Shevlin Sebastian's Blog, page 16

December 20, 2022

When stories die

By Shevlin Sebastian

On some evenings, when I approached Sunny Uncle’s house, on my two-wheeler, I could sense my wife sitting behind me, making a movement. When I turned to look, she was waving at Sunny Uncle.

He sat in a plastic chair on the porch of his house and waved back with a smile. Sometimes, when she waved, he did not wave back. That’s because he had nodded off. Sunny Uncle was not in the best of health. His wife had died four years before, a victim of cancer.

He lived alone, this broad-shouldered man with curly hair. Like many Keralite families, his children lived abroad with their wives and children. A maid came during the day, swept and cleaned the rooms, provided meals and left in the evening. Then her husband came to spend the night, so that Sunny Uncle would not be alone. Like most men of that generation, he found it difficult to cope without the emotional anchor of his wife.

Over 60 years ago, like many Malayalis, Sunny Uncle travelled to Kolkata to seek his fortune. Once, he told me that my father had helped him at the beginning. He would never forget that. Alone, in a strange city, a stranger reached out to befriend him. Anyone who moved to a new city knew that at that moment, you were searching for companionship, preferably from your home state.

Who could have imagined that decades later, they would build houses less than 500 metres from each other in Kerala? Both had done well. In the end, Sunny Uncle had to spend his time alone. In the earlier years, Sunny Uncle would head out for a morning walk. I would see him from my first-floor veranda. If he looked up, I waved. Otherwise, I would let him be with his thoughts. Then the walks stopped. And he remained house-bound.

A couple of months ago, Sunny Uncle was not on the porch. There were several people in front of and inside the house. Then we got the news that Sunny Uncle had passed away. He had spent a few days in the hospital because of heart ailments. Then his heart stopped beating.

He was 86.

On the morning of the funeral, I stepped into the house. Sunny Uncle was lying on a flower-bedecked table. He did not look sad or happy. Maybe he was happy to leave the planet. Sunny Uncle may have felt the time had come. And he was ready.

I don’t know Sunny Uncle’s children, as I have never interacted with them.

Today, the house is shuttered. But the chair remains on the porch. It looks forlorn without its occupant. My wife feels distressed when she sees that. Being reminded of death isn’t always pleasant.

Sunny Uncle’s children have re-entered their lives abroad. They may come later and dispose of the building. Their father lies six feet below, his coffin surrounded by mud.

But what we rarely reflect upon when a person dies is the hundreds of stories, from his life’s experiences, that have vanished into the ether.

When you grow old, you move from the centre to the periphery of the family. You can see this at family gatherings. The older generation sits to one side, next to each other, watching the proceedings. Meanwhile, the youngsters dominate the conversation and are the centre of attention. And they tell their stories animatedly.

They are not interested in the stories of the elders. And they don’t care. The youngsters have money, power, and jobs. They don’t need to show any deference to the old. The subtle message is goodbye, old man, it’s finito. Head to the shadows, uncle. We love you, but you had your time in the sun. Now it’s our turn.

This is a loss for the younger generations. The elderly have fascinating stories to tell. The young could learn valuable life lessons from them.

The other day, I met CV Anthony, 75, a retired contractor, who lives in our area. Every morning, for the past 10 years, the grey-haired man has been feeding stray dogs at dawn. And, as we started chatting, he told me a lot about the psychology of dogs. When they see you once, they will not bark again. Anthony said they had an excellent memory.

When asked why dogs attack people a lot these days, in Kochi, he said it was because of starvation. Anthony said that, in the olden days, people would place leftover food outside the gate. The dogs would come and eat it. Now they put the excess food inside a packet, make a knot at the top and throw it away. As a result, the dogs cannot access it.

He also said that if a dog growled at you, it was wise to stand your ground and make a clicking sound with your mouth. The dog will relax immediately. Anthony said dogs respond to the tone of voice. If you talk roughly, they will get aggressive.

Anthony is brimming with stories. He told me the economy is in such terrible shape that many poor people cannot feed the dogs. In urban areas, it is the poor who care for dogs, not the middle class or the rich, he said.

This conversation proved enlightening for me.

A few days later, I stumbled on to another story.

Annamma (name changed), a lady in her mid-sixties, lived in our area. She asked whether she could go with us in the car, to attend a wedding reception for the son of a former neighbour. The event was taking place 30 kms from the city.

So, when we were travelling, my wife asked about her daughter. For the next hour, Annamma spoke nonstop about her daughter. At age six, she contracted meningitis, and became paralysed, but her brain was intact. She could not speak, but could hear.

Annamma had been looking after her daughter for the past 28 years. She said that she always picked up her daughter from the bed to place her in the chair. But many years later, as her daughter grew and became a woman, Annamma experienced severe pain in her arms. She sought treatment, but the pain persisted. Now, her son who lives abroad, has sent a manual pulley. Annamma can lift her daughter using this system.

You can imagine the mental strain of looking after somebody 24 hours a day for several years. Annamma told us many stories about her daughter. Whenever Annamma stepped out, she would have to come back and talk to her daughter about all her experiences.

As for Annamma, it was clear she never told her story to anybody outside of her family. And there was a feeling of catharsis in her. She had all these intense stories bubbling inside her mind, but nobody was there to hear them. Now, finally, there was a group of people who were interested.

We were glad we could hear it.

Finally, Annamma turned to my mother, who was sitting near her and said, “Amma, you have not spoken.”

My mother, a dazed look on her face, said, “I was listening to you.”

On another occasion, during a family get-together, I met a distant relative who works in a bank. When I asked which section he worked in, he said it was in the loan default section. “That would be interesting,” I said.

He nodded and told me a story.

A resort near Kottayam had taken a loan. The owners kept defaulting on payments, even though the company was doing well. There were guards outside the resort. They prevented bank officers from entering the property to submit the repossession letter.

One day, an ambulance, with sirens blaring, approached the gate of the property. The driver told the guards that he had received an emergency call. So the guards opened the gate. A few bank officers, as well as private guards, were inside the ambulance. They entered and captured the property.

The owners immediately agreed to a compromise. They cleared the dues. It appeared they had the money but were investing it in the business. So, using an ingenious method, the bank settled an outstanding loan.

So, friends, this is what I learned. When you meet anybody, be it a friend or stranger, we should look to ‘hear’ stories rather than tell ours. That will make the encounter far more enriching. You will be able to avoid the tittle-tattle that we usually do at get-togethers.

December 8, 2022

A tribute to a mentor

Photos: George Abraham; KM George; Kunjamma; George Abraham with his extended family; with his wife and sons

