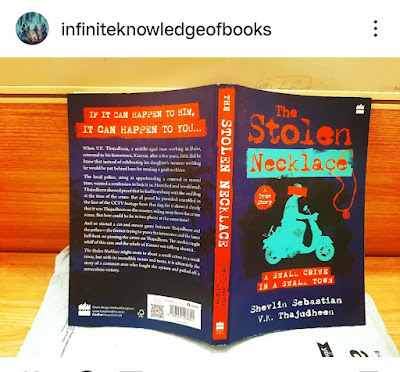

Shevlin Sebastian's Blog, page 4

May 2, 2025

Going Dutch

Sarah Lisa, from Holland, runs the Zera Noya bakery in Kochi. She talks about the reasons behind its success By Shevlin Sebastian On a Monday afternoon, the rain is pelting down. Outside the Zera Noya bakery in Kochi, in a cemented courtyard, a two-and-a-half-year-old girl is playing in the rain. She lets out a shriek of joy as she looks at her mother, Sarah Lisa, 32, who is sitting at a glass-topped table and working on a laptop. Her mother smiles to see the joy on her daughter’s face. To a visitor, she said, “Many people are shocked that I have allowed Adayah to play in the rain.”Sarah has been running the bakery for the past one-and-a-half years. Zera is a Hebrew word, which means seeds sprouting. This indicated a new beginning, while Noya means beautiful in Hebrew. The word can be connected to Naya in Hindi, which also means new. “I like the Hebrew language, and hence I chose these words,” said Sarah. Initially, because of Covid, she was baking from home and selling to customers. The physical bakery began on February 14, 2023, on Valentine’s Day.The items that can be found in Zera Noya include Bokkenpootje (Goat’s Feet), so named because the pastry looks like a goat’s feet. It is a meringue with apricot buttercream dipped in chocolate and almonds. Then there are stroopwafels, which is a caramel waffle and famous all over the world. You can also have the Strawberry Slof. This contains almond paste, vanilla buttercream and strawberries. The Marzipan Mergpijp is a cake with a layer of cream and strawberry jam, while the boterkoek comprises a butter cake with almonds. Speculaas is a type of biscuit. Other items include caramel tarts, muffins, truffles, apple pie and tarts, rondo, cupcakes, cinnamon braids and brownies. They also make freshly baked bread, as well as savouries like sausage rolls and chicken puffs. Sarah said that the most popular item is the Strawberry Slof. Asked why, she said. “It is the combination of the cookie, which is nutty and has fudge, sweet but not too sweet, and there is buttercream on top. But the cream is not so sweet, and there are fresh strawberries. It has a nice balance.” Asked about the composition of her customers, Sarah said, “There are all kinds of people, from different backgrounds and ages.” The prices range from Rs 30 and can go all the way to Rs 400. “Some items are expensive because we use authentic Belgian chocolate, French butter and German cream. The croissants, dipped in chocolate and cream, are at the higher end.” Asked about the difference with Kerala bakery items, Sarah said, “Bakers in Kochi use margarine and poor quality vegetable oil. But I use butter only. It is creamy and pricey too. And I always buy Callebaut Chocolate from Belgium, which is one of the best premium chocolates in the world. In Kochi, they use compound chocolate.” Compound chocolate is a mix of cocoa powder and vegetable fat.The store is open from 10 am to 10 pm. The bakery is doing well. Denise Anne from Nairobi wrote on Trip Advisor: ‘This is a great bakery filled with tasty treats and a warm and welcoming staff. The coffee is delicious and so are the baked goods.’Adds customer Lijo Joseph: ‘Classic and authentic.’ Sarah has a staff of 19 people who work in shifts. The Love Story Sarah Lisa met Vibin Varghese for the first time in July, 2013. This was in Hongkong. They were sailing on the ship, ‘Logos Hope’, and were on their way to the Philippines. While Sarah worked as a chief baker on the ship, Vibin, a marine engineer, worked in the engine room. Both were volunteers on the ship, which is regarded as the world’s largest floating book fair. Over 10 lakh people from all over the world access the ships every year. Sarah liked Vibin when she saw him for the first time while they were coming from opposite ends of a corridor of the ship. But she felt too shy to approach him although both said, “good morning” to each other. “Vibin had a charming smile,” said Sarah. “He worked hard and also had many friends.” They became Instagram friends. When the MV Logos ship was being dry docked in Hongkong, Sarah flew to China. While there, she met some people who needed help to set up a bakery. And that was how she ended up in Kangding on the China-Tibet border. It is 2000 kms from the capital, Beijing. She stayed for a brief while. But over the years, she kept going back. In 2017, when she was in Kangding, she began chatting with Vibin on Instagram. Vibin was on a ship that had docked in Mexico. “He felt excited to connect with me,” said Sarah.Sometime later, Vibin went to Kangding. After spending five days with Sarah, Vibin said, “I love you. I want to marry you.” Sarah also felt a connection to Vibin. The couple got married in Bangalore on May 5, 2018. Vibin grew up in Dubai but he chose Bangalore as the venue for his wedding because he is close to a pastor based there. Soon after the wedding, they came to Kochi, where Vibin’s parents had an apartment and settled down. Both had stopped their careers and were thinking of forging a fresh path. “Vibin gave up his career because he did not want to be away from me for nine months at a time,” said Sarah.It was in March, 2023, that Vibin got sick. In April, doctors diagnosed him with Stage 4 Linitis Plastica, a rare form of gastric cancer. Unfortunately, on December 21, 2023, Vibin, 36, passed away. When asked whether she planned to settle down in Kochi or return to Holland, Sarah said, “Many people thought that when Vibin passed away, I would go back. But at this moment, I can’t. I feel very settled here. I have imagined what it would be like if I closed down the bakery and went back. Where would I go? But then I realised Kochi is home.” Sarah was born in Den Helder, which is 84 kms from Amsterdam. The country’s main naval base is located there. Adhaya knows how to speak in Dutch, and is learning Malayalam and English. When asked to compare the character of Malayalis with the Dutch people, Sarah said, “The people in the Netherlands are direct and honest. They are private and less curious. Many aunties in Kochi ask me nosey questions. This is fine. I have got used to it. I am embracing it.” Nobody says hi or good morning when they see each other, even if they are strangers. Sarah said that in Holland everybody greets each other. “Malayalis are very reserved people,” she said. “In Kerala, dining rooms are always closed. You don’t want other people to see you eat. But in Holland, the dining rooms have large windows that open out to the street. The curtains are parted. A passer-by can wave to you when he is walking past and you are having a meal. And you wave back.” On October 15, Sarah held a fundraiser to help the families of cancer victims. To her surprise, more than a thousand people turned up. There were people who had come from Thrissur and Kottayam to support the cause. To Sarah’s surprise, many people came to chat with her because they were going through a similar situation where a family member was suffering or had died from cancer.Sarah met Rosamma Chacko (name changed). Rosamma, a woman in her forties, told Sarah her husband had shared the same hospital room with Vibin when they had to undergo a chemotherapy session. Both had the same type of cancer. The two men had chatted with each other. Sarah remembered seeing Rosamma, but they did not talk to each other. At the bakery, Rosamma told Sarah her husband died a few months later. The two women hugged. “It made me realise I was not the only one who had suffered this tragedy,” said Sarah. The proceeds went to families who had mounting hospital bills because one of the family members had cancer. And they did not have the financial resources. At the bakery, even though it is raining, a steady stream of people come in. There has been darkness in Sarah’s life but inside the bakery it is all sunny and bright. (A shorter version was published in The Sunday Magazine, The New Indian Express, South India and Delhi)

