Shevlin Sebastian's Blog, page 3

July 25, 2025

Murders Most Foul

Author Kulpreet Yadav focuses on seven chilling true-crime cases from all over India in his book, ‘Dial 100’. The pace is electric and the stories are heart-breaking

Author Kulpreet Yadav focuses on seven chilling true-crime cases from all over India in his book, ‘Dial 100’. The pace is electric and the stories are heart-breaking By Shevlin Sebastian

Best-selling author Kulpreet Yadav’s second true-crime book, ‘Dial 100,’ begins with style: Ravi Sunderrajan took the final sip of his whisky, placed the crystal glass down and looked around. Long-legged Indian and Eastern European hostesses were serving drinks to gamblers who were busy at different tables in the casino, their eyes focused and faces flushed. Instrumental jazz played, and the air smelled of whisky, skewered meats and expensive perfume.

This scene takes place in a floating casino anchored on the Mandovi River off Panjim, Goa. And just like that the reader is off and running.

Ravi, a bank clerk, tipped off two professional thieves from Guna in Madhya Pradesh about a scheduled transfer of Rs 300 crore being moved by his bank from Salem to Chennai for the Reserve Bank of India.

The motive? Money.

In the end it is a successful heist. The theft was discovered only nine hours later. This gave enough time for the thieves to get away.

The thieves left no clues. It took over two years to track them down.

In the next story, Kulpreet describes the rape and murder of a five-year-old in an under-construction building in Mumbai in exacting detail. It was painful to read.

Like many murderers, the assailant was an ordinary man. He studied in a convent school till Class 10, gained a diploma in engineering, spoke good English and worked in a company. Again it took clever sleuthing to bring down the culprit.

The next case is even more disturbing. In Kerala, a 29-year-old woman Jaya was raped. But Kulpreet’s description of the act was so lifelike it was almost like watching a movie. You get an idea of the horror a woman can go through when she is physically attacked.

Kulpreet writes about a child being kidnapped from a school in Delhi. The suspect, who was from Nepal, raped and murdered her, before fleeing the country. For three years, there was no movement in the case.

When the case was revived, the police, with the help of an acquaintance, lured the suspect back to India with the promise of a high-paying job. When the grieving parents — who had known the man — finally faced him again, the father delivered a resounding slap. It was a brief moment of emotional release.

There are seven cases in total. The crimes took place in Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, Kerala, Delhi, Haryana, West Bengal and Andhra Pradesh.

Kulpreet keeps the pace brisk, often leaving the reader breathless as the investigations unfold.

Kulpreet had a particular reason to write about the stories. In the preface he cites a disturbing statistic. There is a low police-to-population ratio of 150 officers per one lakh citizens. This is far below the minimum 200 mark stipulated by the United Nations. In India, this is compounded by poor salaries, long working hours and lack of advanced training.

‘And yet, despite these constraints, countless police officers rise above the odds every day,’ Kuldeep writes. ‘They go beyond the call of duty, harnessing ingenuity, determination and cutting-edge technology – often self-taught – to solve crimes that seem impossible to crack. Their dedication, often at the expense of personal comfort and family time, deserves not just recognition but also admiration.’

Kulpreet worked for 23 years in the armed forces before voluntarily retiring as a commandant in the Indian Coast Guard in 2014. ‘I took part in many anti-smuggling and piracy missions in the maritime zones of India,’ he said. ‘That gave me insight into how the police work. Over time, I befriended several officers and spent time with them. I understood how their minds were wired.’

He said he hoped to send two messages through his stories. One is that the police are not as bad as we make them out to be. ‘The second message is for would-be criminals. No matter how ‘perfect’ their crime is, there will be some officer who will use his mind or technology to nab him. I hope this will deter a lot of people and make our society a lot safer.’

When asked why it is difficult to do the perfect crime, Kulpreet said, ‘The airwaves are monitored, there are cameras everywhere. Earlier, you just had to avoid leaving fingerprints and ensure there were no eyewitnesses.’

Reviving cold cases

What has excited law enforcement is that they are now able to find the murderers of cases that are over 30 years old thanks to advances in DNA detection.

Asked whether there is a particular mandate from the government to go after these cases, Kulpreet said, ‘As far as I know, there’s no such thing. But what happens is that these cases prick the conscience of officers who haven’t been able to solve them. So, an officer after 25 years might remember a case that took place years ago that has continued to haunt him. So he revives it.’

The odds are stacked against the police. ‘They don’t have the latest technology,’ said Kulpreet. ‘The forensic labs are very few and training in this subject is scanty.’

In an interview to this reviewer on the HarperBroadcast Channel, on World Book Day, Kulpreet was asked about why true crime always had readers.

He said, ‘More than the thrill of it, people want the bad man behind bars. In true crime stories, that’s how the story ends.’

He acknowledged that readers today have shorter attention spans. So Kulpreet has adopted methods to tackle this. ‘My strategy is not to beat around the bush,’ he said. ‘I get straight to the point. A story has two parts: description and dialogue. Better to keep the description between 10-15 percent. No telling, all showing is a technique I use. Short sentences. No difficult words at all.’

He said there was a time 30 years ago when people took pride in writing good English. ‘But if you write good English today, people don’t care,’ he said. ‘They want to understand a book.’

Flowery language, he believes, can sometimes become a barrier between the reader and the story. ‘I work hard to keep it simple,’ he said. ‘My writing should be like a window pane. We need to write simply to reach readers in the WhatsApp era — otherwise, we’ll lose them.’

The future looks difficult.

A few months ago, when Kulpreet was at the P3 Terminal at Delhi airport, he visited the WH Smith book store. He got a shock when he discovered that the store had shut down. ‘When book stores are not able to sustain themselves at an airport in the capital of India – a nation of story-tellers – we are in a difficult situation.’

Kulpreet has published 16 books so far. Apart from crime, he has written on military history.

As to whether he had any tips for new writers, Kulpreet said, ‘They should write on the subject they are interested in. Also read a lot of books in the genre they want to write in. Then they will be in a nice position to write a good book.’

