Shevlin Sebastian's Blog, page 17

October 3, 2022

Atlas Ramachandran is no more. A look at his life and career

Renowned businessman and film producer Atlas Ramachandran died on October 2 at Dubai at the age of 80, following a heart attack. A high-flying entrepreneur his jewellery business came crashing down, when he was arrested in 2015 for non-payment of loans he had taken from banks to the tune of Rs 1000 crore.

He was sentenced to jail for three years. Thanks to friends who helped to meet his dues, Ramachandran was released two-and-a-half years later. When Dubai-based lawyer Arun Abraham visited him in hospital just before he passed away, he was optimistic about re-starting his business.

The following piece was published in 2012 when he had just opened an outlet in Kochi.

Trusted by millions

Dr M M Ramachandran, the founder-chairman of the Atlas Jewellery Group, talks about his memories of Mahatma Gandhi and other luminaries. He also speaks about his life as an entrepreneur, film producer, distributor, exhibitor, actor, and philanthropist

By Shevlin Sebastian

On the morning of January 31, 1948, Dr M M Ramachandran, the founder-chairman of the Atlas Jewellery Group, remembers his uncle Dr. Sethu Madhavan come running to the family tharavad in Thrissur, tears streaming down his face. “Bapuji (Mahatma Gandhi) has expired,” he said. And the entire family, comprising Ramachandran’s parents, uncles and aunts, cousins and relatives, burst into tears. Ramachandran was only six years old. “Our house is close to the railway line. On the trains, people were shouting and crying.” They had heard from passengers coming from the north that somebody had assassinated Bapuji the previous evening.

“No Indian should forget the ‘Father of the Nation,’” says Ramachandran. “As a child, my parents taught us about the ideals of Gandhi and read excerpts from his monumental work, ‘My Experiments with Truth.’ He was an idol for me.”

He also has memories of the late Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru. “The Prime Minister came to Thrissur a few times and gave speeches at the Thekkinkad Maidan. I would sit in the front row. Security was casual in those days. He spoke in English and was a gripping orator,” he says.

Ramachandran is also a fan of Nehru’s daughter, the late Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. “Her biggest achievement was the liberation of East Pakistan (Bangladesh) from West Pakistan in 1971,” says Ramachandran. Of course, Indira’s biggest mistake was the imposition of the Emergency on June 26, 1975. “That was when freedom was suppressed,” says Ramachandran. “I have lived through an eventful period of our history.”

Ramachandran, himself, has had an eventful life. He grew up in Thrissur, as the son of a poet, V Kamalakara Menon. Ramachandran’s grandfather was a contractor in Cochin State and was the first to introduce cement in construction work.

“He knew all the difficulties of doing business, and wanted my father to have a government job,” he says. His father got a state government job and worked for several years. Meanwhile, Ramachandran passed his B. Com from Sree Kerala Varma College. But jobs were scarce in Kerala. Unemployment was rampant. “My elder brother had a minor job in Delhi,” he says. “So, I went there in search of one.”

In the capital, Ramachandran saw ‘No Vacancy’ signs everywhere. Then the Canara Bank opened its first branch in Delhi, and they took Ramachandran in as an apprentice with a small stipend.

“In six months, they made me a clerk,” he says. And within two years, he became an assistant accountant because he had passed the Certified Associate examination of the Indian Institute of Bankers with distinction. But Ramachandran continued to sit for bank exams and got selected as a probationary officer by the State Bank of India and was posted to the State Bank of Travancore in Kerala in 1966.

“Thereafter, I worked all over the state,” he says. “Instead of going as a tourist, I went at the bank’s expense.” He worked for seven years with SBT.

In 1973, the economy was in free-fall. The petrol price jumped from 3.5 dollars per barrel to 10.6 dollars. “I had an official jeep, and my car,” he says. “Despite that, I used to travel by bus. By the 20th of the month, I would exhaust my salary. I would request my father to send me some money.” Ramachandran felt he needed another job.

He saw an advertisement in a newspaper by the Commercial Bank of Kuwait for a walk-in interview at the Connemara Hotel in Chennai. He went to Chennai by train. There were 2,000 people in front of the hotel gates, which were closed. “Somehow, I entered and became one of 200 persons who wrote the test.”

Thereafter, Ramachandran was one among five who were called for the interview. The interviewer asked, “Where is your passport, Mr Ramachandran?” It was then that he realised that there was something called a passport. “I began perspiring,” he says. “They told me not to worry. You are selected.” Thereafter, Ramachandran applied for a passport and departed for Kuwait in March 1974.

They sent him for six months of training to Athens and two months to Philadelphia. He took over as the credit manager for domestic branches and later as international division manager. In addition, the bank asked him to train other managers. And for this second job, Ramachandran received an additional salary. “In those days, I was the highest-paid Indian,” he says.

One day when Ramachandran was returning from the bank, he saw a sizeable crowd in front of some Indian jewellery shops. “I was young and curious,” he says. “I stopped the car and asked the reason for this. They said, ‘Don’t you know that the gold price has fallen? We are all queuing up to buy it.’ I was taken aback. There was such an enormous demand for gold. An urge arose in me to do some business rather than be an employee.”

In the bank, Ramachandran was handling the New York and London branches. “I had to recommend loans. The smallest of the loans was 5 million dollars. I was running a tremendous risk. If something went wrong, the management would hold me responsible. I thought that if I start a small business, even it is small, I could be my boss.”

But he had little savings. So, Ramachandran went to the chief general manager of the bank, H J Kwant, a Dutchman, and secured a loan of 20,000 dinars. This sufficed to pay the money for a shop in the brand-new Souk Al Watiya in Kuwait. “No Indian dared to take a shop in such a posh place,” he says. “I had money left over to buy only 2 kilos of ornaments but did not know the business. The only way to learn was from a goldsmith.”

Luckily, he befriended a Madhavan from Pallam, Kottayam. “He was not prepared to tell me the secrets,” says Ramachandran. “I told him I am a bank manager and he would lose nothing by passing me his knowledge. So, he told me the details.”

Ramachandran’s jewellery outfit was a success from the very beginning, thanks to a stroke of luck. His shop was next to the only church in Kuwait: Our Lady of Arabia.

“The Indian maids were in plenty, especially from Goa,” he says. “They told me, ‘Jesus will bless you! It is good you have opened your shop nearby. Now we can come to church, buy the gold, and have a lot of time left for chitchat. Otherwise, all the time will be wasted to go downtown. We will bring all our friends.’”

And they kept their promise. And all they wanted was a sovereign chain and a cross. “I made my money on these sales,” he says.

Today, Atlas Jewellery operates in seven countries: Qatar, Bahrain, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, India, and the United Arab Emirates. In the UAE, there are 24 shops, and the maximum sales are in Dubai.

“Our customers are mostly Malayalis,” he says. When asked for the reasons behind his success, he says, “Give them the best. They will come back to you. My products are authentic.”

What is 22 carat? It is 22 divided by 24 = 916.666. If pure gold in the ornament is 916, and the rest is alloys, it is called 22 carat. “Instead of 916, we keep 920 as our base,” he says. “In all the tests conducted by the government, it should pass. When conventional soldering is done, other elements might get added, as opposed to the cadmium soldering technology used by Atlas Jewellery.”

He says that the Malayalis in Dubai, before they leave for their annual vacation to Kerala, would buy jewellery from several shops. Back at home, they get it tested. “I am very happy to say that when they return to Dubai, they say, ‘Sir, only yours was 22 carats. We will bring all our friends and relatives to you.’ So, I made my name by word of mouth.”

Ramachandran also instinctively understood the power of advertisements. “Those days dealers would tell me that gold should never be advertised,” he says. “People should come and ask for it. I said, no, like any other product we have to advertise. I was the first to cooperate with the World Gold Council to advertise gold.”

He was also the first to distinguish between 22 and 24 carat gold. “I would have arguments with the dealers,” he says. “I would tell them, ‘Ornaments are only 22 carat, so why are you charging 24 carat?’ When I started Atlas in 1981, I gave separate prices for 22 and 24 carat gold.”

Incidentally, the word ‘Atlas’ came up by accident. When he went to get a licence from the Ministry of Commerce in Kuwait, he suggested many Malayali, Indian, and English names. The official said, “Myseer (which means ‘impossible’ in Arabic). This is an Arab country. Give me Arab names.” So, Ramachandran asked the official to give a name. The man said, “Khud Ya Atlas (Take the name Atlas).”

