Shevlin Sebastian's Blog, page 2

September 29, 2025

A Free Bird called Simon Barnes

COLUMN: Tunnel of Time

By Shevlin Sebastian

Simon Barnes of The Times, London dropped into the Sportsworld office in Calcutta the other day. A thin, intense man, he had flowing shoulder-length blond hair interspersed with a few strands of white hair. He wore a straw hat and big leather boots; it gave him the quintessential image of the foreign traveller. An English version of Indiana Jones.

Simon Barnes is a columnist who dabbles very successfully in anything that comes his way. His style is simple and smooth, like the surface of a laid-back river. He is an itinerant wanderer.

He has travelled over the world, covering major events like the Olympic Games in Seoul, the Wimbledon championships in Britain, the Super Bowl in America and the Nehru Cup in India. He has interviewed people ranging from racing hero Ayrton Senna to sprinter Ben Johnson and boxing god Mike Tyson.

‘A champion in any sport,’ he says, ‘is always an interesting person.’ But perhaps the most endearing quality of Simon Barnes is his affinity and affection for all things Indian. He says that India is a magnificent, strange and quixotic land. He plans to come back again and again.

‘It was a tremendous experience when I experienced Asia for the first time,’ he says. ‘It changed my life.’

His fascination with the continent resulted in him staying four years in Asia based in Hong Kong. He did freelance work and for payment, he asked for air tickets to new places. The result was that he has explored Malaysia, the Philippines, South Korea, Singapore, Sri Lanka, India — you name it, he’s been there.

‘It’s a fascinating experience,’ he said, ‘walking through the forests of Malaysia, lying on the beach in Sri Lanka and getting lost in the by-lanes of India.’

At lunch, while sipping a beer, he said, ‘I love to travel. I hate to be bound up in one place. I want to explore the world. And that is why I am a freelancer for The Times. It helps me to move around.’

The talk then turned to the irritated anger of British journalists while on tour in India. It was the turn of colleague Mudar Patherya to vent forth his much-justified anger against the British scribes.

But Simon was sympathetic and quite perceptive. ‘Remember one thing,’ he said. ‘In India, things take a long time to work. It takes almost a day to get a call to London. Remember that English journalists are living in two time frames. One half of his mind is in India while the other half is in London. He is under pressure from his bosses in London to meet deadlines.’

Agreed, but Mudar didn’t let up. He said, ‘Yes, but here in India, the foreign press expect to get top-class treatment but when we go to their country, they treat us so poorly.’

The onslaught was furious and relentless and Barnes did not know what to say. It was also getting a little embarrassing, and with clever British tact, he changed the subject.

‘Let me tell you a story,’ he began. ‘This has got to do with Graham Morris, the photographer. There was a cricket match among the scribes and Graham Morris realised, as he was padding up to bat, that his partner was a certain Mr. Gavaskar. As he walked out to open the batting with the Little Master, Gavaskar turned to him and said, “See Graham, India is a vast country with different cultures and different languages. So when we go out to bat, we decide beforehand in which language to speak when we call for a run.” Gavaskar then paused and said, “I presume you would like to use the English language.”’

Graham Morris was silent for a moment, then he looked up and said, ‘Accha.’

The conversation rolled on, to apartheid in Africa, the present political situation in India, the supple style of R.K. Narayan, but soon it was time for him to leave.

And the most enduring impression that one got of Simon Barnes was his love of freedom. Freedom to be himself, freedom to move around and see new worlds.

There is a familiar saying that goes like this: ‘Man is born free but is everywhere in chains.’ In Simon Barnes’ case, it was clear that the first thing he did after he was born was to take a hacksaw and break the chains around him.

He’s been a free bird ever since.

(Published in Sportsworld, November 15, 1989)

Update on Simon (according to Wikipedia): Simon, 74, was chief sports writer The Times, and wrote a wildlife opinion column in the Saturday edition of the same newspaper. He has written three novels.

In June 2014 Barnes was sacked by The Times after 32 years' employment, the newspaper having informed him it could no longer afford to pay his salary.

Speculation in some sections of the UK media was that the real reason may have been Barnes's outspoken views expressed in his wildlife opinion column.

The column blamed illegal activity by red grouse shooting interests for the continued persecution and near extinction of the hen harrier in England.

Writing on his blog, which he began after leaving The Times in 2014, Barnes wrote: ‘Certainly I have annoyed some powerful people.’

September 23, 2025

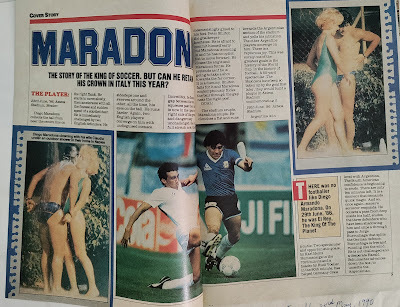

The King of the Planet

COLUMN: Tunnel of Time

The life story of Diego Maradona, one of the greatest footballers in world history

By Shevlin Sebastian

THE PLAYER

June 23, 1986, Azteca Stadium, Mexico

Diego Maradona collects the ball from near the centre line on the right flank. He starts to move slowly, then accelerates with all the finesse and sudden speed of a startled deer. He is immediately challenged by two English defenders. He sidesteps one and swerves around the other. At all times, his eyes are on the ball. He runs harder. Again, two English players converge on him with undisguised menace.

Incredibly, he squeezes past them both between the right side of the field and the touchline. Now in full stretch, the ball mesmerisingly glued to his feet. Peter Shilton, the goalkeeper, hesitates. He is afraid to commit himself early, but Maradona is coming in and he has no option but to move forward.

He closes the angle and Maradona feints. He pretends as if he is going to take a shot towards the far corner. It is a dummy. Shilton falls for it, and Maradona contemptuously flicks the ball through the near right post.

GOAL!

The stadium erupts; Maradona erupts. He clenches a fist and runs towards the Argentinian section of the stadium and yells in jubilation. The other Argentine players converge on him. There is a rapturous joy. This was surely one of the greatest goals in the history of the World Cup. In the history of football. A 55-yard spectacular.

The Mexicans have been so taken up by the goal that later, they would build a plaque in the Azteca Stadium commemorating it.

June 29, 1986. Azteca Stadium.

Argentina is in trouble. Two spectacular and opportunistic goals by Karl-Heinz Rummenigge and a header by Rudi Völler have helped Germany draw level with Argentina in the final of the World Cup.

The South American confidence is beginning to erode. There are ten minutes left. It is a moment that demands magic. And so, once again, soccer’s sorcerer responds. He picks the ball up from deep inside his half, eludes three defenders who have been shadowing him, and clips a through pass to Jorge Burruchaga that splits the German defence.

Burruchaga is free and running like the wind. He is not challenged. A desperate German goalkeeper Harald Schumacher advances down the box, to unsettle the Argentinian. But at the most important moment of his life, Burruchaga keeps his cool and sends a low shot that eludes the diving and desperate form of Schumacher. Score: 3-2.

Argentina had won the World Cup and the man responsible for the pass was already on his knees, his arms outstretched, his eyes heavenward, tears rolling down his face and a smile that made it seem he had no lips. Diego Maradona’s dream of winning the World Cup has come true.

This was the first time, since Pele, that a player had stamped his authority on the World Cup so strongly with his individual flair.

Right from the first match against South Korea, where he performed brilliantly, despite some terrible fouling, he produced soccer of the highest class.

The feints, the slow start to his runs, the sudden acceleration, the swift changes in direction, the outrageous dribbles, the perfect headers and those desperately swirling free kicks that puzzled both defenders and goalkeepers alike.

There was no footballer like Diego Armando Maradona. And on June 29, 1986, Diego Maradona was ‘El Rey’, the king of the planet.

