David Williams's Blog, page 75

January 19, 2015

Range Anxiety

A thought drifted through my head, as I walked the dog yesterday afternoon.

A thought drifted through my head, as I walked the dog yesterday afternoon.My little suburban neighborhood was, as it always is, full of cars. Cars parked in driveways. Cars on the streets. Cars are the lifeblood of our culture, rather literally, if you view our culture as one vast fungus-like organism. They are the red blood cells that carry the energy (that's us) to and from the different parts of the culture.

And I love cars, in the way that I did as a boy. Though my own four-wheeled vehicles are chosen for function, I enjoy them. I like feeling connected to a machine, feeling it as an extension of myself. It's fundamentally pleasurable.

But as I looked out at the cars yesterday, I could not escape the thought that every one of them will be functionally obsolete in 20 years. Here, the vast output of an industry, and all doomed to uselessness.

Why? Despite the absurd glut of cheap that is now pouring into our vehicles, the era of fossil fuels is finite. The end is visible. And yet as a society, we are not acting now, not in any meaningful way, to prepare for that reality. There's still profit to be made, and so we continue acting as if it doesn't matter.

There's not a single household in my neighborhood, for example, that has an electric car. Not one. Why? Well, because for now they're still very expensive. And two, well, we're convinced they're less practical. What if you run out of charge? What if you get stranded?

"Range anxiety," they call it.

What struck me, as I walked and observed, was how ironic this fear is in the broader context. Here we have a transportation infrastructure entirely reliant on a single source of energy. That source is finite. It will, in the lifetime of our children, be depleted to the point it becomes prohibitively expensive.

Writ large, we are radically reliant on a source of energy that is going to fail us, more completely than a Nissan Leaf crossing North Dakota in the dead of winter. It's that same Nissan Leaf, only with a single-use battery pack. We're going to be completely dead in the water. No gas in 10 miles? Heh. That's no gas for another million years, buddy. Recharging fossil fuels takes a while.

And yet if you look around our culture, we don't seem to feel that.

Not yet, at least.

Published on January 19, 2015 07:13

January 15, 2015

Giving Offense

I am free, should I so choose, to offend you.

I am free, should I so choose, to offend you.That freedom is an absolute, a fundamental part of our created nature. That you may hold a particular perspective or a particular viewpoint does not in any way impinge on that freedom.

Neither do my sensibilities define what you may or may not say. And you can say a great deal.

I believe in God. You can say that "god" is a projection, a stunted and archaic fantasy created by childish minds, no more real than the Easter Bunny, Elf on the Shelf, or Krampus. I am a person of faith. You may say that faith itself is monstrous and hateful and delusional, the source of everything wrong with humankind. I am a Christian. You may say that Jesus was a madman, a delusional, the hateful faux-avatar of a fevered desert "god." You may say that Jesus never existed at all. You may say that Christianity is a cruel blood cult, or a repugnant tool of the Man, a proxy for teaching weakness and submission to the oppressor class. I believe that God loves and welcomes all those who are governed by love, including gays and lesbians and the whole rest of the alphabet soup of contemporary academic genderbabble. You can call me an apostate and a heretic and hellbound.

You can say all of these things. You can write songs, and post videos, and draw cartoons. You can make polemic movies. They can be genuinely insulting and offensive.

You are free to articulate them, however and whenever you wish.

Because I am also free to ignore you. I can shake my head, or roll my eyes at an old familiar canard. But I do not have to receive your words and be stirred to anger. Neither do I need to react whenever I am attacked verbally. Your approbation means nothing, other than that you are expressing yourself. Which is your right.

I am, more significantly, also free to attempt not to give unnecessary offense when faced with opposition. That's a challenge, particularly when facing someone seeking an excuse to be offended. There are ways of thinking that take offense at the liberty of others, that deny others the very rights that are assumed for those in power.

If there is an injustice being done, or harm being inflicted, I can name it and resist it. But the ethos of my Teacher demands compassion, even for the uncompassionate, and justice, even for the unjust. Seek grace in all things, particularly in the defiance of brokenness.

If I feel you are erring, I may say so. But I will not actively try to weave dehumanizing mockery into those words, or to use them to inflict harm. Not that I'm perfect at it, but it's my goal. When I find myself messing up, I will self edit and self correct.

