Jennifer Bohnhoff's Blog, page 34

January 21, 2019

A History of Chocolate

When I think of hot chocolate, I think of mugs of warm, sweet comfort. I lived in Massachusetts for three years in my childhood and have many memories of sledding until my fingers and toes burned with cold, then rushing home to cocoa in a steamy kitchen. I also think of a warm chair by the fire, and curling up with a good book.

But hot chocolate didn’t originate in the frozen north, and its history has more to do with diplomacy than comfort.

Still from a YouTube video on cacao production. Chocolate is made from the fruit of cacao trees. These small trees are native to Central and South America. They produce fruits, called pods, that are roughly the size of a person’s hand and are shaped like footballs. Within their tangy-sweet, gummy white flesh, each pod contains around 40 cacao beans that are bitter in taste and nothing like the chocolate we know and love. It appears that the ancient Olmecs of southern Mexico were the first to dry and roast cocoa beans. Because they kept no written history, it’s hard to know exactly where, when, or why the Olmecs began processing cacao beans, but pots and vessels dating back to around 1500 B.C. have traces of theobromine, a stimulant compound found in chocolate. Archeologists believe that early recipes were for drinks or gruels that were likely very bitter and used for ceremony rather than pleasure.

Still from a YouTube video on cacao production. Chocolate is made from the fruit of cacao trees. These small trees are native to Central and South America. They produce fruits, called pods, that are roughly the size of a person’s hand and are shaped like footballs. Within their tangy-sweet, gummy white flesh, each pod contains around 40 cacao beans that are bitter in taste and nothing like the chocolate we know and love. It appears that the ancient Olmecs of southern Mexico were the first to dry and roast cocoa beans. Because they kept no written history, it’s hard to know exactly where, when, or why the Olmecs began processing cacao beans, but pots and vessels dating back to around 1500 B.C. have traces of theobromine, a stimulant compound found in chocolate. Archeologists believe that early recipes were for drinks or gruels that were likely very bitter and used for ceremony rather than pleasure. After the Olmecs, the Mayans continued to use chocolate. Fortunately for historians, the Mayans kept written records, and through them we know that Mayan chocolate was thick and frothy. It often included chili peppers and honey. We know that cacao drinks were commonly drunk in everyday situations, and became part of the Mayan identity like wine is to the French, coffee to the Arab world, or craft beer to many locations today. Records indicate that many Mayan households drank chocolate with every meal.

But cacao wasn’t just a drink. Mayan written history indicates that chocolate drinks were incorporated into religious ceremonies, were used in celebrations, and helped finalize important transactions. These beverages were part of initiation rites for young men and celebrations marking the end of the Maya calendar year. In the early 12th century, chocolate was part of the dowry used to seal the marriage of a Mixtec ruler in the sacred Valley of Oaxaca.

The Aztecs continued the love of cacao beans, which they considered more valuable than gold. Although it’s likely that Spanish historians have exaggerated, they claimed that Montezuma drank fifty cups of chocolate each day, both for the energy it gave him, and as an aphrodisiac. It’s likely that Spanish conquistador Hernan Cortes was introduced to chocolate by Montezuma and in turn introduced it to the Spanish court of Philip II of Spain in 1544. Want to try making your own cacao beverage? Jennifer Bohnhoff will be giving away some supplies and cookbook to one lucky member of her Friends, Fan, and Family email list on February 1. To join in the drawing, sign up here.

Published on January 21, 2019 13:39

January 20, 2019

A Drum from History

Two weekends ago my husband and I took a little trip to Santa Fe. We spent a very delightful morning wandering through the New Mexico History Museum.

New Mexico's History Museum has a lot of history, even without the exhibits it contains. It is housed in a building called The Palace of the Governors, which was built by Pedro de Peralta soon after the King of Spain appointed him to be the governor of a Spanish territory that covered most of the American Southwest. That was 1610. Governors appointed by Spain, Mexico, and America have used the building, and it has served many other functions besides governor's mansion and museum. It is the oldest continuously occupied public building in the United States. I went specifically to see the relatively new exhibit on New Mexicans who served during WWI, but I don't have much to report on that.

I went specifically to see the relatively new exhibit on New Mexicans who served during WWI, but I don't have much to report on that.

What did impress me, though, was a snare drum that I hadn't noticed before.