EARLY LIFE AND CAREER

Diego Maradona was born in Buenos Aires on October 30, 1960. At birth, the midwife informed his mother: “Don’t worry. He is all right. He will live.”

He was one of eight children of a poor man who worked in a factory and lived in a slum. Maradona was a Cabecita Negra, a ‘black head’, which is a contemptuous term in Argentina for Argentines of Indian blood.

From an early age, he displayed an affinity for football. The talent was God-given. By the time he reached his teens, people had begun to notice him. At that time, he was known as ‘El Cebollita’, the little onion, because of his short, muscular stature.

At 16, he made his professional debut with the Argentinos Juniors. It was not his first choice of career. He had wanted to be an accountant, but was finally convinced his talents lay in football.

And it was true. Success came easily to him.

In 1976, César Luis Menotti, the Argentinian coach, brought Maradona into the national squad. Maradona made his international debut in a friendly match against Hungary. But in 1978, Menotti excluded Maradona from the Argentinian team for the World Cup. It was a slight that Maradona never forgot or forgave.

Later, Menotti defended himself by saying that Maradona was too young to play in such a big tournament. But Maradona was so piqued he did not speak to Menotti for six months. Then they patched up their differences. Maradona led Argentina to victory in the World Youth Championships in 1979.

The next year he led Boca Juniors to the Argentinian First Division title, and was subsequently voted South American Player of the Year in 1980 and '81.

Great things were expected from Maradona in the 1982 World Cup in Spain. By now, he was a household name in Latin America. His genius was evident although it was still rough and undisciplined. But the Spain World Cup was to be Maradona's most conspicuous failure. He was too arrogant, too gifted, to understand the necessity of teamwork. He was unable to assimilate that he could not win the cup on his own.

But to be fair, he was subjected to a sustained physical assault on his person, the likes of which had never been seen before. A continuous, desperate need to cripple his genius.

Time and time again, he was brought down, and this was most pronounced in the match against Italy. Claudio Gentile was policing him. Maradona realised as he was chopped down again and again the referee would not come to his rescue.

Gentile justified his tough tactics by saying, “This is not a dance academy.”

True, but neither was it a dojo for karatekas.

Expectedly, Maradona's patience was tested. It finally snapped during the match against Brazil where he committed a grievous foul on Batista. He was shown the red card and ejected from the field. It was the end of the Spanish nightmare.

After Spain, he signed on to play in Barcelona, but he suffered from boredom and injuries. He lasted there for barely a year before, in 1984, Napoli paid $8.3 million and lured him away. He has been there ever since and has helped Napoli win the league title in 1989 and 1990.

He still looks good for a couple of years more.

THE MAN

Diego Maradona is a short man, 5’5” in height. He is so short and so muscular, yet this ensures a low centre of gravity, which is so vital to his balance, his feints, his success. Furthermore, he has superb athletic gifts which he blends with an intuitive brain. He is emotional and gregarious. These character traits are similar to Naples and its people. That’s why there is so much affection for Maradona in Naples.

He is also a family man. His parents and brothers and sisters spend several months of the year in Naples. “I can’t spend more than two weeks without my family,” he said. “One of my brothers has to always be with me.”

For his parents, he bought a comfortable home in suburban Buenos Aires. He said that after a lifetime of struggle, his parents deserved a rest. He has employed a vast number of his friends from his earlier days in a company called Maradona Productions.

And yet, despite this generous side to his character, there are certain inconsistencies in him. He is apt to lose his temper easily. Throughout his career, he had scuffles with photographers and journalists.

Once, when he was about to be interviewed by an Italian journalist for a television programme, he yelled at the scribe because he had written negatively about his performance. The journalist had no option but to leave.

In Barcelona in 1983, he used to have dinner parties where he would serve guests, holding the plates in both hands while he bounced a football on his thighs. Then, late in the night, carloads of people used to descend on a restaurant or a cinema and occupy it for the night.

It was said at that time his long-time agent, Jorge Cyterszpiler, was responsible for this wild life, and it may have been true because later Maradona sacked the agent in 1985.

His impulsive nature has also led him into a host of controversies. He was accused by a 22-year-old Naples woman, Cristiana Sinagra, of being the father of her illegitimate child. She said it was the result of a five-month relationship. Maradona denied the rumours, but the woman named her son Diego Armando.

He has had regular tiffs with Napoli club president Corrado Ferlaino, and he was about to be fined $600,000 for breach of contract. A year earlier, he refused to return to the club before the start of the league, was overweight, and when he did join, his performance was below par.

He accused FIFA of fixing the World Cup draw so that it would suit certain teams. And then, of course, there was his famous ‘Hand of God’ goal against England in the Mexico World Cup.

There have been so many other controversies, but Maradona can get away with it because he is rich and famous, a man whose face is recognisable across the globe, and the money is just rolling in.

He earns an estimated $2 million a year from Napoli with bonuses, including the sale of souvenirs and free tickets to and from Buenos Aires. He earns hundreds of thousands of dollars through exhibition matches.

Here are two examples:

For the 100th anniversary of the English Soccer League, there was a match between the English League team and the rest of the World XI at Wembley. After much haggling, Maradona agreed to play after he was paid a mind-boggling sum of £90,000. It meant he was earning a neat £1,000 a minute.

For an exhibition match that he played in Saudi Arabia, he was given a scimitar, studded with diamonds, costly jewellery lavished on his wife and a $30,000 appearance fee. And there are several such exhibition ties that he plays throughout the year.

THE LOVE MARRIAGE

When Maradona began playing for Argentinos Juniors years ago, he began to make a little money. It was then that he decided to move to a different area of the city. In this neighbourhood lived Claudia Villafane, the daughter of a taxi driver. She was a fan of his and had been watching him for a long time. He knew that and so, once at a local dance, he approached her.

It was the start of a 14-year romance.

By all accounts, Maradona had a successful relationship. And although he had not married her, she gave birth to two girls, Dalma Nerea and Janina Dinorah.

One day, the elder girl, Dalma, asked her mother whether she could see the wedding photographs. It was then that Maradona realised that it was time to legalise the union.

The wedding took place on November 7, 1989.

Buenos Aires newspapers billed it as the ‘Marriage of the Decade’. There were 1,100 guests. Maradona had flown in on a private jet more than 200 team members and friends from Naples and lodged them in three of the best hotels in the city.

There was a civil registry marriage followed by a Roman Catholic marriage.

Maradona was dressed in a black morning suit with a grey waistcoat and matching bow tie, with a diamond earring. His wife was wearing a white gown with a diamond train of 30 metres. Their children were the bridesmaids.

The wedding party was held in a boxing stadium and it started at 8 pm and finished at 5 am. The caviar and the drinks flowed. The wedding cake was 15 feet high and weighed 150 kilos. The couple had to climb a ladder in order to cut it.

It was a grand function. Maradona spent close to a million dollars so that he could provide his children with those elusive wedding photographs.

THE PRICE OF GENIUS

Because of his exceptional abilities, Maradona has borne the brunt of the defenders' attacks on him. Time and time again, during the course of a match, he hits the ground, sometimes with great force, sometimes with great skill in order to minimise the damage. And yet, he has shown remarkable courage and persistence.

Despite the vicious attacks on him, the chopping of his legs by defenders, the grabbing of the shirt, the punches in the face, the holding him back by putting an arm around him, he has managed to perform and score brilliantly. But the price has been high.

Here are a few examples.

In a Spanish league match against Bilbao Athletic, in 1983, the centre-back Andoni Goikoetxea, known as the ‘Butcher of Bilbao’, kicked Maradona so hard that his left leg was dislocated. He was out of action for two-and-a-half months.

