David Williams's Blog, page 83

July 14, 2014

Our Vehicles, Our Selves

As we approached for the second to last meet of the season, the truck sat near the entrance of the swim club. It was hard to miss.

As we approached for the second to last meet of the season, the truck sat near the entrance of the swim club. It was hard to miss.It was a late-model short-bed crew-cab Ram pickup, and it had been significantly farkled up with accessories. It was painted in arrest-me red, and rode high on brightly-chromed wheels. The back window was festooned with stickers, all of which reflected a particular worldview.

To the right, a sticker announcing patronage at a chain of well-known commercial bars. Center-top was a skull and crossbones. Next to it, a faux-university sticker, announcing that the occupant was a graduate/alumnus of "FU." And on the left, an image of a young woman bending over, accompanied by what was meant to be a humorous pro-Chrysler message.

"Dodge the Father, Ram the Daughter," it said.

It struck me as peculiar.

Here, a human being has chosen to encase himself in a vehicle that sends a very clear social signal to those around him. It consistently messages a cohesive sense of that individual.

"I am a terrible person," he is saying.

What an unpleasant being that must be, I found myself thinking. And then I wondered, why would I think that? Is it judgmental to do so? Am I making assumptions about the nature of this person?

They are saying: "I feel strong when I present images of death. I enjoy intoxication. I hate you, and--more subtly--I mock education. I disrespect both parental love and the integrity of women.

Plus, I've taken a perfectly useful American working truck and spent thousands of dollars to sparkle it up like a Kardashian on the hunt for a new mate."

I found myself wondering further: What does this person think of themselves? What patterns of thought rest in their mind, that they want to present themselves this way?

Perhaps they see themselves as a rebel, and view all people and all institutions cynically. Perhaps they are uncritically self-indulgent, and get what they want by being aggressive towards others. Or maybe they find giving offense to others amusing, and take the resulting offense as a sign that other people are either weak-willed or judgmental. This may be a mask for woundedness, an insecurity born of pain. It could reflect a glazed-eye sociopathy. It could just be aping what passes for "I am a strong individual" in certain demographics.

There's just no way to know.

But it still strikes me as odd that any human being would want to present themselves as a terrible person.

Published on July 14, 2014 06:19

July 9, 2014

Unaccompanied Children

The crisis du jour, outside of the eternal mess of the Middle East, is the arrival of thousands upon thousands of children on the doorstep of the United States.

The crisis du jour, outside of the eternal mess of the Middle East, is the arrival of thousands upon thousands of children on the doorstep of the United States.With bleak economic conditions and violence in their streets, central American families are giving their children up, sending them off to be abandoned at the border of the United States.

Over fifty thousand children so far this year, which in and of itself is a mind boggling number. Our response, of course, is the usual. From some quarters, the usual ones, there have been calls for crackdowns. More border patrols! More security! Take the hard line! That appears to be the course we're on, but it's a problematic one.

These are, of course, children, which makes the hard line just a tiny bit more difficult. Sure, poverty and desperation are being manipulated by those who profit from the transporting of the children. Rumor and mis-communication also haven't helped. But those things are immaterial to the reality at hand. If we take a hard line as a nation, turning a cold hard shoulder to children who arrive helpless on our doorstep, then we'll have crossed a line as a nation from "being concerned about our borders" to "being evil." It's a tricky wicket for those who prefer fulminating absolutism as their response of choice.

What's hardest to grasp, though, is just why a parent would send a child off to a distant land alone.

It isn't an act of calculation. It's an act of desperation. If you have children, you know just how hard such an action would be. How desperate would you need to be to take that action? To pack your child up, and send them off to the mercy of an unknown shore?

How can we understand that level of desperation? How can we frame it, particularly those of us who draw from the long story of my faith?

My own denomination has made earnest statements about the issue, both heartfelt and practical, although a little lacking in theology or clear grounding in our faith. And that ground is there, without question. One image seems to pop most cleanly for me from the great sacred story of scripture.

A mother living under intolerable oppression casts her child away to an utterly uncertain future, abandoning them to fate, hoping against hope that they will survive. That child washes up at the feet of the powerful.

The scriptural analogy seems so obvious. Am I the only one who sees this?