After paying a visit to the home of George Abraham, former Deputy Resident Editor of the New Indian Express, Kochi, a desire arose in me to write about his life. I remembered what AM Chacko, the father of former Resident Editor Vinod Mathew, told him, “There is no point in talking good things about me after I die. Then I cannot hear it. So, better do it when I am alive.” So here it is. Marathon Man George Abraham, former Deputy Resident Editor of the New Indian Express, Kochi, relaxes after his 40-year plus careerBy Shevlin Sebastian On the afternoon of November 5, I saw a slip near the door of my house. When I picked it up, I realised it was from the Speed Post. Since they could not meet me, they asked if I could collect the parcel from the Edappally office. I groaned to myself that now I would have to make the trip. That night, as I watched the Spanish hit series ‘Velvet’ on Netflix, apropos of nothing, I thought of George Abraham, the former Deputy Resident Editor of the New Indian Express. George Sir lived near the post office, on Chandrathil Road in Kochi. I sent him a message asking whether I could meet him. He replied, “Yes, please.” So, the next day, at the appointed time, I arrived at his house. On a low table, there were three newspapers. He pointed at the New Indian Express and said that the local reporting continued to be very good. Soon, we were in full flow. We talked about the current political shenanigans in the state, the alarming drug use among youngsters, the isolation of the elderly, and news about former colleagues. George Sir’s mind was curious, alert, intelligent and focused. “I was lucky to work for the Indian Express, which later became the New Indian Express for 40 years,” he said. “I worked till the age of 65, then had a five-year freelance online editing career. I am 74 now.” In my career, the most interesting people I met were artists. The next group were journalists, who also have keen minds and lots of interesting experiences to recount. George Sir was no different. He lived in a large two-storey house. At 11 a.m. a maid came in. She stayed till 2 p.m., and then left. After that, George Sir lived alone. The reason he lives alone is that on February 4, 2020, after a brief illness, his wife Molly, who had worked in a bank, passed away at 67. They had been married for 43 years. Thereafter, George Sir experienced a deep sense of loneliness. “The loneliness is hard to bear for a person who has led a happy family life,” he said. “It struck me like a lightning bolt. I never expected my wife to depart so early, even though she had some health issues.” He realised that this was the fate that strikes every person at one point or the other, with none of the family members nearby, including children who are far away at their workplaces. What has sustained him is his spirituality. “The biggest enlightenment comes when one’s mind reaches a higher consciousness and finds the essence of the all-powerful force that operates in the universe,” said George Sir. “It is a force that can lead one from darkness to light, from ignorance to knowledge, and from misery to bliss. It will enable one to see life and its forms in a better and truer light. I have understood that every person reflects God. One thinks of a higher purpose in life and the pursuit of it, instead of living for the moment or for momentary pleasures.” But he admitted that to reach such a stage had been arduous. “It requires the shedding of the old baggage of thoughts and ideas accumulated over a lifetime, but the ultimate result is peace of mind and harmony with the world all around,” said George Sir. “When one can remove worries, anxieties and fears, it can lead to physiological changes, like normalising blood pressure and sugar levels.” As George Sir embarks on a spiritual journey, his children are leading the practical life he had lived for so many decades. Among his two sons, the elder, Abhilash, is in Toronto. He is married to Ruby Shanker, whom he had met in Dubai, and they have a two-and-a-half year-old daughter Ziva. Anil works in Doha. But in the past few months, Anil’s wife, Betsy Maria Josephine, and children, eight-year-old Anya, two-and-a-half-year-old Xavi, and Reya, six months, have been staying at George Sir’s house. Anil had moved from Dubai to Doha. Authorities were not issuing family visas until the conclusion of the World Cup football tournament on December 18. So, Anil’s family stays with George Sir. The day I arrived, Betsy had gone with her children to visit her sister in Maradu. After two hours of conversation, accompanied by cups of tea, George Sir came with me to the gate to bid me goodbye. Just then, a car rolled to a stop. It was retired Professor S. Muraladheeran, who had a busy career as a guest lecturer. As soon as George Sir introduced me, we started chatting. Prof. Muraladheeran said, “I am the only neighbour to whom George talks.”This did not surprise me. In the office, we knew George Sir for his reticence. For decades, George Sir managed the stress of the daily deadline calmly. But it can be a crushing pressure and doing it day in and day out for decades together can take a fatal toll. George Sir’s long-time colleagues on the editorial desk have died in their fifties and sixties. They include V Vijaykumar, M Kesavan Nampoothiry and MS Rajan. George Sir was a mentor to me. He encouraged and occasionally complimented me on my writing. Aware that I am sensitive, he always spoke in a polite and low-key manner. It soothed me to see his kindness and respect. George Sir was also a superb writer, but he did not write often. Somehow, it was his shyness that prevented him from doing so. But when he did, he used clear, concise and crisp sentences. This was clear in the two eloquent memoirs he wrote in which he mentions about his life and career.In one book, he wrote that his six brothers and their parents were living a peaceful life in the village of Kumplampoika in Pathanamthitta district. Soon, the most traumatic event of their life took place. This was how George Sir described it: ‘It was the evening of a hot day in March 1959. The sun had disappeared from view over the tall hills surrounding our house and darkness was about to settle over the earth. A taxi drove up and stopped opposite our house on the metalled road that stretches up to Chengara Estate. In those days, cars rarely passed on that road. ‘In the car was our Achayan (KM George), who had lost consciousness while undergoing treatment in the Trivandrum Medical College, where he had been taken two weeks earlier during the last stages of his terminal disease—cancer. ‘Uthimoottil Uppappen had accompanied him as we were children. But few people, especially Amma, had any idea about Achayan’s disease. On the night before we took Achayan to Trivandrum, I saw Uthimoottil Kochuppappen crying alone in a room in our house. I did not understand why, as I was a fifth standard pupil. Many important people from the place, including Munshi Sir of Nirayannur, had come to our house that evening. ‘Amma was sure that Achayan would return fully healed as she was getting letters from Uppappen, that Achayan was getting better. ‘As soon as the car came to the road, Kizhakkekoottu Chedathi, wife of our neighbour Samuelchayan, came running and told Amma that Achayan had passed away. Amma was stunned, and she fell back, but Chedathi supported her and helped her lie on a bed. Joychen and I, who were playing in the courtyard of our house, heard the cries of Amma and Chedathi. Joychen was studying in the third standard. ‘Kunjoonju, a daily wage worker of our house, rushed in from somewhere, took a cot and went to the road. We too understood that Achayan was no more and started crying loudly, asking, “When will we be able to see Achayan again?” ‘Amma’s fortitude, courage and strong faith came to the fore. She stopped crying and told us we could see Achayan in heaven. Hence, we stopped crying. ‘Achayan remained in an unconscious state for two more days and attained eternal rest on March 18, 1959. Achayan was 45 and Amma 39. ‘Vellichachen (George Mathew), the eldest of seven sons, was 15. Achayan died on the day his SSLC exam was to begin. He did not write it but appeared for it in September and passed it. ‘Till Achayan’s death, Amma was living like his shadow. Amma, who was teaching in a government primary school, would hand over her entire salary to him. She was happy taking care of us, the children, and managing the kitchen, besides doing her work as a teacher.’Eventually, it was their indomitable mother Kunjamma who kept the family together. In his memoir, George Sir writes, ‘When Achayan died, she was the only earning member of her family and she could educate all of us just because of her job. And now in her nineties, she draws a respectable pension. I dread to imagine what would have become of our situation without a job at a critical period of our growing stage, her dedication and willingness to work hard’ (Kunjamma died on February 11, 2017, at the age of 97). George Sir admits his father’s death had a profound impact on him. One direct consequence was that he became silent. His mother would call him German Kaiser, or a ruler who spoke little. After his father’s death, his mother taught in a school in Punalur (43 kms away). She would come home every weekend. When she had to leave, George Sir’s elder brother Kochachen would run after her, crying, “Amma, please don’t go.” As for George Sir, he stood at the door showing no emotion. In his career, people knew him as a man of few words. In his memoir, George Sir acknowledges this trait. ‘I was soft and did not assert myself often,’ he wrote. ‘When other editors were mostly ruthless and stern, I had a very humane approach. This had its advantages too as I could win the trust of my colleagues. The editors who were successful in asserting themselves by pulling up everyone for anything and everything sometimes drew negative results too.’ George Sir elaborated on the editorial process, the emergence of women in the workplace, and how this led to romances and subsequent marriage break-ups. He lamented about how alcoholism destroyed the lives of many talented journalists. George Sir also highlighted the various events in our nation’s history, post-Independence. George Sir also wrote about unusual events, like staffers writing anonymous letters to management. ‘Writing anonymous letters is a bad practice,’ George Sir said. ‘It is resorted to by persons who have some score to settle with someone but lack the courage for a direct confrontation. In many offices, such letters are sent without names or under some fictitious names to the top authorities against some members of the staff. ‘That happened in my office and against editors, including myself, by those who nursed a grudge against us for no reason or for some action, like issuing memos. But, mostly, such letters were ignored or sent back to the editor concerned.’ He also wrote about how people would come to the newspaper office in search of coverage. “Once in the early nineties, a very handsome person walked into our office to meet the then editor,” said George Sir. “He was an upcoming young actor struggling to establish himself in the film world. He came in without looking at anybody and straightaway went to the editor’s room. He also left in the same way. Later, a feature about him appeared in the newspaper, which boosted his image.”This was none other than Jayaram, who became a popular actor later.Even politicians landed up for coverage. In 2012, a short man entered the cabin of George Sir holding a file. He wanted coverage for a Dalit conference he was organising in Kochi. Neelalohithadasan Nadar had caused a scandal for his alleged advances towards a female IAS officer, Nalini Netto. ‘None of the political turmoil he had faced was clear in his behaviour,” wrote George Sir. ‘He appeared very calm, confident and pleasant. That showed what kind of stuff politicians are made of. They thrive, despite the worst setbacks, although they may vanish from public view.’ There are many such anecdotes in both his memoirs. Ultimately, George Sir reveals himself to be a man of kindness, honesty, sincerity, and magnanimity. Kudos to you George Sir for a life well lived!December 5, 2022

Out of 398 entries, happy to be in the longlist of 16 for the Himalayan Writing Retreat flash fiction contest, in association with The Story Cabinet.

