Jennifer Bohnhoff's Blog, page 27

March 21, 2021

Buffalo Soldiers

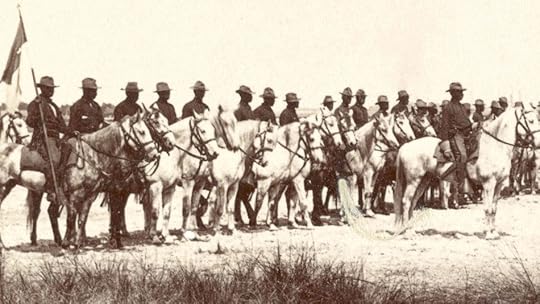

In 1866, right after the close of the Civil War, Congress created six (later consolidated to four) regiments of African-American soldiers. These units, the 9th and 10th Cavalry, and the 24th and 25th Infantry, quickly became known as “The Buffalo Soldiers.”

In 1866, right after the close of the Civil War, Congress created six (later consolidated to four) regiments of African-American soldiers. These units, the 9th and 10th Cavalry, and the 24th and 25th Infantry, quickly became known as “The Buffalo Soldiers.”

There are at least three different stories concerning how these units came by their nickname.

There are at least three different stories concerning how these units came by their nickname. The most plausible in my mind is that the Plains Indians, who fought the Buffalo Soldiers, thought that their dark skin and black curly hair looked much like the coloring and fur of the buffalo.

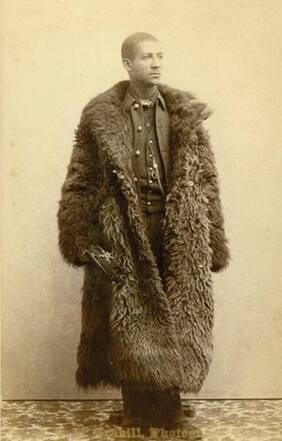

A second theory is that they were named after the thick buffalo-hide coats the troops wore during the winter.

A third theory is that they were awarded the name because of the ferocity and bravery of their actions.

Regardless of how the name came to be, the soldiers themselves were proud of it and considered it high praise since buffalo were deeply respected by the Native peoples of the Great Plains. Eventually, the buffalo became the image on the 10th Cavalry's regimental crest.

Regardless of how the name came to be, the soldiers themselves were proud of it and considered it high praise since buffalo were deeply respected by the Native peoples of the Great Plains. Eventually, the buffalo became the image on the 10th Cavalry's regimental crest.At first, regiments of Buffalo Soldiers faced a lot of racial prejudice. Because many whites didn't want to see armed black soldiers in or near their communities, the Buffalo Soldiers were assigned to forts west of the Mississippi River, where they supported the nation's westward expansion by protecting settlers, building roads and other infrastructure, and guarding the U.S. mail. They were also involved in many of the military campaigns of the Indian Wars. They served with distinction, earning an impressive 18 Medals of Honor during this period.

Since there were no African American officers, the units were commanded by whites. Some officers, like George Armstrong Custer, were so opposed to allowing blacks into the Army that they refused to command black regiments even when it cost them promotions. Others, like John Pershing, accepted the command but were branded for it. Pershing got the nickname “Black Jack” for his time commanding the 10th Cavalry. At first, it was given to him derisively, but he managed to turn it into a badge of honor.

Since there were no African American officers, the units were commanded by whites. Some officers, like George Armstrong Custer, were so opposed to allowing blacks into the Army that they refused to command black regiments even when it cost them promotions. Others, like John Pershing, accepted the command but were branded for it. Pershing got the nickname “Black Jack” for his time commanding the 10th Cavalry. At first, it was given to him derisively, but he managed to turn it into a badge of honor.George Jordan, of K Troop, 9th Cavalry Regiment, earned his prestigious medal for repulsing a force of more than 100 Indians while he and his detachment of 25 men were stationed at Fort Tularosa, N. M., and then for holding his ground in an exposed position so that a larger force of Indians could not surround his command in Carrizo Canyon.

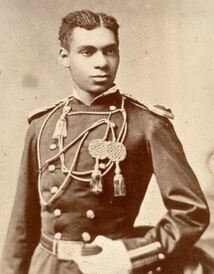

Eventually, the exceptional performance of the Buffalo soldiers led to their advancement into positions of authority. The first black officer to command soldiers in the regular U.S. Army, Henry O. Flipper, was born a slave in Georgia but graduated from West Point Military Academy in 1877, commissioned as a second lieutenant, and was assigned to the 10th Cavalry Regiment. He faced intense resentment from some white officers and became the target of a smear campaign that culminated in a court martial and his dismissal from the Army in 1882. He was posthumously pardoned by President Clinton in 1999.

Eventually, the exceptional performance of the Buffalo soldiers led to their advancement into positions of authority. The first black officer to command soldiers in the regular U.S. Army, Henry O. Flipper, was born a slave in Georgia but graduated from West Point Military Academy in 1877, commissioned as a second lieutenant, and was assigned to the 10th Cavalry Regiment. He faced intense resentment from some white officers and became the target of a smear campaign that culminated in a court martial and his dismissal from the Army in 1882. He was posthumously pardoned by President Clinton in 1999.Buffalo Soldiers continued to serve their country, both in the west and abroad. They helped in the 1892 Johnson County War in Wyoming, which pitted small farmers against wealthy ranchers and a band of hired gunmen. They also fought in the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars, and served along the U.S.-Mexico border and in the Expedition to find Pancho Villa. However, they continued to suffer racism. Woodrow Wilson excluded black regiments from the American Expeditionary Force and placed them under French command. During World War II, most of the 9th and 10th Cavalry Regiments were moved into service roles. The two exceptions were the 92nd Infantry Division, which saw combat during the invasion of Italy, and the 25th Infantry Regiment, which fought in the Pacific. During the Korean War, the last of the segregated U.S. Army regiments were disbanded and their troops integrated into other units.

Published on March 21, 2021 10:42

March 14, 2021

Important Irish-American Women

America has welcomed people from all over the world. During the nineteenth century, a large proportion of these people were from Ireland. In the 1840s, when the Potato Famine was ravaging the Emerald Isle, nearly half of the immigrants to America were Irish, and half of those Irish immigrants were single women.

Many of those newcomers to America entered domestic professions, where working as a maid, cook, nanny, or housekeeper helped them assimilate into American culture. A generation later, Irish women were entering professions at higher rates than any other immigrant group. They became teachers, bookkeepers, typists, journalists, social workers, and nurses. Irish American women represented the majority of public elementary school teachers in Providence, Boston, New York, Chicago, and San Francisco by 1910.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau. about 32 million Americans, or 9.7% of the total population, identifies as being Irish. In honor of Women’s History Month and St. Patrick’s Day, here are four Irish American Women who have made significant contributions, plus a recipe for cookies that will put you into the spirit of the day.. Mother Jones, Labor Agitator Mother Jones, whose real name was Mary Harris Jones, was a tireless advocate for worker’s rights, the end of child labor, and for improved working conditions for miners. She was born in Cork, Ireland in 1837, but was still a child when the Harris family emigrated first to Canada and then to the United States.

Mother Jones, whose real name was Mary Harris Jones, was a tireless advocate for worker’s rights, the end of child labor, and for improved working conditions for miners. She was born in Cork, Ireland in 1837, but was still a child when the Harris family emigrated first to Canada and then to the United States.

Mary Harris married an iron molder named George E Jones in 1861. Six years later, he and all four of their children died in a yellow-fever epidemic. The trade union he had belonged to helped the new widow, leaving a lasting impression on her.

