In the Line of Life and Death

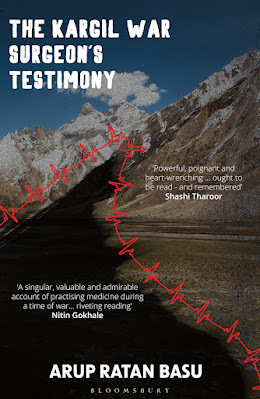

Photos: Author Arup Ratan Basu; the book cover; Indian Air Force Squadron leader Ajay Ahuja

In his book, ‘The Kargil War Surgeon’s Testimony’, Arup Ratan Basuoffers a gripping first-hand account of what it was like to serve on thefrontlines during the Kargil conflict

By Shevlin Sebastian

Arup Ratan Basu was deputed as a general surgeon to the fieldhospital in Kargil. To reach Kargil, Arup was flown from Chandigarh to Leh, andthen drove to Kargil on May 19, 1999. The surgeon on duty Major RPS Gambhir wasgoing on a two-month leave.

One of the first things Arup did when he reached Kargil wasto buy a hardbound notebook at the town bazaar. The aim was to note down hisexperiences.

With just a month’s surgical experience, Arup feltunderstandably nervous about the assignment. By this time, the skirmish betweenthe Indian and Pakistan armies had begun in the heights nearKargil.

On Arup’s first night itself, casualties were brought to thehospital. At first glance, he realised that they were wounds from bullets orartillery shell splinters. They hit limbs, necks and shoulders.

Thankfully, Major Gambhir did all the necessary surgicalprocedures.

Two days later, Major Ramaprasad told Arup, tongue-in-cheek,that he had not received a proper reception since he arrived in Kargil. Momentslater, the Pakistani Army responded to that request when there was a boomingnoise and the hospital shook.

Arup’s first patient was a 21-year-old sepoy, who had asplinter on his left armpit. Arup quickly got to work.

Once a sepoy, who was returning to consciousness, as hisanaesthesia wore off, shouted, ‘Of you mother……, just wait till I get you. Andthat bi…, who does she think she is. You bloody Benazir, just you wait.’

As Arup wrote, ‘In his reduced mental state, the poor fellowthought that Benazir Bhutto was still the prime minister ofPakistan.’

Soon, Arup got settled into the routine of the surgery:‘scrub, drape, pass the forceps, scissors, suck this area, ligatures, arteryforceps, and hydrogen peroxide, saline and betadine dressing.’

When asked why the casualties were always arriving in theevenings, a hospital staffer explained that during the day the soldiers weretrying to scale up the peaks to get rid of the Pakistani intruders. So, if theywere shot, they had to lie down till night because the rescuers wanted to avoidgetting shot during the daytime.

As the fighting intensified, one day, Arup received a callthat an officer had been wounded gravely. When he asked the name, he was toldit was Major Vikram Shekhawat of the Jat regiment.

The same seemed familiar. Then he realised that some newschannels had already declared him dead. He bemoaned the inaccuracy of the mediareports.

Arup realised some people had miraculous escapes, to thedetriment of others. Once a lieutenant colonel was travelling in a jeep fromLeh to Kargil. After a while, the colonel took the wheel to give the driversome rest. As they neared Kargil, an artillery shell exploded and a splinterpierced the passenger seat and hit the driver.

But when Arup opened up the stomach, he found that thesplinter had missed the spinal cord, the bigger blood vessels of the abdomenand the right ureter. As Arup wrote, ‘If any of those had been hit, the injurywould have been fatal.’

But not every surgery ended in success.

One day a 22-year-old sepoy was brought in, hit by asplinter. Despite several hours of surgery, the sepoy died. ‘A healthy andenergetic man was gone forever,’ wrote Arup. ‘Never will I forget the sight ofhis pale face and his distended abdomen. He had come to me for help – and whathad I done? I was numb with guilt, shame and disgust.’

