Jennifer Bohnhoff's Blog, page 22

October 26, 2021

Rupert Brooke, The Golden Boy of WWI Poets

In his day, the handsome and charming Rupert Brooke was a celebrity. In Dictionary of Literary Biography, Doris L. Eder calls him "a golden-haired, blue-eyed English Adonis." The Irish poet W B. Yeats called him “the most handsome man in Britain". But it was his poetry that made Brooke a national hero.

In his day, the handsome and charming Rupert Brooke was a celebrity. In Dictionary of Literary Biography, Doris L. Eder calls him "a golden-haired, blue-eyed English Adonis." The Irish poet W B. Yeats called him “the most handsome man in Britain". But it was his poetry that made Brooke a national hero.

Brooke had his finger on the pulse of the nation. Before the outbreak of World War I, the British were proud colonialists, confident in their strength and proud of their ability to control an empire that stretched around the globe. But the Pax Britannia, the relatively peaceful world that Britain’s control had secured, weighed heavily on its restless and pampered youth, of which Brooke was one. Brooke was born into a privileged family on August 3, 1887. He attended Rugby, where he was a head prefect and captain of the rugby team. At Cambridge University he studied Classics and moved in intellectual circles. After college he traveled to America and the South Seas and spent a year in Germany. His first book of poems, published in 1911, were not well received. However, one of his poems written in Germany in 1912 touched the hearts of the English and catapulted him into the limelight. The speaker in "The Old Vicarage, Grantchester," is a homesick Englishman who asks

“Stands the Church clock at ten to three?

And is there honey still for tea?" When war broke out in August 1914, Brooke, like the rest of the nation, was ready to join. His sonnet, "Peace," demonstrates how war was welcomed by a youth whose life felt frivolous and void of meaning. Wanting to prove himself, he enlisted in the Royal Naval Reserve and saw some brief action at Antwerp in October 1914.

Brooke’s best-known poem, “The Soldier," was read from the pulpit on Easter Sunday 1915. The reader commented that “such enthusiasm of a pure and elevated patriotism had never found a nobler expression". On March 11, both the poem and the comment were repeated in The Times, and Rupert Brooke became Britain’s ideal handsome young warrior. His poems expressed the idealism, patriotic fervor, and romantic sacrifice that the public wanted.

But Brooke would not live to hear the nation’s praises. He was sent east with the British Mediterranean Expeditionary Force at the start of the Gallipoli offensive. While sailing aboard the transport ship Grantully Castle, he was bitten on his lip by a mosquito. The bite festered, and he was transferred to a French hospital ship that was anchored off the island of Skyros. About a week after his poem was red, Brooke died, of septicemia or blood poisoning, on April 23 1915. His friends buried him in an olive grove on Skyros. He was only 27 years old.

But Brooke would not live to hear the nation’s praises. He was sent east with the British Mediterranean Expeditionary Force at the start of the Gallipoli offensive. While sailing aboard the transport ship Grantully Castle, he was bitten on his lip by a mosquito. The bite festered, and he was transferred to a French hospital ship that was anchored off the island of Skyros. About a week after his poem was red, Brooke died, of septicemia or blood poisoning, on April 23 1915. His friends buried him in an olive grove on Skyros. He was only 27 years old.A month after Brooke’s death, his friend Edward Marsh rushed the poems he had written in his last few months of life into print. Titled “1914 and Other Poems,” the collection included a romantic photo of him with bare shoulders and flowing hair that made many a woman swoon. Brooke became, according to Bernard Bergonzi, author of Heroes’ Twilight, the “quintessential young Englishman; one of the fairest of the nation’s sons; a ritual sacrifice offered as evidence of the justice of the cause for which England fought.” People as varied as Virginia Woolf and Winston Churchill paid him homage. First published in May 1915, the book was so popular that it had been reprinted 24 times by June 1918.

Brooke had expressed the sentiments of a nation anxious to show itself in war. As the war dragged on, the nation realized that it was not the glamorous, heroic show they had expected. Critics began to call Brooke’s poetry foolishly naive and sentimental, and harsher and more realistic poems began to grab the public imagination. There is little doubt that, had he lived longer and experienced some of the horrors other war poets did, Brooke’s poetry would have changed as well.

PeacE

Now, God be thanked who has matched us with his hour,

And caught our youth, and wakened us from sleeping!

With hand made sure, clear eye, and sharpened power,

To turn, as swimmers into cleanness leaping,

Glad from a world grown old and cold and weary;

Leave the sick hearts that honor could not move,

And half-men, and their dirty songs and dreary,

And all the little emptiness of love!

Oh! we, who have known shame, we have found release there,

Where there’s no ill, no grief, but sleep has mending,

Naught broken save this body, lost but breath;

Nothing to shake the laughing heart’s long peace there,

But only agony, and that has ending;

And the worst friend and enemy is but Death.

The Soldier

If I should die, think only this of me:

That there’s some corner of a foreign field

That is for ever England. There shall be

In that rich earth a richer dust concealed;

A dust whom England bore, shaped, made aware,

Gave, once, her flowers to love, her ways to roam;

A body of England’s, breathing English air,

Washed by the rivers, blest by suns of home.

