Scott Timberg's Blog, page 3

August 20, 2018

Max Richter and Classical Minimalism

When it comes to a classical concert, how long is too long? What do you do when you get restless? And what state — one of heightened curiosity? a sharpened intellectual edge? greater empathy? physical relaxation? — should a piece of art music put its audience members? In what way is art meant to be transformative?

These are all questions addressed, implicitly, at least by the Max Richter composition Sleep. Released on DG to great acclaim — especially in the UK where it was championed by figures including Jarvis Cocker — as well as some skepticism (several music critics and classical musicians I know are not moved by it), the piece was performed recently in downtown Los Angeles’s Grand Park. All eight hours of it — with cots for the audience.

Here is my interview with the German-born, English-dwelling composer, who has roots in both the classical mainstream and the British dance music of the 1990s. (Apologies for being a few weeks late on this one; I’d thought I had posted and then overwork took my eye off the ball. I post it, even though it’s late, largely because Richter is still performing Sleep in its full or shortened “From Sleep” versions, though I’m not aware of any more outdoor concerts; this was the first.)

I attended the concert, which was, of course, unlike anything I’ve ever experienced. (It was also a bit colder/ damper at night than I’ wagered.) The sound system was amazing — full enveloping no matter where I strayed. And while I found the entire time fascinating, the highlight was waking about an hour before Sleep‘s conclusion, seeing first beginnings of pale light in the sky, with City Hall looming behind the musicians, sensing that the piece was gradually returning to the tonic (or whatever piece does), with a combination of grogginess and rebirth. It made me think, at least briefly, that the previous seven or so hours had been preparation for the final epiphany.

In any case, Richter and his co-conspirators — the ACME Quintet and soprano Grace Davidson — certainly won my over with this one.

July 30, 2018

The Music of Inequality

Remember the recession? A lot of Americans had their lives turned upside down by it. But popular music — however you define the term — never really engaged with the crash itself, or the widespread suffering and steep inequality that followed. In a new story for Vox, I looked at a wide range of American music released over the last decade, since the stock market crash of 2008, for signs of rap, country, rock and other musicians engaging with one of the most transformative events in U.S. history.

I tried to get at some of the best examples of songs that look at economic structures, income inequality, and the failings of capitalism. I also tried to ask, Why is there not more of this? What does it tell us about the U.S. and American culture?

July 27, 2018

Ayn Rand and Libertarianism

FOR most of my life — I was a kid during the Reagan Revolution — I’ve been puzzled by otherwise smart people falling for Libertarianism and Ayn Rand’s brand of freedom snake oil. Everybody likes the idea of freedom, but for the Fountainhead crowd, the notion acquires cartoonish dimensions, and their definition of the term seems to tilt toward rich businessmen and other Uber-menschen.

If you live in a more-or-less urban, blue-state, college-educated world, you probably don’t overlap a great deal with conservatives who come from an evangelical, agrarian, or even (depending on your generation) neo–con point of view. But you’re likely to have a bunch of friends or colleagues who are or were Randians or Libertarians.

The American conservative movement and the Republican party in particular has been through a series of love affairs and breakups with the Randtites. There are always an array of right-of-center groups, rearranging and reforming. The current political situation is as confusing and unstable as the current occupant of the White House, so it’s easy to find observers who see the Libertarians’ day as being over, as Southern evangelicals, say, or law-and-order conservatives push them aside. But Ayn Rand fans in finance, the alternate universe of think tanks, and Silicon Valley exert a huge influence on 21st century politics.

In any case, here is my essay for the Los Angeles Review of Books, which looks at two newish books and, briefly, an older one.

July 12, 2018

Guest Columnist: Mr. Rogers, and America

I’M hardly the only Gen Xer to grow up on Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood, a show that first aired about a year before I was born. Part of me thinks that my fondness for the program comes from the fact that my frequent viewing companion — my maternal grandmother — was, like Rogers, a Pittsburgh Presbyterian. But Rogers and his show imprinted itself on all kinds of people, from all kinds of places: I suspect many of them felt, as I did, that he was speaking directly to them.

In any case, guest columnist Lawrence Christon picks up the story a bit later, and describes a wrinkle I did not recall. Here he is.

