Jennifer Bohnhoff's Blog, page 23

October 13, 2021

A Question of Right and Wrong: Edward Thomas

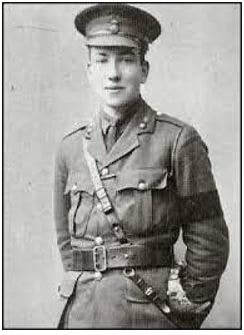

Edward Thomas

Edward Thomas (1878-1917) was a poet, critic, biographer who was first encouraged to write poetry by his friend, the American poet Robert Frost. Most of his poetry focuses on rural English life. He was 39 years old when he was killed during the Battle of Arras, leaving behind a wife and three children. His first book of poetry had not yet been published when he died, but his work is now highly regarded.

This is the only poem he wrote on the subject of war. This is No Case of Petty Right or Wrong

BY EDWARD THOMAS

This is no case of petty right or wrong

This is no case of petty right or wrongThat politicians or philosophers

Can judge. I hate not Germans, nor grow hot

With love of Englishmen, to please newspapers.

Beside my hate for one fat patriot

My hatred of the Kaiser is love true:—

A kind of god he is, banging a gong.

But I have not to choose between the two,

Or between justice and injustice. Dinned

With war and argument I read no more

Than in the storm smoking along the wind

Athwart the wood. Two witches' cauldrons roar.

From one the weather shall rise clear and gay;

Out of the other an England beautiful

And like her mother that died yesterday.

Little I know or care if, being dull,

I shall miss something that historians

Can rake out of the ashes when perchance

The phoenix broods serene above their ken.

But with the best and meanest Englishmen

I am one in crying, God save England, lest

We lose what never slaves and cattle blessed.

The ages made her that made us from dust:

She is all we know and live by, and we trust

She is good and must endure, loving her so:

And as we love ourselves we hate our foe.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a writer who lives in the mountains of central New Mexico. Her World War I novel, A Blaze of Poppies, is available on Amazon in ebook and paperback.

Published on October 13, 2021 23:00

October 14th, 2021

Edward Thomas

Edward Thomas (1878-1917) was a poet, critic, biographer who was first encouraged to write poetry by his friend, the American poet Robert Frost. Most of his poetry focuses on rural English life. He was 39 years old when he was killed during the Battle of Arras, leaving behind a wife and three children. His first book of poetry had not yet been published when he died, but his work is now highly regarded.

This is the only poem he wrote on the subject of war. This is No Case of Petty Right or Wrong

BY EDWARD THOMAS

This is no case of petty right or wrong

This is no case of petty right or wrongThat politicians or philosophers

Can judge. I hate not Germans, nor grow hot

With love of Englishmen, to please newspapers.

Beside my hate for one fat patriot

My hatred of the Kaiser is love true:—

A kind of god he is, banging a gong.

But I have not to choose between the two,

Or between justice and injustice. Dinned

With war and argument I read no more

Than in the storm smoking along the wind

Athwart the wood. Two witches' cauldrons roar.

From one the weather shall rise clear and gay;

Out of the other an England beautiful

And like her mother that died yesterday.

Little I know or care if, being dull,

I shall miss something that historians

Can rake out of the ashes when perchance

The phoenix broods serene above their ken.

But with the best and meanest Englishmen

I am one in crying, God save England, lest

We lose what never slaves and cattle blessed.

The ages made her that made us from dust:

She is all we know and live by, and we trust

She is good and must endure, loving her so:

And as we love ourselves we hate our foe.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a writer who lives in the mountains of central New Mexico. Her World War I novel, A Blaze of Poppies, is available on Amazon in ebook and paperback.

Published on October 13, 2021 23:00

October 12, 2021

Trench Idyll of Richard Aldington

Richard Aldington was a poet who interacted with the most famous poets of his time. He was born on July 8, 1892. His family had a large library of European and Classical literature. Both his mother and father wrote and published books. After attending school at Mr. Sweetman's Seminary for Young Gentlemen, Aldington attended Dover College and the University of London. Aldington was good at languages, and mastered French, Italian, Latin, and ancient Greek. He then went on to become a sports journalist and started publishing poetry in British journals. Soon he was associating with the likes of William Butler Yeats and Walter de la Mare.

Richard Aldington was a poet who interacted with the most famous poets of his time. He was born on July 8, 1892. His family had a large library of European and Classical literature. Both his mother and father wrote and published books. After attending school at Mr. Sweetman's Seminary for Young Gentlemen, Aldington attended Dover College and the University of London. Aldington was good at languages, and mastered French, Italian, Latin, and ancient Greek. He then went on to become a sports journalist and started publishing poetry in British journals. Soon he was associating with the likes of William Butler Yeats and Walter de la Mare.In 1911 Aldington met society hostess Brigit Patmore, who introduced him to American poets Ezra Pound and Hilda Doolittle, who published as H.D, and whom he married two years later. In 1914, the American poet Amy Lowell introduced him to writer D.H. Lawrence. T. S. Eliot was also acquainted with Aldington.

Aldington joined the Army in June 1916 and was sent to the front in December, where he dug graves. By the end of the war, he had become a signals officer and temporary captain. He was demobilised in February 1919.