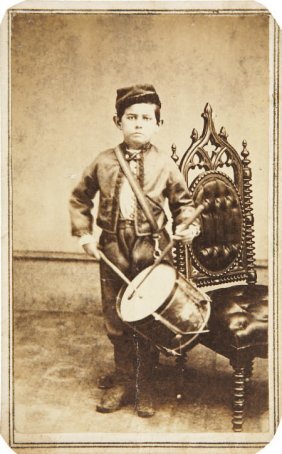

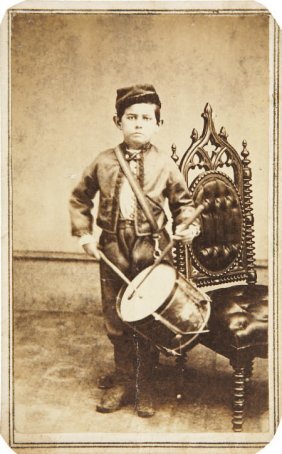

This snare drum, the label indicated, was found in the Pecos River about a decade after the Battle of Glorieta Pass. Willie, as I imagine him Those of you who've read

Valverde

, the first book in my trilogy of Civil War novels set in New Mexico, will know that it has a Confederate Drummer Boy named Willie. Willie is a fictional character, but this is exactly what I think he looked like: small and dark eyed, with a pale, round face. The drum that he would have carried into the battle of Valverde and, if he were there, the Battle of Glorieta Pass, looks very much like the one that was found abandoned in the Pecos River.

Willie, as I imagine him Those of you who've read

Valverde

, the first book in my trilogy of Civil War novels set in New Mexico, will know that it has a Confederate Drummer Boy named Willie. Willie is a fictional character, but this is exactly what I think he looked like: small and dark eyed, with a pale, round face. The drum that he would have carried into the battle of Valverde and, if he were there, the Battle of Glorieta Pass, looks very much like the one that was found abandoned in the Pecos River.

I'm presently writing a first draft of Glorieta , the second book in the series, and I'd had other plans for Willie than for him to lose his drum in the Pecos River. However, sometimes real life interprets fiction. I just may have to have him lose his drum in the river somehow. Valverde is available in paperback and ebook from Amazon. If you want more information on Valverde, or would like to buy a signed copy directly from the author, click here.

Valverde is available in paperback and ebook from Amazon. If you want more information on Valverde, or would like to buy a signed copy directly from the author, click here.

New Mexico's History Museum has a lot of history, even without the exhibits it contains. It is housed in a building called The Palace of the Governors, which was built by Pedro de Peralta soon after the King of Spain appointed him to be the governor of a Spanish territory that covered most of the American Southwest. That was 1610. Governors appointed by Spain, Mexico, and America have used the building, and it has served many other functions besides governor's mansion and museum. It is the oldest continuously occupied public building in the United States.

I went specifically to see the relatively new exhibit on New Mexicans who served during WWI, but I don't have much to report on that.

I went specifically to see the relatively new exhibit on New Mexicans who served during WWI, but I don't have much to report on that.What did impress me, though, was a snare drum that I hadn't noticed before.

This snare drum, the label indicated, was found in the Pecos River about a decade after the Battle of Glorieta Pass.

Willie, as I imagine him Those of you who've read

Valverde

, the first book in my trilogy of Civil War novels set in New Mexico, will know that it has a Confederate Drummer Boy named Willie. Willie is a fictional character, but this is exactly what I think he looked like: small and dark eyed, with a pale, round face. The drum that he would have carried into the battle of Valverde and, if he were there, the Battle of Glorieta Pass, looks very much like the one that was found abandoned in the Pecos River.

Willie, as I imagine him Those of you who've read

Valverde

, the first book in my trilogy of Civil War novels set in New Mexico, will know that it has a Confederate Drummer Boy named Willie. Willie is a fictional character, but this is exactly what I think he looked like: small and dark eyed, with a pale, round face. The drum that he would have carried into the battle of Valverde and, if he were there, the Battle of Glorieta Pass, looks very much like the one that was found abandoned in the Pecos River.I'm presently writing a first draft of Glorieta , the second book in the series, and I'd had other plans for Willie than for him to lose his drum in the Pecos River. However, sometimes real life interprets fiction. I just may have to have him lose his drum in the river somehow.

