Jennifer Bohnhoff's Blog, page 35

November 13, 2018

Remnants of New Mexico History

Looking down from the mesa top where Posi is. This weekend I visited Ojo Caliente, a small town in Northern New Mexico, 50 miles north of Santa Fe. Ojo Caliente is Spanish for “warm eye,” and refers to the opening of a series of hot springs.

Looking down from the mesa top where Posi is. This weekend I visited Ojo Caliente, a small town in Northern New Mexico, 50 miles north of Santa Fe. Ojo Caliente is Spanish for “warm eye,” and refers to the opening of a series of hot springs.The valley in which Ojo Caliente lies has been inhabited a long time. The first known inhabitants emigrated from the Four Corners area in the late 1200s. They were a Tewa-speaking people, and they built a number of large pueblos, many of which had 2,000 or more rooms. The one closest to modern-day Ojo Calente is Posi-Ouinge, the 'Greenness Pueblo,' named such because of the green algae that clung to the rocks near the hot spring. The Tewas maintain that its pools provide access to the underworld. Posi-Ouinge was occupied from the 13th through the 16th century, when an epidemic caused the inhabitants to abandon the pueblo and move to Oke-onwi, also known by its Spanish name, San Juan.

Is this ridge a buried wall? Perhaps an archaeologist could tell you, but I can't.

Is this ridge a buried wall? Perhaps an archaeologist could tell you, but I can't.

Spanish settlement at Ojo Caliente began in the early 1700s, when it and other outposts were established to protect populations centers such as Santa Fe and Santa Cruz from raids by the Utes, Comanches and other tribes. These isolated outposts were settled by Mexican Indians, mixed-blood Spaniards, and genizaros, Indians who were sold as slaves to the Spanish and became household servants. Some of the Spanish had Jewish or Muslim ancestry and continued to practice their traditional rituals in secret. Others adopted traditions from the surrounding Indians, creating a unique culture.

Spanish settlement at Ojo Caliente began in the early 1700s, when it and other outposts were established to protect populations centers such as Santa Fe and Santa Cruz from raids by the Utes, Comanches and other tribes. These isolated outposts were settled by Mexican Indians, mixed-blood Spaniards, and genizaros, Indians who were sold as slaves to the Spanish and became household servants. Some of the Spanish had Jewish or Muslim ancestry and continued to practice their traditional rituals in secret. Others adopted traditions from the surrounding Indians, creating a unique culture.

The hike to Posi-Ouige begins directly behind the resort where the hot springs are located. After a short, scrambly climb, the trail follows the top of the ridge to the edge of the mesa. There are no walls left, and only the use of my admittedly fertile imagination gave me any sense that I was standing in a place that had once housed hundreds of people. But the ground was littered with more pottery shards than I had ever seen in one place before. Some had been laid on flat rocks, but many more pieces were underfoot. I’m no archaeologist, but the sheer number of pot shards told me that a lot of people had lived here.

The hike to Posi-Ouige begins directly behind the resort where the hot springs are located. After a short, scrambly climb, the trail follows the top of the ridge to the edge of the mesa. There are no walls left, and only the use of my admittedly fertile imagination gave me any sense that I was standing in a place that had once housed hundreds of people. But the ground was littered with more pottery shards than I had ever seen in one place before. Some had been laid on flat rocks, but many more pieces were underfoot. I’m no archaeologist, but the sheer number of pot shards told me that a lot of people had lived here.  Pottery mixed with rock and scattered all over the ground; it was hard not to step on a piece.

Pottery mixed with rock and scattered all over the ground; it was hard not to step on a piece.

This is a near-by ruin. The one I visited was not anywhere near this evident. https://www.archaeologysouthwest.org/2014/12/03/return-to-the-ojo-caliente-valley/

This is a near-by ruin. The one I visited was not anywhere near this evident. https://www.archaeologysouthwest.org/2014/12/03/return-to-the-ojo-caliente-valley/https://www.blm.gov/visit/posi-ouinge

http://dev.newmexicohistory.org/filedetails.php?fileID=4767 Jennifer Bohnhoff is a New Mexico native who teaches middle school English in a rural part of the state She is the author of several novels, including one set in New Mexico during the Civil War. You can learn more about her books here.