(Published in katha.org (Singapore)

July 22, 2025

Off the Beighton track

When my friend George Themplangad showed me that printed articles could be converted into computer text on Chat GPT, the idea arose of putting up my older pieces. I selected this article, primarily for the brilliant headline given by Sportsworld's Associate Editor David McMahon. And secondly, it might have withstood the passage of time. These type of moments can happen at a match even today. Asked to cover the Beighton Cup hockey final, I also focused on what was happening outside the field. The article was published in the Sportsworld Magazine of May 15-21, 1985. I am hoping to upload once a week. COLUMN: The Tunnel Of TimeShevlin Sebastian watched the final and monitored the crowd reaction to the matchOccasional clouds scudded across the Calcutta sky but there was no hint of rain. Standing outside the Mohun Bagan ground on the Saturday of the Beighton Cup final between Indian Airlines and EME, Jalandhar, one saw people in ones and twos, in small groups, walking purposefully across the Maidan towards the gates of the club.Paaban Bhumia is a teacher in a primary school. A stockily built 27-year-old, he had come all the way from Burdwan to watch the Beighton Cup final. ‘Well,’ he replied, on being asked the reason for coming from so far away, to witness this hockey match. ‘At least, I can see some top players.’Sailen Majumdar, 50, is a government employee who worked in Writers’ Buildings. A short man, he wore thick spectacles perched on his nose and was dressed in a white shirt and faded black pants.Why had he come to watch the game? He paused thoughtfully and replied: ‘This final features two important national teams and I want to watch them play’. Did he, by any chance, watch the matches of the Calcutta Hockey League? Sailen smiled and said, ‘The standard is so poor, that there is no use in watching.’However, unlike the hockey league, Calcuttans did not exactly ignore the Beighton Cup and the presence of star-studded teams. People began to drift in and at whistle time, there was a fairly decent crowd. The crowd was cosmopolitan, showing so effectively the diversity of the city. So, you saw the sight of a sophisticated man in a safari suit, with a helmet in his hand. Then there was the less affluent youth, wearing a cotton shirt and trousers, with mud-crusted chappals on his feet. You had the sight of a paan-chewer in a white kurta-dhoti, sitting with his palms on his thighs. Then there was the ubiquitous know-all supporter, slim and thin, who passed expert comments for the benefit of the people around him.The teams ran on to the playing field which was lustrous and green although there were a few bald patches here and there. The players began to flex their muscles and some of them took a few shots.‘Who is Number 14?’ asked a middle aged Sardarji. ‘Zafar Iqbal!’ was the slightly sardonic reply. A fat man with an enormous paunch and an unkempt beard, said very loudly: ‘Ashok Kumar is in great form. Once, in Calcutta, we had good players like Inam-ur-Rahman, Joginder Singh, and even Ashok Kumar played here once.’ The bully-off took place and the game started. The pace was fast and quick. Both teams mounted a series of attacks. Merwyn Fernandes of Indian Airlines received a pass in front of the goal and, with only the goalkeeper to beat, shot wide. A spectator commented, with a trace of bitterness, ‘There is no finish’. As the game continued, a different form of activity was noticed in the stands. A man who was selling groundnuts was roundly criticised for blocking the view. ‘Why can’t you sell your stuff during the interval?’ asked a spectator who looked fierce and angry. ‘Sorry Sahib!’ said the groundnut seller, his face showing a lifetime of compromise and endless exploitation.In a middle tier, separate and distinct, sat a young, broad-shouldered Punjabi with his new wife. She wore a purple salwar-kameez and her face looked radiant and healthy in the afternoon sun. But it was obvious that she had come to the ground for the sake of her husband because, soon after the match started, she was avidly reading a Hindi film magazine. As the match progressed, there was the occasional cheer for the good move, and heartfelt applause for a superb show of dribbling by a particular player. Sometimes, in the silence, a plaintive ‘Oh Zafar Bhai’ would be heard.Zafar Iqbal, on the left flank, roamed the area like a hungry panther. Slim and lithe, holding the stick tightly in his hands, in front of his body, he would break into a swift, furious run, the ball perfectly under his control as he flicked the ball towards the centre of the ‘D’. Sometimes, it was collected but nothing was ever converted into a goal. Sometimes, the ball went abegging. At 4 p.m, the whistle blew and it was half time, the teams still locked in a goalless draw.Spectators got up and went down the steps to the latrines. ‘Not a bad match,’ a man said, ‘at least, so far.’Suddenly, as if seeing the crowd in perspective for the first time, a bald man in a T-shirt said, ‘What do you say? This is the best crowd of the season?’ On the ground, drinks were offered to the players who slaked their thirst in obvious satisfaction. Free drinks were offered to journalists, officials and important guests. Seeing this, a spectator who sat on a bench with his friends near the corner flag decided to try his luck, but had to return, disappointed.Meanwhile, the second half started on a brisk note. Up in the sky, grey clouds ran riot completely obscuring the sun and now, the breeze that was blowing in from the Hooghly river, was cool and soothing.Indian Airline’s full-back, Veerendra Bahadur Singh, took a stinging 16-yard shot and it was collected by Merwyn Fernandes and he began a solo effort. His back was bent, his eyes on the white ball, his wrists flicking the stick this way and that, he moved down, going past one opponent and then the other. But just when it seemed that he was getting dangerous, Merwyn was suddenly dispossessed. The crowd groaned in frustration, as another attack was blunted at the right time. But, in the seventh minute, the Airlines outfit struck home. A penalty corner was collected by Vineet Kumar, who passed it on to Zafar Iqbal, and he took a shot which was deflected into the EME net through Merwyn’s stick. Airlines 1, EME 0. The latter, stung to the quick by the reverse, went furiously on the attack and they managed a penalty corner. ‘Jai Bajrang Bali’ a spectator shouted from the sidelines, ‘let there be a goal’. But the call proved abortive and as the minutes ticked away, the game began to slow down and lose direction. Very near the sidelines, a young child in a pink skirt and ponytails, barely three feet in height, ran to and fro, enjoying herself. Sometimes, when the crowd cheered or clapped loudly, she would stop, stare at the crowd with wide, curious eyes, and clap in imitation. Her father, clad in khaki, who stood a few feet away from her, smiled occasionally at her. The match drifted on and on. At 5 p.m., the whistle was blown. The players came off with tired faces. Meanwhile a few spectators swarmed on to the ground and encircled the wooden table which contained the glittering trophies and the individual awards. The announcers implored the other spectators to stay and witness the prize-giving ceremony. There was a crush of people and young players formed a barricade with their sticks. A police sergeant, with wide, bulging eyes, shouted at a constable to ‘maintain discipline’. The photographers crowded around, trying to get a vantage point.Meanwhile, the Minister for Sports, Subhas Chakravarty, was invited to speak and he said the usual stuff about the state government’s willingness to offer full support, to bring the Beighton Cup back to its former glory... etc...etc...The trophy was presented to the Airlines captain and the crowd strained to push and see. ‘Those photographers!’ a spectator said in disgust. ‘Can’t see a thing.’ The sergeant, sensing the crowd pushing forward, turned around and shouted, ‘Why can’t you all stop pushing?’The crowd fell back for a moment and as soon as he looked away, there was again a forward thrust. And, at last, all the prizes were presented and thus, the 1985 Beighton Cup came to an end.The Beighton Cup is a tournament that is still twitching, still struggling to live on, and perhaps the coverage by the radio, press and television might just about give it a new lease of life.(Published in Sportsworld, May 1985)

July 13, 2025

Awakening The Soul

In his book, ‘The Practice of Immortality’, spiritual leaderIshan Shivanand talks about the need to go in inwards and link up with thedivine energy for mental peace and happiness

By Shevlin Sebastian

In spiritual leader Ishan Shivanand’s book, ‘The Practice ofImmortality’, opposite the contents page is a quote from the BhagwadGita:

‘The Spirit is neither born nor does it die at any time. Itdoes not come into being or cease to exist. It is unborn, eternal, permanentand primeval. The Spirit is not destroyed when the body is destroyed.’

