Scott Timberg's Blog, page 5

January 22, 2018

Spotify, David Lowery, and the Future of Artists’ Rights

THE conquest of the music industry by a small number of technology companies has continued on schedule, but there has been some resistance by musicians and their advocates. One of the most stalwart has been Camper van Beethoven leader David Lowery, who led a lawsuit against Spotify for royalties.

Much of the push-back from Lowery and fellow travelers like Blake Morgan (in the news for this  ) and the Content Creators Coalition involves streaming and the (often infinitesimal) payment to musicians attached to it. Here’s Lowery on the subject, from a new Billboard piece:

) and the Content Creators Coalition involves streaming and the (often infinitesimal) payment to musicians attached to it. Here’s Lowery on the subject, from a new Billboard piece:

“Streaming is the future of the music business, and I’m not against it — I just want everyone to get paid fairly,” says Lowery, 57. “There could be millions of songs that songwriters weren’t getting paid royalties for, and the future should be better than that.”

Lowery is also convening an artists’ rights conference at the University of Georgia, where he teaches in the music-business program; I wish I could be there.

HERE is an interview, by Free Ride author Rob Levine, with Lowery about the state of the struggle.

January 9, 2018

Oprah, Trump, and The Man Who Saw Them Coming

THERE has been, of course, an enormous amount of talk about Oprah Winfrey since her truly impressive speech at the Golden Globes Sunday night, and some have proposed her as the ideal candidate for the Democrats to pit against President Trump in 2020.

Even with her candidacy far from declared, there has been a substantial reaction against this notion, with many (across the political spectrum) arguing that the nation does not need another billionaire, another political neophyte, another person who ignores and undercuts science, another celebrity, and so on. (The Guardian has a piece, which I find credible, arguing that Winfrey is an apologist for capitalism whose “empowering” stories “hide the role of political, economic and social structures in our lives.”)

In any case, if the next presidential race is a Winfrey-Trump matchup — that is, a campaign between two television start with severely limited political experience — it will further prove that one of the 20th century’s great prophets was media theorist Neil Postman, who predicted this kind of thing more than three d ecades ago. (Postman’s most famous book, Amusing Ourselves to Death, came out in 1985, and was in some ways a response to Reaganism, though his historical context goes back to Plato and Socrates.)

ecades ago. (Postman’s most famous book, Amusing Ourselves to Death, came out in 1985, and was in some ways a response to Reaganism, though his historical context goes back to Plato and Socrates.)

My opening paragraph set up the context of the rise of these kinds of people into political life:

These days, even the kind of educated person who might have once disdained TV and scorned electronic gadgets debates plot turns from “Game of Thrones” and carries an app-laden iPhone. The few left concerned about the effects of the Internet are dismissed as Luddites or killjoys who are on the wrong side of history. A new kind of consensus has shaped up as Steve Jobs becomes the new John Lennon, Amanda Palmer the new Liz Phair, and Elon Musk’s rebel cool graces magazines covers. Conservatives praise Silicon Valley for its entrepreneurial energy; a Democratic president steers millions of dollars of funding to Amazon.

I wrote about the pertinence of Postman’s vision into a 21st century he barely lived to see. (Postman died in 2003.) Here it is — written before the rise of our current president into politics, but, I hope, still relevant to the state that we are in.

January 8, 2018

Britain, Rock n Roll, and 1966

WHAT was the real heart of the ’60s? That depends, of course, on what we really mean when we talk about that much-mythologized and contested decade. The British rock critic and social historian Jon Savage, best known in the States for his chronicle of punk and the Sex Pistols, England’s Dreaming, sees 1966 as the era’s key year, and his book, 1966: The Year the Decade Exploded, just out in paperback, chronicles it all in delicious detail.

Here is my essay on Savage’s book, which was a built out of a long interview with him as well as conversations with a film critic, Michael Sragow, and a writer on black culture and politics, Gene Seymour.

I found Savage to be quite sharp and lively over the phone, if despairing at recent shifts in US and UK politics. (He and I disagree about The Jam and Van Morrison!) Savage also has a book about the making of teenage culture — from the Victorian era to the end of 1945 — that I am eager to read. Overall, it was his skills as a social historian that impressed me the most, and his ability to put things like the Velvet Underground, the Beatles’ Revolver and Dusty Springfield into a historical context.

a social historian that impressed me the most, and his ability to put things like the Velvet Underground, the Beatles’ Revolver and Dusty Springfield into a historical context.

