Jennifer Bohnhoff's Blog, page 18

April 20, 2022

Bosque Redondo and the Goodnight-Loving Trail

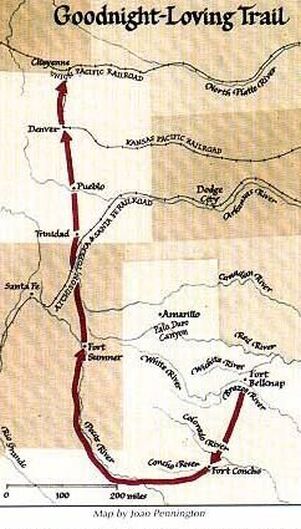

Charles Goodnight and Oliver Loving made a name for themselves, moving cattle from Texas, through New Mexico, and then onwards to Colorado and Wyoming. The trail they blazed to do so, named the Goodnight-Loving Trail, was created to supply beef for rations at Bosque Redondo.

Charles Goodnight and Oliver Loving made a name for themselves, moving cattle from Texas, through New Mexico, and then onwards to Colorado and Wyoming. The trail they blazed to do so, named the Goodnight-Loving Trail, was created to supply beef for rations at Bosque Redondo.The construction of the 1,000,000-acre Bosque Redondo Reservation and Fort Sumner, the military installation that guarded it, was authorized by Congress on October 31, 1862. General James Henry Carleton then had over 9,000 Navajo and Mescalero Apaches rounded up and relocated to the reservation on what became known as the Long Walk. Carleton justified the move by claiming that the Indians were raiding white settlements near their homelands.

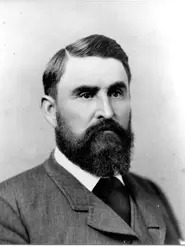

Charles Goodnight The intention in bringing the Apaches and Navajos to Bosque Redondo was to teach them modern farm practices that would make them self-sufficient. However, the lack of water and good soil provided poor conditions for agriculture, and it became clear that the government had not planned inadequately for the number of people who were brought to the reservation. Crop failures, drought, insect infestations and other issues caused severe food shortages. The demand for new food supplies became urgent.

Charles Goodnight The intention in bringing the Apaches and Navajos to Bosque Redondo was to teach them modern farm practices that would make them self-sufficient. However, the lack of water and good soil provided poor conditions for agriculture, and it became clear that the government had not planned inadequately for the number of people who were brought to the reservation. Crop failures, drought, insect infestations and other issues caused severe food shortages. The demand for new food supplies became urgent.In June of 1866, two Texas ranchers, Charles Goodnight and Oliver Loving, saw an opportunity in Bosque Redondo’s terrible straits. They hired 18 cowboys, rounded up 2,000 head of longhorn cattle, and took the Butterfield Overland Mail Route to Horsehead Crossing, on the Pecos River. From there, they blazed a new cattle trail up the Pecos to Fort Sumner. There they were able to sell most of their animals for 8 cents a pound, earning the pair a $12,000 profit. Goodnight took the profit back to Texas and began buying cattle from John S. Chisum’s Concho River range for a second drive to Fort Sumner later that same summer.

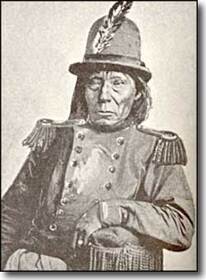

Chief Conniache While Goodnight headed east, Loving continued north from Fort Sumner up the Pecos to Las Vegas. He then followed the Santa Fe Trail to Raton Pass and around the base of the Rockies via Trinidad and Pueblo to Denver, Colorado.

Chief Conniache While Goodnight headed east, Loving continued north from Fort Sumner up the Pecos to Las Vegas. He then followed the Santa Fe Trail to Raton Pass and around the base of the Rockies via Trinidad and Pueblo to Denver, Colorado.When the drive reached the Raton Pass, they were stopped by a tollgate chain. Richens Lacey Wootton, often called “Uncle Dick” Wootton, an early mountain man, trapper, and hunter had moved on from Bent’s Fort in 1866, claimed the Raton Pass for himself, and hired a group of Utes under Chief Conniache to build a toll road through it. Later, Wootton sold the road to the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad for $1, a monthly stipend and grocery money for his wife for the rest of her life.

Dick Wootton's home in Raton Pass

Dick Wootton's home in Raton Pass

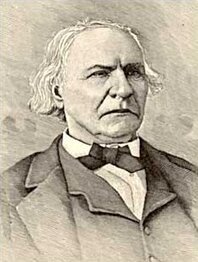

"Uncle Dick" Wootton Loving paid Wootton 10 cents per head, then drove the cattle through Trinidad, Pueblo, and on to Denver, where he sold them to cattleman John Wesley Iliff.

"Uncle Dick" Wootton Loving paid Wootton 10 cents per head, then drove the cattle through Trinidad, Pueblo, and on to Denver, where he sold them to cattleman John Wesley Iliff.Another, similar drive in 1867 did not go as well. After a heavy storm and an attack by Comanches had scattered their herd, Loving rode ahead to Fort Sumner to let them know there would be delays. On the way, Loving was attacked by Comanches. He managed to escape, but was seriously injured. The Army surgeon at Fort Sumner advised Loving amputate the injure limb, but Loving refused. He died of gangrene on September 25, 1867. Goodnight continued the drive to Colorado. When he returned, he exhumed Loving’s body and returned it to Texas, as Loving had requested before his death.

Oliver Loving By 1869, it was obvious that Bosque Redondo was a failure. After the Navajos were freed to return to their native lands, Fort Sumner was abandoned. Lucien Maxwell, a rich rancher and cattle baron bought the fort. He rebuilt one of the officers' quarters into a 20-room house, which is Sheriff Pat Garrett shot and killed Billy the Kid on July 14, 1881.

Oliver Loving By 1869, it was obvious that Bosque Redondo was a failure. After the Navajos were freed to return to their native lands, Fort Sumner was abandoned. Lucien Maxwell, a rich rancher and cattle baron bought the fort. He rebuilt one of the officers' quarters into a 20-room house, which is Sheriff Pat Garrett shot and killed Billy the Kid on July 14, 1881. Maxwell's house in Fort Sumner https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/goodnight-loving-trail

Maxwell's house in Fort Sumner https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/goodnight-loving-trailhttp://www.sangres.com/history/uncledick.htm#.YmBT9trMIak

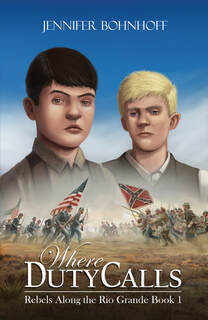

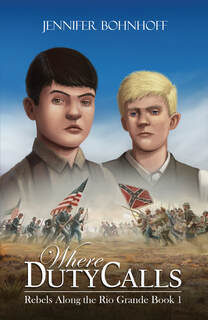

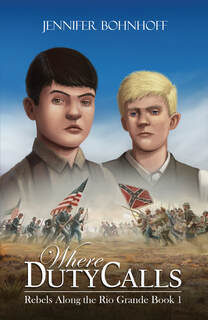

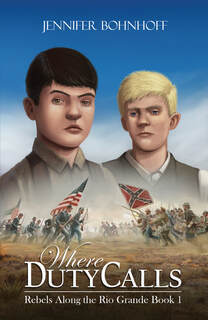

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a retired New Mexico history teacher who lives in the mountains of central New Mexico. Her next book, Where Duty Calls, is a historical novel for middle grade readers, and is set in New Mexico during the Civil War. It will be released by Kinkajou Press in June 2022 and is now available for preorder.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a retired New Mexico history teacher who lives in the mountains of central New Mexico. Her next book, Where Duty Calls, is a historical novel for middle grade readers, and is set in New Mexico during the Civil War. It will be released by Kinkajou Press in June 2022 and is now available for preorder.

Published on April 20, 2022 12:24

April 13, 2022

The Controversial Manuel Armijo

Pastel portrait of Manuel Armijo by Alfred S. Waugh, ca. 1840 Manuel Armijo was the last governor of New Mexico under the Mexican Republic, and the only person to serve in that office three times. Although he was dead by the time of the Civil War, he was important enough in New Mexican history that he still has an important role in Where Duty Calls, book 1 of a trilogy of middle grade historical novels set in New Mexico. In my attempt to present the historical controversy surrounding Armijo, the two main characters in my book have very different opinions of the man. One considers him a hero, while the other thinks him a villain. The truth, as is so often the case, is somewhere in between. Manuel Armijo was born in Albuquerque in 1793. His father, Vicente Ferrer Armijo was a stockman and lieutenant in the militia. His mother was María Bárbara Chávez. The Armijo and Chavez clans were among the ricos of the Rio Abajo region and were among the wealthiest families in the region. The family home was in the Plaza de San Antonio de Belen. Manuel Armijo was already a landowner by the age of seventeen when there is a record of him selling a piece of land in Albuquerque.