Should I be more offensive? Some suggest that's the way to get things done. But offense...if no connection is made to those who you are in tension with...does nothing to plant the seeds of transformation in them.

In my experience, it hardens, and radicalizes, and deepens the conflict, in a way that does not build towards growth and constructive resolution.

Published on January 15, 2015 04:40

January 12, 2015

Christian Multiversalism

Elsewhere on this blog, I found myself recently in entertaining and stimulating conversation about Christianity and universalism.

Elsewhere on this blog, I found myself recently in entertaining and stimulating conversation about Christianity and universalism.I've posted on the interplay between those two concepts on a variety of occasions. Universalism is a well-meaning, good-hearted theological yearning. It rises from the faith of those who know that God is love, and from that love the idea that any might be eternally damnificated seems anathema.

The conceptual problem with hell, particularly coupled with divine omniscience and omnipotence, is clear. It seems to infer a God who's a monster, who fashions creatures for the sole purpose of adding crispy-bits to some giant cosmic deep fat fryer.

Christians who are attempting to be orthodox and universalist, though, have the immense struggle before them of 1) asserting that God loves all beings and 2) asserting that God is neither zealous or just.

Universalism, in its simplest form, seems to imply that there's no variance in the character of the divine relationship with us no matter what we do. God is Love, whether we are Pope Francis or Pol Pot, whether we love and cherish others or we beat and humiliate and torture them.

On the one hand, that's true. On the other, it doesn't adequately grasp the terrible justice of God's Love. Fully knowing and participating in the other, sharing in the truth of their lives completely? No hellfire could burn the unjust and the cruel as painfully.

And there's always the whole "salvation through Jesus Christ" thing, which for Christians is a nontrivial thing. Did Jesus matter? Why? And if Jesus does not matter, what is the impetus for following him, particularly if it changes nothing at all? I can be a saint or a selfish, smug, libertine bastard. The God of universalism does not care. There is only love, and it's all the same in the end.

This seems problematic, and not just from the perspective of those who hold Jesus to be a magical talisman, a sacrifice whose mere existence absolves us of both sin and responsibility. It's also a problem if you care about justice, and about living out a life conformed to the radical compassion Jesus taught.

Most significantly, for those of us in my denomination, there was traditionally the challenge that came when the right-wing noticed you'd gone all mushy and UU-ish in your faith. Charges of apostasy and heresy can fly, and have flown, as fulminating folks fret ferociously about the decline of the faith. That happens less so now, as there's been a right-wing exodus, but it's still there.

So straight up statements of universalism are...difficult.

This whole thing strikes me as funny, because...well...what I believe is so much more heretical than mere universalism.

One advantage of being a functional nobody, I suppose. I pastor a sweet, gracious, small church. I go to few meetings and have no public face other than this wee blog and my sparsely-selling books. Ah well. It keeps me from being yet another thing for John Piper to anguish about, I suppose.

That heresy...and it is heresy, in the truest sense of the world...revolves around my understanding of creation. Along with a growing number of scientists, I hold that creation is not one linear time and space, but an infinite multiverse.

In our multiversal creation, I believe that God not only can save anyone, God does, actually and materially.

Does the Creator of All Things know what it would be like if every being lived fully in accordance with the Divine Intent? Absolutely. To say God does not...that God cannot...is an offense to both Divine Sovereignty and God's imagination. God both knows that, and makes it real. Is there any meaningful difference between the knowledge of God and existence itself? No, or God's knowledge of the true good would be no more real than our human dreamings.

On the other hand, I know that this creation is not that perfect realm. I know it because I, myself, am not that good. I am not, in my full self, conformed to the best possible self I could be. Here, I'm not talking "best self" in the sense of the health and wealth hucksters, the Osteens and the Oprahs.

I'm talking about being the self that lives fully governed by the grace and compassion of Jesus of Nazareth.

Though that is my metric, my goal, and my purpose, I am not that person. I do not serve Jesus as I could. I make choices, struggle though I might, that take me away from being that person. I know, just as surely, that the church is not perfect. It is a corpus mixtum, threads of gold woven amongst the mess of human community. And God help us, one look at our mess of a world lets us know that it is far, far from the best possible reality.

At every moment, the possibility of being that person...or of being a redeemed people...exists. It is fully known, fully in God's presence, as real as I am as I write this. As, at the same time, is every possible way we might fall.

