David Williams's Blog, page 78

October 6, 2014

Loss, Death, and Paths not Taken

It was a rough day in Poolesville this last Wednesday, as the news of a young man's suicide hit the town hard. It was a hard weekend, as one of the faith communities just a short walk from my own spoke out words of sorrow and blessing over that life.

It was a rough day in Poolesville this last Wednesday, as the news of a young man's suicide hit the town hard. It was a hard weekend, as one of the faith communities just a short walk from my own spoke out words of sorrow and blessing over that life.I didn't know him personally. But he was a child of the town. In a community where people still know one another, it was clear so many of the folks at my church had been touched by his life. I feel their hurt and the resonance of his loss through so many people around me, like placing your hand on a bell that's been struck, and feeling it hum against your skin.

It's a difficult thing to process. Here, you had a life that is unquestionably full of promise, and then that promise seems to have vanished like smoke in a strong breeze. All those moments that you hoped to share, gone.

It feels both so unnecessary and so understandable, particularly if you've been through the fires of adolescence yourself. Everything feels so immediate, so intense, so radically defining at that momen...and if you're struggling with something, that can feel like it's your whole world.

I remember that feeling, in the same way I remember being a kid and I remember being 25. If we are to remain ourselves, we can't forget that feeling. Life was intense, immediate, and the encounter with the pressing realities of adulthood had that radiance that comes from our encounter with the new. There were moments of failure, and they were abject and abysmal. There were moments of joy and passion, and they were everything.

And when you're struggling with something, particularly the dark veil of depression, it can feel like that moment of struggle is forever. There's no escape from it. The only way out, you think in that moment, is something irrevocable.

That's wrong, because it's not true. It is not a reflection of reality. The reality is that there are people who love you, who care for you, and who will be impacted by your loss. The reality is that if you wait a day, a week, a month--life will seem different.

But it's also wrong because it doesn't reflect the reality of creation. In the wild universe in which we find ourselves, there's always a different path. There's always a brighter and more life-giving choice. The God who makes all things possible does not just set one path before any of us. There are paths that lead to sorrow, isolation and darkness, sure. But we do not have to walk them. We are free to turn away, and choose something different. That isn't easy, particularly with the blinders of depression constraining our vision. But it's real. That potential is there, resting in the knowledge of God.

And that truth, so important to hold in our times of despair, is also important to hold when we have lost someone too young. What we mourn isn't just the life that has passed, but the life we will not know. We mourn the moments we will not share with them, that future which is now precluded.

There, from my own faith, there is a solace. Because although that future is precluded from our knowledge here in this life, it is not precluded from the knowledge of God. The Creator knows not just what have done and what we will do, but what we might have done and what we might yet do. Though hidden from us, we can trust that those unfulfilled moments are not unknown to God. God knows what that life would have been, with a knowledge so deep that it is not simply knowing, but being.

In the heart of God, everything that our loved one could have been is held as surely as the reality we inhabit is held, because there is nothing that God does not know in its fullness.

When we look to a life cut short, to possibilities that seem suddenly gone, there is comfort in knowing that just as the past is not forgotten, neither is that future.

Published on October 06, 2014 04:41

October 3, 2014

Ebola, Ignorance, and "Knowledge"

My stalwart adult ed class and I are cranking our way through the Book of Revelation these last few weeks, and it is going as one might expect.

My stalwart adult ed class and I are cranking our way through the Book of Revelation these last few weeks, and it is going as one might expect.John of Patmos has a wild, fever-dream way of articulating faith, and negotiating the complex and intentionally obscure mess of symbols and images that make up that peculiar book isn't always easy. I'll freely admit it's not my favorite book of the Bible--not my least favorite, but certainly among the bottom five. It's also not a book that any honest teacher will attempt to definitively interpret, so I don't.

I'll present the scholarly options, sure, and some of the most viable interpretive hypotheses. I can also say that some interpretations--particularly those that respect the context and community that initially received the book--are more likely than others.

What I've been especially intentional about NOT doing is interpolating any of John's wild mix of apocalyptic imagery into current events, or trying to say I know more than can be possibly known about the intent of that willfully obscure book. That's always been the temptation for readers of Revelation, and it has always, always been the wrong way to approach that difficult book. Can you? Of course you can, in the way that we see images in the clouds or the face of our first lover in a rorschach blot. But it's projection, not prophesy. And we project when we don't want to really know or be changed.

