David Williams's Blog, page 74

February 7, 2015

Being Blind to History

The shoutfest about the President's recent comments at a prayer breakfast have me genuinely confused. In condemning ISIS/IS brutality, he noted, briefly, the dark stain of violence that has colored the past of many faiths, his own included. He called for people of every faith and tradition to resist violence, and to seek the best in their faith.

The shoutfest about the President's recent comments at a prayer breakfast have me genuinely confused. In condemning ISIS/IS brutality, he noted, briefly, the dark stain of violence that has colored the past of many faiths, his own included. He called for people of every faith and tradition to resist violence, and to seek the best in their faith.For which, of course, he was attacked, through the thoughtful medium of the twitterverse. What better way to capture subtlety than in a single 140 character blort of blind, thoughtless outrage?

He was critiqued for mentioning the Crusades, and of the use of twisted scriptural interpretation to justify racism. These things happened, of course. They were real, historical, actual events.

And honestly, things go deeper still. Crusades? Racism? Pish posh. Those are just the familiar ones, the easy ones. We've done plenty more.

There was the Thirty Years war, of course, a sustained period of violence and bloodletting in Europe back during the 17th century. That involved witch hunts, heretic torturings, and all manner of creative horror putatively in the name of Jesus. Torture chambers, lined with bible verses? They were there, and that's taking Sunday school to a whole 'nutha level. It was right there.

Or the subsequent Marian persecutions in England during the reign of "Bloody" Mary, who publicly burned and drew and quartered Protestants by the score in the 16th century. Oooh, except for that one guy, who was midway through being burned when someone decided to hurry things along by bashing in his skull. That'd have made a hell of a Youtube.

Or the unpleasantness of Oliver Cromwell's Protestant roundheads, who executed Catholics, including one whose execution was so badly botched that the victim got up from the chopping block after several tentative strokes and demanded that the headsman just do his **** job already. Back and forth, bloody and brutish, a horror almost beyond our capacity to grasp. All Christian, or putatively so.

Even we Presbyterians have pitched in on occasion. I've read and studied John Calvin, the founder of my wing of the reformed tradition, and I totally appreciate some of the aspects of his theology. Some. Others, not so much. But I also know that he was a significant part of the process that ended when Michael Servetus, a "heretic," was burned alive. For what? For being a Baptist and a scientist, basically. For not believing correctly. That was it.

Had Jefferson, Washington, and Franklin lived in Geneva at the time and believed what they believed, I'm reasonably sure Calvin would have killed them too.

And that's perhaps most insane about the knee-jerk anti-Obama response on the part of the far right. It is not that they're riled that he mentioned some of the mess of our past. It's that their response is also fundamentally not conservative. Neither is it American, not if the history and purpose of America as a republic has any meaning. They're so eager to score points that they're happy to score own-goals. They are so blinded by outrage that they don't see how much they betray the very principles they claim to defend.

I don't buy the hagiographic golden-city vision of America's past, because I'm not an idiot, but neither will I reflexively attack everything about this country. There were seeds of enlightened goodness there.

One of those seeds of goodness was the flight from religious oppression, from a place where nominally Christian religious violence raged to a place where religious oppression was fundamentally against the law of the land. We've struggled at times to live into that, but it's right there in our founding. Where we've failed, acknowledging that failure is the best and only way to ever improve. Acknowledging you have a problem is step one, eh? You can't repent and change if you don't recognize your sin, to put it another way.

So here, a president evokes America at her still-striving best, the best hope, the goal towards which we yearn. He acknowledges where we've been, and affirms our hope as a nation to transcend that blight of violence and oppression. And he gets flack for it.

Bizarre.

Published on February 07, 2015 05:58

February 5, 2015

The Dark Fire of Reciprocity

As happens so often when I encounter an act of monstrousness, my thoughts turn savage.

As happens so often when I encounter an act of monstrousness, my thoughts turn savage.The images of that Jordanian pilot being burned alive in a cage? They were the heart of human brutality and evil. Here, an act of torturous hate, a mother's son helpless and forced to die in carefully calculated and choreographed agony.