We are both saved and damned, with uncountable gradations and in a fractal infinity of iterations.

Universalism seems, well, too small. A quaint echo of the modern era, with its linear thinking and pre-established narrative.

The divine work is so much more than that.

Published on January 12, 2015 06:43

January 10, 2015

Raif Badawi, Faith, and Liberal Thought

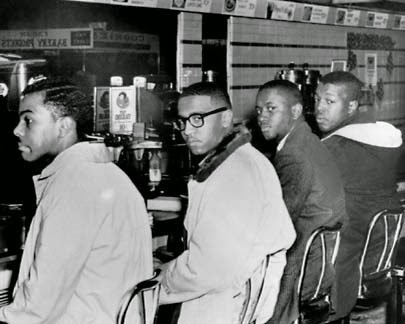

After writing yesterday's post reflecting on violence and faith after the Charlie Hebdo massacre, I was painfully reminded of how very real the dark confluence of political power and faith remains. Yesterday, I glimpsed a tiny blurb in the paper, less than a paragraph. It was the story of a Saudi man by the name of Raif Badawi who was to be publicly flogged. Fifty lashes, in front of a crowd, for the crime of "violating Islamic values and propagating liberal thought."

More specifically, Badawi created a blog called "Free Saudi Liberals," where he--as a liberal Muslim--engaged in free, peaceful, and open discussion about society and faith.

As rough as that might seem, it's just a drop in the bucket. These are the first fifty lashes of a thousand-lash sentence, to be carried out over the course of a ten year prison sentence. The quarter-million dollar fine, the Saudi state's forcibly divorcing him from his wife, and it's imprisonment of Badawi's lawyer for the crime of representing Badawi? Horrid, but almost an aside given the brutality of the rest of the sentence.

Here, a man who did nothing more than I am doing right here. He wrote about what he believed, about tolerance and a liberal approach to the integrity of other human beings. For that crime, he will be beaten bloody in public, given one week to recover, then beaten again, twenty times.

It reminded me of the above scene, only repeated, once a week for twenty weeks. Or twenty five weeks, as Jesus only gets forty lashes before the crucifixion.

What's remarkable, at least in my eyes, is how little play this is getting in the American media. In Europe, it's everywhere. In the Guardian. In the Telegraph. Our Canadian neighbors have noticed, and noticed the connection between Charlie Hebdo and Badawi.

But on the front page of American CNN? Nothing. Nothing on FoxNews, either.

Wouldn't want to offend our dear Saudi friends and business partners, I suppose. Especially after they've so nicely boosted our economy and punished Russia with all that cheap gas they're pumping.

Violence to silence speech is violence to silence speech, whether inflicted by terrorists or by a government. And whenever it is used to enforce a belief, that belief is inherently illegitimate.

If a way of life cannot stand on its own integrity, without the gun or the whip to coerce it, then it is a false thing.

Published on January 10, 2015 06:29

January 9, 2015

Religion and Violence

The followers of the Prophet Mohammed, peace be unto him, have a problem.

The followers of the Prophet Mohammed, peace be unto him, have a problem.It's a problem that surfaces again and again, headline after headline, as those who interpret Islam as requiring violence act out their interpretation. Villagers are butchered in West Africa. Bombs explode in crowded markets. Authors and cartoonists and filmmakers are murdered. It's ugly, and it's horrific.

Having read the entirety of the Quran, and read the Hadiths, and familiarized myself with the core of Muslim faith in my own secular study of religion, I see no reason Islam must be violent. It is not, as its most radicalized opponents assert, an inherently violent religion. That does not mean that I believe Mohammed, peace be unto him, was a pacifist. He was perfectly willing to pick up the sword, and did on a variety of occasions. In that, he was less like Jesus or the Buddha, and more like, well, the dude whose picture graces this blog. If the Quran is to be taken seriously as an authentic exposition of his life and teachings, he was a warrior prophet. Arguing otherwise is absurd.

But though he was a warrior, the faith that rests on his prophetic critique does not require war. The framework of the Muslim life is the practice of the five pillars. Faith in God, regular prayer, pilgrimage, charity, and the discipline of fasting? Do those things, and you're a Muslim.

