Jennifer Bohnhoff's Blog, page 30

February 10, 2020

A Confederate Point of View

When historians want to know what it was like to be part of the Confederate invasion of New Mexico, one of the people they turn to is Alfred Brown Peticolas.

When historians want to know what it was like to be part of the Confederate invasion of New Mexico, one of the people they turn to is Alfred Brown Peticolas.Peticolas was was born on May 27, 1838, in Richmond, Virginia.. In 1859, he came west to Victoria, Texas, where he set up a law partnership with Samuel White.

On September 11, 1861, he joined the Confederate Army. Peticolas enlisted in Company C of the Fourth Regiment of Texas Mounted Volunteers,. This was part of Henry Hopkins Sibley's Army of New Mexico, a brigade with which Sibley intended to capture the rich Colorado gold fields, then secure the gold and harbors of California for the Confederacy. Throughout his time in New Mexico, Peticolas kept a diary in which he set down his keen observations about the country through which he traveled. He was also an artist and sketched his surroundings. The diary filled several books, the first of which was destroyed when the wagon in which is was stored was burned.

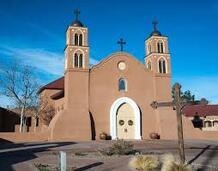

Peticolas sketched the San Miguel mission church in Socorro, New Mexico. After the Civil War, Bishop Lamy remodeled this adobe church.. .

Peticolas sketched the San Miguel mission church in Socorro, New Mexico. After the Civil War, Bishop Lamy remodeled this adobe church.. .

He also drew San Felipe church, in Albuquerque's Old Town. In his sketch, the Confederate flag flies from a flag pole in the center square of the village, right in front of the church.

He also drew San Felipe church, in Albuquerque's Old Town. In his sketch, the Confederate flag flies from a flag pole in the center square of the village, right in front of the church. The Confederate, Mexican, Spanish, and American flags, flew over Albuquerque's Old Town representing all the governments that had controlled the town. In 2015, deemed too controversial, the stars and bars were taken down.

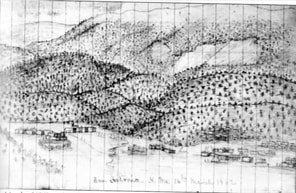

Departing Albuquerque, Peticolas' unit traveled through Tijeras Canyon, then turned north, taking the road now known as N14 towards Santa Fe. They camped for over a week in the mountain village of San Antonio. The church, the building at the far left of the picture, burned down and was rebuilt in 1957. The Confederate tents and wagons are on the far right of the picture. After Sibley's retreat back to San Antonio Texas, Peticolas participated in the Louisiana Campaign. Finally, illness led to his reassignment as a clerk at the quartermaster headquarters, and he finished the war behind a desk.

Departing Albuquerque, Peticolas' unit traveled through Tijeras Canyon, then turned north, taking the road now known as N14 towards Santa Fe. They camped for over a week in the mountain village of San Antonio. The church, the building at the far left of the picture, burned down and was rebuilt in 1957. The Confederate tents and wagons are on the far right of the picture. After Sibley's retreat back to San Antonio Texas, Peticolas participated in the Louisiana Campaign. Finally, illness led to his reassignment as a clerk at the quartermaster headquarters, and he finished the war behind a desk.

Rebels on the Rio Grande: the Civil War Journal of A.B. Peticolas, edited by Don E. Alberts, University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, New Mexico, 1984 is a compilation of the passages from the diary that related to New Mexico.

Rebels on the Rio Grande: the Civil War Journal of A.B. Peticolas, edited by Don E. Alberts, University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, New Mexico, 1984 is a compilation of the passages from the diary that related to New Mexico. While he is not represented in Jennifer Bohnhoff's trilogy of novels about the Civil War, his material was instrumental in shaping the narrative and illuminating it with the little details that make historical fiction feel accurate.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is an author and educator who lives very close to the mountain town that Peticolas sketched. Valverde, the first novel in her triology Rebels Along the Rio Grande, came out in 2017. The second, Glorieta, will be published in the spring of 2020, and Peralta will follow.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is an author and educator who lives very close to the mountain town that Peticolas sketched. Valverde, the first novel in her triology Rebels Along the Rio Grande, came out in 2017. The second, Glorieta, will be published in the spring of 2020, and Peralta will follow.

Published on February 10, 2020 00:00

February 3, 2020

Fake Money to Raise Real Troops

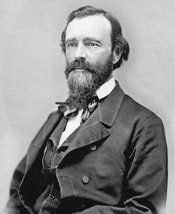

William Gilpin believed in the west. A native of Pennsylvania, Gilpin was born in 1813. He attended school in England for two years, then went to the University of Pennsylvania, finally graduating in really 1836 from the United States Military Academy at West Point

William Gilpin believed in the west. A native of Pennsylvania, Gilpin was born in 1813. He attended school in England for two years, then went to the University of Pennsylvania, finally graduating in really 1836 from the United States Military Academy at West PointIn 1843, Gilpin joined Kit Carson and several other notable westerners on John Charles Fremont's expedition to map the route over the Continental Divide as far as Oregon. A few years later, Major Gilpin marched his regiment to Chihuahua City during the Mexican-American War. He did well enough there that Gilpin received command of a volunteer force organized to suppress Indian uprisings in the West and to protect the Santa Fe Trail. After this, Gilpin settled in Independence, Missouri, where he set up a law practice and gave lectures on the health and wealth that was available in the Rocky Mountains.