In Dubai, Ramachandran was much respected, because of his contribution to the annual Shopping Festival. In 1996, the government of Dubai - under the directive of HH Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, UAE Vice-President and ruler of Dubai - invited four people from the gold industry and asked for suggestions.

Ramachandran, who later became the chairperson of the Festival Gold Promotion Committee, came up with the idea to give away one kg of gold on a raffle basis every day. “It was a runaway success,” says Ramachandran. “This concept attracted a lot of tourists during the festival and I secured an illustrious name in the government.” In the inaugural festival, 43 kgs of gold were given away.

Thereafter, over the years, Atlas has diversified into real estate, advertising, photography studios and healthcare. In 2010, the company opened a multi-speciality hospital in Ruwi, Oman. In 2010, Ramachandran was ranked 35 on the list of the 100 ‘Most Powerful Indians in the Gulf Co-operation Council countries.’

And, finally, on August 25, 2012, Atlas finally arrived in Kerala with a showroom at Edapally, Kochi. Asked why it took so long to come to Kerala, Ramachandran said, “The Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS) was only set up recently,” he says. “People were selling 18 carat gold marked as 22.”

Ramachandran made a television programme called ‘Swarna Nirangal’ (The Colours of Gold), in which the anchor shows an advertisement which states, ‘I will give you 916 gold.’ Then the anchor asks, “If this is a 100-year-old company, which claims to be giving 916 now, what were they giving earlier?”

Ramachandran was excited by the response to the Kochi enterprise. But despite this he is worried about the economic future of Kerala. “Where is the agricultural and manufacturing activity? Montek Singh Ahluwalia (deputy chairman of the Planning Commission) said that if Kerala does not cultivate rice, the heavens will not fall. I don’t agree. We must have agriculture. It is our culture and we must not forget that.”

Another worry is the rise of religious fanaticism all over the world. “Religion appears to play a very important part in the life of people and nations,” he says. “It is meant for the well-being of people. But people think that the way to salvation is through one particular religion. It has led to a lot of destruction.”

The opposite of destruction is creativity. Few people know Ramachandran is a creative person. In 1988, Ramachandran set up Chandrakanth Films for production and distribution. The first film, ‘Vaishali,’ became a box-office hit running for 111 days and is now regarded as a classic. Later, he produced ‘Dhanam’ and ‘Sukrutham,’ and directed ‘Holidays.’ He has also acted in ‘2 Harihar Nagar,’ ‘Arabikatha’ and ‘Anandabhairavi.’

Apart from that, he is also providing scholarships for deserving students in Kerala and the Gulf countries and makes regular donations for traditional arts and culture in Kerala. In fact, he has done a doctoral thesis on traditional arts and culture. “In my spare time, I am trying to promote akshara shlokam,” says Ramachandran, who is also a director of the India Vision television channel.

All in all, Ramachandran has lived like up to his company name: an Atlas who has lifted the globe, on his shoulders, and in his own individual style.

(Published in Express Ensembles, September 23, 2012)

September 25, 2022

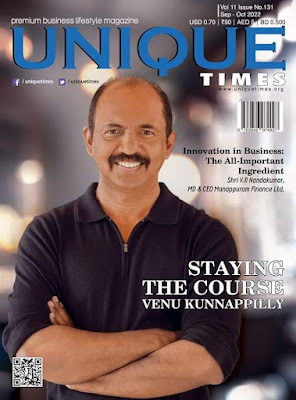

Staying the course

Venu Kunnappilly made his debut as a producer with the hit, ‘Mamangam’, in 2019. He talks about his experiences in Mollywood

Photos: Mohanlal and Mammootty with Venu Kunnappilly and his family

By Shevlin Sebastian

From childhood Venu Kunnappilly loved watching movies. It remained his primary pastime during college and in his life in Dubai. One day, a thought arose in his mind: how can I enter Mollywood? Venu pondered over the options. He could be an actor, director, cinematographer, singer or scriptwriter. But he felt he did not have the talent for any of them. So, Venu felt the only way was to be a producer.

Through a friend in the industry, he sent out feelers he wanted to produce a film.

Vivek Ramadevan, one of Mollywood’s leading entertainment and marketing consultants, met Venu. He narrated the story of ‘Mamangam’ for over two hours.

Every 12 years, in the 18th century, the Mamangam festival would take place on the banks of the Nila river in the town of Thirunavaya in north Kerala. The Zamorin, the Hindu chiefs of Kozhikode, conducted the festival. Several years ago, they seized ownership of the festival from Valluvakkonathiri, who were the rulers of an independent kingdom in central Kerala.

Every year, the Valluvakkonathiri sent their best warriors to confront and kill the Zamorin, who would always appear at the festival with his family members.

Venu liked the script because he had always liked to watch historical themes on film. In his childhood, he liked ‘Unniyarcha’ (1961). This was based on Unniyarcha, a legendary warrior. She had been mentioned in ‘Vadakkan Pattukal’, a set of ballads.

Another film he enjoyed watching was ‘Kayamkulam Kochunni’ (1966). Kochunni was an outlaw who stole from the rich and gave to the poor in present-day Travancore.

To get confirmation from Mammootty, Venu met him for the first time in a suite at the Grand Hyatt in Dubai in 2017. He was taken aback by the superstar’s genuine respect shown to him. Mammootty inquired whether Venu wanted to drink or eat something. Then he asked about Venu’s family and all other aspects of his life. “Mammootty was a straight-forward, and down-to-earth person,” said Venu.

The aspiring producer was keen for Mammootty to take the lead role. Because he knew the actor excelled in historical roles. He had admired Mammootty’s performance in ‘Pazhassi Raja’ (2009).

Mammootty had played Pazhassi (1753–1805), who was the de facto head of the kingdom of Kottayam, otherwise known as Cotiote, in Malabar.

Pazhassi fought against the exploitation of farmers, through steep taxation, by the British East India Company. There were constant battles between Pazhassi and his men against the British.

Eventually, the British killed Pazhassi, aged 52, on November 30, 1805, in a gun-fight at Mavila Thodu, on the border of present-day Kerala and Karnataka.

Mammootty confirmed again. So, Venu became a producer.

When the film came out, ‘Mamangam’ became a box office hit. It grossed Rs 100 crore at the box office.

Venu learnt some important lessons after his first film. “If you have a good relationship with a person, it might break down when you are working together on a film,” said Venu. “So, it is imperative to have clear-cut legal agreements with all the crew members.”

To avoid a financial loss, the producer must ensure he has lucrative deals with OTT platforms and buyers for satellite rights. “So, when the film hits the theatres, you have already recovered your costs,” said Venu. If the film becomes a hit, then all the theatre income is a profit for the producer.

Following ‘Mamangam’, Venu has ploughed ahead. He produced ‘Night Drive’, and ‘Drishyam-2’ in Kannada. ‘Eesho’ is coming out next month. Directed by Nadir Shah, it features Jayasurya and Namitha Pramod in the lead roles. The shoot of the film, ‘2018’, budgeted at Rs 25 crore, is in progress. It stars Kunchacko Boban, Tovino Thomas, Asif Ali, and Vineeth Sreenivasan. The shoot of two other films, ‘Chaver’ and ‘Malikappuram’ is also taking place now.

Venu also released a Hollywood film called ‘After Midnight’ on February 11, 2021. Jeremy Gardner and Christian Stella play the main roles. The meta score on imdb.com is 55 out of 100.

Reflections about Mammootty and Mohanlal

In April, 2019, Mammootty was shooting for ‘Mamangam’ during the month of Ramzan. He was fasting the entire day. A battle scene was being filmed on an 18-acre land, behind Lakeshore Hospital in Kundanoor, Kochi.

“After a whole day’s shoot, with no food, Mammootty had to continue shooting till 2 a.m.,” said Venu. “But he never complained at all. He was tireless on the set.”

In the film, Mammootty had to don the role of a woman. The actor was chatting with Venu and cracked a few jokes. Then the director said, “Action.” Right in front of Venu’s eyes, he saw Mammootty transforming himself into a woman. “It was amazing how effortlessly he slipped into the role,” said Venu.

The producer realised it was the passion for acting that drove Mammootty. “Whatever role he takes on, he plays it with the utmost dedication,” said Venu. Immense wealth and stardom have not satiated Mammootty’s burning drive to excel. “The youngsters of today make two or three films a year. The rest of the time they are enjoying themselves and going for vacations,” said Venu. “Mammootty’s primary focus and enjoyment is acting.”