When the great Chicago fire of 1871 destroyed her home and all of her belongings, Mrs. Jones left behind her job as a dressmaker to enter political activism. She joined the Knights of Labor and the Socialist Labor Party and became a full-time union organizer, travelling constantly around Pennsylvania, Ohio, Illinois, Indiana, West Virginia and Colorado as she organized marches, made speeches in the plain language of the working man, and deploying “broom and mop” brigades of workers’ wives to wage war against scabs and strike breakers.

Interestingly, although she believed in racial equality, she did not believe in equality of the sexes and opposed female suffrage. She believed in the traditional family, with a breadwinner husband and a wife who supported him.

Jones cultivated a grandmotherly persona, even lying about her age to appear older than she was. She made a lot of enemies. One district attorney called her the most dangerous woman in the United States. The writer Upton Sinclair called the left-wing firebrand the walking wrath of God. But while she angered many people, she secured valuable nationwide press attention for the causes she championed.

Kay McNulty, Computer Programmer

On February 12, 1921, important events happened to the McNultys of Donegal County, Ireland: Their daughter Kay was born, and the father was arrested for IRA membership. Two years later, when he was finally released from prison, the family left their farm and emigrated to Pennsylvania. The move turned out to be lifechanging for Kay, whose mother encouraged her to do her best “to prove that Irish immigrants could be as good, if not better, than anybody.” While only 37% of girls in Ireland were enrolled in school in 1929, Kay was able earn a scholarship while in High School that allowed her to attend Chestnut Hill College for Women. She graduated with a mathematics degree.

On February 12, 1921, important events happened to the McNultys of Donegal County, Ireland: Their daughter Kay was born, and the father was arrested for IRA membership. Two years later, when he was finally released from prison, the family left their farm and emigrated to Pennsylvania. The move turned out to be lifechanging for Kay, whose mother encouraged her to do her best “to prove that Irish immigrants could be as good, if not better, than anybody.” While only 37% of girls in Ireland were enrolled in school in 1929, Kay was able earn a scholarship while in High School that allowed her to attend Chestnut Hill College for Women. She graduated with a mathematics degree.

When World War II began, the US Army hired Kay as a “computer”, calculating missile trajectories. In 1945, she and five other women were moved to Aberdeen military base in Maryland to developing the processor for a top-secret 30-ton machine called the Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer (ENIAC). Later, she worked at another programming job, which she only discovered later was testing the feasibility of the H-bomb.

In 1948 Kay married a computer developer named John Mauchly. As was usual at the time, she stopped her career. But throughout the time when she raised seven children,

Kay continued, unpaid and unnoticed, to program the new computers that her husband was developing.

It wasn’t until decades later, in 1997, that McNulty and the other five ENIAC women were inducted into the Women in Technology International Hall of Fame.

Ella Fitzgerald, Singer

Ella Fitzgerald may not look Irish, but when she acknowledged her heritage, the people of Ireland were happy to have her. The First Lady of Song was born to a woman who was African American/Cherokee Indian. Her father, who was Irish enough to have a family crest, never married her mother, and abandoned the family when Ella was quite young. During a singing tour of Ireland in the 1960s, Fitzgerald told reporters that she had the family crest in her home, and the authorities used a special stamp on her passport to acknowledge her heritage.

Ella Fitzgerald may not look Irish, but when she acknowledged her heritage, the people of Ireland were happy to have her. The First Lady of Song was born to a woman who was African American/Cherokee Indian. Her father, who was Irish enough to have a family crest, never married her mother, and abandoned the family when Ella was quite young. During a singing tour of Ireland in the 1960s, Fitzgerald told reporters that she had the family crest in her home, and the authorities used a special stamp on her passport to acknowledge her heritage.

Fitzgerald has a voice that continues to amaze and entertain listeners years after her death. She remains famous for her scat singing and her associations with other jazz greats such as Louie Armstrong and Duke Ellington. Her musical career spanned six decades and several genres, though she remained a jazz singer at heart.

Ella could be considered a symbol of the mixing of cultures that is distinctly American

Eileen Marie Collins, AstronauT

Eileen Marie Collins was the daughter of Irish immigrants. She became interested in space flight at a young age. She began to pursue her dream by joining the air force and becoming a test pilot. In 1990, she was selected for astronaut training. Collins was able to pilot several space shuttle missions and was the first woman to serve as a commander on a space shuttle mission. She reached the rank of colonel in the United States Air Force.

Eileen Marie Collins was the daughter of Irish immigrants. She became interested in space flight at a young age. She began to pursue her dream by joining the air force and becoming a test pilot. In 1990, she was selected for astronaut training. Collins was able to pilot several space shuttle missions and was the first woman to serve as a commander on a space shuttle mission. She reached the rank of colonel in the United States Air Force.

Irish American women have come a long way since their days of domestic service. Some, like Collins are reaching for the stars. Others, like Fitzgerald, are stars. Some continue Mother Jones’ fight for the rights of the downtrodden, giving voice and hope to millions, and many are involved in STEM careers that they do not have to pursue in privacy in their own homes. These and many others have proven McNulty’s mother right in her assertion that Irish immigrants could be as good, if not better, than anybody. Chocolate Mint Shamrock Cookies

Chocolate Mint Shamrock Cookies

These festive cookies can be adapted to different holidays. Change the color of the topping, pipe it out in a different shape, and vary the flavor of the extract to serve any time of year.

1 cup sugar

2/3 cup shortening

½ tsp. mint extract

3 TBS cocoa powder

2 eggs

1 ¾ cup flour

¾ tsp baking soda

½ tsp salt

Sugar to roll cookies in

Topping

¼ cup flour

¼ cup butter, softened

1-1 ½ tsp warm water

2 drops green food coloring

Preheat oven to 375°

In large bowl, beat 1 cup sugar and shortening until light and fluffy. Add extract, cocoa and eggs and blend well. Stir in flour, baking soda and salt.

Shape into 1” balls and roll in sugar. Place 2” apart on a cookie sheet. Flatten with the bottom of a glass. If the glass sticks to the cookies, dip it in sugar.

To make topping, combine flour and butter until smooth. Add warm water until the paste is soft enough to extrude easily from a pastry bag with a small round tip. (If you don’t have a pastry bag, put mixture in a zip lock sandwich bag and snip a small hole in one corner.) Pipe shamrock design on top of each cookie.

Bake at 375° for 8-10 minutes or until set. Makes 6 dozen cookies. Jennifer Bohnhoff is a writer and educator who lives in central New Mexico. She claims a wee bit of Irish in her heritage, in additions to French, Norwegian, English, Swedish, and German. No one would argue that she isn't full of blarney.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a writer and educator who lives in central New Mexico. She claims a wee bit of Irish in her heritage, in additions to French, Norwegian, English, Swedish, and German. No one would argue that she isn't full of blarney.

Many of those newcomers to America entered domestic professions, where working as a maid, cook, nanny, or housekeeper helped them assimilate into American culture. A generation later, Irish women were entering professions at higher rates than any other immigrant group. They became teachers, bookkeepers, typists, journalists, social workers, and nurses. Irish American women represented the majority of public elementary school teachers in Providence, Boston, New York, Chicago, and San Francisco by 1910.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau. about 32 million Americans, or 9.7% of the total population, identifies as being Irish. In honor of Women’s History Month and St. Patrick’s Day, here are four Irish American Women who have made significant contributions, plus a recipe for cookies that will put you into the spirit of the day.. Mother Jones, Labor Agitator

Mother Jones, whose real name was Mary Harris Jones, was a tireless advocate for worker’s rights, the end of child labor, and for improved working conditions for miners. She was born in Cork, Ireland in 1837, but was still a child when the Harris family emigrated first to Canada and then to the United States.