Valverde is available in paperback and ebook from Amazon. If you want more information on Valverde, or would like to buy a signed copy directly from the author, click here.

Valverde is available in paperback and ebook from Amazon. If you want more information on Valverde, or would like to buy a signed copy directly from the author, click here.

Published on January 20, 2019 00:00

January 14, 2019

The Continuing Saga of the amaryllis that could

On the last day of last year I posted a story about an amaryllis bulb that had started to grow while stick in the box. I didn't think it would amount to much, but I was impressed with how determined it was to become all it could be. You can read that blog entry and see a picture of that first, failed, flower here.  That determined little bulb has surprised me. After I cut off the first, stunted blossom, the leaf part started to stand straight. It's turned green. And surprise of surprises, it has two more flower blossoms coming!

That determined little bulb has surprised me. After I cut off the first, stunted blossom, the leaf part started to stand straight. It's turned green. And surprise of surprises, it has two more flower blossoms coming!

There's a big moral here for everyone: sometimes life is hard. Sometimes it can leave a person a little damaged. But perseverance - that quality now popularized as grit - can see you through.

I'll continue to post pictures of my miracle amaryllis. I'm hoping to follow its lead and make this year the year that I overcome a lot of obstacles, stand tall, and really bloom where I am planted. Here's wishing the same for you. Jennifer Bohnhoff is a middle school English teacher in rural New Mexico and the author of a number of novels for middle school and above. You can learn more about her books here.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a middle school English teacher in rural New Mexico and the author of a number of novels for middle school and above. You can learn more about her books here.

That determined little bulb has surprised me. After I cut off the first, stunted blossom, the leaf part started to stand straight. It's turned green. And surprise of surprises, it has two more flower blossoms coming!

That determined little bulb has surprised me. After I cut off the first, stunted blossom, the leaf part started to stand straight. It's turned green. And surprise of surprises, it has two more flower blossoms coming!There's a big moral here for everyone: sometimes life is hard. Sometimes it can leave a person a little damaged. But perseverance - that quality now popularized as grit - can see you through.

I'll continue to post pictures of my miracle amaryllis. I'm hoping to follow its lead and make this year the year that I overcome a lot of obstacles, stand tall, and really bloom where I am planted. Here's wishing the same for you.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a middle school English teacher in rural New Mexico and the author of a number of novels for middle school and above. You can learn more about her books here.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a middle school English teacher in rural New Mexico and the author of a number of novels for middle school and above. You can learn more about her books here.

Published on January 14, 2019 09:18

January 7, 2019

Manic Muffins

Ever have manic mornings when you wish you could get something good, hot, and satisfying on the table quickly? I know I do.

Having Manic Muffin Mix in your pantry might just help. Today I'll post the recipe for the mix and for basic muffins. On the first Monday of every month throughout 2019 I'll post a new recipe that uses the mix. That adds up to 12 different muffins that I hope will take a little of the mania out of your mornings. Manic Muffin Mix

9 cups flour

9 cups flour2 1/2 cups sugar

1 cup buttermilk blend

3 TBS baking powder

1 TBS baking soda

1 TBS salt

1 1/2 TBS cinnamon

1 1/2 tsp nutmeg

Mix all ingredients well and store in a sealable container.

Everything in this recipe is a common pantry staple with the exception of buttermilk blend. I use Saco Pantry Cultured Buttermilk Blend, which is kept next to the yeasts and baking powders in my local grocery store. If you can't find this, or a similar product, substitute powdered milk and your muffins will turn out just fine. Basic Manic Muffins These are sweet and a little spicy. Making up a batch will make your kitchen smell wonderful. I recommend you put out butter and jelly to go on them, but my husband likes to split them and slather them with peanut butter. Preheat oven to 350. Put muffin papers in 12 standard-sized muffin cups, or grease cups with spray oil.

Everything in this recipe is a common pantry staple with the exception of buttermilk blend. I use Saco Pantry Cultured Buttermilk Blend, which is kept next to the yeasts and baking powders in my local grocery store. If you can't find this, or a similar product, substitute powdered milk and your muffins will turn out just fine. Basic Manic Muffins These are sweet and a little spicy. Making up a batch will make your kitchen smell wonderful. I recommend you put out butter and jelly to go on them, but my husband likes to split them and slather them with peanut butter. Preheat oven to 350. Put muffin papers in 12 standard-sized muffin cups, or grease cups with spray oil.

