Jennifer Bohnhoff's Blog, page 9

May 29, 2024

New Mexico, the Famished Country

At the beginning of the Civil War, Henry Hopkins Sibley had a grandiose plan. Because he'd been stationed at Fernando de Taos and at Fort Union, he thought he knew the territory of New Mexico. But he didn't know it well enough, and his grandiose plan failed. He later blamed his failure not on his incompetence or lack of knowledge, but on the land itself.

At the beginning of the Civil War, Henry Hopkins Sibley had a grandiose plan. Because he'd been stationed at Fernando de Taos and at Fort Union, he thought he knew the territory of New Mexico. But he didn't know it well enough, and his grandiose plan failed. He later blamed his failure not on his incompetence or lack of knowledge, but on the land itself.

When the Civil War broke out, Sibley was serving under the commander of the department, Colonel William W. Loring, a career Army officer who'd lost an arm during the Mexican American War. Loring, whose home state was Florida, had already sent his own letter of resignation to Washington when Sibley, a Louisiana native, tendered his resignation to him an April 28th.

When the Civil War broke out, Sibley was serving under the commander of the department, Colonel William W. Loring, a career Army officer who'd lost an arm during the Mexican American War. Loring, whose home state was Florida, had already sent his own letter of resignation to Washington when Sibley, a Louisiana native, tendered his resignation to him an April 28th.Impatient to leave because of circulating rumors of high-ranking commissions in the Confederate Army, Sibley asked for “the authority to leave this Dept. immediately.”

When May 31 arrived and he still had not heard anything, he took seven days’ leave of absence, bid his command goodbye, and left Fort Union on the next stage. He accepted an appointment to colonel in the Confederate army. By June, 1861, Sibley had been promoted to brigadier general. Sibley's promotion was prompted by his visit to Richmond, Virginia, where he persuaded Confederate President Jefferson Davis that he could sweep through New Mexico and seize Colorado and California for the Confederacy.This bold plan would not only increase the size of the Confederacy, but it would achieve the dream of Manifest Destiny, making the rebel nation stretch from sea to shining sea. Gold from Colorado and California's gold fields would enrich the Southern war chest, and the deep water port of Los Angeles would help supply the army with materiel that was not getting through the Atlantic Union blockade. The proposal sounded too good to be true, especially since Sibley claimed he could do it without encumbering the Confederacy for his supplies. Sibley claimed that he could live off the land during his trek through New Mexico. He believed there was enough water, fodder for the animals, and food for his men. He had heard enough New Mexicans complain about the army presence that he believed New Mexicans would willingly support a Confederate army. Sibley was wrong, both about the amount of supplies available and about the people's opinion of the Confederate army that he led.

Brig. Gen. Henry H. Sibley's supply problems began long before he entered New Mexico Territory. Sibley began assembling his small army in San Antonio late in the summer of 1861. He quickly discovered that outfitting his troops would take far longer than he had anticipated. There were few available weapons, uniforms and military supplies for his 2,500 man force, which he had named The Army of New Mexico, and so when the men finally began the trek to the territories, many did so wearing their civilian clothing and carrying whatever weapons they had brought from home. This included squirrel guns, shotguns, and ancient blunderbusses.

Brig. Gen. Henry H. Sibley's supply problems began long before he entered New Mexico Territory. Sibley began assembling his small army in San Antonio late in the summer of 1861. He quickly discovered that outfitting his troops would take far longer than he had anticipated. There were few available weapons, uniforms and military supplies for his 2,500 man force, which he had named The Army of New Mexico, and so when the men finally began the trek to the territories, many did so wearing their civilian clothing and carrying whatever weapons they had brought from home. This included squirrel guns, shotguns, and ancient blunderbusses. One of the reasons Brig. Gen. Henry H. Sibley was so wrong about New Mexico's ability to sustain his army was a matter of timing. Since outfitting and training his troops took far longer than expected, Sibley's force didn’t begin the 600-mile march across Texas until November. The landscape of West Texas provided very little grass and other forage for the Army's horses and mules, and there was so little water that Sibley's line of march spaced itself so that each regiment was a full day behind the next, allowing the springs to recover somewhat between regiments. Still, the going was rough and the army began losing hoof stock.

After the war, William Lott Davidson, a 24-year old private in Company A of the 5th Texas, recalled that “‘Chill November’s surly blast’ came down upon us as we camped upon the Nueces. There was no timber to shield us and the wind swept at us, and the boys on guard at night must have had a hard time pacing their beats on the cold frozen ground. We were tasting the bitter delights and mournful realities of a soldier’s life. We are now for the first time beginning to find out that we are engaged in no child’s play.”

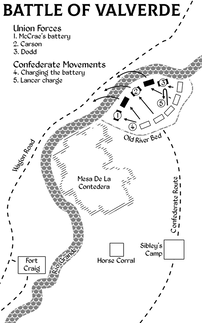

map by Matt Bohnhoff Nothing became easier after The Army of New Mexico entered New Mexico Territory. The weather at New Mexico's higher elevations was brutal. Firsthand accounts recall repeatedly waking up covered in snow. Davidson wrote that the sentries "paced in rags and tatters, their weary best through the long tedious hours of the night, with bare-feet over the frozen and ice-covered ground. ‘Found dead on post’ and ‘froze to death last night’ were sounds we often heard, as a poor, stiff, lifeless body was brought into camp, the dauntless spirit having gone to sleep, to rest with the brave.”

map by Matt Bohnhoff Nothing became easier after The Army of New Mexico entered New Mexico Territory. The weather at New Mexico's higher elevations was brutal. Firsthand accounts recall repeatedly waking up covered in snow. Davidson wrote that the sentries "paced in rags and tatters, their weary best through the long tedious hours of the night, with bare-feet over the frozen and ice-covered ground. ‘Found dead on post’ and ‘froze to death last night’ were sounds we often heard, as a poor, stiff, lifeless body was brought into camp, the dauntless spirit having gone to sleep, to rest with the brave.”Blizzards, combined with too little food and forage led to illness among both men and beast. Measles and pneumonia ran rampant through the troops.

map by Matt Bohnhoff, from Where Duty Calls After failing to take Fort Craig in a frontal assault, Sibley decided to execute what he called "a roundance on Yankeedom" and bypass the fort. This flanking march forced the Confederate Army away from the Rio Grande, the only source of water in the area. Both the men and their animals suffered intense thirst. Private Laughter of the 2nd Texas recalled that “The dry beef we had for supper needed moisture. The fact was, if one of us coughed you could see the dust fly.”

map by Matt Bohnhoff, from Where Duty Calls After failing to take Fort Craig in a frontal assault, Sibley decided to execute what he called "a roundance on Yankeedom" and bypass the fort. This flanking march forced the Confederate Army away from the Rio Grande, the only source of water in the area. Both the men and their animals suffered intense thirst. Private Laughter of the 2nd Texas recalled that “The dry beef we had for supper needed moisture. The fact was, if one of us coughed you could see the dust fly.” The old western saying that “whiskey is for drinking, but water is for fighting” proved true. The Battle of Valverde occured when the Confederate Army finally returned to the river on the other side of Contadora Mesa and found their access to water blocked by Union troops. To add to the misery, a major sandstorm, one of many recorded in soldier's diaries and memoirs, hit just before the battle of Valverde. These brutal storms were more proof that Sibley's men were campaigning in the extreme and inhospitable environment of the upper Sonoran and Chihuahuan deserts.

illustration by Ian Bristow in The Worst Enemy The Confederate's problems continued as the Army continued to head north. In Albuquerque, where they had hoped to pillage the government storehouses. They found that the Union soldiers had burned the supplies before retreating north. Running low on everything, Sibley was once again forced to split his forces in order to maximize their ability to forage on the sparse winter grass. Private Davidson was part of the army that was sent into the Sandia Mountains, where it was believed that grass was abundant. He found that what grass there was was buried beneath deep snow. "The army was marched out in the mountains east of Albuquerque and camped, as I thought, for the winter as the weather was very cold, sleeting and snowing all the time. At this camp we remained a week and we buried fifty men, and if the weather and exposure had continued much longer, we would have buried the whole brigade.”