THE NIGHT AMERICA CONFESSED ITS LOVE FOR MISTER ROGERS

By Lawrence Christon

The nationwide release of Morgan Neville’s documentary, “Won’t You Be My Neighbor,” the story of PBS’ “Fred Rogers’ Neighborhood,” has unleashed a considerable amount of editorial anguish over an American lost innocence, particularly in contrast to our venal age as personified by Donald Trump.

Rogers, the subject of “Won’t You Be My Neighbor,” has been held up as the better angel Abraham Lincoln evoked in his hope for a definitively blessed American character. “Simple and deep” was Rogers’ constant theme, as he emphasized—particularly to children–the irreducible integrity, worth and uniqueness of every human being alive, however lonely, frightened, bewildered and even scorned. “The world desperately needs more people like Fred Rogers,” has been the consensus. “We wish he were still with us” (Rogers died in 2003).

Wrote David Brooks in The New York Times: “His show was an expression of the mainline Protestantism that was once the dominating morality in American life…Rogers was drawing on a long moral tradition, that the last shall be first. It wasn’t just Donald Trump who reversed that morality, though he does represent a cartoonish version of the idea that winners are better than losers, the successful are better than the weak. That morality got reversed long before Trump came on the scene. By an achievement-oriented success culture, by a culture that swung too far from humble and earnest caritas.”

Audiences weep during the film. Hardened journalists write of how disarmed and even intimidated they felt at meeting and interviewing Rogers, an ordained Presbyterian minister who never talked about God in his show or in his public discourse, instead emphasizing what he told children, in one way or another, every day it aired: “You make things special just by being you. I like you just the way you are.” Asked by a PBS Newshour interviewer, “Was he the real deal?” Neville, a former neighbor to Rogers in Martha’s Vineyard replied, in effect, “I never saw anything to indicate that he wasn’t. I’d have to say, yes, he was.”

Aside from his target audience of children however—estimated at one point to number a third of all the pre- and elementary school kids out there—Rogers was not always the object of such unqualified devotion. Quite the opposite, in fact. The first airing of “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood” took place on February 19, 1968, on Pittsburgh’s National Education Network. It was produced on a budget of $30, but was quickly picked up by PBS affiliates all over the country. It seemed a wonderfully safe, low-key, harmless break from a country boiling over with counterculture anger and protest, campus and street demonstrations and bloody fights with police (as in the Democratic National Convention in Chicago) and the bitter division over the war in Vietnam.

Rogers stayed out of politics, but he couldn’t escape the tyranny of hip, which began in the mid-to-late ‘50s with cool jazz, rock ‘n’ roll, heroin and weed, the celebration of the rebel and anti-hero (as in Brando and “The Wild One”). By the ‘70s and ‘80s, hip came indoors to the corporate suburban world, hardening into a general reflexive attitude of irony and derisive posturing that remains de rigueur. As the novelist Ottessa Moshfegh recently described, in a New Yorker profile, the insufferable hothouse atmosphere of literary Brooklyn: “…you have to break the mold, blow people’s minds, do it perfectly, and then not care. Because if you care you’re not cool, and if you’re not cool you’re shit.”

This does not describe Fred Rogers.

Clearly his respect for children, and his gentle insistence that every one of them had an unarguable reason for being on the earth, had given him some kind of widespread appeal. But the nature of his show, simple, slow, warmly reassuring, infinitely patient, unfailingly kind—itself childlike–seemed the antithesis of hip. When he first came on Johnny Carson’s Late Night Show, Carson, with his subtle protean array of tics, twinkles, smirks and expressions that signaled to an audience what to think of a guest, labeled Rogers some kind of well-intended rube. For decades, and for those self-consciously compelled to be in on the latest thing, the label stuck.

On a single night, with one sudden gesture, all that changed. On January 6, 1993, Arsenio Hall called Rogers out on stage for The Arsenio Hall Show. At first sight of Rogers, the mostly young Paramount Studio audience sent down that faintly derisive cheer that had become standard for people who considered themselves superior to him and his kidstuff. But Hall raised his arm, the palm of his hand facing outward: Stop. This is Mister Rogers in the house.

Instantly the audience’s tone changed, from snark to something more wholesome, more deeply heartfelt. It was as though every one of them was instantly transformed into the child each had been, home alone maybe as a latchkey kid, uncertain, anxious, full of questions about the scarifying world looming all around them, little questions like learning to tie shoelaces, big questions like death, divorce and the murder of a public figure. And there was Mister Rogers in front of them on TV, talking to them directly as if they were alone together, making them feel safe and cherished and an important part of a beautiful neighborhood. They cheered because they couldn’t bear to cry. He’d been their special friend who never let them down. And now he was part of their neighborhood, Hall’s Dog Pound. Hall even gave him an official jacket. Best of all, as they listened to him speak, they saw that he hadn’t changed. After that night, it seems, to snicker at Fred Rogers was not a smart thing to do.