In February of 1861, Colorado was organized as a territory of the United States, and President Lincoln appointed Colonel Gilpin to be its Governor. Upon arriving in the Territory, Gilpin realized that one of the most important tasks he had was to defend against a Confederate invasion. Almost all of Colorado's regular Army troops had been called east when the Civil War began, leaving the rich gold fields of the Rockies vulnerable. Not realizing that Confederate General Henry Sibley wasraising an invasion force in Texas, Washington refused to support Gilpin's request for the organization of Union forces in Colorado Territory.

In February of 1861, Colorado was organized as a territory of the United States, and President Lincoln appointed Colonel Gilpin to be its Governor. Upon arriving in the Territory, Gilpin realized that one of the most important tasks he had was to defend against a Confederate invasion. Almost all of Colorado's regular Army troops had been called east when the Civil War began, leaving the rich gold fields of the Rockies vulnerable. Not realizing that Confederate General Henry Sibley wasraising an invasion force in Texas, Washington refused to support Gilpin's request for the organization of Union forces in Colorado Territory.

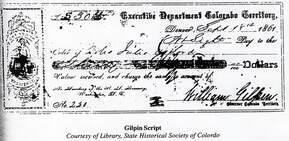

Gilpin then took it upon himself to protect the territory. He organized the First Colorado Regiment of Volunteers and paid for it by issuing $375,000 in negotiable drafts that were payable from the national treasury. The drafts became known as Gilpin Scrip, and the Colorado First Volunteers, a force of 1,342 men the scrip helped arm and house, became known as Gilpin's Pet Lambs.

Gilpin then took it upon himself to protect the territory. He organized the First Colorado Regiment of Volunteers and paid for it by issuing $375,000 in negotiable drafts that were payable from the national treasury. The drafts became known as Gilpin Scrip, and the Colorado First Volunteers, a force of 1,342 men the scrip helped arm and house, became known as Gilpin's Pet Lambs.At first, the merchants of Denver were all too happy to exchange their goods for Gilpin Scrip. However, Washington considered the scrip illegal and the U.S. Treasury refused to redeem them. Despite traveling to Washington to plead his case, the cabinet removed Gilpin from office by a unanimous vote. Ironically, Gilpin achieved his purpose. His illegally funded First Regiment distinguished itself, participating at the Battle of Valverde outside Fort Craig, and routing Confederate General Henry Sibley's Army at Glorieta Pass.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a writer and educator in central New Mexico. Her next book Glorieta, tells the story of this Civil War battle and is written for midgrade readers. It will be published this spring. If you would like to know when it is published, join her email list here.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a writer and educator in central New Mexico. Her next book Glorieta, tells the story of this Civil War battle and is written for midgrade readers. It will be published this spring. If you would like to know when it is published, join her email list here. One very entertaining book on Gilpin is Colorado: A History, by Marshall Sprague (1984).

Published on February 03, 2020 00:00

January 27, 2020

Glorieta: Battle of Three Ranches Ranch One: Kozlowski's Ranch

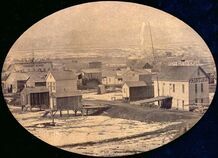

The decisive battle of the New Mexico Campaign of the Civil War took place on March 26-28, 1862. Called the Battle of Glorieta, it ranged through a narrow mountain just east of Santa Fe. Three ranches owned by three very different characters were settings for this battle.  Martin Kozlowski in front of his trading post. The Pecos River meets Glorieta Stream in a wide, flat area at the far east of the valley. It was here that Martin ( who in some records is called Napoleon) Kozlowski established his ranch.

Martin Kozlowski in front of his trading post. The Pecos River meets Glorieta Stream in a wide, flat area at the far east of the valley. It was here that Martin ( who in some records is called Napoleon) Kozlowski established his ranch.

Kozlowski wasn't the first person attracted to this area. The Santa Fe Trail passed through this area, providing opportunities for those who wanted to provide food and lodging for travelers. Some of the earliest surviving buildings on the site date from the 1810s, and thus predate the trail. But even earlier, the Pecos Pueblo had been established around AD 1100. The Pueblos was inhabited until 1838, when Comanche incursions made the remaining inhabitants relocate to the Walatowa Pueblo in Jemez. Kozlowski used some of the timbers and bricks from the pueblo to build his buildings.

Martin Kozlowski came to the area by a circuitous route. He was born in Warsaw, Poland in 1827 and fought in the 1848 revolution against the Prussians. He was a refugee for two years in England, during which time he met and married an Irish woman named Ellene. The two immigrated to American in 1853, and Martin enlisted in the First Dragoons, who were fighting Apaches in the Southwest.

