Shevlin Sebastian's Blog, page 5

February 12, 2025

People I don’t know

By Shevlin Sebastian

By Shevlin SebastianOn Sunday morning, I set out on a jog in a lane behind my house in Kochi. The lane is usually deserted. There are trees on either side. There are many houses with gardens in front. A large building is also there.

It is quiet enough that I can hear the cawing of crows and the chirping of sparrows. Of course, to listen to these sounds, I have to quieten the crashing sound of colliding thoughts in my head — happy moments, sad recollections, angry exclamations, revengeful desires, and nostalgic situations.

I often saw a thin man clad in a banian and a dhoti. He had grey hair and large eyes. He lived in a house in that lane. Sometimes, I smiled. He waved. Or he would say, “Good morning.” I would squeeze out some sound because I was breathing hard through my mouth. But we had no conversations at all. Neither did I know his name, nor did he know mine. It was a ‘Hi and bye’ acquaintance.

Then a couple of months ago, I realised he no longer came for his morning walk. What happened? Had he become ill? Has he been struck by a stroke and is bedridden? Is he suffering from dementia? Or has he passed away? Or a more comfortable thought: he might have gone for a long vacation.

Whatever the reason, I could knock on the door of his house and find out. But somehow, I haven’t. I am afraid to know the answer. And I prefer to remember him as I had seen him, with a pleasant smile and a gentle wave of the hand.

For many years, I would see a middle-aged man and woman go for a morning walk. He was tall and bespectacled. She reached his shoulders. But she always spoke animatedly, always moving her hands. And he listened with an occasional nod of his head. Then one day, he began walking alone…

One morning, someone put up a flex board on a pole announcing a death. A lady has passed away. She was 63. A group of women stand near it. One of them said, “Do you know who she is?”

And yes, one woman knows and explains.

When I look at the photo, I realise I don’t know her. Neither do I remember having ever seen her. Yet, she stayed nearby. This is city life. People live in their bubbles.

There have been other deaths in our lane.

A 60-year-old man, who had spent decades in the United Arab Emirates, returned. He was all set to spend the rest of his years with his wife and family.

But one morning he collapsed in the bathroom following a heart attack and passed away. As her husband lay on a mat on the floor, the devastated wife placed her head on the lap of her daughter. The son shed tears. Neighbours came and offered their condolences. Many who lived in the lane did not know them personally. But at this moment of tragedy, they felt the need to offer solace.

In a quiet lane, life-shattering events were taking place.

There is also silent suffering. A widow lives all alone. Children are away. Visitors are rare. Only the maid comes to cook and clean the floors. Her company is a TV set, and walls and windows.

Sometimes I run past a house where the owner has died. The children are abroad. The doors and windows are closed. That is the case with thousands of homes across Kerala. The Malayalis want to leave because of dismal job opportunities. And the people from other states, especially labour, want to come here because of good daily wages.

What a paradox!

On a recent morning, it is cloudy. A gentle breeze blew. I inhale deeply. I had reasons to be grateful for this fresh air. In Delhi, during Diwali, the Air Quality Index was 330, while in Kochi it was 60.

By this time, the dopamine has been released in my brain. My mood becomes lighter. I feel calmer.

And I am grateful to be alive.

(Published in rediff.com)

February 5, 2025

The India of Today and Yesterday

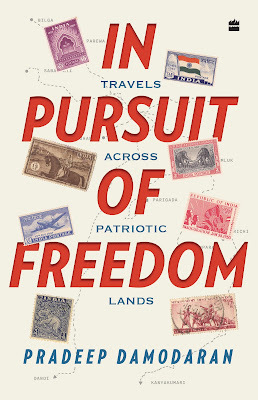

AuthorPradeep Damodaran travelled to many cities and towns associated with thefreedom movement. He wanted to get a feel of whether the history stillresonates. He also focused on the daily life of the people.

ByShevlin Sebastian

InFebruary 2022, author Pradeep Damodaran visited the Sabarmati Ashram inAhmedabad. Expectedly, there were plenty of visitors, ranging from the young tothe old. Pradeep checked out Hriday Kunj, the home of Mahatma Gandhi andKasturba, between 1918 and 1930. He also walked through the museums and photogalleries.

WhenPradeep perused the visitor’s book, he got a surprise.

Onevisitor wrote that Gandhi would rot in hell for what he did to all Indians.‘Even after 75 years of Independence, still we are crying, dying because ofyou, Mr. Gandhi. I realised why BABASAHEB B.R. AMBEDKAR did not call youMahatma. Because of you, more than one crore people died during partition. Onlysoldiers dead in Kashmir as of today’s count is 90,000!’ Pradeep added inbrackets: ‘No idea how he arrived at this figure.’

Whenhe pointed this out to Atul Pandya, director of the Sabarmati AshramPreservation and Memorial Trust, he said that this freedom to criticise Gandhiwas exactly what the man had fought for. ‘Let them try to openly criticisetoday’s leaders and see if they can get away with that,’ said Atul

Pradeepwent to Juhapura, the Muslim ghetto in Ahmedabad and the Gulbarg Society inChamanpura.

Thisis how he described what he saw at the Gulbarg Society where 69 people,including women and children, were hacked to death by rioters in 2002: ‘Aneerie silence engulfed us. The entire gated community was desolate andlifeless… At the entrance, to my right, were sprawling two-storey homes withspacious balconies, porticos with round pillars and tiled flooring completelyblanketed by dust, soot and scars of burnt human flesh and blood. Doors andwindows had been ripped off, probably stolen by anti-socials. Fans andfurniture in areas not destroyed by the fire were also missing. Spacious livingrooms and bedrooms were bereft of furniture; burnt clothes and glass pieces layscattered upon piles of other debris, mostly burntwood.’

Hemet Rafiq Qasim Mansoori, who was wearing sunglasses. Asked whether he had beenpresent during the massacre, Rafiq took off his sunglasses. His right eyelooked completely smashed. ‘A stone hit me in the eye,’ he said, by way ofexplanation about what happened to him during the attack. ‘I lost nineteenfamily members that day and that included my wife and infant son.’

InGodhra, Pradeep dwells on the long history of communalism in the town, whichwas a revelation. Muslims in Godhra belonged to the Ghanchis branch. They weremostly poor and uneducated.

DuringPartition, many Sindhis, belonging to the Bhaiband sect, migrated from Karachiand settled near Godhra. They had experienced horrendous suffering at the handsof the Muslims in 1947. That memory remained strong. The Hindu communaliststook advantage of this resentment.

Thefirst large-scale communal riot took place in 1948 between the Sindhis and theGhanchis. The Sindhis burned down over 3500 properties belonging to theGhanchis. They had to flee. The Sindhis took over the lands. ‘Even at thattime, arson was the top choice for rioters in this region,’ wrote Pradeep. Theriots between the two communities have continued intermittently over thedecades.

Atone time, Pradeep went to interview Maulana Iqbal Hussain Bokda, the principalof the Polan Bazar Urdu School. When the Maulana spoke about the socialisolation and economic backwardness of Muslims, Pradeep asked whether theMaulana had regretted not emigrating to Pakistan.

