Jennifer Bohnhoff's Blog, page 37

January 30, 2018

Writing in thin air

The view from my living room on an unusual foggy morning. I began writing in 1992. By 2014 I had over a dozen manuscripts and a thousand rejections to show for my work. Some editors and agents said they loved the characters but not the plots. Others loved the plots but not the characters. Some suggested that historical fiction wasn't selling, and if I would add some supernatural elements - a ghost, or time travel, or perhaps a werewolf, then they would reconsider by submissions.

The view from my living room on an unusual foggy morning. I began writing in 1992. By 2014 I had over a dozen manuscripts and a thousand rejections to show for my work. Some editors and agents said they loved the characters but not the plots. Others loved the plots but not the characters. Some suggested that historical fiction wasn't selling, and if I would add some supernatural elements - a ghost, or time travel, or perhaps a werewolf, then they would reconsider by submissions.In 2014 I decided that the definition of insanity - doing the same thing

and expecting a different result - was probably right. It was time for me to do something different.

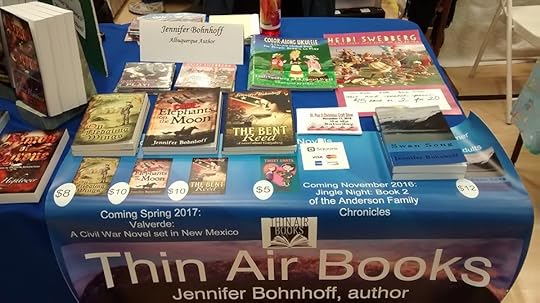

I began self publishing my books in 2014. That first year I released Code: Elephants on the Moon, a midgrade novel set in Normandy just before D-Day, and The Bent Reed, a midgrade novel featuring a family living in Gettysburg at the time of the Civil War battle. 2015 saw On Fledgling Wings, a midgrade coming of age story set in 13th century England, added to my list.

But self publishing is difficult. Not only did I have to write my books, I had to edit and format them, and advertise and market them. I quickly realized that it's easier to write a book than sell it. When a group of my author friends said that they were banding together to form a publishing house because it was easier to market and sell books that had a publishing house associated with them, I decided to try it myself, and Thin Air Books was born.

Thin Air Books now has 7 books on its list, and still features just one author: me. Has it helped sales? It's hard to know, but I doubt it. No independent book sellers have offered to put my books on their shelves because they come from a publishing house, and no editors or agents have decided that I'm a better prospect because of my self publishing and marketing efforts. I continue to slog along, happy to be producing and sharing my work with the world, although my sales are almost as thin as the mountain air I breathe.

Thin Air Books now has 7 books on its list, and still features just one author: me. Has it helped sales? It's hard to know, but I doubt it. No independent book sellers have offered to put my books on their shelves because they come from a publishing house, and no editors or agents have decided that I'm a better prospect because of my self publishing and marketing efforts. I continue to slog along, happy to be producing and sharing my work with the world, although my sales are almost as thin as the mountain air I breathe.

Published on January 30, 2018 07:30

January 23, 2018

Bohnhoff's Birthday Book Bonanza!

Between Christmas and my early January birthday, this past month has been quite the book bonanza for me!

I love books. Most of the time, I borrow what I read from the library. This year, I borrowed a few titles that I loved so much that I was tempted to "lose" them and pay the fines just to keep them. Luckily for me, my dear family came through for me,preventing me from entering a life of crime.

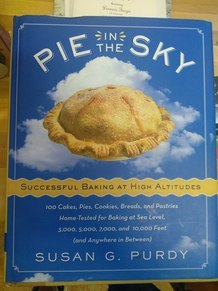

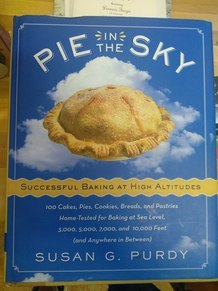

Susan G. Purdy's Pie in the Sky: Successful Baking at High Altitudes is an absolute must for those of us who live up where the air is thin, but it is good for you flat-landers as well. Each of Purdy's recipes features adaptations for altitudes between sea level and 10,000 feet, plus an analysis of why she changes what she changes. I tend to be one of those cooks who uses a teaspoon to measure anything between 1/4 and 1 tsp and found her meticulousness daunting, but so far I've used three recipes and all have turned out quite well.

Susan G. Purdy's Pie in the Sky: Successful Baking at High Altitudes is an absolute must for those of us who live up where the air is thin, but it is good for you flat-landers as well. Each of Purdy's recipes features adaptations for altitudes between sea level and 10,000 feet, plus an analysis of why she changes what she changes. I tend to be one of those cooks who uses a teaspoon to measure anything between 1/4 and 1 tsp and found her meticulousness daunting, but so far I've used three recipes and all have turned out quite well.

Combat-Ready Kitchen is a fascinating look at how the U.S. military's quest for nutritious, shelf-stable, readily portable food has driven the eating habits of normal Americans. I never knew before reading this that the rise of aluminum foil in America's kitchens is a bi product of the enormous metal surplus after America stopped producing bombers, or that macaroni and cheese and Cheetos were both created to use up surplus cheese powder. There's a lot of food for thought in this book,

particularly when Saucedo discusses the quest for bread that stayed fresh, and how that might have affected our nutrition and digestion.

particularly when Saucedo discusses the quest for bread that stayed fresh, and how that might have affected our nutrition and digestion.

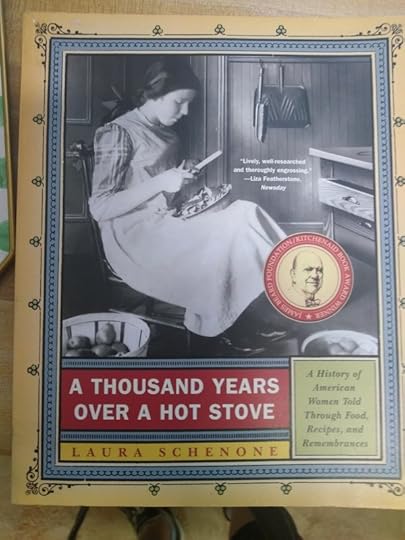

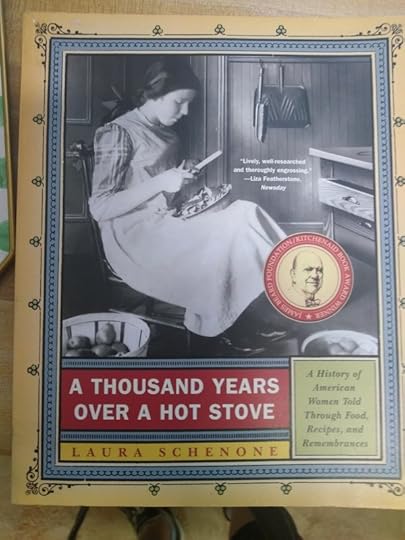

A Thousand Years over a Hot Stove is another book so filled with interesting tidbits that I checked it out of the library numerous times before putting it on my wish list. Laura Schenone provides a history of American women that also provides a pithy look into the commercialization of food in Amer-

ica. It's interesting to read how, for the sake of convenience, women gave up more and more of their kitchen work to big companies, then took it back when natural became fashionable again.