Martin must have fallen in love with New Mexico during his Army years. In 1858 he mustered out and used his 160-acre government bounty land warrant to purchase the land on which he built his ranch. His 600 acre spread included 50 improved acres, which included a home for the family, a trading post, a tavern, and rooms for travelers. It had a spring for fresh water, and lots of forage for horses and mules. The 1860 agriculture census shows that Kozlowski grew corn and raised livestock, but a lot of his livelihood came from accommodating for travelers on the Santa Fe trail.

Kozlowski's ranch became the headquarters for the Union Army during the Battle of Glorieta. The forces were comprised mostly of men from the Colorado Volunteers who had come down through Raton Pass and were planning to engage the Confederates in Santa Fe. Their journey from Camp Wells in Denver seemed to be one long foraging expedition; many of the towns and ranches they passed complained to the government that they had lost provisions and animals to the Army. By the time they reached Kozlowski's ranch and established Camp Lewis, they seemed to have learned their lesson. After the war, Kozlowski complimented them, saying “When they camped on my place, they never robbed me of anything, not even a chicken.” Perhaps their good behavior was because Kozlowski was former military himself.

After the Battle, the Union Army maintained a hospital in Kozlowski's tavern for another two months.

The early 1870s appear to be the high point for the Kozlowski family's enterprises. In 1873, U.S. Attorney T.B. Catron sued him for violating a federal law that prevented non-Indians from settling on pueblo land grants. The case went all the way to the Supreme Court, but ultimately Martin paid $1,000 and was able to keep his land. In 1880 the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad ran its line through the canyon, effectively ending the lucrative Santa Fe Trail traffic. Soon thereafter Kozlowski moved to Albuquerque, where he died in 1905. After that, the ranch traded hands several times, alternating from working ranch to dude ranch. In 1939 it was bought by a Texas oilman and rancher named Buddy Fogelson, who married the actress Greer Garson. The ranch was donated to the National Park Service in 1991, and is now part of Pecos National Park.

Martin Kozlowski in front of his trading post. The Pecos River meets Glorieta Stream in a wide, flat area at the far east of the valley. It was here that Martin ( who in some records is called Napoleon) Kozlowski established his ranch.

Martin Kozlowski in front of his trading post. The Pecos River meets Glorieta Stream in a wide, flat area at the far east of the valley. It was here that Martin ( who in some records is called Napoleon) Kozlowski established his ranch.Kozlowski wasn't the first person attracted to this area. The Santa Fe Trail passed through this area, providing opportunities for those who wanted to provide food and lodging for travelers. Some of the earliest surviving buildings on the site date from the 1810s, and thus predate the trail. But even earlier, the Pecos Pueblo had been established around AD 1100. The Pueblos was inhabited until 1838, when Comanche incursions made the remaining inhabitants relocate to the Walatowa Pueblo in Jemez. Kozlowski used some of the timbers and bricks from the pueblo to build his buildings.

Martin Kozlowski came to the area by a circuitous route. He was born in Warsaw, Poland in 1827 and fought in the 1848 revolution against the Prussians. He was a refugee for two years in England, during which time he met and married an Irish woman named Ellene. The two immigrated to American in 1853, and Martin enlisted in the First Dragoons, who were fighting Apaches in the Southwest.

Martin must have fallen in love with New Mexico during his Army years. In 1858 he mustered out and used his 160-acre government bounty land warrant to purchase the land on which he built his ranch. His 600 acre spread included 50 improved acres, which included a home for the family, a trading post, a tavern, and rooms for travelers. It had a spring for fresh water, and lots of forage for horses and mules. The 1860 agriculture census shows that Kozlowski grew corn and raised livestock, but a lot of his livelihood came from accommodating for travelers on the Santa Fe trail.

Kozlowski's ranch became the headquarters for the Union Army during the Battle of Glorieta. The forces were comprised mostly of men from the Colorado Volunteers who had come down through Raton Pass and were planning to engage the Confederates in Santa Fe. Their journey from Camp Wells in Denver seemed to be one long foraging expedition; many of the towns and ranches they passed complained to the government that they had lost provisions and animals to the Army. By the time they reached Kozlowski's ranch and established Camp Lewis, they seemed to have learned their lesson. After the war, Kozlowski complimented them, saying “When they camped on my place, they never robbed me of anything, not even a chicken.” Perhaps their good behavior was because Kozlowski was former military himself.

After the Battle, the Union Army maintained a hospital in Kozlowski's tavern for another two months.

The early 1870s appear to be the high point for the Kozlowski family's enterprises. In 1873, U.S. Attorney T.B. Catron sued him for violating a federal law that prevented non-Indians from settling on pueblo land grants. The case went all the way to the Supreme Court, but ultimately Martin paid $1,000 and was able to keep his land. In 1880 the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad ran its line through the canyon, effectively ending the lucrative Santa Fe Trail traffic. Soon thereafter Kozlowski moved to Albuquerque, where he died in 1905. After that, the ranch traded hands several times, alternating from working ranch to dude ranch. In 1939 it was bought by a Texas oilman and rancher named Buddy Fogelson, who married the actress Greer Garson. The ranch was donated to the National Park Service in 1991, and is now part of Pecos National Park.