In May 1985, in a World Cup qualifier in San Cristobal, Venezuela, someone in a crowd of fans kicked him on his fragile knee. The same accident took place in Colombia a few days later. When Argentina played Venezuela in a return match in Buenos Aires in June, he was again kicked on the knee.

Today, according to an orthopaedic surgeon, Maradona's leg looks like that of a man 10 years older than him. In actual fact, Maradona is 29 years old. And for 15 years, he has put immense stress on his body because of his football. He has a tendency to put on weight.

His teammates in the early days used to call him fatso, and therefore he uses drastic measures to reduce his weight.

In March this year, he was six kilos overweight. So, he enrolled himself in a clinic where he followed doctors' orders to reduce weight drastically. All these demands on the body had its effect. “Chronic Lumbago,” says the noted sportswriter Rob Hughes, “is a side effect of such wilful disregard of nature.”

There is a slight decline in skills. He takes a little longer to recover from an injury. And the fact is that he is not getting any younger. And so, although he would expectedly shine at the World Cup in Italy, it may not have the brilliance of Mexico. Nevertheless, it does not matter. His skills have thrilled billions. For one summer, in 1986, he experienced what very few people have experienced in their life.

He was El Rey, the king of the planet.

(Published in Sportsworld, May 23, 1990)

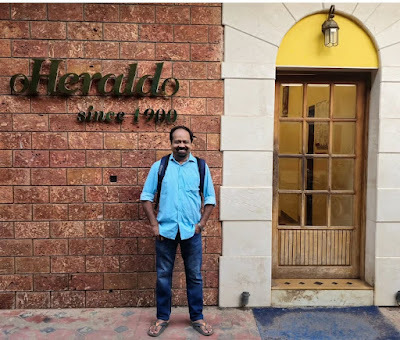

September 15, 2025

A Stellar Career: Sujit Chandra Kumar’s Rise to Editor of O Heraldo

Photos: C Sujit Chandra Kumar in front of the 'O Heraldo' office in Panjim; Sujit with his wife Vimina and son BharathBy Shevlin Sebastian I met C. Sujit Chandra Kumar over two decades ago when we became colleagues at ‘The Week’, part of the Malayala Manorama Group in Kochi. Later we were colleagues at ‘The Hindustan Times’, Mumbai. I remember our late-night conversations after work, as we walked to Mahim station to catch the train home. In all the years I have known him, I have never seen him lose his temper. He has always remained mild-mannered. These days, our conversations, mostly on the phone, revolve around ideas, concepts, philosophy, the meaning of life, and the relentless forward movement of time. Sujit has built a stellar career. He has covered major international cricket tournaments, like the Indian cricket team’s tour of the West Indies in 1997, the Asia Cup in Colombo, the Wills International Cup in Dhaka in 1998, the 1999 World Cup in England and the Champions Trophy in Sri Lanka in 2002. He also covered the series between India and Pakistan in Pakistan in 2004. In 2004, Sujit went to Sri Lanka to cover the constitutional crisis. It was a power struggle between President Chandrika Kumaratunga and Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe over how to handle the country’s long-running conflict with the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam.Sujit accompanied Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee to the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM) in Nigeria.His career has taken him to ‘The Muscat Daily’ and ‘The Deccan Chronicle’ (in both Chennai and Kochi), before he became head of the features section at ‘The Times of India’, Kochi. He later headed operations for ‘E Times’, served as senior faculty at Mathrubhumi Media School, and spent two years as Head of Corporate Communications at Manappuram Finance Limited in Valapad, near Thrissur.This month, Sujit became the editor of the Panaji-based newspaper ‘O Heraldo’. This 125-year-old newspaper began in Portuguese and shifted to English in October 1983. It’s a signal achievement, making him the first, and most likely the only one, among our peers to reach the editor’s chair in print media. “It’s a challenging role,” he said. “I am growing into it. And I am enjoying the process of influencing and getting influenced by society.” His academic record is also impressive. Sujit did his MPhil in English Language and Literature from Bharathidasan University in Tiruchirappalli and an MA in English from the University Institute of English in Thiruvananthapuram. He has a certificate in journalism from Madurai Kamaraj University. Sujit won a Chevening Scholarship to do a course at the University of Westminster, UK. For a while, he worked at ‘The Guardian’, London, where he published seven articles in the Society section. As for his personal life, Sujit is married to Vimina, a counsellor at Adarsh Charitable Trust. His son Bharath works in the marketing department of ‘The Hindu’, Kochi. All the best, Sujit, in your new assignment, and may you continue to scale new peaks in the future.

Photos: C Sujit Chandra Kumar in front of the 'O Heraldo' office in Panjim; Sujit with his wife Vimina and son BharathBy Shevlin Sebastian I met C. Sujit Chandra Kumar over two decades ago when we became colleagues at ‘The Week’, part of the Malayala Manorama Group in Kochi. Later we were colleagues at ‘The Hindustan Times’, Mumbai. I remember our late-night conversations after work, as we walked to Mahim station to catch the train home. In all the years I have known him, I have never seen him lose his temper. He has always remained mild-mannered. These days, our conversations, mostly on the phone, revolve around ideas, concepts, philosophy, the meaning of life, and the relentless forward movement of time. Sujit has built a stellar career. He has covered major international cricket tournaments, like the Indian cricket team’s tour of the West Indies in 1997, the Asia Cup in Colombo, the Wills International Cup in Dhaka in 1998, the 1999 World Cup in England and the Champions Trophy in Sri Lanka in 2002. He also covered the series between India and Pakistan in Pakistan in 2004. In 2004, Sujit went to Sri Lanka to cover the constitutional crisis. It was a power struggle between President Chandrika Kumaratunga and Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe over how to handle the country’s long-running conflict with the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam.Sujit accompanied Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee to the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM) in Nigeria.His career has taken him to ‘The Muscat Daily’ and ‘The Deccan Chronicle’ (in both Chennai and Kochi), before he became head of the features section at ‘The Times of India’, Kochi. He later headed operations for ‘E Times’, served as senior faculty at Mathrubhumi Media School, and spent two years as Head of Corporate Communications at Manappuram Finance Limited in Valapad, near Thrissur.This month, Sujit became the editor of the Panaji-based newspaper ‘O Heraldo’. This 125-year-old newspaper began in Portuguese and shifted to English in October 1983. It’s a signal achievement, making him the first, and most likely the only one, among our peers to reach the editor’s chair in print media. “It’s a challenging role,” he said. “I am growing into it. And I am enjoying the process of influencing and getting influenced by society.” His academic record is also impressive. Sujit did his MPhil in English Language and Literature from Bharathidasan University in Tiruchirappalli and an MA in English from the University Institute of English in Thiruvananthapuram. He has a certificate in journalism from Madurai Kamaraj University. Sujit won a Chevening Scholarship to do a course at the University of Westminster, UK. For a while, he worked at ‘The Guardian’, London, where he published seven articles in the Society section. As for his personal life, Sujit is married to Vimina, a counsellor at Adarsh Charitable Trust. His son Bharath works in the marketing department of ‘The Hindu’, Kochi. All the best, Sujit, in your new assignment, and may you continue to scale new peaks in the future.

September 3, 2025

A Thunderous Welcome: Arundhati Roy Launches Mother Mary Comes to Me in Kochi

By Shevlin Sebastian

It was only 5 p.m. on September 2, yet the Mother Mary Hall at St. Teresa’s College, Kochi was three-quarters full for the 6 p.m. show. It was a mix of young, middle-aged, and elderly people. All of them had looks of anticipation on their faces for the worldwide book release of Arundhati Roy’s searing memoir of her mother, ‘Mother Mary Comes to Me.’ The rush was so much that the organisers, DC Books and Penguin Random House India, set up another hall on the first floor where the event could be watched on a large screen.