Perhaps it's the scale of it that makes us miss it.

Fifty thousand Jocheveds, and the Nile running thick with baskets? What a strange and terrible age we must live in.

Published on July 09, 2014 13:53

July 8, 2014

The Dislocated

It's a funny thing, vacation.

It's a funny thing, vacation.We Americans are lousy at it, taking a day or two here and there. Or we do the "staycation," in which we curl up in an exhausted heap next to the piles of laundry that will provide our entertainment for the week.

For the last eleven days, I've been on vacation. By away, I mean, really, really away. Genuinely and truly "vacated." Not quite "Richard Dreyfuss at the end of Close Encounters" away, but close. Along with much of my extended family, I was on a small craft navigating in and around the Galapagos Islands.

For eleven days, I was in places that I'd never seen before. Every single day was a different place, a different environment, different faces, and different people. And as tends to happen on long and wandery trips, my mind adapts. I become used to everything changing, every single day. I become acclimatized to a great wash of newness, to encountering things that I've never before encountered.

It's probably just some peculiarity of my brain's wiring, as it makes space for new experiences and the unfamiliar. Whenever I take a long trip like this, home feels...different.

Oh, all the things are the same. The house is right where we left it. The things that were left undone in the pre-vacation life still need a-doing.

But when I've gotten used to things being different, my old patterns broken, and old familiar paths set aside, coming back into the old and familiar routines just doesn't quite feel the same. Familiar roads seem unfamiliar. The scent of my home seems different. The sprawl and stretch of the DC burbs just aren't quite as they were. I do not perceive them in quite the same way.

I reflected on this as I walked back from dropping off our car at a service station, as the flat tire we conveniently got the night before we left was being fixed. Here I was, still in this mind state where I didn't feel particularly connected to any place or any location. Even walking down my familiar street felt like I was encountering it for the first time.

"Dislocated," I thought to myself. That word hung in my mind. "I'm dislocated." Not in the bones-out-of-joint sense. But in the self-out-of-place sense.

In these few days before I readapt, I have a brief respite from a sense of belonging anywhere. Or of anywhere in particular belonging to me. After a few days, it'll go back to being as it was, and I'll move easily through the re-established patterns of the familiar.

I wondered, too, if perhaps it might help if we felt that way more often. Less like things were ours, or that places were ours.

So much of the mess we've made of things seems to come from being unable to see that.

Published on July 08, 2014 12:09

June 26, 2014

Riding the Storm

Last night, after wrapping up a meeting at my church, it was time to go home.

Last night, after wrapping up a meeting at my church, it was time to go home.But the wind was howling, the branches lashing about, and the flags on the house across the street snapped angry and horizontal. The rain came, fat and fierce, a summer storm in the South. It passed, and I went out to the bike to head home.

I could see, looking to the southwest in the early summer twilight, that there was more coming. In my path, the clouds were dark and towering and alive with lightning. I geared up, put on my overgloves, threw a leg over the Suzuki, and rode towards the storm.

It started hitting hard as I reached the sprawling mansions of Potomac. Rain in sheets, heavy and relentless. The water streamed across the road in torrents, impromptu rivers and streams, splashing up in fountains cast by my excellent off road tires, against my legs, cascading down my waterproof boots.

Ahead of me, the cars slowed to a crawl, struggling to see, their wipers flailing wildly. I have no wiper on my helmet visor. Just a small blade, embedded in the thumb of my left over glove. I wiped, but the rain was too intense. It spattered past my visor, cracked to prevent fogging, and the taste of fresh summer rain filled my mouth. It was warm and pleasant, the flavor of a water park on a hot day.

I followed the lights of the car ahead, half-seeing, my world a moist, incoherent blur.

Ahead was the highway, the Beltway. I pulled onto eight lanes of open road, as the cars around me struggled with the downpour, the darkness, and the blinding rain. And I got to the far left, and I opened it up. The Suzuki snarled forward on her eager little engine.

Because I have ridden for a lifetime, I knew the reason I could not see the road ahead: I was moving too slowly. I forced my way into the storm, and the wind of my progress drove the water from before my eyes.

The visor cleared, the beaded rain streaming away. I could see again.