Adisturbed Bokda led Pradeep down a corridor and pointed, through a window, atthe tricolour flying high outside. ‘You see that tiranga? Since 2005, the flaghas been hoisted every day at 7 a.m. and is brought down at 5 p.m.,’ saidBokda. ‘You tell me if you can find this anywhere in India. The tiranga ishoisted every single day! If one person cannot do it, someone else does. Youknow why? It is because we are Indians and we believe in this country.’

Allthese stories are recounted in the book, ‘In Pursuit of Freedom — TravelsAcross Patriotic Lands’. Pradeep would go to a particular place, which had somelink with the freedom movement. There, he would describe his encounters withthe local people. Then he would delve into the history of the place, asconnected to the freedom movement.

So,in Bardoli, he talked about the Bardoli Satyagraha against the British byfarmers against high land taxes in 1928. Its success resonated across India.The concept of nonviolent resistance became an idea that nobody could resist.And it led to the independence of India, although it took another twodecades.

Inthe first section, Pradeep goes to different places in Gujarat. In Part 2, hegoes to Uttar Pradesh. His first stop is Jhansi. Pradeep wanted to find outwhether the residents still remembered Rani Lakshmibhai.

Andyes, she is very much alive through hoardings, government flex boards and namesof colleges and other institutions. He visited the Jhansi Fort and marvelled atits construction.

Whilein Jhansi, Pradeep had an unusual experience. People would often ask him whichreligion he belonged to. They would feel unnerved when Pradeep said he was anatheist.

Henoted that those who asked this question had ‘never moved out of their nativetowns and villages for generations. They had been fed stories about thegrandeur and courage associated with their religion. Merely seventy-five yearsof imposed secularism are, perhaps, hardly sufficient to erase over 1000 yearsof religious devotion, as I could see first-hand,’ writesPradeep.

InPala Pahadi village, Pradeep heard a familiar nationwide lament echoed by a villager:‘What is there to say? Can’t you see for yourself? Everything is rotting here;nothing has changed in the past seventy-five years. We have no roads, nodrinking water, nor any form of sanitation. Where are the free toilets? Whereare the schemes the government has announced? We have got nothing.’

InNandulan Khera, the people had converted over 90 percent of the Swachh Bharattoilets into storerooms for storing hay and other non-essential stuff. Theproblem with the toilets was that the government had not installed a septictank. And for the few who built septic tanks, once it got full, no lorriescould come to their village to get it emptied because of a lack of properroads. So the people stopped using the toilets and went back to the fields for theirablutions.

InUnnao, Pradeep went to the village of Mankhi, 17 kms away. He wanted to meetthe girl, whom ex-BJP MLA Kuldeep Singh Sengar raped on June 4, 2017, tonational outrage. Later, her father died in police custody. Pradeep discoveredthat because of the danger to their lives, the family no longer lived in thevillage. They had moved to Unnao.

Backin Unnao, Pradeep met the girl’s mother, Asha Singh, a Congress candidate forthe UP Assembly elections. She detailed the sequence of events that took place.Asha bemoaned the fact that men continued to rape women, especially of thelower castes, with impunity. All the publicity associated with her daughter’scase had changed nothing. The caste system remained powerfully rooted inpeople’s minds.

Standingnext to Asha was a young woman who looked confident and sophisticated. It wasmuch later that Pradeep came to know she was the victim. ‘She was definitelysmart; perhaps in a decade or so, she would be ready for the polls and Unnaomight then have a serious contender from the fairer sex,’ saidPradeep.

Someof the other places Pradeep visited included Chauri Chaura, Champaran, andMotihari.

Inthe third section, Pradeep goes to Punjab, where he focuses on the Ghadarmovement. These were expatriate Indians, mostly Punjabis, who fought tooverturn British rule in India. He also visited Don Parewa (Nainital), Tamluk(Bengal), Tentuligumma (Odisha), Panchalankurichi and Idinthakarai (Tamil Nadu)

Thisis an eye-opening book. It is a history lesson and a picture of modern-dayIndia. This history, told as truthfully as possible, is important especiallywhen there is a lot of rewriting and erasure taking place these days. Forexample, the National Council of Educational Research and Training has removedall chapters on the history of the Mughals and of Gandhi’s opposition to Hindunationalism.

Thebook shows that while progress has been made, in many areas, things have stayedthe same just as they were one hundred years ago. But the people fight on. Thereis a deep sense of frustration and anger at the government because of the lackof jobs for the young and for its failure to provide basic services. In theend, this book is an insightful addition to help us better understand the Indiaof today and yesterday.

(Ashorter version was published in the Sunday Magazine, The Hindustan Times)

February 1, 2025

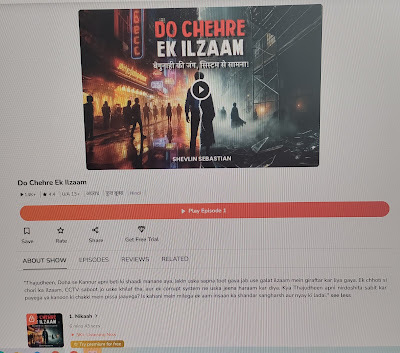

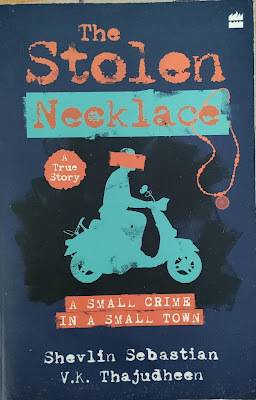

Hindi audio version of 'The Stolen Necklace' can be heard on Kuku FM

Happy to state that the Hindi audio version of 'The Stolen Necklace' titled 'Do Chehre Ek Ilzaam' can now be heard on Kuku FM. There are 33 chapters of a few minutes each. So far, over 14,000 people have tuned in. This is the link: https://kukufm.com/show/do-chehre-ek-ilzaam/episodesMany thanks to Kuku FM radio channel, HarperCollins Publishers and Anish Chandy, Founder of the Labyrinth Literary Agency

January 17, 2025

The Burnt House

ByShevlin Sebastian

At7 am, the day after the burial of his wife and two daughters, Nasir Khan stoodoutside his house. The tiled roof had caved in, while the walls had dark stainson them. The floor inside was a mess of ash, burnt wooden planks, sarees, andchildren’s clothing. There were several collapsed bricks in the middle of thedining room. An acrid smell permeated the house. He walked from room to room.Nasir saw the half-burnt bed on which he and his wife Ruksana slept.

Ithad taken so many years to build his dream house. Now it had taken a group ofyoung men less than an hour to reduce the house to a shell and destroy hisfamily. When the house caught fire, they became trapped inside.

Whenhe stepped out, he noticed his cycle had also been burnt. The tyres had meltedinto a gooey mass on the ground.

Animage came to his mind. Of his two daughters running up to him when he returnedwith packets of sweets. The sweet smiles and the affection in their eyes. ThenNasir blinked, as tears welled up and the image vanished. He continued to stareat the house. Other houses nearby were also in the same burnt condition. But hewas told the people had left much earlier. He was not sure why Ruksana did notgo away. Maybe she had been waiting for him. Or maybe she did not feel it wouldbe dangerous.

NasirKhan is 60 years old. The silver-haired man is a labour contractor. He had beenin Azamgarh on business the day when his life turned into darkness. Nasir knewit had all to do with the coming assembly elections. Polarisation was the bestway to get the votes of the majority community. Riots acted like a vacuumcleaner, to mop up the votes.

