Jennifer Bohnhoff's Blog, page 7

October 30, 2024

Code Talkers: Heroes of the Spoken Word

As we enter November, it is fitting that we remember the American soldiers who fought for our freedom. Some of them fought not with guns and grenades, but with words. Our code talkers helped the Army keep its secrets, so that more of our soldiers came home to be Veterans, recognized on Veterans Day, November 11.

What we call Veterans Day began as Armistice Day, the day that World War I officially ended in 1918.

At the time that the United States entered World War I in 1917, one-third of the Native population was not recognized by the U.S. government as American citizens. Despite this fact, 12,000 Native Americans volunteered for military service. Some Native Soldiers joined to gain respect as warriors. Others joined because they believed it would prove their patriotism and help them receive citizenship, or to seek a better life for themselves and their families. Few knew that their Native languages would play an important role in the Great War. Code talking began in World War I, after the U.S. Army realized that the Germans were able to quickly intercept and translate messages sent in plain English. In September 1918, during the Second Battle of the Somme, the 105th Field Artillery Battalion, 30th Infantry Division used a group of Eastern Band Cherokees, to send messages between Allied troops in their Native language. The Germans were not able to translate these messages, keeping the Allied force’s locations and intentions secret. Although this is the earliest documented use of Native Code Talkers by the U.S. Army, anecdotal evidence suggests the Ho-Chunk used their Native language in code in early 1918.

The Cherokee Code Talkers continued their work until the end of the war. Soldiers from the Assiniboine, Comanche, Crow, Hopi, Lakota, Meskwaki (also known as Fox Indians), Mohawk, Choctaw, Seminole, Creek and Tlingit nations were also used. Col. Alfred Wainwright Bloor, commander of the 142nd Infantry, 36th Infantry Division, later stated that his regiment, possessed a company of Indians who spoke twenty-six different languages or dialects, only four or five of which were ever written. This made it almost impossible for Germans to translate. Choctaw code talkers in training during World War I (Photo: Oklahoma Historical Society) The best documented group of World War I Code Talkers are the 16 Choctaw Soldiers from the 142nd and the two from the 143rd Infantries. During an attack that ran from October 26 to 28, 1918, Colonel Bloor had these coordinate attacks, including an artillery attack that took the Germans by surprise and resulted in a much-needed victory for the 36th Infantry Division.

Choctaw code talkers in training during World War I (Photo: Oklahoma Historical Society) The best documented group of World War I Code Talkers are the 16 Choctaw Soldiers from the 142nd and the two from the 143rd Infantries. During an attack that ran from October 26 to 28, 1918, Colonel Bloor had these coordinate attacks, including an artillery attack that took the Germans by surprise and resulted in a much-needed victory for the 36th Infantry Division.

The most famous of the World War I Native Code Talkers was Pvt. Joseph Oklahombi a Choctaw Code Talker with Company D, 1st Battalion, 141st Regiment. During October 1918, Oklahombi and the 23 fellow soldiers in his company came across a German machine gun nest while they were cut off behind enemy lines. Oklahombi and his company rushed to the enemy’s position, captured it, and used the captured machine gun to pin down the enemy. Four days later, the 171 German soldiers surrendered. Oklahombi was awarded the World War I Victory Medal and a Silver Citation Star for his bravery, and France awarded him the Croix de Guerre. Joseph Oklahombi in uniform, sitting with John Golombie and Czarina Colbert Conlan at Oklahombi’s home near Wright City, Oklahoma, May 12, 1921. Photographer: Hopkins | Oklahoma Historical Society The use of Native Americans as Code Talkers did not end when World War I ended. Several hundred Navajo served as Code Talkers in World War II, many in the Pacific Their language proved unintelligible and unbreakable for Japanese cryptographers, and their radio transmissions were much faster than standard machine-aided shackle encryption. Bill H. Toledo was just 18 years old when he enlisted in the Marine Corps. The Torreon, New Mexico native joined with his uncle Frank Toledo and his cousin Preston Toledo in October 1942. All three would become Code Talkers.

Joseph Oklahombi in uniform, sitting with John Golombie and Czarina Colbert Conlan at Oklahombi’s home near Wright City, Oklahoma, May 12, 1921. Photographer: Hopkins | Oklahoma Historical Society The use of Native Americans as Code Talkers did not end when World War I ended. Several hundred Navajo served as Code Talkers in World War II, many in the Pacific Their language proved unintelligible and unbreakable for Japanese cryptographers, and their radio transmissions were much faster than standard machine-aided shackle encryption. Bill H. Toledo was just 18 years old when he enlisted in the Marine Corps. The Torreon, New Mexico native joined with his uncle Frank Toledo and his cousin Preston Toledo in October 1942. All three would become Code Talkers.  Navajo code talkers Preston and Frank Toledo (Photo: National Archives) Photographer: Ashman. Toledo first showed how valuable the Navajo Code was on Bougainville. He also sent messages on Guam and Iwo Jima before he earned enough points to return to the states. Serving was not easy. Some of his fellow Marines made racist comments about Native Americans. After the Battle of Bougainville, when a Marine mistook him for a Japanese soldier wearing a captured American uniform and nearly killed him, Toledo was also assigned a bodyguard.

Navajo code talkers Preston and Frank Toledo (Photo: National Archives) Photographer: Ashman. Toledo first showed how valuable the Navajo Code was on Bougainville. He also sent messages on Guam and Iwo Jima before he earned enough points to return to the states. Serving was not easy. Some of his fellow Marines made racist comments about Native Americans. After the Battle of Bougainville, when a Marine mistook him for a Japanese soldier wearing a captured American uniform and nearly killed him, Toledo was also assigned a bodyguard.

As they had in World War I, other tribes continued to serve as Code Talkers in World War II. Comanche code talkers during World War II (Photo: U.S. Army) Not all soldiers fight with guns and grenades.Words, too, can be a powerful tool in war. But words were not enough for the Native Soldiers who joined to gain the respect of their fellow Americans in the hope that they would receive citizenship. They would have to wait for legal actions. The Snyder Act, also known as the Indian Citizenship Act, which conferred citizenship on Native American people, didn't pass until June 2, 1924, and Native American's right to vote in U.S. elections wasn't recognized until 1948, in the landmark case of Trujillo v. Garley, when an Isleta Puebloan from New Mexico sued for the right to vote. Utah became the last state to remove formal barriers, when they did so in 1962. Still, some states have voter ID laws which require an ID with a physical address. Many people living on reservations do not have physical addresses, only post office boxes.

Comanche code talkers during World War II (Photo: U.S. Army) Not all soldiers fight with guns and grenades.Words, too, can be a powerful tool in war. But words were not enough for the Native Soldiers who joined to gain the respect of their fellow Americans in the hope that they would receive citizenship. They would have to wait for legal actions. The Snyder Act, also known as the Indian Citizenship Act, which conferred citizenship on Native American people, didn't pass until June 2, 1924, and Native American's right to vote in U.S. elections wasn't recognized until 1948, in the landmark case of Trujillo v. Garley, when an Isleta Puebloan from New Mexico sued for the right to vote. Utah became the last state to remove formal barriers, when they did so in 1962. Still, some states have voter ID laws which require an ID with a physical address. Many people living on reservations do not have physical addresses, only post office boxes.

This Veteran's Day, let's remember those soldiers who did not fight with guns, but with words, and all the others who fought to protect freedoms that they did not share in. Jennifer Bohnhoff is a retired educator who now writes historical fiction for middle grade through adult readers. You can read about her and her books here, on her website.

What we call Veterans Day began as Armistice Day, the day that World War I officially ended in 1918.

At the time that the United States entered World War I in 1917, one-third of the Native population was not recognized by the U.S. government as American citizens. Despite this fact, 12,000 Native Americans volunteered for military service. Some Native Soldiers joined to gain respect as warriors. Others joined because they believed it would prove their patriotism and help them receive citizenship, or to seek a better life for themselves and their families. Few knew that their Native languages would play an important role in the Great War. Code talking began in World War I, after the U.S. Army realized that the Germans were able to quickly intercept and translate messages sent in plain English. In September 1918, during the Second Battle of the Somme, the 105th Field Artillery Battalion, 30th Infantry Division used a group of Eastern Band Cherokees, to send messages between Allied troops in their Native language. The Germans were not able to translate these messages, keeping the Allied force’s locations and intentions secret. Although this is the earliest documented use of Native Code Talkers by the U.S. Army, anecdotal evidence suggests the Ho-Chunk used their Native language in code in early 1918.

The Cherokee Code Talkers continued their work until the end of the war. Soldiers from the Assiniboine, Comanche, Crow, Hopi, Lakota, Meskwaki (also known as Fox Indians), Mohawk, Choctaw, Seminole, Creek and Tlingit nations were also used. Col. Alfred Wainwright Bloor, commander of the 142nd Infantry, 36th Infantry Division, later stated that his regiment, possessed a company of Indians who spoke twenty-six different languages or dialects, only four or five of which were ever written. This made it almost impossible for Germans to translate.