Published on January 27, 2020 00:00

January 21, 2020

Samuel M. Logan: Man of Action

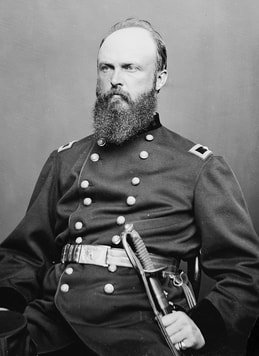

Samuel M. Logan isn’t a name that many would recognize as a Civil War personality, but he played an important supporting role in the Colorado Volunteers and has a small role in my novel Glorieta, the second of three books in Rebels Along the Rio Grande.

Samuel M. Logan isn’t a name that many would recognize as a Civil War personality, but he played an important supporting role in the Colorado Volunteers and has a small role in my novel Glorieta, the second of three books in Rebels Along the Rio Grande.Samuel M. Logan was a Mexican American War veteran who was working as a blacksmith in Denver when the Civil War broke out. He didn’t waste any time in showing on which side his sympathies lay with a grand gesture.

On April 24, 1861, just days after the bombardment of Fort Sumter, the southern sympathizers who owned Wallingford and Murphey’s Mercantile on Larimer Street in downtown Denver raised the Confederate stars and bars on the pole atop their building. The flag attracted an angry mob of pro-Union sympathizers who threw rocks at the store and demanded that the flag come down.

This is when Logan swang – literally - into action. He climbed a hitching rail and swung himself onto the roof of the store. Accounts of what happened next contradict each other. Some accounts say that the Marshal showed up at this point, dispersed the crowd, and allowed Wallingford and Murphey to continue flying the Confederate colors. Other accounts say that Logan pulled down the flag and ripped it to shreds as the crowd cheered him on.

Whichever is the case, Logan’s stunt made him popular enough that he was able to recruit a company of men to follow him into the volunteer army that William Gilpin, the newly appointed governor of the territory, was raising. In those days, whoever brought in the required number of men was given the commission to lead them. Samuel M. Logan, blacksmith and climber of roofs became Captain Samuel M. Logan of Company B of the Colorado Volunteers.

Logan’s reputation for quick and dramatic action led him to receive some orders that made for exciting press releases. In late August, his Company was ordered to clean out the Criterion, a saloon that was a notorious gathering place for secessionists. Logan and his men stormed in with bayonets fixed. They confiscated a large pile of weapons and ammunition and became the darling heroes of Denver.

However, the same qualities that made him a man of action didn’t make him a beloved leader. By September, Company B had delivered a petition to Governor Gilpin requesting that he remove Captain Logan, “whose overbearance and tyranny have become untolerable.” The Governor chose to ignore this petition.

Logan’s Company engaged the enemy on both days of the Battle of Glorieta. On the second day, it was part of the group that Major John Chivington led over the top of Glorieta Mesa in what was intended to be a flanking movement to attack the Confederate force in the rear. Instead, they overshot and instead of fighting in the Battle of Pigeon’s Ranch, descended from the mesa at Johnson’s Ranch, where they were able to destroy the Confederate baggage train, effectively destroying the Confederate Army’s ability to wage war in New Mexico.

From then on, Logan’s rise through the military was tied to that of John Chivington’s because the two were men of fiery and decisive action who held a “take no quarter” attitude, especially when it came to treatment of American Natives. By spring of 1864, Logan had been promoted to Lieutenant Colonel, bypassing other officers who argued for more leniency in dealings with the Plains Tribes. With Chivington, Logan participated in the infamous Sand Creek Massacre in November 1864.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a writer and educator who lives in New Mexico. Her second book in Rebels Along the Rio Grande, a trilogy of novels about the Civil War in New Mexico, will come out this spring.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a writer and educator who lives in New Mexico. Her second book in Rebels Along the Rio Grande, a trilogy of novels about the Civil War in New Mexico, will come out this spring.

Published on January 21, 2020 00:00

January 13, 2020

Cian's Scones

A replica of the Stone of Scone outside Scone Palace. A recent cold, foggy morning inspired me to dig through my recipe box for the yellowed and tattered newspaper clipping that has a recipe for Traditional Irish Scones. I have no idea how long I've had this clipping, but if I had to guess, it's 20 years old.

A replica of the Stone of Scone outside Scone Palace. A recent cold, foggy morning inspired me to dig through my recipe box for the yellowed and tattered newspaper clipping that has a recipe for Traditional Irish Scones. I have no idea how long I've had this clipping, but if I had to guess, it's 20 years old. Scones themselves are much older. They probably originated in Scotland in the earth 16th century. The first scones were most likely made with oats and baked on a griddle (or, as the Scots say, a girdle.)

