Shevlin Sebastian's Blog

November 21, 2025

The marker's son who became a national tennis coach

Maharani Gayatri Devi of Jaipur

Maharani Gayatri Devi of JaipurCOLUMN: Tunnel of Time

From very humble beginnings, Akhtar Ali rose to become a tennis player who played at Wimbledon and was a member of the Indian Davis Cup team. He was also a distinguished coach of the Indian team for 20 years and, in the course of his three-decade coaching career, produced several national men’s and women’s champions, including his own son Zeeshan.

By Shevlin Sebastian

The appointment with Akhtar Ali had been fixed at 4 p.m. on a Wednesday afternoon in November at his flat on Dilkusha Street in Calcutta. I arrived on the dot and rang the bell. Ali’s daughter, nine-year-old Zarine, opened the door and asked whom I wanted to meet. I mentioned her father’s name. She went inside to tell him, then returned to ask my name. She went in again, came back, and asked where I had come from. I replied, and she went in once more. When she returned yet again, she had a welcoming smile on her face (had this girl already become media-savvy?). So I stepped inside.

A few feet away from the door, Akhtar Ali stood barefoot in the drawing room, hands on his hips but with a welcoming smile on his face. I wondered to myself why he hadn’t come to the door.

It was a well-appointed flat, tastefully decorated. A wooden cabinet against one wall contained several trophies, all won by his son Zeeshan. There was an A/C in one window, small tube lights embedded in the false ceiling, and a soft carpet on the floor.

We sat on the sofa, and after a couple of minutes spent discussing the result of the last one-day match between India and New Zealand in Bombay, which India had won, I detailed the topics I wanted him to speak about. Akhtar Ali was launched. And when I say launched, you had to take it literally — like a plane going up into the sky.

Once he started talking, he was in non-stop mode.

His English was fluent, the sentences rolled out of him easily and confidently, and he had a garrulousness that made Javed Jaffrey seem as if he were suffering from laryngitis.

Undoubtedly, this man had energy, enthusiasm and a still youthful intensity.

Here are excerpts from the four-hour interview.

On his early life

I was born in 1939 at Allahabad. At that time, my grandfather had a coal business there. Then one day, my father came on a visit to Calcutta and he liked the place. Luckily, he had a friend who worked at the Saturday Club, and this friend managed to get him a job as a squash marker. So it was as a marker that my father began to make a living.

I was born in Allahabad, because my mother still lived there with my grandfather, but we used to come to Calcutta on holidays. I was ten years old when we moved permanently to Calcutta.

I started playing squash at the Saturday Club. I picked up the game quickly and became a very good player. But when I was about 13, there was a complaint among the players that I should not be allowed to play.

Firstly, because I was the son of a marker, and secondly because I was beating a lot of older, more experienced players.

So what did you do?

Nothing much. I just hung around. In squash, you can play alone and still have a good time. But one day, I remember it was during the Puja holidays, I went to the Barrackpore Club, where my uncle, Syed Ali, was a tennis marker. There was a Merchants’ Cup tennis competition. I took part and did well.

At the age of 15, I played in the Bengal Lawn Tennis Championships. I won the tournament by defeating the No. 1 seed, Dennis Ford. That’s when I started to think seriously about playing tennis. Next, I played the junior national championships and once again reached the final. But despite these performances, I experienced a lot of difficulties from the very beginning.

What sort of difficulties?

Tennis, in those days, was played by people of high society, and they could not tolerate the fact that a marker’s son was playing alongside them. High society always felt that they were very superior. So, as a result, they always looked down on me.

When people looked down on you, did you feel an inferiority complex?

No, surprisingly, I have never suffered from an inferiority complex just because I was a marker’s son. I always told myself, Upar Allah, neeche ballah.

What does ballah mean?

Ballah means racket. That means: forget your background and speak with your racket. If you are rich, you are rich. That’s okay with me. But come to the tennis court and I will show you.

What other obstacles did you face?

In 1955, when I was going to play the junior nationals, there were objections once again. People said that since I was the son of a marker, I was a professional player. When that argument did not work, they said I had to show a birth certificate to prove that I was below 18. But I didn’t have one.

So I got a certificate from the Islamia School where I was studying, but the tennis association did not accept it. The deadline was approaching.

On the day before the Championships began, the officials said that if I didn’t produce the certificate by 6 p.m., I would be disqualified. Both my father and I did not know what to do.

Then a European at the Saturday Club came up with the solution. He asked my father whether he had a marriage certificate. My father said yes. So we went with the marriage certificate and showed it to the officials.

Sir William Mitchell Moore, the President at that time, saw that my parents had been married for 16 years, so as the eldest child I had to be below 18. He allowed me to play. I reached the final, defeated Pakistan No. 1 Rahim, and became the champion.

Then what happened?

As a junior national champion, I started to play in the All-India circuit, travelling from place to place. Then I went to Jaipur, to play a very big tournament there and I won once again. The Maharani Gayatri Devi of Jaipur asked me whether I was planning to go and play junior Wimbledon, since I was the national junior champion.

I said that I didn’t have the money to go to Wimbledon. So she asked the secretary of the All-India Lawn Tennis Association whether he was planning to send me. He replied that the association did not have any funds. So, at a party after the Championships, the Maharani announced that her husband and she were going to take me to Wimbledon, all expenses paid.

So, in 1955, I went to Wimbledon for the first time. How was the experience? It was unforgettable. This was the first time that I was going abroad, so everything was new and fantastic to me.

Before Wimbledon, I played two tournaments and won and so I was feeling very confident. But a day before the Championships was to start, a funny thing happened to me. What was that? I got a telegram from India saying that my father had died. I started crying like hell. Then, through an acquaintance, we rang up the Saturday Club to find out more details. We found out that there was nothing wrong with my father. In fact, my acquaintance spoke to my father on the phone.

Who do you think sent the telegram?

Obviously, it was somebody who did not like me and who did not want me to do well.

But you never found out who sent it?

How to find out, you tell me. If somebody sends a telegram with no name, then how can I get the name?

So what is your analysis?

I was playing junior Wimbledon. There were some people who were hoping I would get upset and do badly. Maybe, it was because of jealousy.

Do you think people disliked you because you are a Muslim?

(A short pause): There was a lot of communal feeling at that time. After all, Partition had happened a few years ago. Yes, some people were even saying about me, Saala Mussalmaan hai. But I think they were very much in the minority. People like Gayatri Devi and later, Premjit Lal, Jaideep Mukherjee, Naresh Kumar and Ramanathan Krishnan never ever looked at me in a communal manner.

Would the same communal thing happen today in Indian tennis?

Of course, it has become much worse now.

Is it all because of the politics of the BJP?

No, I wouldn’t blame the BJP for everything. I think it is more to make a tamasha out of the whole thing. Our biggest problem in India is that we don’t look at people as Indians, but we are always categorising them…

Coming back to junior Wimbledon ’55, how did you perform?

I reached the semi finals and was leading 5-2, 30-15 in the third set. But I ended up losing the match to Lundqvist of Sweden. I started crying because I felt that I would never be able to play at Wimbledon ever again. But the Maharaja and the Maharani consoled me and said that if I did well, they would send me again the next year. And since I had reached the semi finals, I was eligible to play next year.

Just out of curiosity: how much was your father’s income as a marker?

Those days, he used to earn Rs 110 a month.

Apart from tips?

No, there was no question of tips. The club charged Rs 10 for playing and the marker got Rs 5. The rest went to the club.

Your father was earning decently, so you weren’t in financial difficulty?

No, I am grateful to God that I was not.

His father’s death

When was that?

In 1959, my father suffered a brain haemorrhage. The Nationals were about to begin. My match was scheduled for Monday at 11 a.m. But in the early hours of Monday morning, my father died. I went to the South Club and asked them to postpone my match. They refused. Some people ensured this, because they felt that if I didn’t play, I would lose ranking and not be considered for the Davis Cup team. Finally, with great difficulty, I got my match postponed to 3 p.m., instead of the morning session.

We buried my father, and I returned home at 2 p.m. I took a bath and quietly picked up my racket. My family got very angry. My uncle slapped me and said, “You’ve just lost your father and you want to play the Nationals?”

I replied, “Look, I lost my father. He is not going to come back. But if I don’t play in the Nationals, my future will be spoiled.”

Looking back, do you think it was the right thing to do?

Yes, otherwise I would have lost a year.

But wasn’t it a tragedy?

