Isaac Lynde: The Wrong Man for the Job

If there was ever a man who suffered by being placed in the wrong place at the wrong time, it was Isaac Lynde.

If there was ever a man who suffered by being placed in the wrong place at the wrong time, it was Isaac Lynde.Lynde was born July 27, 1804, in Williamstown, Vermont. He must have been a promising lad, for in 1822 he secured an appointment to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. The Academy’s records describe him as "an intelligent, sprightly lad," handsome, and well educated,” and he graduated four years later, thirty-second in a class of thirty-eight.

Lynde’s early career was typical for the time. He served in a number of frontier posts in the Northwest and the far plains, and took part in the Mexican-American War. Unlike many of his time, though Lynde’s record includes no battles or distinction of any kind, and in thirty-four years of service he had risen only three full grades, to Major. All of his promotions were routine, and based on time of service, his appointments to posts that were out of the way and relatively underutilized. Why this was the case cannot be said with any certainty. Perhaps he was not as promising as his youth had indicated, or perhaps his problem was that he was an infantry man in an Army that was giving all its plum assignments to the cavalry. At any case, by the time the Civil War was brewing, Lynde was at the end of his career and looking forward to retiring on a pension and settling into obscurity.

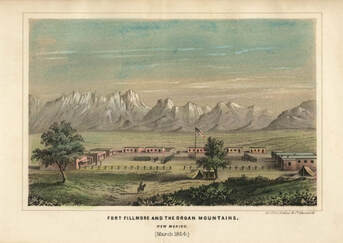

Circumstances, however, were not going to allow Lynde to retire quietly. In June 1861, the Union Army in New Mexico Territory faced a huge dilemma. Many officers and soldiers, including William Loring, the Commander of the Department of New Mexico, had resigned their posts and joined the Confederate Army. This left such a serious shortage of troops that E.R.S. Canby, Loring’s replacement, was forced to close forts created primarily to protect settlers from Indian attack and concentrate men in those forts most likely to lie along the path an invading Confederate army might take. Canby ordered Major Isaac Lynde then in command of the 7th Infantry, to abandon Fort McLane, south of Silver City, and take command of Fort Fillmore, six miles from the town of Mesilla. Canby warned Lynde that his new post was endangered not only by a possible invasion from Texas, but because the civilian population of Mesilla Valley sympathized strongly with the Southern cause. It was a crucial post to hold because it controlled the stage road on which U.S. troops would use to withdraw from Arizona. It was also the last Union holding that officers leaving New Mexico to join the Confederacy passed through, and the first objective for a Confederate advance into New Mexico. Lynde was given full responsibility for the area, including the right to decide whether to attack or ignore El Paso’s Fort Bliss, forty miles to the south and in secessionist hands.

When Major Lynde arrived at his new post in the first week of July, he found it woefully inadequate. Lynde noted that Fort Fillmore was located in a basin surrounded by sand hills, so that artillery could fire down into it. The hills were covered by dense growth that would allow a thousand men to approach undetected to within 500 yards. Next to the fort, a sweep of level land was ideal for attacking cavalry. Furthermore, the fort had no walls or ramparts. Shaped like a U, its open end faced the river and the road from El Paso. Because water had to be carried up from the river, a mile and a half to west, the fort could not stand a siege. He wrote to Canby that he thought the fort was poorly situated for defense, and it was not worth the exertion it would take to hold it.

When Major Lynde arrived at his new post in the first week of July, he found it woefully inadequate. Lynde noted that Fort Fillmore was located in a basin surrounded by sand hills, so that artillery could fire down into it. The hills were covered by dense growth that would allow a thousand men to approach undetected to within 500 yards. Next to the fort, a sweep of level land was ideal for attacking cavalry. Furthermore, the fort had no walls or ramparts. Shaped like a U, its open end faced the river and the road from El Paso. Because water had to be carried up from the river, a mile and a half to west, the fort could not stand a siege. He wrote to Canby that he thought the fort was poorly situated for defense, and it was not worth the exertion it would take to hold it. On July 25, Lynde was forced into action when Confederate Lieutenant Colonel John Baylor brought his 2nd Texas Mounted Rifles to Mesilla. Lynde left one company of infantry and the band to hold the fort. He crossed the Rio Grande with a force of three hundred and eighty men and four howitzers. He lined his men up in a cornfield, then sent his aide forward with a white flag to demand that the Confederates surrender. The Confederates replied that if Lynde wanted Mesilla, he was to come and get it. Lynde then fired his howitzers, whose shells burst short in the air. The Mayor of Mesilla came out and reminded Lynde that killing the women and children who sheltered in the town would look very bad and would not win Lynde any allies among the people. After a few exchanges of musket fire, and a small number of casualties on both sides, Lynde withdrew to the fort as evening fell.