And think, this heart, all evil shed away,

A pulse in the eternal mind, no less

Gives somewhere back the thoughts by England given;

Her sights and sounds; dreams happy as her day;

And laughter, learnt of friends; and gentleness,

In hearts at peace, under an English heaven.

Jennifer Bohnhoff lives and writes in the mountains of central New Mexico. Her latest book, A Blaze of Poppies, is the story of a young cowgirl struggling to keep the ranch during the tumultuous years leading up to and during World War I. It is available directly from the author and in paperback and ebook on Amazon.

Jennifer Bohnhoff lives and writes in the mountains of central New Mexico. Her latest book, A Blaze of Poppies, is the story of a young cowgirl struggling to keep the ranch during the tumultuous years leading up to and during World War I. It is available directly from the author and in paperback and ebook on Amazon.

Published on October 26, 2021 23:00

October 23, 2021

Why the Ladies Dance

Morris dancing is a type of English folk that has been around since at least the fourteenth century. The earliest record of it is from May 19, 1448, when a ground of Morris dancers in London were paid 7s (35p) for their services. By Elizabethan times it was already considered to be an ancient dance, and references appear to it in a number of early plays

Morris dancing is a type of English folk that has been around since at least the fourteenth century. The earliest record of it is from May 19, 1448, when a ground of Morris dancers in London were paid 7s (35p) for their services. By Elizabethan times it was already considered to be an ancient dance, and references appear to it in a number of early playsThe term 'morris' most likely came from the French word morisque, which means 'a dance.'

Usually, Morris dancing is accompanied by music, but sometimes it is unaccompanied. The dancers often wear bell pads on their shins and carry sticks, swords or handkerchiefs.

And up until the twentieth century, the rhythmic stepping and intricately choreographed figures were always, exclusively, performed by men.

And up until the twentieth century, the rhythmic stepping and intricately choreographed figures were always, exclusively, performed by men.World War I changed that.

During the First World War, much of the English countryside was largely devoid of their menfolk. Unless women stepped in, fields lay fallow and crops weren't harvested. The situation wasn't much better after the end of the war. In some English towns and villages, male mortality rate approached seventy percent. Just like the fields, women needed to step in if the tradition of Morris dancing was to continue. In 1972, an English folk singer named Austin John Marshall heard someone commenting rather derisively on all the older women who participated in Morris dancing, and his heart went out to them. Marshall knew that many of the older ladies who participated in Country Dance Societies were war widows, or women who had lost fiancés or lovers during the Great War. Country dancing kept the memory of their young men alive, and it kept a centuries-old tradition from dying out.

Marshall wrote Whitsun Dance as a tribute to the widows, sweethearts, sisters and daughters of the men lost in World War I. He wrote it fifty years after the war ended. Another fifty has passed since that time. May we continue to keep alive the memories. Whitsun Dance It's fifty long springtimes since she was a bride,

But still you may see her at each Whitsuntide

In a dress of white linen with ribbons of green,

As green as her memories of loving.

The feet that were nimble tread carefully now,

As gentle a measure as age will allow,

Through groves of white blossoms, by fields of young corn,

Where once she was pledged to her true-love.

The fields they stand empty, the hedges grow (go) free--

No young men to turn them or pastures go see (seed)

They are gone where the forest of oak trees before

Have gone, to be wasted in battle.

Down from the green farmlands and from their loved ones

Marched husbands and brothers and fathers and sons.

There's a fine roll of honor where the Maypole once stood,

And the ladies go dancing at Whitsun.

There's a straight row of houses in these latter days

All covering the downs where the sheep used to graze.

There's a field of red poppies (a gift from the Queen)

But the ladies remember at Whitsun,

And the ladies go dancing at Whitsun.

Jennifer Bohnhoff's historical novel A Blaze of Poppies tells the story of a young rancher from Southern New Mexico who serves as a nurse in a French field hospital in a desperate attempt to keep her family's ranch from being sold, and to stay near the National Guardsman she has learned to love. You can read more about that novel here.

Jennifer Bohnhoff's historical novel A Blaze of Poppies tells the story of a young rancher from Southern New Mexico who serves as a nurse in a French field hospital in a desperate attempt to keep her family's ranch from being sold, and to stay near the National Guardsman she has learned to love. You can read more about that novel here.

Published on October 23, 2021 23:00

October 20, 2021

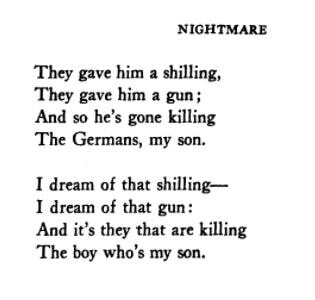

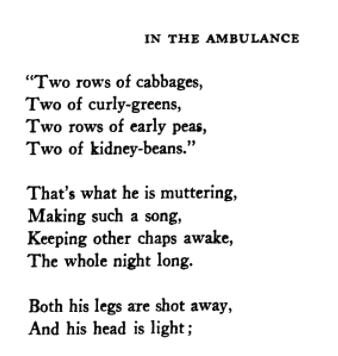

Two Poems by Wilfrid Wilson Gibson

Poetry was much more widely read during the early part of the twentieth century.