Choctaw code talkers in training during World War I (Photo: Oklahoma Historical Society) The best documented group of World War I Code Talkers are the 16 Choctaw Soldiers from the 142nd and the two from the 143rd Infantries. During an attack that ran from October 26 to 28, 1918, Colonel Bloor had these coordinate attacks, including an artillery attack that took the Germans by surprise and resulted in a much-needed victory for the 36th Infantry Division.

Choctaw code talkers in training during World War I (Photo: Oklahoma Historical Society) The best documented group of World War I Code Talkers are the 16 Choctaw Soldiers from the 142nd and the two from the 143rd Infantries. During an attack that ran from October 26 to 28, 1918, Colonel Bloor had these coordinate attacks, including an artillery attack that took the Germans by surprise and resulted in a much-needed victory for the 36th Infantry Division.The most famous of the World War I Native Code Talkers was Pvt. Joseph Oklahombi a Choctaw Code Talker with Company D, 1st Battalion, 141st Regiment. During October 1918, Oklahombi and the 23 fellow soldiers in his company came across a German machine gun nest while they were cut off behind enemy lines. Oklahombi and his company rushed to the enemy’s position, captured it, and used the captured machine gun to pin down the enemy. Four days later, the 171 German soldiers surrendered. Oklahombi was awarded the World War I Victory Medal and a Silver Citation Star for his bravery, and France awarded him the Croix de Guerre.

Joseph Oklahombi in uniform, sitting with John Golombie and Czarina Colbert Conlan at Oklahombi’s home near Wright City, Oklahoma, May 12, 1921. Photographer: Hopkins | Oklahoma Historical Society The use of Native Americans as Code Talkers did not end when World War I ended. Several hundred Navajo served as Code Talkers in World War II, many in the Pacific Their language proved unintelligible and unbreakable for Japanese cryptographers, and their radio transmissions were much faster than standard machine-aided shackle encryption. Bill H. Toledo was just 18 years old when he enlisted in the Marine Corps. The Torreon, New Mexico native joined with his uncle Frank Toledo and his cousin Preston Toledo in October 1942. All three would become Code Talkers.

Joseph Oklahombi in uniform, sitting with John Golombie and Czarina Colbert Conlan at Oklahombi’s home near Wright City, Oklahoma, May 12, 1921. Photographer: Hopkins | Oklahoma Historical Society The use of Native Americans as Code Talkers did not end when World War I ended. Several hundred Navajo served as Code Talkers in World War II, many in the Pacific Their language proved unintelligible and unbreakable for Japanese cryptographers, and their radio transmissions were much faster than standard machine-aided shackle encryption. Bill H. Toledo was just 18 years old when he enlisted in the Marine Corps. The Torreon, New Mexico native joined with his uncle Frank Toledo and his cousin Preston Toledo in October 1942. All three would become Code Talkers.  Navajo code talkers Preston and Frank Toledo (Photo: National Archives) Photographer: Ashman. Toledo first showed how valuable the Navajo Code was on Bougainville. He also sent messages on Guam and Iwo Jima before he earned enough points to return to the states. Serving was not easy. Some of his fellow Marines made racist comments about Native Americans. After the Battle of Bougainville, when a Marine mistook him for a Japanese soldier wearing a captured American uniform and nearly killed him, Toledo was also assigned a bodyguard.

Navajo code talkers Preston and Frank Toledo (Photo: National Archives) Photographer: Ashman. Toledo first showed how valuable the Navajo Code was on Bougainville. He also sent messages on Guam and Iwo Jima before he earned enough points to return to the states. Serving was not easy. Some of his fellow Marines made racist comments about Native Americans. After the Battle of Bougainville, when a Marine mistook him for a Japanese soldier wearing a captured American uniform and nearly killed him, Toledo was also assigned a bodyguard. As they had in World War I, other tribes continued to serve as Code Talkers in World War II.

Comanche code talkers during World War II (Photo: U.S. Army) Not all soldiers fight with guns and grenades.Words, too, can be a powerful tool in war. But words were not enough for the Native Soldiers who joined to gain the respect of their fellow Americans in the hope that they would receive citizenship. They would have to wait for legal actions. The Snyder Act, also known as the Indian Citizenship Act, which conferred citizenship on Native American people, didn't pass until June 2, 1924, and Native American's right to vote in U.S. elections wasn't recognized until 1948, in the landmark case of Trujillo v. Garley, when an Isleta Puebloan from New Mexico sued for the right to vote. Utah became the last state to remove formal barriers, when they did so in 1962. Still, some states have voter ID laws which require an ID with a physical address. Many people living on reservations do not have physical addresses, only post office boxes.

Comanche code talkers during World War II (Photo: U.S. Army) Not all soldiers fight with guns and grenades.Words, too, can be a powerful tool in war. But words were not enough for the Native Soldiers who joined to gain the respect of their fellow Americans in the hope that they would receive citizenship. They would have to wait for legal actions. The Snyder Act, also known as the Indian Citizenship Act, which conferred citizenship on Native American people, didn't pass until June 2, 1924, and Native American's right to vote in U.S. elections wasn't recognized until 1948, in the landmark case of Trujillo v. Garley, when an Isleta Puebloan from New Mexico sued for the right to vote. Utah became the last state to remove formal barriers, when they did so in 1962. Still, some states have voter ID laws which require an ID with a physical address. Many people living on reservations do not have physical addresses, only post office boxes. This Veteran's Day, let's remember those soldiers who did not fight with guns, but with words, and all the others who fought to protect freedoms that they did not share in. Jennifer Bohnhoff is a retired educator who now writes historical fiction for middle grade through adult readers. You can read about her and her books here, on her website.

Published on October 30, 2024 23:00

October 22, 2024

Touring Pecos National Monument -- The Glorieta Battlefield Interpretive Trail

Some Civil War Battlefields have become national parks or tourist attractions, and they have kiosks and guidebooks to walk interested people through the events that happened there. Pecos National Monument strived to do a similar thing with its Glorieta Battlefield Interpretive Trail. Unfortunately for history fans. Much of the battlefield is buried under the asphalt of I-25, or is in private hands. While the Park Service has published a little guide to the interpretive trail, I'd like to add some information about areas of the battle that are outside the Park's boundaries to supplement the park's guide.

To follow along, begin driving I-25 east as it leaves Santa Fe.

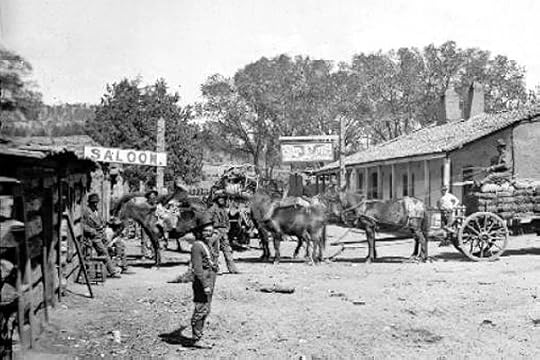

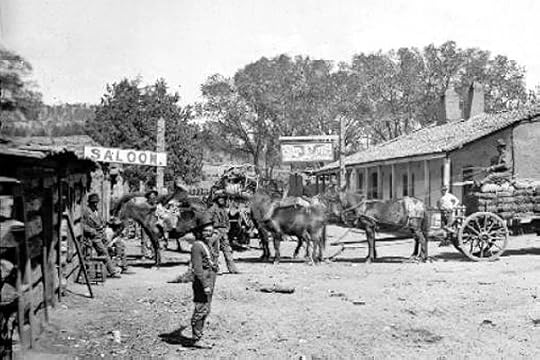

The Battle of Glorieta Pass could just as easily be called The Battle of Three Ranches, because three different ranches played prominent roles in the conflict. The first, Johnson’s Ranch, is no longer standing. This picture is what the ranch looked like in 1914. It would have been located on I-40, a little east of the turn off for Canoncito.

The Battle of Glorieta Pass could just as easily be called The Battle of Three Ranches, because three different ranches played prominent roles in the conflict. The first, Johnson’s Ranch, is no longer standing. This picture is what the ranch looked like in 1914. It would have been located on I-40, a little east of the turn off for Canoncito.

Anthony D. Johnson, the owner of the ranch, had served in the Union Army. A Missouri native, he had bought the ranch with his severance pay, married a local woman named Cruz, and had fathered five children. Johnson made his living keeping travelers along the Santa Fe trail, and transporting supplies. When the Confederates arrived, he and his family fled into the hills just north of the ranch, where they could watch what was happening below. They camped until it was safe to return home. Johnson later transported wounded Confederates back to Santa Fe. He later moved his family to Trinidad, Colorado, where he died a mysterious death. As you drive past the exit, you will see an old church on the left (north). That is Nuestra Señora de la Luz Church, built in 1880, it has a fascinating old cemetery full of unusual molded cement tombstones.

As you drive past the exit, you will see an old church on the left (north). That is Nuestra Señora de la Luz Church, built in 1880, it has a fascinating old cemetery full of unusual molded cement tombstones.

If you drive on the little frontage road in front of the church, it turns north and becomes Johnson Ranch Road.

