Jennifer Bohnhoff's Blog, page 39

March 23, 2017

the life of a civil war soldier

If you are curious about what it was like to be a soldier during the Civil War, there's no better place to start than John D. Billings' memoir, Hard Tack and Coffee. Historian Henry Steele Commager calls it "one of the most entertaining of all civil war books."

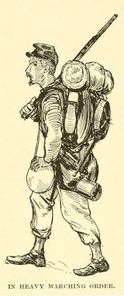

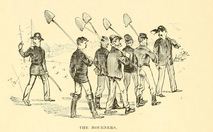

If you are curious about what it was like to be a soldier during the Civil War, there's no better place to start than John D. Billings' memoir, Hard Tack and Coffee. Historian Henry Steele Commager calls it "one of the most entertaining of all civil war books." Subtitled The Unwritten Story of Army Life, this book was published in 1887 by Billings, who served in the 10th Massachusetts Volunteer Light Artillery Battery under General Sickles and General Hancock. It is not a history of the war, and doesn't talk about battles and strategy. Instead, it explains what it was like to enlist in the Union Army, how soldiers managed the every day acts of eating and sleeping, of punishments and pastimes, and what it was like to keep the Army on the move.

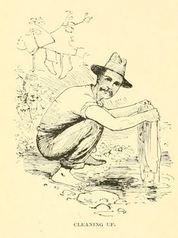

While some of the information in Billings' account is specific to his experiences in the Army of the Potomac, most of it would be useful for anyone who wanted to know about the life of the average soldier. Where else would we learn that troops camped near brooks washed their clothes in the running water until they realized that boiling them got rid of wood ticks and lice much better. To kill vermin, soldiers boiled their clothes in the mess kettles that also cooked their stews and boiled their coffee.

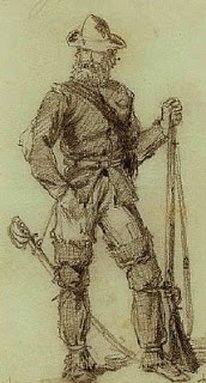

While some of the information in Billings' account is specific to his experiences in the Army of the Potomac, most of it would be useful for anyone who wanted to know about the life of the average soldier. Where else would we learn that troops camped near brooks washed their clothes in the running water until they realized that boiling them got rid of wood ticks and lice much better. To kill vermin, soldiers boiled their clothes in the mess kettles that also cooked their stews and boiled their coffee. While the writing is witty and the humor wry, the more than 200 pen and ink drawings are what really make Hard Tack and Coffee a treasure. The illustrations were created by another Civil War Veteran, Charles Reed, who served as bugler in the 9th Massachusetts Battery. Reed was awarded the Medal of Honor for saving the life of his battery commander at Gettysburg.

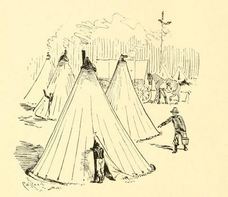

While the writing is witty and the humor wry, the more than 200 pen and ink drawings are what really make Hard Tack and Coffee a treasure. The illustrations were created by another Civil War Veteran, Charles Reed, who served as bugler in the 9th Massachusetts Battery. Reed was awarded the Medal of Honor for saving the life of his battery commander at Gettysburg. Reed shows the reader what a Sibley tent looked like. Invented by the man who left the Union Army to become a Brigadier General in the Confederacy, Sibley tents were used by both the North and the South. They resembled the teepees that Sibley would have seen while fighting Indians on the great plains and in New Mexico Territory, which Sibley invaded in 1862 in an attempt to conquer it for the South. One of my favorite pictures shows an interior view of a Sibley tent, and how the soldiers "spooned," or slept nested against each other in an attempt to keep warm.

Reed shows the reader what a Sibley tent looked like. Invented by the man who left the Union Army to become a Brigadier General in the Confederacy, Sibley tents were used by both the North and the South. They resembled the teepees that Sibley would have seen while fighting Indians on the great plains and in New Mexico Territory, which Sibley invaded in 1862 in an attempt to conquer it for the South. One of my favorite pictures shows an interior view of a Sibley tent, and how the soldiers "spooned," or slept nested against each other in an attempt to keep warm.General Sibley features prominently in Valverde, my historical novel about New Mexico during the Civil War. Reed's illustrations are now part of the public domain and are used in the Kickstarter Campaign for Valverde, which continues until April 4. Click here to see more of Reed's pen and ink sketches, and for information on how you can preorder a copy of Valverde at a discount.

