Shevlin Sebastian's Blog, page 29

February 20, 2020

Telling unique stories

On a recent visit to Kochi, one of India’s leading documentary-filmmakers Chaitali Mukherjee talks about the joys and pitfalls of the profession

Pics: Chaitali Mukherjee. Photo by A. Sanesh. Chaitali with Varghese Thomas, the founder of Affluenz

By Shevlin Sebastian

It was 9.30 p.m. on a Monday sometime ago. Documentary film-maker Chaitali Mukherjee was travelling through a forest moving towards Bhadrachalam in Andhra Pradesh. It was pitch-dark on both sides. Inside the Qualis, Chaitali was sitting along with a few crew members, apart from the driver. And even though they were travelling for a long time, no vehicle had come from the other side. Chaitali was feeling apprehensive. Already, in a village where she had been shooting, the locals had warned her that it was not safe to travel at night due to the presence of Naxals. But the driver had shooed away their worries. And so, they had set out.

But the warning had turned out to be prescient. In the distance, several men and women stepped out onto the road. They were wearing Army fatigues and held AK-47 machine guns. They waved the vehicle to a stop. Chaitali told them who they were.

They told her to wait. At one side, in a clearing, the Naxals were giving a speech to the villagers. It was only after the meeting was over, three hours later, that they were allowed to leave. “I felt so relieved. It was a close shave. Anything could have happened,” says Chaitali, at her hotel in Kochi. She had come to conduct a workshop titled ‘Eyedeology’, for mass media students, aspiring filmmakers and professional videographers at Sacred Heart College, Thevara. This was conducted by Artfluenz in collaboration with SH School of Communication.

Chaitali is the right person for this. She has been one of India’s leading documentary filmmakers for the past 20 years. So far, she has made 30 films, out of which 15 have been stored in 400 film libraries worldwide.

Chaitali won the 2013 Asian Pitch for her documentary ‘My Land is Burning’, and the New York Films and Video Award for the film ‘Himalayan Tribes: Pure Love Pure Sex”. This is a film about the system of polyandry and polygamy among the Kinnauri, Gaddi and Jaunsari tribes.

“The Kinnauri tribe practises polyandry,” says Chaitali. “One woman has two or three husbands. This system exists because people want to keep the land within the family. The Jaunsari tribe, on the other hand, practise polygamy (many marriages), and polyandry (one man, many wives).”

All these practises are coming to an end because the people are getting educated. “The problem is that the children do not know who their parents are,” says Chaitali. “It is a system where women are at a disadvantage. Sometimes, they do not live long because of too many children with many husbands. There is also a lot of jealousy and in-fighting among the wives. Also, the man can walk out at any time. So the burden to look after the children falls on the woman.”

Some of the other subjects which Chaitali has tackled include human interest, anthropology, environment, rural lifestyle, sports and personality-based documentaries. The personalities featured include Magsaysay Award winners Mahabir Pun, Ela Bhat, Kailash Satyarthi, Prakash and Mandakini Amte. She has also done a documentary on Everest climber Santosh Yadav.

Her films have been shown on the National Geographic, ARTE France, France 5, Al Jazeera, and MediaCorp channels. But she bemoans the fact that documentaries are not shown on Indian channels.

“We are still watching Nat Geo and Discovery,” says Chaitali. “Why don’t we have an exclusive Indian documentary channel? Everybody comes to India, shoots and goes back with our stories. We Indian filmmakers don’t get funds. Most of the time, we have to fight to get something. Foreigners easily get permission to shoot anywhere, like inside Tihar Jail. The authorities don’t think we are as good as the foreigners.”

Meanwhile, when asked about the qualities that a good film-maker needs, Chaitali, who has M.Phil in Modern History, says, “You have to be knowledgeable and be curious about the world. You have to look out for unique stories that people do not know if you want to get a world audience. Many Indian filmmakers choose subjects, like poverty, which have already appeared in the media.”

If the idea is not unique then it is difficult to get funding. “Apart from that, you need to make a captivating five or eight-minute short film about the project,” says Chaitali. “Thousands of people are applying from all over the world. The funds are given by the Britdoc fund, Sundance Festival. AsianPitch and many others.”

As for her future plans, Chaitali says she is planning to make a film, in association with Artfluenz, on Kochi and its rich history, heritage, cuisine, important cultural festivals like the Cochin Carnival and Kochi-Muziris Biennale, as well as the Royal family of Cochin. “I will probably start shooting in December when the next edition of the Biennale starts,” she says, with a smile. “I love Kerala.”