Mother Jones, whose real name was Mary Harris Jones, was a tireless advocate for worker’s rights, the end of child labor, and for improved working conditions for miners. She was born in Cork, Ireland in 1837, but was still a child when the Harris family emigrated first to Canada and then to the United States.Mary Harris married an iron molder named George E Jones in 1861. Six years later, he and all four of their children died in a yellow-fever epidemic. The trade union he had belonged to helped the new widow, leaving a lasting impression on her.

When the great Chicago fire of 1871 destroyed her home and all of her belongings, Mrs. Jones left behind her job as a dressmaker to enter political activism. She joined the Knights of Labor and the Socialist Labor Party and became a full-time union organizer, travelling constantly around Pennsylvania, Ohio, Illinois, Indiana, West Virginia and Colorado as she organized marches, made speeches in the plain language of the working man, and deploying “broom and mop” brigades of workers’ wives to wage war against scabs and strike breakers.

Interestingly, although she believed in racial equality, she did not believe in equality of the sexes and opposed female suffrage. She believed in the traditional family, with a breadwinner husband and a wife who supported him.

Jones cultivated a grandmotherly persona, even lying about her age to appear older than she was. She made a lot of enemies. One district attorney called her the most dangerous woman in the United States. The writer Upton Sinclair called the left-wing firebrand the walking wrath of God. But while she angered many people, she secured valuable nationwide press attention for the causes she championed.

Kay McNulty, Computer Programmer

On February 12, 1921, important events happened to the McNultys of Donegal County, Ireland: Their daughter Kay was born, and the father was arrested for IRA membership. Two years later, when he was finally released from prison, the family left their farm and emigrated to Pennsylvania. The move turned out to be lifechanging for Kay, whose mother encouraged her to do her best “to prove that Irish immigrants could be as good, if not better, than anybody.” While only 37% of girls in Ireland were enrolled in school in 1929, Kay was able earn a scholarship while in High School that allowed her to attend Chestnut Hill College for Women. She graduated with a mathematics degree.

On February 12, 1921, important events happened to the McNultys of Donegal County, Ireland: Their daughter Kay was born, and the father was arrested for IRA membership. Two years later, when he was finally released from prison, the family left their farm and emigrated to Pennsylvania. The move turned out to be lifechanging for Kay, whose mother encouraged her to do her best “to prove that Irish immigrants could be as good, if not better, than anybody.” While only 37% of girls in Ireland were enrolled in school in 1929, Kay was able earn a scholarship while in High School that allowed her to attend Chestnut Hill College for Women. She graduated with a mathematics degree.When World War II began, the US Army hired Kay as a “computer”, calculating missile trajectories. In 1945, she and five other women were moved to Aberdeen military base in Maryland to developing the processor for a top-secret 30-ton machine called the Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer (ENIAC). Later, she worked at another programming job, which she only discovered later was testing the feasibility of the H-bomb.

In 1948 Kay married a computer developer named John Mauchly. As was usual at the time, she stopped her career. But throughout the time when she raised seven children,

Kay continued, unpaid and unnoticed, to program the new computers that her husband was developing.

It wasn’t until decades later, in 1997, that McNulty and the other five ENIAC women were inducted into the Women in Technology International Hall of Fame.

Ella Fitzgerald, Singer

Ella Fitzgerald may not look Irish, but when she acknowledged her heritage, the people of Ireland were happy to have her. The First Lady of Song was born to a woman who was African American/Cherokee Indian. Her father, who was Irish enough to have a family crest, never married her mother, and abandoned the family when Ella was quite young. During a singing tour of Ireland in the 1960s, Fitzgerald told reporters that she had the family crest in her home, and the authorities used a special stamp on her passport to acknowledge her heritage.

Ella Fitzgerald may not look Irish, but when she acknowledged her heritage, the people of Ireland were happy to have her. The First Lady of Song was born to a woman who was African American/Cherokee Indian. Her father, who was Irish enough to have a family crest, never married her mother, and abandoned the family when Ella was quite young. During a singing tour of Ireland in the 1960s, Fitzgerald told reporters that she had the family crest in her home, and the authorities used a special stamp on her passport to acknowledge her heritage.Fitzgerald has a voice that continues to amaze and entertain listeners years after her death. She remains famous for her scat singing and her associations with other jazz greats such as Louie Armstrong and Duke Ellington. Her musical career spanned six decades and several genres, though she remained a jazz singer at heart.

Ella could be considered a symbol of the mixing of cultures that is distinctly American

Eileen Marie Collins, AstronauT

Eileen Marie Collins was the daughter of Irish immigrants. She became interested in space flight at a young age. She began to pursue her dream by joining the air force and becoming a test pilot. In 1990, she was selected for astronaut training. Collins was able to pilot several space shuttle missions and was the first woman to serve as a commander on a space shuttle mission. She reached the rank of colonel in the United States Air Force.

Eileen Marie Collins was the daughter of Irish immigrants. She became interested in space flight at a young age. She began to pursue her dream by joining the air force and becoming a test pilot. In 1990, she was selected for astronaut training. Collins was able to pilot several space shuttle missions and was the first woman to serve as a commander on a space shuttle mission. She reached the rank of colonel in the United States Air Force.

Irish American women have come a long way since their days of domestic service. Some, like Collins are reaching for the stars. Others, like Fitzgerald, are stars. Some continue Mother Jones’ fight for the rights of the downtrodden, giving voice and hope to millions, and many are involved in STEM careers that they do not have to pursue in privacy in their own homes. These and many others have proven McNulty’s mother right in her assertion that Irish immigrants could be as good, if not better, than anybody.

Chocolate Mint Shamrock Cookies

Chocolate Mint Shamrock CookiesThese festive cookies can be adapted to different holidays. Change the color of the topping, pipe it out in a different shape, and vary the flavor of the extract to serve any time of year.

1 cup sugar

2/3 cup shortening

½ tsp. mint extract

3 TBS cocoa powder

2 eggs

1 ¾ cup flour

¾ tsp baking soda

½ tsp salt

Sugar to roll cookies in

Topping

¼ cup flour

¼ cup butter, softened

1-1 ½ tsp warm water

2 drops green food coloring

Preheat oven to 375°

In large bowl, beat 1 cup sugar and shortening until light and fluffy. Add extract, cocoa and eggs and blend well. Stir in flour, baking soda and salt.

Shape into 1” balls and roll in sugar. Place 2” apart on a cookie sheet. Flatten with the bottom of a glass. If the glass sticks to the cookies, dip it in sugar.

To make topping, combine flour and butter until smooth. Add warm water until the paste is soft enough to extrude easily from a pastry bag with a small round tip. (If you don’t have a pastry bag, put mixture in a zip lock sandwich bag and snip a small hole in one corner.) Pipe shamrock design on top of each cookie.

Bake at 375° for 8-10 minutes or until set. Makes 6 dozen cookies.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a writer and educator who lives in central New Mexico. She claims a wee bit of Irish in her heritage, in additions to French, Norwegian, English, Swedish, and German. No one would argue that she isn't full of blarney.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a writer and educator who lives in central New Mexico. She claims a wee bit of Irish in her heritage, in additions to French, Norwegian, English, Swedish, and German. No one would argue that she isn't full of blarney.

