Jennifer Bohnhoff's Blog, page 38

July 13, 2017

Investigating a New Mexican Mystery - or Hoax

It's called Inscription Rock, the Phoenician Rock, the Decalogue Stone, or the Commandment Stone. Whatever you call it, this rock inscribed with strange markings, west of Los Lunas, New Mexico, is a curiosity, and probably a hoax.

It's called Inscription Rock, the Phoenician Rock, the Decalogue Stone, or the Commandment Stone. Whatever you call it, this rock inscribed with strange markings, west of Los Lunas, New Mexico, is a curiosity, and probably a hoax. The Phoenician Rock lies at the base of Mystery Mesa, sometimes called Hidden Mesa, in a remote area controlled by the BLM. It is west of Los Lunas and about 35 miles southwest of Albuquerque. A BLM permit is required to enter the area.

The stone is covered with what experts have called Paleo-Hebrew script, which is practically identical to the Phoenician script. Also included, according to some experts, are Samaritan and Greek letters. Some have argued that the stone uses modern Hebrew punctuation, indicating that it is a modern creation. Other researchers point out stylistic and grammatical errors to question its authenticity.

What it says depends on who translates it. Some ethnographers have suggested that the text is an early version of the Ten Commandments. Others say that it tells the story of a Phoenician sailor, lost at sea, who yearns to return home.

The writing is set at an angle, suggesting that it shifted or fell from its original position.

The first time the stone is mentioned in historical records is in 1933, when University of New Mexico archaeology professor Frank Hibben clains to have been led to it by an unnamed and uncredited Indian guide. Hibben writes that his guide claimed to have found it as a boy in the 1880s. After Hibben announced his discovery, a Los Lunas man named Florencio Chavez announced that his grandfather claimed to have seen the rock in 1800.

I've been to the rock several times, and while I am no expert on ancient texts, I find the rock interesting. Of more interest to me, though, are the Indian pictographs and ruins on the top of the mesa. This site was an outlier community that linked Acoma Pueblo to the west with the Rio Grande and the trading communities that strung along that ribbon of water, tying the arid southwest to the Mayan Civilizations to the south and the nomadic plains tribes to the northeast.

What those Indians thought of the strangely marked rock - if it was indeed there when they were - if a real mystery.

Published on July 13, 2017 00:00

July 6, 2017

Bridges, Part 2

Roebling Bridge, Cincinnati. Photo by Nathan Holth. http://ow.ly/f1UY30djvIB Recently my husband and I drove through Cincinnati. We walked across this bridge to get from our hotel in Covington, Kentucky, to The Great American Ballpark, where the Cincinnati Reds were playing the Chicago Cubs.

Roebling Bridge, Cincinnati. Photo by Nathan Holth. http://ow.ly/f1UY30djvIB Recently my husband and I drove through Cincinnati. We walked across this bridge to get from our hotel in Covington, Kentucky, to The Great American Ballpark, where the Cincinnati Reds were playing the Chicago Cubs. I was struck by the beauty of this bridge as I walked across it.

It wasn't until I saw the plaque on the north side of the bridge, on the return journey, that I realized the significance of the bridge, which helps to explain its beauty.

This bridge is named the Roebling Bridge after its designer, John Roebling. When it was opened in December 1867, its 1,057 foot span was the longest in the world. Roebling, an engineer who had emigrated from Prussian Germany, developed the iron-wire cables that made suspension bridges of this type possible. This bridge was the first that used the new technology. Roebling and his son would go on to design and build the much larger and more famous Brooklyn Bridge.

The platform the cars drive on is not a solid roadbed, but a grid of metal mesh that makes the car tires "sing" as they cross. The sound is both eerie and harmonious. I found it disconcerting to look down through the mesh and see the ripples on the water below. Strange, that something so ethereal can hold the weight of so many racing cars.

By happy coincidence, when I opened the Wall Street Journal later that evening, I found a review for Chief Engineer, a new biography of the Roeblings by Erica Wagner. That review provided a lot of background information on the bridge and its designers. It is a book I will certainly have to pick up soon.

Published on July 06, 2017 00:00

July 5, 2017

Bridges, part 1

The Roebling Bridge, Cincinnati. Nathan Holth, photographer. http://historicbridges.org/bridges/br... Coincidences can be the bridges between unrelated experiences, enriching understanding in surprising ways. I'm always thrilled and surprised when coincidences align without my planning them to.

