Jennifer Bohnhoff's Blog, page 21

December 29, 2021

A New Beginning for an Old Book

A still shot taken from the commercial I was watching TV this holiday season (something I don't do very often) and a commercial for a new TV movie caught my eye. It began with a shot of a glacier that was all blues, grays, and whites. It looked very familiar.

A still shot taken from the commercial I was watching TV this holiday season (something I don't do very often) and a commercial for a new TV movie caught my eye. It began with a shot of a glacier that was all blues, grays, and whites. It looked very familiar.The movie is a SciFi drama about a man who replaces himself with a carbon copy clone.to protect his family from loss after he's diagnosed with a terminal illness. Not a familiar scenario for me at all.

But then I saw the title: Swan Song , and found it too familiar for comfort. I've got a novel with the same name. The picture on the cover is too close to the image from the commercial.

One cannot copyright titles. I could write the Bible, or Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire and get away with it. In fact, there are many books, musical CDs and movies titled Swan Song. They range in subject matter from the story of a retired hairdresser who escapes from a nursing home to give a former client her final hairdo, to opera singers in Nazi Germany, to Welsh boys saving wildlife habitat. Nearly all are about death, or the end of a culture, playing on the old myth that swans sing most beautifully before they die.

One cannot copyright titles. I could write the Bible, or Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire and get away with it. In fact, there are many books, musical CDs and movies titled Swan Song. They range in subject matter from the story of a retired hairdresser who escapes from a nursing home to give a former client her final hairdo, to opera singers in Nazi Germany, to Welsh boys saving wildlife habitat. Nearly all are about death, or the end of a culture, playing on the old myth that swans sing most beautifully before they die. So while I could not be angry at the title and image, I could worry that people who'd watched the move would think my book was related, buy it and be disappointed.

I decided the best thing to do was change the title and cover of my novel. I have now pulled the old version from Amazon. I have six copies that I will sell at a reduced price. On January 12, the new version will become available to purchase in ebook format. You can preorder it now here, and it will automatically show up on your reading device on January 12. I will roll out a new paperback sometime in the next month. The new version is entitled The Last Song of the Swan . It's currently available for preorder. I will reveal the cover soon, too, first to my email list, then on social media, and finally on my website. People on my email list will also have the opportunity to download the book for free.

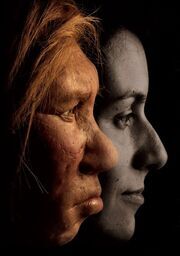

My novel is a dual narrative story, which means it has two different narrators. One is Helen Bowie, a modern high school senior who has to read Beowulf in her English class. When she reads that Grendel, the monster in Beowulf is a fallen son of Cain, she begins to wonder what kind of monster that makes him. Helen is also the kind of girl who champions the underdog, so when a new student arrives at school and is immediately ostrasized because he looks like the images of Middle Eastern terrorists that show up on the news, she's compelled to champion him and prove to the student body that the new boy is no monster.

My novel is a dual narrative story, which means it has two different narrators. One is Helen Bowie, a modern high school senior who has to read Beowulf in her English class. When she reads that Grendel, the monster in Beowulf is a fallen son of Cain, she begins to wonder what kind of monster that makes him. Helen is also the kind of girl who champions the underdog, so when a new student arrives at school and is immediately ostrasized because he looks like the images of Middle Eastern terrorists that show up on the news, she's compelled to champion him and prove to the student body that the new boy is no monster.

The other narrator is Hrunting, a girl whose world is changed when a hero arrives and challenges the relationship between her clan and another local group of people who are different from them. Like Helen, Hrunting tries to champion her neighbors and convince everyone that they are not monsters just because they look and act differently.

The other narrator is Hrunting, a girl whose world is changed when a hero arrives and challenges the relationship between her clan and another local group of people who are different from them. Like Helen, Hrunting tries to champion her neighbors and convince everyone that they are not monsters just because they look and act differently.The Last Song of the Swan is not an easy book. It's written to make the reader think about the origins of prejudice and exclusion and what we can do about it. This novel doesn't end happily, with all the bad guys thwarted. How could it in a world that is even more divided now than ever before? I am hoping that giving it a new title and a new cover will help this book. I think it has a big job to do.

Jennifer Bohnhoff lives and writes in the mountains of central New Mexico. You can read more about her and her books here, at her website.

Jennifer Bohnhoff lives and writes in the mountains of central New Mexico. You can read more about her and her books here, at her website.

Published on December 29, 2021 12:57

December 21, 2021

Book Review: Christmas Cookies at the Cat Café

Christmas Cookies at the Cat Cafe is a sweet romance about a widow who's feeling like she's come to a crossroads in her life and needs to make a fresh start. Diane is the not-so-old matriarch of a family of women who have started a cafe that partners with a local cat shelter. Over the past year, the daughters have established their business, become important members of their community, and found love. Now that they're established, it's Diane's turn to find a new course for her life. It's been two years since her husband's death. Is she ready to rekindle an old flame?

Christmas Cookies at the Cat Cafe is a sweet romance about a widow who's feeling like she's come to a crossroads in her life and needs to make a fresh start. Diane is the not-so-old matriarch of a family of women who have started a cafe that partners with a local cat shelter. Over the past year, the daughters have established their business, become important members of their community, and found love. Now that they're established, it's Diane's turn to find a new course for her life. It's been two years since her husband's death. Is she ready to rekindle an old flame?This story takes place at Christmas, so it's a perfect book to snuggle up with during the holiday season. It's a sweet romance, which means there's nothing more explicit than snuggling and short kisses, which means that it's a book that could be left out without scandalizing young readers. If it's too late in the season for you to pick up a new book now, you're in luck. Christmas Cookies at the Cat Cafe is one of a series of books all set at the Cate Cafe. Each book in The Furrever Friends Sweet Romance series focuses on a different worker or customer at a small-town cat café. Each book is a complete story with a happy ending for one couple, and at least one forever home found for a rescued cat. While there is a definite order to the books, all are well written enough that they could be read as a stand alone, or out of order.

What I love best about this entire series is that the characters are all real, genuine people, and they're all trying hard to be good people who are kind to each other and active in their community. Family is important to all of them, as are healthy relationships. I don't think there's a single character in these books that I wouldn't want to have to dinner in my own house. In a world where violence and greed are common, it's nice to read about nice people.

Jennifer Bohnhoff lives in the mountains of central New Mexico. She is a writer and blogger, and you can read more about her and her books here.

Published on December 21, 2021 23:00

December 18, 2021

New visitors at an old Scene

I bought my creche about 25 years ago from a department store that no longer exists. It was the week after Christmas and I got it for 70% off. It was one of the best investments I've ever made.

I bought my creche about 25 years ago from a department store that no longer exists. It was the week after Christmas and I got it for 70% off. It was one of the best investments I've ever made. The figures in my creche are made out of some kind of rubberized material that bounces when dropped. That's a good thing, because all of the figures have been dropped a lot. I've always kept it on a low table, so whatever children come over can play with it.