Which brings us, in a roundabout way, to the terrible spread of the Ebola virus in West Africa, and its recent nudging out into our nation.

The smorgasbord of plagues and destructions layered on top of destructions that are served up in that Book get plugged into just about any catastrophe. As, indeed has Ebola. Of course, it's not clear which of the inchoate swirl of visions it might be. Is it the last of the four horsemen, who brings pestilence in Rev. 6:8? Or maybe it's the work of the two witnesses, striking the earth with any kind of plague they want. (Rev. 11:6) Or perhaps it's the first cup poured out by the first angel. (Rev. 16:2)

It's that latter one that seems to be making the rounds in West Africa these days, spread by those who want their own spin on the nature of things to actually be the nature of things. And so we get a group of conservative Christian leaders in Liberia announcing, as things fall apart, that it's "homosexualism" that's responsible for Ebola. Not directly of course, but the Creator of the Universe is so angry at gays and lesbians that a disease has been sent to kill innocent children and their mothers, as they hemorrhage to death in fetid conditions. It's the first cup! The end times are upon us!

That one can say that "God is Love" on the one hand and then "God Willfully Kills Children With a Hemorrhagic Fever to Punish Us for Tolerating Gays" on the other isn't just hypocritical. It's remarkably dissonant. That kind of dissonance is the heart of madness, and what turns faith from the source of our hope to the source of our horror.

There's something more at play here, though. The drive to plug terrible events into an existing worldview is basically, terribly human. Our yearning to find a "why" behind this outbreak...to know the secret behind it...is both a fundamental human urge and a dangerous one.

The honest human yearning for deepening knowledge--as found in the epidemiology and the hard science behind serious efforts to find a cure for this terrible disease--is our hope in combating Ebola. But the human tendency to want to imagine we already know, that fusing of our thirst for knowing with our hunger for power? That's dangerous, both spiritually and materially.

It's not just my ultra-conservative African brethren who do this. Ignorance knows no cultural bounds. The whispering, paranoiac corners of the American internet are already buzzing and humming about how this disease is a genetically engineered plague, and about how government efforts to contain it are just part of a great conspiracy to keep us from the truth and to restrain our freedom.

Instead, we should place our hope in buying the "essential oils" being marketed by the hucksters spreading this "truth," and whispering subversion of those systems upon which our hope for restraining this plague rest.

Ignorance has always been the enemy of transformation, and the stumbling block we set before ourselves.

As terrible as ignorance is, willful ignorance is worse.

Published on October 03, 2014 05:34

September 29, 2014

Look at How We Kill You

Yesterday morning, as I was doing the final edit on my sermon, I flitted briefly to web-based news sources to check in on the world. It's always wise, before the community gathers, to be sure you're not blithely arriving, unaware of some momentous and terrible event.

Yesterday morning, as I was doing the final edit on my sermon, I flitted briefly to web-based news sources to check in on the world. It's always wise, before the community gathers, to be sure you're not blithely arriving, unaware of some momentous and terrible event.There they were, a sequence of short videos. A montage, if you will, courtesy of both the armed forces of my nation and those of one of our allies. They were familiar images, in both content and format, ones we've seen from most of our recent wars.

The format was monochromatic, the images filtered through a FLIR or similar thermal imaging scope. There, a nondescript building in a compound, marked with a targeting computer's symbol. Three, two, and at one, there's an explosion leaping from the roof, as the armor-piercing portion of the munition punches through.

Then, a millisecond later, a much larger explosion as the primary payload detonates, obliterating the building, casting a fiery cloud of debris and dust that consumes most of the compound.

The video stops, and loops. With it, there are others, which I watch. Here, an animated GIF length image of a tank, which explodes. There, a vehicle in motion--a truck, or a HUMVEE--and then it flares out as the explosion maxes out the thermal camera tracking it.

It is seven-thirty on a Sunday morning, and in preparation for worship I have just watched dozens of human beings killed.

What struck me, looking at the videos, was that they were a peculiar mirror to the net-circulated videos that I had only been able to watch in part, those from a few weeks ago. Those were personal, brutal, savage and monstrous, of unarmed men butchered like pigs or cattle.

