Shevlin Sebastian's Blog, page 26

June 16, 2020

Freedom for all

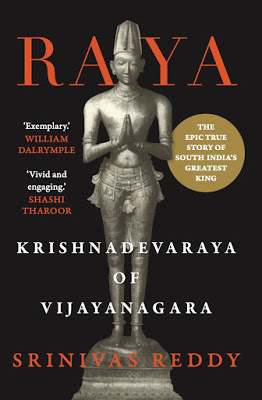

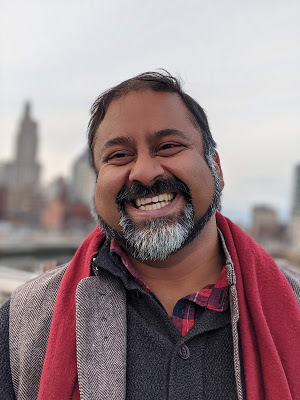

Academic and musician Srinivas Reddy has written a book about Krishnadevaraya of Vijayanagara, one of the greatest kings of South India who believed in tolerance

Pics: Krishnadevaraya of Vijayanagara; the book cover; author Srinivas Reddy

By Shevlin Sebastian

Just when Krishnadevaraya was about to ascend to the throne in Vijayanagara in 1509, his late father’s Prime Minister Timmarasu took the young man aside, and instead of imparting some advice, he slapped him. Krishnadevaraya was shocked. Timmarasu said, “It is important for you, as a young king, to remember the hardships of life and the pain of being punished.” Timmarasu also said that punishments should be meted out judiciously because, after this day, Timmarasu could not discipline the new king, but could only obey his command, whatever it may be.

The US-based academic Srinivas Reddy has recounted this anecdote in his engaging book, ‘RAYA — Krishnadevaraya of Vijayanagara’. The hardcover book has been published by Juggernaut and is priced at Rs 599.

When Srinivas was translating Krishnadevaraya’s poem, ‘Amuktamalyada’, he realised that not only was Raya a great king but a celebrated poet as well. A desire arose in him to write about the king. “I aimed to write a scholarly work but I also wanted to make it accessible for everybody,” says Srinivas by phone.

He did extensive research of the period in which Raya ruled (1509-29). In the bibliography section, the names of 60 authors have been mentioned.

One of Raya’s greatest achievements was that he was always victorious in battle. He defeated the Gajapatis of Orissa, the Sultans of Bijapur, and many other rival kings. Thereafter, he ruled over a large kingdom. And providing shrewd, tactical and wise advice was Timmarusu.

Raya’s second achievement was to create an aura of a majestic king. “The people looked up to him,” says Srinivas. “Raya was also a skillful administrator. He built tanks, and temples, and provided several benefits to the people. He was a people’s king.” To get a better idea of their needs, Raya would disguise himself and walk through the streets.

And at its peak, Vijayanagara was a dazzling place. As Portuguese traveller, Duarte Barbosa wrote, ‘There is an endless number of merchants, wealthy men and natives of the city to whom the king allows such freedom that every man may come and go and live according to his own creed...great equity and justice are observed by all, not only by the rulers but by the people one to another’.

Thanks to the Portuguese horse trader Domingo Paes, who came to Vijayanagara, and whose writings appear in a book called Chronica dos reis de Bisnaga (‘Chronicle of the Vijayanagara kings’), Srinivas has been able to describe the morning schedule of Raya.

‘The king would wake before sunrise and massage his whole body with amber-coloured sesame oil before gulping down half a litre of the same. Wearing but a tiny loincloth he would exercise his arms by lifting great earthenware weights and practising with a sword until all the oil he had just consumed was sweated out of his body. Next he would spar with one of his wrestlers before mounting his horse and galloping over the plains until dawn. And then after being bathed by a trusted brahman, he would go to his private temple to offer his daily prayers. Finally, he would make his way to the meeting hall where he would discuss matters of state with trusted officers and city governors’.

Asked about the lessons Indian politicians can gain from Raya’s life, Srinivas says, “You have to lead by example. When leaders behave in a certain way, people behave in the same way. In Sanskrit, there is a saying, ‘Yatha Raja, Tatha Praja’ (As the king, so the people).”

But what is distinctive about today's times is that populist leaders like US President Donald Trump and Russian President Vladimir Putin are predominant. “Raya’s life as a king shows that there has to be a philosophy behind any political action,” says Srinivas. “And his philosophy was simple: you do well for the people, the State does well. Or you do well for the State, the people will do well. There was a symbiotic relationship between government and the citizenry.”

Srinivas admits that the thinker-politician is rare today. “The only names which come to mind are [former US President] Barack Obama, and [Thiruvananthapuram MP] Shashi Tharoor,” he says. “There should be a dialogue between theory and action.”

As to whether there was communal polarisation during Raya’s time because Muslim kings were also ruling, Srinivas says, “Polarisation has a modern connotation. During the 1500s, there was a lot of cultural interaction happening in the Vijayanagara kingdom. The Deccan Sultans were bringing interesting people from Persia, then the Portuguese came in, and Islam also thrived. There was a heated rivalry between Vijayanagara and the Sultans of Bijapur, but they were always interacting with each other, and had marriage alliances.”

The striking aspect about Raya’s rule was the high level of tolerance. You could do what you wanted in your personal, religious and cultural life. “But everybody was part of a community,” says Srinivas. “If you study the history of India, it was a place of tolerance. However, within communities, there was discrimination, like the caste system. The reason communalism thrives now is because we are still stuck in the colonial mindset. The leaders are lost in rhetoric and uselessness.”

The book has received high praise. Historian William Dalrymple says, “This is an exemplary biography. Minutely researched, full of new material, this finely written study is full of good stories, revealing anecdotes and cleverly analysed myths.” Says scholar Rajmohan Gandhi, “As a man, Raya has remained elusive until this riveting study.” Adds historian Philip B Wagoner: “This book is a must-read for anyone interested in Indian history.”

(Published in Kochi Post)

