Jennifer Bohnhoff's Blog, page 15

December 19, 2022

Christmas Nuts in Bastogne

Nuts, Bastogne, and Christmas. Say these three words, and most World War II trivia fans will connect them to Brigadier General Anthony McAuliffe and the Battle of the Bulge. But truth can be stranger than fiction, and the connection goes much farther back than most people know.

Since the 18th century, the Belgian city of Bastogne has had a Nuts Fair during December. Farmhands, cowherds and shepherds in the region used to be employed by landowners for one-year periods that ended eight days before Christmas. Hoping to get contracts for the coming year, these workers came to Bastogne to attend the last market of the year. If they were hired or rehired, they’d buy sugary breads and nuts to celebrate the fact that their livelihood was ensured for another year. Lieutenant Hellmuth Henke Nuts and Bastogne became even more connected because of a comment made by an American commander during the Battle of the Bulge, which began on December 16, 1944. The massive counterattack in the heavily wooded, snowed-covered Ardennes was Nazi Germany’s last attempt to dislodge the advancing Allied forces. The Belgian town of Bastogne became the center of intense fighting because the seven highways that coursed through it made it strategically important. By December 21, the city was surrounded by German forces.

Lieutenant Hellmuth Henke Nuts and Bastogne became even more connected because of a comment made by an American commander during the Battle of the Bulge, which began on December 16, 1944. The massive counterattack in the heavily wooded, snowed-covered Ardennes was Nazi Germany’s last attempt to dislodge the advancing Allied forces. The Belgian town of Bastogne became the center of intense fighting because the seven highways that coursed through it made it strategically important. By December 21, the city was surrounded by German forces.

On the morning of December 22nd, four German soldiers waving a white flag approached the lines to the south of town. The two officers, Major Wagner of the 47th Panzer Corps and Lieutenant Hellmuth Henke of the elite Panzer Lehr Division, wore long overcoats and shiny boots. Henke carried a briefcase under his arm, and declared in English that he had a written message for the American commander in Bastogne were carrying blindfolds that they were willing to put on in order to be brought into headquarters. The two enlisted German soldiers who’d accompanied Wagner and Henke were left behind with American soldiers, while Wagner and Henke were brought forward. Since the 101st “Screaming Eagles” Airborne Division was defending the town of Bastogne, Wagner and Henke’s message should have gone to their commander, Major General Maxwell D. Taylor. However, Taylor was at a staff conference in the United States when the Battle of the Bulge began, and Brigadier General Anthony McAuliffe, normally only in charge of the division’s artillery, had taken his place. McAuliffe was sleeping in his quarters right next to the headquarters when a Lieutenant Colonel woke him.

“The Germans have sent some people forward to take our surrender” said, Lieutenant Colonel Ned Moore.

McAuliffe muttered “Aw, nuts!”

The written message that Henke handed over consisted of two typewritten sheets, one in German, the other an English translation. The diacritical marks above certain German vowels were missing and written in by hand, showing that the Germans had used an English typewriter. It read:

At first, the Germans did not understand what the message meant. When they finally did understand, they stormed off.

At first, the Germans did not understand what the message meant. When they finally did understand, they stormed off.

“Nuts!” became the rallying cry for the beleaguered defenders. It raised their morale and gave them hope. Luckily for Bastogne, the German Corps Commander General Heinrich von Lüttwitz decided to circumnavigate Bastogne, and concentrate his forces on Bayerlein.

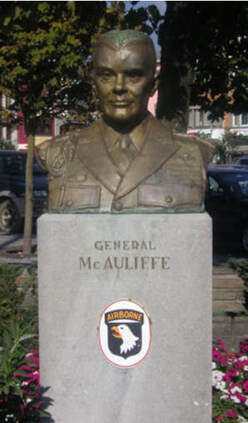

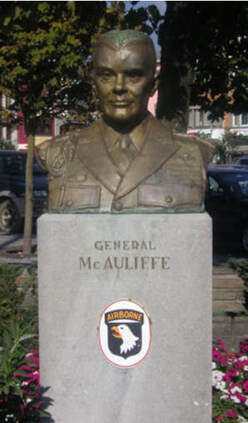

For his actions, McAuliffe received the Distinguished Service Cross from General George S. Patton. Today, there is a statue of him in the town square, and every year a nut-throwing ceremony celebrates the city’s rescue. Patton decorating McAuliffe with the Distinguished Service Cross (Photo: U.S. Army)

Patton decorating McAuliffe with the Distinguished Service Cross (Photo: U.S. Army)

Jennifer Bohnhoff is an author of historical fiction and a former history teacher. Her novel Code: Elephants on the Moon is the story of a young French girl who discovers that nothing in her little town in Normandy is what she'd believed it to be. As D-Day approaches, she must make some decisions that could mean life or death for many. This YA novel is suitable for older children and adults.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is an author of historical fiction and a former history teacher. Her novel Code: Elephants on the Moon is the story of a young French girl who discovers that nothing in her little town in Normandy is what she'd believed it to be. As D-Day approaches, she must make some decisions that could mean life or death for many. This YA novel is suitable for older children and adults.

Since the 18th century, the Belgian city of Bastogne has had a Nuts Fair during December. Farmhands, cowherds and shepherds in the region used to be employed by landowners for one-year periods that ended eight days before Christmas. Hoping to get contracts for the coming year, these workers came to Bastogne to attend the last market of the year. If they were hired or rehired, they’d buy sugary breads and nuts to celebrate the fact that their livelihood was ensured for another year.

Lieutenant Hellmuth Henke Nuts and Bastogne became even more connected because of a comment made by an American commander during the Battle of the Bulge, which began on December 16, 1944. The massive counterattack in the heavily wooded, snowed-covered Ardennes was Nazi Germany’s last attempt to dislodge the advancing Allied forces. The Belgian town of Bastogne became the center of intense fighting because the seven highways that coursed through it made it strategically important. By December 21, the city was surrounded by German forces.

Lieutenant Hellmuth Henke Nuts and Bastogne became even more connected because of a comment made by an American commander during the Battle of the Bulge, which began on December 16, 1944. The massive counterattack in the heavily wooded, snowed-covered Ardennes was Nazi Germany’s last attempt to dislodge the advancing Allied forces. The Belgian town of Bastogne became the center of intense fighting because the seven highways that coursed through it made it strategically important. By December 21, the city was surrounded by German forces.On the morning of December 22nd, four German soldiers waving a white flag approached the lines to the south of town. The two officers, Major Wagner of the 47th Panzer Corps and Lieutenant Hellmuth Henke of the elite Panzer Lehr Division, wore long overcoats and shiny boots. Henke carried a briefcase under his arm, and declared in English that he had a written message for the American commander in Bastogne were carrying blindfolds that they were willing to put on in order to be brought into headquarters. The two enlisted German soldiers who’d accompanied Wagner and Henke were left behind with American soldiers, while Wagner and Henke were brought forward. Since the 101st “Screaming Eagles” Airborne Division was defending the town of Bastogne, Wagner and Henke’s message should have gone to their commander, Major General Maxwell D. Taylor. However, Taylor was at a staff conference in the United States when the Battle of the Bulge began, and Brigadier General Anthony McAuliffe, normally only in charge of the division’s artillery, had taken his place. McAuliffe was sleeping in his quarters right next to the headquarters when a Lieutenant Colonel woke him.

“The Germans have sent some people forward to take our surrender” said, Lieutenant Colonel Ned Moore.

McAuliffe muttered “Aw, nuts!”

The written message that Henke handed over consisted of two typewritten sheets, one in German, the other an English translation. The diacritical marks above certain German vowels were missing and written in by hand, showing that the Germans had used an English typewriter. It read:

“They want to surrender?” McAuliffe, who was still groggy from sleep, asked. When he was told that the Germans were demanding that the Americans surrender, McAuliffe threw the paper on the floor and said "Us surrender, aw nuts!" Wagner and Henke, who were still waiting in blindfolds nearby, demanded a formal written response to their message. The one they received said:

"December 22nd 1944

To the U.S.A. Commander of the encircled town of Bastogne.

The fortune of war is changing. This time the U.S.A. forces in and near Bastogne have been encircled by strong German armored units. More German armored units have crossed the river Ourthe near Ortheuville, have taken Marche and reached St. Hubert by passing through Hompre-Sibret-Tillet.

Libramont is in German hands.

There is only one possibility to save the encircled

U.S.A troops from total annihilation: that is the honorable

surrender of the encircled town. In order to think it over

a term of two hours will be granted beginning with the

presentation of this note.

