Jennifer Bohnhoff's Blog, page 11

January 2, 2024

New Road, Old History

Sometimes I come across a street name that makes me wonder. This happened recently when I was walking through an Albuquerque neighborhood names Heritage Hills with a couple of my friends. We came across a street named Messervy Avenue. Because of the neighborhood, I assumed it was a person’s name, and that the person had done something important, but I knew of no one in American history by that name, so I had to do a little research.

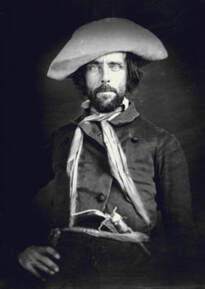

Turns out, the street was named after William Sluman Messervy, who was born in Salem, Massachusetts on August 26, 1812. Messervy was the eldest son in a family of ten children born to a sea captain in the East Indies trade and his wife. His middle name comes from his maternal grandfather, Captain William Sluman, who had been killed during the American Revolutionary War while in command of a private armed vessel.

Turns out, the street was named after William Sluman Messervy, who was born in Salem, Massachusetts on August 26, 1812. Messervy was the eldest son in a family of ten children born to a sea captain in the East Indies trade and his wife. His middle name comes from his maternal grandfather, Captain William Sluman, who had been killed during the American Revolutionary War while in command of a private armed vessel.

Messervy began his career in business as a clerk and book-keeper in a large firm in Boston. In 1834, he got a job in St. Louis, Missouri, and by 1839, he was in business for himself, traveling on the Santa Fe Trail and trading with Mexico, including the Mexican territory of Santa Fe de Nuevo México, which later became the American state of New Mexico. Messervy was in Chihuahua when the Mexican–American War began in April 1846. Like other United States citizens, he was interned there, but freed by troops led by Colonel A. W. Doniphan after the Battle of the Sacramento River in February 1847. When the war ended early in 1848, Messervy moved to Santa Fe, which had been annexed by the U.S. and was under an American provisional government. By 1851, his trading firm called Messervy and Webb had the leading merchant house in New Mexico, sending between sixty and seventy wagons along the Santa Fe trail each year. It delivered general merchandise to the region’s natives in addition to American settlers and federal and territorial government officials throughout New Mexico.

In June 1850, New Mexico adopted a state constitution and Messervy was elected to serve as its first member of Congress. However, Messervy was never officially seated because Congress did not accept New Mexico as a state. The Territory of New Mexico, organized when the Compromise of 1850 passed that September, recognized another man, Richard Hanson Weightman, as New Mexico Territory’s Congressional delegate.

New Mexico Territory, 1852, including most of the later Arizona Territory, but not the Gadsden Purchase of 1854 This setback did not end Messervy’s political career. On April 8, 1853 President Franklin Pierce appointed him to be the Secretary of the New Mexico Territory. A year later, he became its acting Governor when its appointed governor, David Meriwether, went out of state. Messervy was then appointed superintendent of Indian affairs in New Mexico, a difficult position since the Jicarilla branch of the Apaches were then at war with America.

New Mexico Territory, 1852, including most of the later Arizona Territory, but not the Gadsden Purchase of 1854 This setback did not end Messervy’s political career. On April 8, 1853 President Franklin Pierce appointed him to be the Secretary of the New Mexico Territory. A year later, he became its acting Governor when its appointed governor, David Meriwether, went out of state. Messervy was then appointed superintendent of Indian affairs in New Mexico, a difficult position since the Jicarilla branch of the Apaches were then at war with America.

By July, the stress of his three jobs had become too great. He resigned his positions and sold both his house on the Santa Fe Plaza and the Exchange Hotel, Santa Fe’s liveliest venue. He returned to Salem, where he served as mayor from 1856 to 1858, was a director of some local corporations, and was active in scientific and literary societies. He was also a justice of the peace at Salem. Although he had been a Democrat throughout his life, he joined the Republican party during the Civil War. Messervy died after a long illness on February 19, 1886.

William Sluman Messervy may not be a household name, even in New Mexico, but he had an important role in the Americanization of New Mexico, and he was important enough that someone thought to name a street in Albuquerque after him. Jennifer Bohnhoff taught New Mexico history at the middle school level for a number of years. She is now an author of historical and contemporary fiction for middle school through adult readers, including Rebels Along the Rio Grande, a trilogy of novels set in New Mexico during the Civil War.

Turns out, the street was named after William Sluman Messervy, who was born in Salem, Massachusetts on August 26, 1812. Messervy was the eldest son in a family of ten children born to a sea captain in the East Indies trade and his wife. His middle name comes from his maternal grandfather, Captain William Sluman, who had been killed during the American Revolutionary War while in command of a private armed vessel.

Turns out, the street was named after William Sluman Messervy, who was born in Salem, Massachusetts on August 26, 1812. Messervy was the eldest son in a family of ten children born to a sea captain in the East Indies trade and his wife. His middle name comes from his maternal grandfather, Captain William Sluman, who had been killed during the American Revolutionary War while in command of a private armed vessel.

Messervy began his career in business as a clerk and book-keeper in a large firm in Boston. In 1834, he got a job in St. Louis, Missouri, and by 1839, he was in business for himself, traveling on the Santa Fe Trail and trading with Mexico, including the Mexican territory of Santa Fe de Nuevo México, which later became the American state of New Mexico. Messervy was in Chihuahua when the Mexican–American War began in April 1846. Like other United States citizens, he was interned there, but freed by troops led by Colonel A. W. Doniphan after the Battle of the Sacramento River in February 1847. When the war ended early in 1848, Messervy moved to Santa Fe, which had been annexed by the U.S. and was under an American provisional government. By 1851, his trading firm called Messervy and Webb had the leading merchant house in New Mexico, sending between sixty and seventy wagons along the Santa Fe trail each year. It delivered general merchandise to the region’s natives in addition to American settlers and federal and territorial government officials throughout New Mexico.

In June 1850, New Mexico adopted a state constitution and Messervy was elected to serve as its first member of Congress. However, Messervy was never officially seated because Congress did not accept New Mexico as a state. The Territory of New Mexico, organized when the Compromise of 1850 passed that September, recognized another man, Richard Hanson Weightman, as New Mexico Territory’s Congressional delegate.

New Mexico Territory, 1852, including most of the later Arizona Territory, but not the Gadsden Purchase of 1854 This setback did not end Messervy’s political career. On April 8, 1853 President Franklin Pierce appointed him to be the Secretary of the New Mexico Territory. A year later, he became its acting Governor when its appointed governor, David Meriwether, went out of state. Messervy was then appointed superintendent of Indian affairs in New Mexico, a difficult position since the Jicarilla branch of the Apaches were then at war with America.

New Mexico Territory, 1852, including most of the later Arizona Territory, but not the Gadsden Purchase of 1854 This setback did not end Messervy’s political career. On April 8, 1853 President Franklin Pierce appointed him to be the Secretary of the New Mexico Territory. A year later, he became its acting Governor when its appointed governor, David Meriwether, went out of state. Messervy was then appointed superintendent of Indian affairs in New Mexico, a difficult position since the Jicarilla branch of the Apaches were then at war with America.

By July, the stress of his three jobs had become too great. He resigned his positions and sold both his house on the Santa Fe Plaza and the Exchange Hotel, Santa Fe’s liveliest venue. He returned to Salem, where he served as mayor from 1856 to 1858, was a director of some local corporations, and was active in scientific and literary societies. He was also a justice of the peace at Salem. Although he had been a Democrat throughout his life, he joined the Republican party during the Civil War. Messervy died after a long illness on February 19, 1886.

William Sluman Messervy may not be a household name, even in New Mexico, but he had an important role in the Americanization of New Mexico, and he was important enough that someone thought to name a street in Albuquerque after him. Jennifer Bohnhoff taught New Mexico history at the middle school level for a number of years. She is now an author of historical and contemporary fiction for middle school through adult readers, including Rebels Along the Rio Grande, a trilogy of novels set in New Mexico during the Civil War.

Published on January 02, 2024 09:09

December 14, 2023

Quite the Plum

A couple of weeks ago I wrote a blog about wasailling and figgy pudding and I mentioned that the word plum didn’t necessarily mean a purple tree fruit. It's time to elaborate on that!

