Shevlin Sebastian's Blog, page 15

March 9, 2023

A childhood photo triggers thoughts

By Shevlin Sebastian

Photos: From left: Shevlin Sebastian, Sony Kurian and Tony Mathew; View Master; Alexander Solzhenitsyn

The other day, my uncle Siby Sebastian put up a photo of a trio of three boys in our family WhatsApp group. It’s not that clear.

That’s me on the left, along with my cousins, Sony (middle) and Tony. It was strange to look at this younger self. I do not know why I am smiling. When and where was this photo taken? Who was the photographer? Was it my dad or an uncle? What is Tony eating? Is it a biscuit?

During childhood, I was one of the shortest in class. In school, for several years, I was called Mini. It was another word for a pocket version. Very few classmates remember that nickname now. Thank God for that. This is a rare photo of me smiling. Most of the time, I have shown an unsmiling face to the camera.

In childhood, I was shy. No words came out of my mouth. That was why later, I got attracted to writing. I only had to interact with a typewriter and, later, computer and laptop screens to deal with words. It is also why I loved reading. Through the words, I could hear the voices of the authors. I did not have to meet and interact with them. That seemed enough for me.

Sometimes, people give a picture of yourself which differs from your inner image.

Last year, when my aunt came down from the USA, she told me, “When you were a child, you were afraid of your father.” My aunt and her husband stayed in Jamshedpur (284 kms from Kolkata). They would come on the weekends and spend time with us in Kolkata.

It surprised me when she said that. I didn’t think I was afraid. I felt intimidated by my father, who had a serious demeanour. He only mellowed in his later years. But this was what my aunt felt, looking at me from the outside. So, maybe she was right.

I remember when a couple came to our house in Kochi a few years ago. The woman said, “We had come to Calcutta when you were a child and stayed at your home,” she said. “Once when I was leaving the room, you told me, ‘You must always switch off the light and fan when you leave the room.’ I never forgot that.”

Yes, I could have said it. I do not know who ingrained this habit in me. Was it my father or mother? It is true even now, decades later, when I leave a room, I ensure I switch off the light and fan. I have tried to pass this habit to my family. But they are a lot more casual about it.

And here is what my Kochi-based cousin Joseph G. Vadakel wrote about meeting me in an essay he wrote for a family booklet:

‘It was my first encounter with our young cousin, Shevlin. He was five years old. I found him to be a quiet, pleasant, and well-mannered boy. I still remember the red and sleek-looking ‘View Master’ he had. It was a gift from his uncle in the USA. He generously allowed me to look through it. There were spectacular 3D colour images of the Niagara Falls, the Grand Canyon, the Pyramids, the Empire State Building, and the Hanging Gardens. It was beautiful.’

What we think of ourselves and what people think of us can be the opposite.

This is what my mentor George Abraham, former Deputy Resident Editor of the New Indian Express, wrote in a pamphlet he brought out on his 75th birthday, on February 22, 2023, for his extended family.

‘There are people who can make us feel good and there are those who can make us feel bad with their mere presence. Shevlin belongs to the first category. That is an ability so valuable in these days of growing uncertainties, unrest, distress, frustrations and loneliness. Shevlin made me feel important enough to be written about.’

I was taken aback when George Sir pointed this out. Nobody has told me this before.

So, is there anything about the child in the photo in the adult me?

For one, I enjoy being alone. In life, we have to play several roles: husband, father, son, sibling, cousin, professional, and a relative. It is nice not to do these roles once in a while.

What else? I have had a sweet tooth since childhood. That remains.

I have lost my temper on quite a few occasions. That has become much less, because age has mellowed me.

I remain slim, like my childhood, thanks to daily exercise and a careful diet.

Of course, the substantial change is mental. Nowadays, the inner journey interests me a lot. Who am I? What is my destiny? What happens after we die? Where are all the relatives who passed away?

Do I have any original thoughts? This question has preoccupied me a lot.

Is my thinking based on my childhood indoctrination by school, parents, religion and the society that I lived in?

Are there any original thoughts in me?

The answer to this seems to be: nothing we say is original. Everything is a mix of our brainwashing, the reading we have done, the mentors who have influenced us and our interactions with people. We repeat what we have learnt. That’s the case with most people.

The other aspect is the fear of inner darkness. Many people reject this concept of evil living in us. They don’t believe they have a dark side.

But this is what Nobel Prize-winning legendary writer Alexander Solzhenitsyn wrote in The Gulag Archipelago (1918-56): ‘If only it were all so simple! If only there were evil people somewhere committing evil deeds, and it was necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being. And who will destroy a piece of his own heart?’

Indeed, how true that is!

These were some of the thoughts that arose when I saw this childhood photo.

February 24, 2023

Visiting an aunt

Photos: Marykutty Aunty, at 82 years of age; Marykutty Aunty (sitting, second from left) with her husband Pappachen Uncle. The others in the photo include her children, a daughter-in-law, sons-in-law, and a few of her grandchildren and great grandchildren. The house of her in-laws. The couple is my parents on their wedding day, December 31, 1954. Photo from the collection of Siby Sebastian

By Shevlin SebastianI drove up the hill. The road climbed straight up for 25 metres, then it took a sharp turn to the left. Then, after another 50 metres, I arrived at the courtyard of my aunt’s bungalow in Mammood (100 km from Kochi) in Kerala.

On this Saturday morning, Marykutty Aunty was relaxing on the porch. In earlier times, my aunt would have been reading a newspaper. But now she was browsing through images posted in a WhatsApp group.

She invited my wife and me to the living room. For decades, I have visited this ten-room bungalow. It has outhouses, a well to one side, a garden with a gazebo and a large estate all around.

My earlier visit to the house was on September 8, 2022. It was the 90th birthday celebration of Marykutty Aunty’s husband, Kurian (Pappachen) Sebastian. Relatives, friends, priests and nuns had arrived to celebrate the occasion.

Pappachen Uncle was in an advanced stage of intestinal cancer, but it was painless. Because he was so old, the doctor did not prescribe chemotherapy. So, Pappachen Uncle looked lively. His memory was intact. He interacted with everybody. He cut a cake. Everybody clapped.

On October 28, Pappachen Uncle passed away.

A 66-year marriage ended.

As my aunt spoke about those last days, her eyes filled up. She took the end of her pallu and pressed it against her eyelids.

To lighten the mood, she offered something to eat. But we just had our breakfast. In the end, I opted for a banana.

She brought a bunch on a tray. The skin was dark green. It tasted like a robusta but was half its size. In local parlance, they called it a ‘kaali pazham’. Marykutty Aunty had plucked the bunch from a tree at the back. She had not used pesticides or manure. It was a rare occasion when I did not eat fruit treated with chemicals.

Out of the blue, I said, “Aunty, in your 82 years, which period was the best?”

Marykutty Aunty was silent for a few moments. Then she said, “The best part was when the children were young and in school.”

She has two daughters, Tessy and Maymol, and a son, Sony.

Her answer confirmed what I already believed. For most women, motherhood gives them the greatest pleasure. Not marriage, or love of spouse, or even a wonderful career. All these are worthwhile, but they did not match the joy, fulfilment, as well as the anxiety of being a mother. Once a mother, you remain one till your death. Of course, that is the case with the father, too.

In the early days, Pappachen Uncle left for work at the Life Insurance Corporation of India at 9.30 am. Soon after, the children went to school. At 11 a.m. Marykutty Aunty took a bus and travelled to her in-laws’ house, which was about two kilometres away.

Her father-in-law, PJ Sebastian (Achayan), was a noted politician and social worker. He had his office in the centre of the house. So, people would have to pass through the living room to enter it. Informal visitors walked by the side of the house, reached a courtyard, climbed the steps, and entered the office from the back.

There was always some discussion taking place. Achayan wrote a lot. In those days, there were no computers or laptops. People used fountain pens with Sulekha ink. “Achayan also read a lot,” my aunt said. Depending on what the visitors wanted, the lady cook, Maami Cheduthy, made tea or coffee, lime juice or buttermilk. Sometimes, a worker, Chacko, carried the glasses on a tray. Otherwise, Marykutty Aunty did it.