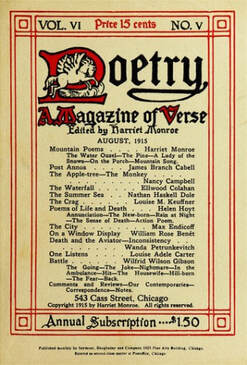

Poetry was much more widely read during the early part of the twentieth century. I am willing to be that few of my friends could name a contemporary poet, but at the time of World War I, many people could, and periodicals like the one pictured were common, making poetry accessible.

The August 1915 edition featured two poems by Wilfrid Gibson, a poet who was popular in his day but largely forgotten now. He was a member of the Georgian poets at a time when the Modernists were becoming popular.

Gibson almost missed World War I. The Army rejected his admission for several years because of his poor eyesight. When he finally entered, his experiences affected his poetry. A reviewer for the Boston Transcript said that Gibson’s battle poems were “nothing more than etchings, vignettes, of moods and impressions, but they register with a burning solution on the spirit what the personal side of the war means to those in the trenches and at home.”

Gibson almost missed World War I. The Army rejected his admission for several years because of his poor eyesight. When he finally entered, his experiences affected his poetry. A reviewer for the Boston Transcript said that Gibson’s battle poems were “nothing more than etchings, vignettes, of moods and impressions, but they register with a burning solution on the spirit what the personal side of the war means to those in the trenches and at home.”

Jennifer Bohnhoff's historical novel A Blaze of Poppies is set in southwestern New Mexico and on the Western Front during World War I.

Jennifer Bohnhoff's historical novel A Blaze of Poppies is set in southwestern New Mexico and on the Western Front during World War I.

Published on October 20, 2021 23:00

October 19, 2021

A Poet looks back at World War I

Edmund Charles Blunden was commissioned as a second lieutenant into the British Army's Royal Sussex Regiment during September of 1915. He served on the Western Front for the rest of the war, taking part in the actions at Ypres, the Somme, and Passchendaele. With the exception of being gassed in October 1917, he managed to survive nearly two full years on the front line without physical injury. However, he bore the mental scars of his war-time experiences for the rest of his life. In his memoir of the war, Undertones of War, published in 1928, Blunden attributed his survival to his size. A small man, he states this made him "an inconspicuous target."

Edmund Charles Blunden was commissioned as a second lieutenant into the British Army's Royal Sussex Regiment during September of 1915. He served on the Western Front for the rest of the war, taking part in the actions at Ypres, the Somme, and Passchendaele. With the exception of being gassed in October 1917, he managed to survive nearly two full years on the front line without physical injury. However, he bore the mental scars of his war-time experiences for the rest of his life. In his memoir of the war, Undertones of War, published in 1928, Blunden attributed his survival to his size. A small man, he states this made him "an inconspicuous target."After he left the army in 1919, he returned to Oxford and resumed the scholarship work he had left when the war began. One of his classmates was fellow poet, author and literary critic, Robert Graves, and the two developed a close friendship. Blunden was also a lifelong friend of Siegfried Sassoon.

Blunden ended his literary career with two years as Oxford’s Professor of Poetry, a position also held by Graves. He died on January 20, 1974. 1916 seen from 1921

Tired with dull grief, grown old before my day,

I sit in solitude and only hear

Long silent laughters, murmurings of dismay,

The lost intensities of hope and fear;

In those old marshes yet the rifles lie,

On the thin breastwork flutter the grey rags,

The very books I read are there—and I

Dead as the men I loved, wait while life drags

Its wounded length from those sad streets of war

Into green places here, that were my own;

But now what once was mine is mine no more,

I seek such neighbours here and I find none.

With such strong gentleness and tireless will

Those ruined houses seared themselves in me,

Passionate I look for their dumb story still,

And the charred stub outspeaks the living tree.

I rise up at the singing of a bird

And scarcely knowing slink along the lane,

I dare not give a soul a look or word

Where all have homes and none’s at home in vain:

Deep red the rose burned in the grim redoubt,

The self-sown wheat around was like a flood,

In the hot path the lizard lolled time out,

The saints in broken shrines were bright as blood.

Sweet Mary’s shrine between the sycamores!

There we would go, my friend of friends and I,

And snatch long moments from the grudging wars,

Whose dark made light intense to see them by.

Shrewd bit the morning fog, the whining shots

Spun from the wrangling wire: then in warm swoon

The sun hushed all but the cool orchard plots,

We crept in the tall grass and slept till noon.

A Blaze of Poppies, Jennifer Bohnhoff's novel about World War I, is available on Amazon and directly from the author.

A Blaze of Poppies, Jennifer Bohnhoff's novel about World War I, is available on Amazon and directly from the author.

Published on October 19, 2021 23:00

October 14, 2021

Italian Americans - and Cookies

This past Monday was the controversial holiday of Columbus Day. You may or may not celebrate this holiday any more, and I do understand why some people do not want to, but there have been many people with Italian heritage that have done good things for America. Here are just a few of them.  In 1914, a 16 year old boy named Ettore Boiardi came from his home town of Piacenza, Italy to join his brother, a waiter at New York’s Plaza Hotel. He later moved to Cleveland, where he had his own restaurant. By 1928, he realized that there was a market for Italian foods that people could make at home, so he opened a factory. He sold his packaged Italian foods under the name “Boy-Ar-Dee” so that Americans would correctly pronounce his last name.