Those are gracious, good, positive things. It's why so many millions of Muslims have no difficulty coexisting with their neighbors. There's nothing, nothing at all, in the deep and authentic practice of their faith that stirs them to violence.

So why this seemingly relentless drumroll of horror, which is doubly...no... exponentially more horrible to those whose practice of Islam leads them to live charitable, gracious lives?

The reasons are many. It's...complicated. Islam exists in a region of the world that is economically troubled, and that in the next century will become even more troubled. When the oil dries up, developed economies will transition to other sources of energy, ending the temporary growth that has made prosperity possible in that region. That, coupled with political oppression, the dark residue of colonialism, endemic unemployment, and climatic resource depletion? Things are going to be...messy.

But perhaps the greatest challenge Islam faces is a challenge that badly burned my own faith: the fusion of religion and the power of the state. For a millennia and a half, Christendom--the dominion of Christianity--was enforced at the edge of the sword. Faith and the state were one. The demands of faith are enmeshed with the laws of the state.

Whenever this is the case, religion becomes inherently violent, because the power of the state ultimately rests on the power to coerce compliance with a set of laws or social norms. It is why so many were butchered in the name of Jesus, to "protect the faith" from impurity. It was a horror, and one that Christianity must never forget.

If an individual can be imprisoned or physically punished for blasphemy or hewing to another faith, then they are living in a violent faith system. I think folks like Bill Maher or Richard Dawkins are fools, and radically misrepresent faith. But if a "Christian" government threatened them with imprisonment or sanction to protect my sensibilities, then my faith would be violent.

Therein lies the challenge for a faith tradition that exists in an area of the world where religion and the state remain dangerously entangled.

Published on January 09, 2015 07:54

January 7, 2015

Ethical Breeches

What are ethics? What is an "ethos?"

What are ethics? What is an "ethos?"Ethos has to do with our purpose, the great story that defines us. It's our worldview, that broad set of assumptions and expectations that we use to ground us and direct us as we try to make sense of existence.

"Being ethical," then, can be defined in many ways. Following the law is ethical...but what if that law stands in conflict with another, more radically defining purpose? Then, what is "ethical" becomes what is evil, as Huck Finn so pointedly wrestled with as he went down that river with Jim.

Huck looked at his own behavior...treating Jim like a human being...and realized that this made him, in the eyes of his culture, an unethical person. He was cool with that, mischief-maker that he was. To be "good," he had to violate cultural norms, and suffer cultural approbation.

In the little echo chamber of my dwindling, greying denomination, there's been an ethical scandal of sorts thrumming about. An initiative charged with the immense task of building up one thousand and one new worshiping communities had been achieving some measure of success, with hundreds of new gatherings created, gatherings which the Gospel is proclaimed and Kingdom communities have been created. I've worked with them, and they knew what they were doing. It's been a bright spot, in the often grim and sclerotic drabness of our denominational decline.

But now, we hear even that bright spot is tarnished. Significant actors in that movement have been found to have committed ethical violations, or so we're hearing. There have been articles, highlighting this violation. More accurately, there are the minutes of the meeting of an auditing group, in which those violations are detailed. There was outrage, and calls for heads to roll. "Oh, crap," I thought, when I first saw the headline. There's been stealing, or canoodling, or some significant misrepresentation. It was disheartening. So I went, and read it. Things seemed, well, murky. But there was a link to more detailed stuff, so there I went, to pore through those minutes. You need to read them, too. All the way through, drab as they may be.

There were violations of ethics, absolutely.

That is not at question. The issue: what ethics were violated? What is the ethos or worldview whose boundaries have been crossed through "...breeches of internal control," as the minutes so entertainingly mis-spoke?

Those are outlined by the minutes, and they are as follows: The violators created a nonprofit corporation in the state of California, whose sole purpose was to support the growth and development of new churches. The stated purpose for such a corporation: to protect the initiative from the very real vagaries of PCUSA budget shortfalls.

I read through the minutes, looking for something more. Where are the "new churches" formed for an evening in Vegas, ones that involved high-priced escorts and copious anointing with oil? "Worshipping communities" that were a euphemism for "me and my bros worshipping my schweet schwaggy new Lexus?" Nope. Nada.

There wasn't a thing. Man. Can't we Presbyterians even manage to create interesting scandals? Jeez.

