesson I learned, and took very much to heart, is that I don’t think Stevens was taking pre-formed thought and trying to translate it into the music of language — he was listening to language as music, and following it, to hear what it had to say. Just like Joyce, he was listening to the music of language, to hear what it meant. Language is leading him to thought. It’s the way I live as a songwriter and poet. The act of writing is listening and learning — it’s how I find out.

In any case, HERE is our conversation, which may be my favorite of this series so far. (A new one drops this Friday, by the way.)

January 24, 2018

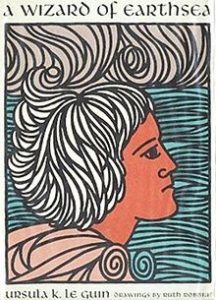

Remembering Ursula K. Le Guin

THERE may be no contemporary writer who’s shaped me, and many of the authors of my generation, more than Ursula Le Guin, who died Monday. Even though she was nearing 90, Le Guin is the kind of person who seemed like she would live forever: When I flew up to meet her in Portland a decade ago, she seemed so physically solid and intellectually sharp, she came across like some kind of otherworldly creature, maybe crossed with a 19th-century Oregon homesteader.

In the grammar-school years, before I read much fiction, my school-teacher mother brought home a book her librarian had recommended, A Wizard of Earthsea. I dove into it; it helped that I was an enthusiastic small-boat sailor as a kid, and I spent the ensuing years, as I got into the later books in the cycle, imagining having magical adventures on enchanted, vaguely Jungian adventures as I sailed down Maryland’s waterways.

As a teenager I would dive hard into The Left Hand of Darkness and The Dispossessed, and decades later would read the Earthsea books to my young son. When I go back to her work now, I’m struck — as I am with the Beatles — by how well these childhood memories stand up the an adult’s eye and ear.

Here are a few things I remember from my visit and subsequent conversations:

Despite her reputation as prickly and stubborn, she was easy to get along with, and we spent an hour or so after the heart of my interview was done drinking a local ale on her porch, talking about writers and musicians we liked

Le Guin, then Ursula Kroeber, studied French and Italian literature at Radcliffe because, as she put it, she did not want anyone telling her what to read “in my own language”

She spoke fondly of the generation of authors who saw her as a godmother figure — Michael Chabon, Jonathan Lethem, David Mitchell, Kelly Link

Le Guin, a native of Berkeley who spent most of her adult life in Portland, was very conscious of being a West Coast writer who the New York literary establishment did not quite get

She recalled getting a letter from Berkeley High School classmate Philip K. Dick, who she had, oddly, never met, asking if he could visit her, sometime in the ’70s. She admired his work a great deal, but he was so deep into what she called “the drug culture” that she dodged the invitation

Le Guin came from an entirely different part of the century than most people I know: She was born a week before the stock market crash the kicked off the Great Depression. She mentioned, when me met, that she could never forgive Einsenhower waiting until his farewell address to offer his famous warning about the military-industrial complex. She saw it as a failure of nerve

Weirdly, she and I once got into a fight of sorts when she thought (long story) that I was a Scientologist. “This conversation is over,” she told me. (She totally hated L. Ron Hubbard.) We quickly sorted it out

Among the very few writers she liked as much as Tolkien and Woolf was Lord Dunsany and Patrick “Master and Commander” O’Brian

Le Guin learned Latin, in her late 70s, to write her book set in pre-imperial Rome, Lavinia (which is a great novel)

She was always witty, and had a great sense of humor about herself and this vexing world

I’ve written about her, if memory serves, three times

Here is my LA Times profile from 2009

Here is Guardian essay where I link her to David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas and other Gen-X novelists

And here is my Salon interview with her about her slim, practical book on writing

For what it’s worth, I am working on a book project about artistry I wanted to speak to her about, and damn am I mad I did not think to reach out sooner

To have her disappear like this is heartbreaking. Rest in Peace !

Scott Timberg's Blog

- Scott Timberg's profile

- 7 followers