She would return by 3.30 pm so that she would be at home when the children returned from school.

I asked, “How was Achayan as a person?”

“Very calm, pleasant, and always had a smile on his face,” she said. “I don’t remember him ever losing his temper.”

I asked, “How was he as a father-in-law?”

She shook her head and said, “He never treated me as a daughter-in-law. I was always a daughter to him.”

Marykutty aunty’s mother-in-law, Thresiamma, stationed herself in a room, with an open door, near the kitchen. Sometimes, Amma sat on a chair or lay on a wooden bed. She would supervise the cook and instruct the workers. Sometimes, they plucked black pepper from the trees. On other days, they tilled the land to grow jackfruit, bananas or rice.

At dawn, workers collected the latex from the rubber trees. The milk fell in steady drops into cups. They made these cups out of coconut shells. In an outhouse, the family had put up a rolling machine. The workers converted the latex milk into rubber sheets by adding ammonia and acid. The family sold these in bundles based on weight.

Every morning, a man came to the house to milk the cows. There were several of them in the cowshed. They let out a moo now and then. Hens ran around the courtyard, clucking away and pecking at seeds.

It was the quintessential scene in a village of Kerala.

Asked about her in-laws’ relationship, Marykutty Aunty said, “Both Achayan and Amma had a loving relationship.”

At night, Achayan would place the petals of a fragrant flower on Amma’s side of the bed. ‘Nice,’ I thought.

Since Achayan passed away in 1972, Marykutty Aunty was referring to the 1950s and 1960s. Achayan and Amma had eight children: six boys and two girls. Out of them, four have passed away.

Marykutty Aunty lives alone. To provide company, a 70-year-old woman called Achamma comes every night. Her house is outside the estate.

Marykutty Aunty has a maid, Sonia. She stays in an outhouse. Sonia is from Midnapore in Bengal. Her husband, Ganesh, works in a house a couple of kilometres away. But he comes in the night and stays with Sonia.

Throughout her life, Marykutty Aunty remained a homemaker. In contrast, her children’s lives were different.

Tessy had a 41-year career in education. Following her retirement, she worked for another eight years as Professor of Economics at St. Joseph’s College of Engineering and Technology in Pala. “Daddy used to remind me that the sky was the limit,” said Tessy. “My mother always told me to be humble and God-fearing.”

Marykutty Aunty’s son, Sony, is an entrepreneur. Her daughter Maymol helps her husband, Raju Davis, to run a school of 1600 pupils. They live in different parts of Kerala.

Marykutty Aunty has eight grandchildren and seven great grandchildren. Everybody comes for visits. She visits and spends time with her children. At Christmas, Easter and Onam, there are family celebrations.

My aunt said, “The years have rolled by.”

She stared at the floor, looked up and said, “Life is short.”

February 5, 2023

'Blackmail' -- a short story

By Shevlin Sebastian

It is noon. Roop Parmar, in a bright red ghagra choli, sits in front of the TV, watching a Hindi serial on Star Plus. She is also cutting up onions on a wooden board placed on a low table in front of her. Occasionally, she wipes away tears, because of the onions, using a pink handkerchief.

Roop stays in a first-floor apartment in a grey building at a railway colony in Ranchi.

A postman, in his khaki uniform, enters the colony in his Honda Activa. He walks up the stairs and rings the bell. Roop heads to the door, the trinkets around her ankles making a ‘ching ching’ sound.

It is a registered parcel in the name of her husband, Amit Singh.

She signs it, as the postman looks her up and down, his mouth partly open. Roop is used to the male gaze. She does not flinch. Roop knows that at 32, she is in full sexual bloom. She also knows that her nose ring gives her face a sensual look.

Roop closes the door, and thinking that it is an official document, places it on the dining table.

She is alone at home. Her husband Amit works as the station master of Ranchi station. Roop’s two sons, Anup and Rakesh, who are studying in Class six and four, are at the Don Bosco School.

In the evening, when Amit arrives home, he sees the children are playing on the lawn in front of the building. He can see Roop sitting on the ground with the other women. On day shifts, this was the pattern. So, he strode up the stairs, headed to the kitchen, lit the gas stove, and made a cup of tea.

He took it to the dining table along with a plastic container that contained Marie biscuits. As he dipped the biscuits in the tea and ate them, he noticed the letter. His eyes widened in surprise, since Roop had not informed him by WhatsApp about it. ‘Maybe she forgot,’ he thought.

He tore open the large envelope and pulled out the contents. There were a few photos. He looked at them first. They contained black and white photos of him in bed with a woman called Anita Dusadh.

He stared at the images. In one, he could see his arched back as he lay over Anita. In another, he is sitting next to her on the bed, her breasts exposed, and they are kissing. He can see part of his tongue. One hand of his is clutching Anita’s breast. In the third photo, Anita is sitting over him, her back to the camera, her hair in a top knot. ‘Oh God,’ he thought. ‘Who got these shots?’

Amit realised it was only in one shot he could see his face as well as Anita’s.

She had been a passenger who arrived at Ranchi station at 9 pm. She had returned from Delhi where she attended an All-India meeting of employees of an advertising company. Holding the designation of Vice President (Client Servicing), Anita represented the Ranchi branch.

As stationmaster, Amit had been standing on the platform, watching the passengers disembark. Anita approached him and asked whether he would help her get an auto or a taxi.

He liked what he saw. A deep cleavage. This exposed the top of her breasts nicely. Kohl-rimmed eyes. The chiffon saree clung to her body. Black heels. ‘Nice figure,’ he thought. So, instead of asking a porter to do so, he helped her get a cab.

They exchanged numbers. Soon, they chatted on the phone. He was in no hurry. Neither was she. They met after two months. They sipped coffee at a restaurant and bit into pastry cakes. This time, she wore a maroon salwar kameez. Amit noticed she did not wear any ring. He also realised that despite her chocolate skin, she had white teeth.

Anita smiled often. ‘She seemed to be an optimistic person,’ Amit thought.

They came from different backgrounds. Amit was a Rajput who grew up in Jaipur, the son of an entrepreneur. His father dealt in floor tiles. It did well, but after several years, it failed. So, Amit opted for formal employment. He had an arranged marriage with Roop, who belonged to his community. Roop had only studied up to Class 12 before her parents gave her away in marriage.

Anita grew up in Ranchi, an only child. Her father, a government school teacher, passed away a few years ago.

After two months, Anita invited Amit home. The 32-year-old, who was the same age as Roop, lived with her aged mother. She had not married. After chatting a bit, she took him into her bedroom, locked the door, and they made love. It was as easy as that.

Amit realised Anita was proactive, liked to be on top, and knew how to ride hard.

When Anita was on top, Amit followed the advice given by Rajesh Kumar. A self-proclaimed Lothario, Rajesh said he had bedded over 100 women. Amit had met him through a mutual friend.

One day, Amit asked him, “So, what is the secret of your success?”

“Simple,” said Rajesh. “Most women like to be on top during sex. So you have to ensure you don’t come, so that they get proper satisfaction. My method is to think about something else when they are on top. It could be politics, a film scene or a drama. This enables me to remain erect for a long time. Try it.”

Amit tried it. To his astonishment, it worked. And it worked with Anita, too.

Amit enjoyed Anita’s sensuality and her free-spirited ways in bed. His wife was low key in bed and happy with the missionary position. Anita did not have any mental blocks like his wife and the other women he had bedded.

Amit caressed her dark skin. It felt smooth and supple to him. She liked his muscular body and fair skin. What a contrast they looked in bed. ‘Ebony and Ivory,’ he thought. This was a hit song by singers Paul McCartney and Stevie Wonder.

Both were happy after the encounter.

So, this blackmail came as a shock. Amit finished his tea, took the cup to the kitchen, and washed it under the tap. There seemed to be a lingering, oily smell in the kitchen. He placed the biscuit container back in the cupboard. Amit returned to the dining room.

He took the contents, placed them back inside the envelope, and put it in his official briefcase.

Amit turned to the window. He could now see his sons on the swings. Both boys were smiling. They were taller than most boys of their age, thanks to their genes. Amit was 5’ 11”, while Roop was 5’ 8”. His wife remained sitting on the grass. It was the other women who were using animated gestures and talking loudly while Roop listened silently. ‘My introvert wife,’ Amit thought.