"Look at how we hate you. Look at the way that we kill you," those videos said, and they were horrors.

And yet, here we are, sharing our own images of killing. They are different, in the way that industrial killing is different.

"Now, look at how we kill you," our videos say. They are distant and dispassionate, precise and clinical.

At the dawn of the internet age, there was this great hope: now, human beings will finally be able to share information freely with one another. It will change who we are, the dreamers proclaimed. Through that sharing, an age of peace and mutual understanding will dawn.

It hasn't quite worked out that way.

Published on September 29, 2014 06:09

September 27, 2014

The Sweet New Year

Last year, at around this time, I was celebrating the Jewish High Holy Days with my family.

Last year, at around this time, I was celebrating the Jewish High Holy Days with my family.It was a remarkable Yom Kippur, as I sat up there on the bimah with my wife on the holiest day in Judaism, and had the honor of removing the Torah from the ark. It felt more than a little bit magical. I'm sure others of my Presbyterian pastor colleagues must have had that privilege at some point, but I think it's safe to say this ain't a typical occurrence. This generally doesn't happen when you're not just a random one a' tha goyim, but a professional gentile.

This week, as the new year began, I was up on the bimah again with my wife for Rosh Hashanah. Again, I took the Torah from the ark and gave it to her, and again watched her circle the synagogue, the congregants kissing their prayerbooks and touching them to the covered scroll.

It was the Head of the Year, the point where those days of repentance and change begin. It's the point where we both celebrate the promise of a year to come, but also look to the year that has passed, thinking of the ways we might change for the better in the coming year. It's a time for intentional reconciliation, for seeking ways to heal those things that were broken.

What I reflected on, in this new year, was the challenging year it was for relationships between Judaism and my denomination. The choice of our General Assembly to selectively divest from three American companies providing security/military resources to Israel was a choice to push a particularly large red button. Though I know people of good conscience who disagree, it wasn't a hateful choice, or an anti-semitic choice, or even a choice that was meaningfully anti-Israel. It couldn't be, any more than choosing not to invest in Lockheed Martin, General Dynamics, or the Corrections Corporation of America is bad and anti-American. If you have a socially responsible investment policy based on your faith principles that prevents you from profiting from war or incarceration, that's just where you end up.

But rationally explicable though it was, it was a button nonetheless, the sort of thing that tends to cause a binary reaction.

That was early summer, and the heat and light of debate and missives and editorials burned bright and fierce. "This is the thing we are fighting about right now!" But now months have passed, and the chatter and hum has disappeared, its afterglow as difficult to detect in the collective subconscious as the cosmic background radiation from the dawn of our sliver of the multiverse.

Though it had been a hard year, now it is a new one. And at the dawn of that year, there I was, a Presbyterian pastor, up again on the bimah. Still in relationship, just as I'd been the year before. My wife and I sat close, and shared her prayerbook. We read and chanted the prayers together, her Hebrew solid and confident, mine mostly there most of the time. We sang the shema, and all the sacred songs which I know by heart after 23 years of High Holy Days, 23 years and change since we stood under a canopy on that very bimah. I stood by the opened ark, and listened to the shofar. I heard the rabbi's voice mingle with the sound of my older son's baritone ringing from the choir. I stood around at the reading of the Torah, and watched as my younger son held the microphone for the rabbi's wife as she chanted.

It was as sweet as honey on my soul.

I'm hoping, in this year 5775, that things are a little sweeter for all of us.

Published on September 27, 2014 06:06

September 24, 2014

The Limits of Co-Creation

I read through the article with interest, as I do with all articles about religious events.

I read through the article with interest, as I do with all articles about religious events.It was a description of a journalist's attendance at a huge Oprah conference, part of a traveling inspirathon called the "The Life You Want Weekend." It was a huge shiny neo-spiritual gathering, as tens of thousands of eager devotees poured into a stadium to hear Ms. O and her retinue dispense vital life-learning lessons.

The cost: between $200 and $500 a pop, in exchange for which the attendees got workbooks and weird glowing bracelets, not to mention exposure to levels of ambient atmospheric estrogen so high they temporarily eliminate the need for oral contraception.

