Jennifer Bohnhoff's Blog, page 16

October 6, 2022

The Big Guy/ Little Guy Trope in Middle Grade Literature and Beyond

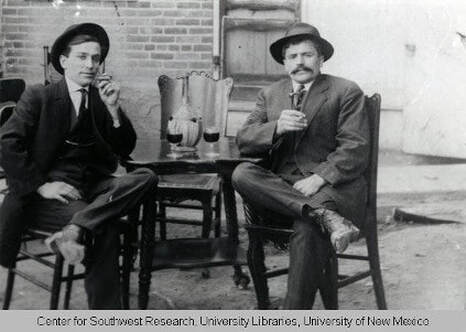

Merriam Webster defines a trope as a recurring element or a frequently used plot device in a work of literature or art. One common trope in not only literature but in cartoons is the mismatched duo, particularly a big guy partnered with a little guy. Often the smaller character is also physically weaker and needs the protection of his big friend. In return, he supplies the ideas that move the story forward. The big guy, often a misunderstood gentle giant or suffering a mental deficiency or disability, needs his little buddy to keep him out of trouble.

The big guy/little guy partnership has been used repeatedly in cartoons. When my sons were little, the TV cartoon that used this trope most obviously was Pinky and the Brain. The cartoon focused on two genetically enhanced laboratory mice who resided in a cage inside the Acme Labs research facility. Brain, the littler of the two mice, was highly intelligent, self-centered and scheming. Pinky was Brain’s sweet-natured but feeble-minded henchman. In every episode, Brain devised a new plan to take over the world, but his plans always failed, with hilarious results. Not all works that use the big guy/ little guy trope are funny, however. Probably the most famous and most literary of the trope’s treatments has been in

Of Mice and Men,

John Steinbeck’s 1937 novella. In it, George Milton is the little, smart guy who tries to protect Lennie Small, a slow thinking giant of a man who does not understand his own strength. The two displaced ranch workers move from job to job in Depression-era California, until fate catches up to them and Lennie can no longer protect his friend. The story is a tragedy and appears on the American Library Association's list of the Most Challenged Books of the 21st Century because many consider the material both offensive and racist, but it is also a beautiful depiction of the difficulties some people seem to never be able to shrug off, and the importance of watching after each other. It is a book that is, by turns, noble and base, vulgar and tender, and is frequently taught in high school courses. I consider it a little too mature for middle school readers, but hope that middle schoolers will have the chance to encounter it when they are older.

Not all works that use the big guy/ little guy trope are funny, however. Probably the most famous and most literary of the trope’s treatments has been in

Of Mice and Men,

John Steinbeck’s 1937 novella. In it, George Milton is the little, smart guy who tries to protect Lennie Small, a slow thinking giant of a man who does not understand his own strength. The two displaced ranch workers move from job to job in Depression-era California, until fate catches up to them and Lennie can no longer protect his friend. The story is a tragedy and appears on the American Library Association's list of the Most Challenged Books of the 21st Century because many consider the material both offensive and racist, but it is also a beautiful depiction of the difficulties some people seem to never be able to shrug off, and the importance of watching after each other. It is a book that is, by turns, noble and base, vulgar and tender, and is frequently taught in high school courses. I consider it a little too mature for middle school readers, but hope that middle schoolers will have the chance to encounter it when they are older.

A book that features the big guy/ little guy trope, but is appropriate for middle school readers is Rodman Philbrick’s Freak the Mighty (Scholastic Paperbacks; Reprint edition, June 1, 2001, ISBN-13: 978-0439286060) In this novel, the big guy is Max, a teenage giant with a learning disability and a terrible secret. The little guy is Kevin, whose tiny body is wracked with a syndrome that is slowly killing him. Together, they are Freak the Mighty, and they can overcome bullies and brutes. This story does not end up happily, either, but the reader is left with a sense of hope for the future. The book was made into a movie titled

The Mighty

, and stars Kieran Culkin and an all-star cast. When I taught middle school Language Arts, this was one of my favorite books to share. The movie to book comparison always led to good discussions on how characters were presented and what and why certain plots lines, scenes and themes were left out of the movie version.

A book that features the big guy/ little guy trope, but is appropriate for middle school readers is Rodman Philbrick’s Freak the Mighty (Scholastic Paperbacks; Reprint edition, June 1, 2001, ISBN-13: 978-0439286060) In this novel, the big guy is Max, a teenage giant with a learning disability and a terrible secret. The little guy is Kevin, whose tiny body is wracked with a syndrome that is slowly killing him. Together, they are Freak the Mighty, and they can overcome bullies and brutes. This story does not end up happily, either, but the reader is left with a sense of hope for the future. The book was made into a movie titled

The Mighty

, and stars Kieran Culkin and an all-star cast. When I taught middle school Language Arts, this was one of my favorite books to share. The movie to book comparison always led to good discussions on how characters were presented and what and why certain plots lines, scenes and themes were left out of the movie version.

The most hopeful middle grade big guy/ little guy book I found was Leslie Connor’s multiple-award winning The Truth As Told by Mason Buttle (Katherine Tegen Books; Reprint edition, January 7, 2020, ISBN-10: 0062491458.) Mason is a big, sweaty kid whose learning disabilities make reading and writing impossible. His down and out family has suffered several deaths and the sell-off of their orchard land that had been their livelihood for generations. Then, the body of Mason’s best friend, Benny Kilmartin, was found in what remained of the family orchard and he is shunned by the town and bullied by neighboring boys. Mason’s luck begins to change when little guy Calvin Chumsky befriends him. Together, the two manage to enjoy their circumstances while the investigation drags on, and Mason tries to convince Lieutenant Baird that he is not responsible for Benny’s death. The truth does come out, in ways that no one has anticipated. I think it is important for parents and teachers to talk with children about the big guy/little guy trope. The line between trope and stereotype is slim, indeed. Not every big guy is a gentle giant with limited mental ability. Some big guys are big on brains, too. Others are not gentle at all. Nor is every little guy a genius trapped in a weak frame. But regardless of its limitations, the trope remains an important one in literature and worthy of study. I think comparing books to cartoon depictions and movies is a good place to start. Perhaps middle schoolers would be better prepared for Steinbeck if they began with Philbrick and Connor.

The most hopeful middle grade big guy/ little guy book I found was Leslie Connor’s multiple-award winning The Truth As Told by Mason Buttle (Katherine Tegen Books; Reprint edition, January 7, 2020, ISBN-10: 0062491458.) Mason is a big, sweaty kid whose learning disabilities make reading and writing impossible. His down and out family has suffered several deaths and the sell-off of their orchard land that had been their livelihood for generations. Then, the body of Mason’s best friend, Benny Kilmartin, was found in what remained of the family orchard and he is shunned by the town and bullied by neighboring boys. Mason’s luck begins to change when little guy Calvin Chumsky befriends him. Together, the two manage to enjoy their circumstances while the investigation drags on, and Mason tries to convince Lieutenant Baird that he is not responsible for Benny’s death. The truth does come out, in ways that no one has anticipated. I think it is important for parents and teachers to talk with children about the big guy/little guy trope. The line between trope and stereotype is slim, indeed. Not every big guy is a gentle giant with limited mental ability. Some big guys are big on brains, too. Others are not gentle at all. Nor is every little guy a genius trapped in a weak frame. But regardless of its limitations, the trope remains an important one in literature and worthy of study. I think comparing books to cartoon depictions and movies is a good place to start. Perhaps middle schoolers would be better prepared for Steinbeck if they began with Philbrick and Connor.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a retired High School and Middle School Language Arts and History teacher. She is the author of historical novels for both middle grade and adult readers.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a retired High School and Middle School Language Arts and History teacher. She is the author of historical novels for both middle grade and adult readers.

The book links in this article are to Bookshop.org, an online bookseller that gives 75% of its profits to independent bookstores, authors, and reviewers. As an affiliate, Jennifer Bohnhoff receives a commission when people buy books by clicking through links on her blog or browsing her shop at bookshop.org/shop/jenniferbohnhoff. A matching commission goes to independent booksellers. However, Ms. Bohnhoff is just as happy when people borrow books from their local library or shop at their local independent booksellers.

The big guy/little guy partnership has been used repeatedly in cartoons. When my sons were little, the TV cartoon that used this trope most obviously was Pinky and the Brain. The cartoon focused on two genetically enhanced laboratory mice who resided in a cage inside the Acme Labs research facility. Brain, the littler of the two mice, was highly intelligent, self-centered and scheming. Pinky was Brain’s sweet-natured but feeble-minded henchman. In every episode, Brain devised a new plan to take over the world, but his plans always failed, with hilarious results.