He called Anita. She picked it up on the second ring.

“Where are you?” he said.

“In the office,” she said. “Why?”

“Did you send me a registered post?” he said.

“A registered post,” she repeated. “No. Why?”

“I got one,” he said. “I have to show it to you.”

“Okay,” she said.

“Can we meet tomorrow?” he said.

“Sure,” she said.

After he cut the phone, Amit reflected on the tone of Anita. He had a feeling she knew nothing about it. If she did not know, then who took the photos and how? Who sent it to him and why?

When they met the next evening, Amit showed her the photos, and the typed blackmail letter asking for Rs 3 lakh. Anita’s eyes became like saucers.

“I swear,” she said, placing the tip of her fingers at the base of her neck. “I know nothing about this. It’s frightening. How did they take a shot from inside my bedroom? How could it be done? Is there a hidden camera there? If yes, who put it there and when?”

“How did they get in?” Amit asked.

“Exactly,” said Anita.

“There is no way I am paying any blackmail,” said Amit. “It must be a digital image. So, we cannot destroy it. I mean, how can we trust that person to trash it? He or she will keep a copy.”

Anita nodded.

“Do you have any idea who this could be?” said Amit. “Could it be someone who knows you? Maybe he or she is angry with you. A former boyfriend?”

Anita stared into the distance.

Amit sipped his tea. He remained calm. From childhood, he had this calmness. He rarely lost his temper.

“There is only one former boyfriend, Akshar Patel, but I doubt it is him,” Anita said, looking at Amit once again.

She paused and said, “We met in Gossner College where we were both doing B.Com. Akshar was staying in a hostel. He was from Ahmedabad. It was a casual friendship. We met for snacks in the canteen and for the occasional movie. There were no physical relations.”

“Where is he?” asked Amit.

In the US. IT,” she said. “Boston, I think. Akshar is married. Two kids. Doing well.”

Amit knew he could remove Akshar from the list of suspects.

“Anybody else?” he said.

Anita stared inside the teacup. Then she puckered up her lips, and said, “I don’t think anybody is obsessed with me. Unless it is a secret obsession and the man has not stepped forward.”

“I am supposed to meet the man at 2 pm, at Tagore Hill, three days later,” said Amit. “I will be there, but without the money. What will he do then?”

“I don’t know, Amit,” said Anita.

“Seems like a pervert who is angry because we had sex. Could it be somebody who is obsessed with me? Or could it be anybody who has a problem with you?”

Amit shook his head as his mind began going back, trawling through memories and images. “No, I can’t recall anybody,” he said, as he made a steeple with his fingers. “We have to locate and neutralise him before he damages both of us.”

“How do we do that?” said Anita.

“I have a friend who is a senior police officer,” said Amit. “I will ask him to do an informal investigation. The blackmailer will have to get in touch with me to tell me the location to drop off the money. I am sure he has my number. Easy to get since I work in the railways.”

“Yes, he might have my number too,” said Anita. “All he has to do is call my office.”

Anita frowned as an idea struck her.

“Listen, can you ask your police contact to come to my house and look for the lens?” she said. “I don’t want to be watched when I change my clothes and go to sleep. Pervert!”

Amit nodded and said, “I’ll tell him.”

And then his eyes widened as he seemed to recollect something.

“Anita, these are black and white prints. So, he has got it developed in a studio. Somebody else must have seen these photos. We could be in danger of another blackmail threat.”

They both pondered over this revelation. Anita exhaled and said, “It might become a mess.”

“Yes, I know,” said Amit. “Some people have nothing else to do but poke their noses in other people’s lives.”

Anita reached out and placed a placating hand on Amit’s arm.

“Relax,” she said. “We will find a way out.”

Amit’s eyes widened again, as an idea struck him.

“Are there CCTV cameras in your building?” he asked.

“No, the residents’ association wanted to install them, but there are no funds at present,” said Anita.

Amit pressed his lips together.

He paid the bill by placing currency notes in a saucer. They got up and left the restaurant.

The next day, Amit headed towards a mall. But he did not leave the station in the normal way. He jumped a fence and exited through the opposite lane from the main platform. Amit took an autorickshaw and reached the mall. There, he met the police officer, Dilip Kumar, who was in plainclothes, in the food court.

Amit told him the details.

Dilip nodded, as he twirled one end of his handlebar moustache with his fingers.

“We will have to track all your calls,” Dilip said. “When the blackmailer calls, we will pinpoint his location.”

Then Amit spoke about the camera in Anita’s room.

Dilip said, “Ask her to download a ‘hidden camera detector’ app. It’s free in the Play Store. She can scan the walls. If there is a lens, a beep sound will come.”

Amit told Anita about this.

That evening, when she switched on the app, the beep sound came. It was halfway up the wall. She called Amit who told Dilip. He sent a tech-savvy officer to the house. And he used gloves to take out the lens. They could check it for fingerprints.

The officer used the app all over the house, including in the bathrooms. But there was no beep. Anita wondered how the man had installed the lens. How did he gain entry? It seemed impossible. Unless he knew how to pick the lock. But Anita and her mother lived in a multi-storey building. So, people always moved up and down the stairs, especially the servants. The housing society had discouraged them from using the lift.

That night, as Amit lay down on the bed, his head on the pillow, he stared at the ceiling. Roop changed into her nightie before switching off the light.

‘This casual interaction with Anita has become so complicated,’ he thought.

Amit wished he had not had that session with Anita.

If the images appeared on social media, the authorities might force him to resign. The government and the bureaucracy were conservative about sexual matters and scandals. If the railways sacked him, what job could he do?

He had had casual flings earlier. He attracted women because of his height and muscular body. But none of them had created any problems for him. Now this man: Who was he? What was his aim? Was it only money? Or was he trying to exact revenge?

Roop switched off the light.

Amit closed his eyes. Like she did every night, Roop put her arm across Amit’s chest and pressed herself against her husband’s body. After a while, she put her hand on his penis. That was her sign she wanted it.

Amit sighed, but he felt a session would relax his mind. So, he leaned sideways and kissed her on the mouth. One thing led to another.

Roop had a particular habit. After she spread her legs, and Amit entered her, she pressed her heels against his lower back. This became even more intense as her excitement grew. As Amit tried to increase the speed of his piston-like movements, he had to push harder to counter the pressure Roop put on his lower back.

Once, when they were watching TV during the day, following his night shift, he told her about this. Roop’s face turned crimson. She always felt embarrassed when the topic turned to sex. She said, “Okay, I will not do that.”

But nothing changed. She continued to do it. Amit realised it was an unconscious habit.

One thing he was grateful about Roop was that she never, ever, said no to sex. She was always eager. His friends had told him many times about how their wives would often say no. They would cite tiredness, the children or their periods. But not Roop. Even during her periods, she was willing. All she advised him was to wear a condom.

Another significant difference with Roop, as compared to other women, was that she did not need foreplay. Amit would start kissing her, and within moments, she was ready to take him inside. With most women, including Anita, it was a slow burn. He had to do a lot of foreplay before they got into the mood. But not Roop. She got hot instantly. ‘Faster than two-minute Maggie noodles,’ he thought, grinning to himself.

He received a call at 10.30 am, on the morning of the day he was supposed to meet the blackmailer.

It was a landline call as he saw the STD code for Ranchi: 0651.

Amit said, “Hello.”

“Is the money ready?” the caller asked, in a muffled voice. It was clear he had stuffed some cloth or cotton into the mouthpiece.

“Yes,” said Amit.

“Very well,” the voice said. “No informing the police.”

“Understood,” said Amit. “Instead of coming to Tagore Hill, take a room in the Raso hotel in your name and leave the packet on the bed by 5 pm. When you leave, don’t lock the door.”

The caller switched off.

The police identified the location.

It was from inside the railway station.

Within minutes, Dilip got the precise location of the call. It was a public phone facility. In effect, it was a single phone placed on a table near the entrance. A physically challenged man in his late twenties named Hari manned it.

