Shevlin Sebastian's Blog, page 10

February 4, 2024

Leading the charge

Photos: (from left) Sreeram KV, Sanid Asif Ali and Tony Davis; Gustoso the comic

Three young comic enthusiasts are spearheading a comics culture in Kerala

By Shevlin Sebastian

One morning, a few years ago, Sanid Asif Ali was driving to work in the suburb of Kakkanad, near Kochi. As the IT professional went past several high-rise buildings, he came across the Brahmapuram waste dumping site. Suddenly, he wondered, ‘What if a few animals were living there?’

That night, he went home and did a story about a cat named Beardo. He came across an empty packet of Italian-make Gustoso! biscuits at a garbage dump. Beardo showed it to his friends, a dog, Skinny, and a crow. The last owner of the cat had fed one to him before he died. It was one of the tastiest biscuits Beardo had eaten. So the trio went in search of these biscuits at the home of human beings in a nearby building.

The four-chapter comic discussed hunger, cruelty to animals, abandonment and the excessive garbage produced by human beings. It was uploaded on the tinkle.in website, in June 2020.

Sanid used to draw doodles from his childhood. He fell in love with comics when he came across his cousin Baijukka’s collection of Tintin comics. At eight, he started drawing comic strips. He continued throughout his teenage years.

When he grew up, Sanid began putting up single panel cartoons on Facebook. But a desire lurked in him to do a long-form comic. “I achieved it with ‘Gustoso!’” he says, with a smile. “It was a turning point in my life.” Some of his other books include ‘Krishnavanam’, ‘Hope on’ and ‘Cat needs a friend’.

Sanid met the wider comic community when he took part in the Indie Comix Fest (ICF) at Kochi in 2018. It was at this fest that Sanid met Sreeram KV. Sreeram was a writer who was interested in comics.

Through an Instagram post, Sanid also came to know that a filmmaker named Tony Davis ran a comics library at Kochi. So Sanid went to see the library.

There were Indian and international comics like Manga (from Japan), Archies, Mandrake, Asterix, Phantom, and old Malayalam comics. Sanid became a regular borrower. Sreeram also used to borrow comics from the library.

The three became friends. Tony and Sreeram collaborated to bring out an eight-part comic documentary, ‘Katha Vara Kathakal’, about the evolution of comics in Malayalam, from the 1970s to the present. It was released on YouTube in September, 2020.

The film focused on Kannadi Vishwanathan, the creator of ‘CID Moosa’ comics, Jacob Varghese, publisher of ‘Regal comics’, R Gopalakrishnan, former editor of children’s magazine, ‘Poompatta’, Abdul Hameed, creator of ‘Inspector Prakash comics’, and George Mathen, graphic novelist, ‘HalaHala’ series, among many others.

In 2019, the Comic Collective had conducted the ICF. But the organisers were involved not only in comics but movies too.

Tony told Sreeram and Sanid that they should have a dedicated community only for comics. “Comic creators and enthusiasts should join forces together,” says Tony. So, the trio organised the ICF in December, 2022. This became a success.

A year later, on December 17, 2023, the fourth edition took place.

Asked about the themes explored in the comics, Sanid says, “There are social and mythological themes. The artists spoke about their self-doubt and anxieties, the pains of childhood and an uncertain future, because of climate change. An 11-year-old boy brought along a superhero comic.” A Mumbai-based group called Urban Collective explored the concept of space in the financial capital.

Many had brought self-published works. A few comics were brought out by small publishers like Studio Niyet, Bakarmax, Kokaachi, and Blaft.

For the illustrators, one drawback was the high cost of printing. Big publishers have bulk print runs, which reduces the cost per unit. “However, it is difficult to get a mainstream publisher,” says Sreeram.

But a major publisher, HarperCollins, brought out a graphic novel about addiction called ‘Pig Flip’ by Malayali author Joshy Benedict in December, 2023. When it was originally published in Malayalam, it had received a lot of attention.

For most comic book authors, they have to self-publish. “Hence the prices of the books are high,” says Sreeram.

One artist, Kalyani B, whose book, ‘Matinee’, cost Rs 500 to print, was compelled to sell it at Rs 850. Still there were good sales.

It is about five women in a hostel in Thiruvananthapuram in the 1990s. They went to watch an adult Malayalam movie called ‘Rathinirvedam’ (Adolescent Desire). This was based on her mother’s experiences. Kalyani adapted it into a comic book.

On the morning of the fest, the organisers honoured veteran artist M Mohandas by presenting him with a memento. They also made a caricature of him surrounded by well-known characters like Ramu, Shyamu, Kapish, Mayavi, and Luttappi. He had drawn them mostly for Amar Chitra Katha comics. “Mohandas Sir had drawn these characters for over 50 years,” says Sreeram.

As for the composition of the crowd who attended, Tony says, they were mostly young people. But this year, for the first time, there was an older section who came in, including people from the film industry. Ganesh Raj, who directed the hit film ‘Anandam’ (2016) was one of them. Another was playback singer Sachin Warrier.

Asked whether there is a growing comic culture in Kochi, Tony agrees. Many books are being published, including those for children. There is readership for each age group.

Local participation is also improving, he said. Out of 46 illustrators, who took part in the recent fest, more than half were from Kerala. The rest came from Bengaluru, Chennai, Mumbai and Delhi. “To expand the community, we encourage beginners a lot,” he says. “So, there is no screening. If you have made a comic, you can take part.”

As to the finances to conduct the fest, the trio depended on the Rs 700 registration fee they charged. They also got a sponsor, Lilo Rosh, a company which makes bags and sketchbooks for artists. Because it is volunteer-driven, they could keep the expenses low. “We are not making a profit,” says Sreeram. “Everybody is in this together. We want everybody to own the fest.”