illustration by Ian Bristow in The Worst Enemy The Confederate's problems continued as the Army continued to head north. In Albuquerque, where they had hoped to pillage the government storehouses. They found that the Union soldiers had burned the supplies before retreating north. Running low on everything, Sibley was once again forced to split his forces in order to maximize their ability to forage on the sparse winter grass. Private Davidson was part of the army that was sent into the Sandia Mountains, where it was believed that grass was abundant. He found that what grass there was was buried beneath deep snow. "The army was marched out in the mountains east of Albuquerque and camped, as I thought, for the winter as the weather was very cold, sleeting and snowing all the time. At this camp we remained a week and we buried fifty men, and if the weather and exposure had continued much longer, we would have buried the whole brigade.”The weather was no kinder in the mountains east of Santa Fe, where the Santa Fe Trail snaked through Glorieta Pass on its way to Fort Union, where the Confederate Army hoped to capture a wealth of Union supplies. The Texans won another tactical victory at the Battle of Glorieta, but returned to their supply train to find it burned. That night, Davidson wrote that “a severe snow storm arose and snow fell to the depth of a foot and several of our wounded froze to death.”

illustration by Ian Bristow in The Famished Country Weakened by two battles, long marches, extended exposure, repeated winter storms, and insufficient supplies, it became clear that the Confederate Army had no choice but to to withdraw back down the Rio Grande. With the exception of a couple of cannonade skirmishes at Albuquerque and Peralta, Colonel Canby, the cautious commander of Union forces in New Mexico was content to not engage in any more battles. Instead, he allowed the weather and terrain to finish off Sibley’s army while he skirted alongside the Rio Grande, herding the pitiful remnants of The Army of New Mexico out of the territory they'd hoped to conquer.

illustration by Ian Bristow in The Famished Country Weakened by two battles, long marches, extended exposure, repeated winter storms, and insufficient supplies, it became clear that the Confederate Army had no choice but to to withdraw back down the Rio Grande. With the exception of a couple of cannonade skirmishes at Albuquerque and Peralta, Colonel Canby, the cautious commander of Union forces in New Mexico was content to not engage in any more battles. Instead, he allowed the weather and terrain to finish off Sibley’s army while he skirted alongside the Rio Grande, herding the pitiful remnants of The Army of New Mexico out of the territory they'd hoped to conquer.

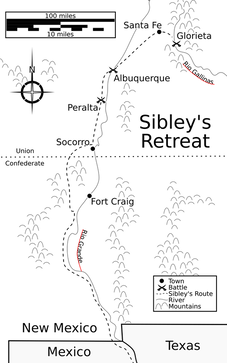

map by Matt Bohnhoff, included in The Famished Country Brig. Gen. Henry H. Sibley had launched an invasion force of 2,500 men in a grandiose scheme to take the Colorado and California goldfields, establish a port on the Pacific coast, and open a route for a coast to coast railroad system, all of which would have dramatically expanded the Confederacy’s presence in the Southwest and perhaps changed the trajectory of the war. By the time his disastrous retreat was completed in the summer of 1862, he returned to San Antonio with less than a third of the men he had begun with. Davidson wrote that, “We left San Antonio eight months earlier with near three thousand men ….And now in rags and tatters, foot-sore and weary, we again march, if a reel and stagger can be called a march, along the streets of San Antonio with fourteen hundred men. I can furnish a list of four hundred and thirty-seven dead, but where are the other sixteen hundred?” While not all the the unrecorded can be accounted for, many deserted on the long retreat, heading for California or hiding in the hills.

map by Matt Bohnhoff, included in The Famished Country Brig. Gen. Henry H. Sibley had launched an invasion force of 2,500 men in a grandiose scheme to take the Colorado and California goldfields, establish a port on the Pacific coast, and open a route for a coast to coast railroad system, all of which would have dramatically expanded the Confederacy’s presence in the Southwest and perhaps changed the trajectory of the war. By the time his disastrous retreat was completed in the summer of 1862, he returned to San Antonio with less than a third of the men he had begun with. Davidson wrote that, “We left San Antonio eight months earlier with near three thousand men ….And now in rags and tatters, foot-sore and weary, we again march, if a reel and stagger can be called a march, along the streets of San Antonio with fourteen hundred men. I can furnish a list of four hundred and thirty-seven dead, but where are the other sixteen hundred?” While not all the the unrecorded can be accounted for, many deserted on the long retreat, heading for California or hiding in the hills.In a letter to John McRae, the father of Alexander McRae, a native South Carolinian who fought for the Union, General Sibley blamed the countryside itself for his retreat.

“You will naturally speculate uponSibley's New Mexico Campaign was small in comparison to the battles waged in the east. But on a percentage basis, it was one of the most devastating campaigns any Civil War army suffered through without surrendering. That outcome is even more dramatic when we consider the fact that each of the engagements was a tactical victory for the Confederate forces. Ultimately, Sibley was driven back, far short of his ambitious goals, by the sparsely populated territory's brutal terrain and unforgiving distances. It was, indeed, the famished country that beat him.

the causes of my precipitate evacuation

of the Territory of New Mexico

after it had been virtually conquered.

My dear Sir, we beat the enemy

whenever we encountered him.

The famished country beat us.”

The Famished Country, a phrase taken from Major Sibley's letter to John McRae, is the title of Book 3 of Rebels Along the Rio Grande, a trilogy of historical fiction novels for middle grade through adult readers. Published by Kinkajou Press, a division of Artemesia Publishing, The Famished Country will be available in October, 2024.

The Famished Country, a phrase taken from Major Sibley's letter to John McRae, is the title of Book 3 of Rebels Along the Rio Grande, a trilogy of historical fiction novels for middle grade through adult readers. Published by Kinkajou Press, a division of Artemesia Publishing, The Famished Country will be available in October, 2024.

Published on May 29, 2024 23:00

May 23, 2024

Recovering the Identity of Lost Soldiers

Photo credit: author. Taken inside the American Cemetery new Belleau Woods. When I visited American World War I cemeteries in Europe in 2019, one of the most sobering things to see were the graves to unmarked soldiers. Historically, most soldiers who died in battle were never identified. The Graves Registration Service, called Mortuary Affairs" since 1991, has changed that. This organization is charged with making sure that fallen American soldiers are identified and are laid to rest in proper burial places.

Photo credit: author. Taken inside the American Cemetery new Belleau Woods. When I visited American World War I cemeteries in Europe in 2019, one of the most sobering things to see were the graves to unmarked soldiers. Historically, most soldiers who died in battle were never identified. The Graves Registration Service, called Mortuary Affairs" since 1991, has changed that. This organization is charged with making sure that fallen American soldiers are identified and are laid to rest in proper burial places.From ancient times, rank-and-file soldiers were usually stripped of arms and armor and left on the battlefield for human and animal scavengers. In later centuries, a swift burial near the place of death became the norm. Only in the case of the famous or the high ranking was an effort made to identify the deceased. In remote American frontier outposts, quartermasters buried dead soldiers, often without a coffin since wood was in short supply. They marked the graves with whatever they had on hand, and entered the death into the records. Forts moved, grave markers fell down or rotted away, and the location of the graves were lost to time.

Things hadn’t changed much by the time the United States invaded Mexico during the 1846-47 Mexican-American War. When the U.S. government wanted to build a monument to the men who died in the Battle of Buena Vista, they could not find where General Zachary Taylor, who later became our 12th President, had buried his fallen men because he did not mark the location on the map in his report.

Things hadn’t changed much by the time the United States invaded Mexico during the 1846-47 Mexican-American War. When the U.S. government wanted to build a monument to the men who died in the Battle of Buena Vista, they could not find where General Zachary Taylor, who later became our 12th President, had buried his fallen men because he did not mark the location on the map in his report.  During the American Civil War, soldiers themselves began to take their identification should they die in battle into their own hands. Although there was no officially mandated form of identification, soldiers often pinned paper slips on their coats with their name and address. Others bought commercially made badges with their name and unit engraved. When the Union Army of the Potomac crossed the Rapidan River and entered Virginia on May 4, 1864, they were appalled to find the bones of their former comrades, lost a year earlier, lying unattended on the ground. Many soldiers examined the remains for markings on clothing or equipment, the nature of the fatal wound, and dental peculiarities such as missing teeth in an attempt to identify the fallen. This approach became the centerpiece of 20th century identification methods. Once done, the men buried the deceased before moving on.

During the American Civil War, soldiers themselves began to take their identification should they die in battle into their own hands. Although there was no officially mandated form of identification, soldiers often pinned paper slips on their coats with their name and address. Others bought commercially made badges with their name and unit engraved. When the Union Army of the Potomac crossed the Rapidan River and entered Virginia on May 4, 1864, they were appalled to find the bones of their former comrades, lost a year earlier, lying unattended on the ground. Many soldiers examined the remains for markings on clothing or equipment, the nature of the fatal wound, and dental peculiarities such as missing teeth in an attempt to identify the fallen. This approach became the centerpiece of 20th century identification methods. Once done, the men buried the deceased before moving on.