And this quote sets the tone of the book. In theintroduction, Ishan tells a story: ‘Two birds perch on the same tree,inseparable companions. One bird eats the fruit, while the other looks on. Thefirst bird is our finite self, feeding on the pleasures and pains of its deeds,consuming all the anxiety, the stress, the overwhelm of this life. The secondbird is our immortal, infinite self, silently and serenely watching itall.’

Ishan added, ‘The universe within us. All people alreadypossess immortality within themselves — most are just unaware of it. I amsetting out to wake them from their slumber.’

Ishan belonged to a long line of yogis. He spent the first20 years of his life in an ashram. One day, his guru told him a parable:

Glass can either be a mirror or a window. ‘When you look ina mirror, you see only a reflection of yourself; when you look at a window, yousee through it to the beauty and infinity of the universe around you. A mirroris painted black on one side; a window is pure, unobscured. To change a mirrorinto glass, you must purify it, removing the paint.’

Ishan was initiated into the spiritual life as a child byhis father, Dr. Avdhoot Shivanand, the noted yogic guru in a monastery in thedeserts of Rajasthan, near the Aravalli mountains.

Interestingly, and with a sense of humour, Ishan said thatwhen people come to know he was a monk, they regarded him either as a healer oran oddity. Some people asked bizarre questions: Can you fly? Do you fartrainbows?

As he grew older, Ishan came to a realisation. ‘There areonly two kinds of people,’ he wrote. “The ones who have already realised thegod within, and the ones who have the potential to realise the god within.

One of the pivotal moments of his childhood occurred when aflood destroyed their ashram. Father and son moved to the suburb of Dwarka inNew Delhi. Dr. Avdhoot was building an ashram in a swamp. In this swamp, thelocals threw their garbage and defecated into it. It was near the airport. So,the roar of planes flying in and out was incessant. And because of railwaytracks nearby, trains thundered past all the time. Apart from all this, carhorns blared constantly. Children shouted. Couples fought and screamed at eachother. Ishan found it difficult to adjust after the tranquility of the ashramin Rajasthan.

This is how he described it: ‘Humans are a little likesponges. We assimilate the energies that are around us. I would witness peoplewho were angry, and, somehow, I would feel their anger, too.’

So, how to reclaim mental calmness? Ishan’s way was torecite mantras. He said that is the surest way to connect with divine energy.‘Mantras are the gateway to the supreme power,’ he wrote.

Incidentally, after every chapter, Ishan offered ameditation practice:

Here are a couple:

No. 1

Sit comfortably, relax your body, and focus on a memory ofgratitude.

Feel the positive thoughts and emotions of thatmemory.

Gently embrace and accept its energy, allowing it toflow into the past from the present.

No. 2

Sit comfortably, relax your body, and meditate on thesun.

Imagine the sun as a friend, embodying all the positivity,divinity, and strength you need.

Inhale for a count of three, feeling the sun’s light flowinto your head and through your entire body.

Exhale for a count of three, releasing everything from yourbody through your head and into the sun.

One, two, three — inhale deeply, three-two-one — exhalefully.

Repeat this cycle for ten minutes, keeping your breath asdeep as possible.

Ishan confirmed the problem with humanity is ego.

He wrote: ‘Ego does not allow us to see what is obvious. Inhis book, The Gift Of Fear, American security specialist Gavin de Beckerwrote: “Your intuition exists, in part, to help you stay safe — to recognisewhen something isn’t right and to guide you away from danger.” But the avidya,the ego, has a trick up its sleeve: it speaks so loudly that it drowns out theinner voice of your intuition.’

And because of the constant strictures from society, peopleignore their inner voice and follow the dictates of others.

Ishan learned to activate the prana, the life-force energythat animates all human beings, with the help of a teacher, Mashe, who was amaster of kalaripayattu.

As he grew up, Ishan came to a realisation about his lifejourney. He would help people to go from avidya to vidya, to move from lack ofknowledge to knowledge. ‘My job was to clean people’s minds,’ he wrote. ‘Oncethe mind was habitable, a person’s higher self could take over.’

Yet Ishan’s path has been unconventional. He has engageddeeply with the world even while he nurtured a rich inner life of meditation.He has deftly maintained a link between outer action and innerstillness.

So, he is married with a boy and a girl. In Washington, youcan see Ishan in a tuxedo; in Mauritius, he conducts his ‘Yoga for Immortals’mental wellness programme for athletes; In the Himalayas, you can see Ishanswimming in a lake; he prays at the Ram Mandir in Ayodhya; he travels theAtlantic Ocean by ship; and he meditates on a frozen lake near the ArcticCircle.

In one photo on Instagram, Ishan is on his knees with foldedpalms seeking blessings from enlightened master Mahant Swami Maharaj of theSwaminarayan Sanstha, the proponent of Sanathan Dharma, which has itsheadquarters in Ahmedabad.

Over his maroon monk dress, Ishan had put on a sleevelesswaist jacket, which showed his bulging biceps. The Mahant Swami Maharaj lookedat his muscles and said, “Ladka Balwan Che (the boy is strong).” All the swamispresent along with Ishan started laughing. Then a very senior swami said, “Astrong body and mind are needed for the work Ishan has chosen to do.”

The Mahant Swami Maharajji gazed at Ishan with compassion inhis eyes and said, “You will succeed. I bless you.”

One can see Ishan doing weightlifting, practicing targetshooting, hitting the bull’s-eye, and enjoying video games in a mall. With athick salt and pepper beard, and a ready smile, he gives the impression ofbeing in this world and not being in it as well. Apart from being a spiritualleader, he is an international public speaker and a performance enhancementcoach.

The yogi has earned a Doctorate of Philosophy in Humanitiesfrom the United Graduate College and Seminary International in Kampala,Uganda.

This book is a reminder of the spiritual life that many ofus are missing at this point. From early morning until late at night, weconstantly distract ourselves with Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, and YouTubevideos. And in this empty activity, we have forgotten there is a divine energywithin us.

This has also resulted in a grave psychological breakdownall over the world. People turn to drugs, alcohol, sex, power, fame, andfleeting relationships to fill the void within. But Ishan says, the simpleanswer but very difficult to implement is the path of meditation and innerawakening.

He says the only way is the way inward. As Lord Buddha andJesus Christ said thousands of years ago, ‘Know Thy Self.’ Through the book,you can get an idea of how to travel into the soul, and connect with theDivine.

It is a timeless path to reclaiming your life!

