Shevlin Sebastian's Blog, page 6

November 15, 2024

People who live in the shadows

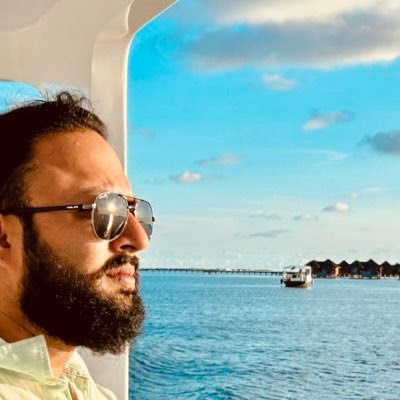

Journalist Siddharthya Roy, in his book, ‘The Company of Violent Men’, focuses on the nether world of terrorists, Maoists, fixers, spies, and people escaping from ethnic strife like the Rohingyas

By Shevlin Sebastian

In the preface, journalist Siddharthya Roy gives an indication of the people we will meet in his book, ‘The Company of Violent Men.’ They include ‘militants and refugees, clandestine agents and insurgents, reporters and wheeler-dealers — some extraordinary and some very ordinary individuals caught in circumstances that news headlines, including those of my own stories, have flattened them into convenient tropes of good and evil and us and them.’

Roy continues: ‘These violent men and women I speak of, some of them fight for faith, others fight for power. Many fight just to belong. But peel away the burqa or the badge, scratch the skin of a military officer or a mercenary, and the fears and failings that lie beneath are not so foreign from yours or mine.’

In the beginning, Roy goes to Dhaka to investigate who was behind the mayhem at the Holey Artisan cafe in Dhaka on July 1, 2016. A group of five men, carrying assault guns and machetes, carried out the attack and took diners hostage.

They belonged to the Jamaat-ul-Mujahideen Bangladesh (JMB), a home-grown outlawed Islamist group. Army commandos stormed the cafe. In the ensuing shootout, 18 foreigners died. All five assailants were shot dead.

In his search, Roy ended up in Bagmara (190 kms from Dhaka). That was where Siddique-ul Islam, who called himself Bangla Bhai (Bengal’s Big Brother) of the JMB, first set up his base.

He ruled the place with violence. Bangla Bhai forcibly collected taxes from the villagers. The JMB prohibited all non-religious gatherings. They did not allow public singing, playing sports, and plays. Women could not go out of the house without male supervision. And they held kangaroo courts where they meted out justice.

And Roy saw Musa, a victim of Bangla Bhai’s senseless violence. ‘Musa couldn’t really talk. All he could do was gurgle and squeak while froth gathered at the edges of his misshapen mouth. But he started his narrative with gusto through agitated gurgles, frothing, as his hollowed-out eyes grew big and small.

His wife, who had been standing behind the threshold to the cowshed, pulled the ghomta of her saree lower, came in and rolled up his mud-stained dhoti.’

Roy continued: ‘There were his broken legs. They were ghastly twisted twig-thin limbs with dried-up gashes of rolled back flesh.’

After a while, the government reacted. The Rapid Action Battalion moved to Bagmara. Bangla Bhai was hiding in a shed. He gave up without a fight. Authorities hanged him in 2007 along with other members of his group. But the group survives.

Thereafter, Roy went to Kutapalong in Cox’s Bazar, to meet the Rohingyas refugees who fled from Myanmar following a genocide.

While talking to the mother of a little girl called Shaheen, Roy gave you an idea of how one’s life can go topsy-turvy in a moment. The family lived in Maungdaw Township. This was near the Bangladesh-Myanmar border.

The husband ran a successful farm. The wife was a beautician who ran a beauty parlour. Shaheen was born in 2011 and then the woman had a son in 2014. Life was going on smoothly.

Then the military launched a crackdown in October 2016. It lasted for the next few months. Soon, it degenerated into a genocide. The Tatmadaw (the army) burned her husband and son in their house. Shaheen and her mother had gone to see some relatives in a neighbouring village. And so they survived.

“These men were so violent and heartless,” Shaheen’s mother said. “Like monsters.”

They had no option but to flee to Bangladesh, carrying nothing. Now Shaheen’s mother was doing haircuts and threading for the women in the camp.

In Cox’s Bazar, Roy encountered young Rohingya women at a brothel. They had entered the sex trade to survive. One of them, Inan, was a mother of four children, who had fled while her husband had stayed back at a town called Buthidaung in Rakhine State.

There was no news from him after a while. She tried sewing, but that was not enough to feed five people. But most of the men who coerced the women from the refugee camps to get into the sex trade were Rohingya men.

This is absorbing on-the-spot reporting. No sitting in an air-conditioned hotel in Dhaka and doing phone interviews. Roy goes and sees everything first-hand, meets people, and asks questions. And then writes about it.

This seems to be rare. Roy mentions how Western journalists pay local reporters in places like India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iran or Kenya to write detailed reports for handsome money. Then they would pass them off as their stories, adding their bylines at the top.

Later, after he gets a grant, Roy goes to Germany. He wanted to find out whether IS fighters could use India as a base to fuel extremism on the subcontinent. Many IS fighters sneaked in after Germany allowed the migration of 10 lakh refugees from Syria.

But he felt they would fail because unlike in West Asia, where Islam is dominant, and the topography is similar all over, in India and other South Asian countries there was a multiplicity of religions, thought processes and the lay of the land varied from place to place.

‘The marshes of the Indus-Ganges-Padma-Brahmaputra would, in time, swallow the zeal of zealots as they had done so many times in history,’ wrote Roy.

The scene now shifts to Chhattisgarh, where Roy goes deep into Maoist territory. He is keen to find out whether the Indian government was using drones to bomb the Maoists. He was also keen to interview Madvi Hidma, the legendary leader of the People’s Liberation Guerrilla Army.

Hidma had conducted many successful attacks on the security forces. However, information and access were scarce, despite many promises by various middlemen.

In a village called Orchha, he met the locals who told them their biggest enemy was not the State, the Army or Maoists, but bears and boars.

One of them said they had planted some corn in a piece of land. The harvest was about to take place within a couple of days. In the night, two young men were keeping guard. Unfortunately, one of them, Monu, had brought along two bottles of mohua, the local liquor.

One villager said, “Just before dawn, the rustling began. Monu had drunk almost all of the two bottles and was sleeping. I tried waking him up, but when he didn’t, I took my spear and threw it into the bush. I couldn’t see well — but I took a chance. Sure enough, one of the beasts squealed and started struggling while smaller ones grunted and scattered. Hearing the sound, Monu woke up with a start and, like Salman Khan, ran to fight the pierced bear. The boar gave him what he deserved. Look at him now.”

On Monu’s back, there were long scars. It ran from the back to the side of the chest.

Like Monu, others, even without getting drunk, had suffered even more grievous injuries from boars, including slashes across the face.

From a distance, many of these villages in Chhattisgarh look picturesque. But it does not seem so when you get closer.

Here is how Roy described the odour in a village where no State official or security forces had stepped foot. ‘If one wished away the shit-smeared pigs running around in the background and ignored the smell of cow dung and pig droppings, the glade was picture perfect,’ he wrote.

Here’s another description from a remote village called Metaguda.

‘A young boy had just defecated some twenty metres from where we were sitting,’ wrote Roy. ‘The pigs got into a fight over who’d eat the shit even before the boy had properly stood up. The ones who didn’t get a share of the shit cake went back to the unwashed dishes piled in a plastic tub near us and licked little bits of rice off them.’

In Metaguda, where villagers greeted Roy with a ‘Laal Salaam’, they confirmed they had been the victim of bomb attacks by drones.

“It’s been happening for three years now,” said one villager.

However, they were reluctant to show the bombing spots because the Maoists did not give permission. Roy wrote, ‘Most rebel-held areas — not just Maoists — are harsh, hegemonic and arbitrary, and not even a semblance of civil rights is maintained.’

In the end, Roy left with no one showing him any conclusive proof of the drone bomb attacks.

Roy also met with ‘N’, a Rohingya resistance fighter, at a hotel in Cox’s Bazar. And this was how the man defended his activities to Roy.

“Are we the ones killing, raping, looting, setting people’s homes alight? Or is the Tatmadaw doing that?” N said. “And what they’re doing to the Rohingya in the Arakan will be done to the Kachin in the North and the Shan in the East? The pattern is clear and the tactics are the same. A small bunch of elite Burmese sitting in the palatial offices of Naypyidaw funded by the nacro-moguls of Yangon are out to subjugate every other identity in Myanmar.

“They claim to be protecting the nation, but, in reality, they are destroying it. They’re destroying the centuries of unity different peoples had. Tearing apart the very people they vow to defend. We are patriots. And we’ve proven it time and time again. It is the Tatmadaw, which is a terrorist organisation. That too has been proven time and time again.

“The real reason the Burmese are driving us out and burning our homes and fields is because we sit on one of the world’s largest oil and gas reserves.”