Published on March 14, 2021 12:23

March 1, 2021

Starvation Peak

A few weeks ago I got an email from a woman whose father had read my Civil War Novels Valverde and Glorieta and was anxious to know when Peralta, the third and final book in the series, would be out.

A few weeks ago I got an email from a woman whose father had read my Civil War Novels Valverde and Glorieta and was anxious to know when Peralta, the third and final book in the series, would be out. I had to admit to her that teaching was taking up far too much of my time these days, and that my work on Peralta has stalled. I have written through Chapter 8, and outlined the rest of the novel, but it’s not going to be finished until the end of summer at the earliest.

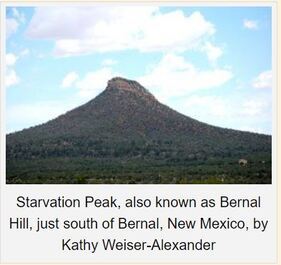

She then asked me if I knew of any other stories set in the Starvation Peak area, or near Bernal. I was flummoxed. Although I knew where Bernal was, I’d never heard of Starvation Peak. The name intrigued me, and I began digging for answers.

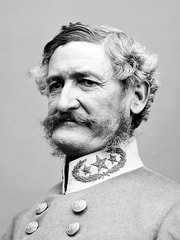

Juan Bautista de Anza, Governor of New Mexico 1777-1787 The village of Bernal is one of many created after Governor Juan Bautista Anza forced marauding Comanches to sign the Comanche Peace Treaty in 1786. Prior to this, the area around Pecos Pueblo had been too vulnerable, a reason the inhabitants of Pecos Pueblo abandoned their home in the 1830s to live with their cousins in Jemez.

Juan Bautista de Anza, Governor of New Mexico 1777-1787 The village of Bernal is one of many created after Governor Juan Bautista Anza forced marauding Comanches to sign the Comanche Peace Treaty in 1786. Prior to this, the area around Pecos Pueblo had been too vulnerable, a reason the inhabitants of Pecos Pueblo abandoned their home in the 1830s to live with their cousins in Jemez.In November 1794, Lorenzo Marquez asked Spanish Governor Fernando Chacón to make a land grant for him and 51 other families from Santa Fe. Marquez said in the petition that the families were large, but had only small parcels of land in Santa Fe, and not enough water.

He noted that thirteen of the fifty-two petitioners were Indians, probably from the Pecos Pueblo. Since most of the outlying grants were given, according to Fray Angélico Chávez, to “Spanish military personnel and the genízaro colony of Santa Fe [1] , it is likely that most of the other families in the group were either Genízaros or mestizos. Historians speculate that Marquez had been a presidio soldier stationed around Pecos Pueblo and was therefore familiar with the area. Genízaros are Indigenous people who had assimilated into Spanish culture. They included Puebloans from Pecos, San José and San Miguel, plus converts from the Comanche and other Plains tribes. More than fourteen percent of the population of Santa Fe was made up of Genízaros.

The 315,000-acre grant, which became known as San Miguel del Vado Land Grant, was approved. Soon a number of new communities, including Bernal, were established in the Pecos River Valley.

Towering over the village of Bernal is a 7,031-foot flat-topped butte that is named Starvation Peak. The legend is that, during the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, 36 Spanish colonists took shelter at the top of this mesa. Some accounts say they eventually tried to leave and were slaughtered and buried at the foot of the mesa. Other accounts say the colonists died of thirst and starvation while still atop. The story is documented in an 1884 edition of the Detroit Free Press, but has grown. the years. When writers from the Works Progress Administration were documenting the region in 1939, they recorded 120 colonists had died.

Starvation Peak became a way-finder point along the Santa Fe Trail when it opened in 1821. It was distinctive enough to help guide travelers. Major William Anderson Thornton, a member of an 1855 military expedition that passed through reposted that General Kearny had wanted to place a flag atop the peak when he marched through the area during the Mexican American war, but after walking around its base, declared the task impossible.

At the base of the peak lies Bernal Springs, which became a campsite and stage stop along the trail. There is little doubt that Bernal profited from trading with travelers. When the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad laid its tracks through the Pecos Valley in the early 1880s, it bypassed the town, which has become a sleepy little village set in a spectacularly beautiful land.

[1] Fray Angelico Chavez, Archives of the Archdiocese of Santa Fe, 1678-1900 (Academy of American Franciscan History: Washington D.C., 1951), 205.

https://www.legendsofahttps://newmexicohistory.org/2012/06/29/san-miguel-del-bado-grant/merica.com/bernal-new-mexico/

https://www.newspapers.com/clip/8213241/pretty-good-starvation-peak/

Jennifer Bohnhoff teaches New Mexico History in a rural New Mexico Middle School. She is the author of Valverde and Glorieta, novels about the Civil War battles in New Mexico. The third in the series, Peralta, will come out when she finds the time to write it. You can read more about Mrs. Bohnhoff and her books at her website, where you can also sign up to receive emails about her work and upcoming sales and giveaways.

Jennifer Bohnhoff teaches New Mexico History in a rural New Mexico Middle School. She is the author of Valverde and Glorieta, novels about the Civil War battles in New Mexico. The third in the series, Peralta, will come out when she finds the time to write it. You can read more about Mrs. Bohnhoff and her books at her website, where you can also sign up to receive emails about her work and upcoming sales and giveaways.

Published on March 01, 2021 00:00

February 22, 2021

Two Famous McAdams

Last week I wrote about American Presidents of Scots descent. This week, I’ll share some information on two more Scotsmen. One had a tenuous tie with the United States, the other had no connection to America, but they’re both interesting men, whose name has lived beyond them.

Last week I wrote about American Presidents of Scots descent. This week, I’ll share some information on two more Scotsmen. One had a tenuous tie with the United States, the other had no connection to America, but they’re both interesting men, whose name has lived beyond them.John Loudon McAdam was the inventor of “macadamisation,” an effective and economical method of constructing roads. Born in Ayr, Scotland in 1756, McAdam made his fortune working in his Uncle’s counting house in New York during the American Revolution. When he returned home in 1783, he bought an estate and began operating a colliery, some kilns, and an ironworks. These businesses gave him the technical knowledge to suggest that roads should be raised above the surrounding ground and constructed of systematically layered rocks and gravel. He wrote his conclusions in two treatises, Remarks on the Present System of Roadmaking (1816) and Practical Essay on the Scientific Repair and Preservation of Roads (1819).

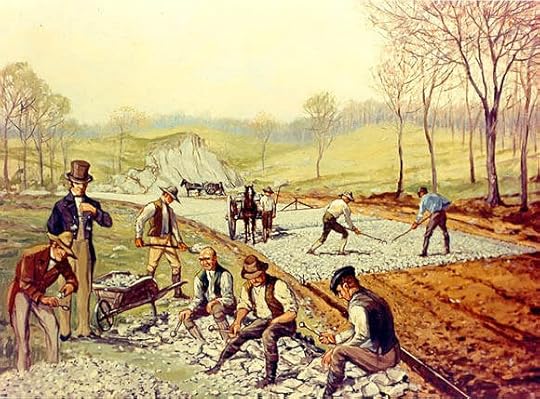

By Peetlesnumber1 - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index... In time, road builders began adding hot tar to bond the rocks and gravel together. This is what I’ve always called asphalt but depending on where you live it can be called macadam, blacktop, or tarmac, a mixture of the words tar and “macadam.