Captain James M. Moore of the Quartermaster Cemeterial Division personally led a group of his men to the field after the Battle of Fort Stevens outside Washington, D.C. They searched for and recovered both remains and personal items, identifying every single Union soldier lost in that battle. This effort helped establish the Quartermaster Corps as the entity in charge of caring for the fallen.

By war’s end, Congress had authorized a national cemetery system and the remains of Union soldiers were disinterred and reburied at them. One of those cemeteries was created through the efforts of John P. Slough, the Union Commander at the Battle of Glorieta Pass. After the war he returned to New Mexico to serve as the territory’s Chief Justice and during that time he helped create the Veteran’s cemetery in Santa Fe to inter the Union soldiers who had died while serving under him. Later, Confederate soldiers were reinterred there as well. Nation wide, some 300,000 dead soldiers were moved from their temporary graves to the newly established national cemeteries.

By war’s end, Congress had authorized a national cemetery system and the remains of Union soldiers were disinterred and reburied at them. One of those cemeteries was created through the efforts of John P. Slough, the Union Commander at the Battle of Glorieta Pass. After the war he returned to New Mexico to serve as the territory’s Chief Justice and during that time he helped create the Veteran’s cemetery in Santa Fe to inter the Union soldiers who had died while serving under him. Later, Confederate soldiers were reinterred there as well. Nation wide, some 300,000 dead soldiers were moved from their temporary graves to the newly established national cemeteries.During the Spanish-American War, the U.S. became the first country to institute the policy that soldiers killed abroad should be returned to their next-of-kin. In the Philippines, Chaplain Charles C. Pierce established the QM Office of Identification and started developing what have become the modern identification techniques. He collected information such as place of death, the nature of the wounds, and the physical characteristics of the deceased soldiers, resulting in unprecedented accuracy even with bodies weeks or months old. He also suggested that a soldier's combat field kit should contain an "identity disk," the forerunner of the "dog tag" that American soldiers began wearing in 1917, when America entered World War I.

General John (Black Jack) Pershing, the leader of the American Expeditionary Force in World War I, recalled the now-retired Major Pierce into service to head the newly created Graves Registration Service (GRREG) so that the 47,000 U.S. servicemen who would die in Europe could be found, identified and returned home.

General John (Black Jack) Pershing, the leader of the American Expeditionary Force in World War I, recalled the now-retired Major Pierce into service to head the newly created Graves Registration Service (GRREG) so that the 47,000 U.S. servicemen who would die in Europe could be found, identified and returned home.Pershing noted the courage of these men in recovering the bodies of their comrades in 1918:

"(They) began their work under heavy shell of fire and gas, and, although troops were in dugouts, these men immediately went to the cemetery and in order to preserve records and locations, repaired and erected new crosses as fast as old ones were blown down. They also completed the extension to the cemetery, this work occupying a period of one and a half hours, during which time shells were falling continuously and they were subjected to mustard gas. They gathered many bodies which had been first in the hands of the Germans, and were later retaken by American counterattacks. Identification was especially difficult, all papers and tags having been removed, and most of the bodies being in a terrible condition and beyond recognition.”While some of the dead were disinterred from temporary cemeteries and returned to the U.S. after the war, 30,000 were left in permanent cemeteries in Europe. Like former President Theodore Roosevelt, who requested that his son, Quentin, be buried near the site where his plane crashed, many believed that soldiers killed overseas should remain there.

The GRREG was disbanded after World War I and had to be reactivated in World War II, when 30 GRREG companies worked in perilous conditions. Famous war correspondent Ernie Pyle reported that the men recovering the dead during the heavy fighting at Anzio frequently had to take shelter in freshly dug graves. They also had to deal with dangers such as booby-trapped bodies and snipers. When collecting bodies and taking them to temporary burial sites, the GREGG tried to use a route that avoided combat troops so the latter wouldn't have to be confronted with the death of their comrades. The grisly work resulted in some of the highest rates of PTSD in the military.

During the Korean War in 1950, the chaotic nature of the front, the mountainous terrain, and the uncertain lines of communication prevented the establishment of large cemeteries. The 108th QM Graves Registration Platoon, the only grave registration unit in Korea, sent 15 men to each of the three U.S. divisions to help in the construction of individual division cemeteries, which ended up being dug up so they wouldn't fall into enemy hands. The policy of "concurrent return, sending the fallen to the U.S. without first going into a temporary cemetery, which is still in effect today, grew out of that turmoil.

By the time of the Vietnam War, the identification of war dead had improved greatly, aided by ever-improving transportation, communication and laboratories. Only 28 American soldiers killed during the Vietnam War remained unidentified by the war's end. Using DNA analysis, the last one was identified in 1998.

May it be that no future comrade in arms will ever have to remain "known but to God."

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a former educator who writes historical fiction for middle grade readers through adults. You may read more about her and her books here, on her website.

Published on May 23, 2024 23:00

May 22, 2024

This Year's WWA Middle Grade Spur Award Winners

Western Writers of America is an organization that promotes Western literature, nonfiction, movies and music. Since 1953, it has honored the best in Western literature with the annual Spur Awards. Selected by panels of judges, awards are given for works whose inspiration, image and literary excellence best represent the reality and spirit of the American West in a number of different categories. The category of Juvenile Novel is where works for middle grade readers are represented. This year, the category awarded one winner and two finalists, that will be presented during WWA’s convention June 19-22 in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Western Writers of America is an organization that promotes Western literature, nonfiction, movies and music. Since 1953, it has honored the best in Western literature with the annual Spur Awards. Selected by panels of judges, awards are given for works whose inspiration, image and literary excellence best represent the reality and spirit of the American West in a number of different categories. The category of Juvenile Novel is where works for middle grade readers are represented. This year, the category awarded one winner and two finalists, that will be presented during WWA’s convention June 19-22 in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

There are many books about settlers on the great plains living a harsh life in a sod dugout while trying to make a new life for themselves. Think Little House on the Prairie, and you've got the idea. A Sky Full of Song is one of these books, but it covers this experience through the lens of Judaism. It is 1905, and eleven-year-old Shoshana accompanies her mother and sisters on a voyage across the Atlantic to join her father and brother in North Dakota. They are escaping the pogroms and persecutions of Ukraine, which at this point in time was part of the Russian Empire. Shoshana finds the northern plains to be beautiful and full of promise, but she comes to realize that the prejudice she had hoped to escape lies within many of the other homesteaders, and she is now culturally isolated. Desperate to fit in, she tries to hide her Jewish identity but a series of dangerous events, some human created and some natural, make her rethink this. Susan Lynn Meyer has painted a beautiful and sometimes harsh story with such hope that it brought me to tears more than once. There's no question in my mind that this novel, which won the Spur Award this year, should win multiple more awards and become a classroom classic.

There are many books about settlers on the great plains living a harsh life in a sod dugout while trying to make a new life for themselves. Think Little House on the Prairie, and you've got the idea. A Sky Full of Song is one of these books, but it covers this experience through the lens of Judaism. It is 1905, and eleven-year-old Shoshana accompanies her mother and sisters on a voyage across the Atlantic to join her father and brother in North Dakota. They are escaping the pogroms and persecutions of Ukraine, which at this point in time was part of the Russian Empire. Shoshana finds the northern plains to be beautiful and full of promise, but she comes to realize that the prejudice she had hoped to escape lies within many of the other homesteaders, and she is now culturally isolated. Desperate to fit in, she tries to hide her Jewish identity but a series of dangerous events, some human created and some natural, make her rethink this. Susan Lynn Meyer has painted a beautiful and sometimes harsh story with such hope that it brought me to tears more than once. There's no question in my mind that this novel, which won the Spur Award this year, should win multiple more awards and become a classroom classic.

What a fun romp!

What a fun romp!Christmas is coming, and when Buffalo Bill Cody needs help protecting the gifts he's bought for his special Christmas performance for a Tulsa orphanage, he calls on Marshal Tom Mix for help. Despite his best efforts, Mix gets buffaloed and the presents disappear. Can Cody and Mix solve the mystery in time for the Wild West Show to go on? This is a madcap adventure with lots of well delineated characters and the kind of twists and turns that will remind the reader of the fun, old time B grade movies of the 40s and 50s and of dime store western novels. I laughed out loud at the sometimes snarky dialog and the clever turns of phrase. My only concern: for a book targeting younger readers, there's a whole lot of drinking and cussing that might offend some modern sensibilities. This is book #9 in a series that intends to follow the whole career of Tom Mix from young cowboy to Hollywood superstar. It was a finalist for the Spur Award this year.

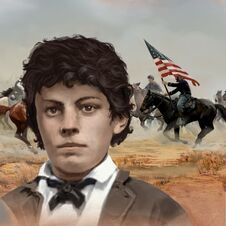

Two boys. One battle. A life-changing encounter.