We hear plenty about the force of evil, because it’s always more shocking and unexpected, more lurid and inexplicable. But you have to wonder about the force of good as well, whether in the small acts of kindness and courtesy we experience every day, or the more heroic demonstrations of courage and ingenuity as shown by the strangers who came from all over to rescue a group of kids from a watery cave against all odds. Is goodness more like white noise, steady and unobtrusive, there for us, within us, ready to answer to an appeal? Is it a power too? Fred Rogers would make us think that it is.

July 9, 2018

The Dark Magic of Ottessa Moshfegh

IT’s not often that I pick up a book and get a new favorite writer. But that’s pretty close to what happened when a story collection called Homesick For Another World, by a young author I’d not heard of, arrived in the mail one day. I read a few dark, alienated short stories, some of which were set in a dreary, bleached-out, dingbat-lined Los Angeles. I found a noirish novella called Eileen, and devoured its grim Patricia Highsmith-like tale in record time.

In few days Ottessa Moshfegh’s new novel,  My Year of Rest and Relaxation, comes out. It’s in some ways different from the novella — the plot is more minimal, or at least more internal, as it mostly concerns a character trying to spend a year in a New York apartment doing just about nothing at all. But the combination of bitterness, bleak humor and writerly control is identical.

My Year of Rest and Relaxation, comes out. It’s in some ways different from the novella — the plot is more minimal, or at least more internal, as it mostly concerns a character trying to spend a year in a New York apartment doing just about nothing at all. But the combination of bitterness, bleak humor and writerly control is identical.

A few weeks ago, I met Moshfegh — who grew up outside Boston but now lives in Hollywood and the high desert — for a coffee. I was struck yb a few things, including her early interest in what she called “black male” writers like James Baldwin, Richard Wright and Ralph Ellison, in part for their sense of internal exile.

In any case, my brief profile of her is not yet online — I will post it if it comes up — but here is a review of her latest by Dwight Garner in the New York Times. She’s not always an easy read, but she’s the real thing for sure.

July 5, 2018

Guest Columnist: A Break in the Performance

Regular CultureCrash guest columnist Lawrence Christon has a new piece about an incident in St. Louis that brings together a number of tendencies in the arts. Of course, the situation he writes about echoes both forward and backward in time; cultural appropriation has become one of the most contested issues lately and seems likely to remain that way. I don’t concur 100 percent with the pieces my guests write here, this one included,  but am glad to kick off a discussion here.

but am glad to kick off a discussion here.

By Lawrence Christon

The arts in general, and particularly the theater, can ill-afford the kind of disruption a bunch of Theatre Communications Group observers visited on St. Louis’ Muny Theater earlier in June, when they booed a scene from The King and I and objected to elements in the theater’s staging of Jerome Robbins’ Broadway. Not only was it disrespectful to other theater pros (not to mention the audience) in the name of being disrespected, it was yet another grim example of art in America becoming hammered into timid mediocrity by the forces of political righteousness on both the left and the right, and even the liberal center.

In case you missed the news, here’s what happened:

A sub-group of TCG conferees went to a Muny staging of segments from American musicals and booed both a scene from On the Town, which included the depiction of a Native American headdress, and yelled “No yellowface!” at a white actress playing the part of Tuptim. (‘Yellowface’ refers to the practice of casting white performers in Asian roles.) The protesters were led out of the theater without further incident and later released a statement that read, “representatives of theaters of color nationwide demonstrated the power of collective resistance to systemic oppression of people of color. When those who benefit from systems fail to acknowledge the ways in which those systems oppress others, it limits our ability to live up to the promises of who we say we are as a nation.”

Mike Isaacson, artistic director and executive producer of the Muny, was sitting in front of the protesters and felt both blindsided and offended.

“That piece,” he said, referring to The King and I scene, “was led by two extraordinary Asian-American dancers, and the director of the show is an Asian-American woman. What’s very painful to us is that this is a theater of inclusion…our history with diversity on our stage, and Asian-Americans and African-Americans, I stand behind very strongly and very proudly.”