Roy continued to meet all sorts of people, including fishermen who transported meth by boat from Myanmar to Bangladesh.

And in a chapter called ‘The Louts’, Roy confirmed what most of us suspected. In many of these groups fighting for various causes, there are a lot of criminals who join.

As Roy wrote, ‘Essentially, a lot of street thugs do their run-of-the-mill thuggery and pass it off as soldiering. Their banners — whether green, red, black or stripes and stars — are just flimsy covers for acts that would’ve otherwise put them in prison.’

And so it goes. This book highlights the nether world which ordinary people do not know of. Roy has to be commended for risking his life, and many times, he experienced physical discomfort and danger, but he always went to where the action was. Thanks to his experiences, he has learnt to be sceptical. It is a world that abounds in falsehoods and misinformation. But he remained tenacious and courageous in his search for the truth.

This book is an eye-opener. And a welcome one at that.

(Published in Kitaab.org)

November 10, 2024

The divine energy in human form

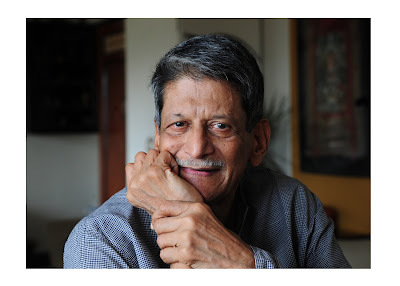

Photo 3: Author Dr. Chandra Bhanu Satpathy

Photo 3: Author Dr. Chandra Bhanu Satpathy‘Shirdi Sai Baba — An Inspiring Life’ provides an intimate glimpse of one of India’s great spiritual teachersBy Shevlin Sebastian Village woman Baijabai Kote Patil was walking among the bushes in Shirdi. She saw a 16-year-old boy sitting under a tree, cross-legged, with his eyes closed, in a deep meditation. Something about the youngster struck her. He had a divine radiance on his face. Baijabai rushed home, made some food, and placed it in front of the boy. But the youngster did not open his eyes. Finally, she asked the boy to have a little food. The boy obliged. He was none other than Shirdi Sai Baba. Later, he became one of the greatest spiritual teachers India has produced. Shirdi Sai Baba was born in the 1830s. Many versions exist regarding the identity of his parents, but because of a lack of records, none could be authenticated. Apparently, he was born in the village of Pathiri and settled in Shirdi as a boy. There was also mention that his father’s name was Abdul Sattar, but there was no conclusive proof. In 1916, the British Directorate of Criminal Intelligence (DCI) identified Sai Baba as a fakir and a Muslim. Sai Baba meditated throughout his teenage years. As a young man, he treated villagers with health problems with medicinal herbs from the nearby jungle. Many people were cured because of that. One day, a man, Nanasaheb Dengle, approached Sai Baba and told him he had no son. To get a son, Nanasaheb married for the second time. Nevertheless, there was no child. Sai blessed him. Soon, Nanasaheb’s wife got pregnant. The news about this miracle spread far and wide. Nanasaheb became a devotee. Sai Baba’s name spread to places like Mumbai, Aurangabad, Nasik and Ahmednagar. Soon, people thronged the town of Shirdi. Nationalist leader Bal Gangadhar Tilak came for Sai Baba’s darshan on May 19, 1917. Because of regular visits by nationalist leaders, the DCI maintained a presence in Shirdi. ‘Sai Baba was purely a spiritual man who tried to help the needy and sought to evolve spiritually all who came to him,’ wrote author Dr. Chandra Bhanu Satpathy. ‘However, except for the conjectures of the DCI, in their reports, there is no evidence that Shirdi Sai ever made any political predictions or advised any of his devotees on matters of politics or encouraged any sort of political activism.’ Dr. Satpathy has recounted this in his biography called, ‘Shirdi Sai Baba — An Inspiring Life’. A scholar, Dr. Satpathy, visited the Holy Shrine of Sai Baba in 1986 and became a devotee. In Shirdi, Sai Baba settled into a dilapidated mosque. It was called Dwarakamayi. This is where he met all those who came to meet him. Sometimes, he would go during the day to beg for food from his neighbours. At other times, he cooked food in a big handi over a fireplace made of mud and brick. Sai Baba would distribute the food to his devotees. On alternative nights, Sai Baba would go to sleep in the Chavadi, a sort of guesthouse which was 30 steps away. What was heartening to read was the cooperation between Hindus and Muslims at the darbars held by Sai Baba.‘In large congregations where Muslims and Hindus perform religious rites and rituals side by side, some critical differences crop up, especially regarding the technicalities of the methods of worship,’ wrote Dr. Satpathy. ‘However, in Shirdi Sai’s darbar, Hindus and Muslims stood shoulder to shoulder like loving children before a caring father. Muslims treated him as an Awliya or Pir or Paigambar, whereas Hindus adored him as Sadguru Maharaj or Avatar. Facing west, Shirdi Sai himself would recite the “Fatiha” or ask someone from the community to do so. Muslims offered him “shirni” (sweet or other dishes).’ Sai Baba wanted his devotees to break the barriers of caste, class, status, gender, religion and appearance. ‘The innumerable people who met Shirdi Sai included the rich and the poor, the educated and the illiterate,’ wrote Dr. Satpathy. ‘People of all ages, all castes, all religious affiliations, women, men, children came to him. Shirdi Sai Baba wanted his devotees to learn humility and never disparage others, regardless of their appearance and situation in life.’Once a leper came for the darshan carrying a few pedas in a packet tucked inside a dirty cloth. Sitadevi Ramachandra Tarkhad, whose husband was the manager of Khatau Mills in Mumbai, was standing nearby. She twitched her nose, as the stench from the leper was unbearable. The leper hesitated to offer the pedas. When he left, she had a look of relief on her face. Sai Baba noticed it. He called the leper back and took a peda. He asked Sitadevi to eat one too. She did so and learned her lesson too: treat people with respect, irrespective of their backgrounds. In a chapter focusing on the miracles of Sai Baba, Dr. Satpathy tells the story of a deputy collector, Nanasaheb Chandorkar, a devotee of Sai Baba. Nanasaheb was climbing Harishchandra Hill, in the Western Ghats, while on a pilgrimage. He felt thirsty. Nanasaheb prayed to Sai Baba, who was in Shirdi, 173 kms away. Sai Baba said, “Hello, Nana is very thirsty. Should we not give him a handful of water?” The devotees who were present could not understand what Sai Baba meant by this. Nanasaheb saw a Bhil tribesman pass by. He asked the tribal where water was available. The man said it was below the stone slab Nanasaheb was sitting on. When Nanasaheb removed the slab, he saw water underneath. After Nanasaheb completed the pilgrimage, he went to Shirdi. The moment Sai Baba saw him, he said, “Nana, you were thirsty. I gave you water. Did you drink?” That was when Nanasaheb realised it was because of Sai Baba’s omnipresence he could answer the distress call of his devotees. Sai Baba had a brick wrapped in a tattered piece of cloth. He rested his hand throughout the day on the brick. And when he went to sleep, he placed his head on the brick. Once when a helper named Madhu Fasle broke the brick. Sai Baba knew that the end was near. He said, “It is not the brick, but my fate has been broken into pieces.” Soon after, Sai Baba passed away on October 15, 1918. Devotees said he attained Mahasamadhi. Hindus and Muslims conducted rituals in their way. In 1922, his devotees set up the Shirdi Saibaba Sansthan Trust. This looks after the Dwarakamayi and other structures. The Trust continues to conduct all activities to this day. Approximately 30,000 pilgrims from all over the world visit Shirdi daily to pay homage to the spiritual master. It is a book with many sub-sections and photographs. You get an understanding of the life and character of Sai Baba. Some of the other subjects that Dr. Satpathy tackled included the link of Sai Baba with Sufism, the concept of reincarnation, Sai literature, and the sayings of the preacher. Here are two sayings:‘Let anybody speak hundreds of things against you. Do not resent by giving a bitter reply. If you tolerate such things, you will certainly be happy. Let the world go topsy-turvy. You remain where you are.’ ‘Those who take refuge in God will be freed from her (Maya’s) clutches, with His grace.’ (Published in kitaab.org)

November 3, 2024

Living beside an angry river

Photos: TR Premkumar. Photos by NV Jose; A view of a house from outside; residents playing chess by the banks of the Chalakudy river

Photos: TR Premkumar. Photos by NV Jose; A view of a house from outside; residents playing chess by the banks of the Chalakudy river The residents of the Moozhikulam Sala live close to nature, beside the Chalakudy River in Kerala. Then during the 2018 floods, the river water rose to a height of 25 feet inside the colony. Things have never been the same again

By Shevlin Sebastian

One of the first things that caught the eye at the Moozhikulam Sala (28 kms from Kochi) is that there is no gate. A few metres inside, there is a large banyan tree with overhanging branches. The mud paths abound in dry leaves.