If this proposal should be rejected one German Artillery Corps and six heavy A. A. Battalions are ready

to annihilate the U.S.A. troops in and near Bastogne. The order for firing will be given immediately after this two hours' term.

All the serious civilian losses caused by this artillery fire would not correspond with the wellknown American humanity.

The German Commander."

"December 22, 1944

To the German Commander,

N U T S !

The American Commander"

At first, the Germans did not understand what the message meant. When they finally did understand, they stormed off.

At first, the Germans did not understand what the message meant. When they finally did understand, they stormed off. “Nuts!” became the rallying cry for the beleaguered defenders. It raised their morale and gave them hope. Luckily for Bastogne, the German Corps Commander General Heinrich von Lüttwitz decided to circumnavigate Bastogne, and concentrate his forces on Bayerlein.

For his actions, McAuliffe received the Distinguished Service Cross from General George S. Patton. Today, there is a statue of him in the town square, and every year a nut-throwing ceremony celebrates the city’s rescue.

Patton decorating McAuliffe with the Distinguished Service Cross (Photo: U.S. Army)

Patton decorating McAuliffe with the Distinguished Service Cross (Photo: U.S. Army)

Jennifer Bohnhoff is an author of historical fiction and a former history teacher. Her novel Code: Elephants on the Moon is the story of a young French girl who discovers that nothing in her little town in Normandy is what she'd believed it to be. As D-Day approaches, she must make some decisions that could mean life or death for many. This YA novel is suitable for older children and adults.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is an author of historical fiction and a former history teacher. Her novel Code: Elephants on the Moon is the story of a young French girl who discovers that nothing in her little town in Normandy is what she'd believed it to be. As D-Day approaches, she must make some decisions that could mean life or death for many. This YA novel is suitable for older children and adults.

Published on December 19, 2022 08:51

December 9, 2022

Away in the Manger with Cowboys and Soldiers

Years ago, I bought a manger scene at an after Christmas sale. It was one of the best purchases I ever made. The figures in my nativity set are made out of a rubbery plastic, which means that my three sons, and now my grandchildren have been able to play with them over the years. This has given me the chance to tell and retell the Christmas story to them. They know the story of the three kings, and he herald angel (not Harold the Angel, as one used to think.) and of the shepherds watching their flocks by night. But over the years, our little scene has attracted a few extra players.

Years ago, I bought a manger scene at an after Christmas sale. It was one of the best purchases I ever made. The figures in my nativity set are made out of a rubbery plastic, which means that my three sons, and now my grandchildren have been able to play with them over the years. This has given me the chance to tell and retell the Christmas story to them. They know the story of the three kings, and he herald angel (not Harold the Angel, as one used to think.) and of the shepherds watching their flocks by night. But over the years, our little scene has attracted a few extra players.

Many depictions of Christ's birth have an angel or two who watches over the newborn. Having three sons, one who was interested in the military, my nativity scene had a more earthly guard. For years, a little green army man sniper lay face down on the roof, watching the distance for approaching danger. Sometime in the past decade, he went off duty and was replaced first by one green army man, who seemed to be signaling everyone to come and see the Christ child, then by a second khaki colored one.

Many depictions of Christ's birth have an angel or two who watches over the newborn. Having three sons, one who was interested in the military, my nativity scene had a more earthly guard. For years, a little green army man sniper lay face down on the roof, watching the distance for approaching danger. Sometime in the past decade, he went off duty and was replaced first by one green army man, who seemed to be signaling everyone to come and see the Christ child, then by a second khaki colored one.

Sometime after I moved from the city, another character joined the scene. For the past five years or so, we've had a cowboy to watch after the cow and donkey in the manger. He is a good natured chap, with a smile always on his face. I think he does a good job of mucking out the stalls, for I've never smelled anything coming from them. Now that I have granddaughters, Jesus sometimes finds that his humble manger has been transported to the tropics and is surrounded by flowers. You'll note that the sheep were banished to the back forty so they wouldn't eat the greenery.

Sometime after I moved from the city, another character joined the scene. For the past five years or so, we've had a cowboy to watch after the cow and donkey in the manger. He is a good natured chap, with a smile always on his face. I think he does a good job of mucking out the stalls, for I've never smelled anything coming from them. Now that I have granddaughters, Jesus sometimes finds that his humble manger has been transported to the tropics and is surrounded by flowers. You'll note that the sheep were banished to the back forty so they wouldn't eat the greenery.  How about your house? Do you have a nativity scene that comes out this time of year? I'd love to see it! Jennifer Bohnhoff is the author of several novels for adults and children. You can read more about her and her books at her website.

How about your house? Do you have a nativity scene that comes out this time of year? I'd love to see it! Jennifer Bohnhoff is the author of several novels for adults and children. You can read more about her and her books at her website.

Published on December 09, 2022 15:13

November 29, 2022

Crossing the Alps: Reality vs. Propaganda

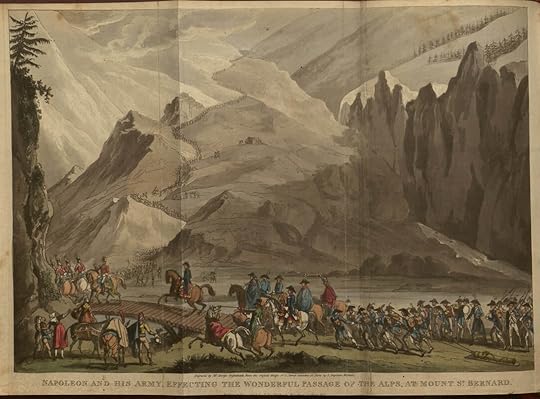

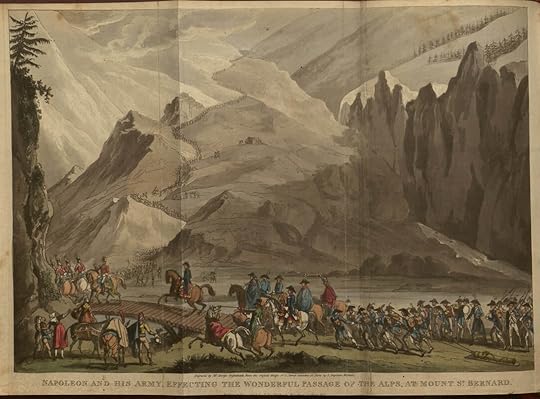

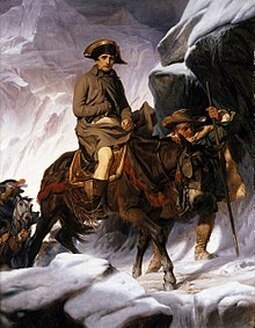

When Napoleon Bonaparte crossed the Alps to push the Austrians out of Italy in the spring of 1800, he was determined that the world know that this crossing put him on a footing with the world’s most renowned generals. Hannibal Barca, the great Carthaginian general, had crossed in 218 BC to attack the Romans. Charlemagne, the great Frankish king who became the first Holy Roman Emperor, did so in 772 AD. Now that Napoleon was to add this accomplishment to his list, he commissioned his favorite painted, Jacques-Louis David, to commemorate the event. David did so in his five versions of Napoleon Crossing the Alps, paintings that remains instantly recognizable the world over. But what Napoleon wanted and what David provided, was not in any way historically accurate. Instead, it is propaganda, more representative of Napoleon’s character and goals. David didn't paint what Napoleon looked like as he cross the Alps. He painted what Napoleon wanted everyone to think he looked like: a man who could control France and the world as easily as he could control -- with just one hand. -- a rearing horse.

In the original version, which is hung at Malmaison, a very young-looking Bonaparte wears an orange cloak and rides a black and white piebald horse. The Charlottenburg shows Napoleon with a slight smile, wearing a red cloak and mounted on a chestnut horse. There are two versions hung at Versailles, the first shows a stern-looking Napoleon riding a dappled grey horse, while the second shows an older Napoleon, with shorter hair wearing an orangy-red cloak and mounted on a black and white horse. A final version, from the Belvedere, is almost identical to the first Versailles version. In all versions, the horse is rearing and Napoleon is pointing, guiding his men over difficult pass. Behind the horse and rider, there is a small view of soldiers struggling to get their cannons over the pass. The sky is stormy and dark. What Napoleon wanted and what David provided, was not in any way historically accurate. Instead, it is propaganda, more representative of Napoleon’s character and goals. Not even the face in David’s portraits was drawn from life because the fidgety and impatient Bonaparte had refused to sit still for the painter.

In one account, David asks Napoleon to pose and he answers “Sit? For what good? Do you think that the great men of Antiquity for whom we have images sat?”

“But Citizen First Consul,” David responded, “I am painting you for your century, for the men who have seen you, who know you, they will want to find a resemblance.”