I harbor no animus towards Oprah. She's intelligent, driven, and capable, and the amazing success she's experienced over the years seems well-earned. Her profoundly American message of positivity and self-empowerment may be big, self-promoting, and high-gloss-shiny, but it isn't evil, and she comes across as a sharper progressive fusion of Zig Ziglar and Joel Osteen. She's willing to engage with spirituality, in a way that is both affirming and open.

Sure, it's tempting to snark and roll eyes, but the people she engages sometimes come frighteningly close to describing my own view of existence. Yeah, Deepak is up there doing his Chopra thing, but the connection goes deepah.

I mean, sweet Mary and Joseph, Rob Bell? Rob Bell's tagging along for the Oprah dog-and-pony show? I like Rob Bell! His approach to faith is so close to mine as to being almost indistinguishable. I've recommended Rob Bell's books to people! I still do.

Does that mean...am I...somehow...in Oprah-orbit? How did that happen?

As I read through the article describing the high-gloss perfection of the event, something stuck with me. It was a phrase, one of the inspirational statements uttered during the event.

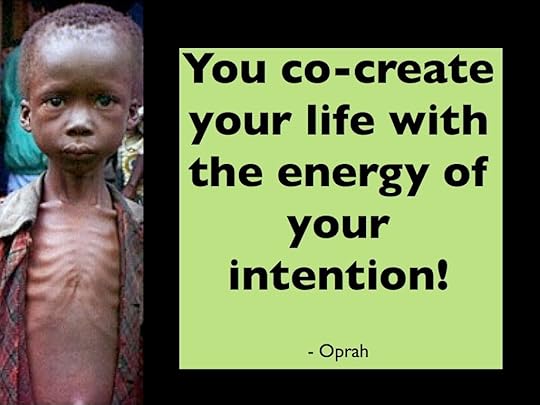

"You co-create your life with the energy of your intention."

The language of co-creation is stock-in-trade for many progressive spiritual folk. It speaks to our freedom, our ability to influence the direction of our lives, our fundamental empowerment as sentient beings to shape the world around us.

It meshes with my own view of the nature of both being and the Creator, and I'll confess to having used variants of that concept myself on occasion. It's a good truth, a truth that reflects humanity at our best.

But I also know that while it is a truth, it is a contingent truth. Meaning, it can be true, but it is not necessarily true. If you're able to drop a couple of hundred bucks on an Oprahfest, then, yes, it probably reflects your encounter with reality. It is also true for me.

If you are like a significant majority of humankind, though, it does not describe your reality. The capacity to co-create is tied in to the blessings of liberty, and most of us are not free to act as we would choose. If you are driven by hunger, struggling to simply survive, all of the "energy of your intention" is turned towards that end.

The Life You Want is to live, and not die of hunger or thirst this weekend.

If you are living under an oppressive regime, be it Putin's neoTzarist Russia, the bizarre Communo-capitalist fusion of the Chinese Central Committee, or the raw brutality of ISIS, you are not free to co-create. You obey, and you keep your head down, or the energy of your intention will be met with the far greater energy of those whose intention is driven by their hunger for power over you.

And if, like so many Americans, you are scrambling to pay the bills, working three crap jobs with no security, with a barely working twelve year old car and a fridge that just died, your ability to be creative with your life is next to zero.

Hope is important, yes. Being positive and seeing the potential in your life is important. But for so many, the probability of living a life in which real freedom exists is so low as to be meaningless.

It is easy, in the shiny and carefully crafted narrative of co-creative self-empowerment, to forget this.

Published on September 24, 2014 05:23

September 23, 2014

Our Love, Our Faith, and Our Violence

Of all of the cinematic experiences I've had this year, one stands out, and it wasn't even a movie.

It was The Last of Us, a game I played through over the last couple of weeks, although calling it a "game" seems vaguely unfair and inaccurate. It was a participatory narrative, a story in which you engage and move, but which carries through you through the lives of human beings living after the collapse of our culture.

In that, it played off of some familiar themes in our storytelling. There's been a fungal pandemic, one that renders its victims both insane and violent before devouring them completely. It's a variant on the zombie apocalypse trope, and yeah, that's been done a whole bunch.

Before I continue just a warning--if you ever plan on playing this game, there will be spoilers coming up. And they will spoil what is a simply brilliant experience.

