Shevlin Sebastian's Blog, page 13

July 16, 2023

Good reel

July 3, 2023

Shashi Tharoor: brilliant, charming and down-to-earth

By Shevlin Sebastian

By Shevlin Sebastian At 1.20 p.m. on a day in June, Thiruvananthapuram MP Shashi Tharoor strode into the lobby of his apartment building. Since he was ahead of his aides, I approached him.

âHello, Mr. Tharoor,â I said.

âHi,â he replied. âYour name?â

âI am Shevlin,â I said.

âAs in Shevlin Sebastian,â he said. âI remember the byline.â

You can imagine what this did to me. The last time I met Shashi Tharoor was over ten years ago. And it is very unusual for non-journalists to use the word byline.

When journalists meet for the first time, and we exchange names, sometimes we say, âOh yes, I have seen your byline.â

We keep track of who writes what, when and where.

But when Tharoor said this, I realised he had been interacting with journalists for decades now. Plus, he is an avid reader of newspapers. So Tharoor may have filed some names away in his phenomenal memory.

Of course, the prosaic explanation is that, most probably, his aide would have told him a journalist would be meeting him at 1 p.m. and mentioned the name.

I showed him the cover of my non-fiction book, âThe Stolen Necklace.â

âIt has been published by HarperCollins," I said.

"What's the story?" he said, as we walked towards the entrance of his ground-floor apartment.

As he heard the early bits of the narration, he immediately said, âI have heard about this case. Didnât it happen in North Kerala?â

âYes,â I replied.

âWhat happened to the cop?â he said.

âNothing,â I replied.

âNo disciplinary action?â he said.

âNo,â I said.

âVery sad,â he said, shaking his head.

Inside his apartment, the striking feature was that the books written by Tharoor were pasted high up on a wall, just near a wooden ceiling.

As we conversed, a man appeared. He turned out to be a director on a TV channel. He gave a wedding card to Tharoor. It was his daughterâs marriage. Tharoorâs aide seemed to have informed him earlier about the matter.

Tharoor immediately said, âI am sorry I cannot come to the wedding because I have a function in Kochi.â

But he promised he would come another day.

I asked him whether he would read the book.

âTo be honest, I am exhausted by this work [as an MP]. I rarely get time," he said. âBut I do get time on planes. So I will read it. I have always liked your writing style.â

A journalist friend who knows Tharoor said that he is a master at speed reading. Apparently, he only has to scan a page with his eyes. I donât know how true this is. But in less than 24 hours, he put out a tweet. It was succinct and explained the book well.

Here is the tweet:

âPleased to receive a copy of âThe Stolen Necklaceâ from journalist @Shevlin_S, the true-life story of a gross miscarriage of justice in Kerala, when an innocent man was jailed and ruined on suspicion of being a necklace thief.

âThis was the result of a shoddy investigation that relied on his passing resemblance to the real culprit on CCTV footage.

âShevlin Sebastian writes well, and the story is full of lessons for our policing and justice systems.â

Tharoor has been brilliant for a long time.

Here is an entry from Wikipedia: Tharoor was awarded the Robert B. Stewart Prize for the best student at the Fletcher School at Tufts University. He was also the first editor of the Fletcher Forum of International Affairs. At 22, he was the youngest person to receive a doctorate in the history of the Fletcher School.

Tharoor had a 29-year career at the United Nations where he became Under Secretary-General. He quit the organisation in 2007. And at age 51, he had the courage, tenacity, and determination to embark on a new career in politics. Tharoor has made a success of it by becoming a three-term MP. How many people can have two successful back-to-back careers? Only a handful, I think.

In person, Tharoor radiates charm and a down-to-earth manner.

We can only hope that one day, he will become the Chief Minister of Kerala, and through a throw of the dice, why not, even the Prime Minister of India.