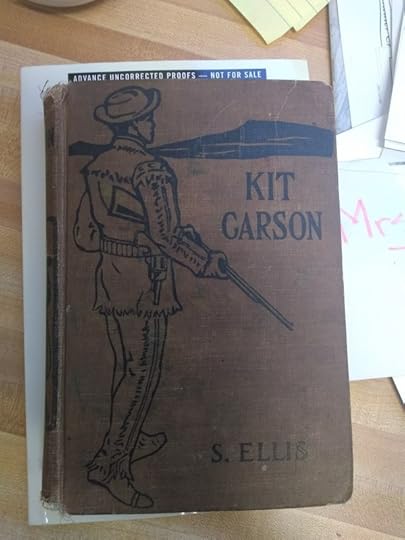

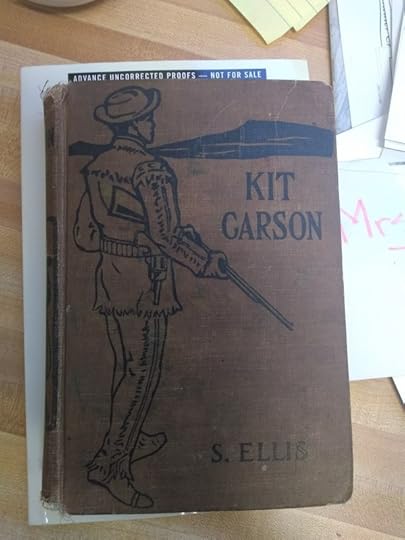

But the book that really made my heart leap for for wasn't on my wish list. One of my sons (or his wife) found this 1889 edition of a biography of Kit Carson and gave it to me. It is not one of those dime-store Westerns that seeks to make him into an American icon, but an

honest and fairly accurate work, and I look forward to using it the next time I get to teach New Mexico history.

honest and fairly accurate work, and I look forward to using it the next time I get to teach New Mexico history.

This has been a very good month for me, as far as books go. How about you? Did you get any treasures over the holidays? I'd love to hear what new tomes are gracing your shelves.

I love books. Most of the time, I borrow what I read from the library. This year, I borrowed a few titles that I loved so much that I was tempted to "lose" them and pay the fines just to keep them. Luckily for me, my dear family came through for me,preventing me from entering a life of crime.

Susan G. Purdy's Pie in the Sky: Successful Baking at High Altitudes is an absolute must for those of us who live up where the air is thin, but it is good for you flat-landers as well. Each of Purdy's recipes features adaptations for altitudes between sea level and 10,000 feet, plus an analysis of why she changes what she changes. I tend to be one of those cooks who uses a teaspoon to measure anything between 1/4 and 1 tsp and found her meticulousness daunting, but so far I've used three recipes and all have turned out quite well.

Susan G. Purdy's Pie in the Sky: Successful Baking at High Altitudes is an absolute must for those of us who live up where the air is thin, but it is good for you flat-landers as well. Each of Purdy's recipes features adaptations for altitudes between sea level and 10,000 feet, plus an analysis of why she changes what she changes. I tend to be one of those cooks who uses a teaspoon to measure anything between 1/4 and 1 tsp and found her meticulousness daunting, but so far I've used three recipes and all have turned out quite well.Combat-Ready Kitchen is a fascinating look at how the U.S. military's quest for nutritious, shelf-stable, readily portable food has driven the eating habits of normal Americans. I never knew before reading this that the rise of aluminum foil in America's kitchens is a bi product of the enormous metal surplus after America stopped producing bombers, or that macaroni and cheese and Cheetos were both created to use up surplus cheese powder. There's a lot of food for thought in this book,

particularly when Saucedo discusses the quest for bread that stayed fresh, and how that might have affected our nutrition and digestion.

particularly when Saucedo discusses the quest for bread that stayed fresh, and how that might have affected our nutrition and digestion.A Thousand Years over a Hot Stove is another book so filled with interesting tidbits that I checked it out of the library numerous times before putting it on my wish list. Laura Schenone provides a history of American women that also provides a pithy look into the commercialization of food in Amer-

ica. It's interesting to read how, for the sake of convenience, women gave up more and more of their kitchen work to big companies, then took it back when natural became fashionable again.

But the book that really made my heart leap for for wasn't on my wish list. One of my sons (or his wife) found this 1889 edition of a biography of Kit Carson and gave it to me. It is not one of those dime-store Westerns that seeks to make him into an American icon, but an

honest and fairly accurate work, and I look forward to using it the next time I get to teach New Mexico history.

honest and fairly accurate work, and I look forward to using it the next time I get to teach New Mexico history.This has been a very good month for me, as far as books go. How about you? Did you get any treasures over the holidays? I'd love to hear what new tomes are gracing your shelves.

Published on January 23, 2018 06:00

January 16, 2018

Some of My Favorite Gifts, Part 1

Last August, as I began work at a new school, one of my former students came to visit, and she brought me this orchid.

Alexa is one of my most successful former students. She came from an immigrant family that spoke limited English, but she has a great amount of personal drive. She's worked hard, and is now in a joint bachelors/MD program.

I taught Alexa when she was in 6th grade. She continued to keep in touch with me, returning throughout

her high school years to let me know how she was doing, and occasionally to get advice on papers she was writing. I had the honor of writing recommendations for her a few times. But I can't claim any credit for her successes. She's worked hard and earned everything she's received in life.

her high school years to let me know how she was doing, and occasionally to get advice on papers she was writing. I had the honor of writing recommendations for her a few times. But I can't claim any credit for her successes. She's worked hard and earned everything she's received in life.

What makes this orchid so special is that she was willing to drive way out in to the country to give it to me. That was a big effort, and I appreciated it. The orchid she left me is a continual reminder that what I do is important. Not many of my students will be like Alexa, but there are plenty who are listening to what I say, and will take what little I can give and grow it into a good career and a good life. Even though the flowers have faded and grown papery, it continues to remind me that students who have a strong foundation can grow into something beautiful and lasting.

Thank you, Alexa, for the reminder, and for the inspiration of your life.

Alexa is one of my most successful former students. She came from an immigrant family that spoke limited English, but she has a great amount of personal drive. She's worked hard, and is now in a joint bachelors/MD program.