Published on March 23, 2017 13:43

March 9, 2017

Paddy GraYdon Scheme to Stop the Confederacy

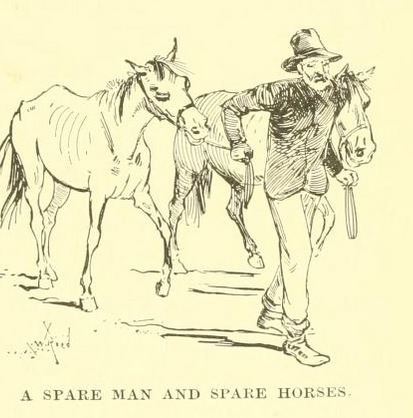

The Library of Congress calls this "a jurilla." Paddy and the members of his spy company probably didn't look much better. While enormous Union and Confederate Armies battled each other in the east, a relatively small Confederate Army was attempting to conquer the American Southwest. Their ultimate aim was the rich gold fields of Colorado and the deep harbors of California. Luckily for the Union, the American's had Paddy Graydon to destroy the Confederate's plans.

The Library of Congress calls this "a jurilla." Paddy and the members of his spy company probably didn't look much better. While enormous Union and Confederate Armies battled each other in the east, a relatively small Confederate Army was attempting to conquer the American Southwest. Their ultimate aim was the rich gold fields of Colorado and the deep harbors of California. Luckily for the Union, the American's had Paddy Graydon to destroy the Confederate's plans. Paddy Graydon was a rough, hard drinking, disagreeable man who was quick with his fists and short on temper, but his recklessness has earned him a place in the Civil War lore of New Mexico.

Paddy, whose Christian name was James, came to the United States from Ireland in order to escape the Potato Famine. It was 1853, and he was just 21 years old. Like many indigent immigrants, he joined the Army. Paddy became a dragoon, or light mounted infantry. He was posted to the southwest, where he learned to speak Spanish and Apache. Graydon's deprived childhood prepared, the blue eyed, 5' 7" man for the hardships of life in the saddle fighting Indians, bandits, renegades, and claim jumpers in an area that stretched from Santa Fe to the Mexican border. He stayed in the service for five years, until 1858.

Graydon opened a saloon near Sonoita, Arizona when he was discharged from the Army, His patrons were well-known for their rough and violent ways, but even such a tough clientele didn't provide Graydon with the excitement he was used to. The tough Irishman continued to track horse thieves, rescue captives from the Indians, and guide army patrols in his spare time.

When Confederate General Henry H. Sibley threatened to invade New Mexico in 1861, Graydon offered his services to Colonel Edward Canby, the highest ranking Union officer in the state. He formed an independent company of spies, most of them recruited from his former saloon patrons. Graydon's spies were known for being undisciplined and dangerous. They refused to wear uniforms or participate in drills and parades. But they were very good at collecting information. Graydon and his men excelled at wandering into Confederate camps and gathering information while posing as rebel soldiers.

Graydon's most famous escapade happened on a bitterly cold night in February, 1862, on the night before the Battle of Valverde. Under cover of darkness, Graydon and several volunteers crossed the icy Rio Grande and snuck up on the Confederate encampment. When they neared the corral that held Sibley's pack train, Graydon lit the fuses on boxes of explosives mounted on two old mules, then shooed them towards the Confederate lines. Unfortunately for Graydon, the mules turned back. Graydon and his men ran for their lives, and the mules blew up too far away to cause the carnage he had planned. However, the explosion caused Confederate pack mules to stampede down to the Rio Grande, where Union troops rounded them up.

Because of Graydon's scheme, the Confederate Army lost over 100 animals. Without their mules, they had to abandon many of the supplies that they desperately needed if they were going to conquer New Mexico and the rich gold fields of Colorado and California that Jefferson Davis had hoped to use to finance his fledgling country.

Jennifer Bohnhoff teaches New Mexico History to 7th grade students in Albuquerque. Paddy Graydon and his escapade with the mules shows up in her next book, Valverde, a middle grade historical novel about the Civil War in New Mexico which will be published in April. You can preorder a copy from this kickstarter campaign.

Jennifer Bohnhoff teaches New Mexico History to 7th grade students in Albuquerque. Paddy Graydon and his escapade with the mules shows up in her next book, Valverde, a middle grade historical novel about the Civil War in New Mexico which will be published in April. You can preorder a copy from this kickstarter campaign.

Published on March 09, 2017 09:00

March 1, 2017

Manuel Armijo: New Mexican Hero?

Manuel Armjio was dead by the time of the Civil War, but he’s important enough in New Mexican history that he still has a cameo in Valverde, my historical historical novel due out in late April. In an early scene, Raul Atencio, one of the main characters, is walking past the cemetery in San Miguel Mission, and he nods as a way of paying respect to the man who was, at that time, considered New Mexico’s greatest hero.

Manuel Armjio was dead by the time of the Civil War, but he’s important enough in New Mexican history that he still has a cameo in Valverde, my historical historical novel due out in late April. In an early scene, Raul Atencio, one of the main characters, is walking past the cemetery in San Miguel Mission, and he nods as a way of paying respect to the man who was, at that time, considered New Mexico’s greatest hero. Armijo began his public career in 1822, when he served as alcalde, a combination mayor and judge, in Albuquerque. During this period he protected his town by leading attacks against the Apache Indians, and was well respected for his administrative abilities. He was so well loved by the people that he was appointed governor in 1827.

