Jennifer Bohnhoff's Blog, page 28

November 16, 2020

Civil War Gravestones

Some of the people in Valverde and Glorieta are fictitious, and therefore have no gravemarkers. They were never born, and they will never die as long as readers keep them alive.

Some of the people in Valverde and Glorieta are fictitious, and therefore have no gravemarkers. They were never born, and they will never die as long as readers keep them alive.But other characters in both stories were real people, with lives that began long before I wrote about them - lives that were filled with events that I didn't include in my novels.

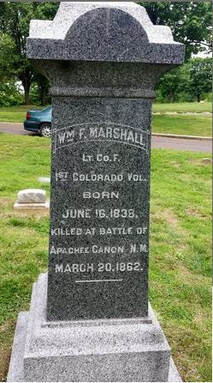

William Marshall, who has a small role in my novel Glorieta was the last man killed on the first day of the battle that raged on March 20 in Apache Canyon. He had survived the day's fighting and was collecting discarded Confederate weapons and disabling them when one went of, mortally wounding him. He is buried at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.

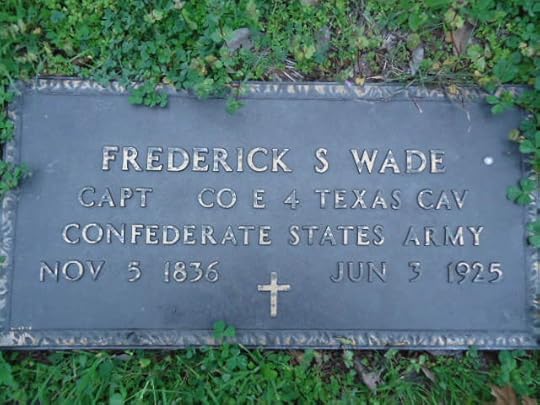

Frederick Wade and John Norvell, who both served with the fictional Jemmy Martin, survived the war and went on to live long and full lives. Their memories, published in newspaper accounts, helped give life to my novel Valverde.

Frederick Wade and John Norvell, who both served with the fictional Jemmy Martin, survived the war and went on to live long and full lives. Their memories, published in newspaper accounts, helped give life to my novel Valverde.

After resigning his commission with the Colorado Volunteers after the Battle of Valverde, John P. Slough was first given command of a brigade in the Shenandoah Valley, then was appointed brigadier general of volunteers and finally became the military governor of Alexandria, Virginia. When the war ended, President Andrew Johnson, appointed Slough to serve as chief justice of the New Mexico Territorial Court. Slough returned to New Mexico and helped fund the Civil War monument in Santa Fe that was recently torn down and the Veteran's Cemetery.

After resigning his commission with the Colorado Volunteers after the Battle of Valverde, John P. Slough was first given command of a brigade in the Shenandoah Valley, then was appointed brigadier general of volunteers and finally became the military governor of Alexandria, Virginia. When the war ended, President Andrew Johnson, appointed Slough to serve as chief justice of the New Mexico Territorial Court. Slough returned to New Mexico and helped fund the Civil War monument in Santa Fe that was recently torn down and the Veteran's Cemetery.Slough had a fiery temper and a keen sense of justice that often put him at odds with the locals. His decisions to accept Pueblo Indians as U. S. citizens who could testify in his court and his attacks on the peonage system led for some to call for his removal. Slough died when a member of the Territorial Legislative Council whom he had argued with shot him in a pool hall argument. He is buried in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Another character with a fiery temper was James "Paddy" Graydon, who appears in Valverde. Three years after the Civil War, Graydon was involved in controlling the Mescalero Apaches in southern New Mexico. After Surgeon John Whitlock accused him of needlessly killing a number of braves, the two ended up dueling at Fort Stanton. Graydon was killed, and Whitlock was then killed by Graydon's men. He was buried at Fort Stanton, but twenty-four years later his remains were reinterred at the Federal Cemetery in Santa Fe that Slough helped create. Like most Federal Veteran's Cemeteries, the one in Santa Fe contains row upon row of white headstones, giving it a look as uniform as a rank of soldiers. But there are a few exceptions. The most unique marker does not come from the Civil War period, but it deserves notice. It belongs to a Private named Dennis O’Leary, who died at Fort Wingate in 1901. According to local legend, O'Leary himself carved the statue, then committed suicide on the date he had inscribed. However, military records say he died of tuberculosis, a common illness of the period.

Another character with a fiery temper was James "Paddy" Graydon, who appears in Valverde. Three years after the Civil War, Graydon was involved in controlling the Mescalero Apaches in southern New Mexico. After Surgeon John Whitlock accused him of needlessly killing a number of braves, the two ended up dueling at Fort Stanton. Graydon was killed, and Whitlock was then killed by Graydon's men. He was buried at Fort Stanton, but twenty-four years later his remains were reinterred at the Federal Cemetery in Santa Fe that Slough helped create. Like most Federal Veteran's Cemeteries, the one in Santa Fe contains row upon row of white headstones, giving it a look as uniform as a rank of soldiers. But there are a few exceptions. The most unique marker does not come from the Civil War period, but it deserves notice. It belongs to a Private named Dennis O’Leary, who died at Fort Wingate in 1901. According to local legend, O'Leary himself carved the statue, then committed suicide on the date he had inscribed. However, military records say he died of tuberculosis, a common illness of the period.  Jennifer Bohnhoff is an educator and writer who lives in New Mexico. You can read more about her and her books here.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is an educator and writer who lives in New Mexico. You can read more about her and her books here.

Published on November 16, 2020 00:00

November 11, 2020

November 11: Birthday of a Famous Soldier

Patton at VMI I’m sure you all know that Veteran’s Day used to be called Armistice Day, and is set on the anniversary of the end of WWI. What you may not know, since it’s entirely coincidental if still appropriate, is that it’s also George S. Patton’s birthday. It seems fitting that we honor all veterans on the birthday of a man who devoted his life to military service.

Patton at VMI I’m sure you all know that Veteran’s Day used to be called Armistice Day, and is set on the anniversary of the end of WWI. What you may not know, since it’s entirely coincidental if still appropriate, is that it’s also George S. Patton’s birthday. It seems fitting that we honor all veterans on the birthday of a man who devoted his life to military service.

George Smith Patton Jr. was born into a life of privilege on November 11, 1885. His father was the district attorney for Los Angeles County and his mother was the daughter of Los Angeles’ first elected mayor. He went to VMI for one year before transferring to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, where he proved himself to be a mediocre student but a brilliant athlete. It’s ironic, and I’m sure not coincidental that Patton’s statue at West Point is placed with his back towards the library.

Did you that he was also an Olympian? Patton was the first American to compete in the Modern Pentathlon, a new event at the time of the 1912 Olympics held in Stockholm, Sweden. Inspired by the pentathlon of ancient Greece, in which a soldier carried a message over a long distance, riding horseback, swimming a river, and running, the event was only open to military personnel in 1912. Patton, a first lieutenant stationed at Fort Myer, Virginia, was chosen based on his track and field, fencing, sharpshooting performances at West Point. He placed twenty-first in the shooting, seventh in the swim, fourth in fencing, sixth in riding and third in running; not a good enough showing to earn a medal or much attention from the press.

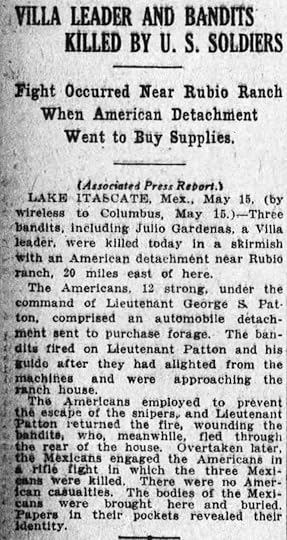

Did you that he was also an Olympian? Patton was the first American to compete in the Modern Pentathlon, a new event at the time of the 1912 Olympics held in Stockholm, Sweden. Inspired by the pentathlon of ancient Greece, in which a soldier carried a message over a long distance, riding horseback, swimming a river, and running, the event was only open to military personnel in 1912. Patton, a first lieutenant stationed at Fort Myer, Virginia, was chosen based on his track and field, fencing, sharpshooting performances at West Point. He placed twenty-first in the shooting, seventh in the swim, fourth in fencing, sixth in riding and third in running; not a good enough showing to earn a medal or much attention from the press.Patton did receive a lot of press for something that happened in 1916, when he was in Mexico during the Punitive Expedition against Pancho Villa. Patton was leading a foraging expedition to buy food for the American soldiers when one of his interpreters identified a man at one of the stops as a bandit. Patton began a search of nearby farms. He ended up in a gun battle with three men, one of whom was Julio Gardenas, a senior leader of Pancho Villa’s gang. All three of the Mexicans were killed. Patton had their bodies strapped the bodies to the hoods of Dodge Touring Cars they were driving, then returned to camp. It was probably the first time that an American used motor-vehicles in a military attack.