(Published in the Sunday Magazine, The New Indian Express, South India)

January 14, 2024

The Hungry Tides

Captions: George Vadakkeparambil, 73, has acted in 40 dramas. He performed till the age of 65. He stopped because of poorhealth

Fromher childhood Alphonsa was interested in Chavittu Natakam. When her familyresisted her desire to be an artist, she tried to commit suicide. Moly Kannamali,a famous Chavittu Natakam artist and film star became Alphonsa’s mentor.Today, Alphonsa has acted in many dramas. The widowed Alphonsa lives inher hut all alone. Her children have grown up, got married and moved away

Antony,a daily wage labourer, plays Raja Antony. Antony was 16 when he performedfor the first time. Today, he is 76. Because he has played the role of aking many times, he is now called Raja Antony

Silosh,35, with his family. He learned Chavittu Natakam from his uncle. He has performedmore than 50 times. During high tide, at nights, Silosh and his family sitawake on the cot till the water recedes

T.J. Xavier and his wife. In 2018, flood waters entered his houseand he lost his costumes and props

Photographer KR Sunil

Documentary photographer KR Sunil’s exhibition focuses on the Chavittu Natakam artists who are battling poverty and climate change

By Shevlin Sebastian In December 2015, documentary photographer KR Sunil went to the island of Gothuruth, off the coast of Kochi, to watch the annual Chavittu Natakam festival.A brief history about the art form: In response to the Kathakali dance form, the Christian community came up with Chavittu Natakam in the 16th century. Unlike in Kathakali, the dancers sing and speak aloud and stamp their feet on the stage. This is accompanied by the beating of drums. It developed in the coastal areas, like Kochi, Alleppey and Kodungallur. The themes are from the lives of Christian saints, Biblical themes, and the history of Christianity. The costumes have a Portuguese influence and include brocade dresses, headgear and crowns. In the Malayalam film, 'Kutty Srank’ (2009), Mammootty played a Chavittu Natakam artist. Sunil ended up watching the shows by different groups for four days. He went backstage and became friendly with Somanath, the make-up artist. An idea grew in Sunil’s mind to do portraits of these artists. During the performance on the fourth day, Somanath asked Sunil not to come on the last day. Because the artists who came from the coastal region of Chellanam were dark-skinned. So Somanath would have to work hard to make them fair. Hence he would not be available to chat with Sunil. Nevertheless Sunil went. He immediately realised they were poor people, as compared to the mainly middle class people who had performed in the previous days. They were Dalit Christians. Many of them worked as fishermen, house painters, and labourers. “But it was clear to me, after talking with them, they had a passion for the art form,” says Sunil. He decided to take portraits of them. But when Sunil went to their houses, he got a shock. Many of them lived in dilapidated hovels. In some houses, blue plastic sheets comprised the wall or covered the large hole in the roofs. The paint was peeling off. He found the contrast unbelievable. On stage, they played kings like Raja Antony, and prime minister Mantri Pappachen, and performed against the backdrop of castles. “But in their daily lives, they lived in abject poverty,” says Sunil. “But that did not stop them from spending money for costumes and travel.” Sunil took the photos over four years. He noticed that in the winter months of November to January, water from high tides inundated their houses. Many times, when he went in the morning, he noticed that everybody was sleeping. The artists would inform Sunil that the water had entered the house in the night. Since many of them slept on the floor, they sat up on the wooden cot. They went to sleep only when the waters receded at 6 a.m. The children missed school. One of them, Thankachan, left his house, and moved on to higher ground. “This is the distinct impact of climate change,” says Sunil. “The waters began to rise after the 2004 tsunami which hit the coast of Kerala.” Sunil made them wear their Chavittu Natakam costumes and asked them to pose in the flood waters. There are about one hundred artists. They are in the age range of the fifties, sixties and seventies. “There are no new artists, because there is no income from this art form,” says Sunil. ““There is no state or corporate support. Because they are Dalits, they have no influence. So, once these generations pass away, the art form will die.” However, there is Silosh, who is 35 years old, who is interested and doing well. Sunil's work had been shown at the recent ‘Contextual Cosmology’ exhibition held at the College of Fine Arts, Thiruvananthapuram. The curators were Bose Krishnamachari, Abushka Rajendra, Premjish Achari and Sujith SN. The exhibition concluded on December 31. In his earlier projects, Sunil has focused on the marginalised. He did a series on dhow workers who were going through hard times. He did one on the Muslim community of Ponnani, and the mixed communities of Mattancherry. Sunil also said that those who live off the sea and by the side of it tend to be more open and honest. “That is the effect of living next to Nature,” he says. (Published in The Sunday Magazine, New Indian Express, South India and Delhi)January 10, 2024