(Published in kitaab.org,Singapore)

July 2, 2025

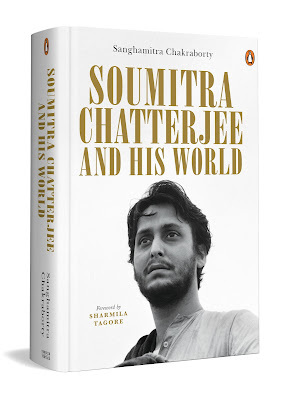

A Shining Star

Captions: Published by Penguin India; Author Sanghamitra Chakraborty; Soumitra Chatterjee as Apu; the memory card scene in Aranyer Din Ratri

Captions: Published by Penguin India; Author Sanghamitra Chakraborty; Soumitra Chatterjee as Apu; the memory card scene in Aranyer Din RatriIn this absorbing biography, Sanghamitra Chakraborty traces the life and career of Soumitra Chatterjee, one of Bengal’s greatest actors By Shevlin Sebastian Early in the book, ‘Soumitra Chatterjee and His World’, author Sanghamitra Chakraborty recounts a memory of the actor when he was six years old. One day, because he was sick, Soumitra could not go to school. His elder brother Sambit returned from school earlier than scheduled. Their mother, Ashalata, asked Sambit the reason why. Here is how Soumitra remembered that moment: “Rabindranath Tagore is dead, so our headmaster announced a holiday,” Dada said flatly. ‘When I heard this, I knew Tagore must be a great man. Why else would they announce a holiday? That was my only response then — I hadn’t matured enough to react to the tragedy, but I noticed that my mother’s world was shaken. Ma couldn’t keep standing — she held onto the railing and sat down slowly.’ Ashalata was an ardent admirer of Tagore. Like his mother, later in life, Soumitra worshipped Tagore as a sage, prophet, great artist and social reformer. An ardent bibliophile, Soumitra read Pather Panchali by Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay when he was a teenager. Later, he wrote, ‘I had no idea then that playing the role of the grown-up Apu [protagonist of Pather Panchali] would be the birth of my acting career.’During his studies at the CMS St. John’s School in Krishnanagar, Soumitra took part in plays and elocution contests. In Class Five, he played the prince in Sleeping Beauty.‘People in the audience gave away awards to young actors then,’ he wrote. ‘I was thrilled to receive medals at that age. Perhaps an obsession with acting later took hold of me thanks to those medals. Who knows?’But it was not always an idyllic life. He saw some tragedies first-hand. During the Bengal Famine of 1943, in which 30 lakh people died, Soumitra recalled the unbearable stench of dead bodies piling up on the streets in Krishnanagar. One day, a starving man took shelter in a courtyard next door. Soumitra used to take rotis from his dinner and give it to him. One night, he could not do so. He wrote, ‘Next morning, I found the man dead — a bag of bones covered in skin heaped in one corner. His misshapen metal bowl had a few morsels of food left in it.’ It would leave a permanent scar on his heart. As he grew up and got a job at All India Radio, he was always keen to embark on an acting career. His life changed when, one day, while recuperating at home from chicken pox, Satyajit Ray’s assistant Subir Hazra told him the maestro wanted to meet him. When Soumitra stepped into Ray’s house, the latter said, ‘There you are, please come in. But everything seems fine. I don’t see any marks on your face! Someone was saying you had developed pockmarks. This is nothing. It should be fine.’ The result: Soumitra was cast as the lead in Apur Sansar. Soumitra began preparing and remembered the advice given by theatre guru Sisir Bhaduri. As author Sanghamitra writes, as an actor he had to interrogate the script ‘like a detective’, read carefully between the lines, look for clues to recreate in his mind the unexpressed bits of the story or character and peel away the top layers to unearth what was beneath. Apur Sansar became a hit and launched the career of Soumitra. The New York Times critic Bosley Crowther wrote, ‘In the role of Apu, Soumitra Chatterjee is timid, tender, sad, serene, superb. He is the perfect extension of Apu as a man.’ Sanghamitra delves at length into the relationship between Soumitra and Satyajit Ray, which changed the young actor’s life completely. Ray’s son Sandip spoke about the ‘instant chemistry’ between his father and Soumitra. ‘Even before Baba spoke, Soumitra Kaku knew what he wanted,’ said Sandip. ‘You rarely see this kind of understanding between a director and an actor.’ Sanghamitra dwells at length on one of Ray’s greatest films, Charulata (1964) and the roles played by Soumitra and Madhabi Mukherjee. In the end, Soumitra and Ray worked in many films together, including Kapurush, Aranyer Din Ratri, and Asani Sanket. ‘The fun in working with him [Ray] was that he gave you immense freedom,’ said Soumitra. ‘And when you took the initiative, he would come up with a suggestion that would take it to the next level.’ The praise was mutual. Once Ray said, ‘Out of my 27 [28] films, he has acted the lead role in 14. This makes it obvious how much I trust him and how highly I regard him as an actor. I know I will depend on him until the last day of my life as an artist.’ Interestingly, in the famous memory card game scene in Aranyer Din Ratri, Ray placed the camera in the middle of the group that sat in a circle on a sheet on a ground in Palamau. The actors included Soumitra Chatterjee, Sharmila Tagore, Kaberi Bose, Subhendu Chatterjee, Samit Bhanja, and Robi Ghosh. As Sanghamitra writes, ‘Though his close-ups, with the roving camera, paused on each face, Ray superbly captured their mental landscape and the emerging group dynamics.’ Later, Sharmila said that it was so hot the shooting had to be completed within an hour. This tie-up of Soumitra with Ray lasted from 1959 to 1992, when Ray passed away on April 23, at the age of 70. What impressed Ray and the crew members was how meticulously Soumitra prepared for each shot. ‘He always arrived on time and came well prepared,’ said Sandip. ‘For example, he would make a note of the number of shirt buttons he had left unbuttoned from the last time [for continuity]. His discipline was remarkable.’ In the end, Chatterjee acted in over 300 films in a 60-year career. Sanghamitra also focuses on other films. It was interesting to note that in Teen Bhubaner Pare (1969), there was a song called Jibone Ki Pabona in which Soumitra did the twist in an elegant style. The YouTube video was a pleasure to watch and the catchy tune and the lively singing by Manna Dey felt dynamic and uplifting. It is a song that still sounds good. And there have been many covers of it over the years. This is an absorbing book. Undoubtedly, a lot of research has been done. Sanghamitra interviewed around 75 people, apart from family members. What was a blow to the author was the star’s unexpected death because of lung complications from Covid on November 15, 2020, at the age of 85. So Sanghamitra could not talk to the star, but his copious autobiographical writings provided a lot of information. This book is a valuable addition to the literature of film. For fans of Soumitra, this is a must-read. Actor Sharmila Tagore wrote in the foreword, ‘Soumitra had his reasons to avoid Bombay, of course, but Indian audiences are the poorer for it.’ So, for film lovers in other parts of India and the world who are not aware of this titan, this book will be a revelation. A shorter version was published in The Sunday Magazine, New Indian Express, South India and Delhi)

June 26, 2025

A photo with Guneet Monga

With the effervescent film producer Guneet Monga at the Dhanam Business Summit at Kochi. At age 21, Guneet went from Delhi to Mumbai to try her luck in films. In less than 20 years, she is an Oscar winning producer of 'The Elephant Whisperers'. She continues to have an ongoing stellar career. Please note the elephant symbol on her saree, made by a Malayali designer. Photo by Anoop Abraham

June 20, 2025

A Sardarji who speaks fluent Malayalam

Captions: Mohinder Singh; The outside of the restaurant; Maharaja's Chicken dish

Captions: Mohinder Singh; The outside of the restaurant; Maharaja's Chicken dishMohinder Singh, part-owner ofthe ‘Sethi Da Dhaba’, put out a reel in Malayalam celebrating the 10thanniversary of the restaurant. The reel went viral and brought focus to therestaurant and the family

By Shevlin Sebastian

To celebrate the 10thanniversary of his restaurant, ‘Sethi Da Dhaba’ in Kochi, Mohinder Singh putout a reel. In it, he tells the story, in Malayalam, about how the restaurantbegan and the type of food that is served.