I see it, and...as with the horrors committed by Boko Haram...I feel, briefly, the touch of the fire of that hatred. The rage of it. I see an atrocity, and my heart leaps to atrocity.

Burn them. Burn them all. Expunge them from existence. Wipe the planet clean. I stop short at reviewing the square kilometers of ISIS controlled territory and calculating the megatonnage required.

I step back, and remember who I am. I give thanks that I am human, and insignificant, and not empowered to act on rash impulse.

Nothing diminishes the evil of this act. Nothing.

Oh, sure, it's been done before. Medieval re-enactors may not feature this element of that culture quite so prominently, but Western culture was just as heinous five hundred years ago. More so, if we study the history of our killing. That means nothing. It was a horror then. It is a horror now.

I anticipated...exactly...the response of ISIS. I could feel that rationale, the logic behind it. The burning death of this man, they are arguing, is no different than the burning deaths of our own people when the bombs fall from the planes. Mumathala, they call it. "Reciprocity." We are doing to him what he has done to us.

And which will be and is being done to them in return.

And returned again, payments back and forth, an economy of fire and blood.

I will do to you what I believe you have done to me.

It is not justice, not the justice of God, not the justice that heals and restores.

It is nothing more than the dark fire of our mortal sin, burning, ever burning.

Published on February 05, 2015 05:12

February 4, 2015

Tribes and Tribal Gods

It's peculiar, of late, the degree to which the idea of tribalism has been surfacing in the world. With every act of brutality on the part of ISIS, every act of monstrousness from Boko Haram, every dark and unpleasant bit of nastiness out there, it seems tribalism is to blame.

It's peculiar, of late, the degree to which the idea of tribalism has been surfacing in the world. With every act of brutality on the part of ISIS, every act of monstrousness from Boko Haram, every dark and unpleasant bit of nastiness out there, it seems tribalism is to blame."It's these backwards monsters and their tribal God," or so goes the refrain.

"Tribal" becomes shorthand for insular, stunted, and ignorant, snarling clans of highlanders ever butchering one another, the Hatfields and the McCoys firing potshots. It is juxtaposed with the deep virtues of modern and "postmodern" thinking. We are, after all, the ones who make decisions based on reason and enlightened self-interest.

We're not tribal.

Perhaps that's true. But as much as the concept of the tribe has been getting bad press lately, I think it's not entirely deserved. I think that, mostly, because of my recent doctoral research into the dynamics of small faith communities. Sure, little gatherings can be bitter, unpleasant, and toxic. Tribal relations can be messy. But not every church-tribe is Westboro Baptist.

Small communities can also be healthy and warm and gracious. They can be places of learning and mutual support. They are places of belonging, of the interrelationship of persons on a profound level.

Tribes are the intimate communities--by affinity or by kin--that constitute one of the most elemental forms of human relationship. They're missing, to large degree, in our broader society, where we are fragmented off into demographic silos, or regimented into systems and structures that are resemble industrial production.

These are certainly effective and efficient and convenient. But they are not organically human.

As Carol Howard Merritt pointed out in her book (can I call it her "classic book" yet? hmmm) those alternate systems of organization tend to leave us hungry for ways of being together that resonate more with our essential humanity. In this shattered, diffuse, scattered age, that's a major

So when I hear "tribal" described as functionally synonymous with "ignorant" or "violent," I rankle a wee bit.

Sure, a "tribal god" is a problem. But only if the tribe is the god.

It is equally a problem if a nation is the god. Or an ideology is the god. Or if we ourselves are the focus of our worship.

Six of one, half dozen of the other.

Published on February 04, 2015 13:51

February 3, 2015

On Being and Not Being a Feminist

I am a feminist.

I am a feminist.And I am not a feminist.

Both of these statements are true.

I am a feminist, even though I do not typically choose that language to describe myself.