Patton, of course, went on to fame with larger vehicles than touring cars, and he continued to act audaciously, commanding attention from the press. Few veterans command attention like Patton did, but all deserve our attention and our appreciation.

Patton, of course, went on to fame with larger vehicles than touring cars, and he continued to act audaciously, commanding attention from the press. Few veterans command attention like Patton did, but all deserve our attention and our appreciation.

Published on November 11, 2020 06:00

November 2, 2020

Cranberry Orange Muffins

By November fall is definitely here. In New Mexico, October sees the glories of the Balloon Fiesta and the aspens and maples in the state change color. Even the cottonwoods in the bosque down near the Rio Grande have one glorious, golden season. But by November all that glory is usually over.

By November fall is definitely here. In New Mexico, October sees the glories of the Balloon Fiesta and the aspens and maples in the state change color. Even the cottonwoods in the bosque down near the Rio Grande have one glorious, golden season. But by November all that glory is usually over.These muffins will bring a little brightness back into your morning. The orange juice enlivens the batter and the cranberries give the muffins a nice burst of tartness.

Cranberry Orange Muffins

Mix together

2 eggs

1 1/2 tsp. vanilla

1/2 cup water

1/2 cup orange juice

1/2 cup oil

2 3/4 cups manic muffin mix

1 tbs orange peel

1/2 cup chopped pecans

1/2 cup dried cranberries

Preheat oven to 350. Line 18 muffin tins with paper muffin cups.

Mix the wet ingredients, then add the dry ingredients and stir until there are not dry areas left.

Fill muffin cups 3/4 of the way full. Bake for 25 minutes, until the tops of the muffins are browned a bit.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a writer and educator who lives in rural New Mexico. She is currently working on an historical novel set in New Mexico during the Civil War, and another one that takes place during World War 1.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a writer and educator who lives in rural New Mexico. She is currently working on an historical novel set in New Mexico during the Civil War, and another one that takes place during World War 1.Are you on her friends and family email list? Those who are got an ebook that compiles a year's worth of muffin recipes as a Christmas gift in 2019. If you'd like to join, fill out the form here.

Published on November 02, 2020 00:00

November 1, 2020

The Drummer Boy

A short story by Jennifer Bohnhoff,

based on the Characters in

her Historical Novel, Valverde

They lined up now, in three long rows behind the low sand hill. The front line, all 200 of them, prone against the hill while the back two lines, the second wave of 250 and the third wave of 300, squatted on their heels. Behind them, sergeants walked up and down, shouting at the men to make sure their guns had a priming cap in place, to shoot low, and not until they were within effective range.

They lined up now, in three long rows behind the low sand hill. The front line, all 200 of them, prone against the hill while the back two lines, the second wave of 250 and the third wave of 300, squatted on their heels. Behind them, sergeants walked up and down, shouting at the men to make sure their guns had a priming cap in place, to shoot low, and not until they were within effective range.

The whites of their eyes, Jemmy thought, then wondered where he’d heard that before.

Don’t shoot until you see the whites of their eyes.

He glanced right, at Jaspar Jones, whose hands trembled and whose eyes looked as round as a rabbit’s. Plenty of white showing, all the way around. Jones’d make a fine target if the Abolitionists were looking for the whites of his eyes. Jemmy looked past him at the line of men. Some twitched in anticipation of the fight to come. Some used the backs of their hands to wipe tears from their faces. Some prayed, their hands clutched together as their lips moved with the earnest intensity that only the doomed can know. Some men lay so still that he wondered if they’d gone to sleep.

Behind him, Colonel Green called for the men’s attention. The line quieted. Everyone trusted “Daddy” Green to do right by them.

“Boys,” he called, “I want Colonel Canby’s guns! When I yell, raise the Rebel yell and follow me!”

All along the line, men affirmed the Colonel, some with cheers and others with quiet “yes, sirs.” Jemmy felt his resolve harden into a knot in his throat. Afraid his voice would come out in a squeak, he nodded his assent.

He looked left and noticed Wee Willie squatting close by, his drumsticks clutched in his fists, his jaw set with a gritty determination that made the boy look old beyond his years. Willie’s pale skin looked even paler than usual, his black eyes sunken into his face. He was a curious one, that Willie: so small that Jemmy couldn’t look at him without wondering how his Mama could have let him run off to war. Some said he was an orphan, but that was just a rumor. Willie never spoke. He hung around the edges of the camp, eating what others offered him, sleeping on the floor of the Colonel’s tent like a pet pup.

Just beyond Willie, John Norvell and Frederick Wade hunkered shoulder to shoulder.

“Fred, we are whipped, and I will never see my mother again!” John said in between wracking sobs.

Jemmy closed his eyes, trying to wipe the image of Norvell’s tears from his mind. He raised one shoulder and then the other, lessening the tension in his back. The shoot low part bothered him. Sure, it was just fine if he did it. He was in the first line of men and there’d be nothing in front of him except blue coats. It didn’t matter if he hit them in the head or the kneecap. Shot was shot, and a Yank with a ball in him wouldn’t be trying to return the favor. But Jemmy wasn’t so sure he wanted the second or third waves of men, the men who came behind him, to be shooting low. He didn’t cotton to taking a ball in the back. Not from one of his own. Not when it might be mistaken as a mark that Jemmy was running from the Federal line instead of toward it. He didn’t want to be mistaken for a coward.

The ghostly sun, a pale disk behind thin, gray clouds, hung high overhead, a little past the apex. Snow had started again, tiny dry pellets brought in almost horizontal that it bit his cheeks and made his eyes water. Why did the wind have to come from the west today? Why couldn’t it be at his back, pushing him on towards victory? It seemed like God himself was against him.

He stretched his neck, thrusting his chin forward so he could look over the top of the hill without exposing the crown of his head. There, not 800 yards from him, Federal cannons pointed directly at him, their open muzzles looking like astonished mouths. Soon, he knew, they’d be belching fire at him. Fire, and deadly chunks of metal.

Jemmy shook his head hard. He had to stop talking scary to himself or he was going to end up like Norvell or Jones. Shaking his head didn’t dislodge the images that swirled around in his head like ghost stories. He knew he needed to hear the sound of his own voice, to talk himself calm like he did with his mules.

“You ain’t got nothing to be scairt of,” he told himself in as convincing a manner as he could muster. “The men behind you is there to support you, not shoot you in the back. And the snow and wind? It done mask our sound. It’ll confuse the Federals into thinking there’re less of us than there are. An’ grapeshot and canister’s aimed at the generals and such. Them cannons ain’t interested in a little guy like me.”

Jemmy gave his head a firm nod, but ghastly, terrifying images kept pushing his convictions from him. He frowned. If he couldn’t be brave from himself, perhaps he could be brave for someone else. He grabbed We Willie’s shoulder, pulling the drummer boy into a side embrace.

“This here’s your first fight, son, but you got nothing to be scairt of,” Jemmy said, more to himself than to Willie. “God’s on our side, sure as shoot’n. He ain’t going to let us down. When we let go our rebel yell, them Abs’ll skedaddle back to their fort with their tails between their legs and we’ll take possession of those fine guns. So don’t you worry none. It’s on to San Francisco for us.”

Jemmy pounded the drummer boy into his side with a series of encouraging whacks. He didn’t know if he had said anything to calm Wee Willie, but he was beginning to feel better already.

Willie pulled away from Jemmy. He scrambled back to his feet. He held up his fists, the sticks ready to beat the advance, sending men over the hill and into the cannon’s line of fire.