The Roebling Bridge, Cincinnati. Nathan Holth, photographer. http://historicbridges.org/bridges/br... Coincidences can be the bridges between unrelated experiences, enriching understanding in surprising ways. I'm always thrilled and surprised when coincidences align without my planning them to.Last week my husband and I drove from our home in Albuquerque to Pittsburgh to visit one of our sons and his family. I stopped by my local library before the trip so I could pick up some books on CD to listen to while on the road. I ended up getting Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin, mostly because it was long, of historical interest, and I had never read it before. Written in 1852, this novel depicted the many horrors of slavery, and his long been regarded the spark that began the Civil War. It is not an easy book to read: Stowe's characters spend a lot of time pontificating, and there is a racist tone to the book that modern readers will find offensive. However, the plot is filled with exciting twists and turns, and the characters feel very read. Readers who enjoy Dickens will enjoy this book.

One of the most dramatic scenes in the book is of Eliza escaping over an ice-clogged river, her young son cradled in her arms.

Her master, Mr. Shelby, has sold her son to slave traders to settle his debts, and Eliza chooses to escape to Canada rather than allow him to be sent to the slave market in New Orleans.

Her master, Mr. Shelby, has sold her son to slave traders to settle his debts, and Eliza chooses to escape to Canada rather than allow him to be sent to the slave market in New Orleans.  It is winter, and the ferry is not running because the river is clogged with ice. Rather than be caught by the pursing slavers and their dogs, Eliza jumps from ice floe to ice flow, escaping Kentucky for the free state of Ohio. It wasn't until my husband and I reached Covington, Kentucky, that I really realized what a daring feat Eliza had achieved. Covington is just over the river - the Ohio River - from Cincinnati, Ohio. I stood on the banks and realized that this was the river that Eliza crossed.

It is winter, and the ferry is not running because the river is clogged with ice. Rather than be caught by the pursing slavers and their dogs, Eliza jumps from ice floe to ice flow, escaping Kentucky for the free state of Ohio. It wasn't until my husband and I reached Covington, Kentucky, that I really realized what a daring feat Eliza had achieved. Covington is just over the river - the Ohio River - from Cincinnati, Ohio. I stood on the banks and realized that this was the river that Eliza crossed. The Ohio is a mighty river. It is broad and it is deep. Looking at it, I realized that Eliza must have been far more desperate and far braver than I had imagined.

I hadn't picked Uncle Tom's Cabin for any specific reason when I went on this trip, but this view of the river ended up being the bridge between the real world and the novel that really brought the story to life for me.

Published on July 05, 2017 00:00

June 26, 2017

Magical History Tour

Sometimes you just gotta get out of Dodge -

Sometimes you just gotta get out of Dodge - or Albuquerque, as the case may be.

This weekend I joined my husband and a couple of friends on a quick road trip to historical sites in Northern New Mexico and Southern Colorado.

We spent Friday night in the Plaza Hotel, a grand old hotel built in 1881, at the peak of Las Vegas, New Mexico's rail road building boom. The next morning we drove past the

Casteneda Hotel. This former Harvey House opened in 1898 and was the site for Rough Rider Reunions that were attended by Teddy Roosevelt himself. It's badly in need of restoration, and I hope those involved can get the funding to bring her back to her former glory.

That night we slept in the Tarabino Inn, in Trinidad, Colorado. Built in 1907 by six brothers who immigrated here from Italy, it stands as a testament to the money that poured into the area during the mining boom years, and to one of the many ethnicities that immigrated here for a chance at a better life.

That night we slept in the Tarabino Inn, in Trinidad, Colorado. Built in 1907 by six brothers who immigrated here from Italy, it stands as a testament to the money that poured into the area during the mining boom years, and to one of the many ethnicities that immigrated here for a chance at a better life.We then toured the ruins of Fort Union, which was active during the Civil War and protected settlers traveling along the Santa Fe Trail, which has grown so faint over time that we had trouble seeing it.

We then drove north to Bent's Fort, a trading post and safe respite on the Santa Fe trail that was active in the 1830s and 40s. Using plans drawn by an Army officer who sketched plans of the fort while he recuperated from an illness, the National Parks Service rebuilt the fort, and it is now a living history museum.