Later, Isaacson cancelled his appearance at an awards ceremony for fear of being further heckled, and later issued an apologia for causing hurt and offense.

While the incursion of public anger and protest into the private spaces of politicians has been making the news lately, stuff like this has been going on in the arts for as long as there have been people on the lookout for offense.

The first wave of this crested in the Reagan ‘80s, in tandem with the closing of a Corcoran Gallery exhibit of the gay sadomasochistic photos of Robert Mapplethorpe, in Washington, D.C., and, in a separate category, outrage over the 1987 Andres Serrano photograph “Piss Christ.” Though not specifically related to questions of race and ethnicity, these dovetailed with culture-war arguments over multiculturalism. They pointed to how, almost overnight, the Reagan presidency had brought The Moral Majority and other eruptions of far right assertions into public life, and with them, vehement counter-assertions challenging the whiteness of the western Canon.

Multiculturalism, while timely and inevitable—the centuries-old growth of international transportation, trade and dialogue has guaranteed a widening layer of cultural sophistication among disparate societies—became a vehement counter-reaction. Protesters gathered outside The Broadway Theater to protest the casting of Jonathan Pryce as a Eurasian in Miss Saigon, among many other kids of demonstrations, and the entire movement took on an intensity described by Robert Hughes in Culture of Complaint, The Fraying of America:

“[Multiculturalism] in fact means separation. It alleges that European institutions and mental structures are inherently oppressive, and that non-Eurocentric ones are not—a dubious idea, to say the least. The sense of disappointment and frustration with formal politics has gone down into culture, stuck there and festered. It has caused many people to view the arts mainly as a field of power, since they have so little power elsewhere. Thus they also become an arena about rights.”

In a society saturated with the debasing values of mass media, Hughes adds, the arts have less and less power to inform human experience. And in the clash between left and right, as Robert Brustein observed, there’s been no one left to speak for the autonomy of art. Television and the screen are ubiquitous now, deleting history, vanquishing thought in favor of clickbait’s narcotic hit, and the liberal center seems incapable of defending the arts without calling up data-driven reports on its educational and therapeutic benefits.

In a culture of narcissism, the personal and the political indeed become interchangeable. The question is, should they? Is the person who holds different political views your mortal enemy?

There are larger implications of the Muny disturbance, the most obvious being contempt toward the magical ability of a performer to convince an audience of anything. Must art always be literal, factual, quota-driven? Is there a quantitative way to insure that every minority, disabled, gender-nuanced and ethnically specific group be proportionately represented in a performance? Who decides? Who enforces? What are the fascist implications here? Which group is empowered to judge?

And what, pray, does it mean for the freedom of any artist or group of artists to shove off into the hazardous unknown in conceiving new work and bringing it to fruition without looking over their shoulders at a spectral censor?

In the meantime, critic Bill Marx, in Arts Fuse, wonders why, since the debut of Angels in America, “we have not had any successful American play (non-musical) that approaches its inspiring size, ambition, imaginative breadth and political provocation. Why the 25 years or relative modesty? And where are the complaints? Why the pervading sense of smug self-satisfaction among our critics and theater-makers?”

Is there a link? Big question, with many replies. Economics. Increasing unfamiliarity with the human scale. Discomfort with intimacy. Impatience with the complications of experience. Politicization has to be one of them.

One thing is certain: the modern classic liberalism of the post-war era, which insisted that the life of the artist and the life of the art are distinctly different entities, is dead. Intellectuals like Lionel Trilling. Irving Howe and Edmund Wilson instinctively saw literature and the arts altogether as inherently moral critiques of society that went far deeper than racial and gender representation and their deadly accompanying cant.

All this is a lot to load onto a couple of musical numbers, but it says something about where we are in our historical moment, where it’s easier for us to shout each other down rather than stop to mourn the damage we do.

July 2, 2018

Handguns, the Press, and Annapolis

Almost a quarter century ago, I worked as intern, in my last year of journalism school, at the Baltimore Sun. This was a rough few months for me — I earned nothing for five-days-a-week in the paper’s features department, the city was experiencing a crime wave right up to the edge of my neighborhood, and I was breaking up with a pretty serious girlfriend during just about that entire term. But I have fond memories of most of the writers and editors I worked with there — all but one were really supportive, friendly, and taught me a great deal about the craft. The Sun had a reasonably new team at the helm and was becoming a stronger, more ambitious paper.