“A resemblance? It isn't the exactness of the features, a wart on the nose which gives the resemblance. It is the character that dictates what must be painted...Nobody knows if the portraits of the great men resemble them, it is enough that their genius lives there.”

After failing to persuade Napoleon to sit still, David copied the features of a bust of the First Consul. To get the posture correctly, David had his son perch on top a ladder.

Look in the lower right hand corner, where men are pulling a cannon barrel. But it is not just Napoleon’s face that is inaccurate. The trail over the Grand Saint Bernard Pass is so narrow, steep, and rocky that wheeled conveyances, including cannons, could not negotiate it. The army took apart the cannon and their carriage in Bourg-Saint-Pierre, the highest village up the northern side of the pass. Tree trunks were hollowed out, the cannon barrels placed inside them, then slings were made so that 100 men could carry each cannon barrel. Other men carried the disassembled carriages, and other men carried the wheels.

Look in the lower right hand corner, where men are pulling a cannon barrel. But it is not just Napoleon’s face that is inaccurate. The trail over the Grand Saint Bernard Pass is so narrow, steep, and rocky that wheeled conveyances, including cannons, could not negotiate it. The army took apart the cannon and their carriage in Bourg-Saint-Pierre, the highest village up the northern side of the pass. Tree trunks were hollowed out, the cannon barrels placed inside them, then slings were made so that 100 men could carry each cannon barrel. Other men carried the disassembled carriages, and other men carried the wheels.

Records indicate that Napoleon did not lead his men over the pass. Instead, General Maréscot led the army while Bonaparte followed after them by several days. By the time he crossed, the sky was sunny and the weather calm, although it remained cold and the ground covered with snow.

Finally, Napoleon Bonaparte was not riding any of the horses depicted in the various versions of David’s paintings. Because of the treacherous conditions, he was riding a much mor surefooted mule, and the mule was being led by an alpine guide named Pierre-Nicolas Dorsaz.

Dorsaz later related that the mule slipped during the ascent into the mountains. Napoleon would have fallen over a precipice had Dorsaz not been walking between the mule and the edge of the track. Although Napoleon showed no emotion at the time, he began questioning his guide about his life in the village of Bourg-Saint-Pierre. Dorsaz told Napoleon that his dream was to have a small farm, a field and cow. When the First Consul asked about the normal fee for alpine guides, Dorsaz told him that guides were usually paid three francs. Napoleon then ordered that Dorsaz be paid 60 Louis, or 1200 francs for his "zeal and devotion to his task" during the crossing of the Alps. Local legend says that Dorsaz used the money to buy his farm and marry Eléonore Genoud, the girl he loved.

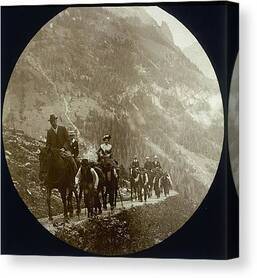

In 1848 Arthur George, the 3rd Earl of Onslow, was visiting the Louvre with Paul Delaroche, the painter who had painted Charlemagne Crossing the Alps. George commissioned Delaroche to produce a more accurate version of Napoleon crossing the Alps, which was completed in 1850. While much more historically accurate, this depiction is nowhere as heroic or romantic. Jennifer Bohnhoff is currently working on a novel set in the Great Saint Bernard Pass in the years 1799 and 1800. Napoleon has a tiny cameo appearance in her story, but Dorsaz the mountain guide shows up in three different scenes. For more information about her and her other books, see her website.

In 1848 Arthur George, the 3rd Earl of Onslow, was visiting the Louvre with Paul Delaroche, the painter who had painted Charlemagne Crossing the Alps. George commissioned Delaroche to produce a more accurate version of Napoleon crossing the Alps, which was completed in 1850. While much more historically accurate, this depiction is nowhere as heroic or romantic. Jennifer Bohnhoff is currently working on a novel set in the Great Saint Bernard Pass in the years 1799 and 1800. Napoleon has a tiny cameo appearance in her story, but Dorsaz the mountain guide shows up in three different scenes. For more information about her and her other books, see her website.

In the original version, which is hung at Malmaison, a very young-looking Bonaparte wears an orange cloak and rides a black and white piebald horse. The Charlottenburg shows Napoleon with a slight smile, wearing a red cloak and mounted on a chestnut horse. There are two versions hung at Versailles, the first shows a stern-looking Napoleon riding a dappled grey horse, while the second shows an older Napoleon, with shorter hair wearing an orangy-red cloak and mounted on a black and white horse. A final version, from the Belvedere, is almost identical to the first Versailles version. In all versions, the horse is rearing and Napoleon is pointing, guiding his men over difficult pass. Behind the horse and rider, there is a small view of soldiers struggling to get their cannons over the pass. The sky is stormy and dark. What Napoleon wanted and what David provided, was not in any way historically accurate. Instead, it is propaganda, more representative of Napoleon’s character and goals. Not even the face in David’s portraits was drawn from life because the fidgety and impatient Bonaparte had refused to sit still for the painter.

In one account, David asks Napoleon to pose and he answers “Sit? For what good? Do you think that the great men of Antiquity for whom we have images sat?”

“But Citizen First Consul,” David responded, “I am painting you for your century, for the men who have seen you, who know you, they will want to find a resemblance.”

“A resemblance? It isn't the exactness of the features, a wart on the nose which gives the resemblance. It is the character that dictates what must be painted...Nobody knows if the portraits of the great men resemble them, it is enough that their genius lives there.”

After failing to persuade Napoleon to sit still, David copied the features of a bust of the First Consul. To get the posture correctly, David had his son perch on top a ladder.

Look in the lower right hand corner, where men are pulling a cannon barrel. But it is not just Napoleon’s face that is inaccurate. The trail over the Grand Saint Bernard Pass is so narrow, steep, and rocky that wheeled conveyances, including cannons, could not negotiate it. The army took apart the cannon and their carriage in Bourg-Saint-Pierre, the highest village up the northern side of the pass. Tree trunks were hollowed out, the cannon barrels placed inside them, then slings were made so that 100 men could carry each cannon barrel. Other men carried the disassembled carriages, and other men carried the wheels.

Look in the lower right hand corner, where men are pulling a cannon barrel. But it is not just Napoleon’s face that is inaccurate. The trail over the Grand Saint Bernard Pass is so narrow, steep, and rocky that wheeled conveyances, including cannons, could not negotiate it. The army took apart the cannon and their carriage in Bourg-Saint-Pierre, the highest village up the northern side of the pass. Tree trunks were hollowed out, the cannon barrels placed inside them, then slings were made so that 100 men could carry each cannon barrel. Other men carried the disassembled carriages, and other men carried the wheels. Records indicate that Napoleon did not lead his men over the pass. Instead, General Maréscot led the army while Bonaparte followed after them by several days. By the time he crossed, the sky was sunny and the weather calm, although it remained cold and the ground covered with snow.

Finally, Napoleon Bonaparte was not riding any of the horses depicted in the various versions of David’s paintings. Because of the treacherous conditions, he was riding a much mor surefooted mule, and the mule was being led by an alpine guide named Pierre-Nicolas Dorsaz.

Dorsaz later related that the mule slipped during the ascent into the mountains. Napoleon would have fallen over a precipice had Dorsaz not been walking between the mule and the edge of the track. Although Napoleon showed no emotion at the time, he began questioning his guide about his life in the village of Bourg-Saint-Pierre. Dorsaz told Napoleon that his dream was to have a small farm, a field and cow. When the First Consul asked about the normal fee for alpine guides, Dorsaz told him that guides were usually paid three francs. Napoleon then ordered that Dorsaz be paid 60 Louis, or 1200 francs for his "zeal and devotion to his task" during the crossing of the Alps. Local legend says that Dorsaz used the money to buy his farm and marry Eléonore Genoud, the girl he loved.

In 1848 Arthur George, the 3rd Earl of Onslow, was visiting the Louvre with Paul Delaroche, the painter who had painted Charlemagne Crossing the Alps. George commissioned Delaroche to produce a more accurate version of Napoleon crossing the Alps, which was completed in 1850. While much more historically accurate, this depiction is nowhere as heroic or romantic. Jennifer Bohnhoff is currently working on a novel set in the Great Saint Bernard Pass in the years 1799 and 1800. Napoleon has a tiny cameo appearance in her story, but Dorsaz the mountain guide shows up in three different scenes. For more information about her and her other books, see her website.