Published on November 13, 2018 20:31

November 8, 2018

the fields of flanders

This past summer a dear friend of mine had the good fortune to vacation in France. And I, thanks to the amazing technology of our times, got to see pictures, including the one above, while she was still there.

This past summer a dear friend of mine had the good fortune to vacation in France. And I, thanks to the amazing technology of our times, got to see pictures, including the one above, while she was still there.I emailed back a copy of "In Flanders Fields," which is one of the most famous of World War I poems. (or maybe the exchange went the other way, and I sent her the poem first; we exchanged numerous pictures for poems during her trip.) When she returned, she brought me a beautiful, hand-beaded poppy broach that I am wearing this month to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the end of World War 1. Unlike many of the poets of World War !, the author of In Flanders Fields was not an English schoolboy with romantic ideas about going off to war. John McCrae was a Canadian surgeon who had previously served in the Boer War in South Africa. While serving with the Canadian First Artillery in Ypres, Belgium, he had to officiate at the battlefield funeral of a young Lieutenant killed by artillery fire. The next day, McCrae wrote this poem while sitting on the back bumper of an ambulance overlooking the make-shift cemetery where poppies grew among the wooded crosses. McCrae, whose lungs had always been weak, died of pneumonia the following year.

In Flanders Fields

In Flanders Fields In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place, and in the sky,

The larks, still bravely singing, fly,

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the dead; short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe!

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high!

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields. Today I am going to present this poem to my eighth grade language arts classes. Tomorrow we will learn about Armistice Day and make paper poppies to wear on our lapels. We will not forget those who died, but hopefully we can find another way of dealing with conflict rather than taking up the quarrel and continuing to carry the torch of war.

Published on November 08, 2018 04:00

November 6, 2018

The Bitter Lie that war is sweet

Today I continue sharing World War 1 poetry with my 8th grade students. In the past we've studied poems that, while sad for the loss of young lives, depict war as glamorous, and soldiers as heros.

Today I continue sharing World War 1 poetry with my 8th grade students. In the past we've studied poems that, while sad for the loss of young lives, depict war as glamorous, and soldiers as heros.We take a turn today as we study Wilfred Owen's "Dulce et Decorum Est." It's a turn that Owen himself took as the reality of war seeped into his soul like trench mud into his boots.

Owen was a sensitive young man who considered joining the clergy. He volunteered to help the poor and sick in his parish until the tepid response of the Church of England to the sufferings of the underprivileged and dispossessed disillusioned him. He then taught in France for two years, returning to England and joining the army after the war began. Owen's first few letters home to his mother in the early winter of 1916 indicate that he was enamored with the glamor and excitement of war, but in less than a month reality had taken hold and he had seen enough. The events depicted in "Dulce et Decorum Est" occurred on January 12, 1917. By then, he was ready to deny Horace's Latin admonition to the Romans that it was sweet and good to die for one's country. Dulce et Decorum est

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs,

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots,

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of gas-shells dropping softly behind.

Gas! GAS! Quick, boys!—An ecstasy of fumbling

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time,

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime.--

Dim through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams, you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,--

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

Published on November 06, 2018 00:00

November 5, 2018

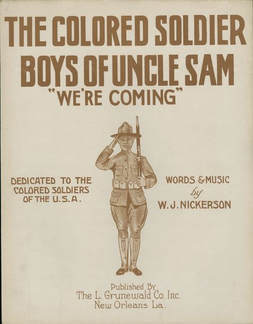

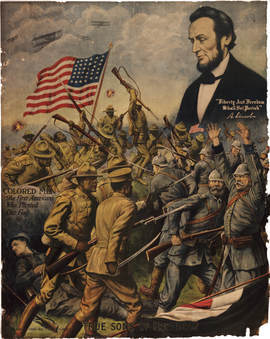

African Americans in World War I

November 11 marks the 100th anniversary of when the guns fell silent and World War I, the war to end all wars, ended. There are many stories to come out of this war. One that receives less attention than it should is the role of African Americans in the Army, and their contribution to the civil-rights movement.

November 11 marks the 100th anniversary of when the guns fell silent and World War I, the war to end all wars, ended. There are many stories to come out of this war. One that receives less attention than it should is the role of African Americans in the Army, and their contribution to the civil-rights movement.When war was declared in April 1917, volunteers rushed to fill the United State’s eight all-black National Guard infantry regiments. 89% of these men were assigned to noncombatant units, serving in quartermaster and engineering positions and under the leadership of white officers.