Among the stories I enjoyed reporting and writing the most was a piece on author Erik Larson, who later became known for bestselling nonfiction novels (The Devil in the White City) but who at the time had a book called Lethal Passage. This was a straight — and brilliantly executed — journalistic account of a single handgun from Virginia, and the journey it took before being used in a mass shooting: One of those “behind the headlines”/ “beyond the statistics” accounts that operates through depth and nuance. The book was in some ways a cautionary tale about handguns in America but not really a piece of polemic.

My story was mostly about Larson (a Seattle resident spending a few months in Baltimore because of his wife’s term at Johns Hopkins, I think), but because his book concerned a contentious issue, journalistic standards of balance required I get a comment from what we call a “gun rights advocate” to counter Larson’s point of view. I found some NRA-approved guy who had not read the book to explain why liberals like Larson are always wrong and a danger to the republic.

I don’t recall discussing my story with Rob Hiaasen, a Sun reporter who sat almost next to me and was a consistently cheerful, encouraging figure in my life then, full of reporting tips and friendly witticisms to help me and the rest of the staff get through the day. But what if when I was reporting and writing that story, I had known the the nation’s lax gun laws — and whatever other foul stew of press-hatred, political toxins, and so on — would mean that Rob would be gunned down 24 years later? Would the issue have seemed different to me then?

During the collapse of the Sun — thanks to Tribune Corps and Sam Zell — Rob had moved to the Annapolis Capital to become one of the main editors there. That little, generally modest paper was the reason I grew up in Maryland: My father, mother and I had driven across the country in 1970 from Palo Alto, CA, where my father had earned a journalism master’s, to take his first newspaper job. He worked there a few years, but we stayed in and around Annapolis for my entire childhood; before and after college elsewhere I worked at nearly every bar on the docks there.

Last week, an angry, press-hating man, enraged by the paper’s coverage of his harassment of a woman, broke into the Capital newsroom and killed Rob and four others. All of these are tragedies, but for everyone who knew Rob — someone it’s simply impossible to imagine anyone not liking — it’s inconceivable.

I’m too appalled and emotionally exhausted by the whole thing to say any more, but someone who knew Rob far better than I did, Laura Lippman, has written a deep and resonant piece on him. Laura came into the features department almost exactly when I was leaving to take my first job. We have a few things in common — we are both the offspring of veteran Sun journalists, we’re both goyim with Jewish names, and my memory is that she is a fellow admirer of jazz trumpeter Chet Baker. Unlike me, she is a brilliant/ bestselling mystery novelist.

Novelist Laura Lippman

In any case, here is her New York Times piece on Rob. RIP to a fine writer and truly great guy. This brings the whole gun argument home for me. When I subtitled my book “The Killing of the Creative Class” I did not mean it literally, but these are the times we live in.

June 21, 2018

Martin Amis on Poetry and Posterity

AS smart and funny as his novels are, Martin Amis is a devastatingly good essayist as well. I spoke to him recently about his latest collection, The Rub of Time, which assembles several decades of nonfiction pieces.

The subject of the book is the toll taken by the ages — the way it gradually erodes talent and inspiration as surely as it does the soil on a hillside. (Nabokov, Bellow, and the late, great Philip Roth are three touchstones.) We touch on, of course, Amis’s close friend Christopher Hitchens.

But the book is all over the place, and shows Amis’s own powers so far undiminished.

My conversation, in the Los Angeles Review of Books, is here.

June 11, 2018

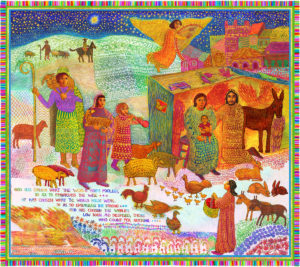

The Sacred Art of John August Swanson

EVEN as a lifetime religious skeptic, I’ve long been fascinated by artists, writers and other culture-makers who bring religion, spirituality, and related matters into their work. Most likely, the art impulse and the urge to worship and praise originated in tandem; what we now call religion and culture were almost seamlessly joined for many centuries. (The agnostic or atheist or iconoclastic artist is, if we take the long view, a historical anomaly.)

In a sense, then, the painter and print-maker John August Swanson is something of a throwback: Swanson, who I met a few weeks ago, has a wide range of interests, but his work is very heavily inspired by Christianity, especially the social-justice wing of Catholicism. He’s influenced by a wide ranger of artists, especially Renaissance painters, Diego Rivera and political printmaker Sister Corita, with whom he studied. He’s got a touch of the Outsider artist to him, though his roots and technique don’t quite fit with most of the others.