Aldington found the lice, cold, mud and unsanitary conditions of a soldier's life degrading, but he managed to write poems, essays, and begin work on Death of a Hero, a semiautobiographical novel while still overseas. His encounters with gas on the front affected him for the rest of his life.

Aldington had difficulty returning to his former life after the war. He felt distant from his poet friends who had not undergone the tortuous life of a soldier, and felt they didn’t understand what he had gone through. Although published four volumes of poetry, Images of War and Images of Desire in 1919, Exile and Other Poems in 1923, and Roads to Glory in 1930, he never regained his prewar confidence in his own talent as a poet. He quit writing poetry entirely after suffering a nervous breakdown in 1925. His marriage also suffered, and he divorced his wife in 1938.

Like many American writers during this period, Aldington went into self-imposed exile. He moved to Paris in 1928.

In 1955 Aldington published a biography of T. E. Lawrence that caused a scandal by making public Lawrence's illegitimacy and homosexuality. His own reputation never recovered after he attacked the popular hero as a liar, a charlatan and an "impudent mythomaniac." Another English Poet from WWI, Robert Graves called Aldington "a bitter, bedridden, leering, asthmatic, elderly hangman-of-letters." Many wonder if he was still suffering from his trauma in the trenches.

Aldington died on July 27, 1962, shortly after his seventieth birthday.

Trench Idyll

We sat together in the trench,

He on a lump of frozen earth

Blown in the night before,

I on an unexploded shell;

And smoked and talked, like exiles,

Of how pleasant London was,

Its women, restaurants, night clubs, theatres,

How at that very hour

The taxi cabs were taking folk to dine …

Then we sat silent for a while

As a machine gun swept the parapet.

He said:

“I’ve been here on and off two years

And only seen one man killed.”

“That’s odd.”

“The bullet hit him in the throat;

He fell in a heap on the fire-step,

And called out ‘My God! dead!'”

“Good Lord, how terrible!”

“Well, as to that, the nastiest job I’ve had

Was last year on this very front

Taking the discs at night from men

Who’d hung for six months on the wire

Just over there.

The worst of all was

They fell to pieces at a touch,

Thank God we couldn’t see their faces;

They had gas helmets on …”

I shivered:

“It’s rather cold here, sir; suppose we move?”

This is one of a series of blogs on the poets of World War 1 written by Jennifer Bohnhoff, an author who lives in the mountains of central New Mexico. Her WWI Novel, A Blaze of Poppies, is available in ebook and paperback.

This is one of a series of blogs on the poets of World War 1 written by Jennifer Bohnhoff, an author who lives in the mountains of central New Mexico. Her WWI Novel, A Blaze of Poppies, is available in ebook and paperback.

Published on October 12, 2021 23:00

October 9, 2021

November 11, 1918

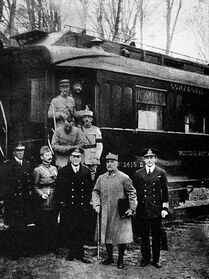

As far as most people are concerned, World War I ended at 11 am. Paris time on November 11, 1918. That is, when the Armistice of Compiègne, which was signed in a railcar at Le Francport, near the French town of Compiègne earlier that morning, took affect.

As far as most people are concerned, World War I ended at 11 am. Paris time on November 11, 1918. That is, when the Armistice of Compiègne, which was signed in a railcar at Le Francport, near the French town of Compiègne earlier that morning, took affect. The war had been winding down for a while already. Russia had left the war in March, 1918, when they agreed to the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, in which they turned over Finland, the Baltic provinces, parts of Poland and Ukraine to the Central Powers. Other armistices had taken Bulgaria, the Ottoman Empire and the Austro-Hungarian Empire out of the fighting.

The signing of the Armistice de Compiègne marked a victory for the Allies and a defeat, although not formally a surrender, for Germany. The terms of were largely written by the Allied Supreme Commander, French Marshal Ferdinand Foch. They included the cessation of hostilities on the Western Front, the withdrawal of German forces from west of the Rhine, and Allied occupation of the Rhineland and bridgeheads further east. All infrastructure in Germany was to be preserved for Allied use, and aircraft, warships, and military materiel were to be surrendered. Although Allied prisoners of war and interned civilians were to be released, the treaty did not specify the release of German prisoners, eventual reparations, and the naval blockade of Germany was not to be lifted.

The signing of the Armistice de Compiègne marked a victory for the Allies and a defeat, although not formally a surrender, for Germany. The terms of were largely written by the Allied Supreme Commander, French Marshal Ferdinand Foch. They included the cessation of hostilities on the Western Front, the withdrawal of German forces from west of the Rhine, and Allied occupation of the Rhineland and bridgeheads further east. All infrastructure in Germany was to be preserved for Allied use, and aircraft, warships, and military materiel were to be surrendered. Although Allied prisoners of war and interned civilians were to be released, the treaty did not specify the release of German prisoners, eventual reparations, and the naval blockade of Germany was not to be lifted.

Although the Armistice was officially signed at 5:45 a.m., it did not come into effect until 11am. This was to allow time for the news to reach combatants. There is no reason why 11am was chosen except for the symmetry of the numbers. Fighting continued in many sections of the front right up until the appointed hour, resulting in 10,944 casualties. 2,738 men died on the last day of the war. This led to controversy after the war. In the United States, Congress opened an investigation to find out why and if blame should be placed on the leaders of the American Expeditionary Forces. In France, many graves of French soldiers who died on 11 November were backdated to 10 November.