I taught Alexa when she was in 6th grade. She continued to keep in touch with me, returning throughout

her high school years to let me know how she was doing, and occasionally to get advice on papers she was writing. I had the honor of writing recommendations for her a few times. But I can't claim any credit for her successes. She's worked hard and earned everything she's received in life.

her high school years to let me know how she was doing, and occasionally to get advice on papers she was writing. I had the honor of writing recommendations for her a few times. But I can't claim any credit for her successes. She's worked hard and earned everything she's received in life.What makes this orchid so special is that she was willing to drive way out in to the country to give it to me. That was a big effort, and I appreciated it. The orchid she left me is a continual reminder that what I do is important. Not many of my students will be like Alexa, but there are plenty who are listening to what I say, and will take what little I can give and grow it into a good career and a good life. Even though the flowers have faded and grown papery, it continues to remind me that students who have a strong foundation can grow into something beautiful and lasting.

Thank you, Alexa, for the reminder, and for the inspiration of your life.

Published on January 16, 2018 07:00

January 1, 2018

Turning a New Place Mat

Some people turn over a new leaf at the start of the new year. I turn over the place mats.

I have a friend named Jessica Bonzen who is a quilter. She sells her beautiful handiwork at some of the same craft shows where I sell my books.

Sorry for the fuzzy image. A few years ago I commissioned her to make some place mats just for me. Jessica created sets of four, specially shaped to fit the round table in the corner of my living room closest to the big picture window. When my husband and I sit there, it's like sitting on the edge of the world, looking out over God's glory.

Sorry for the fuzzy image. A few years ago I commissioned her to make some place mats just for me. Jessica created sets of four, specially shaped to fit the round table in the corner of my living room closest to the big picture window. When my husband and I sit there, it's like sitting on the edge of the world, looking out over God's glory.

One of the sets Jessica made me features red and white poinsettias. I wish the picture was clearer so that you could see how beautiful it is, but my camera and I seem to not be on speaking terms this new year.

Besides the beautiful fabrics and quality workmanship Jessica puts into her products, one of the features I love the most is that her place mats are double-sided. Turn them over, and discover a new design! My Christmas place mats reverse into a wintry snow scene with cardinals and white aspen trees.

Besides the beautiful fabrics and quality workmanship Jessica puts into her products, one of the features I love the most is that her place mats are double-sided. Turn them over, and discover a new design! My Christmas place mats reverse into a wintry snow scene with cardinals and white aspen trees.

I'm ringing in the new year by turning over my place mats. Good bye, Christmas. You were wonderful, but it's time for a new year.

However you plan to commemorate the beginning of 2018, I wish you health and happiness.

I have a friend named Jessica Bonzen who is a quilter. She sells her beautiful handiwork at some of the same craft shows where I sell my books.

Sorry for the fuzzy image. A few years ago I commissioned her to make some place mats just for me. Jessica created sets of four, specially shaped to fit the round table in the corner of my living room closest to the big picture window. When my husband and I sit there, it's like sitting on the edge of the world, looking out over God's glory.

Sorry for the fuzzy image. A few years ago I commissioned her to make some place mats just for me. Jessica created sets of four, specially shaped to fit the round table in the corner of my living room closest to the big picture window. When my husband and I sit there, it's like sitting on the edge of the world, looking out over God's glory.One of the sets Jessica made me features red and white poinsettias. I wish the picture was clearer so that you could see how beautiful it is, but my camera and I seem to not be on speaking terms this new year.

Besides the beautiful fabrics and quality workmanship Jessica puts into her products, one of the features I love the most is that her place mats are double-sided. Turn them over, and discover a new design! My Christmas place mats reverse into a wintry snow scene with cardinals and white aspen trees.

Besides the beautiful fabrics and quality workmanship Jessica puts into her products, one of the features I love the most is that her place mats are double-sided. Turn them over, and discover a new design! My Christmas place mats reverse into a wintry snow scene with cardinals and white aspen trees.I'm ringing in the new year by turning over my place mats. Good bye, Christmas. You were wonderful, but it's time for a new year.

However you plan to commemorate the beginning of 2018, I wish you health and happiness.

Published on January 01, 2018 09:05

November 30, 2017

Great Christmas Reads for Middle Grade Readers

Everyone loves a good Christmas read. Here's a short list of some of the best for middle grade readers.

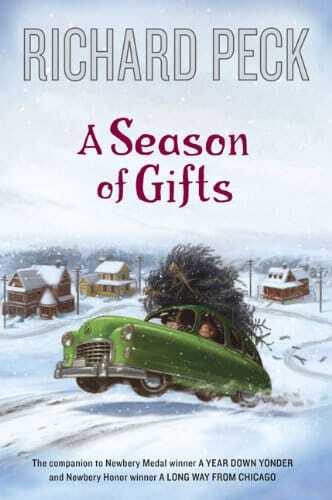

Everyone loves a good Christmas read. Here's a short list of some of the best for middle grade readers.The main character in Richard Peck's A Season of Gifts is twelve year old Bob, the son of a preacher and new kid in town, but the heart of this sequel to the Newbery Award winning A Long Way to Chicago and the Newbery Honor book A Year Down Yonder is the eccentric Mrs. Dowdel, an elderly, grumpy, gun-wielding woman who claims to have no interest in neighboring or in church, but has special gifts to share with both her neighbors and their new church.

Set in 1958, this heartwarming tale will remind you a bit of the innocence of the 1983 movie, A Christmas Story,

Children of Christmas has six stories by the Newbery Honor winning author Cynthia Rylant that are perfect for reading aloud, if you can control your emotions. Like Hans Christian Andersen's Little Match Girl, these poignant stories of lonely and desperate people are are guaranteed to make you cry, yet her exquisite writing also conveys the special joy of the season, Stories include one of a lonely man who raises Christmas trees, a stray cat who finds shelter, an elderly widower missing his wife, an Appalachian boy who waits each year for a train bringing gifts, and more.

How was Christmas celebrated in 13th century England? Nathaniel Marshall, the son of a knight, spends Christmas at Glastonbury Abbey in my novel On Fledgling Wings. Nathaniel waits to see if the legend that the animals will speak at midnight is true, wonders if the saints looking down on him from the church friezes are watching him, and gets to serve the roast boar at the Christmas day banquet.

How was Christmas celebrated in 13th century England? Nathaniel Marshall, the son of a knight, spends Christmas at Glastonbury Abbey in my novel On Fledgling Wings. Nathaniel waits to see if the legend that the animals will speak at midnight is true, wonders if the saints looking down on him from the church friezes are watching him, and gets to serve the roast boar at the Christmas day banquet.But all too soon the peace of the season will pass, and Nathaniel will be embroiled in a battle for power at the manor house.