Mix together in a large bowl. The batter should be slightly lumpy:

Mix together in a large bowl. The batter should be slightly lumpy: 2 eggs

1 1/2 tsp vanilla

1 cup water

1/2 cup oil

2 3/4 cup manic muffin mix.

Fill muffin cups 3/4 full. Bake for 18-20 minutes until the tops of the muffins are golden.

These muffins freeze well. If your family is small, I recommend putting single muffins in sandwich bags, then putting them all in a ziplock freezer bag so you can pull them out one at a time. Frozen muffins are ready to serve after being reheated in the microwave on high for 30 seconds.

These muffins freeze well. If your family is small, I recommend putting single muffins in sandwich bags, then putting them all in a ziplock freezer bag so you can pull them out one at a time. Frozen muffins are ready to serve after being reheated in the microwave on high for 30 seconds.  Jennifer Bohnhoff writes fiction for middle schoolers and adults, but she has to eat, too. You can find out more about her at her website or Facebook page.

Jennifer Bohnhoff writes fiction for middle schoolers and adults, but she has to eat, too. You can find out more about her at her website or Facebook page.

Published on January 07, 2019 00:00

December 31, 2018

Bloom as if your life depended on it

My Christmas miracle. Some dear friends came to visit just before Christmas. They brought an amaryllis that was part of a kit: a bare bulb, a red planter can, and a disk of dehydrated soil, all sealed up in a box and ready to put together.

My Christmas miracle. Some dear friends came to visit just before Christmas. They brought an amaryllis that was part of a kit: a bare bulb, a red planter can, and a disk of dehydrated soil, all sealed up in a box and ready to put together.What none of us realized until we opened the box was that it had been kept in a place that was too warm. The plant had begun growing in the dark enclosure and the flower stem, when it met the lid of the box, turned downward seeking space. What we found were white nubs of leaves and

a ghostly pale bud bending down. It was clear that this plant would never amount to much; it had been crippled by the box and was doomed from the moment it began its premature growth. Obviously the thing to do was to throw the bulb away.

But I didn't. I planted it anyway and set it in a sunny window. And on Christmas Day, defying everyone's predictions, it bloomed.

If I were the writer of feel-good stories for children, I would say that my little amaryllis saw the sun, and the flower bulb changed directions and stood up, proudly becoming the most beautiful of Christmas flowers. But this isn't the story of the Ugly Duckling. This story is more honest and more true. The stunting that occurred in the box dealt irrevocable damage.This poor bulb didn't become much to look at. On New Year's Day the petals are already browning on the edges and the leaves, although a little greener, still haven't grown much.

This is the message this amaryllis brings us: We can be irrecoverably damaged by this world, but in spite of all that is done to us we must bloom. We will not all become the most beautiful of blooms, but we can be the bravest.

Published on December 31, 2018 12:04

December 24, 2018

A Clear Creek Christmas

Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index...

Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index...  The wind outside our little tent howled pitifully, sounding God-forsaken and destitute. I wasn’t fooled. Along with dry, sharp snow, that gale was throwing around plenty of gold dust. That’s why I’d laid down a claim among these desolate peaks. Rocky Mountains winds don’t howl so much as shout for joy. No land has been more God-blessed rich since God laid down manna in the wilderness. All a man has to do to prosper in this wilderness is listen with an attentive ear and open his eyes.

The wind outside our little tent howled pitifully, sounding God-forsaken and destitute. I wasn’t fooled. Along with dry, sharp snow, that gale was throwing around plenty of gold dust. That’s why I’d laid down a claim among these desolate peaks. Rocky Mountains winds don’t howl so much as shout for joy. No land has been more God-blessed rich since God laid down manna in the wilderness. All a man has to do to prosper in this wilderness is listen with an attentive ear and open his eyes.George Nelson, who held up the other side of our foursome, groaned. George is a big, meaty galoot, with broad hands that can rip apart rock and a back that can carry a hundred-weight without complaint. But he’s not big on brains. Without me, he’d have frozen, or starved, or been cheated out of his claim long ago.