The author's husband looking into the restored train car. It is now kept in a dark room to preserve it. One reason the fighting continued was that many Allies didn’t trust that the Armistice would last, and wished to be in the most favorable position should fighting resume. Some artillery units reportedly continued to fire on German targets so they wouldn’t have to haul away their spare ammunition. Battery 4 of the US Navy fired its last shot long-range 14-inch railway gun from the Verdun area at 10:57:30 a.m., timed to land far behind the German front line just before the Armistice was scheduled to begin.

The author's husband looking into the restored train car. It is now kept in a dark room to preserve it. One reason the fighting continued was that many Allies didn’t trust that the Armistice would last, and wished to be in the most favorable position should fighting resume. Some artillery units reportedly continued to fire on German targets so they wouldn’t have to haul away their spare ammunition. Battery 4 of the US Navy fired its last shot long-range 14-inch railway gun from the Verdun area at 10:57:30 a.m., timed to land far behind the German front line just before the Armistice was scheduled to begin.When 11a.m. finally did arrive, the guns fell silent along most of the line. In some places, men on both sides laid down their arms, crossed the line, and shook hands. In other places, there was cheering and applause. But in general, soldiers were too tired and too wary that this was an illusion to do anything to celebrate. One British corporal reported: "...the Germans came from their trenches, bowed to us and then went away. That was it. There was nothing with which we could celebrate, except cookies."

The Peace Memorial at Compiègne Because this was a world-wide war, news of the armistice did not reach all battlefields at once. The King's African Rifles, fighting in what was then called Northern Rhodesia and is in today's Zambia, did not hear that the war was over for two weeks. When they did, the British commanders contacted the Germans and they their own armistice ceremony.

The Peace Memorial at Compiègne Because this was a world-wide war, news of the armistice did not reach all battlefields at once. The King's African Rifles, fighting in what was then called Northern Rhodesia and is in today's Zambia, did not hear that the war was over for two weeks. When they did, the British commanders contacted the Germans and they their own armistice ceremony.Although the armistice ended the fighting on the Western Front, the war did not actually, officially conclude until much later. The armistice that began on November 11 lasted until December 13, when the parties involved renegotiated terms that held until January 16, 1919. The peace was delayed two more times before June 28, when the Treaty of Versailles, was finally signed. The treaty was ratified, and the world was finally officially at peace on January 10, 1920.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is the author of A Blaze of Poppies, a novel set in New Mexico and France during World War 1.

Published on October 09, 2021 23:00

October 5, 2021

Siegfried Sassoon

Siegfried Sassoon was born into a wealthy Jewish family who were sometimes referred to as the “Rothschilds of the East” because their fortune was made in India. Before the war, he lived the leisurely life of a cultivated country gentleman, writing poetry that is not considered very good, and fox hunting.

Siegfried Sassoon was born into a wealthy Jewish family who were sometimes referred to as the “Rothschilds of the East” because their fortune was made in India. Before the war, he lived the leisurely life of a cultivated country gentleman, writing poetry that is not considered very good, and fox hunting.When the war began, Sassoon joined the Royal Welsh Fusiliers. He saw action in France in late 1915 and received a Military Cross for bringing back a wounded soldier during heavy fire.

After Sassoon was wounded in action, he wrote an open letter of protest to the war department in which he refused to fight any more. Sassoon thought his letter would lead to a court-martial, but friend and fellow poet Robert Graves successfully argued that Sassoon was suffering from shell-shock and needed medical treatment. In 1917, Sassoon was hospitalized.

Sassoon's war poems are angry and avoid sentimentality. Many of his detractors argue that his refusal to support the war effort was unpatriotic, but Sassoon's shockingly realistic depictions of war captured the feelings of soldiers and a public grown tired of the carnage.

After the war, Sassoon became involved in Labour Party politics, lectured on pacifism, wrote a trilogy of autobiographical novels, and published a critical biography of Victorian novelist and poet George Meredith. In 1957, Sassoon became a Catholic and began writing religious poems. He died in 1967 from stomach cancer. Attack

by Siegfried Sassoon

At dawn the ridge emerges massed and dun

In the wild purple of the glow'ring sun,

Smouldering through spouts of drifting smoke that shroud

The menacing scarred slope; and, one by one,

Tanks creep and topple forward to the wire.

The barrage roars and lifts. Then, clumsily bowed

With bombs and guns and shovels and battle-gear,

Men jostle and climb to, meet the bristling fire.

Lines of grey, muttering faces, masked with fear,

They leave their trenches, going over the top,

While time ticks blank and busy on their wrists,

And hope, with furtive eyes and grappling fists,

Flounders in mud. O Jesus, make it stop!

Jennifer Bohnhoff's novel, A Blaze of Poppies is set in southern New Mexico and in the trenches of World War I France.

Jennifer Bohnhoff's novel, A Blaze of Poppies is set in southern New Mexico and in the trenches of World War I France.