From Anna, by Jean Little, begins in Germany in 1933. Anna Solden is the youngest and clumsiest in a large family that treats her like the incompetent baby. After they immigrate to America to escape the worsening political scene, the family discovers that Anna can barely see. A new pair of glasses and a special class for the visually impaired helps her blossom into a proficient and confident child. The climax features a Christmas during the depression that might have been dismal had it not been for the pluck and cheerfulness of the family, and at which Anna comes into her own and proves to her family - and herself - that she can do anything she sets her mind to.

From Anna, by Jean Little, begins in Germany in 1933. Anna Solden is the youngest and clumsiest in a large family that treats her like the incompetent baby. After they immigrate to America to escape the worsening political scene, the family discovers that Anna can barely see. A new pair of glasses and a special class for the visually impaired helps her blossom into a proficient and confident child. The climax features a Christmas during the depression that might have been dismal had it not been for the pluck and cheerfulness of the family, and at which Anna comes into her own and proves to her family - and herself - that she can do anything she sets her mind to. And finally, new this Christmas, Jingle Night, the second in The Anderson Chronicles, my series of contemporary novels for middle grade readers. Hector Anderson just can't get in the holiday spirit. He's loaded down with homework, and too broke to buy presents for his family or his heart throb, Sandy. Meanwhile, sister Chloe wants to be the angel of death in the holiday play, a role as silent as younger brother Calvin's been since the loss of his hand puppet, Mr. Buttons.

And finally, new this Christmas, Jingle Night, the second in The Anderson Chronicles, my series of contemporary novels for middle grade readers. Hector Anderson just can't get in the holiday spirit. He's loaded down with homework, and too broke to buy presents for his family or his heart throb, Sandy. Meanwhile, sister Chloe wants to be the angel of death in the holiday play, a role as silent as younger brother Calvin's been since the loss of his hand puppet, Mr. Buttons.As if reenacting the game of Clue, an old inn that's usually quiet at Christmastime fills with a hodge-podge of quirky guests, all of whom seem to be searching for the answer to a different mystery, which they share in a series of fireside stories. Twelve-year-old Milo, the innkeepers' adopted son, turns into the sleuth who must solve them all. This story is part mystery, part folk tale, part ghost story, with enough twists and turns to keep even the most finicky reader entertained.

Little brother Stevie can only remember four words from the song he must sing at the Little Leapers Preschool Pageant, but he uses his slingshot to spread Christmas cheer, which Hec's perfectionist Father doesn't appreciate.

Little brother Stevie can only remember four words from the song he must sing at the Little Leapers Preschool Pageant, but he uses his slingshot to spread Christmas cheer, which Hec's perfectionist Father doesn't appreciate.Hec is determined to solve his problems, and while Mom tries to eggnog and carol everyone into the Christmas spirit, he and his best buddy Eddie embark on a madcap plan to solve Hec's Christmas dilemma.

Here's wishing you a Merry Christmas and happy reading this holiday season.

Published on November 30, 2017 00:00

November 16, 2017

Garbage Soup

When Matt, my oldest son, was in 5th grade, his class held a "Pioneer Day." Students were to bring in homemade soups and breads, and supplies for simple crafts such as corn husk dolls. While December storms raged without (usually a bit of literary license in Albuquerque) they were going to hunker down in a classroom lit by kerosene lamp and candlelight, learn their lessons on chalk boards with chalk, play simple, non-electronic games, and live like Laura Ingalls Wilder had in Little House on the Prairie.

I decided that if my son was going to eat like a pioneer, he needed to learn how pioneers cooked. We would practice pioneer thriftiness in our own kitchen.

Very few people practice the kind of thriftiness that our foremothers practiced. We don't have to. We have supermarkets stuffed with everything we need. Most people I know start a soup pot with a can of broth. Mrs. Ingalls didn't have a supermarket at her disposal. She made her broth from scratch, usually using the tag ends of vegetables and leftover bones. I told Matt that we were going to make broth the pioneer way.

We started by placing the carcass of the Thanksgiving turkey into a large pot. Then we peeled carrots and threw the peelings and the tops onto the bones. We threw in the leafy tops and thick bottoms of a head of celery and the ends of an onion. We sliced the tops and bottoms off a tomato and threw them into the pot, too. We threw in some herbs and seasonings, covered it all with water, and left it to simmer for the better part of a day. By the time we were ready to strain the broth and pick the last bits of meat off the bones, the whole house smelled wonderful.

Matt proudly carried in his crockpot of soup of Pioneer Day, and he was so enthusiastic about what he'd learned that the teacher asked him to share the experience with the class. Not everyone was impressed. As he explained all the tag-ends that went into the pot, one mother's face expressed more and more horror. Finally, she walked over to me and whispered in my ear.

"Don't tell me your son made this soup out of garbage," she said. When I told her that peelings and ends were not garbage, and that yes, Matt had done exactly what he'd said, her expression moved from horror to revulsion. She quickly told her daughter to put down her spoon and pour the soup out. She then announced that her soup had been made the right way: it had come from a can. I had to chuckle. Didn't she know that the company who canned that soup had gone through the same process as Matt had to make their soup?

We continue to make what's become known as garbage soup every year after Thanksgiving, and it has never failed to satisfy our bellies and our. If you've never made it, perhaps this is the year to try a little bit of pioneer thriftiness.

General Directions for Garbage Soup

These are just general directions. Because garbage soup is made thriftily from whatever you have lying about, it will be different every time.

In the weeks leading up to soup making, save any vegetable odds and ends in a zip lock bag or plastic storage container in the freezer. Have three green beans left over from dinner? Into the bag they go! A spoonful of corn or peas, or a slice of onion? They are freezer bound!

On the day of soup making, peel some carrots and turn them into sticks or rounds. Package them and put them in the fridge for later eating, but add the carrot tops and peelings to the soup pot. Cut the bottom and the leafy ends off the celery and throw them into the soup pot, too. Cut the celery into nice sticks and put them in the fridge for later snacking. Slice the top and bottom off an onion and throw them into the pot. Dice or slice the onion and put in the fridge. Throw in whatever other odds and ends you might have lying around in the fridge - tomatoes on the verge of going mushy, for instance.

Add the leftover bones from a turkey (or chicken, or beef roast) into the pot. Add 5 black peppercorns, a bay leaf, and a teaspoon of salt, then cover everything with water. Bring slowly to a boil and simmer, uncovered, for several hours. (You can also throw all this into a crockpot and let it cook all day that way, too.)

When the stock tastes like stock, strain it through a colander into a large bowl. Press down on the celery and carrots to get all their juices out. Pick off any remaining meat and store it in the fridge. If your bowl has a lid, cover it and put it in the fridge. If it doesn't, transfer the stock to other containers.

When your stock is cool (I do this the next day) you can skim off any fat with a spoon and throw it away. At this point you can divide it up and store in the freezer for later use, or proceed to make garbage soup.