I pulled onto the high occupancy toll lanes, empty but for myself.

The road home was clear, and I rode on into the rain, as the lightning danced all around like fireworks.

Published on June 26, 2014 06:20

June 25, 2014

Playing Like Jesus

After a long, long hiatus, this last week I've been taking my downtime and catching up on my gaming. There's not been much new out there for consoles since the market began the transition to the next gen. I'm not there yet, as I'm not motivated to drop a few hundred bucks on something I don't really need.

After a long, long hiatus, this last week I've been taking my downtime and catching up on my gaming. There's not been much new out there for consoles since the market began the transition to the next gen. I'm not there yet, as I'm not motivated to drop a few hundred bucks on something I don't really need.Instead, I'm going back, and playing games for the PS3 that I missed the first time out. In this case, I'm finally getting around to the Mass Effect Trilogy.

I'd heard great things about the game when it came out for Xbox 360. It was complex, and well acted, and well scripted, a wholly immersive space-opera that didn't make you check your mind at the door. But I had a PS3, so I was--for years--just out of luck. Now, though, I've remedied that.

Most interesting, to me at least, were the wildly different ways the story arc could play out. This went beyond the roleplaying game standards, in which your character--a highly customizable version of a protagonist named "Shepard"--could be equipped and developed in myriad ways.

It was that the moral choices within the game completely changed the story. There've been many games like this before, among the most notable being the gorgeous landmark fantasy game Fable, or the classic Star-Wars milieu Knights of the Old Republic. But Mass Effect feels like it takes that to a deeper level.

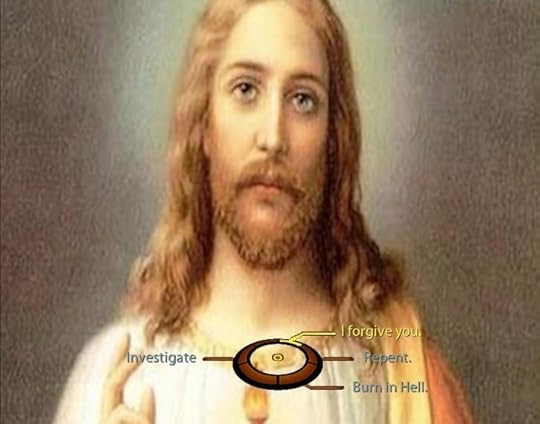

Mass Effect plays that out through a relatively simple system, a dialog wheel that comes up whenever you're in communication with others. There, in front of you, is the more gracious response, the neutral response, and what is typically an amusingly cruel smackdown.

If you play the Renegade side, hard and selfish, butchering enemies and bullying subordinates, and seeking advantage and wealth at every turn, it'll shape your story. Certain avenues will open up, and others will close.

If you consistently choose compassionately, trying to do as little harm as possible and showing mercy and a commitment to justice, the game plays out very, very differently. Doing the right thing does not always get you out of conflict. You can't always save every relationship, or insure that every friend and companion survives. But going Paragon does make a difference.

Those choices run deep, and have a cumulative effect. They create patterns of relationship that sustain through the whole of the first game, then are uploaded into the second, and then the third.

How do I play? When I play these games, I find that I don't want to "act out" being cruel. I just don't. I'm not really even curious to see what might happen if I did. My would I be curious? I know what that looks like, bitter and resentful and oppressive. Why would I want a story to play out that way, if it doesn't need to? I get enough of that in the news, and in the bitterness of virtual shout-fests.

It's not quite that easy in our day to day exchanges, those moments when we connect to others. We don't have a convenient moral dialogue wheel that hovers in the air in front of us to guide us, although perhaps there's an app in the works for Google Glass that might remedy that.

But then again, perhaps it really is that easy. We know our hungers and our angers and our resentments, and how those make us speak. We also know, in part, that best self that we're called to be, and what it looks like when we act in accordance with that grace.

It's a bigger and infinitely more complex choice wheel, and a wildly more intricate story. But as we shape our small corner of it, what we have to do is be intentional about making that right choice, every time it presents itself.

Published on June 25, 2014 05:49

June 24, 2014

My Circus, My Monkeys

I like this one, but my wife tells me it's a wee bit intense."Not my circus. Not my monkeys."

