Jennifer Bohnhoff's Blog, page 17

June 22, 2022

The Death of the Exchange Hotel

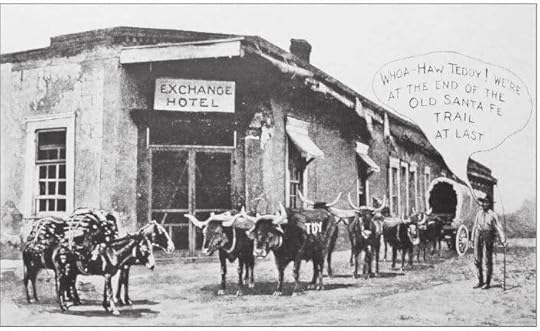

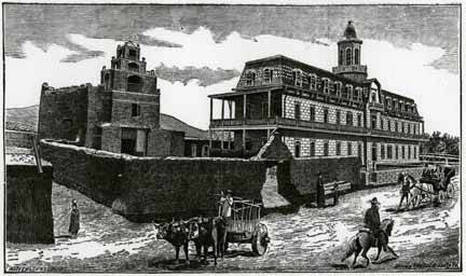

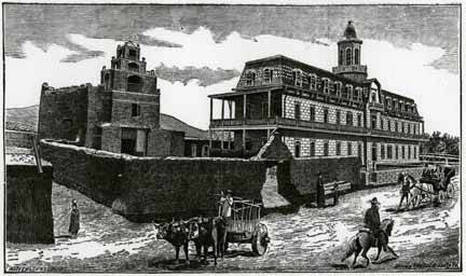

The first etching of the hotel at the corner of San Francisco and Shelby, by Theodore B. Davis of Harper's Weekly, in 1846. In the background is La Parochia, the church that was built in 1717 and replaced in 1869 by St. Francis Cathedral. The Exchange Hotel sat on what might be the oldest hotel corner in the United States. The corner of San Francisco and Shelby Street in Santa Fe, New Mexico has held a hotel since, perhaps, before the Pilgrims arrived at Plymouth Rock.

The first etching of the hotel at the corner of San Francisco and Shelby, by Theodore B. Davis of Harper's Weekly, in 1846. In the background is La Parochia, the church that was built in 1717 and replaced in 1869 by St. Francis Cathedral. The Exchange Hotel sat on what might be the oldest hotel corner in the United States. The corner of San Francisco and Shelby Street in Santa Fe, New Mexico has held a hotel since, perhaps, before the Pilgrims arrived at Plymouth Rock.Although there is no documentation before 1822, when the Santa Fe Trail opened, tradition says that an inn, or tavern stood on that corner for hundreds of years before that time. Some suggest that the first inn was built there in 1609, when the city was first founded..

By 1822, the inn (or fonda in Spanish) that stood there was a well-known rendezvous for trappers, traders, pioneers, merchants, soldiers and politicians. Its gaming tables held faro and monte games, and its luncheons were considered the best in town. Located at the end of the Santa Fe Trail and the Camino Real, it was the scene of many celebrations.

By 1822, the inn (or fonda in Spanish) that stood there was a well-known rendezvous for trappers, traders, pioneers, merchants, soldiers and politicians. Its gaming tables held faro and monte games, and its luncheons were considered the best in town. Located at the end of the Santa Fe Trail and the Camino Real, it was the scene of many celebrations.n 1846, when General Stephen Watts Kearny conquered New Mexico for the United States as part of the Mexican-American War, the fonda was taken over by Americans. For a few years it was known as The United States Hotel, but by 1850 it had changed its name to The Exchange.

As the only hotel in town, the Exchange was the site of many grand balls and receptions. John Fremont, Kit Carson, U.S. Grant, Rutherford Hayes, Lew Wallace and William Tecumseh Sherman are known to have stayed here.

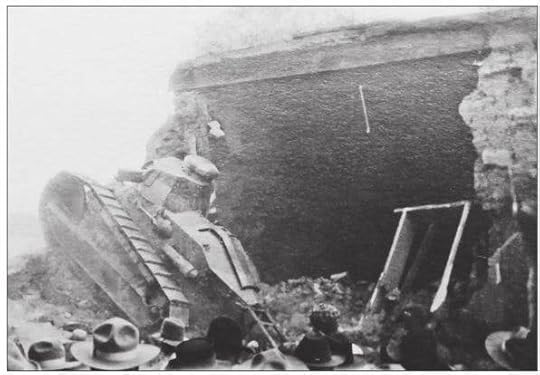

But by the turn of the twentieth century, the building that held the Exchange was no longer in its prime. New hotels, such as the Capital, the Palace, and De Vargas, had better amenities. In 1907, the Exchange was converted into a boarding house, which became seedier and seedier over the years. In 1917, a fire damaged much of the building. By 1919, it was slated for demolition.

The Exchange met her end during a gigantic Victory Bond Rally in April 1919. During the rally, all the shops in town closed and the citizens gathered in the Plaza to hear speeches by local dignitaries and World War I heroes. People who bought Victory Bonds valued at $100 or more were allowed to drive Mud Puppy, a two man tank that had seen action in the Argonne Forest. By the end of the rally, the corner entrance of the building was demolished. A year later, a new hotel, the La Fonda, rose from the ruins of the Exchange.

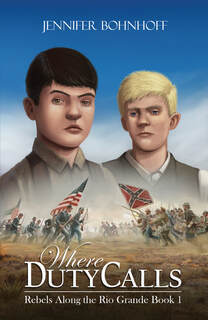

The Exchange met her end during a gigantic Victory Bond Rally in April 1919. During the rally, all the shops in town closed and the citizens gathered in the Plaza to hear speeches by local dignitaries and World War I heroes. People who bought Victory Bonds valued at $100 or more were allowed to drive Mud Puppy, a two man tank that had seen action in the Argonne Forest. By the end of the rally, the corner entrance of the building was demolished. A year later, a new hotel, the La Fonda, rose from the ruins of the Exchange.  Jennifer Bohnhoff writes historical fiction set in New Mexico. Where Duty Calls, book 1 of the Rebels Along the Rio Grande is about the Civil War. A Blaze of Poppies takes place during World War I.

Jennifer Bohnhoff writes historical fiction set in New Mexico. Where Duty Calls, book 1 of the Rebels Along the Rio Grande is about the Civil War. A Blaze of Poppies takes place during World War I.

Published on June 22, 2022 11:40

June 15, 2022

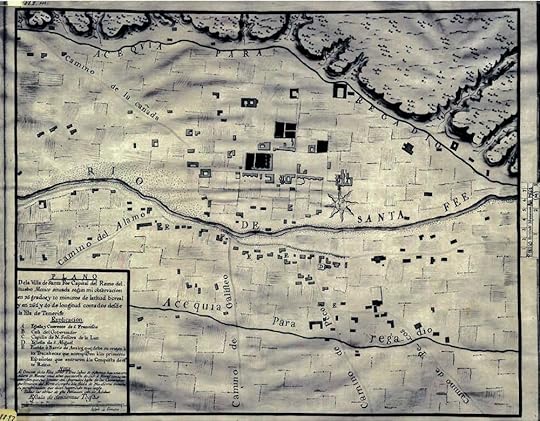

Vague and Unrecognized Maps of New Mexico

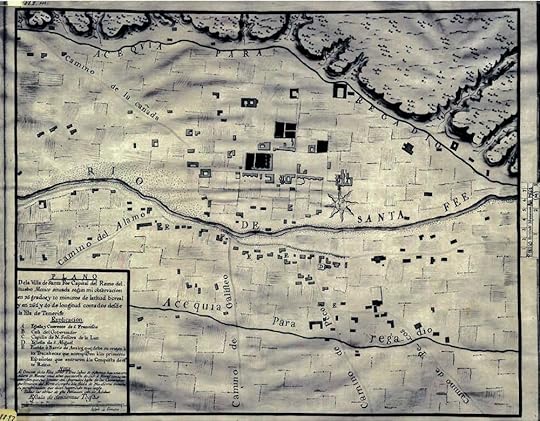

New Mexico had already been settled by Europeans for 314 years when it became the 47th state of the United States on January 6, 1912. During that long period, New Mexico’s borders changed repeatedly as Spain, France, Britain, United States, Mexico, Texas, and the Confederate States of America vied for control.Often, no one agreed on where the borders actually were.  Mexico or New Spain, published in London in 1777. Note that New Mexico is written across a vast, uncharted area above Mexico and the land between it and Louisiana is called “Great Space of Land unknown.” Courtesy Fray Angélico Chávez History Library. Spain laid claim to a vast area of North America when it established its New World empire in the 16th century. Most of what is now the central and western United States, including Arizona, Colorado, Utah, Texas, New Mexico, and beyond was called New Mexico. As Spain focused on settling Mexico and South America, the north remained unexplored, its boundaries undefined. In 1598, King Felipe II sent Juan de Onate, his soldiers and their families north, to establish a colony in the middle of New Mexico. Located in the upper Rio Grande, their missions were to pacify and convert the Indians and to discourage other Europeans, particularly the French, from settling their northern territories. The French threat ended after France’s defeat in the French & Indian Wars, when Louis XV ceded all of the Louisiana territory, except New Orleans, to Spain, who returned it to France some forty years later when Napoleon demanded it. Napoleon had promised that the land would never be sold to a third party, but he did exactly that a year later, selling it to the United States.

