Jennifer Bohnhoff's Blog, page 10

March 24, 2024

Where Have All The Soldiers Gone?

Mike, the interpreter Yesterday I went up to Pecos National Historic Park to attend a talk commemorating the 162nd anniversary of the Battle of Glorieta Pass.

Mike, the interpreter Yesterday I went up to Pecos National Historic Park to attend a talk commemorating the 162nd anniversary of the Battle of Glorieta Pass. The Battle, which took place March 26-28, 1862, is often called "The Gettysburg of the West." The man who gave the talk,a National Park employee (whose name I believe was Mike, but I didn't write it down and wasn't sure of by the time I got home) who came down from Fort Union,was in authentic Civil War dress. He gave a very nice synopsis of the battle, then a demonstration of his Springfield rifle, both of which the crowd of forty or so appreciated.

But it wasn't what I'd hoped for.

Union reenactors in Escondido in February, 2022. It used to be that every year, on the weekend closest to March 26-28, the Park would sponsor a reenactment of the Battle of Glorieta. Groups of reenactors, most in meticulously researched and authentic dress, would set up camps, one for the Confederate forces and one for the Union forces. All weekend, tourists could wander among the tents asking questions and learning what life was like for the soldiers, merchants and camp women.

Union reenactors in Escondido in February, 2022. It used to be that every year, on the weekend closest to March 26-28, the Park would sponsor a reenactment of the Battle of Glorieta. Groups of reenactors, most in meticulously researched and authentic dress, would set up camps, one for the Confederate forces and one for the Union forces. All weekend, tourists could wander among the tents asking questions and learning what life was like for the soldiers, merchants and camp women.

Ken Dusenbery and I at an Albuquerque convention for Social Studies teachers in 2014. My connection to all this was a wonderful man named Ken Dusenbery. Ken, a veteran of the Vietnam war, was fascinated with military history. He was Corporal in the Artillery Company of New Mexico, a group of reenactors who took their jobs very seriously. Ken knew a lot about the life and times of the Civil War soldier and could tell you more about ammunition and "grub" than just about anyone alive. He read both Where Duty Calls and The Worst Enemy for me before they were published and helped me to get the details right.

Ken Dusenbery and I at an Albuquerque convention for Social Studies teachers in 2014. My connection to all this was a wonderful man named Ken Dusenbery. Ken, a veteran of the Vietnam war, was fascinated with military history. He was Corporal in the Artillery Company of New Mexico, a group of reenactors who took their jobs very seriously. Ken knew a lot about the life and times of the Civil War soldier and could tell you more about ammunition and "grub" than just about anyone alive. He read both Where Duty Calls and The Worst Enemy for me before they were published and helped me to get the details right.Ken has since passed away, leaving a big hole in my heart. I miss his knowledge and the kind way he corrected my errors. I regret he wasn't able to read through book 3 of the series, The Famished Country, which comes out this fall.

The last time I saw Ken was in March of 2022, at Pecos National Historical Park. That time, there were both Confederate and Union camps, and tourists got to wander through the tents asking questions. Ken's company brought their howitzer, which was fired off to great applause. Many of the reenactors had their weapons with them and were happy to show them to interested people, but weapons were not the only things of interest. I remember my mother asking about the tar bucket that hung from one of the wagons. Others asked about the cooking implements and the portable writing desk. And my favorite memory from the day was the youngest Union soldier, the son of a reenactor who was proudly participating for the first time. But there were no reenacted battles that year. Ken explained to me that the Park Service no longer wanted battles on their property. One ranger told me it was the gunsmoke that people complained of. Another said it was the glorification of war.

This year, the commemoration was distilled into just one person: Mike. He gave a great speech and fired three volleys, plus one more for an encore. But I missed the camps filled with men and women who've immersed themselves in the everyday life of the period and were so enthusiastic to share their knowledge with the rest of us.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a retired history and language arts teacher who is now writing full time. You can read more about here and her books on her website.

Published on March 24, 2024 10:42

March 7, 2024

Time to Play Ball Again

My husband at a game (because I take the pictures and am bad at selfies!) March is here, and that means wind and freakish weather and the promise of baseball. Before we know it, spring training will be over and my husband will be glued to the tube watching his favorite teams.

My husband at a game (because I take the pictures and am bad at selfies!) March is here, and that means wind and freakish weather and the promise of baseball. Before we know it, spring training will be over and my husband will be glued to the tube watching his favorite teams. And I do mean teams, with an s. Instead of rooting for just one team, my husband roots for the entire National League Central Division. The son of a strong St. Louis fan, he will cheer for the Pirates or the Cubs (and the Twins, even though they're American League. Me? I pick a few good looking young kids with funny batting stances to cheer for each year. Often, I cheer for the catchers on whatever team's playing.

And if you asked me to name a player, you'd get a mix of current players from a lot of different teams and players from long ago. I can't remember who plays for the Dodgers now versus who played for them when they were still in Brooklyn. Really, I'm just there for the beer and the crowd. So it should come as no surprise that I love books that combine baseball and historical fiction. Last spring I wrote a whole list of baseball books for middle grade readers, many of which were set in the past. Recently I've found two new additions to add to my list. They'll delight the baseball fan, and they'll give a glimpse into the past at the same time. That's a win-win to me, especially since both books feature teams from the National League's Central Division!

Both books were recently published by Kinkajou Press, an imprint of Artemesia Publishing, LLC that was created in 2007 to publish early reader, mid-grade, and young adult fiction. Artemesia also publishes titles for adults, including some really interesting baseball fiction, nonfiction and biography.

Click the titles below to find the books on Bookshop.org. Walter Steps Up To The Plate

It's 1927, and all twelve-year-old Walter wants is to hang out with his friends and go to Wrigley Field to watch his beloved Cubs play. Unfortunately, his mother develops tuberculosis, and he must accompany her west, where the air is drier and thinner and she has a hope of recovery. Walter finds himself boarding with his aunt, uncle, and a spoiled cousin who's not happy to share his room. The cost of caring for his mother is steep, but Walter steps up to the plate and takes on a job delivering newspapers. He encounters Al Capone, who just might be the answer to his family's financial straits, but at the price of Walter's integrity. This is a sweet story that will immerse readers into Albuquerque when it was still a small and dusty town. They'll also learn a lot about the Great Depression. And while the times were different, young readers will understand and root for this scrappy young protagonist. The Batboy and the Unbreakable Record

It's 1927, and all twelve-year-old Walter wants is to hang out with his friends and go to Wrigley Field to watch his beloved Cubs play. Unfortunately, his mother develops tuberculosis, and he must accompany her west, where the air is drier and thinner and she has a hope of recovery. Walter finds himself boarding with his aunt, uncle, and a spoiled cousin who's not happy to share his room. The cost of caring for his mother is steep, but Walter steps up to the plate and takes on a job delivering newspapers. He encounters Al Capone, who just might be the answer to his family's financial straits, but at the price of Walter's integrity. This is a sweet story that will immerse readers into Albuquerque when it was still a small and dusty town. They'll also learn a lot about the Great Depression. And while the times were different, young readers will understand and root for this scrappy young protagonist. The Batboy and the Unbreakable Record

It's 1938, and 12 year old Richie Goodwin' is facing an awful summer because his dad has broken his leg and Richie has to get a job to help support the family. But when he gets his dream job -- batboy for the Cincinnati Reds -- his life goes from miserable to fantastic. Richie's smart mouth and unwillingness to follow rules gets him in trouble, and he has to deal with bullies, but he learns his lessons and is able to stick around to see Johnny Vander Meer make history -- and set a record that might never be broken! If you don't know (I didn't!) both Johnny Vander Meer and his unbreakable record are real, not fiction. This is a great book for baseball loving boys, middle grade readers of historical fiction, and anyone who wants to see a boy make good in a difficult situation. I've got one copy of each book, and now that I've read and enjoyed them, I'd like to pass them on. If you'd like either book, leave a comment. Tell me which one and why, and I may choose you!