How they acquired their name has been lost in the fog of time. Some have suggested that their name it comes from the Dutch word ‘schoonbrot’, which means beautiful bread. Others believe the name is related to The Stone of Scone, also known as the Stone of Destiny,. This is a rock that Kings of Scotland were seated on when they were crowned, and it has an interesting history of its own. Perhaps both the food and the rock were both named after the town of Scone, which is close to Perth.

Anna, the Duchess of Bedford (1788 – 1861) is credited with making scones a part of the English tradition of Afternoon Tea when she ordered the servants to bring tea and some sweet breads one afternoon. The treats included scones, and they became popular throughout the United Kingdom and, eventually, the world.

The tattered and yellow clipping calls this variation Traditional Irish Scones. I have no idea how authentic the recipe is, but when I pulled it out, it occurred to me that the main character in my next novel is Irish. Would Cian's mam, I wondered, have made something similar to these for his breakfast? Cian learned to cook from his Mam, and this skill helped ingratiate himself to his fellow prospectors in Colorado's gold mining frenzy and his fellow soldiers in the Union Army. If Cian cooked scones in either place, it likely would have been in a dry, floured pan over a medium-low heat, turning once to brown both sides. You can try it this way, too!

If you don't have buttermilk iyou can make an acceptable substitute by adding 3 TBS of Vinegar to 3/4 cup of milk and waiting for it to clabber, a fancy word for develop lumps.

Traditional Irish Scones

3 cups all purpose flour

3 TBS sugar

1 tsp baking soda

½ tsp salt

6 TBS chilled unsalted butter

1 egg, beaten to blend

¾ cup plus 3 TBS buttermilk

1/3 cup dried currants (raisins, dried cranberries or the little dried blueberries that Trader Joes sells can take the place of the currants.)

Preheat oven to 425

Mix flour, sugar, baking soda and salt in a large bowl.

Slice butter into pats and drop them all over the flour mixture. Use a fork, a pastry cutter, or your fingers to blend in the butter until the mixture resembles a fine meal.

Mix in fruit pieces.

Mix in egg and enough buttermilk to form a soft dough.

Turn the dough out onto a flour surface. Pat the dough into three ¾ thick rounds. Cut each round into quarters. Or you can use a round cookie cutter to cut out the scones.

Transfer scones to a lightly floured baking sheet. Brush tops with milk and sprinkle with sugar. Bake until scones are golden brown and cooked through, between 18-20 minutes.

Makes 1 dozen scones.

Published on January 13, 2020 00:00

January 7, 2020

John Potts Slough: Victor of Glorieta

John Potts Slough came from a prestigious military and political family. His ancestor, Mattias Slough, was the first colonel appointed by General George Washington during the Revolutionary War and was also a member of the Pennsylvania assembly before he left public life to run a tavern in Lancaster County.

John Potts Slough came from a prestigious military and political family. His ancestor, Mattias Slough, was the first colonel appointed by General George Washington during the Revolutionary War and was also a member of the Pennsylvania assembly before he left public life to run a tavern in Lancaster County. John had big shoes, and expectations, to fill.

John Potts Slough (whose name rhymes with 'plough') was born on February 1, 1829, in Cincinnati, Ohio. He earned a degree in law and was elected as a Democrat to the Ohio General Assembly. Things were looking promising for this young man, but all was not perfect. Potts was noted for having a fierce temper and could pepper his tirades with obscenities. He was expelled from the Legislature after engaging in a fist fight with another assemblyman. He then moved to Kansas where he was narrowly defeated in a race for the Governor's seat.

Slough then moved to Denver and became one of its preeminent lawyers. When the Civil War broke out, he entered the service as the Captain of the 1st Colorado "Pike's Peakers" Volunteer Regiment, then convinced the territory's Governor, William Gilpin, to raise his rank to Colonel. Slough used family money to support the troops. He located a vacant building, the Buffalo House Hotel, and got it donated for use as barracks until Camp Weld was built on the south side of Denver. Despite his organizational acumen, Slough was not popular with the troops, who found him cold and imperious. In 1862, a Confederate army invaded New Mexico Territory, and Slough marched his regiment to Fort Union. Once there, he took assumed control of the fort, arguing that he outranked Colonel Paul, the regular Army officer who had been in control, by reason of an earlier appointment date.

Colonel Edward Canby, who commanded the Department of New Mexico, ordered Slough to stay at the fort, but Slough deliberately misinterpreted the orders and marched to Glorieta Pass, where he engaged in a battle that ultimately turned the tide and sent the Confederate Army back to Texas. The victory was not a sweet one for Slough. Worried that he would be drummed out for disobeying orders and convinced that his own men fired on him during the battle, he resigned his commission and left the state.

Slough went to Washington, D.C., where once again things seemed to be going his way. He was appointed Brigadier General of Volunteers and became the military Governor of Alexandria, Virginia. Slough served as pallbearer at Lincoln's funeral and was a member of the court that convicted Henry Wirz, commander of the notorious Andersonville Prisoner of War Camp. In 1866, President Andrew Johnson appointed Slough the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of New Mexico.