Sarah Lisa, from Holland, runs the Zera Noya bakery in Kochi. She talks about the reasons behind its success By Shevlin Sebastian On a Monday afternoon, the rain is pelting down. Outside the Zera Noya bakery in Kochi, in a cemented courtyard, a two-and-a-half-year-old girl is playing in the rain. She lets out a shriek of joy as she looks at her mother, Sarah Lisa, 32, who is sitting at a glass-topped table and working on a laptop. Her mother smiles to see the joy on her daughter’s face. To a visitor, she said, “Many people are shocked that I have allowed Adayah to play in the rain.”Sarah has been running the bakery for the past one-and-a-half years. Zera is a Hebrew word, which means seeds sprouting. This indicated a new beginning, while Noya means beautiful in Hebrew. The word can be connected to Naya in Hindi, which also means new. “I like the Hebrew language, and hence I chose these words,” said Sarah. Initially, because of Covid, she was baking from home and selling to customers. The physical bakery began on February 14, 2023, on Valentine’s Day.The items that can be found in Zera Noya include Bokkenpootje (Goat’s Feet), so named because the pastry looks like a goat’s feet. It is a meringue with apricot buttercream dipped in chocolate and almonds. Then there are stroopwafels, which is a caramel waffle and famous all over the world. You can also have the Strawberry Slof. This contains almond paste, vanilla buttercream and strawberries. The Marzipan Mergpijp is a cake with a layer of cream and strawberry jam, while the boterkoek comprises a butter cake with almonds. Speculaas is a type of biscuit. Other items include caramel tarts, muffins, truffles, apple pie and tarts, rondo, cupcakes, cinnamon braids and brownies. They also make freshly baked bread, as well as savouries like sausage rolls and chicken puffs. Sarah said that the most popular item is the Strawberry Slof. Asked why, she said. “It is the combination of the cookie, which is nutty and has fudge, sweet but not too sweet, and there is buttercream on top. But the cream is not so sweet, and there are fresh strawberries. It has a nice balance.” Asked about the composition of her customers, Sarah said, “There are all kinds of people, from different backgrounds and ages.” The prices range from Rs 30 and can go all the way to Rs 400. “Some items are expensive because we use authentic Belgian chocolate, French butter and German cream. The croissants, dipped in chocolate and cream, are at the higher end.” Asked about the difference with Kerala bakery items, Sarah said, “Bakers in Kochi use margarine and poor quality vegetable oil. But I use butter only. It is creamy and pricey too. And I always buy Callebaut Chocolate from Belgium, which is one of the best premium chocolates in the world. In Kochi, they use compound chocolate.” Compound chocolate is a mix of cocoa powder and vegetable fat.The store is open from 10 am to 10 pm. The bakery is doing well. Denise Anne from Nairobi wrote on Trip Advisor: ‘This is a great bakery filled with tasty treats and a warm and welcoming staff. The coffee is delicious and so are the baked goods.’Adds customer Lijo Joseph: ‘Classic and authentic.’ Sarah has a staff of 19 people who work in shifts. The Love Story Sarah Lisa met Vibin Varghese for the first time in July, 2013. This was in Hongkong. They were sailing on the ship, ‘Logos Hope’, and were on their way to the Philippines. While Sarah worked as a chief baker on the ship, Vibin, a marine engineer, worked in the engine room. Both were volunteers on the ship, which is regarded as the world’s largest floating book fair. Over 10 lakh people from all over the world access the ships every year. Sarah liked Vibin when she saw him for the first time while they were coming from opposite ends of a corridor of the ship. But she felt too shy to approach him although both said, “good morning” to each other. “Vibin had a charming smile,” said Sarah. “He worked hard and also had many friends.” They became Instagram friends. When the MV Logos ship was being dry docked in Hongkong, Sarah flew to China. While there, she met some people who needed help to set up a bakery. And that was how she ended up in Kangding on the China-Tibet border. It is 2000 kms from the capital, Beijing. She stayed for a brief while. But over the years, she kept going back. In 2017, when she was in Kangding, she began chatting with Vibin on Instagram. Vibin was on a ship that had docked in Mexico. “He felt excited to connect with me,” said Sarah.Sometime later, Vibin went to Kangding. After spending five days with Sarah, Vibin said, “I love you. I want to marry you.” Sarah also felt a connection to Vibin. The couple got married in Bangalore on May 5, 2018. Vibin grew up in Dubai but he chose Bangalore as the venue for his wedding because he is close to a pastor based there. Soon after the wedding, they came to Kochi, where Vibin’s parents had an apartment and settled down. Both had stopped their careers and were thinking of forging a fresh path. “Vibin gave up his career because he did not want to be away from me for nine months at a time,” said Sarah.It was in March, 2023, that Vibin got sick. In April, doctors diagnosed him with Stage 4 Linitis Plastica, a rare form of gastric cancer. Unfortunately, on December 21, 2023, Vibin, 36, passed away. When asked whether she planned to settle down in Kochi or return to Holland, Sarah said, “Many people thought that when Vibin passed away, I would go back. But at this moment, I can’t. I feel very settled here. I have imagined what it would be like if I closed down the bakery and went back. Where would I go? But then I realised Kochi is home.” Sarah was born in Den Helder, which is 84 kms from Amsterdam. The country’s main naval base is located there. Adhaya knows how to speak in Dutch, and is learning Malayalam and English. When asked to compare the character of Malayalis with the Dutch people, Sarah said, “The people in the Netherlands are direct and honest. They are private and less curious. Many aunties in Kochi ask me nosey questions. This is fine. I have got used to it. I am embracing it.” Nobody says hi or good morning when they see each other, even if they are strangers. Sarah said that in Holland everybody greets each other. “Malayalis are very reserved people,” she said. “In Kerala, dining rooms are always closed. You don’t want other people to see you eat. But in Holland, the dining rooms have large windows that open out to the street. The curtains are parted. A passer-by can wave to you when he is walking past and you are having a meal. And you wave back.” On October 15, Sarah held a fundraiser to help the families of cancer victims. To her surprise, more than a thousand people turned up. There were people who had come from Thrissur and Kottayam to support the cause. To Sarah’s surprise, many people came to chat with her because they were going through a similar situation where a family member was suffering or had died from cancer.Sarah met Rosamma Chacko (name changed). Rosamma, a woman in her forties, told Sarah her husband had shared the same hospital room with Vibin when they had to undergo a chemotherapy session. Both had the same type of cancer. The two men had chatted with each other. Sarah remembered seeing Rosamma, but they did not talk to each other. At the bakery, Rosamma told Sarah her husband died a few months later. The two women hugged. “It made me realise I was not the only one who had suffered this tragedy,” said Sarah. The proceeds went to families who had mounting hospital bills because one of the family members had cancer. And they did not have the financial resources. At the bakery, even though it is raining, a steady stream of people come in. There has been darkness in Sarah’s life but inside the bakery it is all sunny and bright. (A shorter version was published in The Sunday Magazine, The New Indian Express, South India and Delhi)