There is a good deal of vegetation: peanut, banana, fig, bamboo, sandalwood and cannonball trees. Because the Sala is right next to the Chalakudy river, a gentle breeze blows all the time. The cries of cicadas and the occasional cawing of a crow punctuate the silence. A dog barks when he sees strangers. Butterflies and bees circle the petals of flowers.

TR Premkumar, 67, who grew up in Moozhikulam, was inspired by the history of the place. Maharaja Kulasekhara Varman (800-820 AD) was the ruler of the Chera kingdom. In Moozhikulam, he set up a sala or university. The university followed the Gurukula system, which focused mostly on the Vedas. The other salas that were put were in Thiruvananthapuram, Thiruvalla and Parthivapuram.

Premkumar was a maths and physics teacher at a private college. Later, he became the manager of one of the Kochi branches of DC Books, one of Kerala’s leading publishers. One day, he read ‘Living with the Himalayan Masters’ by Swami Rama.

“Swami Rama said the more possessions you can give up, and live simply, the better it is for you,” said Premkumar. “You will experience joy. It is only then that you will see nature in all its glory. That affected me. It was a turning point in my life.” Soon, Premkumar gave up his chain-smoking habit and stopped eating non-vegetarian food and imbibing alcohol.

He came up with the concept of a colony where people could live in close connection with nature, beside the Chalakudy River. He located a two-acre plot. Premkumar put a one-page advertisement about the eco-friendly project in the Malayalam Weekly of ‘The New Indian Express’ group in November 2005. Buyers purchased all 52 plots within a month.

“People became enamoured to live close to nature,” said Premkumar.

The residents belong mostly to the middle class. Most of them are those who would often visit the DC bookstore. “They are art and culturally-inclined people,” said Premkumar. Around 70 men, women and children now live in the colony.

About six families have been there from the beginning.

One of them is Pradeep Kumar, a freelance designer. Asked about the pleasures of living in the colony, Pradeep said, “I get to breathe pure air, especially in the early mornings. There is a beautiful silence mixed with the cries of birds. The neighbours are nice and friendly. There is no sound of vehicles.”

However, many single-room houses are empty. The owners live in other places. But they come on the weekends or once a month to get a respite from their work pressures.

On a Saturday evening, a couple of men are playing chess on the steps leading to the river.

“Is this the impact of India’s gold medal wins in the Chess Olympiad?” a visitor said.

One of them, in a blue T-shirt and Bermuda shorts, smiled and said, “No, we always play chess whenever we have free time.”

Today, the Sala comprises 23 ‘naalukettu’ houses, with an area of 1089 sq. ft., with three bedrooms and 29 one-bedroom houses with an area of 230 sq. ft. “It is like a studio apartment,” he said. “Two people can live comfortably. It is good for artists, writers, and those who have retired.” Interestingly, there are no walls between the houses.

The houses are made of burnt brick and mud, in the Laurie Baker style.

British-born Baker (1917-2007) was renowned for using local materials to make houses in Kerala. “There is an air pocket between the bricks,” said Premkumar. “This feature keeps the houses cool.”

There is water in the well throughout the year. Next to it, they have installed a 25,000-litre tank. So every house receives piped water. The people have a carbon-neutral kitchen. That means they do not cook the food. They eat the food raw, including the vegetables. To make it easy to digest, they smash it using the grinder. “After that, you will never get the feeling it is raw,” said Premkumar. “Believe me, it has a more delicious flavour than when you cook it.”

At a nearby patch of land, the residents grew vegetables, like brinjals, cucumber, onions, cauliflower, cabbage, potatoes and tomatoes. And all kinds of bananas. They do not use pesticides or chemicals. But now, because of erratic rainfall, it has been difficult to grow vegetables.

On asked how he has changed as a man, after being in close contact with nature. Premkumar said, “I love nature and I respect it. The problem is that man has lost touch with nature because of lifestyle and attitudinal changes. We want to exploit it as much as possible. This causes enormous damage to the ecosystem.”

Animals live in close contact with nature. That is why nature cares about them. Premkumar mentioned that not a single animal died during the landslides that have afflicted Kerala in recent times. “They always receive a warning beforehand, because they are in tune with nature,” Premkumar said. “Before the tsunami happened, many animals escaped to higher ground. And that was the case with the recent landslide in Wayanad. The animals that died were the ones that man had domesticated and kept tied up.”

The devastation caused by flooding

Life changed for Premkumar and the other residents following the massive flooding that afflicted Kerala in 2018. The waters from the Chalakudy river overflowed the banks and reached a height of 25 feet inside the colony. Only the tips of the roofs were visible. Owing to red alerts issued by the Meteorological Department, all the residents had left for distant places or the houses of relatives.

“The flood destroyed all the furniture, fridge, TV, and other items. I lost my library of 2500 rare books,” said Premkumar. The next year, water again entered the colony.

After that, in 2020 and 2021, there was a red alert because the river was almost overflowing the banks. So the people had to leave even though eventually the water did not enter the colony. “In July, this year, water entered the house at floor level,” said Premkumar.

Pradeep said the residents are yet to recover from the shock of 2018. “But we have accepted that this danger of flooding will be ever-present,” he said.

The lack of a first floor in all the houses has become a problem. There is no safe place to store anything.

Premkumar admitted that he no longer enjoyed the rain like he did as a child. “There is always a fear now,” he said. “The romance of the rains is gone.”

Some residents want to leave, but the price has crashed. So, they are stuck here. There is no guarantee that flooding will not take place in the future. So prospective buyers are reluctant to take the risk.

After 2018, farming has become a problem because of the unpredictable changes in the weather. “The rain has become unpredictable,” said Premkumar. “When it is supposed to rain, it doesn’t and vice versa.”

It is a man-made disaster, asserts Premkumar. In 2018, the 58 dams in Kerala released their water simultaneously. “Till now, the government has put no proper safety measures in place,” he said. “But there is one blessing. Because the Moozhikulam Sala is at sea level, there will be no landslides, like in Wayanad.”

Premkumar lives with his wife Sudhamani, who retired from the High Court as an office superintendent. The couple has two children. Their eldest son Vineeth is a finance manager at Apollo Hospital in Bangalore. The second son, Vivek, is a professional Carnatic singer based in Chennai. Both sons are married.

(An edited version was published in The Sunday Magazine, The New Indian Express, South India and Delhi)

October 29, 2024

A pen as sharp as a sword

Photos: Kiran Nagarkar: Photo by Tulsi Vatsal; Book cover; Author Salil Tripathi. Photo by Udayan Tripathi

Photos: Kiran Nagarkar: Photo by Tulsi Vatsal; Book cover; Author Salil Tripathi. Photo by Udayan Tripathi

In ‘Asides, Tirades, Meditations’ — Selected Essays, Kiran Nagarkar, one of the notable writers of post-Independence India, writes with an electric style on a host of topics

By Shevlin Sebastian

Author Salil Tripathi grew up in an apartment near Kemp’s Corner where Chaitra, an advertising agency, had an office. His mother would translate Chaitra’s advertising copy into Gujarati. Now and then his mother would meet the celebrated author Kiran Nagarkar, who also worked there. When Tripathi was in his twenties, he was introduced to Nagarkar. They began a lifelong friendship.

After his studies abroad, Tripathi joined the Indian Post newspaper as an assistant editor. He offered Nagarkar an opportunity to write a column. The celebrated author became a film critic for foreign films. That is probably how Nagarkar became a columnist for an English-language newspaper.

Tripathi recounted this in his introduction to the book, ‘Asides, Tirades, Meditations—Selected Essays’ by Nagarkar (Bloomsbury).

Tripathi did mention that in 2018, three women journalists accused Nagarkar of behaving inappropriately. He denied the allegations. The next year, Nagarkar died of a cerebral haemorrhage. He was 77.

Tripathi said, “I admired him as a gifted writer, a champion of freedoms, a friend who saw through the clouds clearly, who warned us about the seductive peril of majoritarianism.”

There are 36 essays in the 317-page book, clubbed under the headings, ‘Writing’, ‘Cinema’ and ‘On Society and Politics’.

In the first essay, ‘Clueless: An Occasional Writer’s Journey,’ Nagarkar states, ‘You can dictate to your characters. You can bind them hand and foot, you can take almost all decisions for them, you can make sure that they grow up the way you want them to, but the chances are that you will find in the end that they are not flesh-and-blood people but puppets and marionettes.’

This is probably the drawback of too many writers. But how to make characters come alive seems to be a gift from the Gods. Not everybody can do it.

Nagarkar also confirms the important role played by the subconscious in creative work. ‘While there is no gainsaying the primary contribution of conscious thought and planning, it is the subconscious processes of the mind and that strange chemical laboratory called “gestation” whereby at times things seem to fall into place by themselves and trickier problems get resolved.’

It was interesting to note that Nagarkar studied Marathi for the first four years of his primary education. After that, his parents enrolled him in an English-medium school. Yet, he emerged as a major English writer.