In 1848 Arthur George, the 3rd Earl of Onslow, was visiting the Louvre with Paul Delaroche, the painter who had painted Charlemagne Crossing the Alps. George commissioned Delaroche to produce a more accurate version of Napoleon crossing the Alps, which was completed in 1850. While much more historically accurate, this depiction is nowhere as heroic or romantic. Jennifer Bohnhoff is currently working on a novel set in the Great Saint Bernard Pass in the years 1799 and 1800. Napoleon has a tiny cameo appearance in her story, but Dorsaz the mountain guide shows up in three different scenes. For more information about her and her other books, see her website.

Published on November 29, 2022 23:00

November 22, 2022

Crossing the Alps: Napoleon and his Predecessors

The Alps are intimidating mountains. Steep and rocky, they are such a difficult place through which to transport the heavy equipment of war, and such a dangerous place for armies, that they’ve been considered nigh well impenetrable. Few generals have tried to maneuver their troops through the Alps. Those who have done so are famous for it.

The Alps are intimidating mountains. Steep and rocky, they are such a difficult place through which to transport the heavy equipment of war, and such a dangerous place for armies, that they’ve been considered nigh well impenetrable. Few generals have tried to maneuver their troops through the Alps. Those who have done so are famous for it.Hannibal Barca, the great Carthaginian general, did it in 218 BC. He managed to not only bring his soldiers through, but what at the time was the ultimate war weapon: elephants. Credited as saying “We will find a way, and if there is no way, we will make a way,” Hannibal left behind a bronze stele that stated he brought 20,000 infantry, 6,000 cavalry, and 37 elephants over the Alps when he arrived in Italy during the Second Punic War. Although pro-Roman writers including Polybius and Livy claimed that Hannibal lost half of his men while coming through Great Saint Bernard Pass, modern historians think otherwise. They suggest that a little as 500 men succumbed to the cold, the hazards of avalanches, and from attacks by local tribes. They also believe that the general passed through the Lesser Saint Bernard Pass, which is further to the west Charlemagne, the great Frankish king who united Europe, also crossed the Alps. In 772 AD, Pope Adrian I begged Charlemagne to chase the Lombards out of Papal towns in Northern Italy. Charlemagne crossed through the Alps using the Great Saint Bernard Pass. Although he brought nothing so big as an elephant, he did have an army of between 10,000 and 40,000 troops. The chroniclers of the time hailed Charlemagne as the new Hannibal. He besieged the Lombards in Pavia, eventually destroying their control of Italy and giving power back to the papacy. This earned him the title of King of the Lombards.

Charlemagne Crossing the Alps to Defeat the Lombards, by Paul Delaroche Napoleon Bonaparte crossed the Alps in 1800. He had just returned from his military campaign in Egypt when he found that the Austrians had retaken Italy. He decided to launch a surprise assault on the Austrian army and chose the shortest route, which went through Great Saint Bernard Pass, so that his army of over forty thousand men, his heavy field artillery, and his baggage trains could reach Italy before his enemy knew they were coming.

Charlemagne Crossing the Alps to Defeat the Lombards, by Paul Delaroche Napoleon Bonaparte crossed the Alps in 1800. He had just returned from his military campaign in Egypt when he found that the Austrians had retaken Italy. He decided to launch a surprise assault on the Austrian army and chose the shortest route, which went through Great Saint Bernard Pass, so that his army of over forty thousand men, his heavy field artillery, and his baggage trains could reach Italy before his enemy knew they were coming.Since the pass was too steep and rocky for wheeled vehicles, the artillery was dismantled at Bourg St. Pierre, the last settlement on the Swiss side of the pass. Chests, specially made in the nearby villages of Villeneuve and Orsires were packed with the ammunition and iron fittings and loaded on to mules. Teams of soldiers carried the disassembled caissons and the gun barrels. The Army began their passage on May 15. The passage took five days to reach the hospice at the top of the pass, where the prior, father Berenfaller, offered Napoleon a meal in the great reception hall while the monks distributed food to his troops.

On the other side of the St. Bernard Pass, the artillery was reassembled in the village of Etroubles then moved with the Army into the Aosta valley, where they had to lay siege to Fort de Bard, losing the element of surprise. Eventually, the French beat the Austrians at Marengo on June 14.

Napoleon was determined that people made the connection between himself, Hannibal and Charlemagne. The painting that Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon’s favorite painter, created to commemorate the event features the names of Napoleon’s two famous predecessors carved into the rocks beneath Napoleon’s horse’s hooves. David wanted to make it clear that Napoleon was not just following in the footsteps of his predecessors, but joining them on the list of generals who had conquered the Alpine crossing. The painting, which remains so popular and recognizable today that it is an important icon in popular culture, was reproduced several times, with variations in color and detail, but all of the versions show the French general astride a rearing horse, with the artillery struggling uphill in the background. And while the image is a noble one, it is not at all historically accurate, an explanation of which must wait for another blog post.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a writer who lives high in the mountains of central New Mexico. This summer she hiked around Mont Blanc, crossing the French, Swiss, and Italian borders, and rode a bus through Saint Bernard Pass. The scenery inspired her, and she's now writing a first draft of an historical novel for middle grade readers set in the year that Napoleon crossed the Alps. You can read more about her and her books on her website..

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a writer who lives high in the mountains of central New Mexico. This summer she hiked around Mont Blanc, crossing the French, Swiss, and Italian borders, and rode a bus through Saint Bernard Pass. The scenery inspired her, and she's now writing a first draft of an historical novel for middle grade readers set in the year that Napoleon crossed the Alps. You can read more about her and her books on her website..

Published on November 22, 2022 23:00

November 15, 2022

The Great and Little Passes of Saint Bernard

There are two passes in the southern Alps which bear the name Saint. Bernard, and they are often confused with each other.

The Great Saint Bernard Pass is the lowest pass lying on the ridge between the two highest mountains of the Alps, Mont Blanc and Monte Rosa. At 8,100 ft high, it connects Martigny in the Swiss canton of Valais, with Aosta, Italy. The Little Saint Bernard Pass, 7,178 ft high, straddles the French–Italian border and connects Savoie, France to the Aosta Valley. Both passes have been used since prehistoric times. At the summit, the road through Little St Bernard Pass bisects a stone circle that might have been a ceremonial site for the Tarentaisians, a Celtic tribe, during the period from c. 725 BC to 450 BC. The road has taken the place of a standing stone that stood in its center. While there are indications that the Great St Bernard Pass has been used since at least the bronze age, the first historical reference to it refers to its use by Boii and Lingones, Celtic tribes who crossed it during their invasion of Italy in 390 BC.

The stone ring at the top of Little Saint Bernard Pass. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The stone ring at the top of Little Saint Bernard Pass. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Publisher New York Ward, Lock, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Writers in the 1st century BC called the Great St Bernard Pass the Punic Pass. It may be that they misinterpreted the Celtic word pen, meaning head or summit, and wrongly believed that it was the pass that the Carthaginian general Hannibal used while crossing with his elephants into Italy in 218 BC.

Publisher New York Ward, Lock, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Writers in the 1st century BC called the Great St Bernard Pass the Punic Pass. It may be that they misinterpreted the Celtic word pen, meaning head or summit, and wrongly believed that it was the pass that the Carthaginian general Hannibal used while crossing with his elephants into Italy in 218 BC.

While no one is sure of the exact route that Hannibal used, based on the limited descriptions written by classical authors, many a full century after the event, most historians now believe that Hannibal used the Little Saint Bernard Pass. Wanting to find a shorter route between Italy and Gaul than the commonly used coastal route, Julius Caesar tried to secure the Great Saint Bernard Pass, but it remained insecurely held until Augustus’s time when Aosta was founded on the southern edge of the pass. By 43 AD, when the emperor Claudius reigned, both the Great and Little Passes had Roman roads and mansios, rest places maintained by the central government for the use of those traveling on official business. Both also had a temple to Jupiter at their summit.

Wanting to find a shorter route between Italy and Gaul than the commonly used coastal route, Julius Caesar tried to secure the Great Saint Bernard Pass, but it remained insecurely held until Augustus’s time when Aosta was founded on the southern edge of the pass. By 43 AD, when the emperor Claudius reigned, both the Great and Little Passes had Roman roads and mansios, rest places maintained by the central government for the use of those traveling on official business. Both also had a temple to Jupiter at their summit.

At the Great St. Bernard Pass, a cross inscribed with Deo optimo maximo, to the best and greatest god was placed where the temple had been. The bronze statue of St Bernard stands where the mansio was. Coins dating back to the reign of Theodosius II, in the 1st half of the 5th century are now on display in the museum of the nearby hospice, while some of the buildings in the village of Bourg-Saint-Pierre 7 1/2 miles north, on the Swiss side of the pass, contain fragments of the marble temple.