Two boys. One battle. A life-changing encounter.Jemmy Martin left his Texas farm and followed Confederate General Sibley's Army into New Mexico to keep his mules safe. Now after the Battle of Valverde he's protecting Willie, an orphaned drummer boy with a broken arm. Cian Lochlann is an Irish orphan who gave up gold prospecting to join the Union Army. All he wants is a full belly and a strong man to lead him into an unknown future. Both are pulled toward a distant mountain pass in New Mexico territory where the decisive battle of Gen. Sibley's New Mexico campaign will be fought. Called the "Gettysburg of the West" the Battle of Glorieta Pass will test both boys as they face their worst enemy. The Worst Enemy. Book 2 in Rebels Along the Rio Grande, a trilogy of historical fiction novels set in New Mexico during the Civil War, was a finalist for the Spur Award this year.

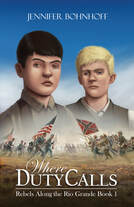

Book 1, Where Duty Calls, was a finalist last year. In it, Jemmy first leaves Texas and encounters Raul Atencio. The nephew of a prosperous Socorro, New Mexico merchant, Raul wants to become rich and powerful like his uncle. While at Fort Craig to deliver supplies and help build defenses, the Confederates arrive, and Raul becomes an unwilling participant in the defense of the Fort.

Book 1, Where Duty Calls, was a finalist last year. In it, Jemmy first leaves Texas and encounters Raul Atencio. The nephew of a prosperous Socorro, New Mexico merchant, Raul wants to become rich and powerful like his uncle. While at Fort Craig to deliver supplies and help build defenses, the Confederates arrive, and Raul becomes an unwilling participant in the defense of the Fort.Upon the banks of the Rio Grande the two armies face off in the Battle of Valverde, and both Jemmy and Raul must struggle to keep themselves, and their dreams, alive.

I have a signed copy of each of these four books that I'd love to give away to eager readers. In the comments below, tell me which one you'd like to read and why, and I will choose a winner for each.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is the author of a dozen titles for middle grade and adult readers. Book three of Rebels Along the Rio Grande, her series of middle school novels set in New Mexico during the Civil War, is titled The Famished Country and will be released by Kinkajou Press, a division of Artemesia Publishing, in October 2024.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is the author of a dozen titles for middle grade and adult readers. Book three of Rebels Along the Rio Grande, her series of middle school novels set in New Mexico during the Civil War, is titled The Famished Country and will be released by Kinkajou Press, a division of Artemesia Publishing, in October 2024.

Published on May 22, 2024 03:06

May 15, 2024

Saying Goodbye to Old Friends

This fall, I'm going to say goodbye to some old friends. I'm already feeling a little blue about it.

This fall, I'm going to say goodbye to some old friends. I'm already feeling a little blue about it. I first met Jemmy Martin back in 2015. I was teaching New Mexico history to 7th graders, many of whom complained about how much they hated history. It was boring, they said: just dates and names. That's when I began thinking about writing historical fiction that would flesh out those dates and names: give them dreams and hopes and personalities. I knew the events I wanted to portray in my novel, but I couldn't find anyone who was everywhere I wanted him to be, so I created Jemmy. He is based on a number of different real people I encountered through diaries, journals, newspaper articles and rosters.

Jemmy is a farm boy from the countryside outside San Antonio, Texas. He enters New Mexico with Henry Sibley's Confederate Army of New Mexico not because he believes in the cause, but because his brother signs up himself and the family's mules to haul supplies. When the brother backs out, Jemmy feels compelled to accompany the mules and bring them safely back to the family. It is a mission that he discovers to be much more dangerous and complicated than he'd envisioned.

When he gets to New Mexico, Jemmy becomes involved in the Battle of Valverde. There, he meets Raul Atencio. Raul is another character that I developed inspired by real people. He is the nephew of a rich merchant in Socorro, New Mexico, but his father is a peon, a member of the lower class. He wants to become rich and influential like his uncle, who is supporting the Union soldiers at Fort Craig because it is lining his pocket, not because he feels any particular allegiance. Like Jemmy, Raul is not interested in the causes of the Civil War, but becomes embroiled in it nonetheless. This causes him to reconsider his place in society, and several aspects of his culture, including its relationship with Anglos and Native Americans.

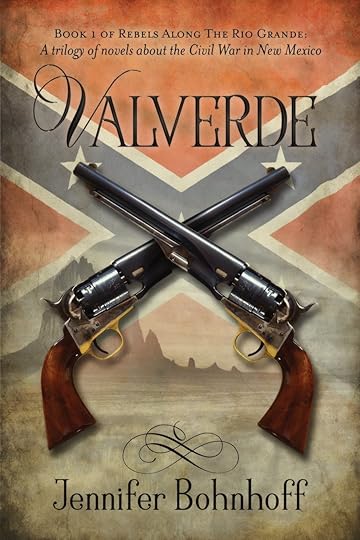

When he gets to New Mexico, Jemmy becomes involved in the Battle of Valverde. There, he meets Raul Atencio. Raul is another character that I developed inspired by real people. He is the nephew of a rich merchant in Socorro, New Mexico, but his father is a peon, a member of the lower class. He wants to become rich and influential like his uncle, who is supporting the Union soldiers at Fort Craig because it is lining his pocket, not because he feels any particular allegiance. Like Jemmy, Raul is not interested in the causes of the Civil War, but becomes embroiled in it nonetheless. This causes him to reconsider his place in society, and several aspects of his culture, including its relationship with Anglos and Native Americans.In 2017, I published the story of Jemmy and Raul's encounter at the Battle of Valverde in a middle grade novel entitled Valverde. Luckily for me, and for the story, Geoff Habiger, the publisher at Artemesia Publishing saw the potential in my book and picked it up for Kinkajou Press, his middle grade imprint. The story was republished in 2022 with a new cover, a new title, and editing that made it both a tighter and a more emotionally satisfying story.

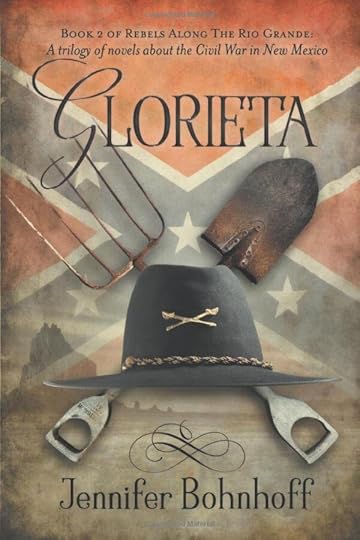

But the Battle of Valverde was not the end of the story of New Mexico during the Civil War. The Army of New Mexico continues north, and Jemmy goes with it. He passes through Socorro, Albuquerque, and finally encounters the Union Army again in Glorieta Pass, a mountainous valley southeast of Santa Fe. There he meets Cian Lachlann, an Irish boy who has joined the Union Army so that he can be fed and clothed. His greatest desire is to find a family and some place to call home. Cian's family immigrated to America to escape the Irish Potato Famine. After his mother and father died, the orphan boy travels west to mine for gold in Colorado. From there, he joins the Colorado Volunteers, who travel south to block the Confederate progress. He and Jemmy meet up on the last day of the Battle of Glorieta Pass, where the Confederates suffer a devastating loss to their supply train. The story of Jemmy and Cian's encounter at the Battle of Glorieta Pass was first published as a middle grade novel entitled Glorieta in 2020. Kinkajou Press republished the story as The Worst Enemy in 2023.

But the Battle of Valverde was not the end of the story of New Mexico during the Civil War. The Army of New Mexico continues north, and Jemmy goes with it. He passes through Socorro, Albuquerque, and finally encounters the Union Army again in Glorieta Pass, a mountainous valley southeast of Santa Fe. There he meets Cian Lachlann, an Irish boy who has joined the Union Army so that he can be fed and clothed. His greatest desire is to find a family and some place to call home. Cian's family immigrated to America to escape the Irish Potato Famine. After his mother and father died, the orphan boy travels west to mine for gold in Colorado. From there, he joins the Colorado Volunteers, who travel south to block the Confederate progress. He and Jemmy meet up on the last day of the Battle of Glorieta Pass, where the Confederates suffer a devastating loss to their supply train. The story of Jemmy and Cian's encounter at the Battle of Glorieta Pass was first published as a middle grade novel entitled Glorieta in 2020. Kinkajou Press republished the story as The Worst Enemy in 2023.

Where Duty Calls has won the CIPA EVVY AND NM-AZ Book awards and was a finalist for the Spur and the Zia. The Worst Enemy was also a Spur award finalist.