While governor, Armijo sent reports to the central government expressing concern with poverty caused by the concentration of lands in the hands of a few people, and by drought. He asked for relief for New Mexicans who lived in poverty and hunger. Although his reports were ignored, his concern won him the appreciation of the people.

Armijo also expressed concern with illegal beaver trapping by Americans who were driving the animals to the point of extinction. He tried to impose tariffs and impound illegal furs, but the vast distances in the frontier made policing difficult. Unsurprisingly, his actions caused animosity with American traders and trappers, who retaliated by circulating rumors that the money gathered from tariffs and the resale of impounded furs lined Armijo’s pockets instead of helped New Mexico’s poor. Pictures of him in American papers depict a rotund man in a foolish and fancy uniform.

Armijo had returned to private business by 1837, when a rebellion broke out and the governor, a Mexican named Albino Perez, was murdered. Armijo led troops against the disorderly mob. He hung the four rebels responsible for starting the rebellion and executed the rebel governor the rebel-appointed governor.

When the Mexican government appointed Armijo to a second term as governor, Armijo imposed tariffs on American and New Mexican traders who brought goods over the Santa Fe Trail. He also distributed large land grants, ostensibly to draw in settlers from Mexico and the United States and widen the tax base. However, much of the money from those grants did not make it into New Mexico’s coffers. For instance, when Armijo granted Guadalupe Miranda and Charles Beaubien a large tract of land east of Taos along the Cimarron and Canadian Rivers in 1841, they deeded Armijo one-fourth interest in the land in exchange for his guarantees to support them against any future claims. They deeded another fourth to Charles Bent, who would later become Territorial Governor and be murdered by an angry mob for his alleged siphoning of money away from the people.

While Armijo was making a bundle on land, the Republic of Texas was threatening to take it all away. Texas claimed that their western border followed the Rio Grande, effectively cutting New Mexico in half. In 1841, a group dubbed the Texas-Santa Fe expedition attempted to make good on that claim. When their guides abandoned them, the Texans got lost in the Llano Estacado, where they endured frequent attacks by Apaches. By the time the expedition finally arrived in New Mexico, they were half-starved and in no condition to battle Armijo, who had a large force of well-armed soldiers from Mexico, which was angry about losing Texas. The Texans surrendered and were marched 2,000 miles under harsh conditions to Mexico City. They languished in Perote prison until the United States negotiated their release a year and a half later.

New Mexicans considered Armijo a hero for defeating the Texans, but the Texans felt otherwise, vilifying the governor. The father of Jemmy Martin, another character in Valverde, was a part of the Texas-Santa Fe expedition, and paints a rather brutal picture of the treatment the Texans received. In his account of the expedition, journalist George Wilkins Kendall depicted Armijo as an uneducated man from a poor family who worked his way up by stealing. This was untrue. Manuel Armijo’s family ranked among the ricos of Rio Abajo, which meant they were hacendados owning large herds and large tract of land.

In March 1844 Governor Armijo resigned his office. The man who replaced him raised tariffs on imported goods and taxed the people even more. In order to avoid revolt, Armijo was re-appointed to his third and final term as governor by mid 1945.

When the Mexican-American War began in May 1846, hundreds of enthusiastic but ill-equipped, ill-trained citizens answered Armijo’s call to arms against the American invasion. Although many of his volunteers were armed with nothing more than pitchforks and machetes, Armijo sent them to fortify Apache Canyon, a narrow space on the Santa Fe trail, just east of Santa Fe. By this time Armijo has grown so fat that a horse could not support his weight. When the rotund general arrived on the battlefield astride a strong-backed mule, Armijo found his men lined up against General Stephen Kearny and his 1,750 well armed and well trained soldiers. Armijo abandoned his forces. Some accounts say he even abandoned his own wife. What he didn’t abandon were the fine carpets, silver and china of the Governor’s Palace, which were loaded into carts. He, his treasures, and his bodyguard of 75 dragoons retreated to Chihuahua, Mexico, allowing General Kearny to take Santa Fe without a battle.

When asked why he abandoned New Mexico, Armijo justified himself by saying “I had but seventy-five men to fight three thousand. What could I do?” American writers, in their negative depiction of Armijo, have suggested that he accepted a bribe from the Americans for not opposing Kearny, but there is no concrete evidence to support this assertion. Armijo was tried for treason, but neither the Mexican Supreme Court or Congress found enough evidence to convict him. In January 1850 Armijo returned as a hero to New Mexico. He died at his home in Lemitar, New Mexico in January 1854 and was given a hero’s burial.

Jennifer Bohnhoff teaches New Mexico history to 7th graders in Albuquerque. She is the author of three historical novels for young readers. Valverde will be published in late April, but is currently available for preorder at a discount through Kickstarter.