Painting by Andrew Ostrovsky

The following story was also published in The Story Cabinet.

https://readstory.page.link/MXCqoTkboC3CUnpT6

Darkness

By Shevlin Sebastian

Lata Bhonsle was striding down a deserted street in Bandra, Mumbai. She could hear her heels making a ‘click clack’ sound. Wearing black sunshades, she was heading towards a taxi stand. It was a humid day. She could feel a hint of perspiration on her forehead.

She glanced at her watch. It was 9.45 a.m. She was late for work.

She did not notice a white Maruti van which glided up. The side door slid open. The next thing she realised, through the corner of her eyes, were three men who jumped at her. One man clamped a palm over her mouth, while the other men grabbed her shoulders and legs. Her first reaction was to hold on to her Hidesign leather bag even as her sunshades fell to the ground. They pushed her inside the van. She could sense her frock ride up. Two men were burly, while the third was a slim man. They all wore cloth masks, with slits.

“Band karo,” said a burly man.

The slim man shut the door with a bang. Lata saw them look around through the windows to see if anybody had seen them. She felt a stab of pain as the man pressed harder on her mouth. She heard the driver shift gears. It seemed as if somebody cracked a knuckle. The van jerked forward. The slim man pulled out the cork of a small glass bottle. He sprinkled chloroform onto a piece of cotton. A sweet odour spread in slow motion inside the van. Then the man placed the cotton under Lata’s nose. Lata tried to stop breathing. But in less than five seconds, she gave up.

Soon, she closed her eyes and drifted off.

Forty-five minutes later, the van reached the compound of an abandoned cotton textile mill in Lower Parel. They parked in front of a large and empty shed. Grass was growing against the walls of the shed. The paint had peeled off to reveal the red bricks underneath. A rat skittled away into the undergrowth. They carried Lata inside and placed her on a dirty mattress…

When Lata awakened, two hours had passed. She looked up and saw the iron girders below the sloping roof. There was brown rust on them. She looked down at her body and saw her thin maroon panty. The men had pushed it to one side before entering her. She saw the frock lying on the ground. She sat up. The veins at the side of her forehead throbbed. She rubbed her forehead in a circular motion with her fingers for a few moments.

Dimly, she had been aware that men had climbed on top of her. She had heard grunts and moans. Lata touched the edges of her vagina with her finger and felt a soft and recurring pain. Her body gave off an odour of perspiration mixed with her Versace Bright Crystal perfume. It made her want to retch, but she controlled herself.

They had not taken off her heels, making it hard for her to stand up. So, unhooked her heels before standing up. Then she put on her dress. She looked around and saw her handbag lying against a mound of raised mud. She picked up the bag and smacked her handkerchief against it to remove the dust.

She pulled open the zipper. Incredibly, the rapists had taken nothing. Her leather purse was there. Her debit and credit cards were intact, along with a plastic comb, house keys, a lipstick holder, a packet of tissue paper, and a mobile phone. Inside a white envelope, there was Rs 8000 in Rs 500 notes.

Lata pulled out a face mirror. The lipstick had run out of her lips, towards her nose, creating a red mark that looked like a scar. It looked like the men had tried to kiss her. Lata cleaned it off with a tissue paper. She used another tissue paper to wipe her face.

Lata stepped forward. On one side she could see old wooden looms, all dusty and silent. On some there were large cobwebs. They seemed to have remained undisturbed for a long time.

It was difficult to walk on the grassy uneven ground on her heels. But she gritted her teeth and moved forward, hobbling now and then. Lata walked for ten minutes.

She exhaled when she saw the rusted gate in the distance.

Her breathing slowed down as she made her way to the main road. She flagged a cab and asked the driver to take her to Bandra.

It was an ordinary day. Sunlight reflected off the windows of buildings. There was the blaring of horns. People rushed past each other on the sidewalk. But for Lata, there was nothing ordinary about this day.

The rapists had puzzled her because they had stolen nothing. So, were the men only interested in the rape and nothing else? What type of men were they? Those who usually indulged in these activities were career criminals. They would have definitely emptied her handbag. She kept tapping her lower lip with her fingertip. A hundred thoughts raced through her mind.

Was this a planned rape, or did the men pick her up in a random selection? Sexy woman + deserted road = grab her? Lata thought the latter explanation seemed more likely. She did not have any enemies. Nobody who knew her would harbour so much anger that they would arrange for men to rape her. Lata knew she did not have a personality that ruffled people.

She messaged the office, saying she would be late.

Lata reached her fourth-floor flat at Bandra.

She undressed and turned on the shower. She remained under it for a while, wanting the pinpricks of water to clean her soul as well. Tears gathered in her eyelids and then rolled down her face, mixing with the water. Finally, she took a soap and lathered her body.

It took her an hour before Lata sat down on the edge of her bed clad in a pink bathing robe. She wondered what to do.

She called her company CEO, Rekha Mehdirata.

Rekha, with striking doe-shaped eyes, had risen through sheer drive, talent, and ambition.

Lata, who was senior vice president of marketing, told Rekha about what had happened in a low voice.

At the conclusion of the narrative, Rekha said, “I don’t know what to say, Lata. Mumbai has always been a safe place for women, even late at night. And to think this happened in broad daylight.”

Lata remained silent. Yes, these were the thoughts she had, too. Mumbai has always been safe for women.

Finally, Rekha said, “Lata, what do you want to do?”

Lata stared at her bare feet placed on the brown-tiled floor. The maroon nail polish on her narrow toes made her feet look sexy.

She processed the pros and cons of any sort of action. Finally, she said, “I should file a FIR against unknown persons. There are CCTV cameras in Bandra, although I am not sure there were any on the road on which they captured me. The police could find the van’s registration number on other cameras.”

Lata could hear Rekha’s breathing through the phone. It seemed to be a stutter. A rush of breath followed by a complete halt.

“It’s a risky business,” said Rekha. “These people can be dangerous. But if we don’t fight back, they will attack other women with impunity.”

“I am scared,” said Lata. “But I don’t want them to get away with this assault.”

“Take leave for a few days,” she said. “File the FIR. You might have to go to the hospital so that the doctors can examine you and give a certificate of penetration. If they can locate semen, that would help your case.”

Lata nodded, even though Rekha could not see it.

Both of them were discussing this matter-of-factly. But Lata knew somewhere deep inside her she was in a state of shock, as well as denial. Did all this happen to her? Was it a dream? And why did it happen? What did they do exactly?

She lay down for a nap.

Two hours later, when she woke up, her brain felt foggy. The sleep had made it worse. Whom should she turn to for emotional support? How to tell people about this? If she told one woman friend, the news would spread. Soon, all her friends would give her sympathetic looks.

If she filed an FIR, it might come out in the media. The police would leak it because reporters are always looking for juicy news. And what would happen anyway? The police will do a desultory investigation and use delaying tactics.

Lata would have to hire a lawyer and launch a crusade to get the police to react. While she would do this, she would have to contend with the pressures of her career. And will the bosses and the owners like this negative publicity? On top of all that, she would have to battle it all alone emotionally.

She was in a cul-de-sac.

It would devastate her parents in Bhopal. Her grey-haired mother, Sumati, will immediately say, “Beti, get married. Don’t live alone. Have children. They will bring meaning to your life. Family is more important than a career. At the end of your life, when your career is long over, only the family will be there for you.”

‘What sort of family,’ thought the 36-year-old.

Lata had seen so many marriages implode because of infidelity. Which child today is going to look after their parents in their old age?

The joint family had collapsed. India was going the Western way of individualism. Everybody was thinking of themselves only.

She could hear growling sounds from her stomach. She looked at the wall clock. It was 4.30 p.m.

Lata had eaten nothing since her breakfast.

She took out her mobile phone from her bag and ordered American chop suey on Zomato.

Later, as she ate with a fork on a low side table, she watched a Netflix movie. But she could hardly follow the story. Her mind remained blank.

As night fell outside, she switched on YouTube on her mobile phone. Lata listened to the Tibetan Buddhist chant, ‘Om Mani Padme Hum’. She listened to this every day. It brought her tranquillity, to hear the word ‘Om’. She had read somewhere that ‘Om’ was the most powerful word in the universe.