Female human beings are absolutely and equally human beings. Their value lies in their inherent personhood. Oppression of women, be it in the workplace or in education or in relationships? Unacceptable. Violence against women is violence, and assaultive/predatory behavior towards women is both monstrous and wrong.

I reject, completely, the idea that women are in any way subordinate to men. Women have been and will be my teachers, and my mentors, and my spiritual guides.

Women should be compensated equally for equal work, and a just society should be structured in such a way that this is possible. Women with the gifts for leadership, and there are as many as there are men, should be in leadership. Women who choose to nurture and raise children as part of a traditional family structure should be honored for that choice. Women should be lawyers and doctors and artists, counselors and engineers and programmers, legislators and pastors and owners of small businesses. What matters is that they are pursuing their best vocation.

I reject the idea, in point fact, that any work is inherently "women's work." Women, being, you know, human and all, are called to do many things. And work is work. In the quest for a balanced and sane existence, I have been willing to seek my calling in part-time work, allowing my driven, smart, and highly-capable wife to pursue her career. So I do laundry, make dinner, do dishes. I changed diapers, I vacuum, and care for and help nurture our kids. A task is a task.

I see how women and girls are treated in our culture, objectified and commodified, and I recoil. I see their basic personhood diminished or delimited, and I will not stand for it, or allow that way of thinking to take root in the boys my wife and I are raising.

In that sense, meaning the practical, material, actual commitment to the rights and personhood of women, I am a feminist.

But I am also not a feminist.

I am not a feminist because I have stood in close encounter with feminism--not as an interpersonal and cultural practice, but as a system of thought arising out of academe--over nearly two decades of engagement with higher education. Having studied and engaged with academic feminism, I do not share its semiotics or its worldview.

Though I can speak it, the language of academic feminism is not my language. I do not find it either compelling or transformative. I do not talk about patriarchy as a way of framing all oppression, or view the entire world through the lens of gendered discourse. I do not conceptualize the good in gendered terms, with the feminine as proxy language for the good, and the masculine understood as inherently oppressive. It seems...counterproductive.

And joyless. And drab. And devoid of rhythm, power, and poetry. Having studied faith, such a radicalized and binary view is alien not just to my faith, but also to those indigenous faith traditions that embrace the divine feminine and its lifegiving relation with the divine masculine.

The worldview of academic feminism is also not my worldview. Academic feminism as I have encountered it manifests as an ethic of radical particularity, of fragmentation, a house endlessly divided. Part of this is, frankly, a function of academic discourse, in which seeking and creating "new" categories is the only way to get published. But when that reality is applied to a philosophical and ethical system, that has impacts. Academic feminism is a fundamentally particularizing ethos, meaning it understands "truth" as residing in the particularity of socially mediated identity. Men cannot understand women, because they are not women. Women privileged by education and the absence of oppression cannot understand those who are not, because they do not share their social position. White women cannot understand women of color, because they are not women of color. Cisgendered womyn-born-womyn cannot understand gender-variant women. And so on, and so forth, in an endless fractal splitting.

Then there's the "liberality" of it. For all the fulminations of the reactionary right wing, feminism isn't liberal. It may be leftist, but it is also fundamentally and explicitly illiberal, viewing individuals through the lenses of the categories they inhabit and not as who they are as sentient, self-aware, and free beings. Take, for instance, the manner in which this perspective may be dismissed on the basis of a sequence of labels. I am a privileged white male, speaking from a hegemonic patriarchal perspective. I am a contextual node. What I am not is a person.

And yes, I know, this was done to women for millennia. It's my turn to sit down, shut up, and listen. But that assumes I have not been listening, and that I, as a human being, am just representative of a category. It returns evil for evil, as my faith tradition puts it, which is sort of a no no.

Contemporary academic feminism speaks the language of othering, explicitly and intentionally devoid of the universals that provide the conceptual bridges for the heart's compassion. It is a mass of triggers and umbrage, harder to negotiate than a minefield. I do not find it gracious, welcoming, or useful. How could I, when the concepts of "utility" and "purpose" are fundamentally antithetical to academic feminist discourse?