The ranch itself was bulldozed in 1967 so that the interstate could go through.

Confederate Major Charles L. Pyron (1819–1869) encamped at Johnson’s Ranch with 200-300 men from the Texas Volunteers 5th Regiment. As he waited for other Confederate units to catch up, he sent a scouting party up into Glorieta Pass.

Confederate Major Charles L. Pyron (1819–1869) encamped at Johnson’s Ranch with 200-300 men from the Texas Volunteers 5th Regiment. As he waited for other Confederate units to catch up, he sent a scouting party up into Glorieta Pass.

The first day of the battle took place just east of Johnson’s Ranch, in Apache Canyon. At the time of the Civil War, Apache Canyon had a deep arroyo that crossed the road, and there was a bridge over it.

Exit I-40 at exit 299. Cross over the interstate, then turn right to continue towards Pecos on state road 50. After about a mile, you will pass an old adobe that’s on the north side of the road. This is all that remains of Pigeon’s Ranch.

Exit I-40 at exit 299. Cross over the interstate, then turn right to continue towards Pecos on state road 50. After about a mile, you will pass an old adobe that’s on the north side of the road. This is all that remains of Pigeon’s Ranch.

Alexander Pigeon (or Valle. No one is really sure what his real name was, and there are legal documents using both) Was born in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1817. He came to New Mexico along the Santa Fe Trail, probably in the late 1830s. He lived in Santa Fe, making his living as a trader, gambler, and land speculator until 1852, when he bought a portion of an 1815 land grant for 5,275 pesos. He and his wife Carmen built a large adobe ranch home, an inn large enough to house 40 guests, a tavern, corrals, stables, granaries, and a water well. The Ranch remained a viable hotel until 1879, when the New Mexico and Southern Pacific Railroad constructed a railroad through the pass. It continued to be a tourist destination when route 66 went through the pass, but gave up the ghost after I-25 made it into a backwater. The black and white picture is by Ben Wittrock, and is dated 1880. Early in the morning of March 26, a Union scouting party led by Lt. George Nelson rode to Pigeon’s Ranch, where a very excited Pigeon told them that a Confederate Party had just passed, going east. The patrol doubled back and encountered the three Confederates, who in the gloom thought that the Union soldiers were Confederates. “Are you here to relieve us?” one of the Confederates called. Nelson yelled back. “Yes! We’re here to relieve you of your arms.” He then captured the men and brought them back to Kozlowski’s Ranch, where the Union troops were bivouacked.

He and his wife Carmen built a large adobe ranch home, an inn large enough to house 40 guests, a tavern, corrals, stables, granaries, and a water well. The Ranch remained a viable hotel until 1879, when the New Mexico and Southern Pacific Railroad constructed a railroad through the pass. It continued to be a tourist destination when route 66 went through the pass, but gave up the ghost after I-25 made it into a backwater. The black and white picture is by Ben Wittrock, and is dated 1880. Early in the morning of March 26, a Union scouting party led by Lt. George Nelson rode to Pigeon’s Ranch, where a very excited Pigeon told them that a Confederate Party had just passed, going east. The patrol doubled back and encountered the three Confederates, who in the gloom thought that the Union soldiers were Confederates. “Are you here to relieve us?” one of the Confederates called. Nelson yelled back. “Yes! We’re here to relieve you of your arms.” He then captured the men and brought them back to Kozlowski’s Ranch, where the Union troops were bivouacked.

Kozlowski’s Ranch is the third of the three ranches involved in the Battle of Glorieta Pass. Located on the western side of the pass, it was where Major John Chivington and a 418-man unit from the 1st Colorado Volunteers stopped, waiting for Colonel John Slough to bring the rest of the Union Troops down from Fort Union so they could capture Santa Fe. Martin Kozlowski came from Warsaw, Poland. Born in 1827, he fought in the 1848 revolution against the Prussians, then became a refugee in England, where married an Irish woman named Ellene. The two immigrated to American in 1853, and Martin enlisted in the First Dragoons, who were fighting Apaches in the Southwest. When he mustered out of the Army in 1858, he used his 160-acre government bounty land warrant to purchase his ranch. Kozlowski grew corn and raised livestock, but a lot of his livelihood came from accommodating for travelers on the Santa Fe trail. A big Union supporter, he was thrilled to host Chivington and his men.

Martin Kozlowski came from Warsaw, Poland. Born in 1827, he fought in the 1848 revolution against the Prussians, then became a refugee in England, where married an Irish woman named Ellene. The two immigrated to American in 1853, and Martin enlisted in the First Dragoons, who were fighting Apaches in the Southwest. When he mustered out of the Army in 1858, he used his 160-acre government bounty land warrant to purchase his ranch. Kozlowski grew corn and raised livestock, but a lot of his livelihood came from accommodating for travelers on the Santa Fe trail. A big Union supporter, he was thrilled to host Chivington and his men.

In 1925, the Kozlowski family sold the Ranch to Tex Austin, who renamed it the Forked Lightning Ranch. Tex used Martin’s old Trading Post as the Ranch headquarters. In 1941, "Buddy" Fogelson, a Texas oilman and rancher bought the ranch. He married Hollywood actress Greer Garson 8 years later. Garson donated the land to The Conservation Fund, who donated it to the federal government.

In 1925, the Kozlowski family sold the Ranch to Tex Austin, who renamed it the Forked Lightning Ranch. Tex used Martin’s old Trading Post as the Ranch headquarters. In 1941, "Buddy" Fogelson, a Texas oilman and rancher bought the ranch. He married Hollywood actress Greer Garson 8 years later. Garson donated the land to The Conservation Fund, who donated it to the federal government.

When you get to the Pecos Visitor Center, check to see if the Forked Lightning Ranch is open (it isn’t always open, but it has a nice little museum and is worth the visit.)

When the Union scouting party returned to Kozlowski’s Ranch on the morning of March 26, 1862, and Chivington learned that the Confederates were encamped only 9 miles away, he decided not to wait for Slough and the rest of the Union army to arrive. They reached the summit of the pass, close to where Glorietta Retreat now is, at around 2p.m, and quickly a 30-man Confederate advance force.

Excited by this, the Coloradans rushed into Apache Canyon. The two sides met about a mile and a half west of Pigeon’s Ranch, or six miles northeast of Johnson’s Ranch. The Confederates withdrew about a mile and a half, to a narrower section of the pass that could be better defended. They destroyed the bridge after crossing it. Chivington’s cavalry charged, leaping over the arroyo and sending the Confederates into a panic. They fled to a bend in the road, where they could hold off the Federals and prevent a complete rout. Chivington decided that they were too far from their supply base to risk another attack and fell back to Pigeon's Ranch. In this first day of battle, the Federals sustained 27 casualties (19 killed, five wounded, and three missing), and the Confederates lost 125 (16 killed, 30 wounded, and 79 captured or missing). This small engagement, no more than a two hour skirmish, marked the first Federal victory in the New Mexico Territory. Up to this point, Confederates had won every battle.

They fled to a bend in the road, where they could hold off the Federals and prevent a complete rout. Chivington decided that they were too far from their supply base to risk another attack and fell back to Pigeon's Ranch. In this first day of battle, the Federals sustained 27 casualties (19 killed, five wounded, and three missing), and the Confederates lost 125 (16 killed, 30 wounded, and 79 captured or missing). This small engagement, no more than a two hour skirmish, marked the first Federal victory in the New Mexico Territory. Up to this point, Confederates had won every battle.

Having lost about a third of his command, Pyron retreated back to Johnson’s Ranch. He sent a messenger to Lieutenant Colonel William R. Scurry’s column, which was about 16 miles south, at Galisteo. Chivington also sent a messenger, urging Colonel Slough to hurry southward. That evening, both sides called a truce to tend to their dead and wounded. The truce continued unbroken through the next day.

Stop in the Pecos National Monument Visitor Center. While you’re there, tour the museum. You can pick up a guide for the Ancestral Sites Trail, an easy gravel path that loops through the old pueblo and church. 1.25 mile, with an elevation Change of 80 ft. There is a free ranger guided tour from 10-11 am most days. Check the website for more information.

Also, get the gate code and map to get to the Glorieta Battlefield Trail. The trailhead is 7.5 miles away from the visitor center and behind a locked gate. It is an easy, gravel loop trail that is 2.25 miles around. You can buy a trail guide at the visitor center which will have different information that this guide. Glorieta Battlefield Trail doesn’t really encompass the entire battle, but some of the third day. I suggest you read the trail guide produced by the Park Service. Here are a few extra notes that might make the route a little more interesting.

Glorieta Battlefield Trail doesn’t really encompass the entire battle, but some of the third day. I suggest you read the trail guide produced by the Park Service. Here are a few extra notes that might make the route a little more interesting.