Luther and Key slept between George and me , the four of us nesting like spoons in a drawer. It can be hard to sleep when one of us twitches in the throes of a nightmare or has the trots from some rancid bacon or undercooked potato, but sleeping like this keeps us from freezing. Out here, comfort is secondary to survival.

“Samuel? You awake?” George’s voice was somewhere between a whisper and a groan. I might not have heard it over the wind if I weren’t already listening for it.

“I am,” I answered. “Still an hour or such ‘til dawn. Need to roll over?” That’s what we did, turning as one when one side of us or the other got too cold. Right now I was facing out, my back warm against Key and the blankets tucked under my knees. George, with his back out, would be the first to feel the chill.

“I’m fine,” George said with a sigh that matched the wind and told me that he really wasn’t. “Just ruminating. This here’s Christmas Eve, ain’t it?”

“That it is,” I agreed. I let the conversation lie, waiting for George to tell me why that would matter in a place such as this, where the closest church is miles away, in Golden City.

“Samuel, what did your mother serve on Christmas when you were a child?”

Ah. So this wasn’t about going to church. The big baby was missing his mother and the comforts of holiday traditions. I salivated, thinking of the sumptuous meals of my childhood. “T’warn’t my mother made Christmas dinner. We’d all bundle up and take the sled to grandmother’s. Oh, Lordy, what a feast she prepared! She’d roast a turkey of uncommon size, and there’d mashed potatoes and turnips, and boiled onions, and dressed celery. And always mincemeat pie for dessert. How about you?”

“Roast pig, and applesauce, mashed sweet potatoes and pickles. And large pitchers of sweet cider,” George said. “My granny was there, too, but she was addled in the head by the time I come along. Couldn’t be trusted for anything beyond shelling peas.”

“Boiled goose with oyster sauce,” Luther pitched in. “And plum pudding when my Father hadn’t drunk away all the money.” I didn’t know Luther was awake until he spoke. Luther is thin as a rail, which is why he sleeps in the middle most nights. He’s all elbows and knees, and his words can be as sharp as his elbows. He didn’t often share much from his childhood, but what I’d heard was ugly and had turned him mean. But I understood Luther. If not for me, he would have been killed in a squabble over something of no account. My men need my leadership.

“You’re making my stomach pinch,” Key’s melodious voice chimed in irritably. “Go back to sleep, the lot of you.”

I chuckled. Key’s like a feisty little lap dog among a pack of mastiffs. He’s just a little slip of a lad, too young, even, to shave. When he sings, he sounds like a girl. Or, perhaps, an angel. But the thin arm he throws around me when we sleep is as strong as bailing wire. His manner can be just as steely. Key’s young, but he’s been through a lot that’s hardened him.

Key’s orphaned and alone in this world. He was working at a livery stable in Denver in exchange for one meal a day and the right to sleep in the hay. I happened past the stable and saw the stable owner, a man well known for his irascible nature, beating him him for being a lazy Irishman. Key’s name, I should tell you, is not really K-E-Y. It’s C-I-A-N, and it’s pronounced “key in.” It’s Irish, but I don’t hold that against him. I am of a liberal mind when it comes to foreigners. Especially those who work hard and take hardship without complaint.

The beating clearly hurt, but Key was determined not to give the man the satisfaction of tears. I decided then and there that Key was the sort of fellow I could use in my company. I offered him a position in my growing company, signing him on as cook and general errand boy.

“Since everyone’s awake, let’s roll over. Key, tell us about the Irish. What do they eat on Christmas?”

Key tensed, and I sympathized with him. His lineage sets him apart and marks him as a target for derision. But his accent itself marks him. “I canna speak for all the Irish. I left Ireland when I was but a wee lad. But mi Ma, she was a canny cook, and thrifty. She took whatever the other housewives passed by and made it a feast.”

“No special foods? On Christmas?” Luther’s voice cut sharply, derisively.

“We had special foods. Every Christmas Eve, we had oyster stew.”

“Oyster stew? I love oysters,“ George said. I smiled, glad that we’d just rolled over so that George wouldn’t drool on Luther.

“So do I,” Luther said earnestly.

“You’ve never had them as rich as mi Ma made.” Key’s voice quavered on the edge of tears.

Inspiration dawned on me as clear and bright as a prairie sunrise. “If I got a tin of oysters, could you make stew like your Ma used to make?” I asked.