Mexico or New Spain, published in London in 1777. Note that New Mexico is written across a vast, uncharted area above Mexico and the land between it and Louisiana is called “Great Space of Land unknown.” Courtesy Fray Angélico Chávez History Library. Spain laid claim to a vast area of North America when it established its New World empire in the 16th century. Most of what is now the central and western United States, including Arizona, Colorado, Utah, Texas, New Mexico, and beyond was called New Mexico. As Spain focused on settling Mexico and South America, the north remained unexplored, its boundaries undefined. In 1598, King Felipe II sent Juan de Onate, his soldiers and their families north, to establish a colony in the middle of New Mexico. Located in the upper Rio Grande, their missions were to pacify and convert the Indians and to discourage other Europeans, particularly the French, from settling their northern territories. The French threat ended after France’s defeat in the French & Indian Wars, when Louis XV ceded all of the Louisiana territory, except New Orleans, to Spain, who returned it to France some forty years later when Napoleon demanded it. Napoleon had promised that the land would never be sold to a third party, but he did exactly that a year later, selling it to the United States.

Spain’s possession of Texas was uncontested until the United States purchased the Louisiana Territory in 1803. The U.S. claimed the Purchase included all the land between New Orleans and the Rio Grande including most of the New Mexico settlements. Spain claimed that New Mexico and Texas extended to the Missouri River, encompassing land all the way to present day Montana. Since the U.S. had no presence on the Rio Grande and Spain had none along the Missouri, neither country could enforce their claim. New Mexico’s Governor Fernando Chacon tried to force back Lewis and Clark’s expedition to chart the west, but hostile plains Indians drove him back. He did, however, manage to capture Lieutenant Zebulon Pike and his band of explorers in what is now southwestern Colorado in 1806. Pike and his men were treated well, and after a year’s interrogation were released in New Orleans.

Spain’s possession of Texas was uncontested until the United States purchased the Louisiana Territory in 1803. The U.S. claimed the Purchase included all the land between New Orleans and the Rio Grande including most of the New Mexico settlements. Spain claimed that New Mexico and Texas extended to the Missouri River, encompassing land all the way to present day Montana. Since the U.S. had no presence on the Rio Grande and Spain had none along the Missouri, neither country could enforce their claim. New Mexico’s Governor Fernando Chacon tried to force back Lewis and Clark’s expedition to chart the west, but hostile plains Indians drove him back. He did, however, manage to capture Lieutenant Zebulon Pike and his band of explorers in what is now southwestern Colorado in 1806. Pike and his men were treated well, and after a year’s interrogation were released in New Orleans.

When Mexico declared independence from Spain in 1821, it instituted two policies that increased American presence n New Mexico. First, it allowed trade along the Santa Fe trail.

Spain had forbidden New Mexico to trade with anyone but Mexico. Now Americans brought their influence, along with wagon trains full of goods and supplies from Missouri. Those merchants who settled in New Mexico and became influential in local society and politics. The Bent Brothers put their trading fort on the east bank of the Arkansas River in what is now Colorado because that river was the northeastern border of Mexican territory at the time.

The second decision the Mexican government did was invite Anglo-Americans to settle in the part of the territory known as Texas beginning in 1824. In less than a decade, Americans far outnumbered Hispanics in Texas. They never assimilated into the local culture and won independence in 1836. Mexican authorities never formally acknowledged the Republic of Texas, which claimed territory all the way to the Rio Grande.

Map published in Philadelphia in 1847 shows Texas’ extending to the east bank of the Rio Grande. Courtesy Fray Angélico Chávez History Library. But the Texans were not the only people trying to grab land from New Mexico. Soon after Brigham Young led the Mormons west to the Salt Lake Basin, he petitioned Congress to create a new state for his people. His proposed state, Deseret, included a bit of California coastline and nearly the entire western half of New Mexico. Instead, the federal government created a much smaller state and named it after the Ute tribe.

Map published in Philadelphia in 1847 shows Texas’ extending to the east bank of the Rio Grande. Courtesy Fray Angélico Chávez History Library. But the Texans were not the only people trying to grab land from New Mexico. Soon after Brigham Young led the Mormons west to the Salt Lake Basin, he petitioned Congress to create a new state for his people. His proposed state, Deseret, included a bit of California coastline and nearly the entire western half of New Mexico. Instead, the federal government created a much smaller state and named it after the Ute tribe.

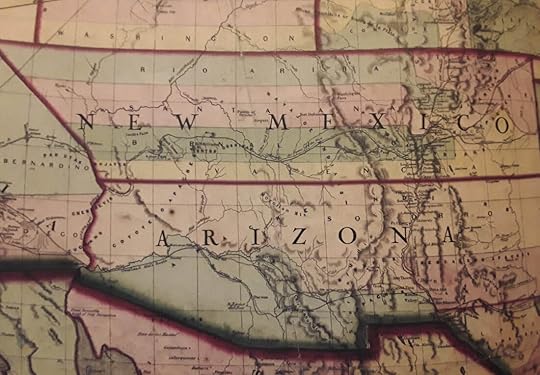

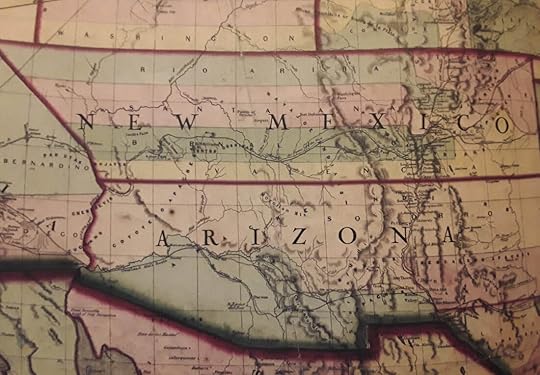

Map from Lost States: True Stories of Texlahoma, Transylvania, and other States That Never Made It, by Michael J. Trinklein. In 1861, Confederate Lieutenant Colonel John Baylor brought his 2nd Texas Cavalry Regiment into New Mexico. He split the territory in two horizontally, creating a Confederate Arizona in the south and a Union New Mexico in the north. This map was never acknowledged by the Union States.

Map from Lost States: True Stories of Texlahoma, Transylvania, and other States That Never Made It, by Michael J. Trinklein. In 1861, Confederate Lieutenant Colonel John Baylor brought his 2nd Texas Cavalry Regiment into New Mexico. He split the territory in two horizontally, creating a Confederate Arizona in the south and a Union New Mexico in the north. This map was never acknowledged by the Union States.

New Mexico became a U.S. territory after the Mexican American War. It fought off a Confederate invasion during the Civil War. However, it languished as a territory for decades. One reason was its name, which remains a confusion to many. In 1887, local leaders suggested switching the territory’s name to Montezuma in the hopes that it would no longer be assumed to be part of the country to our south. The also proposed renaming the territory Lincoln, but an association with the Lincoln County Wars made that inadvisable.

New Mexico became a U.S. territory after the Mexican American War. It fought off a Confederate invasion during the Civil War. However, it languished as a territory for decades. One reason was its name, which remains a confusion to many. In 1887, local leaders suggested switching the territory’s name to Montezuma in the hopes that it would no longer be assumed to be part of the country to our south. The also proposed renaming the territory Lincoln, but an association with the Lincoln County Wars made that inadvisable.

Map from Lost States: True Stories of Texlahoma, Transylvania, and other States That Never Made It, by Michael J. Trinklein. When New Mexico finally did enter the Union as a state, it was very much reduced in size. It's western half became the state of Arizona, and its east was Texas. Large portions of its northern border are now part of Colorado. And still there are countless people who don't know where New Mexico is and what country claims it. A native New Mexican, author Jennifer Bohnhoff isn't quite sure where she is most of the time. While her latest book Where Duty Calls is set in New Mexico during the Civil War, she is currently at work on a book about the Folsom people, who lived in New Mexico 10,000 years ago. Unfortunately, they left no maps.

Map from Lost States: True Stories of Texlahoma, Transylvania, and other States That Never Made It, by Michael J. Trinklein. When New Mexico finally did enter the Union as a state, it was very much reduced in size. It's western half became the state of Arizona, and its east was Texas. Large portions of its northern border are now part of Colorado. And still there are countless people who don't know where New Mexico is and what country claims it. A native New Mexican, author Jennifer Bohnhoff isn't quite sure where she is most of the time. While her latest book Where Duty Calls is set in New Mexico during the Civil War, she is currently at work on a book about the Folsom people, who lived in New Mexico 10,000 years ago. Unfortunately, they left no maps.