Published on March 01, 2017 12:46

February 16, 2017

New Mexico Nicho

There's a small nicho in the entryway of my house. It's filled with things that remind me of the great state of New Mexico, its people and its history and distant past.

There's a small nicho in the entryway of my house. It's filled with things that remind me of the great state of New Mexico, its people and its history and distant past.I made the quilt that hangs on the nicho's back wall. The fabrics have pictures of chili peppers and cacti, and the colors remind me of a New Mexico sunset.

My youngest son made the ladder when he was learning how to lash sticks together with the Boy Scouts. It is similar to the ladders used in Pueblos and cliff houses. If you want to climb one, a great place to visit is Bandalier.

Nestled at the feet of the ladder is a decorated gourd bowl and two small pots that my husband and I received as wedding presents. I think they are from the Jemez Pueblo. There is also a rug that my husband's secretary gave him long ago. Many people assume that a rug made in New Mexico would be made by an Indian, and they'd be wrong. The Spanish brought sheep and weaving to the Southwest. Some Hispanic shops, such as Ortegas, have been weaving for hundreds of years.

Nestled at the feet of the ladder is a decorated gourd bowl and two small pots that my husband and I received as wedding presents. I think they are from the Jemez Pueblo. There is also a rug that my husband's secretary gave him long ago. Many people assume that a rug made in New Mexico would be made by an Indian, and they'd be wrong. The Spanish brought sheep and weaving to the Southwest. Some Hispanic shops, such as Ortegas, have been weaving for hundreds of years. My greatest treasures are older than the pots and gourds. My oldest son made the display case that holds an operculum that I found a few miles away from the site of the Robledo trackway, in the southern part of the state near Las Cruces. The operculum came from an ammonite that swam in the ocean that covered New Mexico during the Cretaceous era. Look back at the small pots in the picture above and you'll see a fossilized ammonite from that same sea. I didn't find that fossil, but know if was found in Texas.

I also have a large chunk of petrified wood in my nicho to remind me that this desert was once forested. This chunk is from Arizona's Petrified Forest, but I have picked up smaller pieces in many arroyos in New Mexico and in the dry bed of the Rio Puerco west of Rio Rancho. Probably the most spectacular place to see petrified forest is in the Bisti Badlands near Farmington.

I also have a large chunk of petrified wood in my nicho to remind me that this desert was once forested. This chunk is from Arizona's Petrified Forest, but I have picked up smaller pieces in many arroyos in New Mexico and in the dry bed of the Rio Puerco west of Rio Rancho. Probably the most spectacular place to see petrified forest is in the Bisti Badlands near Farmington.New Mexico hasn't always been the desert that it is today, but it's always been an interesting place. I've got the mementos to prove it.

Do you have any New Mexico momentos?

Published on February 16, 2017 00:00

February 5, 2017

Celebrating an American inventor

There are many ways to leaven bread. One way is to incorporate whipped egg whites, such as is done in angel food and sponge cakes. However, this was difficult and time consuming before Willis Johnson patented the eggbeater on February 5, 1884.

There are many ways to leaven bread. One way is to incorporate whipped egg whites, such as is done in angel food and sponge cakes. However, this was difficult and time consuming before Willis Johnson patented the eggbeater on February 5, 1884.Bread wasn’t always as easy to bake as it is now. Bread gets its airy structure by leavening: capturing gas bubbles in the elastic gluten of wheat.

Jennifer Bohnhoff writes historical and other novels for middle grade and older readers and is fascinated by quirky inventions.

Jennifer Bohnhoff writes historical and other novels for middle grade and older readers and is fascinated by quirky inventions.

Published on February 05, 2017 10:00

February 2, 2017

Grape and Canister

One of the things that makes historical fiction difficult for middle grade readers is the vocabulary. Tweens and young teens are often perplexed by words that don't make any sense to them.

Take, for instance, grape. Once, while teaching about the Civil War, I had a 7th grader ask me what was so scary about having grapes shot at you. She honestly believed that cannoneers loaded their guns with the same kind of grapes that make their way into jelly and jam. While this would lead to a sticky situation, and perhaps some stained uniforms, it likely wouldn't lead to many fatalities.

By Geni - Photo by user:geni, GFDL, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index... Grape, when referring to 18th and 19th Century war, is just a shortened form of the word grapeshot. Neither grape or grapeshot refer to shooting people with grapes. Rather, it refers to how small metal balls, or shot, were bundled together before being loaded into the gun. When the gun fired, the bag disintegrated and the shot spread out from the muzzle, much like shot from a shotgun.

By Geni - Photo by user:geni, GFDL, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index... Grape, when referring to 18th and 19th Century war, is just a shortened form of the word grapeshot. Neither grape or grapeshot refer to shooting people with grapes. Rather, it refers to how small metal balls, or shot, were bundled together before being loaded into the gun. When the gun fired, the bag disintegrated and the shot spread out from the muzzle, much like shot from a shotgun.