Nagarkar gained fame for his novels, including ‘Saat Sakkam Trechalis’ (tr. Seven Sixes Are Forty Three) (1974), ‘Ravan and Eddie’ (1994), and ‘Cuckold’ (1997).

For ‘Cuckold’, he won the 2001 Sahitya Akademi Award in 2001. His books were very popular in Germany. In 2012, he received the Order of Merit from Germany. Nagarkar was also a dramatist and screenwriter.

Perception abounds in his essays. In an essay regarding libraries, Nagarkar writes, ‘The most extensive and underrated library in the world, especially in the poorer countries, however, is the institution of the grandmother…she is the mother of all libraries, the largest archive of the oral tradition. In India, she is the repository of the stories from the epics, from the Panchatantra and mythology. She is the one who transmits oral history from generation to generation and is the fount of traditional wisdom.’

And he also recalled interesting encounters and conversations. Once he met a friend’s Japanese fiancée. She told Nagarkar, “I know nothing about India, except the four things that I learnt at school.”

“And what are they?” asked Nagarkar.

The woman said, “You Indians eat with your right hand, wash your hind parts with your left. You burn your women and practise untouchability.”

‘A brief, succinct and aphoristic, cultural, political and sociological history of India. A body blow,’ wrote Nagarkar.

In the essay, ‘Shiva’s Blue Throat: A Persona; Vision of the Artist’s Role’, Nagarkar compared the writing style of Nobel Laureate Gabriel Garcia Marquez with Booker Prize winner Salman Rushdie.

‘Rushdie’s joie de vivre, exuberance and deliberate punning are irrepressible,’ wrote Nagarkar. ‘His language is brilliant, flamboyant and endlessly playful ... He is a virtuoso trapeze artist whose words are always flying and caught in mid-air, doing the most incredible twists and turns. How can anyone fail to be carried away by his masterful performance? But neither can we forget that it is a performance.’

As for Marquez, Nagarkar said the language doesn’t bring attention to itself. ‘What strikes you from the very start is the richness and fecundity of his imagery, the almost infinite variety of the stories within stories he has to tell. And yet what you remember most are his characters and their fate.’

Other subjects include memories of his childhood, ageing, pretentious art films, star power in Bollywood, the city of Bombay, climate change, and ‘the fine art of intolerance.’

The book concludes with an afterword by prize-winning novelist Nayantara Sahgal. They met in 2104 and immediately became fast friends.

Nagarkar’s style is direct, clear and straightforward. These are easy-to-read essays. He always has an original viewpoint. There are many insights that are sprinkled all across the essays. Insights that make you pause and reflect and finally, get enriched by.

‘Asides, Tirades, Meditations’ is an engaging read. However, there is no mention of when and where these essays were published. Overall, this is a book worth buying. If you are a serious reader, you will not be disappointed.

(Published in Scroll.com)

October 26, 2024

Heart-breaking and disturbing

Captions: Book cover; Author Sanam Sutirath Wazir

Captions: Book cover; Author Sanam Sutirath WazirSanamSutirath Wazir’s ‘The Kaurs of 1984 — the Untold, Unheard Stories of SikhWomen’ is a razor-sharp look at the extraordinary devastation that womensuffered after the assassination of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in 1984

ByShevlin Sebastian

OnJune 4, 1984, Rachpal Singh, the secretary of militant leader Sant JarnailSingh Bhindranwale, was in a room in the Golden Temple. He was with his wifePritam and their 18-day-old son. The Army was shooting into the Temple duringOperation Bluestar.

Pritamsaid, “A flash of light would come in from the space below the doors and blindus for a few seconds, followed by the deafening sounds of bombs. I could hearthe sound of tank treads moving outside our room, proceeding towards the AkalTakht (the chief centre of religious authority among the Sikhs).”

At12.15 am on June 6, a bullet hit her baby’s back before hitting Pritam on thechest. As Rachpal bent over his wife and son, a bullet hit him on the head. Hedied instantly. Pritam lay in a pool of blood, with her dead husband beside herand her dead son lying on her chest.

ManjeetSingh, the then press secretary of the Akali Dal, saw a young man and hisinfant son killed. The mother picked up the son and placed him on his father’schest. “It’s been more than three decades now, but whenever I close my eyes,that scene comes back to me,” said Manjeet.

AuthorSanam Sutirath Wazir focuses on the suffering of Sikh women in the book, ‘TheKaurs of 1984 - the untold, unheard stories of Sikh women’. Many of whom wererape victims during the 1984 cataclysm that shook Punjab, and the riots thattook place in Delhi and other places.

TheSikh psyche was shattered because of the army’s widespread damage to the GoldenTemple. ‘Over 350 bullets riddled the dome of the Golden Temple,’ wrote Wazir.‘One bullet pierced the cushion on which the Guru Granth Sahib was placed,pushing through as many as eighty-two pages of the book itself. Most of theitems in the toshakhana (a storehouse for valuables) were destroyed….all thehandwritten hukamnamas (orders), penned by different Sikh gurus across theages, were lost as well.’

Wazirwrites with painstaking details about the damage to the Golden Temple and thehuman rights violations by the Army and the security agencies that took placethereafter. Even women and children were not spared.

Nosurprises, there was a blowback. On October 31, 1984, Prime Minister IndiraGandhi was shot dead by her Sikh guards, Beant Singh and Satwant Singh.Immediately, in Delhi, mobs, mainly orchestrated by the Congress Party, laidsiege to the Sikh community.

AtBlock 32 in Trilokpuri, East Delhi, local leader Rampal Saroj, accompanied by agroup of men, asked resident Darshan Kaur where her husband Ram Singh was. She saidhe had gone out with his brother.

Themen did not believe her. They broke down the main door and barged into thehouse. Ram Singh was hiding in the kitchen. ‘They dragged him out by his hair,’wrote Wazir. ‘They placed a quilt and tyre over his head, doused him in oil andthen set him ablaze. Ram Singh was nearly burnt to death; he later succumbed tohis injuries.’ In the end, all the Sikh men who were present in Block 32 onthat day were killed. There were 275 widows across 180 homes.

Themen committed rape against elderly, middle-aged women, and teenage girls.Darshan said a young girl of 15 returned, naked and bruised. She had been rapedmany times, by some as old as her grandfather.

Chapterby chapter Wazir tells harrowing tales about what happened to the Sikh women,in places like Sultanpuri, Raj Nagar and Mukherjee Nagar. Their lives weredestroyed. Very few have recovered. As one woman, Satwant Kaur, said, “Thosemonsters had scarred me for life.”

Astoundingly,many women recalled that the rioters used white powder on the victims. Wazirsaid that it could have been white phosphorus. The powder burns human flesh andcatches fire when exposed to the air.

Theviolence spread beyond Delhi. In Hondh Chillar, in the Rewari district inHaryana, a mass grave of Sikhs was discovered in 2010.

However,India has not stepped back from this destructive route. Since 1984, accordingto a Google search, there have been over 70 riots in different parts of India.The latest was the Haldwani riots in Uttarakhand on February 9, 2024.

Waziralso focuses on women who became militants and became part of pro-Khalistangroups as well as the lives of widows in refugee camps.

Thisbook is a very valuable document. It heightens awareness of the suffering thattakes place. Or as feminist publisher Urvashi Butalia said on the cover, thebook is ‘graphic, disturbing and searing.’

Weneed to read it, get appalled and vow to ourselves that as a people, we shouldnever allow such events to happen again.

(Anedited version was published in The Sunday Magazine, The New Indian Express,South India and Delhi)

October 24, 2024

Awakening our sensitivity

Photos: Pramod Thomas and his family; Pramod's friend, the journalist Jobin Augustine, who passed away in May, 2012. A condolence meeting was held at the Ernakulam Press Club

Photos: Pramod Thomas and his family; Pramod's friend, the journalist Jobin Augustine, who passed away in May, 2012. A condolence meeting was held at the Ernakulam Press Club

Journalist Pramod Thomas focuseson the everyday moments of life, as well as the tragedies that afflict societyin his book of poems

By Shevlin Sebastian

Pramod Thomas was my formercolleague in The New Indian Express, Kochi. He was and remains an ace businessjournalist. Today, he works for an UK-based media group.

But what nobody will realisewhen you meet him, with his focused, professional attitude, is that he is asensitive poet. At spare moments, which I am sure, is rare since he has a wifeand two daughters, Pramod writes poems. This is his way of battling stress andthe lack of meaning in life that afflicts everybody now and then.

In 2017, he published his firstbook of poetry, ‘A Shoe Named Revolution’. Now, he has published his secondbook, ‘Biography of a Couch Potato’. It comes as no surprise that he hasdedicated it to his two daughters, Ayaana and Ahaana.

It is also dedicated to ‘thosewho find comfort in the quiet moments and beauty in the ordinary; To the oneswho see poetry in everyday life — in the sunrise, the rain, a stranger’s smileor a fleeting thought. May these poems be a companion on your journey, offeringsolace, reflection, and a sense of belonging.’