But the Black contribution to the war effort was too crucial to allow these troops to be marginalized. According to True Sons of Freedom, an article in the February 2018 edition of The American Legion, the 367,710 men who answered the call added up to 13% of the wartime Army in a time when African Americans comprised only 10% of the country’s population. The NAACP and other civil-rights organizations pressured the War Department to create two combat units: the 92nd Division, which served as part of the American Expeditionary Force, and 93rd Division, which was comprised of four infantry regiments created from the former National Guard regiments and was “loaned” to the French. The NAACP also pressured the Secretary of War, Newton E. Baker, to create a black officer training camp at Fort Des Moines, Iowa. The 106 captains, 329 first lieutenants and 204 second lieutenants who came out of this program and who served in the 92nd knew that white officers scrutinized their performance, hoping for proof that Blacks couldn’t lead.

The 92nd saw little engagement during the war. When it was first put in action in the Meuse-Argonne offensive, the inexperienced 368th Infantry Regiment, like many of the inexperienced AEF units, stumbled badly causing the division’s white officers to remove them from the line. They didn’t see action again until the final days of the war.

The 93rd, however, saw a lot of action in France. They fought in the battles of Meuse-Argonne, Champagne-Marne and Aisne-Marne. One regiment, the 369th Infantry, nicknamed the Harlem Hellfighters, saw front-line duty for 191 days, the record for U.S. regiments. Their service earned these men the Croix de Guerre.

The amount of battle time was not the only difference these two Divisions experienced. Men from the 93rd frequently expressed pleasure at how the French treated them. Many wrote home about the French civilians’ kindness and respect toward them. Soldiers in the 92nd, however, suffered from daily harassment and humiliation from their white superiors. Jim Crow policy was alive and well in the United States Army.

The shameful treatment of African American soldiers continued after the war. “Red Summer,” the name Civil-rights leader James Weldon gave to the summer of 1919 was race rioting in 25 American cities. Ten black veterans were lynched that summer. American Legion Posts were segregated, and some states, Louisiana among them, refused to sanction black posts. But African American Veterans continued to press for equal rights and equal opportunity, and in 1948 the armed forces were desegregated.

The shameful treatment of African American soldiers continued after the war. “Red Summer,” the name Civil-rights leader James Weldon gave to the summer of 1919 was race rioting in 25 American cities. Ten black veterans were lynched that summer. American Legion Posts were segregated, and some states, Louisiana among them, refused to sanction black posts. But African American Veterans continued to press for equal rights and equal opportunity, and in 1948 the armed forces were desegregated.World War I ended a hundred years ago, but the battle for civil rights continues, fought by descendants of the brave men who fought with courage and determination for a country that wasn’t sure it should even allow them to fight.

Jennifer Bohnhoff teaches middle school language arts in a rural school in central New Mexico. She is the author of several works of historical fiction for middle grade readers. You can read more about her books at her website.

Published on November 05, 2018 00:00

November 3, 2018

Remembering the veterans of World War 1

I remember World War 1 veterans marching in the 4th of July parades of my youth. They seemed so old to me, but they were no older than today's Vietnam veterans are to my own middle school students.

I remember World War 1 veterans marching in the 4th of July parades of my youth. They seemed so old to me, but they were no older than today's Vietnam veterans are to my own middle school students.My own grandfather was a World War 1 veteran. Harold Swedberg.was a farm boy and pioneering auto mechanic from Illinois. He served in France during WWI unloading cargo and transferring it to trains for the front and working in some kind of mysterious capacity, perhaps helping to develop early airplanes for war purposes. He never talked about his service with family members.

My grandfather had a German "potato masher" hand grenade, similar to this one, which is in the National World War 1 Museum in Kansas City. He used his as a doorstop. He always warned us kids not to touch it, that it was live. I believed him then, but now I wish I had that little memento.

My grandfather had a German "potato masher" hand grenade, similar to this one, which is in the National World War 1 Museum in Kansas City. He used his as a doorstop. He always warned us kids not to touch it, that it was live. I believed him then, but now I wish I had that little memento.Will Streets, the poet of A Lark Above the Trenches, never lived to frighten his grandchildren with strange souvenirs. He died in the Somme in 1916. A Lark Above the Trenches 1916

Hushed is the shriek of hurtling shells: and hark!