My students understand this concept better when I ask if any of their parents are hunters. Usually they know the purpose of buck shot (for shooting deer) and birdshot (smaller pellets, for shooting pigeons.)

Students who are involved in track and field suddenly realized that the shot they put in shot put is related to grapeshot, especially when I haul out the one piece of grapeshot I own and we compare them with the team's shot.

Grapeshot was especially effective against amassed infantry movements, such as Pickett's Charge at the Battle of Gettysburg. But by the Civil War, grapeshot was already becoming a thing of the past, replaced by canister.

By Minnesota Historical Society [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/b...)], via Wikimedia Commons Canister, which is sometimes known as case shot, involved small metal balls similar to the ones used in grapeshot. Instead of being encased in muslin, they were packed into a tin or brass container, the front of which blew out, scattering the balls into the oncoming enemy.

By Minnesota Historical Society [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/b...)], via Wikimedia Commons Canister, which is sometimes known as case shot, involved small metal balls similar to the ones used in grapeshot. Instead of being encased in muslin, they were packed into a tin or brass container, the front of which blew out, scattering the balls into the oncoming enemy.

Canister is a word that is unfamiliar to many middle grade readers, because they are too young to know what a film canister is. They do, however, know what a can is, and can readily accept that can is short for canister.

Jennifer Bohnhoff teaches New Mexico History to 7th grade students in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Her middle grade novel, The Bent Reed, is set at the Battle of Gettysburg. Her next novel, Valverde, is set in New Mexico during the Civil War and is due out this spring.

Take, for instance, grape. Once, while teaching about the Civil War, I had a 7th grader ask me what was so scary about having grapes shot at you. She honestly believed that cannoneers loaded their guns with the same kind of grapes that make their way into jelly and jam. While this would lead to a sticky situation, and perhaps some stained uniforms, it likely wouldn't lead to many fatalities.

By Geni - Photo by user:geni, GFDL, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index... Grape, when referring to 18th and 19th Century war, is just a shortened form of the word grapeshot. Neither grape or grapeshot refer to shooting people with grapes. Rather, it refers to how small metal balls, or shot, were bundled together before being loaded into the gun. When the gun fired, the bag disintegrated and the shot spread out from the muzzle, much like shot from a shotgun.

By Geni - Photo by user:geni, GFDL, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index... Grape, when referring to 18th and 19th Century war, is just a shortened form of the word grapeshot. Neither grape or grapeshot refer to shooting people with grapes. Rather, it refers to how small metal balls, or shot, were bundled together before being loaded into the gun. When the gun fired, the bag disintegrated and the shot spread out from the muzzle, much like shot from a shotgun.My students understand this concept better when I ask if any of their parents are hunters. Usually they know the purpose of buck shot (for shooting deer) and birdshot (smaller pellets, for shooting pigeons.)

Students who are involved in track and field suddenly realized that the shot they put in shot put is related to grapeshot, especially when I haul out the one piece of grapeshot I own and we compare them with the team's shot.

Grapeshot was especially effective against amassed infantry movements, such as Pickett's Charge at the Battle of Gettysburg. But by the Civil War, grapeshot was already becoming a thing of the past, replaced by canister.

By Minnesota Historical Society [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/b...)], via Wikimedia Commons Canister, which is sometimes known as case shot, involved small metal balls similar to the ones used in grapeshot. Instead of being encased in muslin, they were packed into a tin or brass container, the front of which blew out, scattering the balls into the oncoming enemy.

By Minnesota Historical Society [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/b...)], via Wikimedia Commons Canister, which is sometimes known as case shot, involved small metal balls similar to the ones used in grapeshot. Instead of being encased in muslin, they were packed into a tin or brass container, the front of which blew out, scattering the balls into the oncoming enemy.Canister is a word that is unfamiliar to many middle grade readers, because they are too young to know what a film canister is. They do, however, know what a can is, and can readily accept that can is short for canister.

Jennifer Bohnhoff teaches New Mexico History to 7th grade students in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Her middle grade novel, The Bent Reed, is set at the Battle of Gettysburg. Her next novel, Valverde, is set in New Mexico during the Civil War and is due out this spring.

Published on February 02, 2017 00:00

January 26, 2017

Anne E. Johnson on Finding your genre

Today's guest blogger is Anne E. Johnson, whose newest book, "Franni and the Duke," is a middle-grade historical mystery novel.

In May of 1608, the Duke of Mantua will throw the most spectacular wedding extravaganza in history. But it will all be ruined unless twelve-year-old Franni can keep a very big secret.

In May of 1608, the Duke of Mantua will throw the most spectacular wedding extravaganza in history. But it will all be ruined unless twelve-year-old Franni can keep a very big secret.