Before we had this creche, we had an inexpensive one that my mother-in-law had bought for her mother when she was in a nursing home. The figures in that set were made from plaster of paris. I had glued heads on so often that they all looked as hunchbacked as Richard III in a bad production of the play. Or Marty Feldman in Young Frankenstein. Reglued plaster doesn't take well to retouching with paint, either, giving them a rather leperous appearance.

The year after the 9/11 attack, a sniper showed up on the roof of the stable. He was a green plastic army man who lay flat on his stomach, his gun pointing forward as he protected the baby Jesus. It's not unusual for the Army to reassign soldiers. The sniper must have been stationed elsewhere, because he eventually disappeared. Now, two infantry men are covering roof-top security.

The year after the 9/11 attack, a sniper showed up on the roof of the stable. He was a green plastic army man who lay flat on his stomach, his gun pointing forward as he protected the baby Jesus. It's not unusual for the Army to reassign soldiers. The sniper must have been stationed elsewhere, because he eventually disappeared. Now, two infantry men are covering roof-top security.

In 2017 my husband and I moved out of the city, and I began teaching at a rural school. Many of my students lived on ranches and worked with livestock. I don't think any of them had anything to do with the cowboy who showed up in the stable soon after, but it did seem appropriate to have someone there to look after the livestock and keep them from lowing all night.

In 2017 my husband and I moved out of the city, and I began teaching at a rural school. Many of my students lived on ranches and worked with livestock. I don't think any of them had anything to do with the cowboy who showed up in the stable soon after, but it did seem appropriate to have someone there to look after the livestock and keep them from lowing all night. The COVID scare has kept children away from the manger scene now for the last two years. I am hoping that this Christmas will see small hands holding these figures once again, and we will have the opportunity to talk about who all these figures are and why Jesus is the central figure. Maybe, when I pack this display up sometime after January 6, I will have a new figure or two to put away. Everyone is always welcome at the creche.

Wishing you and yours a blessed Christmas.

Published on December 18, 2021 23:00

December 11, 2021

Pfeffernüsse and the Deutschamerikaner

Pfeffernüsse is German for pepper nuts. They are small spice cookies that are popular holiday treats in Germany. I remember the pfeffernüsse my grandmother made being little, hard rock-like cookies that were sweet and spicy but as inedible as an unshelled walnut unless they were dipped in milk or, better yet, hot tea.

Pfeffernüsse is German for pepper nuts. They are small spice cookies that are popular holiday treats in Germany. I remember the pfeffernüsse my grandmother made being little, hard rock-like cookies that were sweet and spicy but as inedible as an unshelled walnut unless they were dipped in milk or, better yet, hot tea. My grandmother was a true Deutschamerikaner. She was born in Nebraska, but her parents had come from Saxony. Her birth certificate was in German, and she didn't learn to speak English until she went to school. I, on the other hand, am of French, Norwegian, Swedish, German, English and Irish ancestry. I can ask for a pitcher of beer or water and thank the person who brings it. That's the extent of my German. When I married into another thoroughly American family with deep German roots, I was told that my pfeffernüsse was not real pfeffernüsse. I still don't know if the differences were because of different family traditions, or if they were regional, but my husband's grandmother, whose roots were in what became Eastern Germany during the Cold War, made a very different cookie than my Saxon grandmother. Apparently they don't eat rocks east of Berlin like they do in the south. Or, maybe my grandmother was just not much of a cook. She died when I was six, and at an age when I adored her. Even her cooking.

This recipe is the one I married into, not the one I was born into. I hope you enjoy it.

Pfeffernüsse Mix well:

1/2 cup butter

1 cup sugar

Add and beat until smooth:

1/2 cup water

1/2 cup dark molasses

1 tsp oil of anise (see note below)

Sift together, then stir into liquid ingredients. Dough will be stiff

4 cups flour

1 tsp. soda

1 tsp. ginger

1 tsp. cinnamon

1/4 tsp salt

1/2 tsp fine grind black pepper

Roll dough into small balls. Use a bit of flour on your hands if it gets sticky.

Bake at 375 for 10-12 minutes.

Cool cookies on a rack, then put in a bag with 1/4 cup powdered sugar and shake until they are well coated.

note: My mother-in-law gave me a small vial of oil of anise for my first Christmas as a Bohnhoff. When it was gone (years later!) I found it hard to replace. Some years I've found Anise extract, which is almost as good. Other years, I've put a tsp. of Anise seeds in a blender with the sugar and pulverized them.

Some Famous German Americans German Americans, or Deutschamerikaner are citizens of the United States who are of German ancestry. They are the largest ethnic group in the United States, accounting for 17% of the U.S. population.

The Deutschamerikaner have been here a long time, first arriving in New York and Pennsylvania in significant numbers in the 1680s. In the sixty years between 1840 and 1900, Germans were the largest immigrant group, outnumbering even the Irish and English. Here are a few Deutschamerikaners who have made their name in America:

Thomas Nast was born in Bavaria, but moved to the United States as a young boy. A political cartoonist, he is credited with making the elephant the political symbol of the Republican party. Although often given credit for it, he did not create Uncle Sam, Columbia (the female personification of America) or the Democratic donkey. The modern version of Santa Claus came from his drawings, which were based on the traditional German Sankt Nikolaus.

Thomas Nast was born in Bavaria, but moved to the United States as a young boy. A political cartoonist, he is credited with making the elephant the political symbol of the Republican party. Although often given credit for it, he did not create Uncle Sam, Columbia (the female personification of America) or the Democratic donkey. The modern version of Santa Claus came from his drawings, which were based on the traditional German Sankt Nikolaus.

Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler, better known as Hedy Lamarr, was born in Austria. In 1933, she fled from her husband, a wealthy Austrian ammunition manufacturer. In London, she met Louis B. Mayer, the head of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, who persuaded her to move to the United States. In addition to becoming a major film star, Lamarr was also an inventor. She developed a radio guidance system for Allied torpedoes that used spread spectrum and frequency hopping technology to defeat the threat of jamming by the Axis powers during World War II. The principles of this work is still used in Bluetooth and GPS technology, and led to her induction into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2014.

Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler, better known as Hedy Lamarr, was born in Austria. In 1933, she fled from her husband, a wealthy Austrian ammunition manufacturer. In London, she met Louis B. Mayer, the head of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, who persuaded her to move to the United States. In addition to becoming a major film star, Lamarr was also an inventor. She developed a radio guidance system for Allied torpedoes that used spread spectrum and frequency hopping technology to defeat the threat of jamming by the Axis powers during World War II. The principles of this work is still used in Bluetooth and GPS technology, and led to her induction into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2014.

Theodor Seuss Geisel, better known as Dr. Seuss, may be best known for writing and illustrating more than 60 books for children, but he was also a political cartoonist, poet, animator, and filmmaker. His children's books have sold over 600 million copies and have been translated into more than 20 languages An author who lives in New Mexico, Jennifer Bohnhoff writes about cookies, history, and her book on Thin Air, her blog.