When you realise how conflict(Ukraine/Gaza/Lebanon) has been dominating the news for over two years, thefirst poem, ‘Eulogy of the Unborn’, is about war:

‘Do not stare at me, for I amdead

Don’t cry for me,

Cry for my child, unborn.

Her eyes shattered

In the rubble,

Only I can see a rainbow,

A colourless one though.’

The book comprises 21poems.

One poem, ‘Blood Butterfly’,draws inspiration from a 13-year-old girl in Tamil Nadu who tragically lost herlife during Cyclone Gaja. Her family forced her to stay alone in a barn becauseshe was having her periods.

Here is the concludingverse:

‘While trying to pleasegods,

We become less human.

Forgive us,

In the name of a zillionunborn.

Now, we have blood on ourhands.’

Pramod dedicated another poem,‘Echoes of a Lost Spring’, to his journalist friend, Jobin Augustine, 28, whopassed away in May, 2012. A sub-editor with the Madhyamam Daily newspaper inKochi, Jobin fell from a private bus, got crushed under its wheels, and died.He was on his way to his home at Ramapuram.

The poem, ‘A Poetic Flower’ isdedicated to the Kerala poet, A Ayyappan. Pramod is a fan of his work. Ayyappanwas found unconscious on October 21, 2010, in front of a theatre inThiruvananthapuram.

The local people informed thepolice, who took the poet to the government hospital. Nobody, including thepolice, had recognised him. A bachelor, Ayyappan was 61 when he died. Peopleknew him as the ‘Icon of Anarchism’ of Malayalam poetry.

Pramod writes:

‘The street was not deserted

There were a few people,

But none recognised thepoet;

They mistook him for adrunkard,

Considering him a badomen.’

Pramod concludes the poem bysaying:

‘In a city far away, manyawaited the poet,

Eager to honour him for hispoems,

An event was ready to welcomehim,

Ears eager to listen to hisverses,

But life had other plans.’

‘The City of Sins’ focuses onthe rape and murder of a 31-year-old trainee doctor at the RG Kar MedicalCollege and Hospital in Kolkata on August 9, 2024.

‘Kolkata, hang your head inshame,

Retreat to your ugly thoughts,and end yourself.

How can you raise your headnow?

There is blood on yourhands,

Your dark streets can never bethe same again.’

At the end of the poem, Pramodstates: ‘Sexual violence against women is a widespread problem in India — anaverage of nearly 90 rapes a day was reported in 2022 across the country.’

In the title poem, ‘Biography ofa Couch Potato’, Pramod says:

‘There is no endgame in thisdull drama,

You live the same life everyday, year after year.

When you’re glued to thescreen,

Your comfort zone embraces you,

And there’s no goingback.’

However, the book is not allgloom and doom.

Pramod writes about lovetoo.

‘There is no boundary to my lovefor you;

I am connected to you,

Like a train to its track,

A thunder to the cloud.

And a chalk to theblackboard.

You are the last drop of myrain,

The final drop in my blood bank,

The last atom in my body,

The last prisoner in the world’slast prison.’

One gets the feeling his wifeStephena is going to be moved to read this.

Other poems include dealing withthe suffering of a writer who has received rejection, the birth of a child to agay couple, which is overseen by a lesbian nurse, American Vice President KamalaHarris, wokeism, the Wayanad landslide tragedy, a Filipino woman who donned amermaid suit and performed in a large aquarium at Kochi, and the biography of astone.

The poems reveal Pramod’ssensitivity to human suffering and emotional pain. He writes from his heart.And so it affects us who read these poems. It makes us pause in our hecticdaily life and activates the sensitive aspects of our being. In short, thesepoems humanise us.

‘Couch Potato’ is nominated forthe 21st Century Emily Dickinson Award.

October 21, 2024

Life on the trains

For 57 years, KJ Paul Manvettam has been travelling daily by train from his home in Kuruppanthara to Ernakulam, a distance of 43 kms, and back. He talks about his experiences and also about his activism to double tracks, improve services and ask for new trains By Shevlin Sebastian KJ Paul Manvettam gets up every day at 5 a.m. He does not need an alarm. Whatever time he goes to sleep, which is mostly at midnight, he gets up on time every day. He goes through his morning routine of getting ready. At 6.40 a.m. his wife prepares a breakfast of idli or dosa. Then his son Pritto drives Paul to the station. Pritto is an optometrist. He works at his father’s shop, Polson’s Opticals, in Kochi. He comes later by bus. Paul has been travelling on trains every day, except Sundays, for 57 years. His journey is from Kuruppanthara to Ernakulam, a distance of 43 kms. At 7.20 a.m., the Palaruvi Express arrives at the station. It starts at Tuticorin and travels to Palakkad, a distance of 537 kms. Kuruppanthara is the 28th stop. Paul gets into any of four general compartment bogies. Despite the crowd, someone always offers Paul a seat because he is 75 years old. “The train is punctual 95 percent of the time,” said Paul. “But this is because they have now converted the stretch into double tracks.” Earlier, the journey from Kuruppanthara to Ernakulam was on a single track. So, the train would have to stop at stations so that other trains on the opposite track could go past. Inevitably, the train was late. Paul carries a monthly season ticket. In 1967, the price was Rs 18. Now it is Rs 180. “The daily charge for me for going and coming is Rs 6 only,” he said. “And if the discount for senior citizens is re-introduced, it will almost be free.” Asked whether the scenery had changed from the window over the years, Paul said, “Yes, there were a lot of trees and forests when I started. There were paddy fields where pelicans would use their long beaks to catch worms in the water. The houses were small. I remember one such house, near Mulanthuruthy, which belonged to a senior IAS officer.” Now, there are a lot of villas where there used to be paddy fields. The birds have vanished. “I wonder whether these people have any guilt about what they have done to the fields,” he said. “Many small hills have become denuded because of the quarrying of mud for house building and levelling of land. I feel sad.”Asked how fellow passengers have changed over the years, Paul said, “There was a lot of conversation in those days on several topics. People would play cards. It was usually rummy. There was a convivial feeling. It was lively. We had good relationships with each other.” But nowadays, when people get in, they immediately fixate on their mobile phones. A conversation can only be started when Paul taps them on the shoulder. He said it takes time for people to become friends with each other. Nowadays everybody can collect information on the mobile phone. “You don’t need to ask anybody whether the train is running late,” he said. “You can check it on the app.”Despite this, for the past 39 years, Paul has bought the handbook, ‘Indian Railways - Trains at a Glance’. The latest edition of the handbook, from October 2023 to June 2024, is priced at Rs 100 and contains 450 pages. “In the earlier days, everybody would consult it,” said Paul. Paul closes the shop at 7.30 p.m. He takes the 8 pm train from Nilambur to Kottayam. Paul gets down at Kuruppanthara at 9 pm. When he reaches home, it is 9.30 p.m. He has a bath, followed by dinner. Then he chats with his wife, Annamma, before he goes to sleep. The couple has two boys and a girl. Railway Activism Paul came to the attention of many in Kerala when, on January 3, 1997, he and his fellow passengers took out a jeep rally from Chengannur station to Ernakulam. They were demanding the doubling of the railway tracks along the 114 km route from Kayamkulam to Ernakulam. The group stopped at every station on the route. Many Parliament and Assembly legislators offered their support. The media provided extensive coverage. “It was the first time somebody had launched a campaign on this issue,” said Paul. It took three years before the Railways gave the nod. In May 2022, the Railways completed the doubling of the entire stretch. It was a wait of 25 years. For the past several years, at least once every three or six months, Paul, as State President of the All Kerala Railway Users Association meets senior officials, like the Division Railway Manager and the Chief Operations Manager, apart from officials from the Chennai office, at the Divisional Railway Users Consultative Committee meeting at Thiruvananthapuram. Around 20 people will be present. They will include representatives of merchant associations, disabled associations, chambers of commerce and passenger associations. All of them offer suggestions on ways to improve the railway’s efficiency. Besides that, Paul meets officials at the Ernakulam Junction railway station. A year ago, he asked officials whether the newly launched Vande Bharat train could have its ‘crossing’ at Mulanthuruthy (18 kms from Kochi) shifted to Tripunithura (10 kms from Kochi). The benefit, he said, is that a lot of commuters can get down at Tripunithura. “From there, they can get buses and metro trains to various destinations,” said Paul. The officials politely said they would look into it. “It is difficult for the Railways to make changes quickly,” said Paul. “A passenger thinks, ‘Why should it be hard?’ But the Railways are dealing with over 300 trains at a time. If it can be implemented easily, they will do it. No official wants to cause problems for the public. I am sure of that.” Paul also successfully campaigned, with the help of Parliament legislators from Kerala, for the Palaruvi Express to have stops at Ettumanoor and Angamaly. Earlier, he had campaigned for a stop at his hometown of Kuruppanthara and Vaikom. “I have always been polite in my requests,” he said. “I never raise my voice. And I have never lost my cool. As a result, the officials are receptive to my suggestions. I would like to add that the requests should be reasonable.” People have complained about the bogies being overcrowded. “Yes, I agree. Because train travel is the cheapest, there are so many passengers,” said Paul. “There is a limit for the Railways to increase bogies. The platforms cannot accommodate the extra bogies. They added four additional bogies to the Palaruvi Express. Still, there is no place to sit.” Paul campaigned for an 8 pm train from Ernakulam to Kottayam for many commuters. This happened on July 1, 1995. In early 2000, when Union Railway Minister Bangaru Laxman came to the Ernakulam Junction railway station for an event, Paul presented a memorandum requesting the doubling of tracks from Ernakulam to Tripunithura, as a beginning. Also present were the General and Divisional Manager. When Bangaru asked Paul about the benefits of doubling only 10 kms, Paul said, “Sir, because Tripunithura is a single line, many trains, including goods trains and oil tankers, get held up.”Bangaru conferred with the senior officials. They all agreed that trains have experienced delays. Immediately, he wrote a special note recommending it. They also submitted a petition to senior BJP leader O Rajagopal about this. In 2001, Rajagopal became the Minister of State for the Railways. Immediately, he campaigned to set aside money in the budget to begin work on track doubling. The rest is history. Asked about the character of Malayali passengers, Paul said, “They are comfortable, tolerant and accept difficulties. But there is a minority, who complain through their social media posts about deficiencies. They end up influencing the other passengers.” But Paul said the people know the railways are the best and cheapest way to travel, especially for elderly and disabled people.“Bus travel is so cramped,” said Paul. “You can get stuck in traffic jams. You can’t move around. And there is no possibility of using a washroom unless the bus stops somewhere. And the ticket charge can be as high as Rs 80. As for the train, it is Rs 3. Also, on the train, you can eat comfortably. Many people bring their breakfast in tiffins and have it on the train. It is just like being at home.”(An edited version was published in The Sunday Magazine, The New Indian Express, South India and Delhi)