Somewhere within that bit of soft blue sky-

Grand in his loneliness, his ecstasy,

His lyric wild and free – carols a lark.

I in the trench, he lost in heaven afar,

I dream of Love, its ecstasy he sings;

Doth lure my soul to love till like a star

It flashes into Life: O tireless wings

That beat love’s message into melody –

A song that touches in this place remote

Gladness supreme in its undying note

And stirs to life the soul of memory –

‘Tis strange that while you’re beating into life

Men here below and plunged in sanguine strife!

Published on November 03, 2018 18:00

November 2, 2018

Commemorating the End of WorlD War 1

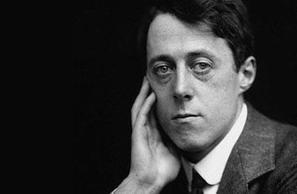

This Veteran's Day marks the 100th anniversary of the end of the First World War. To observe this day, I began a very short course on World War 1 Poets for my 8th grade classes today. The first poem I present was For the Fallen, by Laurence Binyon.

This Veteran's Day marks the 100th anniversary of the end of the First World War. To observe this day, I began a very short course on World War 1 Poets for my 8th grade classes today. The first poem I present was For the Fallen, by Laurence Binyon.The poet was in his 40s when the war broke out, and he'd never seen battle. He wrote this poem just a month into the war, while sitting on a cliff overlooking the sea in Cornwall. Later he would sign up to be an orderly with the Red Cross, and work a brief stint in a hospital in France.

For the Fallen

By Laurence Binyon

With proud thanksgiving, a mother for her children,

England mourns for her dead across the sea.

Flesh of her flesh they were, spirit of her spirit,

Fallen in the cause of the free.

�

Solemn the drums thrill; Death august and royal

Sings sorrow up into immortal spheres,

There is music in the midst of desolation

And a glory that shines upon our tears.

�

They went with songs to the battle, they were young,

Straight of limb, true of eye, steady and aglow.

They were staunch to the end against odds uncounted;

They fell with their faces to the foe.

�

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:

Age shall not weary them, nor the years contemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them.

�

They mingle not with their laughing comrades again;

They sit no more at familiar tables of home;

They have no lot in our labour of the day-time;

They sleep beyond England's foam.

�

But where our desires are and our hopes profound,

Felt as a well-spring that is hidden from sight,

To the innermost heart of their own land they are known

As the stars are known to the Night;

�

As the stars that shall be bright when we are dust,

Moving in marches upon the heavenly plain;

As the stars that are starry in the time of our darkness,

To the end, to the end, they remain.

Published on November 02, 2018 17:46

June 20, 2018

Salt Rising Bread: An Old Recipe

I’ve always been interested in the history of food, particularly as it might relate to the periods in which my novels are set. A year and a half ago, because I was interested in breadmaking during the Civil War, I wrote an article on the history of chemical leavening in breadmaking which you can access here.

I’ve always been interested in the history of food, particularly as it might relate to the periods in which my novels are set. A year and a half ago, because I was interested in breadmaking during the Civil War, I wrote an article on the history of chemical leavening in breadmaking which you can access here.

Now that school is out, I’ve got a little more time to play with historical recipes, and I’m back to making old fashioned breads. One I found curious, Salt-Rising Bread, appeared in my James Beard Cookbook, Beard on Bread. Beard called this recipe one of the oldest bread recipes in America, and included it as more of a curiosity than a successful bread. He warned that it could be temperamental and unreliable, but that just piqued my interest, so I had to do a little more research and then give it a try. Before the 1860s, when commercial yeast was developed, women had to rely on native yeasts (which are a form of fungus) or bacteria to leaven their baked goods. The leavening in Salt-Rising Bread is Closridium perfringens, a bacteria that can cause food poisoning but is rendered harmless by baking. Salt-Rising bread seems to have been developed in the late 1700s by pioneers in the Appalachian mountains. It is still produced in Kentucky, West Virginia, Western New York, and Western Pennsylvania. While this area does not include Gettysburg, where my novel The Bent Reed is set, it is close enough that it might have been baked there. It's also highly probable that the women of Gettysburg, like the women in every town and city in America, collected their own local funguses and bacteria to make similar recipes.