Yes, but my tennis career was at stake. My enemies were looking for every opportunity to keep me down. If I didn’t play, it would have been a victory for them. After that, I realised I needed to earn. I was the eldest, with sisters to marry and brothers to support. I was offered jobs in coaching and at the Saturday Club. But I refused. If I took those jobs, my career would be over. So I supported my family by playing tournaments. Krishnan got Rs 1000 to play; I got Rs 400–500 plus board and lodging. Then I started doing coaching for the rich in Calcutta and earned Rs 1000 a month.

On his career

In 1956 I qualified for men’s singles at Wimbledon and lost in the second round.

’58: Lost in the first round at Wimbledon.

’59: Lost in the second round.

’61: Lost in the second round;

lost to Rod Laver in the French Open.

’62: Lost in the first round.

Member of the Indian Davis Cup team from 1958–64. Played in Monte Carlo, Japan, Iran, Malaysia, Thailand, Pakistan and Mexico.

Akhtar Ali defeated players like John Newcombe, Alex Metreveli, Tony Pickard, Jaideep Mukherjee, and Premjit Lal.

He won several state and national titles. He was also the National squash champion in 1968.

How would you rate yourself as a player?

I was never a big player. I made it through sheer hard work. Better players like Premjit and Jaideep came up, so I focussed on coaching.

On his coaching

Australian player George Worthington taught me fundamentals: backswing, follow-through, positioning, volleys. Nobody had taught me this earlier. As a coach, I produced national champions like Gaurav Mishra, Bidyut Goswami, Susan Das, Reena Eeny, Susan Sinclair Jones, Chiradeep Mukherjee, Rico Piperno, and my son Zeeshan Ali (World No. 2 in juniors; No. 125 ATP).

I coached Vijay Amritraj for four years and was Davis Cup coach for over 20 years, including when India reached the final in 1974.

[Australian coach] Harry Hopman told me I had a good ‘eye’ and could spot weaknesses quickly.

Who is the best coach you have met?

Harry Hopman. He could turn promising players into champions. I remember in 1956, Laver lost 6-0, 6-0, and I laughed when Hopman said Laver would be a great player. Obviously, Hopman was right.

What is talent?

Talent is God-gifted. Someone like John McEnroe has it. But talent alone cannot make a champion. You need hard work and a good coach from the very beginning.

Do Indian coaches have technical knowledge?

No. Our coaches are never sent abroad to learn the latest methods. So we have different types of coaches. Some very good Under-12, Under-14 coaches. But they cannot develop a player to world standards. I myself could only take Zeeshan to No. 125. After that he needed a foreign coach.

On Zeeshan Ali

People say you concentrated only on Zeeshan. True?

Yes, I did concentrate on him. Every father helps his own son. Krishnan helped his son. Vijay Amritraj helped his brothers. Why should people talk when I help my son? At that time, I was a free agent. I wasn’t employed by anyone.

Did Zeeshan have talent?

Yes. But I wanted an expert opinion, so I asked my friend Krishnan. He watched Zeeshan and said he had wonderful talent.

But did Zeeshan have fire?

He was hungry, but not as hungry as I hoped. He had an easy life. It’s difficult to develop inner fire if life is easy.

What happened later?

He suffered a leg injury in 1989. He got injury problems, became depressed, lost motivation, felt the pressure of spending his father’s money. We were finding it hard to get sponsors. Many times he tried to give up. The pressure of not being picked for Hopman’s camp affected him.

A bit of hardship fuels the inner fire, doesn’t it?

Absolutely. A hungry sportsman is the best sportsman.

Do you have sorrow about what happened?

Yes.

What is Zeeshan doing now?

He is playing inter-club tournaments in Dubai.

On Drugs

Are players taking drugs?

Yes, many take drugs for recovery. If a player has a tough match, they take pills to help the body recover. This is necessary because of modern training loads.

It is four p.m. on a Wednesday in December at the South Club. Akhtar Ali is teaching very young students. They stare at him as he makes playing movements with his racket. I could not help but feel sympathy. A man with so much coaching experience, national coach, and personal coach of Vijay Amritraj, is now reduced to teaching rich novices.

Akhtar Ali’s present situation proves a singular point: the under-utilisation of worthwhile people in our country is a national disease.

He tells an anecdote: “In 1961, India was playing Pakistan in a Davis Cup match in Pune. As I was leaving the court, a mali [gardener] gave me a note: ‘Dear Akhtar, I would like to meet you. Come to my place. The address is… Yours sincerely, Sally.’ Naturally, I got excited.

I changed into fresh clothes and went to the address. It was the home of a Sardarji who recognised me and welcomed me in. We talked for half an hour. Then I asked, ‘Where is Sally?’ The Sardarji looked at me and said, ‘Mr Ali, I don’t know what you’re talking about.’

I realised Jaideep had written the letter and changed the name to tease me. So I kept the note, changed the name back, and sent it to a Pakistani player. The fool landed up at the Sardarji’s place asking for Sally…”

(Published in Sportsworld, January 3, 1996)

(Akhtar Ali died on February 7, 2021, aged 81)

November 13, 2025

The journey to the interior

Photos: The Songshan Shaolin Temple in China; Lord Buddha in Shaolin Temple Europe

Photos: The Songshan Shaolin Temple in China; Lord Buddha in Shaolin Temple EuropeShaolin master Shi Heng Yi shows us how to better understandourselves

By Shevlin Sebastian

Very early in the book ‘Shaolin Spirit — The Way toSelf-Mastery,’ by Shi Heng Yi, the author states, ‘It is the moment thatmatters. It is living in the present and being aware of what is, here and now —because the Now is when life is happening, and only in the Now can change takeplace.’

He also talks about how important it is to focus on thebreath. In Shaolin, this system of focusing on the breath is called Qigong.‘You can go a few days without food, and even without water, but you can onlylast a few minutes without breath,’ says Shi. ‘When you focus on the breath, itenables you to strip away illusions and see the world as it is.’

The Shaolin philosophy was founded over 1,500 years ago atthe Songshan Shaolin Temple, located at the foot of the Shaoshi Mountain inDengfeng City, Henan Province, China. The temple is now a UNESCO World HeritageSite.

The philosophy focuses on martial arts and meditation,addressing the needs of the mind and the body.

Author Shi acknowledges that what the world thinks of Shaolinis probably true. Adherents can do head-high standing jumps, can shatter aglass pane with an accurate throw of a needle, and have lightning-quickreflexes. But to do this, there are years of practice and discipline that arerequired.

Shi says that to change, you must ‘come face to face withyourself, plumbing your own depths, recognising your limits, and understandingthat only you can push past them if you want to grow. It requires intenseeffort and energy, as well as the willingness to welcome pain when those limitsbegin to shift and open.’

In a shaded text, there is a question:

Who are you?

Shi writes: ‘Take a moment to gaze deeply into your past.Look at the way you have developed and ask yourself: What has shaped me in thepast? What has moulded me into what I am today? Are there things from your pastthat may still linger, things you aren’t aware of? Have you repressed them, ordid you simply never take the time to really examine what happened to you?’

These are thought-provoking and life-changing questions.Honest answers to them might lead to a deeper perception of how you turned outthe way you did.

Here are some wise thoughts to ponder:

‘Everything in life will one day reach its peak and thendwindle into nothing.’

‘Your mindset determines success or failure. It is essentialto be conscious of it, because it can be powerful and dynamic or devastatingand dark. Your mindset determines your thoughts, and thus how you see the world— which in turn affects how the world reacts to you.’

Shi says that it is important that one becomes aware of one’sopinions and thoughts.

He adds that we should ask questions like: Is this reallyyour point of view? Did you come up with it yourself? Or did you adopt thisopinion from somewhere else? If yes, how long ago? Is it relevant enough to youand your current life that you should continue to carry it within you?

Honest answers to these questions will enable one to changethe course of one’s life. But he says it is important to keep asking thesequestions again and again, only then will the truths about the basis of youropinions emerge. Once you are aware, then there is a possibility of changingyour mindset, and setting off on a path that is unique, exciting, andsuccessful.

The key is to observe without judgement so that you are nothampered by buried emotions or wishful thinking. That is when we can get aclear picture of the truth. Shi writes: ‘The more sensitive your mind, the moredetailed your perceptions, the higher the quality of your insights.’

Shi says that when somebody is on the path toself-improvement, he or she will face five hindrances. They include sensorydesire; hostility or resentment; mental or physical torpor; restlessness,scepticism, and indecision. The way to overcome them is to be aware of thefeelings they create inside you and then try to work your way aroundthem.