In the front seats of the main hall were TV legend Prannoy Roy (a cousin of Arundhati from her father’s side) and his wife Radhika, well-known journalist Saba Naqvi, as well as Arundhati’s international publishers, like Simon Prosser, publishing director of Hamish Hamilton, UK, Nan Graham, Senior Vice President, Publisher‑at‑Large, and Editor at Scribner, the literary imprint of Simon & Schuster (USA), as well as Arundhati’s literary agents, David Godwin, Aparna Kumar and Rebecca Wehrmuth.

There was also Malayalam superstar Prithviraj’s producer wife, Supriya, actress Parvathy and Rima Kallingal, and many others from the art and cultural spheres in Kerala.

Arundhati’s relatives from her village of Aymanam were there, apart from her paternal relatives from Bengal. The staff and students of Palikoodam School, which Mary Roy founded in 1967, were also present. People had come from other parts of Kerala as well as Bangalore and Chennai.

When Arundhati arrived in the hall, she received thunderous applause. It sounded like a bounteous monsoon rainfall. This was the writer as a global literary superstar. This may be rare in future as attention spans decline and so too will reading.

Arundhati exchanged a warm embrace with her brother Lalit Kumar Christopher Roy, sharing a warm, affectionate look. Apart from her mother, she has dedicated the book to him. Arundhati, who has a mop of curly grey hair, wore a red top – to match the book cover – over bootcut jeans and red shoes.

In the introduction, award-winning Malayalam author K.R. Meera said, “To read ‘Mother Mary Comes to Me’ is to hug a porcupine. Be also ready to take medicine for sadness. It’s very difficult to describe Arundhati. She is as unpredictable as her works are. I would say that she is the only writer in India that all fascist governments in the world listen to.”

(The hall erupted in generous applause at this statement.)

Meera continued, with a smile, “She is the true Indian international writer. When Arundhati says something, it becomes her news, her headline. And she is the only writer who is known from Kashmir to Tamil Nadu.”

In response, Arundhati said, “My God, almost everybody that I love is gathered in this one room. Except for a few people who aren't in the country. That is a pretty dangerous thing given our government.” The hall again broke into loud applause. “Anyway, I said, for a normal person this would be her wedding or her funeral. But thank God, I am not normal. I am a writer. It’s a book launch.”

She continued, “I want to say that there are many Mother Marys here. One is the Blessed Virgin, for whom this hall is named after. Another is Paul McCartney's Mother Mary, who is in the song [Let It Be]. The third one is ours and she is neither of them. I am actually here to do an introduction to a person who has been my support from the time I was three years old. A man who I love beyond measure. This is my brother LKC Roy, who is going to sing ‘Let It Be’.”

When Arundhati speaks, there is tremulousness at the core of her voice. It sounds like a woman who has suffered much, but has overcome her pain with a sweet smile.

Lalit, who plays the guitar with his left hand, sang a rousing rendition of ‘Let It Be’ accompanied by a young and talented singer, Raina John.

Arundhati then read from the first chapter, titled 'Gangster’. Here is the opening paragraph:

‘She chose September, that most excellent month, to make her move. The monsoon had receded, leaving Kerala gleaming like an emerald strip between the mountains and the sea. As the plane banked to land, and the earth rose to greet us, I couldn’t believe that topography could cause such palpable, physical pain. I had never known that beloved landscape, never imagined it, never evoked it, without her being part of it. I couldn’t think of those hills and trees, the green rivers, the shrinking, cemented-over rice fields with giant billboards rising out of them advertising awful wedding saris and even worse jewellery, without thinking of her. She was woven through it all, taller in my mind than any billboard, more perilous than any river in spate, more relentless than the rain, more present than the sea itself. How could this have happened? How? She checked out with no advance notice. Typically unpredictable.’

Manasi Subramaniam, Editor-in-Chief and Vice-President of Penguin Random House India, who edited the book, gave her view:

“This is a book about freedom,” she said. “Not the kind flattened into slogans or repackaged as lifestyle. This is a messier, more volatile kind. Freedom as exposure, as rupture, as a series of deliberate choices made in full view of power. The freedom to speak, to dissent, to withdraw, to make and unmake and remake a life.

She took a breath and continued, “These are the freedoms that Arundhati Roy insists upon. And they are never theoretical. They are lived, contested, refused, reclaimed. None of it unfolds in isolation. These are not private gestures. These are public acts with consequences. They take shape inside systems that reward obedience and punish deviation. Where language itself is a site of conflict. And yet, she does not cede ground.”

She paused and said forcefully, “This book will outlast us all. It will outlast you. It will outlast me. It will outlast its author.”

Manasi then had a conversation with Arundhati.

Arundhati struck a sombre note when she said, “I do want us to remember that while this book is coming out, it is written in the time of one of the most horrible genocides of the 21st century in Gaza. In full public view. It is easier for us to reach for images of children being starved in Gaza than it is for a glass of water at night. And it is the shame of all of us that we appear to be helpless to stop it because there is a schism now between governments and people, not just in our country, but everywhere.

“I also want to say that today, just as I got ready to come up on stage, the High Court has once again denied bail to [PhD scholar in history at JNU] Umar Khalid and to many of my friends who have been in prison for five years, just like they kept my friend, [Professor GN] Sai Baba in prison for ten years before he was declared innocent and acquitted and he came out and died [on October 12, 2024]. So, yes, I mean, these are terrible things that happen even while literature is and must be written and we must keep on insisting there are other ways of thinking, not just about public things, but also about private things.”

And during the course of this conversation, Arundhati gave a full description of her mother: “In that conservative, stifling little South Indian town where in those days women were only allowed the option of flowing virtue or its affectation, my mother conducted herself with the edginess of a gangster. I watched her unleash all of herself — her genius, her eccentricity, her radical kindness, her militant courage, her ruthlessness, her generosity, her cruelty, her bullying, her hyper-brittleness, and her wild, unpredictable temper — with complete abandon on our tiny, insular, Syrian Christian society which, because of its education and relative wealth, was sequestered from the swirling violence and debilitating poverty in the rest of the country.”

In the end, this was a soaring evening that sent hearts aflutter and for a few brief moments we tasted the breath of pure freedom that has been missing in this country for the past several years.

(Published in rediff.com)

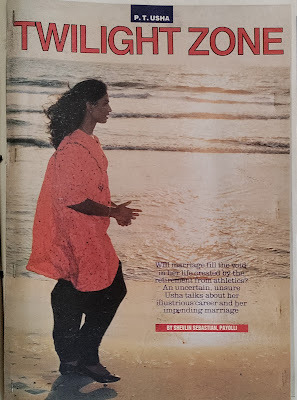

August 27, 2025

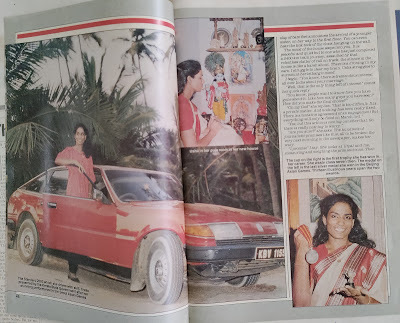

Inside Usha’s world

Athletic legend PT Usha is in a happy frame of mind. The marriage of her son Dr. Vignesh Ujjwal with Krishna took place on August 25. Ujjwal, who has specialised in sports medicine, is a doctor at the Usha School of Athletics.

Usha is a Rajya Sabha member and president of the Indian Olympic Association.

In the 1980’ and 90s, Usha dominated the national consciousness with her exploits at the Asian level and her heartbreak of missing a bronze medal at the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics by 1/100 th of a second.

According to AI, Usha has won a total of 101 international medals.

The breakdown is roughly: Gold: 47-50; Silver: 22-25. Bronze: 10-15.

The following piece was published in the Sportsworld issue of March 6, 1991. It was a time when Usha had retired and was about to get married.