Where Duty Calls has won the CIPA EVVY AND NM-AZ Book awards and was a finalist for the Spur and the Zia. The Worst Enemy was also a Spur award finalist.

The highpoint of the story of the Civil War in New Mexico may be the Battle of Glorieta, but that is not the end of the story. The end doesn't come until the Confederate Army is out of New Mexico. That end comes in The Famished Country, the final book in my trilogy. I didn't write this book until after Geoff had picked up the first two, so there will only be one edition, whose cover I will reveal soon. In this third book, readers will learn whether Jemmy, Raul and Cian are able to fulfill their deepest wishes. Does Jemmy bring home his mules? Does Raul achieve the social standing he craves? Does Cian find a place he belongs? Or does each boy outgrow his original desire? In addition to having to say goodbye to my three boys, I'll be leaving Annabelle Watkins, the beautiful but petulant daughter of a Union Major, who stole Raul's heart, tried to steal Jemmy's and really wants to leave the uncivilized west for boarding school and a chance for a place in high society.

The highpoint of the story of the Civil War in New Mexico may be the Battle of Glorieta, but that is not the end of the story. The end doesn't come until the Confederate Army is out of New Mexico. That end comes in The Famished Country, the final book in my trilogy. I didn't write this book until after Geoff had picked up the first two, so there will only be one edition, whose cover I will reveal soon. In this third book, readers will learn whether Jemmy, Raul and Cian are able to fulfill their deepest wishes. Does Jemmy bring home his mules? Does Raul achieve the social standing he craves? Does Cian find a place he belongs? Or does each boy outgrow his original desire? In addition to having to say goodbye to my three boys, I'll be leaving Annabelle Watkins, the beautiful but petulant daughter of a Union Major, who stole Raul's heart, tried to steal Jemmy's and really wants to leave the uncivilized west for boarding school and a chance for a place in high society. I've been a little melancholy thinking about the end of the story. Even if they are not real, I feel that Annabelle, Jemmy, Raul and Cian are going to continue their lives without my watching over the process. They've become old friends in the years that I have explored their actions and personalities.

I'll also be leaving a supporting cast of real, historical people. Unlike my fictitious characters, I know the outcome of these people's lives, and I didn't have any say in those outcomes. Some, I am proud to have met. Others become people I am not proud of. If you haven't begun this story, I advise you pick up Where Duty Calls now. Read it and The Worst Enemy, so that you'll be ready when The Famished Country comes out this October.. Jennifer Bohnhoff is a former educator and the author of a dozen books for middle grade and adult readers. You can learn more about her and her books on her website.

I'll also be leaving a supporting cast of real, historical people. Unlike my fictitious characters, I know the outcome of these people's lives, and I didn't have any say in those outcomes. Some, I am proud to have met. Others become people I am not proud of. If you haven't begun this story, I advise you pick up Where Duty Calls now. Read it and The Worst Enemy, so that you'll be ready when The Famished Country comes out this October.. Jennifer Bohnhoff is a former educator and the author of a dozen books for middle grade and adult readers. You can learn more about her and her books on her website.

Published on May 15, 2024 23:00

May 8, 2024

Meg Goes to America: An Interview with Katy Hammel

One of my favorite books this spring was Meg Goes to America, by Albuquerque author Katy Hammel. The gold winner of the Douglas Preston Award for Published Fiction, this middle grade novel tells the story of Kay, a missionary's daughter who was born and raised in Japan. With the coming of WWII, it is no longer a safe place for Americans, and so her family leaves for the United States -- or that's the plan. When father is detained by Japanese officials, Meg, her younger but very wise young brother, and her mother must make the trip back to Michigan on their own. It's a harrowing trip, but not more harrowing than learning to fit into American society. This novel hit all the sweet spots for me: it is historically accurate and the author really understands how middle grade girls think. Even more enticing, it's based on the real story of the author's mother! I was so interested and charmed that I asked the author if I could interview her. Here are the responses she gave me to my questions. What inspired you to write this novel? Why do you think it's an important story to share with middle grade readers?

I wasn’t satisfied there were enough books that portray the inner life of a ‘thinky’ child who grapples with big ideas about religion and loneliness and countries and cultures. When I was growing up, I treasured the novels of Louisa May Alcott and Laura Ingalls Wilder and Madeleine L’Engle. They wrote books about America that were specific to time and place through the lens of girl protagonists. I wanted to participate in that kind of story-telling.

One of my favorite books this spring was Meg Goes to America, by Albuquerque author Katy Hammel. The gold winner of the Douglas Preston Award for Published Fiction, this middle grade novel tells the story of Kay, a missionary's daughter who was born and raised in Japan. With the coming of WWII, it is no longer a safe place for Americans, and so her family leaves for the United States -- or that's the plan. When father is detained by Japanese officials, Meg, her younger but very wise young brother, and her mother must make the trip back to Michigan on their own. It's a harrowing trip, but not more harrowing than learning to fit into American society. This novel hit all the sweet spots for me: it is historically accurate and the author really understands how middle grade girls think. Even more enticing, it's based on the real story of the author's mother! I was so interested and charmed that I asked the author if I could interview her. Here are the responses she gave me to my questions. What inspired you to write this novel? Why do you think it's an important story to share with middle grade readers?

I wasn’t satisfied there were enough books that portray the inner life of a ‘thinky’ child who grapples with big ideas about religion and loneliness and countries and cultures. When I was growing up, I treasured the novels of Louisa May Alcott and Laura Ingalls Wilder and Madeleine L’Engle. They wrote books about America that were specific to time and place through the lens of girl protagonists. I wanted to participate in that kind of story-telling.

Other than family history, how much research did you have to do to write Meg Goes to America? Where did you get the most help?

Katy Hammel Family history was definitely the beginning. The character of Meg is inspired by my mother and Meg Goes to America recounts their actual journey from Japan to the U.S. My mother and uncle shared memories, photos, and letters with me and my uncle explicitly gave me permission to write the story. But I had a few other aces up my sleeve. First, back in the early 80’s, I interviewed my grandfather about his experiences during the war years. He recorded the story of his incarceration for me on the cassette Dictaphone he used to prepare his sermons. I digitalized that audio recording and I still have it, so I can hear my grandfather’s actual voice with his distinctive timbre and tone whenever I want. Second, my parents became missionaries to Japan post-war and I grew up there, so the things Meg thinks and experiences in the book are actually an amalgam of my mother’s memories and my own. Third, the Presbyterian Historical Society had a portfolio about my grandparents and other records about missionaries held in Japan during World War II. Those repositories were useful.

Katy Hammel Family history was definitely the beginning. The character of Meg is inspired by my mother and Meg Goes to America recounts their actual journey from Japan to the U.S. My mother and uncle shared memories, photos, and letters with me and my uncle explicitly gave me permission to write the story. But I had a few other aces up my sleeve. First, back in the early 80’s, I interviewed my grandfather about his experiences during the war years. He recorded the story of his incarceration for me on the cassette Dictaphone he used to prepare his sermons. I digitalized that audio recording and I still have it, so I can hear my grandfather’s actual voice with his distinctive timbre and tone whenever I want. Second, my parents became missionaries to Japan post-war and I grew up there, so the things Meg thinks and experiences in the book are actually an amalgam of my mother’s memories and my own. Third, the Presbyterian Historical Society had a portfolio about my grandparents and other records about missionaries held in Japan during World War II. Those repositories were useful.

Meg and The Rocks: 2023 Winner in the WILLA Literary Awards Young Adult Fiction and Nonfiction category You had to move from middle grade to young adult to write the next book in the series, Meg and the Rocks. Why did you do that?

Meg and The Rocks: 2023 Winner in the WILLA Literary Awards Young Adult Fiction and Nonfiction category You had to move from middle grade to young adult to write the next book in the series, Meg and the Rocks. Why did you do that?That was a decision I tussled with for a long time. It was very important to me that my main character of Meg be a moral decision-maker who had agency to take actions that had impact. That’s hard to pull off in a setting driven by world and family calamities outside her control. Everyone who writes historically based fiction for children faces this problem, including you! I’m thinking about books like the “I Survived” series, Titanicat by Marty Crisp, and your “Rebels Along the Rio Grande” books. There is a scene in the second book where Meg confronts an evil doer and of course, the second book gets us closer to the U.S. dropping atomic bombs on Japan. It’s mature content. What’s next?

Meg is a teenager at the close of Meg and the Rocks and the family is about to leave the Manzanar concentration camp where her father worked as a chaplain with our Japanese-American prisoners. I’m going to have the family move to Albuquerque, which is definitely not what happened IRL. Stay tuned because Meg is growing up! Click here to see more on Katy Hammel's books.