“Do you have closed circuit cameras?” Dilip asked Amit on the phone.

“Yes, of course,” said Amit.

“Are you at the station?” said the police officer.

“Yes,” said Amit.

“Check it,” said Dilip.

Amit stepped into the room where the camera screens were located. There was a baffled look on the faces of the two staffers.

All the screens showed snowy images.

“What happened?” said Amit.

“Sir, the screen became blank,” said one man.

“Check and find out what happened,” shouted Amit. “Repair it soon.”

‘What cursed bad luck,’ he thought.

At 11.30 am, a policeman appeared next to Hari. He asked Hari whether he remembers any person making a call at 10.30 am.

“No Sir,” he said. “Several people have used the phone till now. I cannot remember.”

Hari’s lips quivered and his hands shook. The police frightened him. Feigning ignorance was the method he used whenever the police interrogated him. After a while, the police leave. Which is what happened to the policeman who had just come up. He walked away frustrated. He could not threaten Hari because of his physical problems. The young man had only one leg.

Amit realised he would have to shell out Rs 2500 to book a room at the Raso.

He took a briefcase stacked with newspapers and took it to the hotel. As instructed, he placed the bag on the bed. He did not lock the door.

Dilip informed one of his informers, Prasad, to watch the entrance for the next two days.

Amit waited.

And waited.

The hours passed. Soon, one day passed. There was no call.

Prasad informed Dilip that no single man had come in or left quickly. There were groups of men and families.

Amit immediately went back. The briefcase remained in the same position on the bed. It seemed nobody had entered the room. Not even a member of housekeeping. Amit checked out, paid the day’s rent, and returned home.

It puzzled Anita, Dilip and him.

What happened?

Two days. Three days. A week had passed. There was no call.

The trio concluded that something had happened to the blackmailer. He might have suffered an injury or died.

One day Dilip called Amit and told him that there were no fingerprints on the lens. It seemed the man had used gloves.

Soon, a month passed.

Again, there was no news.

The couple relaxed. They began their trysts at two-month intervals. But each time Amit planned to come home, Anita would use the app to see whether there were any hidden cameras.

Once, while they were relaxing in bed, Anita turned to Amit and said, “Do you think the man was from the railway?”

“Why do you say that?” asked Amit.

“The call came from the station. And the cameras turned blank,” said Anita.

Amit nodded his head in slow motion.

He pressed his lips together and said, “There is a possibility.”

“Anybody from your staff with whom you had a fight?” said Anita.

Amit narrowed his eyes and said, “I don’t think so.”

But a few days after he had got the registered letter, Amit’s deputy, Mukul Kumar, died of typhoid. A bachelor, the 30-year-old, had been an introvert. ‘Could it be him?’ Amit wondered. ‘Unlikely. Mukul was lying seriously ill in a government hospital in the days before he passed away.’

There was still no contact from the blackmailer.

Aware that tongues would wag if Amit came to Anita’s building too often, they arranged trysts in hotels outside the city of Ranchi. Here, they behaved like a married couple. Amit started lying to Roop about his travels, blaming his senior officers. But after each session, Amit had a long bath, using perfumed soap, and splashed perfume all over his body.

He maintained his sexual relations with Roop. So she was happy.

Another month went by.

One day, when Amit arrived at work, the authorities told him he had transferred to Dumka station. This was 286 kms from Ranchi. He enquired about the reasons for this sudden transfer. A colleague informed him that the superiors knew about his affair. They felt it was advisable to transfer him. They were not happy about his behaviour.

“How did they know?” he said.

“No idea,” his colleague said.

“A staff member might have taken a mobile shot.”

Amit realised he lived in an era of endless surveillance. People could capture your image on a mobile phone anytime and anywhere. Civic authorities had mounted cameras on street lamp posts on most of the roads. When you entered a hotel, there were cameras inside reception areas, elevators, restaurants and the corridors. Nothing remained hidden.

He felt a sour taste in his mouth, as if he had bitten into a piece of bitter gourd.

Amit did not want to disturb the studies of his sons. So, he decided that his family would remain in Ranchi. He vacated the flat for the next stationmaster. Then he moved his family to another flat outside the colony. On his weekly off, he came home. Sometimes, Anita and he spoke on the phone.

Once, Anita called Amit and said that her maid could spend one night to keep her mother company. She could come across. But Amit dissuaded her by saying that too many people were keeping tabs on him. He would have to remain under the radar for the next few months. Anita felt disappointed, but she understood his compulsions.

She was also surprised that people knew about their relationship. Anita realised that an affair with a married man would reach nowhere. ‘What was the point?’ she thought. But she could not deny the sexual satisfaction that she got out of her relationship with Amit.

She would have to decide. Should she stay in it for the sex or walk away, because she wanted something permanent? Anita was not sure whether she wanted anything long-lasting. She was at that stage of her life where she was loath to lose her freedom. Because she had an income, Anita could run her own show. Why should she enter a prison?

All her married friends complained of stress and unhappiness in their marriages. One told her, “‘Men are from Mars and Women are from Venus.’ It will never work. Man and woman are too different to understand each other.”

Much later, when Anita was browsing in a book store did she realise that ‘Men are from Mars’ was the title of a book about human relationships which had become a bestseller.

There was also a risk that people in her office might come to know about her affair. That could prove damaging. Unlike in America, where people did not care what you did in your personal life, as long as you delivered in office, in India it was the opposite. They were extremely curious about each other’s sexual lives. ‘Frustrated assholes,’ she thought.

Anita decided she would not hurry into a decision. ‘There is time,’ she thought. But Anita could not deny that whenever she thought of Amit, her heartbeat quickened. As she told a friend who asked her to describe Amit, “Delicious body. Good lover.”

But Anita did not forget the danger she was in regarding the bedroom images. She prayed often at the temple and begged the goddess that the photos never surfaced on social media. That would mark the end of her career. Anita would have to leave Ranchi in shame.

Most nights, Amit slept alone. He knew he would have to be an ascetic regarding sexual matters until all the talk about his affair died down. Amit realised that with each woman, he would have one or two sessions, nothing more. Otherwise, there was a possibility of somebody exposing the relationship. ‘Damned mobile phones, cameras and drones,’ he thought. ‘You can’t have an affair in peace.’

He was keen to go up the ladder, so that he could get a fatter pension when he retired.

On some days, when he reached his home, it would be on a weekday morning. The children would be in school. He noticed Roop was keener to have sex first before chatting with him.

‘Women,’ he thought. ‘They can send you into a tailspin.’

January 30, 2023

An evening in Lagos - a short story

Pic: Boko Haram soldiers

By Shevlin Sebastian

It is a pleasant evening. On the pavement, children are walking, holding their mother’s hands. A gentle breeze is blowing. Birds are chirping in the trees. There is a white wall on one side. A Toyota Corolla comes slowly from the opposite direction. Two bearded men are sitting in front. They are in their late twenties. The non-driver is smoking a cigarette. What the pedestrians do not know is they have a bomb in the back seat. The detonator is on the floor in front.

Behind the wall is the US Consulate in Lagos, Nairobi. The Stars and Stripes flag is proudly flying in front of the building.

These men belong to the Boko Haram Islamic militant organisation. They are going to stop the car in front of the gate, detonate the bomb, and kill as many security guards and visitors as possible. These men are planning to give up their lives. Of course, they will attempt to ram through the barricade and head as close to the building as possible.

Will it work?

They are not sure.

They want to do a high impact bomb blast. This will guarantee worldwide press coverage. They also wanted to embarrass the Nigerian Army, which has killed many of their members.

As the men watched a few mothers go with their children in the opposite direction, one of them thought, ‘This is your lucky day.’

Boko Haram had killed over three lakh children in various terrorist incidents.

Suddenly, there is a sound like a cracker bursting. The car stops. The men get out to check.

It is a flat tyre.

Now there is no question of ramming the barricade. Both did not know how to change the tyre. They are not car mechanics, but suicide bombers. One of them called their handler and informed him of the situation. The handler shouted, “You fool! Abort the mission. One of you can take the luggage and return to the base. The other can wait while we send a mechanic.”

Thus, nobody died.

Up in the heavens, God gives a small smile.