Not all works that use the big guy/ little guy trope are funny, however. Probably the most famous and most literary of the trope’s treatments has been in

Of Mice and Men,

John Steinbeck’s 1937 novella. In it, George Milton is the little, smart guy who tries to protect Lennie Small, a slow thinking giant of a man who does not understand his own strength. The two displaced ranch workers move from job to job in Depression-era California, until fate catches up to them and Lennie can no longer protect his friend. The story is a tragedy and appears on the American Library Association's list of the Most Challenged Books of the 21st Century because many consider the material both offensive and racist, but it is also a beautiful depiction of the difficulties some people seem to never be able to shrug off, and the importance of watching after each other. It is a book that is, by turns, noble and base, vulgar and tender, and is frequently taught in high school courses. I consider it a little too mature for middle school readers, but hope that middle schoolers will have the chance to encounter it when they are older.

Not all works that use the big guy/ little guy trope are funny, however. Probably the most famous and most literary of the trope’s treatments has been in

Of Mice and Men,

John Steinbeck’s 1937 novella. In it, George Milton is the little, smart guy who tries to protect Lennie Small, a slow thinking giant of a man who does not understand his own strength. The two displaced ranch workers move from job to job in Depression-era California, until fate catches up to them and Lennie can no longer protect his friend. The story is a tragedy and appears on the American Library Association's list of the Most Challenged Books of the 21st Century because many consider the material both offensive and racist, but it is also a beautiful depiction of the difficulties some people seem to never be able to shrug off, and the importance of watching after each other. It is a book that is, by turns, noble and base, vulgar and tender, and is frequently taught in high school courses. I consider it a little too mature for middle school readers, but hope that middle schoolers will have the chance to encounter it when they are older.

A book that features the big guy/ little guy trope, but is appropriate for middle school readers is Rodman Philbrick’s Freak the Mighty (Scholastic Paperbacks; Reprint edition, June 1, 2001, ISBN-13: 978-0439286060) In this novel, the big guy is Max, a teenage giant with a learning disability and a terrible secret. The little guy is Kevin, whose tiny body is wracked with a syndrome that is slowly killing him. Together, they are Freak the Mighty, and they can overcome bullies and brutes. This story does not end up happily, either, but the reader is left with a sense of hope for the future. The book was made into a movie titled

The Mighty

, and stars Kieran Culkin and an all-star cast. When I taught middle school Language Arts, this was one of my favorite books to share. The movie to book comparison always led to good discussions on how characters were presented and what and why certain plots lines, scenes and themes were left out of the movie version.

A book that features the big guy/ little guy trope, but is appropriate for middle school readers is Rodman Philbrick’s Freak the Mighty (Scholastic Paperbacks; Reprint edition, June 1, 2001, ISBN-13: 978-0439286060) In this novel, the big guy is Max, a teenage giant with a learning disability and a terrible secret. The little guy is Kevin, whose tiny body is wracked with a syndrome that is slowly killing him. Together, they are Freak the Mighty, and they can overcome bullies and brutes. This story does not end up happily, either, but the reader is left with a sense of hope for the future. The book was made into a movie titled

The Mighty

, and stars Kieran Culkin and an all-star cast. When I taught middle school Language Arts, this was one of my favorite books to share. The movie to book comparison always led to good discussions on how characters were presented and what and why certain plots lines, scenes and themes were left out of the movie version.

The most hopeful middle grade big guy/ little guy book I found was Leslie Connor’s multiple-award winning The Truth As Told by Mason Buttle (Katherine Tegen Books; Reprint edition, January 7, 2020, ISBN-10: 0062491458.) Mason is a big, sweaty kid whose learning disabilities make reading and writing impossible. His down and out family has suffered several deaths and the sell-off of their orchard land that had been their livelihood for generations. Then, the body of Mason’s best friend, Benny Kilmartin, was found in what remained of the family orchard and he is shunned by the town and bullied by neighboring boys. Mason’s luck begins to change when little guy Calvin Chumsky befriends him. Together, the two manage to enjoy their circumstances while the investigation drags on, and Mason tries to convince Lieutenant Baird that he is not responsible for Benny’s death. The truth does come out, in ways that no one has anticipated. I think it is important for parents and teachers to talk with children about the big guy/little guy trope. The line between trope and stereotype is slim, indeed. Not every big guy is a gentle giant with limited mental ability. Some big guys are big on brains, too. Others are not gentle at all. Nor is every little guy a genius trapped in a weak frame. But regardless of its limitations, the trope remains an important one in literature and worthy of study. I think comparing books to cartoon depictions and movies is a good place to start. Perhaps middle schoolers would be better prepared for Steinbeck if they began with Philbrick and Connor.

The most hopeful middle grade big guy/ little guy book I found was Leslie Connor’s multiple-award winning The Truth As Told by Mason Buttle (Katherine Tegen Books; Reprint edition, January 7, 2020, ISBN-10: 0062491458.) Mason is a big, sweaty kid whose learning disabilities make reading and writing impossible. His down and out family has suffered several deaths and the sell-off of their orchard land that had been their livelihood for generations. Then, the body of Mason’s best friend, Benny Kilmartin, was found in what remained of the family orchard and he is shunned by the town and bullied by neighboring boys. Mason’s luck begins to change when little guy Calvin Chumsky befriends him. Together, the two manage to enjoy their circumstances while the investigation drags on, and Mason tries to convince Lieutenant Baird that he is not responsible for Benny’s death. The truth does come out, in ways that no one has anticipated. I think it is important for parents and teachers to talk with children about the big guy/little guy trope. The line between trope and stereotype is slim, indeed. Not every big guy is a gentle giant with limited mental ability. Some big guys are big on brains, too. Others are not gentle at all. Nor is every little guy a genius trapped in a weak frame. But regardless of its limitations, the trope remains an important one in literature and worthy of study. I think comparing books to cartoon depictions and movies is a good place to start. Perhaps middle schoolers would be better prepared for Steinbeck if they began with Philbrick and Connor.  Jennifer Bohnhoff is a retired High School and Middle School Language Arts and History teacher. She is the author of historical novels for both middle grade and adult readers.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a retired High School and Middle School Language Arts and History teacher. She is the author of historical novels for both middle grade and adult readers. The book links in this article are to Bookshop.org, an online bookseller that gives 75% of its profits to independent bookstores, authors, and reviewers. As an affiliate, Jennifer Bohnhoff receives a commission when people buy books by clicking through links on her blog or browsing her shop at bookshop.org/shop/jenniferbohnhoff. A matching commission goes to independent booksellers. However, Ms. Bohnhoff is just as happy when people borrow books from their local library or shop at their local independent booksellers.

Published on October 06, 2022 12:51

October 3, 2022

Historical Novels that bring New Mexico History to Life

I am always deeply saddened when I hear people tell me that New Mexico History is boring. I used to teach the subject at the middle school level, and I confess that the textbook was, indeed boring. Fitting thousands of years of history into a book involves leaving out all the details that makes the story exciting I strived to tell those stories in my classroom, and the result was that a lot of kids found that history wasn’t just a list of names, dates, treaties and battles. History was the story of people who were trying, just like my students, to do the best they could under whatever circumstances they were given. These four novels to a good job of giving the history of New Mexico a human face.

Dennis Herrick’s Winter of the Metal People: The Untold Story of America's First Indian War (Sunbury Press, 2013, ISBN-10 1620062372) tells the story of Spanish conquistador Francisco Coronado's 1540-1542.expedition into New Mexico and his occupation of a pueblo near what is now Bernalillo, on the banks of the Rio Grande. The site, which may be at what is now called Coronado Monument, Told from both a Spanish perspective derived from the chronicles the explorers left behind and from the (largely conjectured) perspective of the Puebloans, this well researched novel depicts the Tiguex War, the first battle between Europeans and Indians on what was to become American soil.

Dennis Herrick’s Winter of the Metal People: The Untold Story of America's First Indian War (Sunbury Press, 2013, ISBN-10 1620062372) tells the story of Spanish conquistador Francisco Coronado's 1540-1542.expedition into New Mexico and his occupation of a pueblo near what is now Bernalillo, on the banks of the Rio Grande. The site, which may be at what is now called Coronado Monument, Told from both a Spanish perspective derived from the chronicles the explorers left behind and from the (largely conjectured) perspective of the Puebloans, this well researched novel depicts the Tiguex War, the first battle between Europeans and Indians on what was to become American soil.