A horrible event had taken place.

She would have to deal with it.

She felt she needed to sleep over it before she decided. Let her unconscious mind think about the best actions to take.

So, she went to sleep, but not before adjusting the air conditioner to mild.

The next morning, when she awoke, she could feel her mind had become clear, like it always was. And which had enabled her to be so successful.

Lata came to some conclusions, as she made an omelette on the kitchen range.

She would consult a top psychologist. Lata was hoping to work her way through the damage to her psyche.

She would not file an FIR. It was too much of a headache. If the news became public, these criminals might kill her.

She would be very careful when she moved about. It would always be in a cab or auto-rickshaw. No walking anywhere, unless she was in a group.

And she would request Rekha to keep this a secret.

Lata was not in a relationship. She had not been for a few years. So, she knew her career would provide the distraction that she needed.

‘These are the decisions for today,’ she thought.

She slid the omelette onto a plate using a wooden ladle. Then she put pieces of bread inside the toaster and pressed the lever downwards...

November 28, 2022

From where to where -- a short story

Illusutration is for representational purposes only

By Shevlin Sebastian

Shampa Banerjee wore a shimmering red chiffon saree. Her smooth, long black hair fell like a waterfall down her back. She had loaded up the jewellery: a gold nose ring, a gold necklace and gold earrings. She wanted her husband to be proud of her. They mingled with other guests in the hall of a five-star hotel in Bhubaneswar.

Shampa had married a top executive working at a mining company.

It was a love marriage. While she is a Bengali Brahmin, her husband is a Malayali Christian. They met at the company office, where she worked as a secretary. She knew it was an instant karmic connection. She was on the plump side, while he was slim and tall, with a goatee and a bald head. He was coming off a divorce from an Anglo-Indian woman, whom he had met in Kolkata. There were no children.

Shampa’s family opposed the alliance. For one, Francis Xavier was already in his forties. Second, they belonged to different religions. But she did not pay heed. Francis had an excellent education. He had a sterling reputation in the company and was moving upwards in his career.

They had a registered marriage. To avoid office gossip, Shampa quit her job and joined another company as a secretary. Both of them did not want children. They wanted to be with each other without distractions. Their sexual chemistry was intense and passionate.

They took time out for holidays whenever they had the chance. They saw movies and attended parties. It was a beautiful time. Shampa could not have been happier. In bed, his musky body odour intoxicated her. It seemed to activate her pheromones. She loved to wake up next to him in the morning, one leg placed across his body.

During the office party, Francis was mingling with the other guests. The company was celebrating superb annual profits. Shampa was conversing with the other wives. All of them wore expensive jewellery and sarees, she realised. That is one thing she liked about the company. Salaries were quite high. They also looked after the staff.

Francis sat on a sofa with his colleague, Anirban Datta. They talked about a recent film called ‘Silver Linings Playbook’. Francis had seen it on Netflix. “It’s a romantic comedy with superb acting by Jennifer Lawrence,” said Francis. “She won an Oscar for Best Actress for it.”

Shampa observed Francis from afar. She felt glad to see him happy.

A few moments later, Francis fell silent. Anirban saw his head lolling on his chest. He held Francis by his shoulders and lowered him to the sofa. When another colleague, who saw this, came up, Anirban said, “Call an ambulance.” The company had numbers for ambulances.

People crowded around the sofa. It seemed clear to Shampa that Francis had lost consciousness. ‘How could this happen?’ thought Shampa. ‘Francis was in good health. Low blood pressure must have contributed to the fainting.’

The attendants carried Francis into the back of the ambulance on a stretcher. The ambulance set out, its siren blaring, for Apollo Hospital on Sainik School Road.

Anirban and Shampa followed in his car.

Both of them saw nurses wheel Francis into the intensive care unit. They sat outside in plastic chairs placed against the wall.

“Must have fainted,” said Shampa.

Anirban nodded.

Unfortunately, that was not true. The doctor, in his white overcoat, came out quickly and shattered Shampa’s life.

Francis had a massive heart attack and died in the ambulance.

Shampa stared at the doctor with her mouth open. She could feel her vision becoming hazy. The blood seemed to race through her head like a tsunami. Shampa grabbed the top of the chair and steadied herself. Anirban immediately put a protective arm around her.

“Unbelievable,” he heard Anirban whisper under his breath.

The next few days slipped by in a blur for Shampa. She had to make funeral arrangements. Francis’s two brothers insisted on a church service and burial. There was no will. The brothers disputed who would be the heir. Shampa said as the wife she should get the provident fund and other arrears. It became a court case.

Shampa realised it would take a few years before the court settled the case. Her lawyer guaranteed her it would be in her favour. She could not blame Francis for not writing a will because he could not have imagined he would die so soon. Such a short but sweet life. How she loved the man. Nine years went past in such a beautiful way.

She had to leave the office bungalow and take lodgings in a cheaper part of town. Her friends in the company drifted away. Shampa could no longer afford the lifestyle they had. She had no option but to opt out. She knew living on her salary would be tough. Shampa had been so used to a high-flying life. She felt she had to move to a city where there were more opportunities. And also, to avoid social humiliation. If she met those wives again, at some mall or the other, they might ignore her. That would be a painful experience.

Shampa had a few college friends who had settled in Delhi. She called them up and asked whether there would be any job opportunities. One of them, Rathi Das, suggested public relations. Shampa felt that would work for her. With her gorgeous looks, she was confident she could charm any man.

Six months after Francis passed away, Shampa moved to Delhi. She took a flat on a terrace for rent in Mayur Vihar. In Delhi parlance, she came to know they call it a barsati. It did not matter, as she did not have to maintain appearances.

Rathi gave Shampa a PR contact. Shampa called him up. He was also a Banerjee like her, called Prasun. He agreed to meet her at a cafe in Connaught Place after work.

Shampa wore a white kurta, blue jeans and Kolhapuri slippers. She had removed all her gold jewellery. She had heard Delhi was unsafe for women. In her Bhubaneswar days, she travelled in an air-conditioned car. But now it was auto-rickshaws, buses and the metro. ‘That’s life,’ she thought. ‘Nobody can avoid hardships forever.’

At night, she missed Francis very much. Previously, she would sleep pressed against him. Now, she only had a pillow to hug. But she knew crying and moaning over a past that no longer existed was a waste of time. She had to survive, somehow. Since she had angered her family with her marriage, she did not want to turn to them for help. Shampa was sure they would have had an ‘I told you so’ look on their faces.

‘F..k them,’ she thought.

She tied her hair up in a topknot. Shampa had kept her hair long because Francis liked it so much. She briefly pondered cutting her hair to shoulder length. That would make it so easy to handle. But she remembered what Francis had told her once, “A woman looks so sensual with her long hair.” So, she kept it in memory of Francis.

Shampa took the Blue Line metro to Connaught Place.

Prasun greeted her with a smile. Shampa immediately liked him like a brother. He had a small goatee, a receding hairline, and kind eyes behind black spectacles.

They ordered a burger each. And a coffee.

When they began conversing, Shampa realised Prasun was a copywriter.

“Rathi heard it wrong,” said Prasun.

Shampa smiled as she bit into the burger. She wondered whether she was wasting her time. And she hoped she did not have to pay the bill.

Prasun was direct and honest. “I assume you are in your late-thirties,” he said. “At your age and with your lack of experience, it will be difficult to get an opening. Do you think you have a talent for copywriting?”

Shampa was silent. ‘Do I have a talent for copywriting?’ she thought. ‘I don’t know. Do I have a talent for anything?’

“Did you study English in college?” asked Prasun.

“Yes, from Lady Brabourne College in Kolkata,” said Shampa.

She could see a look of disappointment in Prasun’s eyes, who had also grown up in Kolkata. Shampa knew her college was not in the Top Three.

“Listen Shampa, I will be honest with you,” he said, leaning forward. “I can only offer you freelance opportunities. If you do good work, only then can I try to convince my boss to take you on.”

‘Freelance,’ she thought. ‘This means very little money. How will I survive? And even if I am capable, how long would I have to wait till I impress Prasun?’

She said, “Prasun, I can do it on the side, but I need a regular job.”

He said, “I understand.”

“Can you suggest anything?” she asked.

Prasun looked into the distance.

“PR could be ideal for you,” he said. “I’ll check with some of my friends. In the meantime, I will send you some work on WhatsApp.”