And unlike a lot of folks who lived through the ’60s, he is not nostalgic for the era or its music: While groups like the Kinks and the Yardbirds still matter to him, his favorite recent record, around the time we spoke (this was some months ago) was the latest Frank Ocean. As a writer, he has to look back, he told me, but he tries to stay connected to his inner teenager and also look forward. In any case, check out the book — it’s outstanding.

December 20, 2017

Documenting the Athens Music Scene

ONE of the first things I saw when I moved to Athens, GA, two years ago was a gallery — okay it was the landing of a rock club, the Georgia Theatre — devoted to large, beautifully produced photographs by a guy named Jason Thrasher. Plenty of Athens musical heroes — R.E.M.’s Michael Stipe, for example, and members of the Elephant 6 bands — were here, as well as people I didn’t know. Each shot was distinctive, bringing out the personality of each artist along with, in most cases, his or her private environment.

It gave me a sense of a place that was — and had been — a real cultural community and not just a jumble  of bands.

of bands.

I ended up, as it happens, being introduced to Thrasher that night, and while we mostly kept missing each other over the ensuing year, I was struck by the seriousness of his craft and the wide range of his work.

So I was pleased to hear recently that Thrasher has put together a book chronicling the city’s music scene. As a died-in-the-wool West Coaster who returned to Los Angeles, I’m glad to have the vibrant scene back in Athens documented so well. Here is my conversation with Thrasher about his book, Athens Potluck. The book, which you can read about here, includes an introduction by Patterson Hood of Drive-By Truckers.

Your book has an unusual structure, with each musician suggesting the next one in the book. Whose idea was this, and why did it seem like the natural way to do Athens Potluck?

My wife, Beth Hall Thrasher suggested the idea that the first person select the next person and so on. We had been talking about how to do a book about the Athens music scene for a while and I had been photographing a lot of bands at the time. I didn’t want to do a book of band photos. At least not for my first book and I knew I wanted to photograph individual artist or musicians in their homes but it was this idea that they choose where to go that set me on my path. If I had chosen everyone it might have happened and been another kind of book but with this approach it truly is a community project. The name Athens Potluck refers to the idea that everyone had to bring something to the table and that something was the person they chose.

What’s amazing about the Athens music scene is that it’s ranged, just in a few decades, from the B-52s and R.E.M. to Neutral Milk Hotel and Of Montreal and Elf Power, to Drive-By Truckers and Future Birds and Cicada Rhythm… bands that cover a huge range of styles. What do you think makes the scene in this little city so rich and stylistically varied?

The Athens I know and love is a very small town inside a small southern city. Athens benefit

s from being very close to Atlanta and everything it offers including the largest airport in the world. I have always felt that the art and music made here has an amazing ability to get out into the world. Maybe its this access and as well as the isolation that has created an environment where art and music flourish but also get broadcast to a wide audience.

Beyond that there has to be something in the water or maybe it’s in the PBR. People here are supportive and secretly competitive. Friends inspire and push each other towards our goals constantly.

I know personally from this book that it was a greater effort that just my one-man show. This book was a true community effort. Not only with the 33 musicians that were photographed for the project and to the stories they each wrote for the book. The clubs hosted shows in support of the project and the greater Athens community (far and wide) pre-ordered over 400 books to make this thing happen.

One thing that struck me immediately about your photographs was how comfortable the subjects seemed — like they were able to be themselves, unguarded; this hit me especially with the image of Michael Stipe. Is this something you’re conscious of, and how do you get there?

The main goal when I started this project was to make natural relaxed photographs. I didn’t bring a lot of equipment along for the photos, no flash or strobes were used and mostly I worked with one camera and one lens. I wanted to just hang out and see what would happen. Some of the people in the book I had know for years and others I met the day of the photoshoot. Somewhere great friends and others have become great friends since these photos were made. I’ve know Michael for years but have never done a photo shoot with him but he’s always been very kind and supportive of my photography. He’s a photographer also so I think we talked about cameras and old friends while we worked. He’s a pro and a hero of mine so he knew what he was doing and I tried to make good photos.

knew what he was doing and I tried to make good photos.

I think if you look closely at some of the photos in a few peoples chapters you’ll be us get more comfortable with each other as we spent time together.

The real trick is taking your time and just enjoying the process with the person your photographing. It is a process.