But He knows the evil forces will not give up. One day, a bomb will burst. But at least, it is not today.

There is peace in Lagos.

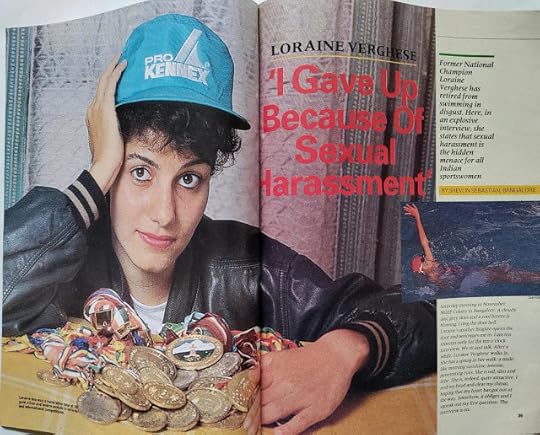

Swimmer Loraine Verghese accused coaches and swimming officials of sexual harassment. This was in 1992

By Shevlin Sebasian

Women wrestlers have recently levelled sexual harassment allegations against Brij Bhushan Sharan, the Wrestling Federation of India President. When I read the news, I felt a sense of déjà vu.

In December, 1992, I travelled from Kolkata to Bangalore. The plan was to do a profile of retiring champion swimmer Loraine Verghese for Sportsworld magazine

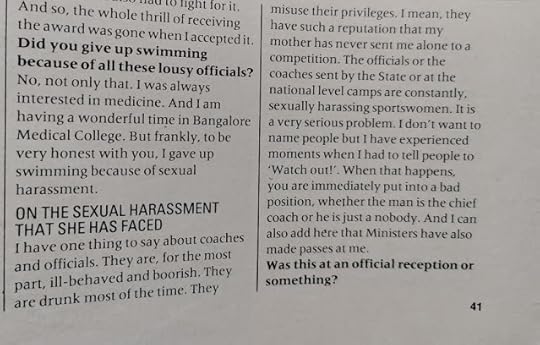

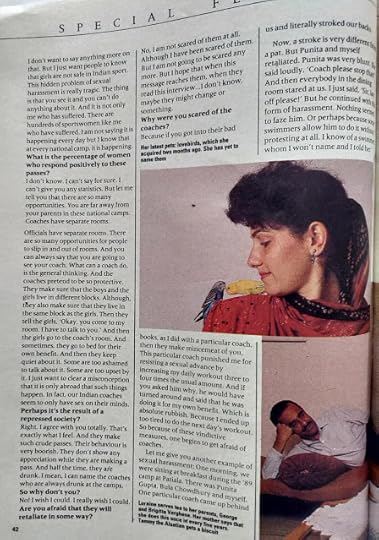

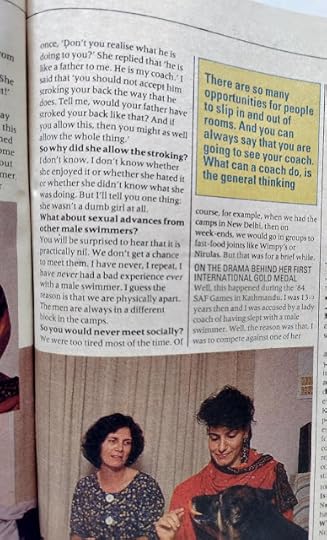

During the course of the interview, the conversation veered into a different direction. Loraine alleged that she and the other swimmers faced sexual harassment. The perpetrators: coaches and other officials.

It was the first time ever in India that a sportsperson was alleging sexual harassment. In a sense, unwittingly, I got one of the biggest scoops in Indian sports journalism.

Loraine decided to speak out, since her career was coming to an end. She wanted to study to become a doctor.

Since I tended to do long stories, I began recording my conversations from a very early stage of my career. Thus, this conversation with Loraine was also recorded. Picture of the cassette is also shown.

When the interview was published, it created a furore.

Politicians raised the issue in Parliament. They brandished copies of the magazine. There was talk of setting up an inquiry committee. But at that time, and even now, politicians ran all the sporting associations. So, the matter died down. They did not want to shoot themselves in the foot.

If you want to go to the subject directly, separate images of that section is there. Look for a sub-heading titled, ‘On the sexual harassment that she has faced’.

The article appeared in the issue dated December 16, 1992.

January 18, 2023

When time runs out (reflections on death)

Pics: Russian leader Joseph Stalin; Sri Yukteswar Giri (left) with Swami Paramahansa Yogananda; outer space

By Shevlin Sebastian

As you get older, it seems like every month there is news about somebody passing away. Almost all of them are relatives, many of them a generation or two above me. In earlier times, people attended funerals. But now that everybody is busy, you can come in before the burial, pay respects, offer condolences to the family and leave. A stream of relatives and friends arrive at the house as early as 6.30 a.m.

Usually, the person is placed in a mobile mortuary in the living room. Did the deceased ever imagine that he would be lying there? (for ease of writing, using one gender).

It was a room where he may have greeted many visitors. He may have exchanged small talk and fed them tea and snacks. Laughter might have erupted now and then. But now, he lay still and unmoving, in a horizontal position, his eyes closed. People came and stood near him in silence and stared at him

Later, they spoke to family members who recounted the last few days before the person passed away. People listened sympathetically. Many of them have had similar experiences: of their parents passing away, or elder siblings and relatives.

What thoughts go through people’s minds when they stare at a dead body?

Mostly, you recall the person when he was alive. The last time you met him. What type of person was he?

“There was always a smile on his face,” said one onlooker after glancing at a body and strolling away to talk to a friend. “That is so rare. People look so glum and tense these days.”

And these are common responses which one hears at many funerals:

“Oh, I met him a week ago. Who would have thought he would pass away so quickly?”

“Nobody told me he was gravely ill. The family did not inform anybody.”

“He looks ravaged.”

“Looks the same.”

“He has lost weight. Poor fellow.”

“Don’t mind me saying this. He was a bit of an asshole. A person who only cared about money. He sold his soul. Now what’s he going to do with all that cash? Take it with him?”

This last sentence was said with a smirk.

In my experience, very few dead people have any expression on their faces. It is rare to see someone with a smile. You always get the impression that they are looking at something that has transfixed them a couple of moments before they died. They are no longer aware of their family members or their life on earth.

When you looked at a dead body, it reminded you of your mortality. You say to yourself, ‘If I died at the age this person died, I only have 10, 15, or 25 years left.’

That can leave you depressed. Time is running out. The number of years has decreased. In middle age, I am now on the downward slope to oblivion.

Once when I was viewing a dead body, a thought arose in me.

How many breaths does a man take before he takes his last breath?

According to Google, if you live till 80, you will take 672,768,000 breaths.

A person may experience lakhs of thoughts in his lifetime. So, what was the last thought the person had before he died? Was it something random, like, ‘Today is such a hot day.’ or ‘I can’t bear this pain.’ Or was it an angry thought: ‘I hate myself.’

Russian leader Joseph Stalin passed away on March 5, 1953, at 74, following a stroke. His daughter Svetlana Alliluyeva wrote about the moments before his death:

“The death agony was horrible. He choked to death as we watched. At what seemed the very last moment, he opened his eyes and cast a glance over at everyone in the room. It was a terrible glance, insane or angry, and full of the fear of death.

“His suffering came because God grants a peaceful death only to the just.”

A transition to the other world can be difficult. Too many people suffer before they can pass. A director of a palliative care home told me that in 30 years, he had seen only five percent who passed away easily. The rest had to suffer. So when I hear news that somebody has passed away suddenly, I always say to myself, ‘God has been kind.’

And what happens on the other side?

The other day, I read an extract from ‘Autobiography of a Yogi’ by Swami Paramahansa Yogananda. In it, he talks about his just-deceased guru Sri Yukteswar Giri.

Sri Yukteswar appeared in flesh-and-blood form in a Mumbai hotel bedroom on the afternoon of June 19, 1936.

Sri Yukteshwar explained to his disciple about life on the other side.

“Prophets are sent on earth to help men work out their physical karma, so God has directed me to serve on an astral planet as a saviour.