Published on October 05, 2021 23:00

October 2, 2021

The Jeffery: Modern Mule

Early in the 20th century, the U.S. Army decided that mechanization was the wave of the future. In 1912, it requested proposals for a truck that could take the place of the four-mule teams used to haul standard one-and-a-half-ton loads of equipment, supplies and men. One of the companies that responded was the Thomas B. Jeffery Company, in Kenosha, Wisconsin.

The Jeffery Company began their development by buying and studying a truck developed by The Four Wheel Drive Auto Company (FWD). They soon sold it and began their own design from scratch. By July 1913, they had developed a prototype of the Jeffery Quad that was ready for public demonstration of its capabilities.

The Jeffery designed a four-wheel-drive truck, known as the "Quad" or "Jeffery Quad" that was sturdier than anything that had come before it. It had four-wheel brakes and an innovative four-wheel steering system that allowed the rear wheels to track the front wheels around turns. This meant that the rear wheels did not have to dig new "ruts" on muddy curves. A very high ground clearance allowed it to drive through mud up to its hubcaps. The wheels were the same as those used on locomotive cars, with the addition of a thin rubber tire. When they were used near train tracks, the tire could be taken off and the Quad set on the rails.

The Jeffery designed a four-wheel-drive truck, known as the "Quad" or "Jeffery Quad" that was sturdier than anything that had come before it. It had four-wheel brakes and an innovative four-wheel steering system that allowed the rear wheels to track the front wheels around turns. This meant that the rear wheels did not have to dig new "ruts" on muddy curves. A very high ground clearance allowed it to drive through mud up to its hubcaps. The wheels were the same as those used on locomotive cars, with the addition of a thin rubber tire. When they were used near train tracks, the tire could be taken off and the Quad set on the rails.

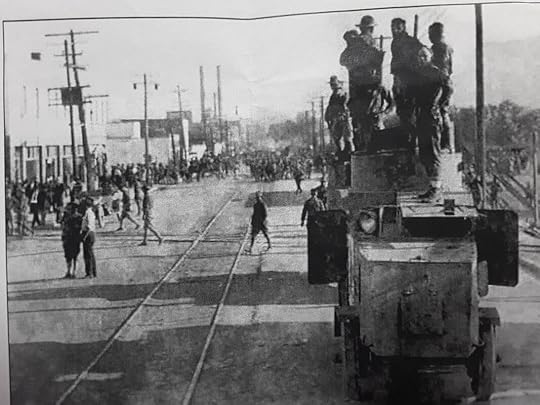

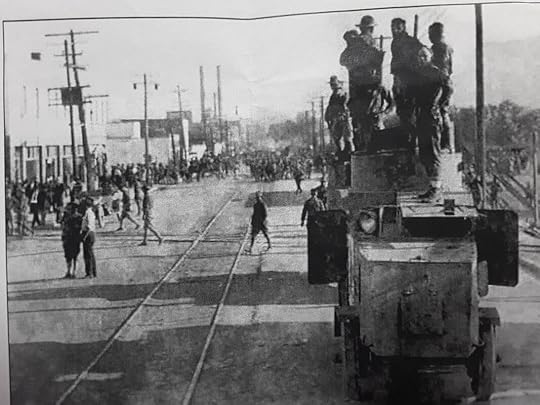

Quads on a muddy road in Mexico Jeffery Quads first saw service during the Army’s 1916 Punitive Expedition through Mexico. General John “Blackjack” Pershing used a mix of Quads and mule-driven wagons to transport troops and supplies. He also had two Quads that had been specially modified with armor.

Quads on a muddy road in Mexico Jeffery Quads first saw service during the Army’s 1916 Punitive Expedition through Mexico. General John “Blackjack” Pershing used a mix of Quads and mule-driven wagons to transport troops and supplies. He also had two Quads that had been specially modified with armor.

Armored Jeffery Quad at Pancho Villa State Park, New Mexico The Jeffery Quad Armored Truck, also known as Armored Car No. 1, was not the first armored car -- several National Guard units had already had their own designed – but it was the first one built by the U.S. Government specifically for Army’s use. It was designed to support combat forces. It had armored plate made by the Bethlehem Steel Corporation and two manually operated turrets. Three light machine guns, a Bennett-Merier and 2 Colt “Potato Diggers,” provided the firepower. Neither vehicle was reported to have seen military action.

Armored Jeffery Quad at Pancho Villa State Park, New Mexico The Jeffery Quad Armored Truck, also known as Armored Car No. 1, was not the first armored car -- several National Guard units had already had their own designed – but it was the first one built by the U.S. Government specifically for Army’s use. It was designed to support combat forces. It had armored plate made by the Bethlehem Steel Corporation and two manually operated turrets. Three light machine guns, a Bennett-Merier and 2 Colt “Potato Diggers,” provided the firepower. Neither vehicle was reported to have seen military action.

When Pershing led the Army overseas, he brought the Quad with him. Its ability to negotiate France and Belgium’s muddy, rough, and unpaved roads made it the workhorse of the Allied Expeditionary Force.

When Pershing led the Army overseas, he brought the Quad with him. Its ability to negotiate France and Belgium’s muddy, rough, and unpaved roads made it the workhorse of the Allied Expeditionary Force.