It's 1938, and 12 year old Richie Goodwin' is facing an awful summer because his dad has broken his leg and Richie has to get a job to help support the family. But when he gets his dream job -- batboy for the Cincinnati Reds -- his life goes from miserable to fantastic. Richie's smart mouth and unwillingness to follow rules gets him in trouble, and he has to deal with bullies, but he learns his lessons and is able to stick around to see Johnny Vander Meer make history -- and set a record that might never be broken! If you don't know (I didn't!) both Johnny Vander Meer and his unbreakable record are real, not fiction. This is a great book for baseball loving boys, middle grade readers of historical fiction, and anyone who wants to see a boy make good in a difficult situation. I've got one copy of each book, and now that I've read and enjoyed them, I'd like to pass them on. If you'd like either book, leave a comment. Tell me which one and why, and I may choose you!

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a former educator who enjoys eating hotdogs and crackerjack and sitting next to her husband in ballparks. She is the author of a number of middle grade and adult books, many of them historical fiction. Kinkajou Press published two of the middle grade novels in her Rebels on the Rio Grande Trilogy: Where Duty Calls and The Worst Enemy. The third novel, The Famished Country, will come out this fall. A novel set in New Mexico 11,000 years ago, In the Shadow of Sunrise, is scheduled for release by Kinkajou next spring.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a former educator who enjoys eating hotdogs and crackerjack and sitting next to her husband in ballparks. She is the author of a number of middle grade and adult books, many of them historical fiction. Kinkajou Press published two of the middle grade novels in her Rebels on the Rio Grande Trilogy: Where Duty Calls and The Worst Enemy. The third novel, The Famished Country, will come out this fall. A novel set in New Mexico 11,000 years ago, In the Shadow of Sunrise, is scheduled for release by Kinkajou next spring.

Published on March 07, 2024 12:09

February 28, 2024

Pancho Villa and the Raid on Columbus

In 1915, the Mexican Revolution had been going on for five years. The decades-long regime of President Porfirio Díaz had ended, and a power struggle between elites and the middle classes, in addition to labor and agrarian unrest had led to armed uprisings resulting in the assassination of Diaz’ successor, Francisco I. Madero under the orders of the next president, Victoriano Huerta. Huerta’s counter-revolutionary regime was opposed by a coalition of leaders from the Mexican states, including a Constitutionalist Army led by Governor of Coahuila, Venustiano Carranza, Emiliano Zapata who was leading an armed rebellion in Morelos, and the governor of Chihuahua, Francisco "Pancho" Villa, who led his own army in the northern part of Mexico. However, once Carranza took power, the alliance he’d had with Villa, Zapata and others dissolved and they began fighting among themselves. By spring of 1916, Villa’s army was little more than a disorganized band, wandering northern Mexico in search of supplies. The 1915 Battle of Celaya had been a great defeat for Villa, and his army lacked the military supplies, money, and munitions needed to pursue his war against Carranza. While the reasons for the raid have never been established with any certainty, it is likely out of desperation that Villa planned the raid on the New Mexican border town of Columbus and the adjoining Camp Furlong. He camped his army of an estimated 1,500 horsemen outside of Palomas on the border three miles south of Columbus and waited for the right time to surge over the border and steal the supplies he so desperately needed.

In 1915, the Mexican Revolution had been going on for five years. The decades-long regime of President Porfirio Díaz had ended, and a power struggle between elites and the middle classes, in addition to labor and agrarian unrest had led to armed uprisings resulting in the assassination of Diaz’ successor, Francisco I. Madero under the orders of the next president, Victoriano Huerta. Huerta’s counter-revolutionary regime was opposed by a coalition of leaders from the Mexican states, including a Constitutionalist Army led by Governor of Coahuila, Venustiano Carranza, Emiliano Zapata who was leading an armed rebellion in Morelos, and the governor of Chihuahua, Francisco "Pancho" Villa, who led his own army in the northern part of Mexico. However, once Carranza took power, the alliance he’d had with Villa, Zapata and others dissolved and they began fighting among themselves. By spring of 1916, Villa’s army was little more than a disorganized band, wandering northern Mexico in search of supplies. The 1915 Battle of Celaya had been a great defeat for Villa, and his army lacked the military supplies, money, and munitions needed to pursue his war against Carranza. While the reasons for the raid have never been established with any certainty, it is likely out of desperation that Villa planned the raid on the New Mexican border town of Columbus and the adjoining Camp Furlong. He camped his army of an estimated 1,500 horsemen outside of Palomas on the border three miles south of Columbus and waited for the right time to surge over the border and steal the supplies he so desperately needed.

Columbus was a small town of about 300 Americans and about as many Mexicans. Located just three miles north of the border with Mexico. It sat side by side with Camp Furlong, a small garrison intended to patrol and protect the border. It consisted the headquarters troop, one machine gun troop, and seven rifle troops, totaling 12 officers and 341 men, of which approximately 270 were combat troops.

Columbus was a small town of about 300 Americans and about as many Mexicans. Located just three miles north of the border with Mexico. It sat side by side with Camp Furlong, a small garrison intended to patrol and protect the border. It consisted the headquarters troop, one machine gun troop, and seven rifle troops, totaling 12 officers and 341 men, of which approximately 270 were combat troops.

Before the raid, Villa sent spies into the town to assess the presence of U.S. military personnel. They reported that only about thirty soldiers were garrisoned at Columbus. This was a significant error. On the night of the raid, approximately half of the 362 soldiers were out of camp on patrol, leave, or other assignments, but even at that reduced number, there were far more troops than Villa anticipated. Not knowing this, Villa moved north and crossed the border about midnight. Maude Hauke Wright, an American kidnap victim who was travelling with the raiding party, stated that Villa only sent 600 of his 1,500 men into the attack because he lacked the ammunition to arm them all. Early in the morning of March 9, 1916, Villa divided his force into two columns. At 4:15, when it was still dark, he launched a a two-pronged attack on the town and the garrison. Most of the attacker approached on foot, their mounts left safely back with the rest of Villa’s troops. Some claim that Villa never crossed the border, but remained in Palomas. Others swear that he directed the attack from Cootes Hill, a small promontory overlooking Columbus.

The clock in the Columbus train station,, stopped when struck by a Villista bullet. The Villistas entered Columbus from the west and southeast shouting "¡Viva Villa! ¡Viva Mexico!" and other phrases. The townspeople awoke to find their settlement in flames and the Mexicans looting their homes and shops. The raid soon escalated into a full-scale battle between Villistas and the United States Army. 2nd Lt. John P. Lucas made his way barefooted from his quarters to the camp's barracks, where he organized a hasty defense around the camp's guard tent, preventing the Villistas from stealing the troop’s machine guns. The troop's four machine guns fired more than 5,000 rounds apiece during the 90-minute fight, their targets illuminated by fires of burning buildings. Soldiers joined with Springfield rifles, and many of the townsfolk had shotguns and hunting guns of their own.

The clock in the Columbus train station,, stopped when struck by a Villista bullet. The Villistas entered Columbus from the west and southeast shouting "¡Viva Villa! ¡Viva Mexico!" and other phrases. The townspeople awoke to find their settlement in flames and the Mexicans looting their homes and shops. The raid soon escalated into a full-scale battle between Villistas and the United States Army. 2nd Lt. John P. Lucas made his way barefooted from his quarters to the camp's barracks, where he organized a hasty defense around the camp's guard tent, preventing the Villistas from stealing the troop’s machine guns. The troop's four machine guns fired more than 5,000 rounds apiece during the 90-minute fight, their targets illuminated by fires of burning buildings. Soldiers joined with Springfield rifles, and many of the townsfolk had shotguns and hunting guns of their own.

Finally, a bugler sounded the order to retreat and the Villistas disappeared back over the border, pursued by the regiment's 3rd Squadron until it ran low on ammunition and water.