By Peetlesnumber1 - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index... In time, road builders began adding hot tar to bond the rocks and gravel together. This is what I’ve always called asphalt but depending on where you live it can be called macadam, blacktop, or tarmac, a mixture of the words tar and “macadam.The first macadam road in North America was the National Road, also known as the Cumberland Road. Construction began in 1811, in Cumberland, Maryland, on the Potomac River. The road stretches 620 miles and connects the Potomac to the Ohio River. It was macadamized in the 1830s and became the main road for thousands of settlers moving west. The road ended in Vandalia, Illinois, 63 miles east of St. Louis, It would have gone further had not an 1837 financial panic led Congress to cut off funding.

The other McAdam whose name has outlived him is Dr. John Macadam, who was born outside of Glasgow, Scotland in 1827. He taught university-level chemistry, first in Glasgow and then in Melbourne, Australia. He was also a medical doctor, a health official for the city of Melbourne and a member of the agricultural board. As a politician, he fought to make parliament enact food purity laws. The macadamia nut, a native plant of Australia, was named in his honor by the botanist Ferdinand von Mueller.

The other McAdam whose name has outlived him is Dr. John Macadam, who was born outside of Glasgow, Scotland in 1827. He taught university-level chemistry, first in Glasgow and then in Melbourne, Australia. He was also a medical doctor, a health official for the city of Melbourne and a member of the agricultural board. As a politician, he fought to make parliament enact food purity laws. The macadamia nut, a native plant of Australia, was named in his honor by the botanist Ferdinand von Mueller.Here’s one of my favorite uses for macadamia nuts. I think Dr. John would have enjoyed them, and I hope you do, too.

Chocolate Macadamia Cookies

¾ cup firmly packed brown sugar

¾ cup firmly packed brown sugar½ cup sugar

1 cup softened butter

1 tsp almond extract

1 egg

2 cups flour

¼ cup cocoa

1 tsp baking soda

½ tsp salt

1 cup white chocolate chips

½ cup macadamia nuts, coarsely chopped

Preheat oven to 375°.

Beat sugars and butter until light and fluffy.

Add extract and egg and blend well.

Stir in flour, cocoa, baking soda and salt and mix well.

Stir in chips and nuts.

Drop by rounded tablespoonfuls, 2” apart on ungreased cookie sheets.

Bake at 375° for 8-12 minutes, or until set.

Cool 1 minute before removing from sheet to cooling rack.

Makes 2 ½ cookies.

Published on February 22, 2021 00:00

February 15, 2021

Shortbread and Scots-American Presidents

Since February has Presidents Day, I'd intended to write a piece on George Washington and include a recipe that had something to do with him. Martha Washington was a famous cook in her day; surely I could find a recipe for cookies that she made for her husband.

Since February has Presidents Day, I'd intended to write a piece on George Washington and include a recipe that had something to do with him. Martha Washington was a famous cook in her day; surely I could find a recipe for cookies that she made for her husband. But as I began planning, I remembered this shortbread pan that I've had a long time. (It might have been a wedding gift, but as I've been married over 40 years, I can't remember.)

Although I usually make shortbread at Christmas, the lovely hearts on the pan make it very appropriate for Valentines Day, and that led me on a search to find a connection between shortbread and February. Turns out I didn't have to search very hard at all, and my search led me right back to George Washington. George Washington may have been our first president with ties to Scotland, but he wasn't our last.

Scotland.org states that 34 of our 44 presidents have been of either Scottish or Ulster-Scots descent. This includes George Washington, James Polk, Theodore Roosevelt, Gerald Ford, Ronald Regan, and Bill Clinton. Even Barack Obama, our first African-American president, has some Scots blood. Genealogists have found that his ancestry can be traced back to William the Lion who ruled Scotland from 1165 to 1214.

So this President's Day, enjoy a bit of shortbread and think about what Scotland has contributed to the United States.

My recipe for shortbread has a secret added ingredient: corn starch. While it is unusual, I've found that it leads to a tighter crumb. These cookies won't shatter when you bite down on them, but they are still rich and not too sweet. Shortbread

1/2 lb.(2 sticks) butter

1/2 lb.(2 sticks) butter1/2 cup sugar

2 cups flour

1/2 cup corn starch

Preheat oven to 325 If you have a shortbread pan, place it in the over and let it preheat.

Melt butter.

Mix sugar, flour and cornstarch together. Pour melted butter over and blend together. Pat into preheated mold.

Back at 325 for 40 minutes. Reduce heat to 300 and bake another 20 minutes, or until edges are slightly brown. Turn out shortbread onto a plate as soon as they come out of the oven. Use a large knife to slice the wedges apart when the shortbread is still warm. Variations If you don't own a shortbread pan, you can use any of these four variations.

Wedges: pat into two 8" circles. Cut into 8-12 wedges, but don't separate them. Back at 325 for 30 minutes. Recut while warm

Thumbprints: roll into 1: balls, Place 2" apart on a cookie sheet and press thumb into the center of each to make a deep indentation. Back at 325 for 18 minutes. Immediately after removing from over, fill each indentation with 1/2 tsp preserves. Cool before removing from cookie sheet.

Pecan spice: Substitute brown sugar for white and add 1 tsp of pumpkin spice to the original recipe. Pat into a 9x13" pan. Cut into 1x1/12" rectangles. Place a pecan half on each rectangle. Bake at 325 for 25 minutes. Recut while warm and let cook in the pan before sprinkling with powdered sugar.

Shortbread triangles: Substitute brown sugar for white and add 1 tsp of pumpkin spice to the original recipe. Pat into a 9x13" pan. Sprinkle dough with 1/4 cup chopped pecans; press them into the dough. Cut into 16 squares, then divide each square crosswise to make triangles. Bake at 325 for 25 minutes. Recut while warm. When cool, drizzle with vanilla icing.

Vanilla icing: 1/2 cup powdered sugar, 1/4 tsp vanilla, 2-3 tsp milk, stirred until smooth. Jennifer Bohnhoff is an educator and writer who lives in central New Mexico. You can learn more about her books here.

Published on February 15, 2021 00:00

February 8, 2021

early Africans in New Mexico

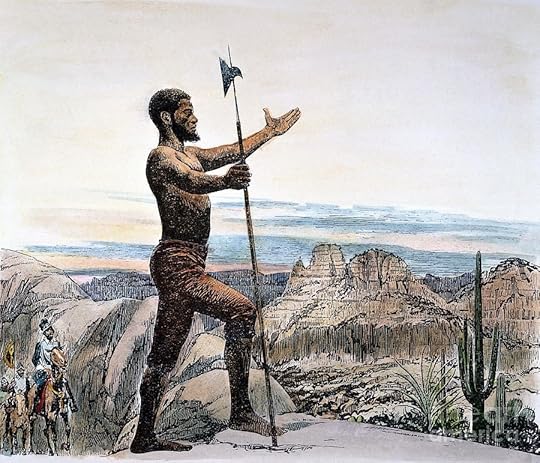

Painting, Estavanico by Granger. Image available on the Internet and included in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. New Mexico is often referred to as a land of three cultures, meaning the Native Americans, who’ve lived here for at least 11,000 years, the Hispanics who moved into the state beginning in the 1500s, and Anglo-Americans who moved in along the Santa Fe trail beginning in the 1800s. That description is misleading and makes the state look far less diverse and culturally rich than it is.