After the fall of the Roman Empire, the mountain passes became haunts of brigands and outlaws who preyed on travelers. The first hospice, built to provide travelers a safe place to stop, was built in Bourg-Saint-Pierre during the 9th century and is first mentioned in a manuscript dated between 812 and 820 AD. Saracens destroyed this building when they invaded the area in the mid-10th century. It was refounded at the highest point on the Great St Bernard Pass in 1049, by Bernard of Menthon, the archdeacon of Aosta. Today, the hospice straddles both sides of the modern road and the old Roman road, which continues to see service as hiking path, goes around its northern edge, just uphill from the modern road..

After the fall of the Roman Empire, the mountain passes became haunts of brigands and outlaws who preyed on travelers. The first hospice, built to provide travelers a safe place to stop, was built in Bourg-Saint-Pierre during the 9th century and is first mentioned in a manuscript dated between 812 and 820 AD. Saracens destroyed this building when they invaded the area in the mid-10th century. It was refounded at the highest point on the Great St Bernard Pass in 1049, by Bernard of Menthon, the archdeacon of Aosta. Today, the hospice straddles both sides of the modern road and the old Roman road, which continues to see service as hiking path, goes around its northern edge, just uphill from the modern road..  Soumei Baba, CC BY 2.0 , via Wikimedia Commons This past summer, my husband, two friends, and I walked most of the way around Mont Blanc. Because we had some difficulty finding room in the hiking huts, we took a detour, traveling by bus through the Great Saint Bernard Pass. The Swiss bus took us up to the hospice, but would go no farther. We got off, then, unsure of when or even if a bus would be coming to the Italian side, we scurried past the hospice and its lake, and over the border into Italy. Fortunately, we learn that an Italian bus was coming soon and we would not be stranded at the top of the pass. Unfortunately, that mean we did not get to tour the hospice or the museum. However, the short time I spent there was inspiration enough to get a story started in my head. I am working on that story now. Jennifer Bohnhoff is the author of several contemporary and historical novels for middle grade and adult readers. You can learn more about her books on her website.

Soumei Baba, CC BY 2.0 , via Wikimedia Commons This past summer, my husband, two friends, and I walked most of the way around Mont Blanc. Because we had some difficulty finding room in the hiking huts, we took a detour, traveling by bus through the Great Saint Bernard Pass. The Swiss bus took us up to the hospice, but would go no farther. We got off, then, unsure of when or even if a bus would be coming to the Italian side, we scurried past the hospice and its lake, and over the border into Italy. Fortunately, we learn that an Italian bus was coming soon and we would not be stranded at the top of the pass. Unfortunately, that mean we did not get to tour the hospice or the museum. However, the short time I spent there was inspiration enough to get a story started in my head. I am working on that story now. Jennifer Bohnhoff is the author of several contemporary and historical novels for middle grade and adult readers. You can learn more about her books on her website.

The Great Saint Bernard Pass is the lowest pass lying on the ridge between the two highest mountains of the Alps, Mont Blanc and Monte Rosa. At 8,100 ft high, it connects Martigny in the Swiss canton of Valais, with Aosta, Italy. The Little Saint Bernard Pass, 7,178 ft high, straddles the French–Italian border and connects Savoie, France to the Aosta Valley. Both passes have been used since prehistoric times. At the summit, the road through Little St Bernard Pass bisects a stone circle that might have been a ceremonial site for the Tarentaisians, a Celtic tribe, during the period from c. 725 BC to 450 BC. The road has taken the place of a standing stone that stood in its center. While there are indications that the Great St Bernard Pass has been used since at least the bronze age, the first historical reference to it refers to its use by Boii and Lingones, Celtic tribes who crossed it during their invasion of Italy in 390 BC.

The stone ring at the top of Little Saint Bernard Pass. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The stone ring at the top of Little Saint Bernard Pass. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Publisher New York Ward, Lock, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Writers in the 1st century BC called the Great St Bernard Pass the Punic Pass. It may be that they misinterpreted the Celtic word pen, meaning head or summit, and wrongly believed that it was the pass that the Carthaginian general Hannibal used while crossing with his elephants into Italy in 218 BC.

Publisher New York Ward, Lock, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Writers in the 1st century BC called the Great St Bernard Pass the Punic Pass. It may be that they misinterpreted the Celtic word pen, meaning head or summit, and wrongly believed that it was the pass that the Carthaginian general Hannibal used while crossing with his elephants into Italy in 218 BC. While no one is sure of the exact route that Hannibal used, based on the limited descriptions written by classical authors, many a full century after the event, most historians now believe that Hannibal used the Little Saint Bernard Pass.

Wanting to find a shorter route between Italy and Gaul than the commonly used coastal route, Julius Caesar tried to secure the Great Saint Bernard Pass, but it remained insecurely held until Augustus’s time when Aosta was founded on the southern edge of the pass. By 43 AD, when the emperor Claudius reigned, both the Great and Little Passes had Roman roads and mansios, rest places maintained by the central government for the use of those traveling on official business. Both also had a temple to Jupiter at their summit.

Wanting to find a shorter route between Italy and Gaul than the commonly used coastal route, Julius Caesar tried to secure the Great Saint Bernard Pass, but it remained insecurely held until Augustus’s time when Aosta was founded on the southern edge of the pass. By 43 AD, when the emperor Claudius reigned, both the Great and Little Passes had Roman roads and mansios, rest places maintained by the central government for the use of those traveling on official business. Both also had a temple to Jupiter at their summit. At the Great St. Bernard Pass, a cross inscribed with Deo optimo maximo, to the best and greatest god was placed where the temple had been. The bronze statue of St Bernard stands where the mansio was. Coins dating back to the reign of Theodosius II, in the 1st half of the 5th century are now on display in the museum of the nearby hospice, while some of the buildings in the village of Bourg-Saint-Pierre 7 1/2 miles north, on the Swiss side of the pass, contain fragments of the marble temple.

After the fall of the Roman Empire, the mountain passes became haunts of brigands and outlaws who preyed on travelers. The first hospice, built to provide travelers a safe place to stop, was built in Bourg-Saint-Pierre during the 9th century and is first mentioned in a manuscript dated between 812 and 820 AD. Saracens destroyed this building when they invaded the area in the mid-10th century. It was refounded at the highest point on the Great St Bernard Pass in 1049, by Bernard of Menthon, the archdeacon of Aosta. Today, the hospice straddles both sides of the modern road and the old Roman road, which continues to see service as hiking path, goes around its northern edge, just uphill from the modern road..

After the fall of the Roman Empire, the mountain passes became haunts of brigands and outlaws who preyed on travelers. The first hospice, built to provide travelers a safe place to stop, was built in Bourg-Saint-Pierre during the 9th century and is first mentioned in a manuscript dated between 812 and 820 AD. Saracens destroyed this building when they invaded the area in the mid-10th century. It was refounded at the highest point on the Great St Bernard Pass in 1049, by Bernard of Menthon, the archdeacon of Aosta. Today, the hospice straddles both sides of the modern road and the old Roman road, which continues to see service as hiking path, goes around its northern edge, just uphill from the modern road..  Soumei Baba, CC BY 2.0 , via Wikimedia Commons This past summer, my husband, two friends, and I walked most of the way around Mont Blanc. Because we had some difficulty finding room in the hiking huts, we took a detour, traveling by bus through the Great Saint Bernard Pass. The Swiss bus took us up to the hospice, but would go no farther. We got off, then, unsure of when or even if a bus would be coming to the Italian side, we scurried past the hospice and its lake, and over the border into Italy. Fortunately, we learn that an Italian bus was coming soon and we would not be stranded at the top of the pass. Unfortunately, that mean we did not get to tour the hospice or the museum. However, the short time I spent there was inspiration enough to get a story started in my head. I am working on that story now. Jennifer Bohnhoff is the author of several contemporary and historical novels for middle grade and adult readers. You can learn more about her books on her website.

Soumei Baba, CC BY 2.0 , via Wikimedia Commons This past summer, my husband, two friends, and I walked most of the way around Mont Blanc. Because we had some difficulty finding room in the hiking huts, we took a detour, traveling by bus through the Great Saint Bernard Pass. The Swiss bus took us up to the hospice, but would go no farther. We got off, then, unsure of when or even if a bus would be coming to the Italian side, we scurried past the hospice and its lake, and over the border into Italy. Fortunately, we learn that an Italian bus was coming soon and we would not be stranded at the top of the pass. Unfortunately, that mean we did not get to tour the hospice or the museum. However, the short time I spent there was inspiration enough to get a story started in my head. I am working on that story now. Jennifer Bohnhoff is the author of several contemporary and historical novels for middle grade and adult readers. You can learn more about her books on her website.