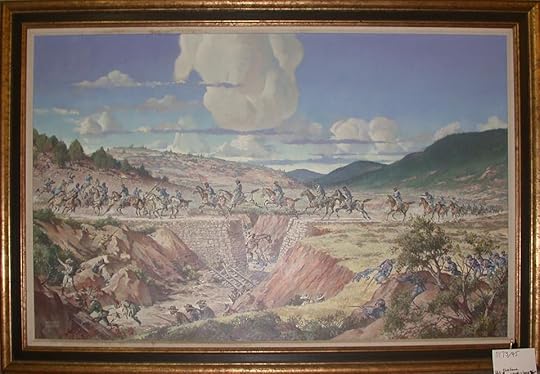

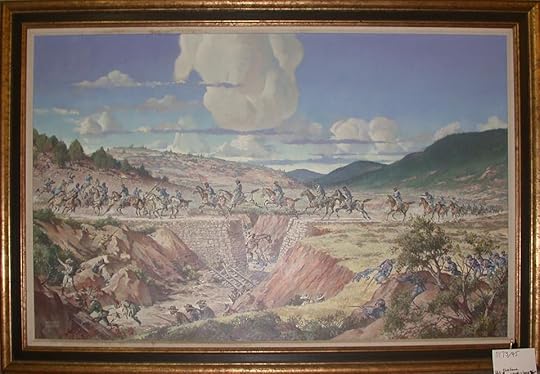

Marker 2: The trail isn’t set up in a way that presents the battle in order. The actual beginning of the battle occurred west of here. This is where the second part of the battle occurred. The Union had pulled back to here, Artillery Hill, to take advantage of the high ground.

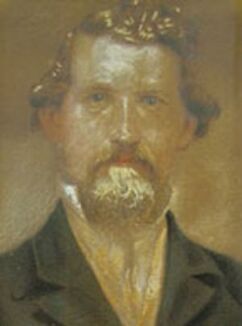

Confederate Major John Shropshire was a rich landowner who owned a 750 acre plantation and owned 61 slaves. Born in 1833 in Kentucky, both his parents died of cholera when he was just 3 years old. He was married and had one young son, Charles. He was a very tall man: I’ve seen 6’4” and 6’5”.

Shopshire led a flanking movement around the Union forces, then charged up the hill. He and 30 of his men were killed in the fight. One source I read said that Shropshire was shot between the eyes by a Union private named George W. Pierce. Another says that the top of his head was sheared off by a cannonball.

In June 1987 a man digging a foundation for a new house just across from the Pigeon Ranch discovered a the body. Archaeologists were called in. They discovered that the skeleton was of a 6’4” (or so) man, and the top of the skull was missing. Shropshire was reburied with military honors at his birthplace in Kentucky, alongside his parents in 1990. Archaeologists then discovered a grave with 30 skeletons, which were reburied in the Santa Fe Veterans cemetery. Marker 3 Is where the battle actually began.

Marker 3 Is where the battle actually began.

John Slough had decided to use a pincer movement, sending John Chivington and two infantry battalions up Glorieta Mesa, with orders to circle around the Confederates and attack them from behind. He therefore had less men with him to attack the front of the Confederate forces.

Scurry believed the Union force was retreating to Fort Union. He decided to go after them, leaving his sick and wounded, one cannon, and a small guard with the supply wagons at Johnson's Ranch. He advanced up the canyon with around 1,000 men.

Slough ran into the Confederates here about 11:00 am. Thirty minutes later, the Confederates' numerical superiority managed to push back the Union men to Marker 2’s position.

Marker 4

At the same time as Shropshire was storming Artillery Hill, Scurry sent Henry Raguet to attack the Union right, and around 3:00 pm they succeeded in outflanking the Union right and taking what thereafter became known as Sharpshooters Ridge. Raguet was killed, but the ridge allowed Confederate riflemen to pick off Union artillerymen and infantry below them at Piegeon’s Ranch, making the Union position untenable.

Slough was convinced that his own men were firing on him at Pigeon’s Ranch. This caused him to resign his commission and return to Colorado within days of the battle.

Marker 9 Alfred B. Peticolas kept a multi-book journal of his times with Sibley’s Battalion which included sketches of the places he’d seen. Unfortunately, some of the books were burned at Johnson’s ranch. The Confederates were poorly provisioned, and, coming from Texas, unprepared for how cold New Mexico would be. Many of them wore coats and pants scavenged from Union dead. (The wore the belts upside down, so the US on the belt buckle looked like SN, which they said stood for Southern Nation. This helped distinguish them from Union Soldiers – if you looked close enough. Obviously, Lt. Col Tappan did not.

Marker 9 Alfred B. Peticolas kept a multi-book journal of his times with Sibley’s Battalion which included sketches of the places he’d seen. Unfortunately, some of the books were burned at Johnson’s ranch. The Confederates were poorly provisioned, and, coming from Texas, unprepared for how cold New Mexico would be. Many of them wore coats and pants scavenged from Union dead. (The wore the belts upside down, so the US on the belt buckle looked like SN, which they said stood for Southern Nation. This helped distinguish them from Union Soldiers – if you looked close enough. Obviously, Lt. Col Tappan did not.

Lt. Col Samuel F. Tappan was raised in Massachusetts and came from a family of famous abolitionists. A man of high principles, he was the ranking officer and acting colonel when Slough resigned a few days after the victory at Glorieta Pass, but voluntarily relinquished his seniority rights and joined in signing a petition from among the men of the First Colorado to elevate Chivington. He had reason to regret this decision. Tappan headed the military commission that investigated Colonel Chivington for his role in the Sand Creek massacre. He and Gen. Sherman were the two commission members who finalized the Treaty of Bosque Redondo, which allowed the Navajos to return to their homelands, and he worked to assure the rights of the Plains Indians. Marker 10 Slough reluctantly ordered a retreat, and Tappan and his artillery on Artillery Hill covered it. Slough reformed his line a half-mile east of Pigeon's Ranch, where skirmishing continued until dusk. The Union men finally retreated to Kozlowski's Ranch, leaving the Confederates in possession of the battlefield.

Lt. Col Samuel F. Tappan was raised in Massachusetts and came from a family of famous abolitionists. A man of high principles, he was the ranking officer and acting colonel when Slough resigned a few days after the victory at Glorieta Pass, but voluntarily relinquished his seniority rights and joined in signing a petition from among the men of the First Colorado to elevate Chivington. He had reason to regret this decision. Tappan headed the military commission that investigated Colonel Chivington for his role in the Sand Creek massacre. He and Gen. Sherman were the two commission members who finalized the Treaty of Bosque Redondo, which allowed the Navajos to return to their homelands, and he worked to assure the rights of the Plains Indians. Marker 10 Slough reluctantly ordered a retreat, and Tappan and his artillery on Artillery Hill covered it. Slough reformed his line a half-mile east of Pigeon's Ranch, where skirmishing continued until dusk. The Union men finally retreated to Kozlowski's Ranch, leaving the Confederates in possession of the battlefield.

Control of the Battlefield is one of the factors in deciding who won. Scurry and the Confederates technically won the battle and, had they not lost their supplies, might have been able to push the Union troops back further in another day of fighting. Furthermore, Col. Tom Green’s men, who’d taken an alternative route south of the mountain pass, might have been able to swing around the mountain’s eastern edge and perform the pincer act on the Union Troops that Slough had intended to perform on the Confederates. The Confederate Army might then have been able to push on to the lightly guarded Fort Union, where they could have gotten enough supplies and ammunition to continue on to Colorado, and then California. With gold, and the deep ports of Los Angeles and San Diego, the war might have ended very differently.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is the author of Rebels Along the Rio Grande, a trilogy of historical novels based on New Mexico during the Civil War. The second book in the series, The Worst Enemy, includes the Battle of Glorieta Pass.

If you are planning to visit Pecos National Monument and want a printable version of this blog, click here.

To follow along, begin driving I-25 east as it leaves Santa Fe.

The Battle of Glorieta Pass could just as easily be called The Battle of Three Ranches, because three different ranches played prominent roles in the conflict. The first, Johnson’s Ranch, is no longer standing. This picture is what the ranch looked like in 1914. It would have been located on I-40, a little east of the turn off for Canoncito.

The Battle of Glorieta Pass could just as easily be called The Battle of Three Ranches, because three different ranches played prominent roles in the conflict. The first, Johnson’s Ranch, is no longer standing. This picture is what the ranch looked like in 1914. It would have been located on I-40, a little east of the turn off for Canoncito.

Anthony D. Johnson, the owner of the ranch, had served in the Union Army. A Missouri native, he had bought the ranch with his severance pay, married a local woman named Cruz, and had fathered five children. Johnson made his living keeping travelers along the Santa Fe trail, and transporting supplies. When the Confederates arrived, he and his family fled into the hills just north of the ranch, where they could watch what was happening below. They camped until it was safe to return home. Johnson later transported wounded Confederates back to Santa Fe. He later moved his family to Trinidad, Colorado, where he died a mysterious death.

As you drive past the exit, you will see an old church on the left (north). That is Nuestra Señora de la Luz Church, built in 1880, it has a fascinating old cemetery full of unusual molded cement tombstones.