Theodor Seuss Geisel, better known as Dr. Seuss, may be best known for writing and illustrating more than 60 books for children, but he was also a political cartoonist, poet, animator, and filmmaker. His children's books have sold over 600 million copies and have been translated into more than 20 languages An author who lives in New Mexico, Jennifer Bohnhoff writes about cookies, history, and her book on Thin Air, her blog.

Published on December 11, 2021 23:00

December 4, 2021

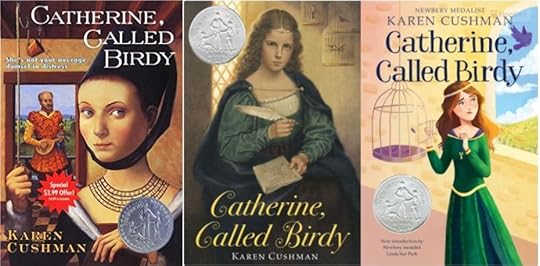

Changing Covers

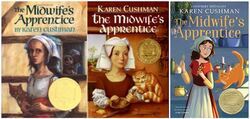

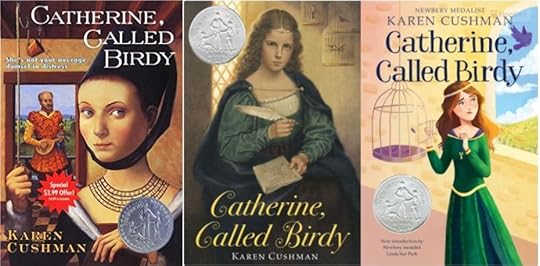

Publishing houses and self published authors sometimes change the covers on their books. Many do so to keep up with changing trends in the book marketplace. As reader tastes change, so do book covers. Below are some examples of different covers for award winning books by Karen Cushman, and a brief synopsis of each book to help you analyze the cover.  Catherine, Called Birdy is a novel written as a diary. It begins in September 1290, with Catherine describing her father's manor, her parents, and the world she lives in. Her father wishes her to marry someone who will make advantageous social connections, but all the suitors he brings fall short of Birdy's ideal. Finally, Catherine's father demands her to marry an old, repulsive man whom she calls "Shaggy Beard." She refuses, and devises many scenarios to escape. As the day for Catherine's official betrothal approaches, she realizes that she herself will be the same no matter who she marries. However, Shaggy Beard dies and she is pleased to become engaged to his clean, young, educated son. The Midwife's Apprentice tells the story of a homeless, nameless orphan girl. Called Brat, the only name she can remember anyone calling her, she sleeps in dung heaps to keep warm until a harsh and uncaring midwife named Jane Sharp takes her in as an apprentice. She takes on the new name of Alyce and begins to grow as she learns skills, but eventually runs away from the midwife. While away, she learns to read and write and discovers that she truly has a calling to be a midwife. She returns to Jane Sharp's service determined to learn.

Catherine, Called Birdy is a novel written as a diary. It begins in September 1290, with Catherine describing her father's manor, her parents, and the world she lives in. Her father wishes her to marry someone who will make advantageous social connections, but all the suitors he brings fall short of Birdy's ideal. Finally, Catherine's father demands her to marry an old, repulsive man whom she calls "Shaggy Beard." She refuses, and devises many scenarios to escape. As the day for Catherine's official betrothal approaches, she realizes that she herself will be the same no matter who she marries. However, Shaggy Beard dies and she is pleased to become engaged to his clean, young, educated son. The Midwife's Apprentice tells the story of a homeless, nameless orphan girl. Called Brat, the only name she can remember anyone calling her, she sleeps in dung heaps to keep warm until a harsh and uncaring midwife named Jane Sharp takes her in as an apprentice. She takes on the new name of Alyce and begins to grow as she learns skills, but eventually runs away from the midwife. While away, she learns to read and write and discovers that she truly has a calling to be a midwife. She returns to Jane Sharp's service determined to learn.

* Indicates required field What do you think? Which cover do you like best? * The one on the leftThe one in the middleThe one on the right Tell me why, if you'd like * Submit

* Indicates required field What do you think? Which cover do you like best? * The one on the leftThe one in the middleThe one on the right Tell me why, if you'd like * Submit

Just this week, the wonderful middle grade author Karen Cushman posted a link to an article written by the woman who is creating the cover for her newest book. Jamie Zollars explains the process she went through, and it is fascinating and well worth reading. Grayling's Song is Cushman's first fantasy novel, and as such the cover needed to be very different.

Just this week, the wonderful middle grade author Karen Cushman posted a link to an article written by the woman who is creating the cover for her newest book. Jamie Zollars explains the process she went through, and it is fascinating and well worth reading. Grayling's Song is Cushman's first fantasy novel, and as such the cover needed to be very different.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a writer that lives in central New Mexico. Her books On Fledgling Wings, the story of a motherless young boy in medieval England who wishes to become a knight to help himself feel more worthy, is on sale on Amazon now through December 8. You can read about the author and her books on her website.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a writer that lives in central New Mexico. Her books On Fledgling Wings, the story of a motherless young boy in medieval England who wishes to become a knight to help himself feel more worthy, is on sale on Amazon now through December 8. You can read about the author and her books on her website.

Catherine, Called Birdy is a novel written as a diary. It begins in September 1290, with Catherine describing her father's manor, her parents, and the world she lives in. Her father wishes her to marry someone who will make advantageous social connections, but all the suitors he brings fall short of Birdy's ideal. Finally, Catherine's father demands her to marry an old, repulsive man whom she calls "Shaggy Beard." She refuses, and devises many scenarios to escape. As the day for Catherine's official betrothal approaches, she realizes that she herself will be the same no matter who she marries. However, Shaggy Beard dies and she is pleased to become engaged to his clean, young, educated son. The Midwife's Apprentice tells the story of a homeless, nameless orphan girl. Called Brat, the only name she can remember anyone calling her, she sleeps in dung heaps to keep warm until a harsh and uncaring midwife named Jane Sharp takes her in as an apprentice. She takes on the new name of Alyce and begins to grow as she learns skills, but eventually runs away from the midwife. While away, she learns to read and write and discovers that she truly has a calling to be a midwife. She returns to Jane Sharp's service determined to learn.

Catherine, Called Birdy is a novel written as a diary. It begins in September 1290, with Catherine describing her father's manor, her parents, and the world she lives in. Her father wishes her to marry someone who will make advantageous social connections, but all the suitors he brings fall short of Birdy's ideal. Finally, Catherine's father demands her to marry an old, repulsive man whom she calls "Shaggy Beard." She refuses, and devises many scenarios to escape. As the day for Catherine's official betrothal approaches, she realizes that she herself will be the same no matter who she marries. However, Shaggy Beard dies and she is pleased to become engaged to his clean, young, educated son. The Midwife's Apprentice tells the story of a homeless, nameless orphan girl. Called Brat, the only name she can remember anyone calling her, she sleeps in dung heaps to keep warm until a harsh and uncaring midwife named Jane Sharp takes her in as an apprentice. She takes on the new name of Alyce and begins to grow as she learns skills, but eventually runs away from the midwife. While away, she learns to read and write and discovers that she truly has a calling to be a midwife. She returns to Jane Sharp's service determined to learn.