For 57 years, KJ Paul Manvettam has been travelling daily by train from his home in Kuruppanthara to Ernakulam, a distance of 43 kms, and back. He talks about his experiences and also about his activism to double tracks, improve services and ask for new trains By Shevlin Sebastian KJ Paul Manvettam gets up every day at 5 a.m. He does not need an alarm. Whatever time he goes to sleep, which is mostly at midnight, he gets up on time every day. He goes through his morning routine of getting ready. At 6.40 a.m. his wife prepares a breakfast of idli or dosa. Then his son Pritto drives Paul to the station. Pritto is an optometrist. He works at his father’s shop, Polson’s Opticals, in Kochi. He comes later by bus. Paul has been travelling on trains every day, except Sundays, for 57 years. His journey is from Kuruppanthara to Ernakulam, a distance of 43 kms. At 7.20 a.m., the Palaruvi Express arrives at the station. It starts at Tuticorin and travels to Palakkad, a distance of 537 kms. Kuruppanthara is the 28th stop. Paul gets into any of four general compartment bogies. Despite the crowd, someone always offers Paul a seat because he is 75 years old. “The train is punctual 95 percent of the time,” said Paul. “But this is because they have now converted the stretch into double tracks.” Earlier, the journey from Kuruppanthara to Ernakulam was on a single track. So, the train would have to stop at stations so that other trains on the opposite track could go past. Inevitably, the train was late. Paul carries a monthly season ticket. In 1967, the price was Rs 18. Now it is Rs 180. “The daily charge for me for going and coming is Rs 6 only,” he said. “And if the discount for senior citizens is re-introduced, it will almost be free.” Asked whether the scenery had changed from the window over the years, Paul said, “Yes, there were a lot of trees and forests when I started. There were paddy fields where pelicans would use their long beaks to catch worms in the water. The houses were small. I remember one such house, near Mulanthuruthy, which belonged to a senior IAS officer.” Now, there are a lot of villas where there used to be paddy fields. The birds have vanished. “I wonder whether these people have any guilt about what they have done to the fields,” he said. “Many small hills have become denuded because of the quarrying of mud for house building and levelling of land. I feel sad.”Asked how fellow passengers have changed over the years, Paul said, “There was a lot of conversation in those days on several topics. People would play cards. It was usually rummy. There was a convivial feeling. It was lively. We had good relationships with each other.” But nowadays, when people get in, they immediately fixate on their mobile phones. A conversation can only be started when Paul taps them on the shoulder. He said it takes time for people to become friends with each other. Nowadays everybody can collect information on the mobile phone. “You don’t need to ask anybody whether the train is running late,” he said. “You can check it on the app.”Despite this, for the past 39 years, Paul has bought the handbook, ‘Indian Railways - Trains at a Glance’. The latest edition of the handbook, from October 2023 to June 2024, is priced at Rs 100 and contains 450 pages. “In the earlier days, everybody would consult it,” said Paul. Paul closes the shop at 7.30 p.m. He takes the 8 pm train from Nilambur to Kottayam. Paul gets down at Kuruppanthara at 9 pm. When he reaches home, it is 9.30 p.m. He has a bath, followed by dinner. Then he chats with his wife, Annamma, before he goes to sleep. The couple has two boys and a girl. Railway Activism Paul came to the attention of many in Kerala when, on January 3, 1997, he and his fellow passengers took out a jeep rally from Chengannur station to Ernakulam. They were demanding the doubling of the railway tracks along the 114 km route from Kayamkulam to Ernakulam. The group stopped at every station on the route. Many Parliament and Assembly legislators offered their support. The media provided extensive coverage. “It was the first time somebody had launched a campaign on this issue,” said Paul. It took three years before the Railways gave the nod. In May 2022, the Railways completed the doubling of the entire stretch. It was a wait of 25 years. For the past several years, at least once every three or six months, Paul, as State President of the All Kerala Railway Users Association meets senior officials, like the Division Railway Manager and the Chief Operations Manager, apart from officials from the Chennai office, at the Divisional Railway Users Consultative Committee meeting at Thiruvananthapuram. Around 20 people will be present. They will include representatives of merchant associations, disabled associations, chambers of commerce and passenger associations. All of them offer suggestions on ways to improve the railway’s efficiency. Besides that, Paul meets officials at the Ernakulam Junction railway station. A year ago, he asked officials whether the newly launched Vande Bharat train could have its ‘crossing’ at Mulanthuruthy (18 kms from Kochi) shifted to Tripunithura (10 kms from Kochi). The benefit, he said, is that a lot of commuters can get down at Tripunithura. “From there, they can get buses and metro trains to various destinations,” said Paul. The officials politely said they would look into it. “It is difficult for the Railways to make changes quickly,” said Paul. “A passenger thinks, ‘Why should it be hard?’ But the Railways are dealing with over 300 trains at a time. If it can be implemented easily, they will do it. No official wants to cause problems for the public. I am sure of that.” Paul also successfully campaigned, with the help of Parliament legislators from Kerala, for the Palaruvi Express to have stops at Ettumanoor and Angamaly. Earlier, he had campaigned for a stop at his hometown of Kuruppanthara and Vaikom. “I have always been polite in my requests,” he said. “I never raise my voice. And I have never lost my cool. As a result, the officials are receptive to my suggestions. I would like to add that the requests should be reasonable.” People have complained about the bogies being overcrowded. “Yes, I agree. Because train travel is the cheapest, there are so many passengers,” said Paul. “There is a limit for the Railways to increase bogies. The platforms cannot accommodate the extra bogies. They added four additional bogies to the Palaruvi Express. Still, there is no place to sit.” Paul campaigned for an 8 pm train from Ernakulam to Kottayam for many commuters. This happened on July 1, 1995. In early 2000, when Union Railway Minister Bangaru Laxman came to the Ernakulam Junction railway station for an event, Paul presented a memorandum requesting the doubling of tracks from Ernakulam to Tripunithura, as a beginning. Also present were the General and Divisional Manager. When Bangaru asked Paul about the benefits of doubling only 10 kms, Paul said, “Sir, because Tripunithura is a single line, many trains, including goods trains and oil tankers, get held up.”Bangaru conferred with the senior officials. They all agreed that trains have experienced delays. Immediately, he wrote a special note recommending it. They also submitted a petition to senior BJP leader O Rajagopal about this. In 2001, Rajagopal became the Minister of State for the Railways. Immediately, he campaigned to set aside money in the budget to begin work on track doubling. The rest is history. Asked about the character of Malayali passengers, Paul said, “They are comfortable, tolerant and accept difficulties. But there is a minority, who complain through their social media posts about deficiencies. They end up influencing the other passengers.” But Paul said the people know the railways are the best and cheapest way to travel, especially for elderly and disabled people.“Bus travel is so cramped,” said Paul. “You can get stuck in traffic jams. You can’t move around. And there is no possibility of using a washroom unless the bus stops somewhere. And the ticket charge can be as high as Rs 80. As for the train, it is Rs 3. Also, on the train, you can eat comfortably. Many people bring their breakfast in tiffins and have it on the train. It is just like being at home.”(An edited version was published in The Sunday Magazine, The New Indian Express, South India and Delhi)

October 3, 2024

How history has shaped the Indian mind

Rahul Bhatia’s book, ‘The Identity Project — The Unmaking Of a Democracy’ through narrative, anecdote, research and on-the-spot reporting explains why India is the way it is today

By Shevlin Sebastian

In the book’s introduction, author Rahul Bhatia talks about an aunt’s partner who told him to be careful about Muslims. ‘They don’t see themselves as Indians,’ the man said. “Jaat hi alag hai (they are made of something different).” His aunt butted in, “You don’t know. They’re savages. I’ve seen what they are capable of.” Two friends told Rahul about the howling of the ‘mozzies’ minarets near their home.