A couple of weeks ago I wrote a blog about wasailling and figgy pudding and I mentioned that the word plum didn’t necessarily mean a purple tree fruit. It's time to elaborate on that!You probably know the old nursery rhyme about Jack Horner, a boy eating his Christmas pie. If you don't, here it is:

William Wallace Denslow’s illustration of the rhyme, 1902

William Wallace Denslow’s illustration of the rhyme, 1902 Little Jack Horner

Sat in the corner,

Eating his Christmas pie;

He put in his thumb,

And pulled out a plum,

And said,

"What a good boy am I!"

Recognize the style of the illustration? Denslow illustrated the Wizard of Oz books!

The nursery rhyme is a fun little ditty, but it may have more behind it than you'd think.

Webster's Dictionary says that, in addition to being the fruit of the prunus tree, a plum can be defined as something superior or very desirable, especially : something desirable given in return for a favor, and that may be what the nursery rhyme is really about.

No one knows just how old this nursery rhyme is. It was first published in Mother Goose's melody, or, Sonnets for the cradle, which may have first been published in 1765, but is mentioned in a 1725 satire and may be much older than that.

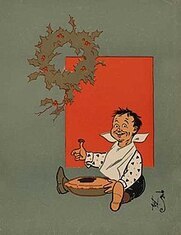

In the 19th century, it was suggested that the poem is related to the period from 1536-1541, when the monastic system in England was being destroyed by Henry VIII after Parliament passed the Act of Supremacy, which made him the supreme head of the church in England, separating England from papal authority. Henry then expropriated the incomes of the monasteries and convents, increasing the regular income of the Crown. Much of the former monastic properties were sold off to fund Henry's military campaigns in the 1540s. By January 1539, Glastonbury Monastery was the last remaining religious property in Somerset that had not been dissolved. Glastonbury abbey was one of the richest and most influential in all England, with one hundred monks living in it. Many of the sons of the nobility and gentry were educated there before going on to university.

In the 19th century, it was suggested that the poem is related to the period from 1536-1541, when the monastic system in England was being destroyed by Henry VIII after Parliament passed the Act of Supremacy, which made him the supreme head of the church in England, separating England from papal authority. Henry then expropriated the incomes of the monasteries and convents, increasing the regular income of the Crown. Much of the former monastic properties were sold off to fund Henry's military campaigns in the 1540s. By January 1539, Glastonbury Monastery was the last remaining religious property in Somerset that had not been dissolved. Glastonbury abbey was one of the richest and most influential in all England, with one hundred monks living in it. Many of the sons of the nobility and gentry were educated there before going on to university.The story is that Richard Whiting, the abbot, sent his steward, Thomas Horner, to London with a huge Christmas pie, into which he had placed the deeds to a dozen manors which the Monastery owned. The Abbot's hope was that by giving away such valuable lands, the King would allow the monastery to remain intact. During the journey Horner opened the pie and extracted the deeds of Mells Manor, which he kept for himself. While a manor would indeed be the something superior or very desirable, meant to be given to the Kind in return for the favor of the monastery's continued existence, there may be another wrinkle to the use of the word plum. Mells Manor, which is in the Mendip Hills, had several lead mines on it, and the word plum might be a pun on the Latin plumbum, or lead.

Is this story true? While records exist that prove Thomas Horner became the owner of the manor, later owners assert that he didn't steal the deed, but purchased it from the abbey.

Regardless of whether Horner bought or stole the deed, the Christmas pie did not produce the intended result. On November 15, 1539, (aged 77 - 78, the king had the 78 year old abbot convicted of treason for remaining loyal to Rome. He was dragged to the top of Glastonbury Tor, where he was hanged, drawn and quartered. Whiting's head was hung over the west gate[ of his deserted abbey, and his limbs were displayed on the townwalls of Wells, Bath, Ilchester, and Bridgwater.

Regardless of whether Horner bought or stole the deed, the Christmas pie did not produce the intended result. On November 15, 1539, (aged 77 - 78, the king had the 78 year old abbot convicted of treason for remaining loyal to Rome. He was dragged to the top of Glastonbury Tor, where he was hanged, drawn and quartered. Whiting's head was hung over the west gate[ of his deserted abbey, and his limbs were displayed on the townwalls of Wells, Bath, Ilchester, and Bridgwater.Whiting was beatified by the Catholic Church in 1895. Jennifer Bohnhoff is the author of several works of historical fiction, none of which have a Christmas pie or plum pudding in them. You can read more about her and her books here.

Published on December 14, 2023 09:05

December 5, 2023

Some of the Heroes of Pearl Harbor

Eighty-two years ago, on December 7, 1941, the Japanese Empire launched a surprise attack on the U.S. base at Pearl Harbor that was intended to knock the United States out of a war in the Pacific. Instead, it raised the anger and heroic, fighting spirit of the American people and caused our entry into World War II. Countless acts of heroism and sacrifice occurred on that day, and sixteen men were awarded the medal of honor. Some people are surprised to know that the attack went far beyond the borders of Pearl Harbor, and that the casualties stretched beyond Navy personnel.

The first target of the striking Japanese bomber and fighter planes was the Marine Corps Air Station at Ewa, on Oahu’s northern shore. Although the runway was not bombed and remained serviceable, all forty-eight aircraft based there were destroyed

Chief Aviation Ordnanceman John William Finn with his Medal of Honor (Photo: Naval History & Heritage Command) The Naval Air Station at Kaneohe Bay, on Oahu’s eastern side was hit next. Chief Aviation Ordnanceman John William Finn was in charge of a 20-man unit whose main job was to maintain the weapons on PBY Catalina flying boats stationed there. On the morning of the 7th, he was at home when he heard gunfire and a neighbor started banging on his door to tell him he was needed at his squadron. He drove the mile to the airfield and found most of the Catalinas already burning. He joined his men, who were firing back at the Japanese flyers, either by climbing into the burning Catalina’s to use their guns, or by taking the guns off and putting them on other mounts. Finn pulled a .50 caliber M2 Browning machine gun from the unit’s painter, placed it on a mount, and opened fire. Although he suffered a total of 21 wounds, including a bullet through his foot and another one through his shoulder, he continued firing for two hours. When Finn died in 2010 at the age of 100, he was the last surviving Medal of Honor recipient from the Battle of Pearl Harbor. He remains the only aviation ordnanceman to ever receive the decoration. Most people know that the greatest loss of life during the attack at Pear Harbor happened on the USS Arizona. Of the 2,341 service members that died on Dec. 7, 1941, almost half, a total of 1,177, died on that one ship. The high mortality rate was due to the detonation of the forward magazines when a bomb hit them, killing more than two-thirds of her crew. The crew of the USS Arizona included 38 sets of brothers, including three sets of three brothers. Of those 79 people, 63 died as a result of the attack. Of the ship’s 82 Marines, only 3 officers and 12 enlisted men survived.

Chief Aviation Ordnanceman John William Finn with his Medal of Honor (Photo: Naval History & Heritage Command) The Naval Air Station at Kaneohe Bay, on Oahu’s eastern side was hit next. Chief Aviation Ordnanceman John William Finn was in charge of a 20-man unit whose main job was to maintain the weapons on PBY Catalina flying boats stationed there. On the morning of the 7th, he was at home when he heard gunfire and a neighbor started banging on his door to tell him he was needed at his squadron. He drove the mile to the airfield and found most of the Catalinas already burning. He joined his men, who were firing back at the Japanese flyers, either by climbing into the burning Catalina’s to use their guns, or by taking the guns off and putting them on other mounts. Finn pulled a .50 caliber M2 Browning machine gun from the unit’s painter, placed it on a mount, and opened fire. Although he suffered a total of 21 wounds, including a bullet through his foot and another one through his shoulder, he continued firing for two hours. When Finn died in 2010 at the age of 100, he was the last surviving Medal of Honor recipient from the Battle of Pearl Harbor. He remains the only aviation ordnanceman to ever receive the decoration. Most people know that the greatest loss of life during the attack at Pear Harbor happened on the USS Arizona. Of the 2,341 service members that died on Dec. 7, 1941, almost half, a total of 1,177, died on that one ship. The high mortality rate was due to the detonation of the forward magazines when a bomb hit them, killing more than two-thirds of her crew. The crew of the USS Arizona included 38 sets of brothers, including three sets of three brothers. Of those 79 people, 63 died as a result of the attack. Of the ship’s 82 Marines, only 3 officers and 12 enlisted men survived.