In 1914, a 16 year old boy named Ettore Boiardi came from his home town of Piacenza, Italy to join his brother, a waiter at New York’s Plaza Hotel. He later moved to Cleveland, where he had his own restaurant. By 1928, he realized that there was a market for Italian foods that people could make at home, so he opened a factory. He sold his packaged Italian foods under the name “Boy-Ar-Dee” so that Americans would correctly pronounce his last name.

Enrico Fermi was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for his work on radioactivity and the discovery of new elements in 1938. Soon after, the physicist left his position at the University of Rome and defected to the U.S. to escape Benito Mussolini's regime. Fermi oversaw the first controlled nuclear chain reaction in Chicago in December 1942, after which he became the associate director of the Manhattan Project. Fermi later argued against the creation of the hydrogen bomb on ethical grounds, but he remains one of the leading architects of the nuclear age.

Enrico Fermi was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for his work on radioactivity and the discovery of new elements in 1938. Soon after, the physicist left his position at the University of Rome and defected to the U.S. to escape Benito Mussolini's regime. Fermi oversaw the first controlled nuclear chain reaction in Chicago in December 1942, after which he became the associate director of the Manhattan Project. Fermi later argued against the creation of the hydrogen bomb on ethical grounds, but he remains one of the leading architects of the nuclear age.

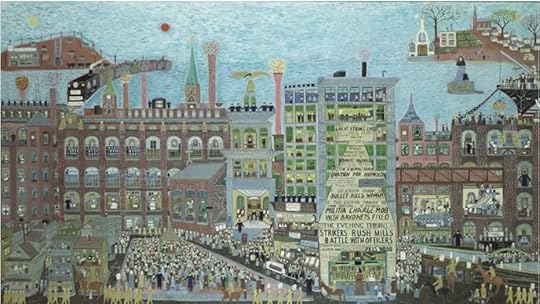

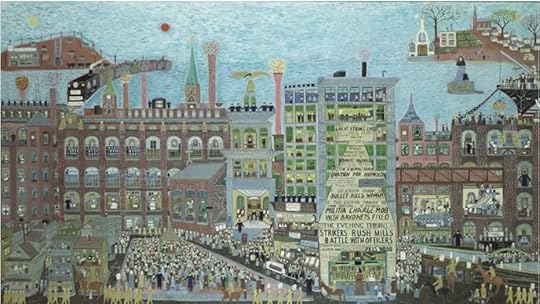

Ralph Fasanella fought with the Abraham Lincoln Brigade during the Spanish Civil War. Later, the self-taught artist helped organize his fellow workers for higher wages and a better life.

Ralph Fasanella fought with the Abraham Lincoln Brigade during the Spanish Civil War. Later, the self-taught artist helped organize his fellow workers for higher wages and a better life.

Many of his paintings reflect a nation of working people who took collective action to improve life on and off the job. One of his most recognized paintings is of the 1912 Lawrence Textile Strike.

A schoolteacher who then earned her law degree and became a criminal prosecutor and then a congresswoman, Geraldine Ferraro was the first woman and first Italian American to earn the vice-presidential nomination on a major party ticket, when she joined Democratic presidential hopeful Walter Mondale in 1984. Although she and Mondale were soundly defeated by incumbent Ronald Reagan, she inspired millions of American women to enter politics. Italian Anise Toast This may be easiest cookie to make, even if it does take two steps. It has no butter or shortening, so it's naturally low in fat, but the anise seeds pack such a flavor punch that you'd never realize it. These cookies are great for dunking into your favorite hot beverage. While coffee is probably the most traditional, I think here in October that spiced apple cider is a good choice! manga!

A schoolteacher who then earned her law degree and became a criminal prosecutor and then a congresswoman, Geraldine Ferraro was the first woman and first Italian American to earn the vice-presidential nomination on a major party ticket, when she joined Democratic presidential hopeful Walter Mondale in 1984. Although she and Mondale were soundly defeated by incumbent Ronald Reagan, she inspired millions of American women to enter politics. Italian Anise Toast This may be easiest cookie to make, even if it does take two steps. It has no butter or shortening, so it's naturally low in fat, but the anise seeds pack such a flavor punch that you'd never realize it. These cookies are great for dunking into your favorite hot beverage. While coffee is probably the most traditional, I think here in October that spiced apple cider is a good choice! manga!

2 eggs

2 eggs

2/3 cup sugar

1 teaspoon anise seed

1 cup flour

Heat oven to 375

Grease and flour a 9x5x3" loaf pan.

Beat eggs and sugar thoroughly. Add anise seed. Mix in flour.

Use a spatula to scrape batter into the greased and floured loaf pan. If the batter is too stiff, get the spatula wet to smooth it out. It won't look like much batter, but never fear. It's enough!

Use a spatula to scrape batter into the greased and floured loaf pan. If the batter is too stiff, get the spatula wet to smooth it out. It won't look like much batter, but never fear. It's enough!

Bake at 375 for 35 minutes, or until a toothpick inserted in the loaf comes out clean.

Turn the loaf pan over onto a cutting board. Slice the loaf into 12-16 slices. The thinner the slice, the crunchier the cookie. 12 slices will result in chewy cookies.

Place the slices on a baking sheet and return to oven for five minutes. Turn them over (use a spatula if they stick) and toast for another five minutes on the other side.