“You are mistaken, Private.” Willie’s little voice lilted as high and light as birdsong. The sound of it surprised Jemmy. He was sure this was the first time he’d ever heard the drummer boy speak. “This is not my first fight. I have been leading men into battle since time immemorial. It was I who beat the advance at Waterloo. I who beat at Yorktown. At Agincourt. And Thermopylae. But you are right in one respect: I have nothing to be afraid of.”

The boy pulled back his lips in a grin that was more grimace, and the two rows of teeth gave his pale face a skull-like appearance. Jemmy swore that his eyes gleamed a bright and burning red. Jemmy’s mouth dropped open in astonishment, but before he could draw breath, Colonel Green’s voice filled his ears.

“Up, boys, and at ‘em!”

Wee Willie beat the advance and two hundred men bellowed the rebel yell and clambered over the hill.

based on the Characters in

her Historical Novel, Valverde

They lined up now, in three long rows behind the low sand hill. The front line, all 200 of them, prone against the hill while the back two lines, the second wave of 250 and the third wave of 300, squatted on their heels. Behind them, sergeants walked up and down, shouting at the men to make sure their guns had a priming cap in place, to shoot low, and not until they were within effective range.

They lined up now, in three long rows behind the low sand hill. The front line, all 200 of them, prone against the hill while the back two lines, the second wave of 250 and the third wave of 300, squatted on their heels. Behind them, sergeants walked up and down, shouting at the men to make sure their guns had a priming cap in place, to shoot low, and not until they were within effective range. The whites of their eyes, Jemmy thought, then wondered where he’d heard that before.

Don’t shoot until you see the whites of their eyes.

He glanced right, at Jaspar Jones, whose hands trembled and whose eyes looked as round as a rabbit’s. Plenty of white showing, all the way around. Jones’d make a fine target if the Abolitionists were looking for the whites of his eyes. Jemmy looked past him at the line of men. Some twitched in anticipation of the fight to come. Some used the backs of their hands to wipe tears from their faces. Some prayed, their hands clutched together as their lips moved with the earnest intensity that only the doomed can know. Some men lay so still that he wondered if they’d gone to sleep.

Behind him, Colonel Green called for the men’s attention. The line quieted. Everyone trusted “Daddy” Green to do right by them.

“Boys,” he called, “I want Colonel Canby’s guns! When I yell, raise the Rebel yell and follow me!”

All along the line, men affirmed the Colonel, some with cheers and others with quiet “yes, sirs.” Jemmy felt his resolve harden into a knot in his throat. Afraid his voice would come out in a squeak, he nodded his assent.

He looked left and noticed Wee Willie squatting close by, his drumsticks clutched in his fists, his jaw set with a gritty determination that made the boy look old beyond his years. Willie’s pale skin looked even paler than usual, his black eyes sunken into his face. He was a curious one, that Willie: so small that Jemmy couldn’t look at him without wondering how his Mama could have let him run off to war. Some said he was an orphan, but that was just a rumor. Willie never spoke. He hung around the edges of the camp, eating what others offered him, sleeping on the floor of the Colonel’s tent like a pet pup.

Just beyond Willie, John Norvell and Frederick Wade hunkered shoulder to shoulder.

“Fred, we are whipped, and I will never see my mother again!” John said in between wracking sobs.

Jemmy closed his eyes, trying to wipe the image of Norvell’s tears from his mind. He raised one shoulder and then the other, lessening the tension in his back. The shoot low part bothered him. Sure, it was just fine if he did it. He was in the first line of men and there’d be nothing in front of him except blue coats. It didn’t matter if he hit them in the head or the kneecap. Shot was shot, and a Yank with a ball in him wouldn’t be trying to return the favor. But Jemmy wasn’t so sure he wanted the second or third waves of men, the men who came behind him, to be shooting low. He didn’t cotton to taking a ball in the back. Not from one of his own. Not when it might be mistaken as a mark that Jemmy was running from the Federal line instead of toward it. He didn’t want to be mistaken for a coward.

The ghostly sun, a pale disk behind thin, gray clouds, hung high overhead, a little past the apex. Snow had started again, tiny dry pellets brought in almost horizontal that it bit his cheeks and made his eyes water. Why did the wind have to come from the west today? Why couldn’t it be at his back, pushing him on towards victory? It seemed like God himself was against him.

He stretched his neck, thrusting his chin forward so he could look over the top of the hill without exposing the crown of his head. There, not 800 yards from him, Federal cannons pointed directly at him, their open muzzles looking like astonished mouths. Soon, he knew, they’d be belching fire at him. Fire, and deadly chunks of metal.

Jemmy shook his head hard. He had to stop talking scary to himself or he was going to end up like Norvell or Jones. Shaking his head didn’t dislodge the images that swirled around in his head like ghost stories. He knew he needed to hear the sound of his own voice, to talk himself calm like he did with his mules.

“You ain’t got nothing to be scairt of,” he told himself in as convincing a manner as he could muster. “The men behind you is there to support you, not shoot you in the back. And the snow and wind? It done mask our sound. It’ll confuse the Federals into thinking there’re less of us than there are. An’ grapeshot and canister’s aimed at the generals and such. Them cannons ain’t interested in a little guy like me.”

Jemmy gave his head a firm nod, but ghastly, terrifying images kept pushing his convictions from him. He frowned. If he couldn’t be brave from himself, perhaps he could be brave for someone else. He grabbed We Willie’s shoulder, pulling the drummer boy into a side embrace.

“This here’s your first fight, son, but you got nothing to be scairt of,” Jemmy said, more to himself than to Willie. “God’s on our side, sure as shoot’n. He ain’t going to let us down. When we let go our rebel yell, them Abs’ll skedaddle back to their fort with their tails between their legs and we’ll take possession of those fine guns. So don’t you worry none. It’s on to San Francisco for us.”

Jemmy pounded the drummer boy into his side with a series of encouraging whacks. He didn’t know if he had said anything to calm Wee Willie, but he was beginning to feel better already.

Willie pulled away from Jemmy. He scrambled back to his feet. He held up his fists, the sticks ready to beat the advance, sending men over the hill and into the cannon’s line of fire.

“You are mistaken, Private.” Willie’s little voice lilted as high and light as birdsong. The sound of it surprised Jemmy. He was sure this was the first time he’d ever heard the drummer boy speak. “This is not my first fight. I have been leading men into battle since time immemorial. It was I who beat the advance at Waterloo. I who beat at Yorktown. At Agincourt. And Thermopylae. But you are right in one respect: I have nothing to be afraid of.”

The boy pulled back his lips in a grin that was more grimace, and the two rows of teeth gave his pale face a skull-like appearance. Jemmy swore that his eyes gleamed a bright and burning red. Jemmy’s mouth dropped open in astonishment, but before he could draw breath, Colonel Green’s voice filled his ears.

“Up, boys, and at ‘em!”

Wee Willie beat the advance and two hundred men bellowed the rebel yell and clambered over the hill.

Published on November 01, 2020 13:39

October 26, 2020

The Ghosts of Valverde

A short story by Jennifer Bohnhoff,

based on the characters in

Valverde, book 1 of the

Rebels Along the Rio Grande Trilogy

Raul waited until heard the servant slip the timber into the braces, blocking the door. One couldn’t be too careful these days. The Confederates who’d been too sick or injured to head north after the Battle of Valverde had been in Socorro nearly two months, long enough to heal and wander the town looking for a little whiskey, a fight to pick, or a girl. Willing or unwilling didn’t matter. Anything to relieve their boredom. Mama was still young enough, and beautiful enough, to attract attention.

He looked up and down the dusty street. Finding it empty, he hitched the basket into the crook of his arm and headed toward San Miguel church, where he turned into the graveyard. Raul set the basket atop a sandy mound that had already begun to cement itself together again, healing like the girl beneath it never would. An image of Lupe stretched on her bed flashed into Raul’s mind. He moved the basket, horrified he might have placed it on her chest. He straightened and scanned the road. He hadn’t been followed.