“Okay,” she said.

Graciously, he paid the bill.

They got up and shook hands. Shampa realised Prasun had soft hands, unlike many men who grip your hand as if they want to crush it.

When she reached her flat, she undressed and slipped into a cotton nightgown. She remembered the see-through thigh-high black nighties and lacy lingerie that she wore. The aim was to get Francis excited. Now she wore cotton nighties with the hem a few centimetres above her ankles.

Shampa lay down on the mattress placed on the floor, the back of her head resting on her palms, and stared at the ceiling. It was an unsightly sight. She could see brown patches on the white surface. ‘What were they?’ she wondered. ‘Nobody has painted this place for a long time. Landlords don’t want to spend money on upkeep at all. Greedy guys.’

The noise of the road below seeped in. She could hear horns blowing and people shouting. ‘Everybody is busy except me,’ she thought. Much later, she would realise it was not busyness, but a harsh, exhausting struggle to make ends meet. And to keep their families afloat.

Shampa had been a feminist. Which is why she resisted marriage. But she wasn’t very career-minded either. So, she was in a nowhere situation now. Shampa had married Francis because she had fallen in love. All her feminism flew out of the window at that point. ‘It had been the right decision,’ she thought. ‘Now God had taken Francis away. What can I do?’

She remembered the famous quote by American film director Woody Allen, ‘If you want to make God laugh, tell Him your plans.’

‘How true,’ she thought.

The days slipped past. Prasun gave her some contact numbers. She met a few people. They asked for resumes. Shampa sent them through Gmail. But the resume was too thin. Nobody called her back. They did not want to take a risk with an unknown person.

Prasun sent her an image and asked her to write some copy. She did so. He did not respond immediately. When she prodded him on WhatsApp, he said it was okay. Prasun went out of touch. If you have no talent, she realised, they were not interested. She wondered whether she should sleep with somebody to get a job. But Shampa dismissed the idea immediately. It was unethical and it would damage her morally.

All her friends were busy with their children, husbands and careers and trying to balance it all. They had no time for her.

Shampa spent many evenings staring at the ceiling. This was to give a rest to her eyes after she had stared at the mobile screen for a long while. She ordered food from Swiggy and ate absentmindedly.

She was feeling the first signs of desperation. There was not much money left. After that, what? Shampa might have to swallow her ego and make peace with her family. Her parents lived in a two-storey house in New Town in Kolkata. They would reconcile because Francis was dead. So, it would be fine.

Shampa was sure they would make another attempt to get her into an arranged marriage, despite her age. There were so many widowers around. For the first time, Shampa did not reject the idea. She felt it would be better to get into a relationship rather than remain in the solitary existence she was living now.

But, for immediate cash, Shampa would have to ask her elder brother Dipankar for help. He was the CEO of a top-notch tech company in Hyderabad. He could send Rs 50,000 a month for a while. But it could not be forever. Dipankar had a wife and two children. It would be unfair to him.

One Sunday evening, to get out of the claustrophobia of staying cooped up in her flat, Shampa stepped out for a walk. Since it was a holiday, there were not too many pedestrians around. She looked up at the sky. It was a clear blue even though it was the winter month of December. A chilly breeze blew. Shampa had covered herself with a shawl.

From the opposite direction, she saw a tall foreigner. He had a shining bald head and sparkling saffron robes. It struck Shampa how calm he looked. She realised he offered the sense of security that every woman craved.

When he came abreast, Shampa said, “Excuse me, you belong to which order?”

The Swami paused and smiled. Nice, even white teeth. Shampa immediately noticed how blue his eyes were. Right in the middle, there was a black iris. It seemed as if it was a whirlpool and Shampa was drowning in it.

The monk said, “I belong to the Shanti Ashram. Have you read the book, ‘My Spiritual Journey?’”

Shampa shook her head and pressed her lips together.

“Our founder, Bhola Nath, wrote it,” he said.

“Where are you from?” asked Shampa, craning her neck to look at his face.

“Oh, I am from Texas,” he said. “Why don’t you come to the ashram to get a better idea?”

“Where is it?” said Shampa.

“In Noida,” said Swami. “We have satsangs, kirtans, spiritual counselling, and meditation retreats.”

Shampa nodded and said, “Can I have your mobile number?”

“Sure,” he said and rattled off his number. Shampa saved it on her mobile phone with the name Swami Dayananda.

“Hope to meet you,” said Swami Dayananda, and smiled at her.

Shampa smiled back.

She felt elated as she carried on walking. ‘Maybe, God had set up this accidental meeting,’ she thought. ‘Who knows?’

Back in her room, she googled and got an idea about the activities of the ashram. She read the Wikipedia entry on Bhola Nath. She realised the monk had settled in Pittsburgh, USA, in 1940 and spent three decades of his life in America. This explained to Shampa the presence of foreigners in their ashram.

As a child growing up in Kolkata, she had missed hearing about Bhola Nath, even though he was a Bengali and had grown up in Howrah. She had been aware of Ramakrishna Paramahansa and his disciple, Swami Vivekananda. Her parents were not overtly religious.

Shampa stared at Bhola Nath’s photo. The late spiritual leader had piercing eyes. She also watched a few YouTube videos.

One week later, she went for a visit.

One of the first things Shampa noted was the silence and the sense of peace that pervaded the place. Everything was so clean. The garden had mowed lawns and trimmed leaves. She called Swami Dayananda on his mobile phone. He came out and took her around. Walking next to him, with his 6’ 2” height, she felt like a pygmy.

He took her to a temple inside the premises, the library, counselling rooms, the kitchen, and the dining area. Swami also led her to the female retreat block and showed her the single rooms. He showed her a block where nuns or sanyasinis lived.

“You should take part in a retreat,” Swami Dayananda said, in his gravelly voice. “There are three-to-five-day courses.”

Shampa nodded and said, “I will.”

Shampa felt herself calming down. After seeing the filth and garbage in the city, she appreciated the cleanliness of the ashram.

Within a fortnight, Shampa attended her first retreat. And she enjoyed it to the fullest. She felt a sense of completeness that she had not encountered with Francis, despite all the bliss she experienced from their relentless love-making. She wondered if the ashram was her destiny. A path to spirituality and bliss.

One day, Shampa spoke to Swami Dayananda about being a nun. He listened quietly and said succinctly, “Being a nun is very challenging. A lot of sacrifice is necessary. So, think hard about it.”

Sometimes, when she lay on the mattress at her home, she imagined kissing Swami Dayananda. To see those blue eyes, just centimetres away. Wow, that would be a great experience. She also imagined the Swami kissing her throat and nibbling her ears. It sent her heart racing.

But soon, she blinked her eyes rapidly, shook her head from side and side, and shut out the images. She knew it was not right to think that way. Shampa was sure that the Swami had no such thoughts. But she had to admit to herself that the monk attracted her.

Six months elapsed. Shampa was a regular attendee. Soon, she volunteered to work as a nun.

There was an interview process. Six monks grilled her. Asked her several questions about her life. She told them about her lack of encumbrances.

In the end, the ashram accepted Shampa. A week after she joined, she woke up one morning with a phrase resounding in her head, ‘From where to where’.

Indeed, she could never have imagined her life would take such an almighty turn. And this happened based on an accidental meeting of a monk on a Delhi street. But as she knew, many great spiritual leaders had asserted there were no coincidences. Everything happened for a reason. But Shampa was honest enough to admit to herself it was her physical attraction to Swami Dayananda that compelled her to go down this road.

She and Swami Dayananda spoke often, but he always kept the conversation at a formal level. Shampa knew the monk was aware of her attraction to him and he wanted to keep her at bay.

Shampa continued to work hard. She felt that, with time and patience, she could lodge herself in the heart of Swami Dayananda.

It was going to be a stern test for the monk.

Few men can withstand the fearsome determination of a woman.

November 24, 2022

PJ Sebastian: commemorating a life and career

Photos: Article in Malayalam newspaper, Deepika; PJ Sebastian in his mid-thirties; the book cover; relatives and well-wishes pay respects at the grave; my great-grandfather

Today, November 25, is my grandfather PJ Sebastian’s 50th death anniversary.

Articles commemorating his life and achievements have appeared in a few Malayalam newspapers.

In the following article, published on March 13, 2007, in The Hindu there is a look at his life.