I enjoyed meeting Swanson immensely and getting to know his work. Here is my story for the Loyola Marymount University magazine, just out.

June 4, 2018

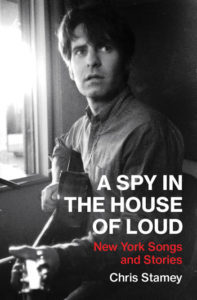

Punk, Indie Rock and Power Pop With Chris Stamey

Though he’s hardly a household name, North Carolina’s Chris Stamey has been just alongside many of the key developments in left-of-the-dial rock music over the last four decades. As a teenaged Southerner he visited and then moved to New York City right as CBGB’s and Television were exploding, he helped found the dBs and Let’s Active, which put him on on the ground floor of the Southern pop movement that produced R.E.M.

has been just alongside many of the key developments in left-of-the-dial rock music over the last four decades. As a teenaged Southerner he visited and then moved to New York City right as CBGB’s and Television were exploding, he helped found the dBs and Let’s Active, which put him on on the ground floor of the Southern pop movement that produced R.E.M.

Stamey played for a while with Big Star’s Alex Chilton, later produced Ryan Adams’ old group Whiskeytown, riot grrrl trio Le Tigre, and Texas troubadour Alejandro Escovedo. He’s also had a busy solo career, and collaborated now and again with fellow dB Peter Holsapple.

I was pleased and curious when I heard that Stamey had a memoir coming: In 1992 I moved to Chapel Hill, NC, to go to graduate school, right around the time he was landing back in his native state after years in New York. Stamey and his acoustic guitar were frequent sites on Franklin streets and the coffee houses there; I saw him play numerous times, a friend and I often shouting a request for September Gurls.

Still, I was surprised at how smartly and incisively written the ensuing book, A Spy In The House of Loud (subtitled New York Songs and Stories) ended up being.

What follows is my exchange with Stamey via email.

Give us a sense of the radicalism of the music happening in New York in 1975: You arrived for a visit, as a very young man, just as CBGB’s was starting to rage and right before the release of Television’s Little Johnny Jewel single. How did the best of that music break from American rock at the time, including what you were hearing around in ’70s North Carolina?

Some of the music at and around CBGB stretched arms out to the past: the music of both Blondie and the Ramones referenced 60s rock, Spector and Leiber and Stoller girl-group chords and chipper melodies and sometimes even the baion beat, just played faster and louder, and without the strings. In doing so, they sailed right over the 70s arena pomp and cornball theatrics, as if it had never happened. (The New York Dolls, a bit earlier, had been a gateway to these attitudes.)

In those years I was much more captivated by Television, however, who had roots both in free jazz and the Romantic “classical” tradition, musically, and in the French Expressionist poetry tradition, both lyrically and philosophically. They seemed to have very few antecedents in rock from the past, 70s or otherwise, and they worked really hard at it. I also heard, in their music, some of the “mid-century Modern” music techniques I’d been learning in music school, which I liked.

The Talking Heads, who followed on their heels and often played shows with them in the early days, also shared that “stench of the new,” bringing in elements of the visual art world and of dance grooves, trying to find a way to evolve and move the music forward with each album release.

All of these folks, including Patti Smith and Richard Hell, wanted something new, felt that a palace revolution was immediately necessary, that there must be something better out there to find.

When you formed the dBs, were you conscious of going against the grain of the musical mainstream? What it was like to form an indie band in that time and place, and what were you and the rest aiming for?

Although the dB’s was formed by accident — Gene Holder and Will Rigby joining me “temporarily” to promote a song that Richard Lloyd and I had recorded/created without them — it persisted because we liked the way it sounded and liked hanging out with each other. It grew organically, and then exponentially when Peter Holsapple came up to join us. We’d been in so many bands in NC, for the last decade, including Sneakers (me and Will), and they were I guess all “indie bands.” So this was part of that continuum.

We were aiming just to find out what we were about, in the laboratory setting of late-nights in clubs and long days in rehearsal. But I think songwriting was key — both Peter and I wanted to bring a new song into rehearsal and then bask in the glow if it caught fire with the quartet. And when that would happen, it’d be a great incentive to do it again. Any kind of larger cultural recognition seemed pretty remote, frankly, when the band formed.