To make soup, put diced onion, carrots, and celery in a saucepan with a little fat (oil, butter, or some of the fat you just skimmed off the stock.) and cook until soft and a little brown. Pour some or all of your stock back into a saucepan. Add anything else you want. A diced up potato or two, or a handful of barley are good. When the vegetables are cooked, add any precooked things, like that bag of extra beans and corn you have in the freezer, or some leftover cooked rice, plus the meat you picked off the bones. Adjust seasonings by adding a little salt or a splash of worcestershire sauce. Enjoy!

I decided that if my son was going to eat like a pioneer, he needed to learn how pioneers cooked. We would practice pioneer thriftiness in our own kitchen.

Very few people practice the kind of thriftiness that our foremothers practiced. We don't have to. We have supermarkets stuffed with everything we need. Most people I know start a soup pot with a can of broth. Mrs. Ingalls didn't have a supermarket at her disposal. She made her broth from scratch, usually using the tag ends of vegetables and leftover bones. I told Matt that we were going to make broth the pioneer way.

We started by placing the carcass of the Thanksgiving turkey into a large pot. Then we peeled carrots and threw the peelings and the tops onto the bones. We threw in the leafy tops and thick bottoms of a head of celery and the ends of an onion. We sliced the tops and bottoms off a tomato and threw them into the pot, too. We threw in some herbs and seasonings, covered it all with water, and left it to simmer for the better part of a day. By the time we were ready to strain the broth and pick the last bits of meat off the bones, the whole house smelled wonderful.

Matt proudly carried in his crockpot of soup of Pioneer Day, and he was so enthusiastic about what he'd learned that the teacher asked him to share the experience with the class. Not everyone was impressed. As he explained all the tag-ends that went into the pot, one mother's face expressed more and more horror. Finally, she walked over to me and whispered in my ear.

"Don't tell me your son made this soup out of garbage," she said. When I told her that peelings and ends were not garbage, and that yes, Matt had done exactly what he'd said, her expression moved from horror to revulsion. She quickly told her daughter to put down her spoon and pour the soup out. She then announced that her soup had been made the right way: it had come from a can. I had to chuckle. Didn't she know that the company who canned that soup had gone through the same process as Matt had to make their soup?

We continue to make what's become known as garbage soup every year after Thanksgiving, and it has never failed to satisfy our bellies and our. If you've never made it, perhaps this is the year to try a little bit of pioneer thriftiness.

General Directions for Garbage Soup

These are just general directions. Because garbage soup is made thriftily from whatever you have lying about, it will be different every time.

In the weeks leading up to soup making, save any vegetable odds and ends in a zip lock bag or plastic storage container in the freezer. Have three green beans left over from dinner? Into the bag they go! A spoonful of corn or peas, or a slice of onion? They are freezer bound!

On the day of soup making, peel some carrots and turn them into sticks or rounds. Package them and put them in the fridge for later eating, but add the carrot tops and peelings to the soup pot. Cut the bottom and the leafy ends off the celery and throw them into the soup pot, too. Cut the celery into nice sticks and put them in the fridge for later snacking. Slice the top and bottom off an onion and throw them into the pot. Dice or slice the onion and put in the fridge. Throw in whatever other odds and ends you might have lying around in the fridge - tomatoes on the verge of going mushy, for instance.

Add the leftover bones from a turkey (or chicken, or beef roast) into the pot. Add 5 black peppercorns, a bay leaf, and a teaspoon of salt, then cover everything with water. Bring slowly to a boil and simmer, uncovered, for several hours. (You can also throw all this into a crockpot and let it cook all day that way, too.)

When the stock tastes like stock, strain it through a colander into a large bowl. Press down on the celery and carrots to get all their juices out. Pick off any remaining meat and store it in the fridge. If your bowl has a lid, cover it and put it in the fridge. If it doesn't, transfer the stock to other containers.

When your stock is cool (I do this the next day) you can skim off any fat with a spoon and throw it away. At this point you can divide it up and store in the freezer for later use, or proceed to make garbage soup.

To make soup, put diced onion, carrots, and celery in a saucepan with a little fat (oil, butter, or some of the fat you just skimmed off the stock.) and cook until soft and a little brown. Pour some or all of your stock back into a saucepan. Add anything else you want. A diced up potato or two, or a handful of barley are good. When the vegetables are cooked, add any precooked things, like that bag of extra beans and corn you have in the freezer, or some leftover cooked rice, plus the meat you picked off the bones. Adjust seasonings by adding a little salt or a splash of worcestershire sauce. Enjoy!

Published on November 16, 2017 00:00

August 10, 2017

Mistaken Identities in Middle Grade Fiction

Most middle school readers wonder if they were adopted. Some actually revel in it: who are these people, and why can’t they understand me? Clearly my own people are elsewhere. Middle grade readers are going through so many emotional, physical and psychological changes that it’s not surprising that they are drawn to books about other children who don’t know who they are. Here are a few suggested books with this theme.

Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist is the classic novel of mistaken identity. Originally published in monthly installments between 1837 and 1839, it tells the story of an orphan born in a workhouse in 1830s England. Oliver leaves the workhouse when he is nine years old and apprenticed to an undertaker, but runs away and finds himself in the company of a troop of pickpockets. Through a series of interwoven circumstances, the kind that only Dickens could have created, Oliver’s identity is eventually revealed, and the orphan boy goes from rags to riches and takes his rightful place in the kind of generous and loving family that every middle school child wishes he had.

Jip, His Story

written in 1996 by the Newbery winning American novelist Katherine Paterson, focuses on another orphan, this time a 12-year-old. Set on a poor farm in Vermont during the 1850s, it tells the story of a baby who supposedly fell of a cart and was never retrieved. He is called Jip because his dark skin color made people believe he was a gypsy. Despite the hard work and difficult conditions, Jip gets along well with the other workers on the farm, many of whom are mentally ill, and he enjoys working with the farm animals. But when a man shows up and begins asking questions about Jip’s background, it becomes clear that Jip is no gypsy, and his real identity puts him in grave danger.

Jip, His Story

written in 1996 by the Newbery winning American novelist Katherine Paterson, focuses on another orphan, this time a 12-year-old. Set on a poor farm in Vermont during the 1850s, it tells the story of a baby who supposedly fell of a cart and was never retrieved. He is called Jip because his dark skin color made people believe he was a gypsy. Despite the hard work and difficult conditions, Jip gets along well with the other workers on the farm, many of whom are mentally ill, and he enjoys working with the farm animals. But when a man shows up and begins asking questions about Jip’s background, it becomes clear that Jip is no gypsy, and his real identity puts him in grave danger.

The main character of my historical novel

Code: Elephants on the Moon

may not be an orphan, but she still doesn’t know who she is. Eponine Lambaol thinks she is the only red head in a town filled with brown-haired people because she is Breton living in a tiny village in Normandy, France. It is spring of 1944 and there are many things that Eponine doesn’t understand. Where is her father? Who is the mysterious cousin who has come to live with her and her mother? When Eponine finds her mother and cousin listening to strange announcements on a forbidden radio, she realizes that nothing she’s believed about herself is true.