Mexico or New Spain, published in London in 1777. Note that New Mexico is written across a vast, uncharted area above Mexico and the land between it and Louisiana is called “Great Space of Land unknown.” Courtesy Fray Angélico Chávez History Library. Spain laid claim to a vast area of North America when it established its New World empire in the 16th century. Most of what is now the central and western United States, including Arizona, Colorado, Utah, Texas, New Mexico, and beyond was called New Mexico. As Spain focused on settling Mexico and South America, the north remained unexplored, its boundaries undefined. In 1598, King Felipe II sent Juan de Onate, his soldiers and their families north, to establish a colony in the middle of New Mexico. Located in the upper Rio Grande, their missions were to pacify and convert the Indians and to discourage other Europeans, particularly the French, from settling their northern territories. The French threat ended after France’s defeat in the French & Indian Wars, when Louis XV ceded all of the Louisiana territory, except New Orleans, to Spain, who returned it to France some forty years later when Napoleon demanded it. Napoleon had promised that the land would never be sold to a third party, but he did exactly that a year later, selling it to the United States.

Mexico or New Spain, published in London in 1777. Note that New Mexico is written across a vast, uncharted area above Mexico and the land between it and Louisiana is called “Great Space of Land unknown.” Courtesy Fray Angélico Chávez History Library. Spain laid claim to a vast area of North America when it established its New World empire in the 16th century. Most of what is now the central and western United States, including Arizona, Colorado, Utah, Texas, New Mexico, and beyond was called New Mexico. As Spain focused on settling Mexico and South America, the north remained unexplored, its boundaries undefined. In 1598, King Felipe II sent Juan de Onate, his soldiers and their families north, to establish a colony in the middle of New Mexico. Located in the upper Rio Grande, their missions were to pacify and convert the Indians and to discourage other Europeans, particularly the French, from settling their northern territories. The French threat ended after France’s defeat in the French & Indian Wars, when Louis XV ceded all of the Louisiana territory, except New Orleans, to Spain, who returned it to France some forty years later when Napoleon demanded it. Napoleon had promised that the land would never be sold to a third party, but he did exactly that a year later, selling it to the United States.

Spain’s possession of Texas was uncontested until the United States purchased the Louisiana Territory in 1803. The U.S. claimed the Purchase included all the land between New Orleans and the Rio Grande including most of the New Mexico settlements. Spain claimed that New Mexico and Texas extended to the Missouri River, encompassing land all the way to present day Montana. Since the U.S. had no presence on the Rio Grande and Spain had none along the Missouri, neither country could enforce their claim. New Mexico’s Governor Fernando Chacon tried to force back Lewis and Clark’s expedition to chart the west, but hostile plains Indians drove him back. He did, however, manage to capture Lieutenant Zebulon Pike and his band of explorers in what is now southwestern Colorado in 1806. Pike and his men were treated well, and after a year’s interrogation were released in New Orleans.

Spain’s possession of Texas was uncontested until the United States purchased the Louisiana Territory in 1803. The U.S. claimed the Purchase included all the land between New Orleans and the Rio Grande including most of the New Mexico settlements. Spain claimed that New Mexico and Texas extended to the Missouri River, encompassing land all the way to present day Montana. Since the U.S. had no presence on the Rio Grande and Spain had none along the Missouri, neither country could enforce their claim. New Mexico’s Governor Fernando Chacon tried to force back Lewis and Clark’s expedition to chart the west, but hostile plains Indians drove him back. He did, however, manage to capture Lieutenant Zebulon Pike and his band of explorers in what is now southwestern Colorado in 1806. Pike and his men were treated well, and after a year’s interrogation were released in New Orleans.When Mexico declared independence from Spain in 1821, it instituted two policies that increased American presence n New Mexico. First, it allowed trade along the Santa Fe trail.

Spain had forbidden New Mexico to trade with anyone but Mexico. Now Americans brought their influence, along with wagon trains full of goods and supplies from Missouri. Those merchants who settled in New Mexico and became influential in local society and politics. The Bent Brothers put their trading fort on the east bank of the Arkansas River in what is now Colorado because that river was the northeastern border of Mexican territory at the time.

The second decision the Mexican government did was invite Anglo-Americans to settle in the part of the territory known as Texas beginning in 1824. In less than a decade, Americans far outnumbered Hispanics in Texas. They never assimilated into the local culture and won independence in 1836. Mexican authorities never formally acknowledged the Republic of Texas, which claimed territory all the way to the Rio Grande.

Map published in Philadelphia in 1847 shows Texas’ extending to the east bank of the Rio Grande. Courtesy Fray Angélico Chávez History Library. But the Texans were not the only people trying to grab land from New Mexico. Soon after Brigham Young led the Mormons west to the Salt Lake Basin, he petitioned Congress to create a new state for his people. His proposed state, Deseret, included a bit of California coastline and nearly the entire western half of New Mexico. Instead, the federal government created a much smaller state and named it after the Ute tribe.

Map published in Philadelphia in 1847 shows Texas’ extending to the east bank of the Rio Grande. Courtesy Fray Angélico Chávez History Library. But the Texans were not the only people trying to grab land from New Mexico. Soon after Brigham Young led the Mormons west to the Salt Lake Basin, he petitioned Congress to create a new state for his people. His proposed state, Deseret, included a bit of California coastline and nearly the entire western half of New Mexico. Instead, the federal government created a much smaller state and named it after the Ute tribe. Map from Lost States: True Stories of Texlahoma, Transylvania, and other States That Never Made It, by Michael J. Trinklein. In 1861, Confederate Lieutenant Colonel John Baylor brought his 2nd Texas Cavalry Regiment into New Mexico. He split the territory in two horizontally, creating a Confederate Arizona in the south and a Union New Mexico in the north. This map was never acknowledged by the Union States.

Map from Lost States: True Stories of Texlahoma, Transylvania, and other States That Never Made It, by Michael J. Trinklein. In 1861, Confederate Lieutenant Colonel John Baylor brought his 2nd Texas Cavalry Regiment into New Mexico. He split the territory in two horizontally, creating a Confederate Arizona in the south and a Union New Mexico in the north. This map was never acknowledged by the Union States.  New Mexico became a U.S. territory after the Mexican American War. It fought off a Confederate invasion during the Civil War. However, it languished as a territory for decades. One reason was its name, which remains a confusion to many. In 1887, local leaders suggested switching the territory’s name to Montezuma in the hopes that it would no longer be assumed to be part of the country to our south. The also proposed renaming the territory Lincoln, but an association with the Lincoln County Wars made that inadvisable.

New Mexico became a U.S. territory after the Mexican American War. It fought off a Confederate invasion during the Civil War. However, it languished as a territory for decades. One reason was its name, which remains a confusion to many. In 1887, local leaders suggested switching the territory’s name to Montezuma in the hopes that it would no longer be assumed to be part of the country to our south. The also proposed renaming the territory Lincoln, but an association with the Lincoln County Wars made that inadvisable.  Map from Lost States: True Stories of Texlahoma, Transylvania, and other States That Never Made It, by Michael J. Trinklein. When New Mexico finally did enter the Union as a state, it was very much reduced in size. It's western half became the state of Arizona, and its east was Texas. Large portions of its northern border are now part of Colorado. And still there are countless people who don't know where New Mexico is and what country claims it. A native New Mexican, author Jennifer Bohnhoff isn't quite sure where she is most of the time. While her latest book Where Duty Calls is set in New Mexico during the Civil War, she is currently at work on a book about the Folsom people, who lived in New Mexico 10,000 years ago. Unfortunately, they left no maps.

Map from Lost States: True Stories of Texlahoma, Transylvania, and other States That Never Made It, by Michael J. Trinklein. When New Mexico finally did enter the Union as a state, it was very much reduced in size. It's western half became the state of Arizona, and its east was Texas. Large portions of its northern border are now part of Colorado. And still there are countless people who don't know where New Mexico is and what country claims it. A native New Mexican, author Jennifer Bohnhoff isn't quite sure where she is most of the time. While her latest book Where Duty Calls is set in New Mexico during the Civil War, she is currently at work on a book about the Folsom people, who lived in New Mexico 10,000 years ago. Unfortunately, they left no maps.

Published on June 15, 2022 23:00

June 13, 2022

A Chocolate Cup of Cheer

Chocolate has been on the menu in New Mexico for thousands of years. It has been used to seal deals, comfort and celebrate, show status, and just to enjoy. Some pottery found in the Four Corners region has the same chocolate residue that is found in ancient Olmec bowls. This indicates that the same trade routes that brought scarlet macaw feathers to Chaco Canyon also brought up chocolate.  The Spanish learned about chocolate from the Aztecs and took it with them when they explored the north.. In 1692, Diego de Vargas, the newly appointed Spanish Governor of New Mexico, met with a Pueblo leader named Luis Picuri in his tent. The meeting included drinking chocolate.

The Spanish learned about chocolate from the Aztecs and took it with them when they explored the north.. In 1692, Diego de Vargas, the newly appointed Spanish Governor of New Mexico, met with a Pueblo leader named Luis Picuri in his tent. The meeting included drinking chocolate.  Conquistador Hernan Cortez Experiencing Cacao Ritual Drinking cocoa became an important part of rituals in New Mexico.

Conquistador Hernan Cortez Experiencing Cacao Ritual Drinking cocoa became an important part of rituals in New Mexico.  Jicaras, or chocolate cups from Abo and Quarai New Mexico, 17th C. Picture taken at the History Museum in Santa Fe.

Jicaras, or chocolate cups from Abo and Quarai New Mexico, 17th C. Picture taken at the History Museum in Santa Fe.