Pastel portrait of Manuel Armijo by Alfred S. Waugh, ca. 1840 Manuel Armijo was the last governor of New Mexico under the Mexican Republic, and the only person to serve in that office three times. Although he was dead by the time of the Civil War, he was important enough in New Mexican history that he still has an important role in Where Duty Calls, book 1 of a trilogy of middle grade historical novels set in New Mexico. In my attempt to present the historical controversy surrounding Armijo, the two main characters in my book have very different opinions of the man. One considers him a hero, while the other thinks him a villain. The truth, as is so often the case, is somewhere in between. Manuel Armijo was born in Albuquerque in 1793. His father, Vicente Ferrer Armijo was a stockman and lieutenant in the militia. His mother was María Bárbara Chávez. The Armijo and Chavez clans were among the ricos of the Rio Abajo region and were among the wealthiest families in the region. The family home was in the Plaza de San Antonio de Belen. Manuel Armijo was already a landowner by the age of seventeen when there is a record of him selling a piece of land in Albuquerque. Armijo began his public career in 1822, when he served as alcalde, a combination mayor and judge, in Albuquerque. During this period he protected his town by leading attacks against the Apache Indians, and was well respected for his administrative abilities. He was so well loved by the people that he was appointed governor in 1827.

While governor, Armijo sent reports to the central government expressing concern with poverty caused by the concentration of lands in the hands of a few people, and by drought. He asked for relief for New Mexicans who lived in poverty and hunger. Although his reports were ignored, his concern won him the appreciation of the people.

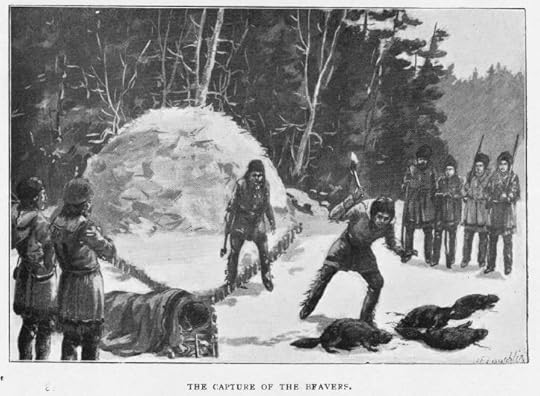

Armijo also expressed concern with illegal beaver trapping by Americans who were driving the animals to the point of extinction. He tried to impose tariffs and impound illegal furs, but the vast distances in the frontier made policing difficult. Unsurprisingly, his actions caused animosity with American traders and trappers, who retaliated by circulating rumors that the money gathered from tariffs and the resale of impounded furs lined Armijo’s pockets instead of helped New Mexico’s poor.

Charles Beaubien Armijo had returned to private business by 1837, when a rebellion broke out and the governor, a Mexican named Albino Perez, was murdered. Armijo led troops against the disorderly mob. He hung the four rebels responsible for starting the rebellion and executed the rebel-appointed governor.

Charles Beaubien Armijo had returned to private business by 1837, when a rebellion broke out and the governor, a Mexican named Albino Perez, was murdered. Armijo led troops against the disorderly mob. He hung the four rebels responsible for starting the rebellion and executed the rebel-appointed governor.

When the Mexican government appointed Armijo to a second term as governor, Armijo imposed tariffs on American and New Mexican traders who brought goods over the Santa Fe Trail. He also distributed large land grants, ostensibly to draw in settlers from Mexico and the United States and widen the tax base. However, much of the money from those grants did not make it into New Mexico’s coffers. For instance, when Armijo granted Guadalupe Miranda and Charles Beaubien a large tract of land east of Taos along the Cimarron and Canadian Rivers in 1841, they deeded Armijo one-fourth interest in the land in exchange for his guarantees to support them against any future claims. They deeded another fourth to Charles Bent, who would later become Territorial Governor and be murdered by an angry mob for his alleged siphoning of money away from the people. While Armijo was making a bundle on land, the Republic of Texas was threatening to take it all away. Texas claimed that their western border followed the Rio Grande, effectively cutting New Mexico in half. In 1841, a group dubbed the Texas-Santa Fe expedition attempted to make good on that claim. When their guides abandoned them, the Texans got lost in the Llano Estacado, where they endured frequent attacks by Apaches. By the time the expedition finally arrived in New Mexico, they were half-starved and in no condition to battle Armijo, who had a large force of well-armed soldiers from Mexico, which was angry about losing Texas. The Texans surrendered and were marched 2,000 miles under harsh conditions to Mexico City. They languished in Perote prison until the United States negotiated their release a year and a half later.

New Mexicans considered Armijo a hero for defeating the Texans and for his support of the people. In an early scene, Raul Atencio, one of the main characters in Where Duty Calls, is walking past the cemetery in San Miguel Mission, where Armijo is buried, Raul nods as a way of paying respect. That day at the family meal, his uncle gleefully tells the story of the failed Texas-Santa Fe expedition, and paints Armijo as New Mexico’s greatest hero. For obvious reasons, Texans felt otherwise. The father of Jemmy Martin, another character was a part of the Texas-Santa Fe expedition, and paints a rather brutal picture of the treatment the Texans received, vilifying Armijo.

In March 1844 Governor Armijo resigned his office. The man who replaced him raised tariffs on imported goods and taxed the people even more. In order to avoid revolt, Armijo was re-appointed to his third and final term as governor by mid 1845.

Raul Atencio and Jemmy Martin, the two characters on opposite sides in Where Duty Calls. Ian Bristow, illustrator. When the Mexican-American War began in May 1846, hundreds of enthusiastic but ill-equipped, ill-trained citizens answered Armijo’s call to arms against the American invasion. Although many of his volunteers were armed with nothing more than pitchforks and machetes, Armijo sent them to fortify Apache Canyon, a narrow space on the Santa Fe trail, just east of Santa Fe. By this time Armijo has grown so fat that a horse could not support his weight. The rotund general arrived on the battlefield astride a strong-backed mule, Armijo found his men lined up against General Stephen Kearny and his 1,750 well armed and well-trained soldiers. Armijo abandoned his forces. Some accounts say he even abandoned his own wife. What he didn’t abandon were the fine carpets, silver and china of the Governor’s Palace, which were loaded into carts. He, his treasures, and his bodyguard of 75 dragoons retreated to Chihuahua, Mexico, allowing General Kearny to take Santa Fe without a battle.

Raul Atencio and Jemmy Martin, the two characters on opposite sides in Where Duty Calls. Ian Bristow, illustrator. When the Mexican-American War began in May 1846, hundreds of enthusiastic but ill-equipped, ill-trained citizens answered Armijo’s call to arms against the American invasion. Although many of his volunteers were armed with nothing more than pitchforks and machetes, Armijo sent them to fortify Apache Canyon, a narrow space on the Santa Fe trail, just east of Santa Fe. By this time Armijo has grown so fat that a horse could not support his weight. The rotund general arrived on the battlefield astride a strong-backed mule, Armijo found his men lined up against General Stephen Kearny and his 1,750 well armed and well-trained soldiers. Armijo abandoned his forces. Some accounts say he even abandoned his own wife. What he didn’t abandon were the fine carpets, silver and china of the Governor’s Palace, which were loaded into carts. He, his treasures, and his bodyguard of 75 dragoons retreated to Chihuahua, Mexico, allowing General Kearny to take Santa Fe without a battle.

San Miguel Church, Socorro Illustration by Ian Bristow in Where Duty Calls When asked why he abandoned New Mexico, Armijo justified himself by saying “I had but seventy-five men to fight three thousand. What could I do?” American writers, in their negative depiction of Armijo, have suggested that he accepted a bribe from the Americans for not opposing Kearny, but there is no concrete evidence to support this assertion. Armijo was tried for treason, but neither the Mexican Supreme Court or Congress found enough evidence to convict him. In January 1850 Armijo returned as a hero to New Mexico. He died at his home in Lemitar, New Mexico in January 1854 and was given a hero’s burial in San Miguel Mission Church in Socorro..

San Miguel Church, Socorro Illustration by Ian Bristow in Where Duty Calls When asked why he abandoned New Mexico, Armijo justified himself by saying “I had but seventy-five men to fight three thousand. What could I do?” American writers, in their negative depiction of Armijo, have suggested that he accepted a bribe from the Americans for not opposing Kearny, but there is no concrete evidence to support this assertion. Armijo was tried for treason, but neither the Mexican Supreme Court or Congress found enough evidence to convict him. In January 1850 Armijo returned as a hero to New Mexico. He died at his home in Lemitar, New Mexico in January 1854 and was given a hero’s burial in San Miguel Mission Church in Socorro..

Jennifer Bohnhoff taught New Mexico history to 7th graders in Albuquerque and Edgewood, New Mexico. A native New Mexican, she is the author of several novels for middle grade and adult readers. Where Duty Calls will be published by Kinkajou Press, a division of Artemesia Publishing in June 2022 and is currently available for preorder as both a paperback or ebook.

Jennifer Bohnhoff taught New Mexico history to 7th graders in Albuquerque and Edgewood, New Mexico. A native New Mexican, she is the author of several novels for middle grade and adult readers. Where Duty Calls will be published by Kinkajou Press, a division of Artemesia Publishing in June 2022 and is currently available for preorder as both a paperback or ebook.