One of the ways to heal yourself is to let go — of anger,resentment, frustrations, disappointments, beliefs, expectations, anddeep-seated attitudes. It should be like removing the furniture and other itemsstored in a basement. Shi says that you will be surprised by how light-heartedyou will feel. It is not a simple task, but Shi shows you physical exercisesthat will, over time, help you reach an empty basement in yourmind.

Shi insists that the mind should be assertive. ‘Ask yourselfwhat freedom means to you?’ he says. ‘Does it mean following yourimpulses or mastering your impulses? Only when you have disciplined yourmind does true freedom begin.’

He also says that it is important to self-observe. ‘This is afundamental aspect of the Shaolin spirit,’ he says. ‘How deeply can you lookinto yourself? How well can you see yourself? How honest are you with yourself?Can you see the truth free of other people’s expectations and your own desires,perceiving what is present in the moment?’

Here’s a bit about the author: Shi’s mother escaped fromVietnam, crossed the border, and reached Bangkok with little money. Theauthorities jailed her many times because she could not pay for necessities.She eventually ended up at a UNICEF camp. While there, she received a marriageproposal from a man who had been her neighbour in Vietnam. Shi’s motheraccepted, and they got married. They received asylum in Germany. The couplesettled in Kaiserslautern, near Otterberg.

Shi was born in Germany in 1983. When he was four years old,he received training in Shaolin from Grandmaster Kwan Chun. Today, Shi runs theShaolin Temple Europe, based in Otterberg. He teaches physical and mentaldisciplines, Qi Gong and Chan Buddhism.

This is a book that makes you aware of how mechanically welive our lives. Almost like a machine, we go full tilt each day, living mostlyon the outside, unable to understand the roots of our behaviour, unaware of thereasons behind our addictions and compulsive behaviour, and not fully aware ofour mindset.

Through the book, Shi invites us to go on a journey within,to better understand ourselves, to look at the darkness inside, and try not toflinch. The more aware we become, the more sunshine will light up the darkcorners and heal our psyches. Eventually, Shi promises you will reach a stateof nirvana, free from earthly bondage.

(Published in kitaab.org)

November 6, 2025

MAHARAJ! Sourav Ganguly, the pride of Bengal, up close and personal

When this article first appeared in Sportsworld in August 1996, Sourav Ganguly had just returned from England, having scored two centuries on debut. The country was in rapture. Bengal, in particular, had crowned him its new prince. Yet, behind the applause, there was scepticism: whispers of arrogance, privilege, and family influence.

Reading this piece again after nearly three decades, it feels like a time capsule, not just of Sourav Ganguly, but of an India still learning to handle fame, money, and media glare. The cricketers then were not yet brands. Their homes were open, their families accessible, and their lives unfiltered. What you’ll read below is a portrait of a star being born in real time, before the myth took over.

(These two paras above generated by AI)

By Shevlin Sebastian

I arrived at Sourav Ganguly’s house in Calcutta at 11.15 a.m. on a public holiday. I knock on the gate. The durwan opens it. I mentioned that I want to see Sourav Ganguly. He says immediately that he is not at home. I am surprised. I say that I am from the press. I have an interview with him at 11.30 a.m. The durwan says, “Wait a minute.” He goes into a small room on one side. He picks up the receiver on the intercom.

I look around. There are three blocks of buildings, all seemingly joined together. The buildings have been painted a bright red. The outer walls of the house have also been painted in the same bright red.

The durwan comes out and silently takes me down a cement path. “It’s the flat on the first floor,” he says. I go up the stairs. I ring the bell. The door opens. A man tells me to come in. I go in and sit down on the sofa. There are a couple of men hanging around; they look like family retainers. A young, attractive-looking woman walks past and goes into the dining room. The phone is ringing incessantly; nobody is picking it up. The drawing room faces the balcony. Minutes pass. I stare at the pale blue sky.

The doorbell rings again. The young woman opens it. A middle-aged woman with two young boys stands at the door. The young woman says, “Yes, who are you?”

The woman begins confidently. “Don’t you recognise me? I am your uncle’s…” A lengthy description follows.

The woman does not believe it. She says in a flat voice, “No, I can’t recognise you.” The other woman’s face falls. The corners of her mouth twitch in exasperation. Snehasish’s wife now looks at the boys and asks sternly, “Where are you from?” The boys are silent.

At this moment, Sourav’s mother comes into the room. She recognises the plump woman; she is, indeed, a relative. The woman says in an admonishing voice to Sourav’s mom, “Your daughter-in-law could not recognise me at all.” The daughter-in-law is unfazed. She walks away coolly.

The phone rings yet again. Sourav’s mother picks it up. There is silence at the other end. She says aloud, “Why do these people call up if they don’t want to speak?” Then, they all go into the bedroom. I am left again to contemplate the sky through the balcony. The phone rings. This time, one of the retainers picks it up. There is a conversation. The retainer gives the standard answer: “He is not at home. He has gone for practice.” The retainer puts down the phone and tells me with a smile, “It was a girl.”

‘Chicks,’ I thought suddenly. ‘In hero-starved Bengal, Sourav had become a sex symbol. How lucky!’ I am getting impatient. The next time Snehasish’s wife walks into the room, I get up and approach her. I told her that I had an interview fixed at 11.30 a.m. It is now 12 noon. She replies that Sourav is already doing an interview at present. She suggests that maybe I could do the interview at the same time. I balk at the idea. Then she suggests that at least I could sit in the room where Sourav is doing the interview. I agree.

We enter the main drawing room. I seem to have been sitting in a secondary drawing room. The curtains are drawn; the lights are on. Sourav is sitting with Rupak Saha, the Sports Editor of Ananda Bazar Patrika. He is wearing a white kurta and pajamas. I sit on the opposite sofa. The air-conditioner is working in full blast. There is a large TV set at one corner.

There is a body-length picture of Sai Baba on one wall. On a mantelpiece, there are statues of Swami Vivekananda, Ramakrishna Paramahamsa and the Divine Mother.

On another sofa, Sourav’s father, Chandi Ganguly (a printing magnate), is reclining, his head on the arm-rest; he is reading some typed foolscap sheets of paper. Time passes. I cover my mouth with my hand and yawn surreptitiously.

Snehasish, Sourav’s elder brother, also dressed in a white kurta and pyjama, comes in. He asks if Sourav has had anything to eat since morning. The young hero nods his head in assent.

Snehasish’s wife comes in smiling. She asks Sourav to take a call.

“Maharaj (Sourav’s nickname), Mr — has been ringing for the 70th time. Please speak to him. Tell him that you have to go to practice.” Sourav picks up the cordless phone lying next to him on the sofa. He speaks politely; he says that he will call back after an hour.

A female freelance journalist, whom I recognise, comes into the room. She says something to Sourav. He smiles. She turns around; she recognises me. She comes up to me and says, sotto voce, “I’ve already got an interview.” I smile.

Time passes; the Ananda Bazar interview goes on. It’s yawn time for me again. Then suddenly, more visitors come into the room. They are people from a multinational company – three young men and a girl. Sourav’s father gets up and goes out of the room. They sit down on the same sofa. The young, comely girl comes and sits next to me. I try to catch her eye. She is busy trying to catch Sourav’s eye. There is an intense speech by the head of the group.

“We want to help the young, budding cricketers from Bengal. We hope to sponsor a couple of them for training in England.”

Sourav replies with animation, “Look, my experience is that sending a young person to England does not help a cricketer much. I mean, there is not such a marked improvement in his game.”

He pauses and then rushes on. “You are a company with enormous financial resources. This is my suggestion to you: why don’t you start a cricket academy in Bengal? We desperately need such an academy. There is so much talent here in Bengal. But there is no chance to develop it. So, an academy is my suggestion. The West has the Sungrace-Mafatlal backing. In the South, there is the MRF Pace Academy. But we don’t have anything here in the East.”

“Good idea, good idea,” the Group Head replies. “We have to think about it.”

Sourav continues, “If you spend some money, you can get people like Kapil Dev and Sunil Gavaskar to come and coach in short stints. That would be of terrific benefit to the youngsters. Also maybe, you could call Geoff Boycott. He is a cricketer with vast knowledge of the game. He will do wonders with the youngsters here, if he is allowed to coach for a stretch of two months or so.”