Loretta Miles Tollefson’s There Will Be Consequences: A Biographical Novel of Old New Mexico (Palo Flechado Press, 2022, ISBN 1952026059) tells the story of a very tumultuous time in New Mexico history. New Mexico, the distant and neglected area on the wild edge of the Spanish New World, had long been left to its own devices. The Spanish, busy with European wars and other colonies, had provided little, and expected little in return. New Mexicans had expected the same kind of negligence from the Mexican government when it revolted against Spain and established its own government. However, by 1837, Mexico had decided to exert more control over New Mexico, appointing governors from beyond its territory and demanding taxes that had long been waived. The northern half of the territory responded with a rebellion that left the Governor and key members of his administration dead, and a local man with indigenous ancestry and a set of local alcaldes set up in their place. In this well researched novelization of the events, Tollefson tells the story of this rebellion through the eyes of twelve of its participants and witnesses. Anyone who’s read anything of the period will recognize names such as Albino Pérez, José Angel Gonzales, Gertrudes "Doña Tules" Barceló, Father Antonio José Martinez, and Manuel Armijo. But Tollefson isn’t just reciting names and events. Her narrative makes the people in it come alive.

Loretta Miles Tollefson’s There Will Be Consequences: A Biographical Novel of Old New Mexico (Palo Flechado Press, 2022, ISBN 1952026059) tells the story of a very tumultuous time in New Mexico history. New Mexico, the distant and neglected area on the wild edge of the Spanish New World, had long been left to its own devices. The Spanish, busy with European wars and other colonies, had provided little, and expected little in return. New Mexicans had expected the same kind of negligence from the Mexican government when it revolted against Spain and established its own government. However, by 1837, Mexico had decided to exert more control over New Mexico, appointing governors from beyond its territory and demanding taxes that had long been waived. The northern half of the territory responded with a rebellion that left the Governor and key members of his administration dead, and a local man with indigenous ancestry and a set of local alcaldes set up in their place. In this well researched novelization of the events, Tollefson tells the story of this rebellion through the eyes of twelve of its participants and witnesses. Anyone who’s read anything of the period will recognize names such as Albino Pérez, José Angel Gonzales, Gertrudes "Doña Tules" Barceló, Father Antonio José Martinez, and Manuel Armijo. But Tollefson isn’t just reciting names and events. Her narrative makes the people in it come alive.

Mary Armstrong’s The Mesilla: Two Valleys Saga: Book One (Enchanted Writing Company, 2021, ASIN B093CPZ71B) tells its story through the eyes of fourteen years old, Jesus ‘Chuy’ Perez Contreras Verazzi Messi, who is apprenticed to his by his uncle, the noted Las Cruces attorney and politician, Colonel Albert Jennings Fountain. Bronco Sue, Oliver Lee, and Frenchy Rochas are among the historical figures that appear in this novel that takes place in the territorial period, when the area was struggling with range wars and trying to appear legitimate and worthy of statehood. It is filled with courtroom drama and the kind of background stories that spice up history and make the characters come alive. The first in a trilogy, this novel sets up the events that may have led to the unsolved murder of Fountain ten years later.

Mary Armstrong’s The Mesilla: Two Valleys Saga: Book One (Enchanted Writing Company, 2021, ASIN B093CPZ71B) tells its story through the eyes of fourteen years old, Jesus ‘Chuy’ Perez Contreras Verazzi Messi, who is apprenticed to his by his uncle, the noted Las Cruces attorney and politician, Colonel Albert Jennings Fountain. Bronco Sue, Oliver Lee, and Frenchy Rochas are among the historical figures that appear in this novel that takes place in the territorial period, when the area was struggling with range wars and trying to appear legitimate and worthy of statehood. It is filled with courtroom drama and the kind of background stories that spice up history and make the characters come alive. The first in a trilogy, this novel sets up the events that may have led to the unsolved murder of Fountain ten years later.

Finally, I am pleased to share that my own novel

A Blaze of Poppies

(Thin Air Publishing, 2021, ASIN B09HG16WBX) recently won the 2022 New Mexico Book Award in the category of New Mexico Historical Fiction. This novel tells the story of a young, female rancher in Southern New Mexico who is determined to keep the Sunrise Ranch in the family. Threatened first by Pancho Villa’s raid on nearby Columbus, New Mexico and by her own mother’s refusal to support her, Agnes Day becomes a nurse and serves behind the trenches in World War I France that are occupied by members of the New Mexico National Guard.

Finally, I am pleased to share that my own novel

A Blaze of Poppies

(Thin Air Publishing, 2021, ASIN B09HG16WBX) recently won the 2022 New Mexico Book Award in the category of New Mexico Historical Fiction. This novel tells the story of a young, female rancher in Southern New Mexico who is determined to keep the Sunrise Ranch in the family. Threatened first by Pancho Villa’s raid on nearby Columbus, New Mexico and by her own mother’s refusal to support her, Agnes Day becomes a nurse and serves behind the trenches in World War I France that are occupied by members of the New Mexico National Guard.

New Mexico has a vibrant history made all the more interesting because of the mix of people who have inhabited a difficult to conquer landscape. Try one of these books and see for yourself. The book links in this article are to Bookshop.org, an online bookseller that gives 75% of its profits to independent bookstores, authors, and reviewers. As an affiliate, Jennifer Bohnhoff receives a commission when people buy books by clicking through links on her blog or browsing her shop at bookshop.org/shop/jenniferbohnhoff. A matching commission goes to independent booksellers. However, Ms. Bohnhoff is pleased if you borrow books from your local library or shop at your own local independent bookseller.

Dennis Herrick’s Winter of the Metal People: The Untold Story of America's First Indian War (Sunbury Press, 2013, ISBN-10 1620062372) tells the story of Spanish conquistador Francisco Coronado's 1540-1542.expedition into New Mexico and his occupation of a pueblo near what is now Bernalillo, on the banks of the Rio Grande. The site, which may be at what is now called Coronado Monument, Told from both a Spanish perspective derived from the chronicles the explorers left behind and from the (largely conjectured) perspective of the Puebloans, this well researched novel depicts the Tiguex War, the first battle between Europeans and Indians on what was to become American soil.

Dennis Herrick’s Winter of the Metal People: The Untold Story of America's First Indian War (Sunbury Press, 2013, ISBN-10 1620062372) tells the story of Spanish conquistador Francisco Coronado's 1540-1542.expedition into New Mexico and his occupation of a pueblo near what is now Bernalillo, on the banks of the Rio Grande. The site, which may be at what is now called Coronado Monument, Told from both a Spanish perspective derived from the chronicles the explorers left behind and from the (largely conjectured) perspective of the Puebloans, this well researched novel depicts the Tiguex War, the first battle between Europeans and Indians on what was to become American soil.  Loretta Miles Tollefson’s There Will Be Consequences: A Biographical Novel of Old New Mexico (Palo Flechado Press, 2022, ISBN 1952026059) tells the story of a very tumultuous time in New Mexico history. New Mexico, the distant and neglected area on the wild edge of the Spanish New World, had long been left to its own devices. The Spanish, busy with European wars and other colonies, had provided little, and expected little in return. New Mexicans had expected the same kind of negligence from the Mexican government when it revolted against Spain and established its own government. However, by 1837, Mexico had decided to exert more control over New Mexico, appointing governors from beyond its territory and demanding taxes that had long been waived. The northern half of the territory responded with a rebellion that left the Governor and key members of his administration dead, and a local man with indigenous ancestry and a set of local alcaldes set up in their place. In this well researched novelization of the events, Tollefson tells the story of this rebellion through the eyes of twelve of its participants and witnesses. Anyone who’s read anything of the period will recognize names such as Albino Pérez, José Angel Gonzales, Gertrudes "Doña Tules" Barceló, Father Antonio José Martinez, and Manuel Armijo. But Tollefson isn’t just reciting names and events. Her narrative makes the people in it come alive.

Loretta Miles Tollefson’s There Will Be Consequences: A Biographical Novel of Old New Mexico (Palo Flechado Press, 2022, ISBN 1952026059) tells the story of a very tumultuous time in New Mexico history. New Mexico, the distant and neglected area on the wild edge of the Spanish New World, had long been left to its own devices. The Spanish, busy with European wars and other colonies, had provided little, and expected little in return. New Mexicans had expected the same kind of negligence from the Mexican government when it revolted against Spain and established its own government. However, by 1837, Mexico had decided to exert more control over New Mexico, appointing governors from beyond its territory and demanding taxes that had long been waived. The northern half of the territory responded with a rebellion that left the Governor and key members of his administration dead, and a local man with indigenous ancestry and a set of local alcaldes set up in their place. In this well researched novelization of the events, Tollefson tells the story of this rebellion through the eyes of twelve of its participants and witnesses. Anyone who’s read anything of the period will recognize names such as Albino Pérez, José Angel Gonzales, Gertrudes "Doña Tules" Barceló, Father Antonio José Martinez, and Manuel Armijo. But Tollefson isn’t just reciting names and events. Her narrative makes the people in it come alive.