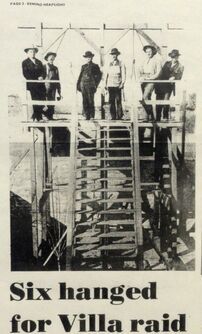

Finally, a bugler sounded the order to retreat and the Villistas disappeared back over the border, pursued by the regiment's 3rd Squadron until it ran low on ammunition and water.Villa announced that the raid was a success, and that he’d captured 300 rifles and shotguns, 80 horses, and 30 mules. However, he’d also lost between 90 and 170 men, 63 killed in action and at least seven more who later died from wounds during the raid itself. The sixty-three dead Villa soldiers and all the dead Villa horses that were left behind in Columbus after the raid were dragged south of the stockyards, soaked with kerosene and burned. Of those captured during the raid, seven were tried and six hanged. Although records are inconsistent, the American dead seems to range between 8 to 11 soldiers and 7 or 8 civilians.

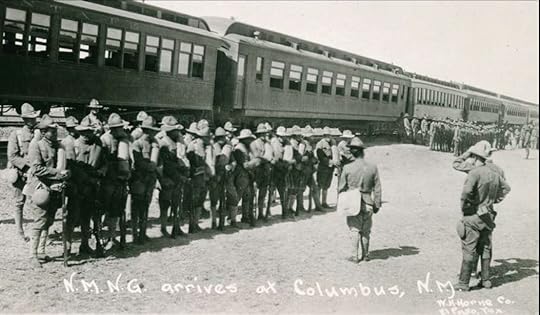

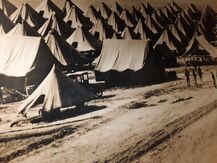

The tents at Camp Furlough when it was at its height. Photo by author, taken at display in Pancho Villa museum The American public was outraged by Villa’s attack and the United States government wasted no time in responding. First on the scene were elements of the New Mexico National Guard. Other National Guard units from around the United States were called up. By the end of August 1916 over 100,000 troops were amassed on the border, with 5,000 headquartered at Camp Furlong. Camp Furlong also had supply facilities and repair yards for the early motor trucks used in Mexico when General John J. Pershing moved the Punitive Expedition into Mexico to track down Villa. Columbus also had the first tactical military airfield in the United States. The 1st Aero Squadron's Curtiss JN3 Jenny biplanes provided aerial observation and communications for the expedition.

The tents at Camp Furlough when it was at its height. Photo by author, taken at display in Pancho Villa museum The American public was outraged by Villa’s attack and the United States government wasted no time in responding. First on the scene were elements of the New Mexico National Guard. Other National Guard units from around the United States were called up. By the end of August 1916 over 100,000 troops were amassed on the border, with 5,000 headquartered at Camp Furlong. Camp Furlong also had supply facilities and repair yards for the early motor trucks used in Mexico when General John J. Pershing moved the Punitive Expedition into Mexico to track down Villa. Columbus also had the first tactical military airfield in the United States. The 1st Aero Squadron's Curtiss JN3 Jenny biplanes provided aerial observation and communications for the expedition.Following the withdrawal of the Punitive Expedition, the importance of Camp Furlong declined. By 1920, when the Mexican Revolution ended, only 100 men were garrisoned there. All troops were gone by 1923.

Jennifer Bohnhoff's historical novel A Blaze of Poppies is the story of a young female rancher who is trying to keep her family's ranch and a member of the New Mexico National Guard who is in the area to protect the border. Agnes Day and Will Bowers both get drawn into Pancho Villa's raid, the ensuing Punitive Expedition, and World War I. Inspired by real stories set in the time and area, this is a work of fiction that will inspire and educate as well as entertain.

Jennifer Bohnhoff's historical novel A Blaze of Poppies is the story of a young female rancher who is trying to keep her family's ranch and a member of the New Mexico National Guard who is in the area to protect the border. Agnes Day and Will Bowers both get drawn into Pancho Villa's raid, the ensuing Punitive Expedition, and World War I. Inspired by real stories set in the time and area, this is a work of fiction that will inspire and educate as well as entertain.

Published on February 28, 2024 23:00

February 14, 2024

Walnut Pie

I’ve been sharing

Perspective

, an historical novel set on Isle Royale during the Great Depression, with my critique group. This past session, my chapter included a scene where the characters make a walnut pie. It fit into my chapter well, since the characters, Genevieve and Ida, are using the shells to create ornaments for their Christmas tree, and if they’re shelling walnuts, they’d better do something with the meat. But I’d never researched further to find out just what was in that pie.

I’ve been sharing

Perspective

, an historical novel set on Isle Royale during the Great Depression, with my critique group. This past session, my chapter included a scene where the characters make a walnut pie. It fit into my chapter well, since the characters, Genevieve and Ida, are using the shells to create ornaments for their Christmas tree, and if they’re shelling walnuts, they’d better do something with the meat. But I’d never researched further to find out just what was in that pie.

“Walnut pie?” my critic partners wondered. “What’s that? What goes into it? What does it taste like?”

Creator: Rainer Lesniewski | Credit: Getty Images/iStockphoto In truth, I didn’t know. I’d included it because it was convenient. Maybe it was mentioned in one of the memoirs written by an islander that I had read while writing the first draft of this novel back in 2002, but I’ve forgotten whether that was the case, or I’d just made-up walnut pies out of thin air. Clearly, I needed to do more research.

Creator: Rainer Lesniewski | Credit: Getty Images/iStockphoto In truth, I didn’t know. I’d included it because it was convenient. Maybe it was mentioned in one of the memoirs written by an islander that I had read while writing the first draft of this novel back in 2002, but I’ve forgotten whether that was the case, or I’d just made-up walnut pies out of thin air. Clearly, I needed to do more research. Isle Royale is a long, thin island in Lake Superior, the westernmost of the Great Lakes. To some people, Lake Superior looks like a wolf looking to the left, and Isle Royale is the eye. Isle Royale is a national park now. Earlier, it had been a site of copper mining, fishing and logging operations, and marginal farming. By the early 1930s, most of the inhabitants were only seasonal, visiting every summer to escape the heat and humidity of mainland Michigan and Minnesota. Tourists visited the island's hotels. Only a small but hardy group of fisherman endured hard winters cut off from the rest of the world by treacherous ice. What kind of pie, I wondered, would these independent souls create in their isolated wilderness homes?

There are lots of recipes for pies with walnuts on the internet. Many are fruit pies, often apple or apple and cranberry. Some, called Amish walnut pies, included oatmeal. Another Amish pie had whipping cream and gelatin. Many were similar to pecan pies. I didn’t find any pies on the internet that were called Isle Royale pie or even Michigan or Minnesota pies. Even if the inhabitants of this Lake Superior Island had made pies, they’d left easily accessible record on the internet, and I was in Maine while all my printed resource material was back in New Mexico. If I wanted a pie recipe now, I’d have to create it myself.

There are lots of recipes for pies with walnuts on the internet. Many are fruit pies, often apple or apple and cranberry. Some, called Amish walnut pies, included oatmeal. Another Amish pie had whipping cream and gelatin. Many were similar to pecan pies. I didn’t find any pies on the internet that were called Isle Royale pie or even Michigan or Minnesota pies. Even if the inhabitants of this Lake Superior Island had made pies, they’d left easily accessible record on the internet, and I was in Maine while all my printed resource material was back in New Mexico. If I wanted a pie recipe now, I’d have to create it myself.

The recipe I finally settled on is very simple, like I assume my characters, living in an isolated island forest, would be most likely to make. It uses maple syrup, which was then produced on the island in small quantities for use by the local inhabitants. I made a test pie and shared it with my family and they pronounced it a winner, so here it is.

Walnut Pie Put a pie crust into a 9” pie plate.

(Don’t have your own pie crust recipe? Click here for one of mine.)

Preheat oven to 375°

Place 1 ½ cup chopped walnuts on a baking sheet.

Bake 5-7 minutes to toast the nuts and bring out the flavor.

Mix together:

½ cup brown sugar

2 TBS flour

1 ¼ cup maple syrup

3 TBS melted butter

¼ tsp salt

3 eggs

1 tsp vanilla extract

Stir in toasted walnuts. Pour into shell.