Key belly-crawled halfway out of the blankets and rummaged through his rucksack until he pulled out a metal handle with a bull’s head and a wicked, curved knife at the end. The fact that I could see it made me realize that my dawning ideas weren’t the only dawn that had occurred. “Here’s me tin can opener!”

“And a fine one it is, too,” Luther said, grabbing it away and examining it closely.

“Stole it off an English tar in Boston Harbor,” Key said proudly.

“Oysters . . .” George gurgled dreamily.

“Oysters it is, then.” I threw back the blankets and pulled my feet into my shoes, pleased that I’d thought of how to make this holiday a good one for me and my men.

“And cream and butter. And a little bit of black pepper to crack over it!” Key shouted at my retreating back.

The tent was still deep in the shadow of a nearby ridge, but the peaks above and the valley below both gleamed golden in sunshine. I breathed in the cold, pine-tinged air and began the long trudge down to Golden City. As I passed into the sunshine the sparkle in the snow changed from silver to golden, but I knew that I’d already found my true goldmine: men who would follow me to the ends of the earth and back because I’d won their loyalty. With oysters.

Published on December 24, 2018 08:00

December 18, 2018

A short Inquiry into Canning, Oysters, and Christmas

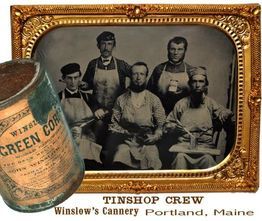

In my research on the second book of my series on the Civil War in New Mexico I've been reading a lot of journals and diaries left behind by men in the Colorado Volunteers. Many of them mention acquiring tins of oysters. It's made me wonder why men so far from the ocean seemed inordinately fond of a food that seems unlikely. Recently a dear friend of mine published a little booklet on oyster stew, which he called a New Mexico Christmas Eve tradition. That got me thinking about oysters, about Christmas, and about how they might have become connected.

In my research on the second book of my series on the Civil War in New Mexico I've been reading a lot of journals and diaries left behind by men in the Colorado Volunteers. Many of them mention acquiring tins of oysters. It's made me wonder why men so far from the ocean seemed inordinately fond of a food that seems unlikely. Recently a dear friend of mine published a little booklet on oyster stew, which he called a New Mexico Christmas Eve tradition. That got me thinking about oysters, about Christmas, and about how they might have become connected.Canning and oysters both boomed at the same time in American history. The one helped the other become accessible, cheap, and popular.

Canning was invented at the behest of Napoleon Bonaparte, who famously said that an army travels on its stomach. The first metal cans were made of tin-lined cast iron and were almost impregnable. Most people used a chisel and hammer to open them.

By the 1840s tin smiths were fashioning cans out of thinner, more easily breached tin. The invention of the can opener by Ezra Warner followed in 1858. Warner's can openers were standard issue to cooks during the Civil War.

Another early can opener, called the Bully Beef Opener, was common in England. This opener was decorated with a bull's head. It has been said that what Americans call Corned Beef, British call Bully Beef because the cans it was stored in were opened with a Bully Beef Opener. This may be apocryphal, though; other sources suggest that the British word for this product is an anglicized version of the French boeuf bouilli, or boiled beef.

Another early can opener, called the Bully Beef Opener, was common in England. This opener was decorated with a bull's head. It has been said that what Americans call Corned Beef, British call Bully Beef because the cans it was stored in were opened with a Bully Beef Opener. This may be apocryphal, though; other sources suggest that the British word for this product is an anglicized version of the French boeuf bouilli, or boiled beef.  The Chesapeake Bay teemed with oyster beds. Canning proved a good way to save the prolific harvest. Early on, oysters were stored in twin tin containers such as these, which were then placed in a taller wooden barrel. The remaining space was packed with ice before they were shipped by

The Chesapeake Bay teemed with oyster beds. Canning proved a good way to save the prolific harvest. Early on, oysters were stored in twin tin containers such as these, which were then placed in a taller wooden barrel. The remaining space was packed with ice before they were shipped by

rail and steamboat across the entire country and into the territories. Companies such as Platt & Co, founded in 1848, sent ice-packed tins of oysters to men who'd gone west to California and Colorado in search of gold. These men, faced with hardships and shortages of essentials, so nostalgically yearned for the east coast foods of their childhoods that they were willing to pay outrageous amounts for a little taste of home.