Published on November 15, 2022 08:29

November 2, 2022

Bedbugs!

This summer my husband and I joined another couple on a grand adventure: the four of us walked around Mont Blanc, the largest mountain in the Alps. Mont Blanc straddles the borders of France, Switzerland and Italy, so I had a lot to think about as I walked. It was an interesting and exciting, and it inspired me to begin thinking of how I could turn what I saw and experienced, both the good and the bad, into a book.

This summer my husband and I joined another couple on a grand adventure: the four of us walked around Mont Blanc, the largest mountain in the Alps. Mont Blanc straddles the borders of France, Switzerland and Italy, so I had a lot to think about as I walked. It was an interesting and exciting, and it inspired me to begin thinking of how I could turn what I saw and experienced, both the good and the bad, into a book.I won’t sugarcoat it: I did experience both good and bad. The scenery was beautiful, the food fantastic, the people friendly and kind. But there was also some parts of the trip that I wouldn’t want to repeat. The bedbugs fall into the later category.

We stayed in a wide variety of lodgings during our trip. One night, we stayed in a hostel that looked like it had been used as a barn before being converted into a place for hikers. The inside was furnished with rows of bunkbeds. The bathroom area, which had many narrow rooms with outfitted with toilets and others with showerheads, also had a long, trough-like sink. Our own beds were up in what had been the hayloft. It looked nice enough. But then we turned out the lights and went to sleep.

No sooner than it grew dark than I felt something strange. The feeling, a tingling, began on my hands. I began to itch. Soon the feeling way everywhere: my back, my legs, my face, my neck.

No sooner than it grew dark than I felt something strange. The feeling, a tingling, began on my hands. I began to itch. Soon the feeling way everywhere: my back, my legs, my face, my neck.But no one else in my party seemed affected. They slept soundly while I thrashed and scratched. I believed that I was the only one affected. Sometime during the night, I got out of my bed and moved to another one, believing that I could leave my tormenters behind.

When morning came, I discovered that I was not the only victim of the bedbugs. My skin reacted the most strongly: I had itchy welts for several weeks afterwards. That shouldn’t have been a surprise, since I react very strongly to mosquito bites too, but everyone had been bitten. I felt awful that I hadn't roused everyone in the middle of the night.

We walked down to the nearest town and found a laundromat, where we boiled, drowned our clothes (and, we hoped, the bugs) in the washer, and baked them in the dryer. We turned our sleeping bags, our jackets and our backpacks inside out searching for the devious little bugs. We must have been successful in eliminating them, for they tormented us no more. But the welts, and the emotional trauma of the attack, stayed with us.

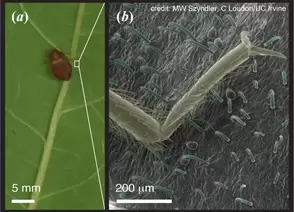

Bedbugs have been around since the time of the dinosaurs, so it’s likely that they have been bothering people for as long as there have been people to bug. There are mentions of them in ancient Greek manuscripts dating from 400 BC. Aristotle wrote about bedbugs, and they are mentioned in Pliny's Natural History, first published in Rome around AD 77. They are aggravating, but fortunately are not a vector for any serious diseases.

Bedbugs have been around since the time of the dinosaurs, so it’s likely that they have been bothering people for as long as there have been people to bug. There are mentions of them in ancient Greek manuscripts dating from 400 BC. Aristotle wrote about bedbugs, and they are mentioned in Pliny's Natural History, first published in Rome around AD 77. They are aggravating, but fortunately are not a vector for any serious diseases.

People have been trying to find ways to eliminate bedbugs, or at least alleviate the itching, for as long as they’ve been plagued by the little critters. One old folk remedy that housewives in Eastern Europe have been using for generations used the leaves from bean plants. These leaves were spread on the floor. In the morning, they were covered with bedbugs and were taken out and burned. It wasn’t until recently that scientists were able to determine that bean leaves have microscopic hooks that impale the insects, capturing them. You can bet I’m using bean leaf bed bug traps in my book about the Alps! I went into a French pharmacy looking for relief from the itching. I discovered that the French are not fans of cortisone creams. Instead, I got a tube filled with herbal oil that was dispensed through a top that had a metal roll-on ball. The oil smelled like eucalyptus or Vics Formula 44. It did little to stop the itching, but it gave me something to do.

People have been trying to find ways to eliminate bedbugs, or at least alleviate the itching, for as long as they’ve been plagued by the little critters. One old folk remedy that housewives in Eastern Europe have been using for generations used the leaves from bean plants. These leaves were spread on the floor. In the morning, they were covered with bedbugs and were taken out and burned. It wasn’t until recently that scientists were able to determine that bean leaves have microscopic hooks that impale the insects, capturing them. You can bet I’m using bean leaf bed bug traps in my book about the Alps! I went into a French pharmacy looking for relief from the itching. I discovered that the French are not fans of cortisone creams. Instead, I got a tube filled with herbal oil that was dispensed through a top that had a metal roll-on ball. The oil smelled like eucalyptus or Vics Formula 44. It did little to stop the itching, but it gave me something to do.  People in the Alps have been using various herbal remedies for their ailments for a long time. A website dedicated to Alpine plants with medicinal uses stated that a bruised leaf from a plantain weed presents the itching caused by insect bites and nettles. I wish I had known this while I was still up on the trail. It certainly would have worked as well as the little roll-on bottle did.

People in the Alps have been using various herbal remedies for their ailments for a long time. A website dedicated to Alpine plants with medicinal uses stated that a bruised leaf from a plantain weed presents the itching caused by insect bites and nettles. I wish I had known this while I was still up on the trail. It certainly would have worked as well as the little roll-on bottle did.Am I glad I experienced bedbugs during my trip to the Alps? Absolutely not! But I can use the experience to make my writing more interesting and more informed. Writers have a great reason to appreciate even the worst of experiences.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is the author of several works of historical fiction written for middle grade through adult readers. She is participating in National Novel Writing Month by working on a first draft of a novel set in the Alps in 1799-1800. The first chapter begins with bedbugs!

Jennifer Bohnhoff is the author of several works of historical fiction written for middle grade through adult readers. She is participating in National Novel Writing Month by working on a first draft of a novel set in the Alps in 1799-1800. The first chapter begins with bedbugs!

Published on November 02, 2022 23:00

October 27, 2022

The VPK: The Soldier's Camera

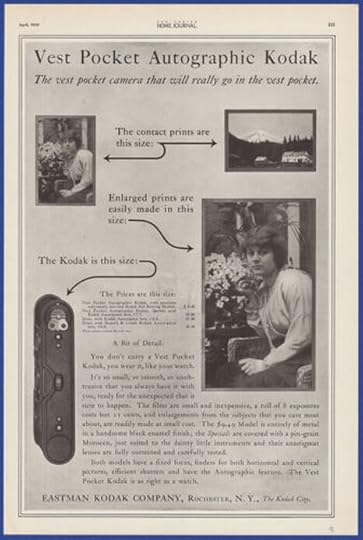

The beginning of the twentieth century was a time of massive change in society and in technology. One of the new inventions during this period was a camera so compact, it could slip into a man’s pocket.

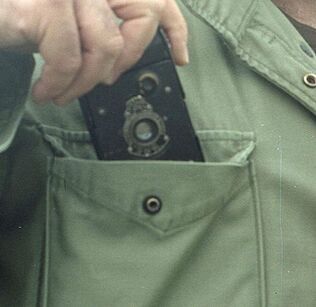

The beginning of the twentieth century was a time of massive change in society and in technology. One of the new inventions during this period was a camera so compact, it could slip into a man’s pocket.One of the first and most successful compact cameras was the Vest Pocket Kodak camera, or

‘VPK.’ Priced between $6 and $15 depending on the features, about 5,500 VPKs were sold in Britain in 1912, the first year it was produced. The next year over 28,000 of these cameras were sold in Britain. By the time the model was discontinued in 1926, over 2 million had been sold, making it one of the most popular and successful cameras of its day.

‘VPK.’ Priced between $6 and $15 depending on the features, about 5,500 VPKs were sold in Britain in 1912, the first year it was produced. The next year over 28,000 of these cameras were sold in Britain. By the time the model was discontinued in 1926, over 2 million had been sold, making it one of the most popular and successful cameras of its day.

The Vest Pocket Kodak measured just 1’ by 2½’ by 4¾’. The lens panel expanded away from the film roll by way of a pair of lazy-tongs struts that were either outside or inside a leather bellows, depending on the model. Prior to this period, cameras were made from wood to make them lightweight. The VPK was made from metal.