April 18, 2025

The 2006 bomb blasts on the Railway network in Mumbai: A Flashback

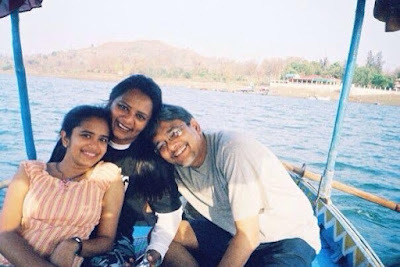

Captions: The bomb blast on the railway network at Mumbai in 2006. Meeta (centre) with her daughter Esha and husband Tushit

Captions: The bomb blast on the railway network at Mumbai in 2006. Meeta (centre) with her daughter Esha and husband Tushit Afew days ago, I had put a review of a Subhash Ghai book on LinkedIn. MeetaTushit Shah, an ExSenior Psychologist at the Narsee Monjee Institute of ManagementStudies, Mumbai, said, ‘Sowell explained and expressed. Shall surely read the book.’

· When I expressed mythanks, Meeta, in a message said, ‘I won’t everforget how you covered our story in 2006. Thank you.’

SoI went to my blog, Shevlin’s World, to read the story again.

Thiswas published in the July 16, 2006 issue of the Hindustan Times, Mumbai.

“Mylife has been shattered”

Studentcounsellor Meeta Shah struggles to cope with the brutal death of her husband

By Shevlin Sebastian

In the drawing room of the sixth floor flat ofMeeta Shah, 44, at Dahisar, there are quite a few people, mostly women. Meetais sitting on a dhurrie, beside a low windowsill, which has a garlandedportrait of her late husband Tushit, 44.

Meeta’sbody is stiff with sorrow and her eyes have become red from too much crying.She sees me at the door and beckons with her hand. But in front of so manywomen, I prefer to stay where I am. Then one by one, they hug her, thesecolleagues of hers from the Oxford Public School at Charkop, where Meeta worksas a student counsellor and they leave.

“Bestrong,” says one, in an orange saree.

It is a small drawing room, with a sofa at oneside and a bookcase on the other, on which are placed a television set and amusic system, while a guitar, encased in a cloth cover, is propped up againstone corner.

Onthe walls, there are three oil paintings of Lord Krishna, done in a deep hue ofblue. She would tell me later that painting is a hobby. Besides Meeta, there isher brother, Hasit, her father and mother, two brother in laws with family,childhood friend Mayur Desai, and daughter, Esha, 16, wearing square blackspectacles, and a white T-shirt with ‘Germany’ written across it.

I ask Meeta about how she heard the news and shesays, “I was at a friend’s place when he mentioned the television wasannouncing bomb blasts on the local trains. I rushed home because that was theexact time when Tushit was usually on a train.”

On July 11, 2006, seven bomb blasts on the suburban rail network in Mumbairesulted in 189 deaths and over 700 injured. It was orchestrated by the terror outfitLashkar-e-Taiba and Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence

Meetatried several times to call his mobile, but could not get through. “I told mydaughter Esha, ‘Keep on trying, keep on trying,’ she says. “All the lines werejammed. No calls were going through.”

In the end, it was a girl who was travelling inthe compartment next to the first class compartment, which blew up atJogeshwari, who got through to an uncle who called up Hasit. She had found thewallet and mobile phone.

“Iassume it must have fallen from his pocket,” says Meeta. “She told the uncle,Tushit was being sent to one of the hospitals but she could not say which onebecause she was not allowed to get into the ambulance.”

So Meeta and Esha, along with a neighbour andhis wife, rushed to Goregaon, where they checked the municipal hospital there.But the hospital authorities directed them to go to Cooper Hospital in VileParle. From South Mumbai, Hasit and his parents, an uncle and a cousin had alsoset out for Coopers while Mayur set out from Dahisar.

When they reached Cooper’s, it was a completechaos. “It seemed like a slaughter house,” says Meeta. “The bodies were allpiled up, one on top of the other. We had to trample over different bodies tocheck.”

Says Hasit: “The hospital manpower and themanagement were grossly inadequate. The hygienic conditions were the worst thatone could see. These government hospitals are a disaster.”

Finally, the authorities stationed the bodies ina streamlined manner and Tushit’s body was discovered by Mayur. After that,there was the hassle of getting the permission to take it away.

“Initially,there was talk that all bodies would be released only after a post mortem,”says Hasit. “Naturally, this did not go down well with the people. Then a neworder came which stated that the post mortem would be done on those bodieswhich had not been identified.”

There were more hassles: The police and therailway police had panchnamas to be filled. Therewere three copies to each but since there was a shortage of carbon paper and nophotocopying machine, each copy had to be filled in individually or photocopiedlater.

“Therewas a long queue,” says Meeta. But, thankfully, several Juhu VikasPradarshan Yojana volunteers were around to provide coffee, water, bananas andbiscuits; people in the neighbourhood rushed to get forms photocopied. In theend, the Shahs were able to take Tushit’s body out at 3.30 am.

Meeta is shaking with sobs now. Mother anddaughter cling to each other. Esha does not cry: tears just flow down her facesilently. It is too painful to see. I look outside. There are plants placed onpots just outside the window on an iron grille. I can hear the chirping ofsparrows. At a distance, there is a wide expanse of mangroves. When sherecovers, I ask her of the last time she saw her husband alive.

“I saw him last when he left for his Worlioffice at 7.15 a.m.,” says Meeta. (Tushit worked as an equity dealer with BricsSecurities Limited). “We had tea, he had toast and butter and he was veryhappy.”

Esha,who had finished her Class Ten exams, had just got her admission confirmed innearby Patkar College with great difficulty. “I had to formally get Esha’sadmission that day,” continues Meeta. “So he told me, ‘Go fast and geteverything done, we will go out for a celebratory dinner.’”