Mary Armstrong’s The Mesilla: Two Valleys Saga: Book One (Enchanted Writing Company, 2021, ASIN B093CPZ71B) tells its story through the eyes of fourteen years old, Jesus ‘Chuy’ Perez Contreras Verazzi Messi, who is apprenticed to his by his uncle, the noted Las Cruces attorney and politician, Colonel Albert Jennings Fountain. Bronco Sue, Oliver Lee, and Frenchy Rochas are among the historical figures that appear in this novel that takes place in the territorial period, when the area was struggling with range wars and trying to appear legitimate and worthy of statehood. It is filled with courtroom drama and the kind of background stories that spice up history and make the characters come alive. The first in a trilogy, this novel sets up the events that may have led to the unsolved murder of Fountain ten years later.

Mary Armstrong’s The Mesilla: Two Valleys Saga: Book One (Enchanted Writing Company, 2021, ASIN B093CPZ71B) tells its story through the eyes of fourteen years old, Jesus ‘Chuy’ Perez Contreras Verazzi Messi, who is apprenticed to his by his uncle, the noted Las Cruces attorney and politician, Colonel Albert Jennings Fountain. Bronco Sue, Oliver Lee, and Frenchy Rochas are among the historical figures that appear in this novel that takes place in the territorial period, when the area was struggling with range wars and trying to appear legitimate and worthy of statehood. It is filled with courtroom drama and the kind of background stories that spice up history and make the characters come alive. The first in a trilogy, this novel sets up the events that may have led to the unsolved murder of Fountain ten years later.

Finally, I am pleased to share that my own novel

A Blaze of Poppies

(Thin Air Publishing, 2021, ASIN B09HG16WBX) recently won the 2022 New Mexico Book Award in the category of New Mexico Historical Fiction. This novel tells the story of a young, female rancher in Southern New Mexico who is determined to keep the Sunrise Ranch in the family. Threatened first by Pancho Villa’s raid on nearby Columbus, New Mexico and by her own mother’s refusal to support her, Agnes Day becomes a nurse and serves behind the trenches in World War I France that are occupied by members of the New Mexico National Guard.

Finally, I am pleased to share that my own novel

A Blaze of Poppies

(Thin Air Publishing, 2021, ASIN B09HG16WBX) recently won the 2022 New Mexico Book Award in the category of New Mexico Historical Fiction. This novel tells the story of a young, female rancher in Southern New Mexico who is determined to keep the Sunrise Ranch in the family. Threatened first by Pancho Villa’s raid on nearby Columbus, New Mexico and by her own mother’s refusal to support her, Agnes Day becomes a nurse and serves behind the trenches in World War I France that are occupied by members of the New Mexico National Guard.

New Mexico has a vibrant history made all the more interesting because of the mix of people who have inhabited a difficult to conquer landscape. Try one of these books and see for yourself. The book links in this article are to Bookshop.org, an online bookseller that gives 75% of its profits to independent bookstores, authors, and reviewers. As an affiliate, Jennifer Bohnhoff receives a commission when people buy books by clicking through links on her blog or browsing her shop at bookshop.org/shop/jenniferbohnhoff. A matching commission goes to independent booksellers. However, Ms. Bohnhoff is pleased if you borrow books from your local library or shop at your own local independent bookseller.

Published on October 03, 2022 15:03

September 23, 2022

Stories about Living During the Vietnam War Era for Middle Grade Readers

The author and her Uncle, probably in 1965. I don't believe he served in Vietnam, but I don't really remember. It’s stunning to me that the Vietnam War is ancient history for today’s middle schoolers. To old folks like me, who grew up while our soldiers were wading through rice paddies and jungles, it seems unbelievable that today’s kids wouldn’t know anything about the Vietnam War, or what it was like here on the home front during that tumultuous period. But then I got to analyzing how much time has passed, using real numbers (something I don’t often do!) and I realized that it’s perfectly understandable that today’s middle grade readers know so little.

The author and her Uncle, probably in 1965. I don't believe he served in Vietnam, but I don't really remember. It’s stunning to me that the Vietnam War is ancient history for today’s middle schoolers. To old folks like me, who grew up while our soldiers were wading through rice paddies and jungles, it seems unbelievable that today’s kids wouldn’t know anything about the Vietnam War, or what it was like here on the home front during that tumultuous period. But then I got to analyzing how much time has passed, using real numbers (something I don’t often do!) and I realized that it’s perfectly understandable that today’s middle grade readers know so little.

I am just slightly too young to have much personal experience with the Vietnam War. The war ended when Saigon fell on the 30th of April 1975. I was in high school by then, but the war was old news that few people cared about. For many Americans, the war was over in December of 1972, when the last draft call was held, or in March of 1973, when the last of our ground troops left Vietnam. I was still in Junior High then. I had some friends whose older brothers were in the draft, and a few who went over and served, but most of the people I knew where involved in the war were a generation removed from me, and were fathers of friends, old enough to have command or desk jobs. My husband registered for the draft, but the draft had ceased before he could be called up.

My grandfather served during World War I, which ended 41 years before I was born. I remember thinking that he was a very old man, and that the war he had served in much have been long, long ago. I assume that an average twelve-year-old, who would have been born thirty-five years after the end of the Vietnam feels the same. If they know anyone involved in Vietnam, it would be a grandparent or even a great grandparent. Ancient history.

My grandfather served during World War I, which ended 41 years before I was born. I remember thinking that he was a very old man, and that the war he had served in much have been long, long ago. I assume that an average twelve-year-old, who would have been born thirty-five years after the end of the Vietnam feels the same. If they know anyone involved in Vietnam, it would be a grandparent or even a great grandparent. Ancient history.

Maybe one of the reasons I loved Gary D. Schmidt’s The Wednesday Wars, a middle grade historical novel that won a Newberry Honor in 2008 is that Schmidt is two years older than I am, so his memories of the period would be much like my own. Reading this novel is much like a trip into my own reminiscences of the period. I remember arguments similar to the one between the protagonist’s conservative father and would-be flower child sister. I remember VW bugs with flower decals, and the horrific shock of the deaths of Martin Luther King and Robert F. Kennedy. The world felt like it was unraveling, and Walter Cronkite was there every evening to explain it all to us.

Maybe one of the reasons I loved Gary D. Schmidt’s The Wednesday Wars, a middle grade historical novel that won a Newberry Honor in 2008 is that Schmidt is two years older than I am, so his memories of the period would be much like my own. Reading this novel is much like a trip into my own reminiscences of the period. I remember arguments similar to the one between the protagonist’s conservative father and would-be flower child sister. I remember VW bugs with flower decals, and the horrific shock of the deaths of Martin Luther King and Robert F. Kennedy. The world felt like it was unraveling, and Walter Cronkite was there every evening to explain it all to us.But The Wednesday Wars isn’t just a book about a particular point in time; it’s also a book about a boy at a particular point in his own development into manhood. Holling Hoodhood may be a seventh grader during the 1967–1968 school year, but many of the problems he faces are similar to those that seventh grade boys still encounter.

Holling’s father is a self-centered architect who is so busy becoming the Chamber of Commerce Businessman of the year that he can’t attend his son’s performance in The Tempest. The father sees every relationship as a potential business association and demands that he, his family, and their house all be above reproach and perfect at all times. It’s a tough standard to attain, particularly for a middle school boy who, as most boys his age, feels gawky and unsure of himself.

Holling finds an unlikely ally in Mrs. Baker, his no-nonsense teacher. On Wednesday afternoons, half of Holling's classmates leave school early for catechism class and the other half attends Hebrew school leaving Holling, the only Presbyterian, alone in the classroom. Holling thinks Mrs. Baker hates him because of this, but after an unexpected disaster involving cream puffs and chalk board erasers, Mrs. Baker introduces Holling to Shakespeare. The Bard becomes the lens through which Holling processes the world around him, including his relationship with his father, with Meryl Lee Kowalski, the daughter of a rival architect, his sister Heather, and even Mickey Mantle. I couldn’t help but love the awkward, fumbling Holling.

If you’d like to read a story set in the Vietnam War era that has a female protagonist, consider Shooting the Moon, by Frances O'Roark Dowell. Twelve-year-old Jamie Dexter is a military brat whose father is a colonel stationed in Texas. Jamie is proud and excited when her older brother enlists in the Army and is sent to Vietnam. She can't wait to get letters from the front lines describing the excitement of real-life combat, the sound of helicopters, the smell of gunpowder, the exhilaration of being right in the thick of it. But her brother doesn’t send letters. Instead, he sends roll after roll of undeveloped film that shows photos of the moon and gritty pictures that depict a side to war that she has never considered. While Jamie works in the base’s rec office, she begins to question everything she’s ever believed, and when her brother goes MIA and her father can do nothing, Jamie’s innocence is lost and she must grow up quickly.