Venu met Mohanlal three years ago. The actor expressed an interest in buying an apartment in ‘The Identity Twin Towers’ that Venu was building right next to the Crowne Plaza hotel in Kochi. Mohanlal bought two apartments on the 15th and 16th floor. This was converted into a duplex, with interior staircases, and has a floor area of 9500 sq. ft.

As for Venu, he stays on the 11th floor. The view from the veranda is breath-taking. Except for the Le Meridien hotel, which is on the opposite side, the vista is one of green vegetation, rivers and the wide arc of the sky above. A sharp breeze blows all the time.

“Mohanlal is able to get along with all sorts of people,” said Venu. “He has no airs at all. When he is talking to you, he is so down-to-earth that sometimes you forget that he is a superstar. He always asks about others life and what is happening in it.”

Both Mohanlal and Mammootty have an immense positive energy about them. “It could be because they are both doing work for which they have a great passion,” said Venu.

On how they have endured as stars for over 30 years, Venu said. “Both arrived at the right time and at the right place. They have played so many roles which have been ingrained in the Malayali psyche. We will always look at them with awe and reverence. But they have also maintained their image.”

Early life and career

Venu was born in Ayyampilly on the Vypeen islands. His father cultivated prawns and did pokkali farming (pokkali is a saline tolerant rice that is grown in the coastal regions). Venu did his early schooling in the Rama Varma Union High School in Cherai.

The school is over one hundred years old. The large building has a tiled roof, and British-style columns along the veranda of the ground floor. There is a sandy courtyard in front. Today, it has over 800 students on its rolls.

After completing his Class 10, Venu did his pre-degree at the Sree Narayana Mangalam College, Maliankara. In 1986, he joined the Noorul Islam Polytechnic College in Tamil Nadu to do a three-year diploma course in automobile engineering. Venu had a desire to become a vehicle inspector in the state motor vehicles department. That would assure him of a steady salary.

But after graduating with high marks, he got a job as a trainee in the Royal Enfield company. It makes the iconic Bullet motorcycles at their factory near Madurai. But he worked there for only four months before he got a chance to go to Saudi Arabia.

On May 17, 1990, he joined as the head of the automobile division at the Al Omarani company. The agency did the maintenance for all government vehicles. But Venu soon discovered that his lack of experience was creating a problem.

Venu had worked with the Tata, Ambassador Ashok Leyland and Maruti cars. But in Saudi Arabia, he was working with Mercedes Benz, BMW, the Range Rover and Jaguars. Venu was seeing their engines for the first time.

The workers, Malayalis, North Indians, Bengalis, Filipinos and Pakistanis, came to him asking for solutions. He found he did not have the necessary knowledge to help them.

But somehow, he learned quickly and worked in the company for three years. In the last year, the company became bankrupt. They paid no salary. Venu found it difficult to eat. Reluctant to come back, Venu did odd jobs here and there.

He worked in a vineyard at the hill station of Abha, which is 7200 ft. above sea level. The weather is mild throughout the year. People had to wear sweaters all the time. There is no air-conditioning but heaters are everywhere. There are kilometres and kilometres of vineyards.

Venu had to walk a few kilometres every day to reach these farms, which were in remote areas. He earned 20 riyals a day. “It was a difficult time,” he said. “Sometimes, we encountered snakes in the fields. We had to be careful.”

Unfortunately, even though the labour rate was agreed upon beforehand, at the end of the day, the supervisors would say the work was not perfect. They would give the workers only five riyals. “It was exploitation,” said Venu. “I would feel upset, but there was little I could do, since I was living in a foreign country.”

In August, 1993, Venu moved to Dubai in the United Arab Emirates. He worked as a sales executive in a company which dealt in spare parts for the Range Rover. During this time, he learned everything about the business.

Finally, in 2000, Venu took the plunge. He opened a wholesale shop dealing in automobile spare parts in the Deira market. A lot of Africans would come there. Venu would import from India and China and export to several countries in Africa. The business did well from the beginning.

In 2001, he started a packing company with his roommates, with whom he stayed before his marriage in 1997. The company specialises in blister packing. This is a pre-formed packaging, made of plastic, used for consumer goods, foods, and medicines. This has become a large company. He also opened a spare parts shop in the Congo called Auto King. In 2004, he opened a factory making lubricant oil in Ajman.

Venu has made many visits to South Africa, Mozambique, Zambia, Malawi, Somalia, Djibouti, Tanzania, Kenya, Angola, Togo, Benin Republic, Niger, Burkina Faso, Guinea Bissau, Ghana, Mali and other countries.

Venu said the Africans differed from place to place. The people who lived under Portuguese rule, in countries like Angola, Congo, Guinea-Bissau and Mozambique, had suffered from centuries of slavery. So, they had low self-esteem and were deferential.

The people who lived under French rule, like in Togo, Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast, and Mali, were tough and bargained hard when they did business. But the smartest people were those who grew up under British rule in countries like South Africa, Zambia and Ghana.

“They had self-confidence because of the excellent education they received,” said Venu.

But across all countries, one common trait was that the Africans did not trust outsiders. That has been the impact of hundreds of years of slavery. They have a fear that they will be cheated and exploited. “Now, the Chinese are exploiting them,” said Venu. “Poverty is still widespread. Many people only get two meals a day.”

Venu continues his business in Dubai, building construction in Kerala and a shop in the UK. He also has a film production company in Los Angeles and a Greentech company in Sweden.

Venu as writer

In November, 2021, Venu published a collection of 15 short stories called ‘Victoria 18’. This was released at the Sharjah Book Fair last year. Venu wrote the stories in an autobiographical style, but it is all fiction.

Finally, when asked about his advice to young Malayalis, he said, “Please remember, life is very short. No other species has the freedom that we have. We can live and work anywhere. There are so many opportunities. Youngsters should go in search of them. They should avoid spending their time in negative thought processes and harassing people. You should have a dream. And follow it. You have only one life and it goes fast. Always remember that.”

(Published in Unique Times)

September 16, 2022

An ode to swimming

By Shevlin Sebastian

Photo: At the Raviz Hotel in Kollam, Kerala

Heavy rains hit Kochi in the last week of August. There was lightning, cloudbursts, and furious winds. This resulted in flooding in the low-lying areas. The non-performance of the public works department and the Cochin Corporation ensured it happens every year.

There was an unspeakable dread about what damage this incessant rainfall was going to do. We Malayalis have remained shell-shocked following the disastrous flooding all over Kerala in 2018. It wrecked the lives of so many families. The floods destroyed thousands of houses, apart from roads and bridges.

So, I felt an intense relief when I woke up on a Saturday morning, stepped into the verandah, and saw a cerulean blue sky. Not a single cloud around. The sun was up and about. The leaves in the trees shone with a rare intensity. Thanks to the rains, all the dust had been wiped away. They were all ready to glow.

And glow they did.

I decided to go for a swim.

At the pool, I encountered two blues. The chlorine blue of the water and the open sky above. As I set out, in freestyle mode, I admired the beauty of various designs, as the slanting Eastern sun hit the water. In the refracted light, I saw triangles, circles, quadrilaterals, squares, white stars and maps of countries. I blinked and thought, ‘Did I see that?’

I was not sure.

When I turned my head to the left, to breathe, sunlight hit my iris. It felt like a massive ball of light. ‘This is what religions say, “I am the light,”’ I thought.

Is this like the light I am going to see at the moment of my death? So many people, who had medically died and returned to life had recounted seeing such a light in Raymond Moody’s classic book on near-death experiences called ‘Life After Life’?’

I blinked and turned my head to the other side.

As I increased my speed, I could feel all the stale air being expelled from my lungs. Fresh air rushed in to fill the vacuum.

It made me heady.

Oh, the beauty of swimming. Every part of your body is in action. Since we are moving through water, there is no fear of a knee injury, a back sprain, or a torn hamstring.

It did not take long before a sense of peace and relaxation pervaded me. I remembered reading somewhere that when water sloshes in the ears, it is like the sloshing sound you hear when you lie in water inside the womb. That’s why you feel peaceful in the pool.

Is this true?

I am not sure. Not all babies have a peaceful experience in the womb. Some mothers go through stressful times, for various reasons, during the nine months of their pregnancy. So, for that baby, the sloshing sound does not indicate peace and happiness. Rather, it reveals anxiety and fear.