The Vest Pocket Kodak measured just 1’ by 2½’ by 4¾’. The lens panel expanded away from the film roll by way of a pair of lazy-tongs struts that were either outside or inside a leather bellows, depending on the model. Prior to this period, cameras were made from wood to make them lightweight. The VPK was made from metal.

In 1915, Kodak introduced the ‘Autographic’ Vest Pocket Kodak. Based on a patent taken out in 1913 by American inventor Henry Gaisman, this camera used a roll of film that had a thin tissue of carbon paper inserted between the film and the backing paper. Photographers could open a small flap in the back of the camera to uncover the backing paper. The photographer then used a metal stylus to write information on their negatives which would appear on their finished prints.

In 1915, Kodak introduced the ‘Autographic’ Vest Pocket Kodak. Based on a patent taken out in 1913 by American inventor Henry Gaisman, this camera used a roll of film that had a thin tissue of carbon paper inserted between the film and the backing paper. Photographers could open a small flap in the back of the camera to uncover the backing paper. The photographer then used a metal stylus to write information on their negatives which would appear on their finished prints.The VPK took film negatives that were 1⅝” by 2½” -- larger than a postage stamp. Pictures could be enlarged for easier viewing.

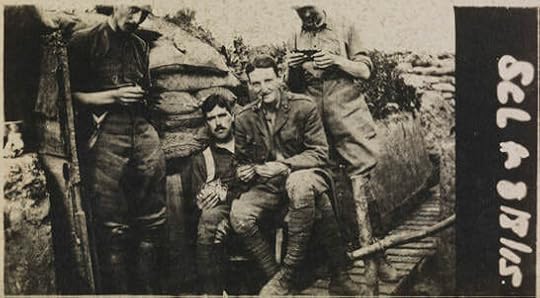

So many soldiers bought cameras to record their travels and experiences that the VPK became known as ‘The Soldier’s Kodak.’ Thousands of American ‘doughboys’ recorded their wartime experiences using this handy little camera.

So many soldiers bought cameras to record their travels and experiences that the VPK became known as ‘The Soldier’s Kodak.’ Thousands of American ‘doughboys’ recorded their wartime experiences using this handy little camera.  Heinrich Dieter, one of the characters in Jennifer Bohnhoff's award winning historical novel A Blaze of Poppies, owns and uses a vest pocket Kodak both at home in Southern New Mexico and while serving as a medic on the battlefields of France.

Heinrich Dieter, one of the characters in Jennifer Bohnhoff's award winning historical novel A Blaze of Poppies, owns and uses a vest pocket Kodak both at home in Southern New Mexico and while serving as a medic on the battlefields of France.

Published on October 27, 2022 15:13

October 26, 2022

Halloween-Worthy Horror in the Alps

November is National Novel Writing Month, and I’m participating again this year. I’ll be working on a middle grade historical novel inspired by, but not in any way based on my summer hike, the Tour du Mont Blanc. As I researched the scenes of my story, I discovered that Charles Dickens toured Switzerland in the summer of 1846. One of the places that both Dickens and I went to was the hospice at the top of the Great Saint Bernard Pass. This Hospice is the highest winter habitation in the Alps. It is also the place where the eponymous dog breed got its start. Run by Augustinian monks, it has been sheltering and protecting travelers since its founding, nearly a thousand years ago, by Bernard of Menthon. Etchings from Dicken’s time demonstrate that little has changed in the past two hundred years.

November is National Novel Writing Month, and I’m participating again this year. I’ll be working on a middle grade historical novel inspired by, but not in any way based on my summer hike, the Tour du Mont Blanc. As I researched the scenes of my story, I discovered that Charles Dickens toured Switzerland in the summer of 1846. One of the places that both Dickens and I went to was the hospice at the top of the Great Saint Bernard Pass. This Hospice is the highest winter habitation in the Alps. It is also the place where the eponymous dog breed got its start. Run by Augustinian monks, it has been sheltering and protecting travelers since its founding, nearly a thousand years ago, by Bernard of Menthon. Etchings from Dicken’s time demonstrate that little has changed in the past two hundred years. One thing that has changed is access to one of the hospice’s more morbid rooms: the mortuary. In Dickens’ time, the mortuary that still stands beside the Hospice was a great curiosity to travelers. Murray’s Handbook for Travellers in Switzerland, published in 1843 included it among the must-see sites. It is known that Dickens took a copy of this travel guide with him. He describes the room in a letter he wrote to John Forster on September 6, 1846:

Beside the convent, in a little outhouse with a grated iron door which you may unbolt for yourself, are the bodies of people found in the snow who have never been claimed and are withering away – not laid down, or stretched out, but standing up, in corners and against walls; some erect and horribly human, with distinct expression on the faces; some sunk down on their knees; some dropping over one on side; some tumbled down altogether, and presenting a heap of skulls and fibrous dust.The door to the mortuary is closed now. I do not know whether I could have pleaded to gain access, and I suspect that the bodies that had remained there are now long gone.

One set of bodies in particular fascinated both Dickens, who included her in his novel Little Dorrit, and Murray, who includes a description in his travel guide. She is a mother who Dickens describes as “storm-belated many winters ago, still standing in the corner with er baby at her breast.” Dickens pities the mother and gives her voice: “Surrounded by so many and such companions upon whom I never looked, and shall never look, I and my child will dwell together inseparable, on the Great Saint Bernard, outlasting generations who will come to see us, and will never know our name, or one word of our story but the end.” Dickens did not care to create a backstory for the poor, frozen woman and her child. Neither shall I. But his words continue to keep her alive in the hearts of readers some two hundred years after her death.

Jennifer Bohnhoff writes novels for middle grade and adult readers. Many of them are historical in nature.

Published on October 26, 2022 23:00

October 19, 2022

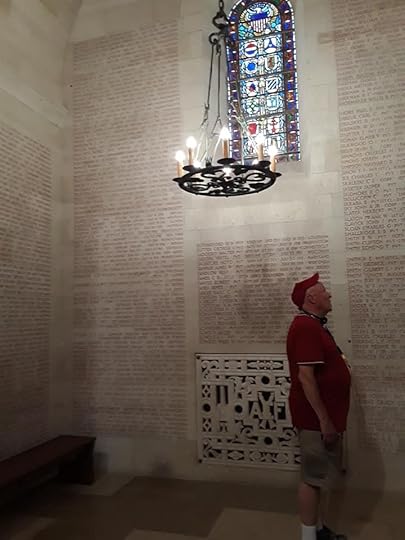

The Aisne-Marne American Cemetery: A Monument of Remembrance

Americans call November 11th Veteran's Day, and use the day to honor veterans of all wars . But originally November 11th observed Armistice Day, the when World War I ended, at least officially. .

Americans call November 11th Veteran's Day, and use the day to honor veterans of all wars . But originally November 11th observed Armistice Day, the when World War I ended, at least officially. .There are many cemeteries in Belgium and France that hold the remains of Americans killed during the First World War. Unlike the cemeteries in Normandy, which contain those killed during the D-Day Invasion in World War Two, many of the World War 1 cemeteries recieve very few visitors each year.

The Aisne-Marne American Cemetery covers 42.5-acres at the foot of the hills that holds Belleau Wood. It contains the graves of 2,289 war dead. Most of these men came from the U.S. 2nd Division, which included the 4th Marine Brigade, and fought in the 20 day long battle for Belleau Wood. Also buried here are soldiers from the 3rd Division who arrived in Château-Thierry and blocked German forces on the north bank of the Marne throughout June.and July of 1918.

The Aisne-Marne American Cemetery covers 42.5-acres at the foot of the hills that holds Belleau Wood. It contains the graves of 2,289 war dead. Most of these men came from the U.S. 2nd Division, which included the 4th Marine Brigade, and fought in the 20 day long battle for Belleau Wood. Also buried here are soldiers from the 3rd Division who arrived in Château-Thierry and blocked German forces on the north bank of the Marne throughout June.and July of 1918.The second largest number of New Mexicans killed in France during World War I died at the Battle of Chateau-Thierry. Many of them were part of Battery A of the New Mexico National Guard, which came from Roswell. The 28 New Mexicans killed in this battle are interred at the Aisne-Marne American Cemetery together with 2,261 AEF soldiers.

The carved marble at the top of the pillars that flank the entrance to the French Romanesque chapel depict soldiers engaged in battle in the trenches.