“Mama told me to give this to you. She misses you. So do I.” Raul stuck his hand into the basket and pulled out a tortilla. He folded it in quarters and set it on the grave. Raul sat back on his heels and stared at the bit of bread. Lupe was beyond eating anything, ever again. Still, there was comfort in sharing with her. She had died at such a difficult time that none of the usual observances had happened; quickly buried, with no velorios, no neighbors bringing food, nothing to attract the attention of the Confederates. It had been a hard and lonely time for Mama, made harder by her husband and brother’s absence. There was not much that the two men agreed on, but they had appeared to be of one accord in hiding of the flock and stock from the Confederates. Raul tilted his head back, scanning high in the hills. Was either Papa or Tio watching him? Which one he should he be watching himself? They were so different from one another; he could not follow both.

A little whirlwind rose up, scoured from the earth by the afternoon heat. At the first sting of sand on his face, Raul closed his eyes and waited for it to pass. When he opened them again, the tortilla was covered with a fine dusting of grit. Raul stood up and dusted his trousers. The mice, or racoons, or whatever it was that ate the ofrendas left for the dead wouldn’t mind a little dirt with their meal.

He crossed to the low adobe wall at the back of the graveyard and looked around once more to be sure that no one watched before he sat atop it and swung his legs over. From the back of the church, he climbed into the hills, checking over his shoulder several times to see if he was being followed. The town seemed asleep, dazed by the heat of the day. Raul pulled the neckerchief from around his neck and mopped his face as another whirlwind rose into a swirling column of dirt, struck a gravestone, and collapsed on itself, dying almost before it had begun. It was only April, but already afternoons had become oppressive enough to create dust devils, diablos de polvo.

Raul dropped over a ridge and the village disappeared from sight. He scrambled up a sandy arroyo as it wound up into the hills. Gasping for breath, he switched the basket to his other arm.

“Mi’jo, you sound like an entire troop of soldiers,” a voice said from somewhere above him. Raul twisted his head back and saw his father, Cresenio, silhouetted against the sky.

“It’s this loose rock. It crunches and rolls under your feet.” Raul gestured down, and his father snorted.

“That, and you’re gasping like the bellows in the blacksmith’s shop. You don’t get out enough. You’re getting soft, like your uncle. Pretty soon, you’ll be good for nothing but balancing account books and arguing in court.”

Cresenio leaped down from the boulder and led the way up the arroyo. Raul slipped and slid as he struggled to keep up. His short legs could not match his father’s long strides, but he didn’t dare ask his father to slow down. Crescenio snapped his head to one side so that his words carried over his shoulder. “It’s a good thing it’s me who heard you coming, not some Apache. You would have looked like a porcupine by now.”

“You seen any Apaches?” Raul shaded his eyes and scanned the hills, which shimmered in the heat, making it almost impossible to pick out movement. He stumbled, nearly dropping the basket.

“I seen nothing.” Crescenio spit contemptuously, his voice tinged with bitterness. “No Indians. No soldiers, Union or Confederate. We’re wasting our time up here. But your uncle, he is too afraid of the Confederates.”

“Not much to be afraid of, at least for us men,” Raul said as he panted for breath. “Most are just limping, hollow-eyed skeletons. The rest are buried outside of town. Father Sanchez wouldn’t let them be buried in the churchyard.”

“They’re not the ones Tio’s afraid of.” Crescenio jerked his chin north, indicating the thin, green line delineating the bosque that flanked the Rio Grande. Somewhere down there, a defeated Confederate Army was limping its way back towards Texas. Raul had heard the rumors. Everyone in town had, and all eyes scanned the northern horizon for a return of the dust cloud that hung over an army on the move.

The arroyo made a sudden turn and entered a deep bowl hidden by steep walls. Zorro and Torro, the two blue-eyed sheepdogs, appeared out of the grass and growled. Crescenio snarled a command, so they circled and dropped back into the grass, content they had fulfilled their guard duties. Cattle and sheep ranged throughout the bowl, mowing the spring grass. Raul noted a couple of Tio’s shepherds perched on rocks high in the walls, rifles across their knees, their broadbrimmed hats tipped forward so that he couldn’t tell whether they were awake or asleep. At the back of the valley, where two cottonwoods kept watch over a small, spring-fed pond, Tio Pedro sat on the stairs of the little, round-topped wagon that the herders now shared with their employer and his brother-in-law-bodyguard. It was surely a tight fit.

The arroyo made a sudden turn and entered a deep bowl hidden by steep walls. Zorro and Torro, the two blue-eyed sheepdogs, appeared out of the grass and growled. Crescenio snarled a command, so they circled and dropped back into the grass, content they had fulfilled their guard duties. Cattle and sheep ranged throughout the bowl, mowing the spring grass. Raul noted a couple of Tio’s shepherds perched on rocks high in the walls, rifles across their knees, their broadbrimmed hats tipped forward so that he couldn’t tell whether they were awake or asleep. At the back of the valley, where two cottonwoods kept watch over a small, spring-fed pond, Tio Pedro sat on the stairs of the little, round-topped wagon that the herders now shared with their employer and his brother-in-law-bodyguard. It was surely a tight fit.

“Ah! You’ve captured a spy,” Tio Pedro said playfully. He set down the book that had been cradled in his lap and held out his hand. “I say we confiscate his basket and see what’s in it. How is that sister of mine?”

“She is lonely and bored, and still very sad,” Raul answered.

“But safe? And well? And Arsenio?” Crescenio demanded.

“Mama is safe. And well. And Arsenio is recovering.” Raul saw the slight tic of relief that his father didn’t want him to see. Crescenio wanted everyone to think he was steely and strong, but underneath the sharp exterior lay a man who loved his bubbly, vivacious wife, grieved for the daughter he had lost, and worried still for the son who had nearly accompanied his sister in death.

“We should be with her.” Crescenio gave his brother-in-law a sharp, sidewise glance.

“Not until those Texicans have passed through.” Tio responded, in an equally sharp tone. Clearly, that this was an argument they had often.

“What? You don’t want to sell to them as they pass through town? From what I hear, they are desperate for food.” Crescenio asked mockingly.

“If they had any money, I might consider it. But their paper money is no better than their word, and their coin long gone. And desperate men are dangerous men. Better to stay here.” Tio Pedro pulled back the cloth that covered the basket and chuckled with satisfaction. He pulled out a tortilla and ate it. When it was gone, he handed one each to Crescenio and Raul, then tossed a couple to the sheepherders, who had silently drifted down from their rock perches and were hovering nearby. Raul rolled his tortilla and nibbled on the end, his eyes darting between his uncle and his father as he appraised them both.

Tio Baca was one of the richest men in town, and his thoughts always centered on his money and how he could make more. He worried less about whether the Union or the Confederates could hold the little town of Socorro than he did about which side could pay the most for his goods. Raul’s father, on the other hand, had come from poor stock, and prized his pride more than money. He hated both the Northerners and the Southerners, and wanted both out of New Mexico. Raul sat between the two men, pulled first towards the argument of one and then the other.

The wind picked up at the opening of the box canyon, ruffling Zorro and Torro’s coats. Raul watched it swirl into a column of grass bits and dust. The hair on the back of his head rose. A tingle ran up his spine.

“It’s been a strange year. Extra cold this winter, but little snow. And now, diablos de polvo, this early,” Tio said. “Know what the Navajo call them? Chiindii. Spirits.”

Crescenio shivered and crossed himself. “Don’t go talking about spirits. Not with all the deaths we’ve had.”

Tio Baca laughed. “Surely you don’t believe in ghosts! They went the way of the Inquisition, and witches. We’re living in the age of science, now!”

“There are plenty of things left that your Galilleos can’t explain,” Crescenio said with a snarl.

Raul set his tortilla aside, unnerved by the argument. He didn’t want to think about ghosts, not with the faces of so many dead men haunting his dreams at night. Ever since the battle at Valverde Ford, he had found himself jerking up from his sleeping mat, gasping for breath like a drowning man, his heart pounding, his body soaked with sweat. The faces, blood smeared and broken, hovered over him long after he awakened, and he would find himself outside, staring at the stars as he tried to calm himself. But stars reminded him of the thousand Confederate fires he had seen while standing on the parapet at Fort Craig, and that memory would start his heart pounding once again.

Raul felt his heart pounding now as he got to his feet and left the argument behind him. Maybe his father was right, and the world of the dead existed here, beside his own. Maybe his uncle was right, and there were no such things as ghosts. The dead were just dead. He would have to side with one man or the other on this, as he would have to decide which was right on the question of foreigners in his land, and how he was to live his life. He loved and honored both men. How could he choose between them?