Slough is buried in Spring Grove Cemetery, Cincinnati, Ohio. Once he returned to the territory, Slough again showed concern for his old troops. His efforts to have proper burials for the soldiers killed at Glorieta resulted in the creation of the National Cemetery in Santa Fe in 1867. In 1895, Confederates who died in the battle were interred there as well.

Slough is buried in Spring Grove Cemetery, Cincinnati, Ohio. Once he returned to the territory, Slough again showed concern for his old troops. His efforts to have proper burials for the soldiers killed at Glorieta resulted in the creation of the National Cemetery in Santa Fe in 1867. In 1895, Confederates who died in the battle were interred there as well.But once again, Slough's fiery temper and outspoken tirades got him into trouble. President Andrew Johnson wanted Slough to break down the corrupt patronage system that had plagued New Mexico for centuries, and Slough began by attacking peonage, which he compared to slavery. This swiftly earned him enemies in the still divided and notoriously violent territory. On December 17, 1867, Slough was playing billiards in the La Fonda Hotel when he and another former Union officer and New Mexico legislator, William Logan Ryerson, got in an argument. Two days later, Ryerson, who was also a part of the notoriously corrupt Santa Fe Ring, fatally shot an unarmed Slough in the lobby of Santa Fe's Exchange Hotel. Ryerson was tried for murder but the jury acquitted him, saying he had acted in self defense. Slough is one of the historical characters in Jennifer Bohnhoff's Civil War novel Glorieta, which will be published this spring. Glorieta is the second in the triology Rebels Along the Rio Grande. The first book in the series, Valverde, was published in 2017 and is available here.

Published on January 07, 2020 00:00

January 1, 2020

Fort Union: Guardian of the Santa Fe Trail

The ruins of the third Fort Union.

The ruins of the third Fort Union.  Fort Union rests out in the middle of nowhere, but a century and a half ago it was the center of a lot of activity. It has been rebuilt three times, each time responding to what was happening around it.

Fort Union rests out in the middle of nowhere, but a century and a half ago it was the center of a lot of activity. It has been rebuilt three times, each time responding to what was happening around it. Located near the convergence of the Mountain and Cimmaron branches, Fort Union's original task was to monitor the Santa Fe trail. The soldiers were charged with controlling Native Americans and, if wagon trains came under attack, to respond with campaigns against the Indians.

The original fort, constructed in the 1850s, was built close by the eastern edge of a high mesa in order to protect it from the incessant winds. Diaries from the period indicate that the protection was minimal, and that sand constantly seeped through cracks around windows and found its way into beds and food supplies. It was thrown up quickly, and made of adobe and logs that were already in serious disrepair a decade later, when the Civil War began to disrupt life in the territory.

By August 1861, the Confederates under John Baylor had already claimed the southern half of New Mexico Territory and renamed it Arizona. The U.S. Army was convinced that invasion of Northern New Mexico was imminent, and that Fort Union was the key to holding the territory. However, the bluffs that protected it from wind also made it vulnerable to cannon fire should the Confederates be able to take them. A new fort was needed.

The Second Fort Union was built a mile and a half away from the first, in the open valley. Its earthwork walls, parapets, and moats covered 23 acres and were shaped like a star to accommodate 28 cannon. It was built by Hispanic

Volunteers since most of the Union Troops had been called east. The work went on 24 hours a day, with gangs of 200 men taking four hour shifts. The fort was ready by February 1862, when Confederates advanced up the Rio Grande and defeated the Union forces at the battle of Valverde. By March they had taken Albuquerque and then Santa Fe. It seemed that Fort Union was the only thing standing between the Confederates and the rich gold fields of Colorado.

Volunteers since most of the Union Troops had been called east. The work went on 24 hours a day, with gangs of 200 men taking four hour shifts. The fort was ready by February 1862, when Confederates advanced up the Rio Grande and defeated the Union forces at the battle of Valverde. By March they had taken Albuquerque and then Santa Fe. It seemed that Fort Union was the only thing standing between the Confederates and the rich gold fields of Colorado.Colonel Edward Canby, the Commander of Union forces in New Mexico Territory, said "The question is not of saving this post, but of saving New Mexico and defeating the Confederates in such a way that an invasion of this Territory will never again be attempted. It is essential to the general plan that this post should be retains if possible. Fort Union must be held."

The standoff at Fort Union never happened. No one on either side anticipated the gritty determination of the Colorado Volunteers when they refused to stay at the fort, and instead confronted the enemy in the mountains east of Santa Fe.

When visitors go to Fort Union National Monument, most of what they see is the remains of the third fort. Begun in 1863, this fort became the largest military outpost west of the Mississippi River. It served as an arsenal and depot, and was a safe resting place for travelers along the Santa Fe Trail. Again, its primary function was controlling the Indians and protecting Americans who used the trail.