“It is called ‘Hiranyaloka’ or Illumined Astral Planet. There, I am aiding advanced beings to rid themselves of astral karma and thus attain liberation from astral rebirths.”

So, what do you think of this? Some of you may be sceptical, but I like to keep an open mind. The more open it is, the more you can absorb messages from all sources.

Nobody can say with certainty what happens on the other side. All we can be sure of is that there is some sort of energy there. Bernard Harris, the first African-American to go into space, said, while on a visit to Kochi, “In space, everything is perfect. The planets, the solar system and the galaxies – all this did not happen by accident. There has to be some higher power which orchestrated all this. My faith in God deepened.”

Many of us will encounter this higher power only after we die. It is only the most revered saints and seers who get a glimpse of it while they are alive.

Perhaps, our one way of paying respect to this energy is to stay positive all the time. I feel that makes the energy happy. This may also increase our chances of dying with a smile on our face.

January 7, 2023

The life of a hit man -- a short story

By Shevlin Sebastian

It was a sleepy Sunday afternoon. The television sets in the various apartments nearby were silent. It seemed everybody was having an afternoon siesta.

A man stood at the door of a ground-floor apartment in Kolkata. He was wearing a T-shirt hanging outside his trousers. His name was Raju ‘Pehelwan’ Das. The door was closed, and he was in the bedroom. He took off his T-shirt and placed it on the clothes stand. He then changed into white shorts.

He has thick biceps and triceps. A smooth brown body. Entering the kitchen, he opened the fridge, took out Tropicana juice, and filled a glass with it. He sipped from it as he moved to the living room and switched on the TV. Aware that there was silence all around, he kept the volume on low and watched an English film on Netflix.

Pehelwan was a hit man for an underworld gang. He lived alone in Kolkata. His family lived in a village in Midnapore, 128 kms away. Every month, he sent money through Google Pay. Pehelwan has a wife, two sons and a daughter. They were all in college. Once a month, he took a train and headed back home.

The family lived comfortably. Nobody knew what he actually did. He has told the village that he was doing business. And he did not clarify what business it was. Because of his body, people were intimidated. They didn’t ask questions.

Since he was quiet and well behaved, nobody suspected anything.

In his job, he can be violent, slapping opposing gang members with ferocious slaps. He was a mean boxer and could trade jabs with the pick of them.

Pehelwan did not drink, smoke or take drugs. But like all men, he had one vice. He kept a mistress in a flat and made love often. He paid her bills and kept her happy. She was in her late twenties, a widow who did not have any children. At the moment, she was happy with the arrangement. Pehelwan has interacted with many women. So, he is not sure when she will insist on getting married and having a child with him.

He was sure he would ignore these suggestions. If she insisted he would get rid of her and get a new woman. He did not have any emotional attachment to this woman. She was a competent lover; he knew that, but there were many women who were capable lovers. Pehelwan wanted an uncomplicated relationship.

He understood her apprehensions. What if he got tired of her body and told her to go? What would she do then? He had several lovers before. Most were struggling and needed money. They used their bodies to pay household bills. But it was a fact that after a while, Pehelwan got tired.

He has explored every nook and cranny of a woman’s body and ravished her. There was nothing new to discover. A sense of staleness can creep in. And since Pehelwan had the money to get a new piece of flesh, he did. But to his credit, he gave enough money to the woman when he left her. They could survive for a year with no financial worries.

He was keen that they did not hurl curses at him. He was always scared of a woman’s anger and abuse.

Pehelwan knew that in his high-risk career, somebody could shoot him dead. There were enemies lurking everywhere. Which was why he had put fixed deposits in the name of his wife and children to the tune of a few lakhs in a few banks. If he died, they should not have any financial problems.

When Pehelwan was a teenager, he started lifting weights. Soon, he had a bulky body: a muscular chest, thick biceps and calves. It did not take long for the local people in his area to call him Pehelwan, the Hindi word for wrestler. He knew enough Hindi to know that was the wrong word, since he was a weightlifter. But the name stuck. And he liked it.

After he finished Class 12 in a Bengali-medium school, Pehelwan came to Kolkata in search of a job.

One evening, he was sitting in a street-side restaurant, having tea and samosas. A man observed him. He was none other than Malik Babu, who had established his gang in Kidderpore. Malik Babu was 20 years older than Pehelwan. He invited Pehelwan to join his gang by offering a monthly salary of Rs 10,000. That was difficult to resist.

Pehelwan began his career as a pickpocket and was very successful. Malik Babu allowed him to keep 20 percent of whatever he filched. Malik Babu told him that if he wanted to do well, he should be honest. He took it to heart and never cheated Malik Babu. Over the years, Malik Babu trusted him.

From the beginning, Pehalwan was careful with money. Instead of spending lavishly, as any young man would do, he opened a bank account. He began saving money every month. After a year, he had a tidy sum. After five years, he bought some land in Midnapore and built a small house. This was so that his parents could live in a house of their own, instead of being at the mercy of landlords.

As the gang did well, Pehelwan moved from being a pickpocket to being an enforcer. At some point, when he was in his mid-twenties, Malik Babu sent him to a shooting school. He learned how to use pistols and revolvers. Only in extreme cases would Malik Babu ask him to kill somebody.

It was only the first time that his body trembled as he took the shot. He saw the bullet enter his skull from the back and saw a streak of blood come out.

This happened on the outskirts of Calcutta. Pehalwan had followed the man who was heading towards Digha. When he stopped his car at a petrol station and walked to the toilet, Pehalwan followed. He shot him as he was urinating. Since he had a silencer, there was a low ‘phut phut’ sound. The man slumped against the wall and slid to the ground.

He was in his late fifties.

He was a building construction magnate. He had borrowed money from Malik Babu, but his business went bust and he could not repay. There was no alternative but to kill him. The aim was to send a message to the other business people they were dealing with. Pay up or else… It was the standard Mafia message, which criminal gangs used all over the world.

A message soaked in blood.

That night, Pehelwan had a difficult time sleeping. Images of blood spurting out kept recurring. He twisted and turned from side to side. Since he was a teetotaler, he couldn’t drink alcohol.

Instead, he lifted weights.

After several months, his mind calmed down, and he finally had a peaceful sleep.

He was glad that Malik Babu did not make too many calls to kill anybody. The gang leader used it as a last resort. Pehelwan knew Malik Babu was smart. A murder drew the ire of the police, the media and society. They would feel a sudden heat. Malik Babu had to pay a lot of money to the cops so that the spotlight moved away and the case remained unresolved.

‘Thank God for corrupt cops,’ thought Pehelwan. ‘Without them, our gang would have been busted a long time ago.’

In the past twenty years, Pehelwan had killed six more people. He knew nothing about their families. Pehelwan did not know how they survived following the death of the breadwinner. He hoped the wives would step forward and assume responsibility for the business. And he hoped they did not curse the unknown killer.

All the cases were unsolved.

Pehelwan kept a low profile all the time. He was a loner. So far, he has not appeared on any police record. He reported to Malik Babu. The Don gave him assignments. He did it efficiently. Sometimes, he wore a mask, especially because there were so many cameras everywhere. And he continued to save money and invest in land in remote areas of Midnapore, where it was cheaper.

He was sure that, after 20 years, these remote areas would become part of the town because of the burgeoning population. Then he could sell the land at an exorbitant price. His son and daughter were in Plus Two. Soon, they would graduate and get jobs of their own.

Everything was working fine. He prayed that there would no longer be any more murders. He was preparing to tell Malik Babu to get a younger hitman. At 48, the stress was too much to bear. And he feared a reaction. Like most people, he believed in the law of karma.

Pehelwan switched off the TV and lay down for a nap.

In the evening, he got up and walked to the kitchen. He made a cup of tea. As he sipped his tea and dipped Parle G biscuits in it, at the dining table, the front doorbell rang. He frowned. None of his gang members visited the house. He was not expecting any visitors, except Ganesh, a distant relative, who wanted to borrow some money. Pehelwan put on his T-shirt and walked to the door.

Two young men stood there. He did not recognise them. He had never seen them before.

His sixth sense said danger.