Painting, Estavanico by Granger. Image available on the Internet and included in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. New Mexico is often referred to as a land of three cultures, meaning the Native Americans, who’ve lived here for at least 11,000 years, the Hispanics who moved into the state beginning in the 1500s, and Anglo-Americans who moved in along the Santa Fe trail beginning in the 1800s. That description is misleading and makes the state look far less diverse and culturally rich than it is.One of the first “outsiders” who set foot in New Mexico was neither Hispanic nor Anglo. In fact, he wasn’t even European. Mustafa Azemmouri, was a man of many names. History books usually call him by his slave name: Esteban, sometimes spelled Estevan. He’s also referred to as Estevanico, Esteban de Dorantes or Esteban the Moor. Estevan was born in the port city of Azemmour, Morocco, sometime around 1503. In 1513 he was captured by the Portuguese and became a slave. Sometime around 1521 he was purchased by Andres de Dorantes of Bejar del Castanar, who joined an expedition to explore Florida in 1527. After the expedition went badly, the survivors made crude boats and rafts and tried to sail to Mexico, floundering on the Texas coast near present day Galveston. Only 80 of the original party of nearly 500 made it this far; after five years of enslavement by the local Indians, the number was down to four.

In 1534, these four men escaped their captors and began the long walk back to Mexico. They moved from tribe to tribe, acting as medicine men as they went. Estevan proved to be gifted in languages, and became fluent in several Indian dialects. He carried a medicine rattle, a feathered, beaded gourd given to him by a chief, as his good luck symbol and trademark. The men followed the Rio Grande, entering Mexico near El Paso. They finally arrived in Mexico City in July of 1536, where the Viceroy, enchanted by their tales of a golden city, organized an expedition to Arizona and New Mexico. Estevan guided the group, which was led by a Franciscan priest named Fray Marcos de Niza.

When Estevan arrived in at Hawikuh, a Zuni pueblo in Northwest New Mexico, the inhabitants saw that his medicine gourd was trimmed with owl feathers, a bird that symbolized death to the Zuni. Thinking him evil, they killed him.

Estevan was only the first of many Africans who came to New Mexico as slaves or servants. Many of the Spanish brought their slaves with them to the new world. Another is Sebastian Rodriguez, who was born sometime around 1642 in Angola, Africa and came to New Mexico in 1692. Records indicate that Governor Diego de Vargas, the man charged with resettling New Mexico after the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, brought Rodriguez with him as he traveled north. Rodrigues had been the drummer and town crier for the garrison in El Paso. He continued to serve in that capacity once Santa Fe returned to Spanish control. Rodriguez was able to both marry and acquire property. Records show he purchased land in Santa Fe in 1697. One of his sons continued in his father's positions as Santa Fe’s town crier and drummer in Santa Fe. Another son became one of the first settlers of the northern village of Las Trampas.

Rodriguez wasn’t the only African to enter the state with the reconquest. Among the over eight hundred persons that Vargas brought into the area were twenty-seven families listed in the records as Negro or Mestizo. Many of these families were given grants in the mountain communities north of Santa Fe. They married and mixed with their neighbors, both Spanish and Native, their cultures melding into something unique to Northern New Mexico.

Published on February 08, 2021 00:00

January 25, 2021

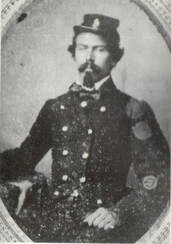

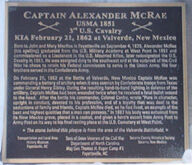

Captain Alexander McRae

Families divided, brother against brother. It's one of the themes of the American Civil War. Alexander McRae's story is an example of it.

Families divided, brother against brother. It's one of the themes of the American Civil War. Alexander McRae's story is an example of it.Alexander McRae was born in Fayetteville, North Carolina on September 4, 1829. He had four brothers.

A West Point Graduate, McRae served in Missouri and Texas before coming to New Mexico in 1856, He served at Forts Union, Stanton, and Craig. McRae also spent some time at Bent's Fort, in what is now Colorado. He steadily rose up the promotion ladder, becoming Captain of Company I, 3rd Cavalry Regiment in August of 1861.

When the Civil War broke out, McRae's father wrote to him, urging him to change sides. Captain McRae retained his commission and stayed faithful to his country while his four brothers, James, Thomas, John, and Robert, served the Confederacy.

As reports began to trickle into New Mexico of a Southern invasion, Colonel Edward R.S. Canby, the commander of forces in New Mexico Territory, hastily formed an artillery battery. He placed the six pieces at Fort Craig, the most southerly of the forts held by the Union Army, and gave Captain McRae charge of this unit.

McRae's battery performed with great success during the first hours of the Battle of Valverde, which took place at a Rio Grande crossing a few miles north of Fort Craig on February 21, 1862 .

McRae's battery performed with great success during the first hours of the Battle of Valverde, which took place at a Rio Grande crossing a few miles north of Fort Craig on February 21, 1862 . Finally, Confederate Colonel Thomas Green led a charge on the Union guns. Screaming the Rebel yell, the Confederate forces advanced in three separate waves that totaled nearly 750 men. The Rebels, armed with short-range shotguns, pistols, muskets, and bowie knives, watched for flashes from the artillery, then dove to the ground for cover. This strategy made them appear to be suffering a high casualty rate, yet they kept coming. This spooked the men manning the Union guns, particularly the inexperienced and ill-trained New Mexico Volunteers, who broke and splashed across the Rio Grande in a disorganized retreat.

Despite McRae's remaining gunners firing shell and cannister as fast as they could, the Texans reached the battery. Fierce hand-to-hand fighting ensued as the Union soldiers sought to defend their position. Samuel Lockridge, a Texan officer reportedly shouted, "Surrender McRae, we don't want to kill you!" McRae supposedly replied, "I shall never forsake my guns!" Both Lockridge and McRae were killed in the melee, some sources suggesting by each other.

The captured guns went to San Antonio when the Confederate forces retreated. They became known as the Valverde Battery and were used against Union troops for the remainder of the war.

Because he fought for the Union, McRae's service record went unrecognized in his home state. In their story on the battle at Valverde, the Fayetteville Observer did not even report his death. However, McRae became an honored figure in New Mexico history. There are streets named after him in the New Mexican towns of Las Cruces and Las Vegas, and a canyon named for him in Sierra County. The remains of Fort McRae, a late Civil War and Indian War Army post named for him, now lay beneath the waters of Elephant Butte Lake. I could find some earlier reports of it being a destination for scuba divers, but the adobe walls have probably succumbed to time and water by now.

Because he fought for the Union, McRae's service record went unrecognized in his home state. In their story on the battle at Valverde, the Fayetteville Observer did not even report his death. However, McRae became an honored figure in New Mexico history. There are streets named after him in the New Mexican towns of Las Cruces and Las Vegas, and a canyon named for him in Sierra County. The remains of Fort McRae, a late Civil War and Indian War Army post named for him, now lay beneath the waters of Elephant Butte Lake. I could find some earlier reports of it being a destination for scuba divers, but the adobe walls have probably succumbed to time and water by now. Alexander McRae's body was exhumed in 1867 and transported to West Point for burial. McRae’s large black tombstone is only four markers away from the one dedicated to George Armstrong Custer. Guides frequently note it as the resting place of one who stayed with the Union.

In his official report of the Combat of Valverde, Colonel Canby, wrote:

In his official report of the Combat of Valverde, Colonel Canby, wrote:Among the killed is one, isolated by peculiar circumstances, whose memory deserves notice from a higher authority than mine. Pure in character, upright in conduct, devoted to his profession, and of a loyalty that was deaf to the seductions of family and friends, Captain McRae died, as he had lived, an example of the best and highest qualities that man can possess.

In time, the South also recognized Captain Alexander McRae. A marker now stands in front of the Old Historic Cumberland County Courthouse, which was built on land that was homesteaded by his grandparents.