* Indicates required field What do you think? Which cover do you like best? * The one on the leftThe one in the middleThe one on the right Tell me why, if you'd like * Submit

* Indicates required field What do you think? Which cover do you like best? * The one on the leftThe one in the middleThe one on the right Tell me why, if you'd like * Submit

Just this week, the wonderful middle grade author Karen Cushman posted a link to an article written by the woman who is creating the cover for her newest book. Jamie Zollars explains the process she went through, and it is fascinating and well worth reading. Grayling's Song is Cushman's first fantasy novel, and as such the cover needed to be very different.

Just this week, the wonderful middle grade author Karen Cushman posted a link to an article written by the woman who is creating the cover for her newest book. Jamie Zollars explains the process she went through, and it is fascinating and well worth reading. Grayling's Song is Cushman's first fantasy novel, and as such the cover needed to be very different.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a writer that lives in central New Mexico. Her books On Fledgling Wings, the story of a motherless young boy in medieval England who wishes to become a knight to help himself feel more worthy, is on sale on Amazon now through December 8. You can read about the author and her books on her website.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a writer that lives in central New Mexico. Her books On Fledgling Wings, the story of a motherless young boy in medieval England who wishes to become a knight to help himself feel more worthy, is on sale on Amazon now through December 8. You can read about the author and her books on her website.

Published on December 04, 2021 23:00

November 27, 2021

Horses in History: Black Jack

Black Jack served the military in a unique way.

Black Jack served the military in a unique way.Black Jack was born on January 19,1947 and purchased by the US Army Quartermaster on November 22, 1953. Although his breeding wasn’t recorded, he is likely a mix of Morgan and Quarter horse. He was named in honor of John J. “Black Jack” Pershing, the U.S. Army General who led America’s military forces to victory in Europe during World War I. He was the last horse ever to be branded by the Army. He had the Army’s U.S. brand on his left shoulder and his Army serial number, 2V56, on the left side of his neck.

One of the traditional functions of the Army’s Quartermaster Corps was supplying the cavalry with well-trained horses. Fort Reno in Oklahoma was where most horses were trained, and it was where Black Jack went after being purchased. The feisty, spirited animal made it clear from the start that he did not like to carry riders. He threw rider after rider into the dirt of the training corral. Although his handlers did manage to control him somewhat, he never lost his fiery spirit, which made him a favorite at Fort Reno.

Black Jack was so beautiful that the Army decided not to part with him. Coal black, and with a small white star, the handsome horse was 15.1 hands tall and weighed almost 1,200 pounds. He was well built with a beautiful head. The Army transferred him to Virginia’s Fort Myer, where he was attached to the 3rd U.S. Infantry Regiment, known as “The Old Guard”. The Old Guard is the Army’s oldest active duty infantry regiment, dating back to 1784. The horses and soldiers that make up The Old Guard participate in an average of six funerals per day. Black Jack was placed into Caisson Platoon. Horses in the Caisson Platoon serve two functions. One is pulling funeral caissons. Caissons are small wagons that carried cannons, ammunition, spare parts, and tools. Funeral caissons have a flat platform on which the flag-draped casket sits. Six horses, matched blacks or grays that are paired into three teams, pull the caisson All six horses are saddled, but only the horses on the left have mounted riders. This tradition has carried over from the days of horse-drawn artillery, when one horse carried the soldier, and the other horse carried extra supplies. The three teams are the lead team in front, the swing team in the middle, and the wheel team closest to the caisson.

Instead of pulling a funeral caisson, Black Jack served as the Caparisoned, or riderless, horse that followed the caisson. The caparisoned horse represents the soldier who will no longer ride in the brigade. He wears the cavalry saddle, with a sword and a pair of boots reversed, or facing backwards, in the stirrups.

Riderless horses have been a part of military funerals since Ghengis Khan’s time. Then, the horses were sacrificed so that their spirits could travel with its master to the afterlife. While they are no longer sacrificed, riderless horses represent the bond between horse and rider on the soldier’s final journey. The backward boots in his stirrups suggest that the warrior is having one last look back at his life. In the United States, caparisoned horses participate in funerals for people who have achieved the rank of colonel in the Army or Marines or above.

Abraham Lincoln was the first U.S. president to have a caparisoned horse at his funeral. George Washington and Zachary Taylor’s personal horses were in their master’s funeral processions.

Abraham Lincoln was the first U.S. president to have a caparisoned horse at his funeral. George Washington and Zachary Taylor’s personal horses were in their master’s funeral processions.Black Jack was the riderless black horse in the funerals of three presidents: Herbert Hoover, John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson He also served in the funeral of Douglas MacArthur and more than a thousand others. Black Jack retired on June 1, 1973 and died after 29 years of military service on Feb. 6, 1976. He was buried on the parade grounds of Fort Myer with full military honors and his remains were transported using the same caisson he’d walked behind during the funerals of three American presidents.

The only other horse honored with a military funeral was Comanche, the only surviving horse of Custer’s last stand.

After Black Jack retired, “Sgt.York” carried on this tradition. He served as the riderless horse in President Reagan’s funeral procession, walking behind the caisson bearing Reagan’s flag-draped casket.

Jennifer Bohnhoff writes historical fiction for people from ten to adult. Several of her books, including Code:Elephants on the Moon and A Blaze of Poppies include horses used in war.

Jennifer Bohnhoff writes historical fiction for people from ten to adult. Several of her books, including Code:Elephants on the Moon and A Blaze of Poppies include horses used in war.

Published on November 27, 2021 23:00

November 23, 2021

Herbert Read: World War I Poet

Herbert Read was unlike many of the young, privileged Englishmen who left university to prove themselves in the bloody cauldron of war. Born in Yorkshire, he was the eldest child of a tenant farmer who died when he was still young. Because they didn’t own the farm, the family had to leave. Read was sent to a school for orphans. His mother took a job managing a laundry.

Herbert Read was unlike many of the young, privileged Englishmen who left university to prove themselves in the bloody cauldron of war. Born in Yorkshire, he was the eldest child of a tenant farmer who died when he was still young. Because they didn’t own the farm, the family had to leave. Read was sent to a school for orphans. His mother took a job managing a laundry. Read considered studying medicine after graduation. As a way to pay for it, he joined the local unit of the Royal Army Medical Corps and received a commission in the Green Howards, a Yorkshire Regiment. By the time he entered the University of Leeds, he’d decided that medicine wasn’t for him, so he transferred from the Medical Corps to the Officer Training Corps, where he found himself surrounded by men who had come through Eton or other public schools. Compared to them, Read felt provincial.

When the War broke out, Read left his studies and was shipped overseas. He found that he was far more comfortable dealing with the sixty or so men in his platoon than the other officers. His platoon was filled with men who had done hard work in the mines and factories of Durham and North Yorkshire. Many were older and more experienced than he, who became a captain in his early twenties, but he developed a good repoire with them. His fellow officers struck him as “snobbish and intolerant.”