One of them took out a revolver. With swift reflexes, Pehelwan tried to shut the door and dived to one side. But he heard shots ring out, with the familiar ‘phut phut’ sound of the silencer. He felt something touch his lower back. And then he lost consciousness.

It was Ganesh who found him, with a pool of blood next to him, on the floor. There was the strange odour of rusted iron. Ganesh called for an ambulance and took him to a government hospital.

Two weeks later, Pehelwan received the prognosis. The doctors told him he was paralysed from the waist down. The bullet hit his spinal cord in the lower half. Pehelwan could not feel any sensation in his legs. He knew that his career in Malik Babu’s gang was over.

Overnight, he had become a useless member.

One week later, Malik Babu came for a visit. He had the look of a man who had come to view a dead body.

“You were my best man,” he told Pehelwan.

Of course, Pehelwan was smart enough to realise that Malik Babu had used the past tense. Pehelwan stared at Malik Babu, with his handlebar moustache and his jutting out eyes. He looked freakish, but Pehelwan respected the man’s intelligence. Malik Babu had always resorted to violence and murder as a last resort. He preferred psychological methods to intimidate people. That was one reason he lasted so long.

But Pehelwan had to accept the grim news that he would have to go back home. He thanked God that he had saved so much over the years.

Malik Babu said, “We still do not know who planned the hit. Or was it a warning? I am not sure if it was a gangland hit. It seemed to be somebody from outside, but who? There are no leads so far. Nobody informed the police. Thank God for that, because nobody knew.”

Pehelwan nodded. He was sure Malik Babu would solve the mystery. But it would take time. Pehelwan was no longer interested in revenge. Whatever happened, it would not restore his ability to move. He didn’t care, since he no longer belonged to the gang.

He wondered what he would do now. How was he going to live the rest of his life? What work could he do? He realised the roles would be reversed for his wife, Deepa. In the past, she always stayed at home. Now, he would have to stay at home while she went out for work, so that they could pay their bills.

He wondered whether he could be active. Would he be able to get an erection? He was not sure. One night, at the hospital, he held his penis, and it seemed to become stiff. ‘Maybe’, he thought, ‘it can be done if Deepa gets on top of me.’

He did not worry about his children. They were smart. He was sure they would graduate and get well-paying jobs.

The day before the hospital discharged him, Malik Babu gave him a packet covered in brown paper. Deepa had been present. She placed it under his clothes in a bag next to the bed. This was the first time Deepa had met Malik Babu.

Pehelwan said, “Malik Babu lives near my house.”

When he returned home two days later, he checked the brown packet.

It contained Rs 10 lakh in cash.

It was a parting gift from Malik Babu.

It was a generous amount.

Pehelwan was grateful.

And so his new life began. He sat in a wheelchair and stared out of the windows. He read newspapers, watched TV, and lifted weights for his upper body. Every morning, he watched his wife getting ready to go to work. She worked as a secretary in a small trading firm. His parents lived with them. His mother provided his meals.

He learned how to invest in the stock market on his laptop and earned money.

So life carried on.

He knew that by the time he died, he would clean up all the negative karma he had gained by killing seven people.

He also hoped to achieve a peaceful death.

January 2, 2023

A Naga short story

By Shevlin Sebastian

There is a wall, about 20 feet in height, and painted in white. In certain sections, you can see bougainvillaea creepers.

Despite the height, the wall has a benign feeling to it. But things are not so pleasant when you look at the top. There is barbed wire all along the perimeter.

On the other side, the authorities had not painted it. There is moss growing in certain sections. The constant rain had chipped away at the grey paint. You can see the concrete bricks.

There is a large, open area. This is a place where several convicts walk up and down in the evenings. In certain areas, they marked lines on the ground with white chalk. There is a net strung across two poles. It is a volleyball court. In another area, they have put up goalposts. Sometimes, the convicts play games if the weather is pleasant.

This is a jail in Nagaland. Most men are serving life terms. The courts had convicted them of murder, arms and drugs smuggling and for using weapons against the state. Many of them have narrow eyes reflecting their Mongolian ancestry.

Sometimes there are fisticuffs. Then guards have to break up the fights. They put the men involved in isolation blocks for weeks at a time.

Two Naga men, Asangla and Dadi, are close friends. Each is undergoing a jail term of 25 years. The Indian Army and rebel forces engaged in a gun battle in a jungle. In the ensuing mayhem, the soldiers captured them. They wanted freedom for Nagaland, so that it could become an independent nation. In short, they wanted to secede from India.

They have already served for 15 years. While Asangla is 52, Dadi is 46. In the evenings, they sit next to each other, out in the open.

Sometimes, they wonder whether it had been foolish to think they could secure independence from the Indian union. It had a powerful army. What they did was give pinpricks, at significant personal cost. But their leaders had indoctrinated them about the need to get freedom. They were too young to understand what a gigantic task it would be. And how much they would have to sacrifice to achieve their goals.

Most of the Naga leaders have spent decades in jail. The life they led hollowed them out and shattered the equilibrium of their families. The rest of Naga society carried on. Not everybody was grateful for their contributions because they achieved nothing.

They were on the losing side.

Who cares about losers?

But this is the dilemma for freedom fighters. When they try peaceful methods, nothing happens. But when they use violence and then lose, they face wrecked lives and the crushing of their hopes and dreams. What is the way forward? Could they take part in the election process? But what if the government bans them? In many countries, there is no democracy. At least in this Nagaland jail, the police had beaten the duo, but had not tortured them. But in countries like Iran, China, Russia and Belarus, the state had tortured and even killed political activists.

But when Asangla and Dadi talk to each other, they have no option but to feel regret.

Asangla’s wife Lily is a teacher in a private school. The childless Dadi’s wife, Narola, works as a secretary in an office. For Asangla, it was painful to see the children growing up without his physical presence.

Asangla could not take his children to school. He could not celebrate their birthdays and teach them discipline. He missed out on earning a living and building assets for the family. Both he and Dadi had missed out on sex with their wives during the peak years of their masculinity.

Asangla’s son, Mhalo, now 20, had fallen into the wrong company, dropped out of school and was doing drugs. His wife complained about it to Asangla. When Mhalo came for a visit, Asangla begged him to change his ways. He wanted him to make new friends and to divert his attention by playing football or badminton. But his son seemed unmoved. For Mhalo, it was like listening to advice from a stranger. He had tied his hair into a ponytail, using a rubber band, and wore a steel bracelet.

Asangla feared for the boy’s future. He knew that from drugs to crime is not an enormous distance. His daughter, Rita, 18, was already staying with a musician in a live-in relationship. She wore short skirts and high heels all the time. At least, she stayed away from drugs and studied till Class 12 and now works as a secretary in an office.

Asangla knew the future of his children, like his own, was dark and unclear. Lily came every week and brought along some soaps and toothbrushes. They could not bring food items. She spoke; he listened. She had more news than him. He led the same regimented life from morning till night.

Asangla stared at her. More and more, she was becoming a stranger to him. And he was becoming a stranger to himself, too.

He no longer understood his motivations, dreams, or desires. He was rolling from one day to the other, his mind blank.

Asangla wondered whether Lily was faithful. And yet, he could not blame her if she sought sexual gratification outside of their marriage. Why shouldn’t she? He had opted to be a militant, so why should she lose out?

Anyway, Asangla never asked Lily these questions because he knew it was futile. There was no way she would tell him the truth.

What stunned them was how Naga society had forgotten them. Life went on. Nobody spoke about freedom and independence. They were in the thrall of the mobile phone and the consumer lifestyle. It was engulfing their society.

The duo felt they had no option but to bite their lips, maintain proper behaviour and hope to get out. In that way, they wanted to salvage the remaining years of their lives.

As for Dadi, he was childless. Narola always came dressed in colourful tops and tight jeans and high heels. As a secretary for an international NGO, she earned well. She spent most of her money on clothes, lipstick, perfume and other items. Dadi knew Narola was enjoying life. She has been to concerts and parties.