rail and steamboat across the entire country and into the territories. Companies such as Platt & Co, founded in 1848, sent ice-packed tins of oysters to men who'd gone west to California and Colorado in search of gold. These men, faced with hardships and shortages of essentials, so nostalgically yearned for the east coast foods of their childhoods that they were willing to pay outrageous amounts for a little taste of home.I grew up eating oyster stew on Christmas Eve. My maiden name is Swedberg, a Swedish name, but I'd thought my own family's tradition of oyster stew on Christmas eve came from my Norwegian grandfather. My research, however, didn't credit Scandinavians, but

Irish immigrants with making oyster stew a traditional Christmas Eve dish. Thousands of Irish entered the United States in search of better lives during the years of the Potato Famine, 1845-1852. Most of the Irish immigrants were Catholic and fasted from eating red meat on Christmas Eve. Instead, they ate a simple stew made from ling, a type of fish not available in America.

Irish immigrants with making oyster stew a traditional Christmas Eve dish. Thousands of Irish entered the United States in search of better lives during the years of the Potato Famine, 1845-1852. Most of the Irish immigrants were Catholic and fasted from eating red meat on Christmas Eve. Instead, they ate a simple stew made from ling, a type of fish not available in America.The Ling, which had been dried and heavily salted to preserve it, was cooked in a rich broth of milk, butter, and pepper, yet remained chewy from being dried. Once they were in America, Irish cooks substituted oysters for ling because the cheap and easily obtainable oysters tasted briny and had a similar, chewy texture.

I've got some Irish in me. Are they the ancestors who began my family tradition? I don't know any other New Mexicans who eat oyster stew on Christmas eve, and wonder if my friend Kirk's family eats it because his parents and my parents were friends and the Austins learned to eat it from the Swedbergs. The origins of traditions can be hard to pin down.

I've got some Irish in me. Are they the ancestors who began my family tradition? I don't know any other New Mexicans who eat oyster stew on Christmas eve, and wonder if my friend Kirk's family eats it because his parents and my parents were friends and the Austins learned to eat it from the Swedbergs. The origins of traditions can be hard to pin down.If this is the year you are inspired to go back in history and try this traditional dish you might want to try the recipe my friend Kirk Austin has published on Amazon.

Is oyster stew among your family's Christmas traditions? I'd love to know if it is, and where you think your family picked up its traditions.

Coming soon: a short story featuring characters from my work in progress, inspired by oyster stew.

Published on December 18, 2018 00:00

December 10, 2018

Kit Carson, New Mexico Celebrity

The author in the courtyard of Kit Carson's house, Taos. Last month I took a weekend trip up to Taos, New Mexico to enjoy a little R&R and to snoop around a bit.

The author in the courtyard of Kit Carson's house, Taos. Last month I took a weekend trip up to Taos, New Mexico to enjoy a little R&R and to snoop around a bit. Taos is as historic as a town can get. The area has been inhabited since around 1,000 AD. When the first European in the area, Hernando de Alvarado, saw the adobe walls of Taos Pueblo shining in the evening sun, he believed that he'd discovered the fabled El Dorado, or city of gold.

Beginning in the early 1700s, Taos was the site of annual summer trade fairs, where Comanches, Kiowas and other Plains Indians came to trade captives for horses, grains, and trade goods brought up from Mexico. It was also the center for the fur trade, attracting the wild mountain men who hunted beaver throughout the Rocky Mountains. One of the most famous of the mountain men, Kit Carson, married a local girl and made Taos his home. Located just off the town plaza, the Carson home was probably built around 1825. It is a one-story adobe with three rooms: a living/sleeping room, a kitchen, and a parlor/office. The ceilings and doorways were low. Although

The fireplace in the kitchen of the Carson house was set in a corner, with access from two sides.

The fireplace in the kitchen of the Carson house was set in a corner, with access from two sides.

now large and filled with glass, the original windows would have been very small, made out of thin sheets of mica, and barred with iron rods to protect against Indian raids.

now large and filled with glass, the original windows would have been very small, made out of thin sheets of mica, and barred with iron rods to protect against Indian raids.Much of the day to day living in the Carson house occurred in the central courthouse of the house. It was here that Josepha would have done the laundry, cooked most of the meals, and processed wool. The well and outhouse would have been in the courtyard as well. During the time that Carson was the Indian agent for the area, Indians often camped in the court yard while waiting for him to make decisions.