Published on February 20, 2020 22:01

February 17, 2020

The colours of life

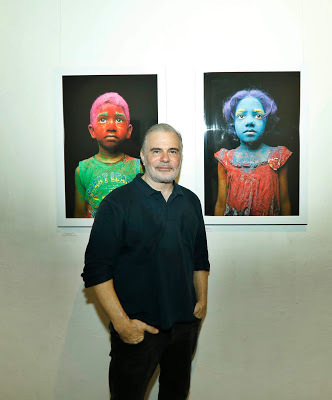

Veteran American photographer Bob Duncan puts coloured powder on men and children and comes up with striking images. These are displayed at the ‘Cochin Colours’ exhibition at the Kashi Art Gallery in Fort Kochi

Photos: Bob Duncan. Photo by Arun Angela. Faizal who sells lemon juice

By Shevlin Sebastian

When veteran American photographer Bob Duncan was walking about in Fort Kochi, he came across stalls selling brightly-coloured powder. It seemed similar to the powder used during the festival of Holi. An idea suddenly struck him. To take photos of subjects with the powder smeared on their faces and hair.

When he initially approached people, they told him, “Holi is not a festival of Kerala, but of North India.”

Anyway, one day, Bob was able to persuade a Spanish woman to take part in the project. As the shoot took place, in front of a black velvet cloth, at the back of a homestay another Malayali friend and his family were watching. Soon, they agreed to be subjects, too.

So, Bob selected their children, Ann Mary Bejoy and Ainn Lionel. While the girl had a blast, for Ainn, some powder entered his eyes. “He cried a bit, but settled down later,” says Bob. In the photo, Ainn looks a trifle unhappy with his face smeared in red, purple powder on his hair and dabs of green on his neck and upper arms. In contrast, the white of his eyes is striking.

Ann, on the other hand, has a blue face, purple hair, with green eyebrows. All these portraits are on display at Bob’s photo exhibition called ‘Cochin Colours’ at the Kashi Art Gallery, Fort Kochi. The show concludes on February 26.

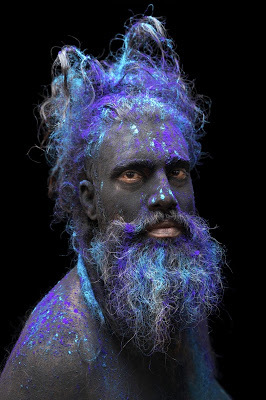

In search of an adult, Bob came across Faizal who sells lemon juice. He had dreadlocks, a flowing beard, a thick moustache and bushy eyebrows. Nearly everybody in Fort Kochi knows the vendor.

Faizal reminded Bob of the photos he had seen of sadhus, with ash smeared on their faces at Varanasi. So the American approached Faizal and the latter agreed to be photographed.

After the shoot, Bob felt happy. “These shots seem to bring out a different dimension in people,” says Bob.

For the past five years, Bob had been doing a project called ‘Noir Portraits’, where people with outlandish make-up and colourful costumes would pose in front of a black velvet background. Taken in New York, Los Angeles, London, Paris and Madrid, these be can be seen on his Instagram page @duncanfotos and @duncan_faces.

And over time he realised that when his subjects wore exotic make-up, they are relaxed because they feel that nobody can see their actual faces. “But because they are relaxed, their true character comes out, especially if you look into their eyes,” says Bob. “You no longer see the make-up but the faces.”

But the subjects must not smile. “When people smile, we only see the smile. When a person is not doing so, many layers of who the person is begin to show up,” says Bob. “Leonardo Da Vinci’s ‘Mona Lisa’ would not be as intriguing if she was smiling. In classical paintings, people rarely smile. As a result, you can look at the images over and over again. And you can detect the different moods which include sadness, serenity, anger and bitterness. We meet people having these moods every day.”

There is a famous photograph of the late Hollywood icon Marilyn Monroe taken by internationally renowned photographer Richard Avedon where she looks tired, exhausted and pensive. “Richard did a session with her all afternoon, in which she was smiling and everything was wonderful,” says Bob. “When the session was over, Richard asked Marilyn, ‘Can I continue to photograph you?’”

She agreed. And what was how Richard got the image of a depressed Marilyn.

Meanwhile, Bob, who had come to stay in Fort Kochi for three weeks, has clocked ten months now. He has been living in big cities like New York and Paris for decades and feels exhausted. “Most cities are loud, stressful and tiresome,” says Bob. “I have never lived in a small place before. Fort Kochi is a small village. It is soft and calm. People smile at you. They say ‘Good morning’ to me. It beguiled me.”

He remembers seeing an accident between a bike rider and a car driver. As the men raised their voices, people hurried up and an amicable solution was quickly reached. “In Los Angeles, pedestrians or other drivers would not have bothered to stop at all,” says Bob.

Now, he is planning to go to Varanasi to take photos using the Holi powder. “I hope to bring out a photo book on the subject,” he says.