Real Admiral Isaac Campbell Kidd, the commander of Battleship Division One, which included the USS Pennsylvania, Arizona and Nevada, rushed to the Arizona, the flagship for the division, as soon as the battle began. He joined the ship’s captain, Franklin Van Valkenburgh. Both men were killed by the explosion and their bodies were never found. However, both men’s Annapolis Naval Academy rings were recovered. Kidd’s ring was fused to the bulkhead of the bridge.

The second largest loss of life was on the USS Oklahoma, which lost 429 men. By June 1944, Navy personnel had managed to identify the remains of only 35 of the recovered bodies. The rest were buried as Unknowns at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu. In 2015, the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, through a partnership with the Department of Veterans Affairs, exhumed the unknown remains and began the lengthy identification process. Over 300 sailors and Marines from Oklahoma have since been identified and returned home.

The USS West Virginia lost 106 men. The USS California lost 105 lost. Other casualties occurred on the ground. Hickam Field, that lost 191 people, including five of the 49 civilians killed on December 7. Some of the civilians were killed by the enemy and some died as a result of friendly fire. One Medal of Honor recipient was not anywhere near Pearl Harbor that day. Sand Island in Midway Atoll was also attacked on December 7th. When a shell from a Japanese ship struck the command post of Battery H, First Lieutenant George Ham Cannon was wounded. He refused rescue until the other men wounded by the same shell were taken care of, and continued to direct his command post until forcibly removed. He later died of his injuries. Lieutenant Cannon is the only Marine recipient of the Medal of Honor for actions taken on December 7, 1941. Jennifer Bohnhoff is a retired history and English teacher who is now writing historical fiction for children and adults. Her mother was raised on Oahu and watched the bombing of Pearl Harbor when she was a young girl. The author also lived in Hawaii as a child and visited the USS Arizona numerous time on class field trips. She brought her sons to visit while they were on vacation because she thinks it is important that future generations continue to remember the sacrifices of their forefathers.

One Medal of Honor recipient was not anywhere near Pearl Harbor that day. Sand Island in Midway Atoll was also attacked on December 7th. When a shell from a Japanese ship struck the command post of Battery H, First Lieutenant George Ham Cannon was wounded. He refused rescue until the other men wounded by the same shell were taken care of, and continued to direct his command post until forcibly removed. He later died of his injuries. Lieutenant Cannon is the only Marine recipient of the Medal of Honor for actions taken on December 7, 1941. Jennifer Bohnhoff is a retired history and English teacher who is now writing historical fiction for children and adults. Her mother was raised on Oahu and watched the bombing of Pearl Harbor when she was a young girl. The author also lived in Hawaii as a child and visited the USS Arizona numerous time on class field trips. She brought her sons to visit while they were on vacation because she thinks it is important that future generations continue to remember the sacrifices of their forefathers.

To any who are veterans or presently serving, Jennifer Bohnhoff thanks you for your service.

The first target of the striking Japanese bomber and fighter planes was the Marine Corps Air Station at Ewa, on Oahu’s northern shore. Although the runway was not bombed and remained serviceable, all forty-eight aircraft based there were destroyed

Chief Aviation Ordnanceman John William Finn with his Medal of Honor (Photo: Naval History & Heritage Command) The Naval Air Station at Kaneohe Bay, on Oahu’s eastern side was hit next. Chief Aviation Ordnanceman John William Finn was in charge of a 20-man unit whose main job was to maintain the weapons on PBY Catalina flying boats stationed there. On the morning of the 7th, he was at home when he heard gunfire and a neighbor started banging on his door to tell him he was needed at his squadron. He drove the mile to the airfield and found most of the Catalinas already burning. He joined his men, who were firing back at the Japanese flyers, either by climbing into the burning Catalina’s to use their guns, or by taking the guns off and putting them on other mounts. Finn pulled a .50 caliber M2 Browning machine gun from the unit’s painter, placed it on a mount, and opened fire. Although he suffered a total of 21 wounds, including a bullet through his foot and another one through his shoulder, he continued firing for two hours. When Finn died in 2010 at the age of 100, he was the last surviving Medal of Honor recipient from the Battle of Pearl Harbor. He remains the only aviation ordnanceman to ever receive the decoration. Most people know that the greatest loss of life during the attack at Pear Harbor happened on the USS Arizona. Of the 2,341 service members that died on Dec. 7, 1941, almost half, a total of 1,177, died on that one ship. The high mortality rate was due to the detonation of the forward magazines when a bomb hit them, killing more than two-thirds of her crew. The crew of the USS Arizona included 38 sets of brothers, including three sets of three brothers. Of those 79 people, 63 died as a result of the attack. Of the ship’s 82 Marines, only 3 officers and 12 enlisted men survived.

Chief Aviation Ordnanceman John William Finn with his Medal of Honor (Photo: Naval History & Heritage Command) The Naval Air Station at Kaneohe Bay, on Oahu’s eastern side was hit next. Chief Aviation Ordnanceman John William Finn was in charge of a 20-man unit whose main job was to maintain the weapons on PBY Catalina flying boats stationed there. On the morning of the 7th, he was at home when he heard gunfire and a neighbor started banging on his door to tell him he was needed at his squadron. He drove the mile to the airfield and found most of the Catalinas already burning. He joined his men, who were firing back at the Japanese flyers, either by climbing into the burning Catalina’s to use their guns, or by taking the guns off and putting them on other mounts. Finn pulled a .50 caliber M2 Browning machine gun from the unit’s painter, placed it on a mount, and opened fire. Although he suffered a total of 21 wounds, including a bullet through his foot and another one through his shoulder, he continued firing for two hours. When Finn died in 2010 at the age of 100, he was the last surviving Medal of Honor recipient from the Battle of Pearl Harbor. He remains the only aviation ordnanceman to ever receive the decoration. Most people know that the greatest loss of life during the attack at Pear Harbor happened on the USS Arizona. Of the 2,341 service members that died on Dec. 7, 1941, almost half, a total of 1,177, died on that one ship. The high mortality rate was due to the detonation of the forward magazines when a bomb hit them, killing more than two-thirds of her crew. The crew of the USS Arizona included 38 sets of brothers, including three sets of three brothers. Of those 79 people, 63 died as a result of the attack. Of the ship’s 82 Marines, only 3 officers and 12 enlisted men survived. Real Admiral Isaac Campbell Kidd, the commander of Battleship Division One, which included the USS Pennsylvania, Arizona and Nevada, rushed to the Arizona, the flagship for the division, as soon as the battle began. He joined the ship’s captain, Franklin Van Valkenburgh. Both men were killed by the explosion and their bodies were never found. However, both men’s Annapolis Naval Academy rings were recovered. Kidd’s ring was fused to the bulkhead of the bridge.

The second largest loss of life was on the USS Oklahoma, which lost 429 men. By June 1944, Navy personnel had managed to identify the remains of only 35 of the recovered bodies. The rest were buried as Unknowns at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu. In 2015, the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, through a partnership with the Department of Veterans Affairs, exhumed the unknown remains and began the lengthy identification process. Over 300 sailors and Marines from Oklahoma have since been identified and returned home.

The USS West Virginia lost 106 men. The USS California lost 105 lost. Other casualties occurred on the ground. Hickam Field, that lost 191 people, including five of the 49 civilians killed on December 7. Some of the civilians were killed by the enemy and some died as a result of friendly fire.

One Medal of Honor recipient was not anywhere near Pearl Harbor that day. Sand Island in Midway Atoll was also attacked on December 7th. When a shell from a Japanese ship struck the command post of Battery H, First Lieutenant George Ham Cannon was wounded. He refused rescue until the other men wounded by the same shell were taken care of, and continued to direct his command post until forcibly removed. He later died of his injuries. Lieutenant Cannon is the only Marine recipient of the Medal of Honor for actions taken on December 7, 1941. Jennifer Bohnhoff is a retired history and English teacher who is now writing historical fiction for children and adults. Her mother was raised on Oahu and watched the bombing of Pearl Harbor when she was a young girl. The author also lived in Hawaii as a child and visited the USS Arizona numerous time on class field trips. She brought her sons to visit while they were on vacation because she thinks it is important that future generations continue to remember the sacrifices of their forefathers.