Soul Talk

By Shevlin Sebastian

Some people get away with murder. The police are not able to solve the case. The murderer lives to a ripe old age and passes in his sleep. When the victim, a soul in the next world, probably, a man, realises the murderer’s soul is arriving, what is his reaction? Will he appeal to God for justice? Would he say, “This man must be punished. How about a thousand years in hell for snuffing out my life prematurely and against your will?”What will God reply? What about couples who have gone through a nasty divorce? Will the souls meet in the next life? If yes, will they glide past and ignore each other? Or will they kiss and make up? Or will they have a nasty argument once again? What about the children of these couples? How will they react when they see their parents? Will they all hug and kiss each other and make up and be a happy family once again? What about relatives and siblings who have fought with each other mostly over money and property? And employees who did not get along with their bosses? Would they reveal their suppressed anger at their superiors when they meet them? What about the despot who has ordered a war? Thousands of young soldiers have died. The leader moves with a several-layer security detail. It is impossible for their relatives to approach him. But can the soldiers approach him when he dies and goes off to the other world? Surely, on that side, he no longer has a security detail. Can they remonstrate with him? Maybe even give a slap or punch him in the face. What happened when Adolph Hitler, Joseph Stalin and Mao Zedong went to the other side? Would the millions of people the trio had killed through war, concentration camps, executions, and in prison have accosted them? Could God have set up a Truth and Reconciliation Commission? What about Stalin’s wife, Nadezhda Alliluyeva? Will she beat him up in anger? During a dinner party at the Kremlin in November 1932, she had an argument with him. Nadezhda was distressed to hear Stalin had been having affairs. She left the party early and went home. The next morning, November 9, Nadezhda killed herself using a Mauser pistol. The mother of two was only 31. There are so many people who get away with so many misdemeanours. And nothing seems to happen to the perpetrators. Only the victims and their families suffer for the rest of their lives. You can see world leaders smiling happily at the cameras. Many of them have blood on their hands, and they also have billions in their bank accounts. Till someone shot him dead like a dog, Muammar Gaddafi of Libya lived a life of luxury and untrammelled power. He jailed people at his whim and fancy and destroyed so many families. He was one of the rare leaders who faced retribution while he was alive. Another leader who faced retribution while he was alive was Romanian leader Nicolae Ceausescu (1918-1989) who faced a firing squad and died. China’s Mao Zedong, responsible for between 40 and 80 million deaths, through prison labour, starvation, and mass executions, died in his bed on September 9, 1976 at the age of 82. Can these millions of souls approach the soul of Chairman Mao and ask him to give an explanation? Will he suffer in the next world? Or will he escape retribution once again? Scientists say there is no life after death. They say we merge into the mud and get wiped out. But close to his death, my father recounted he had seen his parents and a brother-in-law who had died in a motorbike accident at Kolkata when he was 24 years old. Shahul, the nurse who looked after my father, said that he had been at the bedside of over 30 end-of-life patients. All of them reported seeing their relatives and ancestors. When death approaches, the souls arrive to provide reassurance regarding the journey to the other world. A thought arises: will we carry our resentments, anger, hatred, and frustration to the next world? Who can provide the answers to these questions? Probably nobody.January 2, 2024

Following a dream

By Shevlin Sebastian

By Shevlin Sebastian The other day I met a young man from Kannur in north Kerala who aspires to be a scriptwriter in Mollywood. He told me a story about doing a movie through the eyes of a five-year-old child. I was not sure whether it was lively. “I am not a film person,” I said. “But I think you need a conflict to make it interesting.”

He told me he wanted to be a scriptwriter from the time he was in Class 8. I am not sure whether he has done a scriptwriting course to learn about the techniques. I fear he may not have the talent. Who can tell whether you have talent? When you are young, your enthusiasm and energy can carry you through. But once youth passes, you can only survive if you have talent.

And do you have a talent that is popular? Can what you create entrance many people? Not everybody is given this gift. Oscar-winning musician AR Rahman has this gift, and so did the late singer Lata Mangeshkar. AR Rahman’s sister Raihanah said, “There are many music directors who are geniuses. But nobody knows them.”

Because they have a talent that is esoteric. Only a few people can appreciate their work. Hence, they cannot earn enough to live off their work. Their talent becomes a hobby. They need to work elsewhere to earn a living. Adds Raihanah: “Mass appeal is a divine gift.”

This young scriptwriter will spend a few years trying to achieve his dream. If he succeeds, it will be a delightful story. A man who followed his dream and achieved it. But if he has no takers for his scripts, provided he has the energy and stamina to write them, he would have lost a few years. Can he have a lucky change of direction? Find a profession for which he has a knack? Who knows?

It’s all up in the air.

We hear stories about people who made it. And we celebrate them. Dharmendra and Dev Anand came from Ludhiana and Gurdaspur respectively, to try their luck in Bollywood. Both succeeded beyond their imagination. But what we also know is that thousands of other hopefuls had come and returned with unfulfilled dreams. For decades, they felt bitter, angry and frustrated.

A friend said that the only unerring guide to make right decisions is your intuition or your gut instinct. It will lead you down the right path.

To get in touch with your intuition, he said, one should go inside. Silencing the mind, listening to your breath, and meditation will help.

An immense power lives within. He said we need to consult it and move forward under its guidance.

Is this the right way?

Maybe it is.

But nobody can say for certain.

The proverb may be right:

Many are called, but few are chosen.

December 28, 2023

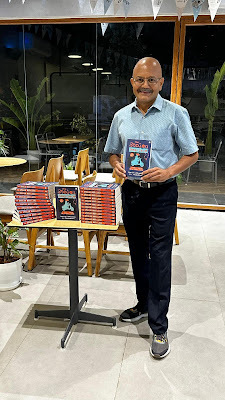

Book reading at Bengaluru

Many thanks to HarperCollins Publishers for arranging this book reading at the Blue Tokai Cafe in Bengaluru earlier this month. Thanks to fellow writer Divya Ramachandran for being the host. Thanks also to friend Ratheesh Sundaram for his help. And thanks, too, to Neethu M Eldose for her kind words:

Many thanks to HarperCollins Publishers for arranging this book reading at the Blue Tokai Cafe in Bengaluru earlier this month. Thanks to fellow writer Divya Ramachandran for being the host. Thanks also to friend Ratheesh Sundaram for his help. And thanks, too, to Neethu M Eldose for her kind words:  Long overdue share!

Long overdue share!  Shevlin Sebastian was just a voice to me until I met him at @bluetokaicoffee at his book reading. The gentleman I heard turned out to be just as warm and positive in person. The warmth in his voice translated perfectly into his persona.***“When V.K. Thajudheen, a middle-aged man working in Doha, returned to his hometown, Kannur, after a few years, little did he know that instead of celebrating his daughter's summer wedding he would be put behind bars for stealing a gold necklace.”

Shevlin Sebastian was just a voice to me until I met him at @bluetokaicoffee at his book reading. The gentleman I heard turned out to be just as warm and positive in person. The warmth in his voice translated perfectly into his persona.***“When V.K. Thajudheen, a middle-aged man working in Doha, returned to his hometown, Kannur, after a few years, little did he know that instead of celebrating his daughter's summer wedding he would be put behind bars for stealing a gold necklace.”

" #TheStolenNecklaceListening to Shevlin share #snippets from his book, I felt the joy of a writer sharing his creation. The Stolen Necklace may revolve around a small-town crime, but its twists and turns unveil the incredible journey of a common man battling the system and achieving a miraculous victory.