So I am, and I am not, a feminist. In the abstract, academic, philosophical sense? No. I am not.

But yes, yes I am, practically and materially and interpersonally, socially and culturally.

Given that doing and being is more important than abstractions and semantics, I think I'm comfortable with that.

Published on February 03, 2015 06:23

February 2, 2015

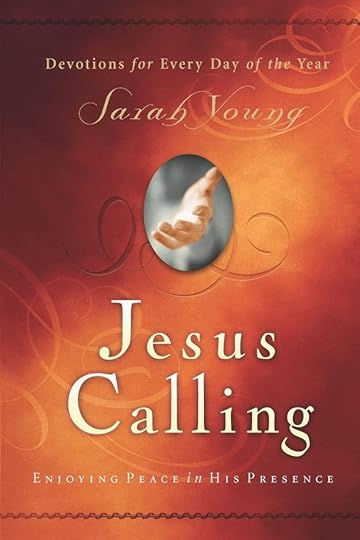

Jesus Calling?

It caught my eye because it was the single best selling Christian book this last year, racking up a whopping ten million sales.

It caught my eye because it was the single best selling Christian book this last year, racking up a whopping ten million sales.Jesus Calling, it's titled, and it's a yearlong journey of daily devotionals written by a Christian missionary. It's an...interesting book. The author, having maintained a journal of her daily spiritual reflections, decided to write them out as words from Jesus. Meaning, the book is intended to be not her words, but the words she has received directly from Jesus, every day.

Like I said, interesting. Interesting enough that I snagged an ebook version of it...it's checked out of every library in the county. Or, rather, I snagged a sample, meaning the introduction and the first month of the devotional.

Enough, I think, to have gotten the flavor of it.

Working my way through the introduction, it felt accessible and straightforward. I learned the author had attended Wellesley, and gotten her masters from Tufts, which surprised me a wee bit.

Then it began getting odd. Familiar, but odd. After her conversion experience, she began working with evangelical and charismatic missions in Australia, and specifically counseling women in a Christian counseling center. It is at this point that she begins encountering what she describes as spiritual assault, engaging in spiritual warfare with powers that were threatened by her ministry.

And then she starts talking about how important her spirituality was in helping her to work with a client who was recovering from both incest and...satanic ritual abuse.

"This form of Satan worship involves subjecting victims (who are often very young children) to incredibly evil, degrading tortures," she shares, in a matter of fact sort of way.

What and the what? This, in the bestselling Christian book in America in 2014? Satanic ritual abuse? My gracious, we really aren't at Wellesley any more, are we, Toto?

This was a big thing back in the 1980s and 1990s, sure. Much of charismatic evangelical Christianity was in full panic mode about a vast global conspiracy of Satanists, who did horrific things in secretly monstrous rituals. Which would have been horrible, sure. Had it actually happened.

Which, it, um, didn't.

It was a panic, a collective delusion, born of paranoia and a hyper-spiritual worldview that had folded in on itself and divorced itself from the reality of God's creation. Victims recounted stories of abuse that, upon actual examination, proved to be what amounted to implanted memories, embedded in damaged souls by "counselors" who were so eager to find abuse that they found it everywhere they looked.

So the book begins with, among other things, an uncritical recounting of a discredited fabrication? Lord ha' mercy.

I read on, working through that first month with the taste of several grains of salt in my mouth.

And despite that really, really awkward and jarring note at the beginning, it wasn't terrible, or evil. Sort of pleasant, in an encouraging, uplifting sort of way. Sure, it didn't sound all that much like the Jesus I know. There weren't parables, or stories, or complex explications of the interwoven nature of our identities and that our Creator.

Just words of encouragement and support, mingled in with an inspirational passage or three each day.

Was it Jesus talking? Well, no, not technically, not in the unmediated-direct-line-to-Jesus sense of it. I just don't buy that, any more than I buy any assertion without critically assessing it.