Published on June 16, 2020 21:00

June 12, 2020

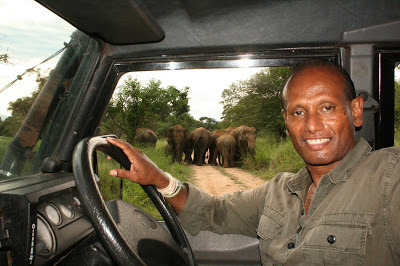

Growing citrus fruits can be a deterrent to elephants

Ravi Corea, the Founder-President of the Sri Lanka Wildlife Conservation Society, suggests solutions to the elephant problem in Kerala, and IndiaBy Shevlin Sebastian On May 27, Ravi Corea saw an email alert pop up on his laptop at his home in New Jersey. It was about a pregnant elephant in Kerala, which died when it ate a pineapple that had an embedded explosive inside it. Ravi felt sad as he pressed his fingers against the forehead. “To cause injury in this manner is disturbing,” he says. “Many of these baits are made for other animals like wild boars because they raid crops. Whatever be the reason, it is inhumane to injure or kill an animal by blowing off its jaws.” Unfortunately, these methods do not kill the animal outright. “They have a prolonged and agonising death,” says Ravi, the Founder-President of the Sri Lanka Wildlife Conservation Society (SLWCS), which is based in Wasgamuwa (233 kms from Colombo).One reason for the human-elephant conflict is because man is moving aggressively into forests and animal habitats. As a result, the space for elephants is shrinking. “And when land is allocated for development, there is a complete disregard about the impact on elephants and wildlife.” In Sri Lanka, the Mattala Rajapaksa International Airport has come up in Hambantota (259 km from Colombo). “This airport has displaced over one hundred elephants,” says Ravi. “It is very sad.” Apart from this, new stadiums and highway networks have also displaced elephants.Ravi has come up with some solutions. Following intensive research, he said elephants should not be accommodated only within national parks. “In the 1980s and 90s, one of the most favoured methods was to fence elephants into protected areas,” he says. “But this method is flawed. The elephant is an animal that travels vast distances. So, by enclosing them in a national park, we are preventing them from accessing habitats which they have been doing for hundreds of years. The other point is how do you know whether you have all the elephants inside the park when you place fences on the perimeter.” So Ravi came up with the concept to fence the villagers, and their fields, instead of the animals. In Sri Lanka, they use solar-powered electric fences which gives a charge of 8000-12,000 volts. “It is a low amperage that travels in pulses,” he says. “It does not kill the elephant. Instead, it gives a massive shock. Hence, these fences are not lethal, but act as a deterrent. Usually, if you touch a regular live current you are pulled towards it.” For this innovation, the SLWCS won the Equator Prize from the United Nations Development Programme in 2008. The Singapore-based animal lover Kiran Sujanani went to SLWCS as a volunteer. She and other helpers were assigned different duties each day. “One of them was to check the electric fencing,” she says. “Each day we covered around five kilometres to check if posts had fallen off or whether the wires were intact. Each post was marked with a unique GPS ID. We would return back to base and report any problem. The workers would then go and repair the damage.”

Meanwhile, Ravi stumbled on to another solution. In the early 2000s, he noticed that whenever elephants entered a village, they would eat mango, coconuts, bananas, pumpkins, sugarcane, corn, and watermelons, but they never touched citrus or damaged the tree. However, they would topple other trees with their trunks even if they did not eat the fruits. To see whether this antipathy to oranges exists, the society conducted a trial with captive elephants. “We discovered that citrus fruits came very low in their preferences,” says Ravi. “One reason is the limonene compound, which gives the taste and tangy smell. I would like to clarify the oranges we use are green, not yellow or orange. So, if you grow this type, the elephants will stay away.” Essentially, the orange trees mask the smell of crops stored in homes, and this prevents elephants from raiding farms.In fact, in April, the farmers had a bumper orange crop. “It has provided a very good supplementary income,” says Ravi. “The farmers told me they had no problems with elephants ever since they planted these trees.” Whether these methods can work in Kerala, Ravi says there is no one solution for all places. The best thing to do is to map Kerala. “Find out where the elephants and the people are,” says Ravi. “Identify the hotspots of conflict between man and elephants and the underlying causes.”Thereafter, you need to try different solutions. “For example, if farmers are living next to a fence, they could grow citrus trees,” says Ravi. “Or they can keep livestock.” (Published in Kochi Post)

Published on June 12, 2020 21:03

June 9, 2020

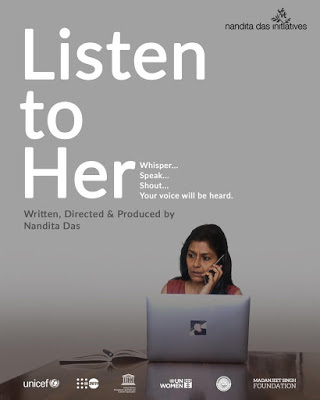

Time to stop the over-work and the domestic violence, says actor Nandita Das

By Shevlin Sebastian

In her seven-minute film, ‘Listen To Her’, actor Nandita Das sits in front of her laptop at the dining table of a Mumbai apartment. There are large, airy windows, elegant furniture, a painting on the wall, and a plant growing in a pot at the corner of the living room. As she is having a Zoom conversation with her office colleagues, her son, played by actual son Vihaan, says, “Mama, do you know an octopus has three hearts, and even if you cut off its head, it can still live for one more hour.”

Nandita replies with “God, that’s so cool!” Then she returns to her Zoom conversation. But just then a sound comes from the bedroom, where her husband is watching a film in loud volume on the laptop. So, she grimaces, takes earphones from a small box placed on a cabinet and gives it to him. Hesays, “Sorry, was it too loud?”

She says yes, and comes back. The pressure cooker goes off in the kitchen, so she goes to switch it off. Just then a call comes on her mobile. A woman calls and asks whether it is an NGO. Nandita says no, and cuts the call. The woman calls again for help and in the background, a man has come home. It seems the woman is in the washroom and he bangs on the door and tells her to come out. In her panic, she forgets to switch off the mobile phone. When she opens the door, the man slaps her, she cries out and there is a child wailing in the background.

As she listens to all this, Nandita has a look of anguish about her. She calls the police but they sound bored and indifferent. The story rolls on...

Asked about the trigger for the film, Nandita says she saw a news item which stated that the National Commission for Women had recorded more than a two-fold increase in the number of cases of gender-based violence during the lockdown. She realised it was ironic that the tag for the coronavirus pandemic is ‘Stay home, stay safe’. “I call this the ‘Shadow Pandemic’,” she says. Later, Nandita came across many cases of domestic violence, during the pandemic, across all classes.

Adds Nishtha Satyam, Deputy Representative, UN Women India: “Many women have dreaded the four walls of the home, a private chamber that reminds them of physical, emotional and psychological abuse. This film speaks about ending the violence against women and girls.”

Before making the film, which has been supported by UNESCO, UNFPA (United Nations Population Fund), UNICEF, UN Women and the South Asia Foundation (Madanjeet Singh Foundation), Nandita had taken part in an online campaign to break the silence around it.

There are two threads in the film: one is of overworked women and the second is about domestic violence which takes place in many households.

As to whether women are overburdened, Nandita says, “In our country, overburdening of work is not seen as an abuse. But yes, women get exhausted because they work relentlessly for their family and also do a job. No one talks about their fatigue. That’s because we live in a patriarchal society.”

She feels that for things to change, women have to speak up. “But in India, 53% of the women believe their husbands are justified in beating them,” says Nandita. “While for the other 47%, it might move the needle. I hope by watching the film, a few women will get up the courage to talk about their hellish experiences. Society cannot thrive if half the population lives in fear of being abused.”

Eric Falt, Director and Representative, UNESCO New Delhi. agrees. “There has to be a redefinition of masculinity, where men share responsibilities with women in dignity, respect and non-violence,” he says.

Expectedly, the film has struck a chord. On YouTube viewer Dr. Moushumi Gangopadhyay says, “I know how it feels like to be there. Domestic violence can cause havoc in a person’s life.”

Yolanda from Surinam says, “I literally had tears in my eyes. It's not easy standing up for yourself if you have seen your grandmother and mother in that situation your whole life. There are a lot of women who are scared like hell. I've seen it. No matter how hard you try to help them, they are too scared to take it.”

Adds Nirupama Kishore, “Made the man I was watching it with, so uncomfortable! They know what they are guilty of!”

(Published in Kochi Post)

Published on June 09, 2020 04:53

June 7, 2020

A sapling grows along with your baby

For the past ten years, the Matria Hospital in Kozhikode presents a mango plant to the parents of newborn babies

By Shevlin Sebastian

Zeina Tanash stood next to the green mango, still hanging on a low branch, cupped it in her small right hand and gave a sweet smile, as her mother Jasmine Faizal clicked the photo.

For the Abdullah Mallambalam family, which includes businessman Faizal, the mango tree is close to their hearts.