Somealtercation had taken place outside the mosque. Soon, armed men raided theirmohalla. They carried knives, country-made revolvers and cans of kerosene.Nasir’s house was near the mosque. It suffered the most damage.

Nasirsaw from the corner of his eyes that a young man was watching him. He had abeard and wore jeans and sneakers. ‘English fellow,’ thought Nasir. The youthapproached Nasir.

Hebowed his head and said in a low voice, “I am sorry for your loss.”

Nasir’slips curled in one corner. He was not sure whether the commiseration wasgenuine. ‘Who is this man?’ he thought. ‘Where does he come from?’

“Sir,I am a journalist from Lucknow,” the man said. “I write for an Englishnewspaper.”

WhenNasir remained silent, the man said, “I am Abbas.”

‘AMuslim journalist,’ thought Nasir. ‘Okay.’

Nasirnodded.

“Sir,what happened?” Abbas said.

Nasirexplained what had happened. Or rather, he recounted what he had heard. Abbastook down notes on a small notepad using a ballpoint pen.

AsNasir spoke, he could feel the constriction in his heart easing up. His throatseemed to open up. He spoke a bit more easily.

Abbasasked a steady stream of questions calmly. Nasir answered them as best as hecould. For years, he held a resentment against these privileged, well-educatedcity boys. Many of them were cocky. Sometimes, he felt like giving them a slapwhen he saw them misbehave on the streets. But he knew if he did something likethat, their parents, with their influential contacts, would ensure he wouldland up in jail. Then how would he feed his family? ‘Opt for safety,’ hethought. But now Abbas was changing his perceptions. There were good youngsterstoo. Well-behaved and polite.

AsAbbas paused in his questioning, Nasir said, “Why don’t we have a cup ofchai?”

“Sure,Nasir Bhai,” said Abbas.

Theywalked towards the road, crossed it, walked a hundred metres and came to RamuYadav’s roadside shop. The one-room shack had benches placed outside.

“Twochai,” said Nasir, as he and Abbas sat down beside each other on a bench.

Nasirclosed his eyes and rubbed his forehead with his thumb and forefinger.

“Iam so sorry about what had happened,” said Ramu.

Nasirnodded.

“Whatare you going to do now?” Abbas said in a low voice. “Will the governmentprovide compensation?”

“Theyshould, if they have any humanity,” he said, feeling a surge of anger whip throughhim. It seemed as if his breath had stopped.

Nasirobserved Abbas sideways. The journalist had blinked, taken aback by his suddenchange in tone.

“Itis going to be difficult to move on,” said Nasir, in a softer voice. “For whomshould I live now?”

Therewas a silence between them.

Ramubrought two earthen cups for them.

Atuft of smoke arose from the cups.

Theysipped the tea in silence.

Thesun arose in the sky.

Ina low voice, Nasir said, “Politicians will do anything to win votes.”

Abbasplaced the cup beside him on the bench and noted the sentence in hisdiary.

Somelabourers drifted to the shop to have tea, bread and bananas.

Nasirand Abbas finished their tea. They threw the cups into a bin nearby.

Abbaspulled out his purse from his hip pocket and paid the money.

Theduo stepped out onto the road.

Abbastook a few mobile shots of Nasir. Then he shook Nasir’s hand and said, “I willsend the report through WhatsApp when it gets published.”

Nasirgave a brief smile and said, “I cannot read English, but I will ask somebody totranslate for me.”

Theyagain shook hands. Abbas stood at the bus stop.

Nasirbegan to walk away, to his sister’s house two kilometres away. He was staying theretemporarily. Nasir would repair the house. And then maybe sell it and move offsomewhere else. Then he wouldn’t have to be reminded all the time about whathad happened. Nasir was surprised to feel a sense of relief in him. Abbas hadlistened without interrupting him. Thus, in a way, Nasir could unburdenhimself.

Buthe also knew life would never be the same. Overnight, he had become the solesurviving member of his family. Nasir looked down at the road and thought,‘Allah, why did this happen? What wrong did I do? Or my wife and daughters? Whyis it that nothing seemed to happen to the people who did this? Why does theinnocent suffer all the time?’

Ashe continued to walk, a visual appeared in his head. It was of the Yateemorphanage, which was a few kilometres away. Every month, Nasir would donatesome money.

Once,he had gone with his wife and children to meet the youngsters. Many people hadabandoned these children because of pregnancy out of wedlock. Some becameorphans because of riots. Someone had killed their parents. Nasir knew many ofthem had psychological scars. You could see it in the sadness of their eyes andtheir nervous gestures, like rubbing their face or touching the ears. Hisfamily was deeply affected by what they saw. “Consider how lucky you are,” hehad told his daughters, and they nodded their heads solemnly.

Now,they are dead. And a rage and anger coursed through Nasir’s body. He knew hehad to do something. Otherwise, hate would consume him. And so, Nasir decidedhe would become a volunteer at the orphanage. He was sure interacting with thechildren would enable him to fill the void in his heart. And he could have apurpose in his life. He felt the children would heal him. In turn, he couldalso heal them.

Andhopefully, one day, way off into the future, he would forgive the killers ofhis family. Misguided, silly youth with no independent thought processes. Justbeing exploited by callous politicians. These young men could end up in jail ifthe authorities didn’t defend them properly in court.

‘Yes,’he told himself. ‘Tomorrow I will go to the orphanage and see what I cando.’

Abbasgot a window seat on the bus. His thoughts also revolved around Nasir and theruined houses he saw. ‘Nothing makes sense,’ he thought. But Abbas was gladthat thanks to his job he could see what happened first hand.

Abbashad experienced none of the tragedies which Nasir was facing now. He belongedto an upper-middle-class family in Lucknow. His father was a successfulcriminal lawyer. His mother was a principal of a private college. He hadstudied at La Martiniere school in Lucknow and St Stephen’s College in Delhi.Abbas gravitated towards journalism because he enjoyed writing.

TwoMuslims from two different worlds met, consoled each other and went off indifferent directions. Probably they would never meet again.

(Published in Muse India)

January 6, 2025

It’s all about going green

Former banker Ajay Gopinath runs Grow Greens, a firm that sells multigreens. Ajay says that they are the one-stop answer for all vitamins

Former banker Ajay Gopinath runs Grow Greens, a firm that sells multigreens. Ajay says that they are the one-stop answer for all vitaminsBy Shevlin Sebastian

One day, in 2006, Ajay Gopinath went to a restaurant in Bengaluru for lunch. He ordered a paneer dish. When the waiter brought it, Ajay noticed that there were leaves sprinkled on it in the shape of a triangle.

Ajay had seen curry and coriander leaves used as garnish. He knew their taste. But he noticed these leaves looked different. When Ajay tasted it, he felt it was unique. He asked the chef about it and was told that these were mustard microgreens. The chef said somebody was delivering them to the restaurant. But he did not have any more information.

Ajay headed the credit cards and personal loans division at Citi Bank in Bengaluru. He had been a staffer for 14 years. Ajay loved his work, but there was one problem. It was a 24/7 job. He found he could devote very little time to the family.

One day, in 2007, he quit. “It was an impulsive decision,” he said, at his home in Kochi. “I also wanted to get out of my comfort zone.”