As you drive past the exit, you will see an old church on the left (north). That is Nuestra Señora de la Luz Church, built in 1880, it has a fascinating old cemetery full of unusual molded cement tombstones.If you drive on the little frontage road in front of the church, it turns north and becomes Johnson Ranch Road.

The ranch itself was bulldozed in 1967 so that the interstate could go through.

Confederate Major Charles L. Pyron (1819–1869) encamped at Johnson’s Ranch with 200-300 men from the Texas Volunteers 5th Regiment. As he waited for other Confederate units to catch up, he sent a scouting party up into Glorieta Pass.

Confederate Major Charles L. Pyron (1819–1869) encamped at Johnson’s Ranch with 200-300 men from the Texas Volunteers 5th Regiment. As he waited for other Confederate units to catch up, he sent a scouting party up into Glorieta Pass. The first day of the battle took place just east of Johnson’s Ranch, in Apache Canyon. At the time of the Civil War, Apache Canyon had a deep arroyo that crossed the road, and there was a bridge over it.

Exit I-40 at exit 299. Cross over the interstate, then turn right to continue towards Pecos on state road 50. After about a mile, you will pass an old adobe that’s on the north side of the road. This is all that remains of Pigeon’s Ranch.

Exit I-40 at exit 299. Cross over the interstate, then turn right to continue towards Pecos on state road 50. After about a mile, you will pass an old adobe that’s on the north side of the road. This is all that remains of Pigeon’s Ranch.Alexander Pigeon (or Valle. No one is really sure what his real name was, and there are legal documents using both) Was born in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1817. He came to New Mexico along the Santa Fe Trail, probably in the late 1830s. He lived in Santa Fe, making his living as a trader, gambler, and land speculator until 1852, when he bought a portion of an 1815 land grant for 5,275 pesos.

He and his wife Carmen built a large adobe ranch home, an inn large enough to house 40 guests, a tavern, corrals, stables, granaries, and a water well. The Ranch remained a viable hotel until 1879, when the New Mexico and Southern Pacific Railroad constructed a railroad through the pass. It continued to be a tourist destination when route 66 went through the pass, but gave up the ghost after I-25 made it into a backwater. The black and white picture is by Ben Wittrock, and is dated 1880. Early in the morning of March 26, a Union scouting party led by Lt. George Nelson rode to Pigeon’s Ranch, where a very excited Pigeon told them that a Confederate Party had just passed, going east. The patrol doubled back and encountered the three Confederates, who in the gloom thought that the Union soldiers were Confederates. “Are you here to relieve us?” one of the Confederates called. Nelson yelled back. “Yes! We’re here to relieve you of your arms.” He then captured the men and brought them back to Kozlowski’s Ranch, where the Union troops were bivouacked.

He and his wife Carmen built a large adobe ranch home, an inn large enough to house 40 guests, a tavern, corrals, stables, granaries, and a water well. The Ranch remained a viable hotel until 1879, when the New Mexico and Southern Pacific Railroad constructed a railroad through the pass. It continued to be a tourist destination when route 66 went through the pass, but gave up the ghost after I-25 made it into a backwater. The black and white picture is by Ben Wittrock, and is dated 1880. Early in the morning of March 26, a Union scouting party led by Lt. George Nelson rode to Pigeon’s Ranch, where a very excited Pigeon told them that a Confederate Party had just passed, going east. The patrol doubled back and encountered the three Confederates, who in the gloom thought that the Union soldiers were Confederates. “Are you here to relieve us?” one of the Confederates called. Nelson yelled back. “Yes! We’re here to relieve you of your arms.” He then captured the men and brought them back to Kozlowski’s Ranch, where the Union troops were bivouacked.Kozlowski’s Ranch is the third of the three ranches involved in the Battle of Glorieta Pass. Located on the western side of the pass, it was where Major John Chivington and a 418-man unit from the 1st Colorado Volunteers stopped, waiting for Colonel John Slough to bring the rest of the Union Troops down from Fort Union so they could capture Santa Fe.

Martin Kozlowski came from Warsaw, Poland. Born in 1827, he fought in the 1848 revolution against the Prussians, then became a refugee in England, where married an Irish woman named Ellene. The two immigrated to American in 1853, and Martin enlisted in the First Dragoons, who were fighting Apaches in the Southwest. When he mustered out of the Army in 1858, he used his 160-acre government bounty land warrant to purchase his ranch. Kozlowski grew corn and raised livestock, but a lot of his livelihood came from accommodating for travelers on the Santa Fe trail. A big Union supporter, he was thrilled to host Chivington and his men.

Martin Kozlowski came from Warsaw, Poland. Born in 1827, he fought in the 1848 revolution against the Prussians, then became a refugee in England, where married an Irish woman named Ellene. The two immigrated to American in 1853, and Martin enlisted in the First Dragoons, who were fighting Apaches in the Southwest. When he mustered out of the Army in 1858, he used his 160-acre government bounty land warrant to purchase his ranch. Kozlowski grew corn and raised livestock, but a lot of his livelihood came from accommodating for travelers on the Santa Fe trail. A big Union supporter, he was thrilled to host Chivington and his men.  In 1925, the Kozlowski family sold the Ranch to Tex Austin, who renamed it the Forked Lightning Ranch. Tex used Martin’s old Trading Post as the Ranch headquarters. In 1941, "Buddy" Fogelson, a Texas oilman and rancher bought the ranch. He married Hollywood actress Greer Garson 8 years later. Garson donated the land to The Conservation Fund, who donated it to the federal government.

In 1925, the Kozlowski family sold the Ranch to Tex Austin, who renamed it the Forked Lightning Ranch. Tex used Martin’s old Trading Post as the Ranch headquarters. In 1941, "Buddy" Fogelson, a Texas oilman and rancher bought the ranch. He married Hollywood actress Greer Garson 8 years later. Garson donated the land to The Conservation Fund, who donated it to the federal government.When you get to the Pecos Visitor Center, check to see if the Forked Lightning Ranch is open (it isn’t always open, but it has a nice little museum and is worth the visit.)

When the Union scouting party returned to Kozlowski’s Ranch on the morning of March 26, 1862, and Chivington learned that the Confederates were encamped only 9 miles away, he decided not to wait for Slough and the rest of the Union army to arrive. They reached the summit of the pass, close to where Glorietta Retreat now is, at around 2p.m, and quickly a 30-man Confederate advance force.

Excited by this, the Coloradans rushed into Apache Canyon. The two sides met about a mile and a half west of Pigeon’s Ranch, or six miles northeast of Johnson’s Ranch. The Confederates withdrew about a mile and a half, to a narrower section of the pass that could be better defended. They destroyed the bridge after crossing it. Chivington’s cavalry charged, leaping over the arroyo and sending the Confederates into a panic.

They fled to a bend in the road, where they could hold off the Federals and prevent a complete rout. Chivington decided that they were too far from their supply base to risk another attack and fell back to Pigeon's Ranch. In this first day of battle, the Federals sustained 27 casualties (19 killed, five wounded, and three missing), and the Confederates lost 125 (16 killed, 30 wounded, and 79 captured or missing). This small engagement, no more than a two hour skirmish, marked the first Federal victory in the New Mexico Territory. Up to this point, Confederates had won every battle.

They fled to a bend in the road, where they could hold off the Federals and prevent a complete rout. Chivington decided that they were too far from their supply base to risk another attack and fell back to Pigeon's Ranch. In this first day of battle, the Federals sustained 27 casualties (19 killed, five wounded, and three missing), and the Confederates lost 125 (16 killed, 30 wounded, and 79 captured or missing). This small engagement, no more than a two hour skirmish, marked the first Federal victory in the New Mexico Territory. Up to this point, Confederates had won every battle. Having lost about a third of his command, Pyron retreated back to Johnson’s Ranch. He sent a messenger to Lieutenant Colonel William R. Scurry’s column, which was about 16 miles south, at Galisteo. Chivington also sent a messenger, urging Colonel Slough to hurry southward. That evening, both sides called a truce to tend to their dead and wounded. The truce continued unbroken through the next day.

Stop in the Pecos National Monument Visitor Center. While you’re there, tour the museum. You can pick up a guide for the Ancestral Sites Trail, an easy gravel path that loops through the old pueblo and church. 1.25 mile, with an elevation Change of 80 ft. There is a free ranger guided tour from 10-11 am most days. Check the website for more information.

Also, get the gate code and map to get to the Glorieta Battlefield Trail. The trailhead is 7.5 miles away from the visitor center and behind a locked gate. It is an easy, gravel loop trail that is 2.25 miles around. You can buy a trail guide at the visitor center which will have different information that this guide.

Glorieta Battlefield Trail doesn’t really encompass the entire battle, but some of the third day. I suggest you read the trail guide produced by the Park Service. Here are a few extra notes that might make the route a little more interesting.

Glorieta Battlefield Trail doesn’t really encompass the entire battle, but some of the third day. I suggest you read the trail guide produced by the Park Service. Here are a few extra notes that might make the route a little more interesting.Marker 2: The trail isn’t set up in a way that presents the battle in order. The actual beginning of the battle occurred west of here. This is where the second part of the battle occurred. The Union had pulled back to here, Artillery Hill, to take advantage of the high ground.