The main character of my historical novel

Code: Elephants on the Moon

may not be an orphan, but she still doesn’t know who she is. Eponine Lambaol thinks she is the only red head in a town filled with brown-haired people because she is Breton living in a tiny village in Normandy, France. It is spring of 1944 and there are many things that Eponine doesn’t understand. Where is her father? Who is the mysterious cousin who has come to live with her and her mother? When Eponine finds her mother and cousin listening to strange announcements on a forbidden radio, she realizes that nothing she’s believed about herself is true.

Jennifer Bohnhoff teaches 7th grade social studies in Albuquerque, New Mexico. She is the author of several works of middle grade historical fiction. Her most recent book, Valverde, is set in New Mexico during the Civil War

Jennifer Bohnhoff teaches 7th grade social studies in Albuquerque, New Mexico. She is the author of several works of middle grade historical fiction. Her most recent book, Valverde, is set in New Mexico during the Civil War

Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist is the classic novel of mistaken identity. Originally published in monthly installments between 1837 and 1839, it tells the story of an orphan born in a workhouse in 1830s England. Oliver leaves the workhouse when he is nine years old and apprenticed to an undertaker, but runs away and finds himself in the company of a troop of pickpockets. Through a series of interwoven circumstances, the kind that only Dickens could have created, Oliver’s identity is eventually revealed, and the orphan boy goes from rags to riches and takes his rightful place in the kind of generous and loving family that every middle school child wishes he had.

Jip, His Story

written in 1996 by the Newbery winning American novelist Katherine Paterson, focuses on another orphan, this time a 12-year-old. Set on a poor farm in Vermont during the 1850s, it tells the story of a baby who supposedly fell of a cart and was never retrieved. He is called Jip because his dark skin color made people believe he was a gypsy. Despite the hard work and difficult conditions, Jip gets along well with the other workers on the farm, many of whom are mentally ill, and he enjoys working with the farm animals. But when a man shows up and begins asking questions about Jip’s background, it becomes clear that Jip is no gypsy, and his real identity puts him in grave danger.

Jip, His Story

written in 1996 by the Newbery winning American novelist Katherine Paterson, focuses on another orphan, this time a 12-year-old. Set on a poor farm in Vermont during the 1850s, it tells the story of a baby who supposedly fell of a cart and was never retrieved. He is called Jip because his dark skin color made people believe he was a gypsy. Despite the hard work and difficult conditions, Jip gets along well with the other workers on the farm, many of whom are mentally ill, and he enjoys working with the farm animals. But when a man shows up and begins asking questions about Jip’s background, it becomes clear that Jip is no gypsy, and his real identity puts him in grave danger. The main character of my historical novel

Code: Elephants on the Moon

may not be an orphan, but she still doesn’t know who she is. Eponine Lambaol thinks she is the only red head in a town filled with brown-haired people because she is Breton living in a tiny village in Normandy, France. It is spring of 1944 and there are many things that Eponine doesn’t understand. Where is her father? Who is the mysterious cousin who has come to live with her and her mother? When Eponine finds her mother and cousin listening to strange announcements on a forbidden radio, she realizes that nothing she’s believed about herself is true.

The main character of my historical novel

Code: Elephants on the Moon

may not be an orphan, but she still doesn’t know who she is. Eponine Lambaol thinks she is the only red head in a town filled with brown-haired people because she is Breton living in a tiny village in Normandy, France. It is spring of 1944 and there are many things that Eponine doesn’t understand. Where is her father? Who is the mysterious cousin who has come to live with her and her mother? When Eponine finds her mother and cousin listening to strange announcements on a forbidden radio, she realizes that nothing she’s believed about herself is true. Jennifer Bohnhoff teaches 7th grade social studies in Albuquerque, New Mexico. She is the author of several works of middle grade historical fiction. Her most recent book, Valverde, is set in New Mexico during the Civil War

Jennifer Bohnhoff teaches 7th grade social studies in Albuquerque, New Mexico. She is the author of several works of middle grade historical fiction. Her most recent book, Valverde, is set in New Mexico during the Civil War

Published on August 10, 2017 00:00

August 1, 2017

Old English, Beowulf, and the Prehistoric World

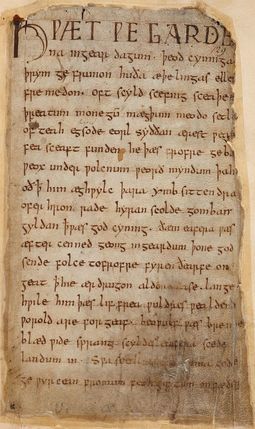

When many people think of Old English, they think of the writings of Shakespeare. While the Bard's language may seem old and difficult to understand, it is modern in comparison with real Old English. Click here to hear someone reading in Old English. I am willing to bet that few- if any- who do will be able to understand a single word.

When many people think of Old English, they think of the writings of Shakespeare. While the Bard's language may seem old and difficult to understand, it is modern in comparison with real Old English. Click here to hear someone reading in Old English. I am willing to bet that few- if any- who do will be able to understand a single word.Old English is the language of the Angles, who originated in the western area of what is now Germany. After they migrated across the channel, speakers called the area they settled Angeland, or Engeland, and their language Englisc. The language dominated the island from the 5th century until the 11th, when the Normans invaded, bringing their Norman French with them. The Normans became the lords and the Angles their servants, explaining why food often has Norman names while the animals, cared for by the servants, have Angle names. Beef is Norman in origin: Cow is Anglo. Mutton is Norman: Sheep is Anglo. The fact that Modern English is a mix of Old English, Norman, Viking (since they moved in, too!) and numerous other languages explains why English is such a difficult language in which to spell and pronounce words. Each language brought its own spelling and pronunciation rules into the mix.

Old English writings began to appear the early 8th century. Few original copies remain. One long epic poem, which may be the oldest surviving long poem in Old English, was bound into a collection called the Norwell Codex. This poem, which had no title, has come to be called by the name of its hero, Beowulf. It is considered one of the most important works of Old English literature.

The poem tells how Beowulf leaves Geatland, in what is now Sweden, to help Hrothgar, the king of the Danes. The story was considered just a story for many years. However, many of the characters appear in registers and legal documents of the 6th century. Archaeological excavations in Lejre, Denmark, the traditional location of Heorot, uncovered three halls, each about 160 ft long, that had been built in the middle of the 6th century, the time period of the Beowulf story.

It appears that the people and places depicted in Beowulf are real, and the background information about politics, family feuds, and migrations patterns are based on fact. But some elements of Beowulf come from a much earlier time. For instance, while the Scandinavian peoples had been converted to Christianity by the 6th century, many of the themes in Beowulf remain prechristian.