Published on April 13, 2022 09:31

April 11, 2022

Explaining New Mexico’s Mindset

A line editor who recently read through my upcoming novel, Where Duty Calls, had a lot of questions about the mindset of some of my characters. New Mexico had been a territory of the United States for almost two decades when the Civil War broke out. Why, then, did the characters think of Americans as foreigners? Did people with Hispanic ancestry think of themselves as Americans? Or did they yearn for the old days when Mexico, or even Spain ruled their land? Even if I knew the answer, I was hard-pressed to explain it. A book that I’m reading right now would have helped.

A line editor who recently read through my upcoming novel, Where Duty Calls, had a lot of questions about the mindset of some of my characters. New Mexico had been a territory of the United States for almost two decades when the Civil War broke out. Why, then, did the characters think of Americans as foreigners? Did people with Hispanic ancestry think of themselves as Americans? Or did they yearn for the old days when Mexico, or even Spain ruled their land? Even if I knew the answer, I was hard-pressed to explain it. A book that I’m reading right now would have helped.

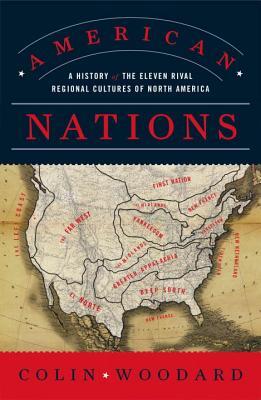

That book is American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America, by Colin Woodard. This award-winning journalist and historian argues that North America is culturally divided into eleven nations, whose boundaries are very different from the boundaries that divide Mexico, the United States, and Canada. Each of Woodard’s nations has unique historical roots which influence their people’s understanding of basic concepts of government. New Mexico is part of the nation that Woodard calls El Norte.

That book is American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America, by Colin Woodard. This award-winning journalist and historian argues that North America is culturally divided into eleven nations, whose boundaries are very different from the boundaries that divide Mexico, the United States, and Canada. Each of Woodard’s nations has unique historical roots which influence their people’s understanding of basic concepts of government. New Mexico is part of the nation that Woodard calls El Norte. According to Woodard, El Norte forms a band of land that

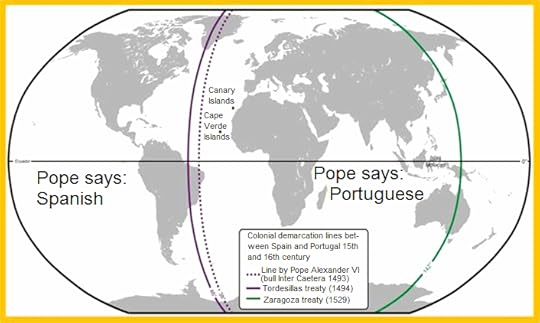

stretches from the Gulf of Mexico to the Pacific Ocean. The southern boundary of El Norte encompasses the Mexican states of Tamaulipas, Nuevo Leon, Coahuila, Chihuahua, Sonora, and Baja California. South and West Texas, Southern California, and Southern Arizona are also a part of El Norte. In New Mexico, El Norte stretches up the Rio Grande, all the way into Southern Colorado. The economy of this area is orientated towards the United States, but much of the culture and social norms have Hispanic roots. It is, as Woodard notes, a place apart. El Norte in general, and New Mexico in particular were places apart from mainstream society from their very inception. It was no surprise to me that Spain provided little support for its colony in New Mexico, which remained poor and isolated. What was news to me was the reason that Woodard gives for this neglect. When Pope Alexander VI granted Spain ownership of almost the entire Western Hemisphere, he believed that he was setting in motion the creation of a ‘universal monarchy’ that would bring about Judgement Day. Spanish King Philip II and his son, Philip III thought it was their duty not only to convert the Western Hemisphere’s Indians to Christianity before it was too late, but to subdue Protestant Europe before pressing on to conquer the Turks, then “Africa, Asia, Calcutta, China, Japan, and all the islands adjacent.” (pg. 27) When Spain had achieved world domination, Christ would come in glory and, no doubt, his servants the Spanish would receive a reward even greater than all the gold they had discovered in the New World.

So, while the gold and silver mines of Central and South America financed Spain’s religious wars in Europe, the most important commodity in El Norte was souls. The Spanish financed Franciscan missions that gathered in Native Americans in an attempt to turn them into Catholic, Spanish speaking farmers and tradesmen. The ideal, which was often corrupted, called for integrating Native Americans into their society, then granting them land on which to live. Many of the small villages in New Mexico were founded by Genizaros, people who were ethnically Native but socially Hispanic. Many Genizaro further integrated by marrying Hispanics. By the early 1700s, the majority of the population was Mestizo, or mixed parentage. In the lower portion of Mexico, society remained stratified, with those of pure Spanish blood ruling over the Mestizo and Genizaro peasantry. In El Norte, however, where almost everyone had at least one nonwhite ancestor, this was less pronounced. It was not parentage that separated the Spanish from the Indian: it was action. Act like someone whose ancestors came from Spain, and you could claim that ancestry yourself. El Norte ended up being populated by people that were neither Spanish nor Indian, but something unique to the area.

So, while the gold and silver mines of Central and South America financed Spain’s religious wars in Europe, the most important commodity in El Norte was souls. The Spanish financed Franciscan missions that gathered in Native Americans in an attempt to turn them into Catholic, Spanish speaking farmers and tradesmen. The ideal, which was often corrupted, called for integrating Native Americans into their society, then granting them land on which to live. Many of the small villages in New Mexico were founded by Genizaros, people who were ethnically Native but socially Hispanic. Many Genizaro further integrated by marrying Hispanics. By the early 1700s, the majority of the population was Mestizo, or mixed parentage. In the lower portion of Mexico, society remained stratified, with those of pure Spanish blood ruling over the Mestizo and Genizaro peasantry. In El Norte, however, where almost everyone had at least one nonwhite ancestor, this was less pronounced. It was not parentage that separated the Spanish from the Indian: it was action. Act like someone whose ancestors came from Spain, and you could claim that ancestry yourself. El Norte ended up being populated by people that were neither Spanish nor Indian, but something unique to the area. Although Spain was too embroiled in war against the English and other Europeans to have much time, energy, or resources to put into their colonies, they didn’t want to relinquish their power. Most of the Hispanics who had entered El Norte had been ordered to do so by the church or state, and could not travel from town to town or settle on new land without permission from the King or his Viceroy. Citizens were not allowed to trade with anyone but the Spanish government, which meant that any goods New Mexican’s offered for sale had to go through Mexico, via the Camino Real. Any items that New Mexicans wanted to purchase had to come over the same road. Resupply caravans of ox-drawn wooden carts arrived in New Mexico only once every three or four years.

Although Spain was too embroiled in war against the English and other Europeans to have much time, energy, or resources to put into their colonies, they didn’t want to relinquish their power. Most of the Hispanics who had entered El Norte had been ordered to do so by the church or state, and could not travel from town to town or settle on new land without permission from the King or his Viceroy. Citizens were not allowed to trade with anyone but the Spanish government, which meant that any goods New Mexican’s offered for sale had to go through Mexico, via the Camino Real. Any items that New Mexicans wanted to purchase had to come over the same road. Resupply caravans of ox-drawn wooden carts arrived in New Mexico only once every three or four years.Woodard says that El Norte had no self-government, no elections, and no possibility for local people to play any significant role in politics. The governors were often also military commanders. Under them, the local patron took care of his peons in a system not unlike medieval serfdom. However, the wide swaths of unsettled land allowed people who wished to escape the watchful eyes of the priests and military could move into the wilds or in with the Native Americans.

Because of their isolation and the neglect of their government, the people of New Mexico developed self-sufficiency and adaptability. They were a people with ties to both their Hispanic and Indian roots, and were intolerant of tyranny and distrustful of outsiders. When the United States claimed New Mexico during the Mexican-American war, most New Mexicans considered the Americans just another government far away from them that might try to assert itself over them. They didn’t want America telling them what to do any more than they’d wanted Mexico to do so, or Spain before that. When the Civil War began, and New Mexico was asked to take sides between the Union or Confederacy, many chose not to choose. The May 11, 1861 of the Santa Fe Gazette put it this way:

“What is the position of New Mexico?

The answer is a short one.

She desires to be let alone.

In her own good time she will say her say,

and choose for herself

the position she wishes to occupy

in the new disposition

of the new disrupted power

of the United States.” Woodard states that the border that divides Mexico from the United States also divides El Norte. While many people are clamoring for a wall to be build on the border, Woodard says that the situation resembles Germany during the Cold War. He says that the wall separates two peoples with a common culture. One thing I did not realize was that many of those peoples would prefer to unite and form their own country. He says that Charles Truxillo, a professor of Chicano studies at the University of New Mexico predicts that this nation, which he calls La Republica del Norte, will come into existence by the end of the twenty-first century.