You have an image of Jeremy Ayers, who I never met but who I got the sense was sort of a muse of the scene there and embodied some of what made the city’s culture distinctive. Would you like to say something about him?

Jeremy was everyone’s favorite. I remember very clearly meeting him on the street downtown very shortly after I moved to town. I knew he was special right away. He was really my first friend in Athens. We lost Jeremy a little over a year ago and it kicked this towns ass. It was a huge gut punch to almost everyone I know and love. As we were working on the book we tried to come up with a good way to honor Jeremy. He’s in several of the stories that the musicians wrote for the book. I had photographed Julian Koster at Jeremy’s house when he was living there so when I called Julian to ask him to write a story for the book he told me this amazing story about Jeremy. As soon I we got the final story I realized that it opened up a chance to include Jeremy in Julians’ section. It was one of my favorite parts of the book. I loved and I miss that amazing person.

Besides your shots of musicians, you’ve shot a lot of images of landscape, architecture, etc. I wonder what other photographers — especially photographers of the South like William Eggleston and Walker Evans — have ever been important to you?

Eggleston is King and Evans made me see the beauty of my home state of Alabama. Along the Lee Friedlander, Diane Arbus and Larry Sultan they are my favorite photographers. There’s a nod to Eggleston near the end of the book if you look closely.

What kind of camera/ equipment do you typically use, and why do they seem like the right arsenal for what you do?

I like to keep it simple. This was the first real project for me where I realized what I could do with a digital camera and didn’t wish that it was film. Keep in mind I started this 7 years ago and I gave up film 12 years ago. For the first 5 years I missed it greatly but he with this project I did something that I could have never done with film. At least they way I did it. I started off with a Canon 5D Mark 2 and finished with a Mark 4 and a Sony Mirrorless.

Athens is, like most of the South, rainy, humid, deeply green and overgrown much of the year. How does this shape the way you photograph things, the way colors and light work in your images?

That’s the best part of the South. It effects the light in the best ways and it’s really the reason I’m still here. We get all four seasons but winter is mild (how I like it) and it never really stays the same for too many days in a row. It’s rainy and warm here in Athens right now, just days before Christmas and it very well could be hot tomorrow and then snow by the end of the week.

There’s a thickness to the air and sometimes it actually coats the camera body. I’ve even had my sensor on the camera fog up. I love how this effects the light and the skin and the greenery. When civilization comes to an end, the South will be the first region to be taken back by nature.

December 18, 2017

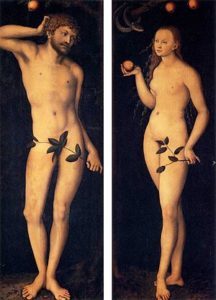

The Afterlife of Adam and Eve

ONE of my favorite books of the year is the effort by Shakespeare scholar Stephen Greenblatt to make sense of several thousand years of Adam and Eve. Where did the original myth and its imagery come from, how did it resonate down the centuries for Christian, Jewish. and Muslim believers, for philosophers and theologians, and for poets like John Milton and artists like Durer?

Greenblatt tells the tale in a way that’s both lively and smart, and my interview with him for The Los Angeles Review of Books is here. For most of the conversation, we talk about these two and the infamous serpent, but near the end we get into New Historicism — the discipline he helped found — and his habit of writing books that mass audiences actually want to read. Here’s a taste:

You’ve obviously had some success writing for a general audience, atypical for an academic. I wonder where you think you learned to write — or to write like this, setting scenes, using metaphors, establishing characters, and so on … I was wondering where that comes from, because that’s not built into the training of a literary or historical scholar.

They try to beat it out of you! It’s probably that I wasn’t willing, somehow … I wasn’t trained adequately — they didn’t beat it out of me. They tried, but they didn’t. And I remember writing the first sentence of my dissertation a thousand years ago, and going out in the hallway and saying to a friend of mine who was there, “I’ve written the first sentence of my dissertation,” and he looked not particularly thrilled. Then I said, “I’m going to read it to you!” I can even remember it: “Sir Henry Yelverton, the king’s attorney, was no friend to Sir Walter Raleigh,” and my friend looked a little quizzical. I said, “The thing is, you don’t know whether you’re reading a dissertation, or a novel, or…”

December 6, 2017

The Murder of the LA Weekly

SOUTHERN Californians have been bludgeoned with bad news lately, as a number of media outlets — LAist, BuzzFeed, Los Angeles magazine, the LA Times, and the OC Weekly — have either shut down or seen major layoffs. (In Orange County, editor Gustavo Arellano resigned after being asked to machine-gun his staff.)