Published on May 08, 2024 23:00

April 26, 2024

Finding Fantasy Inspiration On the Internet

My first fantasy novel, Raven Quest, comes out next month. In the past few weeks, I've shared how a walk through the woods inspired me to write this story, and how I based the fantasy world in which it is set on the history of my neighborhood.

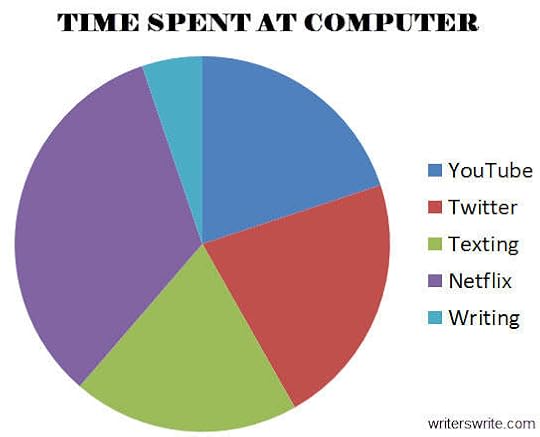

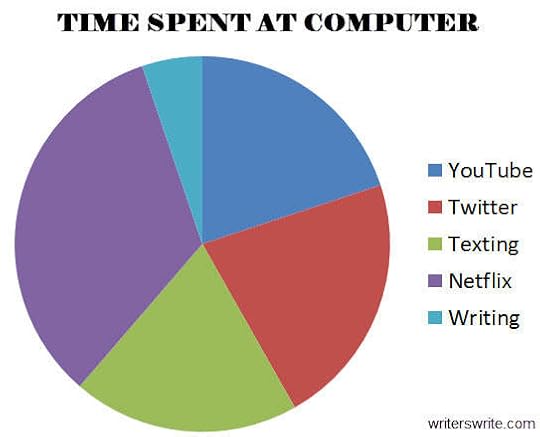

My first fantasy novel, Raven Quest, comes out next month. In the past few weeks, I've shared how a walk through the woods inspired me to write this story, and how I based the fantasy world in which it is set on the history of my neighborhood.Another source of inspiration for me was, believe it or not, social media. I know what you're thinking: writers use social media to procrastinate and avoid writing. And that's sometimes (ok, I admit it. OFTEN) the case. If you edited the chart below so that the purple area said "Facebook" instead of Netflix, you'd have

a pretty accurate measure of my time on the computer. But sometimes that wasted time pays off in new ideas and inspiration. Just one glance at my saved file on Facebook proves it!

a pretty accurate measure of my time on the computer. But sometimes that wasted time pays off in new ideas and inspiration. Just one glance at my saved file on Facebook proves it!

Take, for instance, the post on the Blue Men of Minch that I saved in February of 2023. Scottish folklore says that the blue men of the Minch, also known as storm kelpies are mythological creatures inhabiting the stretch of water between the northern Outer Hebrides and mainland Scotland. They watch for sailors to drown and stricken boats to sink. They have the power to create storms,twist and dive like porpoises, and challenge ship captains to poetry contests, sinkings the vessels of those who fail. My imagination changed these men from blue to green, and made them shape-shifting frogs.

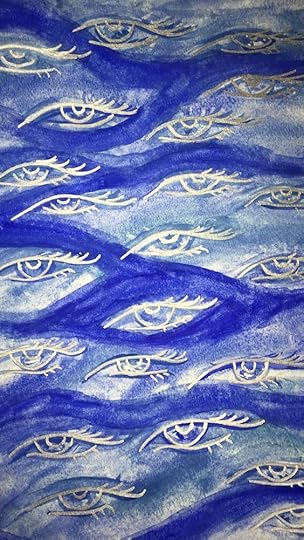

Take, for instance, the post on the Blue Men of Minch that I saved in February of 2023. Scottish folklore says that the blue men of the Minch, also known as storm kelpies are mythological creatures inhabiting the stretch of water between the northern Outer Hebrides and mainland Scotland. They watch for sailors to drown and stricken boats to sink. They have the power to create storms,twist and dive like porpoises, and challenge ship captains to poetry contests, sinkings the vessels of those who fail. My imagination changed these men from blue to green, and made them shape-shifting frogs.  Photographer Amy Kierstead posted this stunning shot of ice on the surface of a small pond. She named it "The Eye of the Forest." I call it beautiful and the inspiration for Iyara, the water woman who is the personification of all the streams in the forest outside of Lumbra. The picture below also inspired me.

Photographer Amy Kierstead posted this stunning shot of ice on the surface of a small pond. She named it "The Eye of the Forest." I call it beautiful and the inspiration for Iyara, the water woman who is the personification of all the streams in the forest outside of Lumbra. The picture below also inspired me.  So yes, I do waste a lot of time on social media, but all the while, ideas are taking shape, building bit by bit, a single pebble of inspiration that begins rolling, gains mass, and becomes an avalanche of story ideas. Raven Quest, Jennifer's first fantasy novel, is appropriate for readers in 4th grade and above. Coming out on May 20th, it is now available to preorder as an ebook. You may also buy the paperback version directly from the author and she will be happy to sign and dedicate your copy before sending it.

So yes, I do waste a lot of time on social media, but all the while, ideas are taking shape, building bit by bit, a single pebble of inspiration that begins rolling, gains mass, and becomes an avalanche of story ideas. Raven Quest, Jennifer's first fantasy novel, is appropriate for readers in 4th grade and above. Coming out on May 20th, it is now available to preorder as an ebook. You may also buy the paperback version directly from the author and she will be happy to sign and dedicate your copy before sending it.

Published on April 26, 2024 09:30

Finding Fantasy Inspiration On the Internet

Raven Quest is, at this time, my only fantasy novel. It was inspired by a walk through the woods and the story line is based on the history of my neighborhood.

Another source of inspiration for me was, believe it or not, social media. I know what you're thinking: writers use social media to procrastinate and avoid writing. And that's sometimes (ok, I admit it. OFTEN) the case. If you edited the chart below so that the purple area said "Facebook" instead of Netflix, you'd have

a pretty accurate measure of my time on the computer. But sometimes that wasted time pays off in new ideas and inspiration. Just one glance at my saved file on Facebook proves it!

Take, for instance, the post on the Blue Men of Minch that I saved in February of 2023. Scottish folklore says that the blue men of the Minch, also known as storm kelpies are mythological creatures inhabiting the stretch of water between the northern Outer Hebrides and mainland Scotland. They watch for sailors to drown and stricken boats to sink. They have the power to create storms,twist and dive like porpoises, and challenge ship captains to poetry contests, sinkings the vessels of those who fail. My imagination changed these men from blue to green, and made them shape-shifting frogs.

Take, for instance, the post on the Blue Men of Minch that I saved in February of 2023. Scottish folklore says that the blue men of the Minch, also known as storm kelpies are mythological creatures inhabiting the stretch of water between the northern Outer Hebrides and mainland Scotland. They watch for sailors to drown and stricken boats to sink. They have the power to create storms,twist and dive like porpoises, and challenge ship captains to poetry contests, sinkings the vessels of those who fail. My imagination changed these men from blue to green, and made them shape-shifting frogs. Photographer Amy Kierstead posted this stunning shot of ice on the surface of a small pond. She named it "The Eye of the Forest." I call it beautiful and the inspiration for Iyara, the water woman who is the personification of all the streams in the forest outside of Lumbra. The picture below also inspired me.

Photographer Amy Kierstead posted this stunning shot of ice on the surface of a small pond. She named it "The Eye of the Forest." I call it beautiful and the inspiration for Iyara, the water woman who is the personification of all the streams in the forest outside of Lumbra. The picture below also inspired me.

So yes, I do waste a lot of time on social media, but all the while, ideas are taking shape, building bit by bit, a single pebble of inspiration that begins rolling, gains mass, and becomes an avalanche of story ideas.Raven Quest, Jennifer's first fantasy novel, is appropriate for readers in 4th grade and above. It is available at most online booksellers or you may buy the paperback version directly from the author and she will be happy to sign and dedicate your copy before sending it.

Published on April 26, 2024 06:20

April 17, 2024

History of a Neighborhood becomes History of a Fantasy World

In my last blog I shared how a walk with my granddaughter began me on the path to writing a fantasy, and how some bent little trees, one giant old ash, and a strange wreath-like structure at the top of a tree inspired me enough to work their way into the story that became Raven Quest.

Because all of these things were close by where I lived, I began thinking of the story as taking place in my own neighborhood, which has an interesting history. That history worked its way into the very heart of the story.