The conversation meanders on. Ultimately, to use college slang, they “cut the crap out” and ask Sourav what they wanted to ask in the first place: will Sourav sign small-size cricket bats, so that they can present to young kids? He could present it to them during the Pujas.

It was basically a commercial proposition.

Sourav answers immediately, “I won’t be here for the Pujas. I’ll be in South Africa.” Then there is a pregnant pause and perhaps, knowing the treacherous world of Indian cricket and its incessant intrigue and politicking, he adds, “If I am selected.” (This was before the team to the Singer Cup was announced.) They nod. He looks around.

Then smoothly he says, as he also realises that it is a commercial proposition, “Why don’t you come to my office the day after tomorrow. We can discuss the matter again.” (Sourav works in Tata’s). There is nothing more to say. They stand up; they shake hands including the girl who was sitting next to me. They wish him goodbye. They leave.

A few minutes later, Rupak Saha also leaves. And so dear readers, it is now that I have a chance to interview him finally. One-and-a-half hours have passed. Sourav looks tired. I wish to interview him another day, but I know that things will be the same hectic whirl, today, tomorrow and the day after.

Here are excerpts from the interview:

ON HIS EARLY LIFE

When did you start playing cricket?

I started playing the game when I was fourteen years old. Earlier, I had been playing football. But I thought that I would give cricket a try. By this time, my elder brother Snehasish had already started playing for Bengal. I liked cricket from the very beginning. Within a year, I was selected for the Under-15 Inter-State tournament.

Your game is very stylish and text-book perfect. Where did you learn it?

I was taught the right techniques by very good coaches like Debu Mitra. It is very important to have a good coach from the very beginning.

Your father was a Ranji Trophy player. Was that the reason why you had decided to take up cricket seriously?

No. Not at all. I started playing cricket out of curiosity. Then I found that I liked the game a lot. It has got nothing to do with my father.

When did you start playing for the senior Bengal team?

I made my debut for Bengal in 1990 in the Ranji Trophy. Then when I was 17, I was selected to the Indian team to tour Australia.

ON THE MAIDEN TOUR OF AUSTRALIA

Can you tell us something about the tour of Australia?

As soon as I mention the word Australia, his face puckers up, in dislike, dismay and frustration. “Please,” he says, “I don’t want to talk about it any more. What is over, is over. I just want to look ahead now.”

Listen, I know the tour was not a good one for you. (Sourav scored 3 runs in the only game that he played.) But my angle is this: I feel that Indians take much longer to act mature. I mean, we are not as mature as Americans and Europeans are, at age 17. What do you think?

No, I think we are as mature or, in fact, more mature than Europeans and Americans. But in my case… please, please, I just don’t want to talk about it.

Come on Sourav, a little bit of analysis please...

He presses his lips together in frustration.

Has it got something to do with the Indian team?

No. Nothing of that sort. It’s just that I didn’t click in the opportunity that I got. In Indian cricket, you are just given one opportunity. If you don’t click, you are out.

In that tour, there were reports of your arrogance off the field. Your famous refusal to do twelfth man duties…

I was never arrogant. It was a misconception about me. I am basically a quiet fellow. I love to be by myself. That was taken to be arrogance.

Surely matters were not helped at all that you had a nickname called ‘Maharaj’.

But that’s just a nickname. It’s stupid to make a judgement of a person by a nickname.

Who gave you this negative press coverage?

I don’t remember.

Was it the Bengal media?

I think so.

Did it affect your image permanently?

Yes. People automatically assumed that I was an arrogant person. But it didn’t affect me because I used to lead my own life, have fun with my own group of friends.

You come from a wealthy background. Your family has a large printing business. So, this affluence is a plus point, isn’t it?

Obviously, it’s a plus point. To be financially well off eases a lot of pressure. Like not having one’s parents dependent on you takes a lot of burden off your shoulders. It gave me a chance to concentrate on cricket 100 per cent.

After 1992, your next chance came only this year. How did you manage those years in the wilderness?

I was determined to play for India. I was determined to prove people wrong. So I just went on playing and practising.

But weren’t there times when you were depressed and disappointed that you had not been selected to play for India?

No, I was not depressed. I knew that if I did well, the selectors would give me a chance one day or the other. I knew that if I got a chance, I would try to prove that I was a good player. If I didn’t get a chance, I would still play. Because I love cricket. I never eased up for a single moment. Basically, if you love a game, you tend to play, whatever be the case.

ON WHETHER HIS FATHER PLAYED A ROLE IN HIS SELECTION

Your father was once a secretary of the Cricket Association of Bengal. He is close to Jagmohan Dalmiya. Did your father’s presence help in your selection to the Australian tour and this England tour?

My father left the CAB in 1986, even before I started playing. So if people continue to connect him to the CAB, then it’s really stupid. That’s all I have to say. Also even if my father had a hand in my selection, ultimately, I have to perform at the wicket, isn’t it? People should be looking at my performances rather than talking about these things.

Do you think your family has some enemies, that the rumours still persist about your father’s influence within the CAB?

There is a possibility. People do not like my family. I think they are jealous. That’s the basic point.

Perhaps your affluent background must be the reason?

But what can I do about it if I have been born into a wealthy family? It’s like what can you do if you are born dark or thin? One can do nothing about it. If people make a big fuss about it, it’s really stupid.

ON THE ENGLAND TOUR

Watching you on ESPN and now physically meeting you, I get the feeling that there has been a tremendous mental change. Would you agree to that?

Yes. I’ve become mentally much tougher. In Australia, I saw first hand that international cricket was all about the mind. I knew that I had to be mentally tough if I wanted to succeed.

What exactly did you do to toughen yourself?

Nothing much really. I just carried on with my game. I trained a lot. You become mentally tougher as you keep on playing. Sometimes you succeed; sometimes you fail.

When you failed, how did you tackle it?

I would analyse what went wrong; why did I play that particular stroke that got me out? Was it necessary, etc? It’s something you have to do on your own. Nobody can make you a cricketer. It’s what you do on your own and what you do at the wicket that makes the difference. Nobody can help there.

Is failure the best stepping stone to success?

Always. Failure is the key to success.

I heard that you went to a counsellor in England, to get advice on strengthening you mentally. Is this true?

Nothing of that sort, really. I met a guy who had done a course in sports psychology. I used to meet him casually.

What did he tell you?

He just told me to stay relaxed. That I should be bothered more about my game, rather than my surroundings. It’s a part of cricket that people will criticise you; they will write negatively about you in the newspapers, etc. One should not bother about all that. Instead, one should concentrate on one’s game.

People talking ill about you – were you damaged by this harsh criticism?

No, I wasn’t. Because I knew what I was doing. I knew that some day or the other, I would prove myself as a player.

But when you are young, criticism can be a very painful experience.

Yes. But it has helped me become stronger as a person.

ON THE MAIDEN TEST HUNDRED

Coming back to that maiden Test century at Lord’s, what exactly was going on in your mind?

I just wanted to go and play my best. I never had any thought of scoring a century or something like that.

On TV, I got the feeling that after playing every ball, you seem to be in some sort of an inner dialogue with yourself. Is that true?

Yes, I was telling myself to be there at the wicket, to stay as long as possible. If a good ball gets me, it doesn’t matter. The main thing was that I should not play a bad shot and lose my wicket. I also told myself that I must play the next ball on merit. If it is there to be hit, I’ll hit it; if it is there to be defended, I’ll defend.

Normally, don’t players have this inner dialogue?

Yes, I think so.

Then how come not all players are successful?

That’s a very difficult thing for me to say. How come most people are not successful? I think it is an individual thing.

What are the lessons that you have learnt from this England tour?

I have learnt what Test cricket is all about. I’ve learnt to take the pressure. With my two Test hundreds now, I feel that I am capable of playing Test cricket. I have that belief now. Self-belief is very necessary if you want to do well in life.

ON ADULATION

Overnight, you have become a celebrity. Bengal has gone crazy over you. How do you cope with the adulation? Do you believe it?

I believe it. I am happy that people are happy that I’ve done well, especially the people of Calcutta. I just want to carry on, to play as much as I can, as well as I can.

Can you describe the adulation that you received when you returned from the England tour?

There were so many people on the streets. Kids coming and taking autographs. People coming and taking interviews. People wanted to see me. People wanted to felicitate me. It is a lovely feeling. It’s lovely to see people taking so much interest in your performance and they are happy in the same manner that you are.

Is there a danger that you will get swayed by all this?