The gameplay was good, and the graphics were evocative, but those weren't the best features of this game. What was most striking, given that this is technically a "game," was the degree to which the animation and the voice-acting created a really powerful sense of the reality of the characters involved. Our protagonists are Joel and Ellie, and their relationship is complex and finely drawn.

Joel, a grizzled man in his early fifties, lost everything that was precious to him when the pandemic hit. Most significantly, he lost his daughter Sarah, a young teen who dies in the genuinely harrowing opening sequence. All that matters to him now is survival--although he's cynical about even that--and any moral core that he once had has long since atrophied.

Ellie is a fourteen year old girl, who he's tasked with escorting across country for reasons the narrative will soon make clear. She's never known anything but the fallen world, and is both a child and a young woman, both an innocent and hardened.

Their relationship develops slowly and organically over the 14-17 hours of gameplay, and as Joel bonds with the girl who echoes his daughter, she increasingly becomes the entire reason for his existence. He's deeply reluctant to make himself vulnerable in that way, and self-aware enough to realize she's becoming a daughter to him, but the connection continues and deepens as their bond grows. Protecting her, caring for her, watching over her--that becomes the purpose of his life. By the end of the game, his love for her is palpable.

It also drives him to do terrible things. The Last of Us is a violent game, intensely, realistically so. It's not at all like Call of Duty or other shooter games, where violence is empty play. It's rough, and unpleasant. The game never lets you forget the mortal frailty of the characters you're playing, or the shared humanity of the people you find Joel and Ellie kill.

What you realize--in some very difficult but well-written sequences--is that eventually nothing matters to Joel but Ellie. Nothing. He will torture, he will kill, he will let all of humanity suffer under a plague forever, anything, so long as she is safe. He will even manipulate her trust and lie to her, so long as he is convinced that his deception will keep her from harm.

Her safety becomes his purpose, his moral core, and the goal of his life. She is the thing he loves above all else. And while that is what makes him very connectably human, it is also what enables him to be a monster.

For human beings, that's always been true. When we allow our lives to be defined by a singular goal--our existential ground, our life-purpose--that gives us our integrity as a person. But that thing, if it is wrought too shallowly, can also be what allows us to inflict terrible harm.

We can be defined by ourselves, our pride, our desire, our ambition. We can be defined by an ideology or nation. We can be defined by our love for another person, our partner, our friend, our child. Those things become the objects of both our love and our faith.

They also become what allows us to not really see those who are outside of that relationship as human, not see their value, and can become the foundation of our violence against another.

Our ability to love, if turned to the wrong end, is also the heart of our brokenness.

Published on September 23, 2014 06:34

September 22, 2014

When We Need New Software

For nearly the last year, I've suffered through owning what had been, without question, the worst appliance I'd ever encountered.

For nearly the last year, I've suffered through owning what had been, without question, the worst appliance I'd ever encountered.It was a clotheswasher, what should be the simplest of things. Put dirty clothes in. It chugs away. Take clean clothes out. Nice and easy.

But the washer I bought on the recommendation of my research and the blessing of Consumer Reports couldn't quite manage it. It's not that it was poorly built, or that there was something wrong with the basic design. It was just so complicated--designed to be hyper-efficient, water-saving, and high-tech--that it couldn't quite bring itself to work.

Oh, on perfectly optimal loads, it was fine. If you filled it with a load of carefully selected, identical fabrics, it'd wash 'em up right good. It was fine, for instance, at washing "man-style," meaning you just dump all your stuff in and let 'er rip. But anything chaotic messed with it. Anything complex confused it.

Loads that mixed in towels with regular stuff? When it locked into its super-high-speed spin cycle, it'd get unbalanced, and the wash cycle would fail. Small loads, like, say a week's worth of my wife's delicates? It'd get confused, and the cycle would fail.

You'd come back an hour later, after running errands, and it'd be sitting there with an error code and a load of sopping wet, half-washed clothes. I read the manual, and--well--there was the rub. It was meant to do that. I adapted, modifying my loads, changing the way I washed clothes. It helped a little. I adapted again, learning how to manipulate the spin cycle. Now only every third wash would fail. Doing the laundry became a task that took all day, and took attention.