I like this one, but my wife tells me it's a wee bit intense."Not my circus. Not my monkeys."It's a meme that's been making the rounds lately, based on a Polish saying. The saying pungently evokes a moment and a mindstate.

There you are, and the street is filled with monkeys. Monkeys everywhere, getting into everything. They have presumably escaped from the circus, and it's chaos.

A storekeeper approaches you, in a panic, as the monkeys smash and leap and generally make a mess.

Perhaps this one.

Perhaps this one."Can you do something about these monkeys?"

To which you say, nonchalantly:

"Not My Circus, Not My Monkeys."

It's a way of saying: "Really, this isn't my problem. I have nothing to do with this. Didn't start it. Don't need to finish it. I've never met these monkeys before in my life, and I'm gol-danged if I'll stress about it."

More pointedly, the point of that saying is: don't let yourself get anxious about other people's mess. Which I'm fine with.

Zen Mojo Jojo. Hmmm.But what if it is our mess? What about those times when we can't look at something, and deny we're part of it? It's so easy to walk, to push off responsibility, to shake your head. This is particularly true when you do not agree with a position that the gathered group that you're part of has taken.

Zen Mojo Jojo. Hmmm.But what if it is our mess? What about those times when we can't look at something, and deny we're part of it? It's so easy to walk, to push off responsibility, to shake your head. This is particularly true when you do not agree with a position that the gathered group that you're part of has taken.Or when a position requires you to have awkward and difficult conversations.

"They did it," we say, grumpily, when anxious people ask us about why something was decided. "I had nothing to do with it. Those sure aren't my monkeys."

My denomination took several difficult steps in the last week, ones that will require the aforementioned challenging conversations. Same sex marriage? Israel/Palestine? I mean golly, what could possibly go wrong during a conversation on those subjects?

Ack.

It'd be easier--more comfortable--to push those conversations off. "Eh, why talk about it? We've got other stuff to do. Not my circus" It would be equally easy to have those conversations from a position of remove. "Well, you know, that was the perspective of the GA. But I wasn't there, and those folks aren't me. Not my monkeys."

But as I followed the GA this year, the words kept echoing in my head:

"My Circus. My Monkeys."

And no, that's not any particular comment on the character and/or hirsuteness of the commissioners.

It's about belonging, even in difference. It's about taking responsibility to speak grace into difficult, complex realities.

If we're serious about being a denomination in which relationships--particularly challenging relationships--matter, then we need to be willing to lean into that relationship a little more fully.

Published on June 24, 2014 05:32

June 23, 2014

Having a Conversation about Israel

Midway through last week, I sat at the kitchen table with my boys.

Midway through last week, I sat at the kitchen table with my boys. That very day, my denomination was in the throes of some really tough decision-making about disengaging from businesses profiting from the peculiar military/correctional mess in Gaza and the West Bank. I'd pitched in my two cents here on the blog, and I felt the need to sound my perspective off my boys. It was just the three of us, as my wife had gone with my mother-in-law to sit shiva that evening with the family of the rabbi of our synagogue, who'd lost his father.

So that night it was Presbyterian pastor dad at table, having a dinner meal with his Jewish sons.

There are plenty of calls to have conversations to rebuild relationships between the Jewish community following the General Assembly, and I'm obviously in an unusual position to have such a conversation. Judaism isn't just an abstract community for me, folks I know from meetings and gatherings. It's not just that I "have Jewish friends."

It's the woman that I love. It's the flesh and the blood of our children.

We chose, early on, not to do the half-and-half thing. They would be raised Jewish. Period. And so, having made that nontrivial decision, I've had a nontrivial hand in their Jewish upbringing. I found the mohel and made the arrangements for their brises. I schlepped them for years to synagogue for Hebrew School, through the worst traffic in the United States. I stood with them on the bema, and watched proudly as they were mitzvahed.

So I started in, asking them for their perspective.

Here's what we might be doing and why, I told them, laying it out as objectively as I could. Here are the three American corporations we would no longer be investing church resources in, here are the specific products and services they are providing, and here is why we feel we can't be part of that.

What do you think? Are we being unfair? Is my church picking on Israel, or being anti-Semitic?