A native New Mexican, Jennifer Bohnhoff has spent a lifetime explaining to people from elsewhere that no, New Mexico does not use the peso, and yes, we are pretty good at speaking English.

A native New Mexican, Jennifer Bohnhoff has spent a lifetime explaining to people from elsewhere that no, New Mexico does not use the peso, and yes, we are pretty good at speaking English.

Where Duty Calls, a novel for middle grade readers about the Civil War in New Mexico, will be available in June 2022 from Kinkajou Press, a division of Artemesia Publishing. You can preorder it by clicking here.

Where Duty Calls, a novel for middle grade readers about the Civil War in New Mexico, will be available in June 2022 from Kinkajou Press, a division of Artemesia Publishing. You can preorder it by clicking here.A note about Bookshop.org.

Bookshop.org is an international online retailer that offers small independent booksellers the ability to host their own online retail space. Every sale on their website benefits independent booksellers. They also allow readers and reviewers to become affiliates, who earn a commission for every sale they direct to their website.

I sell my own books through Bookshop.org. I am also a Bookshop.org affiliate. If you purchase a book by clicking through a Bookshop.org link that I have provided, whether it is my book or authored by someone else, I will receive a commission, and Bookshop.org will donate a matching commission to independent booksellers.

I provide these links as a convenience to you. However, I applaud you if you choose to check out these books at your local library or buy them through your local, independent bookseller. It is far more important to me that you read than that I get a small commission.

Published on April 11, 2022 15:05

April 5, 2022

Canister and Grapeshot

Before I became a full-time writer, I taught history and English to middle school students. I found that one of the things that made historical fiction difficult for my students was the vocabulary. Many terms were perplexing to young teens.

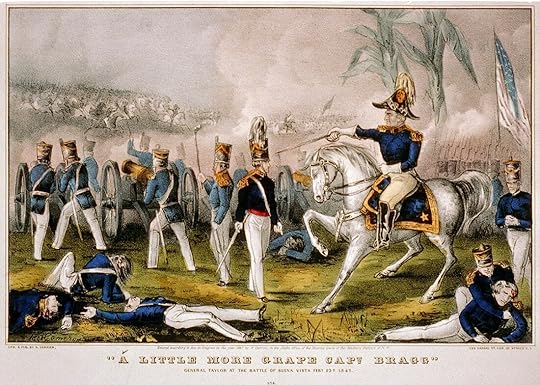

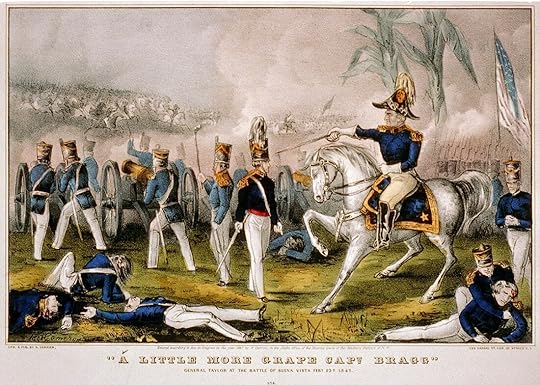

This became apparent one day when a 7th grader asked me what was so scary about having grapes shot at you. We were studying the Mexican American War, and read that the cannons were loaded with grape. She honestly believed that cannoneers loaded their guns with the same kind of grapes that make their way into jelly and jam. While this would lead to a sticky situation, and perhaps some stained uniforms, it likely wouldn't lead to many fatalities. "A little more grape, Captain Bragg." General Zachary Taylor's comment at the Mexican American War Battle of Buena Vista (February 23, 1847) continues to confuse students.

"A little more grape, Captain Bragg." General Zachary Taylor's comment at the Mexican American War Battle of Buena Vista (February 23, 1847) continues to confuse students.

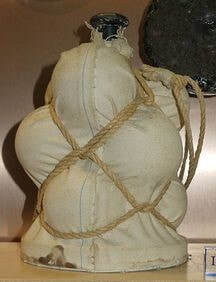

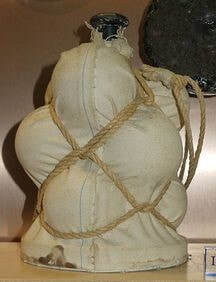

By Geni - Photo by user:geni, GFDL, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index... Grape, when referring to 18th and 19th Century war, is just a shortened form of the word grapeshot. Neither grape or grapeshot refer to shooting people with grapes. Rather, it refers to how small metal balls, or shot, were bundled together before being loaded into the gun. Those bundles resembled clusters of grape: hence the name. When the gun fired, the bag disintegrated and the shot spread out from the muzzle, much like shot from a shotgun.

By Geni - Photo by user:geni, GFDL, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index... Grape, when referring to 18th and 19th Century war, is just a shortened form of the word grapeshot. Neither grape or grapeshot refer to shooting people with grapes. Rather, it refers to how small metal balls, or shot, were bundled together before being loaded into the gun. Those bundles resembled clusters of grape: hence the name. When the gun fired, the bag disintegrated and the shot spread out from the muzzle, much like shot from a shotgun.

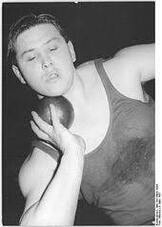

When I began teaching out in the country, I found that this perplexed students less. Although a few of my city kids were hunters or had a father or mother who hunted, many more of my country kids did so. They knew that buck shot was fired from shotguns when shooting deer, and birdshot, with its smaller pellets, was effective for shooting pigeons. But even in the country, students were dumbfounded that anyone used shot on grapes. I also coached track and field. My 7th grade students who were also athletes quickly realized that the shot they "put" in shot put was related to grapeshot.

I also coached track and field. My 7th grade students who were also athletes quickly realized that the shot they "put" in shot put was related to grapeshot.

Grapeshot was especially effective against amassed infantry movements, such as Pickett's Charge at the Battle of Gettysburg or the Confederate charge of McRae's Guns at the Battle of Valverde. But by the Civil War, grapeshot was already becoming a thing of the past, replaced by canister.

By Minnesota Historical Society [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/b...)], via Wikimedia Commons Canister, which is sometimes known as case shot, involved small metal balls similar to the ones used in grapeshot. Instead of being encased in muslin, they were packed into a tin or brass container, the front of which blew out, scattering the balls into the oncoming enemy.

By Minnesota Historical Society [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/b...)], via Wikimedia Commons Canister, which is sometimes known as case shot, involved small metal balls similar to the ones used in grapeshot. Instead of being encased in muslin, they were packed into a tin or brass container, the front of which blew out, scattering the balls into the oncoming enemy.

Canister is a word that is unfamiliar to many middle grade readers. They are too young to know what a film canister is. They do, however, know what a can is, and can readily accept that can is short for canister.

Understanding vocabulary words like grape and canister can help middle grade readers understand the historical fiction they are reading. Understanding the fiction can lead them to understand the history behind it, enriching their lives and making their reading much more informative and pleasurable.

After many years in the classroom, Jennifer Bohnhoff is now devoting herself to full time writing. Her novel The Bent Reed is for middle grade readers that is set at Gettysburg during the Civil War. Where Duty Calls, the first in a trilogy of novels about New Mexico during the Civil War is now available for preorder and will be published by Kinkajou Press on June 14, 2022.

This became apparent one day when a 7th grader asked me what was so scary about having grapes shot at you. We were studying the Mexican American War, and read that the cannons were loaded with grape. She honestly believed that cannoneers loaded their guns with the same kind of grapes that make their way into jelly and jam. While this would lead to a sticky situation, and perhaps some stained uniforms, it likely wouldn't lead to many fatalities.

"A little more grape, Captain Bragg." General Zachary Taylor's comment at the Mexican American War Battle of Buena Vista (February 23, 1847) continues to confuse students.

"A little more grape, Captain Bragg." General Zachary Taylor's comment at the Mexican American War Battle of Buena Vista (February 23, 1847) continues to confuse students.

By Geni - Photo by user:geni, GFDL, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index... Grape, when referring to 18th and 19th Century war, is just a shortened form of the word grapeshot. Neither grape or grapeshot refer to shooting people with grapes. Rather, it refers to how small metal balls, or shot, were bundled together before being loaded into the gun. Those bundles resembled clusters of grape: hence the name. When the gun fired, the bag disintegrated and the shot spread out from the muzzle, much like shot from a shotgun.

By Geni - Photo by user:geni, GFDL, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index... Grape, when referring to 18th and 19th Century war, is just a shortened form of the word grapeshot. Neither grape or grapeshot refer to shooting people with grapes. Rather, it refers to how small metal balls, or shot, were bundled together before being loaded into the gun. Those bundles resembled clusters of grape: hence the name. When the gun fired, the bag disintegrated and the shot spread out from the muzzle, much like shot from a shotgun.When I began teaching out in the country, I found that this perplexed students less. Although a few of my city kids were hunters or had a father or mother who hunted, many more of my country kids did so. They knew that buck shot was fired from shotguns when shooting deer, and birdshot, with its smaller pellets, was effective for shooting pigeons. But even in the country, students were dumbfounded that anyone used shot on grapes.