No one seems to know why this bread is called Salt-Rising. It does not taste salty, have an unusual amount of salt in it, and salt does not leaven the bread. One source suggested that early settlers kept the starter warm in a bed of heated salt. Another suggested that the salt inhibited yeast growth, allowing other leavenings to grow. I wonder if people just didn't know what leavened the bread, thinking it was the salt instead of bacteria from the potatoes. The starter for salt-rising bread grows in less time than traditional sourdough, but at a higher temperature. Several recipes I looked at said the starter needed to be held at 38-45°C (100–113 °F) for between 6 and 16 hours. James Beard’s recipe suggested waiting 12 to 24 hours. My batch developed a head of foam 15 hours after I began it. Several sources warned that the starter would smell like very ripe cheese. I found that it smelled more like the socks a teenaged boy brought back from scout camp. I do not recommend you have friends with sensitive noses over while you allow your starter to develop.

To make a Salt-rising starter, place 1 1/2 cups hot water, 1 medium potato, peeled and sliced thin, 2 TBS cornmeal, 1 tsp sugar and 1/2 tsp salt into a 2 quart mixing bowl and cover with a lid. If you are going to do this the old fashioned way, place the jar in a bowl filled with boiling water and cover with quilts. A more modern way to do the same thing is to place the jar in an electric oven with the light on, or a gas oven with the pilot light on. Let stand for between 12 and 24 hours, until the starter has developed at least 1/2 inch of foam. To turn the starter into bread, strain the starter over a mixing bowl. Pour 1/2 cup warm water over the potatoes in the strainer, then press down with the back of a spoon to release as much of the potato’s moisture as possible. Throw away the potatoes.

Add to the mixing bowl 1/4 tsp baking soda, 1/2 cup undiluted evaporated milk, 1 TBS melted butter, 1 tsp salt, and 2 cups of flour. Beat until very smooth. Continue adding up to 2 1/2 cups more flour, a cup at a time, until you have a soft dough.

Place a cup of flour on the counter. Turn your dough out of the bowl and knead it into the flour until the dough is smooth and soft. Shape into a loaf and place in a well buttered pan. Brush loaf with melted butter, cover with a piece of buttered (I use spray cooking oil) plastic wrap, and place in a warm, draft-free place to rise. I have a double oven, so I put it back into the oven with the light on. Rising may take as much as 4 or 5 hours.

Bake in a preheated oven at 375° for 35-45 minutes. Remove from pans to cool.

The resulting loaf had a very fine texture, but the top crust pulled away from the loaf. It had a slightly tangy taste to it, and was excellent with butter and toasted. It reminded me more of beer batter bread than traditional yeast bread, but I think it would be a good breakfast bread, and an excellent accompaniment to a hearty stew.

Jennifer Bohnhoff has written two novels set in the Civil War: The Bent Reed and Valverde. You can read more about all her novels here.

Published on June 20, 2018 07:00

June 17, 2018

Happy Father's Day to all you Daddies

#wsite-video-container-710453791273862068{ background: url(//www.weebly.comhttp://jenniferbohnhoff... } #video-iframe-710453791273862068{ background: url(//cdn2.editmysite.com/images/util/video... } #wsite-video-container-710453791273862068, #video-iframe-710453791273862068{ background-repeat: no-repeat; background-position:center; } @media only screen and (-webkit-min-device-pixel-ratio: 2), only screen and ( min-device-pixel-ratio: 2), only screen and ( min-resolution: 192dpi), only screen and ( min-resolution: 2dppx) { #video-iframe-710453791273862068{ background: url(//cdn2.editmysite.com/images/util/video... background-repeat: no-repeat; background-position:center; background-size: 70px 70px; } }

Published on June 17, 2018 00:00

June 12, 2018

Shifting Geography

I love old books. They give me a window into a different time, showing me how people thought and what they knew. When a friend recently invited me to help her purge her bookshelves, I jumped at the chance.

I love old books. They give me a window into a different time, showing me how people thought and what they knew. When a friend recently invited me to help her purge her bookshelves, I jumped at the chance.One of the books I came home with was Mitchell’s New Primary Geography, printed in Philadelphia in 1871. By this date, I assumed all the world had been mapped, with the possible exceptions of the extreme north and south poles . Since 1871 was the year that Henry Morton Stanley began his quest for Dr. Livingston, I could guess that some of the African interior remained uncharted. But the circumnavigation of the globe was old news, and, I assumed, most of the information presented wouldn’t be that much different than what present day geography books contained.