Bake for 40-45 minutes. Let cool completely before slicing and serving.

Jennifer Bohnhoff writes historical and contemporary fiction for middle grade through adult readers from her home high in the mountains of central New Mexico. She and her family visited Isle Royale during the summer of 2000, where they camped, canoed and portaged by day and listened to the wolves howl by night. During her ten days there, she fell in love with the island and its history. Perspective, her novel set there during the Great Depression, may come out this summer. The cover will be a lot better than the one pictured here.

Jennifer Bohnhoff writes historical and contemporary fiction for middle grade through adult readers from her home high in the mountains of central New Mexico. She and her family visited Isle Royale during the summer of 2000, where they camped, canoed and portaged by day and listened to the wolves howl by night. During her ten days there, she fell in love with the island and its history. Perspective, her novel set there during the Great Depression, may come out this summer. The cover will be a lot better than the one pictured here.

Published on February 14, 2024 23:00

February 7, 2024

Heritage Fiction

Have you ever heard of Heritage Fiction? I hadn’t until I came across Ora Smith, a genealogist who creates fascinating historical fiction based on true events involving her ancestors. I’ve read two of her novels now, and I’m fascinated at the depth of research she puts into her stories.

Have you ever heard of Heritage Fiction? I hadn’t until I came across Ora Smith, a genealogist who creates fascinating historical fiction based on true events involving her ancestors. I’ve read two of her novels now, and I’m fascinated at the depth of research she puts into her stories.I read White Oak River: A Story of Slavery's Secrets a while back. It’s the story of Caroline Gibson, who leaves a life of privilege on a plantation that uses slave labor to marry an abolitionist preacher, the Reverend John Mattocks. This couple is the author’s great-great-great-grandparents, from coastal North Carolina. When she gives birth to a son with dominant African traits, Caroline must decide if she’ll hold onto her bigotry at the cost of her relationships with both her husband and her son. The novel does an excellent job portraying that the Civil War may have changed laws, it failed to create a change of heart within southern society.

I just finished reading Smith’s The Peace of Pocahontas: Based on a True Story. This novel is the middle in a trilogy about Pocahontas and her role in securing peace between the Native peoples and the English colonizers. Chapters are presented in the voice of Pocahontas and of Thomas Savage, an orphan and indentured servant who lived among the Natives and served as an interpreter, and who is an ancestor of the author. It takes place in Virginia in 1613, when Pocahontas is kidnapped after three years of war. During her captivity, she learns English customs, wears English clothing, converts to Anglicanism, and marries John Rolfe. This series is a fascinating dive into a chapter in American history that most people are familiar with.

I just finished reading Smith’s The Peace of Pocahontas: Based on a True Story. This novel is the middle in a trilogy about Pocahontas and her role in securing peace between the Native peoples and the English colonizers. Chapters are presented in the voice of Pocahontas and of Thomas Savage, an orphan and indentured servant who lived among the Natives and served as an interpreter, and who is an ancestor of the author. It takes place in Virginia in 1613, when Pocahontas is kidnapped after three years of war. During her captivity, she learns English customs, wears English clothing, converts to Anglicanism, and marries John Rolfe. This series is a fascinating dive into a chapter in American history that most people are familiar with. As luck would have it, I ended up reading another author in 2023 who is also writing Heritage Fiction. Olivia Hawker writes historical fiction, some of which is based on stories from her own family.

As luck would have it, I ended up reading another author in 2023 who is also writing Heritage Fiction. Olivia Hawker writes historical fiction, some of which is based on stories from her own family.

One of them, The Fire and the Ore, tells the story of three women: Tabitha, Jane, and Tamar, who are all wives of Thomas Ricks, one of the early Mormon settlers in Utah Territory. Set in 1856, the novel follows Tamar Loader and her family through a brutal pilgrimage from England to Utah, when she meets the man she is sure is destined to be her husband. She agrees to a polygamous union that is threatened when the US Army invades to stop the Mormon community from engaging in what they consider illegal practices. This is a part of U.S. History that few textbooks mention.

Hawker also wrote The Ragged Edge of Night, which tells the story of her grandfather and grandmother during World War II. When the Nazis close his school for handicapped children, Franciscan friar Anton Starzmann moves to a small German hamlet to wed —in name only—a widow who needs someone to protect her and help raise her three children. He joins the Red Orchestra, an underground network of resisters plotting to assassinate Hitler, but questions his values as he finds himself falling in love with his wife. This is a tense story, filled with beauty and emotion.

Hawker also wrote The Ragged Edge of Night, which tells the story of her grandfather and grandmother during World War II. When the Nazis close his school for handicapped children, Franciscan friar Anton Starzmann moves to a small German hamlet to wed —in name only—a widow who needs someone to protect her and help raise her three children. He joins the Red Orchestra, an underground network of resisters plotting to assassinate Hitler, but questions his values as he finds himself falling in love with his wife. This is a tense story, filled with beauty and emotion.

We all have family stories that we think would be good novels. The incidents our forebears went through were often dramatic and harrowing. I know it’s unlikely that I ever turn my family stories into novels: there’d be too many relatives who’d dispute the events or be offended by the portrayals of the people in their family. I’m glad Ora Smith and Olivia Hawker were able to overcome their worries (if they had any!) and produce such interesting windows into the past.

Jennfer Bohnhoff writes historical and contemporary fiction for middle grade through adult readers. None of her books have been based on her own family. You can read more about her and her books here.

For more on Ora Smith, go to her website at https://orasmith.com/

For more on Olivia Hawker, go to her website at https://www.hawkerbooks.com/

Published on February 07, 2024 23:00

January 31, 2024

Pareidolia

Have you ever heard a word for the first time, and then it seems to come up over and over in the next few days? This seems to happen to me with some regularity. A few weeks ago, that word was pareidolia.

Pareidolia sounds like a cross between paranoia and indolence: laying around and worrying that someone is watching you. But that’s not what it is. Pareidolia is defined as seeing significant patterns or recognizable images, especially faces, in random or accidental arrangements of shapes and lines: seeing significant images in insignificant things.

Pareidolia seems to be central to the human psyche. We’ve been doing it a long, long time. Take, for instance, the constellations: humans look at stars, randomly spaced throughout the sky, often millions of light years apart, and see pictures. Connect the dots and a group of stars becomes a mighty hunter facing off against a raging bull, twin brothers with their arms about each other’s shoulders, a queen sitting on her throne, a long-tailed bear.

Pareidolia seems to be central to the human psyche. We’ve been doing it a long, long time. Take, for instance, the constellations: humans look at stars, randomly spaced throughout the sky, often millions of light years apart, and see pictures. Connect the dots and a group of stars becomes a mighty hunter facing off against a raging bull, twin brothers with their arms about each other’s shoulders, a queen sitting on her throne, a long-tailed bear.

Another common form of pareidolia is cloud watching. I have one friend who frequently posts pictures of clouds on Facebook. A whole lot of her friends see things in those clouds.

Photo Credit: NPS Photo, Sarah Sherwood Her friends are not the only people on Facebook who practice Pareidolia. Recently, White Sands National Park, in the southern part of New Mexico recently admitted that in the park they frequently play "what do you see in that pedestal?" Pedestals are raised places that form when the moisture in a plant’s root system cements together a clump of the gypsum sand, creating a column that the wind then sculps into interesting shapes. Ranger Sarah thought this pedestal looked like a great white shark emerging from the sands.

Photo Credit: NPS Photo, Sarah Sherwood Her friends are not the only people on Facebook who practice Pareidolia. Recently, White Sands National Park, in the southern part of New Mexico recently admitted that in the park they frequently play "what do you see in that pedestal?" Pedestals are raised places that form when the moisture in a plant’s root system cements together a clump of the gypsum sand, creating a column that the wind then sculps into interesting shapes. Ranger Sarah thought this pedestal looked like a great white shark emerging from the sands.

A meme on Facebook showed a line of happy tires. One reader commented that they’d had a good year. Another meme showed a terrified couch.