I finally called for support, and this being the 21st century, they ran a systems diagnostic. I held a phone up to the washer, and it uttered a stream of sound to a computer on the far end. Result: The unit was operating as designed. There was nothing wrong with it mechanically.

Only it didn't work.

And so a tech showed up, a couple of days later, to fix my washer. The "fix" involved opening it up, plugging in a drive, and downloading new software. It was, he confided in me, the fourth software update since the washer had been released.

I rolled my eyes, and after he'd left, started in on what I was sure was going to be a failed attempt at laundry.

It wasn't. The repair worked. The machine thrummed along through one load, then another, then another. No errors. No problems.

It was back in business, working exactly the way it should have worked in the first place.

And it struck me, as it often does, how much easier life would be if we worked that way. How many human beings really and truly don't have anything wrong with them, nothing at all, that a reboot and a software upgrade wouldn't clear right up?

A pity our wetware is so fiddly.

Published on September 22, 2014 15:08

September 18, 2014

Perfect Justice

Where is that place of justice, exactly, between you and I?

Where is that place of justice, exactly, between you and I?How does one find that perfect balance?

I found myself wondering that, for some reason, as I walked and thought about love and justice this morning.

The pursuit of justice is, after all, the pursuit of rights and equity. It comes when each has their rightful share, when none is denied what is theirs. It's a balance.

So in my mind's eye, I saw a table.

On that table, a bar of candy. Dark chocolate, preferably, maybe with a little bit of salt and caramel. Mmmmm. Chocolate.

Across the table from me sits Lady Justice.

"Hey Justice," I say. "I let's split that candy bar," and she's into the idea. She's fond of dark chocolate, after all. I pick up the bar, and then set it down again. I say: "We must each receive the same amount. It must be just and fair, exactly right."

She sits forward, takes up her sword, and gets ready to split it.

"Wait," I say. "I'm serious. Make it exactly perfect." Being Justice, she knows exactly what that means.

Perfectly fair can't be measured down to the gram, or milligram, or picogram. I'm not even talking about a one yoctogram difference, which is ten to the negative twenty fourth of a gram, the approximate mass of a single hydrogen atom.

This is delicious chocolate, after all.

To be perfectly fair, there can be no variance in the size of the pieces, no difference, none at all. If one portion has even the mass equivalent of the energy of one single photon at the height of the electromagnetic spectrum more than the other, then it is not perfect.

She looks at me funny, and then...lifting up her blindfold...stares with fierce intensity at the bar of chocolate. She stares deeply, her piercing focus growing more and more intense.

Finally, she looks up, a look of frustration in her eyes.

"But...each of the halves are giving off varying amounts of moisture, and are permeable to the environment. At every moment, they're sloughing off atoms and subatomic particles, varying in functionally unmeasurable, infinitesimal and chaotic ways. I can't possibly split it perfectly. It's not possible."

I give her a grin, pick up the bar, and break it in half, roughly down the middle. I hand her the slightly larger piece.

"Sure it is, dear heart," I say.

Love is more perfect than justice, after all.

Published on September 18, 2014 12:11

September 17, 2014

Encountering The Face of Islam

I was just popping by the store to pick up a couple of things on the way home.

I was just popping by the store to pick up a couple of things on the way home.It was just a short while before dinner, so I was in and out, quick as can be. On my way in, folks were handing out flyers as part of a food-drive for a local food pantry. It's a pantry run by the local Christian community organization, one that routinely volunteer for myself. I took a flyer, and then bustled about swiftly to snag the four items I needed.

Bam boom bing, and I was out.

On my way out of the supermarket, there was a gathering place for folks who were collecting food for said effort.

"Hey," said one of them, and it was someone I knew, a woman from the congregation where I'd interned as a seminarian O so many moons ago. We exchanged brief greetings, and she introduced me to her daughter.

My fellow Presbyterian wasn't the only one collecting food, though. There were other women there with her, from other faith communities. One of them was wearing a hijab, which I took...reasonably enough...to mean she was Muslim.

There the Muslim was, collecting food for those in need, right alongside the Christians, to support a Christian charity.

As I prepared to leave, another woman in a hijab came up and embraced the woman I'd been speaking with, and they laughed and smiled in ways that people do. The way that friends do, when they've not seen one another for a while.