Tushit was wearing black trousers and a whiteshirt with thin, red lines. “It gives a tinge of pink from a distance,” saysMeeta. “I had selected it and it was one of my favourite shirts. My husbandloved light colours.”

When I ask her whether he had any hobby, shesays, “He always wanted to learn to play the guitar, because when he wasyounger, he could not afford to buy one.” Wife and daughter presented him witha guitar on his birthday, three years ago.

How was your marriage, I ask.

“Tushitmeans heaven in Sanskrit, what else can I say,” she says. “I had a mostbeautiful marriage. On December 11, we would have completed 20 years. He saidthat on our 25th wedding anniversary, our daughter would be celebrating her21st birthday and we should have a big party.” Meeta bursts into tears butrecovers quickly and says, “Tushit had a lot of dreams for us.”

He had wanted to take a loan and buy a largerflat, so that Esha would have a room of her own. He also wanted to buy someproperty in his hometown of Baroda. And he had dreams for Esha. His daughterhad secured 88 percent and a family friend, Vivek Mahajan, a professor ofphysics at National College had suggested that Esha should try to get admissionfor IIT.

“Aimfor the sky,” the professor had said, and Tushit had seconded it.

Asked about her husband’s qualities, she says,“He was very quiet, loving, affectionate and caring. He would never get scared,no matter how hard the challenge. He would say, ‘Difficult days will come butwe should never run away.’ He went out of his way to help people. My husbandtaught me to be strong. Now I will see how much he has taught me.”

The silence hangs heavy in the room as I say mygoodbye. Downstairs, when I step out of the elevator, I see that the Shah’spost box has a few letters in it but it has not been collected.

Atthe housing society office, I meet retired administrator G.M. Mehta, who usedto work in Mafatlal. He tells me Tushit was the secretary of the society. “Hewas a gentleman, who co-operated with everybody,” he says.

Atthe gate, Brij Mohan, the guard who works for the Shivam Security Services,says simply, “He was a very nice man.”

Ispot Mayur, who is rushing back to his TV repairing shop, and I ask him todescribe the body when he saw it first.

Itis too heart-rending to put it in words.

Upcoming post: Meeta talks about life since that fateful daythat changed her life.

April 15, 2025

A bit of Tamil Nadu in New York

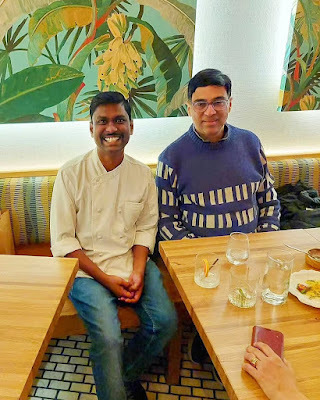

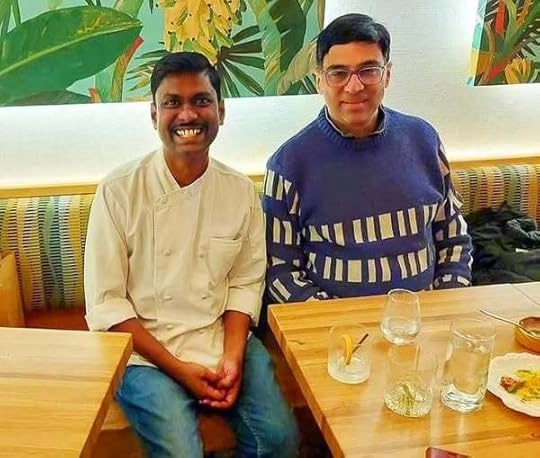

Photos: Chef Vijaya Kumar; with customer Vishwanathan Anand; Valiya Chemmeen Moilee - lobster tail. Photo by Paul McDonough