COLUMN: Tunnel of Time

By Shevlin Sebastian/Payyolli

Photographs: Utpal Sorkar

The road is narrow.

On the left, there is a small cigarette shop; a few young men stand near it and look at us curiously. On the right, a thatched-roofed cinema hall called Reshmi Talkies.

Further down the narrow tarred road is the Block Development Office.

A curve on the road, later, suddenly in the distance… the big, sprawling yellow-coloured house of P. T. Usha.

The black gate, of shoulder height, has a sign on the wall near it – black letters on white marble – that says “Usha”, the house name. In the open garage, underneath a roof, is a gleaming Standard 2000. In an adjacent garage is a blue Maruti.

As we move towards the door, photographer Utpal Sorkar’s brand new Ray-Ban sunglasses slip from his hand and fall to the cement ground. The right lens is completely shattered. Utpal looks shocked. He picks up the small glass pieces and throws them towards a grassy verge. ‘Bad sign!’ he mutters to himself.

We ring the bell.

After a while Usha opens the door. She smiles but is looking listless, a little bored. She invites us in. It is a large hall. One’s attention is immediately drawn to an incredible showcase that spans a whole wall. It is filled with rows of medals, cups, mementos and souvenirs. On the right, near the door, is a staircase that leads up to the first floor.

We sit down.

It is very silent in the house. You can hear the birds chatter in the tree on the lawn. You can hear the sound of plates being cleaned in the kitchen. You can hear the tick-tock of the clock hanging on the wall. The slap of bare feet announces the arrival of a younger sister, on her way to the first floor.

The mood of the house seeps into you. It is peaceful and quiet, but to one who has just completed a 2400 km train journey, assaulted by that relentless clatter of rail on track, the silence in the house is like a harsh shout. There is a droning sound in my ears. I struggle to clear my brain.

Usha struggles to clear her lethargic mood.

I begin: “You know there is tremendous interest all over India about your marriage.”

“Well, that is the only thing left of interest,” comes her quick reply.

“You know people want to know how you have gone about it. Like how many guys you have seen? How did you make the final choice?”

“Oh, dear,” she replies, “that is too difficult. It’s a private matter. And nothing has been really fixed. There is a tentative agreement for an engagement, but everything will only be fixed on March 3rd.”

“Yes, but this article is coming out after that. So there is really nothing to worry about.”

“Are you sure?” she asks. The hundreds of journalistic promises like this, all to be broken the very next morning in the newspaper, make her wary.

“I promise!” I say.

She looks at Utpal and me, measuring and weighing the pros and cons. Then she smiles and begins to speak.

Her voice is her most distinctive feature. It is a strong, determined voice. It is a voice that is patently honest. It is a voice that never forgets that she is a small town girl. And yet the voice can suddenly give way to embarrassing giggles, and to tremors of excitement. And if you hear and rehear her voice on the dictaphone, you can detect that, at the core of it, there are strands of nervousness. The voice does not indicate the runner.

On the track, Usha is bold all the way. She runs with fluid strength, with utter confidence. Her running style can leave you gasping in admiration. But off the track, her confidence can sometimes flounder. A question about “the positive and negative aspects of fame,” has her lowering her eyes to the ground, swallowing hard, the Adam’s apple bobbing, and then she asks simply, “Could you explain that question again? I can’t understand it.”

The question is rephrased and then she breaks into a flood of words, glad to have a say on the subject and embarrassed that she did not initially understand. Yet her eyes are steady, direct and penetrating. And later, as the day wears on, she speaks a lot, and her confidence increases; her eyes hold one with their fierce determination.

ON MARRIAGE

I don’t know how many proposals have come but there have been quite a few. In some cases everything seemed okay but something was not right with the family. Or the family was all right but the person was not. For quite a few, they did not have the necessary height. I am 5’7”.

Then in some cases where everything seemed right, good family, good job, good height, close relatives of the boy’s family said, “It is not good to be Usha’s husband. You will be in her shadow all the time.”

THE FINAL CHOICE

His name is V. Srinivasan. He’s about six feet tall. He was a former university level kabaddi player and I could sense immediately that he had a keen interest in sports. That was very important for me. I wanted to marry a man who is understanding and gentle and soft, and liked sports a lot.

Srinivasan seems to be like this. At present he is a Circle Inspector in the CISF (Central Industrial Security Force) in Bhopal. After our marriage, he hopes to get transferred to Madras and I should also get a posting there. So we intend to start our family life in Madras. He is 31 years old and is one of two sons. His mother died when he was very young. But he was brought up by close relatives.

His father is retired and lives with his second family in Calcutta, although Srinivasan is originally from Trichur in Malappuram district. The marriage is fixed for April 26th but everything is still unclear at this stage.

The doorbell rings. Usha goes to the door. There’s another visitor to see her. He is in his early fifties, greying hair, thick spectacles, blue shirt and a crisp white dhoti. Usha asks him to sit down on a chair at the entrance, and then comes back. Once again, she sits down but she is distracted. It takes quite a while to get her back on track.

ON FAME:

I get a lot of affection from people. And that would not have been possible if I was not famous. And it is so wonderful to meet different kinds of people. This has been my greatest joy, to meet such a wide variety of people, each different and unique. But fame can get to you, also.

For example, I cannot go shopping in peace. If I go to a market, it’s just a matter of time before people recognise me and there are whispers of “Usha, Usha.” Then they ask for photographs and sometimes take pictures with me. I don’t mind it. But the result is that I can’t shop in peace.

ON HER PRESENT MOOD AFTER RETIREMENT

After the Beijing Asian Games {1990}, there has been a complete absence of tension. Normally, when I was an active athlete, there was this ever-present feeling of tension. Now it is no longer there.

From a very early age, I used to get up early in the morning for training. There was always this same sense of purpose and direction as soon as I got up. I had something to do. Something important. But nowadays when I get up, and even now I get up very early in the morning, I lie in bed and feel depressed. I become listless. And this mood carries on till the afternoon. But then slowly the mood lifts and by evening I am back to my high spirits once again.

I miss the excitement. But if I start to do something, like write a letter or something, my concentration returns and I feel better. Like I am already feeling better talking to you. There is something to do now.

At this point, Utpal interrupts, “Excuse me Usha, but could I have a glass of water?”

“Sure, why not,” she says, springing up from the chair.

I look at Utpal puzzled. Her mood was just improving. There was animation in her eyes. She was speaking with enthusiasm, and then this interruption.

“We were in good flow,” I said.

“Yes, I know,” he replies. “But I had to interrupt for a particular reason. The man who is sitting outside is a journalist and he is taking down all that Usha is saying. And Usha is opening up. God only knows where he is going to publish all this. And anyway, it’s not the right thing, is it?”

Usha appears with two glasses of lemonade, and then we tell her why we interrupted her. She is non-committal, but then we suggest she finish off the interview with the other journalist. Usha agrees, and calls the journalist in. He comes in, smiles sheepishly at us, and Usha takes him to the dining room. We drink our lemonade and explore the house.

On the landing leading to the first floor is a room to the right. This is Usha’s room. It is simple, bare and unpretentious. The air-conditioner is switched off. The walls are painted a soothing blue. On the table, there is a tape recorder and cassettes of Yesudas and Mohammed Rafi lie scattered about.

On the wall, there is a superb picture of the Great Wall of China. There is a double bed with the sheet smoothed down. It is simple and clean. There is nothing else in the room.

We go up to the first floor. On the right is a small puja room. There are two other bedrooms with attached baths. The house is neat, everything in its place.

We hang around; we look out through the window and we can see coconut trees in the distance. A breeze blows; the leaves shake in response. The sunlight streams in through the windows and lights up the mosaic floor. Time passes. It is a little unnerving to adjust to nature’s silence after the din of the city.