At sixteen and thirteen, neither of my sons are particularly shy about telling their father when they think he's being an idiot. Believe me. Not. Shy. At. All. God help me.

My thirteen year old piped up first. "Not even close," he said. "Not everything that Israel does is right. Why would you have to agree with everything they do? Why would I?" And then, because he is every once in a while prone to *cough* vigorously expressing his opinion, he went into a schpiel about how weird he thought it was that a Jewish state should have a large ethnic community within its borders that are unwillingly walled in.

"You know what that is," he opined after describing the West Bank and Gaza, gesticulating and raising his voice. "You know what you call that? You call that a ghetto. It's a freakin' ghetto. It's like Israel is turning into the freakin' Nazis. If anyone should know better than that, it's we Jews. Why is Israel acting like a bunch of freakin' Nazis?"

My older son, more inward, more measured, was a little more circumspect. "That's not really a fair description. What Israel is doing is not good, sure. But it's not like the Holocaust. They aren't being systematically slaughtered. Israel's not like the Nazis. It's just not the same." He thought for a moment.

"It's more like what America did to the Native Americans. It's like they've been kicked off their land and forced to live on reservations. Israel isn't getting all Nazi with the Palestinians. They're getting American on them."

There was more back and forth, with some of the heat and debate that always comes when my sons get into something, but after surprisingly little bickering, both agreed:

Israel is just being like America in one of her less proud moments, and it does not look good, and it was not anti-Israel or anti-Jewish to both point that out and to choose not to validate it.

And then they were off, disappearing into their rooms and their screens.

It was an interesting talk.

Published on June 23, 2014 08:50

June 20, 2014

The Hard Middle Way

Being a peacemaker ain't easy.

Being a peacemaker ain't easy.There's a temptation, in it, to try to be all things to all people. You want to bring peace, to keep things graceful, and in doing so, you try to connect with everyone as if your position was their own.

"I believe exactly as you do," you say, to folks who are in conflict with one another. "You and I are the same!" You cozy up to one, and you cozy up to the other, and eventually, they realize your interest is simply in your own comfort.

That's the point of a favorite ancient story, told by an enslaved storyteller. It's the story of the bat. "The Bat," Aesop called it. There was once a war between the animals and the birds, Aesop said.

The bat, seeking its own good, flitted first to one side, then to another. On each, the bat insisted it was whatever they were. Look at my wings, it said to the birds. I'm one of you! I'm on your side!

Look at my legs and my fur, it said to the animals. I'm one of you! I'm on your side!

They got wise, and saw the duplicity, and cast it out into the night.

Standing in the balance, though, requires that we be in the harder place in a relationship, that liminal place between competing claims. It's both/and. It's fire and chaos and conflict, the shimmering, living complexity of relationship between persons. It's difficult footing, and lacks the shiny clarity of all-or-nothing polarity.

We don't take up the sword of either side. We refuse, in fact, to take up the sword at all. We are firm, but we don't seek the destruction of any.

That is the place where justice dwells.

To those who seek the middle way, a word of encouragement, in the hardness of that place. Know that there, you're not Aesop's Bat.

You're Batman.

And Batman is awesome.

Published on June 20, 2014 11:32

June 19, 2014

Zionism Unsettled and Conflict in Small Spaces

It's such a little place.

It's such a little place.That's an American bias, but so it goes. It's a little sliver on the map, a slender fleck nestled on the edge of the Mediterranean Sea. Just a tick over 10,000 square miles, which sounds like a whole bunch, until you realize it's just a third of the size of my ancestral Scotland, and a quarter of the land mass of my home state of Virginia.

It seems odd that such a small patch of earth would have such an outsized influence on the global conversation and my own faith, and yet it does. This is the land the Creator of the Entire Universe gave to his Chosen People? This is where my entire sacred story arose? Point Zero Zero One Eighth Of One Percent of the dry land on one tiny little planet in this functionally infinite multiverse?

Lord, you baffle me sometimes.

It's so small. So fragile and precious. Like that hoped-for child, born too soon, their frail body filled up with tubes, struggling for breath.