We then drove north to Bent's Fort, a trading post and safe respite on the Santa Fe trail that was active in the 1830s and 40s. Using plans drawn by an Army officer who sketched plans of the fort while he recuperated from an illness, the National Parks Service rebuilt the fort, and it is now a living history museum.

The four of us jammed a lot of history into a weekend, and the trip was, indeed, magical - at least to this history buff.

The four of us jammed a lot of history into a weekend, and the trip was, indeed, magical - at least to this history buff.

Published on June 26, 2017 09:25

April 27, 2017

The Charge of the Mule Brigade

Mules were the backbone of both Confederate and Union Armies during the American Civil War. They pulled the supply wagons, the limbers and caisons for cannons, and the ambulances. One of the reasons that the Confederate Invasion of New Mexico failed was that they couldn't keep enough mules to hauls supplies. Many of the Confederate Army's mules were lost to theft by Indians and locals, and death due to starvation and disease.

Mules were the backbone of both Confederate and Union Armies during the American Civil War. They pulled the supply wagons, the limbers and caisons for cannons, and the ambulances. One of the reasons that the Confederate Invasion of New Mexico failed was that they couldn't keep enough mules to hauls supplies. Many of the Confederate Army's mules were lost to theft by Indians and locals, and death due to starvation and disease.The night before the battle of Valverde, a Union spy named Paddy Graydon managed to spook the Confederate's mules, who stampeded down to the Rio Grande. There Union soldiers managed to round them up.

In Hardtack and Coffee: The Unwritten Story of Army Life, Civil War veteran John D. Billings shares the story of another mule stampede. During the night of Oct. 28, 1863, Union General John White Geary and Confederate General James Longstreet were fighting at Wauhatchie, Tennessee. The din or battle unnerved about two hundred mules, who stampeded into a body of Rebels commanded by Wade Hampton. The rebels thought they were being attacked by cavalry and fell back.

To commemorate this incident, one Union soldier penned a poem based on Tennyson's Charge of the Light Brigade.

Charge of the mule brigade

Half a mile, half a mile,

Half a mile onward,

Right through the Georgia troops

Broke the two hundred.

“Forward the Mule Brigade!”

“Charge for the Rebs!” they neighed.

Straight for the Georgia troops

Broke the two hundred.

“Forward the Mule Brigade!”

Was there a mule dismayed?

Not when the long ears felt

All their ropes sundered.

Theirs not to make reply,

Theirs not to reason why,

Theirs but to make Rebs fly.

On! to the Georgia troops

Broke the two hundred.

Mules to the right of them,

Mules to the left of them,

Mules behind them

Pawed, neighed, and thundered.

Breaking their own confines,

Breaking through Longstreet's lines

Into the Georgia troops,

Stormed the two hundred.

Wild all their eyes did glare,

Whisked all their tails in air

Scattering the chivalry there,

While all the world wondered.

Not a mule back bestraddled,

Yet how they all skedaddled--

Fled every Georgian,

Unsabred, unsaddled,

Scattered and sundered!

How they were routed there

By the two hundred!

Mules to the right of them,

Mules to the left of them,

Mules behind them

Pawed, neighed, and thundered;

Followed by hoof and head

Full many a hero fled,

Fain in the last ditch dead,

Back from an ass's jaw

All that was left of them,--

Left by the two hundred.

When can their glory fade?

Oh, the wild charge they made!

All the world wondered.

Honor the charge they made!

Honor the Mule Brigade,

Long-eared two hundred!

Mules are important in Jennifer Bohnhoff's newest historical novel, Valverde.

Published on April 27, 2017 00:00

April 23, 2017

Celebrating a Civil War Coffee Hero

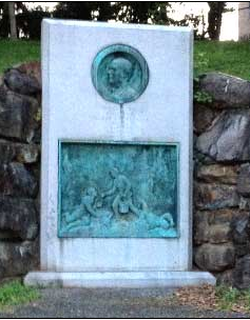

Maryland has one of the most unusual war monuments ever created. It doesn’t show a heroic charge or the valiant defense of a fortified position, but a soldier carrying a bucket and cup.