I was wrong.

On the first page, the book states that there are eight planets. Oh, wait: that’s the case again today. Clyde Tombaugh discovered Pluto, the ninth planet, in 1930, but Pluto was demoted from planetary status in 2006.

But the second page says that there are three continents: the Western, the Eastern, and the Australian. A map a few pages on has the words “Western Continent” spanning North and South America, while Europe, Asia and Africa are identified as the “Eastern Continent.” Antarctica is nowhere to be seen on this map. While I had always thought there were 7 Continents, a quick search of the web showed that some geographers are now combining Asia and Europe into one continent, setting the number at 6. Others count Greenland and claim 8 continents.

Later, on page 12, the continents are divided into the grand divisions of Europe, Asia, Africa (which is considered a peninsula), North and South America, and Oceania. Antarctica is nothing but a series of indistinct lines waving along the bottom of the map. I guess the Southern portion of the globe had yet to be mapped.

All of these differences are matters of exploration and/or different ways of organizing facts. Mitchell’s Geography becomes truly shocking to modern sensibilities on page 11, when it states that there are five races in the world, and that the White, or Caucasian is superior to the others. The book offers no explanation of this statement, but is presented as just as factual as the number of planets or continents. Perhaps the authors thought that White man's superiority could be attributed to climate. Mitchell asserts that the Earth is divided into three climate zones, which he states affect the constitution, customs, and health of mankind. The coldest parts of the globe, the Frigid Zone, makes men stupid and inactive according to this textbook. The Torrid Zone, where fruits and flowers abound, makes men weak and languid, with indolent habits. It’s only in the Temperate Zone where man is healthiest, happiest, and most civilized.

Page 12 divides the governmental systems of the world into empires, kingdoms and republics. There is no mention of tribal or communal organizations. The religions of the world are Christian, Jewish, Mohammedan, and Pagan. Strange, to lump Hinduism in with Native American religions into that last category.

When describing the population of the United States, this textbook states that “The population of the United States is upwards of thirty-eight millions, of whom about one-eighth are Negroes. The Indians are ignorant and barbarous, and are but few in number.” I suppose minimizing the number of Indians on the North American Continent helped justify the taking of their land. There is no mention of the Hispanics that occupied the Southwestern Territories of New Mexico, Texas, and Arizona.

I guess I shouldn’t have been surprised by the information provided in this old book, but still, it did shock me to see how very ethnocentric it was. Perhaps the world hasn’t changed much in 150 years, but our perception of it and the people who inhabit it certainly has. We still have a long way to go before society treats everyone equally, but at least we are no longer using textbooks that disparage so much of the human population.

Published on June 12, 2018 05:30

June 4, 2018

Dinosaurs in New Mexico

Last weekend my husband and I drove out to the North East corner of the state to meet with voters. Shaking hands and talking to people is something my husband has to do, now that he's been appointed to the State Court of Appeals and must run in a contested election to keep the seat. I just go along to offer mental support, answer questions that he can't (judges must be impartial, and therefore can't express opinions on subjects that might come before them!), and carry supplies.

Last weekend my husband and I drove out to the North East corner of the state to meet with voters. Shaking hands and talking to people is something my husband has to do, now that he's been appointed to the State Court of Appeals and must run in a contested election to keep the seat. I just go along to offer mental support, answer questions that he can't (judges must be impartial, and therefore can't express opinions on subjects that might come before them!), and carry supplies.

Busy though our schedule may be, my husband is kind enough to include something of interest to me. This time, he took an hour to let me see Clayton Lake State Park. Like most of the lakes in New Mexico, Clayton Lake is man made, and not much to write home about. But in the 1980s, heavy rains caused the lake to flood over the spillway, and the water scoured away sandstone to reveal the sixth best set of dinosaur tracks in the United States! The walk from the parking lot to the track site is only a quarter of a mile, on a paved path that would be accessible for wheel chairs and strollers. Once at the site, there are stairs to get down to the walkway shown in the picture below. A day use permit, required to park, costs $5. Have exact change, as no park attendant may be present.