Mohinder said that they don’tuse ajinomoto, colours, harmful chemicals, palm oil or groundnuts. “The foodshould be healthy, apart from being tasty,” he said, and added, “The mostpopular cuisine among Malayalis is Punjabi.”

To Mohinder’s surprise, thevideo went viral. It boosted the restaurant’s visibility and drew newcustomers. The biggest shock for viewers was to see a Punjabi speak Malayalamfluently.

Malayalis worldwide, from theUSA to Australia, called him and expressed their shock and admiration for hislinguistic skills. One man said, “It feels like a dream.”

Mohinder said his fluency inMalayalam happened by accident. As a child, he was mischievous. Many schoolsexpelled him because of his indiscipline. In the end, he landed up at St.Albert’s School. The students comprised local Malayalis, who were more fluentin the vernacular language than English. So Mohinder learned to speak Malayalamlike a native.

At the restaurant, Mohinderconfirmed that 90 percent of his customers are Malayalis. “We have earned thetrust of customers,” he said.

Mohinder paused and said, “Weare doing this as a tribute to our mother. We want to make her happy. Hence, weare determined to provide the highest quality of food. That way, we willreceive the blessings of our parents.”

The genesis of therestaurant

In 2013, Mohinder’s mother,Satwant Kaur, a foodie, almost lost her life because of a cardiac ailment. Whenshe recovered, she told her sons that she had a dream. They should start arestaurant in Kochi that serves authentic Punjabi dishes. Her husband was inthe automobile business. None of the four sons knew anything about therestaurant business.

On the morning of January 1,2014, Satwant told Mohinder she was feeling unwell and needed to go to thehospital.

Mohinder, who was celebratingNew Year’s Day, said, “Mother, there’s nothing to worry about. You arefine.”

That night, the 72-year-old diedof a heart attack in front of Mohinder. Guilt crushed him. He had been lookingafter his parents for 25 years. So, this lapse became unforgivable. Afterreflection, he decided he would try meditation or exercise. He adoptedweightlifting and did it for a few hours every day.

Every month he would go to HazurSahib, one of five takhts (religious centres in Sikhism. The shrine is locatedin Nanded, Maharashtra.

It took him five years toovercome his sorrow. “I have to thank my family for their steadfast support,”he said. “Weightlifting also helped me.”

During this time, Mohinder madea promise to himself. He would fulfill his mother’s dream.

On February 24, 2015, Mohinder,along with his brother Manjit, started the ‘Sethi Da Dhaba’ restaurant inKochi.

At that time, Punjabi cuisinewas not in the forefront of the cuisine palate of Malayalis. Many were scepticalabout whether the venture would be a success. Mohinder tried to increase theirchances by bringing cooks from North India. Initially, there was only a trickleof customers. But the brothers never gave up. Slowly, through word of mouth,the restaurant’s name spread. Today, ‘Sethi Da Dhaba’ is one of the leadingeating places for Punjabi cuisine in Kochi.

The Menu

On a bustling Monday afternoon,the restaurant boasted a crowd of varying ages. On one side sat a seniorcitizen, savouring a plate of chicken seekh kebab and crisp parathas. In themiddle were two career professionals, wearing ties and crisp white shirtssharing a meal. And on the other side, there was a middle-aged woman with twochildren in tow. Mohinder had a radiant smile, as he moved between the tables,chatting with the guests.

On the walls, there aretypewriters hanging, and paintings of farmers, trees and cows. A jeep bonnetand tyres sit in an enclosure, while an old radio with black knobs rests on aglass shelf. In one corner, one can see a green and white Bajaj Chetak scooter.Placed near the entrance is a photo of the Golden Temple.

“My brother Manjit has a passionfor collecting antiques,” said Mohinder.

The yellow ceiling lights cast acosy warmth, while the aroma of tandoor-cooked dishes set the taste buds inmotion.

In the reel, Mohinder spokeabout a new dish called Maharaja’s Chicken. This dish was served to MaharajaRanjit Singh (1780-1839) by his head chef, or khansama, Beliram. He wasregarded as the best cook of that era.

A few months ago, when Mohinderand his family went to Patiala, they met a fifth-generation descendant ofBeliram. They had a conversation and got the recipe for the dish.

The chef marinates and grillsthe chicken in the tandoor for 25 minutes. Then, he cooks it in oil with friedonions, curd, and gravy, along with ghee. The cooks prepare the dish as asemi-gravy. “We introduced this about a month ago,” said Mohinder. “It’s becomevery popular.”

One of their most popular itemsis the Patiala Lassi. They serve it in a one-litre glass. It comprises curd,cardamom powder, sugar, pieces of almonds and pistachios. The taste isexceptional.

Other items include ChickenMalai Tikka, Mutton Seekh Kabab, Amritsari Fish, Dal Makhana and assorted rotisand parathas.

Asked about the cooking methods,Mohinder said that they follow the traditional way. So when they make a dal,they keep the pulses in the tandoor (a large oven made of clay) the previousnight. They let it simmer, on a low flame, till the morning. For mutton, theyuse goat, not sheep, which is what most restaurants serve.

Asked the secret of goodcooking, Mohinder said, “Whatever you do, do it from the heart. Your intentionshould be pure. When you do things from the heart, you get blessings,appreciation, and peace of mind. The mind is always manipulative. In theservice sector, if you use only the mind, you cannot survive.”

Mohinder said their aim was thatwhen anybody came into the restaurant, they should leave with a smile.

The reviews on Trip Advisor havebeen good. Patron Varun Kodoth wrote: ‘Very delicious food. The food tastesawesome. We had Paneer Tikka Masala, Roti and Naan. Everything was perfect. Thestaff were truly helpful. Don’t forget to try the sweet Lassi.’

Nita A wrote: ‘Truly Punjabi.The taste, aroma, and ambience was complimented very well by Mohinderji who wasan excellent host.’

Many people wanted to take afranchisee, but the brothers are unsure whether the restaurateurs couldmaintain the Dhaba’s high standards.

“The problem with the restaurantsector is that people cut costs and end up compromising on quality,” saidMohinder.

While Manjit oversees thekitchen, Mohinder is the one who interacts with the customers. On average heinteracts with 5000 people every week.

Mohinder admitted thatconstantly coming into contact with the positive and negative energies ofpeople is difficult. “People’s facial expressions and behaviour reflect thetensions in their lives,” he said.

Every night, before he goes tosleep, he does heartfulness meditation. “In this meditation, I can cleanse myemotions and purify myself,” said Mohinder. “When your heart is pure, youattract positive energy.” Mohinder advises every entrepreneur to follow thespiritual path.