On July 25, Lynde was forced into action when Confederate Lieutenant Colonel John Baylor brought his 2nd Texas Mounted Rifles to Mesilla. Lynde left one company of infantry and the band to hold the fort. He crossed the Rio Grande with a force of three hundred and eighty men and four howitzers. He lined his men up in a cornfield, then sent his aide forward with a white flag to demand that the Confederates surrender. The Confederates replied that if Lynde wanted Mesilla, he was to come and get it. Lynde then fired his howitzers, whose shells burst short in the air. The Mayor of Mesilla came out and reminded Lynde that killing the women and children who sheltered in the town would look very bad and would not win Lynde any allies among the people. After a few exchanges of musket fire, and a small number of casualties on both sides, Lynde withdrew to the fort as evening fell. That night, Lynde decided that the only hope of saving his troops from capture was in abandoning the fort and reaching another military post. He ordered the evacuation, set the fort on fire to stop it and its supplies from falling into enemy hands, and at one in the morning began the march up and over the Organ Mountains to Fort Stanton. Lynde had never taken this road, but he believed that San Augustine was only twenty miles away, just over a pass in the mountains. The march went well until the sun rose on a hot July day. Then the distance proved to be much longer and the water much scarcer than Lynde had believed. As Baylor’s men followed along, they found the road lined with guns, cartridge boxes, and men who were almost dying from fatigue and thirst. The memoirs of Hank Smith, a private soldier on the Confederate side, suggest that many of the men were drunk, and suggests that, unwilling to abandon their supply of whisky, the soldiers filled their canteens with it before the march. Since no other accounts mention this, it’s unlikely that it’s true.

When Baylor finally caught up with Lynde at San Augustine Springs, Lynde surrendered his entire command without firing a shot. Twenty-six Union soldiers joined the Confederates, and sixteen chose military imprisonment, becoming prisoners of war. The rest, 410 men, were paroled out of the war. Baylor gave them enough rifles and food to travel through Indian country to Canby's headquarters at Santa Fe, where Lynde's command broke up. Many of the men were sent to New York and spent the war as harbor guards or performed other non-belligerent duties.

Lynde himself also journeyed east, to Washington where he was expected to explain his actions. Despite conflicting testimony, he was dismissed from the Army, a scapegoat for Union failure in the southwest during the early days of the war. Lynde spent the next five years fighting this decision, which was finally reversed. He was reinstated to his rank in September 1866.

It remains unclear why Lynde surrendered the fort and his command without putting up much of a fight. Perhaps Lynde really harbored sympathies with the Confederates, as some people suggested. Or it could be that Lynde was truly incompetent and indecisive. But perhaps Lynde just lacked the experience and training to make the decisions that his situation required. Whatever the reasons, the old soldier, who was within sight of honorable, pensioned retirement after a long and uneventful career saw his plans go up in smoke in the smoldering ruins of Fort Fillmore. Like the road to San Augustine Springs, his road to retirement was longer and harder than he had expected.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is an educator and author who lives in the mountains of central New Mexico. Her novel Valverde takes place at the time of Lynde’s abandonment of Fort Fillmore. If you would like to read more about the Battle of Mesilla, click here and here. For more about Lynde and his court marshal, go and here. If you would like to know more about Ms. Bohnhoff and her books, go to her website.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is an educator and author who lives in the mountains of central New Mexico. Her novel Valverde takes place at the time of Lynde’s abandonment of Fort Fillmore. If you would like to read more about the Battle of Mesilla, click here and here. For more about Lynde and his court marshal, go and here. If you would like to know more about Ms. Bohnhoff and her books, go to her website.

Published on October 05, 2020 06:17

No comments have been added yet.