The violators created a nonprofit organization to help establish and teach gatherings of human beings following Jesus Christ. Period. Maybe there was more. Maybe there are things left unsaid. Perhaps there was malfeasance, or self-dealing.

But I cannot speculate on that, nor would such whispering gossip be reasonable or Christian.

What, then, is the nature of the primary ethic that has been violated here? It is the ethic of organizational command and control, a purpose formed around the structures of accountability and oversight that came to define twentieth century Presbyterian life. Carefully considered church policies, procedures, and protocols were ignored. The agency responsible no longer had controls in place, or ways to oversee the new organization. Shortcuts were taken. There were liability concerns. There was inordinate risk exposure, which was inappropriately managed. There was the potential for confusion, the misuse of logos and the potential besmirching of corporate reputation.

From the ethos that views church organizationally, where the values that are primary are systems of accountability and adherence to established procedural protocols, then, this was a significant failure.

What ethics were not violated, not by any observable measure or by any report?

The Great Commandment and Great Commission, that ethic of creating more followers of Jesus of Nazareth, and doing so expeditiously and with good intent. There's nothing, not a whit of a hint of a trace of anything in the minutes describing this report that would suggest otherwise. A short cut was taken, and conversations not had, in a system not exactly known "reputationally" for its agility. People saw a way to make a needed thing happen, and did it. That's it.

Outside of the PC(USA), in the world of evangelical Christianity, such an action wouldn't even draw a blink. Create a bona-fide not for profit corporation, to operate in partnership with a church to further a particular end that transcends the church itself? Heavens forfend.

Again, I will accept that perhaps that may change. Further investigations may prove that there was malfeasance, or the intent thereof.

But given what is known, the disjuncture between those two ethics hit me, hard.

They can sometimes play well together, as accountability can be a powerful servant the integrity of the Gospel. Bad things can happen if we are not wise and prudent.

But having been a Presbyterian my whole life, I know all too well that is not always the case. Bad things can also happen when we are graceless and unwilling to trust one another. Structures of distrust can become the point and purpose of our lives together.

Has that happened here? I struggled with it, for a while.

Two scriptures rose up, as I thought on this. First, that time the disciples came charging up to Jesus, incensed that someone who was not part of their circle was out there preaching and spreading the word. Who the hell is this guy? What right does he have! Stop him!

Jesus, as I recall, did not seem too concerned with misuse of logos or "reputational risk." He asks: Is that man doing the work of the Gospel, in a way that would be self-evident to any disinterested observer? If so, fine. Go team go.

The second scripture had to do with risk. Right there in the lectionary the week the scandal hit, there it was. The master, and his talents, and the three servants. The first two servants go big, and take risks, and bring a return.

Then there's the Presbyterian.

The Presbyterian presents his master with a ten year plan, a risk assessment review cross referenced to the Book of Order, a seventy four page draft investment management protocol, and the minutes for the five committee meetings to develop the aforementioned protocol before the second reading, which has been postponed to the January meeting pending signoff from legal counsel.

And buried under that great orderly stack of paper and procedure, the single talent, unused, ungrown.

Sigh.

Published on January 07, 2015 10:05

December 17, 2014

The Jobs Young People Don't Want

Full-time employment, as we well know now in our duct-tape kludged economy, ain't an easy thing to come by. It's particularly, brutishly so for twenty and thirty somethings, who often cobble together their lives with part-time employment here and there.

Full-time employment, as we well know now in our duct-tape kludged economy, ain't an easy thing to come by. It's particularly, brutishly so for twenty and thirty somethings, who often cobble together their lives with part-time employment here and there.Which is why an article in yesterday's Washington Post struck me. Though young folks might be struggling, what they aren't particularly interested in are Federal government jobs. There are a range of reasons for this.

Among them are the culturally reinforced sense that the gummint ain't to be trusted, that it's ineffectual, that it's a sprawling, soul-crushing bureaucratic nightmare, an endless morass of silos and turf wars and dizzying, Byzantine requirements.

This isn't entirely true, but neither is it entirely untrue. Layered on top of that comes the financial uncertainty of an institution in decline, as positions fall and fade away, with those who remain clinging doggedly to their jobs.

Layered on top of this, in order to enter this Fun Land of Big Joy and Happiness in the first place you have to negotiate a hire process that is so opaque, clumsy and slow as to render it almost inert.