After several laps, I get up, climb out and stand on the deck, with my back to the sun. I am looking for vitamin D. Apparently, it is healthy for the spine and solves back pain. Again, is this true? Who knows? So many theories. How many of them are true? Nobody knows. And yet there are people who believe so deeply in ideological theories, they end up becoming fanatics. They experience no qualms or pricks of conscience as they shed the blood of ‘The Other’.

I dive back into the pool and increase the speed as I reach the last laps.

I can sense endorphins are being released into my bloodstream.

The human body is such a wonderful instrument. So few of us look after it. We gorge on food, most of it unhealthy, we never exercise, and we put intense stress on it. We put on too much weight. And our tiny knees must bear this enormous load. Is it any surprise that the knees and the body break down as you age?

I take a breather by doing a backstroke. Now I can see the entire arc of the sky above me. I have seen so many moods of the sky over so many years when I lie on my back. A jet black sky, with masses of clouds; a grey sky; a sky with silver streaks; and a blue sky with puffs of scudding clouds, which look like elongated pieces of cotton.

Sometimes, I see a flight of birds moving forward in a triangular formation, their beating wings all synchronised. I have also seen commercial planes, Air Force jets, with their pointed tips, and the grey helicopters of the Indian Navy.

I look at the sky and wonder where all the dead souls are? I know they are all up there. My dad, uncles, aunts, cousins, friends, former colleagues and… a former girlfriend who died in her late twenties. So many have moved on to the next dimension of reality.

I stop at the shallow end and look at the coconut and other trees framing the pool. Sometimes, under a fierce wind, the leaves will fly away and land, with a sea-saw motion, on the surface of the pool. Then the veteran lifeguard will scoop it out using a butterfly net attached to a long pole.

I love it when it rains hard. The pinpricks that hit my back… it feels as if you had a massage.

So, finally, this session is over. As I climb up the steps, holding the rod with both my hands, I can sense dopamine surging through my brain. I feel happy, optimistic and positive.

My body is singing along with my soul.

I look forward to whatever the day has to offer.

I know this day will never come again.

I offer my silent thanks to the Universal Spirit for this wonderful, though temporary, life.

August 23, 2022

An encounter in New York -- Flash Fiction

By Shevlin Sebastian

A woman is walking at a quick pace down a New York street. Because of the clouds, there is a greyish tone to the day. She is a slim woman with close-cropped hair, which reaches the collar. Alice Baker is pale-skinned, but she has put red lipstick on her lips. The colour stands out when you look at her face. She also has striking eyes — a thick grey with a black dot in the middle. Her eyelashes stick out as if she is astonished.

Alice wears flat, black leather sandals. On her left wrist, she wears a thin, gold watch. The dial is made of gold, including the hour and minute hands.

A black man ambles up. He is 6’2” tall. Unlike the woman, he is heavy-built, with a paunch that falls over his stomach. It rolls about like a wave. He has grey stubble. Not thick, but hairs sprinkled across the chin. There is a smell of rye on his breath. He has consumed several glasses of liquor.

Ben Whitaker is a former Army soldier who had done three stints in Vietnam. He shot dead many Vietnamese. Because he was often near bomb blasts, he has damaged his hearing.

After seeing so much violence, Ben returned to America, a troubled man. His marriage broke up. He fought with friends and relatives. Ben could never hold a proper job. He always ended up fighting with his supervisors. So far, he has avoided run-ins with the police. He survives on his Army pension.

His apartment is ill kept. His shorts, underwear and socks lay strewn about on the floor and the sofa. There are empty beer cans and whisky bottles on the floor, as well as cigarette ash. Half-eaten food packets lay on the dining table. The odour is a mix of perspiration and stale food.

As the black man sees the white woman, Ben thinks of privilege, white wealth and a smooth life. He thinks the world is unfair. Too many black people fought in Vietnam. She is too young to know about the sacrifices of the blacks in Vietnam. She has a happy-go-lucky life.

Alice might not agree. She has broken up with her boyfriend of three years. And she is feeling low. Her parents had divorced when she was a child. She grew up with her mother Deborah. She rarely saw her father, Robert. He was a wealthy architect and had married again. But to his credit, Robert made the alimony payment on time for years together. He married again and had two children.

Deborah never married again because Robert was the love of her life. So, she had a look of permanent sorrow on her face. Down turned lips and downcast eyes. She lost the incentive to look good. Her blond hair no longer has a lustre. Deborah wore loose-fitting shirts and trousers. She sat at home the whole day. Alice was glad when she left home and joined college. That was when some oxygen entered her lungs for the first time.

But Ben did not know this.

As she came abreast, a lot of blood flashed inside his brain, face, and heart. The veins in his forehead pounded a ferocious drumbeat.

Ben took out a gun and knocked Alice’s face out.

Ben carried on walking.

The 24-year-old lay on the ground, still and lifeless.

Onlookers came rushing up.

One called 911.

There were many surveillance cameras on this street. It would be a matter of time before the police arrested Ben.

But he has no plans to escape.

As he continued walking, the 64-year-old pressed the steel barrel to his forehead.

He took a deep breath and pulled the trigger.

As he rushed toward death, all he heard were the screams of onlookers....

August 15, 2022

Lessons from Laal Singh Chaddha!

Laal Singh Chaddha is a beautiful movie.

There are several history lessons in it.

Riots are shown at ground level. You watch, with horror, the use of a tyre as a burning necklace to kill people. You experience the fear and the terror of ordinary citizens.

It showed the venality of politicians.

Throughout the 75 years of our history, they have ignited riot after riot in pursuit of vote banks. Our leaders have pursued division among the people with a zeal bordering on the maniacal.

You see the beauty and charm of the guileless Laal.

Laal Singh reminds us how quickly we lose our childhood innocence. We turn into rough, hard-hearted and cynical people.

It shows the power of a mother’s love. And how she can transform the life of a disabled son. A study of human history has shown that most of the great achievers enjoyed the unrelenting love of their mothers.

It shows the power of patience. Laal Singh waited and waited before he finally won over his lady love, Rupa.

The movie reminds us that death is always a part of life.

The film reveals the humanity of people. It is easy to hate when people are abstract concepts, like ‘He is a Muslim’. But they are as human as you are.

Laal Singh tells us that God is within us. Which is why we don’t need religion.

It showed the immense contributions of Punjabis to the Indian Army over several generations.

When Laal Singh runs through the length and breadth of the country, you realise how beautiful this nation is. Every state feels like an independent country, with its own culture, food habits, and mores.

Once, Rupa asked him about his experiences in Kargil. Laal Singh focused on how beautiful the Himalayas looked at night. It was an invaluable lesson: to look at the beauty instead of the darkness. We always look at the negative.

It was a film which reminded us of the beautiful concept of unity in diversity, now under ferocious attack.

Laal Singh showed how sworn enemies can become lifelong friends.

Although we don’t see it, the production team took an immense effort in the film's making.

As a sign of the polarised times we live in, the disclaimer at the beginning, in English and Hindi, was about 25 lines long. There was a commentary accompanying it.

During earlier, calmer times, the disclaimer was one line long.

As a newspaper article mentioned, Aamir Khan is one of the greatest story-tellers of his generation. We should cherish and support him and not abuse him because he is a Muslim.

Don’t miss Laal Singh Chaddha!

July 7, 2022

Hitting 90 with panache

Photos: AM Chacko;

From left: Jeena and Vinod Mathew, Anoop Thomas and Elsy Paul, Chandrakanth Viswanath, yours truly, Anil S and his daughter, AS Hareesh Kumar and Pradeep PillaiAs a former boss celebrates his father’s birthday, some reflections

By Shevlin Sebastian

Vinod Mathew was the Resident Editor of the New Indian Express, Kerala, for a little more than eight years, until March 31, 2019. I was part of his team as a feature writer. Now and then, during our conversations, he would talk about his father, AM Chacko. He was a retired Additional Labour Commissioner. But he now worked as a farmer, was very active in the church, and played badminton daily.

Three years ago, Chacko Sir had a stroke. It occurred at 6 a.m., while he was waiting to be picked up by another player. This happened to be the local parish priest Fr P K Chacko.

The priest noticed that Chacko Sir’s voice had slurred. He immediately informed Vinod in Kochi. Thereafter, he made Chacko Sir change from his badminton gear into a shirt and trousers. Fr. Chacko drove him to the Pushpagiri Medical Hospital, seven kilometres away. Because of Chacko Sir’s high level of fitness and the swift treatment, he made a full recovery. Today, he continues to play badminton and arrives at the court every day at 6.30 a.m., the first in the over-sixty category to do so.