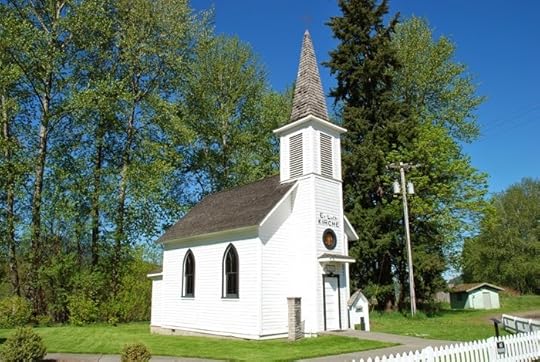

I was thinking about small things, yesterday, as I read through another of the books for my doctoral research. My focus: small churches, those intimate communities in which ties of blood and relationship run deep. I am not studying small communities through the lenses of the American Big Church, but rather looking at them for what they are: Little tribes, in little places. Those communities can be beautiful, joyous, life-giving and intimate. They function on a deeply human scale, unlike the giant shiny Jesus Malls of AmeriChrist, Inc.

In that, little churches have much to offer us.

But when a small community fights, it burns bright and hot with the focus that comes with limited space and longstanding relation.

In a tribe, you can't just take the American approach to conflict, which is to polarize and then storm off to some other place where everyone is exactly like you.

In a tribe, there is no other place to go. You are defined by that network of relationships. They--and the limited space in which you are both rooted--are you. Conflict is inescapable in close quarters, and managing conflict effectively there is both hard and necessary.

As I read through the carefully researched principles of effectively moving through conflict in intimate community, it played out across my mind and resonated with my recent re-reading of a controversial publication of a subgroup of a committee of my denomination.

Zionism Unsettled, it's called. There's been much discussion of the place of such a publication in the life of the Presbyterian Church (USA). Should we endorse it? Should we disavow it? Should we refuse to even distribute it?

This document comes as we Presbyterians are trying to find a way to make ourselves servants of God's peace in the thickets of a multigenerational level-five conflict in the Holy Land. It's a mess, tight and hot as a family-church argument.

Zionism Unsettled speaks from one partner in that conflict. It arises from the slightly misnamed Israel/Palestine Mission Network, which was established by the church for the express purpose of creating ties to the Palestinian Christian community. That, it has clearly done. As such, it articulates that position, and does so in a way that legitimately articulates the heat of the argument. It's a more measured document than others I've seen, but it is explicit about its purpose: to express the pain of the Palestinian people. It does that, and like all anger, it's worth hearing.

But against the principles of conflict resolution as they play out in tight-knit communities, it cannot be the basis for Presbyterian engagement with that conflict, not if we are true to our calling to serve peace. Why?

Does it accept the faith of the Other? It is hard to see that it does. "Simply put, Zionism is the problem," it says. Meaning that the hope for Zion--a central part of Jewish identity--is stated as the issue. The issue is them, it says. By defining the Other's best hope in terms that radicalize and demonize, it cannot be a foundation for deescalation.

Does it define the conflict neutrally and mutually? It does not, because it speaks--explicitly and intentionally--from one perspective. That is a legitimate perspective, and one that needs to be heard. But it is not enough.

Does it clarify the point of conflict? Sort of, in that it articulates the struggle to find a mutual place in the land, and expresses some of the tensions that conflict creates.

Does it reflect critically on self? No. Reading through Zionism Unsettled, there is no meaningful treatment of Palestinian violence against Israelis. I will not, not for a moment, apologize for Israeli aggression or oppression. It's a real thing, and a part of this conflict. But there's no meaningful treatment of the mutual cycle of violence. Terrorism, we hear at one point, was taught to the world by Israel. No mention of Palestinian hijackings, or killings, or suicide bombings. Nothing.

"O Lord, They have our blood on their hands" may be a true statement, but it is not the foundation for healing. "Oh my God, I have your blood on my hands" is where that begins.

Does it establish a joint purpose? It does not. It is primarily a deconstruction of the Other, not a document that seeks vigorously and intentionally to build common ground. That is implicit in its title. Deconstruction has its place, but it ain't what you do when you want to build something. Sorry, my pomo folk. That only goes so far.

Does it celebrate and hold up places of agreement? Here and there, it tries. There are whispers of that hope throughout the document. It is worth honoring that attempt, so hard to do from a place of such deep pain.