Picture taken at the History Museum in Santa Fe. The Palace of the Governors, New Mexico’s History Museum, has on display some artifacts that are associated with chocolate. This storage jar was used to keep cocoa powder. New Mexico was quite isolated and life was rough here. People had few luxuries. The fact that cocoa was stored in such an ornate jar, with a metal lid indicated just how highly prized it was.

Picture taken at the History Museum in Santa Fe. The Palace of the Governors, New Mexico’s History Museum, has on display some artifacts that are associated with chocolate. This storage jar was used to keep cocoa powder. New Mexico was quite isolated and life was rough here. People had few luxuries. The fact that cocoa was stored in such an ornate jar, with a metal lid indicated just how highly prized it was.

One of the ways cocoa is used here in New Mexico is in champurrado, a thick Mexican drink that is especially popular on Dia del Muerto and during La Posada, the nine day festival leading up to Christmas.

When there's far too much celebrating going on in his house on Christmas Eve, Raul, one of the main characters in

Where Duty Calls

takes a cup of champurrado, a thick hot Mexican chocolate drink, outside and sits with his father. The two enjoy the silence outside together.

When there's far too much celebrating going on in his house on Christmas Eve, Raul, one of the main characters in

Where Duty Calls

takes a cup of champurrado, a thick hot Mexican chocolate drink, outside and sits with his father. The two enjoy the silence outside together.

It may be a little warm for champurrado where you are (it certainly is too hot here!) but here's the the recipe. I hope you enjoy it, if not to celebrate the publication of Where Duty Calls, then for some other special occasion. Champurrado

Ingredients

3 cups of water

2 cinnamon sticks

1 tsp. anise seeds

¼ cup masa harina

2 cups milk

1/4 cup Mexican chocolate, chopped

1/3 cup piloncillo, chopped

1. Put water, cinnamon sticks and anise star into a large saucepan and bring to boil. Remove from the heat, cover, and let steep for 1 hour, then remove the cinnamon sticks and anise by pouring through a sieve.

2. Return the water to the saucepot and put on low heat. Slowly add the masa harina to the warm water, whisking until combined. (a regular whisk will work just fine, but the authentic implement is wooden and is called a molinillo)

3. Add milk, chocolate, and piloncillo and simmer until chocolate is melted and sugar is dissolved. Serve immediately. Notes on ingredients: Masa harina is dried corn that has been treated with lye, then ground to the consistency of flour. Do not try to substitute cornmeal for the masa in this recipe. If you cannot find Mexican chocolate, you can substitute 2 oz. of any chocolate that is 60%-70% cacao. Piloncillo is unrefined sugar that has been packed into cones. If you cannot find it, you can substitute turbinado sugar or brown sugar. Champurrado was frothed with a molinillo, or chocolate whisk, The one above is from about 1830, and looks very similar to modern versions. The large end would be placed in the pot of hot chocolate and the thin handle was held between the palms of the hands and spun to make the beverage frothy.

Champurrado was frothed with a molinillo, or chocolate whisk, The one above is from about 1830, and looks very similar to modern versions. The large end would be placed in the pot of hot chocolate and the thin handle was held between the palms of the hands and spun to make the beverage frothy.

Where Duty Calls is the first in a trilogy of middle grade novels set in New Mexico during the American Civil War. Published by Kinkajou Press, a division of Artemesia Publishing, it is available in paperback and ebook online and in bookstores. Ask your local bookstore to order a copy if they don't have one in stock. Signed copies can be purchased directly from the author.

Where Duty Calls is the first in a trilogy of middle grade novels set in New Mexico during the American Civil War. Published by Kinkajou Press, a division of Artemesia Publishing, it is available in paperback and ebook online and in bookstores. Ask your local bookstore to order a copy if they don't have one in stock. Signed copies can be purchased directly from the author.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a native New Mexican who taught New Mexico History to Middle Schoolers. She now stays home and writes. She is available for class and group presentations on the Civil War in New Mexico.

The Spanish learned about chocolate from the Aztecs and took it with them when they explored the north.. In 1692, Diego de Vargas, the newly appointed Spanish Governor of New Mexico, met with a Pueblo leader named Luis Picuri in his tent. The meeting included drinking chocolate.

The Spanish learned about chocolate from the Aztecs and took it with them when they explored the north.. In 1692, Diego de Vargas, the newly appointed Spanish Governor of New Mexico, met with a Pueblo leader named Luis Picuri in his tent. The meeting included drinking chocolate.  Conquistador Hernan Cortez Experiencing Cacao Ritual Drinking cocoa became an important part of rituals in New Mexico.

Conquistador Hernan Cortez Experiencing Cacao Ritual Drinking cocoa became an important part of rituals in New Mexico.  Jicaras, or chocolate cups from Abo and Quarai New Mexico, 17th C. Picture taken at the History Museum in Santa Fe.

Jicaras, or chocolate cups from Abo and Quarai New Mexico, 17th C. Picture taken at the History Museum in Santa Fe.

Picture taken at the History Museum in Santa Fe. The Palace of the Governors, New Mexico’s History Museum, has on display some artifacts that are associated with chocolate. This storage jar was used to keep cocoa powder. New Mexico was quite isolated and life was rough here. People had few luxuries. The fact that cocoa was stored in such an ornate jar, with a metal lid indicated just how highly prized it was.

Picture taken at the History Museum in Santa Fe. The Palace of the Governors, New Mexico’s History Museum, has on display some artifacts that are associated with chocolate. This storage jar was used to keep cocoa powder. New Mexico was quite isolated and life was rough here. People had few luxuries. The fact that cocoa was stored in such an ornate jar, with a metal lid indicated just how highly prized it was.One of the ways cocoa is used here in New Mexico is in champurrado, a thick Mexican drink that is especially popular on Dia del Muerto and during La Posada, the nine day festival leading up to Christmas.

When there's far too much celebrating going on in his house on Christmas Eve, Raul, one of the main characters in

Where Duty Calls

takes a cup of champurrado, a thick hot Mexican chocolate drink, outside and sits with his father. The two enjoy the silence outside together.

When there's far too much celebrating going on in his house on Christmas Eve, Raul, one of the main characters in

Where Duty Calls

takes a cup of champurrado, a thick hot Mexican chocolate drink, outside and sits with his father. The two enjoy the silence outside together. It may be a little warm for champurrado where you are (it certainly is too hot here!) but here's the the recipe. I hope you enjoy it, if not to celebrate the publication of Where Duty Calls, then for some other special occasion. Champurrado

Ingredients

3 cups of water

2 cinnamon sticks

1 tsp. anise seeds

¼ cup masa harina

2 cups milk

1/4 cup Mexican chocolate, chopped

1/3 cup piloncillo, chopped

1. Put water, cinnamon sticks and anise star into a large saucepan and bring to boil. Remove from the heat, cover, and let steep for 1 hour, then remove the cinnamon sticks and anise by pouring through a sieve.

2. Return the water to the saucepot and put on low heat. Slowly add the masa harina to the warm water, whisking until combined. (a regular whisk will work just fine, but the authentic implement is wooden and is called a molinillo)

3. Add milk, chocolate, and piloncillo and simmer until chocolate is melted and sugar is dissolved. Serve immediately. Notes on ingredients: Masa harina is dried corn that has been treated with lye, then ground to the consistency of flour. Do not try to substitute cornmeal for the masa in this recipe. If you cannot find Mexican chocolate, you can substitute 2 oz. of any chocolate that is 60%-70% cacao. Piloncillo is unrefined sugar that has been packed into cones. If you cannot find it, you can substitute turbinado sugar or brown sugar.

Champurrado was frothed with a molinillo, or chocolate whisk, The one above is from about 1830, and looks very similar to modern versions. The large end would be placed in the pot of hot chocolate and the thin handle was held between the palms of the hands and spun to make the beverage frothy.

Champurrado was frothed with a molinillo, or chocolate whisk, The one above is from about 1830, and looks very similar to modern versions. The large end would be placed in the pot of hot chocolate and the thin handle was held between the palms of the hands and spun to make the beverage frothy.

Where Duty Calls is the first in a trilogy of middle grade novels set in New Mexico during the American Civil War. Published by Kinkajou Press, a division of Artemesia Publishing, it is available in paperback and ebook online and in bookstores. Ask your local bookstore to order a copy if they don't have one in stock. Signed copies can be purchased directly from the author.

Where Duty Calls is the first in a trilogy of middle grade novels set in New Mexico during the American Civil War. Published by Kinkajou Press, a division of Artemesia Publishing, it is available in paperback and ebook online and in bookstores. Ask your local bookstore to order a copy if they don't have one in stock. Signed copies can be purchased directly from the author. Jennifer Bohnhoff is a native New Mexican who taught New Mexico History to Middle Schoolers. She now stays home and writes. She is available for class and group presentations on the Civil War in New Mexico.

Published on June 13, 2022 07:22

June 8, 2022

Why did the Confederacy want New Mexico?

An illustration by Ian Bristow in Where Duty Calls. New Mexico is a dry and harsh land. We do not have the soil or the water to support plantations. Yet, in 1861 a Confederate force entered the state. Why would they bother? The answer lies with one man, who convinced the South that there were two good reasons for the Confederacy to want this territory. The U.S. Army prior to the Civil War was rather small. Its ten infantry regiments, four artillery regiments, three mounted infantry regiments, and two regiments each of cavalry and dragoons were scattered across the continent, with only 18 of the 197 companies garrisoned east of the Mississippi River. Of the 16,367 men in the Army, 1,108 were commissioned officers. When the Civil War broke out in April 1861, about 20% of these officers resigned. Most of these men were Southerners by birth and chose to join the Confederate Army.