Busy though our schedule may be, my husband is kind enough to include something of interest to me. This time, he took an hour to let me see Clayton Lake State Park. Like most of the lakes in New Mexico, Clayton Lake is man made, and not much to write home about. But in the 1980s, heavy rains caused the lake to flood over the spillway, and the water scoured away sandstone to reveal the sixth best set of dinosaur tracks in the United States! The walk from the parking lot to the track site is only a quarter of a mile, on a paved path that would be accessible for wheel chairs and strollers. Once at the site, there are stairs to get down to the walkway shown in the picture below. A day use permit, required to park, costs $5. Have exact change, as no park attendant may be present.

At least four different kinds of dinosaurs and some crocodiles left prints in the sandy beach of the inland sea that split the North American Continent in two during the Jurassic Period. Some of the prints are deep, indicating wet sand. Others are shallow and indistinct, indicating that the sand was dry at the time the prints were made. In one place there is an elongated print and a tail impression, indicating that the dinosaur slipped and used its tail to regain its balance. In another place, two prints show superimposed prints, as if the dinosaur nervously stood on two legs and shuffled indecisively back and forth.

At least four different kinds of dinosaurs and some crocodiles left prints in the sandy beach of the inland sea that split the North American Continent in two during the Jurassic Period. Some of the prints are deep, indicating wet sand. Others are shallow and indistinct, indicating that the sand was dry at the time the prints were made. In one place there is an elongated print and a tail impression, indicating that the dinosaur slipped and used its tail to regain its balance. In another place, two prints show superimposed prints, as if the dinosaur nervously stood on two legs and shuffled indecisively back and forth.

Most of the prints belong to two different species of Iguanodons, large plant eating dinosaurs that walked on two legs. Scientists can identify their prints because they show three distinct rounded toes. At least one baby Iguanodon walked long this beach. The tracks lead north and indicate that the dinosaurs were traveling together in a herd.

Most of the prints belong to two different species of Iguanodons, large plant eating dinosaurs that walked on two legs. Scientists can identify their prints because they show three distinct rounded toes. At least one baby Iguanodon walked long this beach. The tracks lead north and indicate that the dinosaurs were traveling together in a herd.

Other tracks show the three sharp talons that indicate a theropod. Scientists say these tracks were made by members of the Arocanthosaurus family, a relative of the Tyrannosaurus Rex that stood 12 feet high at the hip and could be 40 feet long.

Other tracks show the three sharp talons that indicate a theropod. Scientists say these tracks were made by members of the Arocanthosaurus family, a relative of the Tyrannosaurus Rex that stood 12 feet high at the hip and could be 40 feet long.  One of the signs suggested that the best time to see the most tracks was early morning or late afternoon, when shadows helped reveal them. The Judge and I visited this site in the late morning. There were lots of signs explaining what we were looking for, and we were grateful, because without the signs we might not have even recognized what we were looking for. I wondered how many times in the past I've traveled over sandstone shelves studded with huecos and depressions that might have been dinosaur tracks and hadn't even stopped to consider them. Most modern people aren't used to looking at tracks, but the hunters of old did. I had to wonder what Apache, or an even earlier Clovis or Folsom men might have thought when they came across these monstrous and unfamiliar prints in the ground. I can only guess that their hearts beat hard as they mentally constructed an image of the beast that might have produced such prints. That might be a scene worth writing. Jennifer Bohnhoff taught New Mexico History for several years and still enjoys learning about the state called The Land of Enchantment. She's yet to write about dinosaurs or early man, but she might someday. You can see her writing on more recent times at her website.

One of the signs suggested that the best time to see the most tracks was early morning or late afternoon, when shadows helped reveal them. The Judge and I visited this site in the late morning. There were lots of signs explaining what we were looking for, and we were grateful, because without the signs we might not have even recognized what we were looking for. I wondered how many times in the past I've traveled over sandstone shelves studded with huecos and depressions that might have been dinosaur tracks and hadn't even stopped to consider them. Most modern people aren't used to looking at tracks, but the hunters of old did. I had to wonder what Apache, or an even earlier Clovis or Folsom men might have thought when they came across these monstrous and unfamiliar prints in the ground. I can only guess that their hearts beat hard as they mentally constructed an image of the beast that might have produced such prints. That might be a scene worth writing. Jennifer Bohnhoff taught New Mexico History for several years and still enjoys learning about the state called The Land of Enchantment. She's yet to write about dinosaurs or early man, but she might someday. You can see her writing on more recent times at her website.

Published on June 04, 2018 12:06