I don’t think so. I have seen both sides of the coin. I have been out of the team for three years. I have seen people behave. Now that I have done well, I have seen people behave in a different manner.

What do you understand about human nature from that?

Public memory is very short. That’s the first conclusion that I came to.

Did you have the experience of people who have abused you in the past, now coming to shake your hands?

Yes. I have had that experience recently. But let me tell you that I have enjoyed that also.

Is it because ‘Revenge is a dish that tastes best when it is cold’?

No, no. Nothing of that sort, really.

Later, I was talking to Utpal Sarkar, the photographer. We were analysing reasons for this extraordinary adulation that Sourav had received, ever since he came back from England. Utpal asks me a simple question: “Tell me, after Independence, how many Bengalis have made an international impact?”

“Satyajit Ray,” I begin. “Perhaps Nirad Chaudhuri, the writer.”

Then I can’t come up with any names.

Utpal says, “The only name that I can come up with is Swami Vivekananda with his famous speech at the Parliament of World Religions at Chicago. But that was years before Independence.”

ON THE COMPETITION WITH VINOD KAMBLI

I don’t understand why people talk about Kambli and me. It has got nothing to do with me., There are four places in the middle order. I have just taken one of them. If Kambli is good (and he is good), he will play at some other number. But that doesn’t mean that he will play at somebody else’s expense. I really don’t understand why people keep comparing me with Kambli.

I think…

He rushes on, “Just because I am a left-hander, and Kambli is a left-hander. But then a team can have two left-handers. What’s the problem with that?”

There was a report…

You tell me something. If Kambli was dropped before the Singapore and Sharjah tournaments, and I wasn’t in the team at that time, why are people comparing me with Kambli?

I finally manage to ask my question: Kambli comes in at Number Three, the slot that you are occupying now…

Okay. Then he will come at No. 5. What’s wrong with that? He is at his own place. I am at my own place. Why can’t two left-handers play for India? I have seen cricketers writing about it.

Do ex-cricketers writing in the newspapers upset you?

No, it doesn’t. Also, I don’t read much that is written on cricket. Especially during the season. If there is a photograph in the paper, I see it. Otherwise, I just close the sports page. I don’t want to read anything that is written about me.

That’s probably a wise thing to do.

He smiles suddenly. We are coming to the end of the interview. His brain has gone blank; he has been speaking non-stop for hours now, and I can feel hunger pangs from my stomach.

The interview over, Sourav leads me out of the drawing room.

Outside, I meet the durwan again.

His name is Sunil Mondal. He is perspiring. He looks harried. We stand and chat near the gate. I point at the three big buildings in the compound.

“How many people live here?” I ask.

“There are seven families living here. It is the brothers of Chandi Ganguly and their families.”

“How many rooms?” I ask.

“I am told that there are 100 rooms.”

I look straight ahead. There are quite a few cars parked at one side.

“How many cars?” I ask.

“Eighteen,” comes the reply. “And you know, I have to note down the kilometre reading every time a car goes out and comes back.”

“How many cars does Sourav’s family have?”

“Four,” he says and adds, “they also have four drivers, one for each car.”

“And servants?”

He moves his thumb up the ridges of his other fingers. He looks up at the sky. He frowns; then he says, “They have nine servants.”

Amazing really! He smiles when he sees my look of incredulity.

“Okay, in total, how many people are living in this compound?”

“I think, with servants and other help included, there must be about 150 people.”

We move to the gate. He opens the lock.

“Why do you have to keep the gate closed like this during the day? Isn’t a latch enough?”

“Babu, do you know how many people have come today?” he asks with a smile.

I shake my head.

“About three hundred people,” he says.

“Three hundred,” I exclaim, “how’s that?”

“About 150 schoolchildren came from schools in Barrackpore and other such places. How can we say no to them when they have come from so far away? Then there were college students. There were a couple of photographers. Journalists from Aajkal, Bartaman and two of you from Ananda Bazar. Then there were representatives from some big companies. So if I don’t keep the gate closed, people will just swarm in…”

We fall silent now. I say goodbye to Sunil Mondal and then I walk away.

Sourav Ganguly has become the Maharaj of Bengal’s field. Only time will tell whether the Sourav Ganguly wind experience is just a flash in the pan or it is an enduring star. After all, the England bonding was of not such a high standard. His stern test will come in South Africa where the pitches are fast and bouncy; where pacemen like Allan Donald, Shaun Pollock, and Fanie de Villiers are going to be brilliant and hostile.

Before that, there is a Sahara Cup in Canada where he will have to encounter the likes of Waqar Younis, Wasim Akram and Mushtaq Ahmed.

But for Sourav Ganguly’s sake, knowing that where there is adulation is virulent criticism, I wish him continued success on the international stage.

Maharaj Ki Jai Ho!

(Published in Sportsworld, August 28, 1996)

October 24, 2025

Chatting with my mother

Photos: My mother today; my mother with her first-born, a daughter; my father; my mother (second from left) with her siblings who have all passed away

Photos: My mother today; my mother with her first-born, a daughter; my father; my mother (second from left) with her siblings who have all passed away By Shevlin Sebastian

Whenever I go to my mother’s room, I am happy to see that she is always dressed well. It’s a habit my father had. And the kids have picked it up, especially me.

Nowadays, she recites a two-line verse in Malayalam from her childhood. ‘Amma, Amma, I am going/If you don’t see me, don’t get worried.’

“What is the meaning?” I asked her.

My mother said, “We would say this just before we left for school. There were Britishers in our town of Muvattupuzha. There was talk that they kidnapped the boys but left the girls alone.”

Once, on a visit to a nearby rural area, she pointed out the plants around us. “That is jackfruit cultivation going on,” she said, pointing with her index finger. “Those are banana plants. Look at the tall coconut trees. Right next to them are newly planted coconut plants.”

I said, “Do you think the small coconut plants may be telling the tall trees, ‘Amma, Amma, I am going / If you don’t see me, don’t be worried’?”

My mother laughed, tapped my elbow and said, “Don’t be silly.”

On the cusp of 89, my mother forgets things quickly. But the old memories remain intact.

“My husband was a good man,” she said. “Appachan looked after me with so much care and affection. I was very lucky. In those days, men treated their wives roughly. But your father was always gentle with me.”

My mother paused and said, “Now Appachan is in a good place.”

My father, ten years older, died on February 18, 2021, at the age of 94.

My mother also praised her own father. “I will never forget that when my father wanted to scold me, he would never do it in public. He would take me aside and speak to me gently.”

My mother was indeed lucky. Two of the primary influences in a woman’s life – a father and husband – had been good to her. As I looked at my mother, I couldn’t help thinking how vulnerable women are to a man’s violence. Women have little defence, even though the laws against gender violence have become stronger. But how many women, except for a certain strata, know about these laws?

My mother likes to read the newspaper. She told me she kept me on her lap when I was a baby and read the newspaper. “You were a quiet baby,” she said. “You made no noise.” It’s a habit she passed on to me. Even now, I devote my early mornings silently reading the newspaper with a cup of tea. I will always thank my mother for my love of reading.

In her room, my mother pointed to a news scroll at the bottom of a television screen. Then she said, “Can you read Malayalam?”

I shook my head and said, “We were in Calcutta.”

She looked at her middle-aged son and said, “I should have taught you when you were a child.”

There was regret in her voice.

I remained silent, as I pondered over what she said.

My mother showed me a family photo taken in the 1940s. When I peered closer, to my shock, I realised she was the only one alive. Seven of her siblings had already passed away. Time kills everyone, I thought. It will kill my mother, me, and all those close to us.

My mother has aged well. There are not too many wrinkles. Touch wood, she has no major health problems. She takes no tablets at all. Both of us are shy about showing emotion. But I compensate by trying to reveal emotion when I write.

One day, I woke up with a thought: This good-hearted woman carried me for nine months and brought me safely into the world and cared for me till I grew up. How great women are!

(Published in rediff.com)October 21, 2025

The Toss of a Coin

By Shevlin Sebastian

It happened one summer night. Ramesh and I were quarrelling at a petrol pump. We had gone to fill petrol. It was the night we had finished our ICSE exams, and we were in a happy mood. We were on Anirban’s motorcycle, and Ramesh and I were fighting over who would sit in the middle and who would sit at the back.

“Gautam,” he said, “you always want to sit at the back, but I think it’s my turn now.”

“No,” I said. “I want to sit at the back because I like it, and because I am bigger than you. I am uncomfortable in the middle.”