(The New Indian Express, Kochi and Thiruvananthapuram)

Published on February 17, 2020 22:17

February 16, 2020

Working with Mother Earth

Artist Haseena Suresh runs the Clayfingers Pottery Studio, which is celebrating its tenth anniversary. Visitors learn the art of making beautiful pottery

Photos: Haseena Suresh. Photo by Albin Mathew. Pots

By Shevlin Sebastian

Senior British citizens David Norfolk and Irma Lowe are standing inside a large hall at the Clayfingers Pottery Studio at Urakam, Thrissur. Wearing orange aprons, they learn to make a cup using a pottery wheel. Then using a knife, David etches the letters, Irma, in capital letters at the back of the cup. Irma gives a happy laugh when David shows it to her.

In a brick-walled hall, you can see a wide variety of pottery items: bottles, jars, vases, kettles, cups, mugs, and lampshades which have been neatly placed on several shelves. Outside, there are brick cottages for visitors who would like to stay for a few days to learn pottery. At a distance, there is a huge brick chimney. Beneath it is a large wood kiln.

The studio was set up by artists Haseena Suresh and Suresh Subramanian ten years ago in a ten-acre patch of land. And one of the main reasons was Haseena’s interest in pottery. Even when Haseena was doing her masters in sculpture from Shantiniketan University in West Bengal, she was always looking at the pots.

“This interest is natural for human beings,” says Haseena. “Mankind began their art through pottery from the Palaeolithic and Neolithic Age. Pottery has also been used for cooking, burial and storage. It was very important for human beings for a long time.”

When the couple shifted to Dubai in 1998, Haseena met a British potter called Homa and learned pottery from her. Thereafter, when the couple travelled., they would always visit pottery studios in places like Italy, France, England, Germany, and Canada.

“I began to appreciate the beauty of studio pottery,” says Haseena, who was a panellist at the Talkathon titled, ‘Life For Design’ at the recent Kochi Design Week programme.

Meanwhile, at the studio the process is simple. The clay is put in water for several days. Then it is passed through a mesh so that the impurities remain behind. After that, it is poured onto a bed of Plaster of Paris. Then it is wedged and kneaded, to make it more pliable. Thereafter, the mud is put out to dry.

Then you use a pottery wheel to start making a cup or a vase. After the basic design is formed, there is a curing time, when the item is put out in the sun. Then it is taken to the kiln, where firing takes place.

Following that, the surface is glazed. Only natural minerals are used.

The end products, like terracotta, glazed stoneware and hand-painted decoratives are exceptionally beautiful. “We also have functional items, like mugs and cups, but our focus is on art pottery,” says Haseena. “We want to appeal to those who have an aesthetic sense.”

One of the pioneering artists of art pottery was the Japanese Shoji Hamada (1884-1978). Haseena was much influenced by him. “I wanted to bring Hamada’s philosophy to India where pottery had long been regarded as only a practical craft with no artistic merit,” she says.

So, the studio has been giving training to students from all over India and the world. “Lessons are provided to suit the individual person, regardless of experience,” says Haseena. “Many have gone on to pick up studio pottery as a lifelong passion, working in studios in their free time or even professionally.”

At Urakam, there is a group of freelance potters who work closely with Haseena and Suresh. They were used to making traditional items like cookery bowls, and jars for storing drinking water. “But after receiving training from us they are trying new things,” says Haseena.

As she designs a cup, Haseena says, “I read somewhere that pottery is the new yoga. It is like meditation. Your hands, eyes and mind are focused. It is a centring of oneself. You return to earth through the mud. It is through concentration that the pot comes into being. I want to spread the beauty of this art form all over the world.”

Published on February 16, 2020 22:25

February 14, 2020

Come to unspoilt Marari

The British-Russian couple, Rupert and Olga Evers have been running tourist villas at Marari Beach for the past ten years. Now they have just opened a new one called Frangipani

Pics: Rupert and Olga Evers. Photo by Arun Angela. Frangipani Villa

By Shevlin Sebastian

It was midnight on December 3, 2017. British-born Rupert Evers was in a villa on Marari Beach in Alleppey district. He stared through the windows and watched with trepidation as the waves rose nine feet and hit the shore with a ferocity he had not seen before.

Earlier, following cyclone Ockhi warnings, Rupert, with his workers had put up sandbags. Now the sea wall had collapsed, and the sandbags were flung aside as the water came rushing into the house. Within a matter of minutes, the verandah vanished. This was a tourist villa that Rupert was running successfully.

Anyway, he was undeterred. Rupert decided to rebuild the villa. This took a few months. But then on May 26, 2018, a storm took place. Again the verandah was taken away. This time Rupert closed it for good.