Zeina was born at the Matria Hospital at Kozhikode on July 5, 2014. A day later, two doctors in their white coats, along with nurses, and the administrator entered Jasmine’s room. They presented her with a cake, and a laminated birth story It mentioned the name of the doctor, the nurses, the time of the birth and the name of the person who received the baby for the first time. In this case, it was Jasmine’s father, Ashraf Anchillath. And lastly, they gave a mango sapling.

They requested the Abdullas to plant the tree so it would grow in the same way Zeina would grow. Since they lived in a two-acre plot at Kanhangad, it was easy for them to do so. “We would water the sapling once a week, and use organic manure,” says Jasmine. As Zeina grew older, Jasmine told her about the tree. Thereafter, Zeina would tell her friends, “This is my tree.”

For the past ten years, Matria Hospital has been given a sapling following every birth. “Till now, we have given away 15,000 saplings,” says Dr Mohamed Kasim, Executive Director, and the son of the founder Dr VK Kutty, who died on December 3 last year. Several notables have received the saplings. They include the singers Sayonara and Mridula Varier, director Anjali Menon, and actors Asif Ali and Hareesh Kanaran.

On January 1, 2018, Hareesh’s wife Sandhya gave birth to a daughter, Dwani. Hareesh had been allowed into the labour room and watched the birth. He was much impressed by the staff and facilities. “It was a pleasant surprise when they presented us with a mango sapling,” he says. Within two days, after he reached his home, in an area of 27 cents, in Perumanna, Hareesh planted the sapling. “It will take another two years for it to reach its full maturity,” says Hareesh. “But last year, there was a single mango.”

Playback singer Mridula Varier was not surprised about the sapling. When she would attend the check-ups, on a card which is given to patients, it was mentioned. She gave birth to a baby girl, Maithreyi on June 11, 2015. The sapling has been planted in their home at Koyilandy (25 kms from Kozhikode).

“Since it is a mango plant, it grows by itself,” she says. “Still, workers would check on it that it was not afflicted by any disease.” It has reached about five feet in height. But so far, no mangoes have sprouted. Mridula had told her daughter about the tree, so occasionally, she steps out of the house and looks at it. “Maithreyi has asked me when the mangoes will come,” says Mridula, with a smile.

Asked why only mango saplings, Dr Kasim says, “Because it provides a fruit within three to four years.” The hospital buys the saplings from gardens nearby.

This idea as well as the hospital was the brainchild of Dr Kutty, a general physician. He ran a hospital in Tirur. One day, realisation dawned on him that there was no hospital in north Kerala which was dedicated to maternity care. “In a general hospital, when a woman goes for delivery, she might come across sick people or an accident victim lying on a stretcher,” says Dr Kasim. “That is a depressing experience. My father felt births should take place in a pleasant environment.”

Research also revealed that the maximum number of births every day in Kerala took place in the Kozhikode area. So, he decided to set up the Matria Hospital in 2010. One evening, when he was chatting with his mother Kadeeja Nediyil about this, she told him that if during the construction, trees are cut, Dr Kutty should plant the equivalent number after the hospital came up. But following the construction, Dr Kutty discovered there was very little space for trees to grow. So he compensated by growing a lot of green flowering plants on the campus. As for trees, he provided for its absence by gifting saplings.

“A good environment is a must for good health,” said Dr Kasim. “The idea is to encourage families to nurture trees in the same way they nurture their children. Planting saplings is not enough. People have to take care of it until it becomes a tree.”

Sugesh Devu, consultant, gynaecology, says that when families return home they feel they have two babies. “Parents feel happy about a plant growing alongside their babies,” she says.

Jasmine says this is a delightful way to create awareness about planting trees. “This will also help create a little greenery for the future,” she says.

(Published in Kochi Post)

Published on June 07, 2020 21:12

June 5, 2020

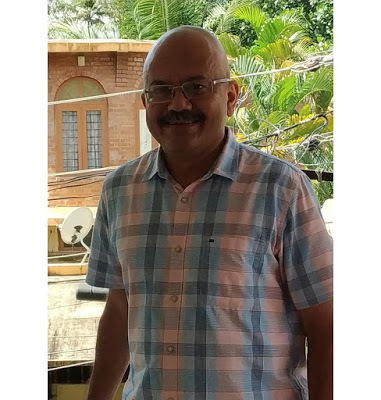

A bald move

By Shevlin Sebastian

On the morning of May 26, an irresistible urge arose in me: I must shave my head. I was sitting at my laptop. I give a lot of importance to these surges from the unconscious. I stood up and walked up and down the room. But the urge remained insistent. I did not know whether to follow up on it.

This has been my desire for the past few years. And the reasons were simple: my hairline was receding. Every day when I combed my hair, a few strands would be stuck in the teeth. There was an increasing bald patch at the top of my head. And at the sides, above my ears, the grey had begun its onslaught. So, it was no fun looking at the mirror in the mornings.

In September, last year, I did an interview with Jyothir Ghosh, a former news editor of the Malayalam newspaper Mathrubhumi because he had written a book about Sabarimala. When I met him, I noticed he had a smooth bald head. “I just shaved off my hair one morning,” he said. “I feel free now.”

I remembered the conversation. I called him up and spoke about my urge. He encouraged me to go ahead.

As for the daily shaving, he told me to first wash my head with water. And then use a twin-blade razor. “Within a week, you will do it easily,” he said. “I close my eyes when I do it. It is like a meditation for me.”

Baldness had been on my mind for the past few days, too. On Netflix, I watched the documentary, ‘The Last Dance’. It focused on the Chicago Bulls as they made their sixth successful championship run for the National Basketball Association title in 1997-98. Legend Michael Jordan featured prominently in it.

As I stared at Michael, I could not help but look admiringly at his sleek bald head. It made him look good. Then a much younger Bahrain-based friend who had gone bald gave me an irresistible stimulus: “Man, the chicks are coming at me.”

As these thoughts swirled in my mind, I typed a question on Google: what is the ideal head to go bald? ‘Round’ came the answer. I went to the mirror, placed my hands on the edge of my forehead, and formed a sloping roof, so I could not see my hair. It seemed to me that my head was round.

So I took the plunge.

I went to an upmarket salon. But when I opened the glass door, it was dark. But the staff responded quickly. They switched on the fluorescent lights, the air-conditioner and a wall fan.

The barber, a young man, with hair reaching his shoulders, in a blue T-shirt and khaki pants, asked me what I wanted.

I showed him a Google image of a bald man on my mobile.

“Okay,” he said.

So, he clipped on a brown gown around my neck. And then got to work. He only needed a razor. And he started at the back and worked his way to the front. As he scraped away, I prayed, ‘God, please make me have a round head.”

Ten minutes later it was over. I stared at myself in the mirror and felt relief. It didn’t look bad at all. And I had a smooth round head. I asked the barber whether there were any warts or cysts at the back of the head. He said it was smooth, but through a mirror, he pointed at a slight indentation at the base.

Back home, when I looked at the mirror, I saw a red birthmark on the front slope. It looked pear-shaped. Otherwise, everything looked fine.

When the family saw it, they liked it, including my in-laws. So, I crossed the first hurdle.

And then when I had my bath, I used a mug followed by the shower. With the mug, the water seemed to rush into my ears, but in the shower, I felt a drumming on my head. It was like getting a massage.

After I towelled myself, by habit I opened the storage cabinet and saw three familiar bottles, blue, white and green. The Parachute coconut oil which I used to rub on my hair after my morning bath. The shampoo that I used during the night bath. And an Ayurveda hair oil.