While he is not a speaking character, Captain Alexander McRae's death is part of the battle scene in Jennifer Bohnhoff's novel Valverde. Valverde is the first in a trilogy of novels set in New Mexico during the Civil War.

While he is not a speaking character, Captain Alexander McRae's death is part of the battle scene in Jennifer Bohnhoff's novel Valverde. Valverde is the first in a trilogy of novels set in New Mexico during the Civil War.

Published on January 25, 2021 00:00

January 18, 2021

Peanut Pie

The last slice of the latest peanut pie in our house.

The last slice of the latest peanut pie in our house.

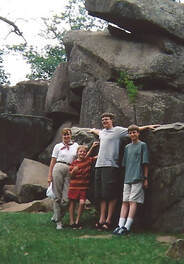

The author and her sons at Devil's Den, Gettysburg During the summer of 2000, my husband and I took our three sons on an historical vacation. Among the places visited were Williamsburg and Gettysburg, both places where we ate peanut pie in local taverns, so that the pie is associated in our minds with American history.

The author and her sons at Devil's Den, Gettysburg During the summer of 2000, my husband and I took our three sons on an historical vacation. Among the places visited were Williamsburg and Gettysburg, both places where we ate peanut pie in local taverns, so that the pie is associated in our minds with American history. Many histories of peanuts say that they came to America in the 1700s, carried from Africa along with slaves. While that may be true, they are not originally from Africa. Peanuts seem to have originated in South America, in Peru. They were taken back to Africa by the Spanish before coming to North America.

Wherever they came from, I'm glad they made it into my family's repertoire. This recipe is adapted from the Chowning's Tavern Pie from historical Williamsburg. Peanut Pie For the Crust:

1 1/3 cup flour

1/2 tsp salt

1/2 C shortening

Cut shortening into flour and salt mixture until it resembles cornmeal in consistency, with some particles the size of small peas.

3 TBS ice water

1/2 TBS vinegar

Mix water and vinegar and sprinkle over the flour mixture, 1 TBS at a time, mixing until the dough clumps together. You may not use all the liquid.

Press together, then place on a floured piece of waxed paper or parchment. Roll out until it is larger than your pie place. Invert the paper over the pie plate to fit in. Flute edged.

For the Filling:

3 large eggs,

3/4 cup brown sugar

1 cup light corn syrup

3/4 tsp vanilla

1 1/2 TBS melted butter

1 cup peanuts (you may use salted or unsalted, but I prefer unsalted, roasted Virginia peanuts with the skins removed.)

Beat the eggs, brown sugar, corn syrup and vanilla together in a large bowl. Add the melted butter and peanuts. Pour into the pie shell and bake in a preheated oven at 350 until the filling is set in the center and the pastry is lightly browned, about 45 minutes.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a writer and educator who lives high in the mountains of central New Mexico. She wrote about Gettysburg in her novel, The Bent Reed, which is available in ebook and paperback.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a writer and educator who lives high in the mountains of central New Mexico. She wrote about Gettysburg in her novel, The Bent Reed, which is available in ebook and paperback.

Published on January 18, 2021 00:00

January 10, 2021

George Washington Carver

When many people hear the name George Washington Carver, they think of peanuts. But the American agricultural scientist and inventor’s greatest contributions may have been in soil conservation, environmentalism, and helping the poor.

When many people hear the name George Washington Carver, they think of peanuts. But the American agricultural scientist and inventor’s greatest contributions may have been in soil conservation, environmentalism, and helping the poor.Carver was born a slave sometime in January 1864 in rural western Missouri, and freed at the end of the Civil War. When he was in his 20s, he moved to Iowa and began attending Simpson College, then Iowa State Agricultural College (now Iowa State University), where he was their first African-American student. Iowa State Agricultural College was the country’s first land-grant university, and its mission was to teach the applied sciences, including agriculture. Carver studied botany.

When he graduated in 1896, Carver became the first black man in the U.S. to hold a degree in modern agricultural methods. He took those lessons south to Alabama, where Booker T. Washington, the first leader of the Tuskegee Institute, was opening an agricultural school. What he saw as he rode the train south broke his heart. Instead of the golden wheat fields and the tall green corn of Iowa, he “scraggly cotton, stunted cattle, boney mules, and fields and hill sides cracked and scarred with gullies.” Because of his training, Carver knew that the poor condition of the land was due to the overplanting of cotton, a lucrative crop that depletes the soil. Carver knew that something had to be done to make the soil rich again. One of his solutions was peanuts.

Because of a symbiotic relationship with the bacteria that live on their roots, peanuts produce their own nitrogen, fertilizing themselves and restoring nutrients to depleted soil. Additionally, their growing periods are different than cotton, so peanuts and cotton could be grown in the same fields on a rotating schedule. Finally, peanuts are high in protein and more nutritious than the “3M--meat, cornmeal and molasses” diet that was the foundation for most poor farmers’ diet.

Because of a symbiotic relationship with the bacteria that live on their roots, peanuts produce their own nitrogen, fertilizing themselves and restoring nutrients to depleted soil. Additionally, their growing periods are different than cotton, so peanuts and cotton could be grown in the same fields on a rotating schedule. Finally, peanuts are high in protein and more nutritious than the “3M--meat, cornmeal and molasses” diet that was the foundation for most poor farmers’ diet.

Most black farmers in turn-of-the-century Alabama were so close to ruination that they weren’t willing to try something new. Carter encouraged them by coming up with literally hundreds of recipes and uses for peanuts, including peanut bread, peanut cookies, peanut sausage, peanut ice cream, and even peanut face cream, shampoo, dyes and paints.

But Carver was not just pushing peanuts; he was pushing a lifestyle that connected the farmer to his soil, enriching both. He encouraged farmers to grow other vegetables so they would spend less money on food. Rather than going into debt buying fertilizer, he encouraged composting. Well before the hippies and back to nature movements reached the mainstream, Carver pushed the interconnectedness between the health of the land and the health of the people who lived on it. "It has always been the one great ideal of my life to be of the greatest good to the greatest number of ‘my people’ possible and to this end I have been preparing myself these many years; feeling as I do that this line of education is the key to unlock the golden door of freedom to our people.”

When Carver died on January 5, 1943, President Franklin D. Roosevelt said that “The world of science has lost one of its most eminent figures.”

Peanut Butter Cookies, two ways

Peanut Blossoms

Peanut BlossomsGeorge Washington Carver may have invented a recipe for peanut butter cookies, but it wasn’t this one. This cookie first appeared in 1957 as a prize winner in a Pillsbury Bake-Off contest.

1 ¾ cup flour

½ cup sugar

½ cup brown sugar, firmly packed

1 tsp. baking soda

½ tsp salt

½ cup shortening

½ cup peanut butter

2 TBS milk

1 tsp vanilla

1 egg

¼ cup sugar, set aside in a shallow bowl

About 48 milk chocolate candy kisses

Preheat oven to 375°

Combine flour, sugar, brown sugar, baking soda, salt, shortening, peanut butter, milk, vanilla, and egg at low speed until stiff dough forms.

Shape into 1” balls. Roll in the bowl of sugar.

Place 2” apart on a cookie sheet.

Bake at 375°for 10-12 minutes or until golden brown.

Remove from over and immediately press a candy kiss into the center of each.

Let cool 2 minutes before removing to a cooking rack.

Makes about 4 dozen cookies.

Variation:

Peanut Butter Crisscross Cookies

Make dough, shape into balls and roll in sugar as above.

Place 2” apart on a cookie sheet.