It appears that the people and places depicted in Beowulf are real, and the background information about politics, family feuds, and migrations patterns are based on fact. But some elements of Beowulf come from a much earlier time. For instance, while the Scandinavian peoples had been converted to Christianity by the 6th century, many of the themes in Beowulf remain prechristian. https://www.slideshare.net/smolinskie... Other elements suggest the story might hearken back to an earlier time, and the political elements are a later overlay to a story that might have been passed down through countless generations.

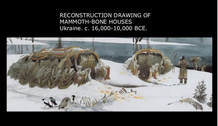

https://www.slideshare.net/smolinskie... Other elements suggest the story might hearken back to an earlier time, and the political elements are a later overlay to a story that might have been passed down through countless generations.The name of Hrothgar's mead hall, for

instance, is Heorot, which translates as Hart's Hall. Could the original hall have been constructed of the bones of the giant elk that roamed Europe at the end of the last Ice Age? Similar shelters, made of mammoth bones, have been found in the Ukraine.

And what about Grendle, the monster that Beowulf destroys? The poem calls him a fallen son of man. Might Grendle have been something distinctly man-like, yet different enough to cause discomfort? might Grendle have been a Neanderthal?

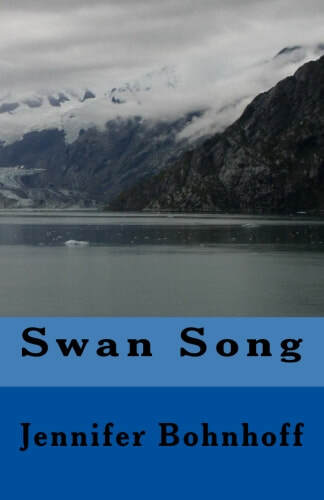

This is the scenario I present in my Young Adult novel, Swan Song.

I am not the first to associate Neanderthals with the Beowulf story. Michael Crichton did so in his 1976 novel, Eaters of the Dead. The difference between his novel and mine is that Crichton's novel is set in the tenth century and is structured as the journal of an Arab who visits the Rus, and early Russian people who are battling with a remnant group of Neanderthals who have managed to avoid extinction. My novel is set at the end of the last Ice Age, when Neanderthals and Humans coexisted in Europe. A second story line in Swan Song mirrors the action of the Paleolithic narrative, but is set in modern times. If the scribe who originally took the ancient story of Beowulf and modified it to reflect life in 6th century Europe, why can it be updated again to today?

I am not the first to associate Neanderthals with the Beowulf story. Michael Crichton did so in his 1976 novel, Eaters of the Dead. The difference between his novel and mine is that Crichton's novel is set in the tenth century and is structured as the journal of an Arab who visits the Rus, and early Russian people who are battling with a remnant group of Neanderthals who have managed to avoid extinction. My novel is set at the end of the last Ice Age, when Neanderthals and Humans coexisted in Europe. A second story line in Swan Song mirrors the action of the Paleolithic narrative, but is set in modern times. If the scribe who originally took the ancient story of Beowulf and modified it to reflect life in 6th century Europe, why can it be updated again to today?Jennifer Bohnhoff writes novels that are set in, or inspired by history. Her novels are available on Amazon and on other online booksellers.

Published on August 01, 2017 00:00

July 22, 2017

Fort Union: Guardian of the Santa Fe Trail

The ruins of the third Fort Union.

The ruins of the third Fort Union.  Fort Union rests out in the middle of nowhere, but a century and a half ago it was the center of a lot of activity. It has been rebuilt three times, each time responding to what was happening around it.

Fort Union rests out in the middle of nowhere, but a century and a half ago it was the center of a lot of activity. It has been rebuilt three times, each time responding to what was happening around it. Located near the convergence of the Mountain and Cimmaron branches, Fort Union's original task was to monitor the Santa Fe trail. The soldiers were charged with controlling Native Americans and, if wagon trains came under attack, to respond with campaigns against the Indians.

The original fort, constructed in the 1850s, was built close by the eastern edge of a high mesa in order to protect it from the incessant winds. Diaries from the period indicate that the protection was minimal, and that sand constantly seeped through cracks around windows and found its way into beds and food supplies.

It was thrown up quickly, and made of adobe and logs that were already in serious disrepair a decade later, when the Civil War began to disrupt life in the territory.

By August 1861, the Confederates under John Baylor had already claimed the southern half of New Mexico Territory and renamed it Arizona. The U.S. Army was convinced that invasion of Northern New Mexico was imminent, and that Fort Union was the key to holding the territory. However, the bluffs that protected it from wind also made it vulnerable to cannon fire should the Confederates be able to take them. A new fort was needed.

The Second Fort Union was built a mile and a half away from the first, in the open valley. Its earthwork walls, parapets, and moats covered 23 acres and were shaped like a star to accommodate 28 cannon. It was built by Hispanic

Volunteers since most of the Union Troops had been called east. The work went on 24 hours a day, with gangs of 200 men taking four hour shifts. The fort was ready by February 1862, when Confederates advanced up the Rio Grande and defeated the Union forces at the battle of Valverde. By March they had taken Albuquerque and then Santa Fe. It seemed that Fort Union was the only thing standing between the Confederates and the rich gold fields of Colorado.

Volunteers since most of the Union Troops had been called east. The work went on 24 hours a day, with gangs of 200 men taking four hour shifts. The fort was ready by February 1862, when Confederates advanced up the Rio Grande and defeated the Union forces at the battle of Valverde. By March they had taken Albuquerque and then Santa Fe. It seemed that Fort Union was the only thing standing between the Confederates and the rich gold fields of Colorado.Colonel Edward Canby, the Commander of Union forces in New Mexico Territory, said "The question is not of saving this post, but of saving New Mexico and defeating the Confederates in such a way that an invasion of this Territory will never again be attempted. It is essential to the general plan that this post should be retains if possible. Fort Union must be held."

The standoff at Fort Union never happened. No one on either side anticipated the gritty determination of the Colorado Volunteers when they refused to stay at the fort, and instead confronted the enemy in the mountains east of Santa Fe.

When visitors go to Fort Union National Monument, most of what they see is the remains of the third fort. Begun in 1863, this fort became the largest military outpost west of the Mississippi River. It served as an arsenal and depot, and was a safe resting place for travelers along the Santa Fe Trail. Again, its primary function was controlling the Indians and protecting Americans who used the trail.