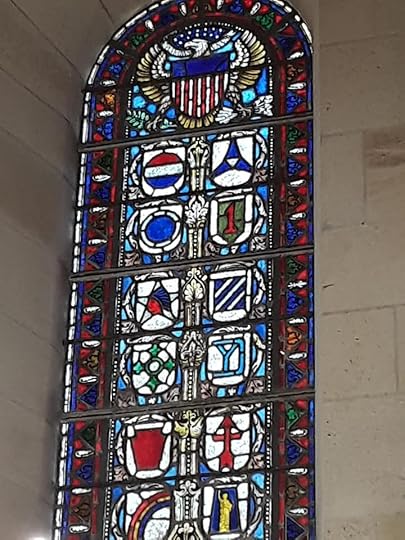

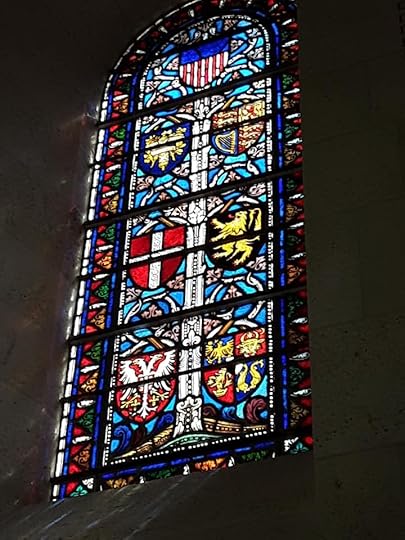

The carved marble at the top of the pillars that flank the entrance to the French Romanesque chapel depict soldiers engaged in battle in the trenches.  One of the stained glass windows inside displays the insignias of American divisions engaged in the area. Another window has the crests of countries on the Allied side of the war.

One of the stained glass windows inside displays the insignias of American divisions engaged in the area. Another window has the crests of countries on the Allied side of the war.

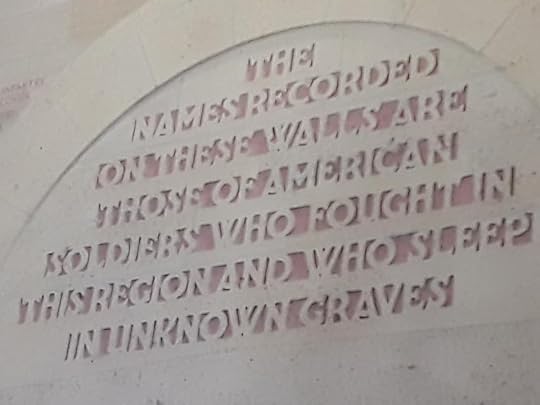

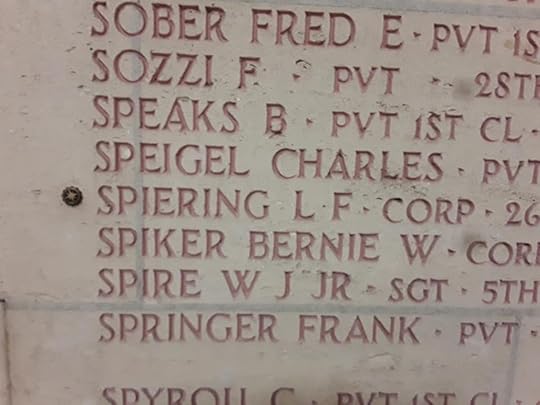

The inside of the chapel is inscribed with the names of 1060 men who were missing after the battles. Some of those names have a small brass star next to them. That means the body was later found and identified.

The inside of the chapel is inscribed with the names of 1060 men who were missing after the battles. Some of those names have a small brass star next to them. That means the body was later found and identified.

It has been over a hundred years since World War I ended. There are no veterans left for us to honor. But we must never forget, and we must continue to honor the men who went "over there" and fought to keep us free.

It has been over a hundred years since World War I ended. There are no veterans left for us to honor. But we must never forget, and we must continue to honor the men who went "over there" and fought to keep us free.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a native New Mexico with an interest in history. In 2019, she had the privilege of touring the Aisne-Marne American Cemetery and walking through Belleau Wood. That experience led her to writing A Blaze of Poppies, a novel about New Mexico's involvement in World War I.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a native New Mexico with an interest in history. In 2019, she had the privilege of touring the Aisne-Marne American Cemetery and walking through Belleau Wood. That experience led her to writing A Blaze of Poppies, a novel about New Mexico's involvement in World War I.

Published on October 19, 2022 23:00

October 12, 2022

Following in the Footsteps of Another, Greater Author

November is National Novel Writing Month, and I’m participating again this year. I’ll be working on a middle grade historical novel inspired by, but not in any way based on my recent hike around the Mont Blanc massif. I don’t have a title for this work as of yet; perhaps you, dear readers can help me determine a good title sometime during November.

November is National Novel Writing Month, and I’m participating again this year. I’ll be working on a middle grade historical novel inspired by, but not in any way based on my recent hike around the Mont Blanc massif. I don’t have a title for this work as of yet; perhaps you, dear readers can help me determine a good title sometime during November.

What I do know thus far is that my novel will be set in 1799-1800 and will take place in Great Saint Bernard Pass, a route through the Alps that travels up the Rhone Valley from Martigny, Switzerland to Aosta, Italy. Great Saint Bernard pass is not the prettiest of passes, but it is convenient and offers the additional attraction of the Saint Bernard Hospice, the highest winter habitation in the Alps, at the top of the pass. The Hospice is also the place where the eponymous dog breed got its start.

When I went through the Great Saint Bernard Pass this past September, I traveled by bus: not a city bus or a school bus, but the kind of tour bus that holds perhaps fifty passengers, with two big upholstered seats on each side of a central aisle. The road itself, which is now called highway E27, was paved, but it had only two lanes, one in each direction, and it had more hairpin turns than a roller coaster. More than once, I was convinced that the bus wasn’t going to be able to negotiate a turn. A few times I was right, and the bus driver had to throw the bus into reverse and make an extra cut in order to make it around a tight bend.

When I went through the Great Saint Bernard Pass this past September, I traveled by bus: not a city bus or a school bus, but the kind of tour bus that holds perhaps fifty passengers, with two big upholstered seats on each side of a central aisle. The road itself, which is now called highway E27, was paved, but it had only two lanes, one in each direction, and it had more hairpin turns than a roller coaster. More than once, I was convinced that the bus wasn’t going to be able to negotiate a turn. A few times I was right, and the bus driver had to throw the bus into reverse and make an extra cut in order to make it around a tight bend.

I’ve been doing a lot of research this past month, and I’ve discovered that Charles Dickens went through the Great Saint Bernard Pass (and yes, there is a Lesser Saint Bernard Pass.) in September of 1846 when he was touring Switzerland. Dickens did not ride in a tour bus. In his day, the path was so rocky that the only way to travel along what was then called the Chemin des Chanoines, or the pathway taken by the canons of the hospice, was on foot or astride a donkey or horse. Even carriages could not make the journey; they were disassembled at Bourg-Saint-Pierre, the highest village on the Swiss side, then carried over the pass by porters and reassembled on the Italian side.

Dickens includes his perception of traveling Great Saint Bernard Pass in his novel Little Dorrit. In Book 2, chapter 1, his travelers ride through “the searching old of the frosty rarefied night air at a great height,” through a landscape marked by “barrenness and desolation. A craggy track, up which the mules, in single file, scrambled and turned from block to block, as through they were ascending the broken staircase of a gigantic ruin.” In these upper reaches of the pass, “no trees were to be seen, nor any vegetable growth, save a poor brown scrubby moss, freezing in the chinks of rock.” At the front of the mules is “a guide on foot, in his broad-brimmed had and round jacket, carrying a mountain staff or two upon his shoulder.”

Dickens includes his perception of traveling Great Saint Bernard Pass in his novel Little Dorrit. In Book 2, chapter 1, his travelers ride through “the searching old of the frosty rarefied night air at a great height,” through a landscape marked by “barrenness and desolation. A craggy track, up which the mules, in single file, scrambled and turned from block to block, as through they were ascending the broken staircase of a gigantic ruin.” In these upper reaches of the pass, “no trees were to be seen, nor any vegetable growth, save a poor brown scrubby moss, freezing in the chinks of rock.” At the front of the mules is “a guide on foot, in his broad-brimmed had and round jacket, carrying a mountain staff or two upon his shoulder.”  I’ve seen a painting of another rider on a mule, guided by another man who knew the trail, but that is a story best saved for another blog.

I’ve seen a painting of another rider on a mule, guided by another man who knew the trail, but that is a story best saved for another blog. Jennifer Bohnhoff writes for middle grade and adult readers. Most of her books are works of historical fiction. You can read more about her and her book on her website.

Published on October 12, 2022 23:00