During a lull in the fighting, Arup came to know from woundedsoldiers that they lacked proper rations and clothing for the freezing weather.One captain was suffering from frostbite. He said that he had survived on onechapati by day and another by night, with occasional dried nuts and sugarcandies. When that ran out, they ate snow and ice to satisfy their hungerpangs.

‘Of course, we had other things to eat too,’ he said, with asardonic smile.

‘Such as?’ Arup asked.

‘We could feast on a steady stream ofbullets.’

Arup was summoned to examine a body in a coffin. This turnedout to be Indian Air Force squadron leader Ajay Ahuja whose MIG 21 was shotdown by a Pakistani heat-seeking missile. When Arup inspected the body herealised that Ajay had been subjected to torture before being shot.

One day an officer rushed into the mess and begged for water.When asked why he looked in so much distress, he said that he had seen thebodies of Captain Saurav Kalia and his team who had been captured by Pakistanisoldiers.

The officer was trembling as he blurted out, ‘I have neverseen such horribly mutilated bodies… their nails had been pulled out, theirearlobes cut away, their eardrums punctured, their eyes gouged out, and theirbones broken. Even their penises were cut off.’

Arup had one thought, ‘Could the Geneva Conventions be simplyignored like this? Besides, could any human being do such a thing to beginwith?’

There were light moments, too.

On one occasion, the wards lit up with excitement whenBollywood luminaries, Javed Akhtar, Shabana Azmi, Salman Khan, JavedJaffrey, Vinod Khanna, Raveena Tandon and Pooja Batra arrived.

The commanding officer pulled Arup aside, pointed to one ofthe patients, and said, ‘Wasn’t that fellow admitted three days ago withintense back pain and sciatica-like symptoms?’

Arup looked with narrowed eyes and confirmed it.

‘Then how is he jumping from one bed to another trying to getphotographed?’ bellowed the senior officer. ‘Discharge him rightaway.’

As India slowly regained control of the peaks, aided by thefirepower of Bofors guns and precision airstrikes, the soldiers began moving upthe peaks. The Pakistani soldiers began to withdraw when their positions becamehopeless. International pressure was also heaped on Pakistan. As a result,there were fewer casualties for Arup to minister to.

Interestingly, when the Indian soldiers captured bunkers leftby fleeing Pakistanis, they were met with a putrid stench – the bodies of deadPakistani soldiers left behind to rot.

Arup’s book offers a raw, eyewitness account of war’s brutalrealities. The sheer waste of human resources, and equipment, the damage to theenvironment, the terrible loss of life, and the resulting disruption to normallife – there is nothing good about war.

Or as Shashi Tharoor wrote, ‘In Basu’s view, it’s not so muchabout the futility of war as its untold human cost, which gets muffled beneaththe nationalist pomp and clamour of any war effort – even one like Kargil,undertaken in self-defence. Yet for the parents who lost their sons, wives,husbands and children, their fathers, this is the only real consequence ofwar.’

Adds Lt General (Retd.) Vinod Bhatia, ‘Basu captures thehuman face of the Kargil war. Touching, easy to read, and an interestingperspective.’

After his short stint of two months, when he did anastonishing 250 surgeries, as Arup prepared to leave, he fell into aphilosophical mood. ‘The concept of war is based on the idea that others shouldbe subjugated,’ he wrote. ‘Humans have a desire to dominate others, and controland possess that which does not belong to them. This insatiable greed has ledto history repeating itself time and time again.’

For his services, Arup received the Yudh Seva Medal.

In 2001, he was deputed to Kabul, following the collapse ofthe first Taliban services. He served with distinction for ten months. Later,he served in various command hospitals of the Army Medical Corps beforeretiring to his hometown of Jamshedpur in 2013 where he works as a consultinggastroenterology surgeon.

Arup has written three books in Bengali. This is his first inEnglish.

(Published in kitaab.org)