Zorro and Torro raised their heads and watched him pass between them with suspicious and hopeful eyes. When he was beyond the protection of the canyon, Raul sat on a boulder and stared at the immense land spread before him, the parallel lines of mountains and bosque snaking northward towards a distant horizon. The wind picked up again, whistling through the rocks and forming another dust devil. This one seemed to hover in front of him, shimmering and shifting until it almost coalesced into a figure of a young girl.

“Lupe?” His sister’s name slipped from his lips, half gasp and half prayer. Though barely audible, it seemed to have the strength to make the wind collapse on itself, dissolving into nothingness. Raul stared at the place where the shape had been, and saw, far in the distance, flashes of metal like a thousand falling stars amid a faint cloud of drifting dust. The time for indecisiveness was over.

Thank you for reading my short story. If it intrigues you, please join my friends, fans and family newsletter list or visit my website so that you can learn more about my work. You can buy Valverde here.

Thank you for reading my short story. If it intrigues you, please join my friends, fans and family newsletter list or visit my website so that you can learn more about my work. You can buy Valverde here.

based on the characters in

Valverde, book 1 of the

Rebels Along the Rio Grande Trilogy

Raul waited until heard the servant slip the timber into the braces, blocking the door. One couldn’t be too careful these days. The Confederates who’d been too sick or injured to head north after the Battle of Valverde had been in Socorro nearly two months, long enough to heal and wander the town looking for a little whiskey, a fight to pick, or a girl. Willing or unwilling didn’t matter. Anything to relieve their boredom. Mama was still young enough, and beautiful enough, to attract attention.

He looked up and down the dusty street. Finding it empty, he hitched the basket into the crook of his arm and headed toward San Miguel church, where he turned into the graveyard. Raul set the basket atop a sandy mound that had already begun to cement itself together again, healing like the girl beneath it never would. An image of Lupe stretched on her bed flashed into Raul’s mind. He moved the basket, horrified he might have placed it on her chest. He straightened and scanned the road. He hadn’t been followed.

“Mama told me to give this to you. She misses you. So do I.” Raul stuck his hand into the basket and pulled out a tortilla. He folded it in quarters and set it on the grave. Raul sat back on his heels and stared at the bit of bread. Lupe was beyond eating anything, ever again. Still, there was comfort in sharing with her. She had died at such a difficult time that none of the usual observances had happened; quickly buried, with no velorios, no neighbors bringing food, nothing to attract the attention of the Confederates. It had been a hard and lonely time for Mama, made harder by her husband and brother’s absence. There was not much that the two men agreed on, but they had appeared to be of one accord in hiding of the flock and stock from the Confederates. Raul tilted his head back, scanning high in the hills. Was either Papa or Tio watching him? Which one he should he be watching himself? They were so different from one another; he could not follow both.

A little whirlwind rose up, scoured from the earth by the afternoon heat. At the first sting of sand on his face, Raul closed his eyes and waited for it to pass. When he opened them again, the tortilla was covered with a fine dusting of grit. Raul stood up and dusted his trousers. The mice, or racoons, or whatever it was that ate the ofrendas left for the dead wouldn’t mind a little dirt with their meal.

He crossed to the low adobe wall at the back of the graveyard and looked around once more to be sure that no one watched before he sat atop it and swung his legs over. From the back of the church, he climbed into the hills, checking over his shoulder several times to see if he was being followed. The town seemed asleep, dazed by the heat of the day. Raul pulled the neckerchief from around his neck and mopped his face as another whirlwind rose into a swirling column of dirt, struck a gravestone, and collapsed on itself, dying almost before it had begun. It was only April, but already afternoons had become oppressive enough to create dust devils, diablos de polvo.

Raul dropped over a ridge and the village disappeared from sight. He scrambled up a sandy arroyo as it wound up into the hills. Gasping for breath, he switched the basket to his other arm.

“Mi’jo, you sound like an entire troop of soldiers,” a voice said from somewhere above him. Raul twisted his head back and saw his father, Cresenio, silhouetted against the sky.

“It’s this loose rock. It crunches and rolls under your feet.” Raul gestured down, and his father snorted.

“That, and you’re gasping like the bellows in the blacksmith’s shop. You don’t get out enough. You’re getting soft, like your uncle. Pretty soon, you’ll be good for nothing but balancing account books and arguing in court.”

Cresenio leaped down from the boulder and led the way up the arroyo. Raul slipped and slid as he struggled to keep up. His short legs could not match his father’s long strides, but he didn’t dare ask his father to slow down. Crescenio snapped his head to one side so that his words carried over his shoulder. “It’s a good thing it’s me who heard you coming, not some Apache. You would have looked like a porcupine by now.”

“You seen any Apaches?” Raul shaded his eyes and scanned the hills, which shimmered in the heat, making it almost impossible to pick out movement. He stumbled, nearly dropping the basket.

“I seen nothing.” Crescenio spit contemptuously, his voice tinged with bitterness. “No Indians. No soldiers, Union or Confederate. We’re wasting our time up here. But your uncle, he is too afraid of the Confederates.”

“Not much to be afraid of, at least for us men,” Raul said as he panted for breath. “Most are just limping, hollow-eyed skeletons. The rest are buried outside of town. Father Sanchez wouldn’t let them be buried in the churchyard.”

“They’re not the ones Tio’s afraid of.” Crescenio jerked his chin north, indicating the thin, green line delineating the bosque that flanked the Rio Grande. Somewhere down there, a defeated Confederate Army was limping its way back towards Texas. Raul had heard the rumors. Everyone in town had, and all eyes scanned the northern horizon for a return of the dust cloud that hung over an army on the move.

The arroyo made a sudden turn and entered a deep bowl hidden by steep walls. Zorro and Torro, the two blue-eyed sheepdogs, appeared out of the grass and growled. Crescenio snarled a command, so they circled and dropped back into the grass, content they had fulfilled their guard duties. Cattle and sheep ranged throughout the bowl, mowing the spring grass. Raul noted a couple of Tio’s shepherds perched on rocks high in the walls, rifles across their knees, their broadbrimmed hats tipped forward so that he couldn’t tell whether they were awake or asleep. At the back of the valley, where two cottonwoods kept watch over a small, spring-fed pond, Tio Pedro sat on the stairs of the little, round-topped wagon that the herders now shared with their employer and his brother-in-law-bodyguard. It was surely a tight fit.

The arroyo made a sudden turn and entered a deep bowl hidden by steep walls. Zorro and Torro, the two blue-eyed sheepdogs, appeared out of the grass and growled. Crescenio snarled a command, so they circled and dropped back into the grass, content they had fulfilled their guard duties. Cattle and sheep ranged throughout the bowl, mowing the spring grass. Raul noted a couple of Tio’s shepherds perched on rocks high in the walls, rifles across their knees, their broadbrimmed hats tipped forward so that he couldn’t tell whether they were awake or asleep. At the back of the valley, where two cottonwoods kept watch over a small, spring-fed pond, Tio Pedro sat on the stairs of the little, round-topped wagon that the herders now shared with their employer and his brother-in-law-bodyguard. It was surely a tight fit.“Ah! You’ve captured a spy,” Tio Pedro said playfully. He set down the book that had been cradled in his lap and held out his hand. “I say we confiscate his basket and see what’s in it. How is that sister of mine?”

“She is lonely and bored, and still very sad,” Raul answered.

“But safe? And well? And Arsenio?” Crescenio demanded.

“Mama is safe. And well. And Arsenio is recovering.” Raul saw the slight tic of relief that his father didn’t want him to see. Crescenio wanted everyone to think he was steely and strong, but underneath the sharp exterior lay a man who loved his bubbly, vivacious wife, grieved for the daughter he had lost, and worried still for the son who had nearly accompanied his sister in death.

“We should be with her.” Crescenio gave his brother-in-law a sharp, sidewise glance.

“Not until those Texicans have passed through.” Tio responded, in an equally sharp tone. Clearly, that this was an argument they had often.

“What? You don’t want to sell to them as they pass through town? From what I hear, they are desperate for food.” Crescenio asked mockingly.