Perhaps the most disturbing of these is the fresh murder of the LA Weekly, which has weathered a number of abrupt shifts in the past but now seems to be truly dead. The entire genre of alternative weeklies has had a tough run since the Recession and digital revolution — I wrote about the death of the Boston Phoenix and struggles of the Village Voice here in 2013. The Weekly was run by the former New Times company of Arizona, who are hardly paragons of virtue. But this is a whole new level of hell.

In parallel with the way rich right-wing men like Robert Mercer, Sheldon Adelson and the Koch Bros have — often invisibly — distorted our national politics with huge contributions and bogus foundations, especially post-Citizens United — the Weekly’s new owners snuck up on us. This group created a new company, told a number of half-truths, then came in, busting a union and firing nearly the paper’s whole staff. This group of Libertarian jackals has also hinted that they will no longer pay writers for their “contributions.” The Don’t Work For Free movement has never seemed so relevant.

This Pacific Standard story is the fullest recounting I’ve seen so far. (KCRW Press Play’s interview with new boss Brian Calle, former editor of the OC Register’s famously Right-Libertarian editorial page, is also worth hearing if you have a strong stomach for evasion, duplicity, and intellectual shallowness.) The paper’s former film critic, April Wolfe, has been leading much of the opposition among former employees of the Weekly, a paper that got a big early boost in its coverage of underground rock music, gay culture, and LA’s air pollution.

More recently, the paper has been focused on telling the stories of L.A.’s marginalized communities. “I came in with the express intent of raising the profile of women and people of color in our film section, and we did that,” Wolfe says.

“We were reporting on Boyle Heights, communities south of the 10, in the San Fernando Valley, Creative communities that are mostly people of color,” says former managing editor Drew Tewksbury (who on Sunday won a Los Angeles Press Club award for a piece on a queer performance artist of Mexican descent). “I’m bummed I lost my job, I loved it, but I’m more bummed for the communities.”

… in the week since the staff was laid off, only a handful of articles were published, the majority of which the former editors told me had been pre-scheduled. One post, published by contributing writer Keith Plocek on Wednesday evening following the firings, is still active on the site. Keith writes: “The new owners of L.A. Weekly [sic] don’t want you to know who they are. They are hiding from you. They’ve got big black bags with question marks covering their big bald heads.”

The new owners’ backgrounds notwithstanding, there has been little evidence of a political shift at LA Weekly during the first week under Calle and co. Instead, the shift has, at least initially, been one toward incompetence and ignorance.

The whole story — with its description of the slithering secrecy of this new crew, is worth reading in its entirety.

Deadlines, I’m afraid, keep me from saying more, but this saddens me and many others quite deeply. When I moved to town 20 years ago, the weekly was a feisty and intelligent paper, thick with adds, sometimes up around 200 pages, with the best food, film, and arts writing in the city. (I say this as someone who worked for the rival paper, whose owners later swallowed the Weekly.) I ended up marrying a longtime music contributor, and we still have many friends from several generations of the paper’s existence.

To see it crushed by smug, wealthy offspring of Ayn Rand (are there any other kind?) who want their writers to work for free is pretty close to stomach-turning.

LA saxophonist Danny Janklow at The Blue Whale

FOR the last few years, much of the attention to the resurgent Los Angeles jazz scene has gone to Kamasi Washington, a titan of a tenor saxophonist who I had the pleasure to see at the Hollywood Bowl over the summer. His communal, late-Coltrane, South Central approach to the jazz tradition is for real, powerful, even — a word I try to avoid — inspiring.

But there is more to the revived LA scene than Washington, and the non superstar players are the ones who really give a music community its dimension. There are surely others, but to my casual acquaintance, a whole other level of fine players with strong live presences include drummer Matt Mayhall, bassist Miles Mosley, and guitarist Jeff Parker. And, alto sax Danny Janklow, who I saw a few nights ago at the Blue Whale.