He returned to Kochi, where his family lived. He has two children, a boy and a girl. His wife is a lawyer. For the next five years, Ajay enjoyed his free time. He roamed around, met friends and went on holidays. Then in 2012, he began working for a dental implants firm and helped them in marketing the products. Ajay worked till 2016.

One morning, in 2017, when he awoke, an idea popped into his mind. What about doing a business involving microgreens? He met many chefs in Kochi. They told him they were getting their supplies from Bengaluru. But it was not available in the shops or in supermarkets.

In the beginning, Ajay grew microgreens for the use of his family. The tray is 2 ft. by 1 ft. Each tray produces 500 grams. His family could not consume it all. Since it is a perishable product, Ajay began distributing it to his friends, relatives and neighbours. “The taste was different but everybody, including my family, liked it,” said Ajay. Soon, his friends said that instead of giving free samples, he should start selling them.

It was only in December, 2020 that he started his company, Grow Greens. He increased the number of trays.

Ajay’s method of growing is to use the cocopeat. This is a natural, growing medium made from coconut husks. The cocopeat is used as a base. He places the seeds on it. Then the trays are closed for three days because you need darkness for the germination to take place. Then it is exposed to 20-watt white LED tube lights hanging above the trays, for 10-12 hours. You have to pour water once or twice a day. The temperature should be below 25 degrees centigrade while the humidity is below 60 percent.

Today, he has 60 trays in an 80 sq. ft. room. Ajay grows radish, mustard, yellow American, bok choy (Chinese), sunflower, kohlrabi and many others.

Ajay imports seeds from the United Kingdom, the US, Australia, Italy and Israel. “The prices range from Rs 600 per kg to Rs 1 lakh,” said Ajay. The seeds have a shelf life of between six and eight months. But Ajay uses them within three months. He uses around 25 varieties.

To get the right seeds within India, Ajay travelled to Delhi, Ranikhet, and Nainital. He also went to G. B. Pant University of Agriculture and Technology, Uttarakhand. There they nurture organic seeds. In these places, they do not use inorganic seeds, fertilisers or pesticides.

On the plus points of consuming microgreens, Ajay said, “It is good for the eyes and skin. There are health sites which state that it prevents Alzheimer’s disease and cancer. It restores the calcium deficiencies in the body and solves knee pain. There is an increased protein intake. Most people have low levels of sodium. This helps to reach the right levels. Microgreens have protein and magnesium. There are macro and micronutrients. What else do we need?”

Ajay tells a story.

Raghu Nair (name changed), was getting chemotherapy at the Aster Medicity Hospital in Kochi. The doctor told Raghu’s son Mahesh that his father needed to have a lot of protein. “It is better to have microgreens,” the doctor said.

So Mahesh came to Ajay Gopinath’s house. Ajay gave him sprouted green gram.

When Mahesh said the doctor told him to buy 100 grams of each variety, Ajay said that over 25 grams a day is not good. “You must be careful that your father’s body can absorb these proteins,” Ajay told Mahesh. “You can consume beetroot, bok choy and sunflower. Then it will be a complete protein food.”

Raghu consumed the greens for three months. Ajay felt vindicated that when the doctor checked the protein levels, it was off the charts. The doctor immediately told Mahesh not to buy any more microgreens for the next month. This was the only way to bring down the protein level.

“It was a confirmation of the tremendous benefits of microgreens,” said Ajay. The good news was that Raghu went into remission, so the doctors stopped his chemotherapy.

Microgreens cost between Rs 150 and Rs 250 per 100 grams. You should consume the greens within seven days. The best way is to eat it raw. Or you can add it to a salad.

However, those who are consuming blood thinning medicines should consult with a doctor before consuming microgreens. “When people are on blood thinners, their Vitamin K levels are regulated,” Ajay explained. “When you consume microgreens, it increases the Vitamin K.”

Patients can consume microgreens which have a paltry amount of Vitamin K, like beetroot.

Grow Greens deliver to individuals, shops, hotels, gyms, hospitals, supermarkets and schools. Ajay delivers 5-8 kgs a day.

And since the nurturing is inside the house, Ajay does not have to suffer the vagaries of climate change. “I can grow 365 days a year,” said Ajay.

Asked about the difference between being an entrepreneur and working for a bank, Ajay said, “The salary which I was getting I am paying its equivalent to my five-member staff.”

But for Ajay, it is not about profit and loss only. “When I started, it was a passion for me to see how the seeds were growing,” he said. “I also think that these are natural plants, and hence good for human beings. We can solve the malnutrition issue. So, there is a social commitment.”

Ajay says that when he observes the leaves, he gets a message from them. “If the water is less, or it needs more light, the leaves might droop,” he said. “And if we forget to switch off the light, the next morning the leaves will look tired. It is through experience I can spot this. It is a living organism and has emotions. When we play music, the leaves look happy.”

Ajay said that in many Malayalam movies and families over the centuries, the grandmother would talk to the Tulsi plant. To allay one’s scepticism, he suggested the book, ‘The Secret Life of Plants’ by Peter Tompkins and Christopher Bird. According to Wikipedia, the authors talk about the ability of plants to communicate with other creatures, including humans.

(Published in Good Food Movement website)

December 8, 2024

After the darkness comes the light

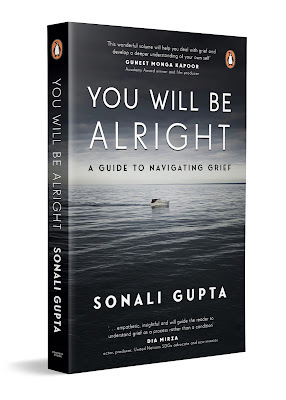

Psychotherapist Sonali Gupta’s book, ‘You Will Be All Right - A Guide to Navigating Grief,’ will help you understand what death does to you when a loved one passes away. It provides ways to cope with it.

Psychotherapist Sonali Gupta’s book, ‘You Will Be All Right - A Guide to Navigating Grief,’ will help you understand what death does to you when a loved one passes away. It provides ways to cope with it.By Shevlin Sebastian

Psychotherapist Sonali Gupta’s book, ‘You Will Be All Right — A Guide to Navigating Grief,’ begins with a quote by Elizabeth Gilbert, the bestselling author of ‘Eat, Pray Love,’: ‘It’s an honour to be in grief. It’s an honour to feel that much, to have loved that much.’

In the introduction, Sonali spoke about the intergenerational silence about death that exists in Indian families. And she gave an example.

Mayuri, 43, told Sonali, ‘This is the first time in years that I am crying while thinking about my mother’s death. I was six when my mother died in an accident. No one asked me how I felt or even tried to talk to me about what I was feeling. At home, there was sadness; yet my dad made it feel like life had to go on. I was not allowed to go to the funeral.’

Sonali begins the main section by clearing up some myths. For example, the belief that we only experience grief when we lose a loved one to death.

This was a fallacy. If you are not conceiving, you experience grief. The same is the case when a person is going through a separation or divorce, a break-up with a close friend, a miscarriage, infidelity, bankruptcy, and a loss of autonomy.

Here’s another myth that we all believe in: we will recover from grief and get over it as time passes.

But the author said that this is not true. ‘Unlike other emotions, which come and go, grief stays with us,’ she wrote. ‘It’s not a phase we get done with or move on from. David Kessler, an author and expert on grief, says that grief is not the flu, which we can recover from…. we learn to live with it.’