Place the slices on a baking sheet and return to oven for five minutes. Turn them over (use a spatula if they stick) and toast for another five minutes on the other side.

Cool completely on a rack before storing.

Want a little fancier cookie? Omit anise seed and add 1/3 cup semisweet chocolate minichips, 1/3 cup shelled pistachios, and 1 tsp. finely grated orange peel to the batter before baking. Jennifer Bohnhoff is a former educator who now stays home and writes. Click here to see more about her and her writing.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a former educator who now stays home and writes. Click here to see more about her and her writing.

In 1914, a 16 year old boy named Ettore Boiardi came from his home town of Piacenza, Italy to join his brother, a waiter at New York’s Plaza Hotel. He later moved to Cleveland, where he had his own restaurant. By 1928, he realized that there was a market for Italian foods that people could make at home, so he opened a factory. He sold his packaged Italian foods under the name “Boy-Ar-Dee” so that Americans would correctly pronounce his last name.

In 1914, a 16 year old boy named Ettore Boiardi came from his home town of Piacenza, Italy to join his brother, a waiter at New York’s Plaza Hotel. He later moved to Cleveland, where he had his own restaurant. By 1928, he realized that there was a market for Italian foods that people could make at home, so he opened a factory. He sold his packaged Italian foods under the name “Boy-Ar-Dee” so that Americans would correctly pronounce his last name.

Enrico Fermi was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for his work on radioactivity and the discovery of new elements in 1938. Soon after, the physicist left his position at the University of Rome and defected to the U.S. to escape Benito Mussolini's regime. Fermi oversaw the first controlled nuclear chain reaction in Chicago in December 1942, after which he became the associate director of the Manhattan Project. Fermi later argued against the creation of the hydrogen bomb on ethical grounds, but he remains one of the leading architects of the nuclear age.

Enrico Fermi was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for his work on radioactivity and the discovery of new elements in 1938. Soon after, the physicist left his position at the University of Rome and defected to the U.S. to escape Benito Mussolini's regime. Fermi oversaw the first controlled nuclear chain reaction in Chicago in December 1942, after which he became the associate director of the Manhattan Project. Fermi later argued against the creation of the hydrogen bomb on ethical grounds, but he remains one of the leading architects of the nuclear age.

Ralph Fasanella fought with the Abraham Lincoln Brigade during the Spanish Civil War. Later, the self-taught artist helped organize his fellow workers for higher wages and a better life.

Ralph Fasanella fought with the Abraham Lincoln Brigade during the Spanish Civil War. Later, the self-taught artist helped organize his fellow workers for higher wages and a better life.Many of his paintings reflect a nation of working people who took collective action to improve life on and off the job. One of his most recognized paintings is of the 1912 Lawrence Textile Strike.

A schoolteacher who then earned her law degree and became a criminal prosecutor and then a congresswoman, Geraldine Ferraro was the first woman and first Italian American to earn the vice-presidential nomination on a major party ticket, when she joined Democratic presidential hopeful Walter Mondale in 1984. Although she and Mondale were soundly defeated by incumbent Ronald Reagan, she inspired millions of American women to enter politics. Italian Anise Toast This may be easiest cookie to make, even if it does take two steps. It has no butter or shortening, so it's naturally low in fat, but the anise seeds pack such a flavor punch that you'd never realize it. These cookies are great for dunking into your favorite hot beverage. While coffee is probably the most traditional, I think here in October that spiced apple cider is a good choice! manga!

A schoolteacher who then earned her law degree and became a criminal prosecutor and then a congresswoman, Geraldine Ferraro was the first woman and first Italian American to earn the vice-presidential nomination on a major party ticket, when she joined Democratic presidential hopeful Walter Mondale in 1984. Although she and Mondale were soundly defeated by incumbent Ronald Reagan, she inspired millions of American women to enter politics. Italian Anise Toast This may be easiest cookie to make, even if it does take two steps. It has no butter or shortening, so it's naturally low in fat, but the anise seeds pack such a flavor punch that you'd never realize it. These cookies are great for dunking into your favorite hot beverage. While coffee is probably the most traditional, I think here in October that spiced apple cider is a good choice! manga!

2 eggs

2 eggs2/3 cup sugar

1 teaspoon anise seed

1 cup flour

Heat oven to 375

Grease and flour a 9x5x3" loaf pan.

Beat eggs and sugar thoroughly. Add anise seed. Mix in flour.

Use a spatula to scrape batter into the greased and floured loaf pan. If the batter is too stiff, get the spatula wet to smooth it out. It won't look like much batter, but never fear. It's enough!

Use a spatula to scrape batter into the greased and floured loaf pan. If the batter is too stiff, get the spatula wet to smooth it out. It won't look like much batter, but never fear. It's enough!Bake at 375 for 35 minutes, or until a toothpick inserted in the loaf comes out clean.

Turn the loaf pan over onto a cutting board. Slice the loaf into 12-16 slices. The thinner the slice, the crunchier the cookie. 12 slices will result in chewy cookies.

Place the slices on a baking sheet and return to oven for five minutes. Turn them over (use a spatula if they stick) and toast for another five minutes on the other side.