“If they had any money, I might consider it. But their paper money is no better than their word, and their coin long gone. And desperate men are dangerous men. Better to stay here.” Tio Pedro pulled back the cloth that covered the basket and chuckled with satisfaction. He pulled out a tortilla and ate it. When it was gone, he handed one each to Crescenio and Raul, then tossed a couple to the sheepherders, who had silently drifted down from their rock perches and were hovering nearby. Raul rolled his tortilla and nibbled on the end, his eyes darting between his uncle and his father as he appraised them both.

Tio Baca was one of the richest men in town, and his thoughts always centered on his money and how he could make more. He worried less about whether the Union or the Confederates could hold the little town of Socorro than he did about which side could pay the most for his goods. Raul’s father, on the other hand, had come from poor stock, and prized his pride more than money. He hated both the Northerners and the Southerners, and wanted both out of New Mexico. Raul sat between the two men, pulled first towards the argument of one and then the other.

The wind picked up at the opening of the box canyon, ruffling Zorro and Torro’s coats. Raul watched it swirl into a column of grass bits and dust. The hair on the back of his head rose. A tingle ran up his spine.

“It’s been a strange year. Extra cold this winter, but little snow. And now, diablos de polvo, this early,” Tio said. “Know what the Navajo call them? Chiindii. Spirits.”

Crescenio shivered and crossed himself. “Don’t go talking about spirits. Not with all the deaths we’ve had.”

Tio Baca laughed. “Surely you don’t believe in ghosts! They went the way of the Inquisition, and witches. We’re living in the age of science, now!”

“There are plenty of things left that your Galilleos can’t explain,” Crescenio said with a snarl.

Raul set his tortilla aside, unnerved by the argument. He didn’t want to think about ghosts, not with the faces of so many dead men haunting his dreams at night. Ever since the battle at Valverde Ford, he had found himself jerking up from his sleeping mat, gasping for breath like a drowning man, his heart pounding, his body soaked with sweat. The faces, blood smeared and broken, hovered over him long after he awakened, and he would find himself outside, staring at the stars as he tried to calm himself. But stars reminded him of the thousand Confederate fires he had seen while standing on the parapet at Fort Craig, and that memory would start his heart pounding once again.

Raul felt his heart pounding now as he got to his feet and left the argument behind him. Maybe his father was right, and the world of the dead existed here, beside his own. Maybe his uncle was right, and there were no such things as ghosts. The dead were just dead. He would have to side with one man or the other on this, as he would have to decide which was right on the question of foreigners in his land, and how he was to live his life. He loved and honored both men. How could he choose between them?

Zorro and Torro raised their heads and watched him pass between them with suspicious and hopeful eyes. When he was beyond the protection of the canyon, Raul sat on a boulder and stared at the immense land spread before him, the parallel lines of mountains and bosque snaking northward towards a distant horizon. The wind picked up again, whistling through the rocks and forming another dust devil. This one seemed to hover in front of him, shimmering and shifting until it almost coalesced into a figure of a young girl.

“Lupe?” His sister’s name slipped from his lips, half gasp and half prayer. Though barely audible, it seemed to have the strength to make the wind collapse on itself, dissolving into nothingness. Raul stared at the place where the shape had been, and saw, far in the distance, flashes of metal like a thousand falling stars amid a faint cloud of drifting dust. The time for indecisiveness was over.

Thank you for reading my short story. If it intrigues you, please join my friends, fans and family newsletter list or visit my website so that you can learn more about my work. You can buy Valverde here.

Thank you for reading my short story. If it intrigues you, please join my friends, fans and family newsletter list or visit my website so that you can learn more about my work. You can buy Valverde here.

Published on October 26, 2020 00:00

October 11, 2020

October 5, 2020

Isaac Lynde: The Wrong Man for the Job

If there was ever a man who suffered by being placed in the wrong place at the wrong time, it was Isaac Lynde.

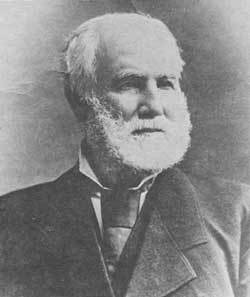

If there was ever a man who suffered by being placed in the wrong place at the wrong time, it was Isaac Lynde.Lynde was born July 27, 1804, in Williamstown, Vermont. He must have been a promising lad, for in 1822 he secured an appointment to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. The Academy’s records describe him as "an intelligent, sprightly lad," handsome, and well educated,” and he graduated four years later, thirty-second in a class of thirty-eight.

Lynde’s early career was typical for the time. He served in a number of frontier posts in the Northwest and the far plains, and took part in the Mexican-American War. Unlike many of his time, though Lynde’s record includes no battles or distinction of any kind, and in thirty-four years of service he had risen only three full grades, to Major. All of his promotions were routine, and based on time of service, his appointments to posts that were out of the way and relatively underutilized. Why this was the case cannot be said with any certainty. Perhaps he was not as promising as his youth had indicated, or perhaps his problem was that he was an infantry man in an Army that was giving all its plum assignments to the cavalry. At any case, by the time the Civil War was brewing, Lynde was at the end of his career and looking forward to retiring on a pension and settling into obscurity.

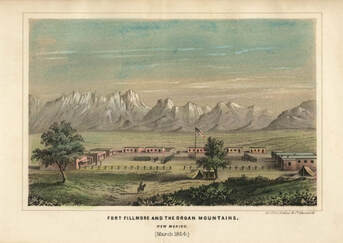

Circumstances, however, were not going to allow Lynde to retire quietly. In June 1861, the Union Army in New Mexico Territory faced a huge dilemma. Many officers and soldiers, including William Loring, the Commander of the Department of New Mexico, had resigned their posts and joined the Confederate Army. This left such a serious shortage of troops that E.R.S. Canby, Loring’s replacement, was forced to close forts created primarily to protect settlers from Indian attack and concentrate men in those forts most likely to lie along the path an invading Confederate army might take. Canby ordered Major Isaac Lynde then in command of the 7th Infantry, to abandon Fort McLane, south of Silver City, and take command of Fort Fillmore, six miles from the town of Mesilla. Canby warned Lynde that his new post was endangered not only by a possible invasion from Texas, but because the civilian population of Mesilla Valley sympathized strongly with the Southern cause. It was a crucial post to hold because it controlled the stage road on which U.S. troops would use to withdraw from Arizona. It was also the last Union holding that officers leaving New Mexico to join the Confederacy passed through, and the first objective for a Confederate advance into New Mexico. Lynde was given full responsibility for the area, including the right to decide whether to attack or ignore El Paso’s Fort Bliss, forty miles to the south and in secessionist hands.

When Major Lynde arrived at his new post in the first week of July, he found it woefully inadequate. Lynde noted that Fort Fillmore was located in a basin surrounded by sand hills, so that artillery could fire down into it. The hills were covered by dense growth that would allow a thousand men to approach undetected to within 500 yards. Next to the fort, a sweep of level land was ideal for attacking cavalry. Furthermore, the fort had no walls or ramparts. Shaped like a U, its open end faced the river and the road from El Paso. Because water had to be carried up from the river, a mile and a half to west, the fort could not stand a siege. He wrote to Canby that he thought the fort was poorly situated for defense, and it was not worth the exertion it would take to hold it.

When Major Lynde arrived at his new post in the first week of July, he found it woefully inadequate. Lynde noted that Fort Fillmore was located in a basin surrounded by sand hills, so that artillery could fire down into it. The hills were covered by dense growth that would allow a thousand men to approach undetected to within 500 yards. Next to the fort, a sweep of level land was ideal for attacking cavalry. Furthermore, the fort had no walls or ramparts. Shaped like a U, its open end faced the river and the road from El Paso. Because water had to be carried up from the river, a mile and a half to west, the fort could not stand a siege. He wrote to Canby that he thought the fort was poorly situated for defense, and it was not worth the exertion it would take to hold it. On July 25, Lynde was forced into action when Confederate Lieutenant Colonel John Baylor brought his 2nd Texas Mounted Rifles to Mesilla. Lynde left one company of infantry and the band to hold the fort. He crossed the Rio Grande with a force of three hundred and eighty men and four howitzers. He lined his men up in a cornfield, then sent his aide forward with a white flag to demand that the Confederates surrender. The Confederates replied that if Lynde wanted Mesilla, he was to come and get it. Lynde then fired his howitzers, whose shells burst short in the air. The Mayor of Mesilla came out and reminded Lynde that killing the women and children who sheltered in the town would look very bad and would not win Lynde any allies among the people. After a few exchanges of musket fire, and a small number of casualties on both sides, Lynde withdrew to the fort as evening fell.