Rupert and his Russian wife Olga came to Kerala in September, 2008. They were looking for an ideal beach to start a business in tourism. They wandered all over the west coast of India but it was when they reached Marari they felt this was what they were looking for. “It was the quintessential tropical beach: white sands, palm trees and colourful fishing boats,” says Olga. “And unspoilt, too.”

But it was not easy doing business even though they had set up five beachfront villas. One major reason was soil erosion, apart from problems with the local unions. So they closed the villas down and began operating private pool villas further down the beach. Last month, they opened a new one called Frangipani Villa.

It is a luxury two-bedroom villa with a private garden and pool. “It’s called a serviced villa,” says Rupert. “You have the privacy of a holiday home but the service of a premier hotel. So, we have a butler, housekeeper, chef, caretaker and security. Kerala Tourism has recognised serviced villas as a category. There are yoga, cooking and kayaking classes.” Guests can wander into the nearby village to see the work of local artisans or go to the backwaters in kayaks or houseboats.

Most of the tourists come from the UK, France, Germany and Scandinavia. But over the past few years, domestic tourism has increased at Marari. There are guests from Chennai, Bangalore, Mumbai, Pune and Coimbatore, apart from families in Kochi.

And most tourists are happy with their experience. Wolfgang B says, “The staff is extremely friendly. There is the sun, sea, beach with palm trees and you -- just like in paradise.” Not surprisingly, the villas enjoy a 97% TripAdvisor rating and won its ‘Hall of Fame’ Awards.

“Kerala has a relaxed vibe and is much safer as compared to the rest of India,” says Olga. “But there has been a lot of negative coverage of India in the media abroad in the last few years because of violence and a lack of safety for women. As a result, Kerala has suffered, while Sri Lanka has gained.”

Meanwhile, when asked to enumerate the plus points of the Malayali, Rupert says, “They have a wonderful knack for hospitality. The Malayali is naturally warm and engaged, so tourists can see this warmth.”

And Rupert is happy to see the benefits of socialism in the state. “The quality health care, the good schooling, the high standard of education, and the fact that women are more equal to men compared to other states is very nice to see,” he says.

However, because they are running a business, the couple did face labour problems. “I fully support worker’s rights, fair wages, giving them leave, and good working hours,” says Rupert. “But we work with 90 percent locals, many of whom have not gone outside the state. So they do not have the exposure. We try to instill these standards to make sure our guests receive the best attention. There have been occasions when we have disciplined the staff and one or two have got upset and complained to their union.”

The union threatened to close down the establishments or block the guests from coming. “We suffered, but the courts and Labour Office supported us,” says Olga. “You travel along the highways and the number of derelict warehouses in Alleppey is so sad to see. It just does not make sense. Why do these unions take such a hard stance, that they are prepared to close down a business and deprive the people of employment rather than come to a compromise?”

Rupert adds, “Despite this, Kerala is a wonderful place to live, and our two children, a girl and a boy, are having a whale of a time.”

-----------------------------

The Indian connection

Through some fortuitous circumstances, Rupert Evers discovered that his great, great, great uncle, A.F. Sealy, was born in India. Later, he became the first principal of Maharaja's College in 1875 (one of the oldest in India). He also designed one of the main buildings, the 'Sealy Block' and was later appointed Director of Education for the district. After 27 years as Principal, he retired and was ordained as a minister of St Francis Church in Fort Kochi. Behind the pulpit, there is a memorial to Sealy. Incidentally, Rupert’s middle name is Sealy.

(Published in The New Indian Express, Kochi and Thiruvananthapuram)

Published on February 14, 2020 22:49

February 13, 2020

The village poet

MV Fabiyas, a little-known poet in North Kerala, has been nominated for the prestigious Pushcart Prize

Photos by Albin Mathew

By Shevlin Sebastian

‘We’re living In a pesticide era. Existence is in poison.

Peasants are persuaded.Their minds are mulchedWith chemical thoughts.

Vegetable gardens are gruesomeNot green, butA toxic shade of death dominates.

Even deep purple grapesIn the vineyards Don’t tempt birds.’

This is an extract from ‘Chemical Weapon’, a poem from the book, ‘Shelter within the Peanut Shells’. The book, a mix of poems and short stories, has been written by Malayali poet Fabiyas MV. An English teacher, who lives in Orumanayur village in Thrissur district, Kerala, the American magazine Poetry Nook has just nominated his work for the prestigious Pushcart Prize.

This little-known poet has been extensively published in journals in the USA, UK, Australia, Canada and Nepal. And what is even more surprising is that he has won several poetry awards. These include the PoetrySoup International Award, the Merseyside at War Poetry Award from John Moores University, Liverpool and the Animal Poetry prize from the Royal Society for Prevention of Cruelties against Animals. Fabiyas was also a finalist for the Global Poetry Prize.