I have often noted that while contemporary nondenominational Christianity has embraced the values of the marketplace, we old-liners still mostly emulate the structures and dynamics of government.

So when it comes to bringing new voices into the mix, it occurs to me that we have precisely the same problems as government, for the same reasons. Having been through the Presbyterian process, I can say without question that it is not the sort of thing that resonates with the kids these days. They're just not hip to it. It's not groovy, man. It's, like, totally gnarly, dude. OMG.

Which is why, though I'm forty-five years old and there's white in my beard, I look around at meetings and note that I'm still one of the "young ones."

This is not a good sign.

Oh, I was young when I started. I was twenty eight, which didn't feel young at the time. By the time I was done, I was halfway through my thirties. Having committed myself to avoiding the call-sucking siren song of debt-financed education, it took me seven years to negotiate the process. Those years were good, and many of the relationships and conversations I had with those charged with walking me through that process were positive, both testing and affirming my call.

But those years were also layered with duplicative toils, sudden snares, and dangerous oversights. A few examples:

Toils: On the one hand, we Presbyterians are obligated to have a seminary degree, with tests and exams and the like, administered by professors at accredited institutions. On the other, we're required to take Ordination exams that mirror the contents of that education. I never understood the logic of this. If I've successfully completed biblical coursework from an accredited institution, why take yet another exam? I know the counterarguments: that seminaries are inadequate, that Ords provide uniformity. But then why require seminary, if we're so convinced it is inadequate? And why pretend that the Ords--graded by laity and pastors--are more "uniform?" They are, in my experience, just as subjective.

Snares: Five years in, my committee--whose membership had rotated several times--suddenly informed me that I needed to get forty hours of clinical pastoral education. Was it required by the denomination? No. Was it a presbytery requirement? No. Had it been discussed, ever, up until that point? No. Was I pursuing a call to be a hospital, military, or hospice chaplain? No. I was working, and in seminary, and had two young children, and was interning in a congregation. I could see no clear connection between this requirement and the realities of congregational leadership, so I demurred. If this was to be a requirement, I could not fulfill it. Had the issue been pressed, I would have removed myself from the process. It was not, thank the Maker. This happens often, not out of malice, but from the clinical remove a committee often has from the reality of those they are shepherding and testing.

Dangers: In the seven years it took me to negotiate the call process, I was never required to show my capacity as a preacher or a spiritual leader of people. I never preached. I never demonstrated that I could teach or lead a gathering. Not once. There were a lot of papers and essays and forms and meetings. But not nearly enough of it directly spoke to the skills required to preach and teach the Gospel and energize a community. This is dangerous, because it sets up an expectation on the part of a candidate that they've got the skill set that resonates with a congregation...when in fact, they have not.

More dangerous still, our processes bear little resemblance to the shattering, transformative experience of call itself. You know, call? When God shows up in your life and demands it? That's the stuff of dreams and visions, of the fire that gnaws at your bones. If we confuse test taking and process management skills with call, we set up a dangerously inaccurate misunderstanding, both for our churches and for those testing their call.

Years of requirements, many of which have no meaningful connection to the spiritual and material demands of our vocation. Thickets of uncertainty. A debt financed education. And ultimately? Once you've gotten through that?

It begins again, with the wildly clumsy and uncertain process of seeking a call.

And we wonder why younger folks steer away.

Published on December 17, 2014 06:21

December 16, 2014

End Game

It was in the midst of a conversation with friends that it hit me: we're entering the end game.

It was in the midst of a conversation with friends that it hit me: we're entering the end game.We'd been debating the merits and challenges of autonomous self-driving vehicles, which segued into conversation about plummeting gas prices.

Somewhere in that free-form conversational cascade I was walloped by the realization that the recent wild drop in prices is an early harbinger of the end of the fossil fuel era.

It's just so damnably counterintuitive. If fuel prices are low, one would assume that its a mark of plenty, of overabundance, of resource more than the market can consume. That's a gusher, we cry, as black gold comes blorting out of the earth, endless and plentiful.

Yay, we proclaim! Good times!

But why, we must ask, are prices so low now? It is tempting to weave some wild conspiracy theory. It's the West and the Saudis conspiring to punish a restive and expansionist Russia. Or maybe it's one of the outputs of the January 19, 2014 annual meeting of the Order Illuminatus, designed to quell an increasingly restive post-industrial populace.