Place the slices on a baking sheet and return to oven for five minutes. Turn them over (use a spatula if they stick) and toast for another five minutes on the other side. Cool completely on a rack before storing.

Want a little fancier cookie? Omit anise seed and add 1/3 cup semisweet chocolate minichips, 1/3 cup shelled pistachios, and 1 tsp. finely grated orange peel to the batter before baking.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a former educator who now stays home and writes. Click here to see more about her and her writing.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a former educator who now stays home and writes. Click here to see more about her and her writing.

Published on October 14, 2021 03:21

October 13, 2021

A Question of Right and Wrong: Edward Thomas

Edward Thomas

Edward Thomas (1878-1917) was a poet, critic, biographer who was first encouraged to write poetry by his friend, the American poet Robert Frost. Most of his poetry focuses on rural English life. He was 39 years old when he was killed during the Battle of Arras, leaving behind a wife and three children. His first book of poetry had not yet been published when he died, but his work is now highly regarded.

This is the only poem he wrote on the subject of war. This is No Case of Petty Right or Wrong

BY EDWARD THOMAS

This is no case of petty right or wrong

This is no case of petty right or wrongThat politicians or philosophers

Can judge. I hate not Germans, nor grow hot

With love of Englishmen, to please newspapers.

Beside my hate for one fat patriot

My hatred of the Kaiser is love true:—

A kind of god he is, banging a gong.

But I have not to choose between the two,

Or between justice and injustice. Dinned

With war and argument I read no more

Than in the storm smoking along the wind

Athwart the wood. Two witches' cauldrons roar.

From one the weather shall rise clear and gay;

Out of the other an England beautiful

And like her mother that died yesterday.

Little I know or care if, being dull,

I shall miss something that historians

Can rake out of the ashes when perchance

The phoenix broods serene above their ken.

But with the best and meanest Englishmen

I am one in crying, God save England, lest

We lose what never slaves and cattle blessed.

The ages made her that made us from dust:

She is all we know and live by, and we trust

She is good and must endure, loving her so:

And as we love ourselves we hate our foe.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a writer who lives in the mountains of central New Mexico. Her World War I novel, A Blaze of Poppies, is available on Amazon in ebook and paperback.

Published on October 13, 2021 23:00

October 14th, 2021

Edward Thomas

Edward Thomas (1878-1917) was a poet, critic, biographer who was first encouraged to write poetry by his friend, the American poet Robert Frost. Most of his poetry focuses on rural English life. He was 39 years old when he was killed during the Battle of Arras, leaving behind a wife and three children. His first book of poetry had not yet been published when he died, but his work is now highly regarded.

This is the only poem he wrote on the subject of war. This is No Case of Petty Right or Wrong

BY EDWARD THOMAS

This is no case of petty right or wrong

This is no case of petty right or wrongThat politicians or philosophers

Can judge. I hate not Germans, nor grow hot

With love of Englishmen, to please newspapers.

Beside my hate for one fat patriot

My hatred of the Kaiser is love true:—

A kind of god he is, banging a gong.

But I have not to choose between the two,

Or between justice and injustice. Dinned

With war and argument I read no more

Than in the storm smoking along the wind

Athwart the wood. Two witches' cauldrons roar.

From one the weather shall rise clear and gay;

Out of the other an England beautiful

And like her mother that died yesterday.

Little I know or care if, being dull,

I shall miss something that historians

Can rake out of the ashes when perchance

The phoenix broods serene above their ken.

But with the best and meanest Englishmen

I am one in crying, God save England, lest

We lose what never slaves and cattle blessed.

The ages made her that made us from dust:

She is all we know and live by, and we trust

She is good and must endure, loving her so:

And as we love ourselves we hate our foe.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a writer who lives in the mountains of central New Mexico. Her World War I novel, A Blaze of Poppies, is available on Amazon in ebook and paperback.

Published on October 13, 2021 23:00

October 12, 2021

Trench Idyll of Richard Aldington

Richard Aldington was a poet who interacted with the most famous poets of his time. He was born on July 8, 1892. His family had a large library of European and Classical literature. Both his mother and father wrote and published books. After attending school at Mr. Sweetman's Seminary for Young Gentlemen, Aldington attended Dover College and the University of London. Aldington was good at languages, and mastered French, Italian, Latin, and ancient Greek. He then went on to become a sports journalist and started publishing poetry in British journals. Soon he was associating with the likes of William Butler Yeats and Walter de la Mare.

Richard Aldington was a poet who interacted with the most famous poets of his time. He was born on July 8, 1892. His family had a large library of European and Classical literature. Both his mother and father wrote and published books. After attending school at Mr. Sweetman's Seminary for Young Gentlemen, Aldington attended Dover College and the University of London. Aldington was good at languages, and mastered French, Italian, Latin, and ancient Greek. He then went on to become a sports journalist and started publishing poetry in British journals. Soon he was associating with the likes of William Butler Yeats and Walter de la Mare.In 1911 Aldington met society hostess Brigit Patmore, who introduced him to American poets Ezra Pound and Hilda Doolittle, who published as H.D, and whom he married two years later. In 1914, the American poet Amy Lowell introduced him to writer D.H. Lawrence. T. S. Eliot was also acquainted with Aldington.

Aldington joined the Army in June 1916 and was sent to the front in December, where he dug graves. By the end of the war, he had become a signals officer and temporary captain. He was demobilised in February 1919.