Grief causes many feelings to arise in you. A primary emotion is fear. How will life be now that the beloved has gone away?

Then there is anxiety. A patient Sujoy, who lost a brother, said, ‘I find myself worrying about everybody’s health. I’m constantly overthinking about my wife’s health. I’m anxious about my mum, who is fit and fine.’

Other feelings include anger, loneliness, isolation, emptiness, hopelessness and a longing for the loved one. But there is also relief, especially if the loved one is suffering from a long-standing illness or having mental issues like dementia or Alzheimer’s disease.

Alisha, a 35-year-old whose mother had dementia for four years, said, “We didn’t know how she was feeling. When she died, we all felt relief as she was in too much pain and there was nothing more we could have done. I love her and still think of her and miss her.”

Sonali wrote, ‘It is important to remember that relief and deep sorrow can co-exist.’

In most societies, there are rituals which help people to cope with death.

Mary Frances O’Connor, author of ‘The Grieving Brain: The Surprising Science of How We Love and Learn from Loss’, states that mourning rituals can offer constancy and comfort when everything can feel uncertain. ‘By connecting us to rituals that have existed for hundreds of years, we are reminded that those who came before us have experienced grief and uncertainty and they have carried on and restored meaningful lives.’

The book also delineates the physical reaction to grief. These include aches and pains, nausea, headaches, loss of libido, lack of appetite, weight gain or loss, insomnia or sleeping too much. There is also a psychosomatic reaction. A person has headaches, constipation, chest, back, body, or joint pains, breathing difficulties, or feeling feverish.

But what is a fact is that you will never recover from the death of a loved one. Dr. Elisabeth Kubler Ross, a Swiss American psychiatrist who wrote the bestselling book, ‘On Death and Dying’, said, ‘You will learn to live with it. You will heal and you will rebuild yourself around the loss you have suffered. You will be whole again, but you will never be the same. Nor should you be the same, nor would you want to.’

Elisabeth spoke about the five stages of loss: denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance.

There is another type of grief that everybody experiences, but nobody talks about it. This is called anticipatory grief. We imagine what will happen to us when a loved one, or a parent, dies even though the people are healthy at the moment.

It brings guilt to the people who experience it, so they keep quiet about it. But people experience this all the time. And there is nothing to be ashamed about. It comes about from a fear that there is limited time. And one day, inevitably, death will come calling.

Then there is disenfranchised grief. This is the grief that one experiences when a maid, watchman, a former teacher, or a pet dies. And the people around them cannot understand why their wife, father or friend is having this intense reaction to the death of an acquaintance.

It is a grief that is not publicly mourned or socially accepted. This grief can be socially isolating. Sonali went through something similar when a former client died. She did not know how to process the grief. A supervisor told her, “It’s okay if you haven't met the person for years, the bond remains. Allow yourself to grieve. Find a way to express what you are feeling.” So Sonali took to writing a journal and felt better after a few days.

Members of the LGBTQ community, who have not come out, have to suffer grief in private and in isolation when a partner dies. This also happens when you lose a pet. Except for pet lovers, the rest of society does not understand your grief. “Why feel sad? It’s just a dog. You can get another pet,” is the common refrain.

Other events which cause disenfranchised grief include celebrity deaths. When Hollywood star Robin Williams died of suicide, Sonali started crying. ‘He was my favourite actor, and I associated some of my fondest memories with his movies,’ she wrote.

Then people may experience delayed grief. This happens when a person dies by suicide, or drug or alcohol overdose. The spouse may be in shock for months. He or she cannot talk openly about what has happened. They may go through panic, anxiety, or fear attacks. It is only after a long period that they permit themselves to grieve about what has happened.

In the last section, the author wrote movingly about the culture of silence that surrounds people when a close relative has died. Once, Ravi, a 50-year-old whose wife died of cancer, entered his office canteen. He saw that all his teammates who were laughing suddenly became silent.

“I don’t know if they felt uncomfortable being happy around me because of what happened, or they felt pity for me,” he said. “But I had reached a place where I wanted to leave the organisation, as I was tired of these silences.”

Author Katherine May succinctly describes this feeling in her book, ‘Wintering: The Power of Rest and Retreat in Difficult Times’: ‘Wintering is a season in the cold. It is a fallow period in life when you are cut off from the world, feeling rejected, sidelined, blocked from progress, or cast into the role of an outsider. Perhaps it results from an illness; perhaps from a life event such as bereavement or the birth of a child; perhaps it comes from humiliation or failure.’ But all of us have to struggle through the darkness till we see the light again.

This is a book everyone should read, especially if you have encountered the death of a near one. You will understand with clarity the tumultuous emotions you are going through. And if you see somebody who is struggling to cope because of the death of a close relative, this is a good book to present to them. It will make them less lonely and realise what they are going through is what humanity has gone through for millennia and will continue to do so.

Whether we like it or not, accept it or not, death is an inescapable fact of life. We are born, we live, then we die. This happens to everybody and to all the people we love. There is no escape from this finality. But books like this are a soothing balm to apply to our pain and provide us with the motivation to live life again.

Or to paraphrase Sonali: ‘We have to learn to carry love and loss together.’

Published in kitaab.org

November 30, 2024

When a community dies

Photos: Queenie Hallegua at her home in Fort Kochi; David Hallegua with his mother; David and his sister Flory with Queenie; David with his wife Cici and daughter Eliana

Photos: Queenie Hallegua at her home in Fort Kochi; David Hallegua with his mother; David and his sister Flory with Queenie; David with his wife Cici and daughter Eliana On August 11, Queenie Hallegua passed away at 89. She was almost the last of the Sephardi (White Jews) in Fort Kochi after a 500-year presence. Her son David Hallegua reflected on his mother’s death and of his life growing up in Kerala

By Shevlin Sebastian

At 5.45 p.m. in Los Angeles on August 10, Eliana, 22, called her father David Hallegua and said, “Dad, I am in a panic. I don’t know what is wrong with me.”

About 14,900 kms away, in Fort Kochi, at 6.15 am on August 11, David was feeling groggy. He was suffering from jetlag after arriving from Los Angeles. At 3 am, he went to sleep in his parents’ house on Synagogue Lane. Even so, he told Eliana, “You have not had enough water to drink.” Eliana did that. Then she lay down and felt better.

As soon as David hung up, the housekeeper, Flory, came to his room and said, “I want you to check up on Mom.”

David immediately went to his mother’s bed, and even though her body was warm, Queenie, 89, was no longer breathing. David realised that at the moment Eliana felt anxiety and discomfort, her grandmother had passed away.

Queenie was almost the last of the Sephardi (White Jews) in Fort Kochi. Only her nephew Keith Hallegua, 65, a bachelor, remains. She was the wife of Samuel, a community leader and a prominent proprietor, who passed away in 2009.

Queenie’s funeral took place at the Gan Shalom Jewish cemetery. This is near the Paradesi Synagogue. David’s sister Fiona had flown down from New York.

“It was the end of that chapter of my life with her,” she said. “I felt relieved my mother was not in pain anymore.”

Asked about his mother’s last words, David said it happened on his previous visit in July. He had come home when Queenie had taken ill with congestive heart problems. As David was returning to the USA, he told his mother he was leaving. “She looked at me and smiled,” said David.