One Medal of Honor recipient was not anywhere near Pearl Harbor that day. Sand Island in Midway Atoll was also attacked on December 7th. When a shell from a Japanese ship struck the command post of Battery H, First Lieutenant George Ham Cannon was wounded. He refused rescue until the other men wounded by the same shell were taken care of, and continued to direct his command post until forcibly removed. He later died of his injuries. Lieutenant Cannon is the only Marine recipient of the Medal of Honor for actions taken on December 7, 1941. Jennifer Bohnhoff is a retired history and English teacher who is now writing historical fiction for children and adults. Her mother was raised on Oahu and watched the bombing of Pearl Harbor when she was a young girl. The author also lived in Hawaii as a child and visited the USS Arizona numerous time on class field trips. She brought her sons to visit while they were on vacation because she thinks it is important that future generations continue to remember the sacrifices of their forefathers. To any who are veterans or presently serving, Jennifer Bohnhoff thanks you for your service.

Published on December 05, 2023 23:00

November 30, 2023

Wassailing for Figgy Pudding

As I write this, snow is falling outside my window, covering the ground with a soft and beautiful layer and definitely making it feel like the Christmas season is upon us. And though I try to ignore them, carols keep playing in my head.

As I write this, snow is falling outside my window, covering the ground with a soft and beautiful layer and definitely making it feel like the Christmas season is upon us. And though I try to ignore them, carols keep playing in my head.

Have you ever heard the song "Here We Come a-Wassailing" and wondered what that meant? Evidently a lot of people have, prompting someone to change the words to “Here We Come a-Caroling.” Wassailing is an old English tradition of going door-to-door, singing and being offered a drink from the wassail bowl in exchange. During the Middle Ages, the wassail was traditionally held on Twelfth Night, or January 6, and the wassailers were peasants who came wassailing at their feudal lords’ doors. The lord of the manor would give food and drink to his peasants in exchange for their blessing and goodwill.

Peasants also wassailed the trees in their orchards, assuring that there would be plenty of fruit in the coming year.

The word "wassail" came to English from Old Norse. Originally, in Old English it was used as the phrase hál wes þú. Hál is related to the word hale, and in hale and hearty, wes is a verb of being, like is or was, and þú is related to you, or thou, the first letter being pronounced as a soft th, so it loosely translates as healthy be you. Eventually this was shortened to wes hál. By 1300, it had become kind of a toast, and then the drink itself, often a warm wine or cider beverage, took on the toast as its name. By 1400, wassail became a verb: wassailing, which meant celebrating.

The word "wassail" came to English from Old Norse. Originally, in Old English it was used as the phrase hál wes þú. Hál is related to the word hale, and in hale and hearty, wes is a verb of being, like is or was, and þú is related to you, or thou, the first letter being pronounced as a soft th, so it loosely translates as healthy be you. Eventually this was shortened to wes hál. By 1300, it had become kind of a toast, and then the drink itself, often a warm wine or cider beverage, took on the toast as its name. By 1400, wassail became a verb: wassailing, which meant celebrating.  Over time, this changed, and by the 1600s many people were complaining about rowdy gangs of young men who went door to door demanding drink and food and vandalizing houses when they didn’t get what they wanted. This helps explain the line in “We Wish You a Merry Christmas” when the singers demand “Now, bring us some figgy pudding . . . We won’t go until we get some.” So, what is figgy pudding? Although sometimes it is called plum pudding or Christmas pudding, it has been a staple in England since the 1300s. Then, word plum didn’t necessarily mean a purple tree fruit; it meant any treat. Thus, when little Jack Horner stuck his thumb into a pie and pulled out a plum, it didn’t mean what we think it means (but that is the subject for another blog!) Plum pudding meant a pudding with good things in it, and often had a mixture of beef or mutton with raisins, prunes, figs, wine, and spices rather like what we now call mincemeat. When Oliver Cromwell was Lord Protector of England from December 1653 until his death in September 1658, he decreed that all this demanding of food and drink had gotten out of hand and was detracting from the true spirit of Christmas. He banned figgy puddings, wassailing, the singing of carols, and many other Christmas traditions. King George I reinstated Christmas celebrations, thereby earning the nickname “pudding king.”

Over time, this changed, and by the 1600s many people were complaining about rowdy gangs of young men who went door to door demanding drink and food and vandalizing houses when they didn’t get what they wanted. This helps explain the line in “We Wish You a Merry Christmas” when the singers demand “Now, bring us some figgy pudding . . . We won’t go until we get some.” So, what is figgy pudding? Although sometimes it is called plum pudding or Christmas pudding, it has been a staple in England since the 1300s. Then, word plum didn’t necessarily mean a purple tree fruit; it meant any treat. Thus, when little Jack Horner stuck his thumb into a pie and pulled out a plum, it didn’t mean what we think it means (but that is the subject for another blog!) Plum pudding meant a pudding with good things in it, and often had a mixture of beef or mutton with raisins, prunes, figs, wine, and spices rather like what we now call mincemeat. When Oliver Cromwell was Lord Protector of England from December 1653 until his death in September 1658, he decreed that all this demanding of food and drink had gotten out of hand and was detracting from the true spirit of Christmas. He banned figgy puddings, wassailing, the singing of carols, and many other Christmas traditions. King George I reinstated Christmas celebrations, thereby earning the nickname “pudding king.”

There are many variations on both wassail and figgy pudding. Here are two that you might want to try. Wassail 2 quarts apple cider

1 pint cranberry juice

¾ cup sugar

1 tsp aromatic bitters

2 sticks cinnamon

1 tsp whole allspice

1 small orange, studded with 20 cloves

1 cup rum (optional)

Put all ingredients into a crockpot and cook on high for 1 hour or low 4-8 hours, Or put in a saucepan and warm on the stove: do not boil! Plum Duff This is an old family recipe that my mother used to serve. I have no idea why it is called a duff. If you do, I'd love to hear it.

Put in saucepan and melt over medium heat:

½ cup shortening

1 cup brown sugar

Beat well, then beat into shortening mixture:

2 eggs

2 cups cooked, mashed prunes

Add and stir:

1 cup flour

Dissolve 1 tsp soda in 1 TBS milk and mix into prune mixture.

Fill greased 8” pudding molds 2/3 full and steam for 1 hour.

Or fill two greased 1 pound coffee cans (do they even make these anymore?) and steam for 1 hour

Or bake in a greased 8” square pan for 20-30 minutes at 350°

Serve with sweetened whipped cream or hard sauce. If you've read this far and don't know what hard sauce is, let me know and I'll provide that recipe to you! Jennifer Bohnhoff lives in the mountains east of Albuquerque, New Mexico. She is the author of books for middle grade through adult readers, and she wishes each and every one of you wes hál this holiday season.

Published on November 30, 2023 16:49

November 22, 2023

Remembering WWI, and Forgetting New Mexico

Most years I pick up a book or movie to read to commemorate Veteran's Day. This year, my choice was To Conquer Hell, by Edward G. Lengel.

It seems most Americans don't understand what Veterans Day is and what other commemoration it grew out of. In the United States, Veteran's Day is observed every year on November 11. Its purpose is to honor military veterans of the United States Armed Forces. Prior to 1954, the day was called Armistice Day, and recognized the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month in 1918, when the Armistice with Germany went into effect., ending major hostilities during World War I. In South Africa, the day is called Poppy Day. In Britain, France, Belgium and Poland.it is called Remembrance Day. Ernest Wrentmore Lengel's book deals with the American Expeditionary Force's role in the Meuse-Argonne offensive which came at the end of the war. The book sometimes focuses on specific soldiers, including famous ones like Alvin York and Charles Whittlesey, and lesser known ones like Ernest Wrentmore, who joined up when only 12 years old and went on to serve in WWII and Korea. .

Ernest Wrentmore Lengel's book deals with the American Expeditionary Force's role in the Meuse-Argonne offensive which came at the end of the war. The book sometimes focuses on specific soldiers, including famous ones like Alvin York and Charles Whittlesey, and lesser known ones like Ernest Wrentmore, who joined up when only 12 years old and went on to serve in WWII and Korea. .