The history of my area begins in 1706, when a group of Spanish colonizers founded Albuquerque not far from the banks of the Rio Grande. An alluvial fan slopes eastward to the Sandia Mountains, which were a rich source of lumber, minerals, wildlife and other resources for not only the new colonizers, but for the people who had come before the Spanish, the Puebloans who lived along the river and Apache and other nomadic tribes who moved throughout the nearby plains and mountains.

Frequent raids, especially by the Apache, caused the Spanish to establish outlying land grants that acted as buffers between Albuquerque and marauding tribes. One of the first, Cañon de Carnué, was established in the pass between the Sandia and Manzano Mountains in 1763. As the villages grew, they split, creating the new villages of Tijeras, San Antonio, Manzano, Chilili, and others, that dotted the east side of Sandia Mountain. Many of these grants were given not to individuals, but to communities of people. In these grants, while individuals might own their houses, the surrounding fields and resources were shared by everyone.

Many of the settlers of these outlying land grants were Genizaros, Native Americans who had been taken captive in battles with the Spanish or stolen from their people. Genizaro lived as servants and slaves within Spanish homes, tending sheep, gardening, performing household chores and tending to their master’s children. They learned to live in the Spanish style and wore European clothing. They adopted the Spanish surnames of their masters and gained Christian first names through baptism. While they remained ethnically Indigenous, the became culturally Spanish. Unlike African slaves in the American south, Genizaros who adapted well to Spanish customs were often freed after a term of service.

These freed Genizaros were happy to settle on land grants because, while dangerous, it offered the opportunity to own land and gain social and economic autonomy. Many of these new communities combined Spanish customs with the Native customs of their youth, creating new forms of religion, language, and social practice. These communities became tight-knit and loyal to each other but often suspicious of outsiders.

Not far from where I live is the ghost town of La Madera. Founded sometime around 1849, its settlers likely came from the Las Huertas Land Grant or from the little village of San Pedro Viejo. Because of the distance and the rugged terrain, the village had to be self sustaining. Its fields grew melons, squash, pinto beans and corn. Sheep and cows grazed in meadows watered from a spring that was just up the valley from the village. In 1860, 25 families called La Madera home.

But that doesn’t mean that La Madera had no contact with the outside world. Madera is Spanish for lumber, which seems to have been the chief source of income for the village. I’ve been told that many of the vigas, or roof trusses in houses in Albuquerque’s Old Town originated in La Madera Canyon. In addition to a church and a school La Madera had a large building that served as a dance hall, stage coach stop, and post office.

When the United States seized control during the Mexican-American War, life in New Mexico began to change, sometimes in ways that were very detrimental to these small communities. Because the American system of ownership did not recognize community-based systems, many of the old grants were denied their property and the rights of communities to the resources surrounding them. Villagers could no longer be assured access to the mountain’s forests and other resources if those slopes were sold to others.

In 1875, the village was threatened when Henry Caldwell, an immigrant from Hamburg, Germany, purchased a track of land south (up stream) from La Madera, which he used for farming and livestock, both of which used water that had always flowed down to their village. The situation became even more dire in 1880, when an organization named San Pedro and Cañon del Agua Water Company built a dam 2 miles uphill from the town. 80 feet high, 300 feet long and 20 feet thick, the dam included a 15” pipe that directed the water past La Madera to the new gold, copper, and silver mines in San Pedro. Without water, the village was doomed.

Today, La Madera church is a private home and the stagecoach stop is a ruin. Except for these two buildings and a graveyard, nothing remains of the village. However, the idea of an isolated village threatened with the loss of its water by an outside power intrigued me, and the town of La Madera transformed itself in my mind into the fictional town of Lumbra. Raven Quest if Jennifer Bohnhoff's first fantasy novel. It is due to come out on May 20, 2024.

Raven Quest if Jennifer Bohnhoff's first fantasy novel. It is due to come out on May 20, 2024.

You can preorder the ebook on Amazon for just .99. Price will go up after May 20.

You can also preorder the paperback directly from the author on her website. Purchasers will get a free bag of goodies, and book will be at a reduced price.

Because all of these things were close by where I lived, I began thinking of the story as taking place in my own neighborhood, which has an interesting history. That history worked its way into the very heart of the story.

The history of my area begins in 1706, when a group of Spanish colonizers founded Albuquerque not far from the banks of the Rio Grande. An alluvial fan slopes eastward to the Sandia Mountains, which were a rich source of lumber, minerals, wildlife and other resources for not only the new colonizers, but for the people who had come before the Spanish, the Puebloans who lived along the river and Apache and other nomadic tribes who moved throughout the nearby plains and mountains.

Frequent raids, especially by the Apache, caused the Spanish to establish outlying land grants that acted as buffers between Albuquerque and marauding tribes. One of the first, Cañon de Carnué, was established in the pass between the Sandia and Manzano Mountains in 1763. As the villages grew, they split, creating the new villages of Tijeras, San Antonio, Manzano, Chilili, and others, that dotted the east side of Sandia Mountain. Many of these grants were given not to individuals, but to communities of people. In these grants, while individuals might own their houses, the surrounding fields and resources were shared by everyone.

Many of the settlers of these outlying land grants were Genizaros, Native Americans who had been taken captive in battles with the Spanish or stolen from their people. Genizaro lived as servants and slaves within Spanish homes, tending sheep, gardening, performing household chores and tending to their master’s children. They learned to live in the Spanish style and wore European clothing. They adopted the Spanish surnames of their masters and gained Christian first names through baptism. While they remained ethnically Indigenous, the became culturally Spanish. Unlike African slaves in the American south, Genizaros who adapted well to Spanish customs were often freed after a term of service.

These freed Genizaros were happy to settle on land grants because, while dangerous, it offered the opportunity to own land and gain social and economic autonomy. Many of these new communities combined Spanish customs with the Native customs of their youth, creating new forms of religion, language, and social practice. These communities became tight-knit and loyal to each other but often suspicious of outsiders.

Not far from where I live is the ghost town of La Madera. Founded sometime around 1849, its settlers likely came from the Las Huertas Land Grant or from the little village of San Pedro Viejo. Because of the distance and the rugged terrain, the village had to be self sustaining. Its fields grew melons, squash, pinto beans and corn. Sheep and cows grazed in meadows watered from a spring that was just up the valley from the village. In 1860, 25 families called La Madera home.

But that doesn’t mean that La Madera had no contact with the outside world. Madera is Spanish for lumber, which seems to have been the chief source of income for the village. I’ve been told that many of the vigas, or roof trusses in houses in Albuquerque’s Old Town originated in La Madera Canyon. In addition to a church and a school La Madera had a large building that served as a dance hall, stage coach stop, and post office.

When the United States seized control during the Mexican-American War, life in New Mexico began to change, sometimes in ways that were very detrimental to these small communities. Because the American system of ownership did not recognize community-based systems, many of the old grants were denied their property and the rights of communities to the resources surrounding them. Villagers could no longer be assured access to the mountain’s forests and other resources if those slopes were sold to others.

In 1875, the village was threatened when Henry Caldwell, an immigrant from Hamburg, Germany, purchased a track of land south (up stream) from La Madera, which he used for farming and livestock, both of which used water that had always flowed down to their village. The situation became even more dire in 1880, when an organization named San Pedro and Cañon del Agua Water Company built a dam 2 miles uphill from the town. 80 feet high, 300 feet long and 20 feet thick, the dam included a 15” pipe that directed the water past La Madera to the new gold, copper, and silver mines in San Pedro. Without water, the village was doomed.

Today, La Madera church is a private home and the stagecoach stop is a ruin. Except for these two buildings and a graveyard, nothing remains of the village. However, the idea of an isolated village threatened with the loss of its water by an outside power intrigued me, and the town of La Madera transformed itself in my mind into the fictional town of Lumbra.

Raven Quest if Jennifer Bohnhoff's first fantasy novel. It is due to come out on May 20, 2024.

Raven Quest if Jennifer Bohnhoff's first fantasy novel. It is due to come out on May 20, 2024.You can preorder the ebook on Amazon for just .99. Price will go up after May 20.

You can also preorder the paperback directly from the author on her website. Purchasers will get a free bag of goodies, and book will be at a reduced price.

Published on April 17, 2024 03:26

April 9, 2024

Where I got the idea for Raven Quest

Next week I'll reveal the cover for Raven Quest, my first ever fantasy novel. On May 20, 2024, I’m going to release my first ever fantasy novel. It’s the story of Savio, a shepherd who lives in Lumbra. a sleepy village sitting in the shadow of majestic Pastique mountain. The bustling capital city of the old Nacixem Empire lies just on the other side of the mountain.