Confederate Major John Shropshire was a rich landowner who owned a 750 acre plantation and owned 61 slaves. Born in 1833 in Kentucky, both his parents died of cholera when he was just 3 years old. He was married and had one young son, Charles. He was a very tall man: I’ve seen 6’4” and 6’5”.

Shopshire led a flanking movement around the Union forces, then charged up the hill. He and 30 of his men were killed in the fight. One source I read said that Shropshire was shot between the eyes by a Union private named George W. Pierce. Another says that the top of his head was sheared off by a cannonball.

In June 1987 a man digging a foundation for a new house just across from the Pigeon Ranch discovered a the body. Archaeologists were called in. They discovered that the skeleton was of a 6’4” (or so) man, and the top of the skull was missing. Shropshire was reburied with military honors at his birthplace in Kentucky, alongside his parents in 1990. Archaeologists then discovered a grave with 30 skeletons, which were reburied in the Santa Fe Veterans cemetery.

Marker 3 Is where the battle actually began.

Marker 3 Is where the battle actually began.John Slough had decided to use a pincer movement, sending John Chivington and two infantry battalions up Glorieta Mesa, with orders to circle around the Confederates and attack them from behind. He therefore had less men with him to attack the front of the Confederate forces.

Scurry believed the Union force was retreating to Fort Union. He decided to go after them, leaving his sick and wounded, one cannon, and a small guard with the supply wagons at Johnson's Ranch. He advanced up the canyon with around 1,000 men.

Slough ran into the Confederates here about 11:00 am. Thirty minutes later, the Confederates' numerical superiority managed to push back the Union men to Marker 2’s position.

Marker 4

At the same time as Shropshire was storming Artillery Hill, Scurry sent Henry Raguet to attack the Union right, and around 3:00 pm they succeeded in outflanking the Union right and taking what thereafter became known as Sharpshooters Ridge. Raguet was killed, but the ridge allowed Confederate riflemen to pick off Union artillerymen and infantry below them at Piegeon’s Ranch, making the Union position untenable.

Slough was convinced that his own men were firing on him at Pigeon’s Ranch. This caused him to resign his commission and return to Colorado within days of the battle.

Marker 9 Alfred B. Peticolas kept a multi-book journal of his times with Sibley’s Battalion which included sketches of the places he’d seen. Unfortunately, some of the books were burned at Johnson’s ranch. The Confederates were poorly provisioned, and, coming from Texas, unprepared for how cold New Mexico would be. Many of them wore coats and pants scavenged from Union dead. (The wore the belts upside down, so the US on the belt buckle looked like SN, which they said stood for Southern Nation. This helped distinguish them from Union Soldiers – if you looked close enough. Obviously, Lt. Col Tappan did not.

Marker 9 Alfred B. Peticolas kept a multi-book journal of his times with Sibley’s Battalion which included sketches of the places he’d seen. Unfortunately, some of the books were burned at Johnson’s ranch. The Confederates were poorly provisioned, and, coming from Texas, unprepared for how cold New Mexico would be. Many of them wore coats and pants scavenged from Union dead. (The wore the belts upside down, so the US on the belt buckle looked like SN, which they said stood for Southern Nation. This helped distinguish them from Union Soldiers – if you looked close enough. Obviously, Lt. Col Tappan did not. Lt. Col Samuel F. Tappan was raised in Massachusetts and came from a family of famous abolitionists. A man of high principles, he was the ranking officer and acting colonel when Slough resigned a few days after the victory at Glorieta Pass, but voluntarily relinquished his seniority rights and joined in signing a petition from among the men of the First Colorado to elevate Chivington. He had reason to regret this decision. Tappan headed the military commission that investigated Colonel Chivington for his role in the Sand Creek massacre. He and Gen. Sherman were the two commission members who finalized the Treaty of Bosque Redondo, which allowed the Navajos to return to their homelands, and he worked to assure the rights of the Plains Indians. Marker 10 Slough reluctantly ordered a retreat, and Tappan and his artillery on Artillery Hill covered it. Slough reformed his line a half-mile east of Pigeon's Ranch, where skirmishing continued until dusk. The Union men finally retreated to Kozlowski's Ranch, leaving the Confederates in possession of the battlefield.

Lt. Col Samuel F. Tappan was raised in Massachusetts and came from a family of famous abolitionists. A man of high principles, he was the ranking officer and acting colonel when Slough resigned a few days after the victory at Glorieta Pass, but voluntarily relinquished his seniority rights and joined in signing a petition from among the men of the First Colorado to elevate Chivington. He had reason to regret this decision. Tappan headed the military commission that investigated Colonel Chivington for his role in the Sand Creek massacre. He and Gen. Sherman were the two commission members who finalized the Treaty of Bosque Redondo, which allowed the Navajos to return to their homelands, and he worked to assure the rights of the Plains Indians. Marker 10 Slough reluctantly ordered a retreat, and Tappan and his artillery on Artillery Hill covered it. Slough reformed his line a half-mile east of Pigeon's Ranch, where skirmishing continued until dusk. The Union men finally retreated to Kozlowski's Ranch, leaving the Confederates in possession of the battlefield.Control of the Battlefield is one of the factors in deciding who won. Scurry and the Confederates technically won the battle and, had they not lost their supplies, might have been able to push the Union troops back further in another day of fighting. Furthermore, Col. Tom Green’s men, who’d taken an alternative route south of the mountain pass, might have been able to swing around the mountain’s eastern edge and perform the pincer act on the Union Troops that Slough had intended to perform on the Confederates. The Confederate Army might then have been able to push on to the lightly guarded Fort Union, where they could have gotten enough supplies and ammunition to continue on to Colorado, and then California. With gold, and the deep ports of Los Angeles and San Diego, the war might have ended very differently.

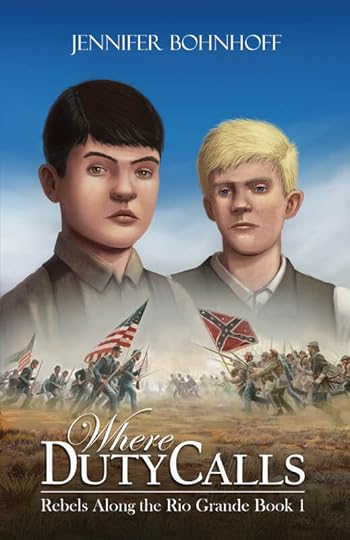

Jennifer Bohnhoff is the author of Rebels Along the Rio Grande, a trilogy of historical novels based on New Mexico during the Civil War. The second book in the series, The Worst Enemy, includes the Battle of Glorieta Pass.

If you are planning to visit Pecos National Monument and want a printable version of this blog, click here.

Published on October 22, 2024 16:42

October 18, 2024

The Long Road Home

Three days ago,

The Famished Country

, book 3 of Rebels Along the Rio Grande, was published by Kinkajou Press, a division of Artemesia Publishing.

Three days ago,

The Famished Country

, book 3 of Rebels Along the Rio Grande, was published by Kinkajou Press, a division of Artemesia Publishing.

I celebrated this new book, and the end of a decade-long project with a Lunch and Learn event at my church, Faith Lutheran Church in Albuquerque.

I celebrated this new book, and the end of a decade-long project with a Lunch and Learn event at my church, Faith Lutheran Church in Albuquerque. Faith has Lunch and Learns monthly. They are a time for people to get together, listen to a speaker, eat a lovely lunch, and spend some time socializing. I've been blessed to be a Lunch and Learn speaker numerous times over the past years.

Yesterday's presentation was entitled The Long Road Home, and it was about the difficult slog of the Confederates once they had their supply wagons burned in Glorieta Pass.

The Confederate Army was pushing back the Union forces during the Battle of Glorieta. Given another day of battle, they just might have won and been able to push their way forward, through the canyon and on to Fort Union, the best stocked supply depot in the Southwest. If they'd been able to take the fort and all its ammunition, Sibley's Army of New Mexico just might have been able to press on and take the gold fields of Colorado and the deepwater ports of Southern California. All the big dreams of the big-talking H.H.Sibley would have come to fruition, giving the Confederacy a huge boost in resources and in accomplishments. However, as the third day of battle ended, Scurry and Pyron realized that their supply wagons, left undefended back at Johnson's Ranch, had been destroyed. With no supplies, the rebels had no choice but to retreat back to Texas. On their way, the ragged remains of the army passed through Albuquerque, where the men camped, ironically, in a place named La Glorieta. They engaged Canby's forces in a cannonade there and in Peralta, and then, out of bullets and cannon balls, walked around Fort Craig to avoid another battle that they could not possibly win.