Photos: Chef Vijaya Kumar; with customer Vishwanathan Anand; Valiya Chemmeen Moilee - lobster tail. Photo by Paul McDonoughChef Vijaya Kumar, who won his third Michelin Award recently, talks about the reasons behind the popularity of the South Indian restaurant ‘Semma’ in New YorkBy Shevlin Sebastian When Oscar winner Jennifer Lawrence came into the South Indian restaurant ‘Semma’ (awesome in Tamil) in New York, chef Vijaya Kumar’s eyes widened. Because this was the second time she was coming. Jennifer’s husband, Cooke Maroney, an art gallery director, accompanied her. They ordered a wide variety of dishes. At the end of the dinner, Jennifer told Vijaya, “This is one of the best meals I have had.” On another night, he saw a woman in her late thirties shedding tears. Vijaya thought the food was too hot for her. So he walked up to her and said, “Can I offer you sweet yoghurt?” She shook her head and said, “These are happy tears. I have not had my mother’s food for a long time. The food I ate took me back to my childhood and the memory of my mother. It seemed to me she made this food. I miss home.” She told Vijaya she grew up in Tamil Nadu. Another native of Tamil Nadu did not shed happy tears. Instead he smiled. On Instagram, former world chess champion Viswanathan Anand wrote: ‘Chef Vijaya Kumar put out a spread that was summa dhool! Thanks for the generous hospitality. I had a lovely meal.’ ‘Wow,’ thought Vijaya. ‘Food can create emotions and connections with people.’ Vijaya was in the news recently after having retained the Michelin award for the third year. Asked whether he felt stressed about getting it, Vijaya said, “It is a responsibility to uphold our culture. So, it is not a pressure.” The Michelin company website states that the criteria for the awards are five: ‘The quality of the ingredients, the harmony of flavours, the mastery of techniques, the personality of the chef as expressed through their cuisine and, just as importantly, consistency both across the entire menu and over time.’Throughout the year, Michelin inspectors came many times, but they were anonymous. So, the chef does not know who the inspectors are. But Vijaya said that he ensures that every dish that comes out of the kitchen is as perfect as it can be.“I always cook from my heart,” he said. “You have to pay attention to the smallest details.” He has a 10-member team of Asians and non-Asians, but his backbone is his college mate Suresh. ‘Semma’ started in October 2021. At the entrance, there is an upside-down kettuvallam, a traditional boat. “This was inspired by the houseboats in Alleppey,” said Vijaya. A local architect, Wid Chapman, imported the materials and designed it. There are coir mats on the ceilings and hanging bamboo lamps and chairs. People make reservations online. You can book two weeks in advance. On the day Chef Vijaya spoke to rediff.com, he mentioned that there were 1450 people on the notification list. That means, if anybody cancels, the restaurant would notify those on the list. On weekdays, it is about 1000 people. That gave a sign of the popularity of the 75-seater restaurant. The restaurant works from 5 p.m. to 10 p.m. from Monday to Saturday. Every day, they do over 200 covers. The food is from Tamil Nadu. Vijaya is trying to replicate the food that he enjoyed in his childhood in the village of Natham, near Madurai, (419 kms from Chennai). ‘Semma’ imports all the spices, including black pepper, cardamom, and cinnamon, from India.“We make everything from scratch,” said Vijaya. “Just like the way our mothers did at home. We provide home-cooked food in an elevated way.” The staff begin their preparations in the morning. Asked whether he tempers the masala if the patron is non-Asian, Vijaya smiled and said, “Our company motto is ‘Unapologetically Indian’. So we don’t turn down the spices. Most of the patrons have travelled all over the world. They have eaten even spicier food on their travels. And in New York, there are cuisines from all over the world.” The most popular on the menu is the gunpowder dosa, which is now a signature dish. The menu lists it as a rice and lentil crepe served with potato masala and sambar. It costs $21 (Rs 1797). “It is nothing but podi dosa,” he said. Semma sells about 150 dosas a day. Another popular dish is the ‘Valiya Chemmeen Moilee’, which comprises lobster tail, mustard, turmeric and coconut milk. The restaurant prices it at $55 (Rs 4703). A favourite is the ‘Dindigul Biriyani’, which consists of goat, seeraga samba rice (aromatic rice from South India), garam masala, and mint. That costs $42. The New York Times food critic Pete Wells called the ‘kudal varuval’, ‘the most eyebrow-raising dish at Semma’. It is a dry curry of goat intestines.Vijaya was asked to replicate this food at the Gold Gala dinner on May 11, 2024, for 600 people in Los Angeles on May 11, 2024. It is a show that honours Asian American excellence in all fields. Vijaya collaborated with noted TV host Padma Lakshmi, the former wife of the novelist Salman Rushdie. “Padma had respect for the type of food we make,” said Vijaya. “She has been a friend and mentor.” Early LifeFarming ran in the family. His grandfather was a farmer. Since his father was in government service, Vijaya’s mother looked after their farm. During the school vacation, Vijaya spent time at his grandparents’ farm, which is close to Natham. In his grandparents’ village, the residents had no electricity in their houses, and neither were there roads. There were no grocery stores. So the people had to make everything on their farms, including rice and vegetables. They also grew millet and ragi. Years later, at ‘Semma’, he has a dish called ‘Thinai Khichdi’, which comprises foxtail millet, taro root, pickled onion and appalam. “This dish is a tribute to my grandparents,” said Vijaya. For lunch, his grandparents would forage for snails. Then his grandmother set up a wood fire in the middle of the paddy field, placed a mud pot on it, and put in spices and snails. “The taste was delicious,” said Vijaya. His classmates mocked him when he said he had snails. But when Vijaya went to culinary school, his teachers told him there was a French culinary delicacy called escargot. “This is the French word for snails,” said Vijaya. “I had to chuckle. Back to my childhood, I thought.” Vijaya said it was the time of pre-processed food. “My grandparents lived to 90 years with no health issues,” he said. “They did sustainable cooking. Now it is called natural organic cooking. They used natural fertilisers like leaves, the waste of the cows and goats. None of the farmers used chemicals.”The animals did not have processed food. They ate whatever they found in the fields. The cattle remained uncaged. They could move around freely. The animals enjoyed the sunlight and the open fields. When the people ate those animals, it was healthy and had no side effects. “Now there are so many chemicals in the food,” said Vijay. “People give many medicines to the animals. And when we eat this food, we get many diseases.” Right from a young age, Vijaya would help his mother and grandmother in the kitchen. His original dream was to become an engineer. He got admission to an engineering college, but his parents did not have the money to fund his education. So Vijaya focused on being a chef. He joined the State Institute of Hotel Management and Culinary Technology in Trichy. After completion of the three-year diploma course, he joined the coffee shop at the Taj Connemara in Chennai. He worked there from 2001-3. His friend Muthu invited him to join the ‘Dosa’ restaurant in San Francisco. So Vijaya took the plunge. Vijay worked there for six years. Sadly, ‘Dosa’ closed after a run of 15 years, in September 2019, during the Covid pandemic. Thereafter, in 2014, Vijay opened ‘Rasa’ in Burlingame, a suburb of San Francisco. There for five years in a row, he won the Michelin Award. He provided contemporary South Indian food, which included vegetables from California. But he had a dream of wanting to make authentic South Indian food. He met Roni Mazumdar and Chintan Pandya, the owners of ‘Unapologetic Foods’, who were industry friends. They had a few conversations and realised they had the same vision. And finally, they took the plunge with ‘Semma’. Asked whether he feels his life is like a dream, Vijaya said, “My life is a huge blessing. I have put in a lot of hard work. Since my childhood, I have done nothing half-heartedly. That is why I have always been a class topper. But in the end, I have to admit it is destiny.”(A shorter version was published in rediff.com)