Asked about the mindset of theMalayali, Mohinder said, “Once you gain the trust of a Malayali, he will alwaysbelieve you. Sometimes, customers will tell me, ‘Sardarji, we are six people.You know how much quantity we will need. Bring what you like.’”

Mohinder ensures he brings alittle less, so all the food is eaten. “You should not take their trust forgranted,” he said.

Sometimes, there are humorousinteractions. One film director said that in the two Mollywood superhits,‘Punjabi House,’ and ‘Mallu Singh,’ Malayali actors played the role ofPunjabis. “They were ‘duplicate’ Sardarjis,” the director said. “Now we want toput an authentic Sardarji like you in a film when there is a Punjabicharacter.”

The director and Mohinder shareda laugh.

Thanks to their integrity andwholesomeness, today, the family has a sterling reputation. But this reputationwas first established by their father, Harbansji Singh Sethi.

Family Roots

Mohinder’s father, Harbansji, anIAS officer, was a senior officer of the Food Corporation of India atChandigarh. One day, in 1964, Pachakari Mohammed, a prominent iron dealer fromKochi, met Harbansji in his office. They developed a rapport. Mohammed invitedHarbansji to come to Kerala for a visit. In 1965, Harbansji took up the offerand came to Kochi. “My father liked Kerala a lot with its greenery and peacefulenvironment,” said Mohinder.

Kochi was also a burgeoning hubfor trade.

Harbansji had an itch to go intobusiness. His father had been an entrepreneur all his life. Mohammed encouragedHarbansji. He gave Harbansji an apartment for the family to stay. He took norent for the next two years. And he provided logistical and other support,too.

Harbansji took medical leave. Hestarted a business in automobile parts called ‘Bombay Auto Agency’. There was astruggle in the beginning, but soon it took off. So Harbansji quit the IAS.

The family comprised his wife,four sons, and a daughter.

In 2006, Harbansji diedat the age of 74. The shop is being run by the eldest son, Surinder. Theyoungest son Gurjeet is also running a spare parts shop.

As for Mohinder, he is marriedto Pawanjit Kaur, from Hyderabad. He has two sons, Sunny and Bunny. Sunny, 24,has settled in Toronto. Bunny is assisting his father in the restaurant.

All in all, it has been a good lifefor Mohinder. He is a man who deeply enjoys his work, and loves theinteractions with a wide variety of people.

At the‘Sethi Da Dhaba’, amidst the clatter of steel plates, Mohinder leaned forwardand gently placed his fingers on the glass frame of the Golden Templephoto.

“God hasbeen kind,” he said.

Box:

We areone

In manystates people are agitating that their language should become the primary one.Mohinder Singh said, “All languages are beautiful. We should respect them all.It reflects the cultural diversity of the country. And the more languages onelearns, the more enriched we become.”

He pausedand said, “Kerala is a beacon in this regard. The people respect our Punjabilanguage and culture. And vice versa. This is a state that welcomes all Indianswith an open heart and kind words. All states should be like this. In the end,we are Indians irrespective of whether we are Punjabi, Gujarati, Bengali,Malayali or Tamilian. I am the best example of this integration.”

(Published in Rediff.com) https://www.rediff.com/.../the-sardar-who.../20250620.htm

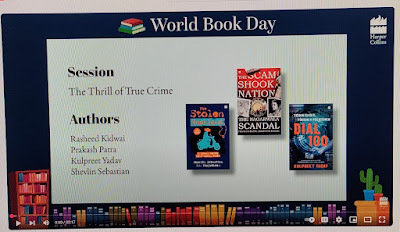

May 28, 2025

A session on true crime

Here is the YouTube Link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hlfux...

May 21, 2025

A write-up on my great grandfather, Ninan Xavier

By Shevlin Sebastian Last week, I had gone to pay condolences at the home of my cousin Thomas Job, who passed away at the age of 73 in Nadeckepadam, near Changanacherry. High up on the wall of the living room I saw a painting. This was of my great grandfather Ninan Xavier (1862-1948). The painting was done in 1926. Which meant, he was 64 years old. My late uncle Kurian Sebastian, who had a deep knowledge of family history, once wrote about Ninan. Here are some points from the article: Ninan was married to a woman called Achamma who belonged to Allapuzha. However, 22 days after she gave birth to a son, in 1887, she died. Thereafter, Ninan married a lady called Thresiamma. They had six children: one son and five daughters. Ninan loved agriculture. He was the first to plant rubber trees in Madappally village, 100 kms from Cochin. This became a financial success. The rubber was sent to the Swiss trading firm, Volkart Brothers in Cochin. Their Cochin branch was established in 1859. Ninan ordered bottles of Plymouth gin and cigars from Volkart Brothers. This was delivered by boat, which was the primary form of transportation in those times. Ninan was also the pioneer of sericulture (silkworm breeding). The Director of Agriculture made frequent visits to check on the crop. The Diwan also made a visit. Silkworm breeding became a success. Later, Ninan became a contractor and built several major roads in the district. No surprises then that he bought and owned a lot of land. In 1927, Ninan contested from the Changanacherry/Peerumade constituency. He won the election and became a member of the Sree Moolam Assembly. Ten years later, his son-in-law PJ Sebastian won from the same constituency. Kurian Sebastian mentioned that when traders would go at 4 am on bullock carts towards the market in Changanacherry, they would sing the praises of Ninan when they went past his house. Ninan died on January 25. My son was born on January 25. Is it coincidence or reincarnation? Who can say? Life is a mystery.

May 17, 2025

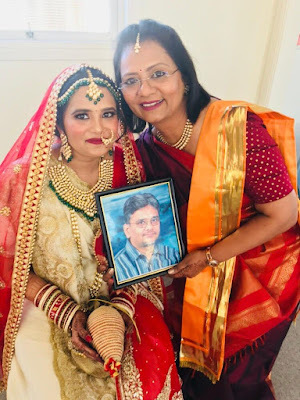

Meeta Shah’s Journey After the 2006 Mumbai Bombings

Photo: Meeta Shah (right) with EshaOn July 11, 2006, Meeta Shah’s husband, Tushit, 44, died in the Mumbai rail blasts.In Part 1, published in ‘The Hindustan Times’ on July 16, 2006, Meeta spoke about the immense loss that she felt, and described the chaotic hospital search for the body of her husband, and the gut-wrenching days that followed.

Here are the links:

https://www.linkedin.com/.../2006-bomb-blasts-railway...

In Part 2, she talks about the ensuing years. She describes how she struggled from deep despair to a place today where she has experienced gratitude, a measure of happiness and a spiritual awakening.

By Shevlin Sebastian

On July 11, 2006, seven bomb blasts devastated the suburban rail network in Mumbai. It resulted in 189 deaths and over 700 injured. According to the Mumbai Police, the terror outfit Lashkar-e-Taiba orchestrated it along with Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence.

One victim was Tushit Shah, 44.

As the city struggled to rebuild and heal, Tushit’s wife, Meeta, 44, struggled to come to terms with her own trauma.