My hiking group hikes up to Old Man Rock nearly every February.

When I built my house, I told the person selling me tile that I wanted something that would hide dog hair and coffee spills. I ended up with a mottled tan tile that is very conducive to my own pareidolic musings. Some images seem to come and go, like mirages. Others, like this one, stayed so vivid that I felt compelled to sketch it. What do you think? Do you see the vulture leaning over the hippo's shoulder, or something else?

When I built my house, I told the person selling me tile that I wanted something that would hide dog hair and coffee spills. I ended up with a mottled tan tile that is very conducive to my own pareidolic musings. Some images seem to come and go, like mirages. Others, like this one, stayed so vivid that I felt compelled to sketch it. What do you think? Do you see the vulture leaning over the hippo's shoulder, or something else?

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a writer who lives his in the mountains of central New Mexico. When she isn't staring out the window at clouds or finding pictures in the tile, she's writing historical and contemporary fiction for middle grade through adult readers. You can read more about her and her books on her website.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a writer who lives his in the mountains of central New Mexico. When she isn't staring out the window at clouds or finding pictures in the tile, she's writing historical and contemporary fiction for middle grade through adult readers. You can read more about her and her books on her website.

Pareidolia sounds like a cross between paranoia and indolence: laying around and worrying that someone is watching you. But that’s not what it is. Pareidolia is defined as seeing significant patterns or recognizable images, especially faces, in random or accidental arrangements of shapes and lines: seeing significant images in insignificant things.

Pareidolia seems to be central to the human psyche. We’ve been doing it a long, long time. Take, for instance, the constellations: humans look at stars, randomly spaced throughout the sky, often millions of light years apart, and see pictures. Connect the dots and a group of stars becomes a mighty hunter facing off against a raging bull, twin brothers with their arms about each other’s shoulders, a queen sitting on her throne, a long-tailed bear.

Pareidolia seems to be central to the human psyche. We’ve been doing it a long, long time. Take, for instance, the constellations: humans look at stars, randomly spaced throughout the sky, often millions of light years apart, and see pictures. Connect the dots and a group of stars becomes a mighty hunter facing off against a raging bull, twin brothers with their arms about each other’s shoulders, a queen sitting on her throne, a long-tailed bear.

Another common form of pareidolia is cloud watching. I have one friend who frequently posts pictures of clouds on Facebook. A whole lot of her friends see things in those clouds.

Photo Credit: NPS Photo, Sarah Sherwood Her friends are not the only people on Facebook who practice Pareidolia. Recently, White Sands National Park, in the southern part of New Mexico recently admitted that in the park they frequently play "what do you see in that pedestal?" Pedestals are raised places that form when the moisture in a plant’s root system cements together a clump of the gypsum sand, creating a column that the wind then sculps into interesting shapes. Ranger Sarah thought this pedestal looked like a great white shark emerging from the sands.

Photo Credit: NPS Photo, Sarah Sherwood Her friends are not the only people on Facebook who practice Pareidolia. Recently, White Sands National Park, in the southern part of New Mexico recently admitted that in the park they frequently play "what do you see in that pedestal?" Pedestals are raised places that form when the moisture in a plant’s root system cements together a clump of the gypsum sand, creating a column that the wind then sculps into interesting shapes. Ranger Sarah thought this pedestal looked like a great white shark emerging from the sands.A meme on Facebook showed a line of happy tires. One reader commented that they’d had a good year. Another meme showed a terrified couch.

My hiking group hikes up to Old Man Rock nearly every February.

When I built my house, I told the person selling me tile that I wanted something that would hide dog hair and coffee spills. I ended up with a mottled tan tile that is very conducive to my own pareidolic musings. Some images seem to come and go, like mirages. Others, like this one, stayed so vivid that I felt compelled to sketch it. What do you think? Do you see the vulture leaning over the hippo's shoulder, or something else?

When I built my house, I told the person selling me tile that I wanted something that would hide dog hair and coffee spills. I ended up with a mottled tan tile that is very conducive to my own pareidolic musings. Some images seem to come and go, like mirages. Others, like this one, stayed so vivid that I felt compelled to sketch it. What do you think? Do you see the vulture leaning over the hippo's shoulder, or something else?

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a writer who lives his in the mountains of central New Mexico. When she isn't staring out the window at clouds or finding pictures in the tile, she's writing historical and contemporary fiction for middle grade through adult readers. You can read more about her and her books on her website.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a writer who lives his in the mountains of central New Mexico. When she isn't staring out the window at clouds or finding pictures in the tile, she's writing historical and contemporary fiction for middle grade through adult readers. You can read more about her and her books on her website.

Published on January 31, 2024 14:00

January 25, 2024

Room to Write

When I celebrated my birthday this month, one of my kids gave me a copy of Rooms of Their Own: Where Great Writers Write, by Alex Johnson. Illustrated with colorful, loose pen and watercolors by James Oses, this book shares the writing rooms that fifty famous authors used to create their works, and offers glimpses into their writing methods, routines and habits. It’s made me think a bit about my own space. When I’m at home, my writing is a bit of a mobile project. I move between a round table or drop-down desk in a study in the northwest corner of my home, and a lowered section of countertop in my pantry. Each has its own appeal. The round table has a lovely view north, over mountains and valleys. The drop-down is a convenient place to hide away my laptop and all my reference materials when I just can’t look at them anymore. Both are close to the router and printer, so they’re the best place if I’m making copies to read aloud or for future reference. The desk in the pantry is close to the kitchen and has the best room if I need to spread out materials. Sometimes I work from all three spaces in a single day. There are other times when I inhabit just one space for weeks on end.

When I celebrated my birthday this month, one of my kids gave me a copy of Rooms of Their Own: Where Great Writers Write, by Alex Johnson. Illustrated with colorful, loose pen and watercolors by James Oses, this book shares the writing rooms that fifty famous authors used to create their works, and offers glimpses into their writing methods, routines and habits. It’s made me think a bit about my own space. When I’m at home, my writing is a bit of a mobile project. I move between a round table or drop-down desk in a study in the northwest corner of my home, and a lowered section of countertop in my pantry. Each has its own appeal. The round table has a lovely view north, over mountains and valleys. The drop-down is a convenient place to hide away my laptop and all my reference materials when I just can’t look at them anymore. Both are close to the router and printer, so they’re the best place if I’m making copies to read aloud or for future reference. The desk in the pantry is close to the kitchen and has the best room if I need to spread out materials. Sometimes I work from all three spaces in a single day. There are other times when I inhabit just one space for weeks on end.

I’ve been housesitting in Maine for the past month. There is a study in this house, but it is cold enough that I find my fingers going blue at the tips. I’ve done most of my work while sitting at a dining room table that looks out at a lake. I’ve seen that lake in full color, with green grass and a brilliant blue sky. It’s been so muted that I swore I was looking through a black and white filter. The water has been fully liquid, fully frozen, and many permutations in between: rippling with waves, smooth as glass, riddled with cracks, coated with snow.

Looking out on the lake has been especially inspiring to me because one of the pieces I’m working on is set on Isle Royale, an island in Lake Superior that is now a national park. My story takes place during the Depression, and the characters are families that live on the island full time and make their living by fishing. I worked on chapters set in the dead of winter, when the island is cut off from the mainland by huge, destructive ice floes. Frozen lakes aren’t something this New Mexican has experienced much. Neither is walking through mixed deciduous and evergreen forests. Even though I live with my back up against a national forest, it is primarily ponderosa and fir, evergreens that keep their needles and their shape throughout the winter. Here in Maine, a good 50% of the trees have lost their leaves. Combined with the frozen streams that run through the woods, the forest here seems a lot more bleak and desolate than the one I’m used to. It’s helped me add a lot of depth to my book’s setting.