When visitors go to Fort Union National Monument, most of what they see is the remains of the third fort. Begun in 1863, this fort became the largest military outpost west of the Mississippi River. It served as an arsenal and depot, and was a safe resting place for travelers along the Santa Fe Trail. Again, its primary function was controlling the Indians and protecting Americans who used the trail. The military abandoned the fort in 1891. By then the Apaches and Comanche had been subdued and the railroad had entered the state, effectively ending the

era of the Santa Fe trail. When I toured it in June 2017, there were few people there. I was able to walk among the ruins and read the interpretive signs without jostling crowds. The occasional sound of a bugle call broke the constant rush of the winds through the ruins. It was peaceful and pleasant, and I learned a lot from the small museum situated near the parking lot.

The fort is located 28 miles north of Las Vegas, New Mexico. To get there, take exit 366 off I-25 and go 8 miles north and west. The park, which is run by the National Park Service, is open from 8-5 from Memorial Day to Labor Day, and 8-4 the rest of the year. Check their website for special programs and tours.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a writer, historian, and novelist who lives in the mountains east of Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a writer, historian, and novelist who lives in the mountains east of Albuquerque, New Mexico.This article was originally published on July 22, 2017. This fort is one of the places depicted in Glorieta, the second in a trilogy about the Civil War in New Mexico, which will be published this spring. You can learn more about the first in the series, Valverde, by clicking here.

Published on January 01, 2020 03:39

The Charge of the Mule Brigade

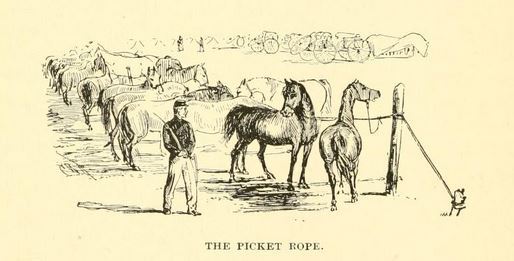

Mules were the backbone of both Confederate and Union Armies during the American Civil War. They pulled the supply wagons, the limbers and caisons for cannons, and the ambulances. One of the reasons that the Confederate Invasion of New Mexico failed was that they couldn't keep enough mules to hauls supplies. Many of the Confederate Army's mules were lost to theft by Indians and locals, and death due to starvation and disease.

Mules were the backbone of both Confederate and Union Armies during the American Civil War. They pulled the supply wagons, the limbers and caisons for cannons, and the ambulances. One of the reasons that the Confederate Invasion of New Mexico failed was that they couldn't keep enough mules to hauls supplies. Many of the Confederate Army's mules were lost to theft by Indians and locals, and death due to starvation and disease.The night before the battle of Valverde, a Union spy named Paddy Graydon managed to spook the Confederate's mules, who stampeded down to the Rio Grande. There Union soldiers managed to round them up.

In Hardtack and Coffee: The Unwritten Story of Army Life, Civil War veteran John D. Billings shares the story of another mule stampede. During the night of Oct. 28, 1863, Union General John White Geary and Confederate General James Longstreet were fighting at Wauhatchie, Tennessee. The din or battle unnerved about two hundred mules, who stampeded into a body of Rebels commanded by Wade Hampton. The rebels thought they were being attacked by cavalry and fell back.

To commemorate this incident, one Union soldier penned a poem based on Tennyson's Charge of the Light Brigade.

Charge of the mule brigade

Half a mile, half a mile,

Half a mile onward,

Right through the Georgia troops

Broke the two hundred.

“Forward the Mule Brigade!”

“Charge for the Rebs!” they neighed.

Straight for the Georgia troops

Broke the two hundred.

“Forward the Mule Brigade!”

Was there a mule dismayed?

Not when the long ears felt

All their ropes sundered.

Theirs not to make reply,

Theirs not to reason why,

Theirs but to make Rebs fly.

On! to the Georgia troops

Broke the two hundred.

Mules to the right of them,

Mules to the left of them,

Mules behind them

Pawed, neighed, and thundered.

Breaking their own confines,

Breaking through Longstreet's lines

Into the Georgia troops,

Stormed the two hundred.

Wild all their eyes did glare,

Whisked all their tails in air

Scattering the chivalry there,

While all the world wondered.

Not a mule back bestraddled,

Yet how they all skedaddled--

Fled every Georgian,

Unsabred, unsaddled,

Scattered and sundered!

How they were routed there

By the two hundred!

Mules to the right of them,

Mules to the left of them,

Mules behind them

Pawed, neighed, and thundered;

Followed by hoof and head

Full many a hero fled,

Fain in the last ditch dead,

Back from an ass's jaw

All that was left of them,--

Left by the two hundred.

When can their glory fade?

Oh, the wild charge they made!

All the world wondered.

Honor the charge they made!

Honor the Mule Brigade,

Long-eared two hundred!

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a Native New Mexican who writes in the high, thin air of the Sandia Mountains. Mules play an important role in Valverde, her historical novel set in New Mexico during the Civil War. Glorieta, the sequel to Valverde, will be published this spring.

This article was originally posted April 27, 2017.

Published on January 01, 2020 03:39

Celebrating a Civil War Coffee Hero

Maryland has one of the most unusual war monuments ever created. It doesn’t show a heroic charge or the valiant defense of a fortified position, but a soldier carrying a bucket and cup.