"Franni and the Duke," a middle-grade novel, sets a fictional mystery against a specific historical backdrop. It takes place during rehearsals for Arianna, an opera by the great composer Claudio Monteverdi. When Franni and her older sister Alli run away to Mantua, they both find work in Monteverdi's company. A messenger from the north announces that the next duke of the town of Bergamo is missing, and he may well be in Mantua. Alli notices that Luca, a singer she's in love with, fits the missing Duke's description. Although Franni thinks Luca is a pompous idiot, she promises for Alli's sake to keep Luca's secret safe and protect him from bounty hunters and Bergamo's rival family. She does this with the help of the company's set designer, a worldly wise and world-weary dwarf named Edgardo, who is not exactly what he seems.

Most of my published fiction is speculative — science-fiction and fantasy. Franni and the Duke is only my second work of historical fiction. Those who have known me for a while think of it as a logical genre, maybe the more logical genre for me to work in.

For sixteen years I taught music history and theory at an undergraduate certificate program in New York City. The only thing that could have pulled me away from that work was writing fiction. Around 2008 I started getting interested in writing, particularly for kids under age 13. I took a basic course with the Institute for Children's Literature. Most of the little assignments were fun and interesting, but the final project really got me fired up.

I was supposed to write the first three chapters of a children's novel. At the time, I was still teaching while working toward a PhD in Medieval musicology. I wrote the opening of a novel about a boy in the 13th-century England and his adventures seeking the stolen page of a book of Gregorian chants. Although I never finished my doctorate, I did finish that novel. Trouble at the Scriptorium was published in 2012.

[image error] Claudio Monteverdi With Franni and the Duke, I took a different approach. I was determined to work some real historical people into the plot. Claudio Monteverdi is a favorite composer of mine, and one whom even most fans of classical music underrate in terms of his importance. Of course, in my music history classes, I could clearly explain this to my captive audience. Monteverdi's was the first composer to develop the art of orchestration, using the timbers of different instruments for their emotional impact, and using rhythm and harmony to express the text of vocal music. That’s why his operas are still considered great today.

Yes, Franni is a mystery about a missing duke, but woven into the plot is all kinds of historical information about Monteverdi, who is a character in the story. Much of the story revolves around rehearsals for his opera Arianna, from 1608. That opera no longer exists. All we have is a single aria (song) from it (listen to that aria here), plus some descriptions of the elaborate production.

The production itself is half the fun of learning about this opera. It was financed by Duke Vincenzo Gonzaga of Mantua, Italy, whom I also include as a character. Franni meets both these historical men while she sews costumes for the opera. It was a thrill to do research on and then describe the duke’s exquisite palazzo, which still stands in Mantua.

Writing historical fiction requires delving into a whole new world. Sort of like science fiction, if you think about it.

You can learn more about Anne E. Johnson’s books and stories on her website.

In May of 1608, the Duke of Mantua will throw the most spectacular wedding extravaganza in history. But it will all be ruined unless twelve-year-old Franni can keep a very big secret.

In May of 1608, the Duke of Mantua will throw the most spectacular wedding extravaganza in history. But it will all be ruined unless twelve-year-old Franni can keep a very big secret."Franni and the Duke," a middle-grade novel, sets a fictional mystery against a specific historical backdrop. It takes place during rehearsals for Arianna, an opera by the great composer Claudio Monteverdi. When Franni and her older sister Alli run away to Mantua, they both find work in Monteverdi's company. A messenger from the north announces that the next duke of the town of Bergamo is missing, and he may well be in Mantua. Alli notices that Luca, a singer she's in love with, fits the missing Duke's description. Although Franni thinks Luca is a pompous idiot, she promises for Alli's sake to keep Luca's secret safe and protect him from bounty hunters and Bergamo's rival family. She does this with the help of the company's set designer, a worldly wise and world-weary dwarf named Edgardo, who is not exactly what he seems.

Most of my published fiction is speculative — science-fiction and fantasy. Franni and the Duke is only my second work of historical fiction. Those who have known me for a while think of it as a logical genre, maybe the more logical genre for me to work in.

For sixteen years I taught music history and theory at an undergraduate certificate program in New York City. The only thing that could have pulled me away from that work was writing fiction. Around 2008 I started getting interested in writing, particularly for kids under age 13. I took a basic course with the Institute for Children's Literature. Most of the little assignments were fun and interesting, but the final project really got me fired up.

I was supposed to write the first three chapters of a children's novel. At the time, I was still teaching while working toward a PhD in Medieval musicology. I wrote the opening of a novel about a boy in the 13th-century England and his adventures seeking the stolen page of a book of Gregorian chants. Although I never finished my doctorate, I did finish that novel. Trouble at the Scriptorium was published in 2012.

[image error] Claudio Monteverdi With Franni and the Duke, I took a different approach. I was determined to work some real historical people into the plot. Claudio Monteverdi is a favorite composer of mine, and one whom even most fans of classical music underrate in terms of his importance. Of course, in my music history classes, I could clearly explain this to my captive audience. Monteverdi's was the first composer to develop the art of orchestration, using the timbers of different instruments for their emotional impact, and using rhythm and harmony to express the text of vocal music. That’s why his operas are still considered great today.