Kit and Josepha moved the family to Colorado in 1867, when he became the commander of Fort Garland, but they loved Taos enough that they were both buried there, in the cemetery that is just a short walk away and is now part of Kit Carson Park. Jennifer Bohnhoff is the author of several novels, including on in which Kit Carson has a small roll. You can read more about Valverde, a historical novel set in New Mexico during the Civil War, by clicking here.

Published on December 10, 2018 19:08

December 3, 2018

The Bohnhoff Family Christmas Tree

Some of the Bohnhoff clan went Christmas tree hunting in the National Forest during Thanksgiving weekend. The trip was similar to the one that the Anderson family made in Jennifer's middle grade novel Jingle Night. You can read about the trip here, and you can read more about Jingle Night here. What do you think? * Indicates required field This is the tree we cut in the Jemez Mountains over Thanksgiving week. It's not the full, thick kind of tree that people buy in tree lots. What do you think? * * It looks like a Charlie Brown Christmas tree.All that space makes more room for the ornaments.Nope. Give me a full, thick tree any day.You drove into the mountains for that?!I like it! Submit  Here's wishing you and yours a memorable holiday season, with lots of time together with those you love.

Here's wishing you and yours a memorable holiday season, with lots of time together with those you love.

Here's wishing you and yours a memorable holiday season, with lots of time together with those you love.

Here's wishing you and yours a memorable holiday season, with lots of time together with those you love.

Published on December 03, 2018 19:57

November 26, 2018

Hunting for trees and stories

A little Bohnhoff in a big Bohnhoff jacket. Let me begin by asserting that, without a doubt, the Bohnhoff family is not the Anderson Family that shows up Jingle Night or Tweet Sarts, the two books currently in my series for middle grade readers called Anderson Family Chronicles. That being said, there are some similarities.

A little Bohnhoff in a big Bohnhoff jacket. Let me begin by asserting that, without a doubt, the Bohnhoff family is not the Anderson Family that shows up Jingle Night or Tweet Sarts, the two books currently in my series for middle grade readers called Anderson Family Chronicles. That being said, there are some similarities.Take, for instance, Christmas tree hunting, which the Andersons do in Jingle Night, and which the Bohnhoffs did this weekend. Both families went to the Jemez mountains

to get their tree, and both families had mishaps.

Some of the Bohnhoffs had come from out of State and needed some time to run a few essential errands before we headed out. Not knowing how long the errands would take, I packed a lunch and cocoa for us. We were finally ready to go at noon. Shouldn't we have lunch I asked? "Not until we get there," my husband, who is definitely not the stubborn, slightly OCD, over organized father of the Anderson family said.

The snowy hillside made a perfect winter wonderland.

The snowy hillside made a perfect winter wonderland.  The Bohnhoffs and their trophy trees. So we drove the one hour journey to the mountains. Did we eat then? No, for fear we'd not find the right tree before the sun set.

The Bohnhoffs and their trophy trees. So we drove the one hour journey to the mountains. Did we eat then? No, for fear we'd not find the right tree before the sun set.No sooner than we got out of the car did we realize that three of us had forgotten to pack jackets. We improvised, pulling apart shells and inner linings to share.

Unlike the Andersons, we managed to find our trees without tears or puppet drownings. I'm not in the "trophy" picture because although we brought a camera that had a timer and a tripod, we forgot to the put the memory card in the camera, so I took this with my phone.

My husband managed to wrap the tree in plastic and tie it to the roof of the car without roping himself out - proving he's better than the Anderson dad. By the time the tree was in place we were all too cold to eat, so we finally at on the drive home.

My husband managed to wrap the tree in plastic and tie it to the roof of the car without roping himself out - proving he's better than the Anderson dad. By the time the tree was in place we were all too cold to eat, so we finally at on the drive home.Truth may be stranger than fiction sometimes, but it's rarely as funny. The Bohnhoff's tree hunting trip is less interesting than the Anderson's one. Is our tree any better? Once it's up and decorated I'll post a picture of it and let you decide.

Jingle Night is available in ebook and paperback. Want a signed copy? Get one here.

Published on November 26, 2018 19:56