Maryland has one of the most unusual war monuments ever created. It doesn’t show a heroic charge or the valiant defense of a fortified position, but a soldier carrying a bucket and cup.The battle of Antietam was raging, and the boys from Ohio had been fighting since morning. Their spirits and their energy were waning. But then a 19-year-old private named William McKinley appeared, hauling a bucket of hot coffee. He ladled the steaming brew into the men’s tin cups. They gulped it down and resumed firing.

“It was like putting a new regiment in the fight,” their officer recalled.

When McKinley ran for president three decades late, people remembered this act of culinary heroism and voted him into office.

Coffee was such an important staple in the Union soldiers’ diet that the Army issued about 35 pounds of it to each soldier every year. They drank their hefty ration before marches and after marches, while on patrol, and, as McKinley proved, even during combat. Men ground the beans themselves, often by using their rifle butts to smash them in their tin cups, then brewed it using any water that was available to them. “Settling” the coffee, getting the grounds to sink to the bottom of the vats in which it was boiled, was so important that escaped slaves who were good at it found work as cooks in Union Army camps.

The Union blockade assured that most Confederates soldiers were not so lucky. The wide variety of attempts at creating substitutes speak to how desperately they wanted a cup of joe. Southerners tried making coffee substitutes from roasted corn, rye, chopped beets, sweet potatoes, chicory, and all sorts of other things. Although none of these brews were good, enjoying them was a source of patriotic pride. Gen. George Pickett, whose failed charge at Gettysburg is also a source of Southern pride, thanked his wife for the delicious “coffee” she had sent by saying that “no Mocha or Java ever tasted half so good as this rye-sweet-potato blend!”

Coffee may not have won the war nor earned McKinley his presidency, but it certainly was one of the small determining factors in both endeavors.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a writer who lives in rural New Mexico. The soldiers in her Civil War novel, Valverde, drink a lot of coffee. Glorieta, the sequel to Valverde, will come out this spring.

A recipe for Union Camp coffee and Confederate acorn coffee will be included in Salt Horse and Rio, a companion cookbook of Civil War recipes that will come out later this year.

This article was originally published April 23, 2017.

Published on January 01, 2020 03:39

Throwing out the Baby with the Potato Water

My critique partners can attest that sometimes I don't remember my own books. They've been through so many revisions that I can't remember what's in them and what's been expunged.

My critique partners can attest that sometimes I don't remember my own books. They've been through so many revisions that I can't remember what's in them and what's been expunged.I forget sub-plots. I can't remember characters' names. Often I've forgotten whole scenes.

This became a bit of a problem for me this past week. I'd had the honor of being asked to guest-write a post on Project Mayhem, a fabulous blog on writing hosted by a wonderful group of Middle Grade authors. I decided to address how little historical details can help readers grasp what a period of time was like, and how even the littlest of details could lead to some big questions. As an example, I decided to use a quirky little historical detail from my Civil War novel, The Bent Reed, which will be published in both paperback and ebook in September.

The quirky little historical detail in question is from a laundry scene; After washing Pa and Lijah's shirts, Ma dips them into a vat that contains the water left over from boiling potatoes. Why would she do this, you ask? Because the left-over potato water would have had starch suspended in it, and the starch would have made ironing the shirts easier, and the ironed shirts more crisp.

I remember learning this little historical detail in a Civil War era book of hints for housewives and being fascinated. I delight in little bits of trivia like this. I thought that it could lead to many interesting discussions about resource use and thriftiness.

As I wrote my post last week, I decided that this detail was a perfect example of how little bits of trivial information about everyday life in an historical period could not only bring that period to life for readers, but help readers ask big questions about how history informs the present day. And so I pulled out my manuscript and began searching for the scene.

And this is where I ran into a problem, because the scene wasn't there. I searched using potato and starch and laundry as key words. I found several scenes with laundry, but none involved a vat of potato water or even an iron.

Apparently, at some point in my rewriting and revision process I had cut this beloved little bit of trivia from my story and then forgotten about doing so.

Thinking about it now, I'm not surprised that I'd thrown out the vat of potato water. Even the most interesting bits of historical trivia have to either move the plot along or illuminate the characters. Although I cannot remember thinking so, I must have decided at some point that the potato water did neither.

Now that I think of it, I'm convinced that using the water left over from boiling potatoes show just how frugal Ma was. Like most women in her era, she used a good deal of her own elbow grease and determination to make sure to turn everything to good account.

Maybe I threw out the baby with the potato water.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is an educator and writer who lives in New Mexico. She has written two novels set in the Civil War: The Bent Reed, which takes place at Gettysburg, and Valverde, set in New Mexico. The sequel to Valverde, Glorieta, will be published this spring. This post was originally published July 14, 2014.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is an educator and writer who lives in New Mexico. She has written two novels set in the Civil War: The Bent Reed, which takes place at Gettysburg, and Valverde, set in New Mexico. The sequel to Valverde, Glorieta, will be published this spring. This post was originally published July 14, 2014.

Published on January 01, 2020 03:39