This book is extremely well written, with a strong writer’s voice, nicely drawn scenes, a sense of history, and so on. It’s kind of impossible to know for sure, but do you have a sense of how you learned to write – what books or ideas or experiences guided you to be able to do this?

Thanks for saying this! I never had any creative writing classes, or even any post-high-school English education. I did have some philosophy classes in college, and from that learned that it’s possible to be precise, that a sentence could be a kind of math, an equation that is either true or false. Of course, it’s hard to always hold to that standard, especially when writing about something that sweeps you away, but I keep trying. I don’t kid myself: I’ve got a long ways to go, it’s a struggle. (Both Will Rigby and Peter Holsapple, from the dB’s, are good writers, fyi. Peter had some J-school experience, like you did.) Right now, I’m reading The Elements of Style, slowly and carefully; too bad I didn’t do this before writing the book. With music and recording, I’ve generally found that I learn faster by jumping off into the deep end, and this first attempt at writing was also a “sink or swim” educational process.

I do have to recommend Betty Edwards’s Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain as a good book for songwriters and writers in general. I enjoyed writing the “radio musical” Occasional Shivers last year (a podcast available for free on iTunes) and I’m currently writing the sequel to this, for actual theaters this time. It’s set in Philadelphia and tentatively entitled Give My Regards to Off-Broadway (Remember Me to Rittenhouse Square). And I’m also barely into writing a short novel, called The Dad Joke Club.

What are your favorite books about music – memoirs, criticism, Mystery Train-like cultural histories, etc.? Were any of them a model for your book?

I have checked out a lot of music memoirs from the public library in the last decade, reading them in fits and starts before falling asleep at night, and from them I took what I didn’t want to do — be boring for long stretches, settle scores, etc. I did not think of my book as a memoir, though, when I was writing it, and it’s still the case that it’s not really about me as much as about my songs . . . and others’. (In fact, a book about me would be quite different.)

I thought of it as a book about songwriting, in a way: I wanted to communicate some of the excitement I found in different kinds of music, and then to explore what made it exciting for me. And I wanted to find things that might put someone in the mood to put the book down and go create, in the same way that Barry Miles’s book with Paul McCartney, Many Years from Now, did for me on occasion. Now, after a while, as happens with any creative effort, my preconceptions fell to the side and I just “followed my nose.”

You’ve worked in all kinds of settings – as a member of bands, as a solo artist, as a producer for Whiskeytown, Le Tigre, Alejando Escovedo and others. I’m wondering what you’ve learned about group dynamics, that invisible chemistry that make some arrangements of musicians really fruitful and others sort of flat. Any rules of thumb?

Hmm. Musicians lead complicated, demanding lives, but if the music they are making is itself inspiring to them, then optimism and joy follow from this. Musicians are doing what they do because they respond strongly to music. So if I can clear away cobwebs and weeds (in arrangements, lyrics, key choices, tempos, instrumentation), ideally with a minimum of changes, and let the goodness of their music shine forth more clearly, this in itself lifts all our spirits. And then the “chemistry” of the band and the project jells.

One of my private rules, when producing, is “Don’t think you are right, just because you are experienced.” I try to put away my expert mind, to be alert to what might be new and unique about what they are doing, what they are saying. This is hard for me, sometimes, but it’s important to do. I also think of myself as a “music producer” more than as a “record producer.”

It’s amazing how many good and great bands – the backbone of the U.S. alternative and indie-rock movements — have come out of Southern college towns, especially Chapel Hill and Athens. (We can credit Charlottesville, at least in part, for Pavement, as well.) Do you have any hunch why?

I am not sure why. I think that songwriting requires some time alone, and maybe there is more space in the South, the hive is less tightly packed, easier to find solitude? Cheaper rents, older, vibey buildings?

As far as the college part: It’s life cycle — high school days are times when puberty is especially clouding and intoxicating the brain, then in college years those clouds are slowly clearing and a new, strange “adult” landscape appears and has to be deciphered, during a time when a university environment typically encourages inquisitiveness. And music is a way to talk to your peers about what you are finding, post transformation? In the holding tank of the university?

But I really don’t know. In the Preface of my book, I quote Chilton as saying, “Good things come from the provinces,” and there is something to that, apparently.

Scott Timberg's Blog

- Scott Timberg's profile

- 7 followers