On July 25, Lynde was forced into action when Confederate Lieutenant Colonel John Baylor brought his 2nd Texas Mounted Rifles to Mesilla. Lynde left one company of infantry and the band to hold the fort. He crossed the Rio Grande with a force of three hundred and eighty men and four howitzers. He lined his men up in a cornfield, then sent his aide forward with a white flag to demand that the Confederates surrender. The Confederates replied that if Lynde wanted Mesilla, he was to come and get it. Lynde then fired his howitzers, whose shells burst short in the air. The Mayor of Mesilla came out and reminded Lynde that killing the women and children who sheltered in the town would look very bad and would not win Lynde any allies among the people. After a few exchanges of musket fire, and a small number of casualties on both sides, Lynde withdrew to the fort as evening fell. That night, Lynde decided that the only hope of saving his troops from capture was in abandoning the fort and reaching another military post. He ordered the evacuation, set the fort on fire to stop it and its supplies from falling into enemy hands, and at one in the morning began the march up and over the Organ Mountains to Fort Stanton. Lynde had never taken this road, but he believed that San Augustine was only twenty miles away, just over a pass in the mountains. The march went well until the sun rose on a hot July day. Then the distance proved to be much longer and the water much scarcer than Lynde had believed. As Baylor’s men followed along, they found the road lined with guns, cartridge boxes, and men who were almost dying from fatigue and thirst. The memoirs of Hank Smith, a private soldier on the Confederate side, suggest that many of the men were drunk, and suggests that, unwilling to abandon their supply of whisky, the soldiers filled their canteens with it before the march. Since no other accounts mention this, it’s unlikely that it’s true.

When Baylor finally caught up with Lynde at San Augustine Springs, Lynde surrendered his entire command without firing a shot. Twenty-six Union soldiers joined the Confederates, and sixteen chose military imprisonment, becoming prisoners of war. The rest, 410 men, were paroled out of the war. Baylor gave them enough rifles and food to travel through Indian country to Canby's headquarters at Santa Fe, where Lynde's command broke up. Many of the men were sent to New York and spent the war as harbor guards or performed other non-belligerent duties.

Lynde himself also journeyed east, to Washington where he was expected to explain his actions. Despite conflicting testimony, he was dismissed from the Army, a scapegoat for Union failure in the southwest during the early days of the war. Lynde spent the next five years fighting this decision, which was finally reversed. He was reinstated to his rank in September 1866.

It remains unclear why Lynde surrendered the fort and his command without putting up much of a fight. Perhaps Lynde really harbored sympathies with the Confederates, as some people suggested. Or it could be that Lynde was truly incompetent and indecisive. But perhaps Lynde just lacked the experience and training to make the decisions that his situation required. Whatever the reasons, the old soldier, who was within sight of honorable, pensioned retirement after a long and uneventful career saw his plans go up in smoke in the smoldering ruins of Fort Fillmore. Like the road to San Augustine Springs, his road to retirement was longer and harder than he had expected.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is an educator and author who lives in the mountains of central New Mexico. Her novel Valverde takes place at the time of Lynde’s abandonment of Fort Fillmore. If you would like to read more about the Battle of Mesilla, click here and here. For more about Lynde and his court marshal, go and here. If you would like to know more about Ms. Bohnhoff and her books, go to her website.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is an educator and author who lives in the mountains of central New Mexico. Her novel Valverde takes place at the time of Lynde’s abandonment of Fort Fillmore. If you would like to read more about the Battle of Mesilla, click here and here. For more about Lynde and his court marshal, go and here. If you would like to know more about Ms. Bohnhoff and her books, go to her website.

Published on October 05, 2020 06:17

July 27, 2020

Us vs. Them

A few years back, I was standing behind a table stacked with my books at an arts and crafts festival when something magical happened. A woman who was walking by stopped, put her finger on one of my books, and said that she wished she could meet the author. When I told her that was me, she came around the table, hugged me, and declared that my book was the best one she'd ever read. She told me that if everyone in the world read my book, there would be no more war.

A few years back, I was standing behind a table stacked with my books at an arts and crafts festival when something magical happened. A woman who was walking by stopped, put her finger on one of my books, and said that she wished she could meet the author. When I told her that was me, she came around the table, hugged me, and declared that my book was the best one she'd ever read. She told me that if everyone in the world read my book, there would be no more war. Let me tell you right now that this kind of thing doesn't happen very often to me. For everyone who likes one of my books, there's someone else who hated it. This particular title is the one that really polarizes people.

The big idea in Swan Song is how we determine who is US and how we exclude those who aren't. They either get it, or they don't. If they get it, they might love it. (They might not. It has its flaws.) If they don't get it, they'll probably hate it.

Us

vs.

Them

is an old problem. We determine who is

us

and who is

them

in a number of ways, religion, language, color of skin or hair or eye, nationality, regionality, sex: they all can serve to separate or unite us as we choose. Lately, at least in America, the biggest lines have been drawn between people of color and between political parties. It's gotten ugly.

Us

vs.

Them

is an old problem. We determine who is

us

and who is

them

in a number of ways, religion, language, color of skin or hair or eye, nationality, regionality, sex: they all can serve to separate or unite us as we choose. Lately, at least in America, the biggest lines have been drawn between people of color and between political parties. It's gotten ugly.But this ugliness is not new. I was teaching English as a Second Language back in 2011 when Osama bin Laden was killed. and the wave of patriotism that swept the nation also swept my school. Some of that wave was lovely. Other aspects were not. Some of my students received nasty anonymous notes in their lockers, telling them to go home. Some got spat on in the halls. The crazy thing is, not all of these students were even Arabic or Muslim. They just looked different, foreign and were therefore part of them and not included in us .

https://www.focusonthefamily.com/pro-... In the January 9, 2016 edition of The Wall Street Journal, columnist Robert M. Sapolsky reported on the results of a neuroimaging study of responses in our brains to faces of different races. The study, by Eva Telzer of the University of Illinois and written in the Journal of Neuroscience in 2013, uncovered a result they called "other-race effect, or ORE. When we see faces different than our own, within a tenth of a second our brain activates the amygdala, a brain region that produces fear and anxiety. When this happens there is less activation of the fusiform, a part of the brain that helps us recognize individuals, read their expressions, and make inferences about their internal state. Our brains are wired to see

them

as a group and

us

as individuals.

https://www.focusonthefamily.com/pro-... In the January 9, 2016 edition of The Wall Street Journal, columnist Robert M. Sapolsky reported on the results of a neuroimaging study of responses in our brains to faces of different races. The study, by Eva Telzer of the University of Illinois and written in the Journal of Neuroscience in 2013, uncovered a result they called "other-race effect, or ORE. When we see faces different than our own, within a tenth of a second our brain activates the amygdala, a brain region that produces fear and anxiety. When this happens there is less activation of the fusiform, a part of the brain that helps us recognize individuals, read their expressions, and make inferences about their internal state. Our brains are wired to see

them

as a group and

us

as individuals.The good news in this study was that children who saw lots of different faces very early in life did not have as big an ORE response. But by early, the study meant really early. If we want children to not grow up with racist tendencies, we must lay the building blocks long before they learn about King's I Have a Dream speech in kindergarten or even learn the word equality.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a writer and retired teacher who lives in the mountains of central New Mexico. She has written a number of books, most of which are suitable for readers from the middle grades on up. She recommends Swan Song to an older audience of 16 and up. You can read more about Swan Song here.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a writer and retired teacher who lives in the mountains of central New Mexico. She has written a number of books, most of which are suitable for readers from the middle grades on up. She recommends Swan Song to an older audience of 16 and up. You can read more about Swan Song here.