In India, his poems have been broadcast on All India Radio.

But being nominated for the Pushcart Prize was the stunner. Frank Watson, the editor of Poetry Nook, says, “Fabiyas displays a unique insight into the human condition, often told through stories of the afflicted or forgotten. His perspective opens the reader’s eyes to deeper ways of looking at the world.”

Adds Roxana Nastase, Editor-in-Chief of Scarlet Leaf Review (Canada), “Although fantasy shimmers, the real world holds pain, blood and existential truths, and the pull of all of those is stronger than the dreamy quality of the imagination of Fabiyas.”

The poet’s subjects include autism, insanity, death, monsoons, elephants, midnight dreams, thieves, liquor, pregnancy, illiteracy and Ghulam’s ghazals. The other books he has published include ‘Kanoli Kaleidoscope’, ‘Monsoon Turbulence’, ‘Eternal Fragments’, and ‘Moonlight and Solitude’.

The biggest influence in the life of Fabiyas has been his late father MV Alikutty. He was a well-known writer in Malayalam who has published more than 20 novels, travelogues and memoirs.

“From my childhood, my father would tell stories to me,” says Fabiyas. “I was in Class 7 when I wrote my first poem. When I showed it to him, he was very happy. He told all his friends that I had written a poem. It was he who told me to continue writing. I still remember that moment so clearly. He has always inspired me.”

And his village also inspires him. He stays near the Canoli Canal, which was built by the British in 1848. He has lived on its banks since his childhood. “The canal serves as an inspiration, so do the people around me,” says Fabiyas.

However, in a village where there is a low awareness regarding literature, many did not know he is a poet. It all became clear to them when an article about Fabiyas was published in the local Malayalam newspaper.

But Fabiyas is not deterred by the lack of poetry fans in the village. “Outside India, there are thousands who consider poetry as their lifeblood,” he says. “The US-based PoetrySoup group has 25,000 members. All of them have a passion for poetry.”

Nevertheless, there is a feeling that reading has gone down. Fabiyas shakes his head and says, “I don’t think so. The platform has only changed: from print to digital.”

Most mornings, Fabiyas, a father of two teenage girls, gets up early and sits at his desk. When he picks up his pen, he says the lines come out in a flow, like a river. “Many times, editors told me my language is apt for poetry,” he says. “When I write fiction, readers have told me it reads like poetry. I need a lot of time to complete my fiction. But poetry only takes about two hours.”

Thus far, he has published 200 poems. Whatever money he earns from his writing, he uses it for the welfare of orphans.

Finally, when asked about his favourite poet, Fabiyas says, “It is the British poet William Wordsworth (1770-1850) who is known for his poems on nature. “But I like his spirituality poems like ‘Intimations of Immortality’,” he says.

Published on February 13, 2020 22:54

February 7, 2020

Doing her best

77-year-old Snehlata Gulia Hooda won four gold medals at the 40th National Masters Athletics Championships held in Kozhikode recently. The Delhi-based athlete talks about her earlier visits to Kerala as a student athlete as well as the classes that she conducts for poor children

Photo by Manu Mavelil

By Shevlin Sebastian

At the Calicut Medical College Stadium recently, there is a sparse crowd even though the 40th National Masters Athletics Championships is taking place. Inside a white circle stands 77-year-old Snehlata Gulia Hooda. She is wearing a blue T-shirt with the number 7507 in striking red against a white background, along with white slacks and shoes. On her head, there is a white cap. To shield herself from the heat, Snehlata is wearing sunglasses.

She juggles the shot put in her hand. Then when she gets the go-ahead, she steps forward and throws the put in a smooth action. Unlike most shot putters, she does not place the put under her chin or do a half-turn, to gain more momentum. But she wins the gold easily.

In the end, Snehlata also wins golds in the javelin, discus and the 400m. Six months ago, she underwent an angioplasty. “The cardiologist did not tell me whether it was alright to restart my athletic career,” she says. “But I decided to go ahead.”

So, she came to Kozhikode. And this is not the first time she is coming to Kerala. She remembers coming to Thiruvananthapuram as a student of Class 8 to take part in a state kho-kho competition as the captain of the Punjab team. “I still remember the roof of the small stadium was made of thatched coconut leaves,” she says.

Of course, she likes Kerala a lot. “I like the cleanliness,” she says. “The people are well-mannered. Nature is all around. But nowadays it has become so hot that I am unable to bear it. Unlike Delhi, where I stay, Kerala has no winter.”

But there is a perpetual summer in Snehlata’s athletics career. Wherever she participates in India, she wins medals. She has also taken part in international competitions in Auckland and Jakarta. “In Jakarta, I won three golds and a silver,” says Snehlatha.