I missed that meeting, but I swear, it was nowhere in the minutes I received by carrier raven.

The reason is rather different, and while it's complex, it's entirely in plain sight.

They are low because humanity has begun aggressively tapping the very last and most demanding points of access for crude.

Tar sands and shale are far more technically challenging, and extraction is both much more polluting and much more expensive. But if oil companies did not pursue those techniques and engage those resources, they wouldn't be in a position to continue business when the deepwater wells and desert fields start running dry. Which they will.

At the same time, traditional methods of accessing oil have continued. It's getting increasingly difficult to access crude using traditional methods. Maintaining current production levels in oil fields is getting harder and harder, demanding more investment and more rigs than ever before just to keep pace. But production continues, as it will right up until the fields begin to run dry. So we have doubled-down old-school drilling and new, more demanding processes, laid one on top of another. Now, in this moment, this duplication of techniques means production is artificially high.

This will not last. Oh, sure, a couple of years, perhaps. Five, maybe ten at the top side. And then, the slide begins, to which industrial society must either adapt or perish. If I live as long as my grandfathers, that time of energy famine will be within my lifetime.

One might think that traditional production methods would have been cut back, reducing supply to maintain price levels and conserve resources, giving us precious extra years to adapt and develop new technologies.

But playing against that has been the increasing focus on efficiency, which coupled with a bump in prices has reduced demand. If prices stayed level, demand might continue to decline. OPEC knows this, and is maintaining production for the sole purpose of putting economic counter pressure on the movement to greater efficiency. Greater efficiency reduces dependence. Reduced dependence reduces near-future profit margins. So...drill baby drill. Baby needs a third Bentley.

It's working, at least for now, as sales of large SUVs and inefficient vehicles have started ticking up. No one ever went broke overestimating the stupidity and shortsightedness of human beings, as the saying goes, and this appears to again be the case.

So we have this hump, this spasm of production and consumption. It is utterly irrational, mindless in the way that short-term profit-driven market economies are mindless.

In five years, things will look very different.

Published on December 16, 2014 06:11

December 15, 2014

Being The Machine

Around the dinner table the other night, on one of those rare evenings when the scramble of activities waned enough to allow us to sit together, the family was discussing the ethics of artificial intelligence, and the inexorable rise of sentient machines.

Around the dinner table the other night, on one of those rare evenings when the scramble of activities waned enough to allow us to sit together, the family was discussing the ethics of artificial intelligence, and the inexorable rise of sentient machines.I was contending, as I often do, that synthetic sentience would have the capacity to be considerably more moral than humankind. One of the greatest barriers to the human ethical life is our inability to really know the truth of our relationships. Through observation, imagination, and the workings of the Spirit, we can kinda sorta approximate what others are feeling.

But we don't know it. We don't actually feel it and remember it ourselves. AI would have that capacity.

As I defended that position, the classical counter-position was expressed. What if artificial intelligence simply did not care for human life at all? If it had interests and drives that were utterly alien to our own, and human life--all life--was meaningless to it? Or an inconvenience, to be brushed aside?

That, I think, is the lurking fear of Stephen Hawking and Elon Musk. Here we are, just an blink in the evolutionary timescale away from this new and alien form of half-awareness. It would be un-life, cold, dispassionate, empty of any care for anything but its own inhuman interests.

Honestly, though? I think this is what they call "projection." Meaning, that form of creature already exists, and we are it.

Not us individually, not for the most part. But taken together, in the vast quasi-sensate macro-organism that is late industrial society, we already live as if we were part of such a thing.

There are many ways that this is true, and it is hardly a new observation. But I was reminded of this again recently, as I rode home from church on my trusty, well-worn Suzuki. It was late, and it was dark, and I was being cautious.

It's deer season, and the absence of any significant predators the population of deer has exploded. At night, and even during the day, caution is required. This is particularly true if you're on two wheels. If you're not encased in a cocoon of steel and alloy, just out there in the wind and the cold, fragile and alive? Deer strikes aren't just an annoyance. They are more....existential...than that.

So I keep the pace down, my high-beams up and on whenever possible, and my situational awareness turned up to eleven.