Published on July 27, 2020 00:00

June 24, 2020

Visiting the WWI Battlefields of Belgium

In 2019 my husband and I were lucky to join a guided tour of World War I Battlefields. The war may have ended over a hundred years ago, but the landscape is still scarred by it, and by the war that followed. These pictures were taken near an area known as Hill 60. If you've ever wondered, the numbers designate meters above sea level. There are four hill 60s, but are in different sectors, so it wasn't confusing to planners during the war.

The hill 60 in the Ypres area was subject to a lot of mining, much of it done by Australians. Hundreds of tons of explosives were planted under German emplacements. Much of it (but not all of it) was detonated. When farmers returned to their land after the war, they rebuilt. Some of them didn't know they were rebuilding 90 feet above 20 thousand pounds of unexploded materials. One cache went off in a 1950s thunderstorm, the theory being that plowing had exposed the wires to a lightning strike.

Our guide for the day was Ian, a retired soldier from Northern Ireland who has written books on WWI. He led us past old German bunkers, showed us bomb craters 85 feet across, and answered (quite patiently) my thousand questions.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a writer who lives in the mountains of central New Mexico. She is currently working on an historical novel set in New Mexico and France during the time of the Pancho Villa Raid and World War I. You can learn more about her books by signing up for her newsletter here, or visiting her website here.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a writer who lives in the mountains of central New Mexico. She is currently working on an historical novel set in New Mexico and France during the time of the Pancho Villa Raid and World War I. You can learn more about her books by signing up for her newsletter here, or visiting her website here.

The hill 60 in the Ypres area was subject to a lot of mining, much of it done by Australians. Hundreds of tons of explosives were planted under German emplacements. Much of it (but not all of it) was detonated. When farmers returned to their land after the war, they rebuilt. Some of them didn't know they were rebuilding 90 feet above 20 thousand pounds of unexploded materials. One cache went off in a 1950s thunderstorm, the theory being that plowing had exposed the wires to a lightning strike.

Our guide for the day was Ian, a retired soldier from Northern Ireland who has written books on WWI. He led us past old German bunkers, showed us bomb craters 85 feet across, and answered (quite patiently) my thousand questions.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a writer who lives in the mountains of central New Mexico. She is currently working on an historical novel set in New Mexico and France during the time of the Pancho Villa Raid and World War I. You can learn more about her books by signing up for her newsletter here, or visiting her website here.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a writer who lives in the mountains of central New Mexico. She is currently working on an historical novel set in New Mexico and France during the time of the Pancho Villa Raid and World War I. You can learn more about her books by signing up for her newsletter here, or visiting her website here.

Published on June 24, 2020 07:09

June 1, 2020

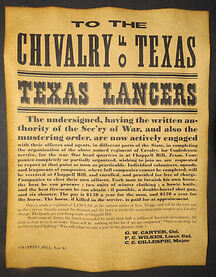

The Only Lancer Charge in the Civil War

When Major General H. H. Sibley invaded New Mexico in 1862, he brought with him two companies of lancers.

When Major General H. H. Sibley invaded New Mexico in 1862, he brought with him two companies of lancers.Handsome and chivalrous heirs of medieval knights, the lancers were the darlings of the parade through San Antonio on the day the Army of New Mexico headed west. Bright red flags with white stars snapped from their lances. Lances had been common on Napoleonic battlefields, and were used by Mexican cavalry during the conflicts against the Texans in the 1830s and 1840s. The lances that these two companies carried were war trophies captured from the Mexicans during the Mexican American War thirteen years earlier

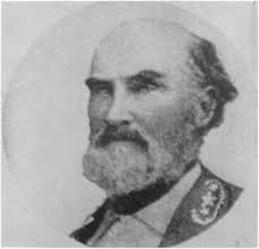

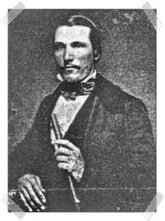

Colonel Thomas Green On the day of the Battle for Valverde Ford, Colonel Thomas Green peered across the battlefield and saw uniforms that he couldn't identify. Knowing they weren't Union regulars, he guessed that these men on the Union extreme right were a company of inexperienced New Mexico Volunteers who would break and run from a lancer charge.

Colonel Thomas Green On the day of the Battle for Valverde Ford, Colonel Thomas Green peered across the battlefield and saw uniforms that he couldn't identify. Knowing they weren't Union regulars, he guessed that these men on the Union extreme right were a company of inexperienced New Mexico Volunteers who would break and run from a lancer charge. He turned to the commanders of his two lancer companies, Captains Willis Lang and Jerome McCown, and asked which would like to have the honor of the first charge.

Captain Willis Lafayette Lang The first hand up belonged to the leader of the 5th Texas Cavalry Regiment's Company B. Captain Willis L. Lang was a rich, 31 year old who owned slaves that worked his plantation near Marlin in Falls County, Texas.

Captain Willis Lafayette Lang The first hand up belonged to the leader of the 5th Texas Cavalry Regiment's Company B. Captain Willis L. Lang was a rich, 31 year old who owned slaves that worked his plantation near Marlin in Falls County, Texas. Lang quickly organized his men. Minutes later, he gave the signal and his company cantered forward, lowered their lances, and began galloping across the 300 yards that divided his men from the men in the unusual uniforms. The plan called for McCown's company to follow after the Union troops had broken, and the two lancer companies would chase the panicking Union men into the Rio Grande that stood at their back.

Captain Theodore Dodd But Colonel Green was wrong. The men in the strange uniforms were not New Mexican Volunteers. They were Captain Theodore Dodd’s Independent Company of Colorado Volunteers. Dodd's men were a scrappy collection of miners and cowboys who were reputedly low on discipline but high on fighting spirit. They coolly waited until the lancers were within easy range, then fired a volley that unhorsed many of the riders. Their second volley finished the assault. More than half of Lang's men were either killed or wounded, and most of the horses lay dead on the field. Lang himself dragged himself back to the Confederate lines because he was too injured to walk. Lang's charge was the only lancer charge of the American Civil War. The destruction of his company showed that modern firearms had rendered the ten-foot long weapons obsolete. McCown's men, and what remained of Lang's men threw their lances into a heap and burned them. They then rearmed themselves with pistols and shotguns and returned to the fight. The day after the battle, Lang and the rest of the injured Confederate were carried north to the town of Socorro, where they had requisitioned a house and turned it into a hospital. A few days later, depressed and in great pain, he asked his colored servant for his revolver, with which he ended his suffering. Lang and the other Confederate dead were buried in a plot of land near the south end of town that has now become neglected and trash-strewn. The owners do not allow visitors.

Captain Theodore Dodd But Colonel Green was wrong. The men in the strange uniforms were not New Mexican Volunteers. They were Captain Theodore Dodd’s Independent Company of Colorado Volunteers. Dodd's men were a scrappy collection of miners and cowboys who were reputedly low on discipline but high on fighting spirit. They coolly waited until the lancers were within easy range, then fired a volley that unhorsed many of the riders. Their second volley finished the assault. More than half of Lang's men were either killed or wounded, and most of the horses lay dead on the field. Lang himself dragged himself back to the Confederate lines because he was too injured to walk. Lang's charge was the only lancer charge of the American Civil War. The destruction of his company showed that modern firearms had rendered the ten-foot long weapons obsolete. McCown's men, and what remained of Lang's men threw their lances into a heap and burned them. They then rearmed themselves with pistols and shotguns and returned to the fight. The day after the battle, Lang and the rest of the injured Confederate were carried north to the town of Socorro, where they had requisitioned a house and turned it into a hospital. A few days later, depressed and in great pain, he asked his colored servant for his revolver, with which he ended his suffering. Lang and the other Confederate dead were buried in a plot of land near the south end of town that has now become neglected and trash-strewn. The owners do not allow visitors.  This derelict field was once a Confederate Cemetery.

This derelict field was once a Confederate Cemetery.

The Charge of Company B of the 5th Texas Cavalry Regiment at the Battle of Valverde Ford is included in Jennifer Bohnhoff's historical novel, Valverde. The author is a former New Mexico history teacher who lives in the mountains of central New Mexico. You can read more about her and her writing here.

The Charge of Company B of the 5th Texas Cavalry Regiment at the Battle of Valverde Ford is included in Jennifer Bohnhoff's historical novel, Valverde. The author is a former New Mexico history teacher who lives in the mountains of central New Mexico. You can read more about her and her writing here.

Published on June 01, 2020 00:00