An illustration by Ian Bristow in Where Duty Calls. New Mexico is a dry and harsh land. We do not have the soil or the water to support plantations. Yet, in 1861 a Confederate force entered the state. Why would they bother? The answer lies with one man, who convinced the South that there were two good reasons for the Confederacy to want this territory. The U.S. Army prior to the Civil War was rather small. Its ten infantry regiments, four artillery regiments, three mounted infantry regiments, and two regiments each of cavalry and dragoons were scattered across the continent, with only 18 of the 197 companies garrisoned east of the Mississippi River. Of the 16,367 men in the Army, 1,108 were commissioned officers. When the Civil War broke out in April 1861, about 20% of these officers resigned. Most of these men were Southerners by birth and chose to join the Confederate Army.

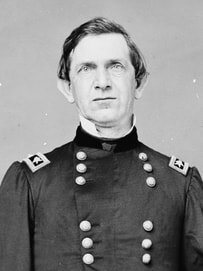

One of the men who resigned was Henry H. Sibley, a native of Louisiana who was serving New Mexico Territory with the 2nd U.S. Dragoons. Sibley resigned his commission on May 13, 1861, the day he was supposed to be promoted to Major. He accepted an appointment to colonel in the Confederate army three days later. A month after that, he became a Brigadier General, in command of a West Texas brigade of volunteer cavalry. He recruited and gathered his force in San Antonio and named it the Army of New Mexico. Taking New Mexico was only the first step in Sibley’s bold plan to capture the west for the Confederacy. And the New Mexico Campaign would cost the South almost nothing. Sibley assured Confederate President Jefferson Davis that his troops would be able to live off the land, resupplying themselves with Union stores as they captured first Fort Craig and then Fort Union. But even at no cost, why would the South want New Mexico? There were two reasons: access and idealism.

One of the men who resigned was Henry H. Sibley, a native of Louisiana who was serving New Mexico Territory with the 2nd U.S. Dragoons. Sibley resigned his commission on May 13, 1861, the day he was supposed to be promoted to Major. He accepted an appointment to colonel in the Confederate army three days later. A month after that, he became a Brigadier General, in command of a West Texas brigade of volunteer cavalry. He recruited and gathered his force in San Antonio and named it the Army of New Mexico. Taking New Mexico was only the first step in Sibley’s bold plan to capture the west for the Confederacy. And the New Mexico Campaign would cost the South almost nothing. Sibley assured Confederate President Jefferson Davis that his troops would be able to live off the land, resupplying themselves with Union stores as they captured first Fort Craig and then Fort Union. But even at no cost, why would the South want New Mexico? There were two reasons: access and idealism.

Gold prospectors in the Rocky Mountains of western Kansas Territory, near Pike's Peak in what would become Colorado New Mexico provided access to more desirable lands. One of those lands was Colorado, New Mexico’s neighbor to the north. If Sibley could wrest the Union Army from New Mexico, he could take control of Fort Union. In addition to having the greatest stockpile of supplies in the west, the fort could become a forward base of supply from which to continue north. Gold had been discovered in Colorado in 1858. Sibley argued that capturing a territory filled with gold and silver mines would help replenish the badly depleted Confederate treasury. The Rio Grande was a natural conduit to Colorado, guaranteeing water to the troops and their mounts as they traveled north.

Gold prospectors in the Rocky Mountains of western Kansas Territory, near Pike's Peak in what would become Colorado New Mexico provided access to more desirable lands. One of those lands was Colorado, New Mexico’s neighbor to the north. If Sibley could wrest the Union Army from New Mexico, he could take control of Fort Union. In addition to having the greatest stockpile of supplies in the west, the fort could become a forward base of supply from which to continue north. Gold had been discovered in Colorado in 1858. Sibley argued that capturing a territory filled with gold and silver mines would help replenish the badly depleted Confederate treasury. The Rio Grande was a natural conduit to Colorado, guaranteeing water to the troops and their mounts as they traveled north.

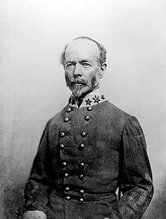

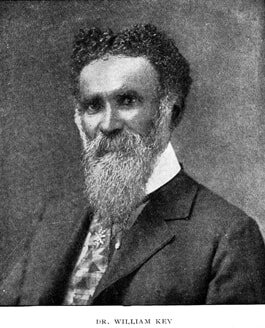

John Baylor, governor of Confederate Arizona. Once Sibley had captured the goldfields of Colorado, he planned to turn west and take the second on his list of desirable lands, California. By July of 1861, the Union Navy had established a blockade of all the major southern ports from Virginia to Texas. The Confederacy desperately needed to establish a new supply line to the South. Sibley argued that this could be done through the warm-water ports of California. The southern part of the territory, including the land acquired by the United State in the Gadsden Purchase of 1853, had already been secured for the Confederacy by Lieutenant John R. Baylor, who had ridden in and taken control in July, 1861. This land was the most promising for building a transcontinental railroad, which would then link the California ports to Southern cities.

John Baylor, governor of Confederate Arizona. Once Sibley had captured the goldfields of Colorado, he planned to turn west and take the second on his list of desirable lands, California. By July of 1861, the Union Navy had established a blockade of all the major southern ports from Virginia to Texas. The Confederacy desperately needed to establish a new supply line to the South. Sibley argued that this could be done through the warm-water ports of California. The southern part of the territory, including the land acquired by the United State in the Gadsden Purchase of 1853, had already been secured for the Confederacy by Lieutenant John R. Baylor, who had ridden in and taken control in July, 1861. This land was the most promising for building a transcontinental railroad, which would then link the California ports to Southern cities.

The deep water port of Los Angeles But acquiring Colorado and California for the South was not reason enough for Sibley to invade New Mexico. Tied into the need for a southern port and a railroad was the ideal of Manifest Destiny. In 1845, editor John Louis O'Sullivan had coined “Manifest Destiny” to promote the annexation of Texas and the acquisition of the Oregon territory. Americans began believing in a country that stretched from sea to shinning sea, from the Atlantic seaboard to the shores of the Pacific. When the country divided during the War, this dream was taken up by both the North and the South. New Mexico Territory would be part of the wide swath of land the Confederacy needed to prove their own destiny, both to themselves and to the other nations of the world.

The deep water port of Los Angeles But acquiring Colorado and California for the South was not reason enough for Sibley to invade New Mexico. Tied into the need for a southern port and a railroad was the ideal of Manifest Destiny. In 1845, editor John Louis O'Sullivan had coined “Manifest Destiny” to promote the annexation of Texas and the acquisition of the Oregon territory. Americans began believing in a country that stretched from sea to shinning sea, from the Atlantic seaboard to the shores of the Pacific. When the country divided during the War, this dream was taken up by both the North and the South. New Mexico Territory would be part of the wide swath of land the Confederacy needed to prove their own destiny, both to themselves and to the other nations of the world.  Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze, Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way (mural study, U.S. Capitol), 1861 In the end, Sibley's dreams and the dreams of the Confederacy could not overcome reality. The Army of New Mexico could not live off the land. They had far too much hoofstock for the amount of fodder available in the dry desert. The local population, which lived just above subsistence level in even the best of times, could not support the troops. After the war, in a letter to John McRae, father of the South Carolina-born Union Captain Alexander McRae, who fought bravely and was killed at the Battle of Valverde, General Sibley wrote “You will naturally speculate upon the causes of my precipitate evacuation of the Territory of New Mexico after it had been virtually conquered. My dear Sir, we beat the enemy whenever we encountered him. The famished country beat us.”

Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze, Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way (mural study, U.S. Capitol), 1861 In the end, Sibley's dreams and the dreams of the Confederacy could not overcome reality. The Army of New Mexico could not live off the land. They had far too much hoofstock for the amount of fodder available in the dry desert. The local population, which lived just above subsistence level in even the best of times, could not support the troops. After the war, in a letter to John McRae, father of the South Carolina-born Union Captain Alexander McRae, who fought bravely and was killed at the Battle of Valverde, General Sibley wrote “You will naturally speculate upon the causes of my precipitate evacuation of the Territory of New Mexico after it had been virtually conquered. My dear Sir, we beat the enemy whenever we encountered him. The famished country beat us.” Retired history teacher Jennifer Bohnhoff has written a middle grade novel about the Confederate invasion of New Mexico during the Civil War. Where Duty Calls, available from Kinkajou Press, a division of Artemesia Publishing, is the first in a trilogy of novels entitled Rebels Along the Rio Grande.

Retired history teacher Jennifer Bohnhoff has written a middle grade novel about the Confederate invasion of New Mexico during the Civil War. Where Duty Calls, available from Kinkajou Press, a division of Artemesia Publishing, is the first in a trilogy of novels entitled Rebels Along the Rio Grande.