There, in that encounter, was the face of Islam.

Sure, there are other faces, in the same way that Christianity has many faces. I have struggled, as a progressive who doesn't just reflexively kumbaya my way through my encounter with reality, with the Quran. It's a difficult book, if you read it honestly, as bright and fierce as the warrior-prophet who wrote it. It's like reading Deuteronomy and Leviticus and 1 and 2 Samuel--often not the gentlest of books, to be sure--rewritten in an Arab sensibility.

And of course, there are still other faces. There are those who emphasize conflict over hospitality, who have chosen not the path of spiritual discipline, but the path of human violence. We see them, disproportionate and unrepresentative, in the same way that all loud and angry people call attention to themselves to the detriment of the communities around them.

But Islam is not that. It is, more than anything else, a set of faith practices and disciplines. An Islam built on the five pillars--faith, prayer, charity, self-discipline, and pilgrimage--is a concrete thing. It's not abstract, or conceptual, or divorced from the reality it expresses into the world.

So there Islam was, laughing, embracing, engaged in acts of charity.

And as I drove away from that moment, it was a reminder: Others know the face of the God we worship by looking into our faces.

Published on September 17, 2014 13:54

September 16, 2014

The Terrible Secret of the Progressive Church

I have a little secret.

I have a little secret.For the last couple of months, I'd been spending some time in an online group comprised of self-identifying "Progressive Christians." It was interesting, but as the group grew and expanded into the thousands, the conversations became wildly cluttered and overwhelming, like the din of a roaring crowd at a concert.

Meaning, fun for a while, but a terrible place for a conversation.

One of the assumptions of that group--in fact, a fundamentally defining theme of that group--was the welcome and inclusion of LGBT folk. A huge percentage of posts and exchanges revolved around resisting those who exclude, and celebrating those who include. That was the focus, the place where all of the energy and passion lay. It was the great and defining struggle.

I understand this, and am sympathetic. When it comes to inclusion, ordination, and marriage equality, I'm there.

But I'm also aware that inclusion, ordination, and marriage equality are not my primary goal as a teacher of the Way. They cannot be, for a reason that we generally don't talk about.

The reason? Q-Folk are human beings, just as I am. Oh, sure, they experience gender and sexuality differently. But otherwise, they're children of God, formed of dust, breathed upon by the Spirit. Just like me.

I know this because I know them. They have been and are my co-workers. They are my family, my own flesh and blood.

From my experience, LGBT people are thoughtful and caring parents, beloved uncles and aunts, good bosses, and wonderful teachers. They make great friends and colleagues. They can be funny and creative. They can be thoughtful and precise. They can be spiritual and radically caring. They can be everything that a person can be.

Meaning: they can also be the opposite. I have had LGBT colleagues who were embezzlers, incompetent, and chronically combative. I have worked with LGBT folks who have betrayed their partners, and have lied about having cancer to falsely justify chronic absences from work. Lord have mercy, was she a piece of work.

You can be LGBT and a deeply unpleasant and selfish person. And you can be in between. What does that mean, on the far side of this exchange? What will the church that has welcomed in gays and lesbians, bisexuals and transgendered folk look like?

In that, I see a powerful analog in the full inclusion of women in the leadership of the church. For those fellowships that have moved away from that ancient bias, it was both absolutely necessary and simultaneously meaningless. It was necessary because including women's gifts and voices as full partners in the life of the Beloved Community righted an unacceptable injustice.

And at the same time, it makes no difference, because--for all of the heady abstraction of feminist theology--women themselves are not abstractions. They are human beings, children of God, complex and flawed and wonderful.

What women who rightly fought for a full voice are finding is that--well--the church is still the church.

So just as a church that has finally welcomed the sisters to leadership is still a corpus mixtum , so too will a LGBT-friendly church be a wild mix of saints and sinners. With that necessary righting of an injustice settled, it will still look EXACTLY like the church does now.

OK, perhaps a little more fabulous, sure. But at the heart of it, the same.

Meaning, the church will rejoice together and have pointless fights. People will build each other up, and tear each other down. There will be wonderful communities, and there will be terrible ones.

The need for reformation, for repentance, for learning and living God's love, and for mutual growth in the Way will remain.

Published on September 16, 2014 05:38