He soon realized that “all the proud pretensions which men had acquired from a conventional environment” became insignificant at the front, and his fatalistic soldiers with their “Every bullet has it billet. What’s the use of worryin’?” attitude coped better than “men of mere brute strength, the footballers and school captains.”

Politically, Herbert Read was what the English call a “Quietist Anarchist.” He was no waver of flags and felt no fervor for one people over another. He expressed hope that the relationships that he had developed in the trenches would lead to new social movement after the war, and that class conflict and nationalities would be abandoned for a more egalitarian, universal social order. He saw signs that the world had wearied of war and was ready to put aside nationalism in this remembrance:

In April, 1918, when on a daylight ‘contact’ patrol with two of my men, we suddenly confronted, round some mound or excavation, a German patrol of the same strength. We were perhaps twenty yards from each other, fully visible. I waved a weary hand, as if to say: What is the use of killing each other? The German officer seemed to understand, and both parties turned and made their way back to their own trenches. Reprehensible conduct, no doubt, but in April, 1918, the war-weariness of the infantry was stronger than its pugnacity, on both sides of the line

However, when the end finally came, Read found that he had lost too much to sustain much hope. His youngest brother, who had followed him into the Green Howards and had served on the Italian Front, died of a bullet shot in the last few months of war, leaving him in a state of grief that allowed no sympathy or consolation. Others, he knew, felt similarly. “We left the war as we entered it: dazed, indifferent, incapable of any creative action. We had acquired only one new quality: exhaustion.”

When the Armistice came, a month later, I had no feelings, except possibly of self-congratulation. By then I had been sent to dreary barracks on the outskirts of Canterbury. There were misty fields around us, and perhaps a pealing bell to celebrate our victory. But my heart was numb and my mind dismayed: I turned to the fields and walked away from all human contacts.

Read, who earned both the Distinguished Service Order and the Military Cross, wrote two volumes of poetry based upon his war experiences: Songs of Chaos (1915) and Naked Warriors (1919). His poems are seen as a bridge between the lyrical forms used by Owen, Sassoon, and Graves and the epic form used by David Jones in In Parenthesis. His poem, Kneeshaw goes to War, which I have included here, tells the story of one soldier who finds his personal meaning through, or in spite of, the horrific experiences he endured during the war.

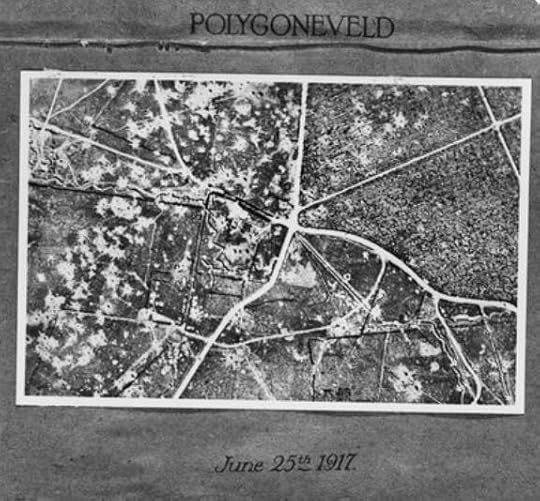

Aerial view of the Polygonveld (Polygon Wood) 25 June 1917. The town of Zonnebeke shelled to annihilation during WWI. Kneeshaw goes to War

Aerial view of the Polygonveld (Polygon Wood) 25 June 1917. The town of Zonnebeke shelled to annihilation during WWI. Kneeshaw goes to War1

Ernest Kneeshaw grew

In the forest of his dreams

Like a woodland flower whose anaemic petals

Need the sun.

Life was a far perspective

Of high black columns

Flanking, arching and encircling him.

He never, even vaguely, tried to pierce

The gloom about him,

But was content to contemplate

His finger-nails and wrinkled boots.

He might at least have perceived

A sexual atmosphere;

But even when his body burned and urged

Like the buds and roots around him,

Abash'd by the will-less promptings of his flesh,

He continued to contemplate his feet.

2

Kneeshaw went to war.

On bleak moors and among harsh fellows

They set about with much painstaking

To straighten his drooping back:

But still his mind reflected things

Like a cold steel mirror — emotionless;

Yet in reflecting he became accomplish'd

And, to some extent,

Divested of ancestral gloom.

Then Kneeshaw crossed the sea.

At Boulogne

He cast a backward glance across the harbours

And saw there a forest of assembled masts and rigging.

Like the sweep from a releas'd dam,

His thoughts flooded unfamiliar paths:

This forest was congregated

From various climates and strange seas:

Hadn't each ship some separate memory

Of sunlit scenes or arduous waters?

Didn't each bring in the high glamour

Of conquering force?

Wasn't the forest-gloom of their assembly

A body built of living cells,

Of personalities and experiences

— A witness of heroism

Co-existent with man?

And that dark forest of his youth —

Couldn't he liberate the black columns

Flanking, arching, encircling him with dread?

Couldn't he let them spread from his vision like a fleet

Taking the open sea,

Disintegrating into light and colour and the fragrance of winds?

And perhaps in some thought they would return

Laden with strange merchandise —

And with the passing thought

Pass unregretted into far horizons.

These were Kneeshaw's musings

Whilst he yet dwelt in the romantic fringes.

3

Then, with many other men,

He was transported in a cattle-truck

To the scene of war.

For a while chance was kind

Save for an inevitable

Searing of the mind.

But later Kneeshaw's war

Became intense.

The ghastly desolation

Sank into men's hearts and turned them black —

Cankered them with horror.

Kneeshaw felt himself

A cog in some great evil engine,

Unwilling, but revolv'd tempestuously

By unseen springs.

He plunged with listless mind

Into the black horror.

4

There are a few left who will find it hard to forget

Polygonveld.

The earth was scarr'd and broken

By torrents of plunging shells;

Then wash'd and sodden with autumnal rains.

And Polygonbeke

(Perhaps a rippling stream

In the days of Kneeshaw's gloom)

Spread itself like a fatal quicksand, —

A sucking, clutching death.

They had to be across the beke

And in their line before dawn.

A man who was marching by Kneeshaw's side

Hesitated in the middle of the mud,

And slowly sank, weighted down by equipment and arms.

He cried for help;

Rifles were stretched to him;

He clutched and they tugged,

But slowly he sank.

His terror grew —

Grew visibly when the viscous ooze

Reached his neck.

And there he seemed to stick,

Sinking no more.

They could not dig him out —

The oozing mud would flow back again.

The dawn was very near.

An officer shot him through the head:

Not a neat job — the revolver

Was too close.

5

Then the dawn came, silver on the wet brown earth.

Kneeshaw found himself in the second wave:

The unseen springs revolved the cog

Through all the mutations of that storm of death.

He started when he heard them cry " Dig in!"

He had to think and couldn't for a while.

Then he seized a pick from the nearest man

And clawed passionately upon the churned earth.

With satisfaction his pick

Cleft the skull of a buried man.