But was it morally or ethically antithetical to the teachings of Jesus? No. No it wasn't.

So, the way I figure it, it sort of is Jesus, in the way that every one of us who follows him is Jesus. Taken that way, it wasn't half bad. Not really my cup of tea, but so it goes.

Published on February 02, 2015 08:46

January 29, 2015

Faith and Brokenness

Twice in the last week, it's surfaced in conversations or readings or multimedia, this peculiar relationship we Jesus people have with human brokenness. That we're kind of a little messed up as a species is one of the roots-rock assumptions of Christian faith, and one that I honestly resonate with. We mess things up constantly, as our hungers and angers and anxieties and desire for control lead us to inflict all manner of harm to one another. We're capable of compassion, but we also live behind existential walls, and become so folded into our own subjectivity that we fail to see others as they actually are. Ours is a world of shadows and projections, which become the ground for both our own self-wounding and the injustice we inflict on one another.

Twice in the last week, it's surfaced in conversations or readings or multimedia, this peculiar relationship we Jesus people have with human brokenness. That we're kind of a little messed up as a species is one of the roots-rock assumptions of Christian faith, and one that I honestly resonate with. We mess things up constantly, as our hungers and angers and anxieties and desire for control lead us to inflict all manner of harm to one another. We're capable of compassion, but we also live behind existential walls, and become so folded into our own subjectivity that we fail to see others as they actually are. Ours is a world of shadows and projections, which become the ground for both our own self-wounding and the injustice we inflict on one another.The heart of who Jesus was...his work in the world...is God's restorative and redemptive intent for all of us. Christianity operates under the assumption that there's something not quite right, something in need of transformation and growth and healing.

Which is why I struggled mightily with two different perspectives offered up this week, from two progressive folks I generally appreciate.

The first, from my good-hearted progressive friend Mark, who wrote an earnest little piece on his Patheos blog that defied the idea that we are broken at all. It was bright and cheerful and affirming. "Christianity has it wrong," it boldly announced. There's nothing wrong with you just as you are, he asserted, channeling our dear departed Mr. Rogers more than just a little bit. You are just fragile and distractable. It was intended to be provocative, to be challenging, and it was.

On the one hand, I see the point in not beating people down with endless talk of their sinny sinfulness. That's too often a tool for controlling others, for shutting them up and cowing them into submission. There must be hope and grace and promise in the Gospel, or it is not the Gospel.

On the other, well, it's just not real. "There's nothing wrong with any of us" doesn't resonate with anyone who's ever struggled with addiction in themselves or loved ones, or with anyone recovering from abuse. "We're all just fragile and distractable" doesn't get at the deep injustices we inflict on one another. And if there's nothing broken in us, why would we need to change anything, either personally or socially? The concept feels...well...not very progressive.

Then there was the second, from emergenty-prog-faither Peter Rollins. I've never read or listened to his stuff, but having encountered an absolutely lovely Jack Chick satire-tract he produced, I immersed myself in his thoughts for a while.

Here, I was again torn. I like Rollins aesthetics, and his Oirish accent stirs my ancestral heart. His is a deeply enjoyable mind. Sure, much of what he has to say feels intentionally paradoxical, the kind of Zen koan teachings that create within themselves irreconcilable tensions. To be orthodox, be a heretic. To know something, don't know what you know. To be centered, destroy your center. To lead, refuse to lead. That kind of thing seems to be his schtick, and it's a great way to stir thought, even if it does remind me a wee bit of the Sphinx from Mystery Men. More than a wee bit, actually.

But when he says, "embrace your brokenness," I honestly can't get there. Because brokenness sucks. It hurts. It wounds, and passes on wounds. It is not an abstraction, or a theological construct. It's human souls in pain.

Sure, we can take up our crosses, and simple pain-avoidance can't be the Christian path. Suffering often comes, socially and spiritually, when we challenge that which must be challenged. But just as I don't think we should tolerate social injustice, I also don't believe that a disintegrated, shattered existence is something we should just shrug and accept. It is what it is? That's not an organic path to healing and deeper, more gracious living.