Democratic struggles

By R Madhavan Nair

An English translation of the memoirs of P.J. Sebastian, who was a frontline activist in social and political struggles in 1930s, has been brought out by C.T. Mathew, the former Director of Government Dental College in Kozhikode.

Sebastian shot into the political limelight as the chairman of Changanasserry municipal council when he was only 29. He was also a leader of the Catholic community and widely appreciated for his skills as an orator. His memoirs published posthumously under the title, `My Life,' would be of interest to all those interested in politics and the growth of the Catholic community.

The memoirs published under the title `My Life,' documents an eventful period in history when democratic struggles were staged to demand a more representational character for legislature and a more equitable share for various communities in Government jobs, which were at that time dominated by Nairs, Brahmins and other "forward communities."

"It is a sad fact that the new generation of Keralites who are now settled in foreign countries are unable to understand books in Malayalam, which contain interesting details about their past. That is why I decided to translate it into English," explains Dr. Mathew, on why he chose to translate into English Sebastian's memoirs.

Sebastian's memoirs were printed and published only after his demise in 1972. The income from the sale of the book was to be donated to the Society of St. Vincent de Paul Central Council, Changanasserry. He had travelled across the State to promote the Society of Vincent de Paul.

Sebastian was born at Changanasserry in 1898. He established a reputation as a powerful speaker and a leader of the Catholic community. Sebastian emerged as a prominent figure in what has come to be known as the "abstention movement" for more representation for various communities in the legislature.

`My Life' also throws light on the last phase of the rule of Diwan Sir C.P. Ramaswamy Iyer and the rule of the first Communist Ministry. Sebastian was in jail when the Diwan left after an assault on his life. Subsequently after self-rule was declared by the Maharaja of Travancore, he continued to remain in jail where he struck a friendship with Mannath Padmanabhan, even though the two had conflicts during the abstention movement. After getting self-rule, he took up prestigious jobs of Public Service Commissioner and later became the Panchayat director. After retirement, Sebastian served as the president of Primary School Teachers Association.

In 1954, he was elected to State Assembly from Kurichi constituency. He led the `vimochana samaram' (liberation struggle) that culminated in the dismissal of the E.M.S. Ministry by the Congress-led government at the Centre.

Dr. Mathew has added a short general history of the period when Sebastian was active in politics and public life. "This would lead to better understanding, especially for those who are not well-acquainted with Kerala history.

(Courtesy: The Hindu)

http://hindu.com/2007/03/13/stories/2007031301910200.htmNovember 11, 2022

Buzz off!

(A story about bees)

By Shevlin Sebastian

One day, my Kochi-based friend and former colleague, Anna Mathews, called me up. She said that the tenants’ association in her building had broken up a hive and there was plenty of honey to be had. She asked whether I was interested.

To entice me, she said, “It’s superb. I have tasted it.”

Since I have the habit of having one teaspoon of honey every day, I did not need too much persuasion.

When I got to her home, Anna poured a bit of honey into a saucer, which had a bit of water. Then she stirred the saucer in a clockwise manner. The honey formed a hexagonal pattern.

“See,” she said, looking up with her expressive eyes. “Genuine stuff.”

Later, at home when I tasted it, the honey was thicker and had a different sweetness, as compared to processed sugar. I was glad I took the bottle.

One month later, I took the last spoon.

And this is the message I sent Anna on WhatsApp:

“Dear Respected Madam, this is to inform you that the last teaspoon of honey is now coursing through my small and large intestines. Please give my congratulations to the lovely bees at JM Manor.

“Sorry to hear they have migrated to Canada under the ‘Essential Workers Category’ to better their economic prospects. The brain drain, I mean, the bee drain of the country, is alarming.”

Anna sent a smiling emoji and said, “So cute.”

The matter would have ended there… but it didn’t.

Anna forwarded it to her cousin Divya who then accidentally forwarded it to the WhatsApp number of the Queen Bee, the leader of the bees. Her antennae quivered, and she flapped her wings ferociously.

The Queen Bee had been angry for some time. She knew many bees were migrating to Canada. Many left without asking her permission. They all said they could not handle the heat, dust and pollution of Kochi. They wanted to settle in a cool climate where the air was pure and the people were pleasant.

So, she called an emergency meeting of all the bee colonies in Kochi.

They all gathered together at the top of a tree at the Mangalavanam Bird Sanctuary near the High Court.

The Queen Bee stared silently at the mass of bees in front of her. Then she leaned into the microphone on the lectern and said, “For some time I have been worried about the bees’ migration to Canada. Indian bees are what we are. We should be proud of our country. We should contribute our honey to the national effort.”

“Madam,” male bee Konda Ranu, a migrant bee from Jharkhand, said, “The way migration is taking place, Canada will become an Indian country. So, we will continue to give honey to our fellow Indians.”

“Hear, hear!” some bees shouted.

The Queen Bee realised there was a lot of support for migration. Like humans, bees were worried about global warming. It was already announced in the ‘Bee Times’ Kochi would go under water including the trees. The general feeling was, ‘Without trees, where would we hang our hives? Buildings are too unsafe.’

Konda continued, “I am told London is run over by Indian bees. Soon, our bees will be all over the world.”

He paused and said, “Madam, don’t get uptight. You should float like a butterfly and not sting like a bee.”

All the bees laughed.

The Queen Bee waited for the laughter to die down and said, “How will our countrymen get honey if we flee? You know my slogan: ‘A self-reliant country is a powerful country.’ You know our tourist tagline: ‘Make a beeline… to God’s own country’. Then how can we flee?”

Konda said, “People should be free to make their decisions.”

Again, several bees flapped their wings in agreement.

The Queen Bee was getting irritated by these constant interruptions by Konda. She knew she would have to get rid of him. Like all leaders, she did not like criticism of any sort. And although, in her bee head, she felt migrants smelt, and kept their hives dirty, and threw garbage all over the place, she would seduce Konda and sleep with him. Of course, if she did that, Konda would drop dead. That’s what happens to all male bees who copulate with the Queen Bee.

To ensure she could entice Konda, the Queen Bee decided that after the meeting, she would go to the Ullu Mall and buy a black bra, thongs, and stiletto heels. ‘That should nail the idiot,’ she thought. ‘Goddamn migrants.’

The Queen Bee knew she did not have the guts and crass outspokenness of American Queen Bee Donna Drump, who openly called for all migrant bees to return to the ‘shithole’ countries they came from. “America is not for black, blue, green, yellow and brown bees,” she said. “We don’t need rainbows here. We only like the colour white.”

Many white bees clapped when she said that. The Queen Bee realised that, deep down, most bees were racist. Even in Kochi, she knew they hated the migrants from the other states. But the Queen Bee did not want to go the Drump way and polarise the bees.

Meanwhile, up in the tree, there was no solution to the migrant question. Should she ban it or not? Maybe, declare an emergency, like she did in 1975, and tell the Bee Police to keep a strict vigil on those trying to escape the country. But again, she was no longer not that type of Queen Bee. She liked her bees to feel free and move around and speak their minds. But not in the insolent way Konda did.

Anyway, the Queen Bee ended the meeting and flew off to the mall.

That night, she invited Konda for dinner.

Konda accepted.

When he saw the Queen Bee in her stockings and thongs and high heels, he could not help but exclaim, “So cute.”

Those were the last words he spoke as he copulated with the Queen Bee.

As she saw the dead bee lying on the ground, the Queen Bee could not help but exclaim, “That’s one bee out of my bonnet.”

November 7, 2022

Getting a gift of an article 30 years later

By Shevlin Sebastian

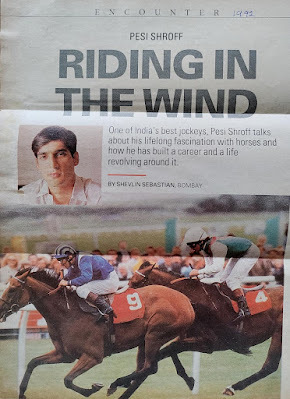

Long-time freelance journalist and my friend, Rudolph Vance, stepped into a musty book shop on College Street, in Kolkata a few days ago. He came across an old issue of Sportsworld. He had been a contributor to the magazine, too.

As he flipped through the pages of the July 1, 1992 edition, he came across an article by me. He sent it to me via speed post.