Next week I'll reveal the cover for Raven Quest, my first ever fantasy novel. On May 20, 2024, I’m going to release my first ever fantasy novel. It’s the story of Savio, a shepherd who lives in Lumbra. a sleepy village sitting in the shadow of majestic Pastique mountain. The bustling capital city of the old Nacixem Empire lies just on the other side of the mountain.

While the villagers have enjoyed a quiet life, living in the traditional ways of their ancestors, all is not well now. The Nacixem Empire has been conquered by the Olgna. Change is coming. One of the first changes is the drying up of the stream that supplies water to Lumbra. Only those like Savio and his grandmother, who can see into the realms beyond human reality, may be able to stop it. Savio doesn’t think he has what it takes to save the village. For starters, an old trauma stops him from taking up the cudgel, the weapon that adult men in Lumbra use for protection. He’s also unsure he can accept the strange new reality he finds himself in. Savio must put aside his doubts and fears and join forces with a raven, a squirrel, and his faithful dog to complete a quest that will make the water flow once more. In his new form, Savio finds he has powers that he never had as a human. Can he use them, and the weapon he’s been avoiding, to overcome an evil that threatens his very way of life, or will he die trying?

The cudgel the men of Lumbra carry is similar to this, but with a much larger knob on the right end. Maybe you’re wondering where I got the idea for this book. Ask anyone who knows me and you’ll discover I’ve got a pretty vivid imagination. I can see all kinds of things that aren’t there. I can imagine all sorts of scenarios. But this story definitely got its start when my granddaughter and I went on a walk soon after I moved to a new neighborhood in 2017.

The cudgel the men of Lumbra carry is similar to this, but with a much larger knob on the right end. Maybe you’re wondering where I got the idea for this book. Ask anyone who knows me and you’ll discover I’ve got a pretty vivid imagination. I can see all kinds of things that aren’t there. I can imagine all sorts of scenarios. But this story definitely got its start when my granddaughter and I went on a walk soon after I moved to a new neighborhood in 2017.  My granddaughter and the shelter she built in my woods.

My granddaughter and the shelter she built in my woods.

My dog Panzer and a fairy arch. Both made it into my novel. My new house was high up on Sandia Mountain, east of Albuquerque. It is surrounded by ponderosa pine and douglas fir forest. Soon after I’d moved in, I took my granddaughter on a little exploration of a ravine that runs through my property. We passed some small oaks that had grown tall, seeking sunshine, then given up. My granddaughter called these trees ‘fairy arches’ and warned me not to go under one. The wheels of my imagination began turning. I showed her a tree that my sons and I had found fifteen years before the house was built, when my husband and I had first bought the land on which the house finally stood. This fir is very old and has a huge trunk. My sons had dubbed it the fairy tree. A neighbor called it the family tree, because she, her husband and daughter could just touch fingertips when they stood around it. I knew I had to include that tree in my story.

My dog Panzer and a fairy arch. Both made it into my novel. My new house was high up on Sandia Mountain, east of Albuquerque. It is surrounded by ponderosa pine and douglas fir forest. Soon after I’d moved in, I took my granddaughter on a little exploration of a ravine that runs through my property. We passed some small oaks that had grown tall, seeking sunshine, then given up. My granddaughter called these trees ‘fairy arches’ and warned me not to go under one. The wheels of my imagination began turning. I showed her a tree that my sons and I had found fifteen years before the house was built, when my husband and I had first bought the land on which the house finally stood. This fir is very old and has a huge trunk. My sons had dubbed it the fairy tree. A neighbor called it the family tree, because she, her husband and daughter could just touch fingertips when they stood around it. I knew I had to include that tree in my story.

And then, one day I was driving the long and windy road toward my neighborhood. I’d traveled about a mile away from my mailbox when I noticed something very strange: a ring in the sky formed by the curving of the tops of trees. This definitely had to show up in my book!

And then, one day I was driving the long and windy road toward my neighborhood. I’d traveled about a mile away from my mailbox when I noticed something very strange: a ring in the sky formed by the curving of the tops of trees. This definitely had to show up in my book!

But the story didn’t start coming together in my mind until I learned about the history of my neighborhood. It turns out, my neighborhood once had a thriving town. Little is left, but the history is fascinating. I'll go into more detail in my next blog. Raven Quest will be available in ebook and paperback on May 20. It is now available to preorder in ebook form on Amazon for a special, introductory price of 99¢.

Published on April 09, 2024 03:12

April 3, 2024

Divided Duty

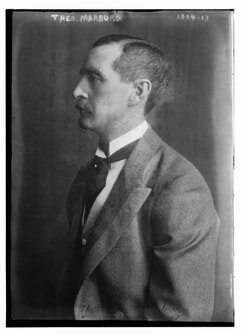

the United States Library of Congress Prints and Photographs division. digital ID 04642 Recently, one of my fans let me know that there was a poem about Alexander McRrae, the Union officer who lost his battery of artillery pieces to the Confederates at the Battle of Valverde. Given that tidbit of information, I went down a rabbit hole and discovered not only a poem, but a couple of interesting people.

the United States Library of Congress Prints and Photographs division. digital ID 04642 Recently, one of my fans let me know that there was a poem about Alexander McRrae, the Union officer who lost his battery of artillery pieces to the Confederates at the Battle of Valverde. Given that tidbit of information, I went down a rabbit hole and discovered not only a poem, but a couple of interesting people.

The poet, it turns out, is a man named Theodore Marburg. Marburg wrote a number of books. Some are poetry. Others are treatises on economics, government, the Spanish American War, and The League of Nations. He was also the United States Minister to Belgium from 1912 to 1914, the executive secretary of an organization called the League to Enforce Peace, and a prominent advocate of the League of Nations

Marburg was born in Baltimore, Maryland on July 10, 1862, which means that McRae was already dead when the poet was born. I found that interesting, and wondered what caused him to want to write a poem about someone he never knew. He died in Vancouver on March 3, 1946.

Marburg was born in Baltimore, Maryland on July 10, 1862, which means that McRae was already dead when the poet was born. I found that interesting, and wondered what caused him to want to write a poem about someone he never knew. He died in Vancouver on March 3, 1946.

The poem about Captain McRae, entitled DIVIDED DUTY, comes from In The Hills: Poems, a small volume that was privately printed in Paris 1893, then revised and reprinted by The Knickerocker Press, a division of G.P. Putnam’s Sons, in 1924.

The poem has a footnote, which says

When the American civil war began there happened to be in the regular service a young officer whose home, with all that the word implies, was the South. There were many such. His story is but a type. Is it difficult to picture the struggle that came to them with the sense of a divided duty? This one, with the clearer vision which events have justified, felt that the higher duty was the preservation of the nation; but the thought of fighting against his kindred and the friends of his boyhood so preyed on his mind that he is believed to have courted the death which soon came to him. When the element of fate enters, hurrying the just and the brave to a tragic end, the story must always excite our interest and sympathy. At the battle of Val Verde in New Mexico, February 21, 1862, our hero met his death. The battery, of which, although a cavalry officer, he had been given command for the day, was overwhelmed by the Texans. He remained seated on one of the guns, defending himself until the enemy shot him down. They did him the honor to give his name to one of our forts and to take him back to West Point, to the quiet cemetery in the hills.

McRae's tombstone. It is just four stones down from that of George Armstrong Custer The poem is almost as much about the beautiful setting of the West Point Cemetery as it is about the man buried there. It made me wonder if the tombstone inspired the poet to research the man buried beneath it.

McRae's tombstone. It is just four stones down from that of George Armstrong Custer The poem is almost as much about the beautiful setting of the West Point Cemetery as it is about the man buried there. It made me wonder if the tombstone inspired the poet to research the man buried beneath it.

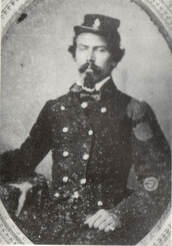

McRae, a native North Carolinian, commanded Company I, 3rd United States Regular Cavalry. His commanding officer, Colonel Edward R.S. Canby, had given him an artillery battery of six pieces. During the Battle of Valverde, February 21, 1862, McRae's battery performed with great success until about 750 Confederate Texans led by Colonel Thomas Green charged the Union guns. Screaming the Rebel yell, the three waves of confederates were poorly armed with short-range shotguns, pistols, muskets, and bowie knives. Green had instructed his men to drop to the ground whenever they saw flashes from the artiller's muzzles. The Union men thought they were inflicting great casualties on the Rebels, but the fact that they just kept coming spooked the New Mexico Volunteers supporting McRae and his officers. Many fled the battery and ran panic-stricken across the Rio Grande, unnerving the Volunteer troops who were then being held in reserve.