Published on June 08, 2022 12:06

May 31, 2022

Burrying William Kemp

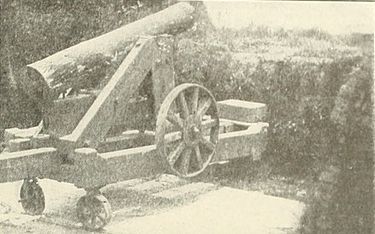

From The Civil War in Texas and New Mexico, by Steve Cotrell. In 1861, Confederate Brigadier General Henry Sibley led his Army of New Mexico, 3 regiments of Texas Mounted Volunteers, into New Mexico Territory. It was the first step in his plan to capture the entire southwest, including the Colorado goldfields and California’s deep-water ports. But things didn’t go as planned. Instead of taking the territory for the Confederacy, the campaign was an unmitigated disaster. Sibley’s starved soldiers retreated back to Texas, littering the desert and mountains with debris that souvenir hunters are still uncovering. Of the original 2,500-man brigade, only 1,500 made it back to San Antonio by the fall of 1862.

From The Civil War in Texas and New Mexico, by Steve Cotrell. In 1861, Confederate Brigadier General Henry Sibley led his Army of New Mexico, 3 regiments of Texas Mounted Volunteers, into New Mexico Territory. It was the first step in his plan to capture the entire southwest, including the Colorado goldfields and California’s deep-water ports. But things didn’t go as planned. Instead of taking the territory for the Confederacy, the campaign was an unmitigated disaster. Sibley’s starved soldiers retreated back to Texas, littering the desert and mountains with debris that souvenir hunters are still uncovering. Of the original 2,500-man brigade, only 1,500 made it back to San Antonio by the fall of 1862.  From Where Duty Calls. Illustration by Ian Bristow Like elsewhere in the Civil War, disease took more of Sibley’s soldiers than battle did. Altogether, two-thirds of the approximately 660,000 deaths of soldiers in the Civil War were caused by uncontrolled infectious diseases. Although malaria, common in the south, was less prominent in the dry desert, pneumonia, typhoid, diarrhea and dysentery were common among his troops. Sibley’s men were burying the dead before they even crossed the border into Union territory.

From Where Duty Calls. Illustration by Ian Bristow Like elsewhere in the Civil War, disease took more of Sibley’s soldiers than battle did. Altogether, two-thirds of the approximately 660,000 deaths of soldiers in the Civil War were caused by uncontrolled infectious diseases. Although malaria, common in the south, was less prominent in the dry desert, pneumonia, typhoid, diarrhea and dysentery were common among his troops. Sibley’s men were burying the dead before they even crossed the border into Union territory.

Jemmy. Ian Bristow, illustrator Jemmy Martin, a young Texan in my historical novel, Where Duty Calls, is not a soldier, but a packer, in charge of making sure the army’s supplies are loaded into his wagon correctly. Jemmy has a big heart that breaks every time he sees an animal or person die. He is particularly affected when William Kemp dies. On Jemmy’s first day in Sibley’s camp, William had cut his own bar of soap in two so that Jemmy would have some. When William dies of pneumonia, Jemmy is overcome with sorrow and guilt. While Jemmy is fictitious, William Kemp is not. Official Confederate records show that a private William Kemp died of pneumonia on February 12, 1862. He was buried at the side of the trail somewhere south of Fort Craig, New Mexico. His grave was unmarked and has never been found or identified. In Where Duty Calls, Jemmy breaks apart wooden food crates to build William’s coffin. Although he wants to carefully pull out the nails so he can reuse both the wood and the nails, his grief gets the better of him. In his frustration, Jemmy pounds the nails so hard that he bends them and splits the wood.

Jemmy. Ian Bristow, illustrator Jemmy Martin, a young Texan in my historical novel, Where Duty Calls, is not a soldier, but a packer, in charge of making sure the army’s supplies are loaded into his wagon correctly. Jemmy has a big heart that breaks every time he sees an animal or person die. He is particularly affected when William Kemp dies. On Jemmy’s first day in Sibley’s camp, William had cut his own bar of soap in two so that Jemmy would have some. When William dies of pneumonia, Jemmy is overcome with sorrow and guilt. While Jemmy is fictitious, William Kemp is not. Official Confederate records show that a private William Kemp died of pneumonia on February 12, 1862. He was buried at the side of the trail somewhere south of Fort Craig, New Mexico. His grave was unmarked and has never been found or identified. In Where Duty Calls, Jemmy breaks apart wooden food crates to build William’s coffin. Although he wants to carefully pull out the nails so he can reuse both the wood and the nails, his grief gets the better of him. In his frustration, Jemmy pounds the nails so hard that he bends them and splits the wood. The Mourners. From Hardtack and Coffee by John D. Billings Just as William Kemp is based on a real person, the idea of making a coffin from food crates is not a figment of my imagination. Wood was a rare and precious commodity in New Mexico Territory. Burying every dead person in a coffin would be a terrible waste in the desert, where wood was needed for fires to cook food and keep the troops warm. In I Married A Soldier, a memoir of Army life in the Southwest during the 1850s-1870s, Lydia Spencer Lane explains that wood was so scarce that it was customary for those who lived in New Mexico to not bury their dead in coffins. She explains that in Santa Fe, the dead were carried to church in a coffin, but before burial the body was removed and rolled in old blankets. Thus, coffins could be used and reused indefinitely.

The Mourners. From Hardtack and Coffee by John D. Billings Just as William Kemp is based on a real person, the idea of making a coffin from food crates is not a figment of my imagination. Wood was a rare and precious commodity in New Mexico Territory. Burying every dead person in a coffin would be a terrible waste in the desert, where wood was needed for fires to cook food and keep the troops warm. In I Married A Soldier, a memoir of Army life in the Southwest during the 1850s-1870s, Lydia Spencer Lane explains that wood was so scarce that it was customary for those who lived in New Mexico to not bury their dead in coffins. She explains that in Santa Fe, the dead were carried to church in a coffin, but before burial the body was removed and rolled in old blankets. Thus, coffins could be used and reused indefinitely.

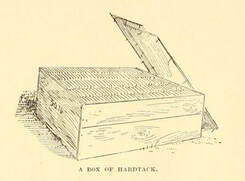

A Box of Hardtack. From Hardtack and Coffee by John D. Billings However, Ms. Lane elaborates that the practice of burying the dead without a coffin was not acceptable to people who had been raised in the East, who did everything within their power to create coffins for their dead. When there was not enough lumber at hand to make a coffin, she explains, packing boxes and commissary boxes were used. She relates the story of one officer who died at a post in Texas and was carried to his final resting place in a very rough coffin which had marked, in great black letters along the side, "200 lbs. bacon."

A Box of Hardtack. From Hardtack and Coffee by John D. Billings However, Ms. Lane elaborates that the practice of burying the dead without a coffin was not acceptable to people who had been raised in the East, who did everything within their power to create coffins for their dead. When there was not enough lumber at hand to make a coffin, she explains, packing boxes and commissary boxes were used. She relates the story of one officer who died at a post in Texas and was carried to his final resting place in a very rough coffin which had marked, in great black letters along the side, "200 lbs. bacon."

From Where Duty Calls. Illustrated by Ian Bristow In Where Duty Calls, when the grave is deep enough and the coffin complete, the entire troop follows Willie the drummer boy out of camp as he drums a funeral march. They lower William Kemp’s coffin into the hole, then sing When I can read my title clear. Written by Isaac Watts, an English Congregational minister, hymn writer, theologian, and logician who lived between 1674 and 1748, it was very popular at the time of the Civil War. Other hymn written by Watts, among them When I Survey the Wondrous Cross, Joy to the World, and Our God, Our Help in Ages Past have better endured the passing of time.

From Where Duty Calls. Illustrated by Ian Bristow In Where Duty Calls, when the grave is deep enough and the coffin complete, the entire troop follows Willie the drummer boy out of camp as he drums a funeral march. They lower William Kemp’s coffin into the hole, then sing When I can read my title clear. Written by Isaac Watts, an English Congregational minister, hymn writer, theologian, and logician who lived between 1674 and 1748, it was very popular at the time of the Civil War. Other hymn written by Watts, among them When I Survey the Wondrous Cross, Joy to the World, and Our God, Our Help in Ages Past have better endured the passing of time.When I can read my title clear

to mansions in the skies,

I bid farewell to every fear,

and wipe my weeping eyes.

Let cares, like a wild deluge come,

and storms of sorrow fall!

May I but safely reach my home,

my God, my heav’n, my All.

Jennifer Bohnhoff, a former high school and middle school history teacher, is the author of several middle grade historical fiction novels. Where Duty Calls is the first in a trilogy of novels set in New Mexico during the Civil War and is published by Kinkajou Press, a division of Artemesia Publishing.

Jennifer Bohnhoff, a former high school and middle school history teacher, is the author of several middle grade historical fiction novels. Where Duty Calls is the first in a trilogy of novels set in New Mexico during the Civil War and is published by Kinkajou Press, a division of Artemesia Publishing.