I had never met Chacko Sir. But when Vinod and his family were going to celebrate their father’s 90th birthday, he invited a few of his former colleagues. Along with former News Editor Anoop Thomas and his wife Elsy Paul, we journeyed to Tiruvalla.

At the function, Vinod said the reason the family decided to celebrate it was because his father had told him, “There is no point talking good things about me after I die. Then I cannot hear it. So, better do it when I am alive.”

This statement struck me. In Kerala or India praise is rare. But we are quick and relentless with our criticisms. Unlike the West, we don’t honour and celebrate the achievers in our midst, unless they are celebrities.

I was keen to meet Chacko Sir, because, like him, I have been exercising daily for over thirty years. In the earlier years, it would be a run, but now it is six days of swimming while the seventh is devoted to running.

There is a difference in the body language of those who exercise daily and those who don’t. Those who do have a lightness about them as they walk about. Those who don’t, tend to move ponderously, as they grow older, and put on weight and lose their sharpness (sorry guys, couldn't avoid taking this potshot!).

It was a wonderful event. Many people showered praise on Chacko Sir. They included bishops, priests, parishioners, friends, relatives and former colleagues. Chacko Sir has led an exemplary life, always smiling, and helping people in whatever way he could. And when I shook Chacko Sir’s hand, his grip was firm. He exuded an aura of positivity.

Much later, my former colleague Chandrakanth Viswanath, who now works for News18.com, told me a telling anecdote.

After lunch, when Chandrakanth was washing his hands, Chacko Sir was standing there. And when some of his badminton club colleagues cheered him, he raised both his arms skywards. “That shows how spirited he is,” said Chandrakanth.

But this is not to forget Chacko Sir’s wife, Aleyamma, who turns 90 on December 29, and has been the rock of the family. They have been married for 61 years. Aleyamma retired as Regional Assistant Director, Social Welfare Department, after a 30-year career. The couple have four children – Vinod, Vineetha, Veena and Vidya.

It was good to meet former colleagues. Anoop stole the show with his flamboyantly colourful shirt, his goatee, his flowing hair, and a black beret. Many people thought he was a film personality. On the opposite pole was the always low-key Anil S. He had come all the way from Thiruvananthapuram, 118 kms away.

As usual, we exchanged news about other colleagues and the state of the print media.

Chandrakanth spoke about the joys and troubles his wife Geethu experienced as she set up a publishing company. This turned out to be an eye-opener.

It was good to connect with people. In book-writing mode these days, I rarely meet anybody. It is solitary and silent. I spend a lot of time staring at walls.

After the formal function, we went to Chacko Sir’s 55-year-old home. It had received a fresh coat of paint and looked as new as ever. Vinod spoke about the history of the family by pointing at photographs on the walls. I also saw the current extended family.

Vinod’s daughter-in-law, Vanshikha Narain Saigal, is from Lucknow. When I asked her whether she knew Malayalam, she sweetly said, “Korichu Korichu (a little).”

She spoke about another reality: of travelling on expressways from Noida to Lucknow, with her husband, Aaron, touching speeds of 160 kms per hour in their car. Vanshikha also reminisced about her pet dog, a Lhasa Apso with the name of Bailey, which is now being looked after by her brother since she is out of town.

Listening intently was Pradeep Pillai, of News18 Kerala, who had a ready smile on his face. His handshake was as firm as Chacko Sir’s. And his joie de vivre was visible on his face. It helped that it was a rainy day and the climate was very pleasant.

Following tea, and many goodbyes, on our return, Anoop and I engaged in a host of topics. Since we ignored Google Maps, it was inevitable we would go down the wrong road, turn around, go left and right, so that we could talk uninterruptedly. But inevitably, we reached a road where Anoop knew the way back. So, we reached Kochi at 8 p.m. And I hopped on a Metro train to go home.

It was a day when an elderly eminence gave a subtle but powerful message on how to age gracefully.

Thank you, Chacko Sir!

June 10, 2022

A Day in the Life

This short story is set in the Mumbai underworld

By Shevlin Sebastian

A man was sitting behind the steering wheel of a Kia Seltos car. The car had stopped at a traffic signal at Byculla in Mumbai. On the seat next to him, there was a gleaming revolver placed under a Marathi newspaper. On the floor, beneath the dashboard, there was a brown leather bag.

The man had a thick double chin. Two bulbous eyes jutted out. Rohit Gaikwad was wearing a white safari suit. His socks were white, and so were his shoes. He had a gold bracelet on his left hand. He also wore a Rolex watch.

When the signal changed, Rohit pressed the accelerator. He was on his way to Andheri, 21 kms away, to collect money from a builder by the name of Sunil Jhangpuria.

Sunil spent all his time on work sites. Right next to the building was his small makeshift office. It was almost like a tin shed. But Sunil had installed an air conditioner. So, it was cool even though it was the hot and sweaty month of May.

When Rohit entered the office, Sunil was all smiles and ordered two cups of tea. The peon walked out to get it.

They talked about the government, the state of the economy, Bollywood celebrities, the price of vegetables, and the real estate business. The tea arrived; they sipped the liquid in silence. After the peon took the cups away, Rohit looked at Sunil and said, “Is the stuff ready?”

Rohit nodded. He swivelled in his chair, stood up, and walked to a safe in the wall and opened it by using numbers for the combination lock. He took out several thick bundles.

By this time, Rohit had opened his brown leather bag. Sunil placed the bundles inside.

“How many petis?” said Rohit.

“One hundred,” said Sunil, as he placed the bundles inside the bag. Each peti contained Rs 1 lakh. That meant Rs 1 crore.

“What about the rest?” said Rohit.

Rs 3 crore was the amount to be given.

“Two days later,” said Sunil.

Since Sunil always kept his word, Rohit did not protest. Rohit knew Sunil did not want any problems from the underworld. He knew it was better to be safe than sorry. After he paid the money, the work would go ahead with no disturbances from the workers or the office staff. The goods will arrive at the site on time. Nobody will be there to block the road. The police will also stay away.

After Sunil had transferred the money, Rohit zipped the bag with a snapping sound.

He told Sunil, “Call us if you face any problems. We are here to protect you.”

Sunil was tempted to give a sarcastic remark that it is they who are the problem, but he bit his tongue.

Instead, Sunil nodded.

Rohit strode towards the car. He could hear a cement mixer in the distance. Sunil also heard workers shouting at each other across floors. It was a 20-story building.

Work was going on at full tilt. This was Sunil’s 15th project. He made a decent profit. He knew it would have been much more if he hadn’t had to pay the underworld. In different areas, different groups dominated. He paid the gang that ruled that area. They respected him because he kept his word and did not bargain too much.

Rohit turned the ignition key and pressed on the accelerator. For the past 25 years, he had been an enforcer of the Don of Mahim Chawl Prashant Bhosle.

They had grown up in the same slum in Byculla and had been buddies for years.

Prashant drifted into crime by being a pickpocket and drug courier. Rohit followed in his footsteps. Rohit built up a reputation of being honest and loyal to Prashant. And although he carried his revolver everywhere, he rarely used it. He didn’t have to. The sight of it was enough. Rohit dealt with corporates and professionals because he could speak English. He dressed well. Rohit was a presentable face of the underworld. He spoke politely most of the time.

But Prashant had told him not to dress so showily. The Rolex watch and the gold bracelet. “It is always better to be low key,” said Prashant. “People get jealous. They want to bring you down.”

But since Prashant spoke in a soft voice, Rohit knew the don did not mind his sartorial style. Rohit ensured the money came in steadily.

Prashant paid Rohit generously. So, the latter was happy.

He had an arranged marriage with a Marathi girl, Deepa. She had studied up to Class 12. He had no problems with her. Deepa never said no when he wanted to have sex. She would only demur when she had her periods. They had two children, a girl named Suchitra and a boy, Sriram.

Their children were studying in good English schools. Rohit could afford to buy them laptops and other accessories.

Thanks to the clout of the Bhosle gang, he slept with whores whenever he was in the mood. He was not sure if his wife suspected. Anyway, there was little she could do about it.

The car came to a stop at a traffic stop. Rohit was thinking about his plans for the day. He would give the money to Prashant and get it counted. Thereafter, he would venture out to Worli. He wanted to meet a builder there and put some pressure. Prashant felt the builder was evading him and not paying the money that was asked of him. He was wondering whether he should stop at his mistress’s house in Bandra and have a session. Sex every day was a must for him.