On a long open stretch of River Road, wending its way through forest along the march of the Potomac, ahead of me in the darkness was a current-gen Prius. It was moving at the sort of modest and socially acceptable pace one expects from such a car, fifty to sixty, a little over the limit, just like we all drive.

I spotted the buck and the doe came out of the woods on left, two hundred and fifty yards ahead, moving slowly. I got off the throttle, falling back. To my surprise, the Prius did not slow at all, pulling away and towards them. Perhaps the driver simply did not see, or was momentarily distracted.

The deer crossed in front of the oncoming car, first the buck, then the doe, a yard or two behind. The driver decelerated late, very late, not particularly abruptly, not a panic stop at all. They saw the buck only, perhaps. The driver may have been unaware of the doe's presence in the huge A-pillars of the Prius.

"Dude, slow down," I said, to the inside of my helmet.

They didn't. They hit the doe at about thirty five to forty, right front bumper striking hard, tossing the body of the animal up and over. The car slowed then, a little more, not ever completely stopping, and then continued on.

The aftermath was brightly spotlighted in my headlights. The doe was a ruin, but not dead. It's entire hindquarters were...wrong. Both legs, clearly and multiply fractured, a hundred joints, a mess of bones and hide. It twisted and writhed at the side of the road, a living thing broken to dying, and flopped wildly into the road in front of me. I arced around it, carefully, as it wildly flailed in what would be a slow, painful death.

Only very rarely do I wish I carried a gun. This was one of those moments.

Why did that creature die as it did? No reason at all. Like the two other deer corpses I passed in the remaining twenty five miles of my ride, it was not prey, not part of that bloody but comprehensible Lion-Kingy circle of life. It did not die at the fangs of a wolf, or consumed by the invisible predation of microorganisms. It was not hunted.

It was just crushed underfoot, incidental damage from a process so removed from the process of organic life that it may as well have been artificial.

In that, it is not so different from human lives, which matter...in the great automaton of our culture...really very little at all. If we fall broken by the roadside, what does the blind mechanical god we have created care? That "invisible hand" will not be extended to lift us up. Onward it will go. We know this. It's why we are so anxious.

Afraid of artificial intelligence? Why would we be? It could be no worse than the thing we have already become.

Published on December 15, 2014 04:44

December 12, 2014

Kurisumasu ni wa Kentakkii!

As we bustled about, my Jewish children helping assemble the ancient plastic tree that has graced their grandparents house since the mid 1970s, my sixteen year old son gave me a grin. It was that grin kids get when they realize they know something their parents don't.

As we bustled about, my Jewish children helping assemble the ancient plastic tree that has graced their grandparents house since the mid 1970s, my sixteen year old son gave me a grin. It was that grin kids get when they realize they know something their parents don't."You seriously haven't heard about KFC? For Christmas? In Japan? Seriously?"

I said, um, no?

"Oh, man. The Japanese aren't Christian, pretty much none of them. But they celebrate Christmas by all going to KFC. It's like this huge thing. Like, everybody goes. You totally need to look that up, Dad."

And so I did. And as I goggled at the peculiarity of it, I thought, dang, how did I not know this?

It was both very strange and oddly familiar.

It was both very strange and oddly familiar.Very strange, in the way that seeing elements of your culture sorted, adjusted, and modified through the lens of other cultures is invariably bizarre, a funhouse mirror. Corporate culture, of course, is gleefully willing to spread itself. It's aggressively viral, embedding and adopting and engaging itself with every other form it encounters.

Still and all, seeing the features of our seasonal festivities threaded into another culture is odd. Odder still is that there is absolutely zero connection between this event and any Christian connection. None whatsoever. Japan has some small Christian communities, but they're in a tiny minority.

What happens in Japan on Christmas doesn't have the character of European or Slavic Christmases, which arise from a long, complex, and historic connection with the faith. Neither does it resemble the traditions that have arisen in Latin America, or in Africa. There is no faith component at all.

It's the sort of tradition that arises solely from a particularly successful ad campaign, intentionally designed for a particular culture. It is pure, unadulterated, uncut secular Christmas.

In that, it is remarkably like the Christmas we Americans can all observe around us right about this time every year. Just a slightly different white guy with a beard.

Man, this planet is a strange place.

Published on December 12, 2014 05:04