This is the story behind the shampoo. In April, 2012, I travelled to Chennai from Kochi to do a story on trichologist Dr Talat Salim who provides herbal cures for hair loss for men and women. At the end of the interview, I did my personal consultation. And Dr Talat recommended a shampoo called Silkworm which would do the least damage to my hair. So, I started using Silkworm shampoo ever since. I have to give credit to her because she told me that my hair loss was irreversible.

Then two years later, I met a paraplegic woman. Her companion, who looked after her, had a thick mass of hair that went all the way to her waist. She told me she used an Ayurveda hair oil. And showed me the bottle. So I also started using it. Every alternative night, after my bath, I would rub it into my hair.

But, as Dr Talat said, the hair loss was irreversible. Now I looked at all the three bottles and they stared right back at me. They could visualise the future: a permanent split was on the cards. Sorry, guys. I had to apologise to my comb, too.

Meanwhile, you might wonder whether any woman has looked at me. So far, none. My track record before the haircut: the same as above. I don’t think a bald pate is going to change things at all.

But there have been good moments recently. The other day, when I set out for a run in the evening, it was raining gently. And it felt pleasant to feel the drops fall on my head.All told, I feel nice. I no longer have to worry about the onrushing grey hair and other such dissatisfactions which can crop up when you have a head of hair.

For all those who are hesitating to take the plunge, I say, “Do it. You will have no regrets.”

And, who knows, you might have better luck with the women.

(Published in The Kochi Post)

Published on June 05, 2020 20:44

June 2, 2020

A haven for bruised souls

Sachithra Soman runs a shelter for dogs and cats, at Kochi, many of whom have paralytic injuries

By Shevlin Sebastian

At 11 p.m. Sachithra Soman lies down on a mattress which is placed on the floor next to a wall. Within moments, 25 cats and kittens will find different places on the bed, curl up and sleep. But there are exceptions. Honey, a one-year-old cat, always lies on Sachithra’s stomach and nibbles at her nightie. Sreekutty and Aishwarya nibble at her ears. All three cats lost their mother a few days after they were born. “They miss nibbling milk from their mother,” says Sachithra. “Honey thinks I am the mother.”

Because of the three, Sachithra sleeps straight on her back, with her hands at the side, and avoids turning to the left and right. “It’s tough,” she says, with a smile. “But I have got used to it.”

Her rented house, near Marottichuvadu Junction at Edapally, Kochi, has an area of 15 cents. It is set away from the main road, down a narrow private lane. There is a sizeable area in front of the house and at the side, there is a muddy section where Sachithra grows vegetables. Apart from cats, there are nine dogs. A few of the dogs are injured.

Muthu used to stay in front of the Tellicherry Kitchen at Kathrikadavu. At night, the employees would throw scraps of food at Muthu. One day, a car hit the dog. It became paralysed. A few local volunteers were informed. They took the dog to the hospital. The doctor suggested euthanasia. But they were reluctant. The dog received treatment for one month. A dog wheelchair was bought for Rs 7500, and a waterbed for Rs 1800. The total bill came to Rs 25,000. All of them, including Sachithra, are part of a Facebook group of animal lovers. Well-wishers paid the bill. Then Muthu was given to Sachithra. She looked after it. Today, Muthu can walk, but with a limp.

Muthu is the only male. The females have names like Bhavana, Menaka, Reshma and Bhagyani. Sachithra has a sense of humour. She calls two cats by the name of Ambani and Adani.

Sachithra came in the news recently when she began feeding dogs during the coronavirus lockdown. “I realised that many of them were starving,” she says. So, every evening, Sachithra and other volunteers fed about 150 strays in different parts of Kochi.

On the first day, the dogs stayed away and watched Sachithra place the packet. They approached it only when she moved away. “They are afraid of human beings,” she says. “But on the third day, they started jumping on me and expressed their love.”

Once again, well-wishers sponsored the cost.

At her home, Sachithra wakes up early. And she ensures she cleans up all the ablutions. Then she sweeps the house and makes the meals. Just before 10 a.m., she feeds them rice, chicken and dog food like Pedigree, Chappie, and Drools. Then she places bowls of water at different places and leaves. She works as a salesperson in a private company. This was the routine before the lockdown. When she returns at 6.30 p.m., she gives them another meal.

If she is late, all the cats will stand near the gate looking anxious and worried.

“Many people say that cats have no love or attachment,” says Sachithra. “But my experience has been different. They are very loving. But they like to be loved, too.”

As for the dogs, Sachithra shows her love by bathing them once every ten days. She uses a scrub, dog shampoo and water. But most of the dogs don’t enjoy it. “That’s because they have never had a bath like this before,” she says. “They are strays and feel scared. Muthu refuses all the time.”

Asked how she developed a love for animals, Sachithra says that her father housed many cats in their home at Kilimanoor. “When my father came across an abandoned cat, he would bring it to the house,” she says. “I felt empathy for them.”

This empathy remained dormant. Then, one day, Sachithra and her friends went to the Ernakulam Town station. They were waiting to board a train to attend the Thrissur Pooram festival. As she looked around the platform, Sachithra saw a kitten at one corner. “Nobody cared for it,” says Sachithra. “It seemed to me as if it was about to die.” So, she picked the kitten up, put it in a basket and took it to Thrissur. She was wondering how she would take care of it. But in Thrissur, her friend, the nurse Papa Henry offered to look after it.” [Papa was in the news when she offered to work in any hospital in Kerala for COVID patients.]

When she returned to Kochi Sachithra got an idea of starting an animal shelter. And she set up one. But there have been hurdles. The house at Edappally is the sixth one she has rented. Because everywhere, the locals have objected.

This is in stark contrast to Mumbai where she lived for several years and had dogs in her ground-floor apartment. All her neighbours supported her and fed the animals themselves. When she relocated to Kochi, they promised to look after the dogs.

But in this area, too, the local people have raised a protest. The residents of a five-storey building, in the next plot, have given a complaint to the Cochin Corporation.

At 6.30 a.m., on a Sunday, Ajitha Thankappan, the local councillor of the Corporation came to Sachithra’s house and told her that as a tenant, she could not run an animal shelter. Sachithra replied that according to the Indian Constitution, owners and tenants have equal rights to run an animal shelter. “I am not doing anything illegal,” she says. “The corporation has failed to look after these strays. And now, they are trying to prevent someone from taking up this responsibility.”

Ajitha says she had received several complaints from Sachithra’s neighbours. They say the barking of the dogs is constant, especially at night. “There are old people who live nearby,” says Ajitha. “They find it difficult to handle the noise. They also told me this is a residential area, and it is not the right place to have an animal shelter.”

Sachithra admits the barking of dogs does happen but not often.

Meanwhile, the Corporation has sent a notice asking Sachithra to make proper arrangements to house the dogs, a possible shed, and for the removal of faeces in a scientific way.

Following Ajitha’s visit, Sachithra has also filed a police complaint. One dog named Arun died suddenly. She suspects that he had been poisoned. The wall of the neighbouring building is broken. So dogs can jump into the parking area. Maybe somebody did some mischief.

Natural deaths have also taken place. This month, a 12-year-old dog stopped eating. Sachithra took her to the hospital. The vet said that the liver and kidney had stopped functioning. So, she brought the dog back. It died four days later. A few months ago, ten kittens died when they were afflicted with panleukopenia (this is a contagious viral disease of cats).

