Crossing the Alps: Reality vs. Propaganda

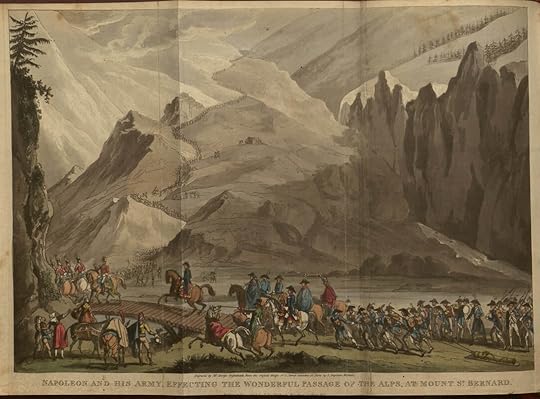

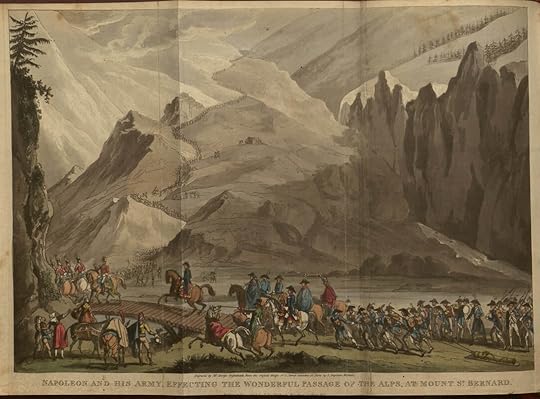

When Napoleon Bonaparte crossed the Alps to push the Austrians out of Italy in the spring of 1800, he was determined that the world know that this crossing put him on a footing with the world’s most renowned generals. Hannibal Barca, the great Carthaginian general, had crossed in 218 BC to attack the Romans. Charlemagne, the great Frankish king who became the first Holy Roman Emperor, did so in 772 AD. Now that Napoleon was to add this accomplishment to his list, he commissioned his favorite painted, Jacques-Louis David, to commemorate the event. David did so in his five versions of Napoleon Crossing the Alps, paintings that remains instantly recognizable the world over. But what Napoleon wanted and what David provided, was not in any way historically accurate. Instead, it is propaganda, more representative of Napoleon’s character and goals. David didn't paint what Napoleon looked like as he cross the Alps. He painted what Napoleon wanted everyone to think he looked like: a man who could control France and the world as easily as he could control -- with just one hand. -- a rearing horse.

In the original version, which is hung at Malmaison, a very young-looking Bonaparte wears an orange cloak and rides a black and white piebald horse. The Charlottenburg shows Napoleon with a slight smile, wearing a red cloak and mounted on a chestnut horse. There are two versions hung at Versailles, the first shows a stern-looking Napoleon riding a dappled grey horse, while the second shows an older Napoleon, with shorter hair wearing an orangy-red cloak and mounted on a black and white horse. A final version, from the Belvedere, is almost identical to the first Versailles version. In all versions, the horse is rearing and Napoleon is pointing, guiding his men over difficult pass. Behind the horse and rider, there is a small view of soldiers struggling to get their cannons over the pass. The sky is stormy and dark. What Napoleon wanted and what David provided, was not in any way historically accurate. Instead, it is propaganda, more representative of Napoleon’s character and goals. Not even the face in David’s portraits was drawn from life because the fidgety and impatient Bonaparte had refused to sit still for the painter.

In one account, David asks Napoleon to pose and he answers “Sit? For what good? Do you think that the great men of Antiquity for whom we have images sat?”

“But Citizen First Consul,” David responded, “I am painting you for your century, for the men who have seen you, who know you, they will want to find a resemblance.”

“A resemblance? It isn't the exactness of the features, a wart on the nose which gives the resemblance. It is the character that dictates what must be painted...Nobody knows if the portraits of the great men resemble them, it is enough that their genius lives there.”

After failing to persuade Napoleon to sit still, David copied the features of a bust of the First Consul. To get the posture correctly, David had his son perch on top a ladder.