“Nothing doing,” said Ramesh. “I want to sit at the back.”

We kept arguing till Anirban said, “Come on, let’s solve the problem by tossing a coin.”

“Yeah,” said Ramesh, laughing. “Heads I win, tails you lose.”

“Come on,” Anirban said, “be serious. Gautam, what do you want?”

“Heads,” I said unhesitatingly.

We watched as the coin spun in the air and landed on the grease-stained ground. We peered into the shadows and then Ramesh leapt up and punched the sky with his fist.

“The mark of a champion,” he said. I didn’t want to argue any more. Anirban started the motorcycle, and then I got on and Ramesh sat at the back.

It was twelve-thirty at night, and we were on the outskirts of Calcutta. Now we were going on a long ride on the highway, and we were nervous. Firstly, because Anirban had no licence and secondly, it was a little frightening to be travelling so far away from home. But come on, today we had finished our ICSE exams, and it was time for some fun and excitement.

Anirban released the clutch and turned up the accelerator. We were off.

We were going very fast, and there was a real thrill in it. We gripped the sides of the seat as Anirban went faster. The roar of the engine filled our ears. We had to narrow our eyes because the breeze was very strong. We were all tense and excited. Anirban increased the speed, and now we were going much too fast.

This was dangerous speeding, but we didn’t care. Suddenly, a lorry came out from a side street. We had barely time to notice the headlights before it crashed into us, and we were all flung into the air.

When I next opened my eyes, I was in a hospital room. The sunlight was streaming in through the window. I could see my mother standing beside me, her face full of worry, and she held my hand. She smiled suddenly when she saw that my eyes were open. The nurse was standing close by in her starched white uniform. A doctor with a stethoscope around his neck was also there.

“So, how do you feel, Gautam?” the doctor asked.

“Stiff,” I replied. “Have I broken anything?”

“Yes, you have fractured your right leg and your right hand,” he said and smiled. “But don’t worry, everything will be all right.”

Then the doctor drew my mother aside and whispered something into her ear, and then he left the room. My mother came up to me, and I asked, “Where is Papa?”

“He’s coming, Gautam,” she replied. “He was here till about fifteen minutes ago. There was some urgent work in the office, and so he had to rush back. Gautam, don’t worry, there’s nothing to fear. It is only a broken bone, and it will heal in time.”

I nodded, and began to feel sleepy again. My head was buzzing, and I felt tired. But I managed to whisper, “How are Anirban and Ramesh?”

“They are all recovering, Gautam, don’t worry,” she said. And gratefully, I drifted off to sleep.

The days passed. Finally, I felt better and stronger. I was allowed to leave the hospital. It was great to be back home, with my parents, my books, my table, my chair, the bed, and the tape-recorder. I was glad for the comforts that belonged to me. I was an only son.

After returning home, my recovery was very fast. The buzzing went away from my head, my eyes cleared up, I had a good appetite, and I got up earlier in the mornings. Soon, I was hobbling to the drawing room to watch breakfast television, and my sense of humour came back. I felt fine. Sometimes, when I asked about Ramesh and Anirban, my mother would say, “They are recovering, but they are still in hospital.”

It was only months later, when my bandages were removed and I was able to walk normally, that my mother and father told me the terrible news.

“We pondered over it,” my father said. “And we decided it was best for you not to be told anything while you were recovering. But we can’t hide the truth any more. Gautam, Ramesh and Anirban are dead.”

Suddenly, my head whirled, and I remembered the toss of the coin. In the background, I could hear my father’s voice:

“It was just bad luck. It was Ramesh who was sitting at the back. The lorry hit the end of the bike from the side, and Ramesh was instantaneously crushed. Both you and Anirban were flung off the bike. Anirban hit a lamp post with great force and suffered a severe concussion. He died in the hospital. You were hurt badly because you fell with great force to the ground.”

But I couldn’t hear anything more. Again, I could feel the buzzing in my ears, and I saw the toss of the coin as it flicked through the night air and landed on the ground followed by Ramesh’s exultant cry of triumph.

I had been saved from death by a whisker. If Ramesh had not protested, it would have been I who died and not Ramesh.

I was given a fresh lease of life. I was given the chance to live again. That frightened me.

One friend’s death was another friend’s salvation.

(Published in Target Children’s Magazine, India Today Group, August, 1989)

October 17, 2025

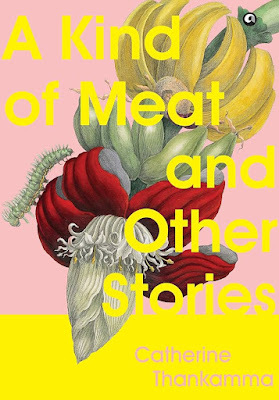

Cutting through Cant

Catherine Thankamma, long known as a translator of Malayalamliterature, steps into the spotlight with her debut short story collection, ‘AKind of Meat and Other Stories’

By Shevlin Sebastian

The road to Catherine Thankamma’s house in Kochi leads to acul-de-sac. So, there is little traffic. There are trees all around. Asexpected, it is very quiet inside the house.

Catherine is beaming as ‘A Kind of Meat and Other Stories’(Aleph Publishing) is gaining lavish praise from early readers.

The book runs to 206 pages and contains 20stories.

In Catherine Thankamma’s first story, ‘A Family Affair’, amatriarch correctly predicts who stole a bag of jewellery from her house,approaches him, and tells him to return it. The writing is simple andaccessible.

In the subsequent stories, Catherine captures powerfully theethos of the Syro-Malabar Catholics of Kerala (total worldwide population: 55lakh). Catherine uses Malayalam words for dialogue and description. Onecharacter Eli Chedathi said, ‘Ente karthaveeshomishihaye’ which means, ‘My LordJesus Christ.’

In another story, five-year-old, Saira, of a family rentingone part of a bungalow in Chandigarh tells the house owner that they eat beef.This leads to tension between landlord and tenant.

In the story, ‘Madhu’, Catherine captures the lower-castediscrimination faced by a woman garbage collector in North India. Though moststories are only a few pages long, they evoke deep emotion in readers.

Her subjects include the effects of communal riots, collegetransfer politics, learning disabilities of children, mental illness, and ayoung gazetted officer, treated with barely disguised contempt, gingerlyhandling a polling booth. All the stories are told from the viewpoint of women.It’s the subtle, vicious quarrels that happen between women beneath the gaze ofmen.

The writing can be searing. Here are a few lines from‘Silence and Slow Time’, which focuses on the impact of vascular dementia: ‘Thesurgeon never warned me you could end up like this; that the part of the brainthat made you, you – your imagination, your intellect, your wit, yourlinguistic skills – might be severely damaged by the haemorrhage.’

In a later part of the story, Catherine writes, ‘How do Icome to terms with the new you? Your blank stare fills me with guilt anddespair; I ache for that precious thing, now lost forever. I know your eyeswill never light up again. Should I be relieved that you didn’t die on thetable like that young mother, so full of life, who unlike you, enthusiasticallysigned the consent form for surgery and left behind two young children? Thisdead life, how can it be better?’

In ‘Blood Sacrifice’, she describes the violent attack on aMalayali nun in Bandipur, Chhattisgarh, in harrowing detail. Here are a fewlines: ‘With a snarl of fury, the hairy arm seized the crucifix from the tableand swung it at Sister Karuna. Crooked blood lines coursed down Sister Karuna’sface, as she fell backwards. He kicked her aside.’ The miscreants raped heryounger colleague, Sister Anne.

And in the extraordinarily powerful story, ‘Pieta’, whichdepicts Jesus’s mother Mary as an ordinary woman, the author writes, ‘Is itpiety that you feel when you hear of paedophilic priests molesting children, ofbishops raping nuns, of clergymen arguing vociferously on how to say the Mass,then hear the same wrangling fraternity declare from the pulpit, “Let us followour Lord and not throw stones; let us pray for truth and justice to prevail.”’Unbelievable!

Catherine adds: ‘What is he [Jesus Christ] in truth, but afigurehead for a mammoth corporate managed by hard-headed managementgurus?’

This is writing wielded like a scimitar cutting down cant andhypocrisy with a powerful slash.

Catherine says that she had been writing short stories forthe past 30 years. Only a few have been published. Since both her husbandJoseph and she were in transferable jobs, he in a bank, while she was anEnglish teacher in government service, many a time, she had to handle things onher own. Bringing up her two daughters, looking after the household, andmanaging her own career, time was always in short supply. As she said, “Therewas just no time to think about writing.”