“I felt so sad,” she says. “They were my babies.”

And she has to carry them to the yard, take a spade, make a hole and bury them.

Incidentally, all the dogs and cats are up for free adoption. All you have to do is to go to the shelter, select the animal, prove that you are sincere and take the pet you want.

You have to hand it to her. This is a one-woman show. Sachithra does not have any helpers. Most maids don’t want to work with animals. “The love of my dogs and cats sustains me,” she says, with a smile.

(Published in The Kochi Post)

Published on June 02, 2020 02:03

May 30, 2020

“The Kochi Biennale will take place”

Says Bose Krishnamachari, one of the co-founders

Pics: The ARCOMadrid Art Fair; the exhibition area converted into a quarantine zone; Bose Krishnamachari with ARCOMadrid Co-Director Maribel Lopez; Bose with his family

By Shevlin Sebastian

On February 28, Bose Krishnamachari, co-founder of the Kochi Muziris Biennale, walked about the massive exhibition area of the ARCO Madrid Art Fair. He had been invited as a delegate by the Embassy of Spain and Instituto Cervantes. This was one of the most prominent fairs in Spain. Around 1300 artists, 500 collectors and 200 gallery owners took part. During the four-day event, there were 93,000 visitors. Bose gazed at large paintings hung on gallery walls, checked into book stores and listened to discussions on art.

But three weeks later, Bose got a shock when he saw a photo. The entire exhibition area had been converted into a quarantine zone as the coronavirus went rampant in Spain. There were many beds, in long rows, covered with pristine white sheets and pillows. “That’s when I realised the gravity of the situation,” he says.

Since the beginning of March, Bose has been in lockdown at his apartment in Mumbai. And, this was the first time in ten years, he has been with his family for so long. So, he has passed the time by playing cards, chess, and snakes and ladders with his children Aaryan, 17, and Kannaki, 14.

Aaryan, who is doing his Plus 2, is studying science, architecture and design at the Ramnarain Ruia College, while Kannaki is in Class 9 at the JBCN International School. On May 27, they celebrated her birthday. Bose’s wife Radhika made a heart-shaped chocolate cake, with chocolate shavings on top, and placed a single candle on it.

Bose has also been leafing through albums of his children’s birthdays, his wedding and his many travels. “It triggered interesting memories,” he says. “I felt a keen sense of nostalgia. I have always taken photographs of my travels and made albums.”

In the early mornings, he goes to the terrace. At one side there is a green space. The Japanese green bamboo has grown six feet high. Using a hose, he waters the jasmines, roses and curry leaves.

On most days, he is in touch with the team members of the Kochi Biennale Foundation who are working from out of their homes and with the curator, the Singapore-based artist Shubigi Rao.

Bose is confident that the nearly four-month-long Biennale will start on time, on December 12. “Shubigi has short-listed the participants,” says Bose. “Now, only Kerala artists need to be selected. Before the lockdown happened, Shubigi had already travelled to 35 countries.”

Asked about the likely impact of social distancing, Bose says, “Public health and safety are most important. We are already in touch with museums and art organisations to learn the best practices for visitor management, communication, and sanitisation. There will be some changes in exhibition design.”

He is hoping that despite the funds’ crunch, the Kerala state government will support the art festival. “It will help revive tourism in the state and give a boost to the local economy,” he says. “People are keen to see it takes place. I’ve got calls from international gallery owners and collectors who want to book their hotel rooms in advance.”

He is hoping the Centre will also lend a helping hand because culture is one of the country’s biggest assets. “But, unlike Europe and America, we have not learned how to project and market it,” he says.

In a recent webinar with Central government officials and festival directors, Bose urged them to open one museum in each of the 29 states but there was a lukewarm reaction. Bose feels that in India the awareness about the soft power of culture is yet to happen.

This year, despite the impact of COVID-19 on their economies, Germany, France, Canada and the United Arab Emirates have increased their cultural budgets. “They know they have to preserve their institutions,” says Bose. “Tourism contributes a lot to their economies.”

Bose is very appreciative of the Kerala state government, which is planning to open a major cultural centre in each of the 14 districts. “The state has become a front-runner by pumping in Rs 50 crore in each district. If the Centre can contribute Rs 100 crore to each of the centres, then the cultural investment will be proportionate to the cultural potential,” says Bose.

Meanwhile, regarding his artistic work, Bose has been doing some drawings. He could not go to his studio because it is too risky in Mumbai to step out. The city has one of the highest infection rates in the country.

As to whether the pandemic will have a damaging effect on art, Bose shakes his head and says, “On the contrary, there will be a heightened interest in art and culture. People have had the time to reflect on what are the most important things in life.”

(Published in The Kochi Post)

Published on May 30, 2020 01:26

May 29, 2020

The teaching never stops

Rufus D’Souza has completed 50 years of football coaching at the Parade Ground at Fort Kochi

By Shevlin Sebastian

On the morning of May 19, news photographer Vikas Ramdas went to Burger Street in Fort Kochi to have a cup of coffee with Rufus D’Souza. Thereafter, he took a video. The football coach was celebrating his 50th year of training young lads at the Parade Ground.

In the video, Rufus said, “I have been treated with great respect in Fort Kochi. Almost everybody calls me Uncle.”

Vikas uploaded the video to Facebook. As a result, many people came to know about Rufus reaching his landmark.

A day later, I reached his house, set away from the main road. There was a large tree in front, green plants and chipped stones on the ground. At 88, Rufus has an unlined face, looks years younger, and has a tranquil smile. Scribes had been calling him, he said. In an hour, the local MLA KJ Maxi would be dropping in to congratulate him.

But like most things in life, Rufus’ coaching began accidentally. On May 19, 1970, he went to the Parade Ground with a ball and a hockey stick. The aim was to sharpen his dribbling and shot-making skills. A day later, Rufus’ neighbour D’Costa asked whether he could help train his son Sam in football. Rufus agreed.

The next day, Rufus told Sam to run with the ball, while he continued to train as a hockey player. However, over the next few days, more boys came. And that was when Rufus took it seriously.

So, every morning, at 5.30 a.m., he would be at the ground. All the players have to arrive punctually. If any of them is late, he asks them to go back.

There are other rules. All must come in their football kit. “There should be no jazzy hairstyles,” says Rufus. “I will not accept it. Neither will I accept drinking, smoking or taking drugs. Nobody can use the words, “Eda (hey you) or ‘poda’ (get lost).”

The coaching -- two hours in the morning and evening -- is done for free, because many of the boys come from poor families. However, if some well-off parents were to give a dakshina (donation), Rufus does not refuse. He uses the money to buy jerseys, stockings, shin pads and boots for the poor children.

In his coaching, Rufus imparts the skills of dribbling, passing, kicking, stopping, and taking a penalty.

Asked the technique to hit a successful penalty, Rufus says the player should select a spot in the goal where he wants to hit the ball. He should keep that in his mind’s eye. And as he runs to take the shot, he should only look at the ball. “If he looks at the movements of the goal-keeper, the player will lose his concentration,” says Rufus.

As for the goalkeeper, he should also keep an eye on the ball. “Many players do feints as they approach the ball and that can be distracting,” he says.

The tips pour forth like an onrushing waterfall during the monsoon season. “The most important skill in football is to receive the ball,” he says. “Ideally, you should be away from the opponents, in vacant spaces. You should use the inner and outer foot. Throughout the game, you should keep an eye on the ball, your colleagues and the opponents.”