Published on May 31, 2022 19:27

May 20, 2022

The Retablo of San Miguel Chapel

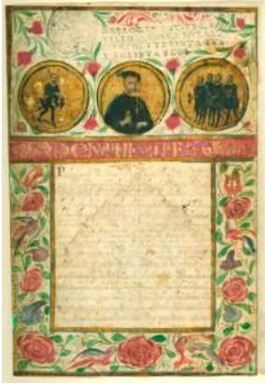

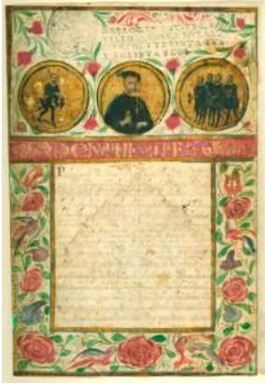

The retablo behind the altar in San Miguel Chapel, the oldest church in the United States, is a unique work of art that reflects New Mexico’s multi-cultural heritage.  The word retablo comes from the Latin retro-tabula, literally meaning behind the table, or altar. Originally, the word retablo referred to paintings placed behind the altar of churches in the early Middle Ages. Sometime during the 12th and 13th centuries, the term came to mean any painted sacred image, including those kept in private homes. Santos, one form of retablos, are representations of holy figures, such as members of the Holy Family, or saints.

The word retablo comes from the Latin retro-tabula, literally meaning behind the table, or altar. Originally, the word retablo referred to paintings placed behind the altar of churches in the early Middle Ages. Sometime during the 12th and 13th centuries, the term came to mean any painted sacred image, including those kept in private homes. Santos, one form of retablos, are representations of holy figures, such as members of the Holy Family, or saints.

San Miguel Retablo by José Rafael Aragón In the first years of Spanish occupation, religious art was either imported into New Mexico from Mexico or created in New Mexico by the Franciscan Friars. The art that was imported was influenced by European art, particularly the art of the Renaissance and Baroque periods, while the art created by local monks was often less sophisticated. By the late eighteenth century, local New Mexicans began making their own religious art. Local santeros, or saint makers like José Rafael Aragón (active 1820-1862) developed a simple, primitive style that is distinctively New Mexican. The retablo in San Miguel Chapel, a carved and painted wooden altar screen studded with paintings and sculptures, was given to the chapel in 1798, by Don Antonio José Ortiz, who had become a devout benefactor of the church after his father was killed by Comanches in 1769. It contains nine works of art, arranged in three rows of three pieces each, and is flanked by columns. The style of the art is varied, demonstrating the different schools of art that have melded into New Mexican tradition over the centuries.

San Miguel Retablo by José Rafael Aragón In the first years of Spanish occupation, religious art was either imported into New Mexico from Mexico or created in New Mexico by the Franciscan Friars. The art that was imported was influenced by European art, particularly the art of the Renaissance and Baroque periods, while the art created by local monks was often less sophisticated. By the late eighteenth century, local New Mexicans began making their own religious art. Local santeros, or saint makers like José Rafael Aragón (active 1820-1862) developed a simple, primitive style that is distinctively New Mexican. The retablo in San Miguel Chapel, a carved and painted wooden altar screen studded with paintings and sculptures, was given to the chapel in 1798, by Don Antonio José Ortiz, who had become a devout benefactor of the church after his father was killed by Comanches in 1769. It contains nine works of art, arranged in three rows of three pieces each, and is flanked by columns. The style of the art is varied, demonstrating the different schools of art that have melded into New Mexican tradition over the centuries.

The altar screen itself is believed to have been created by an unnamed artist referred to as the Laguna Santero. Active between 1776 and 1815, scholars think he may have been from southern Mexico, as his work reflects the Baroque style popular there. He is credited with seven other altar screens including the one in Laguna Pueblo’s Chapel de San Jose de Gracia, and the one in Acoma Pueblo’s San Esteban Church.

San Antonio The bottom row contains three bultos, or painted wooden statues. The bulto on the left is of an unidentified saint and is believed to have been carved in New Mexico in the nineteenth century. Scholars know that the center bulto, a Statue of the Archangel Michael, predates 1709, because records indicate it was carried throughout New Mexico to solicit donations for the Chapel’s 1710 reconstruction. It was most likely carved in Mexico and is much more ornate than the other bultos. The bulto on the right is New Mexican, from the early nineteenth century, and depicts San Antonio, or Saint Anthony, the saint whose name graces more place names in New Mexico than any other.

San Antonio The bottom row contains three bultos, or painted wooden statues. The bulto on the left is of an unidentified saint and is believed to have been carved in New Mexico in the nineteenth century. Scholars know that the center bulto, a Statue of the Archangel Michael, predates 1709, because records indicate it was carried throughout New Mexico to solicit donations for the Chapel’s 1710 reconstruction. It was most likely carved in Mexico and is much more ornate than the other bultos. The bulto on the right is New Mexican, from the early nineteenth century, and depicts San Antonio, or Saint Anthony, the saint whose name graces more place names in New Mexico than any other.

St. Francis The retablo has four oval paintings that are far more European looking than New Mexican. These four paintings might be part of a set of eight that were listed in a 1776 inventory and were presented to the Chapel by the Viceroyalty of New Spain. The one above the bulto of San Antonio depicts San Luis Rey, Saint Louis, or Lois IX, who was King of France from 1226 to 1270 and participated in both the Seventh and Eighth Crusades. Above him is Santa Clara, or Saint Clare of Assisi. A contemporary of Saint Francis, Clare was the co-founder of the Franciscan order of nuns, the Poor Clares. On the other side of the altar screen is an oval depicting San Francisco, or Saint Francis of Assisi, whose name graces the cathedral in Santa Fe. A painting of Santa Teresa, or Saint Teresa of Avila is above the one of St. Francis..

St. Francis The retablo has four oval paintings that are far more European looking than New Mexican. These four paintings might be part of a set of eight that were listed in a 1776 inventory and were presented to the Chapel by the Viceroyalty of New Spain. The one above the bulto of San Antonio depicts San Luis Rey, Saint Louis, or Lois IX, who was King of France from 1226 to 1270 and participated in both the Seventh and Eighth Crusades. Above him is Santa Clara, or Saint Clare of Assisi. A contemporary of Saint Francis, Clare was the co-founder of the Franciscan order of nuns, the Poor Clares. On the other side of the altar screen is an oval depicting San Francisco, or Saint Francis of Assisi, whose name graces the cathedral in Santa Fe. A painting of Santa Teresa, or Saint Teresa of Avila is above the one of St. Francis..

The center of the altar screen has two larger paintings the one on the top is of San Miguel or the Archangel Michael and was painted by Bernardo Miera y Pacheco, a Spanish-born artist, mapmaker, and civic leader, in 1755. Below it is a nineteenth century Mexican painting of Christ the Nazarene. Both of these paintings are a little more primitive in style than the oval paintings.

The center of the altar screen has two larger paintings the one on the top is of San Miguel or the Archangel Michael and was painted by Bernardo Miera y Pacheco, a Spanish-born artist, mapmaker, and civic leader, in 1755. Below it is a nineteenth century Mexican painting of Christ the Nazarene. Both of these paintings are a little more primitive in style than the oval paintings.

Although New Mexican religious art may have begun with imports from Europe and Mexico, the isolation of this northern outpost of the Spanish realm soon developed an art that was specific to it. New Mexican art is unique, and both beautiful in its simplicity and generous in its acceptance of outside influences.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a native New Mexican who taught New Mexico History at the Middle School level. She is now retired and writing. Her next novel, Where Duty Calls, is historical fiction set in New Mexico during the Civil War, and will be published by Kinkajou, a division of Artemesia Publishing, In June 2022.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a native New Mexican who taught New Mexico History at the Middle School level. She is now retired and writing. Her next novel, Where Duty Calls, is historical fiction set in New Mexico during the Civil War, and will be published by Kinkajou, a division of Artemesia Publishing, In June 2022.

The word retablo comes from the Latin retro-tabula, literally meaning behind the table, or altar. Originally, the word retablo referred to paintings placed behind the altar of churches in the early Middle Ages. Sometime during the 12th and 13th centuries, the term came to mean any painted sacred image, including those kept in private homes. Santos, one form of retablos, are representations of holy figures, such as members of the Holy Family, or saints.

The word retablo comes from the Latin retro-tabula, literally meaning behind the table, or altar. Originally, the word retablo referred to paintings placed behind the altar of churches in the early Middle Ages. Sometime during the 12th and 13th centuries, the term came to mean any painted sacred image, including those kept in private homes. Santos, one form of retablos, are representations of holy figures, such as members of the Holy Family, or saints.  San Miguel Retablo by José Rafael Aragón In the first years of Spanish occupation, religious art was either imported into New Mexico from Mexico or created in New Mexico by the Franciscan Friars. The art that was imported was influenced by European art, particularly the art of the Renaissance and Baroque periods, while the art created by local monks was often less sophisticated. By the late eighteenth century, local New Mexicans began making their own religious art. Local santeros, or saint makers like José Rafael Aragón (active 1820-1862) developed a simple, primitive style that is distinctively New Mexican. The retablo in San Miguel Chapel, a carved and painted wooden altar screen studded with paintings and sculptures, was given to the chapel in 1798, by Don Antonio José Ortiz, who had become a devout benefactor of the church after his father was killed by Comanches in 1769. It contains nine works of art, arranged in three rows of three pieces each, and is flanked by columns. The style of the art is varied, demonstrating the different schools of art that have melded into New Mexican tradition over the centuries.