Aldington found the lice, cold, mud and unsanitary conditions of a soldier's life degrading, but he managed to write poems, essays, and begin work on Death of a Hero, a semiautobiographical novel while still overseas. His encounters with gas on the front affected him for the rest of his life.

Aldington had difficulty returning to his former life after the war. He felt distant from his poet friends who had not undergone the tortuous life of a soldier, and felt they didn’t understand what he had gone through. Although published four volumes of poetry, Images of War and Images of Desire in 1919, Exile and Other Poems in 1923, and Roads to Glory in 1930, he never regained his prewar confidence in his own talent as a poet. He quit writing poetry entirely after suffering a nervous breakdown in 1925. His marriage also suffered, and he divorced his wife in 1938.

Like many American writers during this period, Aldington went into self-imposed exile. He moved to Paris in 1928.

In 1955 Aldington published a biography of T. E. Lawrence that caused a scandal by making public Lawrence's illegitimacy and homosexuality. His own reputation never recovered after he attacked the popular hero as a liar, a charlatan and an "impudent mythomaniac." Another English Poet from WWI, Robert Graves called Aldington "a bitter, bedridden, leering, asthmatic, elderly hangman-of-letters." Many wonder if he was still suffering from his trauma in the trenches.

Aldington died on July 27, 1962, shortly after his seventieth birthday.

Trench Idyll

We sat together in the trench,

He on a lump of frozen earth

Blown in the night before,

I on an unexploded shell;

And smoked and talked, like exiles,

Of how pleasant London was,

Its women, restaurants, night clubs, theatres,

How at that very hour

The taxi cabs were taking folk to dine …

Then we sat silent for a while

As a machine gun swept the parapet.

He said:

“I’ve been here on and off two years

And only seen one man killed.”

“That’s odd.”

“The bullet hit him in the throat;

He fell in a heap on the fire-step,

And called out ‘My God! dead!'”

“Good Lord, how terrible!”

“Well, as to that, the nastiest job I’ve had

Was last year on this very front

Taking the discs at night from men

Who’d hung for six months on the wire

Just over there.

The worst of all was

They fell to pieces at a touch,

Thank God we couldn’t see their faces;

They had gas helmets on …”

I shivered:

“It’s rather cold here, sir; suppose we move?”

This is one of a series of blogs on the poets of World War 1 written by Jennifer Bohnhoff, an author who lives in the mountains of central New Mexico. Her WWI Novel, A Blaze of Poppies, is available in ebook and paperback.

This is one of a series of blogs on the poets of World War 1 written by Jennifer Bohnhoff, an author who lives in the mountains of central New Mexico. Her WWI Novel, A Blaze of Poppies, is available in ebook and paperback.

Published on October 12, 2021 23:00

October 9, 2021

November 11, 1918

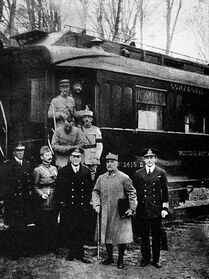

As far as most people are concerned, World War I ended at 11 am. Paris time on November 11, 1918. That is, when the Armistice of Compiègne, which was signed in a railcar at Le Francport, near the French town of Compiègne earlier that morning, took affect.

As far as most people are concerned, World War I ended at 11 am. Paris time on November 11, 1918. That is, when the Armistice of Compiègne, which was signed in a railcar at Le Francport, near the French town of Compiègne earlier that morning, took affect. The war had been winding down for a while already. Russia had left the war in March, 1918, when they agreed to the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, in which they turned over Finland, the Baltic provinces, parts of Poland and Ukraine to the Central Powers. Other armistices had taken Bulgaria, the Ottoman Empire and the Austro-Hungarian Empire out of the fighting.

The signing of the Armistice de Compiègne marked a victory for the Allies and a defeat, although not formally a surrender, for Germany. The terms of were largely written by the Allied Supreme Commander, French Marshal Ferdinand Foch. They included the cessation of hostilities on the Western Front, the withdrawal of German forces from west of the Rhine, and Allied occupation of the Rhineland and bridgeheads further east. All infrastructure in Germany was to be preserved for Allied use, and aircraft, warships, and military materiel were to be surrendered. Although Allied prisoners of war and interned civilians were to be released, the treaty did not specify the release of German prisoners, eventual reparations, and the naval blockade of Germany was not to be lifted.

The signing of the Armistice de Compiègne marked a victory for the Allies and a defeat, although not formally a surrender, for Germany. The terms of were largely written by the Allied Supreme Commander, French Marshal Ferdinand Foch. They included the cessation of hostilities on the Western Front, the withdrawal of German forces from west of the Rhine, and Allied occupation of the Rhineland and bridgeheads further east. All infrastructure in Germany was to be preserved for Allied use, and aircraft, warships, and military materiel were to be surrendered. Although Allied prisoners of war and interned civilians were to be released, the treaty did not specify the release of German prisoners, eventual reparations, and the naval blockade of Germany was not to be lifted.