Many thanks to 'The Week' for their coverage

It is based on the real-life story of Thajudheen, a man wrongly accused of robbery

By Anansiya Sabu Updated

By Anansiya Sabu Updated

What do you do when the people who you are meant to trust your life with, are scarier than the ones who are after your life? It is incredible how stubborn people can be, even when they are wrong. It is even more incredible how the vanguards of our legal system will not change their ways even after being called out. When they become a legal nightmare, one must resign to the fact that our democracy has lost its plot.

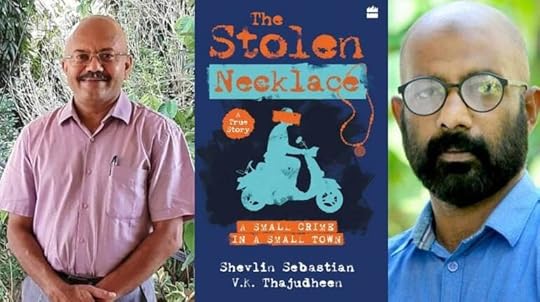

The Stolen Necklace chronicles the real-life story of V.K. Thajudheen â a man wrongly accused of robbery, and who had to endure 54 days in prison and, till today, has not been compensated for the mental, emotional, and physical trauma he was subjected to. The book has been jointly authored by Thajudheen and Shevlin Sebastian â a seasoned journalist who had been following the case from day one.

Law enforcement in India is notorious for being quick to mete out punishment. Pressure from higher authorities often makes it impossible for policemen to act impartially. But it is the ordinary bystander who suffers because of this. He becomes the pawn who must be sacrificed in order to close the case.

In this novel, the cops from Chakkarakkal, a small town in Kerala, accuse a man of chain-snatching, based on the evidence of a single CCTV screen grab. They seem to be hell-bent on not letting him go without a bribe. In a single moment, the life of the middle-aged father of three, with a newly-wedded daughter, is turned upside down. He becomes a criminal caught in the cross-hairs of bruised egos and unjust tactics.

In simple language, one is taken through the trials and tribulations of the protagonist. At the Thalassery prison, uncertainty and loneliness become constant companions. In a place where everyone is treated as sub-human, it is a struggle to maintain his humanity. As the days bleed into each other, memories become a less painful companion. âEvery night ends in dawnâ becomes a constant refrain, as Thajudheen vows never to give up, even as hope slowly starts dwindling.

The book provides rich insights and highlights other cases of the police wrongfully accusing innocent people, while the actual perpetrators go scot-free. The story does not end with Thajudheen being proved innocent before the law. The irreversible damage caused by the reckless investigation and brutal misuse of the law does not simply disappear in a few days. A man once convicted will live the rest of his life in fear, constantly looking over his shoulder. Everyone deserves justice, but when the system that is tasked with providing it is faulty, it ends up being an unattainable dream for many.

The Stolen Necklace

By Shevlin Sebastian and V.K. Thajudheen

Published by HarperCollins

Price Rs 399; pages 249

https://www.theweek.in/review/books/2...

June 29, 2023

Nice reel on 'The Stolen Necklace'

June 27, 2023

Many thanks to Moneycontrol for their coverage

(From left) Shevlin Sebastian; his book 'The Stolen Necklace'; VK Thajudheen, on whose life the book is written

(From left) Shevlin Sebastian; his book 'The Stolen Necklace'; VK Thajudheen, on whose life the book is writtenSomeone known to me was imprisoned for a crime he did not commit. His family faced unbearable agony, given that he was not only the sole earning member of the family but also because he was innocent. However, the latter is a statement that can be questioned because it has elements of unrecognised bias in it.

When this person finally got bail, he told me that most people languishing in the jail premises have been falsely implicated under a criminal offence because someone had to be put behind bars. Some of these inmates have gotten used to the premises because theyâve given up hope, he told me. They know that no one can fight for them, and he felt fortunate that he had people and resources who stood up for him and got him out.

READ MORESomething very similar happened with VK Thajudheen, a middle-aged man, who came back to his hometown from Doha for his daughterâs marriage. But little did he know that heâd be jailed for months for a crime he didnât commit: stealing a necklace. The CCTV coverage presented his lookalike, and police were convinced it was no one else but Thajudheen who stole the necklace. While the police tried to extort money for him âto settle mattersâ, Thajudheen wanted his name to be cleared because he believed that truth shall prevail.