I worked at Sportsworld for nine years. Those were fun-filled years. We played cricket inside the office after the deadline was over. We put up posters of beautiful sportswomen on the walls. In prime position was a poster of former tennis star Steffi Graf under a poolside shower.

What a body!

Unfortunately, I may be the only former Sportsworld staffer to keep this habit. I always had a poster of a beautiful woman on the wall, and increasingly, as my default desktop image.

Some people don’t grow up.

When I looked at the pages of the magazine that Rudolph had sent, I marvelled that even after 30 years the pages had not completely deteriorated. There were some brown patches on the edges here and there.

When I read the article, it reminded me of a method I used during my time in Sportsworld. The essence would be a question-and-answer format. Interspersed in between, I would put in some mood, and bits of conversation with the subject, so that readers could get a feel for the person I was interviewing.

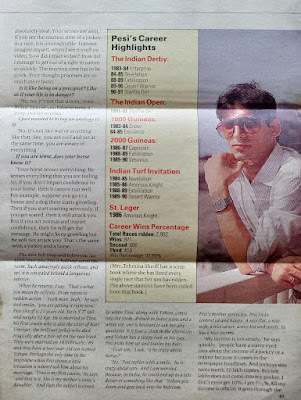

The Pesi article begins with my arrival in Bombay and my call to the Shroff household to learn that he had gone to the airport to fly to Bangalore. But fate was in my favour. I gave the answer later.

In Sportsworld, if I remember right, since we had so many pages to fill, we would write anywhere between 1500 and 2000 words for a story. A typical feature story would run from four to eight pages. Today, journalists would consider 400 words a lengthy story. Of course, for a single newspaper page, 1200 would be fine.

I also read up on Pesi.

In his career, he had ridden 5614 races. He won 1,751 of them, including 106 classic races and 29 Derbys (source: Wikipedia).

His career as a jockey ended in 2004 because of injuries. Thereafter, to my shock and delight, he had embarked on an equally stellar career as a horse trainer and won many races.

It’s uplifting to know that the 57-year-old is still going strong.

November 1, 2022

And Then There Were None -- a short story

By Shevlin Sebastian

Ahiga, the Red Indian of the Cherokee tribe, with a shaved head, stood on a flat outcrop of rock. He was a lean man with bulging biceps. He wore a beaded necklace with the claw of a bison at one end. Ahiga picked up a small piece of rock and threw it in a long arc. He watched it fall to the ground far below and roll for a while, like a squirrel doing a series of somersaults.

When the 25-year-old looked to the left, he could see a range of hills made of rocks and boulders. Between Ahiga and the hills, there was an enormous expanse of red mud. In some places, the land was flat and in other areas, the terrain was undulating. If Ahiga squinted his eyes, he could see the ruts made by the wheels of wagons belonging to the cowboys. On Ahiga’s right, there was another outcropping rising a few thousand feet high.

Behind Ahiga, a fire raged. Six red Indians sat on their haunches and stared at the fire. Above it, a skinned pig was being cooked. On the right, there were many conical-shaped tepees. One Indian, the middle-aged Inola, poked the fire with a long stick. Strips of fire flared up.

The flap of the large tepee opened.

Wohali, the chief, in his feathered headgear, came out and strolled towards the group. He sat on his haunches and rubbed his palms together near the fire. It was getting cold as darkness settled on the horizon in this section of Texas. The year is 1790.

Ahiga also strode up and joined the group. They sat in silence as they experienced the stillness all around. Small, glittering stars appeared in the sky.

Onacona, a tribal elder, said, “The cowboys have set up their homes several kilometres from here. They have guns and revolvers. We only have bows and arrows and are vulnerable on this flat surface, Chief. We need to move.”

Wohali nodded.

“I understand,” he said. “We will move up to the mountains on the other side, but we will need to find a place where there is water. This was an ideal place.”

Indeed, right behind them was a clear stream, which had many pebbles and small rocks. You could see fish swimming at the bottom. There were large trees on the other side. The Indians got their fruits, honey, and figs from there. They lived on the edge of a vast expanse of mud and hills.

But the group had moved to this location only a few days ago. They had to do this, as the cowboys and their families seemed to move all over the place. It seemed to the Indians that the whites wanted to exterminate them. Instead of a peace dialogue, the cowboys let their bullets do the talking. The schism between the two communities was as wide as the Red Sea.

“I understand,” Onacona said in a respectful voice. “But if we stay here, we will all die.”

It was a stark warning. Wohali understood it. He knew Onacona would not say this unless the situation was dangerous. Onacona was an experienced warrior. He had seen many moons. He also had high intuition. The others remained silent and stared at the fire. The pig turned a deep brown. An aroma like roasted beef arose in the air. Ahiga’s nose twitched in anticipation of the meal. They were now sitting in darkness.

Wohali had always relied on Onacona’s experience.

He could feel the blood pounding in his ears. It seemed as if his body was telling him to move fast.

Wohali looked at the group, one by one.

They stared back. Everybody felt pressure within themselves. It had become a matter of life and death.

“Okay,” said Wohali. “We will move tomorrow, come what may.”

The others smiled and nodded. This meant they had all agreed with Onacona about the urgent need to move.

Inola took the pig down. Using a knife, he cut up the animal into small pieces. He placed them inside the leaves. The Indians took them back to their tepees to eat with boiled beans and corn. They told their family members about their impending dislocation.

Onacona’s wife Behita said, “We just arrived here. How many times will we have to move? This is a pleasant place, with plenty of water.”

“I know, but the white people are all over the place,” said Onacona in a patient tone. “Ahiga spotted a group some distance away. They might come this way.”

Behita pressed her lips together.

“How long can we run?” she asked.

It was a question that hung in the air inside their tepee and also in the other tepees. Indeed, how long could they run before the cowboys killed them?

Behita gazed at the animal rugs on the floor, the clothes hanging on a nail, and the hides nailed to the wall. ‘All will have to be loaded again,’ she thought. She blew out the small fire in the middle with a blast of air from her mouth. She lay down beside her husband on a mat on the ground opposite the entrance.

Outside, Ahiga kept guard with another young Red Indian, Dakota.

It was 1 a.m. They kept the fire burning by throwing in twigs and leaves. Dakota’s head nodded as he closed his eyes and drifted off to sleep. But Ahiga stood on one side, staring at the starry sky, as the cries of the cicadas interrupted the silence.

Two cowboys, Austin Smith and Brock Mathews, crept up behind Ahiga. The blue-eyed Austin stood up, placing his palm around Ahiga’s mouth, to prevent him from shouting. As Ahiga tried to turn, Austin slit his neck cleanly from the back, as the blood gurgled out in soft squirts, and laid him down.

Austin wiped the blood off his knife on Ahiga’s leather tunic. Dakota was now fast asleep. Brock pressed his palm against Dakota’s mouth while slicing his throat. Austin and Brock gestured with their hands.

Thirty other cowboys came up. They had tied their horses some distance away around a few tree trunks. The men walked the rest of the distance, coming in from the other side of the stream. They had known about this Red Indian camp. Brock had spotted the group from a distance when he went for a reconnaissance ride. He found the access to water most convenient. For their community, they needed this location.

A few of the cowboys lit sticks of tinder, using the fire that Ahiga had kept burning. They walked on tiptoes and stuck them to the tepees.

The tepees caught fire.

As the flames grew in intensity, the shouts of the Indian inmates rose in a crescendo, like a church choir practising the high notes.

Thick plumes of black smoke rose into the sky. There was an acrid smell.

As the Red Indians and their families came rushing out, the cowboys aimed their revolvers at them. There were yells and groans of agony as the bullets hit the defenceless targets. Blood spurted out. A woman was sobbing while holding a dead child in her arms. A Red Indian placed an arrow on his bow. But before he could draw the string, a bullet pierced his forehead with a cracking sound. None of them had expected this attack, including Onacona, who had a gift for predicting the future. But this time he failed.

People fell and landed spread-eagled on the ground. Some lay face down in the mud, arms extended. Others lay on their sides. Blood flowed from wounds on the head, face, chest, stomach, and legs. Some had open mouths, while others looked to be in deep slumber. There was the odour of blood, like that of iron. Out of sheer fear, a few men had soiled their pants.

As the tepees burned, it resembled an arc of fire framed against a dark horizon.

Soon, the cowboys had determined that all forty of them were dead. Thereafter, a group brought back the shovels they had kept in bags slung around their horses’ necks.