" #TheStolenNecklaceListening to Shevlin share #snippets from his book, I felt the joy of a writer sharing his creation. The Stolen Necklace may revolve around a small-town crime, but its twists and turns unveil the incredible journey of a common man battling the system and achieving a miraculous victory. Grab your copy on Amazon: https://shorturl.at/CSTZ8#BookRecommendation #authorengagement #TheStolenNecklace #MustRead

Grab your copy on Amazon: https://shorturl.at/CSTZ8#BookRecommendation #authorengagement #TheStolenNecklace #MustRead

https://www.facebook.com/neethu.meldoseThanks also to Sebastian Valiakala: 'The Stolen Necklace' is written by renowned journalist Shevlin Sebastian and expatriate businessman V.K. Thajudheen. While Shevlin was with New Indian Express (Kochi), Hindustan Times (Mumbai) and The Week (Kochi), Thajudheen was doing business in Doha. This is a non-fiction piece that touches upon Thajudheen's quiet life with a heart-wrenching account of a theft charge and its miseries.Thajudheen, a native of Thalassery, came to attend his daughter's wedding and was arrested by the police in a case of theft of a necklace. But Thajudheen was able to be released from prison after proving his innocence through constant struggle.What happened to Thajudheen today can happen to you tomorrow. This idea is what made this book so popular. The Thajudheen incident is now world famous.The book was highlighted at the Bangalore Literature Festival. Shevlin Sebastian was also the speaker at one of the sessions.https://www.facebook.com/sebastian.valiakala.3

https://www.facebook.com/neethu.meldoseThanks also to Sebastian Valiakala: 'The Stolen Necklace' is written by renowned journalist Shevlin Sebastian and expatriate businessman V.K. Thajudheen. While Shevlin was with New Indian Express (Kochi), Hindustan Times (Mumbai) and The Week (Kochi), Thajudheen was doing business in Doha. This is a non-fiction piece that touches upon Thajudheen's quiet life with a heart-wrenching account of a theft charge and its miseries.Thajudheen, a native of Thalassery, came to attend his daughter's wedding and was arrested by the police in a case of theft of a necklace. But Thajudheen was able to be released from prison after proving his innocence through constant struggle.What happened to Thajudheen today can happen to you tomorrow. This idea is what made this book so popular. The Thajudheen incident is now world famous.The book was highlighted at the Bangalore Literature Festival. Shevlin Sebastian was also the speaker at one of the sessions.https://www.facebook.com/sebastian.valiakala.3

December 15, 2023

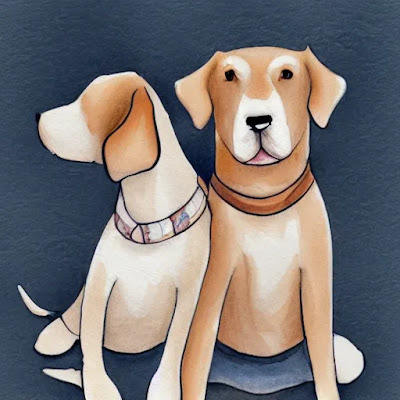

A tale of two dogs

By Shevlin Sebastian

By Shevlin SebastianI heard the agonising wail followed by quick barks at 2 am. This surprised me. Usually, cats are the ones who make these sad moans. This was the first time I heard a dog being in this sort of emotional trauma.

The next morning, as I set out to buy milk, I saw the brown-skinned dog. I am calling him Sam. Sam stays near my house, in Kochi, on the road. He is a stray. Sam was alone. His eyes were drooping and so was his jaw. His inseparable companion, a smaller female brown-skinned dog, Molly, was no longer there.

This came as a shock to me. It meant that she had died in a car accident. I was told that dogs cannot properly gauge the distance when cars approach them. As a result, they are hit frequently. And many die like that.

That night, Sam again let out several moans. This continued for two more nights.

But on the fourth morning, I saw Molly had reunited with Sam.

So what happened? Did Molly run away with another dog? Or did they have a massive fight and Molly ran away to get some respite? Or was Molly tiring of the relationship? And wanted a change.

Did Sam go in search of Molly and then apologise and beg her to return?

I don’t know.

In the initial few days, Molly kept a distance of a foot between them. Then, over a few days, they became close as twins. What they loved most was to sleep next to each other under parked cars during hot summer afternoons.

Recently, I saw Sam jump on to a low wall and walk to the end. Molly followed. Then Sam jumped into a vacant plot of land. It comprised plants, coconut trees, and banana bushes. Molly stared at him. Then she looked to the left. Then backwards. In the past, she would have jumped right away. Now Molly turned back, reached the end of the wall and jumped back to the road. No more following Sam blindly any more.

Can Sam adjust to the new Molly? Who knows? Only time will tell.

This morning, there was another shock.

There was no Molly around. Sam sat by the side of the road, his lower jaw pressed against the tarred surface.

It seems they have not resolved things. Molly’s gone again. A crack has formed in the relationship. And it looks like they tried to paper over the differences. But it seems to have failed.

Wow, this is like human relationships.

Sam is battling to remain connected. But Molly seems to have changed. And doesn’t want to go back to play the docile role of earlier times.

I am waiting to see what happens next.

This is the woman’s century, both in the human and the animal world.

They are calling the shots.

And males will have to adjust to the new reality.

December 6, 2023

Celebrating the memory of BR Ambedkar

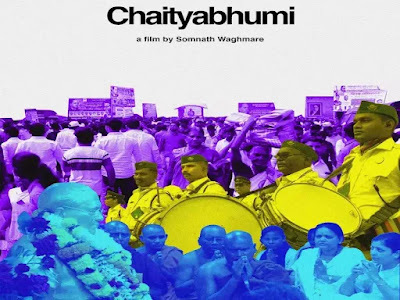

Photos: The poster of the documentary; Somnath Waghmare; the Ambedkar museum in Dadar

Celebrating the memory of BR Ambedkar

Filmmaker Somnath Waghmare has made a moving documentary on Chaityabhumi, the cremation site of BR Ambedkar, the legendary leader of the Dalits. His death anniversary is on December 6

By Shevlin Sebastian

The documentary film ‘Chaityabhumi’ by filmmaker Somnath Waghmare opens with a painting of BR Ambedkar’s wife Ramabai hanging on a wall. It pans to a wooden desk. On top of a folder, you can see the spectacles worn by Ambedkar. Behind and on the sides are bookshelves which contain books.