Which, I am convinced, is kind of the point of both faith and Jesus.

Published on January 29, 2015 07:07

January 28, 2015

Counting the Beans

It was time for forms again, as my little congregation cranked through our required annual statistical reportage to the denomination. My clerk of session and I went back and forth with emails, checking numbers.

It was time for forms again, as my little congregation cranked through our required annual statistical reportage to the denomination. My clerk of session and I went back and forth with emails, checking numbers.One of the questions, though, was a bit fuddly. Had we used the services of a racial/ethnic pastor in the previous year? Well, no, I suppose not, given what that peculiar term means within my oldline denomination. It's a code word for "not white," because as we know, there are "whites" and there are "racial/ethnics." Here is a categorical system that assumes that Slavs are the same as Scots are the same as the French are the same as Norwegians, but that draws no distinction between a Korean and a Kikuyu.

"White" is the norm. Everyone else is "other." It's a peculiar thing. Well meaning, yes. But also more than a little awkward to the ear.

I personally know African American pastors and Asian American pastors and Latino pastors, sure. They'd be great. But they've got gigs on Sunday, responsibilities to their congregations that would make it a challenge to get out to a small quasi-rural community. Or they're friends now far away, and my wee kirk can't afford to fly people out for a Sunday.

But undoubtedly, hearing preaching from different cultural traditions can be both important and awesome.

We wrestled with this on Session, as we tried to figure out a way we could do this without being embarrassingly obvious about bean-counting. There's a list of pastors who engage in supply preaching, but it doesn't make a point of categorizing them by racial/ethnicness.

Not that I am suggesting this. Lord help me, I'm not suggesting this.

"We'd love to have you preach," we'd say, "but we're looking for a racial/ethnic," we'd say. "Are you a racial/ethnic?" That feels faintly insulting. Well, more than faintly.

What human being wants to be a slot-filler, just a particular kind of bean to be counted?

Published on January 28, 2015 05:48

January 22, 2015

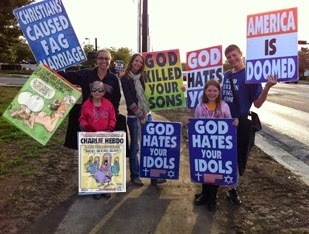

Charlie Hebdo Baptist Church

As it drifts out of our low-attention-span popular consciousness, I can finally say: I had a heck of a time processing the Charlie Hebdo massacre. I really did. It was monstrous, horrific, and an absolutely unjustifiable act. Violence cannot be allowed to silence speech, the protection of which is a vital part of both individual and religious liberty.

As it drifts out of our low-attention-span popular consciousness, I can finally say: I had a heck of a time processing the Charlie Hebdo massacre. I really did. It was monstrous, horrific, and an absolutely unjustifiable act. Violence cannot be allowed to silence speech, the protection of which is a vital part of both individual and religious liberty.But having seen the cartoons, and read some of the translated pieces of that magazine, I can honestly say that I didn't find them funny or insightful. Just sort of crude, by every definition of that word. It didn't have the bite or elegance of, say, The Onion, which is so often cultural satire at its very best. Or the Daily Show. Or Colbert's recently lamented report. Most of the time, Charlie Hebdo seems to lack...subtlety.

Americans? More subtle than the French? Quoi?! C'est absurde! Mais...c'est vrai.

That, and something else, something harder. Charlie Hebdo is often more than a little mean, focused on attacking a struggling immigrant minority, mocking and lambasting them for their poverty and ignorance. French Muslims have no power, and minimal representation, and control no significant part of the French economy. There's just no reason to attack those who are weaker than yourself, unless you're trying to score points by stoking popular ressentiment .

I could not say, #jesuischarlie, back when we were all supposed to be saying that, because I wasn't, any more than #jesuisanncoulter. I just would never express myself in that way. With the murdered being buried, that seemed awkward to bring up.