Although the Armistice was officially signed at 5:45 a.m., it did not come into effect until 11am. This was to allow time for the news to reach combatants. There is no reason why 11am was chosen except for the symmetry of the numbers. Fighting continued in many sections of the front right up until the appointed hour, resulting in 10,944 casualties. 2,738 men died on the last day of the war. This led to controversy after the war. In the United States, Congress opened an investigation to find out why and if blame should be placed on the leaders of the American Expeditionary Forces. In France, many graves of French soldiers who died on 11 November were backdated to 10 November.

The author's husband looking into the restored train car. It is now kept in a dark room to preserve it. One reason the fighting continued was that many Allies didn’t trust that the Armistice would last, and wished to be in the most favorable position should fighting resume. Some artillery units reportedly continued to fire on German targets so they wouldn’t have to haul away their spare ammunition. Battery 4 of the US Navy fired its last shot long-range 14-inch railway gun from the Verdun area at 10:57:30 a.m., timed to land far behind the German front line just before the Armistice was scheduled to begin.

The author's husband looking into the restored train car. It is now kept in a dark room to preserve it. One reason the fighting continued was that many Allies didn’t trust that the Armistice would last, and wished to be in the most favorable position should fighting resume. Some artillery units reportedly continued to fire on German targets so they wouldn’t have to haul away their spare ammunition. Battery 4 of the US Navy fired its last shot long-range 14-inch railway gun from the Verdun area at 10:57:30 a.m., timed to land far behind the German front line just before the Armistice was scheduled to begin.When 11a.m. finally did arrive, the guns fell silent along most of the line. In some places, men on both sides laid down their arms, crossed the line, and shook hands. In other places, there was cheering and applause. But in general, soldiers were too tired and too wary that this was an illusion to do anything to celebrate. One British corporal reported: "...the Germans came from their trenches, bowed to us and then went away. That was it. There was nothing with which we could celebrate, except cookies."

The Peace Memorial at Compiègne Because this was a world-wide war, news of the armistice did not reach all battlefields at once. The King's African Rifles, fighting in what was then called Northern Rhodesia and is in today's Zambia, did not hear that the war was over for two weeks. When they did, the British commanders contacted the Germans and they their own armistice ceremony.

The Peace Memorial at Compiègne Because this was a world-wide war, news of the armistice did not reach all battlefields at once. The King's African Rifles, fighting in what was then called Northern Rhodesia and is in today's Zambia, did not hear that the war was over for two weeks. When they did, the British commanders contacted the Germans and they their own armistice ceremony.Although the armistice ended the fighting on the Western Front, the war did not actually, officially conclude until much later. The armistice that began on November 11 lasted until December 13, when the parties involved renegotiated terms that held until January 16, 1919. The peace was delayed two more times before June 28, when the Treaty of Versailles, was finally signed. The treaty was ratified, and the world was finally officially at peace on January 10, 1920.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is the author of A Blaze of Poppies, a novel set in New Mexico and France during World War 1.

Published on October 09, 2021 23:00

October 5, 2021

Siegfried Sassoon

Siegfried Sassoon was born into a wealthy Jewish family who were sometimes referred to as the “Rothschilds of the East” because their fortune was made in India. Before the war, he lived the leisurely life of a cultivated country gentleman, writing poetry that is not considered very good, and fox hunting.

Siegfried Sassoon was born into a wealthy Jewish family who were sometimes referred to as the “Rothschilds of the East” because their fortune was made in India. Before the war, he lived the leisurely life of a cultivated country gentleman, writing poetry that is not considered very good, and fox hunting.When the war began, Sassoon joined the Royal Welsh Fusiliers. He saw action in France in late 1915 and received a Military Cross for bringing back a wounded soldier during heavy fire.

After Sassoon was wounded in action, he wrote an open letter of protest to the war department in which he refused to fight any more. Sassoon thought his letter would lead to a court-martial, but friend and fellow poet Robert Graves successfully argued that Sassoon was suffering from shell-shock and needed medical treatment. In 1917, Sassoon was hospitalized.

Sassoon's war poems are angry and avoid sentimentality. Many of his detractors argue that his refusal to support the war effort was unpatriotic, but Sassoon's shockingly realistic depictions of war captured the feelings of soldiers and a public grown tired of the carnage.

After the war, Sassoon became involved in Labour Party politics, lectured on pacifism, wrote a trilogy of autobiographical novels, and published a critical biography of Victorian novelist and poet George Meredith. In 1957, Sassoon became a Catholic and began writing religious poems. He died in 1967 from stomach cancer. Attack

by Siegfried Sassoon

At dawn the ridge emerges massed and dun

In the wild purple of the glow'ring sun,

Smouldering through spouts of drifting smoke that shroud

The menacing scarred slope; and, one by one,

Tanks creep and topple forward to the wire.

The barrage roars and lifts. Then, clumsily bowed

With bombs and guns and shovels and battle-gear,

Men jostle and climb to, meet the bristling fire.

Lines of grey, muttering faces, masked with fear,

They leave their trenches, going over the top,

While time ticks blank and busy on their wrists,

And hope, with furtive eyes and grappling fists,

Flounders in mud. O Jesus, make it stop!

Jennifer Bohnhoff's novel, A Blaze of Poppies is set in southern New Mexico and in the trenches of World War I France.

Jennifer Bohnhoff's novel, A Blaze of Poppies is set in southern New Mexico and in the trenches of World War I France.

Published on October 05, 2021 23:00