Not surprisingly, he has produced many players who did well. They include Dinesh Naik who played for the Indian hockey team in the Sydney Olympics (2000) and captained the Kerala and Tamil Nadu state teams. Feroz Sharif was the Indian goalkeeper for the 1997 Nehru Cup, 1998 Asian Games, and 1998 FIFA World Cup qualification matches. He is the current coach of the Indian team. KA Anson played for Kerala, FC Kochin and India. PP Tobias and Hamilton Bobby played for the Kerala junior team as well as India. Anil Kumar, who is the secretary of the Kerala Football Association, was captain of the MG University captain and All-India Services team.

Despite his intense passion for the game, Rufus does not watch international football on TV. “It’s very boring,” he says. “In our time, there was 70 minutes of football. For 50 minutes, the ball was moved forward. Nowadays, there is 90 minutes of football. Out of that, for 20 minutes the ball is played forward and 70 minutes it is played backwards. So what is the charm in it? They developed this style because the players don’t want to get injured. They want to play safe.”

But Rufus has never hesitated to attack the goal when he played. This may be due to his sporting genes. His father Louis D’Souza was a hockey goalkeeper, while mother Dorothy played basketball. Rufus was adept at both football and hockey. “I practised very hard, with sincerity and dedication,” he says.

In 1954 Rufus captained the Travancore State hockey team in the Bangalore Nationals. During 1961-62, Rufus played football for the Western Indian Match Company for the princely sum of Rs 10 per day. In 1962 Rufus joined the State Bank of India (SBI) in Madras.

“I helped Madras State win the first Southern Pentangular tournament,” he says. Rufus also played for South Zone in hockey and football. In 1971, Rufus became the captain of the Kerala hockey team.

Interestingly, he has remained a bachelor. “I was not sure what sort of partner I would get,” says Rufus. “But I have no regrets. Instead of being a father to only two children, I am the father of so many boys. In any case, I am married to football..”

But he is not alone. His brother and family stay with him. In his living room, his sister-in-law Nancy offers tea and biscuits with a warm smile.

(Published in Kochi Post)

Published on May 29, 2020 00:39

May 27, 2020

My friend Mark Peters

[image error]

[image error]

By Shevlin Sebastian

Photos: Mark Peters (extreme left) with South African journalist Mansoor Jaffer and Shevlin Sebastian. Photo taken by Mansoor's wife Kay

On most days, at 1 p.m., my colleague Mark Peters would come up from the circulation department on the ground floor to the editorial section on the first floor of our newspaper in Kochi and beckon to me. Then we would go to the canteen to have lunch. And our conversations could be on politics, human relationships, marriage, history, psychology, media and, of course, women. Most of the time I listened, because Mark was a natural raconteur. Since both of us grew outside Kerala, there was an easy camaraderie.

Mark had this extraordinary gift of being friends with everybody in the office. From the boss to the peon and the security guards. And in Fort Kochi where he stayed, this Tuticorin-born Anglo Indian would talk with the stationery shop owner, the fisherman, the bus conductor, homestay owners and strangers.

Once when he went into the post office, he saw a foreigner. Mark introduced himself in his impeccable English. It turned out that the man was a top shot at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) at Washington. Many big guns would roam around Fort Kochi, revelling in their anonymity and the unique charm of the town. But if Mark came across them, be it man or woman, he would unlock their identity.

And then he would make a call…. to me.

“Hi, I’ve got a good story for you,” he said.

And he was right. It would always be an interesting person to meet and do a story.

I remember Mark telling me, in December, 2011, of a South African journalist Mansoor Jaffer who had come to India, along with his wife, Kay, in search of his Indian roots in Maharashtra. But their first stop was Fort Kochi. And I met him and did a story. Kay took a picture of the three of us together and that is the only photo in which Mark and I are in the same frame.

Mark was a fount of ideas and had an unerring instinct of what would make an interesting story.

Once I told Mark he could have been such an excellent journalist.

He smiled enigmatically.

Sometimes, a story idea would come accidentally to Mark. Once, near the headquarters of the Reserve Bank of India, at Kochi, he was crossing the busy road when a bus speeded up. So, he was stranded in the middle next to the female traffic warden. So, he started chatting with her.

When he came for lunch, he told me about Sajitha.

“It’s an excellent story,” he said.

“Are you sure?” I said.

“I am,” he said.

So I met her. And Mark turned out to be right. It was an interesting story. Sajitha told me of a man who had an epileptic fit on the road right in front of the traffic. Blood and water dribbled out of his mouth. She stopped the vehicles, with an upraised palm, and placed her watch on his palm. She remembered the touch of metal helped to control a fit.

Then, with the help of bystanders, Sajitha put him in an autorickshaw and took him to the Lisie Hospital. By then, the man had become unconscious. She took his mobile, called a random number, and it turned out to be a friend. That friend informed the family members. Soon, they arrived at the hospital.

One week later, the grateful man came to the crossing and presented Sajitha with a gift. “You saved my life,” he said, with a smile.

When the article appeared, she received a lot of kudos. Sajitha thanked Mark for organising the coverage. And I thanked Mark for the idea.

Mark left the office in 2014. But we remained in touch. I would go across to Fort Kochi and have lunch or tea with him. Since the Kochi Muziris Biennale was held in Fort Kochi, as a feature writer, I went often to the venues. So, there was always a chance to meet Mark.

Then one day, one-and-a-half years ago, he called me and said, “I have grave news.”

“What is it?” I said.

“I have been diagnosed with colon cancer,” he said. “Stage 4.”

The moment I heard Stage 4, I became silent for a few moments. Stage 4 is too late. My father-in-law died of pancreatic cancer. He was in Stage 4 when it was discovered. Later, I spoke to a doctor who was a top-notch gastroenterologist. He said Stage 4 in the colon was bad news.

Mark went through several rounds of chemotherapy followed by exhaustion, loss of appetite and weight. But through all this, his voice and his thinking remained crystal clear. To raise his spirits, I would crack a raunchy joke. He laughed easily. It reminded him of delightful times -- of Christmas lunches with his family and New Year’s Eve parties.

But the odds were stacked against him.

For a while, the cancer was in remission. Then it returned with increased force.

Once when I called him, he said, “It’s all over the place .... lungs, liver.” Then his voice trailed off.

And in the past two months, Mark declined. He knew that he was going. And he felt sad that he could not see all his children: while one son remained in Fort Kochi, two sons and a daughter lived in Dubai.

His wife Evelyn told me that Mark would always ask when the lockdown would end, so he could see his children for the last time.

Sadly, the lockdown did not end.

On the morning of May 18, I called Mark. He said, “Shevlin,” and couldn’t speak further. All I heard was laboured breathing. Evelyn took the phone and said, “Mark is unable to speak.”

At 8.30 p.m., Mark complained of breathlessness. Evelyn took him to Lisie Hospital. He was put on a ventilator. But the doctor warned her that Mark could not take in the oxygen much. He said he may live for a day or two.

But it did not take that long. By 11.45 p.m., Mark breathed his last.

My wonderful friend and a fount of ideas was no more. He was only 59 years old.

Since it was not unexpected, it was not a shock. But a weight descended on my heart. I felt impoverished. The only thing that matters in life is relationships. All the rest, like fame, money, position and power are ephemeral. People remember how you behaved, not what you achieved.

At the cemetery, as I waited for the body to arrive, I overheard people say, “Mark was a gracious man.” “He was a wonderful friend of mine.” “Mark was always well-dressed, polite and with a smile on his face.”