Usha calls out. The interview with the Malayali journalist is over.

We come down the stairs and again sit down.

“You must have lunch!” Usha says.

“Nothing doing,” we reply. “We will go to a restaurant.”

“No, you have come all the way from Calcutta. You must have lunch here.”

“Oh, please don’t worry. We will manage.”

“There is no problem here,” she says. “The food is simple and there is enough for everybody.”

It is 12:45 p.m. and there is still time for lunch.

“Why don’t we talk some more?” I suggest. She smiles and sits down.

ON HER HOUSE

After I won five gold medals at the ’85 Asian Track and Field Championships in Jakarta, the Kerala State government announced a grant of Rs 2 lakhs to build me a house. But by the time the house was completed in ’87, the total cost had shot up to Rs 5 lakhs. So I put up the rest of the money. The house was designed by a Government architect and now the whole family stays here. My brother, two younger sisters, my parents and myself. My other two sisters are married and live elsewhere.

ON HOW MUCH MONEY SHE HAS EARNED

I cannot say how much I have earned. But now, people expect me to keep up a certain standard of living. I cannot travel by bus. Because people will say, “Look, she has two cars, why does she need to travel by bus?” I have to maintain this Standard 2000. It was given to us by the State Government after my performance in the Seoul Asian Games.

I have noticed that people are shocked by the awards. But there is also a lot of hard work behind the winning of all these international races. It’s not easy. And after this we have to run about to get the money. Sometimes, it takes a whole year before the cheque is in my hands. You see, this is how the bureaucracy works here in India.

ON HER HUMILIATION AFTER THE SEOUL OLYMPICS (Usha failed to go past the heats in the 400m hurdles)

I was abused and reviled after those Games. For the first time, I deeply resented what I had chosen as an athletics career. It was terrible. Nobody seemed to try to understand me. I am also human. I am also like other people. I was just sad and could not see my way well. Why couldn’t people understand that?

Even in Payyoli, people used to throw stones at the house and make hooting sounds. I had reached a stage when I was terrified to go out of the house. Posters were put all over the place belittling me. I was depressed and lost at least 10 kg of weight due to the stress. Of course, later I understood that people had high expectations of me and they were hurt.

And I did come back strongly at the Asian Track and Field championships in New Delhi, in which I won four gold medals and broke the records that I had set in Jakarta. That was a fitting reply to my critics.

ON HER FAN MAIL

I receive all kinds of letters. At present, I receive a lot of letters saying that my departure has been a loss to Indian athletics. Some boys write funny letters. There are letters asking for my photo so that they can frame it. It is fun reading them. They come from all over India and I used to get a lot of letters from all over the world. In thousands, but now I get very few. It is physically impossible to reply to all the letters. But what is most interesting is the addresses. Sometimes, there’s a picture of me on the cover and underneath it is written: P.T. Usha, Payyoli. Sometimes the letters are just addressed to The Payyoli Express, Kerala.

It is 1.30 p.m.

Usha’s father has just come home from his tailoring shop near the village centre. He is a tall, straight-backed man in his early sixties, with a mop of wavy hair. A broad forehead and a ready smile, his bearing indicates a principled man and one can deduce where Usha inherits her qualities of discipline, hard work and dedication. We talked a little.

A photo session with the family is arranged and Usha’s two younger sisters, Susha and Suma, talk about what dress to wear. Finally, everyone sits on the steps leading to the house and the tripod is set up. The interaction between the family members is open and direct and frank. Suddenly Usha asks, “Where is Pradeep?”

“He has gone out,” her father replies and so the brother is left out of the family portrait.

After the photo session is over, we go in and sit down. And suddenly I realise that at the rate we are going, the assignment can be completed in a day and not two days as we originally thought.

I tell Utpal, “I think we can leave tonight.”

Aloud, I ask, “Excuse me, Usha, is Mr. Nambiar around?”

“Yes,” she says and moves to the telephone. “He lives nearby.”

“Actually the reason is that we want a couple of tickets on tonight’s Trivandrum Mail. That’s just why we wanted to meet Mr. Nambiar. Maybe he could arrange it.”

“But I can arrange it!” Usha exclaims, a rising inflection to her voice. “Did you forget that I was with the Railways?”

“Oh!” I say.

She rings up the Station Master at Vatakara, 12 kilometres from Payyoli. “Hi, this is Usha. Are there tickets available on tonight’s Trivandrum Mail?”

Of course tickets are available due to the MP’s quota. But we have to go to Vatakara to collect the tickets.

Usha smiles and says, “Now will you please have lunch.”

The meal is simple.

There is mutton curry, beans, another vegetable dish, mango curry and rice and papad. Usha eats with us while her mother and a sister hover around, serving the dishes. We are in fact ravenous and attack the food. As we eat, Usha talks some more.

ON THE FUTURE OF KERALA ATHLETICS

It is definitely going down. There seems to be a lull now. There are a lot of potentially good athletes but they don’t seem to be interested in excelling anymore. I went to my former sports school in Cannanore and I could see that the facilities had improved drastically. In my time, we had no beds. We had to join two benches together to make a bed. For 80 students, there were just two bathrooms. But now things have changed but somehow, people don’t seem to be interested in excelling anymore.

ON KERALA’S REACTION TO HER SUCCESS

Well, here’s an example. The railway track is nearby. But very few trains stop at Payyoli, most stop at Vatakara. But when I won four gold medals after the Seoul Asian Games, the train was forced to make an unscheduled stop at Payyoli because there were so many people at the station, who were waiting to greet me. Those times are gone now.

The meal is over and we manage another photo session in the evening. Then Utpal and I leave for Vatakara to get the tickets.

In Vatakara, the tickets are collected with ease. The Assistant Station Master is charming and solicitous and we take a return bus to Payyoli. It is the peak of a summer afternoon. There is tiredness in the mind and the body. Both of us fall asleep and by the time we wake, Payyoli is ten kilometres away.

We jump off, brushing the sleep from our eyes and blaming each other.

We wait at a bus stop. After a while, a bus comes up in a rush of squealing brakes and screeching tyres, we jump in and jump out at the next stop. The bus is not going to Payyoli. A lone autorickshaw goes past and we are beaten to it by four giggling schoolgirls. We are getting desperate. Time is passing. Suddenly a trekker comes past and we wave it down. It is filled with people. There is no place to sit.

“Are you going to Payyoli?” we ask. They nod and we hang at the back of the vehicle, one foot barely managing a toe-hold, the other leg floating in space, our hands gripping the bars of the trekker.

Usha breaks into loud laughter when we tell her our adventures.

“How silly,” she says. “As soon as you got into the first bus, you should have told the conductor that you wanted to go to Usha’s place and they would have dropped you at the right stop.”

There is no hint of arrogance when she says this. Because it is a fact. Everybody knows where Usha stays. After all, it is she and she alone who has singlehandedly put the name of Payyoli on India’s map.

We take some quick pictures inside the house. Usha is dressed in a sari. Photos are taken of her in her room, coming down the stairs, lighting up the diya, holding her medals. The sun is setting and we have to hurry to the beach to get the sunlight shining on the water.

Usha changes into a red salwar and we get into the Standard 2000. Brother Pradeep drives while Usha and her sister Suma sit at the back. People stare at us as we go down the road. It is like wearing a sign over your head. But Usha is used to it. I take the chance to ask a few more questions.

THE QUALITIES NEEDED TO BE A SUCCESSFUL ATHLETE

If you want to achieve anything you must be willing to work hard. There must be a will to succeed. It is not easy. There is a lot of hardship involved. One should not be discouraged by setbacks but continue training day in and day out. Like, after 1988, I could have stopped running, but it was determination that kept me going. So, despite everything, one must persevere. One should never lose courage but keep struggling. And then one day success will come to you.