Janklow’s show was the record-release party for his new LP, Elevation. He’s a friendly and appealing leader onstage, and commanded an exceedingly good band. This is what we used to call (do people still use this term?) “straight-ahead” jazz, with just a touch of ’60s avant-gardeism and a few forays into funk. (The group included a vibraphonist and the bassist put down his upright for a song or two to groove on what i think was a Fender.) As strong and locked in as this crew was, the highlight was guest pianist Eric Reed, perhaps still best know for his work with Wynton. Swinging, lyrical, forceful — it was a real pleasure to see him solo.

Janklow himself seems to me in the Cannonball Adderley school — bluesy, melodic, supple — with at times the instincts of a late-period Art Pepper. That is, he often starts out with a brief, singable melody and then builds his songs to big, expressive emotional climaxes.

Apparent’y I’m a bit late to Janklow’s work — the show as packed, and it was not all brooding bespectacled white men like yours truly. This is a crowd I rarely saw when I used to go to the old Jazz Bakery.

A young native of the Valley, schooled in the jazz crucible of Philadelphia, who returned home, Janklow appears to have a bright future. My hope is that this charismatic and open-eared performer will sustain his best qualities while developing a more distinctive voice on the saxophonist. Janklow is still in his late 20s — I look forward to what he comes up with next.

December 1, 2017

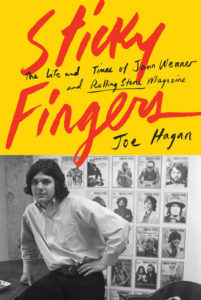

Rolling Stone, Music Journalism, and the Baby Boom

LIKE a lot of people I know, I’ve just finished the biography of Rolling Stone founder Jann Wenner. Sticky Fingers is more than just the story of one man, though it gets close to its subject: It’s a real cultural history of English and American music, of American magazines, of pop culture in general, and a shadow biography of what I call Boomer Triumphalism.

Wenner, as you may’ve heard, does not come across terribly well in here: He manages to betray or lie to just about every friend of professional associate, and comes across, often, as a manic, social-climbing, coked-up rich boy. Some from the early days of Stone have challenged the emphasis (though not the facts) of the telling, including the formidable rock critic Greil Marcus. (The book started out as a friendly project, pitched by Wenner himself, that became less friendly.)

Others find Wenner so distasteful they have told me they are not interested in the book. That he shifted English pop culture is undeniable. What are it causes and consequences?

I corresponded with author Joe Hagan about Sticky Fingers and the half-century it chronicled.

Let’s start with Wenner’s achievement. How was our world — at least, the world of music, media, and pop culture — changed by him? How big an impact did Wenner exert at shaping the way people in the English-speaking world see their culture?

Without overstating it too much, I think Jann shaped how people thought about the 1960s, and specifically the rock and roll culture that emanated from that era. His key insight of 1967 was that rock was a whole worldview that valued personal freedom and social progress. But he also had a hand in shaping how people viewed rock stars themselves, how they should look and behave and present themselves in the media. The cover of Rolling Stone was, for several decades, a kind of stylebook of rock stardom, which involved confession, shock and sexuality, the de facto virtues of youth rebellion. And Rolling Stone gave rock stars credibility as social commentators and critics, something that was unthinkable before Rolling Stone.

I got tired after a while of writing “Conflict !” in the margins of your book for all the dodgy ethical/ journalistic calls Wenner made, most obviously his allowing musicians to edit their own interviews. What were his most serious breaches, and on balance, how substantial a departure from professional journalistic standards do they seem?

In the beginning, RS was more like a trade magazine, a booster for the rock world, and less an organ of journalistic grit. Wenner understood that certain elements of the mid-60s teen magazine world were successful, including working hand in glove with the rock stars themselves. Even after RS ramped up its reputation with coverage of Altamont or the Charles Manson murders, Wenner still maintained that boosterism (letting rockers edit their own interviews) because it was good for business. When it comes to the kind of activist journalism he espoused, Wenner’s philosophy was basically that you piss outside your tent, not in it. For him, a record review didn’t fall under the protocols of the Columbia Journalism School.

Then there was the New Journalism era, known as much for stretching the old protocols of journalism as it was for serious reportage. Joe Eszterhas admitted to Playboy in the 1990s that he made up dialog in some RS stories and people constantly questioned Hunter S. Thompson’s work, wondering how much of it was made up. Jann Wenner was fundamentally a risk taker and he took risks on writers. Rolling Stone was sued for libel in 1976 for $100 million and ended up paying a fine and publishing a retraction, but that was an anomaly and Wenner learned from it.