Look in the lower right hand corner, where men are pulling a cannon barrel. But it is not just Napoleon’s face that is inaccurate. The trail over the Grand Saint Bernard Pass is so narrow, steep, and rocky that wheeled conveyances, including cannons, could not negotiate it. The army took apart the cannon and their carriage in Bourg-Saint-Pierre, the highest village up the northern side of the pass. Tree trunks were hollowed out, the cannon barrels placed inside them, then slings were made so that 100 men could carry each cannon barrel. Other men carried the disassembled carriages, and other men carried the wheels.

Look in the lower right hand corner, where men are pulling a cannon barrel. But it is not just Napoleon’s face that is inaccurate. The trail over the Grand Saint Bernard Pass is so narrow, steep, and rocky that wheeled conveyances, including cannons, could not negotiate it. The army took apart the cannon and their carriage in Bourg-Saint-Pierre, the highest village up the northern side of the pass. Tree trunks were hollowed out, the cannon barrels placed inside them, then slings were made so that 100 men could carry each cannon barrel. Other men carried the disassembled carriages, and other men carried the wheels.

Records indicate that Napoleon did not lead his men over the pass. Instead, General Maréscot led the army while Bonaparte followed after them by several days. By the time he crossed, the sky was sunny and the weather calm, although it remained cold and the ground covered with snow.

Finally, Napoleon Bonaparte was not riding any of the horses depicted in the various versions of David’s paintings. Because of the treacherous conditions, he was riding a much mor surefooted mule, and the mule was being led by an alpine guide named Pierre-Nicolas Dorsaz.

Dorsaz later related that the mule slipped during the ascent into the mountains. Napoleon would have fallen over a precipice had Dorsaz not been walking between the mule and the edge of the track. Although Napoleon showed no emotion at the time, he began questioning his guide about his life in the village of Bourg-Saint-Pierre. Dorsaz told Napoleon that his dream was to have a small farm, a field and cow. When the First Consul asked about the normal fee for alpine guides, Dorsaz told him that guides were usually paid three francs. Napoleon then ordered that Dorsaz be paid 60 Louis, or 1200 francs for his "zeal and devotion to his task" during the crossing of the Alps. Local legend says that Dorsaz used the money to buy his farm and marry Eléonore Genoud, the girl he loved.

In 1848 Arthur George, the 3rd Earl of Onslow, was visiting the Louvre with Paul Delaroche, the painter who had painted Charlemagne Crossing the Alps. George commissioned Delaroche to produce a more accurate version of Napoleon crossing the Alps, which was completed in 1850. While much more historically accurate, this depiction is nowhere as heroic or romantic. Jennifer Bohnhoff is currently working on a novel set in the Great Saint Bernard Pass in the years 1799 and 1800. Napoleon has a tiny cameo appearance in her story, but Dorsaz the mountain guide shows up in three different scenes. For more information about her and her other books, see her website.

In 1848 Arthur George, the 3rd Earl of Onslow, was visiting the Louvre with Paul Delaroche, the painter who had painted Charlemagne Crossing the Alps. George commissioned Delaroche to produce a more accurate version of Napoleon crossing the Alps, which was completed in 1850. While much more historically accurate, this depiction is nowhere as heroic or romantic. Jennifer Bohnhoff is currently working on a novel set in the Great Saint Bernard Pass in the years 1799 and 1800. Napoleon has a tiny cameo appearance in her story, but Dorsaz the mountain guide shows up in three different scenes. For more information about her and her other books, see her website.

In the original version, which is hung at Malmaison, a very young-looking Bonaparte wears an orange cloak and rides a black and white piebald horse. The Charlottenburg shows Napoleon with a slight smile, wearing a red cloak and mounted on a chestnut horse. There are two versions hung at Versailles, the first shows a stern-looking Napoleon riding a dappled grey horse, while the second shows an older Napoleon, with shorter hair wearing an orangy-red cloak and mounted on a black and white horse. A final version, from the Belvedere, is almost identical to the first Versailles version. In all versions, the horse is rearing and Napoleon is pointing, guiding his men over difficult pass. Behind the horse and rider, there is a small view of soldiers struggling to get their cannons over the pass. The sky is stormy and dark. What Napoleon wanted and what David provided, was not in any way historically accurate. Instead, it is propaganda, more representative of Napoleon’s character and goals. Not even the face in David’s portraits was drawn from life because the fidgety and impatient Bonaparte had refused to sit still for the painter.