Immediately after her husband’s death, Meeta realised she had to keep her emotions under control. That was because both her parents were heart patients.

“I was told not to cry in front of them to avoid further health complications,” she said in an interview a few days ago.

One day, Meeta heard Tushit’s voice saying, “Meeta, Meeta! Please accept it. I am not there. Please take care of Esha.”

So, Meeta placed Esha on her lap telling her, “Don’t worry dear, I am here. Nothing will happen.”

Esha’s nervous system would become stiff and freeze (pre-epileptic stiffness). This occurred a few times before they took Tushit’s body for cremation. Esha was 16 years old.

Meeta suffered from the guilt that she was not there when Tushit breathed his last. Nor did she attend the cremation. “I told myself that I had to take care of my little one now,” she said. “Esha clung to me the entire night and did not want to leave me for a moment as well.”

After two months, Esha started travelling on the trains again. She always carried her father’s mobile phones with her. Somehow, one by one, she lost them.

Meeta said, “Esha, Papa wants us to free him and move on, beta.”

But despite saying this, Meeta would always look out for him.

“Somehow, it took time for me to accept that he was not there,” she said. “So, from the bus I would look out for him in the crowd coming out of the station hoping to get a glimpse, or wait for the sound of his bike.”

There were no bike sounds. Instead, for the next ten years, till 2016, Meeta suffered from nightmares. There were times she would awaken in the middle of the night, gripped by grief, and taking quick breaths, as if she was asthmatic. Through it all, Meeta was always aware of Tushit’s energies around her, especially when she crossed the rail tracks to go over to the eastern part of the town.

Sometimes, Meeta received miraculous replies and answers.

Once, Esha and Meeta were returning from the bank after closing Tushit’s account.

It was raining.

Esha asked whether she could play the radio in the car.

“Yes, of course,” said Meeta.

While driving, Meeta lost herself in her thoughts.

She whispered, “Tushit, where are you? Please talk to me and tell me where you are.”

Suddenly, the song, ‘Mein yahan tu kahan...... zindagi hai kahan? (Where am I? Where are you? And where is the world?)’ sung by Bollywood superstar Amitabh Bachchan and playback singer Alka Yagnik came on the air.

Oh, Tushit replied, concluded Meeta. This is not a coincidence.

Meeta stopped the car by the side of the road, got out, took a deep breath, and tried to quieten her racing heart. People only die physically, she realised. They are alive in another dimension.

Esha said, through the car window, “Mama, should I change the station?”

Meeta said, “No need, dear. It’s Papa telling me something.”

For Meeta, the song was so meaningful, as she released the clutch and pressed the accelerator.

Suddenly, she remembered their nicknames for each other.

Tushit used to call Meeta her Rekha [Bollywood actress] because of her dark complexion. Meeta would call him Amitabh [Bachchan], as he was tall, with a similar French beard and hairstyle.

One month later, when Esha had left to attend classes at the Patkar Varde College in Goregaon, and her mother had returned to her home, Meeta was alone for the first time in her house.

That was when Meeta took her bolster pillow and placed it in the same place where Tushit was last laid in the house. “Cradling it, I cried my heart out,” said Meeta. “I released a lot of my pain that day. I had to do it as it was all stuck inside my mind, body and soul.”

Though that moment eased her pain, Meeta discovered as the days went by, nothing could fill the void in her heart.

She said, “I lost the best person in my life, the family breadwinner, my life support system, my finance manager, my positive half, my soulmate, my child’s father, my best non-judgemental and accepting counsellor, a smiling and helpful soul, and so much more!”

Reflecting on their 21-year marriage, Meeta remembered she would often ask Tushit why he agreed to marry her.

“I am dark,” she told him. “In matrimonial ads, families seek fair and lovely girls.”

He replied, “Meeta, I was looking for someone I could gel with and have the same mental wavelength. I was also looking for somebody who was honest and smart. I was not looking for a fair girl.”

Meeta said, “I am grateful to the Lord that Tushit said yes. And I had the most wonderful relationship with my husband.”

In 2009, Meeta got a job as a psychologist and counsellor at the Narsee Monjee Institute of Management Studies, Mumbai.

She worked there for 12 years.

By 2010, as she settled into her career, Meeta experienced a spiritual metamorphosis.

For a long time, she had been angry at the Universal Energy for taking Tushit away so suddenly.

“I believe in karma,” she said. “For every action, there will be a reaction. I know nature will respond to those who have killed innocent lives as it returns what you give to the universe.”

Drawing on her religious beliefs, Meeta said, “I often feel sadness for people filled with angst and hatred. They have not seen love. I pray the Almighty gives love to all. And I also accept that God took Tushit away for a reason, which I will never understand.”

Meeta tried to get married, but somehow it didn’t work out. “There is nobody to match Tushit,” she said.

Her parents took it in their stride.

Her husband’s uncle led a branch of the Vinoba Bhave ashram, a spiritual community dedicated to non-violence and service. So, it was no surprise when he offered support by drawing on his philosophy of empathy.

He told her, “If you decide not to be in a relationship, I will not ask why. We trust you. We are with you. However, don’t stop searching. It’s important to have a life partner.”

As for Esha, she got a degree in biotech from the DY Patil College School Of Biotechnology And Bioinformatics. Simultaneously, she completed her diploma in patent law. Thereafter, she started applying abroad for her master’s degree in cancer research.

She got admission to an esteemed Australian university on a full ‘live-in expense’ scholarship.

Today, Esha has a PhD in cancer cell and molecular biology. She is working on managing projects for clinical trials. And is happily married too.

“I have a son-in-law who takes great care of her, and me,” said Meeta. “What more can I ask for?”

Meeta’s journey from grief to gratitude will make Tushit happy. At 63, it has brought her to a place of inner calm and tranquility. And her turnaround will inspire many who have faced similar tragedies.

“Eventually, despite many attacks on our spirit, love always wins,” she said. “That’s what Tushit showed me with the way he led his life.”

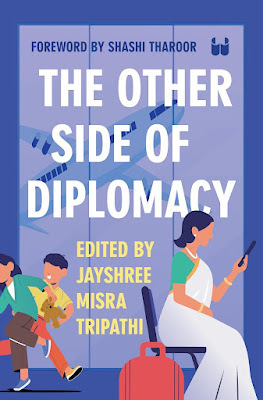

May 12, 2025

Spouses of diplomats talk about their experiences in different countries across the world

Captions: The cover; President John F Kennedy; Hope Cooke with her husband, the Chogyal, ruler of Sikkim

Captions: The cover; President John F Kennedy; Hope Cooke with her husband, the Chogyal, ruler of Sikkim