From the corner of his eye, Rohit saw a movement near the car. When he turned to look through the window, three shots rang out, one after the other. One caught him smack in the middle of his forehead, between his eyes. They aimed the other at his heart. The third hits his neck. Blood spurted out, staining his white shirt. His mouth opened in a soundless scream. He extended his left arm sideways to get the revolver, which was beneath the newspaper. Soon, his head fell onto the steering wheel; the horn blew non-stop. Rohit lay still and lifeless.

Outside, there were shouts and screams. Women put their fingers in their ears. Many men started running. Vehicles stopped as drivers froze in fear. The assassins, two of them, on a motorbike, did not flee immediately. Both were wearing black cloth masks, which covered their heads, with slits for the eyes. One of them opened the door on the other side and grabbed the bag, which contained the money. All this happened within seconds. Within a minute, there was a stillness in the air.

The police constable, who was supervising the traffic, arrived and peeped in. With one look, he knew Rohit was dead. With his wireless, he requested an ambulance from headquarters. Within 15 minutes, the vehicle arrived. They pulled Rohit out of the car. The car horn stopped. The sound grated on the nerves of pedestrians, street residents, drivers and the local shop owners. Traffic began to move. The ambulance sped away at high speed with a blaring siren.

A cop in Prashant’s pay informed him of the hit. As a result, he came to two conclusions. Either Sunil planned this or somebody from his inner circle had passed on the information. But the pertinent question was: to whom was the info given? And why? Was it for information only in exchange for cash? Or was there a vendetta behind this? He twirled the edges of his moustache with his finger, as he wondered who among his inner circle could betray him.

He called his closest associate, Manish, a childhood friend. “Speak to Sunil. Ask him what happened. The money is lost. Does he have any leads? Find out whether he had organised the hit? Get the information from him in any way you want.”

Manish understood he could use violence if necessary.

So, Manish went to meet Sunil. But the business owner was not in his office. The office staff did not know where he was. Manish called Prashant, who called a police contact in the cyber cell and gave the number. Within half an hour, the officer called and said the number was not active. Prashant realised it could be Sunil, though it was most unlikely he was behind the hit.

Which meant there was somebody else behind Sunil. Could it be the leader of another gang? But right now, the waters looked muddy. There was no clarity about the situation. In one fell swoop, he had lost Rs 3 crore. Rohit had not informed Prashant of the lowered amount.

Prashant told Manish to go to the hospital and confirm Rohit had died. After that, he should inform Rohit’s wife.

“Okay,” said Manish.

Prashant could hear rumbling sounds in his stomach. This was always the warning signal from his body. That something was not right.

He called a meeting of his top team members. They sat around the dining table.

The servant served cups of tea along with chips.

“Okay guys, I need to find answers,” he said. “Who ordered this hit? And why? Who took the money? How did they know Rohit was planning to collect the money? Where is Sunil? Why has he fled?

The members kept quiet. They were not sure what had happened. Everything happened so quickly. As they were thinking of the various possibilities, they took hesitant sips from their cups.

There was a commotion at the gate. Lots of yelling. When Danish, a sharpshooter, looked from the window, he turned and said, “It’s a police raid.”

But it was too late. There was nowhere to go. The police came up the stairs, armed with warrants, and arrested all the members, including Prashant. They were all taken to the Arthur Road prison in a police van.

At the hospital reception, a woman employee told Manish, “Rohit Gaikwad, dead on arrival. He is in the mortuary.”

So, Manish made his way to the first-floor house in Byculla, where Rohit lived with his wife and children. The children were in school. He knocked on the door.

Deepa opened it. She was wearing a plain white cotton saree. Manish was surprised at how slim she was, despite being the mother of two children. He wondered how she would be in bed. He felt he had a chance now that Rohit had died.

She looked at him and immediately said, “Has something happened to Rohit?”

He nodded.

She led him inside.

It was a middle-class drawing room. A sofa was placed against one wall. Two armchairs on the other side. A small glass table in the middle. The Lokmat newspaper was on it. Against another wall, there was an aquarium. It had small lights. Red and black fish swirled about in an endless loop in transparent water.

“What is it?” she said, leaning forward and looking at Manish.

Manish came straight to the point.

“Two men shot Rohit dead at a traffic stop,” he said.

Deepa fell back on the sofa as she cupped her open mouth with her fingers.

“What happened?” she said.

“We don’t know who they are,” said Manish. “We are investigating. We will find out and take revenge. Prashant said he would come and meet you next week. You don’t have to worry about the financial aspect. We will look after everything. The body is in the mortuary. Enlist the help of your family members to conduct the cremation. If you need any help, please call me.”

Tears rolled down her face.

Deepa knew that to face life without her husband beside her would be tough, especially when they had two school-going children.

She cried for a while. She stood up and dabbed her eyes with the end of her saree. Deepa stared out of the window.

Manish also stood up and gave his number. Deepa entered it into her mobile.

As soon as Manish left, Deepa’s tears dried up. She smashed a fist into a palm. ‘Thank God, the oaf is dead,’ she thought. ‘I am free now. Instead of being a slave, I can pursue my dreams. He slept with so many women. Never took a bath before having sex with me. Every day he smelled different. I was always worried about contracting a sexually transmitted disease. Yes, my children will be devastated, but they will get over it. Now I will enrol in college, get a degree and get a job.”

She realised how afraid she had been of Rohit. He always carried a hint of violence about him. Rohit couldn’t let go of the fear of being attacked. He always had a wariness about him, even when he was in the house.

Deepa realised that, for Rohit, she resembled only a hole. All he desired was to enter her. She was too afraid to protest or say she was not in the mood.

Deepa entered the bedroom and opened the steel almirah. The most important thing at the moment was whether Rohit had any money in the bank. She knew Prashant would help them on the financial front.

She looked for the bank passbooks in the safe. She came across two: State Bank of India and Bank of Maharashtra. Both accounts had deposits of Rs 10 lakh each. She searched for Fixed Deposits and shares. She remembered Rohit had kept a file on the top shelf. This was where he usually kept his revolver.

She brought down the files. He stored them inside a red cloth covering. As she unwrapped the cloth, she quickly glanced at her mobile to check the time. The children would arrive in half an hour.

She checked the files. Yes, there was an FD file. There were seven certificates in all. The total was about Rs 5 lakhs. So, fine, things would not be so difficult for the first couple of years at least. The flat and the car belonged to Rohit. She would sell the car. They could travel by Uber, auto or train.

Deepa put the files back, shut the almirah and informed her sister and mother about the death. Her father had passed away a few years ago. They promised to arrive within half an hour. They would then go to the hospital.

After Manish stepped out of Rohit’s house, he got a call. It was a member of the rival gang asking whether the police had arrested Prashant. This was the first time he heard about it. He said he would call back and called Prashant’s landline number. Ashok, the servant, answered and confirmed the arrest of the entire gang.

Manish stepped into a roadside hotel and ordered a tea. Manish had two options. He could try to meet Prashant at Arthur Road prison or go underground. He reflected for a few minutes as he sipped his tea.

He shook his head, paid the bill, and walked out.

Manish switched off his mobile and threw the SIM card away. He headed to a house in Andheri and let himself in with a key. The two killers were sitting on the edge of the bed, watching TV.

“Okay,” said Manish. “Show me the bag.”

When he opened and counted the money, he realised with a shock that it was only Rs 1 crore. ‘Shit,’ he thought. ‘It was supposed to be Rs 3 crore.’

“Is this the money or have you guys hidden away something?” he said, pointing a revolver with a silencer at them.

The boys fell at his feet.

One of them said, “Sir, we did not even open the bag. Please believe us.”

From the tone, and from his years of experience, he knew they were telling the truth. For some unfathomable reason, Sunil had given less than he had promised.

“Okay,” he said, “Get up.”

He gave them Rs 20 lakh each and told them, “Go to Uttar Pradesh or Nepal. If you don’t want to get caught, stay underground for one or two years. You have a reasonable chance to escape, since the cops have not seen your faces. Change your clothes and head out.”

They nodded, changed, put the cash in suitcases and left.

Yes, Prashant was right about his suspicions. It was Manish who had squealed to the police. Using a wiretap, he recorded talks with Prashant and the other gangsters. He photocopied the account books and sent them by WhatsApp to an investigative officer. They had enough evidence to send Prashant to jail for several years.