In one account, David asks Napoleon to pose and he answers “Sit? For what good? Do you think that the great men of Antiquity for whom we have images sat?”

“But Citizen First Consul,” David responded, “I am painting you for your century, for the men who have seen you, who know you, they will want to find a resemblance.”

“A resemblance? It isn't the exactness of the features, a wart on the nose which gives the resemblance. It is the character that dictates what must be painted...Nobody knows if the portraits of the great men resemble them, it is enough that their genius lives there.”

After failing to persuade Napoleon to sit still, David copied the features of a bust of the First Consul. To get the posture correctly, David had his son perch on top a ladder.

Look in the lower right hand corner, where men are pulling a cannon barrel. But it is not just Napoleon’s face that is inaccurate. The trail over the Grand Saint Bernard Pass is so narrow, steep, and rocky that wheeled conveyances, including cannons, could not negotiate it. The army took apart the cannon and their carriage in Bourg-Saint-Pierre, the highest village up the northern side of the pass. Tree trunks were hollowed out, the cannon barrels placed inside them, then slings were made so that 100 men could carry each cannon barrel. Other men carried the disassembled carriages, and other men carried the wheels.

Look in the lower right hand corner, where men are pulling a cannon barrel. But it is not just Napoleon’s face that is inaccurate. The trail over the Grand Saint Bernard Pass is so narrow, steep, and rocky that wheeled conveyances, including cannons, could not negotiate it. The army took apart the cannon and their carriage in Bourg-Saint-Pierre, the highest village up the northern side of the pass. Tree trunks were hollowed out, the cannon barrels placed inside them, then slings were made so that 100 men could carry each cannon barrel. Other men carried the disassembled carriages, and other men carried the wheels. Records indicate that Napoleon did not lead his men over the pass. Instead, General Maréscot led the army while Bonaparte followed after them by several days. By the time he crossed, the sky was sunny and the weather calm, although it remained cold and the ground covered with snow.

Finally, Napoleon Bonaparte was not riding any of the horses depicted in the various versions of David’s paintings. Because of the treacherous conditions, he was riding a much mor surefooted mule, and the mule was being led by an alpine guide named Pierre-Nicolas Dorsaz.

Dorsaz later related that the mule slipped during the ascent into the mountains. Napoleon would have fallen over a precipice had Dorsaz not been walking between the mule and the edge of the track. Although Napoleon showed no emotion at the time, he began questioning his guide about his life in the village of Bourg-Saint-Pierre. Dorsaz told Napoleon that his dream was to have a small farm, a field and cow. When the First Consul asked about the normal fee for alpine guides, Dorsaz told him that guides were usually paid three francs. Napoleon then ordered that Dorsaz be paid 60 Louis, or 1200 francs for his "zeal and devotion to his task" during the crossing of the Alps. Local legend says that Dorsaz used the money to buy his farm and marry Eléonore Genoud, the girl he loved.

In 1848 Arthur George, the 3rd Earl of Onslow, was visiting the Louvre with Paul Delaroche, the painter who had painted Charlemagne Crossing the Alps. George commissioned Delaroche to produce a more accurate version of Napoleon crossing the Alps, which was completed in 1850. While much more historically accurate, this depiction is nowhere as heroic or romantic. Jennifer Bohnhoff is currently working on a novel set in the Great Saint Bernard Pass in the years 1799 and 1800. Napoleon has a tiny cameo appearance in her story, but Dorsaz the mountain guide shows up in three different scenes. For more information about her and her other books, see her website.

In 1848 Arthur George, the 3rd Earl of Onslow, was visiting the Louvre with Paul Delaroche, the painter who had painted Charlemagne Crossing the Alps. George commissioned Delaroche to produce a more accurate version of Napoleon crossing the Alps, which was completed in 1850. While much more historically accurate, this depiction is nowhere as heroic or romantic. Jennifer Bohnhoff is currently working on a novel set in the Great Saint Bernard Pass in the years 1799 and 1800. Napoleon has a tiny cameo appearance in her story, but Dorsaz the mountain guide shows up in three different scenes. For more information about her and her other books, see her website.

Published on November 29, 2022 23:00

No comments have been added yet.