I also coached track and field. My 7th grade students who were also athletes quickly realized that the shot they "put" in shot put was related to grapeshot.

I also coached track and field. My 7th grade students who were also athletes quickly realized that the shot they "put" in shot put was related to grapeshot.Grapeshot was especially effective against amassed infantry movements, such as Pickett's Charge at the Battle of Gettysburg or the Confederate charge of McRae's Guns at the Battle of Valverde. But by the Civil War, grapeshot was already becoming a thing of the past, replaced by canister.

By Minnesota Historical Society [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/b...)], via Wikimedia Commons Canister, which is sometimes known as case shot, involved small metal balls similar to the ones used in grapeshot. Instead of being encased in muslin, they were packed into a tin or brass container, the front of which blew out, scattering the balls into the oncoming enemy.

By Minnesota Historical Society [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/b...)], via Wikimedia Commons Canister, which is sometimes known as case shot, involved small metal balls similar to the ones used in grapeshot. Instead of being encased in muslin, they were packed into a tin or brass container, the front of which blew out, scattering the balls into the oncoming enemy.Canister is a word that is unfamiliar to many middle grade readers. They are too young to know what a film canister is. They do, however, know what a can is, and can readily accept that can is short for canister.

Understanding vocabulary words like grape and canister can help middle grade readers understand the historical fiction they are reading. Understanding the fiction can lead them to understand the history behind it, enriching their lives and making their reading much more informative and pleasurable.

After many years in the classroom, Jennifer Bohnhoff is now devoting herself to full time writing. Her novel The Bent Reed is for middle grade readers that is set at Gettysburg during the Civil War. Where Duty Calls, the first in a trilogy of novels about New Mexico during the Civil War is now available for preorder and will be published by Kinkajou Press on June 14, 2022.

Published on April 05, 2022 23:00

April 3, 2022

Animal books for Young Readers

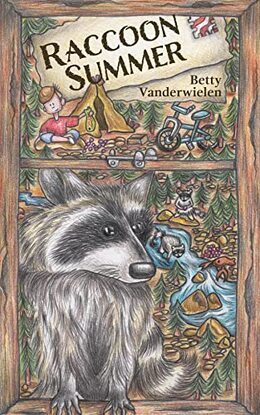

A couple of books about animals crossed by desk recently. They are very different and are for different age groups, but they are both fun reads.  Any kid who loves animals, especially wild ones, will love Raccoon Summer by Betty Vanderwielen. When his father hits and kills a raccoon that was crossing the road, Lance feels compelled to find the babies she’s left behind. Lance’s father is no raccoon lover; he’s an insurance agent who’s had to settle too many claims caused by raccoon damage. His stepmother wants nothing to do with the little creatures, either, so Lance recruits a neighbor with some wildlife rescue experience to help him with three kits that are so small that their eyes aren’t even open yet. The two begin a program that starts with feedings from an eye dropper and progresses through training the kits to live in the wild. But this isn’t the only challenge for Lance. In addition to caring for raccoons, Lance helps his neighbor move through the grieving process, comes to terms with his best friend’s out-of-state move, and copes with his mother’s desire to adopt a baby with special needs. Lance learns a lot and develops a lot of empathy before this story is over. The author provides a lot of details about what goes into raising wild animals and why wild animals shouldn’t be treated as pets. I think any child who is considering becoming a veterinarian, wild life biologist, or zoo keeper would be intrigued by this story.

Any kid who loves animals, especially wild ones, will love Raccoon Summer by Betty Vanderwielen. When his father hits and kills a raccoon that was crossing the road, Lance feels compelled to find the babies she’s left behind. Lance’s father is no raccoon lover; he’s an insurance agent who’s had to settle too many claims caused by raccoon damage. His stepmother wants nothing to do with the little creatures, either, so Lance recruits a neighbor with some wildlife rescue experience to help him with three kits that are so small that their eyes aren’t even open yet. The two begin a program that starts with feedings from an eye dropper and progresses through training the kits to live in the wild. But this isn’t the only challenge for Lance. In addition to caring for raccoons, Lance helps his neighbor move through the grieving process, comes to terms with his best friend’s out-of-state move, and copes with his mother’s desire to adopt a baby with special needs. Lance learns a lot and develops a lot of empathy before this story is over. The author provides a lot of details about what goes into raising wild animals and why wild animals shouldn’t be treated as pets. I think any child who is considering becoming a veterinarian, wild life biologist, or zoo keeper would be intrigued by this story.

Although I didn’t find a date for when the story is set, I’m guessing it’s in the mid1980s, based on the fact that no one has a cell phone, Lance has a land line in his room, they go to a Blockbuster on the weekend, and there’s a really great scene with a Star Wars themed birthday party that only mentions three movies, and the family watches MASH and Star Trek on TV. Some kids might be a befuddled by no cell phones! The more controversial issues, like surrogate parenting and the treatment of special needs children are handled delicately and with a light hand. There is a sweetness and innocence to the book that is refreshing. I’d recommend Raccoon Summer to readers between fourth and sixth grade.

Although I didn’t find a date for when the story is set, I’m guessing it’s in the mid1980s, based on the fact that no one has a cell phone, Lance has a land line in his room, they go to a Blockbuster on the weekend, and there’s a really great scene with a Star Wars themed birthday party that only mentions three movies, and the family watches MASH and Star Trek on TV. Some kids might be a befuddled by no cell phones! The more controversial issues, like surrogate parenting and the treatment of special needs children are handled delicately and with a light hand. There is a sweetness and innocence to the book that is refreshing. I’d recommend Raccoon Summer to readers between fourth and sixth grade.

What is it about pack rats? Here in the mountains where I live, most of us consider pack rats a nuisance the same way Lance's dad thought raccoons were. They have a habit of climbing into the engine blocks of cars and chewing the wires. They root through the attic, scattering scat and chewing the glitter off Christmas decorations. But I guess their peculiar habits make them particularly interesting to young readers. In January I reviewed The Dreaded Cliff, a middle grade novel about a feisty female packrat who goes on an epic journey and saves her clan from a monster who’s taken over their homeland.

What is it about pack rats? Here in the mountains where I live, most of us consider pack rats a nuisance the same way Lance's dad thought raccoons were. They have a habit of climbing into the engine blocks of cars and chewing the wires. They root through the attic, scattering scat and chewing the glitter off Christmas decorations. But I guess their peculiar habits make them particularly interesting to young readers. In January I reviewed The Dreaded Cliff, a middle grade novel about a feisty female packrat who goes on an epic journey and saves her clan from a monster who’s taken over their homeland.

This month, I came across another story about packrats. A Packrat’s Holiday: Thistletoe’s Gift is for younger readers and makes a great read aloud for younger kids and for everyone else. Thistletoe Q. Packrat and his mom are facing a joyless holiday. Times are “tougher ‘n horseshoes and the cupboards are bare. But when three cowboys drive their cattle by, Thistletoe and his cousin Cuz are determined to wrangle some of the vittles for themselves. Author Linda Wilson has written a text that’s filled with enough Westernisms to make this book a read-aloud hit, and Nancy Batra’s black and white illustrations, which cover every page, are cute and filled with details that will keep little eyes busy. While Raccoon Summer was realistic, this sweet book anthropomorphizes the packrats. They speak and wear bits of clothing and eat their feat while sitting around a table. Author’s notes in the back of the book share information about real pack rats and their behavior, the desert of the Southwest, and Western cattle drives. Altogether, this is a fun and informative book that I recommend for readers over the age of five, and listeners of any age.

Jennifer Bohnhoff lives in the mountains east of Albuquerque, New Mexico. She has written a number of books for middle grade readers. Her next book, Where Duty Calls, is historical fiction set in New Mexico during the Civil War, and will be published by Kinkajou Press in June 2022. It is available for preorder in both paperback and ebook here.

Jennifer Bohnhoff lives in the mountains east of Albuquerque, New Mexico. She has written a number of books for middle grade readers. Her next book, Where Duty Calls, is historical fiction set in New Mexico during the Civil War, and will be published by Kinkajou Press in June 2022. It is available for preorder in both paperback and ebook here.

Any kid who loves animals, especially wild ones, will love Raccoon Summer by Betty Vanderwielen. When his father hits and kills a raccoon that was crossing the road, Lance feels compelled to find the babies she’s left behind. Lance’s father is no raccoon lover; he’s an insurance agent who’s had to settle too many claims caused by raccoon damage. His stepmother wants nothing to do with the little creatures, either, so Lance recruits a neighbor with some wildlife rescue experience to help him with three kits that are so small that their eyes aren’t even open yet. The two begin a program that starts with feedings from an eye dropper and progresses through training the kits to live in the wild. But this isn’t the only challenge for Lance. In addition to caring for raccoons, Lance helps his neighbor move through the grieving process, comes to terms with his best friend’s out-of-state move, and copes with his mother’s desire to adopt a baby with special needs. Lance learns a lot and develops a lot of empathy before this story is over. The author provides a lot of details about what goes into raising wild animals and why wild animals shouldn’t be treated as pets. I think any child who is considering becoming a veterinarian, wild life biologist, or zoo keeper would be intrigued by this story.