Maryland has one of the most unusual war monuments ever created. It doesn’t show a heroic charge or the valiant defense of a fortified position, but a soldier carrying a bucket and cup.The battle of Antietam was raging, and the boys from Ohio had been fighting since morning. Their spirits and their energy were waning. But then a 19-year-old private named William McKinley appeared, hauling a bucket of hot coffee. He ladled the steaming brew into the men’s tin cups. They gulped it down and resumed firing.

“It was like putting a new regiment in the fight,” their officer recalled.

When McKinley ran for president three decades late, people remembered this act of culinary heroism and voted him into office.

Coffee was such an important staple in the Union soldiers’ diet that the Army issued about 35 pounds of it to each soldier every year. They drank their hefty ration before marches and after marches, while on patrol, and, as McKinley proved, even during combat. Men ground the beans themselves, often by using their rifle butts to smash them in their tin cups, then brewed it using any water that was available to them. “Settling” the coffee, getting the grounds to sink to the bottom of the vats in which it was boiled, was so important that escaped slaves who were good at it found work as cooks in Union Army camps.

The Union blockade assured that most Confederates soldiers were not so lucky. The wide variety of attempts at creating substitutes speak to how desperately they wanted a cup of joe. Southerners tried making coffee substitutes from roasted corn, rye, chopped beets, sweet potatoes, chicory, and all sorts of other things. Although none of these brews were good, enjoying them was a source of patriotic pride. Gen. George Pickett, whose failed charge at Gettysburg is also a source of Southern pride, thanked his wife for the delicious “coffee” she had sent by saying that “no Mocha or Java ever tasted half so good as this rye-sweet-potato blend!”

Coffee may not have won the war nor earned McKinley his presidency, but it certainly was one of the small determining factors in both endeavors.

The soldiers in Jennifer Bohnhoff's newest book, Valverde, drink a lot of coffee. A recipe for Union Camp coffee and Confederate acorn coffee will be included in Salt Horse and Rio, a companion cookbook of Civil War recipes that will come out next month.

Published on April 23, 2017 00:00

April 13, 2017

Unusual responses

I've been writing a blog for about three years now. Most of the time I feel like I'm writing to myself. I don't get a lot of comments posted. When I do, I'm grateful. I appreciate it when someone learns something from my blog. I especially appreciate it when I'm told that one of my posts made a reader think about something they'd never thought of before.

But sometimes the comments that get posted really make me scratch my head and wonder who is reading my blog and why.

This week someone called topqualityessays posted a comment regarding my post Paddy Graydon Scheme to Stop the Confederacy that said "Thin air is the blog about the writer create this because of their books history to save their record on the line. First of all this a good decision for their online record saved books where we can search now on the system to develop our environment and the new technology of generation." Also this week, theconfidentopywriter commented on Americans in Paris, saying "Embarrassingly clumsy up to your post and sit tight for your next posts.Request Comcast has an extraordinary plan and great design. I have seen few pictures that have such incredible hues."

Huh?

When I first got comments like this, I got panicky, thinking they were some sort of cyber attack or spam. Now I wonder if someone in a third world country is using my blog to practice their English. I'm not sure if I'll ever know.

But sometimes the comments that get posted really make me scratch my head and wonder who is reading my blog and why.

This week someone called topqualityessays posted a comment regarding my post Paddy Graydon Scheme to Stop the Confederacy that said "Thin air is the blog about the writer create this because of their books history to save their record on the line. First of all this a good decision for their online record saved books where we can search now on the system to develop our environment and the new technology of generation." Also this week, theconfidentopywriter commented on Americans in Paris, saying "Embarrassingly clumsy up to your post and sit tight for your next posts.Request Comcast has an extraordinary plan and great design. I have seen few pictures that have such incredible hues."

Huh?

When I first got comments like this, I got panicky, thinking they were some sort of cyber attack or spam. Now I wonder if someone in a third world country is using my blog to practice their English. I'm not sure if I'll ever know.

Published on April 13, 2017 09:00

April 7, 2017

Potato Bread

The nineteenth century was a thriftier time than the present. Nothing was thrown away and everything, even the water that potatos were boiled in, was put to good use. Potato water was used to starch shirts, fertilize plants, thicken gravies, and supplement bread.