Snehalatha worked for 40 years as a Trained Graduate Teacher of the Delhi state government. When she retired in August 2003, she decided to help the downtrodden. So, she started a school called Gaurav Niketan for the children of domestic workers and daily-wage earners on a footpath in Gurugram.

“I have 150 students,” she says. “Earlier, there were 300 students, but because of demonetisation all these children and their parents have gone back to the villages because there is no work available.” Incidentally, the children call her Gaurav Ki Maa.

The students range in age from four to 15 years. In winter, the classes are from 9.30 to 2.30 pm, while in summer, the time is from 8 am to 1 p.m. “The parents realised I am sincere because even when it rained I carried on teaching,” she says.

This feisty woman is a mother of seven children: five daughters and two sons. Tragically, one son died in a car accident, when he was only 28 years old. Her husband also passed away a few years ago because of a brain haemorrhage.

“There is sadness in life but I get fulfilment in helping the poor,” she says. “And I am spending my retirement years in the best possible way.”

(The New Indian Express, Kochi and Thiruvanthapuram)

Published on February 07, 2020 22:40

February 5, 2020

How to heal oneself

Many people suffer from emotional pain. Nutritionist V. Gayathri offers solutions in her new book

Pics: V. Gayathri; the cover of the book

By Shevlin Sebastian

At age 12, Shani was married off to an elderly man. But after a few years, he divorced her. She felt shocked. She remained inside her house for a few years. Feeling emotionally hurt, and angry with her parents for allowing this marriage to take place, she started eating. And eating, Soon, she ballooned and reached 90 kgs.

Through a friend, she met the Kochi-based nutritionist/dietician V. Gayathri. “As she spoke about her experiences, over a period of time, she was able to forgive her parents and her former husband,” says Gayathri. “Her skin tone and energy levels started improving rapidly and her hormones began to function normally.” Shani began losing weight. She resumed her studies, and eventually got a degree. Later, she got a job. And it was at the workplace that she met Ramesh. They fell in love and got married, even though they belonged to different religions. “Now they are happy,” says Gayathri.

Gayathri has just published a book called ‘Diet and Meditation for emotional eating’. Some of the topics include ‘Inner Child and Emotions’; ‘Food, Nutrition and Energy’, Sexual/emotional abuse -- the reason for obesity’ and ‘Diet and emotions during school’. “The trigger for almost every ailment, physical or mental, lies in our childhood,” says Gayathri. “In our society, we are not encouraged to express our innermost feelings so that others don’t experience discomfort. So we suppress all those unexpressed emotions within ourselves.”

She gives an example. Mona, a daughter of a working woman was sexually abused by a neighbour. But when she told her parents they did not believe what she said and supported the neighbour. “Mona was deeply hurt,” says Gayathri. “This pain has now resulted in an unhealthy relationship with her spouse. Later, even after prolonged fights with her husband, her family refused to take her back. She remains stranded in this toxic environment.”

Gayathri suggests that writing about the traumatic incidents in one’s life can help healing to take place. “After you write something, you should burn the paper, as a symbolic way of cleaning yourself,” she says. Another way is to smile often. “It is one of the most powerful triggers of positive energy,” says Gayathri. “You should also learn to love yourself. And do meditation, too.”

Another important quality is gratitude. Or as the poet, Rumi wrote, ‘Gratitude is the wine for the soul. Go and get drunk.’

Gayathri tells her clients to maintain a gratitude journal. “An attitude of gratitude can change your life,” says Gayathri. “When you start the day writing a few lines of gratitude, your vibration changes and it helps your subconscious mind to seek out more of those positive things around you.”

You can do this at night too. “You can end the day with an appreciative thank-you for everything that Nature has offered you that day and life as a whole,” says Gayathri. “Initially, you will struggle to name 3-4 things but when you start doing it daily, the list will grow longer. You can then sleep with a positive frequency of thoughts and emotions, which will embed in your subconscious during your sleep. Soon, you will start waking up with new energy and enthusiasm.”

And when a single person is transformed, he or she can impact his immediate family and friends. They further share this with others until a community of love is built up. “Each one of us should remember that human potential and energy are limitless,” she says.

(The New Indian Express, Kochi)

Published on February 05, 2020 23:43

February 3, 2020

Travels on a truck

Louise France and Nick Fulford have been driving a massive truck/bus with 18 international passengers from Kathmandu all over India. At Kochi, during a brief stopover, they spoke about their experiences

Pics: Nick Fulford and Louise France; the Daisy truck

By Shevlin Sebastian

A few days ago, Louise France was behind the wheel of the truck/bus called Daisy on Highway No 66 as they were nearing Kochi. Inside were 18 travellers from countries as diverse as Australia, UK, America, Switzerland, Portugal, and France. A minivan sped past. The driver’s mouth fell open when he saw that it was Louise at the wheel. He stuck his head and began waving at her.