ON WHY INDIAN ATHLETES PERFORM SO POORLY ABROAD

They don’t work hard. Firstly, very few people come to athletics as an end in itself. Mostly, they train in order to get a job. And once they have got a job, most of their ambitions are over. Perhaps a few of them want to get promoted, so they work a little bit more.

Suppose, for example, the athlete comes from a good family. Then he or she is trying to get a seat on the sports quota for medical or engineering courses. Once they secure admission their interest in sports dies down. That is the difference between the other athletes and me. For me, excellence in athletics was an end in itself.

We arrive at the beach. And suddenly, it is wonderful. The setting sun, the relentless waves breaking on the shore, and the breeze flapping our collars about. Tension seems to dissolve like foam on top of a wave. One feels light-hearted. Usha smiles. Utpal begins to get hyper-excited. The photo opportunity looks superb.

Fishermen’s children begin to follow us as we walk further and further away from groups of people who have come to experience the evening breeze. And now you can see a distinct change in Usha. She turns to beckon to me.

“See this!” she says, pointing at the sand. “It is soft, and yet it is hard. I used to practise hurdles on this surface. This is the most wonderful place on earth. How I loved training on the beach. Remember, I used to run over the hurdles here and so you can imagine how easy it was for me when I ran on the track. This is the best training ground for me. It differed from day to day.

Sometimes I went for long jogs. Sometimes I did short sprints. Sometimes, I practised the hurdles. And I had to keep an idea of the tides. Whether it was high or low tide. But the best thing was that I was away from people.

I dearly wished there was a stadium nearby. Then there would have been no need for me to go all the way to Bangalore or Delhi. I could have trained here, my mother would have given me the best food and I would not have suffered from homesickness at all.

Then she stops speaking and smiles. She willingly listens to Utpal as he instructs her on how to pose. She sits on a boat moored on the beach. She looks beautiful because she has a deep sense of well-being on her face. And yet, as one watches her, as she moves about on the sand, there is a feeling of sadness.

She must now realise that everything is in the past. At an age where other people are beginning to get a hold on their careers, this talented woman is at the end of hers. Life is now spread out in front of her and there is just blankness.

I ask her: “What are your future plans?”

Immediately, a shadow falls across her face.

“I really don’t know what I am going to do,” she says. “I have never thought about it at all.”

I regretted suddenly asking this question. A few children come up and stand around Usha, all smiling brightly. Utpal decides to take a picture of Usha with them.

Usha’s mood changes again. She seems to have lightning changes of mood. She smiles now and taps the heads of the children, in a gentle show of affection.

We reach the car and she tells Pradeep, “I will drive.” And with expert ease, she turns the car around and drives down the narrow road. Again, she has that look of concentration on her face.

We reach the main road and we suggest that she drop us off at the bus stop.

“Nothing doing**,” she replies, “Have tea at the house and then you can leave.”

And so we return to the house. Tea is already laid out. Cakes, biscuits, and coconut sweets. It is dusk now and the dining room is partially in darkness.

A casual question: “How many guests do you have in a day?”

“So many that we lose count,” she replies. “Some days, principals of schools ring up saying that their children are coming to Payyoli and they would like to see the trophy display. They make sure that I am at home. Photographs are taken with the children and I sign autograph books. This is official. But there are people who are dropping in all the time just to talk to me, to listen to me. They are complete strangers but I guess they feel comfortable and welcome and so the word spreads. Of course, now with the STD facility, we have visitors every Friday to get calls from relatives in the Gulf.”

“Why do they have to come here?” one asks, puzzled.

“Because you will be surprised to know that I have the only STD facility in this village. And people come here on Fridays because it is a holiday in the Gulf and calls are cheaper for those calling from there. And now the calls have increased three-fold since the Gulf War. To put it dramatically, in Payyoli I am the only link to the Gulf world.

This phone was installed because I had specifically requested Arjun Singh, who was then Communications Minister, whether he could arrange such a phone to be installed. When I am in training camps I used to feel lonely and miss the family. It is only because of this phone, that I could call up my parents from all the way in Delhi and wherever else I was.”

Tea is over and it is time to leave. It has been a long, exhausting and eventful day. There is a sense of weariness although Usha still seems to be in high energy. We get up and I say, “One last question. Has luck anything to do with your success as an athlete?”

“Luck,” Usha exclaims, her black eyes widening in emphasis. “Luck, luck, luck. Everything has to do with luck. I was lucky to have a coach from the very beginning of my athletics career. I was lucky that when I reached Standard Eight, such a concept as a sports school came into being. I was lucky that I had a talent for running. Of course, it has got to do with luck. Otherwise how can a small-town girl like me become an Asian champion? Luck, and I believe very strongly that God’s support made the difference. I think that without God’s support, nothing would have been possible!”

(Published in Sportsworld, March 6, 1991)

August 19, 2025

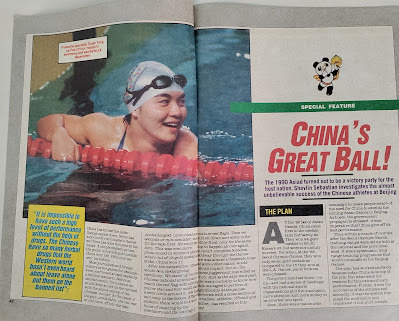

CHINA’S GREAT BALL!