But Catherine loves to watch and listen to people and hearexchanges. “When something struck me, I used to write down points,” she said.“And then, over the course of several months, I wrote stories around fleetinginstances, occurrences, chance encounters, and exchanges. The focus-drivenbrevity of the short story is the best medium for me. So, I kept writingthat.”

In 2015, after her daughters had grown up and Catherine hadretired as an associate professor, she finally had time for concentratedwriting.

Interestingly, she sits on a wooden chair in her bedroom,places the laptop on her lap and does the work. When she looks up, she can seea collage of photos of her late husband Joseph, who died in 2011, hanging on anearby wall.

“Joseph was such a jovial person,” she said with a sigh. “Myhusband always encouraged me in my writing.”

Asked why she had focused quite a few stories on theSyro-Malabar community, Catherine said, “I belong to this community. On thesurface, there is piety, church-going and community gatherings. But underneath,many of the family relationships are toxic. I wanted to show the darkunderbelly.”

But in the end, she says, the book is a celebration. “Icelebrated the quiet resilience with which women face reality,” she said. “Myhusband's death has taught me that we are clueless of what the future holds forus. What little agency we have is how we should confront the reality lifethrows at us.”

Apart from being an academician, Catherine has been a notedtranslator of books from Malayalam to English. The first was ‘Kocharethi’ byNarayan, which won the Crossword Book Award in the Indian language translationcategory in 2011.

The others include ‘Pulayathara’ by Paul Chirakkarode,‘Susanna’s Granthapura’ by Ajai P. Mangattu, and ‘Aliya’ by Sethu. Sethu.Another book, ‘Ayyankali: A Biography’ by M. R. Renukumar, will be publishednext year.

Asked about the striking cover, Catherine said, “I found itinteresting, the juxtaposing of the word meat with this very earthy image of abanana flower, about to unfurl, with a caterpillar crawling on the edge of aleaf.”

Undoubtedly, Catherine has made a stunning debut, and is onher way to becoming an important voice in South Indian fiction writing.

(A part of this article, appeared in interview form, in theBooks Section, Hindustan Times Online)

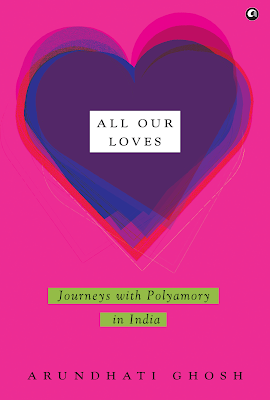

October 14, 2025

Breaking the Myths Around Polyamory

‘In All Our Loves – Journeys with Polyamory in India,’Arundhati Ghosh challenges the common misconceptions of polyamory. She revealsthe complex and often difficult reality of those who practice it

By Shevlin Sebastian

The first lines in the introduction of Arundhati Ghosh’sbook, ‘All Our Loves – Journeys with Polyamory in India’ begin like this:‘Unlike Emily Dickinson’s “hope”, love is not “a thing with feathers”. It hasfangs and talons. It bites, it stings, it makes you want to end your life. And,it makes your life totally worth living, with all its dangerous, complex,seductive possibilities. In short, love is hard.

‘But love that attempts to cross boundaries is harder. Lovingin ways that the world considers wrong could make one liable to suffer mentalabuse, bodily harm, and even death. Anyone who has fallen in love with thosesocially declared as the ‘wrong’ gender, caste, colour, race or religion, knowsthe price that has to be paid for such transgressions.’

Today, polyamory is the last taboo. Arundhati defines it as‘being in love, with or without sexual intimacies with more than one personsimultaneously with the consent of all.’

One of the reasons she wrote the book was that in India, mostpeople learned about polyamory by reading Western books. But Arundhati arguedthat the Western experience was completely different from the Indian one. Wehave a multicultural society, and family and community press down on theindividual with fearsome force. It is the rare person who can break through theconditioning and launch out on their own.

This book delineates the various aspects of polyamory. In onesection, Arundhati focuses on its misconceptions.

The stereotype is that all polyamorous people arepromiscuous, predatory, desperate and amoral. They are easy and cheap. Manybelieve polyamory is a mental disease. They also conclude that allrelationships are shallow and of limited duration and it’s all about the sex.‘In reality,’ writes Arundhati, ‘many polyamorous people I know are asexual, orwhile being sexual, do not consider it the most important aspect of romanticrelationships.’

One reason people opt for polyamory is to explore desiresthat cannot be expressed in a monogamous relationship. Polyamory is the onlyway to express that aspect of themselves. Arundhati writes: ‘I am polyamorousbecause my heart sees beauty, courage, kindness, and compassion in more thanone person and desires to connect with them. The same reason for which anyonewould fall in love with just one person, I fall for more than one person. Ijust refuse to say, “Stop. Your quota is done.”

One of the most interesting insights Arundhati shares is thatdespite having many partners, you can still end up feeling lonely and alone. Sowhen somebody is going through a bad time there may be no partner around toprovide solace or love. You have to battle the demons on your own. This happensin monogamy too. One friend told Arundhati that ‘one of the most desolateplaces in the world is to sleep lonely on one side of the bed shared everynight with the same person for years.’

As Arundhati describes the various complexities that arisefrom polyamorous relationships, one danger always lurks thanks to mentalconditioning from a young age. So, participants can drift into emotions likejealousy, a sense of possessiveness, and the fear of being cast to the side.They can also suffer from shame, guilt and denial. As a result, manyrelationships break up.

And there are other dangers too. Women being mistreated bymen under the facade of polyamory. Arundhati talked about a couple, Jane andAmit who lived four years together in a live-in relationship. One day, Amitsaid that he wanted to bring a male friend into the relationship. In otherwords, he wanted Jane to take part in polyamory.

A confused Jane said they should go to counselling, to have abetter understanding of the situation but Amit refused. She was given no choicebut to accept or reject the idea. It made Jane feel vulnerable. WroteArundhati, ‘Across all of polyamory’s ways of being, there is never anycompromise on a person’s dignity and self-worth.’

After hearing many stories like this, Arundhati has saidpeople should be careful when engaging in polyamory. ‘This warning isespecially relevant for women, queer people, those already marginalised bycaste, race, religion, and more, because it is easy to take advantage of themamidst the unequal power balances of the world they inhabit,’ wroteArundhati.

There are happy stories, too. Arundhati did an interview withmedia professional Revathi and her husband Subir (both pseudonyms). WhileRevathi is in her forties, Subir is in his fifties. Both have had relationshipswith other people for a long time. Revathi said, “While I have had sexualconnections with many of Subir’s lovers, he has only rarely had that with mylovers. It is a veritable tightrope-walk at times, but it has led to a sense ofa deeply-felt freedom.”

She continued, “Sometimes, people like us miss the emotionalpart when it is too sexual and miss the pure ecstasy of sex when we getemotional. A balance is desirable.”

Subir said, “I derive a lot of sexual pleasure from talkingto her about her individual experiences. It can be very stimulating for me….

“I like to watch her being pleasured by another man or woman.I also like her watching me having pleasure and having pleasuretogether.”

Like any couple, they suffered from jealousies andinsecurities and have worked through those minefields.

Asked whether they are honest with each other, Revathi said,“Honesty is different from being transparent and pouring out all the details…It is one thing to know that your partner has just slept with someone else butit’s different when one goes into the details of the sexualencounter.”

One of the takeaways from this book is how much we areconditioned by our parents, schools, friends, and society to think the way wedo and adopt social and cultural practices. Or as interviewee Shankar says: “Weshouldn’t take the ‘one size fits all’ that society wishes on us. Children growup with this mindset; it is indoctrinated in them. They think you have to be ona relationship escalator – like one thing must lead to the next. Dating,falling in love, marriage, babies – that’s life. The only life. That’s howinsidious the social programming is.”

It comes as a shock to realise one’s value system has beenimplanted from outside us, especially when we were in the most vulnerable andinnocent – our childhoods. It opens us to the possibility that the life onelives is the life that has been prescribed by society.

We have not stopped to think whether this is the way oneshould lead our life. Is there anything original in our thinking and behaviour?Sure, people veered from the norm, sometimes destructively, like psychopaths orkillers. But for the most part, members of society tread the same path previousgenerations have walked. So what’s original about one’s life? The painfulanswer: ‘Nothing.’ We have lived the life of a robot.