+6

+6

April 12, 2025

When the credits stopped rolling -- a short story

By Shevlin Sebastian Muzaffar Ali stared at the face of his dead wife.He had stared at this face for 25 years. The face had remained smooth. A tiny crease where the nose touched the forehead. But the lips seemed to be turned to one side. It seemed to show distaste. The neighbour’s wife, Pramila, put a consoling arm on his shoulder.“It was a sudden heart attack,” he said. “She was only 55.”“Yes Muzaffar Bhai,” said Pramila. “She had been so healthy. What a shock!”Muzaffar knew that. Pramila and Ruksana were always in and out of each other’s houses. They gossiped about their husbands and the people of the other apartments.“It is the will of Allah,” Muzaffar said, looking at Ruksana again.Friends, relatives, neighbours, colleagues, and strangers, too, had dropped in. People stood with bent heads and palms joined in front of the body. Muzaffar nodded as he heard the words of commiseration. Because of a pain in his lower back, he sat on a chair, with a small pillow placed next to the lower end of his spine. His two sons interacted with the guests, providing tea and coffee to them. One lived in St Louis in America and the other in Melbourne.‘Ruksana has brought them up well,’ felt Muzaffar. ‘They are polite.’ His sons’ families had not come because of school and jobs.His wife had passed away, but the veteran Bollywood scriptwriter was facing death in his career.“Sir, this is outdated,” said one thirty-something director. He held Muzaffar’s script with both hands. “People are not interested in village stories. Young people want a lot of action, sex and hi-jinks. Music has to be rap or hip-hop or techno.”Muzaffar had an expressionless face, even as he pressed his fingers into his palm. He knew trends changed in films. He had been in it long enough to know that. New heroes, new concepts, new ways of shooting. And, not to forget, new writers, who were keen to edge out the older writers to lessen the competition.Muzaffar was not the only one in this situation. Other scriptwriters of his age were staring at walls. They did not bother to write. But Muzaffar, the most successful in his generation, had a writing itch. He knew that till he died, he would write something every day. His instruments included his beloved Parker pen, Sulekha ink, and A4 size paper. Muzaffar stapled the papers only when he had completed a story. Otherwise, he depended on the page numbers which he inscribed on the top right-hand corner.“Write by hand,” he had told younger writers. “There is a neurological connection between the brain and the hand. Excellent stuff comes out. You can type it up later.”But these young writers…they smiled and went back to their laptops and iPads. “Outdated old man” is what some of them said about Muzaffar behind his back.But it didn’t matter to Muzaffar what they thought. He would not give up. He felt he should be ready when the tide changed. But nobody knew how long that would take. Muzaffar had a fear he could be dead by then.At the peak of his career, he had several hit films based on his scripts. In those times, Muzaffar went to many parties. He puffed on Cuban cigars and drank Johnnie Walker whiskey. Many starlets approached him with fluttering eyelashes. They pushed their cleavages into his face and asked him to recommend him to directors.Like most industry people, he took them to bed. But unlike the others, if he felt the girl had talent, he would recommend them. A few got breaks. They were always grateful to him.One or two told him they could lift their family out of poverty from the money they earned in the industry. Since he had not seen them on the screen, he assumed they had become high-class call girls.Of course, in these times of the #MeToo movement, it was a perilous time for actors. One tweet or a Facebook or Instagram post by an angry young woman and their career would implode. Innocence was no longer presumed until guilt was proven. It was the other way around.Muzaffar knew the police, based on a complaint, could arrest the stars. Somebody told him it came under Section 498A of the Indian Penal Code. But the police played both sides. When they registered the case, the police would inform the star. They compelled the star to pay a bribe. This was divided this between the woman who filed the accusation and the cops. The stars had no option. They could not afford to bring shame to their wives and families, and ruin their public image.He wondered how men in Bollywood tackled sexual temptations these days. A senior producer told him the starlets had to sign legal agreements that mentioned the physical relationship was voluntary. But he was not sure whether this was true or a rumour. But he had read that American basketball superstar Michael Jordan kept similar agreements in his limousine. When he picked up women from a bar, they had to sign the agreement before proceeding towards his mansion. ‘Smart guy,’ thought Muzaffar.Insecurity also plagued the stars. He had heard of an ageing superstar who, after picking up the ‘Best Actor’ award at the annual Filmfare function, had flown to London and went under the knife of one of England’s best cosmetic surgeons.Some stars took steroids, apart from weightlifting, to get six-pack bodies. Others went on protein-rich diets. One star installed a mistress in a nearby house so that he could feel and look young. The wife agreed because she enjoyed the credit card her husband had given her.What about the industrialist who enjoyed sex with young boys? The pimps always took the boys to the house. Muzaffar wondered whether his wife knew. These pimps knew the danger. If they tried to blackmail the industrialist, they would end up as dead bodies floating in nearby ponds or rivers. ‘Wow,’ thought Muzaffar. ‘When you have too much money, fame, or power, you get into kinky sex. Sick.’He knew of many actors and actresses who had faded away. The point is when your career is over in your forties or fifties, what do you do after that? It is difficult to embark on another career. Fans would approach them in public places and ask, “Sir, when is your next film coming out?” The questioner knew very well that there were no roles to be had. This was the sadistic pleasure they got in plunging a knife into a man who was once up but was sliding downward.But there were stars who lasted for a long time. In Bollywood, there were people like Dilip Kumar and Amitabh Bachchan. In Hollywood, there were people like Robert De Niro, Al Pacino and Tom Hanks. They arrived on the set on time, learned their lines, and behaved well.Muzaffar remembered a video he had seen of De Niro. In it, the star said, “When things are going well, be calm. Don’t think you are on top of the world. You always got to be wary. I have seen people come. I have seen people go. You should take what is good in your life and move forward cautiously. Everybody’s dispensable.”Muzaffar had liked the video so much, especially the last line, that he had seen it many times. This was as true as it could get. And it was true for all professions, not only the film industry.Muzaffar never imagined that one day his career would end. He had thought his success would continue forever. A friend told him he was lucky to have a successful run that lasted 20 years.He knew of many scriptwriters who had one hit followed by a string of flops. Thereafter, everybody avoided them like as if they have leprosy. The industry people were superstitious. They felt these scriptwriters brought bad luck. Many of them lived in penury. Most ended up as alcoholics. A couple of them committed suicide.Muzaffar realised that in a creative industry like films, it was very difficult to have a long career. What you thought was important was no longer relevant after a few years. The stories you wrote no longer had resonance. The audience kept getting younger.Like the other members of the industry, Muzaffar drank and smoked. But he did it in moderation. He had the mental discipline to control himself.He gave his two sons an excellent education. They now lived prosperous lives abroad. But they did not send him any money. And Muzaffar was too proud to ask for it.What a different life he had compared to them.Muzaffar was born into a poor family in a village in Uttar Pradesh, one of India’s poorest states. Lawlessness was rife. People shot at each other as and when they felt like it. His father, Halim, was a farmer. Income was erratic. It all depended on the monsoon. If it was a good monsoon, the harvest was good. There was enough for the