Then Flory told her, “Give your son a blessing.”

Queenie placed her palm on David’s head and said, “May you get everything that you desire in life. May God bless you!”

David feels sad that the community has died out. In the 1950s, there were about 2000 Jews in Fort Kochi and Mattancherry. But many emigrated to Israel when the country came into being in 1948. “A lot of Jewish customs and practices have disappeared,” he said.

David’s early life

David did his schooling at St. John De Britto’s Anglo-Indian High School at Fort Kochi. His best friend was Elvis D’Cruz. They sat on the same bench.

When David and Elvis were in Class 8, they realised that both their fathers were students of the same school. They studied in the same class.

After 30 years, Elvis and David met again in Kochi in 2023. Elvis lived in Dubai for many years and had moved to Fort Kochi. “It was so good to catch up with Elvis after so many years,” said David. “Elvis again came to see me when my mother passed away.”

After his Class 10, David did his pre-degree from Sacred Heart College in Thevara. Thereafter, he went to Trivandrum Medical College because he wanted to be a doctor. After completing his course, in 1988, he went to the USA for further medical studies. Today, David is a practising rheumatologist (the management of arthritis). His wife Cici is a chartered accountant while Eliana works at the Capitol Records music company.

Asked whether because he was a Jew, he felt different while growing up in Fort Kochi, David said, “My original identity was that of a South Indian. I speak Malayalam fluently. It was my first language. But in my daily life, I am Jewish.”

So David would not eat meat in a restaurant that was not kosher. But his friends, Christians, Hindus and Muslims understood and accepted it. In medical school, his friends would say, “We can’t go to that restaurant because there is nothing that David could eat there.”

David said that all his friends would come over during the Jewish festivals, like Rosh Hashanah and the Shabbat. He also had a joyous celebration for his bar mitzvah. This is a coming-of-age ceremony when a boy turns 13 and marks his transition to becoming an adult.

David celebrated the Onam festival in the house of his Hindu friends. He also enjoyed Christmas with his Christian friends and Id with the Muslims. Not to forget the Gujarati and Parsi festivals.

Asked how Fort Kochi has changed, over the decades, David said, “It has become a commercialised tourist hub.”

David lived on the lane that led to the Jewish synagogue. “By 10 am, nowadays, the lane is very crowded,” said David. “Thousands of tourists come every day.”

David remembered it as a quiet lane. “My sister and I would have impromptu games with other boys and girls,” said David. “It was boisterous and full of joy. The elders would get together and have a drink. Some drank liquor or soda, while others had soft drinks.”

The Jews would have guests like Hamsa, a Muslim lawyer, Babu Seth, a Gujarati lawyer, a Parsi gentleman named Sorabjee, and a Hindu by the name of Sundaram. “It was a melting pot in one person’s living room,” said David

On tables and chairs placed outside, the women, including Queenie, played a South American game called Canasta (a type of rummy). “It was very competitive,” said David with a smile.

When asked whether syncretism, after hundreds of years, is alive and thriving in Fort Kochi, David said, “Yes, everybody lives in harmony. They depend economically on each other. Nobody wants any trouble that will disturb the peace.”

(Published in rediff.com)

November 26, 2024

Some thoughts after my uncle passed away

Photos: Joseph Vadakel with his wife Rani, daughter Reena, son-in-law Monis and grandchildren Joseph and Rosina; the house in Muvattupuzha where my my mother and uncle grew up; interstellar space

Photos: Joseph Vadakel with his wife Rani, daughter Reena, son-in-law Monis and grandchildren Joseph and Rosina; the house in Muvattupuzha where my my mother and uncle grew up; interstellar space By Shevlin Sebastian

When my mother was a child, she and her younger brother Joseph (Babu) would go for morning mass at the Holy Magi church in Muvattupuzha. On the walk back home, a distance of about 800 metres, at some point, they would start sprinting. Each wanted to reach home before the other so they could read the newspaper first.

This was one of my mother’s most enduring memories. She would keep repeating this story over the decades, but she never told us who won, and we, self-absorbed children, forgot to ask. For my mother, the thrill was in the race.

My uncle Babu Vadakel was an advocate. He practised for decades in the Kerala High Court. Babu Uncle was known among his family members for having a sharp brain, a quick wit, and a charming smile. His eyes gave this message: ‘I know what you are up to. You cannot fool me.’

My cousin Joseph said, “During our younger days, we would be in awe of Babu Chettan. He had smart looks and a stylish dress sense. Babu Uncle had an exemplary skill of blowing the smoke out in circular rings one after the other.”

My conversations with Babu Uncle were interesting. I gained many insights.

Life went on. However, in the latter stages of his life, his health broke down.

On November 20, Babu Uncle passed away, aged 83, at his home in Kochi. He leaves behind his wife Rani, daughter Reena, son-in-law Monis, and grandchildren, Joseph and Rosina.

Of nine brothers and sisters, only my mother, now 87, and her youngest sibling, Anthony, 76, remain.

When cousins of my generation viewed Babu Uncle’s body, many had a shocked look on their faces. Some had a realisation that death was going to come to all of us. My uncle himself may have attended hundreds of funerals in his lifetime. Now it was his turn, just like it will be for us.

Each time a close relative dies, there is a blow to the heart, followed by heaviness. And sometimes a thought arises: what is the meaning of our lives? Where do we go in the universe?

Stereoscopic 3D filmmaker AK Saiber, my neighbour, has made a scintillating 90-minute 3D film for school students. It is about the solar system and the universe. The distances are all in lakhs of kilometres. The temperatures on some planets, like Neptune, are hundreds of degrees below freezing point. On Jupiter, there is a continuous storm every day and night of the year. It has been going on for centuries.

Saiber takes the viewer out of the solar system into interstellar space. Then the camera reverses and a voiceover states the Earth is too tiny to be seen from the outer limits of space.

And then you wonder where in this vast universe the souls go. Where is their resting place? Considering the long history of the earth, could there be millions of souls? Where is Babu Uncle now? Has he met his parents, siblings, friends, and acquaintances who were on the other side? Can he see us even though he is not in physical form? Is there divine energy? Can Babu Uncle see God finally? Many people who had suffered a temporary clinical death spoke about sensing other people and silently communicating with them.

When my uncle was in the last month of his life, he kept saying that he could see his parents and siblings. This happened to my father when he was nearing his death.

Hussain, 35, was the home nurse who looked after my father. He told me that in all the 24 deaths that he had overseen, in every instance, the parents and relatives had come in the final stages. It seemed they provided reassurance and to tell their loved ones not to be afraid. But none of Babu Uncle’s family members saw anything.

So, does this happen? Science has dismissed them as hallucinations.

There are many questions. However, we will not get any answers till we die and go to the other side.

All these thoughts swirled through my mind as I stared at my uncle lying in peace in the coffin.

November 23, 2024

Serving the most backward people

Silpa P, branch postmaster of Chindakki Post Office, and Ajith K,assistant branch postmaster, speak about their experiences serving the membersof the backward Irula, Muduga and Kurumba tribes. They live deep inside theSilent Valley Project Park in the Nilgiris

By Shevlin Sebastian

At noon on August 7, Ajith K, 25, an assistant branch postmasterwas returning on his bike after visiting a tribal colony in Anavayi. Thisvillage is 600 metres above sea level, inside the Silent Valley Project Park inthe Nilgiris. It is about 10 kms from the Chindakki post office where he works.Sitting behind him was Hari, 30, a teacher who had hitched a ride from thehamlet (Malayalam name: ooru).