In The Stolen Necklace: A Small Crime in a Small Town (HarperCollins, 2023) veteran journalist Shevlin Sebastian tells his story. A poignant tale, which reads almost like fiction, narrates events as they unfold, shares relevant backstories and notes down a similar situation in the United States and what can be done to do away with cases of false implications.

In an exclusive interview with Moneycontrol, he shares what compelled him to tell this story. Edited excerpts:

RELATED STORIES

Good work of people of Kerala marred by petty politics of LDF-UDF: J P Nadda

Good work of people of Kerala marred by petty politics of LDF-UDF: J P Nadda Amitabh Kant: Bringing down the cost of our logistics to globally competitive levels will be a big m...

Amitabh Kant: Bringing down the cost of our logistics to globally competitive levels will be a big m... Two Kerala artists are taking the ancient art of mural painting from walls to canvas

Two Kerala artists are taking the ancient art of mural painting from walls to canvasFrom the vast number of cases of false implications and mistaken identities, what drew you towards Thajudheenâs story?

I selected the Thajudheen story because it was from Kerala and closer to home. We could get a wavelength easily. What intrigued me the most with this case was the conclusion one could draw â if it could be Thajudheen, it could also be you.

The book almost reads like fiction. Were you able to see or distinguish yourself from a journalist reporting findings and a writer telling a story throughout your journey of working on this book?

I used both my skills: as a reporter and a short story writer. One reader said that this marriage has created a unique style.

Itâs remarkable how poised and optimistic Thajudheen remained throughout, but he was one of the lucky ones who happened to be well-connected and received support. Many people, especially the poor and the marginalised, may not have access to the people and resources he had. In such cases, how can their stories of wrongful imprisonment be brought about? And what can be a way to prevent authorities from staging the very people theyâre put in place to protect as criminals?

It is true that Thajudheen was very lucky because of the powerful support he received. It is also true that the poor have suffered enormously over the decades at the hands of the police. The only way is if civil society can fight for justice on their behalf.

On multiple occasions, Thajudheen calls for a better prison environment for the jailmatesâ mental well-being. However, one of the incidents from his youth also shows how little importance our society places on mental health. What do you think can be done to enable people to take mental health seriously, especially by institutions like the police and investigative agencies, as, ultimately, theyâre dealing with people?

Regarding awareness of mental health, the media should do more stories about this. Mental health professionals should hold classes for law enforcement to create awareness. There has to be constant refresher courses which need to be conducted for the police, so that they develop a sensitivity towards the sufferings of people. Their problem is that they work long hours, under great stress and they are always short-staffed.

You share the statistics of Thajudheenâs story going viral on social media. In that regard, what does it mean to report on something sensitive in the age of sensationalising stories via social media?

In the age of sensationalism, I tried to write the truth. I avoided using provocative language. I tried to use simple sentences, so that readers can follow the train of thought. I believe simplicity has its own charm.

Sometimes social media is a good tool to fabricate a false story, and at other times, it comes across as the only solution to gain solidarity when everything fails, and in both cases, a vast majority has already given their verdict, then how do you view this as a tool for justice delivery?

Social media is a double-edged sword. Itâs good and itâs bad. But we have to take the risk. Because it is only through social media (that) we can get the message across.

Are there any organisations in India like the Innocence Project in the United States, and, if not, what do you think can be done here to prevent wrongful arrests?

There is no Innocence Project in India. Only awareness of the need for one by journalists and civil society can make a difference.

Have Thajudheenâs family members read this book?

The family has not yet read the book.

Check your money calendar for 2023-24 here and keep your date with your investments, taxes, bills, and all things money.SAURABH SHARMA is a freelance journalist who writes on books and gender.