There was a car in front which was slowing down. Louis gestured to the driver to slow down but he didn’t seem to understand. At the last moment, the driver turned his head, and saw that he was about to hit the car So, he braked hard, the van skidded but thankfully came to a stop without hitting the other vehicle. And as Louise went past he kept waving at her.

At a hotel, near the Law College hostel in Kochi, Louise breaks out into a wide smile. “It was a close shave,” she says. Nodding slightly is her fellow driver Nick Fulford.

While Nick also doubles up as a mechanic, Louise is the team leader. But what catches the eye is the truck. The height seems to reach the first floor of a house. “There is space for 24 passengers,” she says. “Behind the seats are two tables where people can sit around and read newspapers or play cards. There is a refrigerator as well as a library. Passengers can move around a bit. But we have no toilet facilities.”

Under the truck, there is a water storage tank which can carry 200 litres. Many times, they go off the beaten track, and set up tents and stay there. At night, they have a campfire. “We usually do this in deserted areas,” says Nick.

Their journey began on December 8 from Kathmandu. They spent two weeks travelling around Nepal. Then in India, they went to Varanasi, Khajuraho, Agra, Jaipur and Delhi. Thereafter, they went to Mumbai, Goa, Hampi in Karnataka and entered Kerala at Wayanad. While there the group did a tour of a tea plantation. Thereafter, they stayed at a homestay in a village for two nights.

Louise says that for travellers, every state offers something different. “That is the beauty of India, its diversity, the way the climate changes from place to place, the different types of food and clothes,” she says.

Meanwhile, Nick has no time to appreciate the diversity as he has to be in full focus when he is behind the wheel. “Unlike in Europe, there is a lot of traffic and vehicles that we are not used to, like tuk-tuks (autorickshaws), carts, pedestrians, cows and dogs,” says Nick. “A lot of things are happening on the road all the time. You cannot afford to lose concentration.”

Both Louise and Nick are working for the UK-based travel company called ‘Dragoman’. When asked the meaning, Nick says, “It is an Arabic word for guide. They guided people on the ancient Silk Route (which connected India and China with Europe) especially through the deserts.”

The company began in 1981 and has managed to stay relevant by evolving according to the times. While the earlier trips were long, for instance, from London to Kathmandu, and people stayed in tents and enjoyed a campfire, today, the duration is much shorter, and the travellers prefer to stay in air-conditioned hotels and lodges.

As for some of the lessons they learned from the trip, so far, Louise says, “We in the west we take many things for granted,” she says. “We have a life quite easy and are blessed. We see people working hard and not making as much money but they are happy with whatever they have got. They seem to be loving life. I understood that you don’t need too many things to make you happy. Happiness is within.”

She says that the West has gone wrong by becoming too materialistic. “But I also fear that Indians, with rising incomes, may be going the same way,” says Louise.

As for Nick, he has learned to be patient. “On the road, that is the only way you can drive,” he says. “Many people want to help when you have a problem, but sometimes, they lack the skills. So I have learned to be calm.”

But what they both enjoy is the energy on the streets. It is very palpable to see. In Europe, this energy is rarely seen, as work takes place inside buildings or factories and rarely on the streets. “Overall, it has been a unique experience, so far,” says Louise, as they head towards Alleppey, Varkala and then on to Kanyakumari.

(The New Indian Express, Kochi and Thiruvananthapuram)

Published on February 03, 2020 22:12

January 31, 2020

The fight goes on and on….

On a recent visit to Kochi, Bezwada Wilson, who won the Magsaysay Award for his work on behalf of scavengers, talks about the relentless battle to stop the practice

Pics: Bezwada Wilson; cleaning drains

By Shevlin Sebastian

Seven-year-old Bezwada Wilson was running through the centre of the field. The winger gave a pass to him and he kicked the ball hard. It sped past the goalkeeper into the net. As he raised his hands in joy, the boys shouted, ‘Thoti has scored a goal.” Then they all laughed at Wilson. At his home in the Kolar Goldfields in Karnataka, he asked his parents about the meaning of the word. They waved their hands and said, “It is not important. Just forget about it.”

But Wilson couldn’t. It was only later that he came to know the word meant scavenger. It shattered him when he realised his parents were scavengers and he belonged to a Scheduled Caste community whose members have been scavengers for decades. “I developed an inferiority complex,” says Wilson. “I realised I am not like others.”

Wilson had come to Kochi recently to give a talk at the Kerala High Court titled, ‘Manual Scavenging and the law: challenges in the implementation of the law’.