He did it because he was tired of the life of crime. There was not a moment’s rest. Manish feared divine retribution after his death. Since he had not married, he had nothing to fear. The gang had damaged the lives of so many people. They had killed too many people in intra-gang warfare. He always felt fearful whenever he walked the streets. Anybody could make a fatal attack on him. He knew Prashant would not allow him to leave. So, he decided to sink everybody by becoming a mole for the police and make good his escape.

At 8.30 p.m. Manish got into an unreserved compartment of the Kolkata-bound Jnaneshwari Express. He had a suitcase which contained Rs 60 lakh, his revolver, and some clothes. In Kolkata, he had arranged for plastic surgery to be done on his nose. He wanted his snub nose to be straightened. The cleft in his chin would be closed. He would shave off his hair and wear a wig.

After that, he would make a fake Aadhar card, ration card and passport. In Kolkata, he would open several accounts and deposit the money over one-and-a-half months, so that it aroused no suspicion.

Thereafter, he planned to join the Sevashram Ashram in Bolpur, 160 kms from Kolkata. He would become a monk, clean himself of all his sins, and stay hidden for at least a decade.

After that, he would decide on the next course of his life.

(Published in Active Muse, Pune)

June 3, 2022

A brief halt

(Flash Fiction)

By Shevlin Sebastian

On a cloudy morning, an Army Shaktiman truck was parked beside a tea stall on the outskirts of Baramulla in Kashmir. Several soldiers remained sitting in the back of the truck holding the rifles, with their butts resting on the floor. They wore olive green Army fatigues. One soldier stepped down and headed to the tea stall. He brought back several plastic cups of steaming tea and passed the tray to the soldier sitting near the entrance. That man passed the teacups to the others and returned the empty tray to the soldier standing on the ground.

His name is Varghese Chandy. The Kottayam-based Varghese had joined the Army three years ago. The 23-year-old belonged to a lower-middle-class family. His father had been a struggling farmer. They had a tough time right through his childhood, making ends meet. So, Varghese opted for the Army.

He knew he would get a steady income and when he retired, he would be assured of a lifelong pension. But Varghese knew there were dangers in defending the country. He could be killed at any moment.

But he had accepted this possibility from the very beginning.

In Baramulla a week earlier, there had been a gunfight between militants and soldiers. A 12-year-old boy had died in the crossfire in the Azad Gunj area. This outraged the local people. A vast crowd had gathered on the main road shouting anti-India slogans.

Despite many provocative slogans, the soldiers remained calm. The burial passed off peacefully. The mourners returned home dejected.

Varghese knew the Kashmir people had suffered too much collateral damage in the unrest that had gripped the state since Independence.

The Army head had asked a fresh group of soldiers to Baramulla to relieve the pressure on the existing troops. Varghese had been drafted in.

He knew a stint in Baramulla would be risky, but he could not disobey the orders of his superiors.

Sometimes, he looked back on his peaceful life back in Kerala. There was hardly any presence of the police or the Army in the streets. There were no roadblocks. Nobody stopped and asked you for your ID card. The weather was manageable, although it was becoming clear that the monsoons had become unpredictable. There were large flash floods. As a result, several houses had been washed away, especially those who lived in hilly areas like Idukki. In some places, the entire slope had collapsed, owing to the random quarrying for stone. But what could he do stationed in Baramulla? Nothing.

The soldiers finished their cups of tea. Varghese picked up a large plastic bag from the shop and took it to the truck. They placed the used plastic cups inside the bag and returned it to Varghese.

The senior officer boarded the truck at the front, near the driver. Varghese paid the stall owner and jumped in at the back. He realised he needed to call home soon. He had not spoken to his parents or his younger sister for a week.

The driver turned the ignition key.

The next thing the locals heard was a tremendous blast. Somebody had placed a bomb on the ground underneath the truck. 24 soldiers and the officer died at once. Varghese’s body was charred beyond recognition. The uniform stuck to his body like a second skin. His skull was fractured. Blood flowed from several head wounds. He passed away within minutes.

The people rushed up and pulled the smouldering bodies away from the carnage in a bid to save lives. It was of no use. The tea shop owner also died. This was a regular stop for all the Army trucks. Someone knew this and planted a bomb beforehand in the mud where the lorry would be parked.

Now what?

The Army informed his parents. His mother wept bitterly. His father stared blankly at the wall. Both wondered why this happened. Varghese had been sending money home. At the prime of his life, God and the militants had taken their son away.

The political leaders said, “The nation will never forget the brave sacrifices of our soldiers.”

But the sad news is that the nation would forget. Like they did the many riots, insurgencies and wars that took place in the country during the past several decades.

The world will move on.

Following a mourning period of several months, his parents would pick up the broken pieces of their psyche and try to stitch them together.

This is the resilience God gives human beings.

But they would remember Varghese at every moment of their waking lives till they passed away.

As for the militants who planted the bombs, there would be many high-fives, collective smiles, hugs, kisses, and congratulatory thumps on the back, followed by a celebratory dinner.

“Take that, India,” one of them shouted and showed an upraised finger at his comrades.

They laughed.

Celebration and sadness at the sight of dead bodies.

Some laugh at the tragedy of others.

What is the meaning of life?

The Buddhist said, “Life is yin-yang: sunlight and darkness; male and female; beautiful and ugly; sweet and sour; love and hate.”

(Published in Twistandtwain.com)

May 7, 2022

My Mother and I

Photo: My mother, Ritty Sebastian (extreme right) with family friends (from left) Ramany Paul, Mercy Antony, and the late Jose Kadavil

By Shevlin Sebastian

At 9.30 p.m., on a Saturday, I told my mother, “The mass tomorrow is at 7 a.m. We will leave at 6.45 a.m. Don’t awaken me at 5.30 a.m.”

My mother nodded.

The next morning, at 5.30 a.m. my mother opened my bedroom door. I was lying on my back, in a T-shirt and Bermuda shorts, my eyes closed. I was sleeping alone as my wife had gone to her mother’s place.

My mother stood at the door for a couple of seconds.

Then she came up, peered at me and said, “Shev….lin.”

Her voice cracked at the lin.

It was a chilly morning in Kochi. It had rained furiously the previous night. Maybe my mother felt the cold. Her tone reflected this.

“It is 5.30 a.m., don’t we have to go to Mass?” she said.

“Mum, the mass is at 7 a.m. We have to leave at 6.45 a.m. There is more than an hour left,” I said, still keeping my eyes closed.

The 85-year-old mother stared at her middle-aged son, and said, “Okay.”

She turned and walked back to her room.

But she forgot to close the door.

Now the light streamed in from the dining room. I could see sunshine behind my closed lids. Lazy to get up and close the door, I turned on my stomach and drifted off to sleep.

When I am middle-aged, I speak to my mother with my eyes closed. But when I was in kindergarten, I would be bright-eyed when I returned from school. My mother was there to take me in her arms. Through the nine months of the pregnancy, she nurtured me in her womb. She ate well and walked carefully so that she could deliver me safely. She was always there through the vital years of my childhood.

Now I am impatient with her.

In the early morning, I sit at the dining table, reading the newspaper with a cup of tea.

My mother sits in the living room and reads the paper, too.

It is a time of the morning when I like to be silent.

But my mother will call and say, “There is a sale coming up. The discount is 50 percent.”

Depending on my mood, I will say, “Ah, okay.”

At other times, I have said, “Give me two minutes. I will rush to the shop and buy the stuff.”

My mother would give a short laugh, knowing I am being sarcastic.

Sometimes, she will say, “Did you see the photo in the newspaper?”

“Yes,” I would lie.

I just don’t want to have a conversation this early.

My mother moved in with me when my father passed away last year. I discovered a trait I never knew she had: a stubbornness.

If she did not want to eat something, nothing or nobody could force her to change her mind. That was the case when she felt she did not want to have a bath on a particular day.

So, we are learning to adjust.

But this much I know about my mother.

She has hurt no one in her entire life. To a large extent, I am like her. She also gave me certain habits.

She told me many stories during my childhood and teenage years. I would listen enthralled. There is no doubt I became a storyteller because of her.

When I was a baby, my mother would place me against her body, on an armchair, and read the newspaper. So I began looking at print from the beginning of my life. I continue to look at print with joy, peace and happiness. Every day, I read for hours, on paper, on my mobile, or laptop.

My mother loves to read newspapers. She told me when she was a child, she would go for morning mass. After mass, she would race her brother home to see who could get the newspaper first.