Pattonn in front of one of his tanks. I found some of Lengel's writing quite informative and amusing. For instance, he calls George Patton "wealthy, athletic, and brilliantly insane." When explaining Patton's work establishing the First Army Tank School at Langres, France, he includes the interesting fact that there were no lights in Renault tanks, so crews had to operate in the dark when the hatches were closed. "A tank commander signaled the driver with a series of kicks: one in the back told him to go forward, a kick on the right or left shoulder meant he should turn, and a kick in the head signaled him to stop. Repeated kicks in the head meant he should turn back."

Pattonn in front of one of his tanks. I found some of Lengel's writing quite informative and amusing. For instance, he calls George Patton "wealthy, athletic, and brilliantly insane." When explaining Patton's work establishing the First Army Tank School at Langres, France, he includes the interesting fact that there were no lights in Renault tanks, so crews had to operate in the dark when the hatches were closed. "A tank commander signaled the driver with a series of kicks: one in the back told him to go forward, a kick on the right or left shoulder meant he should turn, and a kick in the head signaled him to stop. Repeated kicks in the head meant he should turn back."

For me, a New Mexican, Lengel's book was a bit of a disappointment. New Mexico hadn't been a state very long when World War I broke out, and it was a very sparsely populated place, with only 345,000 inhabitants. Despite that, more than 17,000 men stepped up to serve. All 33 counties were represented. Tiny as we were, New Mexico was ranked fifth in the nation for military service by the end of the first World War.

Men leaving for military training camp in 1917 parade on Palace Avenue near Sena Plaza. Courtesy Palace of the Governors Photo Archive, Negative No. 149995

Men leaving for military training camp in 1917 parade on Palace Avenue near Sena Plaza. Courtesy Palace of the Governors Photo Archive, Negative No. 149995

Of especial note was Roswell's Battery A, 1st New Mexico Field Artillery. Renamed Battery A, 146th Field Artillery Brigade of the 41st Infantry Division when the National Guard was "federalized" and mixed into the regular army, this devision had served Pershing well in Mexico during the Punitive Expedition against Pancho Villa. In France, they fought at Chateau-Theirry, St. Mihiel and in the Argonne Forest. The unit's four guns fired more than 14,000 rounds in combat, surpassing all other U.S. heavy artillery units. So why wouldn't Lengel mention them?

Of especial note was Roswell's Battery A, 1st New Mexico Field Artillery. Renamed Battery A, 146th Field Artillery Brigade of the 41st Infantry Division when the National Guard was "federalized" and mixed into the regular army, this devision had served Pershing well in Mexico during the Punitive Expedition against Pancho Villa. In France, they fought at Chateau-Theirry, St. Mihiel and in the Argonne Forest. The unit's four guns fired more than 14,000 rounds in combat, surpassing all other U.S. heavy artillery units. So why wouldn't Lengel mention them?

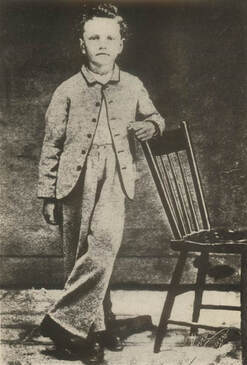

I cringed when Lengel said that Douglas MacArthur grew up at Fort Selden, Texas; Fort Selden is in New Mexico, just north of Las Cruces. A picture of the MacArthur family that hangs in the Ft. Selden visitor center. The future general is the child on the left. While To Conquer Hell certainly encompasses the full span of operations by the American Expeditionary Force, I found it difficult to read in parts. I wish the narrative had referenced the maps that are strewn throughout the book, so that I could have found the right map to go with each engagement.

A picture of the MacArthur family that hangs in the Ft. Selden visitor center. The future general is the child on the left. While To Conquer Hell certainly encompasses the full span of operations by the American Expeditionary Force, I found it difficult to read in parts. I wish the narrative had referenced the maps that are strewn throughout the book, so that I could have found the right map to go with each engagement.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a native New Mexican, and proud of it. A former history teacher, she now writes full time from her home in the remote mountains of central New Mexico. Her novel, A Blaze of Poppies, is set in the southern part of the state and in France in the years just before and during America's involvement in World War I. .

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a native New Mexican, and proud of it. A former history teacher, she now writes full time from her home in the remote mountains of central New Mexico. Her novel, A Blaze of Poppies, is set in the southern part of the state and in France in the years just before and during America's involvement in World War I. .

It seems most Americans don't understand what Veterans Day is and what other commemoration it grew out of. In the United States, Veteran's Day is observed every year on November 11. Its purpose is to honor military veterans of the United States Armed Forces. Prior to 1954, the day was called Armistice Day, and recognized the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month in 1918, when the Armistice with Germany went into effect., ending major hostilities during World War I. In South Africa, the day is called Poppy Day. In Britain, France, Belgium and Poland.it is called Remembrance Day.

Ernest Wrentmore Lengel's book deals with the American Expeditionary Force's role in the Meuse-Argonne offensive which came at the end of the war. The book sometimes focuses on specific soldiers, including famous ones like Alvin York and Charles Whittlesey, and lesser known ones like Ernest Wrentmore, who joined up when only 12 years old and went on to serve in WWII and Korea. .

Ernest Wrentmore Lengel's book deals with the American Expeditionary Force's role in the Meuse-Argonne offensive which came at the end of the war. The book sometimes focuses on specific soldiers, including famous ones like Alvin York and Charles Whittlesey, and lesser known ones like Ernest Wrentmore, who joined up when only 12 years old and went on to serve in WWII and Korea. .

Pattonn in front of one of his tanks. I found some of Lengel's writing quite informative and amusing. For instance, he calls George Patton "wealthy, athletic, and brilliantly insane." When explaining Patton's work establishing the First Army Tank School at Langres, France, he includes the interesting fact that there were no lights in Renault tanks, so crews had to operate in the dark when the hatches were closed. "A tank commander signaled the driver with a series of kicks: one in the back told him to go forward, a kick on the right or left shoulder meant he should turn, and a kick in the head signaled him to stop. Repeated kicks in the head meant he should turn back."

Pattonn in front of one of his tanks. I found some of Lengel's writing quite informative and amusing. For instance, he calls George Patton "wealthy, athletic, and brilliantly insane." When explaining Patton's work establishing the First Army Tank School at Langres, France, he includes the interesting fact that there were no lights in Renault tanks, so crews had to operate in the dark when the hatches were closed. "A tank commander signaled the driver with a series of kicks: one in the back told him to go forward, a kick on the right or left shoulder meant he should turn, and a kick in the head signaled him to stop. Repeated kicks in the head meant he should turn back." For me, a New Mexican, Lengel's book was a bit of a disappointment. New Mexico hadn't been a state very long when World War I broke out, and it was a very sparsely populated place, with only 345,000 inhabitants. Despite that, more than 17,000 men stepped up to serve. All 33 counties were represented. Tiny as we were, New Mexico was ranked fifth in the nation for military service by the end of the first World War.

Men leaving for military training camp in 1917 parade on Palace Avenue near Sena Plaza. Courtesy Palace of the Governors Photo Archive, Negative No. 149995

Men leaving for military training camp in 1917 parade on Palace Avenue near Sena Plaza. Courtesy Palace of the Governors Photo Archive, Negative No. 149995

Of especial note was Roswell's Battery A, 1st New Mexico Field Artillery. Renamed Battery A, 146th Field Artillery Brigade of the 41st Infantry Division when the National Guard was "federalized" and mixed into the regular army, this devision had served Pershing well in Mexico during the Punitive Expedition against Pancho Villa. In France, they fought at Chateau-Theirry, St. Mihiel and in the Argonne Forest. The unit's four guns fired more than 14,000 rounds in combat, surpassing all other U.S. heavy artillery units. So why wouldn't Lengel mention them?

Of especial note was Roswell's Battery A, 1st New Mexico Field Artillery. Renamed Battery A, 146th Field Artillery Brigade of the 41st Infantry Division when the National Guard was "federalized" and mixed into the regular army, this devision had served Pershing well in Mexico during the Punitive Expedition against Pancho Villa. In France, they fought at Chateau-Theirry, St. Mihiel and in the Argonne Forest. The unit's four guns fired more than 14,000 rounds in combat, surpassing all other U.S. heavy artillery units. So why wouldn't Lengel mention them?I cringed when Lengel said that Douglas MacArthur grew up at Fort Selden, Texas; Fort Selden is in New Mexico, just north of Las Cruces.