The camera focuses on the different photographs that highlight the career of the noted social reformer, lawyer, and political leader of the Dalits. Suddenly, Ambedkar’s high-pitched, and intense voice can be heard on the soundtrack.

“Our difficulty is how to convince the heterogenous mass that we have to take a decision today in common and march in a co-operative way on that road which is bound to lead us to unity.”

This is the heritage museum on the ground floor of Ambedkar’s bungalow in Dadar. It is called Rajgruha. Ambedkar’s descendants stay on the upper floors. Visitors come from all over India and the world. Entry is free.

The film soon tracks the lakhs of people as they came, on December 6, to celebrate the death anniversary of their beloved leader. The cremation location, the Chaityabhumi, a Buddhist chaitya or temple, is next to the Dadar Chowpatty beach.

Many people wear the colour blue, which signifies the Dalit movement. One theory is that the blue represents the sky. Under the sky, everybody is equal. Ambedkar’s trademark suit was in blue.

In the documentary, Rahul Telgote, a blind musician, sitting cross-legged on the ground, hits a drum with both hands and sings:

“Oh Bhima, be born again for the oppressed, troubled and tired

Their hearts are longing for your arrival.

Oh Bhima, behold your 90 million people

The ones who are ready to die at a word from you

You are their guiding light.”

A little distance away, a young man shouts,

Emancipator of women

A group of young men in white shirts and pointed caps shout in unison: Babasaheb (this is the nickname for Ambedkar, which means respected father).

River Linking Projects

Babasaheb.

Journalist

Babasaheb.

And the young man enumerates the achievements of Ambedkar: Equality/Fraternity/Economist/The only ruler/Your ruler, our ruler/Constitution maker/The lawgiver/Bodhisattva/Crown of the world.

The action continued.

The Samata Sainik Dal (The Equality Squad), in khaki trousers, does a march past, with beating drums and flutes. One can see bald-headed Buddhist monks in yellow robes. One held a placard stating they were from the Bhikkhu Sangh of North-East Mumbai. “They are mostly Dalits who converted to Buddhism,” says Somnath. “But for the Chaityabhumi, monks had also come from Myanmar and other South-East Asian countries.”

Amidst the chanting of Buddhist prayers, people placed garlands on the statue of Ambedkar.

In 1956, to get away from the oppression of the caste system, Ambedkar adopted Buddhism, along with five lakh compatriots.

“This was more a political act, and less to do with spirituality,” says Somnath. Today, the Dalits continue to follow Buddhism.

Charan Jadhav, a singer and actor, with a blue bandana tied across his forehead, sings a song in praise of two kings: Chhatrapati Shivaji (1630-80) and Ambedkar. On the skin of Charan’s drum, the words Jai Bhim, the Dalit greeting, has been painted in blue.

“King Shivaji’s courts brought justice to the people,” sang Charan.

Adds Somnath, “The Dalits hold Shivaji in high esteem. He was a progressive ruler. He treated all classes and castes of people equally. There was no discrimination. This has been elaborated in [rationalist] Govind Pansare’s best-selling book, ‘Who was Shivaji?’.”

There are Dalit intellectual voices in the documentary. One of them is Dr. Rahul Sonpimple, scholar, President, All India Independent Schedule Caste Association.

“Ambedkar is part of my emotional and spiritual life,” he says. “When I visited Chaityabhumi, I cried. But the Indian state is the replica of the society that practises untouchability. Ambedkar was never part of public memory. Most of the monuments or the memories we have about Ambedkar are community-created.”

Commonwealth Scholar Pranjal Kureel added, “Academia and media have erased or appropriated the ideas of Babasaheb, but when you go to Chaityabhumi, you realise his ideas are still being taken forward. The fire is still burning, and the wheel is moving. The emancipation from the framework of caste is necessary for everybody, not just Dalit people. There is an assertion through art, culture and music. That is very overwhelming. Freedom of mind is the biggest thing.”

The scene then moves to the sprawling Shivaji Park grounds where hundreds of vendors have set up stalls selling many books on Ambedkar and his movement. You can find these in English, Hindi, Marathi, Tamil, Malayalam, and other languages. The other items on sale include photo frames, magazines, booklets, calendars, and paintings. There is Dalit literature and anti-caste treatises.

“Apparently, sales of Rs 10 crore were achieved on that day,” says Somnath. That comes as no surprise because lakhs of people were present.

At night, the family of Babasaheb paid their tributes inside the stupa. They placed garlands on the shining bronze statue. The members included Babasaheb’s great grandchildren, Sujat and Ritika, and grandson Bhimrao Ambedkar and his wife. Visitors sang hymns in praise of Lord Buddha.

At a public meeting, Prakash Ambedkar, grandson of Babasaheb, and president of the Vanchit Bahujan Aaghadi, said, “I do not want to lose again the battle that we have long since won.”

Somnath decided to make a film on the Chaityabhumi because he felt that there were few stories about Dalits in the mainstream.

“Whenever people from non-Dalit backgrounds make a film on us, it is incomplete,” he says. “The Dalit cultural assertion was missing. Most stories in industries like Bollywood are only about the dominant castes. I wanted to tell the story from the Dalit viewpoint.”

Somnath shot for four years before he made the film.

Asked about the state of the Dalits in India, Somnath says, “We know who owns the resources in India. We know who owns all the land, and the cultural capital. We know who has power. We know who controls the media. In the Indian Institute of Technology, the directors are upper-caste. In the official records, the upper-castes continue to dominate in all aspects of life. This is not what I am saying. It is all there in the data.”