Disturbed, Bhatia decided to investigate what had happened. He did six years of research and met all kinds of people. The result is a memorable 449-page book, ‘The Identity Project — The unmaking of a democracy’.

The book begins with a protest by the faculty and teachers of the Jamia Millia Islamia University. It was against the Citizenship Amendment Act. Parliament passed this act on December 11, 2019.

The police entered the old library at the Ibn Sina block. Then they began wielding their plastic sticks. ‘Squeezed in the crowd [student] Minhajuddin made for the exit,’ wrote Bhatia. ‘As Minhajuddin went by, he felt a whip and a burning pain across his left eye that almost made him faint. Although he did not know it then, the attack rendered his eye useless. It may have been his beard, he said later, that got the police’s attention. He wore it long then.’

Bhatia describes the students’ reaction to the CAA at Mumbai and Ambedkar University in Delhi. Most students were fearful. ‘They knew the police were using new technologies to identify dissenters,’ said Bhatia. ‘They had seen unidentified drones flying over protests, taking pictures, picking out dissenters and saw police point cameras at crowds. Their data was being transmitted to an unknown location, for unknown purposes.’ No surprises then that someone had scribbled, ‘Hindutva Gestapo everywhere.’

Bhatia wrote about the Shaheen Bagh protests. And the 2020 Delhi riots. At the police station at Gokulpuri, a photographer, Meherban asked Bhatia to walk from the building to a few Muslim-owned body parts and tyre repair shops. It took 91 steps.

Meherban said Hindu gangs set the shops on fire in February 2020. ‘It had been a slow-burning, with men returning in waves to set fire to one more shop, one more vehicle, one more tyre,’ recalled Meherban. ‘Despite the calls, no police had traversed the ninety-one steps.’

And in a chapter called Testimony, a mob gathers in front of a lane, shouting ‘Jai Shri Ram’ slogans. They also shouted hateful slogans, like ‘Kill the mullahs’, ‘Make the circumscribed run away’ and ‘Burn down their houses’. Then they moved into the lane and attacked all the Muslim houses.

Nisar, who built a successful business in textiles over decades, lost everything in one night.

But there was apathy everywhere for their suffering. Grievously injured Muslims would arrive at the Lok Nayak government hospital. The woman at the admissions desk said, “Didn’t you think before firing bullets and throwing stones? Do you have no shame?”

And when the people accompanying the injured said, “Does that mean you were there? You’re sitting in a hospital and accusing him of doing those things. So you were there too?”

But the woman did not budge. And the patients had to be taken elsewhere.

Despite pressure and threats, Nisar decided to testify against those who had pillaged and burnt his home. He had to attend the case at a sessions court in the Karkardooma court complex in East Delhi. Bhatia attended it and wrote a brilliant on-the-spot report about what happens inside a court. You will burst out laughing and after that pull your hair in frustration too. Finally, you will spread your hands out in exasperation as you watch the judge at work. It seems like things are moving ahead, but that is an illusion. Owing to endless delays and postponements, it took two years for Nisar to testify for the first time in front of the judge. No wonder people say the process is torture.

In the next section, called A New Country, the author traces the rise of the Arya Samaj in the 1850s. Dayanand Saraswati, a philosopher and preacher (1824-83), was the founder. Dayanand railed against the bloated idol worship of Hinduism. He spoke against child marriage and widow remarriage. And it was Dayanand who propagated the protection of the cow through a slim book, ‘Gokarunanidhi — Ocean of Mercy for the Cow’. This concept caught fire. The meetings on cow protection were attended by 5000 people. Soon, cow protection societies sprung up.

There was strife between Hindus and Muslims about it. In May 1894, the Allahabad-based newspaper, the ‘Pioneer’, reported that, for generations, the rival sects (Hindus and Muslims) had lived in harmony. But now the strain was showing. Sometimes, there was violence instigated by the cow protection societies.

‘Large numbers of Hindus armed with sticks and knives attacked smaller groups of Muslims with guns,’ wrote Bhatia. In 1882, there was a full-fledged riot in Salem. Many Muslim homes were burnt, according to the ‘Pioneer’. The mob razed a mosque. Along with the Arya Samaj, the Hindu Maha Sabha came into being in 1915.

In later years, a prominent Mahasabha official was a cataract surgeon named Balakrishna Sheoram Moonje. He worshipped Italy’s leader Benito Mussolini. Moonje wanted to set up a military school, like the way Mussolini had done in Italy. In the paperwork for the school, which was set up in 1937, Moonje stated that if the school is dissolved, the assets should go to Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). A Marathi-speaking Brahmin, Dr. Keshav Baliram Hedgewar, had set up the RSS in 1925.

Bhatia traces the career of Hedgewar and comes up with interesting statistics. Between February 1926 and August 1927, there were 52 riots. Seventeen riots occurred because of processions and music played outside places of worship. Total dead: 200. Injured: 1700.

In the riots in Calcutta, from April to May 1920, 113 died, and the injured were 1070. ‘Moonje and other stalwarts of the movements to unite Hindus travelled to Calcutta shortly after the unrest had subsided,’ wrote Bhatia. ‘The injured had barely healed, and tempers barely cooled, when Moonje delivered an incendiary speech about the ongoing “civil war” between Hindus and Muslims.’

When Bhatia described the chaos and the bloody riots after the partition of India in 1947, he quoted Prime Minister Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru: ‘There is a limit to killing and brutality and that limit has been passed during these days in North India. A people who indulge in this kind of thing not only brutalise themselves but poison the environment…individual attacks continue in odd places by the kind of persons who are normally quiet and peaceful. Little children are butchered in the streets. The houses in many parts of Delhi are still full of corpses. These corpses are being discovered as people go inside and find dead bodies which have been lying there for many days.’

Later, Nehru stated that the RSS and Sikhs mostly fomented this organised violence.

Other subjects include the experiences of Partha Banerjee, who was a loyal RSS worker. However, he left the organisation in 1981. Banerjee wrote a book called ‘In the Belly of The Beast: The Hindu Supremacist RSS and the BJP in India, An Insider’s View’.

He told Bhatia that the RSS foot soldiers had ‘sub-par intelligence. Ninety to ninety-five percent of its members were practically brainless idiots. They dumb you down so that you are not allowed to think, question or challenge. You just blindly follow directives from leaders.’

Bhatia noted that in the RSS magazine, ‘Organiser’, a surgeon, wrote that if a woman had a contraceptive pill, she would grow a beard. ‘An opinion held in 1949 was likely to be held in the year 2023,’ wrote Bhatia.

Bhatia also wrote about the President of the Bharatiya Janata Party Lal Krishna Advani’s Rath Yatra in September 1990. The aim: to build a temple where the Babri Masjid stood. It was believed to be Lord Rama’s original birthplace. One of the rallying cries was: ‘Just one more push, break the Babri mosque’.

As the yatra proceeded from the Somnath Temple in Gujarat, deaths began occurring owing to inflamed rhetoric. On October 27, 52 were killed in Jaipur. On October 29, 88 died in Bijnor, Rampur, Lucknow, Howrah and Ranchi. By October 30, the death toll reached 67 in Colonelganj and Hyderabad.

And the story went on….

This book will shake you up. It is a must-read. The author writes it in a straightforward manner. So, it is easy to read. People will get an idea of how India is today, thanks to events that took place during the past 150 years. The need to know the past is imperative.

As Spanish-American philosopher George Santayana said, in his most famous and oft-repeated aphorism, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

(Published in kitaab.org)

September 20, 2024

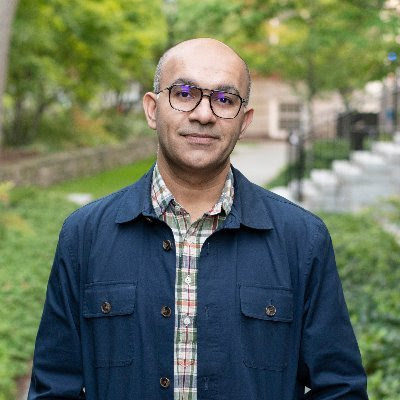

‘How Long Can the Moon Be Caged?’ by Suchitra Vijayan and Francesca Recchia is an examination of how the Indian state stifles dissent

Photos: Authors Suchitra Vijayan and Francesa Recchia

By Shevlin Sebastian

The book, ‘How Long Can the MoonBe Caged?’ (Voices of Indian Political Prisoners) by Suchitra Vijayan andFrancesca Recchia begins with a quote from the book, ‘The Gulag Archipelago’ byRussian literary great Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn:

‘At no time have governmentsbeen moralists.