A picture of the MacArthur family that hangs in the Ft. Selden visitor center. The future general is the child on the left. While To Conquer Hell certainly encompasses the full span of operations by the American Expeditionary Force, I found it difficult to read in parts. I wish the narrative had referenced the maps that are strewn throughout the book, so that I could have found the right map to go with each engagement.

A picture of the MacArthur family that hangs in the Ft. Selden visitor center. The future general is the child on the left. While To Conquer Hell certainly encompasses the full span of operations by the American Expeditionary Force, I found it difficult to read in parts. I wish the narrative had referenced the maps that are strewn throughout the book, so that I could have found the right map to go with each engagement.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a native New Mexican, and proud of it. A former history teacher, she now writes full time from her home in the remote mountains of central New Mexico. Her novel, A Blaze of Poppies, is set in the southern part of the state and in France in the years just before and during America's involvement in World War I. .

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a native New Mexican, and proud of it. A former history teacher, she now writes full time from her home in the remote mountains of central New Mexico. Her novel, A Blaze of Poppies, is set in the southern part of the state and in France in the years just before and during America's involvement in World War I. .

Published on November 22, 2023 23:00

November 15, 2023

Entering a New World

See the strange, circular cluster of leaves at the bend in the road? This ring of green at the top of the trees is something I pass every time I leave home. I've been looking at it for at least six years, maybe longer because I don't remember when I first saw it.

See the strange, circular cluster of leaves at the bend in the road? This ring of green at the top of the trees is something I pass every time I leave home. I've been looking at it for at least six years, maybe longer because I don't remember when I first saw it. I do remember wondering what it was and why it was there. In my imagination, it became the sky ring, a portal between realms, and that became the seed of a story.

I'm now writing the first draft of that story as my NaNoWriMo 2023 project.

NaNoWriMo is short for National Novel Writing Month, and that month is November! Every November, hundreds of thousands of people gather online, in libraries and coffee shops throughout the world, and attempt to write a novel in one month. A novel, by NaNo's definition, is 50,000 words. They don't have to be great words, or even in the best order. NaNo is a matter of quantity, not quality. It is a mad dash to write a first draft. After that, the NaNo people have other months set aside devoted to editing and polishing those 50,000 frenetic words into a finished manuscript. My story is tentatively named The Raven Queen, and it is a fantasy based very loosely on the history of my neighborhood, a small, isolated community at the base of the Sandia Mountains. The community, called La Madera, thrived from the 1840s to the 1880s as a timber town. Madera is Spanish for lumber, and I've been told that many of the vigas, or roofbeams, in Albuquerque's Old Town came from La Madera. Once Anglos began coming into the area in large numbers, brick and mortar structures began to replace traditional adobe ones, and La Madera became a source of limestone, which is used in making grout. The town is no longer: a few buildings and ruins are all that are left of it. Although many factors came together to doom La Madera, one crucial one was a diminished water supply.

NaNoWriMo is short for National Novel Writing Month, and that month is November! Every November, hundreds of thousands of people gather online, in libraries and coffee shops throughout the world, and attempt to write a novel in one month. A novel, by NaNo's definition, is 50,000 words. They don't have to be great words, or even in the best order. NaNo is a matter of quantity, not quality. It is a mad dash to write a first draft. After that, the NaNo people have other months set aside devoted to editing and polishing those 50,000 frenetic words into a finished manuscript. My story is tentatively named The Raven Queen, and it is a fantasy based very loosely on the history of my neighborhood, a small, isolated community at the base of the Sandia Mountains. The community, called La Madera, thrived from the 1840s to the 1880s as a timber town. Madera is Spanish for lumber, and I've been told that many of the vigas, or roofbeams, in Albuquerque's Old Town came from La Madera. Once Anglos began coming into the area in large numbers, brick and mortar structures began to replace traditional adobe ones, and La Madera became a source of limestone, which is used in making grout. The town is no longer: a few buildings and ruins are all that are left of it. Although many factors came together to doom La Madera, one crucial one was a diminished water supply.

In my story, Savio is a young man who must find out why the stream that is the lifeblood of Lumbra, the town that I based on my old village of La Madera. And since this is fantasy, not historical fiction, the reason is fantastic indeed.

In my story, Savio is a young man who must find out why the stream that is the lifeblood of Lumbra, the town that I based on my old village of La Madera. And since this is fantasy, not historical fiction, the reason is fantastic indeed. With the help of his trusty companion, a big black dog named Panther, a squirrel guide named Abert, and a raven named Corbeau, Savio must find three stones that unite earth, water, and sky and gift them to Iyara, the Weeping Woman whose tears fill Lumbra's stream.

But will Savio's gifts be enough to make the stream run again? And will I be able to create a story that holds together and makes sense? Both of those are questions that are yet to be answered. Jennifer Bohnhoff is an author who lives in the forest on the eastern side of the Sandia Mountains. She typically writes historical fiction. This is her second foray into fantasy. Her first, a silly middle grade fantasy named The Petulant Princess, remains unpublished, and should probably remain so. For more information on Jennifer and her published works, see her website here.

But will Savio's gifts be enough to make the stream run again? And will I be able to create a story that holds together and makes sense? Both of those are questions that are yet to be answered. Jennifer Bohnhoff is an author who lives in the forest on the eastern side of the Sandia Mountains. She typically writes historical fiction. This is her second foray into fantasy. Her first, a silly middle grade fantasy named The Petulant Princess, remains unpublished, and should probably remain so. For more information on Jennifer and her published works, see her website here.

Published on November 15, 2023 23:00

November 8, 2023

John Pershing: The General of the Armies

General John Joseph Pershing is the only person who has held the special rank of General of the Armies of the United States during his lifetime. (The only other people to have held this rank are George Washington, who was awarded it posthumously in 1976, and Ulysses S. Grant who received the honor in 2020.) His military career spanned several wars during the period when the United States was becoming a force to be reckoned with on the world stage. Through his many famous and talented protégés, his influence continued long after his retirement.

General John Joseph Pershing is the only person who has held the special rank of General of the Armies of the United States during his lifetime. (The only other people to have held this rank are George Washington, who was awarded it posthumously in 1976, and Ulysses S. Grant who received the honor in 2020.) His military career spanned several wars during the period when the United States was becoming a force to be reckoned with on the world stage. Through his many famous and talented protégés, his influence continued long after his retirement. John Pershing as a young boy. [The Story of General Pershing, Everett T. Tomlinson, 1919,) Pershing was born on a farm in Laclede, Missouri on September 13, 1860. His mother was a homemaker and his father, John Fletcher Pershing, owned a general store and served as Laclede’s postmaster. During the Civil War, John Fletcher worked as a sutler, a civilian merchant who accompanied an army and sold goods to soldiers, for the Union. John Joseph was the oldest of nine children, six of which survived to adulthood. Pershing's family was not wealthy. Beginning at age 14, the oldest son was expected to contribute to the family. John began working. He also began putting aside money for his education, as his family had told him that schooling was not something they could afford.

John Pershing as a young boy. [The Story of General Pershing, Everett T. Tomlinson, 1919,) Pershing was born on a farm in Laclede, Missouri on September 13, 1860. His mother was a homemaker and his father, John Fletcher Pershing, owned a general store and served as Laclede’s postmaster. During the Civil War, John Fletcher worked as a sutler, a civilian merchant who accompanied an army and sold goods to soldiers, for the Union. John Joseph was the oldest of nine children, six of which survived to adulthood. Pershing's family was not wealthy. Beginning at age 14, the oldest son was expected to contribute to the family. John began working. He also began putting aside money for his education, as his family had told him that schooling was not something they could afford.  John Pershing as a West Point cadet (Photo: public domain) Pershing studied at Kirksville Normal School (now Truman State University), where he received his teaching degree in 1880. He taught African-American schoolchildren at Prairie Mound School, but became interested in law and went back to school to become a lawyer. When he decided that he could not get as good an education as he wanted in Missouri, he applied to the Military Academy at West Point, where cadets received a high-quality education for free in exchange for military service. At West Point, his leadership skills became apparent and he found himself in many command roles. He was the class president all four years. In 1885, when President Ulysses S. Grant’s funeral train passed West Point, Pershing commanded the honor guard.