Since Ambedkar had done his doctoral thesis at the London School of Economics (LSE) in 1916, Somnath had a screening at the LSE on October 24. “The audience liked the film,” says Somnath.

As quoted in ‘The Guardian,’ Shakuntala Banaji, a professor of social change at LSE, said she was deeply moved after viewing the film. “After generations of misrepresentation in, or exclusion from, mainstream Indian cinemas and media, Dalit directors and producers have started to tell the stories of their communities in original and exciting ways,” she says.

Somnath said he wanted to show the real Indian society. “For most outsiders when they watch Bollywood films, they think it is the accurate picture of Indian society,” he says. “Many people are not aware of the caste system. But with films like [Marathi director] Nagraj Manjule’s ‘Fandry’ (2013) and mine, they are slowly becoming aware.”

Somnath said that after ‘Fandry’ was screened at Columbia University on April 18, 2014, the next Dalit film that was screened was ‘Chaityabhumi’ on December 3, 2023. Ambedkar had also studied at Columbia University.

Asked whether the caste system would ever be eradicated, Somnath says that it depends on the privileged castes. “Only they can dismantle it,” he says. “Maybe some powerful revolutionary might arise and do it.”

But the good news, he says, is that a lot of Dalits are in higher education. Somnath is doing his doctoral thesis in the social sciences at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences. “Until my graduation, I studied in a Marathi medium school,” he says.

As to whether he faced discrimination in his college life, he says, “Discrimination is part of a Dalit’s life. But nowadays, it is subtle. They insult me indirectly.”

Somnath got interested in a film career when he began learning media studies while doing his masters at Pune University. As for the directors who inspired him, Somnath mentions the name of the Iranian filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami (1940-2016), Nagraj and Tamil director Pa. Ranjith.

Some of Somnath’s earlier films include ‘I am Not a Witch’ (2015) and ‘The Battle of Bhima Koregaon: An Unending Journey’ (2017). He is now working on ‘Gail and Bharat’. This is a documentary biopic of the activist couple Dr. Gail Omvedt and Dr. Bharat Patankar, who have worked for long on behalf of the Dalits..

“I want to make films from the Dalit viewpoint,” he says. “This is my life's mission.”

(Published in The Federal)

https://thefederal.com/.../somnath-waghmare-interview-how...

November 22, 2023

A scintillating parade

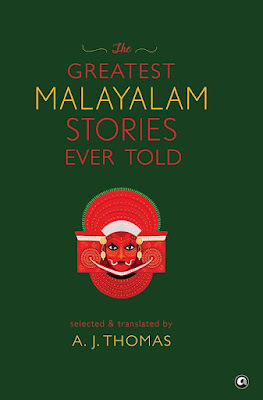

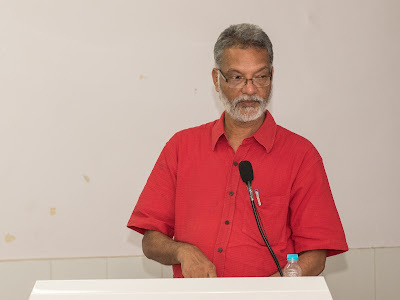

Photos: Translator AJ Thomas; Vaikom Muhammad Basheer, Lalithambika Antharjanam and M. Mukundan

Translator and Editor Dr. AJ Thomas talks about the anthology he has curated titled 'The Greatest Malayalam Stories Ever Told'

By Shevlin Sebastian

One afternoon in November, 2018, Aienla Ozukum, the Publishing Director at Aleph Book Company, walked into the Delhi office of AJ Thomas, the editor of ‘Indian Literature’, a bi-monthly literary journal which is brought out by the Sahitya Akademi.

She told Thomas Aleph was planning to bring out a ‘Greatest Stories Ever Told’ series from all the regional languages. “Since Malayalam is one of the major literatures in India, Aienla wanted me to select and translate the stories into English,” says Thomas.

Immediately, Thomas realised it was a daunting task. But for Thomas, the Malayalam short story was his forte. His M. Phil and PhD dissertations were on the subject. And he has done several translations of notable books throughout his career.

Thomas won the Katha award for his translation of a story of author Paul Zacharia called Salam America. He translated Ujjaini, based on the life of Kalidasa by ONV Kurup, the legendary Malayalam poet. Thomas also translated noted Malayalam writer M. Mukundan’s novel, Keshavan’s Lamentations. This won the Vodafone Crossword Book Award in 2007.

The bespectacled Aienla asked him whether he could deliver the manuscript by January, 2020. Thomas agreed.

The span of selection was 50 years, from the 1950s to 2000s. The first Malayalam short story, ‘Vasana Vikriti’ (Strange Stirrings), was written by essayist Kesari Vengayil Kunhiraman Nayanar in 1891. It appeared in the literary magazine ‘Vidya Vinodini’. “But the serious, well-formed short stories began to appear in the 1930s,” says Thomas.

He based most of his selection on two books. The first one was ‘100 Varsham 100 Kadha’ (Hundred Years, Hundred Stories), which came out in 1991, to celebrate the centenary of the Malayalam short story. Professor KS Ravi Kumar, the former Pro Vice Chancellor of the Sree Sankaracharya University of Sanskrit, curated the stories. The second was author NS Madhavan’s ‘60 Kathakal’ (Sixty Stories). This came out in 2017, commemorating the 60th year of the birth of the state of Kerala. Thomas also relied on several notable previous anthologies, and literary periodicals of the past several decades as well.

The Aleph anthology comprises 50 stories. All the great authors are represented. They include P Keshavadev, Ponkunnam Varkey, Vaikom Muhammad Basheer, SK Pottekkatt, Thakazhi Sivasankara Pillai, Uroob, MT Vasudevan Nair, OV Vijayan, T. Padmanabhan, M. Mukundan, Kakkanadan, Paul Zacharia and several others. Expectedly, the quality remains superb throughout.