On whole, I’d say RS’s journalism outweighed its boosterism and occasional backscratching. For Wenner, letting his idols control their own stories (or adding an extra star to a Mick Jagger solo album) was a small thing compared to the serious work he published. Obviously this all fell apart with the UVA rape story, which not only hurt their reputation but exposed the brittleness of the magazine as a whole.

Wenner has spent his life engaged with music, and musicians, but I still wonder: What is this guy’s taste like? He loves the Stones and Dylan, but who doesn’t? And he seems to think Steve Miller and Boz Scaggs and Billy Joel and eventually The Eagles are right there behind them. Does he just like — as one of his defrocked writers once charged — whatever sells?

It’s not just whatever sells. Jann always hated KISS, who sold a lot of records, and he never put Steve Miller on the cover of RS, because he personally disliked him. Jann liked the Big Three — Dylan, Beatles, Stones— and he likes California bands of the kind that defined his own success and his own era. His tastes didn’t evolve much past 1977. He is fundamentally a commercial nostalgist. And he likes bands who seem to be an homage to those same bands, like Lenny Kravitz or Kid Rock (who he genuinely likes). He came around to U2 a few years into their popularity, but he came around hard. (Bono was among those who got to edit his own interview.) Bruce Springsteen is a rather late breaking enthusiasm that he developed after Bruce paid him a visit in Sun Valley, Idaho several years ago. Certainly Jann’s access to Bruce added to the appeal. But let me add: Jann’s tastes, as middle of the road as they were, gave him a good sense of his average reader, who wasn’t a critic but more a mainstream fan. He understood the appeal of the main pantheon of rock stars who roamed the earth for decades.

Often reading your book I tried to find a brilliant decision —a nose for talent, a strategic masterstroke, an unorthodox move that nobody else could have come up with — but mostly kept looking. And yet the number of magazines and cultural ventures that spun out after a year or a decade are legion, while Wenner kept going. despite the coke and bad decisions and ego overload. Wenner clearly had the right idea at the right time, and rode the wave of an expanding postwar economy and music business, but was he a genius — as an editor, businessman, politician — or was he just rich and lucky and born the right year?

He was definitely lucky — he told me that himself when I first asked him about the key to his success — but his primary talent was a) being an adept social climber who inserted himself wherever the culture action was, which made him a natural bellwether for what was happening, and b) identifying talented people. That’s no small thing. As I write in the book, he recognized ambition that rhymed with his own and gave writers and photographers and designers freedom to experiment and pursue their obsessions. When it worked out, it was  often a huge deal — especially in the 1970s. I think this is especially true of Annie Leibovitz. In the end, Wenner became a kind of diplomat for a successful generation of rock stars who became their own industry. He excelled at that.

often a huge deal — especially in the 1970s. I think this is especially true of Annie Leibovitz. In the end, Wenner became a kind of diplomat for a successful generation of rock stars who became their own industry. He excelled at that.

I think that like me you are a Gen Xer who came of age after many of the great ‘60s heroes had either broken up, OD’ed, or become rich/ boring celebrities, and after the Baby Boom had woven its own youth into eternal myth. To what extent is your book a quintessential Boomer’s story, with Wenner seeking to make his generation’s heroes the Universal Gods, moving from campus protestor to suspenders-wearing plutocrat, ending as a sort of pop-culture version of Donald Trump?

I think it’s the story of the last 50 years in America — the prime years of the boomers, certainly, but the prime years for all of us, whether we liked it or not. Because we have lived in the boomer shadow for a long, long time. Their money and influence and self-involvement shaped music, film, politics—even the underground culture that emerged to counter it, whether punk or grunge. Jann’s story defined a lot of that narrative—indeed, I often call him the “id” of the baby boom because his personal story, and the story of RS, hews so closely to the generational story. That story is essentially ending right now. Jann did not predict that his 50-year anniversary would mark an ending, but here we are.

After years of working on the book, what seems like a Herculean number of interviews and a very heavy amount of research, how do you view Wenner and his body of work, such as it is? How do you think of him, his magazine, the rock and pop and celebrity establishment he leaves us with?

I think of him as a kind of Greek parable of his age. And the establishment that was left us is now being toppled and rebuilt in the image of a more racially plural and fast-moving generation—partly in response to the old generation’s last brittle totem, Donald Trump.