But how to come to terms with someone who uses their freedom in a way you would not? On the one hand, you want to defend their liberty. On the other, you cringe when they do. How can I frame this?

Here, once again, the good folks at Westboro Baptist Church came to my rescue. Westboro, as I have argued before, is America's most successful deep-cover troupe of Queer Christian Performance Artists. Their deeply biting satirical portrayal of a venomous theo-cultural bias has done more to advance the cause of gays and lesbians in America than any other organization. By holding a mirror up to what some Christians purport to believe, they show the moral untenability of that position. They have helped move America towards a more welcoming stance.

More importantly, they show the boundaries of free speech. What Westboro is saying is utterly reprehensible, bullying towards a minority and the vulnerable, and crudely cast, and yet they absolutely have the right to say it. It would be an unacceptable affront to human liberty if they were legally coerced into stopping their bizarre demonstrations. It would be tragic...yes, tragic...if they were physically harmed.

And there, I was given a conceptual handle to help me come to terms with secular Charlie Hebdo, which, though often willfully offensive, comes nowhere near the wildly horrible displays of the religious Westboro troupe.

If I can defend the rights of Westboro Baptist, it is far easier to see where Charlie fits into the scheme of human discourse.

Published on January 22, 2015 04:50

January 21, 2015

Abundance in Jamestown

It's a time of energy abundance!

It's a time of energy abundance!So crow the pitchmen for the oil and gas industry, eager to spin the current Saudi-overproduction-driven oil glut into something wondrous. A new age for America, part of an exciting time of expansion and growth, driven by ample new supplies of energy! Cheap gas! Big cars! It's 1969 again, baby! Abundance!

And on the one hand, taken as a snapshot of this moment in time, that is true. But it is a strange truth, because it masks a larger reality.

That reality is that we have arrived at the shores of a new world. It is a world soon to be devoid of fossil fuels. Oh, we have them, now. But within what I can reasonably expect to be my lifetime, our transportation system...and our agriculture...will have to be completely new.

This is doable. It is, God willing. It remains within our capacity to adapt, though every year we do not change deepens the challenge. But the global storehouse of fossil-fuel energy is just as finite as it ever was. The only change is that we're pumping it faster, at the same time we're flushing the last drops from the grudging rocks. Within the next fifty years, our entire energy economy will change. It has to, if we're to survive as a species.

Being American and all, I remember the history of our American experience, in all its mess and struggle and glory. And that stirred in me a metaphor, as so many things do. What this reminds me of is the experience of those first colonists.

Where we are right now as a country is Jamestown, and it's the Fall of 1609. We are those colonists.

We can't grow any more food, because the growing season has passed. What we have in the provisions that we've brought from England and what remains from our sparse harvest will have to get us through the long winter in a new land, until we are able to figure out a way to be self-sufficient.

What the sheiks and the pitchmen, the executives and the lobbyists want us to believe is that our finite storehouse is justification for a time of feasting.

"Look how much we've got in the storehouse," they smile, as they cut prices and tell us all to eat our fill. "Wow! So much! Time for a celebration! Yay us! Dig in!"

Which in Jamestown, in the Fall of 1609, would have been sort of true. But mostly not. That colony barely, barely survived a time of hunger and privation. Others, like the Roanoke colony, simply vanished, dying on the hostile shores of a new world.

What we are being told now is wildly unwise, the deluded foolishness of a profit-addled quartermaster.

There is no fossil fuel resupply ship. What we have has to last.

It has to, for the sake of our future.

Published on January 21, 2015 05:18

January 20, 2015

The Little Boy Who Didn't Go to Heaven

I don't read contemporary books about people who claim to have gone to heaven and come back, not generally. It's a popular genre, one filled with angels and deceased relatives and tunnels of light, and I understand the desire it fills. There are little boys, back from heaven. There are earnest doctors, recounting their mystic experiences. They meet Jesus, and angels, and your grandmother Tzeitel. These books sell very well.