Some of the female writers include Lalithambika Antharjanam, K. Saraswathi Amma, Rajalakshmi, Madhavikutty, Sara Joseph, and Manasi.

Lalithambika’s stunning story, ‘Dhirendu Majumdar’s Mother’ is about Shanti Majumdar, the mother of a revolutionary, who herself becomes a heroine during the partition of Bengal and India in 1947, and the Bangladesh Liberation war of 1971.

OV Vijayan’s story, ‘The Hanging’, talks about a father visiting his son in a prison a day before he was hanged.

Here is an excerpt:

‘An intense keening issued from Kandunni, a wail so high-pitched and shrill, it was on the edge of auditory perception.

“Appa, don’t let them hang me.”

“Time’s up, Sir. Please come out.”

Vellaayiappan walked out of the cell and the door clanged shut. When he looked back, he saw his son looking at him from behind the bars as a stranger might from behind the barred window of a train hurtling past.’

P Padmarajan is known for his novels and films. But he has written a short story called Choonda (The Hook). It is about an old man sitting by the side of a pond trying to hook a varal (murrel). He has a 38-year-old daughter who is not married. She goes on cursing him for going to the pond daily and returning empty-handed. One day, the old man finally catches a murrel. The story ends with these lines: ‘A thought gave him great relief. That day, for the first time in the last five days, he could sleep without listening to cursing.’

“It’s a fantastic story,” says Thomas. “There is a superb creation of atmosphere.”

Asked whether there is a difference between the older and current writers, Thomas says, “There is no difference. There are only different ways of story-telling. I selected stories that read well.”

Thomas had interesting experiences while dealing with the writers or their heirs to get their permission.

Thomas called up the multiple award-winning writer T. Padmanabhan, who is 92.

“What will I gain?” said Padmanabhan in a playful tone. “Will I be around when the book comes out? What is the use? What am I worth?”

Thomas said, “You are the greatest living Malayalam short story writer.”

Padmanabhan said, “Who says that?”

“Sir, I am saying it,” replied Thomas.

Padmanabhan laughed.

“His clarity of mind was amazing,” said Thomas.

Most were happy that they were selected for an English edition.

But many writers remained in obscurity during their lifetimes. They include writers like TR (T Ramachandran), Victor Leenus and Thomas Joseph. “They set a different tone,” says Thomas. “You read their stories and you become aware of other realms. Thomas Joseph is a surreal painter with words.”

Joseph had high blood pressure. On September 15, 2018, Joseph suffered a stroke while asleep at his home in Keezhmad, Aluva. The family took him to the Rajagiri Hospital. Since they could not afford to pay the medical expenses, his literary friends, including the writers Paul Zacharia, AK Hassan Koya, and others, including Thomas, pooled their resources. After being released, Joseph spent three years in a coma before he passed away, on July 29, 2021, at the age of 67.

The tragedy, says Thomas, is that when society loses a great writer, nobody is bothered. “Everybody goes after celebrated authors like MT Vasudevan Nair and ONV Kurup,” he says. “I have nothing against these great writers, only admiration. In music, people will celebrate singers like Yesudas. But there are also superb writers like TR and Victor Leenus, whom the public is not aware of. These are the people who, like the great Irish writer James Joyce, worked on the margins. That is why I took pains to include these immortals in this collection.”

The public is no longer bothered about the aesthetic quality of a literary work. “Earlier generations valued art and literature,” says Thomas. “Literature no longer touches people. They seem to be in another world. They are going ahead at a fast pace. The common man does not have the time to stop and look around. They regard literature and the arts as a luxury. To appreciate art, you need time and a meditative mood. Those things are no longer there. Having said that, there is also a minority which is deeply interested in these subjects.”

As to why so many Malayalam writers are being translated into English, Thomas says, “The quality of the writing is very good. This is widely known now. The opening for Malayalam literature into the wider world through English translation happened when Arundhati Roy won the Booker Prize for ‘The God of Small Things’ in 1997, even though it was an English book set in Kerala.”

Thomas also mentioned that the quality of translators has increased significantly. “Translators like Jayasree Kalathil, EV Fathima, Ministhy S and many others are of international standard,” says Thomas. “This has helped create a market for Malayalam books in translation.”

As for the modernist style in Malayalam fiction, Thomas says, “The earliest model of Modernism existed till the early 1970s. Thereafter, there was the Post-Modern period and After Post-Modernism. These are subjective descriptions.”

From the 1990s, the scope of the story changed, says Thomas. “After the liberalisation of the Indian economy, the advent of the information superhighway, the rise of the Internet and social media, these are the new experiences,” he says. “All this is expressed in the writing these days.”

Asked what elements have to be there in a story to make it timeless, Thomas says, “It should be life-affirming. It cannot be a story glorifying Hitler, for instance, or genocide. There should be aesthetic appeal. It should appeal to the intellect. There should be an original voice and fresh experiences. The narrative style is important. It should be tight and competent.”

Thomas is working on a companion volume of stories by writers mainly from the 1990s till the present. He mentions the names of K P Ramanunni, S. Hareesh, Benyamin, KR Meera, B. Murali, Unni R, VJ James, Vinoy Thomas, Subhash Chandran, Santhosh Aechikkanam, VR Sudheesh, E Santhosh Kumar, and a few others.

“They belong to the New Wave of Malayalam short story writers,” says Thomas.

(An edited version was published in The Federal)

November 16, 2023

November 7, 2023

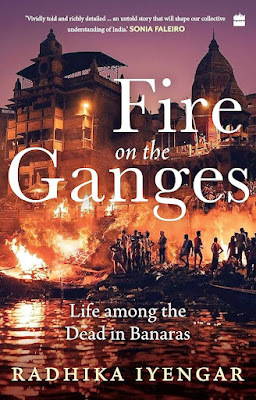

At Death’s Final Stop

Manikarnika Ghat. Photo by Dennis Jarvis

Manikarnika Ghat. Photo by Dennis JarvisRadhika Iyengar’s debut non-fiction work, ‘Fire on the Ganges: Life Among the Dead in Banaras’, takes an in-depth look at the much-maligned community of the Doms. They have been cremating the dead for centuries

By Shevlin Sebastian

As Radhika Iyengar walked through the narrow lane leading to the Manikarnika Ghat in Banaras, she heard a rhythmic chant. It rose and fell. The people were chanting ‘Ram Naam Satya Hai’ (God’s name is the truth).