Looking out on the lake has been especially inspiring to me because one of the pieces I’m working on is set on Isle Royale, an island in Lake Superior that is now a national park. My story takes place during the Depression, and the characters are families that live on the island full time and make their living by fishing. I worked on chapters set in the dead of winter, when the island is cut off from the mainland by huge, destructive ice floes. Frozen lakes aren’t something this New Mexican has experienced much. Neither is walking through mixed deciduous and evergreen forests. Even though I live with my back up against a national forest, it is primarily ponderosa and fir, evergreens that keep their needles and their shape throughout the winter. Here in Maine, a good 50% of the trees have lost their leaves. Combined with the frozen streams that run through the woods, the forest here seems a lot more bleak and desolate than the one I’m used to. It’s helped me add a lot of depth to my book’s setting.

I am not the only writer who becomes inspired by bleak surroundings. Rooms of Their Own tells me that George Orwell wrote Nineteen Eighty-Four while in self-exile on Jura, and island in Scotland’s Inner Hebrides. The environment was harsh, and Orwell had few creature comforts. He lived spartanly, moving about the house, from sitting room to attic, to bedroom, to work where inspiration hit him. Although the austerity of his lifestyle was doubtless inspirational for his work, it was hard on his body; Orwell was suffering from tuberculosis, and the cold, damp air and his chain-smoking made his condition worse.

Victor Hugo also wrote while in exile, although his was political. Hugo got himself crossways with Napoleon III, so he moved to Guernsey in 1855. Over the next fifteen years, he wrote from a room he built at the top of his house. The room had windows on three walls and a glass ceiling that made it frigid in winter and broiling hot in summer, but it also gave him a view of the sky and the sea, and on clear days, his beloved France. Hugo wrote Les Mierables and Toilers of the Sea from this room.

Victor Hugo also wrote while in exile, although his was political. Hugo got himself crossways with Napoleon III, so he moved to Guernsey in 1855. Over the next fifteen years, he wrote from a room he built at the top of his house. The room had windows on three walls and a glass ceiling that made it frigid in winter and broiling hot in summer, but it also gave him a view of the sky and the sea, and on clear days, his beloved France. Hugo wrote Les Mierables and Toilers of the Sea from this room.

Tomorrow I’m leaving my own self-imposed exile and heading back to New Mexico. I’m looking forward to being home again, to trading mountain views for lakes and ponderosas for poplars. But I’ll be bringing the experiences I had back with me and they’ll find their way into my writing. Jennifer Bohnhoff writes historical and contemporary fiction for middle grade through adult readers from her home high in New Mexico's central mountains.

Published on January 25, 2024 14:19

January 19, 2024

George S. Patton Jr., Inventor

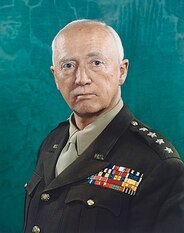

General George Patton by Robert F. Cranston, 1945 color carbro print, from the National Portrait Gallery George S. Patton is best known as the pugnacious general who guided the Third Army’s tanks through Europe in World War II. But he was also an inventor.

General George Patton by Robert F. Cranston, 1945 color carbro print, from the National Portrait Gallery George S. Patton is best known as the pugnacious general who guided the Third Army’s tanks through Europe in World War II. But he was also an inventor.Patton’s first invention, a saber, grew out of his participation in the 1912 Olympic Games. The Army's entry in the first modern pentathlon, Patton was the only American among the 42 pentathletes in Stockholm, Sweden that year. Patton finished fifth overall in the competition that involved pistol firing, swimming, fencing, an equestrian competition, and a footrace. Following the Olympics, Patton traveled through Europe, seeking to learn more about swordsmanship.

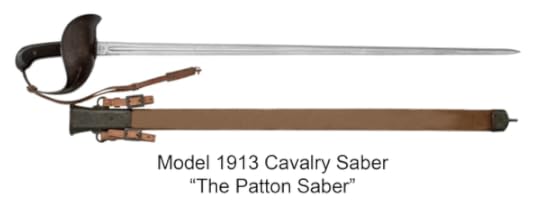

Patton, right, at the 1912 Olympics Patton learned that different countries utilized their swords in different ways. In the Peninsular War, part of the Napoleonic Wars fought in the Iberian Peninsula from 1807–1814, Spain, Portugal, and the United Kingdom fought against the First French Empire. The English, he learned, nearly always used the sword for cutting, while the French dragoons used only the point of their long straight swords, inflicting more fatal wounds. The English protested that the French did not fight fair. Once, when the cavalry of the guard passed in review before Napoleon, he called to them, "Don't cut! The point! The point!" When Patton returned to America, he wrote a report that was published in the March 1913 issue of the Army and Navy Journal. The next summer, while he was Master of the Sword at the Mounted Service School, Patton advised the Ordnance Department on sword redesign, contributing to the first significant changes in cavalry swords since the Model 1860 Light Cavalry Saber had been introduced. In 1914, Patton's system of swordsmanship was published by the War Department in a 1914 Saber Exercise manual. This manual emphasized the use of the point over the edge.

Patton, right, at the 1912 Olympics Patton learned that different countries utilized their swords in different ways. In the Peninsular War, part of the Napoleonic Wars fought in the Iberian Peninsula from 1807–1814, Spain, Portugal, and the United Kingdom fought against the First French Empire. The English, he learned, nearly always used the sword for cutting, while the French dragoons used only the point of their long straight swords, inflicting more fatal wounds. The English protested that the French did not fight fair. Once, when the cavalry of the guard passed in review before Napoleon, he called to them, "Don't cut! The point! The point!" When Patton returned to America, he wrote a report that was published in the March 1913 issue of the Army and Navy Journal. The next summer, while he was Master of the Sword at the Mounted Service School, Patton advised the Ordnance Department on sword redesign, contributing to the first significant changes in cavalry swords since the Model 1860 Light Cavalry Saber had been introduced. In 1914, Patton's system of swordsmanship was published by the War Department in a 1914 Saber Exercise manual. This manual emphasized the use of the point over the edge.  Patton’s saber ended up being ceremonial in use, since it was obsolete by the time it was created. Modern warfare made cavalry charges a thing of the past.

Patton’s saber ended up being ceremonial in use, since it was obsolete by the time it was created. Modern warfare made cavalry charges a thing of the past.Patton did not rest on his obsolete laurels. During World War I, he became a leading voice in the use of tanks. Immediately after the war, he became involved in improvements in his beloved iron horses. The first, which he worked on between 1919 and 1921, was a new coaxial gun mount that allowed greater range of motion for a tank’s big gun.

(Photo: 44thcollectorsavenue.com) In 1937 the Dehner footwear company introduced a new type of boot for tank crews. Partially designed by then-Lieutenant Colonel George S. Patton, the all-leather boot had straps to secure it instead of bootlaces and metal eyelets. Laces could become entangled in a tank’s moving parts, dragging the wearer’s foot into the machinery. Leather would not melt like the nylon used in previous Army boots. This saved tankers from serious burns when their boots touched hot, ejected shell casings or when escaping from a burning vehicle. Finally, since tank crews often spent a lot of time sitting inside their vehicles, they needed boots that allowed better blood circulation and less ankle support than infantry. Tanker boots provided just that, and are still in use today.

(Photo: 44thcollectorsavenue.com) In 1937 the Dehner footwear company introduced a new type of boot for tank crews. Partially designed by then-Lieutenant Colonel George S. Patton, the all-leather boot had straps to secure it instead of bootlaces and metal eyelets. Laces could become entangled in a tank’s moving parts, dragging the wearer’s foot into the machinery. Leather would not melt like the nylon used in previous Army boots. This saved tankers from serious burns when their boots touched hot, ejected shell casings or when escaping from a burning vehicle. Finally, since tank crews often spent a lot of time sitting inside their vehicles, they needed boots that allowed better blood circulation and less ankle support than infantry. Tanker boots provided just that, and are still in use today.  Soldiers wearing Dehner tank boots, WWII Some people think George Patton was a genius. Others consider him a madman. It is clear from his inventions that he had a keen eye for detail and wanted to ensure that his soldiers were given every advantage possible.