I don't read contemporary books about people who claim to have gone to heaven and come back, not generally. It's a popular genre, one filled with angels and deceased relatives and tunnels of light, and I understand the desire it fills. There are little boys, back from heaven. There are earnest doctors, recounting their mystic experiences. They meet Jesus, and angels, and your grandmother Tzeitel. These books sell very well. Very, very well.

I don't read them. I just prefer not to know, because I don't think we know what that will be like, not in the depth of it. Even if we've dipped into that chasm, that vastness, I don't think we can know. So we have this first fleeting glimpse of eternity, as our selves filter it through the lens of the tiny flicker of life we've lived. So what? What does that mean, in terms of what is to come? Very little.

This last week, there was a well-publicized recanting, as a young boy who'd claimed to have that experience stepped away from what he'd originally claimed. He and his father survived a car crash, and had written a bestselling book together, entitled "The Boy Who Came Back from Heaven." It was the story of his experiences on the other side, and honestly, I haven't read it. This last week, the young man, who in a bit of Matrix-laziness was named "Malarkey," recanted his story in a formal statement conveyed by his mother.

On the one hand, it's easy to shake your head upon hearing that. It's a crass cashing in, just another person with some wildly marketable story that they pitch to a publisher, who sees the dollar signs. "Every time a cash register rings, an angel gets his wings," or so it goes in AmeriChrist, Inc. I'm as cynical as the next guy about such things. More so, frankly. Given that this was a kid, it made me sad.

But then I went past the headline, and read the statement. The tone and language of the recanting struck me, and struck me hard. It was not just, "I didn't have that experience, and I'm so sorry for misleading all of you." That is all that was needed. This was different. It was cast in the language of a very particular way of looking at the world, not so much a recanting as an ideological challenge. Read it for yourself:

Please forgive the brevity, but because of my limitations I have to keep this short.I did not die. I did not go to Heaven.

I said I went to heaven because I thought it would get me attention. When I made the claims that I did, I had never read the Bible. People have profited from lies, and continue to. They should read the Bible, which is enough. The Bible is the only source of truth. Anything written by man cannot be infallible.

It is only through repentance of your sins and a belief in Jesus as the Son of God, who died for your sins (even though he committed none of his own) so that you can be forgiven may you learn of Heaven outside of what is written in the Bible…not by reading a work of man. I want the whole world to know that the Bible is sufficient. Those who market these materials must be called to repent and hold the Bible as enough.It sounded strange in my ear. If this is a public apology for deceit, it's...odd. It is the kind of apology that says, "I lied, sure. But you were wrong for having believed me." It is written in the in-house language of Christian fundamentalism, and takes the peculiar tack of casting an untruth not in the bright light of whether it happened or not, but through the definition of "truth" that rises from that theological construct.

"When I made those claims, I had not read the Bible." Why is that relevant to whether a person had an experience or not? If I say, "I met Bilbo Baggins on the street yesterday, and we shared a pipe full of Longbottom Leaf," that claim is not false because it does not appear in The Hobbit. It is false because it did not happen, and I am making it up.

If you lie about something, the biblical apology would be, "I bore false witness." Plus a promise to not do it again, and an "I'm sorry." Just that. This is not a biblical apology. It's a fundamentalist one. It blames the publishers for taking him at his word, the very same publishers who immediately withdrew the book when he recanted.

His mother, herself a biblical literalist, fought the book from day one. The idea that her son could have had that experience in any form was anathema to her beliefs. Her son's recanting is in words and terms that are part of the litany of her tradition. She...now separated from her husband...is the primary caregiver for her son, a desperately difficult and challenging task for any mother. I read through her blog, through her deeply human struggles to raise her boy mingled with the kinds of stark, comfortingly binary ideological affirmations you get on fundamentalist blogs. It was heart-wrenching.

The whole thing just feels so...sad. And certainly, certainly, a reminder of how far we are from Heaven.

Published on January 20, 2015 04:57