She stood at one side of the ghat. It is one of the oldest burning ghats on the banks of the Ganges. An inscription about the ghat dating from the 5th century AD Gupta Empire has been found.

Radhika saw several pyres burning at the same time. A few brown-skinned men were lighting other pyres. They were, of course, the Doms. Smoke rose in the air. On the ground, she saw a lot of ash. At one side, a barber was shaving the face of a mourner. On another side, there was a tea stall.

Some men, with bent backs, brought logs into the area. Every few minutes, pall bearers brought bodies on bamboo biers. Stray dogs wandered about. Several men sat on their haunches and watched the proceedings. Out on the surface of the Ganges, Radhika could see marigold garlands floating.

“It was a spell-binding experience,” she said. In 2015, she had come to Banaras to do a report on the Dom community for her thesis project. At the time, Radhika was doing her Masters in Journalism at Columbia University.

Little did she know then that she would come many times, as the idea crystallised to do a book on the community of Doms. They belong to the Dalit community. Society considers them as an untouchable caste. For centuries, their primary job has been the cremation of bodies. There is a belief Doms should cremate upper-caste Hindus if they are to attain moksha (relief from the cycle of rebirth).

“A Dom’s work is highly skilled,” said Radhika. “It is also dangerous and underpaid. Since it is a profession that is anchored in the caste system, the work is passed down from father to son. For many Dom families, there are no alternative work opportunities.”

What pained Radhika was the humiliating way the upper castes treated them.

A few children from the community sometimes accompanied Radhika to the ghat. They would avoid a route that had a small temple. Instead, they would request Radhika to take another way. Later, she realised the children avoided that alley, because the priest would shoo them away. They could not be near the temple premises. “It was unsettling to learn that,” she said.

Radhika also perceived the huge psychological effect this had on the children. “They had no means to cope and no language to express their angst,” she said.

The children also saw dead bodies from an early age. One boy told Radhika that he was only five years old when he saw a corpse. After that, for weeks, the dead man’s face would haunt him in his dreams.

Even the adult Doms went through trying times. The labour was very hard. On summer days, with the heat from the pyre and the climatic heat, it took a toll on their health. Radhika said they could not afford proper medical care. Their burns and wounds went untreated. To see a doctor, they sometimes borrowed money to pay the bills. This led them into debt.

And to cope, they consumed large amounts of alcohol, gutka and ganja. “They do it to forget the stark reality of the work they do, and the lives they lead,” said Radhika.

It took courage and determination by Radhika to befriend the members of the community. She found it easier to talk to the women. “My frequent visits to Chand Ghat made me a familiar face,” she said. “The more time I spent with them, the more they realised I was serious about my work.”

The men were not forthcoming initially. “I was a stranger from a different city. They were also not used to having a woman asking questions about their work or their lives.”

But Radhika persisted. She began writing the book in 2019 and completed it in 2023.

And interacting with the Doms affected Radhika. “Some stories they shared with me were raw and emotional,” she said. “It’s impossible not to be affected. But I tried to ensure that my opinions did not seep into the process of storytelling.”

The book, ‘Fire on the Ganges: Life Among the Dead in Banaras’ (HarperCollins Publishers) is an absorbing read. Radhika delves into the struggles, the sufferings, and the agonies of the Dom community.

The intense politics between family members, the jealousies, the anger, and the hate. Radhika described the financial hardships they faced and their problems with addiction. She also spoke about the difficulties of the new generation in moving away from this strenuous life and to try something new.

There is a youngster called Bhola. He had a great desire to study but was forced to stop in 2001 when he was seven years old because of poverty. In 2006 film-maker Vikram Mathur made a documentary on the Manikarnika Ghat and focused on the boys who ran around collecting the shrouds from the dead bodies. In 2009, an American named George Grey saw the premiere in New York. He felt he had to do something.

George and Vikram came to Banaras and offered to fund the education of the boys. The parents demurred saying they preferred their children work to earn some money. In the end, George agreed to pay Rs 1500 a month to the parents to make up for the loss of income the boys would have earned. And the boys, including Bhola, were enrolled in a school in Cholapur. It was a few hours away from Banaras. Later, Bhola graduated from a college in Ludhiana, and managed to get a job in Chennai. To his relief, nobody knows he belongs to the Dom community.

There is a story of Komal, a Brahmin girl, who fell in love with Lakshaya, a youngster of the Dom community. Lakshaya was studying in a school. Soon, neighbours came to know. Expectedly, there was fierce opposition from both families. But they ran through the gauntlet of fire for a few years before they got married.

The death of one male member, Sekond Lal, the husband of Dolly, had a searing impact on the community for several years. There was suspicion that two neighbours, Gopi and Bunty, had murdered him. But the family members said the police told them it was an accident.

Here is an excerpt:

‘In 2019, even though some years have passed since his death, a strange disquiet continues to linger in Dolly’s body. It makes its presence known whenever she speaks of Sekond Lal’s death or of those who she believes are his murderers. The disquiet manifests in the form of dry grunts, a widening of her eyes, and incessant name calling. Tired and alone, Dolly is consumed by feelings of anger, sadness, betrayal, and vengeance. She slings accusations at Gopi and Bunty routinely, and at times, she issues roaring threats. “I say this: those who have murdered my husband — the way they have stolen my youth, the same way their youth will be ruined.”

After you finish reading the book, you will look at the Dom community with new eyes. You would have seen them from the inside.

A possible future Hindi translation, available at Banaras, might remove the scales of prejudice from the eyes of the higher castes. At Manikarnika Ghat, they might even treat this much-maligned community with sympathy, respect and kindness.

(Published in The Federal)