Soldiers wearing Dehner tank boots, WWII Some people think George Patton was a genius. Others consider him a madman. It is clear from his inventions that he had a keen eye for detail and wanted to ensure that his soldiers were given every advantage possible. Jennifer Bohnhoff writes historical fiction for middle grade through adult readers. You can read more about her and her books on her website.

Published on January 19, 2024 06:36

January 10, 2024

A Couple of Inspiring Christmas Gifts: Treasures from the Past

One of my sisters really gets me. I mean, really, really understands what interests and excites me. Luckily for me, she also loves to search ebay for unique things.

This past Christmas, I got two treasures from her that will undoubtably work their way into one of my novels. I’m sharing them with you and hope that they interest and excite you as much as they did me.

The first gift was a little brass box with an emblem that read “Gott Mit Uns” over a picture of a crown. After a little research, I discovered that Gott Mit Uns is German for God with us, and was a slogan used by the German army in World War I. The crown is the imperial crown of the Second Reich, and is described both as German and as Prussian online.

The first gift was a little brass box with an emblem that read “Gott Mit Uns” over a picture of a crown. After a little research, I discovered that Gott Mit Uns is German for God with us, and was a slogan used by the German army in World War I. The crown is the imperial crown of the Second Reich, and is described both as German and as Prussian online.

The emblem on the box originally graced a belt buckle on a uniform. Here is a picture of one still attached.

So how did this emblem get placed on a brass box? The answer is an interesting bit of World War I history. Most people know that World War I is notable as the war in which both sides hunkered down in trenches along a front that became unmovable. Soldiers spent many weary months hunkered down in the mud, waiting to go “over the top” and attack the other side. The waiting grew monotonous.

So how did this emblem get placed on a brass box? The answer is an interesting bit of World War I history. Most people know that World War I is notable as the war in which both sides hunkered down in trenches along a front that became unmovable. Soldiers spent many weary months hunkered down in the mud, waiting to go “over the top” and attack the other side. The waiting grew monotonous.

To counter the boredom, soldiers found things to do to occupy their time. They had to use what they had at hand, and once one creative soldier had invented a form of art, it seems all his buddies copied it. The thousands of examples of vases made from shell casings, each unique in its decorations, attests to the hundreds of thousands of shells that flew over the trenches.

Sometimes what was lying around was pieces of uniforms. The belt buckle on a German uniform is exactly the right size to be made into a match box. The one I have has a lid that separates from the box. Others I found online were hinged or were squared off tubes with open ends. On some, the smooth brass had been deckled or worked into ridges. I do not know if the top of the box is part of the original belt buckle or if it was fashioned from a fragment of a shell casing. Either way, I can imagine a soldier hunkered down in the cold and damp, intently working on a bit he picked up in no man’s land to turn it into a little trinket for his loved ones back home.

The second treasure my sister gave me is a little, paperback book entitled History and Rhymes of the Lost Battalion, by “Buck Private” McCollum. Lee Charles McCollum self-published a 32-page volume of poetry by that name in 1919. That edition included sketches by Franklin Sly, another veteran of the American Expeditionary Force that went to Europe in 1918. Pt. McCollum saw action in France in many of the same areas as the famous Lost Battalion, but he is not listed on the unit's roster. Whether that means he wrote under a nom de plume was something I was not able to ascertain. The books was again published in 1919, 1921, 1922, and 1929, by which time Franklin Sly had passed away and another veteran, and Tolman R. Reamer, had completed artwork. The little volume grew over time. By 1939 it was up to 140 pages and included stories, remembrances by some of the key figures in the fight, pictures and tributes both to the Battalion and to its commander, Lt. Col. Charles Whittlesey, who had passed away in 1921. Over 700,000 copies of the various editions were sold.

The volume tells the story of Battalion 1 of the 77th Division, which pushed hard into the Argonne Forest and found itself cut off from the rest of the American forces.

The volume tells the story of Battalion 1 of the 77th Division, which pushed hard into the Argonne Forest and found itself cut off from the rest of the American forces.

On the morning of October 3, 1918, Companies A, B, C, E, and H of the 808th Infantry, the 308th Infantry’s Company H, Company K of the 307th Infantry and Companies C and of 306th Machine Gun Battalion, all members of the Seventy-Seventh Division, were cut off from the other American forces near Charlevoix, in the Argonne Forest, and surrounded by a superior number of Germans. For four days, the approximately 550 men, under command of Major Charles W. Whittlesey managed to survive without food and with a dwindling supply of ammunition, fending off enemy machine gun, rifle, trench mortar, and grenade fire and some friendly fire from their own artillery. When they were finally reconnected with the main American force, only 194 of the officers and men were able to walk out of the position. 107 had been killed.

McCollum’s poems are about that experience, plus other observations in war, including poems about his gas mask and about kissing a French girl. Some are cute and sweet, while others are sad elegies to friends now dead. It’s a great volume for anyone interested in the experience of American doughboys.

I’m thinking I need to write a sequel to my WWI novel, a Blaze of Poppies, with a character who was in the Lost Battalion and now carries around a matchbox as a memento.

What do you think? Is that a story you'd like to read? If I ever write it, you can thank my sister. A Blaze of Poppies is an historical novel that tells the story of a New Mexico rancher in the southern part of the state and a member of the New Mexico National Guard's Battery A, who participated in many of the final battles of World War I. It is available in paperback and ebook through many online booksellers and directly from the author.

A Blaze of Poppies is an historical novel that tells the story of a New Mexico rancher in the southern part of the state and a member of the New Mexico National Guard's Battery A, who participated in many of the final battles of World War I. It is available in paperback and ebook through many online booksellers and directly from the author.

This past Christmas, I got two treasures from her that will undoubtably work their way into one of my novels. I’m sharing them with you and hope that they interest and excite you as much as they did me.

The first gift was a little brass box with an emblem that read “Gott Mit Uns” over a picture of a crown. After a little research, I discovered that Gott Mit Uns is German for God with us, and was a slogan used by the German army in World War I. The crown is the imperial crown of the Second Reich, and is described both as German and as Prussian online.

The first gift was a little brass box with an emblem that read “Gott Mit Uns” over a picture of a crown. After a little research, I discovered that Gott Mit Uns is German for God with us, and was a slogan used by the German army in World War I. The crown is the imperial crown of the Second Reich, and is described both as German and as Prussian online. The emblem on the box originally graced a belt buckle on a uniform. Here is a picture of one still attached.

So how did this emblem get placed on a brass box? The answer is an interesting bit of World War I history. Most people know that World War I is notable as the war in which both sides hunkered down in trenches along a front that became unmovable. Soldiers spent many weary months hunkered down in the mud, waiting to go “over the top” and attack the other side. The waiting grew monotonous.

So how did this emblem get placed on a brass box? The answer is an interesting bit of World War I history. Most people know that World War I is notable as the war in which both sides hunkered down in trenches along a front that became unmovable. Soldiers spent many weary months hunkered down in the mud, waiting to go “over the top” and attack the other side. The waiting grew monotonous.

To counter the boredom, soldiers found things to do to occupy their time. They had to use what they had at hand, and once one creative soldier had invented a form of art, it seems all his buddies copied it. The thousands of examples of vases made from shell casings, each unique in its decorations, attests to the hundreds of thousands of shells that flew over the trenches.

Sometimes what was lying around was pieces of uniforms. The belt buckle on a German uniform is exactly the right size to be made into a match box. The one I have has a lid that separates from the box. Others I found online were hinged or were squared off tubes with open ends. On some, the smooth brass had been deckled or worked into ridges. I do not know if the top of the box is part of the original belt buckle or if it was fashioned from a fragment of a shell casing. Either way, I can imagine a soldier hunkered down in the cold and damp, intently working on a bit he picked up in no man’s land to turn it into a little trinket for his loved ones back home.