Sometimes, it was with her female friends and sometimes with a male companion. Who the man was, Dadi did not know. And he did not want to know. She could have divorced him any day, but so far, she had not. Dadi was not sure whether she would remain with him. He wondered whether she loved him, or whether she was too lazy to get a divorce. Maybe she had not found a man whom she wanted to marry.

They met when they were teenagers. They lived on the same road. It led to a romance and later, marriage. Both were in their early twenties when they got married. But Narola did not have any children. Dadi was not sure whether it was his problem or hers. Within three years of his marriage, he had joined a militant group.

His life changed. Dadi lived an underground existence. His parents passed away when they were only in their fifties. His only brother worked in Delhi in an IT firm. He married a Naga girl and had children.

Dadi was happy for him.

His brother had always been practical and smart. Now he was enjoying life, while he rotted behind bars, keeping company with tough people. All with massive egos. Nobody felt any sense of repentance. For many of them, murder was something they yawned at.

Dadi only felt comfortable in the company of Asangla because they had been comrades in the battles against the Indian Army. Once his wife Narola asked him whether he had taken the right path.

He said, “I thought I was on the right path. Nobody can live a perfect life and always make the right decisions. Sometimes, we make mistakes.”

She nodded, partly in appreciation because Dadi admitted he had made a mistake. She felt there was no point in ramming home the point about his errors. Dadi was paying for it every single day.

In December, 2021, a unit of the 21st Para Special Forces of the Indian Army had killed six civilians near the village of Oting in the Mon District of Nagaland, India. In the subsequent violence, eight civilians and a soldier lost their lives.

Some of their old anger and fire reared in the duo when they heard the news.

“We can never trust these Indians,” Dadi said.

Asangla told him to keep quiet.

“Our aim is to get out because of good behaviour,” he said. “So, let’s maintain our composure.”

Of course, the others railed against the Indian state. But Asangla was tired of it. He wanted to move on. At 52, he did not have the energy to change anything. All he did was worry about his children. He prayed every day that God would protect his children.

But, at night, like Dadi, he had a disturbed sleep. Images of him shooting Indian soldiers appeared in his mind. Blood was oozing out of their skulls. He had killed three of them. He wondered whether they were married and had children. Every day, their families must be cursing the killers. This was also the case with the families of the Nagas, whose males the Indian soldiers had shot dead. They must be cursing the soldiers for their trigger-happy fingers.

And this cycle of anger, hatred and violence has carried on for decades.

Who knows, it might go on for centuries.

December 29, 2022

A penetrating look

By Shevlin Sebastian

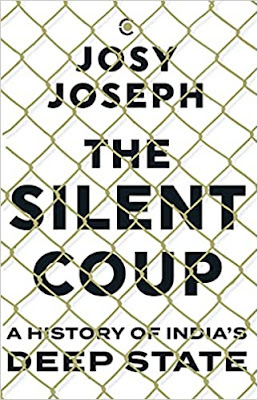

‘The Silent Coup: A History of India's Deep State’ is one of the most chilling books I have read in recent times.

Josy Joseph, an award-winning reporter, highlights the callous behaviour of law enforcement.

If, by bad luck or coincidence, you fall into their clutches, you could end up dead. If you survive, you will become a mere husk of a human being, physically broken and mentally shattered. It will destroy your family. The family will take decades to feel a sense of normalcy. They feel a deep sense of injustice when the authorities do not reprimand the police for false cases. There is not even a slap on the wrist. They continue to flourish under political patronage. The law of karma never works in their case. Their life moves along splendidly, with plum postings and perks.

Josy said Parliament must enact laws that will make law enforcement accountable to it.

When a major terrorist attack takes place, the investigation is shoddy. Those whom the police arrest are informers. The informers get shocked because for so long, they have worked with the police. The police feed the media a false narrative. The actual perpetrators escape justice.

Most times, the police delay filing the charge sheet. The case moves at a snail’s pace through the legal system. Courts can take anywhere from ten to fifteen years to exonerate them.

How do you pick up the pieces of your life after that?

Some of the topics Josy has dealt with include the militancy in Kashmir, bomb blasts in Mumbai, the 26/11 Pakistan terrorist attack, the insurgencies in the North-East and the Sri Lankan imbroglio. He also focuses on the other conflicts that have beset the nation in the past 75 years.

Josy highlights the anti-Muslim bias among police officers.

The lack of Muslims in law enforcement heightens the prejudice. According to Josy, the political executive has completely seized control of the agencies. They have no independence. Hence, their investigations lack credibility and integrity.

This book is a must-read for any Indian who is worried about the future of the country.

We need multiple and honest viewpoints to have a better understanding of our complex country.

Only the truth can save a society from ruin.

December 26, 2022

All about a crow

By Shevlin Sebastian

I am standing outside a tailor’s shop. As he deals with another client, I notice a crow standing less than a foot from me. We exchange looks. Something seems to reassure it. The crow does not fly away.

It is pecking at a brown powder, which somebody had spilled. It seems to be wheat. A scooter whizzes past, within inches of the crow. It flies up a couple of feet in shock. Then again, it returns. A car and a bike pass. The crow keeps a wary eye as it keeps pecking away.

I realise it is hungry, and willing to take the risk of being hit by a vehicle. I wonder how old it is. It looks healthy. It has a firm beak, strong claws, and smooth feathers. In the crow world, does it have a name? How do they identify each other? Is it married? Does it have baby crows? Where does the crow stay? In a tree nearby or somewhere far away?

Does it have parents? Do they all stay together? Or are they all scattered? Do the crows have moods? On some days, it feels as light as the clouds it passes through. Other days, does its head droop and the crow sheds tears?

When that happens, does a female crow offer solace? How do they do that? Is it through touching or cawing? Are there days when the crow goes hungry? As we throw food waste away inside packets, birds and animals like dogs and cats cannot access it. Is filling the stomach the primary purpose of every day?

What about elderly crows? How do they feed themselves? Can they fly until the end of their days? Do they suffer from weary bones and wings, hypertension and stress?

Do younger crows look after the older ones? Or are they abandoned? When crows fight, do they have a court where justice is dispensed? Or is it a pecking match and the strongest crow wins?

What do crows think about humans? Do they hate them? Or fear them? Do they feel we humans have perpetrated a grave injustice against them and all other birds, with our destruction of their natural habitat?

Do crows believe in God? Or the afterlife? Do they have goals and desires? Are there any sporting competitions between the crows? Like a World Cup or Olympic Games? Do crows get divorced and find a new mate?

How do they gain new knowledge? Is it only learned from experience? What happens when they suffer a broken wing? Do they have doctors to repair it? Or are they condemned to live with a broken wing until the end of their lives? Do they have an inferiority complex because their cawing always sounds like a death rattle?

What is the attitude of other birds, like sparrows, cuckoos and parrots towards crows? Do they like them? Or prefer to stay away? Is there a caste system among birds? If so, where are the crows located? Are they at the bottom because they are black?

How long do crows stay in a particular tree before they leave for new pastures? Do they find the monsoon too difficult to bear? What about when the climate is too cold? How do they bear it? Do they use leaves as blankets? Or do they shiver through the long and lonely nights?

Do they have philosophical discussions with each other? Why am I here? What is the meaning of life? What will happen after we die?

What kind of brain does a crow have? Does it have a conscious and unconscious mind? Do crows dream at night? Do they have sexual fantasies?

Do crows have a language they use? Do the older crows tell the younger crows the stories of past eras, and the history of the cows over several generations?

Do crows believe in God? Is it one God, or several gods and goddesses?

Are there criminal crows? Is there a Mafia among the crows? Perhaps, like human land grabbers, could there be crow tree-grabbers? Are there law enforcement officers among the crows?

Is there an all-India meeting for crows? What is the common language they use? Do they talk about the loss of habitat? About the endless greed of man, which is destroying nature? Do they think people are staring too much at screens and losing their connection with Nature?

The tailor interrupts my thoughts and says, “Sir, please come in.”

I show him the torn pocket. He nods and says, “Come tomorrow.”

As I step out, I completely forget about the crow and walk home. Had the crow flown away? No idea. I was back to living inside my mind. I am there 24 hours a day, 365 days a year.

I hope that one day, aeons later, human beings, animals and birds will develop a common language, so that we could all communicate with each other.