When visitors go to Fort Union National Monument, most of what they see is the remains of the third fort. Begun in 1863, this fort became the largest military outpost west of the Mississippi River. It served as an arsenal and depot, and was a safe resting place for travelers along the Santa Fe Trail. Again, its primary function was controlling the Indians and protecting Americans who used the trail. The military abandoned the fort in 1891. By then the Apaches and Comanche had been subdued and the railroad had entered the state, effectively ending the

era of the Santa Fe trail. When I toured it in June 2017, there were few people there. I was able to walk among the ruins and read the interpretive signs without jostling crowds. The occasional sound of a bugle call broke the constant rush of the winds through the ruins. It was peaceful and pleasant, and I learned a lot from the small museum situated near the parking lot.

The fort is located 28 miles north of Las Vegas, New Mexico. To get there, take exit 366 off I-25 and go 8 miles north and west. The park, which is run by the National Park Service, is open from 8-5 from Memorial Day to Labor Day, and 8-4 the rest of the year. Check their website for special programs and tours.

Published on July 22, 2017 13:05

July 13, 2017

A Second Independence Day

This year I celebrated Independence Day twice. Like most Americans, I ate hamburgers, watched fireworks, and enjoyed the company of family on the 4th of July. I was visiting my middle son and his family in Pittsburgh, where I got to spend hours playing with my two year old granddaughter and my husband and son ran a 5K.

But two days later, I got to enjoy a second Independence Day, when I visited the town of Independence, Missouri.

My first stop was the National Frontier Trails Museum, which teaches about the trails that opened the American West. Beginning with Lewis and Clark, visitors learn about the Mormon Trail, Oregon and California Trails, Old Spanish Trail, and the one I was interested in, the Santa Fe Trail. Quotes from diaries and first hand accounts of the trails give the museum a very personal appeal.

The museum has a partnership with Pioneer Trails Adventures, an independent contractor that offers narrated covered wagon tours of historical sites in Independence as well as sleigh rides during the Christmas season, chuck wagon dinners, and rides in a white bridal surrey for special events.

The museum has a partnership with Pioneer Trails Adventures, an independent contractor that offers narrated covered wagon tours of historical sites in Independence as well as sleigh rides during the Christmas season, chuck wagon dinners, and rides in a white bridal surrey for special events.

I took a short tour and learned a lot from Ralph, the personable and knowledgeable owner. He taught me not only about Bess Truman's birthplace, early Independence history, and that wagon ruts are called "swales," but I learned a lot about Ed and Harry, the mules that pulled the wagon.

I highly recommend these rides!

Artifacts, included wagons, carts, supplies, weapons, clothing, original journals, foodstuffs and furniture enriched the experience.

Maps and murals, such as this one, depicting the Santa Fe plaza, covered the walls.

Next, I toured the house where Harry and Bess Truman lived. Although well appointed, this charming old Victorian house was surprisingly modest, especially the quaint kitchen, where the linoleum floor had been nailed down where a seam had separated, and the wallpaper near light switched looked worn. I would have liked to stay longer in Independence. If I had, I would have taken a second, longer tour with Pioneer Trails, visited the Truman Presidential Museum and Library, and gone into more of the historic houses, the 1859 jail, and the 1827 log courthouse. But the open road was calling and it was time to move on.

Next, I toured the house where Harry and Bess Truman lived. Although well appointed, this charming old Victorian house was surprisingly modest, especially the quaint kitchen, where the linoleum floor had been nailed down where a seam had separated, and the wallpaper near light switched looked worn. I would have liked to stay longer in Independence. If I had, I would have taken a second, longer tour with Pioneer Trails, visited the Truman Presidential Museum and Library, and gone into more of the historic houses, the 1859 jail, and the 1827 log courthouse. But the open road was calling and it was time to move on.  Jennifer Bohnhoff writes historical fiction and teaches New Mexico history to 7th graders in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Jennifer Bohnhoff writes historical fiction and teaches New Mexico history to 7th graders in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Her latest book, Valverde, about a Civil War Battle in New Mexico, came out this spring and is available on Amazon in paperback, Kindle, and large print edition.

She is always thrilled to meet someone more stubborn than she is, even if that someone has four legs.

For more information about her books, go to her website by clicking here.

But two days later, I got to enjoy a second Independence Day, when I visited the town of Independence, Missouri.

My first stop was the National Frontier Trails Museum, which teaches about the trails that opened the American West. Beginning with Lewis and Clark, visitors learn about the Mormon Trail, Oregon and California Trails, Old Spanish Trail, and the one I was interested in, the Santa Fe Trail. Quotes from diaries and first hand accounts of the trails give the museum a very personal appeal.

The museum has a partnership with Pioneer Trails Adventures, an independent contractor that offers narrated covered wagon tours of historical sites in Independence as well as sleigh rides during the Christmas season, chuck wagon dinners, and rides in a white bridal surrey for special events.

The museum has a partnership with Pioneer Trails Adventures, an independent contractor that offers narrated covered wagon tours of historical sites in Independence as well as sleigh rides during the Christmas season, chuck wagon dinners, and rides in a white bridal surrey for special events.I took a short tour and learned a lot from Ralph, the personable and knowledgeable owner. He taught me not only about Bess Truman's birthplace, early Independence history, and that wagon ruts are called "swales," but I learned a lot about Ed and Harry, the mules that pulled the wagon.

I highly recommend these rides!

Artifacts, included wagons, carts, supplies, weapons, clothing, original journals, foodstuffs and furniture enriched the experience.

Maps and murals, such as this one, depicting the Santa Fe plaza, covered the walls.

Next, I toured the house where Harry and Bess Truman lived. Although well appointed, this charming old Victorian house was surprisingly modest, especially the quaint kitchen, where the linoleum floor had been nailed down where a seam had separated, and the wallpaper near light switched looked worn. I would have liked to stay longer in Independence. If I had, I would have taken a second, longer tour with Pioneer Trails, visited the Truman Presidential Museum and Library, and gone into more of the historic houses, the 1859 jail, and the 1827 log courthouse. But the open road was calling and it was time to move on.

Next, I toured the house where Harry and Bess Truman lived. Although well appointed, this charming old Victorian house was surprisingly modest, especially the quaint kitchen, where the linoleum floor had been nailed down where a seam had separated, and the wallpaper near light switched looked worn. I would have liked to stay longer in Independence. If I had, I would have taken a second, longer tour with Pioneer Trails, visited the Truman Presidential Museum and Library, and gone into more of the historic houses, the 1859 jail, and the 1827 log courthouse. But the open road was calling and it was time to move on.  Jennifer Bohnhoff writes historical fiction and teaches New Mexico history to 7th graders in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Jennifer Bohnhoff writes historical fiction and teaches New Mexico history to 7th graders in Albuquerque, New Mexico.Her latest book, Valverde, about a Civil War Battle in New Mexico, came out this spring and is available on Amazon in paperback, Kindle, and large print edition.

She is always thrilled to meet someone more stubborn than she is, even if that someone has four legs.

For more information about her books, go to her website by clicking here.

Published on July 13, 2017 06:05