If you’d like to read a story set in the Vietnam War era that has a female protagonist, consider Shooting the Moon, by Frances O'Roark Dowell. Twelve-year-old Jamie Dexter is a military brat whose father is a colonel stationed in Texas. Jamie is proud and excited when her older brother enlists in the Army and is sent to Vietnam. She can't wait to get letters from the front lines describing the excitement of real-life combat, the sound of helicopters, the smell of gunpowder, the exhilaration of being right in the thick of it. But her brother doesn’t send letters. Instead, he sends roll after roll of undeveloped film that shows photos of the moon and gritty pictures that depict a side to war that she has never considered. While Jamie works in the base’s rec office, she begins to question everything she’s ever believed, and when her brother goes MIA and her father can do nothing, Jamie’s innocence is lost and she must grow up quickly. Other books about the Vietnam War

Summer's End, by Audrey Couloumbis, is another book featuring a girl growing up during the Vietnam War. When her older brother is drafted but burns his draft card, thirteen-year-old Grace finds herself in the middle of a war raging within her own family.

Ellen Emerson White’s contribution to the Dear America series is Where Have All the Flowers Gone?: The Diary of Molly MacKenzie Flaherty, Boston, Massachusetts, 1968. The book is set up to be the diary entries of a brother who is a Marine stationed in Vietnam, and his sister, a peace activist back in the states.

Georgie's Moon, by Chris Woodworth tells the story of Georgie Collins, whose father gave her standing orders never to let anyone mess with her before he left for Vietnam. Despite "peacenik" classmates who think the war is wrong and being forced to visit old people in a nursing home, Georgie tries to survive seventh grade in Glendale, Indiana as she waits for her father’s return.

Elizabeth Partridge’s Dogtag Summer tells the story of twelve-year-old Tracy, who was once named Tuyet. Half Vietnamese and half American GI, Tracy has never felt she fit in with her adoptive California family. Finding a soldier's dog tag hidden among her father's things begins a set of events that promise to change everything.

Times change. Events happen, impress themselves on us, and then we move on. The Vietnam War no longer lives large in the American psyche. It has been replaced by 9/11, COVID, and a dozen other events. But being in the 7th grade and finding oneself on the teetering brink of adulthood remains an important time for individuals. I think it's important for today's middle grade readers to know that their parents, and their grandparents, and all the generations who came before that also struggled with what it meant to become oneself. Jennifer Bohnhoff is a former high school and middle school English and history teacher who is now old enough to get to stay home and write. She lives in the mountains east of Albuquerque, New Mexico with her very patient and equally old husband, and a big, rambunctious black dog named Panzer. You can read more about her and her books on her website.

Published on September 23, 2022 12:20

August 30, 2022

Giving Back New Mexico

New Mexico has been peopled for tens of thousands of years. The radiocarbon dating of footprints found at White Sands has pushed back human occupation to somewhere between 23,000 and 21,000 years ago. As far as we know, for much of that time, the different people occupied different areas without any formal boundaries.Spheres of influence overlapped. People shared the same hunting grounds and wintering areas, sometimes peacefully and sometimes not.

New Mexico has been peopled for tens of thousands of years. The radiocarbon dating of footprints found at White Sands has pushed back human occupation to somewhere between 23,000 and 21,000 years ago. As far as we know, for much of that time, the different people occupied different areas without any formal boundaries.Spheres of influence overlapped. People shared the same hunting grounds and wintering areas, sometimes peacefully and sometimes not.

That all changed with the coming of the Spanish in the sixteenth century. The first peoples with a written system to document their intentions, they declared the land the property of the Spanish King and divided it into grants. From early on, the Spanish recognized three different types of land grants. Private grants were awarded to soldiers, nobility, and important people. Community grants were given to groups of people, particularly genizaro. The settled Indian populations, which means the Puebloans, received grants that protected their pueblos and fields from Spanish incursion to some degree. Those tribes that did not live a settled lifestyle did not receive land grants. Following the Mexican-American War, the United States took control of the territory. The treaty ending the war recognized the Pueblo land grants. In 1863, President Lincoln presented 19 Pueblo Governors with canes to show that the Federal government recognized their authority. Today there are still 19 Pueblo tribes in New Mexico. Each pueblo is a sovereign nation.

That all changed with the coming of the Spanish in the sixteenth century. The first peoples with a written system to document their intentions, they declared the land the property of the Spanish King and divided it into grants. From early on, the Spanish recognized three different types of land grants. Private grants were awarded to soldiers, nobility, and important people. Community grants were given to groups of people, particularly genizaro. The settled Indian populations, which means the Puebloans, received grants that protected their pueblos and fields from Spanish incursion to some degree. Those tribes that did not live a settled lifestyle did not receive land grants. Following the Mexican-American War, the United States took control of the territory. The treaty ending the war recognized the Pueblo land grants. In 1863, President Lincoln presented 19 Pueblo Governors with canes to show that the Federal government recognized their authority. Today there are still 19 Pueblo tribes in New Mexico. Each pueblo is a sovereign nation.  1923 photograph of Pueblo leaders in Washington, D.C. to protest the Bursum Bill, which threatened the Pueblos with land loss. They are each holding their Lincoln cane. Not all Indigenous peoples in New Mexico lived settled lives. The nomadic tribes: the Apache, Navajo and Comanche tended to live within a range of land, but they did not stay in one place. The Navajo had fields and orchards, but they did not tend them year round. These groups were not given land grants by either the Spanish or the Mexican governments when they controlled New Mexico.

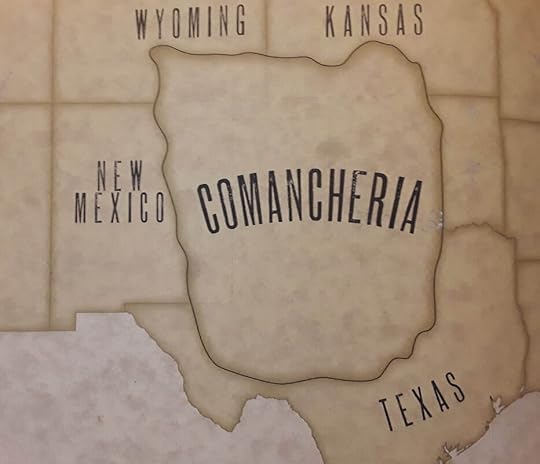

1923 photograph of Pueblo leaders in Washington, D.C. to protest the Bursum Bill, which threatened the Pueblos with land loss. They are each holding their Lincoln cane. Not all Indigenous peoples in New Mexico lived settled lives. The nomadic tribes: the Apache, Navajo and Comanche tended to live within a range of land, but they did not stay in one place. The Navajo had fields and orchards, but they did not tend them year round. These groups were not given land grants by either the Spanish or the Mexican governments when they controlled New Mexico.  Comancheria, as envisioned by Michael Trinklein in Lost States: True Stories of Texlahoma, Transylvania, and other States that Never Made it. In 1837, Sam Houston, the President of the Republic of Texas, proposed that the Comanches be given their own land. Their summer range encompassed much of western Texas, large portions of what is now Oklahoma and New Mexico, and the edges of Colorado and Kansas. The Comanches were fierce fighters. Giving them their own territory would, the Texans hoped, stop them from killing settlers and attacking wagon trains. The Texas congress did not ratify Houston's proposal, and the Comanche's were eventually given a reservation in Oklahoma. Apache tribes have little reservations scattered over several western states, and the Navajo reservation straddles the states of Utah, Arizona and New Mexico.

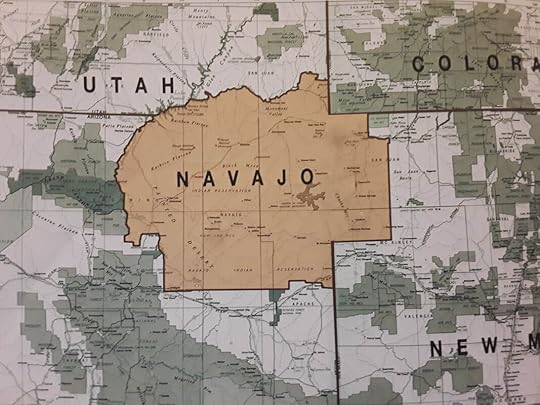

Comancheria, as envisioned by Michael Trinklein in Lost States: True Stories of Texlahoma, Transylvania, and other States that Never Made it. In 1837, Sam Houston, the President of the Republic of Texas, proposed that the Comanches be given their own land. Their summer range encompassed much of western Texas, large portions of what is now Oklahoma and New Mexico, and the edges of Colorado and Kansas. The Comanches were fierce fighters. Giving them their own territory would, the Texans hoped, stop them from killing settlers and attacking wagon trains. The Texas congress did not ratify Houston's proposal, and the Comanche's were eventually given a reservation in Oklahoma. Apache tribes have little reservations scattered over several western states, and the Navajo reservation straddles the states of Utah, Arizona and New Mexico.  In the 1970s, Navajo tribal chairman Peter McDonald suggested that the Navajo homeland become the fifty-first state, giving its occupants more autonomy and control. The biggest issue at the time was the refusal of Utah to allow the Ft. Hall Navajos to build a casino on their land. While his proposal received national attention in 1974, New Mexico, Arizona and Utah all refused to support it. If the population within the reservation grows, this proposal might be renewed.