This recipe is adapted from one in James Beard's Beard on Bread, a cookbook which has seen a lot of use in my house over the years. Mr. Beard noted that this bread, with its moist and heavy texture, is reminiscent of breads from the nineteenth century. I don't know if Ms. McCoombs, the mother in The Bent Reed, my novel set during the Battle of Gettysburg, would have made this bread, but if she did, she would have started with a home-grown yeast and her loaves would have risen not in the refrigerator, but in the root cellar.

You can make up the dough on Saturday, and have a warm loaf all ready for Sunday supper.

Old Fashioned Potato Bread Dissolve 1 pkg active dry yeast and 1/2 cup sugar in 1 1/2 cups warm potato water. Let proof for about 5 minutes.

Add 3/4 cup of softened butter, 1 1/2 TBS salt, 2 eggs, and mix well.

Add 1 cup leftover mashed potatos and mix well.

Add up to 6 cups of flour. Stir it in, 1 cup at a time until you can no longer stir it, then turn out the dough onto the counter and knead it, adding flour whenever it becomes sticky. When the dough is smooth and elastic, place it in a very large mixing bowl or storage container that has been buttered and turn to coat all sides with the butter. Cover tightly and let rise in the refrigerator overnight. You want to use a very large container: this bread will more than double in size.

When you are ready to bake, remove from refrigerator and punch down. Knead on a floured counter for 5 minutes, then shape into two loaves. Place in well buttered bread pans and let rise until doubled in size. Because this bread was cooked, this may take up to 4 hours.

Bake 40-45 minutes in an oven set at 375. To test if they are done, turn a loaf out of its pan and rap the bottom. If you hear a hollow sound, the loaves are cooked through. Turn the oven off, turn the loaves out, and set them directly on the oven rack, where their crusts will crisp and brown. Cool completely before slicing.

This recipe is adapted from one in James Beard's Beard on Bread, a cookbook which has seen a lot of use in my house over the years. Mr. Beard noted that this bread, with its moist and heavy texture, is reminiscent of breads from the nineteenth century. I don't know if Ms. McCoombs, the mother in The Bent Reed, my novel set during the Battle of Gettysburg, would have made this bread, but if she did, she would have started with a home-grown yeast and her loaves would have risen not in the refrigerator, but in the root cellar.

You can make up the dough on Saturday, and have a warm loaf all ready for Sunday supper.

Old Fashioned Potato Bread Dissolve 1 pkg active dry yeast and 1/2 cup sugar in 1 1/2 cups warm potato water. Let proof for about 5 minutes.

Add 3/4 cup of softened butter, 1 1/2 TBS salt, 2 eggs, and mix well.

Add 1 cup leftover mashed potatos and mix well.

Add up to 6 cups of flour. Stir it in, 1 cup at a time until you can no longer stir it, then turn out the dough onto the counter and knead it, adding flour whenever it becomes sticky. When the dough is smooth and elastic, place it in a very large mixing bowl or storage container that has been buttered and turn to coat all sides with the butter. Cover tightly and let rise in the refrigerator overnight. You want to use a very large container: this bread will more than double in size.

When you are ready to bake, remove from refrigerator and punch down. Knead on a floured counter for 5 minutes, then shape into two loaves. Place in well buttered bread pans and let rise until doubled in size. Because this bread was cooked, this may take up to 4 hours.

Bake 40-45 minutes in an oven set at 375. To test if they are done, turn a loaf out of its pan and rap the bottom. If you hear a hollow sound, the loaves are cooked through. Turn the oven off, turn the loaves out, and set them directly on the oven rack, where their crusts will crisp and brown. Cool completely before slicing.

Published on April 07, 2017 11:00

April 6, 2017

A short history of yeast

Bread wasn’t always as easy to bake as it is now. Bread gets its airy structure by capturing gas bubbles in the elastic gluten of wheat. But how does one get those gas bubbles into the dough to begin with? The answer is leavening.

Throughout history, most households kept a crock of leavening in a warm corner of their kitchen. A small portion of this soft, dough-like substance was used to start each new lot of bread dough. The rest was replenished with water and flour and kept, sometimes for generations.

If a housewife neglected her leavening, it might cease to rise and turn into a vile smelling, pink slime. In that case, she threw it wout and either borrowed a bit of leavening from a neighor or began a new batch by setting out a crock of water mixed with flour and hoping that it would begin to produce foam. Some women knew that adding the husks of stone ground wheat would often hasten the process.