Kneeshaw tugged the clinging pick,

Saw its burden and shrieked.

For a second or two he was impotent

Vainly trying to recover his will, but his senses prevailing.

Then mercifully

A hot blast and riotous detonation

Hurled his mangled body

Into the beautiful peace of coma.

6

There came a day when Kneeshaw,

Minus a leg, on crutches,

Stalked the woods and hills of his native land.

And on the hills he would sing this war-song:

The forest gloom breaks:

The wild black masts

Seaward sweep on adventurous ways:

I grip my crutches and keep

A lonely view.

I stand on this hill and accept

The pleasure my flesh dictates

I count not kisses nor take

Too serious a view of tobacco.

Judas no doubt was right

In a mental sort of way:

For he betrayed another and so

With purpose was self-justified.

But I delivered my body to fear —

I was a bloodier fool than he.

I stand on this hill and accept

The flowers at my feet and the deep

Beauty of the still tarn:

Chance that gave me a crutch and a view

Gave me these.

The soul is not a dogmatic affair

Like manliness, colour, and light;

But these essentials there be:

To speak truth and so rule oneself

That other folk may rede.

Jennifer Bohnhoff used to teach high school and middle school English, and she often included a unit on the World War I poets. She has now retired and writes from the quietness of her own mountain home. He most recent book, A Blaze of Poppies, is about the experience of two New Mexicans during the Great War.

Jennifer Bohnhoff used to teach high school and middle school English, and she often included a unit on the World War I poets. She has now retired and writes from the quietness of her own mountain home. He most recent book, A Blaze of Poppies, is about the experience of two New Mexicans during the Great War.

Published on November 23, 2021 23:00

November 20, 2021

The Pony Express

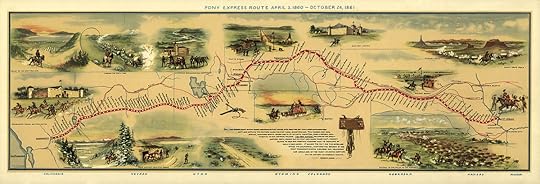

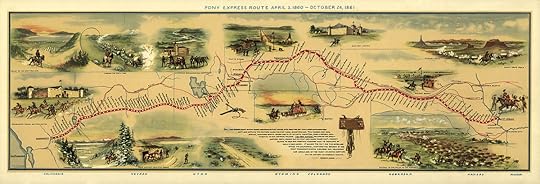

The Pony Express looms large in the lore of the American West, especially when one considers how short-lived it was. The Express, which was operated by Central Overland California and Pikes Peak Express Company, began delivering messages, newspapers, and mail on April 3, 1860. It was the quickest mode of delivering messages, and could get a letter from the Atlantic coast to the Pacific in about 10 days. By October 1861, the completion of the transcontinental telegraph had made the service obsolete.

The approximately 1,900-mile-long route for the Pony Express began at St. Joseph, Missouri, the far west terminus of the telegraph line. It roughly followed the Oregon and California Trails to Wyoming’s Fort Bridger, then followed the Mormon Trail to Salt Lake City, Utah. After that, it went to Carson City, Nevada Territory on the Central Nevada Route, then passed over the Sierra Nevadas before it reached Sacramento, California. From there, the mail went downriver by boat to San Francisco. About 186 stations were set up about 10 miles apart along the route. Riders changed to a fresh horse each station. They rode night and day, stopping after 75–100 miles. In emergencies, and when the next rider was unavailable, riders might ride two stages back-to-back, spending over 20 hours on horseback. Some of the stations had bunkhouses in which the riders could sleep.

The Pony Express Riders were all quite young, between 14 and 19 years old. They could not weigh over 125 pounds. At a time when unskilled laborers made between $0.43–$1 per day and bricklayers and carpenters could earn $2 per day, the riders received $125 a month, plus bonuses for fast completion of a route or for extraordinary dangers. The horses they rode were small, averaging 14.2 hands and 900 pounds, so while not strictly ponies, the name was appropriate.

The Pony Express Riders were all quite young, between 14 and 19 years old. They could not weigh over 125 pounds. At a time when unskilled laborers made between $0.43–$1 per day and bricklayers and carpenters could earn $2 per day, the riders received $125 a month, plus bonuses for fast completion of a route or for extraordinary dangers. The horses they rode were small, averaging 14.2 hands and 900 pounds, so while not strictly ponies, the name was appropriate.

One of the most famous Pony Express deliveries was done by Robert Haslam, who later went by the nickname “Pony Bob.” Haslam was born in London, England in 1840. In April 1861, he rode 13 mustangs on an eight hour ride that took him through 120 miles of Nevada Territory. His route went through hostile Paiute Indian country. According to his journal, he engaged in a “running fight” with warring braves that lasted for “three or four miles.” During that fight, a flint-tipped arrow pierced his arm and another broke his jaw and knocked out five teeth. Haslam was able to escape after shooting the horses out from under several of the Paiutes.  Haslam’s ride was part of a record-breaking delivery. While it usually took 10 days, this trip was completed in seven days, 17 hours. The delivery included Abraham Lincoln’s inaugural address, which helped the new state decide whether to stay within the Union or side with the Confederacy in the upcoming Civil War.

Haslam’s ride was part of a record-breaking delivery. While it usually took 10 days, this trip was completed in seven days, 17 hours. The delivery included Abraham Lincoln’s inaugural address, which helped the new state decide whether to stay within the Union or side with the Confederacy in the upcoming Civil War.

In recognition of his rapid and dangerous ride, the Express Company awarded Haslam $100. Although not delivering the packet might have changed the outcome of the war, Haslam was unfazed. He said, “ It’s nothing to get all fussed about. I’m a Pony Express rider. It’s all part of the job.”

When the Pony Express stopped, Pony Bob became and express rider for Wells, Fargo & Company. As the Pacific Railway and telegraph lines pushed westward, he took other routes in increasingly remote areas. When there were no more express routes, he moved to Chicago, where he died, destitute, in 1912. His tombstone was paid for by long-time friend and fellow pony express rider, William “Buffalo Bill” Cody. Jennifer Bohnhoff writes historical fiction for readers in middle school through adult. She learns a lot from her readers, and would like to thank Owen Currier for sharing the story of Pony Bob Haslam that was the inspiration for this blog.

The approximately 1,900-mile-long route for the Pony Express began at St. Joseph, Missouri, the far west terminus of the telegraph line. It roughly followed the Oregon and California Trails to Wyoming’s Fort Bridger, then followed the Mormon Trail to Salt Lake City, Utah. After that, it went to Carson City, Nevada Territory on the Central Nevada Route, then passed over the Sierra Nevadas before it reached Sacramento, California. From there, the mail went downriver by boat to San Francisco. About 186 stations were set up about 10 miles apart along the route. Riders changed to a fresh horse each station. They rode night and day, stopping after 75–100 miles. In emergencies, and when the next rider was unavailable, riders might ride two stages back-to-back, spending over 20 hours on horseback. Some of the stations had bunkhouses in which the riders could sleep.