In the 1970s, Navajo tribal chairman Peter McDonald suggested that the Navajo homeland become the fifty-first state, giving its occupants more autonomy and control. The biggest issue at the time was the refusal of Utah to allow the Ft. Hall Navajos to build a casino on their land. While his proposal received national attention in 1974, New Mexico, Arizona and Utah all refused to support it. If the population within the reservation grows, this proposal might be renewed.

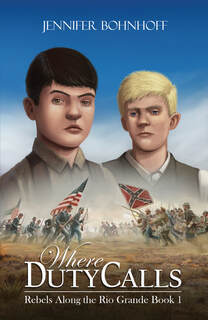

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a retired New Mexico History teacher who now writes historical fiction. She has written about the state during the Civil War in Where Duty Calls, during World War I in A Blaze of Poppies, and is currently at work on a novel set 12,000 years ago during the Folsom period.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a retired New Mexico History teacher who now writes historical fiction. She has written about the state during the Civil War in Where Duty Calls, during World War I in A Blaze of Poppies, and is currently at work on a novel set 12,000 years ago during the Folsom period.

Published on August 30, 2022 23:00

August 14, 2022

The Bard of the East Mountains

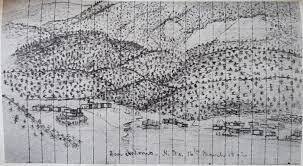

A sketch of San Antonio, New Mexico, by A. Petticolas, Confederate soldier A while back, a neighbor was over and we were talking about the history here on the east side of the Sandia Mountains. He was raised here. I spent my teens in Albuquerque, the city that lies just west of the Sandias. I hiked in the mountains plenty, and I had friends that lived over here, especially after I got to high school. Manzano High School was, and still is the high school that kids from the east mountains attended. I’ve always been interested in the geology of the mountains. Its most ancient of records are the rocks, which tell us that what is now the top of a mountain used to be at the bottom of a sea. But I didn’t become interested in the human history of the east mountains, its small towns, and the people who inhabited them until I moved here in 2017.

A sketch of San Antonio, New Mexico, by A. Petticolas, Confederate soldier A while back, a neighbor was over and we were talking about the history here on the east side of the Sandia Mountains. He was raised here. I spent my teens in Albuquerque, the city that lies just west of the Sandias. I hiked in the mountains plenty, and I had friends that lived over here, especially after I got to high school. Manzano High School was, and still is the high school that kids from the east mountains attended. I’ve always been interested in the geology of the mountains. Its most ancient of records are the rocks, which tell us that what is now the top of a mountain used to be at the bottom of a sea. But I didn’t become interested in the human history of the east mountains, its small towns, and the people who inhabited them until I moved here in 2017.This visiting neighbor told me he’d like to get his hands on a novel entitled Fiddlers and Fishermen because it was set in the east mountains. He’d searched, but he’d never been able to find a copy. That set me on a mission that began on Google, went to the public library, and finally to rare booksellers. What I discovered was that Fiddlers and Fishermen is one of two books written by Benjamin Frederick Clark. Born in Kansas in 1873, Clark moved into a cabin in Sandia Park, New Mexico in 1927. He passed away in that same cabin on May 30, 1947. He was 74 years old.

Back in 1947, Sandia Park was the area uphill from the little village of San Antonito. A dirt road went through the middle of it on its way up to the crest of the mountain. My area was on the outskirts of a village called La Madera, whose economy was based on truck farming, limestone mining, and timber. The stream that was the lifeblood of La Madera has ceased to flow and the town has become a ghost town. I drive a little over six miles to get my mail at the Sandia Park Post office.

Back in 1947, Sandia Park was the area uphill from the little village of San Antonito. A dirt road went through the middle of it on its way up to the crest of the mountain. My area was on the outskirts of a village called La Madera, whose economy was based on truck farming, limestone mining, and timber. The stream that was the lifeblood of La Madera has ceased to flow and the town has become a ghost town. I drive a little over six miles to get my mail at the Sandia Park Post office.Clark’s other book is a small tome of poems. Entitled Melodious Poems from the Hills, it was published in 1945 under the pen name of Sandia Bill by Crown Publications. I managed to get a copy delivered to my local library through interlibrary loan. The copy is signed, in pencil, by the author. A second pencil notation, reading “gift of the author 6/30/45” is written along the gutter of the first page. There is a picture of Clark playing his fiddle in the frontpages. I have included it here.

Melodious Poems from the Hills has ninety-six pages. Some pages have two short poems on them. Most have one poem, and a few poems span a couple of pages. The first poem, “When I Am Dead,” is mentioned in his obituary and is the reason he was cremated. When I Am Dead

When I am dead, don’t cry for me;

Just wrap me in a shroud

And burn me, that the vapors may

Help form some lovely cloud.

Then place my pictures and my dolls,

And my ashes pure and clean,

‘Neath my rosevine and that tree

That always is so green.

Just leave the earth plain and smooth—

I want no omark or stone.

Just let the yard look like it did;

When in flesh, it was my home.

Take care of my sweet rosevine

And that evergreen tree –

This still my home will be;

And may flowers bloom around by tome

While gay robins sing for me.

This was one of my favorites, and seems appropriate in a year that saw so much of the west burning:

The Dying Monarch

Here stands the monarch of the forest,

Slowly expiring on the mountainside,

Who only a few hours ago,

Was the embodiment of health and pride.

His kindred pines for miles around,

And neighboring aspens, oaks, and firs

Are slowly tumbling to the ground

In bulks of smoldering embers.

The Lively squirrels and cheerful birds

From these parts have fled,

And they’ll be homeless for awhile,

For their friendly trees are dead.

Stands here the monarch of the forest,

Preaching a sermon as he expires,

Broadcasting his message to the world:

“Oh, men, be careful with your fires.”

Like the poem above, many of Sandia Bill’s poems are about the nature that surrounded him. Some are about the people, mostly ranchers, who he associated with. A few tell tales of love lost and found, of pretty women, dangerous men, and faithful old dogs, horses, and mules. This one, dear reader, I find speaks his heart, and mine.

I Am Thankful

I am not a rich or famous man,

And perhaps I’ll never be.

But I am in love with many things

And they’re all in love with me.

I am thankful for the sweet sunshine,

For snow, the clouds, and summer showers.

I am thankful for the Love Divine,

For butterflies, the birds, and flowers.

I am thankful for the girl I love

With eyes so soft and blue;

I am thankful for the stars above,

But more thankful, dear, for you.

I have yet to get my hands on a copy of Fiddlers and Fishermen. The only copy I’ve managed to locate is housed in the special collections in Zimmerman Library on the University of New Mexico campus, and they are not willing to circulate it through interlibrary loan. The only way I can read this 76 page novella is to make an appointment to read it at the library. Zimmerman’s old reading room is a beautiful, contemplative space. I did much of my undergraduate study there because it was such a peaceful place. Perhaps someday soon I will jump through the hoops to make this appointment happen.

Jennifer Bohnhoff’s newest novel, Where Duty Calls, is set in New Mexico during the Civil War and is the first in a trilogy. Written for middle grade readers, it is a quick, informative read for adults. She lives and writes in the mountains east of Albuquerque, New Mexico, close to the camp the Confederate Army used as they advanced towards Santa Fe in the spring of 1862 that is pictured above. .