Flatten each cookie by pressing a fork dipped in sugar into it in a crisscross pattern.

Bake at 375°for 10-12 minutes or until golden brown.

Immediately remove to a cooking rack from cookie sheet.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is an educator and writer who lives in the mountains of central New Mexico. Her books are written for middle schoolers and adults, and are mostly works of historical fiction.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is an educator and writer who lives in the mountains of central New Mexico. Her books are written for middle schoolers and adults, and are mostly works of historical fiction. This article is, she believes, the first installment in a monthly series on famous Americans and cookies inspired by their stories. She intends to compile all the stories and recipes into a cookbook to give out to my friends, family and fans at the end of 2021. If you'd like a copy, go to her website and join her email list.

Published on January 10, 2021 00:00

January 4, 2021

Louisa Hawkins Canby: The Angel of Santa Fe

Louisa Hawkins Canby earned the epithet Angel of Santa Fe by showing compassion to wounded Confederate soldiers during their 1862 occupation of Santa Fe, New Mexico. For this humanitarian act, some people have called her a traitor. They would do well to consider her a diplomat and a savvy negotiator, whose act of mercy saved the city and its inhabitants a lot of grief.

Louisa Hawkins Canby earned the epithet Angel of Santa Fe by showing compassion to wounded Confederate soldiers during their 1862 occupation of Santa Fe, New Mexico. For this humanitarian act, some people have called her a traitor. They would do well to consider her a diplomat and a savvy negotiator, whose act of mercy saved the city and its inhabitants a lot of grief. Louisa Hawkins was only 19 years old when she met Edward Richard Sprigg Canby, a West Point cadet who had come home to Crawfordsville, Indiana on summer furlough. Edward, as he was called by most, and Louisa were both Kentucky natives, and seemed smitten with each other from the start. They married during the summer of 1839 after both had graduated: he from West Point and she from Georgetown Female College in Georgetown, Kentucky. Louisa then followed her husband through his many posts in California, New York, Wyoming and Utah. They had one child, a daughter they named Mary, but she died while still very young. By 1860, Canby was commander of Fort Defiance. He procured a large house in Santa Fe for Louisa to use during his many campaigns.

At the beginning of the Civil War, the one armed William Wing Loring was the Commander of the Department of New Mexico, an area that covers what is now the states of Arizona, New Mexico and the southern tip of Nevada. Loring resigned his commission to join the Confederacy, and the post was given to H.H. Sibley, who also left to join the South. Edward R.S. Canby then received the post and a promotion to Colonel.

At the beginning of the Civil War, the one armed William Wing Loring was the Commander of the Department of New Mexico, an area that covers what is now the states of Arizona, New Mexico and the southern tip of Nevada. Loring resigned his commission to join the Confederacy, and the post was given to H.H. Sibley, who also left to join the South. Edward R.S. Canby then received the post and a promotion to Colonel. Concerned of a Confederate invasion from Texas in the south, he stationed himself at Fort Craig a fort that protected the northern edge of the Jornada del Muerto, a dry section of the Camino Real. He left Louisa in the relative safety of Santa Fe, far to the north.

Canby’s concerns proved real when a Confederate force led by Brigadier General Henry H. Sibley began moving up the Rio Grande River valley in late 1861. Finding Fort Craig heavily fortified, the Confederates bypassed Canby. The two armies engaged each other several miles upstream of the fort, at a place called Valverde Ford. The battle ended when the Union troops returned to Fort Craig and the Confederates continued north. Canby then commanded all troops in the northern part of the state to pull back and converge on Fort Union. The troops were to destroy or hide weapons, ammunition, food, equipment, and blankets prior to their retreat.

Canby’s concerns proved real when a Confederate force led by Brigadier General Henry H. Sibley began moving up the Rio Grande River valley in late 1861. Finding Fort Craig heavily fortified, the Confederates bypassed Canby. The two armies engaged each other several miles upstream of the fort, at a place called Valverde Ford. The battle ended when the Union troops returned to Fort Craig and the Confederates continued north. Canby then commanded all troops in the northern part of the state to pull back and converge on Fort Union. The troops were to destroy or hide weapons, ammunition, food, equipment, and blankets prior to their retreat.

Instead of leaving with the army, Louisa Canby and several other officers’ wives chose to stay in Santa Fe. When the Confederates marched into town on March 10, these women formed a delegation to meet them. Mrs. Canby asked that the city not be sacked, and that its citizens not be molested. In return she promised to aid the Confederate army’s sick and wounded and worked with Archbishop Lamy to provide shelter for the men. After a brief respite in the city, the Confederate Army continued its journey north, towards Fort Union, but when they heard distant cannon fire, the people of Santa Fe knew that a battle was taking place in Glorieta Pass, the narrow passage through the Sangre de Cristo mountains that held the Santa Fe trail. Soon, wounded Confederates were limping back into the capitol city.

When Louisa Canby heard that some soldiers were unable to return due to extreme hunger, exhaustion or loss of blood, she drove her carriage along the route, delivering food, water and blankets. Mrs. Canby then hired several farm wagons, which she rigged with tent cloth hammocks to transport the wounded more comfortably. Her home became a hospital; her dining room an operating room where Confederate surgeons dressed wounds and performed amputations on shattered limbs while she herself served as nurse.

She also showed the Confederates where stores of blankets and food had been hidden, greatly alleviating their suffering.

On either April 1 or 2, General Sibley rode up from Albuquerque and thanked Mrs. Canby for caring for his men. It is likely he also reminisced about their earlier encounters when he and her husband had been on the same side. Canby and Sibley had graduated from West Point within a year of each other and had served together in several different posts before the war divided them. Soon after, the rebel troops began retreating southward. The 100 critically wounded left behind remained under the care of Mrs. Canby and the other officer’s wives until the Union army returned and took them in as prisoners of war. It was not a moment too soon: by then, the food stores in Santa Fe had been seriously depleted.

When some citizens objected to aiding the enemy, Mrs. Canby argued “Whether friend or foe, the wounded must be cared for. They are the sons of some dear mother.” What those citizens, and later detractors would fail to acknowledge was that, by providing aid to the wounded, Mrs. Canby and her group of women prevented the sack of Santa Fe. Its buildings and its people were left unharmed by the Confederate occupation because of her act of mercy. “Whether friend or foe, the wounded must be cared for. They are the sons of some dear mother.” After the war, Louisa Canby continued to follow her husband to posts in Washington D.C, Louisiana, Delaware, Maryland, Texas, North and South Carolina. and finally, Portland, Oregon, where she continued to work in her community. When he was killed by a Modoc leader named Captain Jack on April 11, she refused to leave her bed for a week. The people of Portland were so grateful and devoted to her that they raised $5,000 as a gift to help supplement her modest widow’s pension. Louisa devoted the last sixteen years of her life to promoting the memory of her husband and his many achievements. When she died, on June 27, 1889 at the age of 70, she was buried beside her husband in Indiana. Her will returned the full $5,000 to the people of Portland.

Louisa Hawkins Canby is but one of many historical figures that will appear in Peralta, the third book in Rebels Along the Rio Grande, Jennifer Bohnhoff's trilogy about the Civil War in New Mexico. Books 1 and 2, Valverde and Glorieta, are available in hardcover and ebook.

Louisa Hawkins Canby is but one of many historical figures that will appear in Peralta, the third book in Rebels Along the Rio Grande, Jennifer Bohnhoff's trilogy about the Civil War in New Mexico. Books 1 and 2, Valverde and Glorieta, are available in hardcover and ebook.

Published on January 04, 2021 00:00