It was in Class 12 that he decided to devote his life to stopping this practice. And in 1993, along with an IAS officer, SR Shankaran, Wilson set up the NGO, Safai Karmachari Andolan (SKA). “I felt bad that many people had accepted their fate meekly,” he says. “I tell the volunteers to instil a fighting spirit.”

So what does the job of scavenging entail? In many states of North India, like Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Bihar, Gujarat, Rajasthan and Jammu and Kashmir, they have dry latrines. People just defecate on to a bucket. The scavenger has to go to the side of the house, pull the bucket out, transfer the waste to another bucket and take it to the outskirts of the town or city and dispose of it. But they are paid as low as Rs 30 per month from every house. If the scavenger puts a plate nearby, the people throw chappatis on it.

In South India, they are mostly involved in the cleaning of waste from sewage drains. They go into roadside drains but because of certain gases which they inhale, they die. “They don’t wear any protective gear,” says Wilson, who is a Senior Fellow at the Ashoka Foundation. “This type of work is highest in Tamil Nadu, while in Kerala, it is much less. The scavengers feel they are living in a rotten society and there is little scope of getting freedom from this type of work.”

Wilson’s life changed when he won the 2016 Ramon Magsaysay Award. A part of the citation states: ‘Bezwada Wilson has spent 32 years on his crusade, leading not only with a sense of moral outrage but also with remarkable skills in mass organising, and working within India’s complex legal system. The SKA has grown into a network of 7,000 members in 500 districts across the country. Of the estimated 600,000 scavengers in India, SKA has liberated around 300,000.’

In his reply at the awards ceremony, Wilson said, “Sadly, this form of oppression, equivalent to slavery, continues in modern India. My tears of joy are mixed with tears of grief and regret -- thousands of my people have died and are dying in the soak pits. Millions more have succumbed to incurable diseases; their kith and kin live in squalor, with little or no opportunities to improve their lives. But my people have also demonstrated their power of resilience.”

After the win, society’s attitude changed. People started realising that scavenging is a big problem and there is a need to show solidarity. So, if Wilson calls a meeting a lot of people who are not scavengers will come and offer support. “They have become more aware of what is happening.” he says. “And the authorities have started looking into the issue. But mostly, they are in denial mode, despite showing photos and videos.”

On January 9, officials of the central ministry of social justice at the centre sent some data, given by Wilson, to the state governments in North India. But the officials in UP and Bihar said there were no dry latrines anywhere in their states.

“Of course, this is not true. So, we are facing an uphill battle,” says Wilson. “But we have to carry on fighting. We cannot give up.”

(The New Indian Express, Kochi)

Published on January 31, 2020 23:27

January 30, 2020

Questions at a funeral

By Shevlin Sebastian

Five years ago, when Rita Thomas died, at the age of 82, it was her daughter-in-law, Liza who rushed about ensuring that there was a scarf on the head, the saree was white and crisp, and the socks were placed properly on the feet. She also ensured that her mother-in-law clasped a small wooden crucifix in her gloved hands.

The body was placed in an air-conditioned coffin at their home at Kochi. People trooped into the living room. Prayers were said; a few shed tears; there was the singing of a hymn. Later, a priest, wearing a white cassock, said a prayer in a sombre voice. A widow, Rita had seven children: three boys and four girls. Now they had all married and the family had grown large. But Rita lived with her son James, Liza and their two children.

On January 20, this year, another body was placed in the living room. This time, to the shock of many, it was Liza who was in the coffin. A victim of cancer, her last few months had been painful and hard. Now, at 58, God had taken her. Her two children, a boy and a girl, both married, were bereft. Liza’s eight-year-old granddaughter, Anna was deeply affected. To console her, James said, “Ammama is sleeping.” Anna shook her head and said, “No, she is gone.” James nodded and said, “Permanently.” And the word hung in the air.

As Liza was lowered into the grave, one could not help but wonder: where do the dead go? How far away is the place where spirits reside? Could it be ten or 100 million kilometres away? How long does it take to reach there? Is it in the blink of an eye? And without a body, are the dead like morning mist? Will they be able to recognise their relatives, friends and...why not… enemies? How do they talk without a tongue?

And how do they pass the time, without the preoccupations of work, books, films, music, art, and stimulating conversations with friends in coffee shops? Without a body, how can a man appreciate the beauty of a woman? Does flirting take place? And what about the bad people of history like the dictators Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin? Can the good see the bad? Or do they go to a different place, like, maybe, a black hole?

All these questions swirled around in the mind, as the coffin containing Liza was laid to rest in the six-feet deep hole. Soon, two gravediggers, using spades, began shovelling mud onto the coffin…

(Published as a middle in New Indian Express, South Indian editions)

Published on January 30, 2020 21:17