Published on August 14, 2022 23:00

July 26, 2022

Civil War Mules in Fact, Fiction, and Poetry

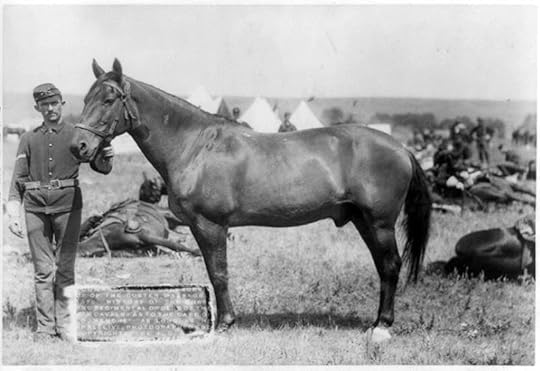

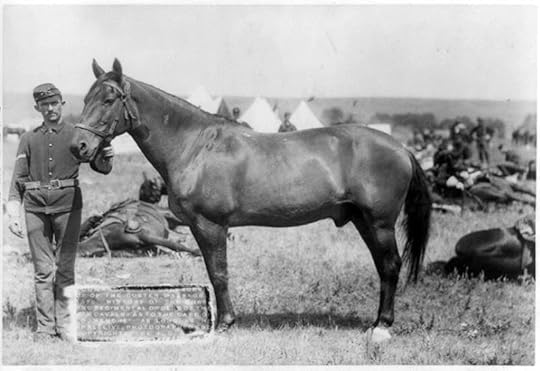

Mules were the backbone of both Confederate and Union Armies during the American Civil War. According to a page on the Stones River Battlefield site, about three million horses and mules served in the war. They pulled the supply wagons, pulled the limbers and caissons for cannons, and moved the ambulances.

Mules were the backbone of both Confederate and Union Armies during the American Civil War. According to a page on the Stones River Battlefield site, about three million horses and mules served in the war. They pulled the supply wagons, pulled the limbers and caissons for cannons, and moved the ambulances. Although mules died in battle, just like the soldiers they supported, a greater percentage died of overwork, disease, or starvation. Rarely was the daily feed ration for Union cavalry horses, ten pounds of hay and fourteen pounds of grain, available during the long campaigns.

Jemmy Martin, one of the lead characters in Where Duty Calls, my middle grade novel about the Civil War in New Mexico, loves the two mules who work on his family's farm. When his brother sells them to the Confederate Army, Jemmy decides to travel with them to protect them. He tries hard to find good forage for his mules after Major General Henry H. Sibley's army crosses into barren New Mexico territory on its way to capture the gold fields of Colorado. But Jemmy couldn't protect his mules from Union trickery. The night before the battle of Valverde, a Union spy named Paddy Graydon concocted a plan for killing the Confederate hoofstock using a couple of run-down mules as weapons. While his plan didn't work, he managed to spook the Confederate's pack mules. The animals, who'd been denied access to water for several days, stampeded down to the Rio Grande, where Union soldiers rounded them up. Jemmy finds himself continuing to follow the army even though his reason for being with them is gone.

Jemmy Martin, one of the lead characters in Where Duty Calls, my middle grade novel about the Civil War in New Mexico, loves the two mules who work on his family's farm. When his brother sells them to the Confederate Army, Jemmy decides to travel with them to protect them. He tries hard to find good forage for his mules after Major General Henry H. Sibley's army crosses into barren New Mexico territory on its way to capture the gold fields of Colorado. But Jemmy couldn't protect his mules from Union trickery. The night before the battle of Valverde, a Union spy named Paddy Graydon concocted a plan for killing the Confederate hoofstock using a couple of run-down mules as weapons. While his plan didn't work, he managed to spook the Confederate's pack mules. The animals, who'd been denied access to water for several days, stampeded down to the Rio Grande, where Union soldiers rounded them up. Jemmy finds himself continuing to follow the army even though his reason for being with them is gone.While Jemmy and his mules are fictional characters that I created for my novel, the story of Paddy Graydon is true. Graydon really did spook the Confederacy's pack mules, and the Union Army did really collect over 100 of the beasts when they broke to gain access to water. They lost over 100 animals and had to reconfigure their supply train. Before they left camp, the Confederates burned what they could no longer carry. In Hardtack and Coffee: The Unwritten Story of Army Life , Civil War veteran John D. Billings shares the story of another mule stampede. During the night of Oct. 28, 1863, Union General John White Geary and Confederate General James Longstreet were fighting at Wauhatchie, Tennessee. The din or battle unnerved about two hundred mules, who stampeded into a body of Rebels commanded by Wade Hampton. The rebels thought they were being attacked by cavalry and fell back.

To commemorate this incident, one Union soldier penned a poem based on Tennyson's Charge of the Light Brigade. Charge of the mule brigade

Half a mile, half a mile,

Half a mile onward,

Right through the Georgia troops

Broke the two hundred.

“Forward the Mule Brigade!”

“Charge for the Rebs!” they neighed.

Straight for the Georgia troops

Broke the two hundred.

“Forward the Mule Brigade!”

Was there a mule dismayed?

Not when the long ears felt

All their ropes sundered.

Theirs not to make reply,

Theirs not to reason why,

Theirs but to make Rebs fly.

On! to the Georgia troops

Broke the two hundred.

Mules to the right of them,

Mules to the left of them,

Mules behind them

Pawed, neighed, and thundered.

Breaking their own confines,

Breaking through Longstreet's lines

Into the Georgia troops,

Stormed the two hundred.

Wild all their eyes did glare,

Whisked all their tails in air

Scattering the chivalry there,

While all the world wondered.

Not a mule back bestraddled,

Yet how they all skedaddled--

Fled every Georgian,

Unsabred, unsaddled,

Scattered and sundered!

How they were routed there

By the two hundred!

Mules to the right of them,

Mules to the left of them,

Mules behind them

Pawed, neighed, and thundered;

Followed by hoof and head

Full many a hero fled,

Fain in the last ditch dead,

Back from an ass's jaw

All that was left of them,--

Left by the two hundred.

When can their glory fade?

Oh, the wild charge they made!

All the world wondered.

Honor the charge they made!

Honor the Mule Brigade,

Long-eared two hundred! The Stones River Battlefield Website stated that roughly half the horses and mules employed during the Civil War didn't survive. Jemmy Martin loses his to Paddy Graydon's plan. He spends the next two books in the Rebels Along the Rio Grande series trying to find them and return them to his home near San Antonio, Texas.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a retired middle school English and History teacher. She has written several novels, most of which are historical fiction for middle grade readers. Where Duty Calls is the first book in Rebels Along the Rio Grande, a trilogy set in New Mexico during the Civil War.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a retired middle school English and History teacher. She has written several novels, most of which are historical fiction for middle grade readers. Where Duty Calls is the first book in Rebels Along the Rio Grande, a trilogy set in New Mexico during the Civil War.

Published on July 26, 2022 23:00

July 17, 2022

There’s Gold in Them Thar Books!

Gold Rush Fever was an important part of America during the nineteenth century. The excitement and intrigue, the adventurous, desperate characters, and the challenges from other miners and from the elements of nature makes for awfully good reading for people of all ages. There is particularly good diggings for middle grade readers, ages 8-14.

The first American gold rush is one that few people remember. In 1799, a twelve-year-old boy named Conrad Reed found a 17-pound nugget of gold near his home in Cabarrus County, North Carolina. Not knowing what it was, the nugget was used as a doorstop until a jeweler recognized it and bought it. In 1802, word got out about the sale of that nugget and the Carolina gold rush was on.

A second gold rush began in Dahlonega, Georgia in 1829. The subsequent influx of miners and immigrants raised tensions with local Cherokee tribes, eventually leading to the forced removal of the tribes in what became known as the "Trail of Tears."

The most famous gold rush in American history began on January 24, 1848, when gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill in California. The surge ‘forty-niners,” people who immigrated to California hoping to strike it rich, caused California, which was not even a territory of the United States, to get on the fast-track to statehood. As in Georgia, Native Americans living near the goldfields were forcibly removed after clashing with miners. The next gold rush occurred in the Pike's Peak Country of western Kansas Territory and southwestern Nebraska Territory, in what soon became Colorado. The Pike's Peak Gold Rush began in July 1858. The estimated 100,000 gold seekers who took part in this rush were known as "fifty-niners" after 1859, the peak year of the rush. Their motto was “Pike's Peak or Bust!” even though the actual center of the mining activity was 85 miles north.

The next gold rush occurred in the Pike's Peak Country of western Kansas Territory and southwestern Nebraska Territory, in what soon became Colorado. The Pike's Peak Gold Rush began in July 1858. The estimated 100,000 gold seekers who took part in this rush were known as "fifty-niners" after 1859, the peak year of the rush. Their motto was “Pike's Peak or Bust!” even though the actual center of the mining activity was 85 miles north.

Cian Lachlann, one of the main characters in The Worst Enemy, book 2 in my Rebels Along the Rio Grande Trilogy (scheduled for release in 2023) is an orphaned Irish immigrant who becomes one the fifty-niners before joining the Colorado Volunteers and heading into New Mexico. The Book 1, Where Duty Calls, was published last month. It follows two boys through the Confederate invasion of New Mexico, up through the first battle. I am giving away five copies to people who would like a free copy in exchange for an honest critique. Email me at jennifer@jenniferbohnhoff.com if you’d like a copy.