Some charge that the book was a hit job, that you went out to make Wenner and Jane [Wenner] look bad, to emphasize bad connotations and ignore good ones. Have you heard this yourself, and why do you think this notion has spread?

Obviously I strongly disagree that the book is a “hit job.” It’s unvarnished, sure, but not unfair. I understand that a lot of people’s careers were made by Jann and certainly there are those who share his reverent and nostalgic view of the past, especially at the 50 year mark. I don’t begrudge them their hurt feelings or critical reviews, though I seriously doubt that Greil Marcus read the book beyond the index. I think the book makes a strong case for Jann’s editorial genius and overall legacy. And most independent critics have observed that.

November 24, 2017

The Literary Roots of Lou Reed

Back in the spring, when I pitched the Los Angeles Review of Books on a regular column on musicians and their literary interests, my editor immediately came up with the title All the Poets. The phrase, of course, comes from the Velvet Underground song “Sweet Jane.”

So it seems somehow symmetrical that the latest installment of this feature is a conversation about Lou Reed, VU’s founder, with the man’s biographer, longtime music journalist Anthony DeCurtis. (My editor, Boris Dralyuk, and I are calling this the first posthumous All the Poets — Reed died in 2013.)

Reed, of course, was directly inspired by literature, especially writers of the down-and-out like Genet and Hubert Selby; the poet Delmore Schwartz was his first important mentor. Though the book, and our conversation, ranges widely, DeCurtis is sensitive to this side of Reed: He earned a doctorate in American literature and has taught it in a number of places (including Emory in Atlanta, which put him in striking distance of a young Athens band called R.E.M.) I knew DeCurtis’s writing from Rolling Stone, but then came across his name again in criticism and interviews of Don DeLillo, in the early ’90s perhaps my favorite living American writer.

“You know, Lou cared a lot about music, obviously, cared a lot about sound, but his deepest impulses, I think, were literary,” DeCurtis told me, “and that’s probably true of me as well, in terms of my background, and I think he recognized that.”

In any case here is out conversation about Reed, his roots, and his influence.

November 9, 2017

Arts Funding, US vs. UK, and Chamber Music

ONE of the key issues which underlies this blog and the book which inspired it is the role of public funding in the arts. I hate to give the end away, but one of the concluding points of Culture Crash is the need for more funding in the US, and something closer to a British or European model. (This is hardly an unpopular opinion among my colleagues.)

Similarly, I am skeptical though not opposed to the entrepreneurial spirit in the arts — that is, I often like the kind of specialized and niche-driven groups and series that the market makes possible, but view the whole cultural mix as an ecology. And these private/ entrepreneurial efforts often draw from publicly funded halls, grants, tax-breaks, and the public arts education of both players and audiences. So we can’t neglect the larger arts infrastructure, in the same way a forest needs light, clean water, healthy topsoil, and the right amount of shade to get a rich blend of flora and fauna.

And any reader of this blog knows I consider cultural journalism a crucial piece of the puzzle; and the disappearance of arts coverage aimed at a general audience is a tragedy comparable to the disappearance of arts and music education from public schools.

But this blog, and this post, is not simply about my ideas but a forum and discussion of where culture has been and where it’s going. And while I don’t entirely agree with Adrian Spence, founder of a well-regarded chamber group which has lasted three decades, I take his point of view seriously enough that I’ll follow up here with an answer of his that tripped me up both when he mentioned it over coffee a few weeks ago as well as when he included it in our recent correspondence. (I have removed a surname to keep from making this personal.)

So, here goes:

You say what you’ve done here would be less possible in Europe or the UK. Why does the US seem like the better spot for Camerata, despite the much broader and deeper arts funding over there? Or is it something about the audiences and musical taste in the US that makes a group like yours a better fit?

Ah, a little push back from one of your readers. Excellent. How exciting to actually have a debate about the ARTS!

In form of a preface, I have always found it absolutely astonishing that this wonderful country, my adopted home, shows so little national pride in its arts community; a community that has generated leading, form-changing, artists for well over a century. Does the statistic still hold true that this country spends more on military bands than the NEA? An even greater tragedy is the lack of arts education in schools. Well documented science demonstrates the substantial benefits of musical/instrumental instruction on a child’s cognitive development. That is not just an arts issue but nigh on a human rights issue, that these benefits are deliberately withheld from our youngest citizens.

Here that all is beyond my remit. Scott asked about my Scots/Irish background whence the rest of this has sprung.