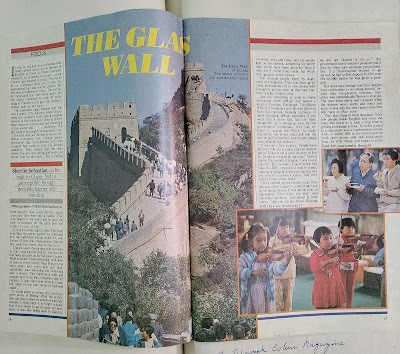

This is a rare analytical piece by me.Throughout my career, I tended to focus on the human story. This was thanks to my mother, who from the time I was a baby was constantly telling me stories.So stories became fascinating for me. Whenever I meet people, I am keen to know their stories. Everybody has a river of stories flowing inside them.I also realised the human story never grows old. It can withstand the passage of time. So I stuck to story. And I continue to do so.COLUMN: The Tunnel Of Time The 1990 Asiad turned out to be a victory party for the host nation. Shevlin Sebastian investigates the almost unbelievable success of the Chinese athletes at BeijingPhotos: Nikhil BhattacharyaChina has turned the Asian Games upside down. Never has any country so dominated a Games as China did at this year’s Asiad. A simple statistic proves the point: of the 262 gold medals at stake, China won 183. By contrast, India collected just 59 medals. Most journalists and foreign visitors at the Games were confronted with an extraordinary spectacle. We would keep an eye on a race or an event, wait for it to start. The pistol would go, and predictably, the crack of the gun was followed by the sight of the red flag moving into the lead, unchallenged, untouched. Seconds or minutes later, the same flag would break the tape first. No surprise at all.The result: complete boredom.Midway through the Games, out of 18 gold medals at stake, China won 17. There was almost a desperate hope that some other nation would win, just to make an impact. But no, the Chinese juggernaut just rolled on. Each medal ceremony became a routine. We would stand up for the national anthem, watch the red flag with one large yellow star and four small ones in a semicircle sway in the breeze, and hear the anthem repeatedly. Hours of cheering by the spectators, the waving of miniature red flags, and then another medal for China. As the days went past, curiosity grew about how the Chinese managed to perform so magnificently at the Games. Interviews with a cross-section of journalists, athletes, officials, and trainers revealed the answer: planning and preparation on a massive scale.THE PLANAt the ’86 Seoul Asian Games, China came first in the medals tally but only narrowly, with 94 gold medals to South Korea’s 93. But even then, Beijing worried. Yet when China competed in the Seoul Olympics two years later, it won only 10 gold medals. This was in sharp contrast to the 50 medals claimed at the 1984 Los Angeles Games.The government sat down, or rather, called in the national sports organisations, and reviewed the situation. The conclusion: more attention and more money had to be diverted into sport. Soon, there was a nationwide campaign to make people aware of the need for China to excel at the Games.As hosts of the 1990 Asiad in Beijing, the government propagandists stressed, it was imperative that China give its best performance.Thus, within a couple of months after the Seoul Asian Games, training camps were set up both at the national and provincial level. It was a systematic, long-term programme aimed to culminate at the Beijing Asiad.The plan has worked perfectly. Because of it, China is today on top of the pile. But what were the other factors that contributed to this extraordinary success?THE MOTIVATING FACTORSWhat made the Chinese athletes train so assiduously, to push themselves so hard, that they performed so well? What motivated them? A) Patriotism B) Money C) FearPATRIOTISM: Perhaps one of the singular and unwavering qualities of the Chinese people is their deep sense of patriotism. Frequently, on the winners’ rostrum, as the national anthem was being played, a Chinese gold medallist would wipe away tears of joy. “No matter how angry they may be against the government,” said Wang Shenguin, an official, “we are a deeply patriotic people.”Moreover, this was the first time China was holding such an extravagant sporting event, where the eyes of Asia would be on them. The Chinese believed that as host nation, not only should they show utmost respect and deference to foreign guests, but they must also put up their best performance. And you could see it on hoardings across Beijing: ‘We must do our best’ or ‘We must stand up proud in the world.’ The message was clear: China must rule.MONEY Another great incentive for intensive and sustained training was the prospect of money and jobs. In China, the average person and the average athlete earns about 100 yuan (Rs. 500) a month. Although clothing, food and shelter are subsidised (for example, in Beijing, rents of apartments are fixed at five per cent of your salary), living is a tight financial squeeze. For most athletes, a good performance promised a better future.The government offered incentives of 3,000 to 5,000 yuan (Rs. 13,000–15,000) for a gold medal. To Indians, this might not be much. But, says Zweng Huang, an athlete, “In China, it is a lot of money.”The general feeling that sporting success could mean more money was reinforced by the great, successful former gymnast Li Ning after retiring from competition.The multiple Olympic gold medallist started his own business, a clothing line in his own name, and because of his famous name has been highly successful. Time and again, in Beijing, one came across young people wearing T-shirts with the name Li Ning emblazoned in white across the back.Li Ning is rich now, and has a flat and a car, and sport was his route to money and fame. He was a shining example for all to see.FEARThe fear of the State, the repercussions of failure, also accelerated the athletes’ drive. The State was spending money on the athletes and the State wanted rewards.The State, in the form of coaches and officials, put immense pressure on the athletes, and there have been documented cases of athletes suffering a nervous breakdown because of these pressures.On the flip side was the danger of failing. In China, there are hundreds of athletes who have not won anything. They are unknown. And because they were involved in sports for so long, they were unable to develop a new skill.Some tried to go back to university but most settled for working jobs in departmental stores or as gardeners and workers in factories. “It’s a tragedy,” said an athlete who requested anonymity. “If you don’t win anything you are nowhere. No education and no medal. People don’t care about you.”POVERTY, DRUGS AND TRAININGAnother interesting fact was that most of these athletes came from low middle-class or poor families. Poverty thus became another factor. For example, the new gymnastics star, Li Jing, comes from a poor family in Hunan province. He was selected for gymnastics at an early age, struggled and practised remorselessly, and now, after twelve years, has achieved nationwide fame.So, it was these factors that have collectively pushed the Chinese to excel. Yet it is imperative to add that they were aided by a superb system set up by the Chinese sporting authorities. The two-year camps were brilliantly organised on scientific lines, programmed so that an athlete would reach his peak during the Games.An average day in the camps would consist of long-distance runs, weight training, physical fitness and practising for a specific event. Then there would be psychological classes, the need to develop mental strength and to stay calm. There were further classes then on strategy and tactics.This took about four hours every day. It was four hours for two long years. At the most, the athletes were allowed to go out for a few days during the spring festival, which is in February, and in October, when the National Day celebrations took place. Otherwise, it was just training, training, and more training.China was also blessed by the fact that they had highly competent coaches. Said Win Shangquin, a Xinhua news agency journalist: “A qualified coach is necessary. Hard training is one thing, but good coaching is needed to complement the hard training. China, thankfully, has many qualified coaches, especially in cities like Beijing, Shanghai, and Canton. And because the government was keen, all the training camps were provided with the best equipment.”Yet there were also consistent accusations of widespread doping. No single Chinese person admitted in private about this, such was their deep fear or perhaps their deep patriotism. But as Jeremy Walker of the South China Morning Post said: “I think it is obvious. It is impossible to have such a high level of performance without the help of drugs. I am sure the 400m hurdles winner was on drugs. She looked so tired after the race. And there were hints of a moustache and a beard on her face. And the Chinese have so many herbal drugs that the Western world has not even heard about, let alone put them on the banned list.”And here in Beijing, with the doping tests being supervised by the organising committee (and let’s face it, China has a powerful voice in the Olympic Council of Asia), the chances of a Chinese getting caught was relatively slim. “I am sorry to say it but I am convinced that they are taking drugs.”NATURAL SELECTIONTo produce winners, you need to select athletes from a large section of the population, so that the best talent can be weeded out. And in China, they have a superb system that enables them to select athletes at an early age.Firstly, when a child shows a particular talent for a particular discipline, the school recommends his name to the sports council of the province. The sports council then tests whether he is a deserving case. If yes, they recommend his name to the national association. The national association receives a list of names and then selects and chooses the best among them. The selected few are put into sports schools.In these sports schools, children are given special training in their specific sport. They do their normal studies but, in the evening, they are given two hours of special training. They are put on a free diet but the food is rich and nutritious.The admission age for these schools depends on each specific sport, but the age varies from 8 to 13 years. For weightlifting, it is from 14 to 17, while for gymnastics, children are admitted when they are five years old. Five years old! Can you imagine putting a child under intensive and systematic training at five years of age?Every now and then, there is a monitoring of the student. If he does not improve after a period of training, he must leave. On the other hand, an outstanding student may be selected by a city, a province, or a national side.There are 3,411 such schools across China and so far, they have produced 80–90 percent of China’s national team and 90 percent of China’s World and Asian record holders. Names like high jump record holder Zhou Jianhua and Li Ning are the ones that come to mind. They are all products of these sports schools.But there is now a backlash against these sports schools across China. Parents now resent losing their children to a sports school. And this has become even more pronounced ever since the government announced that a couple can have only one child.“So, people don’t want their children to go into sports,” said a People’s Daily journalist. “When you do sports, you can’t do your studies well and if you are not successful like Li Ning, you are nowhere.”The result is that fewer children are being enrolled in these sports schools. Admitted Wang Chen, a director of a sports school: “Despite the fact that the sports school has been successful, we have a lack of promising students.”Not surprisingly, this is really worrying the Chinese sports authorities. They believe now that their chances are bleak of duplicating their present performance in Hiroshima in 1994.Nevertheless, that is the future. Today, China is the hero of the Games. Statistically they are untouchable.In swimming, out of a total of 36 gold medals at stake, they won 28. - In rowing, out of 12, they won 12. - In Wushu, out of 6, they won 6. - In cycling, out of 11, they won 6. - In weightlifting, out of 19, they won 12.And out of the 198 multiple medal winners at the Games, 82 were Chinese.You know, they made a mistake. Instead of calling it the Asian Games, they should have simply called it the Chinese National Games.(Published in Sportsworld, October 17, 1990)