The duo went down the sloping road. It was made of interlockingtiles, but covered at some sections by green moss. All of a sudden the bikeskidded. The next thing Ajith knew he had fallen off the bike, with Hariholding on to him. Ajith landed on his knees. When he rolled up his trousers,he saw that the skin had scraped off from the knees. Blood trickled down. Ajithfelt a throbbing pain in his legs. Somehow, they made the bike upright, androde back to Chindakki.

Ajith is now recuperating at a lodge. This is one of the hazardsthat Ajith faces when delivering letters to the members of the backward Irula,Muduga and Kurumba tribes. They live in Thadikundu,Murugala, Kadukumanna, Kinattukara, Chindakki, Veerannur, Thudukki and Galasi.In most of the places, there are no roads. So, Ajith has to walk to deliver themail.

While on his treks through the dense forests, there are always thedangers of animals. Elephants roam around apart from wild bison, tigers, bears,leopards and snakes. “A huge bear was sighted recently at Edavani,” said Ajith.“The photo appeared in the newspapers.”

In the Bhavani river, near the Chindakki post office, whenelephants come to drink water, forest officers burst crackers to make them moveaway from human habitation.

“Nowadays, elephants attack human beings,” said Ajith. Last year,when a Jeep was travelling at night, an elephant attacked it and the vehicletoppled over. A few passengers were injured. Luckily, a few moments later,another vehicle was coming from the other side. They flashed their headlights,shouted and clapped their hands. The elephant, taken aback, trundled awaybefore doing further damage.

On a bund on a river near the post office, one day, people saw adead tiger. It seemed to have hit a rock under the water and died of naturalcauses. At the back of the office, forest officers have regularly caught snakeslike cobra, rat snakes and vipers. The locals keep dogs as pets so that theycan bark and warn the people of the presence of snakes.

Ajith begins his day by collecting the mail bag from Mukkali, fourkilometres away, and then he comes to the Chindakki post office to sort out themail. Then he sets out by 11.30 a.m. By the time he finishes all hisdeliveries, about 35-50 letters, on an average, it is about 4.30 p.m. But he isphysically tired. Then he goes to his lodge, on his bike to nearby Kaikundi.

The Chindakki post office has only two employees. Apart fromAjith, there is Silpa P, 26, the branch postmaster. Like Ajith, she is vibrantand energetic.

Silpa’s working hours are from 8.30 to 12.30 p.m. She deals withmoney orders, registered and ordinary letters. Mostly, there are letters fromthe bank which consist of ATM cards. Then the Centre sends Aadhar cards, butthey come in bulk. There are bank notices for those who have lapsed in theirpayments of loans as well as job interview calls and letters from collegesregarding admission.

“The main problem is that even though the letters are less, ascompared to other post offices, the delivery is a big problem,” said Silpa.“Usually, we could have called them on their mobile phones. But in the higherranges, there is no mobile connectivity. There is no range, even 500 metres fromour post office.”

Apart from that, the seniors speak in the tribal language, whichis similar to Tamil rather than Malayalam. So Silpa has a problem communicatingwith them.

Most of the tribals come to the post office in a jeep which hasother passengers. So Silpa will call one or two passengers who can understandthe tribal language and know how to speak in Malayalam too. “That is how I havebeen able to communicate with them,” said Silpa.

As for the elders, many of them do not know how to read or write.But now, the younger generation has had access to education. Quite a few havegovernment jobs. “There are three government schools in the area,” said Ajith.“Most of the children of tribals attend the classes apart from outsiders, too.Their lives are improving.”

The tribals are mostly farmers. They grow millets, pepper, coffeeand cardamom. At other times, they go to the forests to collect honey. Nearlyall of them live in brick houses. These have been constructed by thegovernment. “The houses in Anavayi are very clean,” said Ajith. “But in someplaces, it is not so well-maintained.”

Asked about their diet, Ajith says that it consists of rice,roots, tubers, greens, herbs, and fish, which they get from the nearby Bhavaniriver. “Fish is a major component in their diet, along with seasonal fruits,”said Silpa.

Mukkali is the place where the tribals go to buyprovisions.

On most days, anywhere between 10-12 people come to the postoffice to collect their wages or draw money from their savings account in theIndian Post Payment Bank.

Even though Silpa is supposed to close the post office at 12.30pm, many tribals, because they come from far distances, land up at 12.15 pm.“Since they come from far away, I cannot close the office,” she said. “It wouldbe cruel.”

For some it is difficult to make the trek. Those who live in theGalasi colony, which is way up in the mountains, have to travel 19 kms. First,they have to walk nine kilometres through the forest. Then only they can get ajeep to travel the rest of the distance.

Asked about the weather, Silpa said that most of the time it iscold. “On most mornings, there is mist,” said Silpa. “When it rains it becomescold. I wear pullovers most of the time. In December, I wear socks all thetime. At night, I use blankets.”

On days when the road is blocked because of a fallen tree, Silpawalks the distance.

She said the rainy season is the most difficult to tackle. Becauseof bad roads, once she fell from the Scooty on her way to work. Thankfully, aJeep came after a few minutes. The driver got down and helped Silpa to put theScooty back on its wheels. And she has to tackle a few hairpin bends also indriving rain. The best season is between December and January. “There are somany flowers,” said Silpa. “It looks so beautiful. It is like being inParadise.”

Silpa shares a flat with a postwoman Midula who works in Kalkandi,a couple of kilometres from Mukkali. They do the cooking together.

She has completed over a year at the post office.

“I have enjoyed my stint so far,” said Silpa, who had worked in apost office in the town of Kalluvazhi in Palakkad district.

Asked the difference between townsfolk and the tribals, Silpa saidthat in the cities, people are shrewd, cunning and cynical. But the tribals areinitially fearful of strangers. “But once you gain their trust they will opentheir hearts to you,” she said. “They will trust you implicitly. And they willaccept and join all the government schemes that I tell them about.”

(An edited version was published in The Sunday Magazine, The NewIndian Express, South India and Delhi)

November 22, 2024

Smile and win the race of life

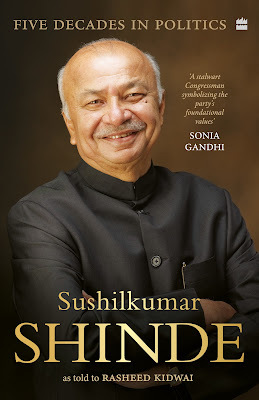

Former Maharashtra Chief Minister Sushilkumar Shinde, a Dalit, with the help of journalist Rasheed Kidwai, recounts his extraordinary life

Former Maharashtra Chief Minister Sushilkumar Shinde, a Dalit, with the help of journalist Rasheed Kidwai, recounts his extraordinary life By Shevlin Sebastian

Sushilkumar Shinde belonged to the Dhor caste. This is one of India’s lowest castes. Their traditional work was to cure the skin of dead cattle. This was used to make leather goods. His ancestors lived in the Osmanabad district of Marathwada. But his grandfather migrated to Solapur to better his economic prospects. He made leather bags and became affluent following the setting up of a business.