The last great gold rush of the nineteenth century was the Klondike Gold Rush. This rush began in in 1896 when local miners in Yukon, in north-western Canada found gold. When news reached Seattle and San Francisco the following year, thousands of prospectors, known as "Klondikers," flooded the ports of Dyea and Skagway in Southeast Alaska, trekked over the Chilkoot or White Pass trails, then floated down the Yukon River to reach the goldfields. By the time many had made this arduous journey, the land had all been claimed. As with other gold rushes, the indigenous people of the area suffered greatly as their lands were overrun with desperate and unscrupulous prospectors.

If you want to strike gold with a middle grade reader, I suggest you try one of these books: Jasper and the Riddle of Riley's Mine

by Caroline Starr Rose

Jasper and the Riddle of Riley's Mine

by Caroline Starr Rose

Eleven-year-old Jasper Johnson follows his older brother Melvin, who’s run away from their abusive, alcoholic father. The brothers leave the small town of Kirkland, Washington and take a steamer to Alaska to join the Klondike Gold Rush. While he is a stowaway onboard the ship, Jasper overhears men talking about One-Eyed Riley, a prospector who left clues in the form of riddles that will reveal the location of his still-rich stake. Jasper decides he must find Riley’s mine, but in addition to unraveling the clues, the brothers must cross harsh terrain despite increasingly bad weather and having few supplies. Add to this a host of unscrupulous and dangerous people who are also searching for the mine, and the odds against these two boys are almost insurmountable. Jasper’s pluck overcomes many obstacles, and, with the help of a few good people interspersed amid the bad, the brothers find something even more valuable than gold. Caroline Starr Rose does a great job of intermingling facts with a great story so that readers will learn a lot about the history and topography of the Klondike while never feeling lectured to. More books on the Klondike Gold Rush:

More books on the Klondike Gold Rush:

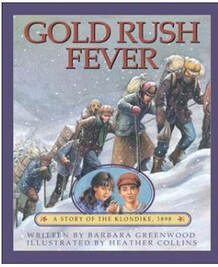

Gold Rush Fever: A Story of the Klondike, 1898 by Barbara Greenwood. 13-year-old Tim and his older brother, Roy, head off to the Klondike Gold Rush, where they face blinding snowstorms, raging rapids, backbreaking work and bitter disappointment. Each chapter in this book ends with facts, information, illustrations and photographs of the people and places of the time, and activities help bring the historical period to life. Call of the Klondike: A True Gold Rush Adventure by David Meissner and Kim Richardson Another story of two young men during the Klondike Gold Rush, this book uses first-hand diaries, letters, telegrams and news articles (written by Pearce) to tell the true story of Marshall Bond and Stanley Pearce, two college buddies who leave Seattle to search for gold. They meet Jack London, the author of Call of the Wild and White Fang, and had an adventure that reads as big as fiction, but is true.

Call of the Klondike: A True Gold Rush Adventure by David Meissner and Kim Richardson Another story of two young men during the Klondike Gold Rush, this book uses first-hand diaries, letters, telegrams and news articles (written by Pearce) to tell the true story of Marshall Bond and Stanley Pearce, two college buddies who leave Seattle to search for gold. They meet Jack London, the author of Call of the Wild and White Fang, and had an adventure that reads as big as fiction, but is true.

I Escaped The Gold Rush Fever: A California Gold Rush Survival Story

by Scott Peters. It’s 1852, and 14-year-old Hudson runs away from her domineering aunt in San Francisco to go in search of her father. She finds him along the Klamath River, where tempers among the California’s Gold Rush miners and the indigenous people are running high. When anger erupts into murder in an incident based on what is known as the Klamath River Conflict, Hudson finds herself trying to save herself and her wounded father. This fast-paced book 11th in the I Escaped Series, is filled with action and sure to be a hit with fans of the I Survived Series, reluctant readers, and readers with short attention spans. A back section has facts about the California Gold Rush.

I Escaped The Gold Rush Fever: A California Gold Rush Survival Story

by Scott Peters. It’s 1852, and 14-year-old Hudson runs away from her domineering aunt in San Francisco to go in search of her father. She finds him along the Klamath River, where tempers among the California’s Gold Rush miners and the indigenous people are running high. When anger erupts into murder in an incident based on what is known as the Klamath River Conflict, Hudson finds herself trying to save herself and her wounded father. This fast-paced book 11th in the I Escaped Series, is filled with action and sure to be a hit with fans of the I Survived Series, reluctant readers, and readers with short attention spans. A back section has facts about the California Gold Rush.

More books about the California Gold Rush

More books about the California Gold Rush

Gold Rush Girl, by Avi. Victoria Blaisdell stows away on the ship so that she can accompany her father from Rhode Island to California as he searches for gold. When her younger brother is kidnapped, Tory must search for him in Rotten Row, a part of San Francisco Bay crowded with hundreds of abandoned ships. By the Great Horn Spoon! by Sid Fleischman Twelve-year-old Jack goes to California in search of gold to help his aunt keep her home. His trusty butler, Praiseworthy, joins him on the adventure which will have readers laughing out loud!

By the Great Horn Spoon! by Sid Fleischman Twelve-year-old Jack goes to California in search of gold to help his aunt keep her home. His trusty butler, Praiseworthy, joins him on the adventure which will have readers laughing out loud!

Want even more books about American Gold Rushes for middle grade readers? Check out this list.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a retired middle school language arts and history teacher. She now stays home and writes, writes, writes, mostly historical fiction for middle grade readers.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a retired middle school language arts and history teacher. She now stays home and writes, writes, writes, mostly historical fiction for middle grade readers.

Jennifer is also an affiliate at Bookshop.org, an online bookseller that gives 75% of its profits to independent bookstores, authors, and reviewers. As an affiliate, she receives a commission when people buy books by clicking through links on her blog. A matching commission goes to an independent bookseller.

Please do not see her affiliation with Bookshop.org as a discouragement to shop directly at your local independent bookseller or to borrow from your local library. Everyone should support their public library and local booksellers as much as possible. .

The first American gold rush is one that few people remember. In 1799, a twelve-year-old boy named Conrad Reed found a 17-pound nugget of gold near his home in Cabarrus County, North Carolina. Not knowing what it was, the nugget was used as a doorstop until a jeweler recognized it and bought it. In 1802, word got out about the sale of that nugget and the Carolina gold rush was on.

A second gold rush began in Dahlonega, Georgia in 1829. The subsequent influx of miners and immigrants raised tensions with local Cherokee tribes, eventually leading to the forced removal of the tribes in what became known as the "Trail of Tears."

The most famous gold rush in American history began on January 24, 1848, when gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill in California. The surge ‘forty-niners,” people who immigrated to California hoping to strike it rich, caused California, which was not even a territory of the United States, to get on the fast-track to statehood. As in Georgia, Native Americans living near the goldfields were forcibly removed after clashing with miners.

The next gold rush occurred in the Pike's Peak Country of western Kansas Territory and southwestern Nebraska Territory, in what soon became Colorado. The Pike's Peak Gold Rush began in July 1858. The estimated 100,000 gold seekers who took part in this rush were known as "fifty-niners" after 1859, the peak year of the rush. Their motto was “Pike's Peak or Bust!” even though the actual center of the mining activity was 85 miles north.

The next gold rush occurred in the Pike's Peak Country of western Kansas Territory and southwestern Nebraska Territory, in what soon became Colorado. The Pike's Peak Gold Rush began in July 1858. The estimated 100,000 gold seekers who took part in this rush were known as "fifty-niners" after 1859, the peak year of the rush. Their motto was “Pike's Peak or Bust!” even though the actual center of the mining activity was 85 miles north.Cian Lachlann, one of the main characters in The Worst Enemy, book 2 in my Rebels Along the Rio Grande Trilogy (scheduled for release in 2023) is an orphaned Irish immigrant who becomes one the fifty-niners before joining the Colorado Volunteers and heading into New Mexico. The Book 1, Where Duty Calls, was published last month. It follows two boys through the Confederate invasion of New Mexico, up through the first battle. I am giving away five copies to people who would like a free copy in exchange for an honest critique. Email me at jennifer@jenniferbohnhoff.com if you’d like a copy.

The last great gold rush of the nineteenth century was the Klondike Gold Rush. This rush began in in 1896 when local miners in Yukon, in north-western Canada found gold. When news reached Seattle and San Francisco the following year, thousands of prospectors, known as "Klondikers," flooded the ports of Dyea and Skagway in Southeast Alaska, trekked over the Chilkoot or White Pass trails, then floated down the Yukon River to reach the goldfields. By the time many had made this arduous journey, the land had all been claimed. As with other gold rushes, the indigenous people of the area suffered greatly as their lands were overrun with desperate and unscrupulous prospectors.