June 26, 2023

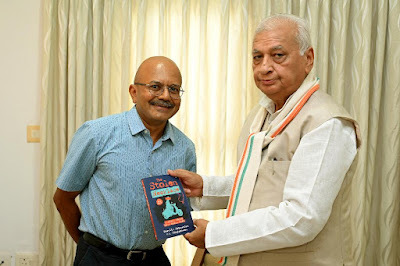

A meeting with the Governor

A little past 1 p.m. on June 19, a few police officers stood at attention as a white car drove into the portico of the Government Guest House in Aluva. In the backseat sat the Kerala State Governor Mohammed Arif Khan wearing a beige waistcoat.

As he stepped out, reporters pushed TV microphones towards him. Asked about his views about the higher education segment, the Governor said, “It’s in a mess. People with dubious credentials are being appointed because they bear allegiance to a particular party. As a Chancellor I cannot allow that.”

He said that the sector was heading towards a collapse.

“Kerala is chasing away talent,” said Arif Mohammed Khan. “And you in the media are terrified of taking on the government. You are spineless.”

A reporter bridled at this statement and said a lot of discussions have taken place on air.

“A discussion is different from an editorial stance,” said the governor.

A man standing beside me whispered, “He is telling the truth about education. But since the governor’s term is ending next year, the government will wait patiently.”

The press conference concluded. The governor went up to his room on the first floor. As I stood outside with a copy of my non-fiction book, ‘The Stolen Necklace’, I asked a member of the security personnel about the time when Arif Mohammed had lunch. “He has no fixed time,” said a plainclothes officer.

Soon, I was called in. A standing Arif Mohammed stretched his hand towards a chair and said, “Please sit down.” We sat down and I presented the book. Since the photographer was hovering around, I told the governor we could take the shots first, so that the photographer could leave.

In my many years of doing interviews, the photographer would have to wait till the interaction was over before he got the chance to do his work. On this day, since it was not a journalism-related meeting, I got the photo shoot done at the beginning.

We began talking. Arif Mohammed bemoaned about how Keralites, so intelligent and dynamic, are forced to leave the state because of a lack of opportunities. “In Pune, I met four Keralites who are big industrialists, and they all had to leave Kerala. I met students too, and they said there was no possibility of getting a good education because of the interference of the students’ unions. There are strikes all the time. A two-year course is completed in three years.”

Soon, I spoke about my book. And I ended it by saying, “Sir, I know you prefer reading books on history and biography, but I would request you to read this.”

He read the contents on the back flap and said, “Very interesting. I will definitely read this book.”

In the middle of our conversation, he said, “What would you like to drink?”

I opted for lime juice and immediately he stood up, went to the door, and passed the request.

I always read up about the people I meet. So, I asked him about his experiences as the president of the students’ union of the Aligarh Muslim University (AMU).

His eyes lit up, a smile broke over his face as he spoke fondly about his college days. I mentioned to him that a book on AMU had been written by Times of India senior assistant editor Mohammed Wajihuddin. “Oh yes, I have read the book and I know Mohammed Wajihuddin,” he said.

It was a nice and interesting conversation.

It seemed to me, unlike most politicians, the governor valued an insightful conversation and an exchange of ideas.

June 21, 2023

Many thanks to Shashi Tharoor for his kind words

Pleased to receive a copy of “The Stolen Necklace” from journalist @Shevlin_S, the true-life story of a gross miscarriage of justice in Kerala, when an innocent man was jailed and ruined on suspicion of being a necklace thief. This was a result of a shoddy investigation that relied on his passing resemblance to the real culprit on CCTV footage. Shevlin Sebastian writes well, & the story is full of lessons for our policing and justice systems. @HarperCollinsIN

https://twitter.com/ShashiTharoor/sta...

June 16, 2023

Many thanks to Deccan Chronicle for this interview

Kochi-based Shevlin Sebastian, a journalist for over three decades, has published four novels for children. Deccan Chronicle spoke with the author on the release of his latest, ‘The Stolen Necklace’.

Excerpts

Q. How did you come up with ‘The Stolen Necklace’?

A friend saw a news story and forwarded it to my agent, Anish Chandy. Since it was a Kerala-based story and I live in Kochi, Anish forwarded it to me. I immediately found it an intriguing story.