Yes, Franni is a mystery about a missing duke, but woven into the plot is all kinds of historical information about Monteverdi, who is a character in the story. Much of the story revolves around rehearsals for his opera Arianna, from 1608. That opera no longer exists. All we have is a single aria (song) from it (listen to that aria here), plus some descriptions of the elaborate production.

The production itself is half the fun of learning about this opera. It was financed by Duke Vincenzo Gonzaga of Mantua, Italy, whom I also include as a character. Franni meets both these historical men while she sews costumes for the opera. It was a thrill to do research on and then describe the duke’s exquisite palazzo, which still stands in Mantua.

Writing historical fiction requires delving into a whole new world. Sort of like science fiction, if you think about it.

You can learn more about Anne E. Johnson’s books and stories on her website.

Published on January 26, 2017 00:00

January 19, 2017

Call in the Cavalry!

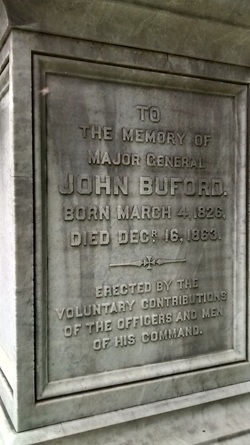

Buford's tombstone in the cemetery at West Point. (photo taken by the author) Cavalry officer John Buford played a key role in the opening day of the Battle of Gettysburg. Six months later, he was dead of typhoid fever.

Buford's tombstone in the cemetery at West Point. (photo taken by the author) Cavalry officer John Buford played a key role in the opening day of the Battle of Gettysburg. Six months later, he was dead of typhoid fever. Buford was born in Kentucky, but had moved to Illinois before being appointed to West Point. He graduated in 1848 and was posted to the dragoons, a word used for mounted infantry, where he saw some action along the frontier and in the expedition against the Mormons in Utah in 1857-1858. Henry Sibley and Edward Canby, who would later face off against each other in the Civil War Battle of Valverde, were also involved in the Mormon Campaign.

Buford began the Civil War serving in the staff of the defenses around Washington D.C. He then received a position on Pope's staff in northern Virginia, where he was rewarded a brigadier's star and command of a brigade of cavalry. Two of his brigades initiated the fighting northwest of Gettysburg. Buford managed to hold off the Confederate assaults until Union infantry enabled General Meade to make a stand south and east of the town on the next two days.

Buford contracted typhoid and had to relinquish his command on November 21, 1863. He was promoted to major general of volunteers just before he died in Washington on December 16, 1863.

Contrary to her students' belief, Jennifer Bohnhoff is not old enough to have known John Buford personally. She teaches New Mexico history to 7th graders in Albuquerque, and is the author of

The Bent Reed,

a novel set at Gettysburg. Her next book,

Valverde

, is about the Civil War in New Mexico as will be published this spring.

Contrary to her students' belief, Jennifer Bohnhoff is not old enough to have known John Buford personally. She teaches New Mexico history to 7th graders in Albuquerque, and is the author of

The Bent Reed,

a novel set at Gettysburg. Her next book,

Valverde

, is about the Civil War in New Mexico as will be published this spring.

Published on January 19, 2017 00:00

January 12, 2017

America's First RevolutionARY

By The Architect of the Capitol (http://www.aoc.gov/cc/art/nsh/popay.cfm) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

By The Architect of the Capitol (http://www.aoc.gov/cc/art/nsh/popay.cfm) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons When you think of American Revolutions, do you think of Americans fighting a foreign overlord in order to avoid excessive taxes, worship and live as they please, and follow their own form of government?

Do you think of Paul Revere, George Washington, and Nathaniel Hale?

Does 1776 come to mind?

Although the first American Revolution was about taxation and freedom of religion, it wasn't fought by colonists in the 13 colonies that hugged the eastern seaboard, and it wasn't a battle with England. America's first freedom fighters were Puebloan Indians, who rose up against their Spanish overlords in 1680. Their leader was a man named Popé.

The Spanish Empire expanded into the New World soon after Christopher Columbus "discovered" it in 1492. By 1540, they began exploring what is now Arizona and New Mexico. By the time Juan de Onate settled, in 1598, the Spanish had imposed themselves on over 100 Indian settlements, which they called pueblos because they reminded the Spaniards of villages back in Spain. The Puebloans were not a single people. Although they were all settled rather than nomadic, they spoke a number of different languages and had different religions and cultures.

From the very beginning, the actions of the Spanish towards the Puebloans were harsh and repressive. Oñate put down resistance from the Acoma pueblo by chopping a foot off every man over fifteen and enslaving the rest of the population. Priests set up missions next to pueblos, forcing the people to build churches and punishing them if they practiced their own ancient religions. Soldiers imposed the encomienda system, a forced-labor system similar to the serfdom of medieval Europe.