The Confederate Army was pushing back the Union forces during the Battle of Glorieta. Given another day of battle, they just might have won and been able to push their way forward, through the canyon and on to Fort Union, the best stocked supply depot in the Southwest. If they'd been able to take the fort and all its ammunition, Sibley's Army of New Mexico just might have been able to press on and take the gold fields of Colorado and the deepwater ports of Southern California. All the big dreams of the big-talking H.H.Sibley would have come to fruition, giving the Confederacy a huge boost in resources and in accomplishments. However, as the third day of battle ended, Scurry and Pyron realized that their supply wagons, left undefended back at Johnson's Ranch, had been destroyed. With no supplies, the rebels had no choice but to retreat back to Texas. On their way, the ragged remains of the army passed through Albuquerque, where the men camped, ironically, in a place named La Glorieta. They engaged Canby's forces in a cannonade there and in Peralta, and then, out of bullets and cannon balls, walked around Fort Craig to avoid another battle that they could not possibly win.

Sibley had left San Antonio, Texas in October 1861 with 3,200 men. When he returned to Confederate territory in May, 1862, he had only 1,500 men with him. The rest had been lost to battle, disease, starvation, dehydration, and desertion. Once within Confederate Territory, the army disbanded. It took months for the men to trickle back to their homes. Some of them never made it. It's been a long road for me as an author. I've been working on Rebels Along the Rio Grande for more than a decade now, and I am pleased that the series is complete. I have followed Jemmy back to his reunion with his father, and he, Raul and Cian are all on to new adventures. The Civil War is over for my three protagonists.

Sibley had left San Antonio, Texas in October 1861 with 3,200 men. When he returned to Confederate territory in May, 1862, he had only 1,500 men with him. The rest had been lost to battle, disease, starvation, dehydration, and desertion. Once within Confederate Territory, the army disbanded. It took months for the men to trickle back to their homes. Some of them never made it. It's been a long road for me as an author. I've been working on Rebels Along the Rio Grande for more than a decade now, and I am pleased that the series is complete. I have followed Jemmy back to his reunion with his father, and he, Raul and Cian are all on to new adventures. The Civil War is over for my three protagonists.

But I am not all the way home yet, and my mission isn't truly complete. Although I have all three books in print, I still need to complete teacher's guides for books 2 and 3, and I hope to get all three books produced as audio books, so that middle graders who have difficulty reading will also be able to learn about the Civil War in New Mexico. I may still have a long ways to go before I can hang my hat on the peg and call it quits.

But I am not all the way home yet, and my mission isn't truly complete. Although I have all three books in print, I still need to complete teacher's guides for books 2 and 3, and I hope to get all three books produced as audio books, so that middle graders who have difficulty reading will also be able to learn about the Civil War in New Mexico. I may still have a long ways to go before I can hang my hat on the peg and call it quits.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a former educator who now devotes her time to writing. Most of her books are historical fiction, and suitable for middle grade through adult readers. You can learn more about her books here, on her website.

Jennifer Bohnhoff is a former educator who now devotes her time to writing. Most of her books are historical fiction, and suitable for middle grade through adult readers. You can learn more about her books here, on her website.

Published on October 18, 2024 08:35

October 11, 2024

The Colorado Contribution to New Mexico During the Civil War

Colorado came to be a territory of the United States in a piecemeal fashion. Its present-day eastern and central areas were part of the Louisiana Purchase, made 1803, while the western portion of the state was acquired during the Mexican War (1846-1848) from Mexico, who had gained control over the area in 1833 when it had won its independence from Spain. Even after all the land was firmly under U.S. control, the area was divided. Parts of present-day Colorado were included in New Mexico and Utah Territories, both organized in 1850. Others were of Kansas and Nebraska Territories, organized in 1854.

Colorado came to be a territory of the United States in a piecemeal fashion. Its present-day eastern and central areas were part of the Louisiana Purchase, made 1803, while the western portion of the state was acquired during the Mexican War (1846-1848) from Mexico, who had gained control over the area in 1833 when it had won its independence from Spain. Even after all the land was firmly under U.S. control, the area was divided. Parts of present-day Colorado were included in New Mexico and Utah Territories, both organized in 1850. Others were of Kansas and Nebraska Territories, organized in 1854.Until the late 1850s, when gold was discovered in Russellville Gulch in present-day Douglas County and along Cherry Creek near where it joins with the Platte River, Colorado only had about 7,500 settlers. By 1859, an estimated 100,000 men had entered the gold fields. Because many of these men came from Georgia and other southern states, the area had a distinctive lean towards southern sympathies.

Five days before Abraham Lincoln became President on 4 March 1861, his predecessor, James Buchanan signed the law that made Colorado a Territory. Two weeks after his inauguration Lincoln, who wanted a pro-Union governor for Colorado Territory, proposed William Gilpin to the Senate, who appointed him, but then recessed before passing any appropriations for the new Territory. Gilpin was left with just a $1,500 contingency fund with which to run the new territory. He arrived in Denver before June and toured the mining camps, discovering that the boom had passed and a new census showed only about 25,000 people including 4,000 white females and 89 Negroes in the territory, most of them concentrated in the Clear Creek, Boulder, and South Park mining districts and in the small but growing town of Denver.

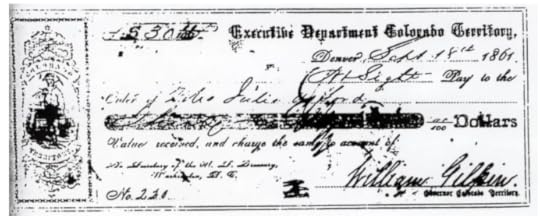

On April 12, Confederate forces fired on Ft. Sumter. The U.S. government’s focus shifted to calling up troop in the east, and the needs of Colorado was forgotten. Concerned that the Confederacy would try to conquer the territory for its vast mineral deposits as well as its strategic location, Gilpin began organizing the Territorial military that summer. Morton C. Fisher, his newly appointed Purchasing Agent, was immediately sent out to buy and collect all the arms he could, both supply the new troops and to keep those arms out of the hands of Southern sympathizers. Not having the money to organize and equip the men, Gilpin issued $375,000 worth of drafts, known as Gilpin Scrip, directly upon the United States Secretary of the Treasury. These drafts were used as money in the Territory and were passed along to Washington, who honored payment for some of the script at a value considerably below face value. A year later, this illegal action would cost him his position as Territorial Governor, and he was forced to resign the next year.

Gilpin’s intent was to use the money to create the First Regiment of volunteers consisting of ten companies. He appointed John P. Slough to be its Colonel and Samuel F. Tappan, to be Lt. Colonel. Gilpin had planned for John M. Chivington, an elder of the Methodist Episcopal Church, to be the Chaplain, but when Chivington turned down the appointment and requested a fighting commission, he was made Major. The troops were ordered to Camp Weld, a new installation being built about two miles south of Denver. Gilpin’s Script paid for the building of Camp Weld as well as uniforms, arms, supplies and equipment for the troops.

Gilpin’s intent was to use the money to create the First Regiment of volunteers consisting of ten companies. He appointed John P. Slough to be its Colonel and Samuel F. Tappan, to be Lt. Colonel. Gilpin had planned for John M. Chivington, an elder of the Methodist Episcopal Church, to be the Chaplain, but when Chivington turned down the appointment and requested a fighting commission, he was made Major. The troops were ordered to Camp Weld, a new installation being built about two miles south of Denver. Gilpin’s Script paid for the building of Camp Weld as well as uniforms, arms, supplies and equipment for the troops. One of the first men to join Gilpin’s new militia was Samuel H. Cook, who convinced 80 men from the gold fields of the South Clear Creek mining district to join with him on a ride to Kansas, where they would join the Union Army and serve under General James Lane. As they were passing through Denver in the middle of August, Cook met Governor Gilpin, who persuaded him to remain in Colorado and join what was becoming the First Regiment of the Colorado Volunteers. Cook’s men became a mounted troop, designated as Company F.

One of the first men to join Gilpin’s new militia was Samuel H. Cook, who convinced 80 men from the gold fields of the South Clear Creek mining district to join with him on a ride to Kansas, where they would join the Union Army and serve under General James Lane. As they were passing through Denver in the middle of August, Cook met Governor Gilpin, who persuaded him to remain in Colorado and join what was becoming the First Regiment of the Colorado Volunteers. Cook’s men became a mounted troop, designated as Company F. In December of 1861, news came from New Mexico that Confederate troops under H.H. Sibley had invaded over the Texas border, two companies of Colorado Volunteers set out for New Mexico. These companies were Captain Theodore H. Dodd’s Independent Company, Colorado Volunteers and Captain James H. Ford’s Independent Company, Colorado Volunteers. Dodd’s Company was sent to Fort Craig, where they resisted a charge of lancers in the battle of Valverde on February 21, 1862. Ford’s Company was sent to Taos and then Santa Fe before being ordered back to Ft. Union.

On February 14, 1862 orders arrived that asked that all available forces that Colorado could spare be sent south to aid Colonel Canby, the commander of the Department of War in New Mexico. On February 22, the main body of the First Colorado Regiment, including Captain Cook’s Co. F, set out amid intense snow storms. They arrived at Fort Union on March 10th and were joined the next day by Ford’s Company. Slough would march most of these men south, where they participated in the Battle of Glorieta before joining forces with Canby to shepherd the retreating Confederates back to their own territory, ensuring that both New Mexico and Colorado Territories would remain in Union hands.