Leavening was used in bread and cake batters. Often, a dose of beer or wine dregs was also added.

What those housewives had been collecting and tending in their flour and water filled crocks were living organisms, wild yeasts that lived in the air, but settled into the crocks and multiplied, eating the starch and expelling carbon dioxide. Wild yeasts were also present in the wheat husks and beer and wine dregs.

It wasn’t until the late 1860s, when Louis Pasteur placed some leavening under a microscope, that anyone realized this.

Shortly after that, scientists began to isolate yeast in pure culture form. By the turn of the 20th century, they had created a way to dry it, thereby forcing it into dormancy. No longer did housewives need to replenish the leavening crock every few days!

Commercial baker’s yeast much like what you buy in red and yellow packets or glass jars in the supermarket soon followed.

Tommorow, look at my blog for a recipe for an old fashioned bread that uses new fangled commercial yeast.

Throughout history, most households kept a crock of leavening in a warm corner of their kitchen. A small portion of this soft, dough-like substance was used to start each new lot of bread dough. The rest was replenished with water and flour and kept, sometimes for generations.

If a housewife neglected her leavening, it might cease to rise and turn into a vile smelling, pink slime. In that case, she threw it wout and either borrowed a bit of leavening from a neighor or began a new batch by setting out a crock of water mixed with flour and hoping that it would begin to produce foam. Some women knew that adding the husks of stone ground wheat would often hasten the process.

Leavening was used in bread and cake batters. Often, a dose of beer or wine dregs was also added.

What those housewives had been collecting and tending in their flour and water filled crocks were living organisms, wild yeasts that lived in the air, but settled into the crocks and multiplied, eating the starch and expelling carbon dioxide. Wild yeasts were also present in the wheat husks and beer and wine dregs.

It wasn’t until the late 1860s, when Louis Pasteur placed some leavening under a microscope, that anyone realized this.

Shortly after that, scientists began to isolate yeast in pure culture form. By the turn of the 20th century, they had created a way to dry it, thereby forcing it into dormancy. No longer did housewives need to replenish the leavening crock every few days!

Commercial baker’s yeast much like what you buy in red and yellow packets or glass jars in the supermarket soon followed.

Tommorow, look at my blog for a recipe for an old fashioned bread that uses new fangled commercial yeast.

Published on April 06, 2017 08:30

March 29, 2017

Running out of Time to kickstart a dream

My Kickstarter for Valverde ends on Tuesday. If you were interested in participating, you're running out of time.

My Kickstarter for Valverde ends on Tuesday. If you were interested in participating, you're running out of time.If you've never heard of a kickstarter before (except for those on motorcycles), welcome to the club. I'd never heard of one either until my hip, millennial son explained to me that they are how modern-day entrepreneurs acquire the capital for beginning, or kickstarting, new projects. Unlike some crowdfunding, like GoFundMe, on which people just ask for money and hope someone gives it to them, or DonorsChoose, where teachers ask donors to give money to buy supplies for their classes, people on Kickstarter promise their backers something in return for their money.

What I've offered is my latest book, Valverde, at a significant discount over what it will sell for when it comes out later in April.

I've offered some additional rewards, too. I'll be creating a book of Civil War recipes that some of my backers are going to get. It won't be available anywhere else except through this Kickstarter for at least the foreseeable future. I'll also be working on a teacher's guide that will follow Common Core Standards.

But supporting a Kickstarter doesn't have to be about good deals. It can also be about good deeds. My philanthropic friends and supporters can buys single books or even whole classroom sets and teachers guides for classrooms in low income areas.

What am I going to do with the money I get from this Kickstarter? First, I'm hiring a professional to make a truly attractive cover for Valverde. Second, I'll be marketing this book to educators throughout the state. If I earn enough, I'll create a large print edition so that the elderly and those with vision disabilities can read Valverde. If I earn even more, an audio book will come out.

Expanding the reach of my readership and providing large print and audio books are big dreams for me. I am grateful for the son who helped me find a way to make these dreams become a reality. It's exciting to see who has chosen to back my Kickstarter. Some are old friends and family members, but many are people I've yet to meet. It's exciting to attract new readers to my circle.

Sound intriguing? Click here to see more about my Kickstarter. But don't wait too long. This campaign closes on Tuesday, April 4.

Published on March 29, 2017 20:24