Quads were also used by the United States Marine Corps from 1915 through 1917, during their occupation of Haiti, and of the Dominican Republic. Marines in Santo Domingo, 1916 Approximately 11,500 Jeffery and Nash Quads were built between 1913 and 1919. They continued to be produced until 1928, but their reliability and ability to negotiate difficult terrain that challenged more modern trucks meant that civilians to use these slow, but steady workers until into the 1950s.

Marines in Santo Domingo, 1916 Approximately 11,500 Jeffery and Nash Quads were built between 1913 and 1919. They continued to be produced until 1928, but their reliability and ability to negotiate difficult terrain that challenged more modern trucks meant that civilians to use these slow, but steady workers until into the 1950s.

Jennifer Bohnhoff writes historical novels from her home high up in the mountains of central New Mexico. A Blaze of Poppies: A Novel About New Mexico and World War I will be published in October 2021.

The Jeffery Company began their development by buying and studying a truck developed by The Four Wheel Drive Auto Company (FWD). They soon sold it and began their own design from scratch. By July 1913, they had developed a prototype of the Jeffery Quad that was ready for public demonstration of its capabilities.

The Jeffery designed a four-wheel-drive truck, known as the "Quad" or "Jeffery Quad" that was sturdier than anything that had come before it. It had four-wheel brakes and an innovative four-wheel steering system that allowed the rear wheels to track the front wheels around turns. This meant that the rear wheels did not have to dig new "ruts" on muddy curves. A very high ground clearance allowed it to drive through mud up to its hubcaps. The wheels were the same as those used on locomotive cars, with the addition of a thin rubber tire. When they were used near train tracks, the tire could be taken off and the Quad set on the rails.

The Jeffery designed a four-wheel-drive truck, known as the "Quad" or "Jeffery Quad" that was sturdier than anything that had come before it. It had four-wheel brakes and an innovative four-wheel steering system that allowed the rear wheels to track the front wheels around turns. This meant that the rear wheels did not have to dig new "ruts" on muddy curves. A very high ground clearance allowed it to drive through mud up to its hubcaps. The wheels were the same as those used on locomotive cars, with the addition of a thin rubber tire. When they were used near train tracks, the tire could be taken off and the Quad set on the rails. Quads on a muddy road in Mexico Jeffery Quads first saw service during the Army’s 1916 Punitive Expedition through Mexico. General John “Blackjack” Pershing used a mix of Quads and mule-driven wagons to transport troops and supplies. He also had two Quads that had been specially modified with armor.

Quads on a muddy road in Mexico Jeffery Quads first saw service during the Army’s 1916 Punitive Expedition through Mexico. General John “Blackjack” Pershing used a mix of Quads and mule-driven wagons to transport troops and supplies. He also had two Quads that had been specially modified with armor. Armored Jeffery Quad at Pancho Villa State Park, New Mexico The Jeffery Quad Armored Truck, also known as Armored Car No. 1, was not the first armored car -- several National Guard units had already had their own designed – but it was the first one built by the U.S. Government specifically for Army’s use. It was designed to support combat forces. It had armored plate made by the Bethlehem Steel Corporation and two manually operated turrets. Three light machine guns, a Bennett-Merier and 2 Colt “Potato Diggers,” provided the firepower. Neither vehicle was reported to have seen military action.

Armored Jeffery Quad at Pancho Villa State Park, New Mexico The Jeffery Quad Armored Truck, also known as Armored Car No. 1, was not the first armored car -- several National Guard units had already had their own designed – but it was the first one built by the U.S. Government specifically for Army’s use. It was designed to support combat forces. It had armored plate made by the Bethlehem Steel Corporation and two manually operated turrets. Three light machine guns, a Bennett-Merier and 2 Colt “Potato Diggers,” provided the firepower. Neither vehicle was reported to have seen military action. When Pershing led the Army overseas, he brought the Quad with him. Its ability to negotiate France and Belgium’s muddy, rough, and unpaved roads made it the workhorse of the Allied Expeditionary Force.

When Pershing led the Army overseas, he brought the Quad with him. Its ability to negotiate France and Belgium’s muddy, rough, and unpaved roads made it the workhorse of the Allied Expeditionary Force.Quads were also used by the United States Marine Corps from 1915 through 1917, during their occupation of Haiti, and of the Dominican Republic.

Marines in Santo Domingo, 1916 Approximately 11,500 Jeffery and Nash Quads were built between 1913 and 1919. They continued to be produced until 1928, but their reliability and ability to negotiate difficult terrain that challenged more modern trucks meant that civilians to use these slow, but steady workers until into the 1950s.

Marines in Santo Domingo, 1916 Approximately 11,500 Jeffery and Nash Quads were built between 1913 and 1919. They continued to be produced until 1928, but their reliability and ability to negotiate difficult terrain that challenged more modern trucks meant that civilians to use these slow, but steady workers until into the 1950s.Jennifer Bohnhoff writes historical novels from her home high up in the mountains of central New Mexico. A Blaze of Poppies: A Novel About New Mexico and World War I will be published in October 2021.