The Pony Express Riders were all quite young, between 14 and 19 years old. They could not weigh over 125 pounds. At a time when unskilled laborers made between $0.43–$1 per day and bricklayers and carpenters could earn $2 per day, the riders received $125 a month, plus bonuses for fast completion of a route or for extraordinary dangers. The horses they rode were small, averaging 14.2 hands and 900 pounds, so while not strictly ponies, the name was appropriate.

The Pony Express Riders were all quite young, between 14 and 19 years old. They could not weigh over 125 pounds. At a time when unskilled laborers made between $0.43–$1 per day and bricklayers and carpenters could earn $2 per day, the riders received $125 a month, plus bonuses for fast completion of a route or for extraordinary dangers. The horses they rode were small, averaging 14.2 hands and 900 pounds, so while not strictly ponies, the name was appropriate.

One of the most famous Pony Express deliveries was done by Robert Haslam, who later went by the nickname “Pony Bob.” Haslam was born in London, England in 1840. In April 1861, he rode 13 mustangs on an eight hour ride that took him through 120 miles of Nevada Territory. His route went through hostile Paiute Indian country. According to his journal, he engaged in a “running fight” with warring braves that lasted for “three or four miles.” During that fight, a flint-tipped arrow pierced his arm and another broke his jaw and knocked out five teeth. Haslam was able to escape after shooting the horses out from under several of the Paiutes.

Haslam’s ride was part of a record-breaking delivery. While it usually took 10 days, this trip was completed in seven days, 17 hours. The delivery included Abraham Lincoln’s inaugural address, which helped the new state decide whether to stay within the Union or side with the Confederacy in the upcoming Civil War.

Haslam’s ride was part of a record-breaking delivery. While it usually took 10 days, this trip was completed in seven days, 17 hours. The delivery included Abraham Lincoln’s inaugural address, which helped the new state decide whether to stay within the Union or side with the Confederacy in the upcoming Civil War.

In recognition of his rapid and dangerous ride, the Express Company awarded Haslam $100. Although not delivering the packet might have changed the outcome of the war, Haslam was unfazed. He said, “ It’s nothing to get all fussed about. I’m a Pony Express rider. It’s all part of the job.”

When the Pony Express stopped, Pony Bob became and express rider for Wells, Fargo & Company. As the Pacific Railway and telegraph lines pushed westward, he took other routes in increasingly remote areas. When there were no more express routes, he moved to Chicago, where he died, destitute, in 1912. His tombstone was paid for by long-time friend and fellow pony express rider, William “Buffalo Bill” Cody. Jennifer Bohnhoff writes historical fiction for readers in middle school through adult. She learns a lot from her readers, and would like to thank Owen Currier for sharing the story of Pony Bob Haslam that was the inspiration for this blog.

Published on November 20, 2021 23:00

November 16, 2021

Charles Hamilton Sorley, World War I Poet

Charles Hamilton Sorley was born on May 19, 1895 in Aberdeen, Scotland. His father was a professor of moral philosophy. The family moved to Cambridge when Sorley was five. He attended King’s College choir school and, like fellow WWI poet Siegfried Sassoon, Marlborough College, where he ran cross-country. Several of his pre-war poems are about running, especially in the rain.

Charles Hamilton Sorley was born on May 19, 1895 in Aberdeen, Scotland. His father was a professor of moral philosophy. The family moved to Cambridge when Sorley was five. He attended King’s College choir school and, like fellow WWI poet Siegfried Sassoon, Marlborough College, where he ran cross-country. Several of his pre-war poems are about running, especially in the rain.Sorley received a scholarship to University College, Oxford. Before attending, however, he decided to spend sometime in Germany. He spent three months studying language and culture at Schwerin, then enrolled at the University of Jena. When Britain declared war on Germany, he was detained for a brief time, then told to leave the country.

Sorley returned to England and volunteered for military service. He joined the Suffolk Regiment, which arrived at the Western Front in May 1915. Sorley quickly rose from lieutenant to captain. On October 13, 1915 he was killed in action during the Battle of Loos by a sniper’s head shot. His last poem, “When You See Millions of the Mouthless Dead” was discovered in his kitbag after his death.

The first collection of Sorley’s poetry, titled Marlborough and other Poems, was published posthumously and went through six editions in the first year. Sorley’s deeply conflicted attitude about war is evident in his poetry and is likely due to his time in Germany. was from its start. His poetry has been called ambivalent, ironic, and profound. In his autobiographical book Goodbye to All That, Robert Graves counted Sorley, along with Wilfred Owen and Isaac Rosenberg as “the three poets of importance killed during the war.” 'When You See Millions of the Mouthless Dead'

When you see millions of the mouthless dead

When you see millions of the mouthless deadAcross your dreams in pale battalions go,

Say not soft things as other men have said,

That you'll remember. For you need not so.

Give them not praise. For, deaf, how should they know

It is not curses heaped on each gashed head?

Nor tears. Their blind eyes see not your tears flow.

Nor honour. It is easy to be dead.

Say only this, “They are dead.” Then add thereto,

“Yet many a better one has died before.”

Then, scanning all the o'ercrowded mass, should you

Perceive one face that you loved heretofore,

It is a spook. None wears the face you knew.

Great death has made all his for evermore.

Published on November 16, 2021 23:00

November 14, 2021

Two Variations on the Cookie with a Thousand Names

Okay, so a thousand names is a bit of hyperbole, but these are the cookies that everyone seems to call by a different name. I’ve heard these called Snowballs, Swedish Tea Cakes, Mexican Wedding Cookie, Russian Tea Cakes, and Butterballs, and I wouldn’t be surprised if you, dear readers, offered me an additional name or two.

Okay, so a thousand names is a bit of hyperbole, but these are the cookies that everyone seems to call by a different name. I’ve heard these called Snowballs, Swedish Tea Cakes, Mexican Wedding Cookie, Russian Tea Cakes, and Butterballs, and I wouldn’t be surprised if you, dear readers, offered me an additional name or two.Whatever you call them, these cookies have been a constant on the Bohnhoff Family Christmas cookie platter since long before I became a Bohnhoff. In our house, these cookies are made in balls, but I’ve seen them made into logs and crescents, too.

When my boys were young, I doubled this recipe every year. Sometimes I had to make it twice to make sure we had some all the way through the holidays. Then I discovered that one of my daughters-in-law was a peppermint fan, so I found and adaption that pleased her. It has now become a second standard on the cookie plate. The boys are all grown up, and the need for hundreds of cookies lying around the house has lessened, so I’ve adapted once again, to make two kinds of cookies from one batch of dough. I’m including suggestions so that you can make a full batch of regular butterballs, a full batch of peppermint butterballs, or one mixed batch. I’ve found the easiest way to make these is using a food processor. If you don’t have one, you’ll have to grind the nuts and peppermints in a blender, a coffeemill or some other way, then mix the ingredients in a mixer or by hand. However you pursue these, I hope you enjoy them!

Since Sweden, Mexico and Russia all get credit for these cookies, I am including a person from each who immigrated to America and significantly impacted our society.