San Miguel Retablo by José Rafael Aragón In the first years of Spanish occupation, religious art was either imported into New Mexico from Mexico or created in New Mexico by the Franciscan Friars. The art that was imported was influenced by European art, particularly the art of the Renaissance and Baroque periods, while the art created by local monks was often less sophisticated. By the late eighteenth century, local New Mexicans began making their own religious art. Local santeros, or saint makers like José Rafael Aragón (active 1820-1862) developed a simple, primitive style that is distinctively New Mexican. The retablo in San Miguel Chapel, a carved and painted wooden altar screen studded with paintings and sculptures, was given to the chapel in 1798, by Don Antonio José Ortiz, who had become a devout benefactor of the church after his father was killed by Comanches in 1769. It contains nine works of art, arranged in three rows of three pieces each, and is flanked by columns. The style of the art is varied, demonstrating the different schools of art that have melded into New Mexican tradition over the centuries. The altar screen itself is believed to have been created by an unnamed artist referred to as the Laguna Santero. Active between 1776 and 1815, scholars think he may have been from southern Mexico, as his work reflects the Baroque style popular there. He is credited with seven other altar screens including the one in Laguna Pueblo’s Chapel de San Jose de Gracia, and the one in Acoma Pueblo’s San Esteban Church.

San Antonio The bottom row contains three bultos, or painted wooden statues. The bulto on the left is of an unidentified saint and is believed to have been carved in New Mexico in the nineteenth century. Scholars know that the center bulto, a Statue of the Archangel Michael, predates 1709, because records indicate it was carried throughout New Mexico to solicit donations for the Chapel’s 1710 reconstruction. It was most likely carved in Mexico and is much more ornate than the other bultos. The bulto on the right is New Mexican, from the early nineteenth century, and depicts San Antonio, or Saint Anthony, the saint whose name graces more place names in New Mexico than any other.

San Antonio The bottom row contains three bultos, or painted wooden statues. The bulto on the left is of an unidentified saint and is believed to have been carved in New Mexico in the nineteenth century. Scholars know that the center bulto, a Statue of the Archangel Michael, predates 1709, because records indicate it was carried throughout New Mexico to solicit donations for the Chapel’s 1710 reconstruction. It was most likely carved in Mexico and is much more ornate than the other bultos. The bulto on the right is New Mexican, from the early nineteenth century, and depicts San Antonio, or Saint Anthony, the saint whose name graces more place names in New Mexico than any other.

St. Francis The retablo has four oval paintings that are far more European looking than New Mexican. These four paintings might be part of a set of eight that were listed in a 1776 inventory and were presented to the Chapel by the Viceroyalty of New Spain. The one above the bulto of San Antonio depicts San Luis Rey, Saint Louis, or Lois IX, who was King of France from 1226 to 1270 and participated in both the Seventh and Eighth Crusades. Above him is Santa Clara, or Saint Clare of Assisi. A contemporary of Saint Francis, Clare was the co-founder of the Franciscan order of nuns, the Poor Clares. On the other side of the altar screen is an oval depicting San Francisco, or Saint Francis of Assisi, whose name graces the cathedral in Santa Fe. A painting of Santa Teresa, or Saint Teresa of Avila is above the one of St. Francis..

St. Francis The retablo has four oval paintings that are far more European looking than New Mexican. These four paintings might be part of a set of eight that were listed in a 1776 inventory and were presented to the Chapel by the Viceroyalty of New Spain. The one above the bulto of San Antonio depicts San Luis Rey, Saint Louis, or Lois IX, who was King of France from 1226 to 1270 and participated in both the Seventh and Eighth Crusades. Above him is Santa Clara, or Saint Clare of Assisi. A contemporary of Saint Francis, Clare was the co-founder of the Franciscan order of nuns, the Poor Clares. On the other side of the altar screen is an oval depicting San Francisco, or Saint Francis of Assisi, whose name graces the cathedral in Santa Fe. A painting of Santa Teresa, or Saint Teresa of Avila is above the one of St. Francis..

The center of the altar screen has two larger paintings the one on the top is of San Miguel or the Archangel Michael and was painted by Bernardo Miera y Pacheco, a Spanish-born artist, mapmaker, and civic leader, in 1755. Below it is a nineteenth century Mexican painting of Christ the Nazarene. Both of these paintings are a little more primitive in style than the oval paintings.

The center of the altar screen has two larger paintings the one on the top is of San Miguel or the Archangel Michael and was painted by Bernardo Miera y Pacheco, a Spanish-born artist, mapmaker, and civic leader, in 1755. Below it is a nineteenth century Mexican painting of Christ the Nazarene. Both of these paintings are a little more primitive in style than the oval paintings.Although New Mexican religious art may have begun with imports from Europe and Mexico, the isolation of this northern outpost of the Spanish realm soon developed an art that was specific to it. New Mexican art is unique, and both beautiful in its simplicity and generous in its acceptance of outside influences.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a native New Mexican who taught New Mexico History at the Middle School level. She is now retired and writing. Her next novel, Where Duty Calls, is historical fiction set in New Mexico during the Civil War, and will be published by Kinkajou, a division of Artemesia Publishing, In June 2022.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a native New Mexican who taught New Mexico History at the Middle School level. She is now retired and writing. Her next novel, Where Duty Calls, is historical fiction set in New Mexico during the Civil War, and will be published by Kinkajou, a division of Artemesia Publishing, In June 2022.

Published on May 20, 2022 12:31

May 10, 2022

Civil War Homespun

Homespun is cloth that is made entirely at home. It is an incredibly labor intensive project, but it became very popular in the South during the Civil War for both practical and patriotic reasons.

Homespun is cloth that is made entirely at home. It is an incredibly labor intensive project, but it became very popular in the South during the Civil War for both practical and patriotic reasons.To make cotton homespun, the first thing that must be done is to pull the seeds from the cotton, either by hand or with the use of cards. Then, the carded cotton needs to be spun, dyed, and woven. It is estimated that it would take an estimated 360 hours of labor to make 30 yards of homespun fabric.

By the time of the Civil War, home spinning and weaving had fallen out of common practice. Diaries and newspapers of the time mention women taking spinning wheels out of the attic and learning to spin and weave. In the South, many of the larger homes had slaves who did their spinning and weaving.

.

The homespun dress became one of the symbols of the hard scrabble life many Southerners experienced during the Civil War. But before the Union blockade made homespun imperative, it was a sign of pride. Just as Americans had shown their opposition to the British by producing homespun fabrics during the American Revolution, Southern women made their homespun into a statement of their patriotism to the south. The song “The Southern Girl or The Homespun Dress” became one of the most popular songs in the Confederacy. Attributed to Carrie Belle Sinclair, the song praises women for wearing homespun dresses in support of the South during the Civil War.

In Where Duty Calls, my middle grade novel set in New Mexico during the Civil War, the Confederates encamped near Fort Craig a few nights before the Battle of Valverde are sitting around a campfire when they sing “The Homespun Dress.” One of the soldiers brags that he is going to pull down the Union flag from Fort Craig and make a dress out of it to present to his wife. While that wouldn’t strictly be a homespun dress, it surely would have been a source of great pride for the soldier and wife.

THE HOMESPUN DRESS

by Carrie Belle Sinclair

(born 1839)

Oh, yes, I am a Southern girl, And glory in the name, And boast it with far greater pride

Than glittering wealth and fame.

We envy not the Northern girl Her robes of beauty rare,

Though diamonds grace her snowy neck

And pearls bedeck her hair.

CHORUS: Hurrah! Hurrah! For the sunny South so dear; Three cheers for the homespun dress The Southern ladies wear!

The homespun dress is plain, I know, My hat's palmetto, too; But then it shows what Southern girls For Southern rights will do.

We send the bravest of our land To battle with the foe,

And we will lend a helping hand-- We love the South, you know

CHORUS

Now Northern goods are out of date; And since old Abe's blockade,

We Southern girls can be content With goods that's Southern made.

We send our sweethearts to the war; But, dear girls, never mind--

Your soldier-love will ne'er forget The girl he left behind.--

CHORUS

The soldier is the lad for me-- A brave heart I adore;

And when the sunny South is free, And when fighting is no more,

I'll choose me then a lover brave From all that gallant band;

The soldier lad I love the best Shall have my heart and hand.--

CHORUS

The Southern land's a glorious land, And has a glorious cause;

Then cheer, three cheers for Southern rights, And for the Southern boys!

We scorn to wear a bit of silk, A bit of Northern lace,

But make our homespun dresses up, And wear them with a grace.--

CHORUS

And now, young man, a word to you: If you would win the fair,

Go to the field where honor calls, And win your lady there.

Remember that our brightest smiles Are for the true and brave,

And that our tears are all for those Who fill a soldier's grave.--CHORUS

from

http://www.civilwarpoetry.org/confederate/songs/homespun.html

Where Duty Calls will be published by Kinkajou Press in June 2022.

For more information on homespun, see txcwcivilian.org/homespun/

Published on May 10, 2022 11:43

May 6, 2022

San Miguel Chapel: Oldest Church in the U.S.

Last week I drove to Santa Fe and visited some of the oldest buildings in the United States. One of those building was San Miguel Chapel.