Then the coffin arrived in an ambulance. Mourners held the hooks at the side and carried the coffin to the cemetery. The lid was removed. Mark had been swathed in white. He had white gloves with a black rosary between his fingers. A small wooden crucifix had been placed on his chest. And cream flower petals lay strewn along the length of the body. The priest said the prayers. There were fewer people around, because of the lockdown restrictions. There were trees in different areas. But where Mark was being buried, it was in the sunlight.

The coffin was laid to rest. Family members and friends threw in white flowers. It fell softly on the lid. And as the gravedigger filled up the grave with mud, Evelyn looked at her Dubai-based children, who were watching the event on a live stream, and said, “Daddy is gone…. forever.”

Yes, Mark has gone physically but he will always remain in my heart. And in the hearts of those who loved him.

And as I was returning home, I thought to myself, ‘I won’t be surprised if Mark, somewhere in the Universe, will continue to pop story ideas in my subconscious when I am fast asleep at night.’

(Published in The Kochi Post)

[image error]

By Shevlin Sebastian

Photos: Mark Peters (extreme left) with South African journalist Mansoor Jaffer and Shevlin Sebastian. Photo taken by Mansoor's wife Kay

On most days, at 1 p.m., my colleague Mark Peters would come up from the circulation department on the ground floor to the editorial section on the first floor of our newspaper in Kochi and beckon to me. Then we would go to the canteen to have lunch. And our conversations could be on politics, human relationships, marriage, history, psychology, media and, of course, women. Most of the time I listened, because Mark was a natural raconteur. Since both of us grew outside Kerala, there was an easy camaraderie.

Mark had this extraordinary gift of being friends with everybody in the office. From the boss to the peon and the security guards. And in Fort Kochi where he stayed, this Tuticorin-born Anglo Indian would talk with the stationery shop owner, the fisherman, the bus conductor, homestay owners and strangers.

Once when he went into the post office, he saw a foreigner. Mark introduced himself in his impeccable English. It turned out that the man was a top shot at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) at Washington. Many big guns would roam around Fort Kochi, revelling in their anonymity and the unique charm of the town. But if Mark came across them, be it man or woman, he would unlock their identity.

And then he would make a call…. to me.

“Hi, I’ve got a good story for you,” he said.

And he was right. It would always be an interesting person to meet and do a story.

I remember Mark telling me, in December, 2011, of a South African journalist Mansoor Jaffer who had come to India, along with his wife, Kay, in search of his Indian roots in Maharashtra. But their first stop was Fort Kochi. And I met him and did a story. Kay took a picture of the three of us together and that is the only photo in which Mark and I are in the same frame.

Mark was a fount of ideas and had an unerring instinct of what would make an interesting story.

Once I told Mark he could have been such an excellent journalist.

He smiled enigmatically.

Sometimes, a story idea would come accidentally to Mark. Once, near the headquarters of the Reserve Bank of India, at Kochi, he was crossing the busy road when a bus speeded up. So, he was stranded in the middle next to the female traffic warden. So, he started chatting with her.

When he came for lunch, he told me about Sajitha.

“It’s an excellent story,” he said.

“Are you sure?” I said.

“I am,” he said.

So I met her. And Mark turned out to be right. It was an interesting story. Sajitha told me of a man who had an epileptic fit on the road right in front of the traffic. Blood and water dribbled out of his mouth. She stopped the vehicles, with an upraised palm, and placed her watch on his palm. She remembered the touch of metal helped to control a fit.

Then, with the help of bystanders, Sajitha put him in an autorickshaw and took him to the Lisie Hospital. By then, the man had become unconscious. She took his mobile, called a random number, and it turned out to be a friend. That friend informed the family members. Soon, they arrived at the hospital.

One week later, the grateful man came to the crossing and presented Sajitha with a gift. “You saved my life,” he said, with a smile.

When the article appeared, she received a lot of kudos. Sajitha thanked Mark for organising the coverage. And I thanked Mark for the idea.

Mark left the office in 2014. But we remained in touch. I would go across to Fort Kochi and have lunch or tea with him. Since the Kochi Muziris Biennale was held in Fort Kochi, as a feature writer, I went often to the venues. So, there was always a chance to meet Mark.

Then one day, one-and-a-half years ago, he called me and said, “I have grave news.”

“What is it?” I said.

“I have been diagnosed with colon cancer,” he said. “Stage 4.”

The moment I heard Stage 4, I became silent for a few moments. Stage 4 is too late. My father-in-law died of pancreatic cancer. He was in Stage 4 when it was discovered. Later, I spoke to a doctor who was a top-notch gastroenterologist. He said Stage 4 in the colon was bad news.

Mark went through several rounds of chemotherapy followed by exhaustion, loss of appetite and weight. But through all this, his voice and his thinking remained crystal clear. To raise his spirits, I would crack a raunchy joke. He laughed easily. It reminded him of delightful times -- of Christmas lunches with his family and New Year’s Eve parties.

But the odds were stacked against him.

For a while, the cancer was in remission. Then it returned with increased force.

Once when I called him, he said, “It’s all over the place .... lungs, liver.” Then his voice trailed off.

And in the past two months, Mark declined. He knew that he was going. And he felt sad that he could not see all his children: while one son remained in Fort Kochi, two sons and a daughter lived in Dubai.

His wife Evelyn told me that Mark would always ask when the lockdown would end, so he could see his children for the last time.

Sadly, the lockdown did not end.

On the morning of May 18, I called Mark. He said, “Shevlin,” and couldn’t speak further. All I heard was laboured breathing. Evelyn took the phone and said, “Mark is unable to speak.”

At 8.30 p.m., Mark complained of breathlessness. Evelyn took him to Lisie Hospital. He was put on a ventilator. But the doctor warned her that Mark could not take in the oxygen much. He said he may live for a day or two.

But it did not take that long. By 11.45 p.m., Mark breathed his last.

My wonderful friend and a fount of ideas was no more. He was only 59 years old.

Since it was not unexpected, it was not a shock. But a weight descended on my heart. I felt impoverished. The only thing that matters in life is relationships. All the rest, like fame, money, position and power are ephemeral. People remember how you behaved, not what you achieved.

At the cemetery, as I waited for the body to arrive, I overheard people say, “Mark was a gracious man.” “He was a wonderful friend of mine.” “Mark was always well-dressed, polite and with a smile on his face.”

Then the coffin arrived in an ambulance. Mourners held the hooks at the side and carried the coffin to the cemetery. The lid was removed. Mark had been swathed in white. He had white gloves with a black rosary between his fingers. A small wooden crucifix had been placed on his chest. And cream flower petals lay strewn along the length of the body. The priest said the prayers. There were fewer people around, because of the lockdown restrictions. There were trees in different areas. But where Mark was being buried, it was in the sunlight.

The coffin was laid to rest. Family members and friends threw in white flowers. It fell softly on the lid. And as the gravedigger filled up the grave with mud, Evelyn looked at her Dubai-based children, who were watching the event on a live stream, and said, “Daddy is gone…. forever.”

Yes, Mark has gone physically but he will always remain in my heart. And in the hearts of those who loved him.

And as I was returning home, I thought to myself, ‘I won’t be surprised if Mark, somewhere in the Universe, will continue to pop story ideas in my subconscious when I am fast asleep at night.’