Published on October 02, 2021 23:00

September 29, 2021

The Wrist Watch Man

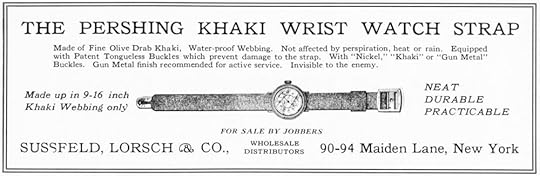

At the beginning of the twentieth century, wrist watches were feminine novelties worn by trendy women. By 1920, they had become standard military issue and symbols of masculine virility. This change came about because of the need to synchronize artillery and infantry during the First World War. Perhaps no one captured this change better than Edgar Albert Guest, the people’s poet whose poems filled the papers throughout the war.

The Wrist Watch Man He is marching dusty highways and he's riding bitter trails,

He is marching dusty highways and he's riding bitter trails,

His eyes are clear and shining and his muscles hard as nails.

He is wearing Yankee khaki and a healthy coat of tan,

And the chap that we are backing is the Wrist Watch Man.

He's no parlour dude, a-prancing, he's no puny pacifist,

And it's not for affectation there's a watch upon his wrist.

He's a fine two-fisted scrapper, he is pure American,

And the backbone of the nation is the Wrist Watch Man.

He is marching with a rifle, he is digging in a trench,

He is swapping English phrases with a poilu for his French;

You will find him in the navy doing anything he can,

For at every post of duty is the Wrist Watch Man.

Oh, the time was that we chuckled at the soft and flabby chap

Who wore a little wrist watch that was fastened with a strap.

But the chuckles all have vanished, and with glory now we scan

The courage and the splendor of the Wrist Watch Man.

He is not the man we laughed at, not the one who won our jeers,

He's the man that we are proud of, he's the man that owns our cheers;

He's the finest of the finest, he's the bravest of the clan,

And I pray for God's protection for our Wrist Watch Man. Jennifer Bohnhoff lives in the mountains of central New Mexico, where she writes historical fiction and spends way too much time finding interesting bits of history on the internet. You can read more about her and her books on her website, jenniferbohnhoff.com

Jennifer Bohnhoff lives in the mountains of central New Mexico, where she writes historical fiction and spends way too much time finding interesting bits of history on the internet. You can read more about her and her books on her website, jenniferbohnhoff.com

The Wrist Watch Man

He is marching dusty highways and he's riding bitter trails,

He is marching dusty highways and he's riding bitter trails,His eyes are clear and shining and his muscles hard as nails.

He is wearing Yankee khaki and a healthy coat of tan,

And the chap that we are backing is the Wrist Watch Man.

He's no parlour dude, a-prancing, he's no puny pacifist,

And it's not for affectation there's a watch upon his wrist.

He's a fine two-fisted scrapper, he is pure American,

And the backbone of the nation is the Wrist Watch Man.

He is marching with a rifle, he is digging in a trench,

He is swapping English phrases with a poilu for his French;

You will find him in the navy doing anything he can,

For at every post of duty is the Wrist Watch Man.

Oh, the time was that we chuckled at the soft and flabby chap

Who wore a little wrist watch that was fastened with a strap.

But the chuckles all have vanished, and with glory now we scan

The courage and the splendor of the Wrist Watch Man.

He is not the man we laughed at, not the one who won our jeers,

He's the man that we are proud of, he's the man that owns our cheers;

He's the finest of the finest, he's the bravest of the clan,

And I pray for God's protection for our Wrist Watch Man.

Jennifer Bohnhoff lives in the mountains of central New Mexico, where she writes historical fiction and spends way too much time finding interesting bits of history on the internet. You can read more about her and her books on her website, jenniferbohnhoff.com

Jennifer Bohnhoff lives in the mountains of central New Mexico, where she writes historical fiction and spends way too much time finding interesting bits of history on the internet. You can read more about her and her books on her website, jenniferbohnhoff.com

Published on September 29, 2021 23:00

September 25, 2021

World War 1 and the Development of the Wrist Watch

World War 1 changed society. One of the lesser known ways was the development of portable timepieces.

World War 1 changed society. One of the lesser known ways was the development of portable timepieces.At the beginning of the twentieth century, when most people were out and about, they got the time from church bells and factory whistles. Many had mantel or wall clocks in their homes. Alarm clocks had been patented in the middle of the nineteenth century and were being used increasingly. But outside the home, people went without a watch. There were two exceptions to this. Gentlemen and people whose jobs relied on timeliness, such as railroad conductors, carried pocket watches. Women who wanted to appear modern hung petite pendant watches about their necks, pinned tiny, brooch-like watches to their blouses, or bound dainty watches to their wrists. These small watches were not very accurate and were more decorative than precise and made small watches appear too feminine for most men to consider wearing.

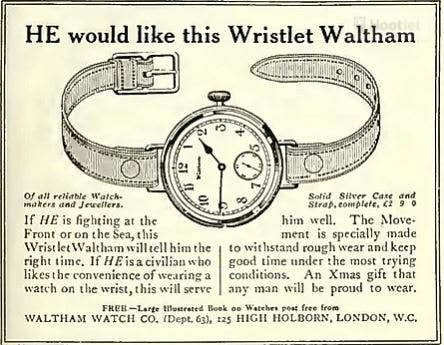

The Great War changed that perception. It was one of the first times that artillery and infantry synchronized their movements over long distances. Some of the biggest guns were 75 miles from the front they were shelling, and in order to not rain havoc on their own troops, they had to coordinate who was where to a greater precision than “at dawn.” The phrase “synchronize your watches” was developed. The concept of the creeping artillery barrage, where artillery laid down a curtain of fire that the infantry was supposed to follow close behind, made precise timekeeping imperative. It was clear that men at war needed watches. But what kind of watch was best? A man crouching in a trench or exchanging gunfire with the enemy, simply couldn’t pull a watch from his pocket, open the case, and check the time. He needed a quicker solution. Thus, the wristwatch overcame its effeminate image and become a practical necessity. By 1916, a quarter of all soldiers wore wristwatches. In 1917, the British War Department began issuing wristwatches to all combatants.