I can state categorically I could not have started Camerata Pacifica in Northern Ireland or the U.K. in the late 80s. Back then the notion of an unknown, working class, 25 year old starting what would become a well regarded chamber group would have been seen as preposterous. The still quite pronounced social stratification in the U.K. was also contributory. My ideas would not have been received well and certainly I could not have obtained the seed funding. Perhaps much has changed in the intervening decades, but generally I don’t see it. Not only would it be difficult to sustain a $1,000,000+ budget on whatever small government funding was available, but the musical hierarchy is much more rigid — less so now I think, but still difficult — it is hard to break longstanding traditions. 30 years ago the U.S. offered the American Dream. It promised reward for innovative thinking and I deliberately choose to leave the more closed environment of 1980s Britain.

My intention was never to launch a symphony orchestra or opera house suitable to a capital city. Those institutional pillars of the arts are vital to cities and countries, but there should also be a constant boil of invention and exploration. I became part of a movement in which musicians wrested back control of their, and the greater, musical destiny. I don’t think it is any less than that, and I don’t see how that can happen via an arts council application process.

A healthy arts environment, any business environment, requires the encouragement of innovation and start ups. In classical music today we’re witnessing, in the U.S., Europe and beyond, incredible fertility in that regard, which is driving the renaissance. In any country this will be driven by individual entrepreneurship and funding, not the bureaucracy. Say indeed UK arts councils do have incubator programs to encourage the formation of new ensembles; along comes a recession, arts budgets are slashed, grants withdrawn and groups disappear. That happened. Scott, perhaps a little investigative journalism can precisely determine the extent of it, but in the last decade that happened. Without investment from individuals those groups had nothing once government funds evaporated.

The first sentence of Camerata Pacifica’s mission statement states we exist, “to affect positively how people experience live performances of classical music.”

Are we touching people? Have we affected positively, have we changed, their experience of classical music? Over 28 years I can say we have. Part of that is a result of how this country’s citizens interact with non-profits of all sorts in their communities. Personal investment is key, financial, emotional and otherwise, which I simply do not witness occurs to the same degree in the U.K. or Europe.

Permit me to directly address Mr. [name deleted]’s under informed view of the arts scene in Los Angeles. At best it’s dated or he’s Wikipedia-bound. Certainly he has access to an abundance of statistics and we know what Mark Twain had to say about that ☺

Camerata Pacifica’s Adrian Spence, w flute

I don’t understand the point being made behind those data he presents. Is it that L.A. would be better served than London if it had 6 orchestras? Off the top of my head in L.A. I can think of: Jacaranda, Da Camera Society, LA Chamber Orchestra, Musica Angelica, Wild Up, The Industry, Salastina, Pittance Chamber Players, Kaleidoscope, PianoSpheres, Colburn Chamber, Salon de Musique, plus all the regional orchestras and operas. I could go on, and Scott I’m sure you know many more than I, but our population doesn’t seem starved for music. Indeed, it seems like a pretty healthy situation to me.

On NPR last week I heard that, per capita, the U.S. has 5 times more mall space than the U.K. Most of empty; desperately seeking retailers and consumers. It’s overbuilt. The number of orchestras in a town tells us nothing, especially if they are primarily state supported. Show me the hard data concerning subscription & ticket sales. Not student outreach tickets or other discounted offers. Not one time sales, which reveal a recruit who didn’t like what was offered and didn’t return. Retention is the most important data point. Year upon year Camerata Pacifica’s subscription sales are up. People come, they stay and, due not in small part to this American model, they become donors and a happy, invested part of a shared, musically inquisitive community.

Camerata Pacifica’s Santa Barbara and Ventura venues sell out regularly. A beautiful new hall at The Huntington has almost doubled our capacity there, and our youngest, largest venue, Zipper Hall in the Colburn School, has plenty of seat availability. In other words, subscription growth will continue. When all of the venues are sold out? It’s chamber music, we’ll add another. The model is sustainable. However, eliminate government funding from any of the European groups, (and in the age of austerity who can say that won’t occur), what’s going to happen?

One can endlessly argue the merits and flaws of each system, and there are many. I’ll leave it to others to continue that debate. For Camerata Pacifica however, pursuing the mission it does at the beginning of the 21st century, this model of personal investment is the most effective, durable and rewarding to all involved.

Scott Timberg's Blog

- Scott Timberg's profile

- 7 followers