They never imprisoned people orexecuted them for having done something.

They imprisoned and executedthem to keep them from doing something.’

And the authors prove this inchilling, frightening and alarming detail.

As Vijayan and Recchia stated,‘Political prisoners challenge existing relations of power, question the statusquo, confront authoritarianism and injustice; they stand with thedisenfranchised. Theirs is a ‘thought’ crime: the crime of thinking, acting,speaking, probing, reporting, questioning, demanding rights, defending theirhomes, and, ultimately, exercising citizenship.’

The state’s response: widespreadarrests and incarcerations. Even illegal bulldozing of homes. One of theauthors’ research colleagues, student activist Afreen Fatima’s house in UttarPradesh, was demolished by the authorities on June 10, 2022.

The first chapter, ‘A Season ofArrests’ chronicled in a timeline, from May 9, 2014, to April 17, 2024, themany arrests, temporary releases and rearrests of many activists, poets,fact-checkers, journalists, lawyers, social workers, intellectuals and membersof the Dalit community. It came to 41 pages.

It also chronicled the judicialfight waged by these people, while the government continued to amend laws togive even more unfettered power to the security agencies. Far too many times,the courts have sided with the government.

Incidentally, authors Vijayanand Recchia took the book’s title from a sentence that activist Natasha Narwalsent in a letter from jail. Narwal had been incarcerated for protesting againstthe Citizen Amendment Act (CAA).

In unflinching detail, the bookchronicles the arrest of academician GN Saibaba, who was in a car.‘Plainclothes police from Gadchiroli dragged the driver out, then assaulted,blindfolded and kidnapped Saibaba from the [Delhi] university campus in broaddaylight,’ wrote the authors. ‘No warrant was issued, and he wasn’t allowed tocall his wife or lawyer.’

For those who don’t know,Saibaba is 90 percent physically disabled and needs a wheelchair to movearound. And a district judge, despite scant evidence, did not give him bail.During his first 14 months in prison, Saibaba’s health deteriorated, his lefthand became paralysed and he had to be taken to hospital 27 times.

‘The vast power granted underthe UAPA [Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act] and the regimes of impunity itoffers have fundamentally remade what it means to disagree with the Indianstate,’ wrote Vijayan and Recchia. ‘The UAPA essentially reversed criminal lawby shifting the burden of proof from the prosecution to the defence and makingit illegal to hold certain political beliefs, especially those that questionthe Indian state.’

Tragically, Saibaba joins a longlist of activists and politicians like Binayak Sen, Soni Sori, GaurChakraborty, and Kobad Ghandy, who have been falsely charged under UAPA. Butthe authors state that for every activist whose name is remembered, and theircase reported, hundreds disappear unknown.

Suchitra and Francesca talk atlength about the notorious Bhima Koregaon case, where 16 activists, teachers,intellectuals, university professors, writers, and lawyers were arrested andcharged with arms smuggling, for allegedly helping Maoists, and having a plan tokill Prime Minister Narendra Modi, apart from waging war against the state.

They include Arun Ferreira,Sudha Bharadwaj, Varavara Rao, Vernon Gonsalves, Sudhir Dhawale, Mahesh Raut,Anand Teltumbde, Gautam Navlakha, Hany Babu, Sagar Gorkhe, Ramesh Gaichor,Jyoti Jagtap, Rona Wilson, Surendra Gadling, Shoma Sen, and Fr. StanSwamy.

But the case against them hasbeen flimsy. As the authors write, ‘First, information asserted withoutevidence; second, tampered evidence presented as a fact of complicity. Aforensic report issued by [US-based] Arsenal Computing found that Rona Wilson’scomputer was compromised for over 22 months and the attack was intended for tworeasons: surveillance and planting incriminating documents using Netwire, aremote malware infrastructure.’

The Delhi riots

The authors also focus on thesix-day Delhi riots that began on February 23, 2020. BJP leader Kapil Mishraprovided the impetus by stating that the police should clear the roads withinthree days of protesters against the CAA. Otherwise, he would act.

The riots began soon after.‘Mobs roamed the streets, unchallenged by the police in the days following theriots: an inferno unleashed in the heart of the nation’s capital,’ wrote theauthors. ‘The perpetrators dumped bodies and severed limbs into open drains,and bloated bodies were fished out of the gutter in the aftermath of thepogrom.’

A list of names had beenpublished in the book of those who had died. Out of 53 people, 40 are Muslims,while the rest are Hindus.

In an extraordinary twist, thepolice accused those who were the victims of having inflicted the violence.‘The Delhi police claimed Muslims had targeted their own communities,properties, and people, killed fellow Muslims, and burnt down mosques toprotest a discriminatory act directed towards their communities,’ said Vijayanand Recchia. ‘In one instance, the police arrested an imam for burning down themosque where he used to preach. He had been the one to file a complaint withthe police.’

One of the accused was KhalidSaifi. Once, Saifi’s wife, Nargis, took her eldest son to a court hearing. Whenthe boy saw his father, he reached out to touch his father’s arm. But apoliceman violently pushed the boy away, citing security reasons. The son brokedown. Later, he told his mother, “How can I be a danger to my father?”

Nargis thought, ‘Who is going toanswer this?’

But there is a streak ofsunlight and hope that penetrates this numbing darkness when the authors talkabout ‘a community in resistance’. They write about people who are in the samestruggle to uphold individual and human rights as well as democracy.

And whenever the authors met thefamilies of political prisoners or former prisoners, there was a longdiscussion on the status of other prisoners and their families and their communities.Inadvertently, Vijayan and Recchia became ‘carriers of information in thiswider network of people, who may or may not have met before, but who are nowintimately connected by a shared destiny.’

And the prisoners were gratefulfor the support. From prison, Fr. Swamy (1937-2021) wrote, ‘First of all, Ideeply appreciate the overwhelming solidarity expressed by many people duringthese past 100 days behind bars. At times, news of such solidarity has given meimmense strength and courage, especially when the only thing certain in prisonis uncertainty.’

In the last line of the missive,he said, ‘A caged bird can still sing.’

Once, when Sahba Husain went tomeet her jailed partner, human rights activist Gautam Navlakha, he quoted aline from Canadian singer Leonard Cohen: ‘There is a crack in everything.That’s how the light gets in.’

One of the most moving chaptersis called ‘Small Things’. The authors had asked the families of prisoners andthe prisoners themselves to share objects that were meaningful to them abouttheir experience in jail. These photos are displayed in the book.

For example, Fr FrazerMascarenhas, who was Fr. Swamy’s guardian and official next-of-kin, preservedthe hearing aid that was used by the late activist. There are paintings andphotographs. But the most touching was when Khalid Saifi’s daughter Maryam drewa card for her father, but the guards would not allow Khalid’s wife Nargis toshow it. So Maryam requested Nargis to draw it on her arm, and they took aphoto.

In another section, there arepoignant letters written by the prisoners to family members, to jailsuperintendents, and friends.

This is a heart-breaking book.Most people are not aware of how bad things become when the state moves againstyou when you show dissent. So the authors have to be commended for anextraordinary achievement. Publisher Westland, through the Context imprint,deserves plaudits for having the courage to publish it.

Finally, the authors make atelling statement in the epilogue: ‘The Indian state, with its immense powerand vast resources, was scared of its writers, thinkers, scholars andactivists. Its prisoners stood tall, laughed and sang in the face ofunrelenting assaults.’

(Published in scroll.in)

August 28, 2024

The world of spiritual deities

Captions: The book cover; author K. Hari Kumar; a Kola dancer

Best-selling author K Hari Kumar has written an eye-opening and engaging book about the folk practises in Tulu Nadu, South India

By Shevlin Sebastian

K Harikumar received an invitation to take part in a podcast in Mumbai in 2022. It was a time when Hari, a Pune-based best-selling author, was at a low ebb. Hari’s instinctive reaction was to avoid taking part in the podcast. But he changed his mind.

During the podcast, the host probed his origins in Tulu Nadu. And he ended up talking about the tradition of spirit worship in that area. Tulu Nadu comprises the regions of Dakshina Kannada, Udupi (Karnataka) and Kasaragod (Kerala). In Indian mythology, this area is said to be part of the Parashurama Kshetra and is steeped in legends and folklore.

After the podcast, Hari went into a restaurant to have an idli and sambhar. To his surprise, a familiar visage greeted him from behind the cashier’s desk. It was a framed photograph of Kateel’s Durgaparameshwari. ‘This was no ordinary picture of any goddess. She was the presiding deity of the very place I had discussed in the podcast,’ wrote Hari.