The Great War changed that perception. It was one of the first times that artillery and infantry synchronized their movements over long distances. Some of the biggest guns were 75 miles from the front they were shelling, and in order to not rain havoc on their own troops, they had to coordinate who was where to a greater precision than “at dawn.” The phrase “synchronize your watches” was developed. The concept of the creeping artillery barrage, where artillery laid down a curtain of fire that the infantry was supposed to follow close behind, made precise timekeeping imperative. It was clear that men at war needed watches. But what kind of watch was best? A man crouching in a trench or exchanging gunfire with the enemy, simply couldn’t pull a watch from his pocket, open the case, and check the time. He needed a quicker solution. Thus, the wristwatch overcame its effeminate image and become a practical necessity. By 1916, a quarter of all soldiers wore wristwatches. In 1917, the British War Department began issuing wristwatches to all combatants.

The first trench watches, or "wristlets" as they were known, looked like pocket watches mounted on a leather bands. They quickly changed to meet the demands of trench warfare.

The first trench watches, or "wristlets" as they were known, looked like pocket watches mounted on a leather bands. They quickly changed to meet the demands of trench warfare. Hinged covers protected crystals on pocket watches. Trench watches often had hinged cages that didn’t obscure the numerals. These soon became fixed.

The creation of luminous dials helped soldiers see the time in dim light.

One thing that carried over from pocket watches was the engraving of names, titles, and places on the back cases of watches. Although dog tags had been implemented during WWI, a personalized engraving could serve as a redundancy system for identification. Different branches of service issued their men different brands and makes of watches. Other watches were gifts from family or employers. Many of the World War 1 watches that are still on the market bear interesting engravings on the back.

One thing that carried over from pocket watches was the engraving of names, titles, and places on the back cases of watches. Although dog tags had been implemented during WWI, a personalized engraving could serve as a redundancy system for identification. Different branches of service issued their men different brands and makes of watches. Other watches were gifts from family or employers. Many of the World War 1 watches that are still on the market bear interesting engravings on the back.  Roughly 1.8 million American soldiers served in France during WWI. Pictures of them in their handsome, trim uniforms, with their watches prominently displayed, helped the general public see wrist watches as symbols of masculinity and bravado, reflecting the spirit of a soldier. The fact that pilots, the most glamorous of all fighting men, started wearing using wristwatches gave wristwatches even more moxie with the American public. By 1930 the ratio of wrist watches to pocket watches was 50 to 1.

Roughly 1.8 million American soldiers served in France during WWI. Pictures of them in their handsome, trim uniforms, with their watches prominently displayed, helped the general public see wrist watches as symbols of masculinity and bravado, reflecting the spirit of a soldier. The fact that pilots, the most glamorous of all fighting men, started wearing using wristwatches gave wristwatches even more moxie with the American public. By 1930 the ratio of wrist watches to pocket watches was 50 to 1.  Was the rise of the wrist watch a blip in technological fashion? Smartwatches and cell phones have been taking market share from mechanical watches for a decade now. Could it be that the wrist watch will go the way of 8-track tapes? Or are wrist watches here to stay? Excuse the pun, but only time will tell.

Was the rise of the wrist watch a blip in technological fashion? Smartwatches and cell phones have been taking market share from mechanical watches for a decade now. Could it be that the wrist watch will go the way of 8-track tapes? Or are wrist watches here to stay? Excuse the pun, but only time will tell.

Jennifer Bohnhoff's novel about World War I, A Blaze of Poppies, comes out October 22, 2021. There's still time to preorder the ebook on Amazon, or preorder a signed copy directly from the author.

Jennifer Bohnhoff's novel about World War I, A Blaze of Poppies, comes out October 22, 2021. There's still time to preorder the ebook on Amazon, or preorder a signed copy directly from the author.

Published on September 25, 2021 23:00

September 21, 2021

Two Fusiliers and Two Poets

Robert Graves was born in Wimbledon in 1895, the third child of ten. His father was an Irish poet and his mother was the great-niece of a famous German historian. Graves learned to box because his half-German ancestry made him the target of bullies.

Robert Graves was born in Wimbledon in 1895, the third child of ten. His father was an Irish poet and his mother was the great-niece of a famous German historian. Graves learned to box because his half-German ancestry made him the target of bullies. Graves published his first poems in 1911, when he was a student at The Charterhouse School. One of the young masters there was George Mallory, who introduced Graves to the works of George Bernard Shaw, Rupert Brooke, and John Edward Masefield, and took him climbing. Mallory was later to die on the 1924 Everest expedition.