If you are a believer in polyamory or a practitioner, thisbook will act as a soothing balm, a gentle friend talking to you in the deepwell of loneliness and isolation that you may find yourself in, because of thispowerful emphasis on monogamy in mainstream culture and society.

Arundhati, who practices polyamory, has provided great valueand importance to the subject with her path-breaking book. Kudos to her.

(Published in kitaab.org)

October 9, 2025

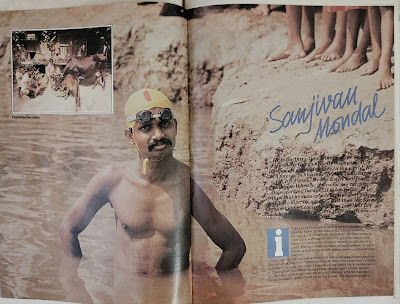

A river runs through his life

COLUMN: Tunnel of Time

Sanjivan Mondal is the three-time winner of the 81-km race on the Ganga near Berhampore. It is possibly the longest swimming race in the world

By Shevlin Sebastian

Photographs: Nikhil Bhattacharya

It was a hot September morning.

Sanjivan Mondal stood by the side of the Churni river in Ranaghat, 90 km from Calcutta. He was staring intently at a group of children gambolling in the water. He bent down and corrected the stroke of a child. His son. And the child already seems to have the knack that the father possessed to a remarkable degree.

Sanjivan turned and smiled when he was introduced by Gautam Mukherjee, a childhood friend. The smile was wry, a little helpless. The eyes were sad. He gave a limp hand for a handshake. In these quiet, soothing rural areas, people don’t shake hands. So, he was a little surprised when a city slicker offered his hand. He smiled again and invited us to his house.

We walked along a narrow mud path, framed by trees and their branches formed an overhanging arch. At the side, children played marbles. Birds chirped in the trees. A hen hurried across the path. A slim young woman with downcast eyes walked demurely past.

This was Ramnagar, where Sanjivan lived in a hamlet of weavers in one-room houses with a courtyard in front and at the back. He led us into his hut. It was dark and cool and dominated by a single bed. Alongside one wall were two trophies. It seemed incongruous in that environment. There was a cycle parked on one side. Pots and utensils filled one corner. The family stared in surprise. The wife scurried about. There were four children, two boys and two girls. One girl had an eye closing now and then. The family didn’t know the reason why.

Sanjivan began speaking by saying, “Yes, I have become famous in these parts.”

He is the three-time winner of what could possibly be the longest swimming race in the world. The distance is 81 kms. It is an annual race conducted by the Murshidabad Swimming Association. Swimmers from all over India take part, and in rural Bengal, especially in places like Ranaghat, Shyamnagar, Murshidabad, and Malda, there is tremendous interest in the event. This is an area, where because of a preponderance of ponds, everyone is a swimmer.

The race starts at the crack of dawn at a place called Jangipur Ghat. And it is a race that lasts the whole day, about eleven hours before it ends. It is a race that blends skill with stamina, determination with desire, and strength with staying power.

“Eighteen swimmers took part,” said Sanjivan. “The river was smooth this year. Since it wasn’t raining, there were no waves to contend with. We started off at a brisk pace and there were a lot of young people who moved off into the lead. But I wasn’t worried. They didn’t have the stamina. They were just using their strength. The only swimmer I was scared of was Khagen Dutta, who was lying fourth. He had won this race quite a few times. I knew he had the experience to come up suddenly. I kept looking back, but he didn’t come up, and by the time five hours had passed, I was swimming all alone.”

People crowded the sides of the Ganga. Boats kept track of the swimmers. Every now and then, Sanjivan used to gulp down a glass of glucose that he received from volunteers in a boat that was following him.

“There’s a certain technique,” he said, a smile lighting up his face. “You have to know how to conserve your strength. After two or three hours, your arms begin to hurt, because you are swimming in a particular way. Then you have to use a new stroke. These are the tricks of the trade.”

Eleven hours later, Sanjivan emerged from the water as the winner. He was pleasantly tired. Another victory had been notched up but the price was high.

Sanjivan is a weaver of sarees. He earns ₹100 a week, and that is barely enough to make ends meet. The handloom industry is in shambles and the weavers are suffering. He took us to the weaving hut.

It is about 50 metres away. As we approached the hut, the sound of the looms was like the whoosh of a breeze in a forest. The sound came and went. And there it was: a wooden contraption with pedals for the legs and the left hand has to move a rod in a left-to-right motion constantly. This is extremely physical work. Sanjivan said that when he is training for the great race, he does not work.

So, how does he make ends meet?

“I borrow money from people,” he said. “I borrow money from my uncle here (pointing to a small, frail bare-chested man in a white dhoti, smoking a beedi). And then when things get really difficult, I sell my trophies.”

It is strange, but this shy man has an intense dedication and capacity for hard work.

Three months before the race, he begins training. For the first month it is just to relax the muscles, to make it used to long hours in the water. It is only in the next two months that the training becomes intense. Then he gets up at 6 a.m. and goes to a nearby pond and trains till 11 a.m. He returns, has his lunch and goes to sleep. At 3 p.m., he practises for two hours.

But why swim in a pond and not in the river?

“The pond has heavy water,” said Sanjivan. “The river is fast-moving. There is a current. So, swimming is easy. But in a pond, you have to use your muscles. You have to make the strokes. The water does not help you. So, four hours in the pond is equivalent to ten hours in the river.”

‘Can we see the pond?” the visitor asked.

“Sure, why not,” he replied. “But first I must get my swimming trunks.”

We returned to the house. There was a curious band of onlookers – some young, some middle-aged, and children.

There was a pervasive despair in the air. Economic difficulties had stunned the hamlet into a brooding, despairing silence. And in the wife, married to this dedicated swimmer for ten years, sadness was battling with the feeling of hope. One could not bear to see which emotion was winning. Perhaps she felt that the visitors could do something. They were, after all, from the big city.

Sanjivan carried his swimming trunks and his goggles, and with his son he took us down a narrow mud path. He had an easy stride, and a V-shaped body. He walked with a sense of dignity. Near a loom hut, he called out to a youth and asked him whether he wanted to come swimming. The youth said, “Not today, Dada. I am tired.”

Sanjivan smiled and he began to speak about his early life. “I was born here in Ramnagar, which is a village in Ranaghat. I learnt to swim from a young age. I used to watch my elders swim, and then I got into the water. I learnt on my own. What really made me interested in taking part in these races was the annual three-mile race on the Churi river. I had seen this race many times, and I wanted to take part. The first time I took part, I came second. I won the race later on, but thereafter, an interest in competitive swimming arose in me.”

It was a long walk, but for Sanjivan, it was hardly any distance at all. For the visitors, it was a time of panting and wiping perspiration off one's faces.

“I used to hear about the Mushidabad race from the radio and newspapers,” he said. “And so finally I took part in the race, but lacked the technique. I ran out of strength when there was about two kilometres left. It takes time to learn the technique, but now I can manage the distance.”

It was noon. The sun was shining brightly. The sky was clear and blue. We crossed National Highway 34, and the trucks rumbled in the silence. We crossed a field and saw the pond. On one side was a school, the Milan Bagan Shiksha Sadan. One can surely visualise the possibility of budding swimmers in that school. There is a passion for swimming in these parts.

As we neared the 50-metre pond, there was already somebody swimming there. He was swimming length after length.

“Hi, how long have you been here?” said Sanjeevean.

“Not very long,” said Babu Haldar.

“Where is your cycle?” asked Sanjivan.

“There, said Babu, pointing to a cycle parked next to a tree in the distance.

Sanjivan smiled and changed into his trunks. He said suddenly, “Do 4x50s one after the other.”

Babu smiled and went underwater. He was training for a 400-metre race in Shyamnagar, but to train at 12 noon! Perhaps the villagers do not feel the heat so much because they are out in the sun most of the day.

Sanjivan put on his dark goggles and slipped into the water. The photographer went to the edge. It was slippery, and he had a trying time keeping balance. Two swimmers guided him to a less slippery spot. Again, a crowd had gathered from nowhere.

They stared with intense attention, but at the back of the crowd a small vignette: a young man, probably 20 or 21, sat on his haunches and was talking to a small, frail boy with puffed cheeks. The boy wore a blue shirt and shorts. The young man said, “One day you should also be a big swimmer like your father.” But the child gazed at him, as children do, in their clear, unblinking gaze, that makes sinners cringe and remained silent.