Jennifer Bohnhoff's trilogy, Rebels Along the Rio Grande, is written for middle grade readers who are interested in the Civil War in New Mexico.

Jennifer Bohnhoff's trilogy, Rebels Along the Rio Grande, is written for middle grade readers who are interested in the Civil War in New Mexico.

Published on October 11, 2024 10:31

October 2, 2024

Apple butter Pie

I got a big load of apples from my sister lately. I put up jars of both smooth and chunky applesauce, stowed away bags of peeled and sliced apples in the freezer, and made a batch of apple butter.

If you've never had apple butter, you're missing out. Dark, sweet, and redolent with fall spices, it warms your heart and satisfies your tummy. I went online, looking for things to do with apple butter beyond spreading it on toast, and I found a recipe for apple butter pie. The recipe was gluten free, and had many steps that I didn't want to go through, so I took the idea, modified it, and came up with something of my own.

Apple butter pie is a custard pie, similar in texture to a pumpkin pie. I think it would be a perfect addition to a fall feast, and a great substitute for those who aren't all that keen on pumpkin. It's also easy, especially if you have a food processor. Give it a try and tell me what you think! Crust:

Crust:

1 1/3 cups all purpose flour

1/2 tsp salt

1/2 cup shortening

2 1/2-3 TBS ice water

1/2 TBS vinegar

Filling:

1 cup apple butter

3 large eggs

1 cup dark brown sugar

1 TBS all purpose flour

1/2 tsp cinnamon

1/2 tsp salt

14 oz. evaporated milk

1 tsp vanilla.

Cinnamon Sugar:

1 1/2 TBS granulated sugar

3/4 tsp ground cinnamon

Food Processor Method:

Preheat oven to 400°

Place flour and salt into food processor bowl. Dollop shortening over flour. Pulse 1 or 2 times. Slowly add vinegar through liquid dispenser while pulsing. Add water slowly while pulsing. When dough forms into a solid ball, take it out of the processor bowl, wrap in plastic wrap, and refrigerate for about 10 minutes. Place on a floured sheet of wax paper. Use a floured rolling pin to roll the dough into a circle 3" bigger than your pie plate. Pick up the waxed paper and flip it over atop the pie plate. Ease into the plate. Crimp the edge, or flatten it and brush it with cold water. Use a small cookie cutter on scraps to make shapes to go around the edge or to float on the filing. Sprinkle the shapes with some of the cinnamon sugar.

Add all filling ingredients to food processor bowl and process until smooth. Pour into pie crust. If using, add cutouts to pie. Sprinkle filling with remaining cinnamon sugar.

Bake at 400°for 10 minutes. Reduce heat to 350° and continue baking for 30-40 minutes, until crust is brown and filling doesn't jiggle when the pie is shaken.

Let pie cool for at least an hour before serving. A big dollop of whipped cream really enhances this pie. Mix by Hand Method:

Preheat oven to 400°

Mix flour and salt in medium bowl. Cut shortening into flour using a pastry cutter or fork until particles of shorting are the size of small peas. Sprinkle with vinegar and mix with fork. Sprinkle with water 1/2 TBS at a time until dough forms into a solid ball. Take it out of the bowl, wrap in plastic wrap, and refrigerate for about 10 minutes. Place on a floured sheet of wax paper. Use a floured rolling pin to roll the dough into a circle 3" bigger than your pie plate. Pick up the waxed paper and flip it over atop the pie plate. Ease into the plate. Crimp the edge, or flatten it and brush it with cold water. Use a small cookie cutter on scraps to make shapes to go around the edge or to float on the filing. Sprinkle the shapes with some of the cinnamon sugar.

Beat all filling ingredients together in a bowl until smooth. Pour into pie crust. If using, add cutouts to pie. Sprinkle filling with remaining cinnamon sugar.

Bake at 400°for 10 minutes. Reduce heat to 350° and continue baking for 30-40 minutes, until crust is brown and filling doesn't jiggle when the pie is shaken.

Let pie cool for at least an hour before serving. A big dollop of whipped cream really enhances this pie. Jennifer Bohnhoff is the author of contemporary and historical fiction for middle grade through adult readers. She also likes to putter in the kitchen. For more information on her and her books, visit her website. For more recipes, sign up for her newsletter.

If you've never had apple butter, you're missing out. Dark, sweet, and redolent with fall spices, it warms your heart and satisfies your tummy. I went online, looking for things to do with apple butter beyond spreading it on toast, and I found a recipe for apple butter pie. The recipe was gluten free, and had many steps that I didn't want to go through, so I took the idea, modified it, and came up with something of my own.

Apple butter pie is a custard pie, similar in texture to a pumpkin pie. I think it would be a perfect addition to a fall feast, and a great substitute for those who aren't all that keen on pumpkin. It's also easy, especially if you have a food processor. Give it a try and tell me what you think!

Crust:

Crust: 1 1/3 cups all purpose flour

1/2 tsp salt

1/2 cup shortening

2 1/2-3 TBS ice water

1/2 TBS vinegar

Filling:

1 cup apple butter

3 large eggs

1 cup dark brown sugar

1 TBS all purpose flour

1/2 tsp cinnamon

1/2 tsp salt

14 oz. evaporated milk

1 tsp vanilla.

Cinnamon Sugar:

1 1/2 TBS granulated sugar

3/4 tsp ground cinnamon

Food Processor Method:

Preheat oven to 400°

Place flour and salt into food processor bowl. Dollop shortening over flour. Pulse 1 or 2 times. Slowly add vinegar through liquid dispenser while pulsing. Add water slowly while pulsing. When dough forms into a solid ball, take it out of the processor bowl, wrap in plastic wrap, and refrigerate for about 10 minutes. Place on a floured sheet of wax paper. Use a floured rolling pin to roll the dough into a circle 3" bigger than your pie plate. Pick up the waxed paper and flip it over atop the pie plate. Ease into the plate. Crimp the edge, or flatten it and brush it with cold water. Use a small cookie cutter on scraps to make shapes to go around the edge or to float on the filing. Sprinkle the shapes with some of the cinnamon sugar.

Add all filling ingredients to food processor bowl and process until smooth. Pour into pie crust. If using, add cutouts to pie. Sprinkle filling with remaining cinnamon sugar.

Bake at 400°for 10 minutes. Reduce heat to 350° and continue baking for 30-40 minutes, until crust is brown and filling doesn't jiggle when the pie is shaken.

Let pie cool for at least an hour before serving. A big dollop of whipped cream really enhances this pie. Mix by Hand Method:

Preheat oven to 400°

Mix flour and salt in medium bowl. Cut shortening into flour using a pastry cutter or fork until particles of shorting are the size of small peas. Sprinkle with vinegar and mix with fork. Sprinkle with water 1/2 TBS at a time until dough forms into a solid ball. Take it out of the bowl, wrap in plastic wrap, and refrigerate for about 10 minutes. Place on a floured sheet of wax paper. Use a floured rolling pin to roll the dough into a circle 3" bigger than your pie plate. Pick up the waxed paper and flip it over atop the pie plate. Ease into the plate. Crimp the edge, or flatten it and brush it with cold water. Use a small cookie cutter on scraps to make shapes to go around the edge or to float on the filing. Sprinkle the shapes with some of the cinnamon sugar.

Beat all filling ingredients together in a bowl until smooth. Pour into pie crust. If using, add cutouts to pie. Sprinkle filling with remaining cinnamon sugar.

Bake at 400°for 10 minutes. Reduce heat to 350° and continue baking for 30-40 minutes, until crust is brown and filling doesn't jiggle when the pie is shaken.

Let pie cool for at least an hour before serving. A big dollop of whipped cream really enhances this pie. Jennifer Bohnhoff is the author of contemporary and historical fiction for middle grade through adult readers. She also likes to putter in the kitchen. For more information on her and her books, visit her website. For more recipes, sign up for her newsletter.

Published on October 02, 2024 23:00

September 28, 2024

Civil War Books for Middle Grade Readers

The American Civil War may be 150 years ago, but it still fascinates adults and children alike. When people think about the Civil War, they think of Antietam, Gettysburg, and other great battles in the east. They think of the Emancipation Proclamation and the freeing of the Black slaves in the south. With the possible exception of Bloody Kansas, few people are aware that there were Civil War battles east of the Mississippi, but there were.

The American Civil War may be 150 years ago, but it still fascinates adults and children alike. When people think about the Civil War, they think of Antietam, Gettysburg, and other great battles in the east. They think of the Emancipation Proclamation and the freeing of the Black slaves in the south. With the possible exception of Bloody Kansas, few people are aware that there were Civil War battles east of the Mississippi, but there were.I learned how few people were aware of the Civil War in the west when I taught New Mexico history to 7th graders. My parents were surprised when their children started talking about Civil War battles. Some even told me that I was wrong, and that there were no battles here. There were, and had the Confederacy won them, the war might have turned out very differently. I wrote Rebels Along the Rio Grande because there was such a paucity of material on this subject.