Shinde’s father, Sambhajirao, continued with the business and also did well. Interestingly, Sambhajirao married three times in his desire to have a son. Finally, the third wife, Krishnabai, asked Sambhajirao to marry her younger sister Sakhubai. The first three children died in early birth. But on September 4, 1941, Sushilkumar was born.

But tragedy struck the family when Sushilkumar’s father died on July 15, 1947.

This is how Shinde described what happened. ‘My father died, leaving behind a family unused to the ways of the world. Friends vanished, the business collapsed, and a day came when there was no one to support my mother and stepmother. Used to affluence and material comforts, my family turned poor overnight. Relatives and acquaintances offered their sympathies, but no one offered a helping hand.”

As for Shinde, his life took another direction. He became a thief. With a group of friends, they stole stuff from pavement dwellers. ‘Eating sweets and watching movies with the ill-gotten money was our favourite pastime,’ wrote Shinde.

Of course, one day he got caught. His mother urged him to give up this life, albeit with a slap. And Shinde did. He did odd jobs, like being a roadside vendor, working in a toffee factory, a printing press, and at the Wadia Hospital in Solapur.

All this is recounted in the book, ‘Sushilkumar Shinde – Five Decades in Politics’, as told to journalist Rasheed Kidwai.

As Shinde grew older, as a Dalit, he experienced caste discrimination. Once when he asked for water from a man, the latter asked about his caste. ‘His demeanour shifted upon hearing my answer,’ wrote Shinde. ‘He offered me water in an aluminium utensil, tilting it towards me from an angle so my lips wouldn’t touch the container.’ That night, Shinde wept and wondered how people could allow pets to wander everywhere in their houses, but not human beings.

On another occasion, he visited his cousin in Dhotri, ten miles from Solapur. Because it was so hot, he took a dip in the local pond. After he reached the house, people came and protested that a Dalit had defiled the pond. After heated arguments, a priest was called to purify it. ‘I emerged physically unscathed, but the experience left a permanent scar on my psyche about the obnoxious caste system,’ wrote Shinde.

It was only at the age of 20 that Shinde passed his Class 10 exams. Eventually, he got an arts degree (honours) from Dayanand College, Solapur, and an LLB from ILS Law College and New Law College, of the University of Bombay.

A friend, Subhash Vilekar, submitted an application form on behalf of Shinde for the job of a sub-inspector in the Mumbai Police. And to Shinde’s surprise, he got the job. Later, while doing police work, Shinde met a young and rising politician Sharad Pawar who persuaded him to join politics. So Shinde resigned from the police and went into active politics. Thereafter, Shinde tells the story of how step-by-step, through hard work, and having a pleasant personality, he ascended to top positions in the government.

Near the top of the heap

Sushilkumar Shinde regarded July 31, 2012, as a red-letter day. That was the day when Sonia Gandhi, chairperson of the United Progressive Alliance, told him, “You have to take charge of the home ministry.”

Shinde immediately realised that her decision was a testament to the opportunities the country provides to people from humble backgrounds. ‘Having started my career as a police sub-inspector many years earlier, my appointment as the home minister of the country was a fitting tribute to our vibrant democracy,’ wrote Shinde.

He describes the various crises that he dealt with. These included the hanging of convicts Afzal Guru and Ajmal Kasab. And he was the first to articulate about ‘saffron terror’. He met Kashmiri leaders, as well as those agitating for Gorkhaland in Bengal, and talked to Maoists without preconditions.

Shinde quoted a statement by former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh because it summarised the role of a Home Minister perfectly. “India is unique and a land of contradictions,” said Singh. “These contradictions often interact and give rise to factors that contribute to internal security problems. What are these problems?”

Singh mentioned poverty, unemployment, inequitable growth, resource distribution, corruption, the nexus between criminals, police and politicians in organised crime, lack of development, prolonged judicial process, poor conviction rates, caste, communal discord and hostile neighbours. “The order is random and each of these issues can have an impact on the country,” said Singh.

Shinde said that the government had strengthened the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Amendment Act in 2012. However, he added, “I feel sad to see how it has been misused to curb civil rights and legitimate political dissent. That was never our intention.”

Shinde spoke about another red letter day in his career. On January 18, 2003, he became Maharashtra’s first Dalit chief minister. The Congress was in an alliance with Sharad Pawar’s Nationalist Congress party.

Just before Shinde took his oath, he saw India’s first Dalit Head of State, KR Narayanan, sitting in the front row. ‘Words cannot describe what I felt,’ wrote Shinde.

And in his first Budget, Shinde came up with a novel idea: to provide financial help to bright students from socially and economically poor backgrounds so they could study abroad. In the first year, six boys and four girls went abroad.

Shinde also focused on how, when the Assembly elections in Maharashtra in 2004 resulted in a fractured mandate, the Congress Party decided to promote a Maratha leader to the post of chief minister. Thus, Vilasrao Deshmukh became the chief minister. As a result, Shinde lost his job. But Shinde mentioned that he and Deshmukh had been close friends for a long time. So, he did not get upset or humiliated.

Subsequently, Shinde became the governor of Andhra Pradesh. And he has made a telling observation about governors today. “I feel that the Office of the Governor should never be politicised,” he said. “Unfortunately, this is very much the trend now, and this is harmful to our polity. The only solution for this is that all governors should try to stick to what the Constitution says, and maintain their freedom from party influences as the Constitution expects them to.”

In a section called ‘Mentors and Leaders’, Shinde spoke about how Nationalist Congress Party founder Sharad Pawar played a decisive role in his career, especially in the early years. ‘I am indebted to him in more ways than I can ever acknowledge,’ wrote Shinde. He also wrote about his admiration for former Chief Minister YB Chavan. Other leading politicians Shinde wrote about briefly include Bal Thackeray, Vasantdada Patil, VP Naik, V N Gadgil and AR Antulay. And there is a brief chapter on his relations with former Congress Party President Sonia Gandhi.

There is a smooth flow in the narrative. It’s an easy read.

In the chapters of his government career, Shinde has skimmed over the details, probably, for reasons of national security. But the refreshing aspect is that Shinde does not indulge in scoring political points or attacking people. It is a book without malice towards anybody.

Asked about why he is inoffensive, Shinde wrote, ‘A leader must combine a soft tongue and be tough at the same time, without hurting anyone. That is an approach I have always taken, and it has seldom let me down.’

In the foreword, Sharad Pawar wrote, ‘Sushilkumar Shinde embodies Lord Krishna’s mantra on how to address a challenging circumstance: ‘He who responds to every situation with a smile and never reacts with anger is the one who wins.”’

Now and then, Shinde gives us points of philosophy that can hold us in good stead as we tackle the setbacks in our lives.

Shinde quoted the late English singer Amy Winehouse (1983-2011). “Life is short,” she said. “Anything could happen and it usually does, so there is no point in sitting around and thinking about all the ifs, and buts.”

Here is another one. ‘I decided not to bear grudges against anyone,’ Shinde wrote. ‘Rather than wasting time and energy on negative thinking, I felt that I should make the best use of the situation.’

After reading the book, you realise you can go from the bottom to the top, provided you have will, determination and a positive attitude. Of course, you should be lucky enough to meet the right people at the right time. But that happens in almost everybody’s life. The point is how many take advantage of these breaks. Shinde did. And as a result, his life is a success story.

(Published in scroll.in)