The book narrates the real story of V.K. Thajudheen, a middle-aged man from Kannur, who was wrongfully incarcerated for an alleged necklace theft, mistaken for a thief based on a CCTV image in 2018. It recaps the horrific story encompassing all its life and drama. The local police, smug at apprehending a criminal in record time, wanted a confession. How people and resources (social media) stood up for him and got him free after he languished in jail for 54 days is the crux of the story.

Thajudheen is everyman.

Yes, one reason I did the story was because I instinctively knew that what happened to Thajudheen could happen to me or you. It was a nightmare for a middle-class person. Anyone who reads the book will know what a traumatic experience it had been for him and his family. So I am glad I wrote the book.

Did you follow the case as a journalist?

Sorry, no. The event took place in North Kerala, while I live in South Kerala, although that might sound like a lame excuse.

Politics, power, police, prejudice shape the book.

In our society, the police get extraordinary leeway. If they are found guilty of excesses, they do not even receive a rap on the wrist. As a result, they feel they can behave in any way they want. It is a continuation of the British (colonial) mindset. They are rulers and we are the ruled. So a change in mindset is required. This can be done through refresher courses, which should emphasise their role as a service provider to society. To maintain law and order. Nothing more, nothing less.

HRC reports 374 cops face criminal prosecution in Kerala. True?

In a newspaper report in January this year, the number of police officers facing criminal charges has shot up to 830. This is, of course, extremely disturbing for the moral health of society when law enforcers become friends with law breakers.

What were the challenges and difficulties in dealing with real characters and names?

For a few people, we changed their names because they wanted privacy. I spoke with most of the people featured in the book, in-person and over the phone, to record their replies accurately. Using a digital recorder helped me.

Two faces of new tech: CCTVs framed him; social media got him justice

Yes, that is true. Tech can cause damage and tech can also save your life.

Do you think this book will bring attention to the sufferings of people wrongly convicted?

Yes, very much. When you read the book, you will get a picture of what a family goes through when its breadwinner is arrested suddenly and without warning. I believe Thajudheen and his family have not fully recovered from this devastating blow. I hope that when police officers read this book, they will also realise the impact of their actions. And I hope they will be careful in their behaviour in future.

In 2018, India reported 70 custodial deaths. Inquiries were done only in 27. Kerala was one of six states that shied away from inquiries.

That is no surprise. All governments will protect law enforcement because it is a powerful arm of the ruling party. But as a result, this protection, at all costs, results in grave injustice and tragic situations. Ideally, law enforcement should be an independent force. Nowadays, politicians at all strata of society interfere with the workings of the police.

Kerala’s passion for football

Yes, Kerala has a tremendous passion for football, especially in the North. I could see this when the World Cup was held last year in Qatar. Fans put up huge placards of Lionel Messi and Cristiano Ronaldo all over the state. And Messi fans became ecstatic when he lifted the World Cup for Argentina. Football is an enduring passion in Kerala.

Journalists and authors have different styles of writing. How did you adapt?

I used both styles. I am also a short story writer and have published four novels for children. As a friend said, after reading the book, I had mixed the journalistic and literary style of writing.

How do you weave fiction into a non-fictional narrative?

I always imagined the anecdotes which Thajudheen told me as scenes, like in a work of fiction or a movie. Hence, I could impart a fictional narrative to what is a true story. I started my blog. ‘Shevlin’s World’ in 2005. Till now, it has received nearly 24 lakh hits. It contains all my journalism and creative work.

Do you research before writing or while writing?

I do both. Sometimes, while writing, I come across an interesting point. Then I do research on it, in order to get more information.

Your writing process. Plotting and planning.

There is a bit of plotting, but mostly, I try to get into a flow where the writing happens naturally.