Any kid who loves animals, especially wild ones, will love Raccoon Summer by Betty Vanderwielen. When his father hits and kills a raccoon that was crossing the road, Lance feels compelled to find the babies she’s left behind. Lance’s father is no raccoon lover; he’s an insurance agent who’s had to settle too many claims caused by raccoon damage. His stepmother wants nothing to do with the little creatures, either, so Lance recruits a neighbor with some wildlife rescue experience to help him with three kits that are so small that their eyes aren’t even open yet. The two begin a program that starts with feedings from an eye dropper and progresses through training the kits to live in the wild. But this isn’t the only challenge for Lance. In addition to caring for raccoons, Lance helps his neighbor move through the grieving process, comes to terms with his best friend’s out-of-state move, and copes with his mother’s desire to adopt a baby with special needs. Lance learns a lot and develops a lot of empathy before this story is over. The author provides a lot of details about what goes into raising wild animals and why wild animals shouldn’t be treated as pets. I think any child who is considering becoming a veterinarian, wild life biologist, or zoo keeper would be intrigued by this story.

Although I didn’t find a date for when the story is set, I’m guessing it’s in the mid1980s, based on the fact that no one has a cell phone, Lance has a land line in his room, they go to a Blockbuster on the weekend, and there’s a really great scene with a Star Wars themed birthday party that only mentions three movies, and the family watches MASH and Star Trek on TV. Some kids might be a befuddled by no cell phones! The more controversial issues, like surrogate parenting and the treatment of special needs children are handled delicately and with a light hand. There is a sweetness and innocence to the book that is refreshing. I’d recommend Raccoon Summer to readers between fourth and sixth grade.

Although I didn’t find a date for when the story is set, I’m guessing it’s in the mid1980s, based on the fact that no one has a cell phone, Lance has a land line in his room, they go to a Blockbuster on the weekend, and there’s a really great scene with a Star Wars themed birthday party that only mentions three movies, and the family watches MASH and Star Trek on TV. Some kids might be a befuddled by no cell phones! The more controversial issues, like surrogate parenting and the treatment of special needs children are handled delicately and with a light hand. There is a sweetness and innocence to the book that is refreshing. I’d recommend Raccoon Summer to readers between fourth and sixth grade.

What is it about pack rats? Here in the mountains where I live, most of us consider pack rats a nuisance the same way Lance's dad thought raccoons were. They have a habit of climbing into the engine blocks of cars and chewing the wires. They root through the attic, scattering scat and chewing the glitter off Christmas decorations. But I guess their peculiar habits make them particularly interesting to young readers. In January I reviewed The Dreaded Cliff, a middle grade novel about a feisty female packrat who goes on an epic journey and saves her clan from a monster who’s taken over their homeland.

What is it about pack rats? Here in the mountains where I live, most of us consider pack rats a nuisance the same way Lance's dad thought raccoons were. They have a habit of climbing into the engine blocks of cars and chewing the wires. They root through the attic, scattering scat and chewing the glitter off Christmas decorations. But I guess their peculiar habits make them particularly interesting to young readers. In January I reviewed The Dreaded Cliff, a middle grade novel about a feisty female packrat who goes on an epic journey and saves her clan from a monster who’s taken over their homeland. This month, I came across another story about packrats. A Packrat’s Holiday: Thistletoe’s Gift is for younger readers and makes a great read aloud for younger kids and for everyone else. Thistletoe Q. Packrat and his mom are facing a joyless holiday. Times are “tougher ‘n horseshoes and the cupboards are bare. But when three cowboys drive their cattle by, Thistletoe and his cousin Cuz are determined to wrangle some of the vittles for themselves. Author Linda Wilson has written a text that’s filled with enough Westernisms to make this book a read-aloud hit, and Nancy Batra’s black and white illustrations, which cover every page, are cute and filled with details that will keep little eyes busy. While Raccoon Summer was realistic, this sweet book anthropomorphizes the packrats. They speak and wear bits of clothing and eat their feat while sitting around a table. Author’s notes in the back of the book share information about real pack rats and their behavior, the desert of the Southwest, and Western cattle drives. Altogether, this is a fun and informative book that I recommend for readers over the age of five, and listeners of any age.

Jennifer Bohnhoff lives in the mountains east of Albuquerque, New Mexico. She has written a number of books for middle grade readers. Her next book, Where Duty Calls, is historical fiction set in New Mexico during the Civil War, and will be published by Kinkajou Press in June 2022. It is available for preorder in both paperback and ebook here.

Jennifer Bohnhoff lives in the mountains east of Albuquerque, New Mexico. She has written a number of books for middle grade readers. Her next book, Where Duty Calls, is historical fiction set in New Mexico during the Civil War, and will be published by Kinkajou Press in June 2022. It is available for preorder in both paperback and ebook here.

Published on April 03, 2022 15:32

March 29, 2022

Civil War Weaponry: Mountain Howitzers

The youngest reenactor at Glorieta. His father told me that this was his first encampment. Last weekend, the 160th anniversary of the Battle of Glorieta Pass was observed. I drove up to Pecos National Historic Site on Saturday morning to witness the observation.

The youngest reenactor at Glorieta. His father told me that this was his first encampment. Last weekend, the 160th anniversary of the Battle of Glorieta Pass was observed. I drove up to Pecos National Historic Site on Saturday morning to witness the observation. The weekend was pretty low key. A group of Union reenactors attended. They put up tents and spend the night. No Confederate reenactors were there.

I was walking up from the parking lot when I heard gun fire. The reenactors gave some black powder displays, but there was no reenactment of the battle. The one and only artillery piece, a mountain howitzer, was going to be fired at noon, but I didn't stay around long enough to hear it.

Fort Union's Mountain Howitzer The New Mexico Artillery Company has several cannons they bring to reenactments. However, the Park Service demands that all cannons brought on to their property are accurate reproductions. Most of the ones used by the Artillery Company have smaller bores than authentic Civil War cannons. Smaller bores are cheaper to fire. The one present this past weekend was a mountain howitzer which was brought down from Fort Union for the day. This replica, like the actual gun, was made of bronze and had a smooth bore. It could fire an explosive shell, a cannon ball, or canister 1,005 yards.

Fort Union's Mountain Howitzer The New Mexico Artillery Company has several cannons they bring to reenactments. However, the Park Service demands that all cannons brought on to their property are accurate reproductions. Most of the ones used by the Artillery Company have smaller bores than authentic Civil War cannons. Smaller bores are cheaper to fire. The one present this past weekend was a mountain howitzer which was brought down from Fort Union for the day. This replica, like the actual gun, was made of bronze and had a smooth bore. It could fire an explosive shell, a cannon ball, or canister 1,005 yards.

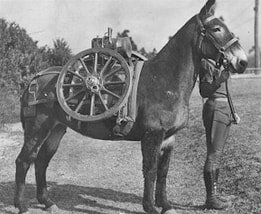

A mule carrying cannon wheels. The mountain howitzer was first created in 1837. The United States Army used it during the Mexican–American War (1847–1848), the American Indian Wars, and during the American Civil War, (1861–1865). It was used primarily in the more rugged parts of the West. It was designed to be lightweight and very portable, even in difficult, mountainous terrain. The carriage design allowed it to be broken down into three loads, that could then be loaded onto a pack animal for transport where other guns could not go. When broken down, the tube could be carried by one horse or mule, the carriage and wheels by another, and ammunition on a third. This made it well suited for Indian fighting and mountain warfare.

A mule carrying cannon wheels. The mountain howitzer was first created in 1837. The United States Army used it during the Mexican–American War (1847–1848), the American Indian Wars, and during the American Civil War, (1861–1865). It was used primarily in the more rugged parts of the West. It was designed to be lightweight and very portable, even in difficult, mountainous terrain. The carriage design allowed it to be broken down into three loads, that could then be loaded onto a pack animal for transport where other guns could not go. When broken down, the tube could be carried by one horse or mule, the carriage and wheels by another, and ammunition on a third. This made it well suited for Indian fighting and mountain warfare..Although mountain howitzers provided artillery support for mobile military forces ion the move through rugged country, their shorter range made them unsuitable for dueling with other heavier field artillery weapons. They were replaced by other guns by the 1870s.

Author Jennifer Bohnhoff writes historical fiction for middle grade readers and adults.

Author Jennifer Bohnhoff writes historical fiction for middle grade readers and adults. Where Duty Calls, the first in a trilogy of novels set in New Mexico during the Civil War, will be published by Kinkajou Press, a division of Artemesia Publishing, in June 2022 and is available for preorder from Amazon or Bookshop.

For class sets or other bulk orders, contact Artemesia Publishing. A teacher's guide will be available this summer from the publisher.

Published on March 29, 2022 23:00

March 23, 2022

Where are the People from Where Duty Calls Buried?