My mother is in the autumn of her life. Like my father, she has been blessed with good health: no high blood pressure, no cholesterol, no sugar, no diabetes. I touch wood as I write this.

Her siblings are ageing like her.

Four of them have passed away. Two were younger than her.

How do I sum up my mother?

Once I met an elderly man at a family function. His parents were family friends of my mother’s parents in their hometown of Muvattupuzha.

He said, “In our youth, we called your mother, ‘Pretty Ritty’.”

That’s a nice epithet for my mother: pretty in so many ways.

(Published in Twist and Twain)

https://www.twistandtwain.com/memoir/my-mother-and-i/

#Motherofmine #Mothersonrelationship

April 4, 2022

On the highway

By Shevlin Sebastian

EDITOR’S PICK OF THE WEEK – KITAAB.ORG (April 3, 2022)

Sawant Singh pressed the accelerator. There was a roar from the exhaust as the truck gained speed. He was on the Bhopal-Mumbai National Highway No. 3. Sawant was carrying a truckload of oranges for traders in Mumbai.

As he stared at the road, he could feel the sun beating down on the truck. The cloth of the turban over his forehead was wet. He could feel the sweat gathering in his armpits. Next to him was his assistant, Rupesh. A Dalit, he lived in the same village of Tarn Taran Sahib as Sawant.

Sawant looked at his watch. It was nearing 1 p.m. It was time to stop for lunch. After a kilometre, he turned left onto a narrow road and travelled for half a kilometre. Soon, he saw ‘Bhupinder’s Dhaba’. There was a large parking area in front. Sawant could see several trucks, a few cars, and two-wheelers. He shut the engine, stepped down, and walked towards the restaurant. Rupesh followed, a dark-skinned, thin man in brown trousers and slippers.

Once inside, Sawant headed to the large washing area. He stood in front of a tap and splashed water on his face a few times. Sawant rubbed water on his neck and washed his forearms, too. He used soap to wash his fingers. Thereafter, he wiped his face and hands with a towel, which he placed around his shoulders.

There were a lot of truckers, with their broad shoulders and thick hands, having lunch. Sawant selected a table where nobody was present. He ordered a plate of tadka dal, roti, and a small bowl of onion with chilies and salt. Rupesh sat at the same table but two chairs away.

Sawant kept one ear cocked as he heard people talk about the terrible roads they had driven on. Others complained about the high price of fuel, the hot weather, and the sluggish economy. People were always complaining, he thought. He did not enjoy that. He had an attitude of ‘live and let live’. And he preferred to keep quiet.

Sawant did not like to pontificate. And that desire became even less as he pondered over his personal life.

Sawant is the son of a farmer who grew wheat. He was the third son. The first two sons helped in their father’s fields. But Sawant wanted to do something different. He wanted to travel a bit, but since he had studied only up to Class 10. So, he became a truck driver.

He had married a girl called Uma. She was 13 years his junior. She belonged to a poor family. Sawant agreed to marry her because Uma was beautiful. She was fair-skinned, with an aquiline nose, doe-shaped eyes, and red lips. And she had lovely, thick breasts. It filled his entire palm. Uma was reluctant to marry a man who was so much older than her. But her father told her that Sawant belonged to a traditional farming family. And he had a steady income. He would look after her well.

And indeed, he had. They had two children, both sons, one studying in Class 7 and the other in Class 5.

There was one problem in this idyllic situation. Uma was suffering from venereal disease. Sawant was the culprit. On long truck rides, he would stop at places where prostitutes serviced the truckers. Unlike his fellow drivers, Sawant did not like to use condoms. As a result, he got infected. But he did not know about it. By this time, he had returned home and impregnated his wife.

Sawant got himself treated in Chandigarh. But he was afraid to take Uma to a big city, lest the secret came out that he was having sex with random women. So, he had taken Uma to a physician in Tarn Taran Sahib, who prescribed paracetamol. But Uma showed no improvement. She had painful urination and vaginal discharge during periods. She felt weaker day by day. Uma could no longer look after the children. Sawant’s mother stayed with them and ran the household.

Sawant would take a week to return. He knew he would have to rush Uma to Chandigarh, 229 kms away, and get her treated at an excellent hospital. Otherwise, he feared she might die.

Sawant started the truck, and they set out once again.

Yes, Sawant knew, he had a weakness for sex. He liked to have it every day. But Uma was not that interested. Sawant did not force himself on her. He preferred when she was in the mood. So, his urge remained, and he took it out on the prostitutes he met on the road.

He had managed to keep another secret, too.

Sawant had another family in Mumbai. This Marathi woman, Renuka, worked as a prostitute. Sawant had become her customer at Kamathipura, the red-light area. Over 5000 prostitutes lived and plied their trade in that area.

He liked her high spirits and abandon in making love. She gave her all during the act. She was chocolate-coloured, with hair going down all the way to her waist. One night, he had asked why she was so passionate when it was a commercial transaction.

Lying on top of him, she stared into his eyes and said, “I like sex.”

Soon, he began frequenting her whenever he was in Mumbai.

After two years, she begged him to free her from the clutches of the pimps and the brothel keeper. Sawant said he was helpless. He explained he could not take her anywhere since he was a married man and had two children. She said it did not matter. All she wanted was to get out and start a new life.

So, one day, he went for a session late at night. They slipped out without anybody knowing. They took a room in a hotel in Andheri.

As they sat next to each other on the bed, Sawant said, “Now what?”

Renuka placed her face in her palms and stared at the floor.

She had nothing to say.

“Where is your hometown?” said Sawant.

“Ratnagiri,” she said.

“How far is it from Mumbai?” asked Sawant. He had not gone to Ratnagiri before.

“Nine hours by bus,” she said.

“Would you like to go home?” he said.

She shook her head.

“My parents allowed me to go away with a stranger,” she said. “They never found out whether or not I was okay.”

Sawant pondered over what to do. But he could not find any solutions.

It was Renuka who provided it.

“There are social groups who care for prostitutes,” she said. “But I don’t know their numbers.”

Sawant had a friend in Mumbai, Balbir Singh. He had been his schoolmate. A good student, Balbir had got a management degree. Now he worked for a multinational company.

The next morning, Sawant called him and asked him about the social groups.

Balbir immediately looked it up on Google it and provided him with names and phone numbers.

Sawant called one number. The woman was forthcoming and helpful. The office was in Lokhandwala West, which was not very far away.

Sawant took Renuka to the office.

There were posters on the wall. In one, a woman was being led out of what looked like a prison cell by another woman. The caption said, ‘We are here to save women. To give them a better life.’

The woman behind the desk wore spectacles and had pulled back her hair into a ponytail. She was in her late thirties. Renuka told her of her escape and how she was afraid the pimps would abduct her and take her back.

By her reaction, Sawant knew she had heard the story many times before.

The woman nodded and said, “Nothing to worry. We have safe houses where you can disappear for a while. They will lose interest after a couple of months.”

So Sawant left Renuka with the lady and returned to Punjab in his truck.

Later, Renuka told Sawant she had begun work in the NGO which had rescued her. Her job was to advise the other girls who had escaped like her. She also mopped the floors, cleaned desks and windows, and filed documents.

Sawant met her whenever he was in Mumbai. He hired a hotel room for their encounters. Things went on.

One day when Sawant met Renuka, she told him she was pregnant.

Sawant asked her to abort the child. Renuka stood her ground and said no.

“You have the experience of being a father,” she said. “Let me have the experience of being a mother.”

“But the child will have no father,” he said. “The boy should have the father and mother with him at all times.”

Renuka saw the funny side. “What makes you think it is a boy?” she asked with a smile.

Sawant smiled, and said, “It’s an intuition. Who knows? Listen, my advice to you is to abort.”

In his mind, he thought, ‘Messing with a woman leads to complications. It is not only sex. They want more.’

“Sawant, it is easy to say that, but I can feel the kicks. This baby is alive. I can’t kill it,” she said, reaching forward and taking his calloused palm to place it on his stomach.

After a few seconds, Sawant could detect a kick. He remained silent. He would have preferred an abortion, so that he did not have the extra responsibility of a child.

Renuka said, “In front of society, you could pretend to be the husband.”

Sawant remained silent for several minutes. Renuka also kept quiet. She did not want to provoke him.

Sawant pressed his lips together and said, “Okay, but I will not have my name on the birth certificate. Get somebody else. There can be no proof anywhere.”