Book: The Stolen Necklace: A small crime in a small town

Authors: Shevlin Sebastian and V.K. Thajudheen

Publisher: Harper Collins Publishers India

Pages: 249

Price: Rs 399

June 11, 2023

June 6, 2023

Itâs always better to remember your roots

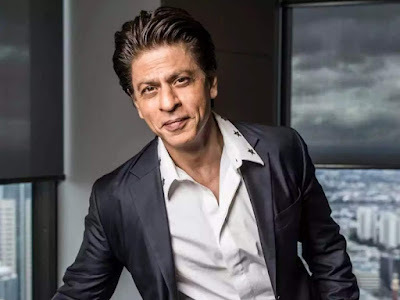

Photo: Shah Rukh Khan

By Shevlin Sebastian

A friend told me a journalist met a famous politician. He asked her how many Twitter followers the newspaper had. She mentioned a number. He smirked and said, âI have double that. So why should I talk to you and waste my time?â

I had a similar experience. A few years ago, a famous woman police officer came to Kochi from Delhi. I met her to do an interview. She asked me the same question about the number of followers the newspaper had. I made a guess. She also smirked and said, âI have double that of your newspaper. Is there any need to talk?â

Her words stumped me, and I remained silent. No interview took place. It was only a day later that I came up with a riposte. I should have said, âMadam, it was the media which made you famous. You are biting the hand that fed you.â

This is familiar behaviour. For over three decades, I have seen many people in sports, arts, politics, literature, and films who have come to newspaper and magazine offices in search of coverage. Sometimes, they got it. Sometimes, they didnât. But once they became famous and successful, they would keep the press at bay, even the ones who provided coverage at the very beginning.

Being ungrateful is a widespread human trait. About 99 percent of people are ungrateful to the people who helped them on their journey. Too many of them have also pretended they did not climb the ladder to success. They seem to indicate they reached the top by magic. This is dehumanising. By refusing to acknowledge your roots, you damage your inner self.

One who seems to have kept his head on his shoulders is superstar Shah Rukh Khan. On Instagram reels, you can hear him say that there were many people who played a role in his success. It was not a one-man success story. Without the contributions of others, he would not have become the star he became.

Shah Rukh always spoke about the need to spend time with yourself at least once a day, to get an inner perspective and balance. In that way, he was able to counter the intense adulation that would have swept any other man aside. âThereâs a personal me, thereâs an actor me, and thereâs a star me,â he said.

Shah Rukh has kept outward success from contaminating his soul.

Fame, power and money. These are the three most dangerous things in the world. If you get an overdose of even one, it can send you into a tailspin. It is the rare human being who can remain unswayed and remain true to his inner self.

Once you get swept away, your ego gets bloated up, you think no end of yourself; you preen and surround yourself with sycophants. This has a tragic effect. Your intuition goes to sleep as your sense of importance runs rampant. That is when you make career mistakes and errors on the home front. Within a few years, you are unwanted and sometimes you become a laughingstock. Your career comes to a stop. Many turn to drink and drugs and professional sex for solace.

For all those people who are in the limelight today, they need to ask a simple question. Who was in the limelight ten years ago? Those names are no longer there today. They should ask a supplementary question: where are they now? Answer: Nowhere.

Here is a cautionary tale. Rajesh Khanna, the first Bollywood superstar, had 15 solo superhit films between 1969-71. He had become a craze all over India. Women begged him to marry them. Producers kowtowed to him. Directors begged him to act in their films. Ten years later, his films were coming out but they no longer rocked the box office. He had become a has-been.

Imagine how many actors started at the same time as Bollywood superstar Amitabh Bachchan. Where are they now? Some may have died. Others have faded away. Amitabh is one of the rare artists who has stayed relevant and popular over the decades. But for a few years in the 1990s and 2000s, it was touch and go for him.

After setbacks on the professional and financial front, Amitabh anchored a quiz show, âKaun Banega Crorepati.â That became a superhit and revived Amitabhâs professional career and financial resources. Imagine what would have happened if that had flopped? He would have headed towards oblivion and irrelevance.

So both the politician and the police officer at the beginning of this story should partake of a small dose of humility. Otherwise, they will inadvertently press the self-destruct button and become has-beens.