So how to relate to such a document? I think it is important to hear it, and to stand in relationship to it. To that end, it is important that we not tell those experiencing pain and oppression that they have to shut up, and that we will not share their voice. It's good that we're no longer seriously considering removing that perspective from our denominational web presence.

But it is equally important to be clear: if we are to serve peace in the heat of that intimate, tribal space, we have to stand not with one party or another. If Zionism Unsettled was presented as the official position of our denomination, we'd be doing just that.

We need to be clear that it is not.

It's a hard place to inhabit, those close quarters of relationship. It is easier to go with the bright clarity of binary conflict, to let the certainty of pain and fear become your narrative.

But if we--friend to both, torn by our love for both--are going to step into the heat of a conflict in a small community, we need to do the harder thing.

Whether the fragile breath of peace survives in those little places is the business of our Maker.

Published on June 19, 2014 07:12

June 17, 2014

The Church Politic

For the last few days, mixed in with my readings for my doctoral project, I've watched the goings on of my denominational Mother of All Meetings from afar. I've tracked the online chatter. I've followed the #hashtag.

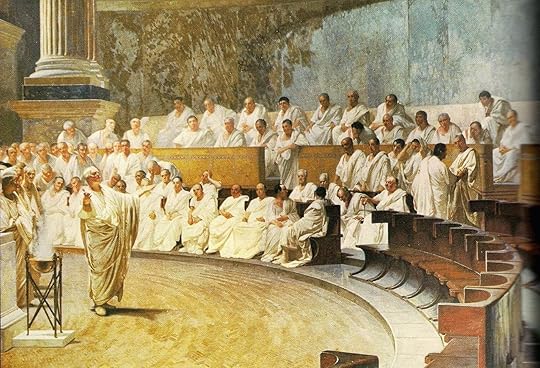

For the last few days, mixed in with my readings for my doctoral project, I've watched the goings on of my denominational Mother of All Meetings from afar. I've tracked the online chatter. I've followed the #hashtag.What has struck me, harder this year than before, is just how very much our way of being together is a political system.

Like, say, the websites set up by folks who were running for the esteemed position of Moderator of the General Assembly. Oh, sure, there's not a party affiliation--not formally, not yet, thank the Maker--but these are exactly the same sort of things you see when your state senator is out there shaking the web for votes.

Or the wrangling on the floor and behind the scenes over procedural issues, the sort of back room wheeling and dealing that happens whenever human beings get together in huge groups to figure things out. There's complicated commentary on rules, and wondering about secret agendas, and all of the [stuff] that rises from the organic life of parliaments and committees of the House of Representatives.

This all serves to remind me: in the way we structure our life together, we Presbyterians don't look anything like the sleekly focused corporate hierarchies of market-based megachurch Christianity.

Our way of being together? It's not product. It's the way of the polis. It's political, in the same way that a constitutional republic is political. It's just how human beings in large groups function, when there's no King or Emperor or CEO to call every last shot.

When I teach new members classes, or confirmation classes, I've tended to highlight that as a strength. The foundation of our Presbyterian constitution arose from the same heady era as the Constitution of the United States, and that--for a very long time--was a great strength of our...um..."brand."

Now, though, I do find myself wondering if that's one of the reasons we struggle to connect with culture as a fellowship.

Here we have a culture that is worn out and disillusioned by the mess of political discourse.

It's always been boisterous, always, but that tendency towards rancorous hubbub has been amplified to bleeding-ear levels by 24 hour news cycles and the roaring partisanship of our online echo chambers.

That way of life, loud and divisive and messy, can be exhausting. It can also be rewarding, in the complex way of human relationships, but demanding of our energy and attention. It requires sacrifice. No one gets exactly what they want, because in a relationship, that's an expectation that kills.

Here we have a culture, in which we live out our mess publicly and together, that has come to expect faith to look like a product. We want what we want, with a couple of clicks and two day shipping. Product does not challenge us. It gives us what we want, or we return it.

And that's a bit challenging, when it comes time to tell people about this way of being we've found. Come join our fellowship, we say.

It looks just like politics!

Sigh.

Published on June 17, 2014 11:07