Some of the people in my middle grade novel

Where Duty Calls

are fictitious, and therefore have no grave markers. They were never born, and they will never die as long as readers keep them alive.

But other characters were real people, with lives that began long before I wrote about them - lives that were filled with events that I didn't include in my novels.  William Kemp was a real man, and Confederate records indicate he really died of pneumonia on Friday, February 7, 1862 somewhere on the Jornada del Muerto south of Fort Craig. He was buried by the side of the trail, but his resting place was unmarked and is now unknown. Information about young men who died without heirs is often difficult to track down. In my novel, illustrator Ian Barstow has drawn Kemp's grave to look like this.

William Kemp was a real man, and Confederate records indicate he really died of pneumonia on Friday, February 7, 1862 somewhere on the Jornada del Muerto south of Fort Craig. He was buried by the side of the trail, but his resting place was unmarked and is now unknown. Information about young men who died without heirs is often difficult to track down. In my novel, illustrator Ian Barstow has drawn Kemp's grave to look like this.

Pedro Baca, Raul Atencio’s rich merchant uncle was a real man who lived in Socorro. He was indeed rich, and he was a merchant. Everything else in Where Duty Calls about him is fictitious. He was married, but not to the woman he is married to in my story. By all accounts, he was an upstanding citizen, and is buried in the local church, the same one that I have Raul and his family attend Christmas Eve mass in my novel. Raul, his father, mother and siblings are all fictitious characters. Frederick Wade and John Norvell, who both served with the fictional Jemmy Martin, survived the war and went on to live long and full lives. Their memories, published in newspaper accounts, helped give life to my novel. Both men were characters with great senses of humor, which I tried to impart in the characters I created.

Pedro Baca, Raul Atencio’s rich merchant uncle was a real man who lived in Socorro. He was indeed rich, and he was a merchant. Everything else in Where Duty Calls about him is fictitious. He was married, but not to the woman he is married to in my story. By all accounts, he was an upstanding citizen, and is buried in the local church, the same one that I have Raul and his family attend Christmas Eve mass in my novel. Raul, his father, mother and siblings are all fictitious characters. Frederick Wade and John Norvell, who both served with the fictional Jemmy Martin, survived the war and went on to live long and full lives. Their memories, published in newspaper accounts, helped give life to my novel. Both men were characters with great senses of humor, which I tried to impart in the characters I created.

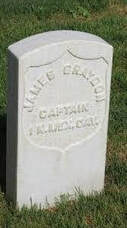

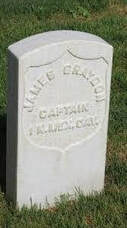

Captain James "Paddy" Graydon died three years after trying to use mules to blow up the Confederate mules and horses (a story that some historians question. This escapade might have been made up by Mark Twain!).

Captain James "Paddy" Graydon died three years after trying to use mules to blow up the Confederate mules and horses (a story that some historians question. This escapade might have been made up by Mark Twain!).

After the war, Graydon was involved in controlling the Mescalero Apaches in southern New Mexico. After Surgeon John Whitlock accused him of needlessly killing a number of braves, the two ended up dueling at Fort Stanton. Graydon was killed, and Whitlock was then killed by Graydon's men. He was buried at Fort Stanton, but twenty-four years later his remains were reinterred at the Federal Cemetery in Santa Fe. Like most Federal Veteran's Cemeteries, the one in Santa Fe contains row upon row of white headstones, giving it a look as uniform as a rank of soldiers. But there are a few exceptions. The most unique marker does not come from the Civil War period, but it deserves notice. It belongs to a Private named Dennis O’Leary, who died at Fort Wingate in 1901. According to local legend, O'Leary himself carved the statue, then committed suicide on the date he had inscribed. However, military records say he died of tuberculosis, a common illness of the period. O'Leary is, of course, not in Where Duty Calls, but his story seems like it has many possibilities.

Where Duty Calls is a novel about the Civil War in New Mexico. Written for middle grade readers, it is the first in a trilogy entitled Rebels Along the Rio Grande, and will be published by Kinkajou Press, a division of Artemesia Publishing, in June 2022. The author, Jennifer Bohnhoff, taught New Mexico history to 7th graders at two different middle schools in central New Mexico. She is a native New Mexican who is fascinated by the state's rich and diverse history.

Where Duty Calls is a novel about the Civil War in New Mexico. Written for middle grade readers, it is the first in a trilogy entitled Rebels Along the Rio Grande, and will be published by Kinkajou Press, a division of Artemesia Publishing, in June 2022. The author, Jennifer Bohnhoff, taught New Mexico history to 7th graders at two different middle schools in central New Mexico. She is a native New Mexican who is fascinated by the state's rich and diverse history.

If you'd like more information about her or her books, you can visit her website or sign up for her email list.

But other characters were real people, with lives that began long before I wrote about them - lives that were filled with events that I didn't include in my novels.

William Kemp was a real man, and Confederate records indicate he really died of pneumonia on Friday, February 7, 1862 somewhere on the Jornada del Muerto south of Fort Craig. He was buried by the side of the trail, but his resting place was unmarked and is now unknown. Information about young men who died without heirs is often difficult to track down. In my novel, illustrator Ian Barstow has drawn Kemp's grave to look like this.

William Kemp was a real man, and Confederate records indicate he really died of pneumonia on Friday, February 7, 1862 somewhere on the Jornada del Muerto south of Fort Craig. He was buried by the side of the trail, but his resting place was unmarked and is now unknown. Information about young men who died without heirs is often difficult to track down. In my novel, illustrator Ian Barstow has drawn Kemp's grave to look like this.

Pedro Baca, Raul Atencio’s rich merchant uncle was a real man who lived in Socorro. He was indeed rich, and he was a merchant. Everything else in Where Duty Calls about him is fictitious. He was married, but not to the woman he is married to in my story. By all accounts, he was an upstanding citizen, and is buried in the local church, the same one that I have Raul and his family attend Christmas Eve mass in my novel. Raul, his father, mother and siblings are all fictitious characters. Frederick Wade and John Norvell, who both served with the fictional Jemmy Martin, survived the war and went on to live long and full lives. Their memories, published in newspaper accounts, helped give life to my novel. Both men were characters with great senses of humor, which I tried to impart in the characters I created.

Pedro Baca, Raul Atencio’s rich merchant uncle was a real man who lived in Socorro. He was indeed rich, and he was a merchant. Everything else in Where Duty Calls about him is fictitious. He was married, but not to the woman he is married to in my story. By all accounts, he was an upstanding citizen, and is buried in the local church, the same one that I have Raul and his family attend Christmas Eve mass in my novel. Raul, his father, mother and siblings are all fictitious characters. Frederick Wade and John Norvell, who both served with the fictional Jemmy Martin, survived the war and went on to live long and full lives. Their memories, published in newspaper accounts, helped give life to my novel. Both men were characters with great senses of humor, which I tried to impart in the characters I created.

Captain James "Paddy" Graydon died three years after trying to use mules to blow up the Confederate mules and horses (a story that some historians question. This escapade might have been made up by Mark Twain!).

Captain James "Paddy" Graydon died three years after trying to use mules to blow up the Confederate mules and horses (a story that some historians question. This escapade might have been made up by Mark Twain!). After the war, Graydon was involved in controlling the Mescalero Apaches in southern New Mexico. After Surgeon John Whitlock accused him of needlessly killing a number of braves, the two ended up dueling at Fort Stanton. Graydon was killed, and Whitlock was then killed by Graydon's men. He was buried at Fort Stanton, but twenty-four years later his remains were reinterred at the Federal Cemetery in Santa Fe. Like most Federal Veteran's Cemeteries, the one in Santa Fe contains row upon row of white headstones, giving it a look as uniform as a rank of soldiers. But there are a few exceptions. The most unique marker does not come from the Civil War period, but it deserves notice. It belongs to a Private named Dennis O’Leary, who died at Fort Wingate in 1901. According to local legend, O'Leary himself carved the statue, then committed suicide on the date he had inscribed. However, military records say he died of tuberculosis, a common illness of the period. O'Leary is, of course, not in Where Duty Calls, but his story seems like it has many possibilities.

Where Duty Calls is a novel about the Civil War in New Mexico. Written for middle grade readers, it is the first in a trilogy entitled Rebels Along the Rio Grande, and will be published by Kinkajou Press, a division of Artemesia Publishing, in June 2022. The author, Jennifer Bohnhoff, taught New Mexico history to 7th graders at two different middle schools in central New Mexico. She is a native New Mexican who is fascinated by the state's rich and diverse history.

Where Duty Calls is a novel about the Civil War in New Mexico. Written for middle grade readers, it is the first in a trilogy entitled Rebels Along the Rio Grande, and will be published by Kinkajou Press, a division of Artemesia Publishing, in June 2022. The author, Jennifer Bohnhoff, taught New Mexico history to 7th graders at two different middle schools in central New Mexico. She is a native New Mexican who is fascinated by the state's rich and diverse history.If you'd like more information about her or her books, you can visit her website or sign up for her email list.