John Pershing as a West Point cadet (Photo: public domain) Pershing studied at Kirksville Normal School (now Truman State University), where he received his teaching degree in 1880. He taught African-American schoolchildren at Prairie Mound School, but became interested in law and went back to school to become a lawyer. When he decided that he could not get as good an education as he wanted in Missouri, he applied to the Military Academy at West Point, where cadets received a high-quality education for free in exchange for military service. At West Point, his leadership skills became apparent and he found himself in many command roles. He was the class president all four years. In 1885, when President Ulysses S. Grant’s funeral train passed West Point, Pershing commanded the honor guard. After graduating in 1886, Pershing was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant. He reported for duty in 6th U.S. Cavalry Regiment in New Mexico, where he participated in several Indian War campaigns, including fighting the Apaches led by Geronimo.

Next, Pershing was posted to the University of Nebraska, where he taught military science. During his four years there, Pershing earned the law degree he’d so long wished for.

In 1896, he was promoted to 1st Lieutenant and assigned to a troop of the 10th Cavalry Regiment, one of the original regiments of Buffalo Soldiers, racially segregated black units. This began Pershing’s long association with black units.

In 1897, Pershing was sent back to West Point, where his strict ways with the students made him an unpopular teacher. The students nicknamed him Black Jack. By World War I, the epithet that was supposed to be derogatory had lost its sting and become popular. It remained with him for the rest of his life.

In 1897, Pershing was sent back to West Point, where his strict ways with the students made him an unpopular teacher. The students nicknamed him Black Jack. By World War I, the epithet that was supposed to be derogatory had lost its sting and become popular. It remained with him for the rest of his life.When the Spanish-American War broke out, Pershing was again selected to command the Tenth Cavalry, this time as their quartermaster. On July 1, 1898 he led his men in the Battle of San Juan Hill alongside Theodore Roosevelt’s famous Rough Riders.

Pershing later recalled that

...the entire command moved forward as coolly as though the buzzing of bullets was the humming of bees. White regiments, black regiments, regulars and Rough Riders, representing the young manhood of the North and the South, fought shoulder to shoulder, unmindful of race or color, unmindful of whether commanded by ex-Confederate or not, and mindful of only their common duty as Americans.”

Pershing (left) with the commander of the Philippines Constabulary (right) and Moro chieftains in 1910 (Photo: Fort Huachuca Museum) After the war, Pershing was assigned to the Office of Customs and Insular Affairs, which oversaw the overseas territories the United States had taken Spain, including Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines and Guam.

Pershing (left) with the commander of the Philippines Constabulary (right) and Moro chieftains in 1910 (Photo: Fort Huachuca Museum) After the war, Pershing was assigned to the Office of Customs and Insular Affairs, which oversaw the overseas territories the United States had taken Spain, including Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines and Guam.In the Philippines, Pershing fought against both the Moros, an indigenous Muslim people who had previously fought for their independence from the Spanish, and a wider Filipino insurrection. Pershing studied Moro culture and dialects, read the Koran, and built relations with various Moro chiefs in an effort to win them over.

From 1903 to 1905, Pershing, now a Captain, attended the War College. After his graduation, he was given a diplomatic posting as military attaché to Tokyo, where he was an official observer in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05.

From 1903 to 1905, Pershing, now a Captain, attended the War College. After his graduation, he was given a diplomatic posting as military attaché to Tokyo, where he was an official observer in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05.

He met and married Helen Frances Warren, the daughter of Francis E. Warren, a powerful Republican Senator from Wyoming. They had four children: Helen, Ann, Warren, and Margaret. Pershing took his family with him when he returned to the Philippines for a few years, then later posted to San Francisco.

In 1906, President Roosevelt used his prerogative to promote Pershing to brigadier general. This was a controversial move, and many suggested that Pershing’s marriage had influenced the President. At the time, promotions were handed out based on seniority rather than merit, and Pershing had bypassed three ranks and skipped over 830 officers ahead of him. However, the President had the power to appoint general staff officers, but not lower-ranking ones and he chose to do this for the man he’d learned to respect in Cuba during the Spanish-American War.

Pershing’s San Francisco home after the fire, with the arrow indicating the window through which his son was rescued (Photo: National Park Service) In 1915, personal tragedy struck when his home in San Francisco’s Presidio caught fire. Pershing’s wife and his three daughters were killed in the blaze, leaving him a widower with a five-year-old son named Warren. Pershing’s sister May took charge of the boy’s care and upbringing.

Pershing’s San Francisco home after the fire, with the arrow indicating the window through which his son was rescued (Photo: National Park Service) In 1915, personal tragedy struck when his home in San Francisco’s Presidio caught fire. Pershing’s wife and his three daughters were killed in the blaze, leaving him a widower with a five-year-old son named Warren. Pershing’s sister May took charge of the boy’s care and upbringing.  Pershing with his son Warren around the time of World War I. [Missouri Military Portraits, P1197-014515 Instead of taking time to grieve, Pershing leapt into action, leading 10,000 men on a punitive expedition into Mexico in an attempt to capture Pancho Villa, the bandit and revolutionary who had led several raids into U.S. territory, including the March 9, 1916 raid on Columbus, New Mexico. It was the first time the U.S. Army used mechanized vehicles in war. Cars, trucks, and airplanes were tested out in the deserts of Mexico and one of Pershing’s young officers, the future General George S. Patton, led the first motorized assault in U.S. military history, and killing Villa’s second-in-command. From the very start, the Punitive Expedition was doomed to failure. President Wilson, worried that a war might start, restricted the expeditions movements.

Pershing with his son Warren around the time of World War I. [Missouri Military Portraits, P1197-014515 Instead of taking time to grieve, Pershing leapt into action, leading 10,000 men on a punitive expedition into Mexico in an attempt to capture Pancho Villa, the bandit and revolutionary who had led several raids into U.S. territory, including the March 9, 1916 raid on Columbus, New Mexico. It was the first time the U.S. Army used mechanized vehicles in war. Cars, trucks, and airplanes were tested out in the deserts of Mexico and one of Pershing’s young officers, the future General George S. Patton, led the first motorized assault in U.S. military history, and killing Villa’s second-in-command. From the very start, the Punitive Expedition was doomed to failure. President Wilson, worried that a war might start, restricted the expeditions movements. Pershing described the failed mission as

“a man looking for a needle in a hay stack with an armed guard standing over the stack forbidding you to look in the hay.”

Pershing (front, right) with Pancho Villa (center) half a year before the expedition, when Villa was still a friend to America. At the far right, George Patton looks over Pershing’s shoulder (Photo: University of Texas at Austin) Soon after the Punitive Expedition returned to American soil, the United States entered World War I. President Woodrow Wilson had intended for General Frederick Funston to lead the expeditionary force into Europe. However, Funston died of a heart attack in February 1917, Pershing was selected to take his place. Again, Pershing received a promotion, this time jumping from major general to full, four-star general, skipping over the rank of lieutenant general.

Pershing (front, right) with Pancho Villa (center) half a year before the expedition, when Villa was still a friend to America. At the far right, George Patton looks over Pershing’s shoulder (Photo: University of Texas at Austin) Soon after the Punitive Expedition returned to American soil, the United States entered World War I. President Woodrow Wilson had intended for General Frederick Funston to lead the expeditionary force into Europe. However, Funston died of a heart attack in February 1917, Pershing was selected to take his place. Again, Pershing received a promotion, this time jumping from major general to full, four-star general, skipping over the rank of lieutenant general.

Pershing arriving in Europe (Photo: gwpda.org) Pershing oversaw the organization, training and supply of the professional army, the draft army, and the National Guard, but he was unwilling to command under the kind of restraints that had plagued the Punitive Expedition. Before he would take command, Pershing made sure that will would give him unprecedented authority to run the AEF. In exchange, Pershing agreed not to meddle in political or national policy issues. This included Wilson’s racial policies, which kept the army segregated. Although Pershing had proved that he was willing to lead colored soldiers in battle, he could not in Europe. Pershing, who wanted to keep American troops under American command instead of allowing them to become reinforcements in British and French units, allowed two black divisions to be transferred to French leadership so that they would be allowed to see combat.