year. But if the rain played truant, he could hear the sounds of his father weeping at night. The consoling voice of his mother, Fatima, followed this. There were no irrigation facilities. The government was absent. They provided nothing.Everything depended on God. Many times, Muzaffar felt God was too busy. Billions of people were praying to Him with billions of requests. He didn’t have the time to listen to every prayer.His mother was a homemaker. So, she did not bring money to the household. His father had encouraged her to work, but she lacked the confidence. Fatima was afraid to venture out. It was only near the end of her life, after her husband had passed away, that she told Muzaffar about this.One night, when she was ten years old, she had gone to the fields to relieve herself. A youth spotted her. He was drunk. He slapped her and violated her. Muzaffar felt as if his chest had collapsed. Now how to take revenge? Who was the man? Was he alive? His mother could not even remember the face. Was it a neighbour? Or a visitor from another village? How to know? The man may be dead. Or he could be a doting grandfather? ‘In Uttar Pradesh, many people escaped punishment after committing horrific crimes,’ he thought. ‘There was no justice.’Once he remembered a man in a tea shop saying aloud, “The Constitution of India does not exist in UP.” ‘How true,’ Muzaffar thought. His father ground out his life. His grandfather ground out his life. And he was sure his great grandfather and forefathers must have all ground out their lives. In India, you cannot move from A to B. The caste system, politicians, police and the bureaucracy caused all the blocks. You stayed where you are: poor, hopeless and miserable. Used as vote banks only.From an early age, Muzaffar liked to study. He got good marks. He enjoyed writing. Muzaffar would fill up his notebook with short stories and poems. His father paid the school fees for him and his elder brother and sister till class 8. Then the rains played truant. There was no money to pay the fees.One day, Halim met a man outside a mosque after Friday prayers. Naseer was in his thirties. A clean-shaven man with sideburns. He had come to see his relatives. He worked in an international IT firm in Oman. Halim pleaded with him for support for his children’s education. Muzaffar did not know what struck a chord in Naseer.Naseer could have realised, through his own success, how education can transform the fortunes of a family. Or it could have been the desperation in Halim’s eyes. But Naseer promised to fund the education of his children. Thus Muzaffar and his siblings studied till college. His brother and sister did postgraduate degrees and got good jobs. His brother settled in Delhi while his sister, after marriage, settled in Chandigarh.As for Muzaffar, he stunned his family one day by saying he wanted to be a star in Bollywood. The family laughed all at once. It sounded to Muzaffar like a roar you hear in a football stadium, when a striker scores a goal.“You are short,” said his mother.“And dark,” said his sister.He said, “I have to give it a shot.”And so they agreed that he, being the youngest, could pursue his dreams. So, like millions of star-struck youth, he embarked on a train from the capital, Lucknow. He was in second class, non-air-conditioned, the breeze blowing in hot air throughout the day. It took 30 hours to cross 1376 kms.In Mumbai, he rented a room in a lodge in the Dadar area. It had a narrow bed. A chair. A window overlooking a slum. On the first day, he relaxed by wandering near the place he stayed. He drank coconut juice and ate Mumbai’s famous sandwich, the vada pav. He liked the tangy taste: it had mashed boiled potato, with spices and chillies added to it. It was inside two sliced buns. And they added chutney.The next morning, he travelled by the local commuter train to Mehboob Studio in Bandra. It was only 8 kms away. He noticed that the main gate was closed. There was a watchman in a blue uniform standing outside. There were several young men standing nearby. He realised they were like him. People from small-town India with dreams in their eyes. Muzaffar realised it would be difficult to get inside.He approached the watchman.“Bhaiyya,” he said in a polite voice. “At what time does your shift end?”“Why do you ask?” the man said, his eyes narrowing.“Sir, I am new to Mumbai, that’s why I asked,” he said. “I want to know the working hours in case I get a job.”The watchman continued to stare at him. He looked towards the other young men. But none of them were looking at him. They were all trying to figure out a way to get in. He turned to look at Muzaffar.“I come to work at 8 am, and I am here till 5 pm,” the man said.“Thank you,” Muzaffar said and moved away. He looked at his watch. 11 a.m. ‘Six hours more,’ he thought. ‘Might as well go back.’So he returned to his lodge, took out a Hindi novel from his suitcase and began reading.At 4.30 pm, he returned. He waited some distance from the gate. When the watchman gave his place to a colleague, he followed him. It seemed to Muzaffar as if he was heading towards the station. Muzaffar speeded up and came abreast.“Hello Bhaiyya,” he said.The watchman turned and looked at him.“Didn’t I see you in the morning?” he said.“Yes,” said Muzaffar, as he gave a brief smile.They exchanged names. The watchman said he was called Ramesh Bhendre.“What do you want?” Ramesh said.“I want to be a star,” said Muzaffar.The watchman stopped, looked Muzaffar up and down and broke into a laugh. And it never stopped. Muzaffar bit his lips. Ramesh used a handkerchief to wipe his tears.“What is your height?” he said.“Five feet one inch,” said Muzaffar.“The heroines are taller than you. What will you do? Stand on a stool and act?” Ramesh said and laughed again.Muzaffar clutched his chin. ‘Oh God, have I made a mistake?’ he thought.The watchman continued, “So many young men come to Mumbai to try their luck. They stand outside Mehboob Studio. What happens? Nothing happens. You need contacts. During the time of Dev Anand and Dharmendra, you could make it with no contacts. Remember, in the 1960s and 70s, people who worked in the industry were not that respected. So fewer people tried to enter it. Now, there are too many aspirants.”Tears appeared in Muzaffar’s eyes.Ramesh noticed it. He put his hand on Muzaffar’s arm and led him to a small hotel. He ordered tea for both of them.“In your hometown, did you act in any plays? Did you attend any acting classes? Do you know anything about technique?”Muzaffar shook his head.“You are a fool,” Ramesh said. “Look, I am going to be honest. You have the least chance of success. Take the next train and go back.”“I can’t,” said Muzaffar.“Why not?” said Ramesh.“The villagers will laugh at me till I die,” he said.This statement seemed to hit Ramesh in his solar plexus.“I can understand that,” he said. “I also come from a village in Bihar”They sipped their tea in silence.Car horns sounded. A truck emitted a blast of black smoke. Voices rose in the restaurant as conversations became arguments.Finally, Ramesh said, “This is my suggestion. Join the technical side. Look to be a helper on a set. Then move up. Get an assistant director role. Work with a director for 15 years, and learn how to direct. Develop your contacts. Then you might get a chance to direct a film.”Muzaffar shook his head.“It doesn’t excite me. I don’t want to waste 15 years being somebody’s slave,” he said.Ramesh did not take offence. Instead, he tapped his forehead with the tip of his fingers.“Can you write?” he said.“Yes,” Muzaffar exclaimed. Brightness flooded his face for the first time since he had arrived in Mumbai. “I love writing.”“Come,” said Ramesh, as he stood up. He went to the counter and paid the bill.Ramesh led Muzaffar to the station.He said, “Get down at Andheri West, three stations away. Go to Grace restaurant where all the scriptwriters meet. Make your contacts there. Somebody will be kind enough to teach you the writing tricks.”And so Muzaffar got down at Andheri West. Ramesh had several stations to cross before he could get down at Virar.Muzaffar asked for Grace Restaurant.“It’s in Four Bungalows locality,” said a passerby.“How far is it?” said Muzaffar.