Published on March 23, 2022 07:41

March 15, 2022

Mules in the Civil War

Mule carrying parts of a cannon Mules did much of the heavy hauling for both the Confederate and Union Armies during the American Civil War.

Mule carrying parts of a cannon Mules did much of the heavy hauling for both the Confederate and Union Armies during the American Civil War. They pulled the supply wagons, the limbers and caissons for cannons. They pulled the ambulances. The fearlessness and tenacity that many mules demonstrate made them ideal for the difficult conditions of war.

More than one soldier found them better and more reliable mounts than horses. The bond between a man and his mule could become very strong, indeed.

Both lead characters in Where Duty Calls have connections to mules. To protect his family's mules after they are sold to the Confederate Army, Jemmy joins on as a packer. Raul Atencio uses mules to haul supplies to Fort Craig. On the night before the battle at Valverde Ford, he sells two of his mules to, a Union spy captain named Paddy Graydon, who loads them with ammunition and attempts to goad them into the Confederate lines in an attempt to destroy the Confederate's supply chain. The explosion caused the mules, who were already thirsty, to stampede down to the Rio Grande, where Union soldiers rounded them up. In Hardtack and Coffee: The Unwritten Story of Army Life, Civil War veteran John D. Billings shares the story of another mule stampede. During the night of Oct. 28, 1863, Union General John White Geary and Confederate General James Longstreet were fighting at Wauhatchie, Tennessee. The din of battle unnerved about two hundred mules, who stampeded into a body of Rebels commanded by Wade Hampton. The rebels thought they were being attacked by cavalry and fell back.

Both lead characters in Where Duty Calls have connections to mules. To protect his family's mules after they are sold to the Confederate Army, Jemmy joins on as a packer. Raul Atencio uses mules to haul supplies to Fort Craig. On the night before the battle at Valverde Ford, he sells two of his mules to, a Union spy captain named Paddy Graydon, who loads them with ammunition and attempts to goad them into the Confederate lines in an attempt to destroy the Confederate's supply chain. The explosion caused the mules, who were already thirsty, to stampede down to the Rio Grande, where Union soldiers rounded them up. In Hardtack and Coffee: The Unwritten Story of Army Life, Civil War veteran John D. Billings shares the story of another mule stampede. During the night of Oct. 28, 1863, Union General John White Geary and Confederate General James Longstreet were fighting at Wauhatchie, Tennessee. The din of battle unnerved about two hundred mules, who stampeded into a body of Rebels commanded by Wade Hampton. The rebels thought they were being attacked by cavalry and fell back.To commemorate this incident, one Union soldier penned a poem based on Tennyson's Charge of the Light Brigade. Charge of the mule brigade

Half a mile, half a mile,

Half a mile onward,

Right through the Georgia troops

Broke the two hundred.

“Forward the Mule Brigade!”

“Charge for the Rebs!” they neighed.

Straight for the Georgia troops

Broke the two hundred.

“Forward the Mule Brigade!”

Was there a mule dismayed?

Not when the long ears felt

All their ropes sundered.

Theirs not to make reply,

Theirs not to reason why,

Theirs but to make Rebs fly.

On! to the Georgia troops

Broke the two hundred.

Mules to the right of them,

Mules to the left of them,

Mules behind them

Pawed, neighed, and thundered.

Breaking their own confines,

Breaking through Longstreet's lines

Into the Georgia troops,

Stormed the two hundred.

Wild all their eyes did glare,

Whisked all their tails in air

Scattering the chivalry there,

While all the world wondered.

Not a mule back bestraddled,

Yet how they all skedaddled--

Fled every Georgian,

Unsabred, unsaddled,

Scattered and sundered!

How they were routed there

By the two hundred!

Mules to the right of them,

Mules to the left of them,

Mules behind them

Pawed, neighed, and thundered;

Followed by hoof and head

Full many a hero fled,

Fain in the last ditch dead,

Back from an ass's jaw

All that was left of them,--

Left by the two hundred.

When can their glory fade?

Oh, the wild charge they made!

All the world wondered.

Honor the charge they made!

Honor the Mule Brigade,

Long-eared two hundred! Where Duty Calls, the first in a trilogy of middle grade novels set in New Mexico during the Civil War, is scheduled to be released by Kinkajou Press, a division of Artemesia Publishing in June 2022 and is now available for preorder on Amazon and Bookshop.

Published on March 15, 2022 23:00

March 12, 2022

Trapped and Having Fun: A middle grade book review

I'm not a video game girl; never have been, never will. But kids who are, especially those who are fans of Minecraft should love Scott Charles’ new series, Video Game Elementary.

I'm not a video game girl; never have been, never will. But kids who are, especially those who are fans of Minecraft should love Scott Charles’ new series, Video Game Elementary.In Trapped in Class, Book 1 of the Video Game Elementary series,. Connor is a fourth grader at Video Game Elementary, an online elementary school built inside a fully immersive virtual reality video game. It's kind of a mash-up between Hogwarts and Tron, where kids become avatars while their physical bodies stay elsewhere. I'm not clear on how that happens, but I bet every middle grade reader out there will grasp it better than I do.

On the day in which the story is set, Connor’s watching the clock, waiting for school to end so he can go to his first practice with the Swords Team. Suddenly there’s a strange hiss, bleep, crack, and the world fades into white. The next thing Connor knows, it’s morning again. Like some weird, middle school version of Groundhog’s Day, the day has restarted. Stuck in a time loop, Connor must fight Fanged Slime, Vampire Mold, and other monsters to keep the school’s power crystals from being destroyed. Luckily, he has a school custodian, a friend named Glitch, a girl who’s very good at hacking the system, and a cleaning ghost with an attitude to help him.

This book is easy to read and action packed. It should be a great hit with kids who’d rather hold a game controller than a book

In an endless loop of her own, Jennifer Bohnhoff taught regular, body-in-class middle school for years. She is now staying home and writing for middle grade and adult readers. Her next book, Where Duty Calls, is the first in a trilogy for middle grade readers about the Civil War in New Mexico, and will be published in June 2022.

In an endless loop of her own, Jennifer Bohnhoff taught regular, body-in-class middle school for years. She is now staying home and writing for middle grade and adult readers. Her next book, Where Duty Calls, is the first in a trilogy for middle grade readers about the Civil War in New Mexico, and will be published in June 2022.

Published on March 12, 2022 23:00

March 8, 2022

The Punitive Expedition Against Pancho Villa

The clock at the Columbus train station, stopped at the time of the attack by a bullet. It is now in the museum at Pancho Villa State Park. Today marks the 106th anniversary of Pancho Villa's raid on Columbus, New Mexico. On March 9, 1916, at approximately 4:00 am, a group of just under 500 Mexican revolutionaries attacked the sleeping town while their leader, General Francisco “Pancho” Villa, watched from a nearby hill. The attack was the first and only ground invasion of the continental United States since the War of 1812. Ten American civilians and eight U.S. soldiers from the adjacent Camp Furlong lost their lives.

The clock at the Columbus train station, stopped at the time of the attack by a bullet. It is now in the museum at Pancho Villa State Park. Today marks the 106th anniversary of Pancho Villa's raid on Columbus, New Mexico. On March 9, 1916, at approximately 4:00 am, a group of just under 500 Mexican revolutionaries attacked the sleeping town while their leader, General Francisco “Pancho” Villa, watched from a nearby hill. The attack was the first and only ground invasion of the continental United States since the War of 1812. Ten American civilians and eight U.S. soldiers from the adjacent Camp Furlong lost their lives.The attack came after a long period of Mexican political unrest and may have been caused by Villa's frustration that President Woodrow Wilson and the American government had chosen to recognize a political rival, Venustiano Carranza, and help him win the election and become President of Mexico. Villa, who had been supported by the U.S. in the past, was also desperate supplies for his beleaguered army and may have thought that Columbus and the nearby Army camp would be a good place to get what he needed.

Much of Columbus burned to the ground during Villa's raid. Public Domain

Much of Columbus burned to the ground during Villa's raid. Public Domain

In response, Wilson ordered a punitive expedition into Mexico to capture Villa. General John J. Pershing began gathering troops at Camp Furlong (sometimes called Camp Columbus). Pershing planned a two-pronged attack. The quicker force, of mostly soldiers on horseback, went south from the village of Hachita, in New Mexico's bootheel. The slower force, which included wagons and trucks filled with gear and supplies, went south directly from Columbus.

In response, Wilson ordered a punitive expedition into Mexico to capture Villa. General John J. Pershing began gathering troops at Camp Furlong (sometimes called Camp Columbus). Pershing planned a two-pronged attack. The quicker force, of mostly soldiers on horseback, went south from the village of Hachita, in New Mexico's bootheel. The slower force, which included wagons and trucks filled with gear and supplies, went south directly from Columbus.By April 8th, General Pershing's force of over six thousand had traveled four hundred miles into Mexico. There they established a base in the town of Colonia Dublan. The U.S. Army had never before attempted anything of this magnitude, and the logistics of supplying Camp Dublan proved difficult.