Pershing arriving in Europe (Photo: gwpda.org) Pershing oversaw the organization, training and supply of the professional army, the draft army, and the National Guard, but he was unwilling to command under the kind of restraints that had plagued the Punitive Expedition. Before he would take command, Pershing made sure that will would give him unprecedented authority to run the AEF. In exchange, Pershing agreed not to meddle in political or national policy issues. This included Wilson’s racial policies, which kept the army segregated. Although Pershing had proved that he was willing to lead colored soldiers in battle, he could not in Europe. Pershing, who wanted to keep American troops under American command instead of allowing them to become reinforcements in British and French units, allowed two black divisions to be transferred to French leadership so that they would be allowed to see combat.  Buffalo Soldiers of the 92nd Division inspecting gas masks in France, 1918 (Photo: National Archives and Records Administration) At the end of the war, Pershing pushed the Supreme War Council, to reject German requests for an armistice, and instead occupy Germany. He argued that German people might later feel they were never “properly” defeated and war would again break out. Woodrow Wilson, anxious to finish the war before the upcoming mid-term elections, and Britain and France, tired of war, disagreed and the armistice signed. During his own tenure as President, Franklin D. Roosevelt acknowledged that Pershing had been right.

Buffalo Soldiers of the 92nd Division inspecting gas masks in France, 1918 (Photo: National Archives and Records Administration) At the end of the war, Pershing pushed the Supreme War Council, to reject German requests for an armistice, and instead occupy Germany. He argued that German people might later feel they were never “properly” defeated and war would again break out. Woodrow Wilson, anxious to finish the war before the upcoming mid-term elections, and Britain and France, tired of war, disagreed and the armistice signed. During his own tenure as President, Franklin D. Roosevelt acknowledged that Pershing had been right.

One version of the Pershing Map (Photo: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers) Pershing returned to the United States a hero. In 1919, Congress authorized President Wilson to promote him to the rank of General of the Armies of the United States, a rank that made him the second-highest paid government official after the President. It also allowed General Pershing to be on “active duty” for the rest of his life and continue to be available for assignments.

One version of the Pershing Map (Photo: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers) Pershing returned to the United States a hero. In 1919, Congress authorized President Wilson to promote him to the rank of General of the Armies of the United States, a rank that made him the second-highest paid government official after the President. It also allowed General Pershing to be on “active duty” for the rest of his life and continue to be available for assignments.

General Pershing served as Army Chief of Staff from 1921 to 1924. During this time, he created a map of a proposed national network of military and civilian highways, which became the foundation of the Interstate Highway System.

When the United States entered World War II, he served as a consultant. Many of his protégés, including George C. Marshall, Dwight Eisenhower, Omar Bradley, Leslie McNair, Douglas MacArthur and George S. Patton led troops. His memoir, My Experiences in World War, won the Pulitzer Prize for history in 1932.

After suffering a stroke, John Pershing died in his sleep on July 15, 1948. His body lay in state in the rotunda of the U.S. Capitol. An estimated 300,000 people came to see his funeral procession He was buried with honors in Arlington National Cemetery, at a site known as Pershing Hill. The graves of Americans whom he commanded in Europe surround his.

After suffering a stroke, John Pershing died in his sleep on July 15, 1948. His body lay in state in the rotunda of the U.S. Capitol. An estimated 300,000 people came to see his funeral procession He was buried with honors in Arlington National Cemetery, at a site known as Pershing Hill. The graves of Americans whom he commanded in Europe surround his.

Jennifer Bohnhoff's novel A Blaze of Poppies tells the story of the Punitive Expedition and America's involvement in World War I from the point of view of two New Mexicans: a national guardsman and a female rancher. It is available in ebook and paperback through Amazon and other online booksellers.

Jennifer Bohnhoff's novel A Blaze of Poppies tells the story of the Punitive Expedition and America's involvement in World War I from the point of view of two New Mexicans: a national guardsman and a female rancher. It is available in ebook and paperback through Amazon and other online booksellers.

Published on November 08, 2023 23:00

November 1, 2023

New Mexicans in WWI: Charles M. de Bremond

Charles Marie de Bremond is an important figure in twentieth century New Mexican military history.

Charles Marie de Bremond is an important figure in twentieth century New Mexican military history. The de Bremond family was originally French, but migrated to Switzerland during the French revolution.Charles was born on the tenth of July in 1864 in the town of La Chatelaine, in the canton of Fribourgh, Switzerland. He served in the Swiss Army for eight years.

In 1891, he and his uncle, Henry Gaullier, immigrated to the US. Three years later they bought 280 acres of ranch land northeast of Roswell, New Mexico and started a successful sheep operation.

de Bremond was civic minded. He participated in Roswell's cultural and social activities and served as a Captain in New Mexico's National Guard.

Photo taken during the Punitive Expedition into Mexico. de Bremond is the man in the center. On March 9, 1916 Francisco “Pancho” Villa and approximately five hundred of his men raided the border town of Columbus, New Mexico. In response, President Woodrow Wilson ordered John J. “Black Jack” Pershing to lead American troops into Mexico. de Bremond's outfit,

Photo taken during the Punitive Expedition into Mexico. de Bremond is the man in the center. On March 9, 1916 Francisco “Pancho” Villa and approximately five hundred of his men raided the border town of Columbus, New Mexico. In response, President Woodrow Wilson ordered John J. “Black Jack” Pershing to lead American troops into Mexico. de Bremond's outfit, Battery “A,” First New Mexico Field Artillery, was one of the first to respond. After being ordered to Fort Bliss, Texas for training, Battery A was attached to the Sixth U.S. Field Artillery. Approximately 5,000 U.S. troops spent nearly a year in Mexico in what turned out to be an unsuccessful attempt to capture Villa. When the Expedition ended, the battery, which had received many accolades, was mustered out of federal service and returned to Roswell.

The Mexican Punitive Expedition served as a training ground and prelude to World War I. When the U.S. entered WWI on April 2, 1917, many of the men who participated in in campaign in Mexico, including the men of New Mexico Battery A, went almost immediately to serve in World War I. Although many of its men had already entered service, the remainder of the battery was called up in December of 1917. They were again nationalized, this time joining the 146th Field Artillery.

The Mexican Punitive Expedition served as a training ground and prelude to World War I. When the U.S. entered WWI on April 2, 1917, many of the men who participated in in campaign in Mexico, including the men of New Mexico Battery A, went almost immediately to serve in World War I. Although many of its men had already entered service, the remainder of the battery was called up in December of 1917. They were again nationalized, this time joining the 146th Field Artillery.de Bremond taught many of his men to speak French, which came in very handy during their deployment.

The training Battery A received while attached to the Sixth U.S. Field Artillery proved invaluable, and Battery “A” became one of the best known American Expeditionary Force units of WWI.

The action for which New Mexico’s Battery A, 146 Field Artillery received the most praise was the destruction of a bridge at Chateau-Thierry. This bridge had served as the German’s main line of communication, and its destruction contributed to the failure of the last great German offensive of the war.

The action for which New Mexico’s Battery A, 146 Field Artillery received the most praise was the destruction of a bridge at Chateau-Thierry. This bridge had served as the German’s main line of communication, and its destruction contributed to the failure of the last great German offensive of the war.In the course of the war, de Bremond was promoted three times, rising from Captain to Colonel. By the time the war ended on November 11, 1918, the battery's four guns had each fired over 14,000 rounds. This was more rounds fired in combat than all the other American heavy mobile field Artillery combined. None of the men in the battery died during the war, but 12 were wounded. For some, including de Bremond, their wounds proved fatal.

The men of the Battery earned six battle stars for their victory medals and their commander, Lt. Colonel Charles M. DeBremond, received the Distinguished Service Medal posthumously.

de Bremond inhaled poison gas during the battle of the Marne in July 1918. He was evacuated to the states, where he gave lectures on the war to help boost civilian morale and support. He also worked on the creation of the Veterans of Foreign War. He died of pulmonary tuberculosis, a direct result of the gas attack, on December 7, 1919 in Roswell, New Mexico. He was 55 years old. His funeral was one of the biggest events Roswell had ever seen. The deBremond National Guard Facility, located at the Roswell Industrial Air Center, was named in his honor.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is an educator and author who lives in the mountains of central New Mexico. Her novel A Blaze of Poppies, tells the story of a New Mexico couple whose lives are affected by World War I.

Published on November 01, 2023 23:00

October 29, 2023