Delhi-based journalist Reshmi Ray Dasgupta wrote that when her mother Gayatri was posted to Berlin, she wanted to buy a cushion (kissen in German). But she inadvertently said, kussen (which means kissing). The shop assistant didn't waste a moment. He immediately landed a peck on her cheek, leaving Gayatri completely embarrassed. In Cape Town, Gayatri entered a shop with a group of people which included one white woman. The salesman said that he would only serve the white woman. The white woman was outraged and the group walked out of the shop. ‘It was Ma’s “Gandhi-ji at Pietermaritzburg” moment,’ wrote Reshmi. ‘She resolutely shunned everything South African until apartheid ended 34 years later.’Gayatri was in Washington when Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru made his third visit. At a White House gala, she was admiring the paintings on the wall when there was a tap on her shoulder. When she turned, a man said, “Hello, my name is John. What’s yours?” “Gayatri Ray,” was the reply. “Ray? You’re Bengali!” the man said. “How did you know I am Bengali?” she said. “Ray…like Satyajit Ray, right? So, you’re Bengali!” Apparently, a few months earlier John F Kennedy, the president of the United States, had watched Ray’s Apur Sansar. The ruler of Sikkim, Chogyal got married to an American woman, Hope Cooke (Sikkimese name: Gyalmo). As a result, the American festival Halloween was celebrated in Sikkim because of her influence. Sudhir Devare was the First Secretary of the Political Office. His wife Hema wrote that one night, as they settled in for the night, there was a loud thud at the door. The servant Tulsi opened the door. When Sudhir entered the drawing room, he saw a group of youths banging drums. Leading them was the Chogyal’s wife Gyalmo. Soon, Sudhir and Gyalmo started dancing. When Hema appeared in the drawing room, Gyalmo put Hema’s hand in her husband’s. ‘She left as suddenly as she had arrived, leaving both of us speechless,’ wrote Hema. ‘The next day the episode was the talk of the town.’ In 1980, Prem Budhwar was appointed as Ambassador of Ethiopia. His wife Kusum said that when they arrived, they received a shock when they discovered that the Ethiopian calendar consisted of 13 months. The 13th month consisted of five or six days in the leap year. The year began on September 12 and not on January 1. Prem told the foreign minister that when he was in college he had an Ethiopian classmate by the name of Tessima Ibido who came to study on a Government of India scholarship. To Prem’s shock, and happiness, the Foreign Minister said that Tessima had just retired as deputy finance minister. Kusum wrote, ‘Within a couple of days Tessima called and came over to our home. What a warm meeting it was between the friends! The clock stood still as they reminisced about the happy days of their youth spent together in Shimla.’ All these heart-warming anecdotes have been recounted in the book, The Other Side of Diplomacy, edited by Jayshree Misra Tripathi. The writing style is simple and clear. So, in effect it is an easy read. The stories are from the viewpoints of spouses of career diplomats who have served in Indian missions abroad. However, as former diplomat Shashi Tharoor mentioned in the foreword, in the Women in Diplomacy Index 2022, brought out by the Anwar Gargash Diplomatic Academy, UAE, India ranked 26 in a list of 40 countries and the European Union. ‘About 16.9 percent of the ambassadorial positions in the [Indian] missions have been held by women,’ wrote Tharoor. In this book of 16 essays, only two are by male spouses. Here’s hoping the gender imbalance will be corrected in future. The stories are from countries as varied as Tajikistan, Ethiopia, China, Brazil, Switzerland, Austria, Zimbabwe, Russia and the Korean Peninsula. While it may sound glamorous and exciting, in many places, the living conditions were rudimentary, and life was difficult. When Anuradha Muthukumar went to Tajikistan, in the 1990s, she was told by the members of the mission that the central heating system in most homes ‘had either broken down or lacked the fuel or energy to keep them going. Civil war had devastated the economy, rendering repair or maintenance of utility services nearly impossible. There was almost no public transport.’ And nearly all the women had to sacrifice their careers so that they could be with their spouses. Now, perhaps, with remote work, it may be possible to work, no matter where the posting is. The disruption to family life could be heart-breaking. Children have to adjust to a new education system, new language, and new classmates. And the process of adjustment can be traumatising. Once somebody said, to one of the daughters of spouse Anita Sapra, ‘All this moving around must have been exciting.’ She replied, ‘I will never put my children through what our parents subjected us to.’ While this remark hurt Anita, she understood the sentiments behind it. Shreedevi Nair Pal wrote that once the Head of the Chancery came up to her and told her the allowance for a national day reception would not cover professional caterers. ‘So, there we were, my cook and I, making monstrous amounts of kebabs, chicken tikkas and samosas for about five hundred people,’ wrote Shreedevi. She confirmed that spouses dealt with the ordinary people like the plumber, electrician and the baker, while their husbands, ‘mainly interacted with the social and political elite of the country they were posted in. And regardless of where they were posted, they never really had to step out of their comfort zone, as their work environment was more or less the same.’For the spouse, to be able to communicate when the language was a foreign one, can be difficult and stressful, too. Of course, there were compensations, too. You met the most brilliant and accomplished people of the country. You saw the stunning tourist sites. This was always an enriching experience for the family. And there were funny moments, too. Once, in Baghdad, Shreedevi presented a beautifully wrapped gift to her husband, Satyabrata, on his birthday. ‘I will never forget the look on his face and the laughter that followed when he opened his gift,’ she wrote. ‘It was a hammer; the only thing that was available at Orodibaag, the government shop. Suffice to say it is still in use.’ Asiya Hamid Rao, while in Vienna, got a few party tips from another spouse, Mrs Menon of the Indian diplomatic corps: a. Strike a balance between gravy and dry items. b. Ensure the dishes are of different colours: green, yellow, brown, white and multicoloured. c. Never lose sight of people’s religious sensitivities; hence, never serve food that is taboo for religious reasons. d. It’s a good idea to ask your guests beforehand about any dietary restrictions. When Anita Sapra was in Seoul, she took a taxi. When the driver came to know she was from India, he started singing a song from Haathi Mere Saathi. ‘What a rare sight to behold,’ she wrote. ‘Me in a taxi on the streets of Seoul singing a song in my own language. Later on, I learnt that Haathi Mere Saathi was a popular film in Korea in 1975. It was renamed Holy Elephant and many children thronged to watch it in theatres.’However, tension always remained as perennial background music. It rose a hundred fold when a Prime Minister or a President came visiting. The pressure that nothing should go wrong during the trip could take an emotional and psychological toll on both husband and wife. Or as Sharmila Kantha wrote, ‘I have accompanied first ladies during their state visits to India, sat through amateurish but enthusiastic community functions, stood for hours in heels to greet nearly a thousand guests at our national day receptions, attended numerous national day receptions of other countries, where I smiled inanely at people.’ Added Jayshree Misra Tripathi, ‘My heart used to beat a hundred times faster, as each Independence Day and Republic Day approached, hoping the chosen menu would suit everyone from back home – north south, east, west, northeast and northwest too – all fellow Indians. They always came first.’ The book gives us an insight into the difficult lives of spouses in foreign missions. There is an endless amount of adjustments to be done. With a busy husband, most of the time the wife has to tackle things on her own. She also has to handle the burden of the children’s stresses almost single-handedly as they try to adjust to life in a new country. What strikes the reader is the personal and job sacrifices these women have made, so that their husbands could have successful careers. In the end, they were heroines in their own way. (Published in kitaab.org, Singapore)