“Three kilometres,” said the man.Muzaffar walked the distance. He needed to conserve the little money he had. Of course, his brother said he would send money as and when needed by postal order. Muzaffar walked, flapping his leather sandals on the pavement. Now and then, he had to ask for directions. This was in the pre mobile phone era.After half an hour, he arrived at the restaurant. Muzaffar went up the three steps and entered a large hall. There were tables and chairs everywhere. Several men were sitting around. They had cups of tea in front of them and plates of pakoras, samosas, and an occasional vada pav. Many were unshaven. Some wore juba and kurtas, while others had shirts and trousers. The buzz of conversation sounded like several mosquitoes whining in his ears. Muzaffar stood and stared. He did not know what to do. Then he saw on one side, near a window, a solitary man sipping a cup of tea. He had grey stubble on his face and bags under his eyes. Muzaffar observed that the man seemed isolated from the rest of the crowd. He sat down opposite him.The man had the beginnings of a smile.“Do I know you?” he said.“No Sir, I have come from UP,” said Muzaffar.“You want to be a star?” he said.“No Sir, a scriptwriter,” said Muzaffar.“You have come to the right place,” the man said, gesturing with his hand. “All these people are scriptwriters, including me.”“Sir, your good name?” said Muzaffar.“Abdullah Khan,” said the man.“Sir, I have heard of you,” Muzaffar said, an earnest smile on his face.“I am happy about that,” said Abdullah.Abdullah paused and said, “It’s been a while since someone turned one of my scripts into a film.”“I am sorry to hear this,” said Muzaffar.Abdullah waved his hand as if he was fending off a mosquito.“That is part of the risk of being a scriptwriter,” he said.The waiter came.Muzaffar ordered tea.“Have you learned scriptwriting?” Abdullah asked.Muzaffar shook his head.“I am not surprised,” said Abdullah. “Everybody wants to learn to act.”“I love writing,” said Muzaffar as the server brought the tea on a tray.“Good,” said Abdullah. “You remind me of myself when I started out.”Abdullah told Muzaffar that he grew up in Ratnagiri, 334 kms from Mumbai. His father was a schoolteacher and an avid reader. That was how Abdullah became a reader. Then his father encouraged him to write. He did so and began getting published in the local newspapers. But instead of becoming a journalist, the magic of Tinsel Town lured him.So he came to Mumbai and did the rounds of the studios. Since he did not want to become a star, not everybody threw him out. Some directors were receptive. There was a shortfall of writers. So he read books on the art of scriptwriting and produced a script, which a director liked. Someone made a movie. It did well at the box office. Abdullah’s career began.“I will teach you the basics,” said Abdullah. “Come to my house tomorrow at 10 a.m. It is in this locality.”“Okay Sir,” Muzaffar said.Abdullah pulled out a napkin from a stash kept at the middle of the table in a holder. He wrote his address on a paper napkin and included his phone number.Muzaffar folded it, kept it in his pocket and left the restaurant.As he walked back to the station, he thanked Ramesh in his mind for his advice. Muzaffar could sense a door opening.The next day, Muzaffar arrived at Abdullah’s apartment. It was a writer’s place. Books on bookcases and on the floor. Files, cigarette packets and matchboxes are on the table. Ash in ashtrays and on the floor.Abdullah had no children. His wife was a teacher. So only he was at home, along with a maid who worked in the kitchen. Muzaffar could hear the clang of vessels. The 58-year-old immediately began talking about the various aspects of a screenplay. Around two hours every day. Then Muzaffar left. He had lunch at a roadside hotel. Then he went home and assimilated all what had been told. He began writing scenes. Soon, he started on a screenplay. His brother sent money every month. He showed Abdullah his work. From the beginning, Abdullah was appreciative.“It seems you have a natural talent for this, especially dialogues,” he said.For six months, this went on.Then Abdullah suggested they work on a script together. It was while working on this project that Muzaffar understood the intricacies of writing a script. After eight months, they finished the script. A producer bought it. They made a film. And it did well at the box office. This marked the return of Abdullah to the market after a hiatus.To his credit, Abdullah shared the income 50-50. So, Muzaffar got good money, a little over a year after coming to Mumbai. He rented a flat, bought furniture and settled down. His family congratulated him on the phone. They had seen the film and felt thrilled to see his name in the credits. Muzaffar knew this was all thanks to Abdullah. ‘A good man,’ he thought.They worked on two more scripts. That also did well. “You are my good luck charm,” said a smiling Abdullah to Muzaffar as he lit a cigarette. Much needed money came to the Abdullah household. But unknown to Muzaffar, Abdullah was in stage 4 lung cancer. His health declined. After a few weeks, he could no longer lift a pen.One day, he told Muzaffar, “When you came to me, I felt Allah was instructing me to help you. And I am glad I did.”Muzaffar had tears in his eyes as he pressed his mentor’s hand.Abdullah no longer had the strength to get up from the bed. Muzaffar came every day. He stayed in the bedroom and worked on a script that they had been working on and looked after Abdullah. His wife, Mumtaz, thanked him for his kindness.Abdullah lay on the bed for hours together. In the end, someone took him to an assisted living centre. They applied morphine so that he would not have to suffer too much. The end came finally.After a few months, Muzaffar completed the script. He got it sold. And he gave the entire money to Mumtaz. “I will never forget the kindness that Abdullah Bhai showed me,” he said. “Bhai showed me the way. I met many producers and directors through him.” Mumtaz hugged him and murmured, ‘Thank you, thank you.’ And he remained in touch with Mumtaz. Occasionally, he would give her money. Soon, Muzaffar wrote scripts of his own and some of them became blockbuster hits. He had made a name for himself. He tasted success for the next twenty years. Then the films based on his scripts started flopping. The calls by producers and actors became fewer. Until one day it stopped altogether. That was the way of the industry.Zafar, the son who lived in St. Louis, patted his shoulders. And Muzaffar’s reverie broke.“Upa, it is time for the burial,” he said.Muzaffar stood up. A group of men held the four legs of the cot, on which lay Ruksana, and took it down the stairs.Muzaffar walked along the road while prayers were being said. Other mourners followed him.Worry had creased his face in the past few months. He was running out of money. Muzaffar had to break his fixed deposits one after the other. He never imagined that such a situation would arise. But he was reluctant to ask his sons. Neither did they ask him whether he needed any money.On a recent morning, he did something completely out of character. When he got up, he saw his wife was sleeping next to him. They had a loveless marriage. She had turned away from him because she knew he was sleeping with other women. From a loving marriage, it turned into a partnership. She ran the household efficiently. Ruksana had been a homemaker all along.Muzaffar got on top of her, placed a pillow over her face and pressed hard. He could feel her body struggling as she tried to push him away. But each time she did so, he felt a renewed surge of strength. In the end, it took about half an hour before she stopped breathing.Muzaffar got off the bed and sat on the edge, his face in his hands. He could feel his entire body trembling. He couldn’t believe what he had done. But some deep, animalistic force had arisen in him and he seemed helpless in its power.That there was a Rs 70 lakh life insurance policy in the name of his wife may have been the reason. And he was the sole beneficiary.Muzaffar called his neighbour Dr. Homi Batliwala, who was the same age as him. When he entered the house, Muzaffar said, “It seems Ruksana has suffered a heart attack.”The doctor checked for the pulse. Then he lifted the eyelids and pointed a torch at the pupils. “It seems so,” Dr. Batliwala said. And he wrote out the death certificate. It was as simple as that.Everything went smoothly after that.At the kabristan in New Mahakali Nagar, they lowered the white shroud into the ground. Soon, workers covered the grave with mud using long spades.Muzaffar and his sons returned home.Muzaffar would wait for a few months because he did not want to arouse any suspicion. Then he would cash the policy. His wife was already in Jannat (paradise).Soon, on earth Muzaffar would be in financial paradise.