Butterballs and Peppermint Butterballs

Preheat oven to 325°

If you are making half a batch of peppermint butterballs, whirr the following ingredients in a food processor until the candies are crushed fine, then set aside in a shallow bowl. Double the ingredients if you plan to make all your cookies peppermint.

1/3 cup confectioner’s sugar

1/3 cup broken peppermint candies or candy canes

If you are making half a batch of butterballs, place 1/3 cup powdered sugar in another bowl and set aside. Use ½ cup of powdered sugar if you are making a full batch of butterballs.

To make the dough for both cookies, process in food processor until chopped very fine

½ pecans (you can use almonds or walnuts if you prefer. It occurs to me that pinons would make a lovely New Mexican version of this cookie)

Add to food processor and pulse until mixed with the nuts.

½ cup powdered sugar

2 cups flour

¼ tsp salt

Add to ingredients in food processor and pulse until everything is blended into a dough that bunches together in a ball.

1 cup butter, softened to room temperature

1 tsp vanilla

Take dough out of food processor and knead on the counter a few times if you feel the butter hasn’t distributed all the way.

If you are making both variations of cookies, divide the dough in two.

To make butterballs, shape the dough into crescents, logs or balls about 1” large. Roll in the reserved bowl of powdered sugar. Place 1 inch apart on ungreased cookie sheet. Bake at 325° for 15-20 minutes until set but not brown. Cool on a cooling rack, then roll again in powdered sugar.

To make filling for a half batch of peppermint butterballs, mix the following in a small bowl. Double ingredients if you are making a full batch

2 TBS peppermint and powdered sugar mixture

1 TBS cream cheese, softened

¼ cup powdered sugar

½ tsp milk

Put a tablespoon of dough into your hand and form into a ball. Use your thumb to make a pocket in the middle of the ball, and fill it with about ¼ tsp of the filling. Seal the ball shut and roll it in the peppermint and powdered sugar mixture. Place 1 inch apart on ungreased cookie sheet. Bake at 325° for 15-20 minutes until set but not brown. Cool on a cooling rack, then roll again in powdered sugar and crushed peppermints.

The Swede responsible for a famous American icon Alexander Samuelson was born in Kareby parish, Kungälv, Bohuslän, Sweden in 1862. A glass engineer, he emigrated from Sweden to the United States in 1883 and is credited with designing the famous Coca-Cola contour bottle in 1915. Although the shape has been modified, this bottle remains one of the most recognized trademark and package in the world.

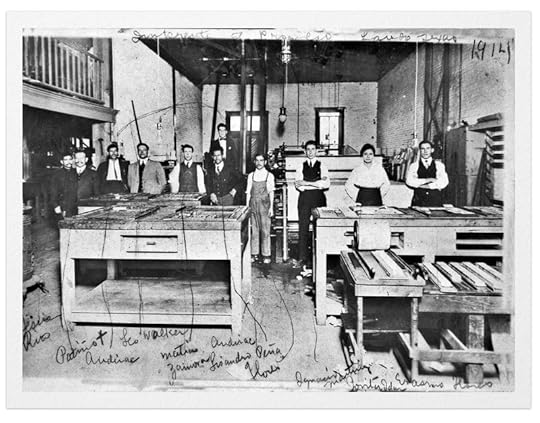

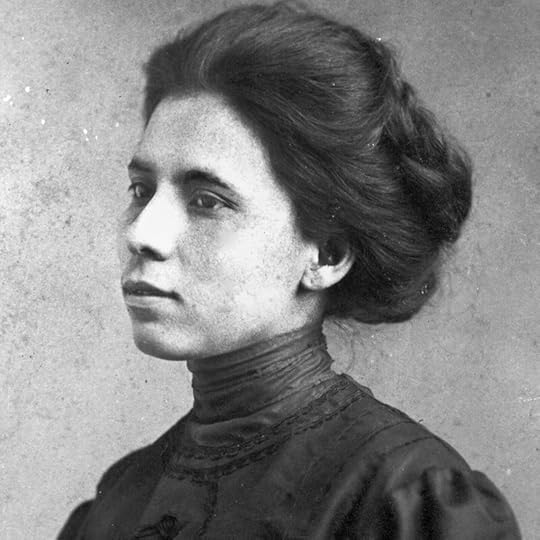

The Mexican American who Fought for better education and voting rights Jovita Idár was born in 1885, in Laredo, Texas, right on the border with Mexico. She wrote for her father’s Spanish language newspaper, La Crónica, using it as a platform to speak out against racism and in support of women’s and Mexican-Americans’ rights to vote and to receive decent educations. In 1915, when Woodrow Wilson sent troops to the Mexican-American border, Idár wrote a scathing editorial condemning the President’s actions. When the Texas Rangers arrived at the newspaper’s office, intent on shutting it down, she barred the door with her own body. https://americansall.org/legacy-story-individual/jovita-id-r

The Mexican American who Fought for better education and voting rights Jovita Idár was born in 1885, in Laredo, Texas, right on the border with Mexico. She wrote for her father’s Spanish language newspaper, La Crónica, using it as a platform to speak out against racism and in support of women’s and Mexican-Americans’ rights to vote and to receive decent educations. In 1915, when Woodrow Wilson sent troops to the Mexican-American border, Idár wrote a scathing editorial condemning the President’s actions. When the Texas Rangers arrived at the newspaper’s office, intent on shutting it down, she barred the door with her own body. https://americansall.org/legacy-story-individual/jovita-id-r

The Russian who keeps us Entertained at Home Vladimir Kosmich Zworykin was born in Murom, Russia, in 1888. He studied "electrical telescopy," later called television, at the St. Petersburg Institute of Technology. During World War I, Zworykin served in the Russian Signal Corps, testing radio equipment that was being produced for the Russian Army. In 1918, after the Russian Civil War broke out, made several trips to the United States on official duties. When the White party collapsed, Zworykin decided to remain permanently in the US. He got a job at the Westinghouse laboratories in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where he was able to continue experimenting on television. In 1923, he applied for a television patent.

The Russian who keeps us Entertained at Home Vladimir Kosmich Zworykin was born in Murom, Russia, in 1888. He studied "electrical telescopy," later called television, at the St. Petersburg Institute of Technology. During World War I, Zworykin served in the Russian Signal Corps, testing radio equipment that was being produced for the Russian Army. In 1918, after the Russian Civil War broke out, made several trips to the United States on official duties. When the White party collapsed, Zworykin decided to remain permanently in the US. He got a job at the Westinghouse laboratories in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where he was able to continue experimenting on television. In 1923, he applied for a television patent.

Jennifer Bohnhoff's latest novel, A Blaze of Poppies is set in the same time period as these three people lived and worked.

Jennifer Bohnhoff's latest novel, A Blaze of Poppies is set in the same time period as these three people lived and worked. Jennifer Bohnhoff is a writer of historical and contemporary fiction for middle grade readers through adults. Each year, she sends a book of recipes out to the friends, fans and family on her email list. If you'd like to join this list, click here.

Published on November 14, 2021 14:14