In 1914, Graves was supposed to go to St John’s College, Oxford. Instead, he enlisted in the army joining the Royal Welch Fusiliers. He was posted to France in May 1915, and fought in the Battle of Loos in September that year. Two months later, he met the poet Siegfried Sassoon, a fellow-officer in the Royal Welch Fusiliers. “Two Fusiliers”, is a celebration of that friendship.

In July of 1916, Graves was wounded by a shell at High Wood, in the Somme. His colonel believed that Graves' injuries would result in his death, and wrote a condolence letter to Graves’s parents. The Times reported that Graves had died of his wounds in their August 4, 1916 edition. This “death” and “rebirth”, which occurred close to his 21st birthday, had a profound effect on Graves’s life and writing.

Graves' bestselling war memoir, Good-bye to All That, was published in 1929 and caused a rift between him and Sassoon and ultimately between himself and his country. He moved to Deià in Majorca, where he lived until his death in 1985 with the exception of two periods, during the Spanish Civil War and the Second World War, when he was evacuated.

Graves is not only known as a poet and mythologist, but as a novelist. His I, Claudius books were turned into a miniseries for PBS.

Two Fusiliers

BY ROBERT GRAVES And have we done with War at last?

Well, we've been lucky devils both,

And there's no need of pledge or oath

To bind our lovely friendship fast,

By firmer stuff

Close bound enough.

By wire and wood and stake we're bound,

By Fricourt and by Festubert,

By whipping rain, by the sun's glare,

By all the misery and loud sound,

By a Spring day,

By Picard clay.

Show me the two so closely bound

As we, by the wet bond of blood,

By friendship blossoming from mud,

By Death: we faced him, and we found

Beauty in Death,

In dead men, breath. Jennifer Bohnhoff's World War I historical novel A Blaze of Poppies will be published in October 2021 and is available for preorder on Amazon.

Published on September 21, 2021 23:00

September 18, 2021

Funny Fragments from the Front

Bairnsfather in 1918 Most Americans are familiar with the art of Bill Mauldin, the cartoonist who captured the spirit of American GIs during the Second World War.

Bairnsfather in 1918 Most Americans are familiar with the art of Bill Mauldin, the cartoonist who captured the spirit of American GIs during the Second World War.The British, First World War equivalent was a brilliant cartoonist named Charles Bruce Bairnsfather.

Bairnsfather's cartoons were featured in a weekly "Fragments from France," serial published in The Bystander magazine.

His best-known character, Old Bill, became the face of the British soldier stuck in the trenches. Bairnsfather was born July 9, 1887 at Muree, in a part of British India that is now in Pakistan. His father was a Major in the Indian Staff Corps, and both his parents were great-grandchildren of a Baronet. He was brought to England when he was 8 years old so that he could be educated. His plans for a career in the military were thwarted when he failed his entrance exams to Sandhurt and Woolwich Military Academies. After a brief stint in the Cheshire Regiment, he resigned to become an artist.

When war broke out in 1914, Bairnsfather joined the Royal Warwickshire Regiment as a second lieutenant. He served in a machine gun unit in France until 1915, when he was hospitalized with shellshock and hearing damage sustained during the Second Battle of Ypres.

When war broke out in 1914, Bairnsfather joined the Royal Warwickshire Regiment as a second lieutenant. He served in a machine gun unit in France until 1915, when he was hospitalized with shellshock and hearing damage sustained during the Second Battle of Ypres. He was then posted to the 34th Division headquarters on Salisbury Plan, in southern England. Here, he he developed his humorous series for the Bystander about life in the trenches.

Bairnsfather's most famous character was "Old Bill", an older, experienced soldier with an enormous moustache. The best remembered of his cartoons shows Bill with another trooper in a muddy shell hole with shells whizzing all around. The other trooper is grumbling and Bill says, "Well, If you knows of a better 'ole, go to it." This cartoon is included in the collection Fragments From France, published in 1914.

Bairnsfather's cartoon were immensely popular with the troops and created massive sales increases for the Bystander. However, the general public , initially objected to the cartoons as "vulgar caricatures". As the war progressed and romantic notions of war faded, he became more popular. The cartoons did so much to raise morale that Bairnsfather got a promotion and an appointment to the War Office to draw similar cartoons for other Allies forces.

When the Second World War broke out, Bairnsfather became the official cartoonist to the American forces in Europe. He worked from England, contributing cartoons for Stars and Stripes and Yank. He even drew some nose art for aircraft on American bases in England.

When the Second World War broke out, Bairnsfather became the official cartoonist to the American forces in Europe. He worked from England, contributing cartoons for Stars and Stripes and Yank. He even drew some nose art for aircraft on American bases in England. When Bairnsfather died of bladder cancer on September 29, 1959, his obituary in the Times noted that he was "fortunate in possessing a talent … which suited almost to the point of genius one particular moment and one particular set of circumstances; and he was unfortunate in that he was never able to adapt, at all happily, his talent to new times and new circumstances." He may never have been able to extend his talent beyond the Great War, but he gave voice and a face to those who fought in the trenches. Jennifer Bohnhoff's World War I novel A Blaze of Poppies will be published on October 22, 2021 and is now available for preorder on Amazon. Every Friday from here through Veteran's Day she will be featuring a page from a copy of Fragments from France that she owns on her Facebook page. and will be giving the copy away to someone on her email list of friends, fans and family during the month-long celebration.

Published on September 18, 2021 23:00