They moved a few feet away and dug into the ground. The men let out grunts and exhaled.

The minutes passed. A small mound of mud formed at the edges. Everybody inhaled the wet smell of the mud.

Once the pit was ready, one man held the hands and another the feet and they threw the bodies into the pit. For the children, one man could do the job, holding their legs with one hand. They flung them like dolls. The bodies lay piled up, one on top of the other. Finally, they threw in Ahiga and Dakota, both young men, in their prime.

The men stared at the pit. A few men wiped their faces with a kerchief. They knew it was a necessary deed. It was a matter of survival — kill or be killed. A few of them sat on their haunches, trying to get their breath back.

In the eerie silence, a coyote let out a bark followed by a howl. A couple of men noticed the hairs on their arms stood up.

The men began shovelling the mud back into the pit. Soon, they had covered the pit. The cowboys used the back of the shovels to tap down the mud and make it a smooth surface.

Meanwhile, the fire was dying out among the tepees.

It was an exhausted group that trudged towards the horses. They returned home and washed their faces, legs, and hands. But when they closed their eyes, they saw images of the destruction they had wrought.

The next day, they came again. The cowboys bent and poked the ashes with wooden sticks to look for valuables. Some found gold rings and necklaces.

Within a few days, the white settlers took over the land. They formed a circle with their wagons to ward off attacks in the future. In the daytime, the boys ran to the bank of the stream. They took off their shirts and jumped into the water, letting out squeals of delight. They were not aware that other children of their age were rotting in a nearby pit, killed by their fathers. Sometimes, the women took the clothes and scrubbed them by the side of the stream. They felt calm and peaceful beside the serene stream.

There was no sign anymore that there had indeed been a Red Indian camp anywhere.

The white conquest was complete.

Many Indian tribes suffered the same fate

Later, some historians described it as a genocide.

October 28, 2022

The pernicious effects of war

By Shevlin Sebastian

Leaders throughout history have always stressed the need for their countrymen to march to war, to defend the nation against the ‘enemy’, to uphold values and to preserve society. War is glorified and praised. Soldiers are honoured and cherished. But what is the experience of a soldier at war?

Here is a longish extract from ‘Goodbye Darkness’, American historian William Manchester’s memoir of the Pacific War in World War 11, where he describes his killing of a Japanese soldier:

‘My first shot had missed him, embedding itself in the straw wall, but the second caught him dead-on in the femoral artery.

‘A wave of blood gushed from the wound; then another boiled out, sheeting across his legs, pooling on the earthen floor. Mutely, he looked down at it. He dipped a hand in it and listlessly smeared his cheek red. His shoulders gave a little spasmodic jerk, as though someone had whacked him on the back; then he emitted a tremendous, raspy fart, slumped down, and died. I kept firing, wasting government property.

‘Almost immediately, a fly landed on his left eyeball. Another joined it. I don’t know how long I stood there staring. I knew from previous combat what lay ahead for the corpse. It would swell, then bloat, bursting out of the uniform. Then the face would turn from yellow to red, to purple, to green, to black.

‘A feeling of disgust and self-hatred clotted darkly in my throat, gagging me.

‘Then I began to tremble and next, to shake all over. I sobbed, in a voice, still grainy with fear: “I’m sorry.” Then I threw up all over myself. I recognised the half-digested C-ration beans dribbling down my front, smelled the vomit above the cordite. At the same time, I noticed another odour; I had urinated in my skivvies. I pondered fleetingly why our excretions become so loathsome the instant they leave the body.’

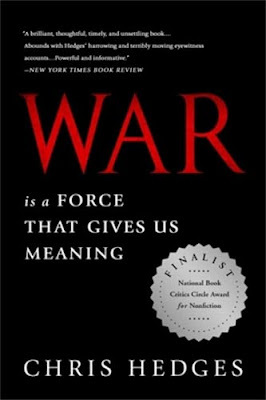

This extract has been reproduced in the book, ‘War is a force that gives us meaning’ by Chris Hedges, a foreign correspondent for 15 years with the New York Times. He covered conflicts in Central America, the Middle East, Africa and the Balkans.

His book can change your attitude toward war. It shows what really happens at ground level. Chris’s first-hand description of the war in Bosnia is unforgettable. The unbelievable cruelty and depravity that soldiers displayed was difficult to digest.

Here is a quote by Chris: “Once we sign on for war’s crusade, once we see ourselves on the side of the angels, once we embrace a theological or ideological belief system that defines itself as the embodiment of goodness and light, it is only a matter of how we will carry out murder.”

One thing that became clear from reading this book is how powerful are the forces of evil that live quietly within each one of us. And when these forces awaken, they thrust you into the heart of darkness.

The book, published in 2002, was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award for Non-Fiction. And is a must-read as the world heads for a possible nuclear apocalypse because of the Ukraine War.

Here are some quotes from the book:

Civil war, brutality, ideological intolerance, conspiracy and murderous repression are part of the human condition.

Soldiers who kill innocent people pay a tremendous, personal, emotional, and spiritual price.

The cost of killing is all the more bitter because of the deep disillusionment the war usually brings.

Killing unleashes within us dark undercurrents that see us desecrate and whip ourselves into greater orgies of destruction.

The ecstatic high of violence and the debilitating mental and physical destruction that comes with prolonged exposure to war’s addiction.

We dismantle our moral universe to serve the cause of war.

In the rise to power, we become smaller, power absorbs us, and once power is attained, we are often its pawns.

Killing is a sordid affair. Those who are killed die messy, disturbing deaths that often plague the killers. And the bodies of the newly slain retain a disquieting power.

The eyes of the dead are windows into a world we fear.

Modern war is directed against civilians.

Force easily snuffs out gentle people, the compassionate and the decent.

States at war silence their authentic and humane culture. By destroying authentic culture — that which allows us to question and examine ourselves and our society — the state erodes its moral fibre. A warped sense of reality replaces it.

Cliches, coined by the state, become the only acceptable vocabulary. Everyone knows what to say and how to respond. It is scripted. Vocabulary shrinks so that the tyranny of nationalistic rhetoric leaves people sputtering state-sanctioned slogans.

The nationalist myth often implodes with startling ferocity. It does so after the lies and absurdities become too hard to sustain. They collapse under their own weight.

Contradictions and the refusal to acknowledge the obvious become too much for a society to bear.

Nationalist cant always end up sounding absurd.

October 18, 2022

The magical world of books

Photos: The American Centre library in Calcutta; the National Library

By Shevlin Sebastian

The other day, I received a few cartoons regarding the foreignness of physical books for children on WhatsApp. In one, it showed a boy sitting at a table, with a book in front of him. His mother tells him, “Just open and read it. You don’t need a password.”

As I forwarded it to a family group, I realised I may be the only person in our family to read physical books and to go to libraries.

I began visiting libraries in my teens and fell in love with them. On hot summer days, on my weekly holidays, I headed to the American library, first on SN Banerjee Road and later on Chowringhee in Calcutta.

The air-conditioning was superb. The library was so spacious, with carpeted floors and large glass windows. This calm environment helped keep away the manic energy of the streets, the heat, the dust and the pollution for a while.

As for the books, what a treasure it was.

American publishers designed their hardcover books so well that one could only stare at them with wonder. And then to be allowed to take four books home on a library card. Wow, what a treat. It was, to quote a title of one of American literary great John Cheever’s books: ‘Oh what a paradise it seems’.

I was also an ardent fan of Pulitzer-Prize winner John Updike and would be awestruck at his productivity. Over 50 novels, short stories, art and literary reviews. His long-time publisher, Alfred A Knopf, produced some of the best designed books in world publishing. And still does. I may not be sure, but I think they used the Garamond typeface a lot. Which is a font that is pleasant to look at and soothing to read. Nowadays, whenever I write, I use Garamond at 14 points on Google Drive.

Apart from the books, there were the magazines. I read ‘The New Yorker’, ‘Esquire’, ‘The Atlantic’, ‘Ebony’, ‘Time’, ‘Newsweek’, ‘Vanity Fair’, ‘People’, ‘National Geographic’, ‘Sports Illustrated’, and ‘The New York Times Magazine’. There were so many more, but these come to mind only.

Some of the other libraries I visited included the British Council library on Shakespeare Sarani (another air-conditioned oasis), the Ramakrishna Mission library in Gol Park, and the National Library in Alipore.