The second treasure my sister gave me is a little, paperback book entitled History and Rhymes of the Lost Battalion, by “Buck Private” McCollum. Lee Charles McCollum self-published a 32-page volume of poetry by that name in 1919. That edition included sketches by Franklin Sly, another veteran of the American Expeditionary Force that went to Europe in 1918. Pt. McCollum saw action in France in many of the same areas as the famous Lost Battalion, but he is not listed on the unit's roster. Whether that means he wrote under a nom de plume was something I was not able to ascertain. The books was again published in 1919, 1921, 1922, and 1929, by which time Franklin Sly had passed away and another veteran, and Tolman R. Reamer, had completed artwork. The little volume grew over time. By 1939 it was up to 140 pages and included stories, remembrances by some of the key figures in the fight, pictures and tributes both to the Battalion and to its commander, Lt. Col. Charles Whittlesey, who had passed away in 1921. Over 700,000 copies of the various editions were sold.

The volume tells the story of Battalion 1 of the 77th Division, which pushed hard into the Argonne Forest and found itself cut off from the rest of the American forces.

The volume tells the story of Battalion 1 of the 77th Division, which pushed hard into the Argonne Forest and found itself cut off from the rest of the American forces.On the morning of October 3, 1918, Companies A, B, C, E, and H of the 808th Infantry, the 308th Infantry’s Company H, Company K of the 307th Infantry and Companies C and of 306th Machine Gun Battalion, all members of the Seventy-Seventh Division, were cut off from the other American forces near Charlevoix, in the Argonne Forest, and surrounded by a superior number of Germans. For four days, the approximately 550 men, under command of Major Charles W. Whittlesey managed to survive without food and with a dwindling supply of ammunition, fending off enemy machine gun, rifle, trench mortar, and grenade fire and some friendly fire from their own artillery. When they were finally reconnected with the main American force, only 194 of the officers and men were able to walk out of the position. 107 had been killed.

McCollum’s poems are about that experience, plus other observations in war, including poems about his gas mask and about kissing a French girl. Some are cute and sweet, while others are sad elegies to friends now dead. It’s a great volume for anyone interested in the experience of American doughboys.

I’m thinking I need to write a sequel to my WWI novel, a Blaze of Poppies, with a character who was in the Lost Battalion and now carries around a matchbox as a memento.

What do you think? Is that a story you'd like to read? If I ever write it, you can thank my sister.

A Blaze of Poppies is an historical novel that tells the story of a New Mexico rancher in the southern part of the state and a member of the New Mexico National Guard's Battery A, who participated in many of the final battles of World War I. It is available in paperback and ebook through many online booksellers and directly from the author.

A Blaze of Poppies is an historical novel that tells the story of a New Mexico rancher in the southern part of the state and a member of the New Mexico National Guard's Battery A, who participated in many of the final battles of World War I. It is available in paperback and ebook through many online booksellers and directly from the author.

Published on January 10, 2024 23:00

January 4, 2024

A Month in Maine

I am beginning the new year of 2024 far from home, in Maine. I arrived here the day before New Year’s Eve, and plan to stay a month, more or less. So far, a week into my time here, I find there’s a lot of differences between my home in the mountains of New Mexico and here, but there’s a lot of similarities, too.

Here in Maine, I am housesitting for a colleague of my son, who’s gone to Australia for an extended vacation. His house is nestled on a lake, in a neighborhood that, like my own in New Mexico, has few year-round residents. Most of the homes here are summer retreats. Many of the homes surrounding mine back in New Mexico are second homes, visited only a few weeks out of the year. The lake sits in a woods and, like my home, is remote enough that google maps has trouble finding it. Both houses are surrounded by trees. Mine are ponderosas and pinons. I really don’t know what all the trees here in Maine are, but many seem to be oaks and other deciduous species, and many of the conifers are some kind of fir.

I packed my snowshoes for the trip to Maine, expecting tall drifts of the white stuff everywhere. Turns out, there’s been more snow in the New Mexico mountains, where we’ve gotten perhaps 18” so far this year, than in Maine, which got a dusting one day in November and has seen nothing but rain since. Folks assure me that it’s coming, though.

Despite the lack of snow, what really sets the two properties apart is water. Besides being next to a lake here, I find water every time I leave the house. The woods are full of small streams and rivulets. The potholes on the roads are full of it. Even where the water isn’t standing or running, the ground is boggy. In New Mexico, small streams are a seasonal pleasure, appearing with the spring run off and again for a short period after a monsoon storm.

And the cold really gets to me. Although the temperatures thus far haven’t been too different from the ones I experienced out west, numbers can be deceiving. In Albuquerque, where the air is dry and thin, the temperature drops precipitously once the sun goes down, then rises during the day. It’s not uncommon to see morning temps of 16° followed by afternoons in the 40s. Here in Maine, the humid air makes the cold feel much sharper. Today I waited until after lunch, when the temperature had risen from a low of 25° to a high of 35°. It still felt really cold. My phone verified it, telling me that the air had a “real feel” of 21°. I’m not sure the tips of my fingers will ever thaw out.

But the cold is worth it. Being here gives me time to visit with the grandkids, and time to write. While I am sure I’ll never become a full-time resident here, it’s nice to join the ranks of Robert McCloskey, Stephen King, Edna St Vincent Millay, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and other literary illuminati, if only for just a month.

While not of the same caliber as the writers mentioned above, Jennifer Bohnhoff does her best to create interesting historical and contemporary novels for middle grade through adult readers. Many are set in New Mexico. For more information about her and her books, see her website.

While not of the same caliber as the writers mentioned above, Jennifer Bohnhoff does her best to create interesting historical and contemporary novels for middle grade through adult readers. Many are set in New Mexico. For more information about her and her books, see her website.

Here in Maine, I am housesitting for a colleague of my son, who’s gone to Australia for an extended vacation. His house is nestled on a lake, in a neighborhood that, like my own in New Mexico, has few year-round residents. Most of the homes here are summer retreats. Many of the homes surrounding mine back in New Mexico are second homes, visited only a few weeks out of the year. The lake sits in a woods and, like my home, is remote enough that google maps has trouble finding it. Both houses are surrounded by trees. Mine are ponderosas and pinons. I really don’t know what all the trees here in Maine are, but many seem to be oaks and other deciduous species, and many of the conifers are some kind of fir.

I packed my snowshoes for the trip to Maine, expecting tall drifts of the white stuff everywhere. Turns out, there’s been more snow in the New Mexico mountains, where we’ve gotten perhaps 18” so far this year, than in Maine, which got a dusting one day in November and has seen nothing but rain since. Folks assure me that it’s coming, though.

Despite the lack of snow, what really sets the two properties apart is water. Besides being next to a lake here, I find water every time I leave the house. The woods are full of small streams and rivulets. The potholes on the roads are full of it. Even where the water isn’t standing or running, the ground is boggy. In New Mexico, small streams are a seasonal pleasure, appearing with the spring run off and again for a short period after a monsoon storm.

And the cold really gets to me. Although the temperatures thus far haven’t been too different from the ones I experienced out west, numbers can be deceiving. In Albuquerque, where the air is dry and thin, the temperature drops precipitously once the sun goes down, then rises during the day. It’s not uncommon to see morning temps of 16° followed by afternoons in the 40s. Here in Maine, the humid air makes the cold feel much sharper. Today I waited until after lunch, when the temperature had risen from a low of 25° to a high of 35°. It still felt really cold. My phone verified it, telling me that the air had a “real feel” of 21°. I’m not sure the tips of my fingers will ever thaw out.

But the cold is worth it. Being here gives me time to visit with the grandkids, and time to write. While I am sure I’ll never become a full-time resident here, it’s nice to join the ranks of Robert McCloskey, Stephen King, Edna St Vincent Millay, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and other literary illuminati, if only for just a month.

While not of the same caliber as the writers mentioned above, Jennifer Bohnhoff does her best to create interesting historical and contemporary novels for middle grade through adult readers. Many are set in New Mexico. For more information about her and her books, see her website.

While not of the same caliber as the writers mentioned above, Jennifer Bohnhoff does her best to create interesting historical and contemporary novels for middle grade through adult readers. Many are set in New Mexico. For more information about her and her books, see her website.

Published on January 04, 2024 13:20