In the 1670s, a drought swept through the region, causing famine and increased raids by the Apaches, which Spanish and Pueblo soldiers were unable to prevent. Spanish and Indian alike were reduced to eating leather cart straps. Desperate for rain, the Puebloans turned to their gods, causing the Governor to arrest 47 Puebloan leaders on charges of witchcraft in 1675. Four medicine men were sentenced to death by hanging. The remaining men were publicly whipped and sentenced to prison. One of those men was Popé, a medicine man from Ohkey Owingeh (which the Spanish had renamed San Juan).

After eighty years, the Indians had had enough. Despite their different languages, the Puebloan leaders coordinated their attack to begin everywhere at once. Runners carried knotted ropes like the one in the statue's hand to mark the days until the revolt was to occur. When two of those runners were captured and tortured into revealing the date of the uprising, its leaders decided to start it early.

On August 10,1680, the Puebloans attacked. By August 13, all the Spanish settlements in New Mexico had been destroyed. 21 Franciscan friars and more than 400 Spaniards had died, but over a thousand survivors managed to make it to safety in the governor's palace in Sante Fe, and later escaped to El Paso, Texas, where they would bide their time until they could retake New Mexico twelve years later.

The Spanish were never able to eradicate Puebloan culture and religion. After the reconquest, they issued land grants to each Pueblo and appointed public defenders to protect the rights of the Indians and argue their legal cases in the Spanish courts. The Franciscan priests stopped trying to impose a theocracy on the Puebloans, who were now allowed to practice their traditional religion

Popé's statue stands in the Capitol Building in Washington DC. He was able to unite a disparate group of peoples and lead the most successful Indian uprising in the history of the West. The success of the Pueblo Revolt could be one reason why the Pueblo peoples continue to remain in their ancient ancestral homes instead of in distant reservations, why they are self governing, and can freely practice their religion.

Like primary sources? Click here for a transcript of a letter, dated September 8, 1680, in which the governor and captain-general of New Mexico, Don Antonio de Otermin, gives an account of what happened to him during the uprising.

The author of several novels, Jennifer Bohnhoff teaches New Mexico History to 7th graders in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Published on January 12, 2017 07:00

January 6, 2017

Birthday Cake!

Today's my birthday, and I'm celebrating by sharing one of my favorite cake recipes with you.

Before I was born, by mother taught 5th grade in the little town of Anthony, New Mexico. Back then, school lunch ladies made all the cafeteria food from scratch. When my mother got this recipe from the school lunch lady in Anthony, it needed several pounds of flour and sugar and served hundreds. She cut it down to a reasonable size to feed her family of six, and then I cut it down further. We've called it Crazy Chocolate Cake, although I've seen similar recipies with many different names.

What makes this cake crazy is what also made it cheap and easy to make when there was little in the larder: instead of being leavened by eggs, this cake uses baking soda vinegar to make the carbon dioxide that leavens it. The result is a moist, rich cake that's easy to make. It's virtually foolproof, too.

For more information on chemical leavenings, see this blog.

Crazy Chocolate Cake

1 1/2 cup flour

3 TBS cocoa

1/2 tsp. salt

1 cup sugar

1 tsp baking soda

Put all ingredients into an 8" square pan and mix together with a fork.

Mix together in a 2 cup measuring cup, then pour over the dry ingredients and mix. Be sure not to leave powdery pockets in the corners:

6 TBS salad oil

1 tsp. vanilla

1 cup water

1 TBS vinegar

Bake in a 350 oven for about 30 minutes. Cake is done when it springs back after you have pressed it with your finger. Frost with vanilla or chocolate butter frosting or a chocolate glaze.

Before I was born, by mother taught 5th grade in the little town of Anthony, New Mexico. Back then, school lunch ladies made all the cafeteria food from scratch. When my mother got this recipe from the school lunch lady in Anthony, it needed several pounds of flour and sugar and served hundreds. She cut it down to a reasonable size to feed her family of six, and then I cut it down further. We've called it Crazy Chocolate Cake, although I've seen similar recipies with many different names.

What makes this cake crazy is what also made it cheap and easy to make when there was little in the larder: instead of being leavened by eggs, this cake uses baking soda vinegar to make the carbon dioxide that leavens it. The result is a moist, rich cake that's easy to make. It's virtually foolproof, too.

For more information on chemical leavenings, see this blog.

Crazy Chocolate Cake

1 1/2 cup flour

3 TBS cocoa

1/2 tsp. salt

1 cup sugar

1 tsp baking soda

Put all ingredients into an 8" square pan and mix together with a fork.

Mix together in a 2 cup measuring cup, then pour over the dry ingredients and mix. Be sure not to leave powdery pockets in the corners:

6 TBS salad oil

1 tsp. vanilla

1 cup water

1 TBS vinegar

Bake in a 350 oven for about 30 minutes. Cake is done when it springs back after you have pressed it with your finger. Frost with vanilla or chocolate butter frosting or a chocolate glaze.

Published on January 06, 2017 00:00