(Published in The Kochi Post)

Published on May 27, 2020 00:04

May 23, 2020

Trying to weave magic again

His debut novel, ‘The Carpet Weaver’ was a best-seller. The gay Afghan vegan author Nemat Sadat is busy at work on his second book

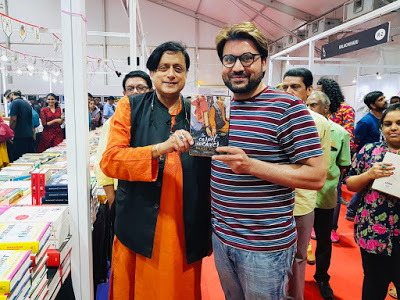

Pics: Nemat Sadat at his mother's house in San Diego; with author and politician Shashi Tharoor

By Shevlin Sebastian

At 8 a.m. in San Diego, USA, author Nemat Sadat awakens. As he has a cup of coffee, he switches on the TV and watches the news. Not surprisingly, it is all about the coronavirus. He rubs his hand through his hair -- a mix of ash blonde highlights and natural dark brown hair.

Nemat is slim and tall; this is accentuated by the tight blue t-shirt that he is wearing. He sits at his desk, at his mother’s home, and switches on the laptop.

He is at work on his second novel titled, ‘Keeping Up With The Hepburns’, which is set in the present-day America of President Donald Trump. “My hero, a young gay vegan Afghan has a spiritual awakening after he meets his twin flame,” he says.

Nemat feels confident and optimistic about this book, because his debut novel, ‘The Carpet Weaver’ has created waves. It has sold 6750 copies in the Indian subcontinent before Covid-19 brought sales to a halt. This is amazing since most first novels sell a few hundred copies only. On June 14, he will celebrate the first anniversary of its publication.

The ‘Carpet Weaver’ tells the story of Kanishka Nurzada, the son of a leading carpet seller in Kabul. He falls in love with his friend Maihan. In the late 1970s and early 80s, when the book is set, until today, gays in Afghanistan face the death penalty.

“In Islam, if a man loves another man it is an abomination,” says Nemat, who moved from Kabul to Germany with his parents as a baby and then resettled in the US when he was five years old. “The first line in my book states: ‘The one thing I know is that Allah never forgives sodomy’.”

Incidentally, in 68 countries, mostly in Asia and Africa, Lesbians, Gays, Bisexuals and Transgenders (LGBT) are regarded as criminals. The punishment includes life imprisonment or the death penalty.

Nemat felt compelled to tell this story because he wanted to be a catalyst for those who hide in the closet and the shadows.

As to why he used the name of Kanishka, Nemat says, “It was inspired by the Emperor Kanishka the Great who ruled over ancient Afghanistan.”

It took Nemat 11 years to write the novel, as he was busy trying to earn a living. He worked as an editorial assistant at the ‘United Nations Chronicle’, as a production intern at journalist Fareed Zakaria’s popular TV show ‘GPS’, hosted by CNN and as a production assistant at ABC News’ Nightline show.

When he approached Western literary agents, he got rejection after rejection. Overall, 450 agents said no. “In the US, there is too much political correctness,” says Nemat. “They were worried about the reaction from the Muslim world. They remembered what had happened to Salman Rushdie’s ‘Satanic Verses’ [the late Ayatollah Khomeini, Iran’s de facto ruler, issued a fatwa in 1989, along with a $6 million bounty, to kill the author for blasphemy]. I am a gay, ex-Muslim, and writing about the LGBT community in Afghanistan. They felt it was safer to say no.”

Another likely reason was the negative Western attitude towards Muslims in the USA and UK deepened following the attacks on the World Trade Centre on September 11, 2001. “All Muslims are looked upon as terrorists,” says Nemat. “And after America’s difficult military experience in Afghanistan, it is regarded as a barbaric place. Anything that comes out from there is villainous.”

Finally, Nemat approached the New Delhi-based literary agent Kanishka Gupta of Writer’s Side Agency. “As soon as Kanishka read the manuscript, he said, ‘This will be a big book’,” says Nemat. “We got many offers and went with Penguin Random House India. It was the most written-about debut fiction book last year. The reviews have been positive.”

Despite that, Nemat pushed hard. He came to India and did several interviews with print, TV journalists and radio jockeys. He took part in literary festivals, at Mumbai, Delhi, and Kolkata, spoke at college functions and remained active on Facebook, YouTube, LinkedIn, Twitter and Instagram. And in November, last year, at the Tata LiteratureLive Festival in Mumbai, Nemat also hosted a writing workshop titled ‘Unputdownable: How to Write a Commercially Viable Novel’.

Nemat had also come to Kochi in February during the Krithi Book Festival. I met him for a 90-minute chat over cups of tea and vegetable cutlets. He laughed easily, and his eyes crinkled with amusement, as he mocked the West and the anti-gay crowd.

Nemat became super-excited when he had an accidental meeting with the Thiruvananthapuram MP Shashi Tharoor at the Penguin book stall. They posed for a photo with both holding the book up. While Tharoor wore a saffron juba and a black Nehru jacket, Nemat was in a striped maroon and blue T-shirt and faded blue jeans.

Later, the MP tweeted about the encounter: ‘Had a serendipitous meeting with gay Afghan author Nemat Sadat, whose first novel “The Carpet Weaver” is making waves and has propelled him on a 55-city tour through India. Great to see young Afghans finding a new literary voice’.

Nemat had then said, “Maan, he’s got 7.5 million followers on Twitter. What a boost for me.”

Asked how important marketing is for the success of a book, Nemat says, “Very important. Readers have to be aware about your book. The first 90 days, after publication, is make-or-break. But you have to write an excellent book. Otherwise, it will fall apart.”

In his travels to publicise the book, Nemat enjoyed the interaction with readers. In Mumbai, he met a woman, whose son had come out as a gay. “She had accepted it, but when she read my novel, she understood what the journey is like for a member of the LGBT community,” says Nemat. “Now she empathises with her son, not only as a mother, but as a human being.”

As for India as a country, Nemat shakes his head in wonder. “India is not a monolith,” he says. “What surprised me was the provincialism. It didn’t matter which city I visited, most people identified themselves first as Delhiites, Kolkatans, Kochiites, and Mumbaikars before they regarded themselves as Indian. Being Indian was their second or third identity. That surprised me, coming from Afghanistan and the US.”

Nevertheless, he loves the openness. “Well-read Indians, especially those who are working in the publishing business, are broad-minded and open to fresh ideas,” says Nemat. “That’s because India embraces unique perspectives. The country doesn’t have a dominant narrative, like Afghanistan, which is shaped by Islam and Pashtun nationalism or the United States, which is dominated by ‘race’, whiteness and American exceptionalism.”

However, in India today, he says, Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the Bharatiya Janata Party are trying to impose a Hindu nationalist narrative. “But in a country as diverse as India, creating such a majoritarian narrative would require many people to sacrifice their identities,” he says. “It will send India back to the days of colonialism when the British imposed an Anglo cultural narrative. That’s why, at every turn, religious minorities and secular Indians are resisting and pushing back against the Hinduisation of India.”

Meanwhile, back in San Diego, Nemat is tapping the keys in a steady rhythm on his laptop. Words, sentences and paragraphs form on the screen. He wants to finish the first draft by May 27. Because the next day, he will resume an MA in writing at Johns Hopkins University. Of course, owing to the coronavirus, he will be doing the work online.

So, it’s eight to ten hours of writing every day, with breaks for lunch and a jog in the evening. At night, he either reads a novel or watches a film.

The literary journey of Nemat Sadat continues...

(Published in The Kochi Post)

Published on May 23, 2020 02:34